Abstract

3D printing offers a promising solution for the increasing demand for visually appealing dysphagia diets. Xanthan gum (XG) is a critical component in various thickeners specialized for dysphagia diets, in which pyruvate group is important, but relative study remains scarce. This study tried to create 3D printed dysphagia diet using composite gels of pea protein (PPI) and XG with various pyruvate content (XG0: 5.20 %, XG1: 1.87 %, XG2: 0.54 %, XG3: 0.10 %). Results revealed that decreasing pyruvate content resulted in significant reductions of both viscosity and mechanical strength of PPI-XG gel. In particular, at a shear rate of 1 s−1, the viscosity of PPI-XG0, PPI-XG1, PPI-XG2, and PPI-XG3 gels were 714.36 Pa·s, 525.32 Pa·s, 427.32 Pa·s, and 421.16 Pa·s, respectively. The PPI-XG interaction significantly affected by pyruvate, especially concerning electrostatic interactions. The PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 samples exhibited excellent 3D printing performance and could be categorized into level 4-pureed dysphagia diets within IDDSI framework. This research offers valuable insights for the development of 3D printed dysphagia diets, and for the standardization of XG specialized for dysphagia diets.

Keywords: Dysphagia diet, Pyruvate, Xanthan gum, Additive manufacturing

Highlights

-

•

XG with different pyruvate contents were used to modify PPI gel properties.

-

•

PPI-XG composite gel was used to create 3D printed dysphagia diet.

-

•

Pyruvate group considerably affect chewing/swallowing behavior.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, pea protein has gained recognition as an innovative source of plant-based protein for vegans. Field peas contain 23.1 % to 30.9 % protein, 1.5 % to 2.0 % fat, along with small amounts of vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols. Pea protein is characterized by its affordability, nutritional richness, broad accessibility, and health benefits, including its potential to mitigate obesity and alleviate atherosclerosis. These attributes have led to its extensive application in food products targeted at the elderly (Boye et al., 2010; Lam et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2024).

Challenges such as tooth loss, diminished saliva production, and weakened tongue muscles have led to a sharp rise in chewing and swallowing difficulties among elderly (Liu et al., 2024). Consequently, the development of foods that are not only easy to chew but also appealing enough to enhance appetite is essential for supporting healthy aging society. At present, foods designed for individuals with dysphagia are typically offered in pureed or paste forms, which often lack the sensory qualities needed to effectively stimulate appetite for the elderly (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b).

3D printing offers notable advantages, including the ability to personalize nutrition, create visually appealing structures, and adjust texture through tailored internal designs to ease chewing and swallowing (Liu et al., 2024; Liu, Bhandari, et al., 2018). This technology has the potential to enhance traditional dysphagia diets by transforming the typical pureed or paste-like presentation into more visually appealing, easily consumable foods with desirable textures. Recently, 3D printing for dysphagia friendly foods has gained attention as a prominent area of research worldwide. Ingredients used in 3D printed dysphagia diets range from fresh produce (Bhat et al., 2021), such as fruits/vegetables (Pant et al., 2021; Qiu et al., 2023; Sartori et al., 2023), fish (Zhu et al., 2023), dairy products (Bitencourt et al., 2023), and various gums, starches, and polysaccharides (Xing et al., 2022; Εkonomou et al., 2024). Overall, 3D printing plays a vital role in creating diets that address the unique needs of individuals with swallowing difficulties, ultimately enhancing their quality of life.

Xanthan gum (XG) is widely utilized in dysphagia diets due to its effective thickening and shear-thinning properties, its stability against salivary enzymes and high resistance to both acidic and alkaline conditions (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b; Liu et al., 2024; Xing et al., 2022; Yabe, Kudo, & Horiuchi, 2024). This ingredient serves as a foundational component in numerous commercial thickeners for dysphagia diets, including the Softia thickener by NUTRI Co. Ltd. and Nestlé's ThickenUp®. It has been utilized to modify the swallowing characteristics of various dysphagia diets, such as riceberry porridge (Charoensri, Aspinall, Liu, & Kijroongrojana, 2024), vegetable mixtures (Hassan, Gani, & Mudabir, 2024), and pork (Dick, Bhandari, Dong, & Prakash, 2020). Compared to starch-based thickeners, XG offers superior stability against salivary amylase, making it less susceptible to breakdown (Hadde, Mossel, Chen, & Prakash, 2021). In preliminary studies, we observed that XG consistently improved the ease of chewing and swallowing in 3D printed food samples made from ingredients like pea protein and edible fungi by decreasing the sensation of retention and adhesion in the mouth and throat (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b; Xing et al., 2022). Additionally, we noted considerable variation in XG from different sources influences chewing and swallowing properties of foods, which affects the standardization of XG formulations tailored for dysphagia diets; however, the causes behind these differences remain unclear.

The backbone structure of XG is composed of β-(1 → 4) linked d-glucose, mirroring the structure of cellulose; however, every second glucose unit has a trisaccharide side chain comprising two mannose residues separated by a glucuronic acid unit. Pyruvate residues, typically present on 30–40 % of the terminal mannose residues, vary according to bacterial strain or chemical modifications (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015). Positioned on the exterior of XG's helical conformation, the pyruvate group extends the branch length and increases charge density, which profoundly influences XG's molecular configuration and its interactions with other substances (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019). The presence of pyruvate also significantly impacts the viscosity of XG solutions (Cheetham & Norma, 1989). Acetyl groups are essential for promoting interactions between the molecular backbone and side chains, as well as facilitating inter-molecular associations. In XG, their presence significantly affects the molecular conformation and intrinsic properties, and they are widely acknowledged for contributing to the stabilization of XG's helical structure (Kool et al., 2014). Pyruvate additionally affects how XG interacts with colloidal substances like konjac glucomannan (KGM) (Qiao et al., 2023). Depending on the conformational transition temperature of XG, influenced by pyruvate groups and other factors, XG can interact with KGM either through a helical or random coil conformation (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Qiao et al., 2023). Studies on the KGM/XG system reveal two binding types: type-A and type-B. During cold-set gelation, type-A involves interactions between KGM chains and XG's helical form within a temperature range of 40–25 °C, whereas type-B involves interactions between KGM and disordered XG within 55–40 °C (Qiao et al., 2023; Qiao et al., 2024). In summary, the pyruvate group in XG is crucial for its conformational transitions, shear-thinning behavior, and interaction with other colloidal substances (Cheetham & Norma, 1989; Qiao et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019). In addition, the interactions between XG and protein have been reported. As the pH increases, the primary interactions between XG and amaranth protein gradually shift from electrostatic attraction to hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022). Electrostatic gels can form between oppositely charged protein and XG molecules through electrostatic attraction, with the strongest interaction observed when the pH lies between the isoelectric point (pI) of the protein and the pKa of the polysaccharide (Le & Turgeon, 2013). Additionally, covalent bonding can occur, such as through the Maillard reaction, which has been used to prepare covalent conjugates of pea protein and xanthan gum (Choi et al., 2023). However, to our knowledge, no research has yet explored how XG's pyruvate content influences its interactions with proteins or the effects on 3D printing and swallowing properties.

This study aimed to investigating the feasibility to create appealing 3D printed dysphagia diet based on complex gel of PPI and XG. The XG with varying pyruvate content was firstly prepared using acidic thermal treatment. Afterwards, the rheological properties of PPI-XG composite gels and their 3D printing behaviors, feasibility to be as dysphagia diet were evaluated, as well as the molecular interactions between PPI and XG. This work not only provides insights for the development of 3D printed visually appealing dysphagia diet, but also provides guidance for the standardization of XG specifically designed for dysphagia diet applications.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Xanthan gum (XG) was purchased from Fufeng Group Co. Ltd. (Shandong Province, China), with moisture content of 7.3 %, purity of 99 %, total nitrogen of 0.5 %, and ash content of 10.7 %. Pea protein (PPI), with purity greater than 90 % was obtained from Longzhou Biotechnology Co. Ltd. (Shaanxi, China). Potassium bromide and sodium chloride (NaCl) in AR grade were provided by Sinopharm Group (Shanghai, China). Oxalic acid and ethanol absolute (AR grade) were purchased from Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, China) and Tianli Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. (Tianjin, China), respectively.

2.2. Preparation of XG with different pyruvate contents

XG with different pyruvate contents was obtained through an acid-heat treatment method with slight modification (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Fu, Su, Chen, Li, Zhang, et al., 2021). Specifically, 1 g/L XG was dissolved in a 0.01 mol/L oxalic acid solution (containing 0.1 mol/L NaCl). Under continuous magnetic stirring, the solution was treated at 80 °C, 90 °C, and 100 °C for 3 h, respectively, and then cooled to room temperature. The initial pH value was then adjusted. Afterwards, XG with varying pyruvate content was obtained through two rounds of ethanol precipitation, redissolution, rotary evaporation (to remove residual ethanol), freeze-drying, and grinding. The obtained XG at different temperatures were labeled as XG1, XG2, and XG3, respectively. The original XG without treatment was labeled as XG0, served as the control group. The pyruvate content of XG samples was determined using a standard curve method (Qiao et al., 2023).

2.3. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) test of different XG samples

FT-IR was conducted with a spectrometer (Bruker Co. Ltd., Germany). Initially, samples were firstly freeze dried, making them into a fine powder, then combined with potassium bromide at an approximate 1:100 (w/w) ratio. The mixture was then pressed into a pellet about 1 mm thick and analyzed within the 4000–400 cm−1 range (Yang et al., 2023).

2.4. Rheological properties

A rheometer (TA Co. Ltd., UK) was used to analyze rheological properties, employing a 40 mm plate geometry with a 1000 μm gap (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b). To prevent moisture loss, a thin silicone oil layer was applied around the geometry prior to starting the experiments. The samples were equilibrated for 5 min to reach a steady state. Viscosity was taken over a shear rate of 0.1–100 s−1. Oscillatory strain test was conducted at 1 Hz at strain of 0.01 % ∼ 100 %. Temperature-responsive behavior of XG solutions was evaluated with a temperature increase rate of 1 °C/min.

2.5. Preparation of XG solutions and heat-induced PPI-XG gel

XG solutions: Dispersed 0.3 % XG (on the basis of water) with different pyruvate contents (XG0, XG1, XG2, and XG3) in deionized water and stir evenly under magnetic stirring. They were then heated at 92 °C for 1 h. To prevent moisture loss, a thin layer of plastic wrap was placed over the container during heating. Afterward, the solutions were cooled to room temperature for further analysis.

Heat-induced PPI-XG gel: The XG (0.3 %) with various pyruvate content were firstly mixed uniformly with 25 % PPI to prevent XG particle aggregation in gel preparation (based on water weight). The mixed suspensions in deionized water were heated at 92 °C for 1 h to form gels, with a thin plastic wrap layer covering the container to minimize water evaporation. Following heating, they were cooled and stored at 4 °C overnight for further analysis.

2.6. 3D printing

A 3D printer produced by Shiyin Tech. Co., Hangzhou, China was used for the printing tests; detailed specifications are available in our prior study (Liu, Zhang, & Yang, 2018), with the parameters as follows: printing temperature of 25 °C, nozzle diameter of 1.2 mm, rectilinear infill pattern, and 100 % infill density. Printability was assessed by fabricating a hollow cylinder, with print quality evaluated through the successful printing percentage (PP) of these cylinders. Here, Ttotal represents the total time needed to print a cylinder successfully, while Tleft marks the remaining time when the nozzle begins to deviate from the printed structure. A PP value of 100 % reflects a fully successful print, whereas a lower PP suggests a tendency toward collapse and deformation, indicating reduced printability (Martinez-Monzo, Cardenas, & Garcia-Segovia, 2019).

2.7. Water mobility analysis

A LF-NMR analyzer (Numag Technology Co., Suzhou, China) was utilized to assess water mobility. For each test, approximately 5 g of the slurry sample was weighed, wrapped in cling film, and then placed into a glass tube before being inserted into the analyzer. The testing parameters were as follows: spectral width of 100 kHz, echo count of 3000, scan cycle number of 4.

2.8. Study on molecular interaction of gel formation

The interactive effects were elucidated by referencing earlier studies (Sun & Arntfield, 2012; Wang, Yang, Li-Sha, & Chen, 2020). Denaturants such as urea, NaCl, and SDS were employed to disrupt hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interaction, and hydrophobic interaction. Different concentrations of urea, NaCl, and SDS were introduced into the PPI-XG complex system prior to heating at 92 °C for 1 h. The samples were then stored at 4 °C to facilitate gel formation. The changes in hardness were evaluated using a texture analyzer with the following testing parameters: pre-test/test/post-test speed set to 2 mm/s, trigger force at 5 g, and compression strain at 50 %. Each condition was replicated three times.

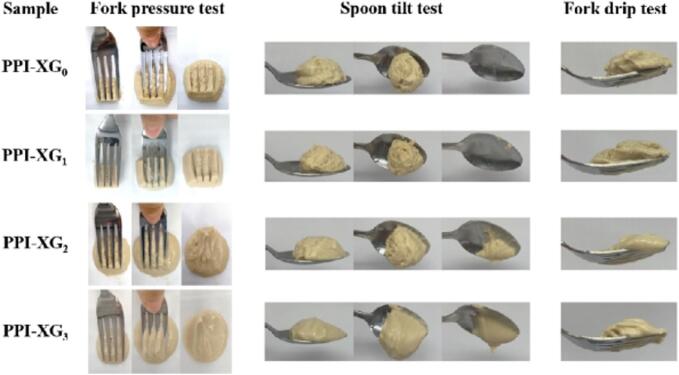

2.9. IDDSI tests

The IDDSI outlines eight levels of food and drink suitable for individuals with dysphagia (International-Dysphagia-Diet-Standardisation-Initiative, 2019). Based on our prior assessment, the samples demonstrated potential suitability for level 4 -pureed dysphagia diets. Under the IDDSI framework, a Level 4 pureed dysphagia diet should meet the following characteristics: typically consumed using a spoon, though a fork may also be used; unsuitable for drinking from a cup due to its limited flow; incapable of being sucked through a straw; does not require chewing; can be shaped, layered, or piped as it maintains its form; exhibits minimal movement under gravity but is not pourable; drops off a spoon in one cohesive spoonful when tilted, retaining its form on a plate; free of lumps; non-sticky; and demonstrates no separation of liquid from solid components (International-Dysphagia-Diet-Standardisation-Initiative, 2019). Specifically, the samples were tested with the fork pressure test, fork drip test, and spoon tilt test in accordance with IDDSI guidelines. The fork drip test was performed by scooping the sample using a fork and observing sample's flow behavior through the fork's prongs. Spoon tilt measurement was conducted by filling a teaspoon with the sample, holding the spoon above a plate, and gradually tilting it sideways. Additionally, fork pressure measurement was conducted with pressure was applied to the top surface of the sample with a fork, and the resulting deformation was recorded.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS, and significant differences among the samples were assessed with Duncan's tests, applying a significance level of P < 0.05. Origin software was utilized for graphing.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. The effect of pyruvate group on the physicochemical properties of XG

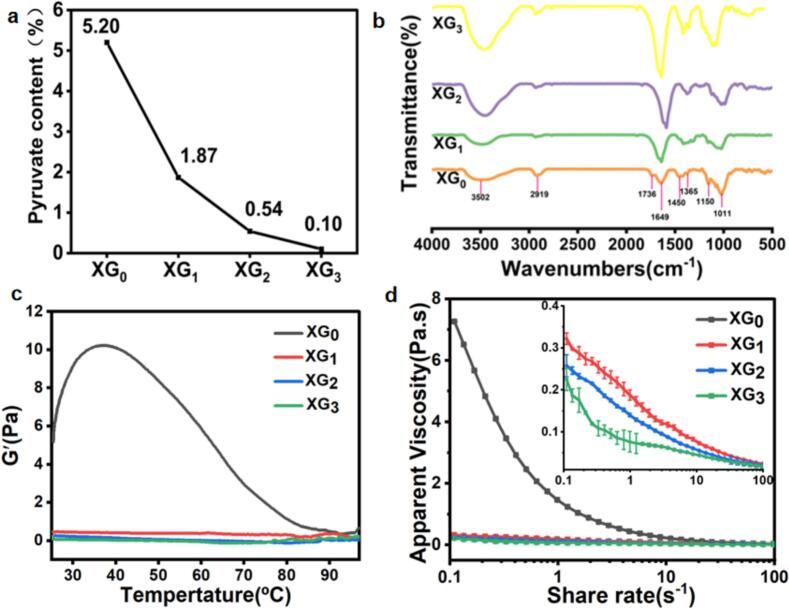

An acid heat treatment technique was employed to partially eliminate pyruvate groups from XG (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Fu, Su, Chen, Li, Zhang, et al., 2021). This approach aimed to investigate how varying levels of pyruvate affect the physicochemical properties of XG and its interactions with PPI. The modified XG samples—designated as XG0, XG1, XG2, and XG3—contained pyruvate levels of 5.20 %, 1.87 %, 0.54 %, and 0.10 %, respectively (Fig. 1a). These findings suggest that the acidic thermal treatment effectively reduced the pyruvate content in XG, consistent with previous studies (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Fu, Su, Chen, Li, Zhang, et al., 2021).

Fig. 1.

(a) Pyruvate content of prepared different XG samples; (b) Infrared spectral absorption behavior of of different XG; (c) Temperature responsive behavior of XG solutions with different pyruvate content; (d) Apparent viscosity of XG samples with different pyruvate contents.

FTIR is a valuable technique for identifying similarities and differences in the primary structures of polysaccharides. As shown in Fig. 1b, the FTIR spectra of different XG samples were analyzed to determine the functional groups within their structures. The bands observed at approximately 3500 cm−1 and 2919 cm−1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of O—H bonds and the asymmetrical stretching of C—H bonds in the methane and methylene (CH₂) groups present in XG molecules, respectively (Yang et al., 2023). Absorption peaks at 1736 cm−1 and 1649 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibrations of C O and the asymmetric vibrations of C O in the carboxylate groups of pyruvate and glucuronic acid. Additionally, peaks around 1450 cm−1 were linked to -COO groups, while those at 1365 cm−1 and 1011 cm−1 were associated with the C-O-C stretching vibrations of the pyranose ring (He et al., 2022). It was noted that the characteristic peaks in the FTIR spectra of various XG samples were nearly identical, with the exception of the peak around 1736 cm−1, which corresponds to the C O stretching vibration in the carboxylate group of pyruvate (He et al., 2022) and was present only in the native xanthan gum XG0. This observation suggests that the acid-heat treatment effectively removed the pyruvate group, rendering the pyruvate content in XG1 (1.87 %), XG2 (0.54 %), and XG3 (0.10 %) likely undetectable.

Fig. 1c depicts how the content of pyruvate affects the temperature-responsive behavior of XG. As pyruvate groups are partially removed, the temperature-responsive characteristics of XG gradually decrease, with no significant alteration observed in the G′ values. In contrast, XG0 exhibits a marked increase in G′ with decreasing temperature, which may indicate a transition between ordered and disordered state of the XG molecules. Previous studies have indicated that pyruvate groups are directly linked to this order-disorder transition in XG. These groups tend to promote a disordered configuration by reducing electrostatic repulsion as the side chains extend from the main chain (Li & Feke, 2015). The negatively charged pyruvate groups create an electrostatic shielding effect, which prevents the entanglement and folding of the side chains with the main chain of XG. When the pyruvate groups are removed, the intramolecular forces in XG molecules become stronger, facilitating the formation of a compact helical structure. However, the reduction in intermolecular hydrogen bonding leads to an increase in the temperature at which G′ undergoes a sharp change, indicating a higher temperature for the transition from disordered to ordered states (Fu, Su, Chen, Li, Zhang, et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2019).

Fig. 1d presents the steady-state shear viscosity of XG samples with different levels of pyruvate. All examined XG samples displayed non-Newtonian shear-thinning behavior, characterized by a reduction in viscosity as the shear rate increased. At low shear rates, the highly ordered network of entangled, rigid XG molecules demonstrated remarkable suspending properties and high viscosity. However, as the shear rate increased, shear-thinning behavior occurred due to the disaggregation of the XG network and the alignment of individual xanthan molecules in the direction of the applied shear force (Wu et al., 2019). The viscosity of these samples is notably influenced by the pyruvate content, with overall viscosity decreasing as pyruvate groups are eliminated. The XG0 solution exhibited the highest viscosity, likely because pyruvate groups are located at the edges of the helical structure, allowing them to participate more in intermolecular interactions than in intramolecular interactions. This interaction promotes greater association and structure formation among neighboring XG molecules through enhanced polymer-polymer interactions compared to the affinity for the solvent. Thus, XG rich in pyruvate tends to produce more viscous solutions compared to those with lower pyruvate concentrations at similar levels (Li & Feke, 2015). Moreover, as pyruvate groups are removed, the gradual loss of the electrostatic shielding effect, due to the negatively charged side chains of XG, could strengthen intramolecular hydrogen bonding. This results in a more compact helical structure of XG, while intermolecular hydrogen bonding weakens, leading to diminished gel-like properties and an increased manifestation of fluid characteristics (Fu, Su, Chen, Li, Zhan, et al., 2021). It has been observed that acetyl groups stabilize the ordered conformation of XG, while the electrostatic repulsion from pyruvate groups has an opposing effect. This phenomenon is consistent with previous findings that high-pyruvate XG is more viscous than its low-pyruvate counterpart, as the pyruvate groups destabilize the helical conformation through intermolecular associations among XG (Abbaszadeh et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019).

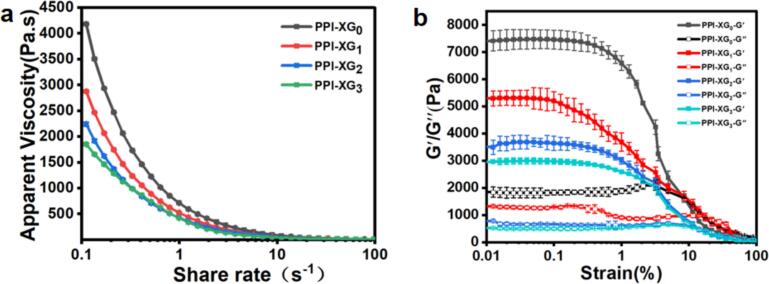

3.2. The effect of pyruvate group on the rheology of PPI-XG gel

Rheological properties are crucial for understanding 3D printing behavior as well as the characteristics of foods suitable for individuals with swallowing difficulties. Viscosity and viscoelastic properties are widely recognized as essential factors influencing both the printability of materials and the formulation of dysphagia diets (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b; Xing et al., 2022). The viscosity of a material is related to the minimum force required to initiate and maintain the flow of ink. For optimal 3D printing, inks must have low viscosity for easy extrusion, while also demonstrating sufficient viscosity post-extrusion to bond with previously laid layers. Consequently, a shear-thinning behavior is preferred (Liu, Bhandari, Prakash, Mantihal, & Zhang, 2019). As for dysphagia diets, shear-thinning is advantageous because it facilitates easier swallowing of viscous food boluses and reduces the risk of aspiration during the chewing process, especially when shear stress is applied by the tongue (Wei et al., 2021). Fig. 2a illustrates that the viscosity of the PPI-XG ink decreases when shear rate increases, suggesting shear-thinning characteristics. Specifically, the viscosity of the PPI-XG0 ink sample dropped significantly from 4182.80 Pa·s to 78.41 Pa·s as the shear rate increased from 0.1 s−1 to 11 s−1. Beyond a shear rate of 11 s−1, the viscosity of the samples tended to converge, showing little variation regardless of the pyruvate content in the XG. Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b also noted that the mixed gel systems of XG and PPI exhibited shear-thinning behavior, with viscosity highly dependent on the concentration of XG. Moreover, the viscosity of the PPI-XG samples decreased with the reduction of pyruvate content, particularly at lower shear rates (less than 1 s−1) (Fig. 2a). At a shear rate of 1 s−1, the viscosities of the PPI-XG0, PPI-XG1, PPI-XG2, and PPI-XG3 gels were 714.36 Pa·s, 525.32 Pa·s, 427.32 Pa·s, and 421.16 Pa·s, corresponding to pyruvate contents of 5.20 %, 1.87 %, 0.54 %, and 0.10 %, respectively. This trend may be explained by the significant role of electrostatic interactions between XG and PPI. The pyruvate groups in XG carry a negative charge, allowing them to interact electrostatically with the positively charged groups on PPI molecules. The strength of these interactions is directly influenced by charge density (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b), thereby affecting the rheological properties of the PPI-XG mixed gels. Additionally, the removal of pyruvate groups reduces charge density, weakening the interaction intensity between XG and protein (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; McClements, 2006). Because pyruvate group is situated at the exterior of the helical structure, it is more likely to participate in intermolecular rather than intramolecular interactions (Kool et al., 2014; Li & Feke, 2015). Consequently, these groups tend to promote a disordered state, enhancing polymer–polymer interactions relative to polymer–solvent affinity, such as XG-XG or XG-PPI interactions. As a result, XG with higher pyruvate content typically forms a stronger network structure, exhibiting greater viscosity and mechanical strength than pyruvate-lean XG at comparable concentrations (Li & Feke, 2015; Smith et al., 1981).

Fig. 2.

(a) Viscosity versus shear rate of PPI-XG gel; (b) Oscillation strain profiles of PPI-XG gel.

The viscoelastic properties are crucial for the self-supporting characteristics of 3D printed structures (Liu, Bhandari, Prakash, Mantihal, & Zhang, 2019) and also contribute to the sensory properties during swallowing (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b; Xing et al., 2022). As illustrated in Fig. 2b, the PPI-XG mixed systems formed network structures that exhibited predominant elastic characteristics, typical of gel-like materials. In these systems, the storage modulus (G′) consistently surpassed the loss modulus (G′′) until they intersected at a point where the two values became equal. These findings are consistent with observations reported in earlier study (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b). Furthermore, within the linear viscoelastic region, both G′ and G′′ for the PPI-XG mixed gels were found to decrease as the pyruvate content diminished, following the order: PPI-XG0 > PPI-XG1 > PPI-XG2 > PPI-XG3. This trend likely arises from the negatively charged pyruvate groups in XG molecules, which engage in interactions with positively charged protein molecules. The strength of these interactions appears to diminish with the removal of pyruvate groups (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; McClements, 2006). Located at the periphery of the XG helical structure, the pyruvate groups are more inclined to facilitate intermolecular interactions rather than intramolecular ones, thereby enhancing the interactions between XG and PPI molecules and leading to the development of a denser network structure (Li & Feke, 2015; Smith et al., 1981).

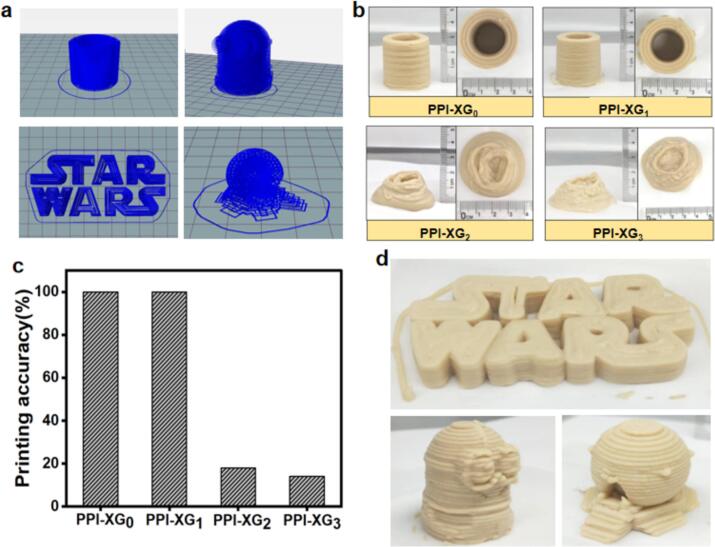

3.3. Effect of pyruvate group on the 3D printing behaviors of PPI-XG gel

The printability of the 3D structures was evaluated by creating a hollow cylinder. The results revealed that samples printed with PPI-XG2 and PPI-XG3 exhibited significant deformation and entirely lost their intended shape (Fig. 3). This failure was primarily attributed to their inadequate strength to maintain self-support, which could not withstand the force of gravity, as indicated by their lower G′. Conversely, the samples produced using PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 closely matched the intended geometry, showcasing a smooth surface and achieving a printing percentage of 100 % (Fig. 3). This success can be linked to the higher pyruvate content in the PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 gel samples, which provided sufficient mechanical strength (as indicated by a higher G′, Fig. 3) to remain self-supportive and resist deformation caused by gravitational forces. The strong electrostatic interactions between the XG and PPI components, facilitated by the negatively charged pyruvate groups of XG and the positively charged areas of PPI, were crucial in this process. The charge density significantly influences the strength of these interactions, and the removal of pyruvate groups from XG weakens this interaction (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b; McClements, 2006). Fig. 3 showcases more intricate structures produced with PPI-XG1. These samples exhibited an appealing appearance with a smooth surface compared to traditional mashed diets, which can enhance the appetite and eating experience for elderly individuals with dysphagia. Prior research has also indicated that the addition of XG enhances the creaminess and smoothness perceptions of mashed potatoes due to its coating properties (Alvarez et al., 2009).

Fig. 3.

(a) Designed models used for 3D printing; (b) 3D printed hollow cylinder using different PPI-XG gel; (c) Printing percentage of hollow cylinders using different PPI-XG gel; (d) 3D printed representative images using PPI-XG1 gel.

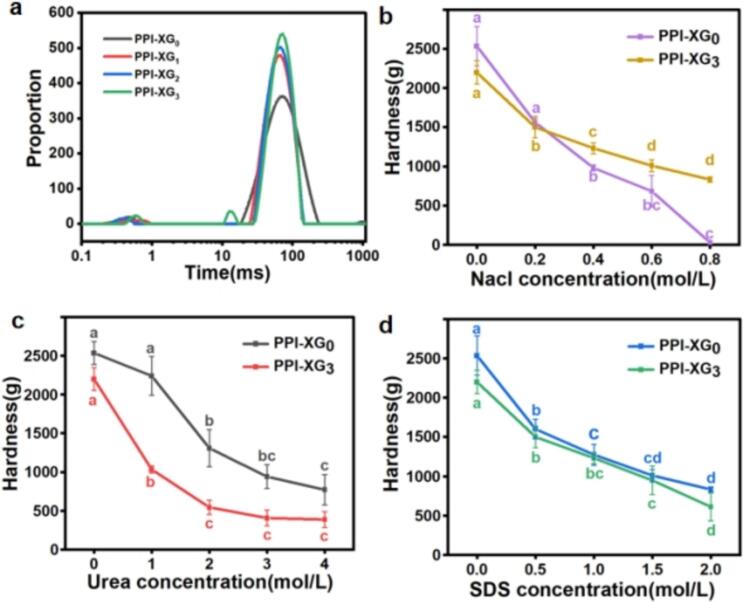

3.4. Effect of pyruvate group on the water mobility of PPI-XG complex system

The movement of water molecules is heavily influenced by the gel structure, which is intrinsically linked to the rheological properties of the material. The relaxation time serves as an indicator of the chemical environment and the degree of freedom of hydrogen protons, which correlates with the internal structure of the sample. A longer relaxation time suggests a higher degree of freedom (Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b). As illustrated in Fig. 4a, two distinct water populations were identified in the PPI-XG0, PPI-XG1, and PPI-XG2 samples, with peak times occurring approximately at 0.3–0.5 ms and 65–70 ms. In contrast, the PPI-XG3 sample exhibited three water populations with peak times at 0.6 ms, 12.7 ms, and 72.3 ms. The water population with peak times around or below 10 ms indicates less mobile water fractions that are tightly bound to biopolymers, such as the XG and PPI molecules. The population around 65–75 ms, which constitutes a significant proportion, reflects a more mobile water fraction. This mobility increases as the pyruvate content decreases, suggesting that the removal of the pyruvate group enhances water mobility and results in a weaker gel structure. This observation aligns with the lower viscosity and G′ values recorded for the PPI-XG3 sample (Fig. 3). This behavior can be attributed to the non-covalent interactions among PPI and XG, which include electrostatic forces, hydrophobic interactions, van der Waals forces, and hydrogen bonding. These interactions are contingent upon the characteristics of the biopolymers and the surrounding conditions (Gentile, 2020; Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b). Since both proteins and polysaccharides primarily exist as charged entities in solution, electrostatic interactions play a crucial role in mediating the non-covalent interactions between these macromolecules (Gentile, 2020; Liu et al., 2023a, Liu et al., 2023b). The negatively charged pyruvate groups, located on the trisaccharide side chain of XG and positioned on the exterior of the helical conformation, significantly influence the charge density. The elimination of pyruvate groups results in a decrease in the charge density of XG, thereby weakening its interactions with proteins (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; McClements, 2006).

Fig. 4.

(a) Water mobility of PPI-XG gel; (b, c, d) Effect of b) NaCl, c) urea, d) SDS on hardness change of PPI-XG gel samples.

3.5. Effect of pyruvate group on the molecular interaction between XG and PPI

Interactions among proteins and polysaccharides encompass various types of interactions, including covalent bonds, electrostatic forces, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and steric exclusion (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; McClements, 2006). The type and intensity of these interactions are crucial in determining the stability and rheological characteristics of numerous processed foods, significantly influencing the structure and texture desired in food products. To elucidate the internal driving forces within the PPI-XG complex system, researchers employed perturbing agents such as urea, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and NaCl to inhibit these interactions and subsequently analyzed the hardness of the gels. Urea effectively disrupts hydrogen bonds within the side chains and backbone of proteins, while SDS targets hydrophobic interactions, and NaCl interferes with electrostatic forces (Yue et al., 2022). As shown in Fig. 4b, increasing the concentration of NaCl from 0.0 to 0.8 mol/L resulted in a significant decline in gel hardness for PPI-XG0, indicating the critical role of electrostatic interactions in forming the mixed gel system. This reduction in hardness is likely attributable to NaCl screening the charges on the polymers (Xi, Al, Dan, Yga, & Ls, 2021). These findings align with previous studies highlighting that electrostatic interactions are the primary determinants of thermodynamic compatibility or incompatibility between proteins and polysaccharides (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022). In contrast, while the gel hardness of PPI-XG3 also decreased with higher NaCl concentrations, the extent of reduction was notably less pronounced than that observed in PPI-XG0. This discrepancy may stem from the significantly greater pyruvate content present in XG0 compared to XG3. Since the pyruvate group possesses a negative charge, the introduction of NaCl can effectively shield the charged groups on XG molecules (Brunchi et al., 2019), thereby modifying their interactions with proteins. Furthermore, an increase in urea concentration from 0 to 4 mol/L resulted in a marked decrease in gel hardness for both PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG3 (Fig. 4c), indicating the significance of hydrogen bonding in the complex gel formation. Hydrophobic interactions also play a vital role in the creation of the PPI-XG complex gel system, as evidenced by the substantial decrease in gel hardness following SDS addition (Fig. 4d). This observation supports earlier findings that the interactions between proteins and polysaccharides involve covalent, electrostatic, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonds (Cortez-Trejo et al., 2022; McClements, 2006).

3.6. IDDSI tests

IDDSI has established a global standard along with testing methodologies for assessing foods intended for individuals with dysphagia (International-Dysphagia-Diet-Standardisation-Initiative, 2019). To determine the suitability of various samples as dysphagia-friendly foods, we conducted several tests, including the spoon tilt, fork pressure, and fork drip assessments (Fig. 5). The fork drip test involved examining the flow characteristics of ink samples as they passed through the tines of a fork. Our observations indicated that samples PPI-XG2 and PPI-XG3 exhibited slow flow through the fork, resulting in the formation of a short tail below the utensil. This behavior can likely be attributed to their relatively low viscosity and diminished mechanical strength, as evidenced by their lower G′ values. In contrast, other samples remained piled above the fork without any flow through the prongs, suggesting their potential classification as level 4-pureed foods within the IDDSI framework. In addition, the fork pressure test revealed that all samples could be easily mashed with minimal effort, producing a surface pattern without any lumps. The samples also showed significant deformation upon light pressure application, which did not cause the thumbnail to blanch. Consequently, these results indicated that all samples successfully passed the fork pressure assessment and were suitable for categorization as level 4 pureed dysphagia foods according to IDDSI guidelines. The spoon tilt test, a recommended method for assessing the stickiness and cohesiveness of samples within the IDDSI framework. During this test, both PPI-XG2 and PPI-XG3 were found to be excessively sticky, failing to slide off the spoon and leaving a considerable amount of food behind. This stickiness rendered these samples unsuitable for a dysphagia diet, as it poses an increased choking risk and requires significant lingual effort to maneuver food into the pharynx (Berzlanovich, Fazenydorner, Waldhoer, Fasching, & Keil, 2005; Cichero, 2016; Suebsaen et al., 2019). In contrast, the PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 samples demonstrated significantly reduced food residues on the spoon and exhibited a smooth texture that allowed them to slide off easily when the spoon was tilted. This characteristic is advantageous for dysphagia diets, as it facilitates swallowing without the risk of food adhering to the tongue or pharynx (Berzlanovich, Fazenydorner, Waldhoer, Fasching, & Keil, 2005; Cichero, 2016; Suebsaen et al., 2019). In summary, the results of the IDDSI tests indicate that the PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 samples can be classified as level 4-pureed dysphagia diet within the IDDSI framework.

Fig. 5.

Fork pressure test, fork drip test, and spoon tilt test of PPI-XG gel samples.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that pyruvate groups significantly influence the interaction between XG and PPI, as well as the rheological properties, 3D printability and chewing behaviors of the PPI-XG composite gel. With the removal of pyruvate group, the viscosity and mechanical strength, and 3D printability of composite gel reduced significantly. The molecular interactions, particularly electrostatic interaction was considerably affected by the pyruvate content. The PPI-XG0 and PPI-XG1 samples illustrated desirable 3D printing precision and could be classified as level 4-pureed/extremely thick dysphagia diet within IDDSI framework.

The molecular structure of XG is relatively complex, and numerous factors influence its interactions with proteins. In future, we would continue to investigate the effects of molecular structures such as XG's molecular weight, pyruvate groups, acetyl groups, pyruvate/acetyl group ratio of trisaccharide side chain, and the six-constituent xanthan repeating units, on the interaction between proteins and XG and resultant composite gel properties and chewing/swallowing behaviors. We aimed to provide a theoretical foundation for the standardization of XG tailored for foods designed for dysphagia patients, which is of great significance for the development of dysphagia diets in the rapid aging society.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zhenbin Liu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Xi Chen: Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Meirong Ruan: Writing – original draft, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Yumei Liao: Resources, Conceptualization. Zihao Wang: Software, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. Yucheng Zeng: Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization. Hongbo Li: Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation. Liangbin Hu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Conceptualization. Haizhen Mo: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Postdoctoral Research Excellence Funding Program of Zhejiang Province (ZJ2023100), and Innovation Capability Support Program of Shaanxi Province (Program No. 2023-CX-TD-61) have enabled us to carry out this study.

Contributor Information

Liangbin Hu, Email: hulb@sust.edu.cn.

Haizhen Mo, Email: mohz@sust.edu.cn.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abbaszadeh A., Lad M., Janin M., Morris G.A., MacNaughtan W., Sworn G., Foster T.J. A novel approach to the determination of the pyruvate and acetate distribution in xanthan. Food Hydrocolloids. 2015;44:162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2014.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez M.D., Fernández C., Canet W. Enhancement of freezing stability in mashed potatoes by the incorporation of kappa-carrageenan and xanthan gum blends. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2009;89(12):2115–2127. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berzlanovich A., Fazenydorner B., Waldhoer T., Fasching P., Keil W. Foreign body asphyxia: A preventable cause of death in the elderly. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(1):65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat Z.F., Morton J.D., Kumar S., Bhat H.F., Aadil R.M., Bekhit A.E.-D.A. 3D printing: Development of animal products and special foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2021;118:87–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bitencourt B.S., Guedes J.S., Saliba A.S.M.C., Sartori A.G.O., Torres L.C.R., Amaral J.E.P.G., Alencar S.M., Maniglia B.C., Augusto P.E.D. Mineral bioaccessibility in 3D printed gels based on milk/starch/ĸ-carrageenan for dysphagic people. Food Research International. 2023;170 doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boye J., Zare F., Pletch A. Pulse proteins: Processing, characterization, functional properties and applications in food and feed. Food Research International. 2010;43(2):414–431. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunchi C.-E., Avadanei M., Bercea M., Morariu S. Chain conformation of xanthan in solution as influenced by temperature and salt addition. Journal of Molecular Liquids. 2019;287 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charoensri P., Aspinall S., Liu F., Kijroongrojana K. Rheological, textural, and swallowing characteristics of xanthan gum-modified Riceberry porridge for patients with dysphagia. Journal of texture studies. 2024;55(4) doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham N.W.H., Norma N.M.N. The effect of pyruvate on viscosity properties of xanthan. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1989;10(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0144-8617(89)90031-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.W., Ham S.H., Hahn J., Choi Y.J. Developing plant-based mayonnaise using pea protein-xanthan gum conjugates: A maillard reaction approach. LWT. 2023;185 doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cichero J.A.Y. Adjustment of food textural properties for elderly patients. Journal of Texture Studies. 2016;47(4):277–283. doi: 10.1111/jtxs.12200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cortez-Trejo M.C., Figueroa-Cárdenas J.D., Quintanar-Guerrero D., Baigts-Allende D.K., Manríquez J., Mendoza S. Effect of pH and protein-polysaccharide ratio on the intermolecular interactions between amaranth proteins and xanthan gum to produce electrostatic hydrogels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;129 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107648. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dick A., Bhandari B., Dong X., Prakash S. Feasibility study of hydrocolloid incorporated 3d printed pork as dysphagia food. Food Hydrocolloids. 2020;107:105940. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Su H., Chen G., Li X., Zhan C., Li Z., Li Y. Effects of pyruvate group on the gel properties of xanthan gum/konjac glucomannan complex system. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering (Transactions of the CSAE) 2021;37(3):287–293. doi: 10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2021.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Su H., Chen G., Li X., Zhang C., Li Z., Li Y. Effects of pyruvate group on the gel properties of xanthan gum_konjac glucomannan complex system. Transactions of the Chinese Society of Agricultural Engineering. 2021;37(3):287–293. doi: 10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2021.03.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile L. Protein–polysaccharide interactions and aggregates in food formulations. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2020;48:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2020.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadde E., Mossel B., Chen J., Prakash S. The safety and efficacy of xanthan gum-based thickeners and their effect in modifying bolus rheology in the therapeutic medical management of dysphagia. Food Hydrocolloids for Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.fhfh.2021.100038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan I., Gani A., Mudabir S. Development and characterization of 3d printed fish gelatin and vegetable blends as nutritious meal for dysphagic patients. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;157:110478. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2024.110478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Dai T., Sun J., Liang R., Liu W., Chen M., Chen J., Liu C. Effective change on rheology and structure properties of xanthan gum by industry-scale microfluidization treatment. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;124 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International-Dysphagia-Diet-Standardisation-Initiative Complete IDDSI framework. Detailed definitions 2.0: Licensed under the CreativeCommons Attribution Sharealike 4.0 License. 2019. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode

- Kool M.M., Gruppen H., Sworn G., Schols H.A. The influence of the six constituent xanthan repeating units on the order–disorder transition of xanthan. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2014;104:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.12.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A.C.Y., Can Karaca A., Tyler R.T., Nickerson M.T. Pea protein isolates: Structure, extraction, and functionality. Food Reviews International. 2018;34(2):126–147. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2016.1242135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le X.T., Turgeon S.L. Rheological and structural study of electrostatic cross-linked xanthan gum hydrogels induced by β-lactoglobulin. Soft Matter. 2013;9(11):3063–3073. doi: 10.1039/C3SM27528K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Feke D.L. Rheological and kinetic study of the ultrasonic degradation of xanthan gum in aqueous solution: Effects of pyruvate group. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015;124:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Bhandari B., Prakash S., Mantihal S., Zhang M. Linking rheology and printability of a multicomponent gel system of carrageenan-xanthan-starch in extrusion based additive manufacturing. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;87:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Bhandari B., Prakash S., Zhang M. Creation of internal structure of mashed potato construct by 3D printing and its textural properties. Food Research International. 2018;111:534–543. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.05.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Chen X., Dai Q., Xu D., Hu L., Li H., Hati S., Chitrakar B., Yao L., Mo H. Pea protein-xanthan gum interaction driving the development of 3D printed dysphagia diet. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;139 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Chen X., Li H., Chitrakar B., Zeng Y., Hu L., Mo H. 3D printing of nutritious dysphagia diet: Status and perspectives. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2024;147 doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2024.104478. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Zhang M., Yang C.-H. Dual extrusion 3D printing of mashed potatoes/strawberry juice gel. LWT. 2018;96:589–596. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z.B., Chen X., Dai Q.Y., Xu D., Hu L.B., Li H.B., Hati S., Chitrakar B., Yao L.S., Mo H.Z. Pea protein-xanthan gum interaction driving the development of 3D printed dysphagia diet. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;139 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Monzo J., Cardenas J., Garcia-Segovia P. Effect of Temperature on 3D Printing of Commercial Potato Puree. Food Biophysics. 2019;14(3):225–234. doi: 10.1007/s11483-019-09576-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClements D.J. Non-covalent interactions between proteins and polysaccharides. Biotechnology Advances. 2006;24(6):621–625. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pant A., Lee A.Y., Karyappa R., Lee C.P., An J., Hashimoto M., Tan U.X., Wong G., Chua C.K., Zhang Y. 3D food printing of fresh vegetables using food hydrocolloids for dysphagic patients. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;114 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106546. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao D., Luo M., Li Y., Jiang F., Zhang B. New evidence on synergistic binding effect of konjac glucomannan and xanthan with high pyruvate group content by atomic force microscopy. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;136 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108232. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao D., Luo M., Li Y., Jiang F., Zhang B., Xie F. Evolutions of synergistic binding between konjac glucomannan and xanthan with high pyruvate group content induced by monovalent and divalent cation concentration. Food Chemistry. 2024;432 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu L., Zhang M., Bhandari B., Chitrakar B., Chang L. Investigation of 3D printing of apple and edible rose blends as a dysphagia food. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;135 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori A.G.D.O., Saliba A.S.M.C., Bitencourt B.S., Guedes J.S., Torres L.C.R., Alencar S.M.D., Augusto P.E.D. Anthocyanin bioaccessibility and anti-inflammatory activity of a grape-based 3D printed food for dysphagia. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies. 2023;84 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2023.103289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith I.H., Symes K.C., Lawson C.J., Morris E.R. Influence of the pyruvate content of xanthan on macromolecular association in solution. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 1981;3(2):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(81)90078-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suebsaen K., Suksatit B., Kanha N., Laokuldilok T. Instrumental characterization of banana dessert gels for the elderly with dysphagia. Food Bioscience. 2019;32 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2019.100477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.D., Arntfield S.D. Molecular forces involved in heat-induced pea protein gelation: Effects of various reagents on the rheological properties of salt-extracted pea protein gels. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;28(2):325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.R., Yang Q., Li-Sha Y.J., Chen H.Q. Structural, gelation properties and microstructure of rice glutelin/sugar beet pectin composite gels: Effects of ionic strengths. Food Chemistry. 2020;346(5):128956. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2020.128956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Guo Y., Li R., Ma A., Zhang H. Rheological characterization of polysaccharide thickeners oriented for dysphagia management: Carboxymethylated curdlan, konjac glucomannan and their mixtures compared to xanthan gum. Food Hydrocolloids. 2021;110 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Qu J., Shen Y., Dai X., Wei W., Shi Z., Li G., Ma T. Gel properties of xanthan containing a single repeating unit with saturated pyruvate produced by an engineered Xanthomonas campestris CGMCC 15155. Food Hydrocolloids. 2019;87:747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Y.A., Al A., Dan L.A., Yga B., Ls C. Applications of mixed polysaccharide-protein systems in fabricating multi-structures of binary food gels—A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2021;109:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xing X., Chitrakar B., Hati S., Xie S., Li H., Li C., Liu Z., Mo H. Development of black fungus-based 3D printed foods as dysphagia diet: Effect of gums incorporation. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;123 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2021.107173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yabe K., Kudo T., Horiuchi I., et al. Pharyngeal Residues Following Swallowing of Pureed Diets Thickened with a Gelling Agent or a Xanthan Gum-Based Thickener in Elderly Patients with Dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s00455-024-10734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Li Y., Cao Z., Miao J., Feng J., Xi Q., Lu W. Structure–property relationship in the evaluation of xanthan gum functionality for oral suspensions and tablets. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2023;226:525–534. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J., Shu M., Yao X., Chen X., Li D., Yang D., Liu N., Nishinari K., Jiang F. Fibrillar assembly of whey protein isolate and gum Arabic as iron carrier for food fortification. Food Hydrocolloids. 2022;128 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Liang Z., Wang Z., Zhang P., Fang Z. Effect of natural colorants on the quality attributes of pea protein-based meat patties. Food Bioscience. 2024;59 doi: 10.1016/j.fbio.2024.103976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J., Cheng Y., Ouyang Z., Yang Y., Ma L., Wang H., Zhang Y. 3D printing surimi enhanced by surface crosslinking based on dry-spraying transglutaminase, and its application in dysphagia diets. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;140 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Εkonomou S.Ι., Hadnađev M., Gioxari A., Abosede O.R., Soe S., Stratakos A.C. Advancing dysphagia-oriented multi-ingredient meal development: Optimising hydrocolloid incorporation in 3D printed nutritious meals. Food Hydrocolloids. 2024;147 doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.109300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.