Abstract

Aims

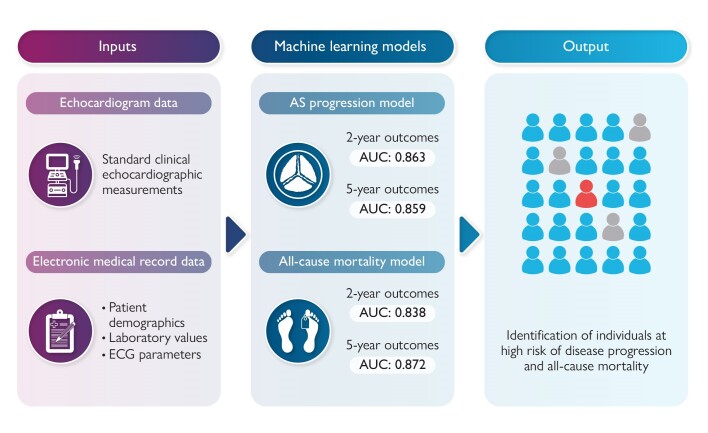

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a common and progressive disease, which, if left untreated, results in increased morbidity and mortality. Monitoring and follow-up care can be challenging due to significant variability in disease progression. This study aimed to develop machine learning models to predict the risks of disease progression and mortality in patients with mild AS.

Methods and results

A comprehensive database including 9611 patients with serial transthoracic echocardiograms was collected from a single institution across three clinical sites. The data set included parameters from echocardiograms, electrocardiograms, laboratory values, and diagnosis codes. Data from a single clinical site were preserved as an independent test group. Machine learning models were trained to identify progression to severe stenosis and all-cause mortality and tested in their performance for endpoints at 2 and 5 years. In the independent test group, the AS progression model differentiated those with progression to severe AS within 2 and 5 years with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.86 for both. The feature of greatest importance was aortic valve mean gradient, followed by other valve haemodynamic measurements including valve area and dimensionless index. The mortality model identified those with mortality within 2 and 5 years with an AUC of 0.84 and 0.87, respectively. Smaller reduced-input validation models had similarly robust findings.

Conclusion

Machine learning models can be used in patients with mild AS to identify those at high risk of disease progression and mortality. Implementation of such models may facilitate real-time, patient-specific follow-up recommendations.

Keywords: Artificial intelligence, Aortic stenosis, Echocardiography, Valve disease, Machine learning

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is a common valve disease in developed countries, accounting for a considerable healthcare burden, and due to an ageing population is expected to have an increasing prevalence. It is characterized by a fibrocalcific remodelling of the valve leaflets resulting in progressive narrowing of the aortic valve orifice and subsequent left ventricular (LV) remodelling. Even haemodynamically insignificant degrees of aortic valve fibrosis and calcification have been associated with cardiovascular mortality.1 In those that progress to a severe symptomatic stage, mortality is substantially increased without treatment.2

The rate of disease progression in AS is highly variable, both between individuals and throughout the disease process. Previous studies have suggested that <15% of patients with aortic valve sclerosis progress to valvular stenosis over the course of 2–7 years.3 Once AS is present, valve area has been estimated to decrease by an average of 0.1 cm2/year.3,4 Certain clinical and laboratory markers have been associated with more rapid progression; nonetheless, predicting rate of disease progression in a given patient remains difficult and prone to error.5 There is a particular paucity of data regarding the factors governing disease progression in mild AS. The variability in disease progression has implications on the timing of follow-up. While current guidelines based on population averages recommend follow-up of mild AS every 3–5 years, this frequently results in oversurveillance of patients with slow disease progression and risks missing clinically significant disease in others with an accelerated disease trajectory.

There has been growing adoption in the use of artificial intelligence to facilitate individualized care in medicine. Machine learning (ML), a subset of this field, can be used to analyse large databases and establish predictive models to help augment physician decision-making.6 Such models have been developed to help improve the diagnostic capabilities of echocardiography for conditions such as coronary artery disease and heart failure.7,8

Using the echocardiographic, electrocardiographic, and laboratory data and clinical variables of patients with mild AS, this study aimed to build and assess ML models: (i) to accurately predict AS progression to severe disease and (ii) to predict the risk of mortality in patients presenting with mild AS. The goal was to create models that include patient-specific risk factors that can be implemented in clinical practice to guide surveillance imaging and follow-up of patients with mild AS.

Methods

Data collection

This study utilized retrospective data from 1 January 2010 through 31 December 2021 extracted from Mayo Clinic electronic medical records (EMRs) and was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and only patients allowing access to their records for research were included. Included were patients diagnosed with mild AS who underwent one or more additional transthoracic echocardiograms at least 6 months later. Mild AS was defined by the presence of peak aortic valve velocity ≥2 m/s but <3 m/s and a description of abnormal aortic valve (calcified, bicuspid, stenotic, thickened, mild AS). To ensure that only patients with mild AS were captured, we excluded those that had a coded physician interpretation of moderate or severe AS severity or an aortic valve area (AVA) of ≤1.5 cm2. Other exclusion criteria included prior valve intervention, a history of heart transplant, subaortic membrane, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, or moderate or severe aortic valve regurgitation. These criteria were applied using a combination of coded impression statements in echocardiogram reports and implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and procedural codes indicative of prior heart transplant or valve intervention. Echocardiography was performed according to clinical practice. Indications for index echocardiogram are provided in Supplementary material online, Table S1. A comprehensive set of echocardiographic parameters was collected for all serial studies (see Supplementary material online, Table S2).

Additional variables including vital signs, medical history, laboratory, and electrocardiographic data were used for training the predictive models. Variables from each echocardiogram with mild AS were recorded, and vital signs were measured at the time of the echocardiogram. Patient diagnoses were obtained from the EMR using registered ICD9 and ICD10 codes. All diagnosis data from 2 years prior to the index echocardiogram through the follow-up period were included. Laboratory and electrocardiographic data obtained up to 5 years prior to each echocardiogram were also used as input for the model development (see Supplementary material online, Tables S3 and S4).

Processing and endpoints

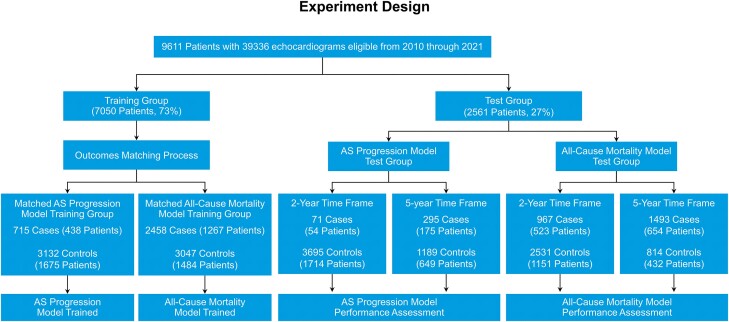

Eligible patients from across three Mayo Clinic campuses (Rochester, Jacksonville, and Scottsdale) were included (Figure 1). The training group consisted of patients from the Rochester and Jacksonville campuses (7050 patients, 73.4%). Patients from the Scottsdale campus were reserved for the testing group (2561 patients, 26.6%). This allowed for an unbiased evaluation of the final models in a different geographically based population who underwent echocardiographic and clinical assessment by an independent medical team. An additional validation group was not utilized as all hyperparameter tuning was done within the training group using a cross-validation technique. Endpoints were the development of severe AS and all-cause mortality.

Figure 1.

Experiment design. From a total of 9611 patients from 3 sites, 7050 from 2 sites were used for training and those from a third geographically distinct site were reserved for testing. Patient selection. Nine thousand six hundred and eleven patients were divided into training and testing data sets. The training data set was resampled to make incidence independent of time of sample. An aortic stenosis progression model and an all-cause mortality model were trained on the matched training data set. The testing data set was then used to assess these models for 2- and 5-year outcomes.

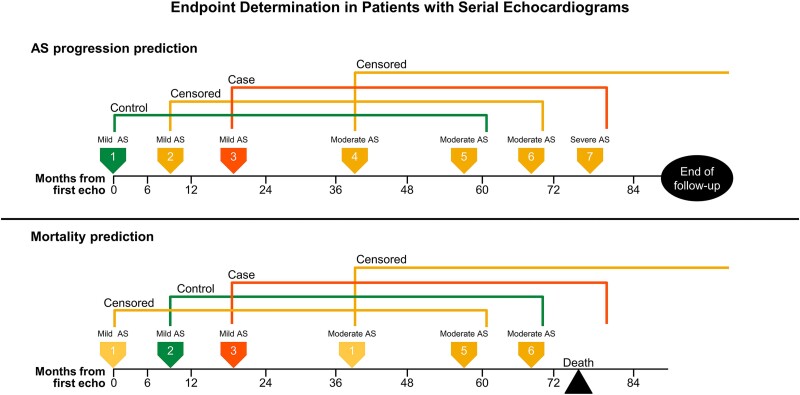

In cases where a patient underwent multiple echocardiograms before reaching an endpoint, the serial studies were used as new baseline echocardiograms or prediction points (Figure 2). Specifically, all echocardiograms in which AS remained mild were used as prediction points to train the model. At each prediction point, patient features were extracted from that echocardiogram as well as from electrocardiograms, laboratory values, and diagnosis codes. Diagnosis codes were consolidated using the inherent ICD hierarchical structure. Additional feature processing of data included signal names unification, units’ transformation, and an application of functions on a variety of time windows including counts, averages, minimums, and maximums.

Figure 2.

Example of endpoint determination in cases of serial echocardiograms for the endpoints of severe aortic stenosis (top) and mortality (bottom). Each coloured arrow marks a serial echocardiogram performed on a single sample patient. Aortic stenosis progression model (top): Echo 1 has a 5-year prediction window ending between Echoes 5 and 6. It is marked as a control because severe aortic stenosis does not develop within that timeframe. Echo 2 has a 5-year prediction window ending between Echoes 6 and 7. Aortic stenosis progresses to a severe stage between Echoes 6 and 7, but whether this occurred within the 5-year prediction window is unknown; therefore, Echo 2 is censored. Echo 3 has a 5-year prediction window ending after Echo 7. It is marked as a case because the patient develops severe aortic stenosis within the prediction window. All subsequent echocardiograms are censored as they have moderate or severe aortic stenosis at the time of study. Mortality model (bottom): Echo 1 is censored since at least a 6-month survival can be assumed by the study design requirement for follow-up echocardiogram. Echo 2 is marked as a control because the patient survived the full 5-year prediction window. Echo 3 is marked as a case because the patient died within the 5-year prediction window. Echoes 4, 5, and 6 were censored because the patient had moderate aortic stenosis at the time of echocardiogram.

For each prediction point, a short-range (2-year) and long-range (5-year) prediction window was labelled. Those who reached a clinical endpoint within the prediction timeframe were labelled cases. Those who did not reach an endpoint within the prediction timeframe were labelled controls. When the endpoint within the prediction timeframe was indeterminate, the corresponding prediction point was censored.

The first model was trained to assess the likelihood of advancing from mild to severe AS. The study identified those who met the endpoint of severe AS and the first date at which an echocardiogram met this criterion. Severe AS was defined according to the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines as meeting at least one of the following criteria: peak velocity ≥ 4 m/s, mean gradient ≥ 40 mmHg, AVA (by velocity or time velocity integral) ≤ 1 cm2, or AVA indexed to body surface area ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2.9 The simplified Bernoulli equation was used for measurements of mean gradient. Electronic medical records of patients who underwent surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (AVR) were reviewed to determine the indication for replacement. Only those who had AVR for severe AS were considered to have met the endpoint for severe AS. Those who had AVR for other reasons were not considered to have met this endpoint. Follow-up concluded on the date of the procedure.

A second model was trained to assess for the endpoint of all-cause mortality. Because the inclusion criteria required patients to have at least two echocardiograms that were at least 6 months apart, survival during that interval period could be assumed and only echocardiograms performed more than 6 months after the initial echocardiogram were used for training. Patients who underwent AVR were censored at that time and were no longer followed after intervention.

Changes in statistical inputs and outcomes over the course of a sample period can bias ML models. For example, if there were fewer echocardiograms performed but a higher mortality rate for a particular year, this may result in a mortality model improperly associating mortality with the frequency of echocardiograms. To account for this, the training feature matrices were resampled to match outcome statistics for each calendar year.

With this matched data set, a features matrix was built with 5-year outcomes and the ML models were trained. An XGBoost model, an implementation of sequentially gradient-boosted decision trees, was chosen for its strengths in handling missing data and resistance to overfitting.10 This technique also allows for handling of missing data internally without additional data preprocessing. Specifically, during the training process, XGBoost learns to split missing data at each tree node and choose the split that minimizes loss of function. This allows for handling of missing data without imputation, reducing the risk of potential bias. A cross-validation technique was used to tune hyperparameters within this training data set. This yielded one model for AS progression and one model for mortality.

Analysis

The trained models were evaluated using the test group feature matrix, comprised of patient data from a separate clinical site. The AS progression and mortality models were trained using a 5-year outcome data matrix but were evaluated in their performance for both 2- and 5-year outcomes. Bootstrap sampling with replacement was performed, where a single patient was randomly selected, from which a single prediction point echocardiogram was chosen, before the patient was replaced and the process was repeated. This method allowed a single patient to be chosen more than once but prevented the overrepresentation of patients with numerous echocardiograms. With this selection, the performance measures and their 95% confidence margins were calculated. Performance was measured by area under the receiver-operating characteristics curve (AUC) and by sensitivity and positive predictive value. A predefined positive rate of 20% was chosen based on an estimate that the top fifth of the population would be at higher risk and would require more frequent clinical follow-up.

Additional subgroup analyses were performed. The model for progression to severe AS was also evaluated in its performance to predict progression to low-flow low-gradient severe AS. This endpoint was defined as AVA ≤ 1 cm² or indexed AVA ≤ 0.6 cm²/m² with a peak aortic velocity < 4 m/s, mean systolic gradient <40 mmHg, and stroke volume index < 35 mL/m2. Model performance was further evaluated between bicuspid and tricuspid AS as well as across age groups, sex, and LV ejection fraction (EF). Performance was also assessed by time of study. Given that our training matrix was designed for 5-year outcomes, the prediction point or baseline echocardiograms were primarily obtained between the 2010 and 2016 calendar years to allow for adequate follow-up time. We therefore compared performance between echocardiograms obtained before and after the 2013 calendar year, which bisected the baseline echocardiogram sample.

To assess the performance of the mortality model, we compared its performance to a validated AS risk stratification scoring system. Although there are limited data on risk stratification in patients with mild AS, the Généreux Staging Classification is a well-validated risk score designed to assess extravalvular cardiac damage among patients with severe AS.11 The performance of this risk score is provided for comparison.

For both the AS progression and mortality models, feature importance was calculated using a version of Shapley algorithm.12

With the intention to make prediction models easier to apply in real practice, we trained smaller models using only part of the input. The reduced-input model for AS progression used only inputs from the prediction point echocardiogram and did not require additional data from the EHR. The reduced-input model for mortality prediction used age, sex, and the leading or most influential features from echocardiographic, laboratory, and patient history data. In order to balance model complexity and performance, 13 features were selected by an iterative cross-validation greedy process, wherein, with each iteration, the feature that contributed the most to the prediction power was added to the model. The performance of these smaller models is also presented.

Results

Data

Included were 9611 patients [5825 (60.6%) men and 3786 (39.4%) women] who underwent 39 336 transthoracic echocardiograms. On average, 4.09 echoes were performed per patient. Baseline parameters obtained at the time of the initial echocardiogram showing mild AS are provided in Table 1. Laboratory data included over 12 million laboratory measurements for 9597 patients (99.9%). ICD9 and ICD10 diagnostic codes were received for all patients. The median number of total diagnosis codes per patient was 374 with many codes repeated over the course of multiple visits. Filtered to unique codes over the timeframe of the study, the median number was 115. Electrocardiographic variables included quantitative measurements (heart rate, p-wave duration, PR interval, QRS interval, and QTC interval) as well as coded statements regarding rhythm abnormalities (atrial fibrillation, bundle branch block, atrioventricular block, LV hypertrophy, ventricular ectopy, etc.). The number of echocardiograms per patient ranged from 2 to 47. The average first-to-last echocardiogram period for a patient was 48.5 months (range 6.0–152.4 months). Clinical, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic parameters considered in model development and their frequency of availability are given in Supplementary material online, Tables S2–S4.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics at the time of initial echocardiogram

| Parameters | |

|---|---|

| Clinical parameters | Mean (±SD) or n (%) |

| Age, years | 71.6 ± 10.9 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 3786 (39.4%) |

| Male | 5825 (60.6%) |

| Race | |

| White | 8963 (93.4%) |

| African American | 278 (2.9%) |

| Other or unknown | 370 (3.8%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 30.4 ± 6.1 |

| Heart rate, b.p.m. | 69.9 ± 13.0 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 132.1 ± 19.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 70.9 ± 10.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2954 (30.7%) |

| Hypertension | 5670 (59%) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 2934 (30.5%) |

| Smoking history | |

| Positive smoking history | 4300 (44.7%) |

| No smoking history | 2865 (29.8%) |

| Smoking history unknown | 2446 (25.5%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2561 (26.6%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 4091 (42.6%) |

| Prior percutaneous intervention | 859 (8.9%) |

| Prior stroke | 256 (2.7%) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 784 (8.2%) |

| Laboratory parameters | Count (%) | Mean (±SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin, g/dL | 8916 (92.8%) | 12.5 ± 2.0 |

| Erythrocytes, ×10(12)/L | 8866 (92.2%) | 4.1 ± 0.7 |

| Lymphocytes, ×10(9)/L | 7854 (81.7%) | 1.5 ± 0.7 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 4991 (51.9%) | 16.1 ± 6.1 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 6901 (71.8%) | 165.3 ± 39.4 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 6936 (72.2%) | 130.2 ± 67.8 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 5539 (57.6%) | 4.0 ± 0.5 |

| Haemoglobin A1c, % | 4243 (44.1%) | 6.3 ± 1.1 |

| N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide, pg/mL | 2004 (20.9%) | 1970.7 ± 3475.7 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 8788 (91.4%) | 1.4 ± 1.4 |

| Echocardiographic parameters | Count (%) | Mean (±SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 1029 (10.7%) | |

| Aortic valve area, cm² | 9207 (95.8%) | 2.0 ± 0.5 |

| Peak aortic valve velocity, m/s | 9609 (100%) | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| Aortic valve mean gradient, mmHg | 9226 (96%) | 11.8 ± 3.2 |

| Left ventricular end-systolic volume, mL | 4516 (47%) | 50.4 ± 28.9 |

| Left ventricular end-diastolic volume, mL | 4559 (47.4%) | 121.1 ± 44.1 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 9590 (99.8%) | 61.5 ± 9.2 |

| Left ventricular mass index, g/m2 | 9124 (94.9%) | 103.2 ± 26.3 |

| Relative wall thickness, % | 9145 (95.2%) | 0.44 ± 0.087 |

| Right ventricular systolic pressure, mmHg | 7933 (82.5%) | 37.0 ± 11.6 |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 8765 (91.2%) | 38.7 ± 12.3 |

| Medial E/eʹ | 9003 (93.7%) | 15.00 ± 6.32 |

| E/A ratio | 8114 (84.4%) | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

| Right ventricular sʹ, m/s | 5844 (60.8%) | 0.13 ± 0.031 |

| Stroke volume index, mL/m2 | 9399 (97.8%) | 49.1 ± 10.0 |

| Mitral regurgitation | ||

| None | 297 (3.1%) | |

| Mild | 7904 (82.6%) | |

| Moderate | 987 (10.3%) | |

| Severe | 127 (1.3%) | |

| Unknown | 296 (3.1%) | |

| Mid-ascending aorta diameter, mm | 6217 (64.7%) | 36.8 ± 4.7 |

In our AS progression training sample group, 438 (20.7%) individual patients (715 prediction point echocardiograms) were cases who reached the endpoint of severe AS within a 5-year prediction window and 1675 (79.3%) individual patients (3132 prediction point echocardiograms) were controls who did not reach this endpoint. The duration of follow-up for cases and controls for the endpoint of severe AS was 5.34 ± 2.4 and 8.21 ± 2.0 years, respectively. In our mortality prediction training group, 1267 (46.1%) patients (2458 prediction point echocardiograms) were cases who reached the endpoint of all-cause mortality within a 5-year prediction window and 1484 (53.9%) patients (3047 prediction point echocardiograms) were controls who did not reach this endpoint. The duration of follow-up for cases and controls for the endpoint of mortality was 1.56 ± 1.4 and 7.12 ± 1.8 years, respectively.

In the testing data set, the duration of follow-up in cases and controls for the endpoint of severe AS was 4.93 ± 2.6 and 8.02 ± 2.0 years, respectively. The duration of follow-up for cases and controls for the endpoint of mortality was 1.45 ± 1.3 and 6.85 ± 1.7 years, respectively. The numbers of cases and controls in the training and testing groups are shown in Figure 1.

Prediction performance for severe aortic stenosis

A full AS progression model was trained for predicting progression to severe AS based on all available features. The model was trained on the 5-year outcome training matrix and tested in its performance for both 2- and 5-year outcomes. In the testing group, this yielded an AUC of 0.86 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.81–0.92] and 0.86 (0.83–0.89), respectively. Because most predictive parameters were based on the echocardiogram, a similar process was used to design a reduced-input model which required only parameters obtained during the echocardiogram (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). The results showed a similar performance between these two models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Performance of full aortic stenosis progression model and reduced-input aortic stenosis progression model in predicting progression to severe aortic stenosis

| Model | AUC | NNeg | NPos | Sens | Spec | PPV | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 years | |||||||

| Full AS progression model | 0.859 (0.825–0.891) | 632 | 158 | 60.3 (54.1–67.5) | 90.1 (88.1–92.0) | 60.2 (51.3–68.9) | 14.2 (9.0–23.3) |

| Reduced-input AS progression model | 0.858 (0.825–0.888) | 632 | 158 | 59.6 (53.4–66.7) | 89.9 (87.9–92.1) | 59.8 (50.6–68.9) | 13.6 (8.6–21.5) |

| 2 years | |||||||

| Full AS progression model | 0.863 (0.805–0.920) | 1704 | 39 | 71.4 (57.5–86.8) | 81.2 (80.8–81.7) | 8.1 (5.4–11.2) | 12.2 (5.7–29.1) |

| Reduced-input AS progression model | 0.852 (0.791–0.904) | 1704 | 39 | 66.9 (50.0–80.8) | 81.1 (80.7–81.6) | 7.6 (4.9–10.9) | 9.4 (4.2–18.0) |

Values in parentheses are 95% CIs.

AUC, area under the receiver operation curve; NNeg, NPos, number of negative and positive test samples; Sens, Spec, PPV, OR, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and odds ratio, respectively, all calculated at the threshold of 20% positive rate.

The AS progression models maintained robust performance throughout various subgroup analyses. For patients with bicuspid AS, the full model achieved an AUC of 0.87 (0.78–0.96) and the reduced-input model yielded a similar AUC of 0.88 (0.79–0.96). When evaluated progression to low-flow low-gradient severe AS, the full model yielded an AUC of 0.88 (0.83–0.93) and the reduced-input model resulted in a similar AUC of 0.87 (0.81–0.93). Further subgroup analysis demonstrated a very modest decline in performance in women; however, the results remained robust with AUC > 0.8 throughout all subgroups in both the full and reduced-input models (Table 3).

Table 3.

Performance of severe aortic stenosis prediction models for 5-year outcomes within subgroups divided by age, ejection fraction, sex, and year of prediction

| Subgroup | AUC | NNeg | NPos | Sens | Spec | PPV | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full AS progression model | |||||||

| Age: ≤70 years | 0.856 (0.779–0.912) | 263 | 40 | 67.2 (54.3–79.5) | 87.3 (84.5–90.1) | 44.7 (31.3–58.9) | 15.5 (6.7–30.8) |

| Age: > 70 years | 0.848 (0.812–0.886) | 394 | 119 | 54.2 (47.5–62.4) | 90.4 (88.3–92.9) | 63.1 (54.3–73.7) | 11.6 (7.1–19.7) |

| Bicuspid | 0.869 (0.780–0.958) | 79 | 26 | 61.2 (45.8–79.1) | 93.4 (87.0–98.7) | 74.6 (47.2–95.3) | 34.6 (6.0–138.7) |

| Tricuspid | 0.859 (0.823–0.890) | 551 | 133 | 59.8 (52.9–66.7) | 89.6 (87.5–91.7) | 58.0 (48.2–67.2) | 13.2 (8.3–20.6) |

| EF: ≤ 50% | 0.840 (0.749–0.924) | 57 | 31 | 49.8 (38.9–62.5) | 96.4 (90.3–100.0) | 88.0 (66.2–100.0) | 30.0 (6.7–75.8) |

| EF: >50% | 0.858 (0.822–0.890) | 603 | 137 | 60.3 (52.8–67.3) | 89.1 (87.3–91.2) | 55.7 (47.2–64.9) | 12.9 (7.9–19.7) |

| Sex: female | 0.832 (0.789–0.877) | 361 | 94 | 55.1 (47.6–63.7) | 89.1 (86.6–91.6) | 56.8 (46.1–67.1) | 10.5 (6.1–18.2) |

| Sex: male | 0.899 (0.863–0.934) | 271 | 63 | 66.9 (56.6–78.0) | 91.0 (88.3–93.9) | 63.5 (50.7–76.1) | 22.2 (11.2–43.1) |

| Year ≤2013 | 0.854 (0.809–0.900) | 404 | 66 | 65.0 (54.4–76.1) | 87.4 (85.0–89.8) | 45.7 (34.0–57.3) | 13.8 (6.9–24.7) |

| Year >2013 | 0.866 (0.828–0.900) | 356 | 110 | 54.7 (47.6–62.4) | 90.8 (88.2–93.0) | 64.7 (53.5–74.3) | 12.5 (6.7–21.3) |

| Reduced-input AS progression model | |||||||

| Age: ≤70 years | 0.872 (0.812–0.921) | 263 | 40 | 67.5 (55.8–81.5) | 87.3 (84.8–90.0) | 45.1 (32.9–57.6) | 15.9 (7.5–33.1) |

| Age: >70 years | 0.841 (0.804–0.878) | 394 | 119 | 54.6 (47.5–62.1) | 90.5 (88.0–93.2) | 63.6 (52.5–74.7) | 12.0 (7.1–20.2) |

| Bicuspid | 0.875 (0.787–0.957) | 80 | 25 | 62.4 (48.1–80.0) | 93.5 (87.8–98.6) | 75.0 (51.9–95.3) | 37.8 (8.1–155.4) |

| Tricuspid | 0.851 (0.814–0.887) | 552 | 132 | 60.0 (53.5–67.5) | 89.6 (87.5–91.7) | 58.0 (48.9–67.2) | 13.4 (8.4–21.9) |

| EF: ≤50% | 0.863 (0.774–0.937) | 57 | 31 | 49.8 (39.5–64.3) | 96.1 (91.1–100.0) | 87.3 (71.8–100.0) | 31.1 (7.5–90.2) |

| EF: >50% | 0.856 (0.820–0.886) | 603 | 137 | 60.3 (53.1–67.7) | 89.1 (87.2–91.0) | 55.7 (46.7–63.6) | 12.9 (8.1–19.3) |

| Sex: female | 0.835 (0.787–0.876) | 361 | 94 | 57.3 (49.1–65.3) | 89.7 (87.3–92.2) | 59.2 (48.2–70.2) | 12.3 (7.0–20.1) |

| Sex: male | 0.892 (0.850–0.935) | 271 | 63 | 63.9 (54.4–74.0) | 90.3 (87.5–93.5) | 60.7 (47.8–74.6) | 18.0 (8.7–35.1) |

| Year ≤2013 | 0.861 (0.809–0.908) | 404 | 66 | 65.4 (55.4–76.1) | 87.4 (85.2–89.4) | 45.7 (35.0–56.3) | 13.9 (7.4–25.5) |

| Year >2013 | 0.855 (0.817–0.893) | 355 | 111 | 56.3 (49.1–64.8) | 91.3 (89.1–93.9) | 66.7 (57.8–77.5) | 14.2 (8.5–24.4) |

Values in parentheses are 95%CIs.

AUC, area under the receiver operation curve; NNeg, NPos, number of negative and positive test samples; Sens, Spec, PPV, OR, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and odds ratio, respectively, all calculated at the threshold of 20% positive rate.

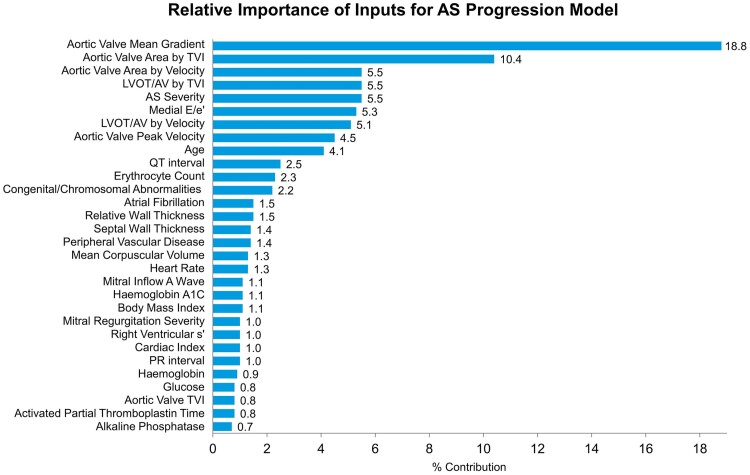

The relative importance of input signals for the severe AS progression model is shown in Figure 3. The leading feature was aortic valve mean pressure gradient. A univariate model using aortic valve mean gradient alone predicted progression to severe AS within a 5-year window with an AUC of 0.81 (0.77–0.84). The full model by comparison had an AUC of 0.86 (0.83–0.89) in this same set of patients. Other leading figures included AVA and dimensionless index.

Figure 3.

Relative feature importance in the full aortic stenosis progression model. In the model for progression to severe aortic stenosis, echocardiographic variables were of greatest importance.

Prediction performance for mortality

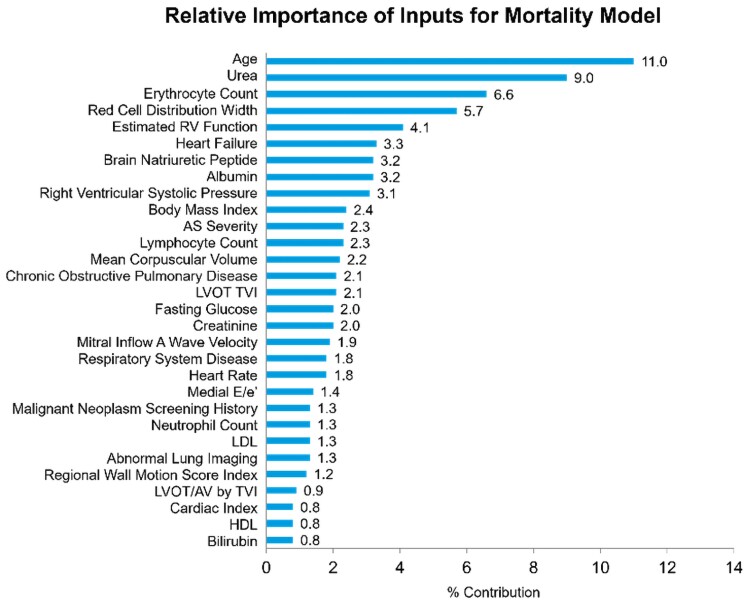

The mortality model was also assessed in its performance within both 2- and 5-year windows. In the test group, this yielded AUCs of 0.84 (0.82–0.86) and 0.87 (0.85–0.89), respectively. At the threshold of 20% positive rate, specificity was 98.8% and positive predictive rate 97.7%. The relative importance of input signals for the mortality model is shown in Figure 4. The leading feature was age, followed by laboratory values including urea and erythrocyte count.

Figure 4.

Relative feature importance in the full all-cause mortality model. Laboratory and clinical variables had greater importance in this model.

A practical reduced-input model was also trained, requiring only age, sex, and the 13 leading variables (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2), and demonstrated a similarly strong performance (Table 4). Both the full and reduced-input models performed with a considerably higher AUC than the Généreux Staging Classification. The performance of the mortality prediction models for 5-year outcomes within subgroups divided by age, EF, sex, and year of prediction is given in Supplementary material online, Table S5.

Table 4.

Performance of all-cause mortality predictors, compared with Généreux Staging Classification of cardiac damage

| Model | AUC | NNeg | NPos | Sens | Spec | PPV | OR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 years | |||||||

| Full mortality model | 0.872 (0.851–0.892) | 391 | 626 | 31.8 (30.3–33.3) | 98.8 (97.7–99.8) | 97.7 (95.3–99.5) | 49.4 (19.1–182.6) |

| Reduced-input mortality model | 0.871 (0.847–0.890) | 391 | 626 | 31.7 (30.2–33.4) | 98.7 (97.6–99.7) | 97.5 (95.1–99.5) | 45.5 (17.1–104.7) |

| Généreux Staging Classification | 0.676 (0.641–0.710) | 391 | 626 | 26.4 (24.7–28.0) | 90.2 (87.6–92.7) | 81.1 (75.9–86.2) | 3.4 (2.3–4.9) |

| 2 years | |||||||

| Full mortality model | 0.838 (0.816–0.858) | 1072 | 438 | 49.9 (46.3–53.5) | 92.2 (90.6–93.5) | 72.3 (66.5–77.2) | 12.0 (8.5–15.9) |

| Reduced-input mortality model | 0.830 (0.807–0.852) | 1072 | 438 | 48.6 (45.2–52.3) | 91.7 (90.3–93.3) | 70.5 (64.9–76.4) | 10.6 (7.8–14.5) |

| Généreux Staging Classification | 0.655 (0.627–0.685) | 1071 | 439 | 33.4 (30.0–36.7) | 85.5 (84.1–87.0) | 48.6 (43.3–54.5) | 3.0 (2.3–3.8) |

Values in parentheses are 95%CIs.

AUC, area under the receiver operation curve; NNeg, NPos, number of negative and positive test samples; Sens, Spec, PPV, OR, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and odds ratio, respectively, all calculated at the threshold of 20% positive rate.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the use of ML in mild AS to predict disease progression and all-cause mortality using data from echocardiograms, electrocardiograms, and demographic and laboratory variables. The AS progression model demonstrated robust findings with an AUC of 0.86 for progression to severe AS within 5 years and maintained a strong performance throughout subgroup analysis. The mortality model demonstrated similar strength with an AUC of 0.87 for mortality within 5 years. At the selected threshold of 20% positive rate, this resulted in a very high specificity of 98.8% and a positive predictive rate of 97.7%.

Additionally, the reduced-input models were designed for both the AS progression and mortality. These reduced-input models demonstrated a very modest decline in performance while simplifying the requirements for implementation in clinical practice. However, both models maintained a strong performance with AUC > 0.8 for both 2- and 5-year outcome predictions. This is in line with other current standard medical testing, such as the use of mammography for breast cancer screening (mean AUC 0.85) or the use of magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose multiple sclerosis (mean AUC 0.82).13 Models such as these could be implemented with institutional echocardiographic reporting software to integrate real-time data and provide follow-up recommendations when mild AS is detected.

Previous studies have explored the variables influencing AS progression and have implicated various clinical and echocardiographic factors5,14,15). In a recent study, Sánchez-Puente et al.16 reported on the use of ML models to predict AS progression, identifying baseline aortic valve peak and mean velocity to be the leading variables. Our work expands on existing literature and offers novel insights. Through the incorporation of clinical, laboratory, and electrocardiographic parameters in addition to echocardiographic measurements, we trained the largest and most comprehensive AS progression models. This allowed us to investigate the weight of input from a broad range of variables and optimize for combination of inputs which have not previously been investigated. Furthermore, we trained our models for patients presenting with mild AS, allowing us to investigate a less explored population with less significant variance in baseline AS severity. Even with this broad set of inputs, we found that echocardiographic variables including aortic valve mean gradient and AVA by time–velocity integral had the greatest relative importance in our models, highlighting the importance of a thorough echocardiographic assessment.

Additionally, we expanded on previous work by performing assessments on mortality outcomes. In contrast to the AS progression model that predominantly utilized echocardiographic inputs, the mortality model required multiple clinical and laboratory variables as well. The leading variables used to build the reduced-input mortality model were age and markers of renal function, anaemia, albumin, right ventricular function, and diastolic function. These variables likely yielded a good predictive value for mortality as they reflected overall health and the function of multiple organ systems. This finding is suggestive that the increased mortality seen in the mild AS population is likely not explained by risk of AS progression alone. This is consistent with previous literature which has associated even sclerotic aortic valve disease with increased risk of coronary events, stroke, and all-cause mortality.1 Furthermore, the leading variables in the mortality model may provide possible targets for clinical management. Addressing these variables and other modifiable risk factors may help in improving mortality within this population. While certain variables have been associated with a higher risk of mortality in severe AS,17 to our knowledge, this is the first mortality prediction model designed for mild AS.

Study limitations

Although the definition and parameters of AS have been clearly defined,9 certain haemodynamic states, such as high cardiac output, may result in increased peak aortic valve velocities and an overestimation of valvular disease. In order to correct for this, we used a physician interpretation statement to define severe AS (available in 57.9% of all prediction point echocardiograms for the AS progression model and 63.0% of all prediction point echocardiograms for the mortality model) and referred to the measured parameters when a physician interpretation statement was not available. Additionally, our inclusion criteria required documentation of abnormal valvular morphology to exclude patients with increased peak aortic valve velocities solely due to a high-flow state.

Our inclusion criteria required at least two echocardiograms obtained at least 6 months apart. Serial echocardiograms may have been obtained for reasons other than monitoring of AS. This introduces a potential selection bias towards those who developed more clinically relevant valvular or other cardiac disease. This requirement for at least a 6-month interval echocardiogram also introduces a survival bias, as any patients who did not survive until follow-up echocardiogram would have been excluded from this study. However, our aim was to identify patients with mild AS at high risk of disease progression and we would not clinically expect 6-month AS-related mortality with these early-stage patients. Therefore, while a survival bias inherently exists in the study design, it is unlikely to significantly affect the outcome of the AS progression model. When designing the mortality model, we accounted for this survival bias by excluding the initial echocardiograms where a 6-month survival could be assumed and only using subsequent echocardiograms as prediction points.

The AS progression model relied primarily on echocardiographic variables, emphasizing the importance of high-quality echocardiographic interrogation of aortic valve disease. However, this evaluation can have operator-dependent differences in image acquisition and interpretation which may introduce variability to the AS progression model output. We mitigated this limitation by showing robust results while testing on a geographically different site with different staff.

Additionally, the natural history of AS is highly variable with some patients experiencing rapid progression and others showing minimal change following initial diagnosis. This variability means that a 5-year prediction window may not fully capture the disease-associated mortality. We elected to assess 2- and 5-year prediction points to optimize the model in identifying high-risk individuals that would benefit from closer monitoring.

The development and implementation of artificial intelligence models for clinical practice come with significant considerations with regard to data security, model biases, and workflow integration. To maintain data privacy and security, our model was trained exclusively on de-identified information from patients who provided permission for access to their health records for research purposes. We collected data from a broad period of time and geographical area to mitigate potential biases. However, model performance may vary across institutions with different patient populations and imaging protocols. Our patient cohort was predominantly white which may limit generalizability. Future prospective validation studies to evaluate real-world performance are warranted.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the use of ML in cases of mild AS to identify those at risk of developing severe AS and increased mortality. Our models were robust in identifying high-risk patients with mild AS who may benefit from closer follow-up. Further, we found that AS prediction models could be based on information obtained at the time of echocardiogram alone with strong performance similar to the full model. Such models can be used to provide individualized follow-up recommendations and patient-specific care to improve outcome. Future prospective validation study is required to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Raghav R Julakanti, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Ratnasari Padang, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Christopher G Scott, Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Jordi Dahl, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Nader J Al-Shakarchi, Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA.

Coby Metzger, Medial EarlySign, Hod Hasharon, Israel.

Alon Lanyado, Medial EarlySign, Hod Hasharon, Israel.

John I Jackson, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Vuyisile T Nkomo, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Patricia A Pellikka, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Digital Health.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Mayo Clinic. P.A.P. is supported as the Betty Knight Scripps Professor of Cardiovascular Disease Clinical Research, Mayo Clinic.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request with the corresponding author with restrictions that maintain patient confidentiality.

References

- 1. Di Minno MND, Di Minno A, Ambrosino P, Songia P, Pepi M, Tremoli E, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in patients with aortic valve sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2018;260:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG. Clinical profile and natural history of 453 nonsurgically managed patients with severe aortic stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:2111–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurmann R, Buffle E, Pasch A, Seiler C, de Marchi SF. Predicting progression of aortic stenosis by measuring serum calcification propensity. Clin Cardiol 2022;45:1297–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Otto CM, Prendergast B. Aortic-valve stenosis—from patients at risk to severe valve obstruction. N Engl J Med 2014;371:744–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tafciu E, Mandoli GE, Santoro C, Setti M, d’Andrea A, Esposito R, et al. The progression rate of aortic stenosis: key to tailoring the management and potential target for treatment. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2021;22:806–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pappada SM. Machine learning in medicine: it has arrived, let’s embrace it. J Card Surg 2021;36:4121–4124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guo Y, Xia C, Zhong Y, Wei Y, Zhu H, Ma J, et al. Machine learning-enhanced echocardiography for screening coronary artery disease. Biomed Eng Online 2023;22:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Arnaout R. Can machine learning help simplify the measurement of diastolic function in echocardiography? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14:2105–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP III, Gentile F, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021;143:e72–e227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chen T, Guestrin C. XGBoost: a scalable tree boosting system. In: Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. San Francisco, CA, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2016. p785–794. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Genereux P, Pibarot P, Redfors B, Mack MJ, Makkar RR, Jaber WA, et al. Staging classification of aortic stenosis based on the extent of cardiac damage. Eur Heart J 2017;38:3351–3358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lundberg SM, Lee S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In: Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems. Long Beach, CA, USA: Curran Associates Inc.; 2017. p4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhou X-H, McClish DK, Obuchowski NA. In: Hoboken NJ, ed. Statistical Methods in Diagnostic Medicine. 2nd ed. Wiley; 2011. p545. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eveborn GW, Schirmer H, Lunde P, Heggelund G, Hansen JB, Rasmussen K. Assessment of risk factors for developing incident aortic stenosis: the Tromsø Study. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Prosperi-Porta G, Willner N, Unni RR, Lau L, Santo PD, Chan K, et al. Aortic stenosis baseline severity predicts progression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sánchez-Puente A, Dorado-Diaz PI, Sampedro-Gomez J, Bermejo J, Martinez-Legazpi P, Fernandez-Aviles F, et al. Machine learning to optimize the echocardiographic follow-up of aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2023;16:733–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pellikka PA, Sarano ME, Nishimura RA, Malouf JF, Bailey KR, Scott CG, et al. Outcome of 622 adults with asymptomatic, hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis during prolonged follow-up. Circulation 2005;111:3290–3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request with the corresponding author with restrictions that maintain patient confidentiality.