Abstract

The synthetic cubane-type iron–sulfur clusters [Fe4S4(SR)4]z form a four-member electron transfer series (z = 3–, 2–, 1–, and 0), all members of which except that with z = 0 have been isolated and characterized. They serve as accurate analogues of protein-bound [Fe4S4(SCys)4]z redox centers, which, in terms of core oxidation states, exhibit the redox couples [Fe4S4]3+/2+ and [Fe4S4]2+/1+. Clusters with the all-ferrous core [Fe4S4]0 have never been isolated because of their oxidative sensitivity. Recent work on the Fe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase has demonstrated the formation of the all-ferrous state upon reaction with a strong reductant. Treatment of the cyanide cluster [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– with K[Ph2CO] in acetonitrile/tetrahydrofuran affords the all-ferrous cluster [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–, isolated as the Bu4N+ salt. The x-ray structure demonstrates retention of a cubane-type structure with idealized D2d symmetry. The Mössbauer spectrum unambiguously demonstrates the [Fe4S4]0 oxidation state. Bond distances, core volumes, 57Fe isomer shifts, and visible absorption spectra make evident the high degree of structural and electronic similarity with the fully reduced Fe protein. The attribute of cyanide ligation causes positive [Fe4S4]2+/1+ and [Fe4S4]1+/0 redox potential shifts, facilitating the initial isolation of an analogue of the [Fe4S4]0 protein site.

Keywords: iron–sulfur clusters, synthetic analogue, all-ferrous cluster

An extensive set of cubane-type clusters [Fe4S4(SR)4]3–,2–,1– (R = alkyl or aryl) has been prepared whose members serve as accurate analogues of the [Fe4S4(SCys)4] redox sites in ferredoxins and other iron–sulfur proteins (1, 2). In terms of core oxidation states, these clusters form the four-member electron transfer series 1 throughout which the cubane [Fe4(μ3-S)4] core

|

[1] |

is retained. The existence of this series was recognized by voltammetry at the beginning of iron–sulfur analogue chemistry (3). Because of the dependence of redox potential on substituent R of thiolate clusters and other ligands L in [Fe4S4L4]z clusters, the entire series has not been traversed electrochemically or synthetically at constant R or L, except for R = Ph in an unusual toluene/(Bu4N)(BF4) electrochemical phase (4). Many [Fe4S4]2+,1+ clusters (2) and one [Fe4S4]3+ species (5) have been isolated and subjected to detailed electronic and structural characterization. The [Fe4S4]2+/1+ couple ( to –0.7 V) is operative in many ferredoxins and other proteins, whereas the [Fe4S4]3+/2+ couple (

to –0.7 V) is operative in many ferredoxins and other proteins, whereas the [Fe4S4]3+/2+ couple ( V) occurs primarily in the smaller group of “high-potential” proteins. The all-ferrous [Fe4S4]0 state was not recognized to be potentially physiologically relevant until relatively recently. Further, numerous attempts to isolate all-ferrous [Fe4S4]0 species that are members of the synthetic series 1 failed because of their pronounced susceptibility toward oxidation, as indicated by the potentials

V) occurs primarily in the smaller group of “high-potential” proteins. The all-ferrous [Fe4S4]0 state was not recognized to be potentially physiologically relevant until relatively recently. Further, numerous attempts to isolate all-ferrous [Fe4S4]0 species that are members of the synthetic series 1 failed because of their pronounced susceptibility toward oxidation, as indicated by the potentials  V and, especially,

V and, especially,  V vs. standard calomel electrode for [Fe4S4(SPh)4]2– in acetonitrile (6). However, after the initial assertion by Watt and Reddy (7) in 1994, spectroscopic data for the Fe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii reduced by TiIII(citrate) convincingly demonstrated attainment of the [Fe4S4]0 state (8–11). This protein is the electron donor to the catalytic MoFe protein of the nitrogenase complex (12). For this cluster,

V vs. standard calomel electrode for [Fe4S4(SPh)4]2– in acetonitrile (6). However, after the initial assertion by Watt and Reddy (7) in 1994, spectroscopic data for the Fe protein of Azotobacter vinelandii reduced by TiIII(citrate) convincingly demonstrated attainment of the [Fe4S4]0 state (8–11). This protein is the electron donor to the catalytic MoFe protein of the nitrogenase complex (12). For this cluster,  V (7) and

V (7) and  V (13). Retention of the cubane-type [Fe4S4(SCys)4] structure of the oxidized Fe protein with small dimensional changes has been established crystallographically (14). Evidence has been presented for a two-electron transfer by the fully reduced Fe protein in nitrogenase catalysis (15). Here, we demonstrate that the heretofore elusive all-ferrous state in a cubane-type cluster can be isolated in substance.

V (13). Retention of the cubane-type [Fe4S4(SCys)4] structure of the oxidized Fe protein with small dimensional changes has been established crystallographically (14). Evidence has been presented for a two-electron transfer by the fully reduced Fe protein in nitrogenase catalysis (15). Here, we demonstrate that the heretofore elusive all-ferrous state in a cubane-type cluster can be isolated in substance.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4]. Method A. All operations were carried out under strictly anaerobic and anhydrous conditions. To a mixture of 0.15 g (0.11 mmol) of [Fe4S4(PPri3)4](BPh4) (16), 0.5 ml of PPri3, and 1 ml of tetrahydrofuran (THF), K[Ph2CO] was added [freshly prepared from 5.7 mg (0.15 mmol) of potassium and 35 mg (0.19 mmol) of Ph2CO in 2 ml of THF]. The reaction mixture was filtered into a solution of 0.13 g (0.48 mmol) of (Bu4N)(CN) in 1 ml of THF. The solid that separated was collected and washed with ether and THF to afford the product as 0.13 g (75%) of a red microcrystalline solid.

Method B. A solution of 0.20 g (0.17 mmol) of (Bu4N)3[Fe4S4(CN)4] (17) and 0.042 g (0.15 mmol) of (Bu4N)Cl in 2 ml of acetonitrile was treated with K[Ph2CO] [freshly prepared from 7.0 mg (0.18 mmol) of potassium and 46 mg (0.25 mmol) of Ph2CO in 2 ml of THF]. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min and was filtered through a short Celite column. Vapor diffusion of ether into the deep red filtrate over 16 h followed by drying in vacuo gave the bulk product as 0.17 g (69%) of red plate-like crystals. Analysis indicated the composition as (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4]·½MeCN·KCl. Calculated for C69H145.5ClFe4KN8.5S4 was the following: C, 54.53 (54.31); H, 9.58 (9.79); S, 8.43 (8.08). The two products displayed identical Mössbauer spectroscopic properties.

X-Ray Structure Determination. A red crystal obtained from the reaction mixture of method B before the drying step was crystallographically analyzed on an Apex D8 CCD diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA) at 213 K. Diffraction data were consistent with the composition (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4]·2MeCN (Mr = 1507.66) in orthorhombic space group Pccn. The cell constants a = 31.295 (2) Å, b = 11.9272 (9) Å, c = 23.630 (2) Å, and V = 8820 (1) Å3 were retrieved (with smart) and refined (with saint) on all observed reflections. The structure was solved by direct methods using shelxl-97 (16, 17) (2θmax = 50.16° and μ = 0.780 cm–1) and was refined to the standard agreement factors R1 = 0.057, wR2 = 0.1425, and goodness-of-fit = 0.994.

Other Physical Measurements. Cyclic voltammograms were determined at a scan rate of 100 mV/s by using a Model 610A electrochemical analyzer (CH Instruments, Austin, TX) with a glassy carbon working electrode, 0.1 M (Bu4N)(PF6) supporting electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Potentials were corrected to the standard calomel electrode (SCE) (ESCE = EAg/AgCl – 0.04 V) to allow comparison with reported potentials of synthetic iron–sulfur clusters. Mössbauer spectra were recorded with a constant acceleration spectrometer. Data were analyzed with wmoss software (WEB Research, Edina, MN); isomer shifts are referenced to iron metal at room temperature.

Results and Discussion

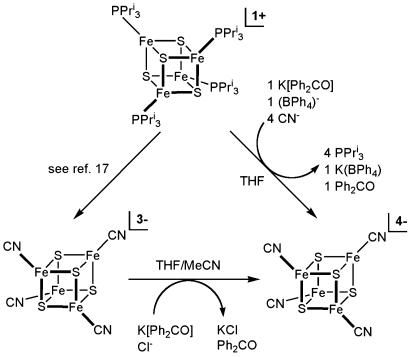

Synthesis. The red all-ferrous cluster [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– has been prepared by the two methods in Fig. 1 and isolated as the Bu4N+ salt. Reduction of the previously reported cubane-type [Fe4S4]1+ clusters [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– (17) or [Fe4S4(PPri3)4]1+ in the presence of four equivalents of cyanide (and excess PPri3 to prevent formation of the double cubane [Fe8S8(PPri3)6]) (16) with potassium benzophenone ketyl affords the product in 69–75% yield. The key attribute is the use of electron-withdrawing cyanide ligands, which for [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– in dichloromethane cause substantial positive potential shifts compared with values for [Fe4S4(SPh)4]2–. For this cluster,  V and

V and  V. The second reduction potential is the same as that for the [Fe4S4]2+/1+ couple of [Fe4S4(SBut)4]2– in N,N-dimethylformamide (3); [Fe4S4(SBut)4]3–, a cluster of comparable oxidative sensitivity, has been isolated (18). Consequently, the potential shift of ≈0.3 V facilitates isolation of (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4], which, however, is so sensitive that despite numerous attempts, it cannot be recrystallized or maintained in solution in the absence of a reducing agent without partial oxidation of the cluster.

V. The second reduction potential is the same as that for the [Fe4S4]2+/1+ couple of [Fe4S4(SBut)4]2– in N,N-dimethylformamide (3); [Fe4S4(SBut)4]3–, a cluster of comparable oxidative sensitivity, has been isolated (18). Consequently, the potential shift of ≈0.3 V facilitates isolation of (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4], which, however, is so sensitive that despite numerous attempts, it cannot be recrystallized or maintained in solution in the absence of a reducing agent without partial oxidation of the cluster.

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–.

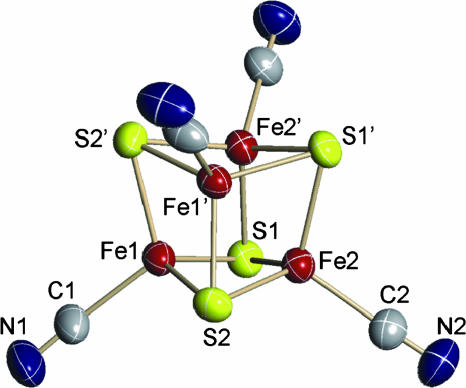

Structure. The desired cluster was obtained in red plate-like crystals of apparent composition (Bu4N)4[Fe4S4(CN)4]·2MeCN in orthorhombic space group Pccn. The anion and two cations reside on crystallographic twofold axes, and the other two cations are in general positions; the anion:cation ratio is 1:4. The cluster structure is depicted in Fig. 2; selected interatomic distances are collected in Table 1. The cluster has the usual cubane-type geometry (2, 19) consisting of two concentric interpenetrating Fe4 and S4 tetrahedra. A crystallographically imposed twofold axis bisects the opposite faces Fe(1,1′)S(2,2′) and Fe(2,2′)S(1,1′) of the [Fe4S4]0 core, resulting in six Fe–S [2.321(1)–2.364(1) Å] plus four Fe–Fe [2.627 (1)–2.696(1) Å] distances that are independent. These distances are within the normal intervals for Fe4S4 clusters. The FeII atoms exhibit distorted tetrahedral coordination with essential linear cyanide binding. The cluster approaches idealized D2d symmetry. We note that Fe4S4 core structures, especially [Fe4S4]1+, are subject to a variety of static distortions from limiting Td symmetry, arising from the exigencies of crystal packing, which are variant with cation and substituent R or ligand L. For example, [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– exhibits a small crystallographically imposed trigonal distortion (17).

Fig. 2.

Structure of [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– showing 50% probability ellipsoids and atom labeling scheme; primed and unprimed atoms are related by a twofold axis.

Table 1. Selected interatomic distances in Å, angles in degrees, and estimated standard deviations in parentheses for [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–

| Distance/angle | Value |

|---|---|

| Fe1-S1 | 2.325 Å (1) |

| Fe1-S2 | 2.364 Å (1) |

| Fe1-S2′ | 2.326 Å (1) |

| Fe1-C1 | 2.087 Å (5) |

| Fe1-Fe2 | 2.6756 Å (8) |

| Fe1-Fe1′ | 2.627 Å (1) |

| Fe2-S1 | 2.334 Å (1) |

| Fe2-S1′ | 2.337 Å (1) |

| Fe2-S2 | 2.321 Å (1) |

| Fe2-C2 | 2.076 Å (4) |

| Fe2-Fe1′ | 2.6825 Å (8) |

| Fe2-Fe2′ | 2.696 Å (1) |

| S1-Fe1-S2 | 106.34° (4) |

| S1-Fe1-S2′ | 105.91° (4) |

| S2-Fe1-S2′ | 109.24° (4) |

| C1-Fe1-S1 | 115.6° (1) |

| C1-Fe1-S2 | 104.9° (1) |

| C1-Fe1-S2′ | 114.5° (1) |

| Fe1-C1-N1 | 175.2° (5) |

| S1-Fe2-S2 | 107.48° (4) |

| S1-Fe2-S1′ | 106.79° (4) |

| S2-Fe2-S1′ | 105.68° (4) |

| C2-Fe2-S1 | 110.3° (1) |

| C2-Fe2-S1′ | 112.2° (1) |

| C2-Fe2-S2 | 114.0° (1) |

| Fe2-C2-N2 | 177.7° (4) |

Compared in Table 2 are bond distances and core volumes for the synthetic clusters [Fe4S4(CN)4]3–,4– and the Fe protein of the A. vinelandii nitrogenase complex. Upon reduction of the cyanide cluster, Fe–Fe distances and Fe4 core volumes change little, compared with the relatively large increase in Fe–S distances and S4 core volumes; this behavior is common in the [Fe4S4]2+/1+ redox transitions of thiolate-ligated clusters. For [Fe4S4(SR)4]2–, reported ranges are 2.41–2.49 Å3 for Fe4 and 5.28–5.55 Å3 for S4, and for [Fe4S4(SR)4]3–, the values are 2.38–2.50 Å3 for Fe4 and 5.74–5.80 Å3 for S4. The core total volumes increase slightly upon reduction, from 9.50–9.70 Å3 for [Fe4S4]2+ to 9.57–9.93 Å3 for [Fe4S4]1+ (18–23). The volumes in Table 2 were calculated from atomic coordinates (24) and indicate that the [Fe4S4]1+/0 transition results in similar changes. The Fe–Fe distances are not distinguishable, the Fe4 volume shows a slight apparent decrease, and Fe–S bond lengths and S4 volumes increase significantly. The core volume enlarges by 0.7% because of the increased S4 volume, which is the case in all other volume comparisons. From these observations, the added electron producing the all-ferrous state is described by an antibonding orbital with substantial sulfur character. Note the concordance between the metric features of the [Fe4S4]0 cluster and the fully reduced Fe protein.

Table 2. Comparison of selected interatomic distances in Å and volumes in Å3 for [Fe4S4(CN)4]3–/4– and the fully reduced Fe protein.

Cyanide Stretching Frequencies. The value of vCN decreases appreciably upon reducing [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– (2,103 cm–1) to [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– (2,050 cm–1). The most closely related situation occurs with K3[Fe(CN)6] and K4[Fe(CN)]6, for which vCN = 2,116 and 2,041 cm–1, respectively. To the extent that the trends in stretching frequencies are parallel, the data for the clusters support reduction to the all-ferrous state, in which there appears to be sufficient electron donation into the π* orbitals of the ligand to reduce vCN to <2,058 cm–1, the value for (Bu4N)(CN). All data refer to polycrystalline solids.

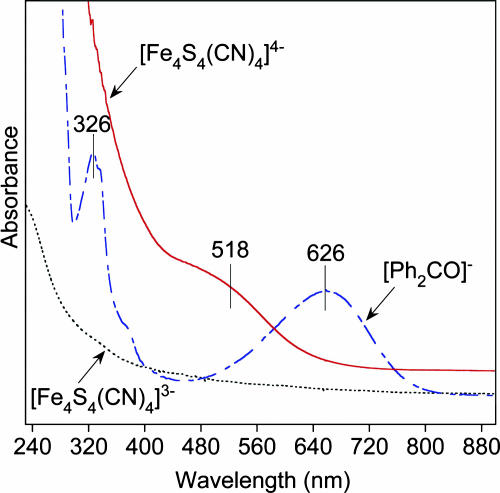

Visible Absorption Spectrum. A characteristic property associated with the reduction of the [Fe4S4]1+ state of the Fe protein to [Fe4S4]0 is a color change in aqueous buffer from brown to red, a decrease in absorbance over most of the visible spectrum, and the development of a band at 520 nm (8). Synthetic [Fe4S4(SR)4]3– clusters resemble protein-bound [Fe4S4]1+ clusters in displaying diminished absorbance at >≈400 nm (6). As may be seen in Fig. 3, [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– does not exhibit any discrete absorption bands throughout the UV-visible region. However, when this cluster is reduced with a small excess of K[Ph2CO] in acetonitrile/THF [1:1 (vol/vol)], the spectrum intensifies, and a prominent shoulder appears at ≈518 nm. This band is not due to the reductant, whose blue color arises from the feature at 626 nm. A cyclic voltammogram of this solution under an argon atmosphere at an initial potential of –1.5 V reveals oxidations at E1/2 = –1.18 V and –0.26 V, which correspond to the –1.42-V and –0.44-V steps in pure acetonitrile. Because of the extreme oxidative sensitivity of [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–, it was necessary to perform the absorption spectral and electrochemical measurements in situ. Although the visible absorption band in the protein and synthetic cluster is likely a ligand-to-metal charge transfer, it has not been assigned. Variable-temperature magnetic circular dichroism spectra of the Fe protein indicate that the band at ≈500 nm in aqueous buffer is associated with a ground spin state S > 2 (25).

Fig. 3.

UV-visible absorption spectra of [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– (dotted line) in acetonitrile and [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– (solid line) and K[Ph2CO] (dashed line) in acetonitrile/THF [1:1 (vol/vol)].

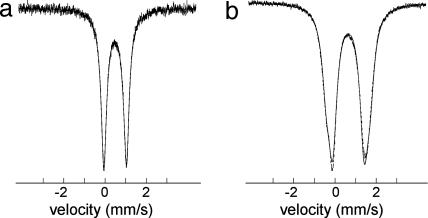

Mössbauer Spectra. Spectra of the two synthetic clusters are set out in Fig. 4; isomer shifts δ and quadrupole splittings ΔEQ are summarized in Table 3. Spectral fits to a single site or to two overlapping quadrupole doublets in an intensity ratio of 1:1 or 3:1 do not significantly alter the isomer shift. The spectrum of [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– at 4.2 K was reported as a 3:1 fit (17). At 77 K, a very good simulation is obtained by one quadrupole doublet with δ = 0.49 mm/s. When this value is applied to the empirical correlation δ = 1.43 – 0.40s between oxidation state s and isomer shift of [Fe4S4(SR)4]z clusters at 77 K (2), s = 2.35 compared with Fe2.25+ for [Fe4S4]1+. The clusters differ in one ligand of four, which in some cases measurably affects the isomer shift (26, 27). As one example at 77 K, δ = 0.51 mm/s for [Fe4S4Cl4]2– vs. δ = 0.43–0.44 mm/s for [Fe4S4(SBut)4]2– (28). The spectrum of [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– is equally well described by two doublets in a 1:1 or 3:1 intensity ratio, and δ = 0.65 mm/s for both. The empirical correlation suggests s = 1.95 vs. Fe2+ for [Fe4S4]0. Further, the isomer shift is in the range of tetrahedral FeII species such as [Fe(SR)4]2– and reduced rubredoxin, for which δ ≈ 0.70–0.76 mm/s at 77 K (29). The Mössbauer data are unequivocal in demonstrating the existence of an all-ferrous cluster. Note the close values of isomer shifts of the cluster and the Fe protein. However, unlike the Fe protein, the cluster does not display a zero-field spectrum consisting of two resolved quadrupole doublets in a 3:1 intensity ratio, with the less intense doublet corresponding to a site with a large quadrupole splitting (ΔEQ = 2.91 mm/s at 130 K), as does the Fe protein (11). At 4.2 K, [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– displays a complicated spectrum owing to the internal magnetic field of the cluster. The Mössbauer spectrum of the Fe protein has been interpreted in terms of an S = 4 ground state (11).

Fig. 4.

Zero-field Mössbauer spectra of [Fe4S4(CN)4]3– (a) and [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–(b) at 77 K; the solid lines are fits to the data using the parameters of Table 3.

Table 3. 57Fe Mössbauer parameters for [Fe4S4(CN)4]3–/4– and the fully reduced Fe protein.

Summary. To our knowledge, the foregoing structural and spectroscopic data establish [Fe4S4(CN)4]4– as the first example of an isolable all-ferrous cubane-type iron–sulfur cluster that is a member of the electron transfer series 1. The closest approach to this situation is the electrochemical detection of [Fe4S4(SR)4]4– and [Fe4S4(PR3)4]0 species. Multiple attempts to obtain the latter resulted in isolation of [Fe8S8(PR3)6], which, although all-ferrous, is an edge-bridged double cubane (16, 30). The present cluster is to be distinguished from [Fe4S4(CO)12], which has a cubane-type [Fe4S4]0 core, but with six-coordinate diamagnetic metal sites and a mean Fe···Fe distance of 3.47 Å (31). The cluster [Fe4S4(CN)4]4–, albeit with nonphysiological terminal ligands, is, to our knowledge, the first synthetic analogue of the fully reduced cluster in the Fe protein of nitrogenase. Overall, the properties of the latter, including core dimensions, the visible absorption band, and isomer shift, are closely approached. However, there are some differences in detail. There is no indication of a core distortion that, from extended x-ray absorption fine structure analysis, affords two short (2.52 Å) plus one long (2.77 Å) Fe–Fe distances and one short (2.29 Å) plus three long (2.35–2.37 Å) Fe–S distances (9). Further, there is no evidence from Mössbauer spectroscopy of a single iron site with a large quadrupole splitting that could be associated with discrete FeII. The cluster in the Fe protein is located between two subunits and is connected by two Fe–SCys interactions to each. It is this arrangement that produces the largest accessible surface area, which very likely contributes to the stability of the [Fe4S4]0 state (14) by means of solvent (hydrogen bonding) interactions that lead to fractional charge dissipation to the medium. It is not surprising that a cluster bound in this way may possess features that cannot be reproduced in a crystalline or solution phase that generates a far less anisotropic environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants ECS-0403669 and CHE-0449634 at Miami University and by National Institutes of Health Grant GM 28856 at Harvard University. The x-ray diffractometer was purchased through NSF Grant EAR-0003201.

Author contributions: H.-C.Z. designed research; T.A.S. and C.P.B. performed research; T.A.S., R.H.H., and H.-C.Z. analyzed data; and R.H.H. and H.-C.Z. wrote the paper.

Abbreviation: THF, tetrahydrofuran.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Cambridge Structural Database, Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, United Kingdom (CSD reference no. 271929).

References

- 1.Holm, R. H. (2004) in Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II: Biocoordination Chemistry, eds. Que, L., Jr., & Tolman, W. A. (Elsevier, London), Vol. 8, pp. 61–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao, P. V. & Holm, R. H. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104, 527–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DePamphilis, B. V., Averill, B. A., Herskovitz, T., Que, L., Jr., & Holm, R. H. (1974) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 4159–4167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pickett, C. J. (1985) J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun., 323–324.

- 5.O'Sullivan, T. & Millar, M. M. (1985) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 107, 4096–4097. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cambray, J., Lane, R. W., Wedd, A. G., Johnson, R. W. & Holm, R. H. (1977) Inorg. Chem. 16, 2565–2571. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watt, G. D. & Reddy, K. R. N. (1994) J. Inorg. Biochem. 53, 281–294. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angove, H. C., Yoo, S. J., Burgess, B. K. & Münck, E. (1997) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 8730–8731. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musgrave, K. B., Angove, H. C., Burgess, B. K., Hedman, B. & Hodgson, K. O. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 5325–5326. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angove, H. C., Yoo, S. J., Münck, E. & Burgess, B. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26330–26337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo, S. J., Angove, H. C., Burgess, B. K., Hendrich, M. P. & Münck, E. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 2534–2545. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgess, B. K. & Lowe, D. J. (1996) Chem. Rev. 96, 2983–3011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo, M., Sulc, F., Ribbe, M. W., Farmer, P. J. & Burgess, B. K. (2002) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 12100–12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strop, P., Takahara, P. M., Chiu, H.-J., Angove, H. C., Burgess, B. K. & Rees, D. C. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 651–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyborg, A. C., Johnson, J. L., Gunn, A. & Watt, G. D. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39307–39312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou, H.-C. & Holm, R. H. (2003) Inorg. Chem. 42, 11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott, T. A. & Zhou, H.-C. (2004) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5628–5631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagen, K. S., Watson, A. D. & Holm, R. H. (1984) Inorg. Chem. 23, 2984–2990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berg, J. M. & Holm, R. H. (1982) in Iron–Sulfur Proteins, ed. Spiro, T. G. (Wiley Interscience, New York), pp. 1–66.

- 20.Stephan, D. W., Papaefthymiou, G. C., Frankel, R. B. & Holm, R. H. (1983) Inorg. Chem. 22, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mascharak, P. K., Hagen, K. S., Spence, J. T. & Holm, R. H. (1983) Inorg. Chim. Acta 80, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carney, M. J., Papaefthymiou, G. C., Whitener, M. A., Spartalian, K., Frankel, R. B. & Holm, R. H. (1988) Inorg. Chem. 27, 346–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney, M. J., Papaefthymiou, G. C., Frankel, R. B. & Holm, R. H. (1989) Inorg. Chem. 28, 1497–1503. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaspar, J. S. & Lonsdale, K. (1967) in International Tables for X-Ray Crystallography (Kynoch, Birmingham, U.K.), 2nd Ed., Vol. 2, pp. 36–49. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo, S. J., Angove, H. C., Burgess, B. K., Münck, E. & Peterson, J. (1998) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 120, 9704–9705. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hauser, C., Bill, E. & Holm, R. H. (2002) Inorg. Chem. 41, 1615–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fomitchev, D. V., McLauchlan, C. C. & Holm, R. H. (2002) Inorg. Chem. 41, 958–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silver, J., Fern, G. R., Miller, J. R., McCammon, C. A., Evans, D. J. & Leigh, G. J. (1999) Inorg. Chem. 38, 4256–4261. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lane, R. W., Ibers, J. A., Frankel, R. B., Papaefthymiou, G. C. & Holm, R. H. (1977) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 99, 84–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goh, C., Segal, B. M., Huang, J., Long, J. R. & Holm, R. H. (1996) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11844–11853. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson, L. L., Lo, F. Y. K., Rae, A. D. & Dahl, L. F. (1982) J. Organomet. Chem. 225, 309–329. [Google Scholar]