Abstract

Aims

Accurate heart function estimation is vital for detecting and monitoring cardiovascular diseases. While two-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) is widely accessible and used, it requires specialized training, is prone to inter-observer variability, and lacks comprehensive three-dimensional (3D) information. We introduce CardiacField, a computational echocardiography system using a 2DE probe for precise, automated left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) ejection fraction (EF) estimations, which is especially easy to use for non-cardiovascular healthcare practitioners. We assess the system’s usability among novice users and evaluate its performance against expert interpretations and advanced deep learning (DL) tools.

Methods and results

We developed an implicit neural representation network to reconstruct a 3D cardiac volume from sequential multi-view 2DE images, followed by automatic segmentation of LV and RV areas to calculate volume sizes and EF values. Our study involved 127 patients to assess EF estimation accuracy against expert readings and two-dimensional (2D) video-based DL models. A subset of 56 patients was utilized to evaluate image quality and 3D accuracy and another 50 to test usability by novice users and across various ultrasound machines. CardiacField generated a 3D heart from 2D echocardiograms with <2 min processing time. The LVEF predicted by our method had a mean absolute error (MAE) of , while the RVEF had an MAE of .

Conclusion

Employing a straightforward apical ring scan with a cost-effective 2DE probe, our method achieves a level of EF accuracy for assessing LV and RV function that is comparable to that of three-dimensional echocardiography probes.

Keywords: Echocardiography, Implicit neural representation, Left and right ventricular volumes and ejection fractions, Three-dimensional heart

Graphical Abstract

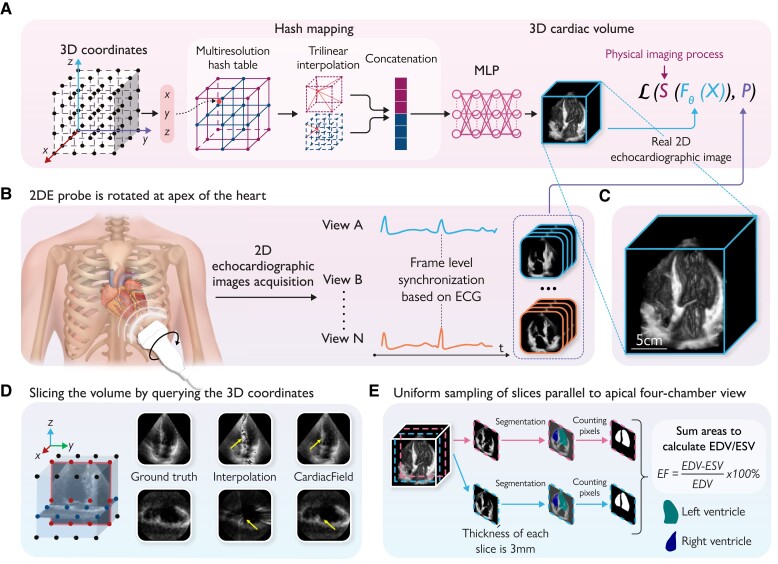

Graphical Abstract.

The workflow of the CardiacField and ejection fraction (EF) calculation: (A) the whole three-dimensional (3D) heart is represented as an implicit function, where the input is a 3D co-ordinate of the heart and the output is the corresponding intensity . This continuous 3D function is approximated by a multilayer perceptron (MLP) network with a multiresolution hash table , where θ refers to the parameters of the MLP and the hash table. The implicit function is determined by minimizing a physically informed loss function . (B) Two-dimensional echocardiographic (2DE) images are acquired by rotating the 2DE probe in 360° around the apex of the heart. Then, we synchronize multiple cardiac views and select images at end-diastole and end-systole based on a concurrently recorded electrocardiogram. (C) The 3D rendering of the reconstructed heart by CardiacField. (D) CardiacField represents a 3D heart in a continuous implicit function, leading to less artefacts in slices compared with the conventional interpolation,16 as indicated by the yellow arrows. (E) The workflow of the EF calculation based on CardiacField. We first perform the uniform sampling on the reconstructed 3D heart to generate ∼20–30, 3 thick two-dimensional slices parallel to the apical four-chamber view and then use the segmentation model developed in EchoNet11 to classify the left ventricular (LV) and right ventricular (RV) regions. We calculate the volumes of the LV and RV by summing the area of each slice. The EF is defined as the ratio of changes in the end-systolic volume and end-diastolic volume of the LV/RV. MLP, multilayer perceptron; ECG, electrocardiogram; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; ESV, end-systolic volume; EDV, end-diastolic volume.

Introduction

Heart function evaluation is essential for maintaining cardiovascular health, preventing diseases, and managing existing conditions effectively. It enables healthcare providers to make informed decisions about patient care and empowers individuals to take proactive steps towards better heart health.1,2 Left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF), measuring the ratio of change in the left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes (EDVs), is one of the most important metrics of heart function and plays a central role in the management of patients with heart disease, guiding diagnosis, treatment, and prognostication.3,4 Meanwhile, right ventricular (RV) EF (RVEF) reflects the right heart pumping function and is gaining increasing recognition in cardiovascular care with the acknowledgement of the prognostic significance of RV dysfunction.5

Two-dimensional echocardiography (2DE) is still the method of choice for routine cardiovascular imaging and function evaluation, due to its low costs, accessibility, and high spatial and temporal resolution.6,7 However, conventional 2DE can hardly obtain RVEF and relies on professional image acquisition procedures and years of expertise experience to predict a reliable LVEF, despite which the results are often variable between observers.2,8 The emergence of three-dimensional echocardiography (3DE) makes both LVEF and RVEF estimation more reproducible, as it accurately quantifies the cardiac volume without geometric assumptions, which has been validated against cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.2 But currently, 3DE is still not widely available, more time-consuming, and highly dependent on human expertise, and 3DE probes face technological challenges of limited spatial and temporal resolution, poor signal-to-noise ratio, and complex noise characteristics.9,10

It is of great interest to take advantage of readily available 2DE probes to predict heart function automatically and accurately. With the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology, deep learning (DL)-based tools have been developed to analyse and interpret echocardiograms. EchoNet11 achieves automatic LVEF estimation from 2DE videos with a reduction in variability compared with assessments made by human experts.12 RVENet13 achieves RVEF quantification from a single 2DE apical four-chamber image, which is an end-to-end network that is trained using RVEF values calculated from 3DE as a supervison. Although these reported results are exciting and encouraging, their performance is somewhat limited by the nature of data-driven approaches, such as concerns of scalability and generalization.

Therefore, in this study, we aim to use 2DE probes to reconstruct a three-dimensional (3D) cardiac volume optimized by a physically informed loss function in a self-supervised manner. The system (CardiaField) is designed to deal with unlabelled apical view–based images to simplify the echocardiogram acquisition procedures for non-cardiovascular healthcare practitioners, and it automatically predicts both LVEF and RVEF comparable to that of 3DE probes.

Methods

Overview of CardiacField

Principle

The core of CardiacField is an implicit neural representation (INR) network14 optimized by the physically informed loss function, which maps the input 3D co-ordinate of a cardiac volume to its corresponding intensity value. Through self-supervised training with a sequence of 2DE images easily collected by a commodity 2DE probe in clinics, a continuous and smooth 3D cardiac volume can be reconstructed by querying the trained network model with the corresponding co-ordinate of the denser grid (Graphical Abstract, A). Details of the system are summarized in Supplementary material online, Methods.

Image acquisition protocol

CardiacField eliminates the need for standard echo laboratory acquisition procedures. The operator only needs to identify the apical position on the chest and perform a simple apical ring scan (see Graphical Abstract, B). Images are collected by acquiring a full cardiac cycle at each position before moving to the next. The sonographer clicks ‘Acquire’ at each new position, and the ultrasound machine automatically captures images for a full cycle. To ensure sufficient two-dimensional (2D) images for qualified reconstruction, we recommend conducting a slow scan over 5–10 min per patient, during which the sonographer gradually rotates the probe to capture as many images as possible. This approach typically results in the acquisition of ∼200 images. After the scan is completed, the system automatically identifies and selects 120 high-quality images for reconstruction (details of the image selection algorithm are provided in Section 1.3 of the Supplementary material online, Methods).

Features of a CardiacField-reconstructed three-dimensional heart

(i) Self-supervised training (Graphical Abstract, A): Unlike traditional data-driven AI algorithms that require large-scale data sets for training, our method leverages self-supervised learning, allowing individual patient reconstruction using multi-view 2DE images from a simple apical ring scan. This approach minimizes the risks associated with data bias prevalent in conventional AI methods,15 ensuring robust and high-fidelity 3D heart reconstruction. (ii) Continuous slicing capability (Graphical Abstract, 1D): Due to the INR nature of CardiacField, the reconstructed cardiac volume is ‘continuous’ rather than ‘interrupted’ as conventional interpolation methods16 present. Therefore, we can slice the volume at pixel-level thickness from any angel and generate ‘New Views’.

Two-dimensional and three-dimensional databases

Two-dimensional data

Two-dimensional echocardiographic images were acquired using commercial PHILIPS EPIQ 7C/IE ELITE machines equipped with S5-1 2DE probes and SIEMENS ACUSON SC2000 PRIME machines equipped with 4V1c 2DE probes, where operators rotated the 2DE probe in 360° around the apex of the heart for each independent patient. The detailed process is described in the following. The procedure begins with the probe positioned at the apical four-chamber view, providing a clear visualization of the heart’s chambers. The probe is then gradually rotated 360° around the apex of the heart, transitioning through various views: from the apical four-chamber view to the three-chamber and two-chamber views and then back to the four-chamber view. During this rotation, real-time image feedback is used to make necessary adjustments, ensuring effective capture of all views. The probe is not held in a fixed position; instead, continuous adjustments are made to align the probe correctly and obtain high-quality images from different angles around the LV apex. Throughout the rotation, a series of 2D images are captured at various angles to cover a complete 360° sweep around the apex. Then, the sequence of 2DE images is synchronized based on concurrently recorded electrocardiogram signals. We cropped and masked 2DE images to remove text, electrocardiogram information, and other irrelevant information outside the scanning sector and then resized them to 160 × 160-pixel images using a bicubic interpolation filter. These images are later used for the CardiacField derivation and further calculation of LV/RV volumes and EFs.

Three-dimensional data

Three-dimensional echocardiographic images were obtained for each patient by experienced echocardiographers using a PHILIPS EPIQ 7C system equipped with X5-1 3DE probes for comparison. Left ventricular volumes and EFs were evaluated using LV-focused 3D echocardiography (HeartModel, PHILIPS).17 Similarly, RV volumes and EFs were assessed using RV-focused 3D echocardiography (4D RV-Function, TomTec Imaging).18 The calculated volumes and EFs served as the ground truth in our experiments.

Our entire experimental design and execution were conducted under the guidance and participation of experienced echocardiographers. Our collaborating centre, the Department of Echocardiography of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, is a large centre performing over 200 000 routine transthoracic echocardiograms, bedside echocardiograms, and intra-operative transoesophageal echocardiography procedures annually. The paired 2DE/3DE images used in this research were collected from 127 patients, and these data were approved by the Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University.

Evaluation of system performance

Analysis of three-dimensional reconstruction accuracy

To assess the effectiveness of CardiacField’s 3D heart reconstruction, we conducted an experiment using simulated 2DE images sliced from a 3D volume (captured by a 3DE probe). The core of accurate 3D reconstruction from 2D images hinges on the positional parameter , which denotes the location of each 2D slice within the 3D heart (detailed in Sections 1.2 and 1.3 of Supplementary material online, Methods). In this experiment, we utilized 90 2DE images, sliced from each real-captured 3D cardiac volume with a known ground truth . These images were input into CardiacField for 3D reconstruction. The estimated positional parameters generated by CardiacField were then compared with the ground truth to evaluate the system’s reconstruction accuracy.

Assessment of image quality

To assess image quality, we compared the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), an established metric for image assessment, among images reconstructed by CardiacField and PlaneInVol19 (a conventional interpolation method) and those directly captured with a 3D probe. Notably, PlaneInVol utilizes the same 2DE images and positional parameters as CardiacField for reconstructing the 3D cardiac volume.

Ejection fraction estimation

Utilizing the high-fidelity 3D heart reconstructed by CardiacField, we employed a classical segmentation method11 to automatically classify the LV and RV volumes (details are given in Section 2 of Supplementary material online, Methods) and calculate the volumes and EFs of 127 patients. Additionally, we used the same patient cohort for making comparisons with state-of-the-art tools EchoNet11 and RVENet,13 which are based on 2DE videos.

Generalization to novice users

To confirm the applicability of CardiacField for non-cardiovascular healthcare practitioners, we evaluated the system’s capability to automatically screen useful 2D images and identified the limitations necessary for successful 3D reconstruction.

Generalization to different ultrasound machines

To assess the reliability of CardiacField across various ultrasound systems, we recruited five volunteers for generalization experiments using two widely used 2D ultrasound machines, namely PHILIPS and SIEMENS. Additionally, we evaluated the performance of our method with two portable handheld 2DE probes from PHILIPS Lumify and SonoEye V3.

Results

Analysis of three-dimensional heart reconstruction accuracy

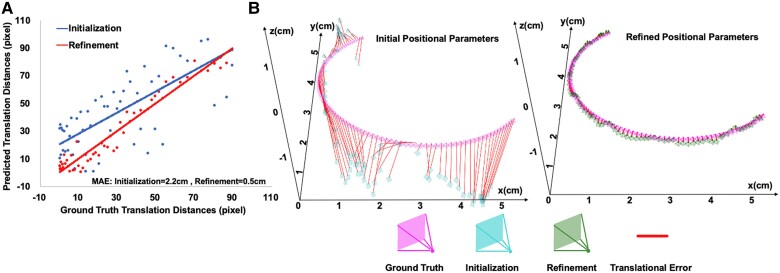

To estimate positional parameter , we initially used PlaneInVol19 for preliminary estimates and then inputted 90 views into CardiacField for joint 3D heart reconstruction and positional parameter optimization. Parameter , comprising a rotation matrix and a translation vector, was analysed for accuracy by comparing rotation angles and translation distances with the ground truth (detailed in Section 1.3 Supplementary material online, Methods). Figure 1A displays both initial and optimized parameters, with the red and blue lines indicating the regression between estimated and true values, respectively. CardiacField achieved accurate recovery of positional parameter with only averaged error in rotation angles and cm error in translation distances over 56 hearts, leading to and error reduction, respectively, over initial positional parameters. Additionally, we visualized the initialized, refined, and ground-truth positional parameter trajectories of one heart in Figure 1B.

Figure 1.

An analysis of three-dimensional heart reconstruction accuracy. (A) A visualization of initialized and refined positional parameters, where the red and blue lines illustrate the least squares regression lines between the estimated positional parameters and the ground truth. (B) A visualization of the positional parameter trajectories. The initial and refined positional parameters were obtained using PlaneInVol and CardiacField, respectively.

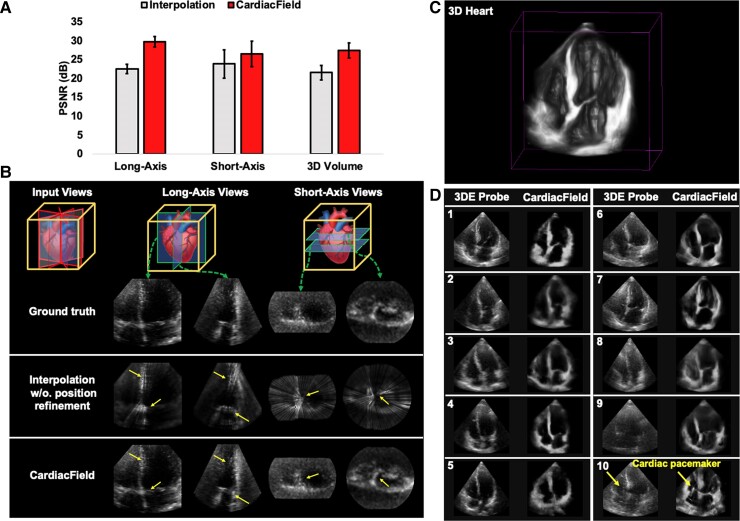

Assessment of image quality

Using CardiacField, we reconstructed a 3D heart from 90 simulated 2DE images derived from a real 3D heart and compared this with a conventionally interpolated 3D model, which averages intensities from the nearest 20 pixels. CardiacField achieved a PSNR of , significantly higher than that of from the interpolation method, demonstrating a closer approximation to the real 3D heart captured by a 3DE probe (Figure 2A). Additionally, we tested the ‘continuous-slicing’ ability of CardiacField by generating 160 new views along the long and short axes of the heart, compared with the same views reconstructed by interpolation. The interpolated method produced PSNRs of (long axis) and (short axis), whereas CardiacField recorded those of and , respectively, confirming superior quality and reduced interpolation artefacts (Figure 2B, highlighted by yellow arrows).

Figure 2.

An assessment of image quality. (A) We evaluated the image quality of three-dimensional hearts reconstructed by CardiacField and a conventional interpolation method, comparing them against real-captured three-dimensional hearts. For quality assessment, we used peak signal-to-noise ratio scores, where higher values indicate better image quality, across newly generated long-axis views, short-axis views, and the overall three-dimensional volume. (B) We demonstrated the ‘continuous-slicing’ capability of CardiacField in contrast to the conventional interpolation method. By extracting and comparing the same views from different methods, we showed that CardiacField can produce arbitrary views while avoiding the interpolation artefacts, which are marked with yellow arrows. (C) We used CardiacField to reconstruct realistic three-dimensional heart with real-captured two-dimensional echocardiographic images. (D) We compared apical four-chamber cross-sectional views of hearts reconstructed by CardiacField with those captured by a three-dimensional probe across 10 patients. The results highlighted that CardiacField’s reconstructions were more detailed and exhibited fewer artefacts compared with those by the three-dimensional probe.

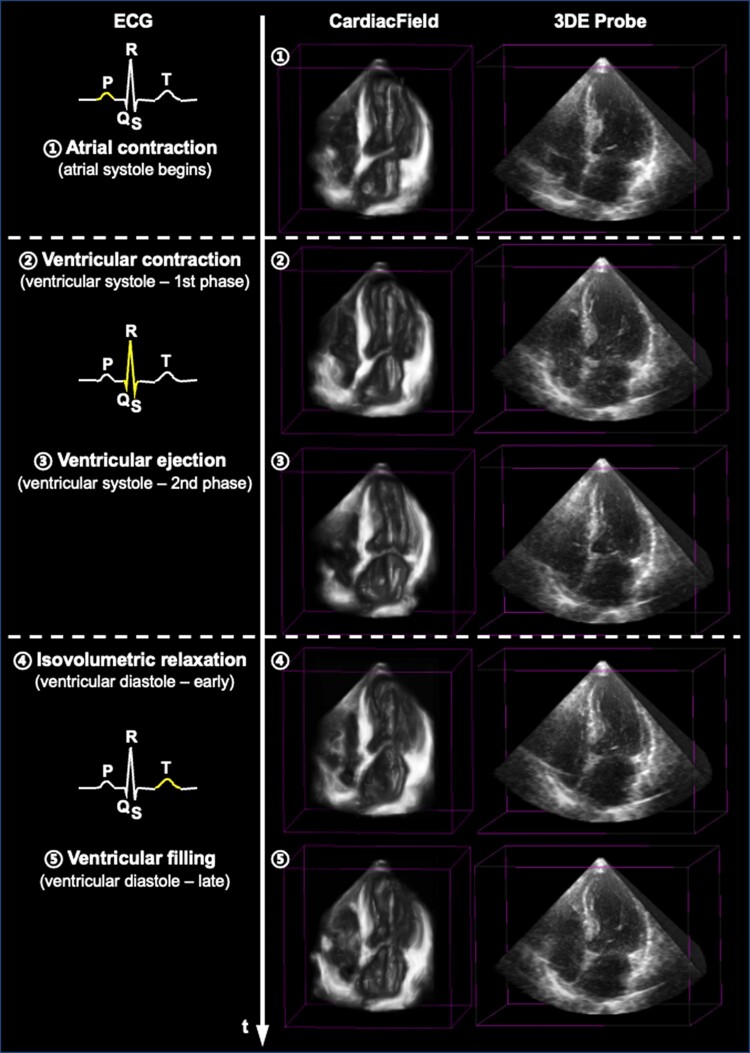

Using real-captured 2DE images, CardiacField effectively reconstructs realistic 3D cardiac structures, showcasing superior spatial details compared with those rendered by a 3DE probe (Figure 2C and D). We examined cross-sectional apical four-chamber views from 10 patients, where CardiacField demonstrated enhanced resolution and contrast (Figure 2D1–D5). Notably, it clearly resolved structures such as the left atrium, which appeared noisy in 3DE images (Figure 2D6), and better imaged the RV and atrial areas (Figure 2D7–D9). In one case, CardiacField distinctly visualized an implanted cardiac pacemaker, undetectable by the 3DE probe (Figure 2D10). Supplementary material online figures show varied reconstruction results across different demographics and challenging cases, such as patients with narrow intercostal spaces (Supplementary material online, Figures S2 and S3). Furthermore, CardiacField reconstructed dynamic 3D hearts across a cardiac cycle, detailed in Supplementary material online, Video S1 and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A three-dimensional dynamic heart within one cardiac cycle. We show some snapshots of a reconstructed three-dimensional dynamic heart within one cardiac cycle using CardiacField, compared with that acquired by the three-dimensional echocardiography probe. The electrocardiogram is used to indicate the phases within one cardiac cycle.

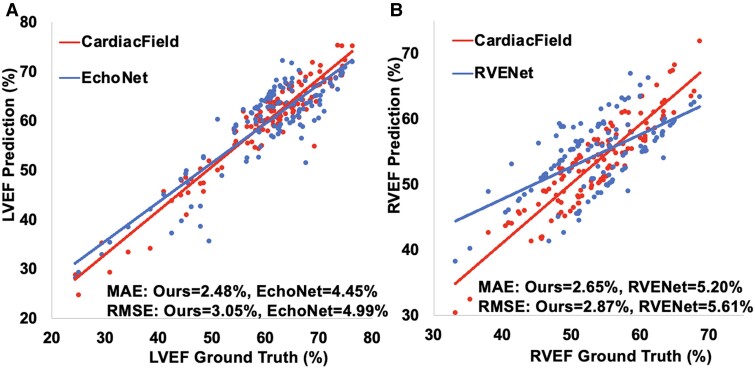

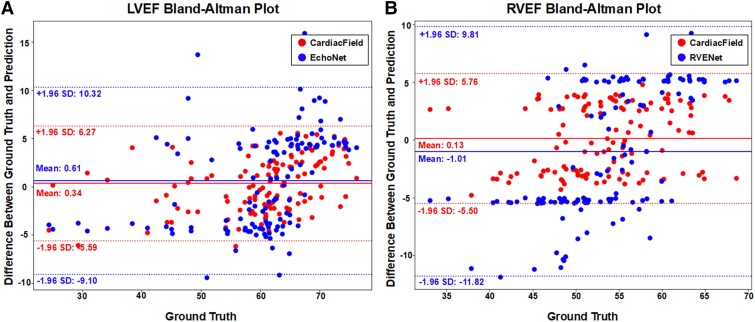

Ejection fraction estimation

Utilizing the high-fidelity 3D heart reconstructed by CardiacField, we applied a classical segmentation method11 to delineate LV/RV volumes and calculate EFs for 127 patients, as detailed in Section 2 of the Supplementary material online, Methods. We calibrated the volumes and EFs against ground truths established by three experienced echocardiographers, in line with guidelines from major echocardiography associations. The mean absolute errors (MAEs) for LV EDV and LV end-systolic volume (ESV) were and , respectively. For RV EDV and ESV, the MAE values were and , respectively. It is worth noting that the mean RV EDV and RV ESV estimated by our method were and , respectively, less than the ground truth values. This discrepancy may be attributed to our LV-focused image acquisition potentially missing parts of the RV outflow tract (RVOT), leading to an underestimation of the RV volume. The exclusion of the RVOT only slightly influenced the RVEF calculation because EF measured the ratio of changes in the EDV and ESV. As the RVOT represents a small portion of the total RV area and does not contract, its absence has a minimal effect on RVEF. The experimental results support this conclusion. In EF comparisons with EchoNet11 and RVENet13—DL models based on 2D videos—our method demonstrated superior stability and accuracy, achieving an LVEF MAE of and a root mean squared error (RMSE) of and an RVEF MAE of and an RMSE of . This demonstrated a superior performance when compared with EchoNet with an LVEF MAE of and an RMSE of . Similarly, it outperformed RVENet, which showed an RVEF MAE of and an RMSE of , as illustrated in Figure 4. The Bland–Altman plots in Figure 5 demonstrate the agreement between CardiacField and the ground truth. These plots reveal that the limits of agreement of LVEF and RVEF estimated by CardiacField are narrower than those of EchoNet and RVENet, suggesting superior accuracy of our algorithm.

Figure 4.

An estimation of ejection fraction. (A) We compared our left ventricular ejection fraction results with those of EchoNet,11 where the ejection fractions obtained by the three-dimensional ultrasound machine (after calibration by the experienced echocardiographers) were set as the ground truth. The two lines represent the least squares regression line between model prediction and ground truth, respectively. (B) We also compared our right ventricular ejection fraction results with those of RVENet.13 LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RVEF, right ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 5.

Bland–Altman plots of ejection fraction estimation. The Bland–Altman plots comparing our left ventricular ejection fraction and right ventricular ejection fraction results with those of EchoNet11 and RVENet,13 respectively. The plots show the mean difference (bias) and the limits of agreement (mean difference ± 1.96 SD) between the model predictions and the ground truth.

The detailed process and reconstructed 3D volumes of both the LV and the RV are demonstrated in Section 2 of Supplementary material online, Methods and Graphical Abstract, E, as well as in Supplementary material online, Videos S1 and S2. Additional point cloud results of the segmented RV volume are shown in Supplementary material online, Video S4.

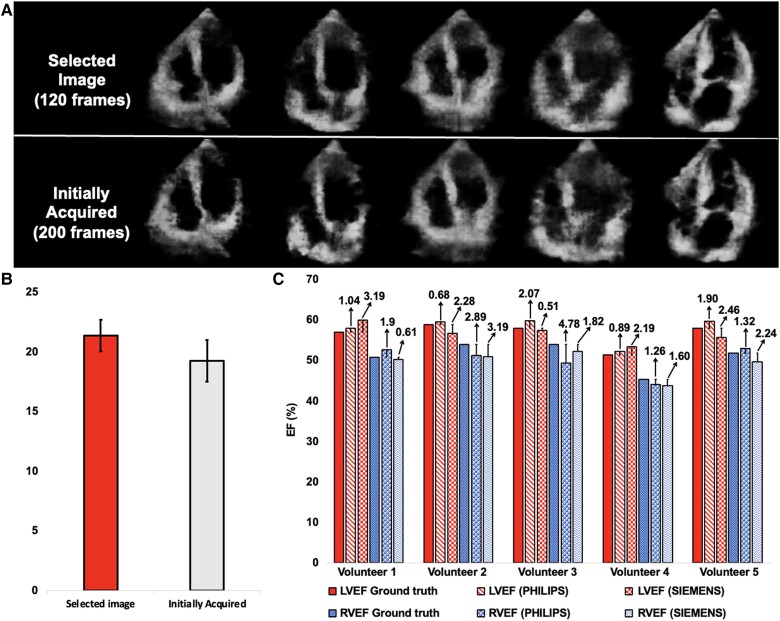

Generalization to novice users

CardiacField streamlines echocardiography by automating the image selection process for 3D reconstruction, making it suitable for operators without specialized training. We trained a neural network to predict the positions of each 2D image within a 3D heart (detailed in Section 1.3 of the Supplementary material online, Methods). During the initial scan, we collected a sufficient number of 2D images for 3D reconstruction. The trained network was used to predict the positions of these images. We predefined criteria establishing 120 standard positions, spaced at 3° intervals to complete a 360° circle. We calculated the distance between the predicted position of each image and its corresponding predefined position. The 120 images closest to their respective predefined positions were selected for the reconstruction process. This process inherently filtered out low-quality images. The low-quality images, which lack meaningful structural information, resulted in inaccurate position predictions. Consequently, these images were not close to the predefined standard positions and were automatically excluded from the reconstruction process. To evaluate usability across different expertise levels, we conducted a study with 50 participants divided into the following four groups: medical students with limited imaging experience, general practitioners occasionally using basic ultrasound, nurses and technicians familiar with imaging but not echocardiography, and non-medical volunteers. We provided clear and comprehensive pilot demonstrations to ensure that all participants understood the process, including identifying the apical region and starting with the apical four-chamber view. Practical tips on maintaining steady hand movements and making necessary adjustments based on real-time image feedback were also part of the training. Additionally, regular quality checks during the scan helped ensure that the images captured were of sufficient quality for reconstruction, thus mitigating potential issues related to prolonged scanning. Our findings, detailed in Figure 6A and B, showed that CardiacField maintained high image quality across all user groups, with selected images achieving a higher PSNR () compared with the full data set (). This confirms the system’s ability to produce quality 3D reconstructions with fewer artefacts and clearer structural details, regardless of the operator’s background.

Figure 6.

Generalization to novice users. (A) We conducted an experiment with 50 participants divided into four groups based on their background. Each performed a simple apical ring scan using CardiacField, capturing ∼200 images. Our algorithm then selected the top 120 images for high-quality three-dimensional reconstruction, resulting in images with fewer artefacts and clearer structural details compared with reconstructions from the full, unselected data sets. (B) The system achieved a higher peak signal-to-noise ratio in selected images compared with the full data set, showcasing the algorithm’s efficiency in image selection across diverse backgrounds. (C) Additionally, we reconstructed three-dimensional hearts and calculated ejection fractions for five volunteers using two different two-dimensional ultrasound machines commonly found in clinics. The consistent results across different machines highlighted the robust generalization capabilities of our method. PSNR, peak signal-to-noise ratio.

Generalization to different ultrasound machines

To assess the robustness of CardiacField across different ultrasound machines, we conducted experiments with five volunteers using two distinct 2D ultrasound machines, namely PHILIPS and SIEMENS, with PHILIPS serving as the primary machine and SIEMENS for validation. The experiments involved reconstructing 3D hearts from 2D images captured by both machines and calculating LVEF and RVEF for the same individuals. As shown in Figure 6C, the results of the LVEF predictions indicated an MAE of and an RMSE of on PHILIPS and an MAE of and an RMSE of on SIEMENS, whereas the results of the RVEF predictions showed an MAE of and an RMSE of on PHILIPS and an MAE of and anRMSE of on SIEMENS, all within clinically acceptable error margins of .4,20 Further tests with handheld 2DE probes from PHILIPS Lumify and SonoEye V3 confirmed the system’s capability to reconstruct the high-fidelity 3D heart, as detailed in Supplementary material online, Figure S4.

Discussion

In this report, the proposed artificial neural network CardiacField utilizes 2DE probes to provide accurate and automated assessments of cardiac function, eliminating the need for specialized professional training. The system generates a 3D heart from 2D echocardiograms within 2 min processing time and automatically segments and quantifies the volume of the left ventricle and right ventricle without manual calibration. CardiacField estimates LVEF and RVEF with and higher accuracy rates than state-of-the-art video-based methods.11,13 This technology will enable non-cardiologist healthcare practitioners to conduct routine heart function screenings.

Predicting accurate LVEF and RVEF using 2DE can indeed be challenging. It requires technical expertise in image acquisition, optimization, and interpretation. Moreover, the ventricular walls are not perfectly planar structures but exhibit complex 3D geometry.8 Traditional 2DE provides only a limited perspective of this 3D geometry, leading to inaccuracies in measurements and assessments that rely on geometric assumptions, such as ventricular volumes and EF.2,3,8 Deep learning tools have made praiseworthy achievements in the interpretation of 2DE by automating tasks such as image segmentation, feature extraction, and diagnostic classification. But their performance is somewhat limited by the ambiguities of characterizing a 3D heart using 2D images or videos.11,13,21 In contrast, CardiacField represents a novel method of automatic EF estimation that combines the accuracy of 3D volumes and efficiency of AI-enabled automatic processing. In addition, CardiacField avoids routinely underused 3DE probes but uses conventional 2DE probes, coupled with a relatively straightforward image acquisition procedure, enhancing its feasibility for widespread use among general healthcare providers.

Our approach diverges from traditional methods that depend on extensive data sets from diverse individuals for training. Instead, we adopt a physically informed learning strategy22 by embedding the physical imaging process into the loss function of the neural network. The physical imaging process of a 2DE image can be modelled as the process of virtually slicing a 2D plane from the 3D volume (i.e. 2D slicing). Traditional AI methods rely on large data sets, which often introduce data bias, especially when there is a domain gap (e.g. data distribution) between the training and the testing sets, leading to performance degradation on the test set and necessitating external validation. However, our approach, as a non-data-driven AI algorithm supervised by physical laws, mitigates risks associated with data bias inherent in traditional data-driven AI methods. Therefore, all data inherently serve as external validation sources, eliminating the need for conventional external validation.

Generalization remains a challenge in AI-driven healthcare. RVENet, a DL tool trained on the largest data set of its kind (764 examinations across 665 patients with 2932 videos), demonstrated RVEF prediction with an MAE of for internal validation and for external validation. In our data set, RVENet achieved a comparable MAE of . The performance drop in the external data sets was attributed to differences in demographics and clinical characteristics between the internal and the external groups. Contrastingly, our self-supervised approach with CardiacField minimized such generalization concerns. It did not depend on extensive data sets for training. Instead, CardiacField used each patient’s own 2DE images to train the system and generate personalized 3D cardiac volumes and EFs, achieving stable LVEF and RVEF estimations with MAEs of and , respectively.

Our method is, to the best of our knowledge, the first INR23 model for continuous 3D heart reconstruction. Unlike traditional explicit geometric representations such as meshes or point clouds, INR offers advantages such as continuous representation and topology independence. Utilizing a multilayer perceptron with a multiresolution hash table, CardiacField maps coordinates to their associated intensities, capturing high-frequency components and detailed spatial features such as the complex endocardial contours.24,25 Compared with the 3DE probe, which is limited by factors such as electrical impedance mismatch of the transducers,9,10 CardiacField leverages the high-resolution capabilities of the 2DE probe combined with INR modelling to produce high-fidelity 3D heart images (Figures 3D and 4).

While this paper primarily examines the heart function evaluation capabilities of CardiacField, the system also offers features with potential research applications. Notably, it supports infinite sampling, demonstrated through the generation of 160 ‘New Views’ along the reconstructed 3D cardiac volume’s long and short axes. Furthermore, CardiacField can reconstruct a dynamic 3D heart within a single cardiac cycle, facilitating advancements in cardiac motion tracking analysis through integration with other AI algorithms. Unlike most neural networks designed for specific tasks, CardiacField creates a personalized digital twin of the heart, providing detailed and interpretable clinical features. We have made our data set of paired 2DE/3DE images and reconstructed 3D volumes available to the medical community to support further research (https://github.com/cshennju/CardiacField?tab=readme-ov-file).

Medical imaging systems rely on verifiable physical data, and computational and compressive imaging continue to demonstrate that algorithmic inference from incomplete data radically improves the capabilities of physical systems.26–28 In this paper, we show that a neural estimation strategy can be used to form 3D images of the heart from a sequence of 2D echocardiograms of the beating organ, which illustrates the value of a conceptual shift in diagnostic imaging from direct physical model inversion to Bayesian inference.

Limitations

The current image acquisition and processing time limits clinical implementation, as it exceeds the typical duration for a complete transthoracic echocardiographic examination. To address this limitation, we will explore several improvements based on our framework in future work. First, we are actively exploring the use of advanced generative AI techniques29 to significantly reduce the number of images required for reconstruction. Instead of acquiring 120 views, we aim to generate the necessary slices from fewer than 10 standard transthoracic echocardiographic views (e.g. four-chamber, three-chamber, and two-chamber views), substantially decreasing the image acquisition time. Second, in the area of INR, processing times are rapidly improving. For example, image rendering speeds have increased from ∼10 FPS with earlier neural network–based models such as SIREN23 to nearly 2000 FPS with the most advanced Gaussian Splatting model,30 without any loss of effectiveness. We are investigating the use of the Gaussian Splatting model to replace our neural network–based model to significantly improve reconstruction speed.

Additionally, although CardiacField reconstructs the four-chamber volumes effectively, it does not capture the detailed 3D morphology and function of the heart valves. Accurately modelling the dynamic changes in valve morphology during heartbeats remains a challenge and requires further investigation.

Another limitation is the potential underestimation of RV volume due to the exclusion of the RVOT in our LV-focused image acquisition method. Future work will focus on incorporating additional imaging planes that can clearly visualize the RVOT to achieve complete RV reconstruction.

Conclusions

Using a 2DE probe with a straightforward apical ring scan, our method automatically and accurately predicts LV and RV volumes and EFs comparable to those obtained from 3D imaging. It represents a novel volumetric solution for automatically assessing heart function that differs from other 2D data–driven DL tools, and illustrates the value of a conceptual shift in diagnostic imaging from direct physical model inversion to Bayesian inference.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Chengkang Shen, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Hao Zhu, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

You Zhou, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; Medical School, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China.

Yu Liu, Department of Echocardiography of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Si Yi, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Lili Dong, Department of Echocardiography of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Weipeng Zhao, Department of Echocardiography of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

David J Brady, College of Optical Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson 85721, AZ, USA.

Xun Cao, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Zhan Ma, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China.

Yi Lin, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai 200032, China.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Digital Health.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant nos. 62331005, 62071219, and 62025108 and in part by the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (STCSM) under grant no. 20Y11909800.

Data availability

All relevant data that support the finding of this study are available on GitHub at: https://github.com/cshennju/CardiacField?tab=readme-ov-file. The source code used in this work will be made publicly available on GitHub at: https://github.com/cshennju/CardiacField.

References

- 1. Marwick TH. Ejection fraction pros and cons: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2360–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2015;16:233–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang H, Nijjar PS, Misialek JR, Blaes A, Derrico NP, Kazmirczak F, et al. Accuracy of left ventricular ejection fraction by contemporary multiple gated acquisition scanning in patients with cancer: comparison with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2017;19:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Otterstad JE, Froeland G, St John Sutton M, Holme I. Accuracy and reproducibility of biplane two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements of left ventricular dimensions and function. Eur Heart J 1997;18:507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Purmah Y, Lei LY, Dykstra S, Mikami Y, Cornhill A, Satriano A, et al. Right ventricular ejection fraction for the prediction of major adverse cardiovascular and heart failure-related events: a cardiac MRI based study of 7131 patients with known or suspected cardiovascular disease. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14:e011337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Braga JR, Leong-Poi H, Rac VE, Austin PC, Ross HJ, Lee DS. Trends in the use of cardiac imaging for patients with heart failure in Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e198766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robinson S, Rana B, Oxborough D, Steeds R, Monaghan M, Stout M, et al. A practical guideline for performing a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram in adults: the British Society of Echocardiography minimum dataset. Echo Res Pract 2020;7:G59–G93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J 1984;107:526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Turnbull DH, Foster FS. Fabrication and characterization of transducer elements in two-dimensional arrays for medical ultrasound imaging. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 1992;39:464–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Prager RW, Ijaz UZ, Gee AH, Treece GM. Three-dimensional ultrasound imaging. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part H J Eng Med 2010;224:193–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ouyang D, He B, Ghorbani A, Yuan N, Ebinger J, Langlotz CP, et al. Video-based AI for beat-to-beat assessment of cardiac function. Nature 2020;580:252–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He B, Kwan AC, Cho JH, Yuan N, Pollick C, Shiota T, et al. Blinded, randomized trial of sonographer versus AI cardiac function assessment. Nature 2023;616:520–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tokodi M, Magyar B, Soós A, Takeuchi M, Tolvaj M, Lakatos BK, et al. Deep learning-based prediction of right ventricular ejection fraction using 2D echocardiograms. Cardiovasc Imaging 2023;16:1005–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eslami SA, Jimenez Rezende D, Besse F, Viola F, Morcos AS, Garnelo M, et al. Neural scene representation and rendering. Science 2018;360:1204–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Torralba A, Efros AA. Unbiased look at dataset bias. In: IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). Colorado: IEEE; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohamed F, Siang CV. A survey on 3D ultrasound reconstruction techniques. In: Artificial Intelligence—Applications in Medicine and Biology. Rijeka: InTechOpen; 2019, p73–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Spitzer E, Ren B, Soliman OI, Zijlstra F, Van Mieghem NM, Geleijnse ML. Accuracy of an automated transthoracic echocardiographic tool for 3D assessment of left heart chamber volumes. Echocardiography 2017;34:199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Medvedofsky D, Addetia K, Patel AR, Sedlmeier A, Baumann R, Mor-Avi V, et al. Novel approach to three-dimensional echocardiographic quantification of right ventricular volumes and function from focused views. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2015;28:1222–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yeung PH, Aliasi M, Papageorghiou AT, Haak M, Xie W, Namburete AIL. Learning to map 2D ultrasound images into 3D space with minimal human annotation. Med Image Anal 2021;70:101998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pellikka PA, She L, Holly TA, Lin G, Varadarajan P, Pai RG, et al. Variability in ejection fraction measured by echocardiography, gated single-photon emission computed tomography, and cardiac magnetic resonance in patients with coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e181456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ghorbani A, Ouyang D, Abid A, He B, Chen JH, Harrington RA, et al. Deep learning interpretation of echocardiograms. NPJ Digit Med 2020;3:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karniadakis GE, Kevrekidis IG, Lu L, Perdikaris P, Wang S, Yang L. Physics-informed machine learning. Nat Rev Phys 2021;3:422–440. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sitzmann V, Martel J, Bergman A, Lindell D, Wetzstein G. Implicit neural representations with periodic activation functions. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst 2020;33:7462–7473. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leshno M, Lin VY, Pinkus A, Schocken S. Multilayer feedforward networks with a nonpolynomial activation function can approximate any function. Neural Netw 1993;6:861–867. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu H, Xie S, Liu Z, Liu F, Zhang Q, Zhou Y, et al. Disorder-invariant implicit neural representation. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2024;46:5463–5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mait JN, Euliss GW, Athale RA. Computational imaging. Adv Opt Photonics 2018;10:409–483. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brady DJ, Mrozack A, MacCabe K, Llull P. Compressive tomography. Adv Opt Photonics 2015;7:756–813. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yuan X, Brady DJ, Katsaggelos AK. Snapshot compressive imaging: theory, algorithms, and applications. IEEE Signal Process Mag 2021;38:65–88. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu R, Wu R, Van Hoorick B, Tokmakov P, Zakharov S, Vondrick C. Zero-1-to-3: zero-shot one image to 3D object. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision. Paris, France: IEEE; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhang X, Ge X, Xu T, He D, Wang Y, Qin H. Gaussianimage: 1000 FPS image representation and compression by 2D Gaussian splatting. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Milan, Italy: Springer Science & Business Media; 2024. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data that support the finding of this study are available on GitHub at: https://github.com/cshennju/CardiacField?tab=readme-ov-file. The source code used in this work will be made publicly available on GitHub at: https://github.com/cshennju/CardiacField.