Abstract

Background/Objectives

Systemic chemotherapy is recommended for all stages of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), with a recent shift towards neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for resectable PDAC. The objective of this study was to compare outcomes of NAC versus AC for early stage resectable PDAC in the NCDB. Methods: Patients aged 18 or older with stage I or II PDAC in the National Cancer Database (NCDB) from 2010 to 2017 were identified. Logistic regression evaluated oncologic outcomes. Kaplan-Meier method followed by Cox proportional-hazards regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using propensity score matching was used to compare overall survival (OS).

Results

NAC led to a 13% risk reduction of a positive resection margin (OR:0.87; 95%CI 0.78–0.97), and a 59% decreased risk of positive lymph nodes (OR:0.41; 95%CI 0.38–0.45). The median OS for all patients treated with NAC was 2.56 years versus 1.95 years for surgery +/- AC (p< 0.001). NAC had an OS benefit for all patients (HR:0.80; 95%CI 0.78–0.83), as well as for Stage I (HR:0.89; 95%CI 0.84–0.94) and Stage II patients (HR:0.71; 95%CI 0.68–0.75).

Conclusions

NAC appears to be associated with a survival benefit for patients with resectable PDAC. NAC also decreased the risk of a positive resection margin and positive lymph nodes at the time of surgery.

Keywords: Pancreas, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, Resectable, Neoadjuvant

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the 4th leading cause of cancer death in the United States [1]. Approximately 1.7% of men and women will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at some point during their lifetime [2]. SEER estimates that there will be 60,430 new cases diagnosed and 48,220 attributable deaths in the year 2021.

Although surgical resection followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) remains the cornerstone for treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), only 25% of patients present with resectable disease at the time of diagnosis [3,4]. In recent years, neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) has been used in the setting of both borderline resectable and locally advanced disease to successfully convert patients into operative candidates, increase R0 resection rates, and prolong median progression free survival (PFS) and median overall survival (OS) [5,6]. There has also been a shift towards use of NAC for resectable PDAC. Proponents of this approach argue that up to 50% of patients are unable to receive the recommend adjuvant therapy postoperatively secondary to surgical related complications. Moreover, because most patients with recurrent PDAC after surgical resection fail in the form of distant metastatic disease, the ability to assess the biologic response of the tumor in an in vivo setting may also select for patients who progress on systemic therapy and would likely not benefit from high-risk surgical interventions [7,8].

An earlier National Cancer Database (NCDB) study with data from the previous decade showed the use of NAC in resectable tumors as compared to upfront surgery with AC resulted in a significantly improved OS [9]. Our study re-examines the use and outcomes associated with the administration of modern NAC for patients with resectable PDAC.

Materials and methods

Cohort selection

The NCDB is the largest cancer registry in the United States and is maintained by the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. It captures 70% of cancers in the United States. Reporting facilities are required to have at least 90% patient follow-up over 5 years [10]. This study was deemed exempt by the guidelines set forth by the institutional review board. All data was de-identified and the NCDB was not asked to verify the results or the statistical validity of this study.

The NCDB was queried for patients aged 18 years or older with clinical stage I or II PDAC based on histology codes 8140, 8141,8143, 8144, 8145, 8147, 8161, 8163, 8210, 8211, 8245, 8255, 8260, 8261, 8262, 8263, 8255, 8430, 8440, 8480, 8441, 8453, 8460, 8470, 8471, 8480, 8481, 8500, 8521, 8570, 8571, 8572, 8573, 8574, 8575, or 8576. Clinical stage I or II has been used before as a surrogate for stratifying patients as having resectable disease.8 Patients were excluded if they did not have data on the selected procedure of the primary site (Whipple, local excision, partial/distal pancreatectomy, or NOS), adjuvant therapy, or follow-up. Patients were grouped based on the intended timing of administration of chemotherapy, NAC (Chemotherapy+Surgery+/-AC) or upfront surgery (Surgery+/-AC) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Data Flow Chart.

Statistical analysis

For the comparison of patients with NAC versus upfront surgery, Chi-Squared tests and ANOVA analysis were performed for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to examine factors that contributed to patients receiving NAC, as well as the predictors associated with positive margin and number of positive lymph nodes. We also explored the trend of NAC use over time.

OS was calculated from diagnosis to the time of death or last known follow-up and compared using the Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank test. To examine for independent effects of NAC on OS, multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression were performed, adjusted for age, gender, race, insurance, facility type, residence area (rural/urban), comorbidity score, clinical stage, primary site, surgery type, tumor extension, lymph nodes examined, margin, CA19–9, grade, and time to surgery. We also compared OS between patients who had NAC and those who had both surgery and chemotherapy after their surgery, adjusted for the same set of covariates. To assess the sensitivity of the results and to account for immortal time bias, we further conducted a 6-month conditional landmark analysis where only patients who survived at least 6 months after diagnosis were included as a conditional landmark in multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression as well as Cox proportional-hazards regression with inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using propensity score method. The stabilized inverse probability weights were derived from the GBM-ATT predicted probabilities of NAC, on the same set of covariates. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was set at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.6.3.

Results

Patient characteristics

Of 19,415 patients with early stage PDAC who had surgery, patients who received NAC were more likely to be younger, treated at an academic center, and present with clinical stage II and/or T3 disease in the pancreatic head or neck, with vascular or other local invasion, and higher initial CA 19–9 levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Upfront Surgery (n = 15,273) | NAC (n = 4142) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 2010 | 1982 (13.0) | 281 (6.8) | |

| 2011 | 2021 (13.2) | 342 (8.3) | |

| 2012 | 2144 (14.0) | 453 (10.9) | |

| 2013 | 2283 (14.9) | 515 (12.4) | |

| 2014 | 2413 (15.8) | 704 (17.0) | |

| 2015 | 2418 (15.8) | 861 (20.8) | |

| 2016 | 2012 (13.2) | 986 (23.8) | |

| Age, years (mean (SD)) | 67.26 (10.24) | 64.13 (9.66) | <0.001 |

| Age, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 18–55 | 2041 (13.4) | 768 (18.5) | |

| 56–69 | 6564 (43.0) | 2109 (50.9) | |

| 70+ | 6668 (43.7) | 1265 (30.5) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.14 | ||

| Male | 7679 (50.3) | 2137 (51.6) | |

| Female | 7594 (49.7) | 2005 (48.4) | 0.14 |

| Race/ Ethnicity, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| White Non-Hispanic | 12,224 (80.0) | 3461 (83.6) | |

| Black | 1463 (9.6) | 356 (8.6) | |

| White Hispanic | 600 (3.9) | 123 (3.0) | |

| Asian Pacific Islander | 411 (2.7) | 70 (1.7) | |

| Native American/Other/Unknown/Missing | 575 (3.8) | 132 (3.2) | |

| Insurance Status, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Uninsured | 274 (1.8) | 58 (1.4) | |

| Private | 5197 (34.0) | 1787 (43.1) | |

| Public/Government | 9653 (63.2) | 2234 (53.9) | |

| Other/Unknown | 149 (1.0) | 63 (1.5) | |

| Average Income, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| < $40,227 | 2292 (15.0) | 534 (12.9) | |

| $40,227 - $50,353 | 3006 (19.7) | 816 (19.7) | |

| $50,354 - $63,332 | 3247 (21.3) | 866 (20.9) | |

| $63,333+ | 5514 (36.1) | 1358 (32.8) | |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 1214 (7.9) | 568 (13.7) | |

| Average Education, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| >=17.6% | 2562 (16.8) | 540 (13.0) | |

| 10.9%−17.5% | 3550 (23.2) | 827 (20.0) | |

| 6.3%−10.8% | 4072 (26.7) | 1148 (27.7) | |

| <6.3% | 3898 (25.5) | 1064 (25.7) | |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 1191 (7.8) | 563 (13.6) | |

| Hospital Type, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Community Cancer Program | 512 (3.4) | 103 (2.5) | |

| Comprehensive Community Cancer Program | 4270 (28.0) | 822 (19.8) | |

| Academic | 8303 (54.4) | 2708 (65.4) | |

| Integrated Network Cancer Program | 2087 (13.7) | 473 (11.4) | |

| Other/Unknown | 101 (0.7) | 36 (0.9) | |

| Hospital Type, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Non-Academic (Community Cancer Program/ Comprehensive Community Cancer Program/Integrated Network Cancer Program) | 6869 (45.0) | 1398 (33.8) | |

| Academic | 8303 (54.4) | 2708 (65.4) | |

| Other/Unknown | 101 (0.7) | 36 (0.9) | |

| Hospital Location, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Northeast | 3397 (22.2) | 1053 (25.4) | |

| South | 5565 (36.4) | 1336 (32.3) | |

| Midwest | 4085 (26.7) | 1219 (29.4) | |

| West | 1562 (10.2) | 358 (8.6) | |

| Other/Unknown | 664 (4.3) | 176 (4.2) | |

| Population Density, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Metro | 12,456 (81.6) | 3227 (77.9) | |

| Urban | 1997 (13.1) | 666 (16.1) | |

| Rural | 257 (1.7) | 73 (1.8) | |

| Other/Unknown/Missing | 563 (3.7) | 176 (4.2) | |

| Comorbidity Score, n (%) | 0.10 | ||

| 0 | 9673 (63.3) | 2690 (64.9) | |

| 1 | 4155 (27.2) | 1095 (26.4) | |

| >=2 | 1445 (9.5) | 357 (8.6) | |

| TNM Clinical Stage, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| I | 8130 (53.2) | 1282 (31) | |

| II | 7143 (46.8) | 2860 (69.0) | |

| TNM Clinical T, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 2830 (18.5) | 281 (6.8) | |

| T2 | 6478 (42.4) | 1360 (32.8) | |

| T3 | 5965 (39.1) | 2501 (60.4) | |

| TNM Clinical N, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 11,838 (77.5) | 2926 (70.6) | |

| N1 | 3435 (22.5) | 1216 (29.4) | <0.001 |

| Primary Site, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| head/neck | 11,582 (75.8) | 3544 (85.6) | |

| Body | 1396 (9.1) | 359 (8.7) | |

| Tail | 2295 (15.0) | 239 (5.8) | |

| Surgery Type, n(%) | <0.001 | ||

| Whipple | 12,035 (78.8) | 3591 (86.7) | |

| Local excision | 52 (0.3) | 24 (0.6) | |

| Partial/Distal | 2932 (19.2) | 466 (11.3) | |

| NOS | 254 (1.7) | 61 (1.5) | |

| Tumor Extension, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Localized | 2353 (15.4) | 566 (13.7) | |

| Peripancreatic | 8650 (56.6) | 1402 (33.8) | |

| Stomach | 370 (2.4) | 47 (1.1) | |

| Vascular | 658 (4.3) | 785 (19.0) | |

| Other/Unknown | 3242 (21.2) | 1342 (32.4) | |

| Regional Nodes examined, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 −14 | 6500 (42.6) | 1590 (38.4) | |

| >=15 | 8675 (56.8) | 2495 (60.2) | |

| Unknown | 98 (0.6) | 57 (1.4) | |

| Regional Nodes Positive, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 4848 (31.7) | 1946 (47.0) | |

| 1+ | 10,053 (65.8) | 1980 (47.8) | |

| Nx | 372 (2.4) | 216 (5.2) | |

| Resection Margin, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Negative | 11,771 (77.1) | 3304 (79.8) | |

| Positive | 3205 (21.0) | 699 (16.9) | |

| Unknown | 297 (1.9) | 139 (3.4) | |

| Grade, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| I-II (Well moderated differentiated) | 9137 (59.8) | 1639 (39.6) | |

| III-IV (Poor or undiferentiated) | 5291 (34.6) | 795 (19.2) | |

| Other | 845 (5.5) | 1708 (41.2) | |

| Surgery Discharge Days, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| <6 days | 2866 (18.8) | 697 (16.8) | |

| 6–7 days | 3549 (23.2) | 1059 (25.6) | |

| 8–182 days | 7398 (48.4) | 1829 (44.2) | |

| Unknown | 1460 (9.6) | 557 (13.4) | |

| TNM Pathologic T, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| T1 | 842 (5.5) | 520 (12.6) | |

| T2 | 1781 (11.7) | 483 (11.7) | |

| T3 | 12,160 (79.6) | 2827 (68.3) | |

| T4 | 177 (1.2) | 58 (1.4) | |

| Tx | 313 (2.0) | 254 (6.1) | |

| TNM Pathologic N, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| N0 | 4913 (32.2) | 1942 (46.9) | |

| N1 | 9966 (65.3) | 1968 (47.5) | |

| Nx | 394 (2.6) | 232 (5.6) | |

| Tumor Size, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0–9cm | 1734 (11.4) | 398 (9.6) | |

| 2–4 cm | 9983 (65.4) | 2923 (70.6) | |

| >4cm | 3529 (23.1) | 812 (19.6) | |

| Unknown | 27 (0.2) | 9 (0.2) | |

| Lymph/Vascular Invasion, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | 6569 (43.0) | 1887 (45.6) | |

| Present | 6993 (45.8) | 1198 (28.9) | |

| Unknown | 1711 (11.2) | 1057 (25.5) | |

| Scope of Reg LN Surgery, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No regional lymph node surgery | 323 (2.1) | 108 (2.6) | |

| Regional lymph node surgery | 14,880 (97.4) | 3984 (96.2) | |

| Unknown | 70 (0.5) | 50 (1.2) | |

| CA 19–9, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| < 37 u/mL | 3360 (22.0) | 853 (20.6) | |

| >= 37 u/mL | 6065 (39.7) | 2162 (52.2) | |

| Unknown | 5848 (38.3) | 1127 (27.2) | |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 4094 (26.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Yes | 10,594 (69.4) | 4142 (100.0) | |

| Unknown | 585 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Chemotherapy Regimen, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Single Agent | 6940 (45.4) | 842 (20.3) | |

| Multi Agent | 3096 (20.3) | 3154 (76.1) | |

| Yes | 558 (3.7) | 146 (3.5) | |

| No | 4094 (26.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unknown | 585 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Radiation Administration, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 10,519 (68.9) | 1708 (41.2) | |

| Yes | 4341 (28.4) | 2308 (55.7) | |

| Missing | 413 (2.7) | 126 (3) | |

| Radiation/Surgery Sequence, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| None | 10,795 (70.7) | 1799 (43.4) | |

| Postop | 4260 (27.9) | 552 (13.3) | |

| Preop | 56 (0.4) | 1771 (42.8) | |

| Intraoperative/unknown | 162 (1.1) | 20 (0.5) | |

| Readmission to the Same Hospital within 30 Days of Surgical Discharge, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 13,595 (89) | 3789 (91.5) | |

| Yes | 1387 (9.1) | 261 (6.3) | |

| Unknown | 291 (1.9) | 92 (2.2) | |

| 30 Day Mortality, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Alive | 14,840 (97.2) | 4064 (98.1) | |

| Deceased | 398 (2.6) | 65 (1.6) | |

| NA | 35 (0.2) | 13 (0.3) | |

| 90 Day Mortality, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| Alive | 14,396 (94.3) | 3958 (95.6) | |

| Deceased | 787 (5.2) | 159 (3.8) | |

| NA | 90 (0.6) | 25 (0.6) | |

| Mortality, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No | 4374 (28.6) | 1565 (37.8) | |

| Yes | 10,899 (71.4) | 2577 (62.2) |

Predictors of receipt of NAC, positive resection margin and positive lymph nodes

The use of NAC gradually increased over the study time period (Fig. 2). In 2010, 12% of early stage PDAC received NAC compared to 33% of patients in 2016. After adjusting for confounding factors, lack of insurance, non-white race/ethnicity, and treatment at a non-academic center significantly decreased the likelihood of receiving NAC (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Number (Left) and percentage (Right) in the utilization of neoadjuvant chemotherapy among patients with pancreatic cancer over time.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis for predictors associated with use of NAC.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value | OR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p-value | |

| AGE, years, continuous | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | <0.001 | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Age, years, categorical | ||||||||

| 18–55 | ||||||||

| 56–69 | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 0.007 | ||||

| 70+ | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.62 | <0.001 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | ||||||||

| Female | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.029 | 0.95 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.439 |

| Race/ Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White Non-Hispanic | ||||||||

| Black | 0.73 | 0.59 | 0.92 | 0.006 | 0.72 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 0.006 |

| White Hispanic | 0.73 | 0.51 | 1.04 | 0.081 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.99 | 0.043 |

| Asian Pacific Islander | 0.52 | 0.33 | 0.84 | 0.008 | 0.46 | 0.28 | 0.74 | 0.002 |

| Other/Unknown | 0.79 | 0.56 | 1.10 | 0.158 | 0.78 | 0.55 | 1.11 | 0.169 |

| Insurance Status | ||||||||

| Uninsured | ||||||||

| Private | 1.23 | 0.76 | 1.98 | 0.403 | 1.38 | 0.84 | 2.27 | 0.200 |

| Public/ Government | 0.92 | 0.57 | 1.49 | 0.741 | 1.58 | 0.96 | 2.61 | 0.074 |

| Other/Unknown | 1.93 | 0.95 | 3.91 | 0.067 | 2.61 | 1.25 | 5.45 | 0.011 |

| Average Income | ||||||||

| < $40,227 | ||||||||

| $40,227 - $50,353 | 1.21 | 0.98 | 1.50 | 0.075 | 1.26 | 1.01 | 1.57 | 0.043 |

| $50,354 - $63,332 | 1.27 | 1.03 | 1.56 | 0.023 | 1.31 | 1.05 | 1.63 | 0.017 |

| $63,333+ | 1.05 | 0.87 | 1.27 | 0.617 | 1.16 | 0.94 | 1.44 | 0.169 |

| Other/Unknown | 1.78 | 1.41 | 2.26 | <0.001 | 2.06 | 1.61 | 2.65 | <0.001 |

| Average Education | ||||||||

| >=17.6% | ||||||||

| 10.9%−17.5% | 1.18 | 0.96 | 1.45 | 0.126 | ||||

| 6.3%−10.8% | 1.36 | 1.11 | 1.66 | 0.003 | ||||

| <6.3% | 1.29 | 1.06 | 1.58 | 0.012 | ||||

| Other/Unknown | 1.96 | 1.55 | 2.48 | <0.001 | ||||

| Hospital Type | ||||||||

| Non-Academic | ||||||||

| Academic | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.58 | <0.001 | 1.43 | 1.26 | 1.62 | <0.001 |

| Other/Unknown | 1.33 | 0.68 | 2.63 | 0.405 | 0.69 | 0.33 | 1.42 | 0.316 |

| Hospital Location | ||||||||

| Northeast | ||||||||

| South | 0.76 | 0.65 | 0.89 | 0.001 | ||||

| Midwest | 1.03 | 0.88 | 1.21 | 0.673 | ||||

| West | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.85 | 0.001 | ||||

| Other/Unknown | 0.70 | 0.51 | 0.97 | 0.031 | ||||

| Population Density | ||||||||

| Metro | ||||||||

| Urban | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.66 | <0.001 | 1.32 | 1.10 | 1.57 | 0.002 |

| Rural | 1.17 | 0.76 | 1.80 | 0.465 | 1.09 | 0.70 | 1.71 | 0.695 |

| Other/Unknown | 1.26 | 0.94 | 1.69 | 0.119 | 1.13 | 0.84 | 1.54 | 0.418 |

| Charleston Comorbidity Score | ||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||

| >=1 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.07 | 0.351 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.11 | 0.773 |

| TNM Clinical T, n (%) | ||||||||

| T1 | ||||||||

| T2 | 2.18 | 1.88 | 2.54 | <0.001 | 2.27 | 1.95 | 2.65 | <0.001 |

| T3 | 4.51 | 2.57 | 7.92 | <0.001 | 4.88 | 2.72 | 8.76 | <0.001 |

| TNM Clinical N, n (%) | ||||||||

| N0 | ||||||||

| N1 | 0.85 | 0.30 | 2.40 | 0.752 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 1.47 | 0.207 |

| Primary Site, n(%) | ||||||||

| Head/Neck | ||||||||

| Body | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.82 | <0.001 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.008 |

| Tail | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.44 | <0.001 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.45 | <0.001 |

| CA 19–9 | ||||||||

| < 37 u/mL | ||||||||

| >= 37 u/mL | 1.35 | 1.16 | 1.57 | <0.001 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.43 | 0.012 |

| Unknown | 0.71 | 0.60 | 0.84 | <0.001 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.83 | <0.001 |

Utilization of NAC led to a 13% risk reduction of a positive resection margin when compared to upfront surgery (adjusted odds radio [aOR]:0.87; 95%CI 0.78–0.97) after controlling for demographic, clinical and pathological risk factors. Moreover, patients who received NAC had a 59% decreased risk of positive lymph nodes at the time of surgery (aOR 0.41; 95%CI 0.38–0.45).

Survival analysis

In the univariate analyses, the median OS for all patients treated with NAC was 2.56 years compared to 1.95 years for patients for patients that had upfront surgery +/- AC (p < 0.001). When stratified by stage, stage I patents had a median OS of 2.69 years with NAC compared to 2.20 years for surgery +/- AC (p < 0.001), and for stage II patients, median OS was 2.49 years with NAC compared to 1.75 years for surgery +/- AC (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2A, C, E). In a subgroup analysis for the comparison of OS between patients who had NAC and those who had both surgery and AC, the median OS remained significantly longer for patients treated with NAC for both stages I and II (Supplementary Fig. 2B, D, F). Univariate analysis of factors associated with OS are listed in supplemental Table 1.

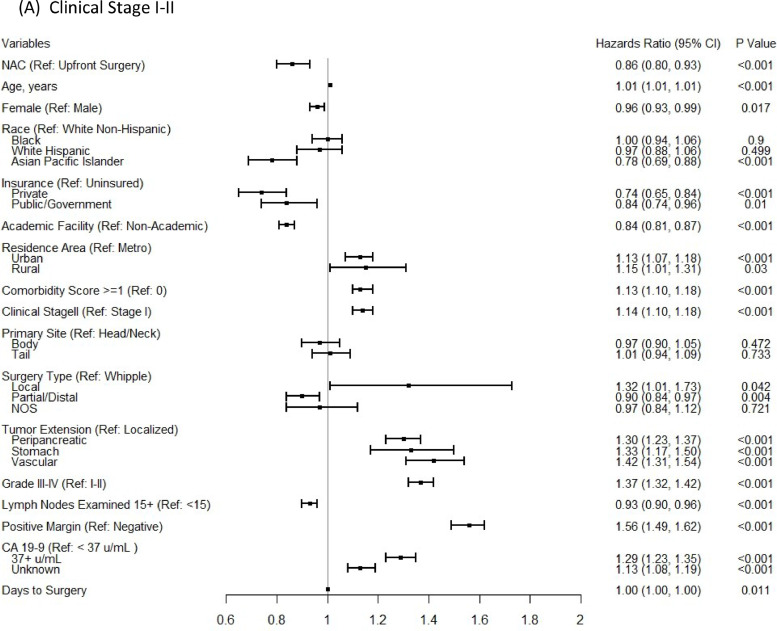

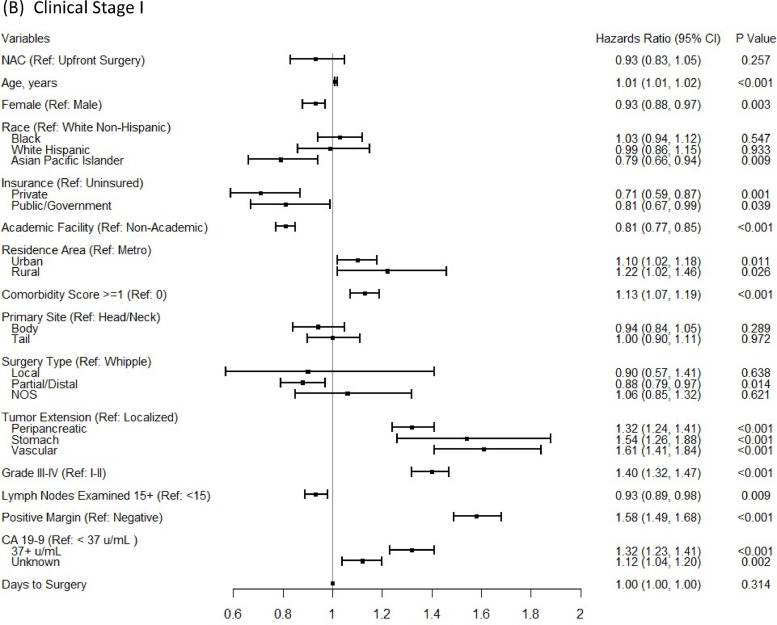

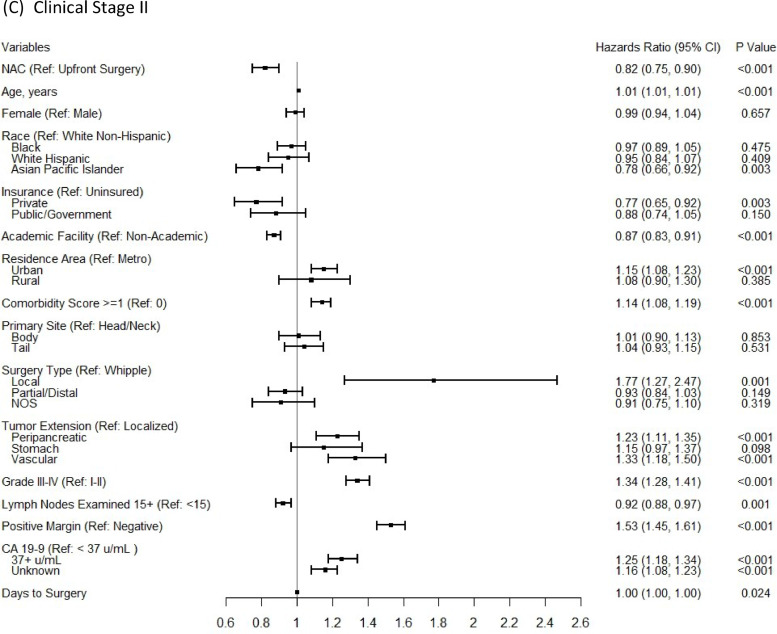

In the multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses, NAC was associated with significantly improved OS for stage II (aHR:0.82; 95%CI 0.75–0.90), but not for stage I patients (aHR:0.93; 95%CI 0.83–1.05), after controlling for patient, tumor, treatment-related factors, and time to surgery (Fig. 3). In a subgroup analysis for the comparison of OS between patients who had NAC and those who had both surgery and AC, the survival benefit of NAC remained for stage II patients (aHR:0.80; 95%CI 0.76–0.84) and there was still no significant OS benefit from NAC for stage I patients. In addition, the conclusion based on a 6-month conditional landmark analyses in both multivariable Cox proportional-hazards regression analyses (Supplementary Fig. 3) and the Cox regression with IPTW using propensity score method, on the same set of covariates (Supplementary Fig. 4) remained the same.

Fig. 3.

Multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models for comparing overall survival between NAC versus upfront surgery groups for clinical stage I-II (A), clinical stage I (B) patients, and clinical stage II (C) patients.

Discussion

Surgical management of resectable PDAC offers patients the only chance of cure, though even for patients with an R0 resection, the five year survival rate is less than 20% [11]. The present study, as well as findings from smaller and/or older series, show that use of NAC allows more patients to undergo systemic treatment for a disease that is known to have high distant failure rates and could be considered a systemic process at the time of diagnosis, even in the resectable setting. Moreover, NAC appears to not only downstage nodal disease, but also lead to a more complete surgical resection, increasing the chance of an R0 resection. The result is an association with improvement in survival for patients with early stage PDAC.

The positive effect of administration of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting for resected PDAC has been studied in numerous trials. The biology of PDAC is the key factor in patient survival. The CONKO-001 trial evaluated the effect of adjuvant gemcitabine in patients undergoing complete tumor resection compared to a control group and found an improved disease-free survival from 6.7 to 13.4 months (P<0.001). They also found an improvement in five-year OS from 10.4% to 20.7% (p = 0.01) [12]. Another trial evaluated the effect of adjuvant fluorouracil and radiation in the treatment of PDAC. Although the effect of radiation was insignificant, the benefit of AC remained significant after adjustment for major prognostic factors and improved five-year survival from 8% to 21% (P = 0.009) [13]. The recent landmark trial PRODIGE established the use of modified FOLFIRINOX compared to gemcitabine alone in the treatment of PDAC. This trial demonstrated an improvement in DFS from 12.8 to 21.6 months (P<0.001) and an improvement in median OS from 35.0 to 54.4 months (P = 0.003) [14]. All of these studies demonstrate the efficacy of AC in the treatment of resected PDAC. We believe these examples demonstrate the need for both a local and systemic approach to this tumor type as highlighted by the survival benefit conferred in each study. We know that surgery alone is an effective and viable options in certain tumor types, however PDAC is one that cannot be most effectively treated for cure by single modality therapy.

The major limitation of the administration of AC for PDAC is the significant morbidity associated with pancreatic surgery. One retrospective study demonstrated that out of 203 patients, 38% of patients never initiated therapy [15]. A similar study found that only 58% of patients completed multimodality therapy after a surgery first approach in resectable PDAC [16]. One of the most striking arguments for the role of NAC for resectable PDAC is that a significant number of patients will lose the opportunity to undergo standardized chemotherapy treatment following surgery because of post-operative complications. Although our study demonstrated that there was no difference seen in OS for stage I patients who were able to undergo upfront surgery and treatment with AC as compared to those that underwent NAC and surgery, we also showed that from an intention to treat viewpoint, NAC led to a significant OS benefit for patients as compared to patients who had upfront surgery, since not all made it to receive AC.

Our study also demonstrates a decrease in the rate of positive lymph nodes and positive resection margins at the time of surgery. Having a positive resection margin in the surgical management of PDAC has been shown to have a significant reduction in both disease free and OS [17]. The finding of pathologically positive lymph nodes has also been shown to influence prognosis, with one study demonstrating a decrease in five-year OS from 39.8% in pN0 patients, to 21.0% in pN1a, to 11.4% in pN1b patients [18]. The PREOPANC study evaluated resectable and borderline resectable patients treated with neoadjuvant gemcitabine and radiation followed by adjuvant gemcitabine versus patients treated with only adjuvant gemcitabine. Their results showed an improvement in R0 resection rate from 40% to 71% (P< 0.001) and of those patients with an R0 resection, there was improvement in OS compared to those patients with a non-R0 resection (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.31 to 0.72; P<0.001). They also found that neoadjuvant therapy led to fewer positive pathologic lymph nodes (33% vs 78%; P<0.001), less perineural invasion (39% vs. 73%; P<0.001), and less venous invasion (19% vs. 36%; P = 0.024) [19]. Like ours, these studies demonstrate the importance of tumor downstaging prior to surgical intervention and the associated implications for long term prognosis.

One potential concern with the use of NAC is losing the ability to perform a surgical resection because of tumor progression or complications from therapy. However, randomized trials have not shown great differences in the number of patients that undergo pancreatic resection with NAC as compared to upfront surgery. One study showed that NAC patients had a resection rate of 77% compared to a resection rate of 72% in patients with planned upfront surgery [20]. A further argument for a chemotherapy first approach is that patients who progress on NAC would likely not benefit from upfront surgical resection secondary to the aggressive biological nature of their tumors. (Supplementary Fig. 1) Therefore, NAC may provide an in vivo selection test for patients who may derive a benefit from any surgical intervention. One of the key components of performing pancreatic surgery is selecting for those patients which derive the greatest benefit. Surgical intervention on the pancreas can be associated with significant morbidity. Assessing the biologic responsiveness of the tumor to systemic chemotherapy may aid surgeons in selecting against patients who may not have a significant survival benefit from surgery.

There are several limitations to our study, including the inherent limitations of the NCDB and any retrospective database. Although disease-free survival is not available in the NCDB, for a highly aggressive cancer such as PDAC, OS is a useful and reasonable measure of outcome. For the current study, the exact regimen of chemotherapy administered during treatment is unknown and there is also no standardization of surgical technique. Both of these factors may influence the overall oncologic and survival outcomes. Another limitation is the assumption of resectable pancreatic cancer as compared to borderline or locally advanced pancreatic cancer in the clinical staging of these patients that we reused in the selection criteria. We also would like to acknowledge that some patients are unable to tolerate multimodality treatment secondary to patient specific comorbidities. These patients should be managed in a way that provides maximum benefit for their individual situation. We originally began this study as an update from previous NCBD publications, and we do acknowledge that similar studies to this have been performed between the time of the onset of our work and the publication of this paper. However, we feel that our data supports the findings of other papers that have used the NCDB to examine the outcomes in this patient population and thus adds more support to a growing body of research in this area.

Conclusion

Use of NAC for early stage PDAC has increased over the past decade. NAC appears to independently be associated with improved survival for most early stage PDAC patients as well as be associated with improved surgical oncological outcomes. Therefore, NAC should be considered for all early stage PDAC patients. Ongoing randomized trials will further our understanding of the exact subset of patients who will most benefit from NAC.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We confirm that none of the authors listed below have conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.sipas.2022.100136.

Contributor Information

Wade Christopher, Email: wchristopher@umc.edu.

Melanie Goldfarb, Email: melanie.goldfarb@providence.org.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2018. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: incidence - SEER Research Data, 13 Registries, Nov 2020 Sub (1975-2018) - Linked To County Attributes - Time Dependent (1990-2018) Income/Rurality, 1969-2019 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2021, based on the November 2020 submission.

- 3.Gillen S., Schuster T., Meyer, et al. Preoperative/neoadjuvant therapy in pancreatic cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of response and resection percentages. PLoS Med. 2010;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma 2.2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf. 24 May 2021.

- 5.Murphy J.E., Wo J.Y., Ryan D.P., et al. Total Neoadjuvant Therapy With FOLFIRINOX followed by individualized chemoradiotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a Phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2018 Jul 1;4(7):963–969. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.0329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla A., Molina G., Pak L.M., et al. Neoadjuvant Therapy is Associated with Improved Survival in Borderline-Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(4):1191–1200. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-08087-z. Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayo S.C., Gilson M.M., Herman J.M., et al. Management of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: national trends in patient selection, operative management, and use of adjuvant therapy. J Am cColl Surg. 2012;214:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groot V.P., Rezaee N., Wu W., et al. Patterns, Timing, and Predictors of Recurrence Following Pancreatectomy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):936–945. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002234. May. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mokdad A.A., Minter R.M., Zhu H., et al. Neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection versus upfront resection for resectable pancreatic cancer: a propensity score matched analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Feb 10;35(5):515–522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boffa D.J., Rosen J.E., Mallin K., et al. Using the national cancer database for outcomes research: a review. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1722–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klinkenbijl J.H., Jeekel J., Sahmoud T., et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg. 1999;230(6):782–784. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199912000-00006. 776-82discussion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oettle H., Neuhaus P., Hochhaus A., et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1473–1481. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.279201. Oct 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neoptolemos J.P., Stocken D.D., Friess H., et al. European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 Mar 18;350(12):1200–1210. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conroy T., Hammel P., Hebbar M., et al. Canadian Cancer Trials Group and the Unicancer-GI–PRODIGE Group. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 20;379(25):2395–2406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Labori K.J., Katz M.H., Tzeng C.W., et al. Impact of early disease progression and surgical complications on adjuvant chemotherapy completion rates and survival in patients undergoing the surgery first approach for resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma - A population-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(3):265–277. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1068445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tzeng C.W., Tran Cao H.S., Lee J.E., et al. Treatment sequencing for resectable pancreatic cancer: influence of early metastases and surgical complications on multimodality therapy completion and survival. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18(1):16–24. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2412-1. Jan. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghaneh P., Kleeff J., Halloran C.M., et al. European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer. The Impact of Positive Resection Margins on Survival and Recurrence Following Resection and Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2019;269(3):520–529. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002557. Mar. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tarantino I., Warschkow R., Hackert T., et al. Staging of pancreatic cancer based on the number of positive lymph nodes. Br J Surg. 2017;104(5):608–618. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10472. Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Versteijne E., Suker M., Groothuis K., et al. Preoperative Chemoradiotherapy Versus Immediate Surgery for Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: results of the Dutch Randomized Phase III PREOPANC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Jun 1;38(16):1763–1773. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motoi F., Kosuge T., Ueno H., et al. Randomized phase II/III trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 versus upfront surgery for resectable pancreatic cancer (Prep-02/JSAP05) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2019 Feb 1;49(2):190–194. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyy190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.