Abstract

Adoptive transfer of genetically or nanoparticle-engineered macrophages represents a promising cell therapy modality for treatment of solid tumor. However, the therapeutic efficacy is suboptimal without achieving a complete tumor regression, and the underlying mechanism remains elusive. Here, we discover a subpopulation of cancer cells with upregulated CD133 and programmed death-ligand 1 in mouse melanoma, resistant to the phagocytosis by the transferred macrophages. Compared to the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells express higher transforming growth factor-β signaling molecules to foster a resistant tumor niche, that restricts the trafficking of the transferred macrophages by stiffened extracellular matrix, and inhibits their cell-killing capability by immunosuppressive factors. The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells exhibit tumorigenic potential. The CD133+PD-L1+ cells are further identified in the clinically metastatic melanoma. Hyperthermia reverses the resistance of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells through upregulating the ‘eat me’ signal calreticulin, significantly improving the efficacy of adoptive macrophage therapy. Our findings demonstrate the mechanism of resistance to adoptive macrophage therapy, and provide a de novo strategy to counteract the resistance.

Subject terms: Nanoparticles, Cancer immunotherapy, Cell delivery

Adoptive transfer of genetically or nanoparticle-engineered macrophages has been exploited for cancer therapy. Here the authors report that a subset of cancer cells with upregulated expression of CD133 and programmed death-ligand 1 is associated with resistance to nanoparticle-engineered macrophage-based therapy in melanoma models.

Introduction

Adoptive cell therapy has emerged as an effective approach to cancer treatment, especially for hematologic malignancies1. The phenotypic plasticity, the actively tumor-penetrating capacity and the tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation of macrophages render them excellent candidates to combat solid malignancies2,3. Various genetic approaches have been developed to engineer macrophages with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR-MΦ) for adoptive macrophage therapy4–7. CAR-MΦ target their cognate antigen-expressing tumor cells, exerting the tumor antigen-dependent phagocytosis and antitumor activity2. Encouraging results from the first-in-human clinic trial of the adoptive anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) CAR-MΦ therapy have demonstrated the high transduction level, purity, and viability of the autologous macrophages without the dose-limited toxicity8,9. However, among the patients with HER2-positive recurrent or metastatic solid tumors receiving the CAR-MΦ therapy, the best overall response was stable disease only accounting for 28.6% of the patients (4 out of 14)8,10. These data indicate a suboptimal efficacy of the CAR-MΦ therapy.

The shift of the transferred macrophages from antitumor M1 (classically activated) to pro-tumoral M2 (alternatively activated) phenotypes in the TME is generally considered to be the major cause, which dampens the therapeutic efficacy2,11. Accordingly, versatile nanomaterials have recently been designed to tailor the macrophage phenotypes in vivo for enhancing the efficacy of adoptive macrophage therapy. The macrophages are engineered with cytokine-loaded nanoparticles such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) through a backpacking approach, to polarize themselves toward the M1 phenotype12. The macrophages backpacked with bacteria through adhesive nanocoatings are capable of controlling their antitumor phenotypes through durable stimulation13. Besides, the macrophages can be reprogramed for the M1 polarization by intracellular internalizing the inorganic nanoparticles, such as iron oxide and copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NPs)14–16. Unlike CAR-MΦ, the nanoparticle-engineered macrophages eliminate tumor cells in a tumor antigen-agnostic manner, offering a potential and universal approach to the adoptive macrophage therapy without CARs. Despite the effective inhibition of tumor growth through the transfer of the nanoparticle-engineered macrophages, a durable antitumor effect or complete tumor regression has not been achieved12,14,15. Our previous research has shown a significantly prolonged median survival time of mice bearing B16F10 melanoma after the transfer of CuS NPs-engineered macrophages (NPs-MΦ) once every 3 days for 3 times, i.e. one treatment cycle (NPs-MΦ1)14. However, the tumor progression occurred post treatment14.

Solid tumor consists of not only a heterogeneous population of tumor cells, but a TME collection of immune cells and stromal cells, secreted factors and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins as well17. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) as a major stromal component of the TME architecture account for the synthesis of ECM proteins and the production of immunosuppressive factors, subsequently promoting tumor growth and suppressing the antitumor immune responses18,19. Among the immunosuppressive factors, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) plays a central role in regulating the differentiation of CAFs and maintaining their functions20,21. TGF-β orchestrates the activities of other cells within TME for tumor progression and metastasis, including promotion of M2 macrophage polarization, differentiation of CD4+ T cells to a regulatory T (Treg) phenotype, and suppression of CD8+ T cells activation22,23. Moreover, recent reports have indicated cancer stem cells (CSCs) crosstalk with TME to establish a combinatorial loop among CSCs, TGF-β, and CAFs, contributing to the generation and maintenance of an immunosuppressive tumor niche for immune evasion and tumor relapse19,20,22,24. However, the interplay between CSCs and TME in the relapsed tumor following the adoptive macrophage therapy has not been elucidated.

Clinically, hyperthermia as an adjuvant therapy has been applied to cancer treatments in combination with radiotherapy and chemotherapy, particularly to superficial tumors25,26. Adjuvant hyperthermia with radiotherapy significantly enhances the therapeutic efficacy in patients with recurrent or metastatic melanoma26,27. The mechanism involves the induction of apoptotic responses of tumor cells, activation of the immune system, and transformation from the immunosuppressive TME to the immunogenic TME28,29. In addition, hyperthermia has been reported as a promising approach to eliminating therapy-resistant CSCs30.

In this work, we hypothesize that CSCs or cancer cells with some stem-like features foster a tumor niche following the adoptive macrophage transfer, responsible for the resistance through the enhanced physical and biological barriers to prohibit the effector cells from tumor elimination. By analyzing the TME of the recurrent tumor in mouse B16F10 and human A375 melanoma models, we identify a subpopulation of cancer cells upregulating CD133 and the programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, named CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells. The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells are inherently resistant to the phagocytosis by NPs-MΦ, and remodel the TME including CAFs activation and ECM stiffening through the TGF-β signaling pathway to drive the tumor resistance and relapse. The tumor niche generated by the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells inhibits the trafficking and phagocytosis ability of the adoptively transferred macrophages as well as the tumor cell-killing capacity of CD8+ T cells. Moreover, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells exhibit some stem-like features including tumorigenic potential and exhibit resistance to the combinatorial therapy of adoptive macrophages and the PD-L1 blockade. An adjuvant hyperthermia reverses the resistance of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells to the adoptive macrophages, thus improving the efficacy of adoptive macrophage therapy.

Results

Stiffened tumor ECM restricts the trafficking of transferred macrophages

In this study, the adoptive NPs-MΦ were prepared by incubating the mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) with CuS-NPs. The phagocytized nanoparticles elevated the intracellular production of the reactive oxygen species (ROS) by slow release of Cu ions and induced the M1 polarization through the classical IKK-dependent NF-κB activation (Fig. 1a)14. To investigate if extension of the treatment cycle of NPs-MΦ could completely inhibit the tumor growth, we adjusted the therapeutic regimen of NPs-MΦ to three treatment cycles (NPs-MΦ3) (Fig. 1b). The transfer of NPs-MΦ3 elongated the survival times of the B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice (Supplementary Table 1). However, the tumor still exhibited a recurrence. This result illustrated that increasing the repetition of the NPs-MΦ therapy was not able to overcome the tumor relapse or progression. Bulk transcriptome RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq) analysis of the tumor samples following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 35 revealed an upregulation of genes Col4a1 and Col9a2 associated with the tumor ECM compared with that before the treatment at day 8 or after the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days 16, respectively (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 1). Besides, a significantly increased expression of immunosuppressive genes Vegfa and Tgfa was observed in the relapsed tumor at day 35 than the other two groups. The stiffened ECM of the relapsed tumor was validated by BioAFM analysis (Fig. 1d, e). The enhanced stiffness of tumor ECM correlated well with the increase in the CAFs characterized by the myofibroblast marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), as well as the main ECM components collagen IV and collagen II (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Fig. 2). Moreover, the TGF-β level was significantly upregulated in the relapsed tumor after the macrophage transfer at day 35 (Fig. 1g), showing a positive correlation with the increased CAFs and the stiffened ECM (Fig. 1c–f). Compared with the tumor of mice following the NPs-MΦ treatment at day 14, the infiltration of various types of immune cells was significantly reduced in the tumor at day 23 (Supplementary Fig. 3a). This result demonstrated the inhibited antitumor functions of CD8+ T cells in the tumor relapse stage.

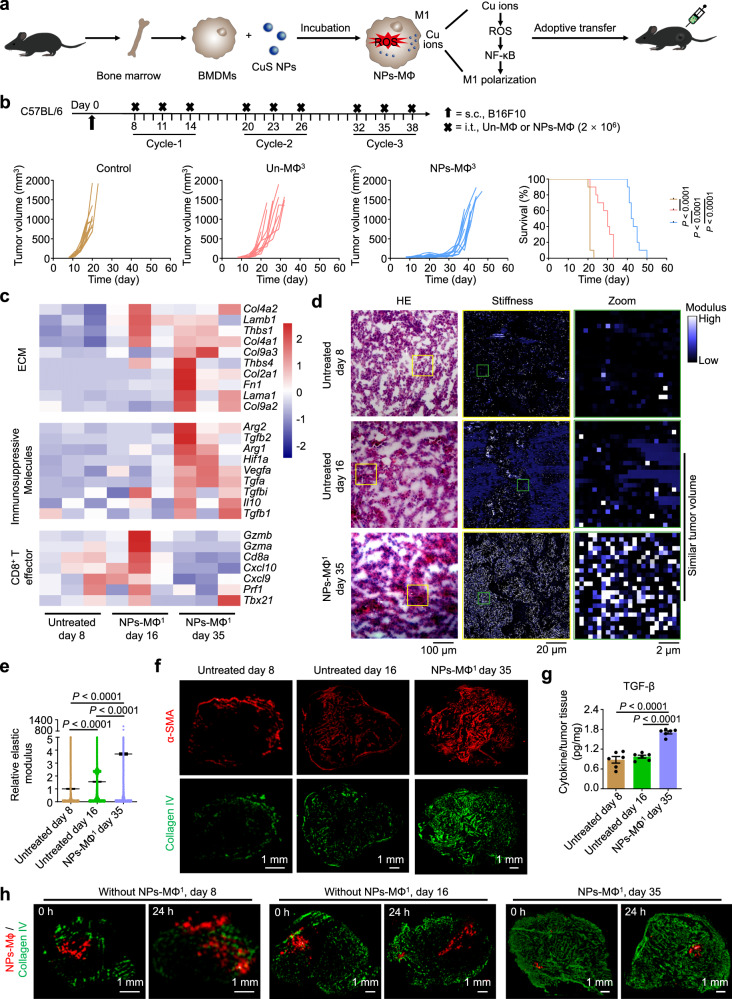

Fig. 1. Stiffened tumor ECM restricts the trafficking of transferred macrophages.

a Schematic illustration of the preparation of NPs-MΦ and the mechanism of CuS NPs-induced M1 polarization. b Three treatment cycles of the adoptive macrophage transfer therapy with Un-MΦ (Un-MΦ3) or NPs-MΦ (NPs-MΦ3) in the B16F10 bearing C57BL/6 mice. Upper, the treatment regimens. Lower, individual tumor growth curves and the corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves, log-rank analysis (n = 10 mice). Control, mice without treatment. c Heatmaps of the cluster of genes associated with the ECM, the key immunosuppressive molecules or the CD8+ T effector cells in the B16F10 tumor of C57BL/6 mice before the treatment at day 8, or after 1 cycle-treatment (NPs-MΦ1) at days 16 or 35 (n = 3 mice). d, e Images of haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and force maps of the ECM stiffness (d), and the corresponding quantification of relative modulus measured using bio-atomic force microscopy (BioAFM) indentation (e). Tumors were collected from the NPs-MΦ1-treated mice at day 35. Mice before the treatment at day 8 or without treatment at day 16 were used as controls. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 65536 biologically independent recorded points). f Expression of α-SMA and collagen IV in the tumor tissues following different treatments. Image shown is representative of n = 3 independent replicates of experiments with similar results. g Quantification of TGF-β in the tumor of mice by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 6 mice). h Fluorescence images of the injected DiD-labeled NPs-MΦ (red) and the immuno-stained collagen IV (green) in tumor sections. Samples were collected at 0 h or 24 h post-administration. The DiD-labeled NPs-MΦ were i.t. injected in the tumor of mice following NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 35 (NPs-MΦ1, day 35), or the tumors of mice without NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days 8 (Without NPs-MΦ1, day 8) or 16 (Without NPs-MΦ1, day 16). The image shown is representative of n = 3 independent replicates of experiments with similar results. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To track the intratumoral (i.t.) distribution of the injected NPs-MΦ following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment, the cells were labeled with the cell-tracker dioctadecyl-tetramethylindodicarbocyanine (DiD). Compared with the tumor of mice without the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days 8 or 16, dense collagen fibers appeared throughout the tumor of mice receiving NPs-MΦ1 at day 35, restricting the diffusion of the injected DiD-labeled NPs-MΦ (Fig. 1h, Supplementary Fig. 3b). The enlarged fluorescence micrographs showed that the injected NPs-MΦ were surrounded by the collagen network (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Together, the tumor relapse after the NPs-MΦ transfer exhibited an immunosuppressive TME with a stiffened ECM characteristic, leading to the restricted trafficking of the transferred macrophages in the tumor, limited tumor infiltration of immune cells and compromised the effector cell function.

CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells inhibit adoptive macrophages by TGF-β signaling pathway

The crosstalk between CAFs and the tumor cells was evaluated in a co-culture of mouse embryonic fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 and B16F10 in the presence of TGF-β. TGF-β increased the PD-L1 expression in both cell lines following the co-culture (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, an increase in the ratio of NIH3T3 to B16F10 cells elevated the PD-L1 expression in B16F10 cells, and vice versa (Fig. 2a, blue columns). This result supported that the fibroblasts and tumor cells promote the PD-L1 expression in each other in the presence of TGF-β. A higher PD-L1 expression in both tumor cells and CAFs in the relapsed tumor of mice after the NPs-MΦ1 treatment was induced at day 35 compared with the control groups without the NPs-MΦ1 treatment (Fig. 2b). An increase in the PD-L1 expression in the relapsed tumor after the NPs-MΦ transfer was indicative of a critical signal of ‘self’ to macrophages and T cells for the resistance31,32.

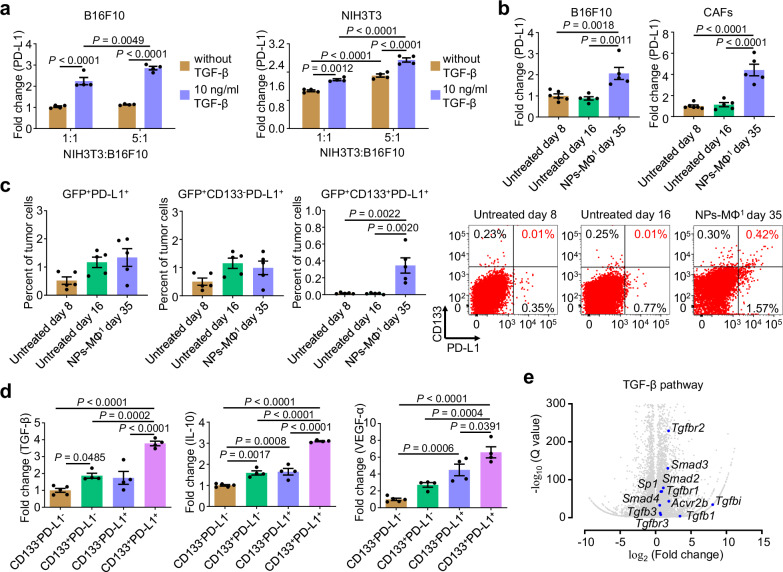

Fig. 2. Identification of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells with upregulated TGF-β signaling pathway following the NPs-MΦ transfer therapy.

a Expression of PD-L1 in B16F10 cancer cells or NIH3T3 fibroblast cells in the co-culture with or without TGF-β. The expression of PD-L1 was normalized with the corresponding untreated B16F10 or NIH3T3 cells cultured alone. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 4 biologically independent samples). b Expression of PD-L1 in the cancer cells and CAFs of mice following different treatments, normalized with the group of untreated day 8. Untreated day 16, the mice without treatment at day 16 reached a similar tumor size in volume ( ~ 500 mm3) to that of mice following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 35. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 6 biologically independent samples for untreated day 8, n = 5 biologically independent samples for untreated day 16 or NPs-MΦ1 day 35). c Identification of CD133+PD-L1+ from the B16-GFP cancer cells of mice receiving the adoptive NPs-MΦ therapy. Tumors were collected from the NPs-MΦ1-treated mice at day 35. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 5 biologically independent mice). Right, representative dot plots of the flow cytometric analysis. d Flow cytometric analysis of TGF-β, IL-10 or VEGF-α production in GFP+CD133-PD-L1-, GFP+CD133+PD-L1-, GFP+CD133-PD-L1+ and GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells of mice following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 35, respectively. The expression of TGF-β, IL-10, or VEGF-α were normalized with the corresponding GFP+CD133+PD-L1- cancer cells. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 5 biologically independent samples for GFP+CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells, n = 4 biologically independent samples for GFP+CD133+PD-L1-, GFP+CD133-PD-L1+ or GFP+CD133+ PD-L1+ cancer cells). e Volcano plot indicating differentially expressed genes relevant to the TGF-β pathway. The x-axis indicates the log2-fold change for GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ versus GFP+CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells. The y-axis indicates the −1 × log10 of the Q value. Statistical significance was calculated using the two-sided Wald test for DESeq2 data. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our results demonstrated that the CD133+ mouse B16F10 and the CD133+ human A375 melanoma cell lines accounted for about 0.82% and 0.01% of the melanoma bulk population cells, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Besides CD133, CD271, and ABCG2 have also been reported to exhibit stemness traits in melanoma33–35. Herein, we performed the coexpression analysis in the recurrent B16F10 melanoma samples. Approximately 80.28% and 81.94% of CD133+ melanoma cells co-expressed CD271 and ABCG2, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4b), suggesting that the majority of CD133+ recurrent melanoma cells exhibited the biologic functions of CD271 and ABCG2. To further verify whether the CD133+ cancer cells possess some stem-like function, we sorted CD133+ and CD133- B16F10 cancer cells by flow cytometry, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5a). In clonogenic assays, the CD133+ cancer cells were observed to form significantly larger colonies than CD133- cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 5b). In the self-renewal assays, the sizes of primary tumorspheres from the CD133+ cancer cells were significantly larger than those from the CD133- cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c, upper). Furthermore, we passaged the single cells derived from the primary spheres to culture the secondary tumorspheres. The sizes of the secondary tumorspheres from of the CD133+ cancer cells were also significantly bigger than those from the CD133- cancer cells (Supplementary Fig. 5c, lower). To evaluate the tumor initiation in vivo, the sorted CD133+ and CD133- B16F10 cancer cells were subcutaneously (s.c.) injected into the left flank of C57BL/6 mice, respectively. The mice injected with the CD133- cancer cells did not generate palpable tumor at the injection dose of 1 × 103, 5 × 103 or 1 × 104 tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. 5d). By contrast, the tumor growth was observed in the mice injected with the CD133+ cancer cells at the dose of 5 × 103 or 1 × 104 tumor cells. The growth of tumor was confirmed by the tumor weight and photographs following the resection (Supplementary Fig. 5e, f). The expression of CSC marker Sox2 was significantly higher in the CD133+ cancer cells compared to that in the CD133- cancer cells, while the other two markers Nanog and Oct4 were not significantly changed (Supplementary Fig. 5g). In addition, the gene profiles of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) signatures such as Zeb2, Cdh2 and Vim were significantly increased in the CD133+ cancer cells than the CD133- cancer cells, while Snai1, Snai2, Zeb1, Cdh1 and Fn1 were not significantly changed (Supplementary Fig. 5h). In summary, these results demonstrated that the CD133+ cancer cells expressed some CSC markers, and presented some stem-like functions including self-renewal capacity and tumorigenic potential.

Since the upregulation of PD-L1 expression in the tumor cells following the NPs-MΦ transfer therapy, a subpopulation of CD133+ cancer cells with a significantly high level of PD-L1 expression i.e. CD133+PD-L1+ was identified, accounting for approximately 0.35% of the tumor cells in the relapsed tumor (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 6). The immunosuppressive cytokines in the tumor cells of the relapsed tumor were further analyzed by flow cytometry. Because of the melanoma cells with constitutively low expression of PD-L136,37, the tumor cells here were designated as the PD-L1- cancer cells. The intracellular TGF-β level of the CD133+PD-L1- cancer cells was about 1.87-fold of that of the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells. Remarkably, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells potentiated the intracellular TGF-β by approximately 3.78-fold in comparison with the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells (Fig. 2d, left). The intracellular IL-10 and VEGF-α levels of the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells were also increased by approximately 3.10-fold and 6.58-fold compared with those of the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells, respectively (Fig. 2d, middle and right).

To better understand the role of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells in the melanoma progression, we sorted both CD133+PD-L1+ and CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells from the relapsed tumor at day 35 following the NPs-MΦ transfer for bulk RNA-seq, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7a, b). Gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis demonstrated that the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells participated in a variety of biological processes such as defense response, immune response, regulation of response to stimulus, as well as diverse molecular functions such as Rac/Rho guanyl-nucleotide exchange factor activity (Supplementary Fig. 7c). Specifically, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells exhibited a high TGF-β pathway activity (Fig. 2e) and promoted the immunosuppressive molecules including Tgfb1, Il10 and Vegfα, and the proto-oncogenes such as Met, Frat1 and Fos (Supplementary Fig. 7d, e). For the in vitro analysis, the CD133+ cancer cells were induced by incubating B16F10 cells with gemcitabine38. The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells were obtained by further induction with IFN-γ followed by purification (Supplementary Fig. 8a–c). Consistent with the in vivo results, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells expressed the highest intracellular levels of TGF-β, IL-10 and VEGF-α among the four phenotypes of the tumor cells gated by CD133 and PD-L1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 8d). For the characterization in vivo, we classified the B16-GFP melanoma into 3 stages after the NPs-MΦ1 therapy based on the tumor volume, i.e. an early stage with 100–250 mm3, a middle stage with 500–1000 mm3, and a late stage with 1500–1800 mm3. No significant differences were observed in the distribution of CD133+PD-L1- or CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells numbers across various stages of tumor (Fig. 3a). The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells exhibited higher TGF-β level than CD133+PD-L1- cancer cells across all the stages of tumor (Fig. 3b, left). The intracellular TGF-β level correlated well with the increased in the tumor volume in both CD133+PD-L1- and CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cell population (Fig. 3b, right).

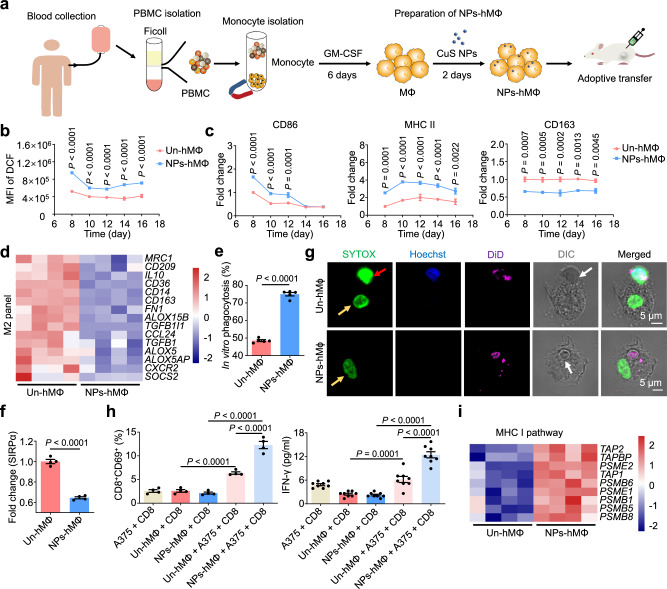

Fig. 3. CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells inhibit adoptive macrophages by TGF-β signaling pathway.

a The percentage of GFP+CD133+PD-L1- or GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells in different stages of tumor of mice following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 6 mice). b The TGF-β level in GFP+CD133+PD-L1- or GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 6 mice). Right, the corresponding correlation between the tumor volume and the TGF-β level in GFP+CD133+PD-L1- or GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells. The TGF-β level was normalized with that in the GFP+CD133+PD-L1- cancer cells of tumor in the early stage (left). An exponential growth fit curve is shown. Two-tailed Spearman correlation was used to evaluate the association (n = 18 mice). In (a) and (b), mice with tumor volume of 100–250 mm3 (early stage), 500–1000 mm3 (middle stage) or 1500–1800 mm3 (late stage) were included. c In vitro phagocytosis assay quantified by flow cytometry. Left, the four phenotypes of cancer cells as the target cells, and the NPs-MΦ as the effector cells (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Right, the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells as the target cells, and the NPs-MΦ pretreated with IL-10, VEGF-α, TGF-β or the combination overnight before the phagocytosis assay as the effector cells (n = 6 biologically independent samples). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test. d The percentage of tumor cell lysis by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Left, the four phenotypes of tumor cells as the target cells. Right, the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells were the target cells, and the coincubation was conducted in the presence of IL-10, VEGF-α, TGF-β or the combination. The data of tumor lysis was normalized with the control without the addition of the effector cells. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 5 biologically independent samples). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The data of functional analysis showed that in contrast to the approximately 52.85% of the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells phagocytosed by NPs-MΦ only around 11.45% of the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells were internalized (Fig. 3c, left). Furthermore, the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells appeared resistant to the phagocytosis by NPs-MΦ in the presence of the immunosuppressive factors TGF-β, IL-10, or VEGF-α (Fig. 3c, right). Notably, the combo treatment with these three factors resulted in only approximately 8.70% of the cancer cells being phagocytized. Similarly, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells exhibited more resistance to the lysis by the stimulated splenocytes in comparison with the CD133-PD-L1- cancer cells (Fig. 3d, left). The presence of TGF-β, IL-10, and VEGF-α further prevented the tumor cells from lysis (Fig. 3d, right). To assess the tumor generation capability of the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells, we induced and sorted the CD133+PD-L1+, CD133+PD-L1-, CD133-PD-L1+ and CD133-PD-L1- B16F10 cancer cells in vitro, respectively. Each subpopulation was s.c. injected into the left flank of mice. The results demonstrated that the tumor grew the fastest in the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells groups among all the four groups, resulting in the highest tumor weights at day 24 post-tumor cell inoculation (Supplementary Fig. 9). These data collectively demonstrated that the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells overexpressed the immunosuppressive factors resistant to both the NPs-MΦ and the effector splenocytes through the TGF-β signaling pathway.

TGF-β-enriched and stiffened TME impedes adoptive human macrophages activity

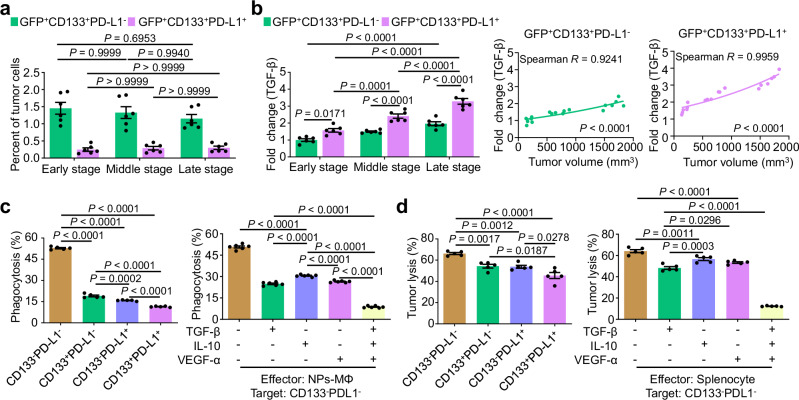

We next investigated the antitumoral effect of CuS NPs-engineered human macrophages (NPs-hMΦ) on a human A375 melanoma xenograft mouse model. NPs-hMΦ were prepared by primarily culturing peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes of healthy donors with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) for 6 days, followed by incubation with CuS NPs for 2 days (Fig. 4a). Compared to the human macrophages without CuS NPs (Un-hMΦ), the NPs-hMΦ exhibited a significant increase in the intracellular ROS level over time, accompanied by the elevation of the M1 phenotypic markers CD86 and MHC II, and the reduction of the alternatively activated M2 marker CD163 (Fig. 4b, c). The M1 polarization of NPs-hMΦ was also confirmed by the down-regulated expression of the M2-related genes (Fig. 4d). NPs-hMΦ displayed significantly enhanced phagocytic activity of the live A375 cancer cells than Un-hMΦ in vitro, likely through the decreased expression of signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) (Fig. 4e, f). In addition, in an assay of the live cancer cell digestion, the cancer cells phagocytized by the Un-hMΦ exhibited relatively round nuclei and intact cell membranes. By contrast, the undetected cancer cell nuclei and fragmented cell membrane was observed in the NPs-hMΦ (Fig. 4g).

Fig. 4. The engineered human macrophages enhance M1 polarization and CD8+ T cell activation.

a Scheme for the preparation of CuS NPs engineered human macrophage (NPs-hMΦ). b Intracellular ROS level in human macrophages over time were measured by flow cytometry. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 4 biologically independent samples). c Cellular expression of CD86, MHC II (HLA-DR) or CD163 measured by flow cytometry, normalized with the corresponding Un-hMΦ. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 4 biologically independent samples for MHC II, n = 3 biologically independent samples of Un-hMΦ, and n = 4 biologically independent samples of NP-hMΦ for CD86 or CD163). d Heatmaps of the genes associated with the M2-releated markers in NPs-hMΦ compared to Un-hMΦ (n = 4 biologically independent samples). e In vitro phagocytosis of human melanoma cells by NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 5 biologically independent samples). f Expression of SIRPα in NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ at day 8, normalized with that in Un-hMΦ. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 4 biologically independent samples). g Digestion of the phagocytized A375 cancer cells by NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ. The macrophages were cocultured with the Hoechst 33342 (nucleus, blue) and DiD (membrane, magenta) dual-labeled A375 cells at a 1:2 ratio for 1 h. After 2 h, cells were fixed and counterstained with SYTOX (nuclei, green). Red arrow, nucleus of phagocytized cancer cells; yellow arrows, nuclei of the macrophages; white arrows, differential interference contrast (DIC) images of the phagocytized cancer cells. Image shown is representative of n = 3 independent replicates of experiments with similar results. h The activation of CD8+ T cells by NPs-hMΦ measured by CD69 expression and IFN-γ secretion. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 4 biologically independent samples for CD69 expression, and n = 8 biologically independent samples for IFN-γ secretion). i Heatmaps of genes associated with the MHC I pathway in NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ (n = 4 biologically independent samples). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

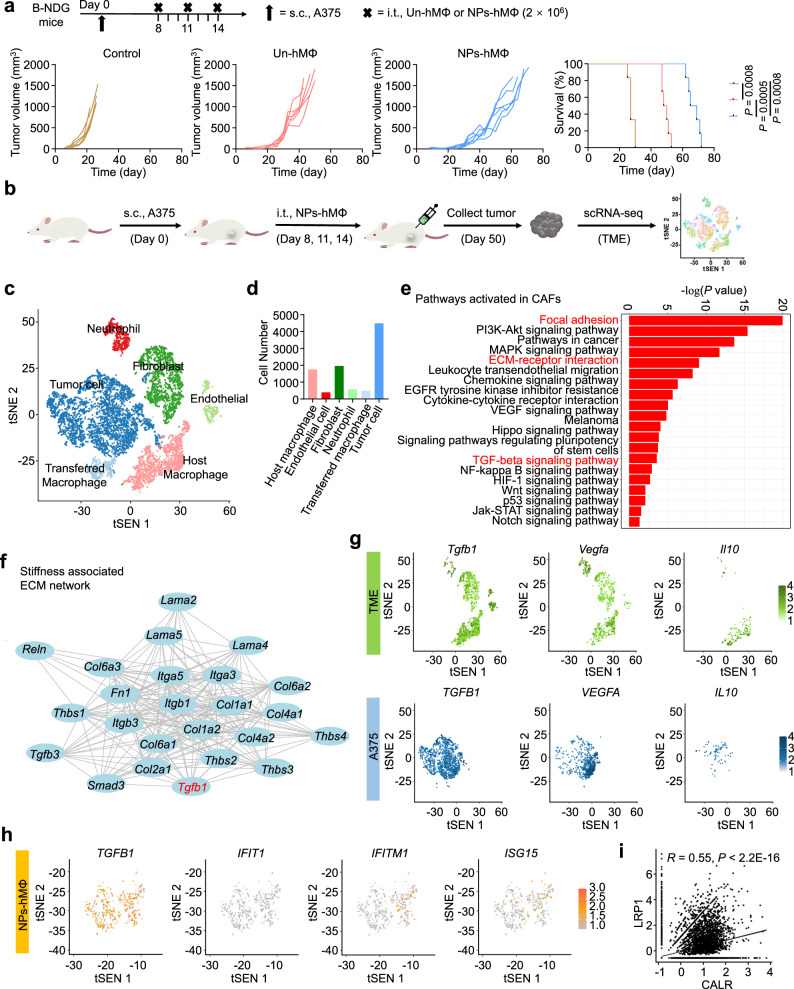

Macrophages are recognized as professional antigen-presenting cells capable of cross-presenting phagocytized tumor antigens via MHC I to activate CD8+ T cells2,39. To test such capability, both CD14+ monocytes and CD8+ T cells were collected from the same healthy donor. NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ prepared from the CD14+ monocytes were co-incubated with A375 cancer cells for 24 h to allow the phagocytosis of the cancer cells and the tumor antigen processing. Then, these macrophages were co-cultured with the HLA-matched CD8+ T cells, enabling the cross-presentation of tumor antigens to prime CD8+ T cell activation. The results showed a significantly higher amount of the activated CD8+ T cells in presence with the NPs-hMΦ and A375 cancer cells, evidenced by the increased CD69 and IFN-γ expression than that in the A375-phagocytized Un-hMΦ (Fig. 4h). This was in line with the upregulation of genes associated with the MHC I antigen presentation pathway in the NPs-hMΦ (Fig. 4i). Moreover, the B-NDG mice bearing human A375 melanoma were used to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy following one treatment cycle of the adoptive transfer of human macrophages. The results showed that the NPs-hMΦ significantly reduced tumor burden and prolonged the medium survival time of mice in comparison with the Un-hMΦ, i.e. 67 days for NPs-hMΦ versus 49 days for Un-hMΦ. However, following the initial tumor suppression, tumor relapse occurred in all the treatment groups (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 5. The stiffened TME dampens the antitumor activity of the adoptive human macrophages via activation of TGF-β.

a Adoptive transfer of NPs-hMΦ therapy in the A375-bearing B-NDG mice. Upper, the treatment regimens. Lower, individual tumor growth curves and the corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves, log-rank analysis (n = 6 mice). Control, without treatment. b scRNA-seq experiment workflow and data analysis of single cell suspension from six whole human A375 melanoma tissues. c The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) projection of the complete atlas of the whole A375 tumor tissue. Each dot represents a cell colored and labeled by the inferred cell types (n = 9650 of total single cells). d Numbers of each type of cells in the whole A375 tumor of B-NDG model. e Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) enrichment of the significantly activated pathways in the CAFs, cultivating a pro-tumorigenic niche. Comparison was performed between CAFs (n = 1955 cells) and other mouse-derived cell types (n = 2725 cells) in the tumor. f ECM string network associated with tumor stiffness, showing the accumulation of collagen regulated by TGF-β. Lines represent associations between the proteins. g tSNE plots of the expression of the immunosuppressive TGF-β, VEGF-α and IL-10 molecules in TME and A375 cancer cells, respectively. n = 4680 of TME cells, including mouse-derived neutrophils, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and macrophages. n = 4485 of A375 cancer cells. h tSNE plots of the indicated M1 and M2-associated genes in the remaining NPs-hMΦ. n = 485 of the transferred NPs-hMΦ. i Correlation analysis of the phagocytosis checkpoint pair between calreticulin (CALR) in the cancer cells and low lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) in the remaining NPs-hMΦ. Two-tailed Pearson correlation test. n = 4485 of A375 cancer cells. n = 485 of the transferred NPs-hMΦ. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We further assessed whether the tumor relapse after transfer of NPs-hMΦ would exhibit similar resistance mechanisms to that observed in the mouse B16F10 tumor following adoptive transfer of mouse macrophages. The relapsed A375 tumors were collected at day 50 for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to profile the whole TME composition and function (Fig. 5b). The t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots clustering revealed the whole tumor was categorized into 6 cell types based on the marker genes, including the mouse-derived neutrophils, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and macrophages (host cells), as well as human-derived transferred macrophages and tumor cells (Fig. 5c, Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). Quantitative analysis showed human tumor cells and the transferred NPs-hMΦ accounted for about 46.48% and approximately 5.03% of the total cells in the tumor bulk, respectively (Fig. 5d). Cascades regarding the focal adhesion (P < 0.0001), the ECM-receptor interaction (P < 0.0001) and the TGF-β signaling pathway (P = 0.0002) were significantly activated in the CAFs of the TME (Fig. 5e). Pathway enrichment in the focal adhesion mediated the attachment of TME cells to the ECM proteins, regulating the cell migration and signal transduction. The cell-ECM adhesions were particularly enhanced with elevated ECM rigidity40. The induction of pathways such as PI3K-Akt, VEGF, HIF-1, Hippo, Notch together with TGF-β in CAFs represented the TME functionally skewed toward the immunosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic state (Fig. 5e). The increase in these pathways was also observed in the tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in the relapsed tumor, indicating that TAMs adopted a pro-tumoral phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 10c). The stiffened tumor was associated with the increased production of the ECM molecules such as the collagen family. The crosstalk among the ECM molecules was regulated by TGF-β (Fig. 5f). Consistent with the bulk RNA-seq in the B16F10 model, the abundant expression of immunosuppressive factors TGF-β, VEGF-α and IL-10 in both the TME components and the tumor cells were detected in the relapsed A375 tumor following the therapy (Fig. 5g).

Little transferred NPs-hMΦ survived in the relapsed tumor was evidenced by the activation of pathway associated with apoptosis and necroptosis (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 11a). The polarization analysis illustrated that the activation of not only the M1-related TNF signaling, NF-κB signaling and NOD-like receptor signaling, but also the stimulation of M2-related HIF-1 signaling in the remaining NPs-hMΦ (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Specifically, the tSNE plots revealed a significantly elevated expression of the M2 pro-tumoral gene TGFB1 in the majority of NPs-hMΦ. Whereas, only a small number of NPs-hMΦ maintained high levels of the M1-associated interferon response genes such as IFIT1, IFITM1 and ISG15 (Fig. 5h, Supplementary Fig. 11b). Furthermore, the crosstalk between the effector NPs-hMΦ and the target tumor cells was analyzed by the ligand-receptor pairs with gene functional enrichment. The data showed the interaction was mainly related to tumor phagocytosis and immune response (Supplementary Fig. 11c). Specifically, the scatter plots of the phagocytosis checkpoints in the remaining NPs-hMΦ revealed a stronger correlation between the ‘eat me’ signal of the calreticulin (CALR)-low lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) pair than that between the ‘don’t eat me’ signal of the CD47-SIPRα pair. However, such correlation was relatively low, with an R-value of ‘eat me’ signal to 0.55 (Fig. 5i, Supplementary Fig. 11d–f). These findings collectively supported the compromised antitumor capacity of the remaining NPs-hMΦ.

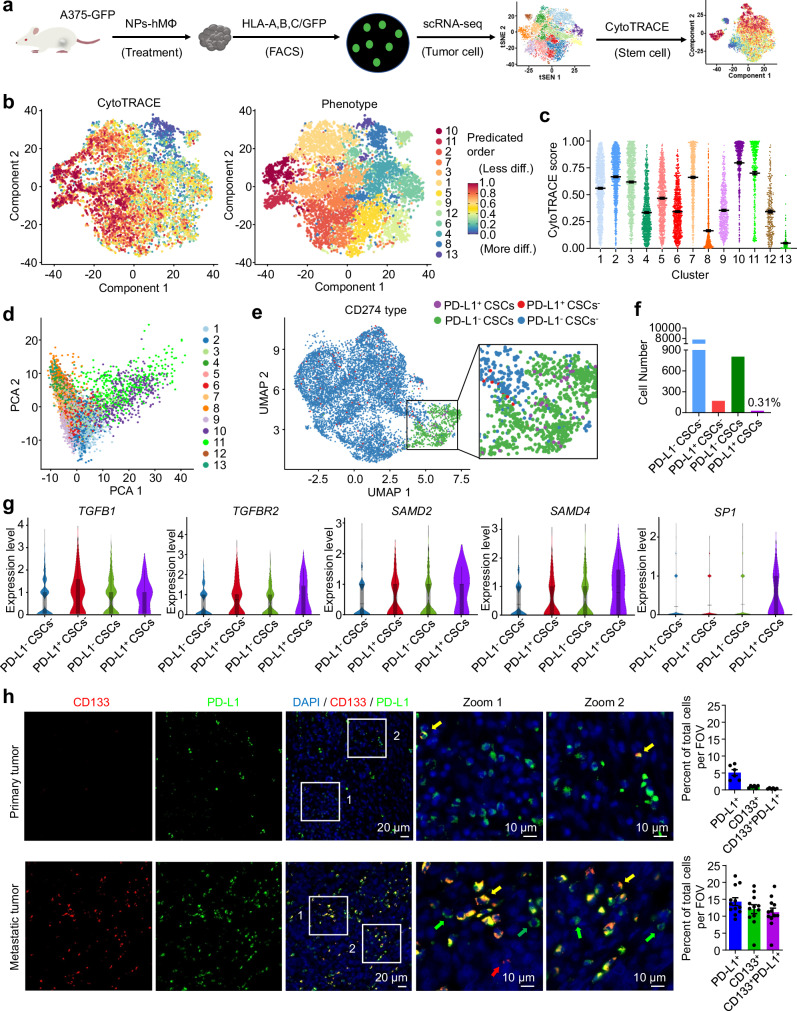

Human PD-L1+ CSCs exhibit activated TGF-β signaling pathway

CytoTRACE analysis, an unsupervised inference method to analyze the tissue stem cells based on the differentiation state41,42, was applied to assess whether a CSCs population was developed in the relapsed tumor after the NPs-hMΦ transfer. The tumor tissues were first selected by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich the human-derived cells based on the signals of human HLA-A,B,C and GFP expression, and then used for scRNA-seq analysis (Fig. 6a). We observed the clusters 10 and 11 attained with the highest two CytoTRACE scores among all the clusters (Fig. 6b, c). The two clusters of cells represented the lowest differentiation state and the highest degree of stemness, which can be classified into the CSC populations in tumors41,42. In addition, we performed the principal component analysis of the clusters, and the results supported that clusters 10 and 11 were positioned in close proximity to each other, but separated from the other clusters (Fig. 6d). We then consolidated clusters 10 and 11 into one population. Among this CSCs population in the relapsed A375 tumors, a subpopulation of the CSCs with high PD-L1 expression was further identified by the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots (Fig. 6e, purple dots). This subpopulation of CSCs was denoted as PD-L1+ CSCs, accounting for about 0.31% of the tumor cells (Fig. 6f).

Fig. 6. Identification of human PD-L1+ CSCs with activated TGF-β signaling pathway.

a scRNA-seq experiment workflow for analysis of human A375 melanoma cells sorted from 5 tumors of mice. b Heatmap for CytoTRACE scores of the scRNA-seq data overlaid on the tSNE map. c Scatter plots of CytoTRACE score in each cluster from a total of 9065 human-derived single cells. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. d Principal component analysis of gene expression of the thirteen clusters based on the scRNA-seq data. e Categorization of A375 cancer cells into the four subpopulations by tumor stemness and the PD-L1 expression, PD-L1- CSCs, PD-L1+ CSCs, PD-L1- CSCs- and PD-L1+ CSCs- cancer cells (n = 8790 cells). f Numbers of the corresponding four cancer cell subtypes in the whole A375 cancer cell dataset. g Violin plots of signature genes associated with TGF-β pathway across the four cancer subpopulations. n = 7788 of PD-L1- CSCs-, n = 170 of PD-L1+ CSCs- cancer cells, n = 805 of PD-L1- CSCs, n = 27 of PD-L1+ CSCs. Box center line, median; box limits, upper and lower quartiles; whiskers, 1.5× interquartile range. h Representative immunofluorescence micrographs of the expression of CD133 (red) and PD-L1 (green) in primary or metastatic tumor of human melanoma specimens. Blue, cell nuclei. Right, the number of CD133+, PD-L1+ or CD133+PD-L1+ cells within the field of view (FOV) was analyzed by Fiji ImageJ software. Data are presented from 2 primary melanoma specimens and 4 metastatic melanoma specimens. Three FOVs from each sample were selected for the analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Yellow arrow, CD133+PD-L1+ cells; green arrows, CD133-PD-L1+ cells; red arrows, CD133+PD-L1- cells. The individual fluorescence micrographs of each specimen were presented in Supplementary Fig. 12. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Violin plots revealed the comprehensive upregulation of key mediators of TGFB1, TGFBR2, SAMD2 and SAMD4 in charge of the TGF-β signaling pathway in PD-L1+ CSCs. Notably, SP1, a transcription factor cooperated with Smad complexes to promote the activity of TGF-β pathway43,44, was prominently expressed in PD-L1+ CSCs, while it was scarcely found in the other three phenotypes (Fig. 6g). In addition, we analyzed clinical human melanoma specimens. As shown in Supplementary Table 3, all the six clinical melanoma specimens were classified as high-grade tumors. Among them, specimens #1 and #2 were primary tumors at an early stage before treatment in the pre-relapse conditions. In these samples, a population of PD-L1+ cells but with CD133-negative staining were observed (Fig. 6h, upper row, green arrows, Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). Only a few CD133+PD-L1+ cells were detected (Fig. 6h, upper row, yellow arrows, Supplementary Fig. 12a, b). The specimens #3-#6 were metastatic tumors at late stage after receiving various treatments in the post-relapse conditions. Compared to specimens #1 and #2, the CD133+PD-L1+ cells in the tumor of specimens #3-#6 were significantly increased (Fig. 6h, lower row, yellow arrows, Supplementary Fig. 12c–f), indicating that the CD133+PD-L1+ cells were increased in the metastatic melanoma.

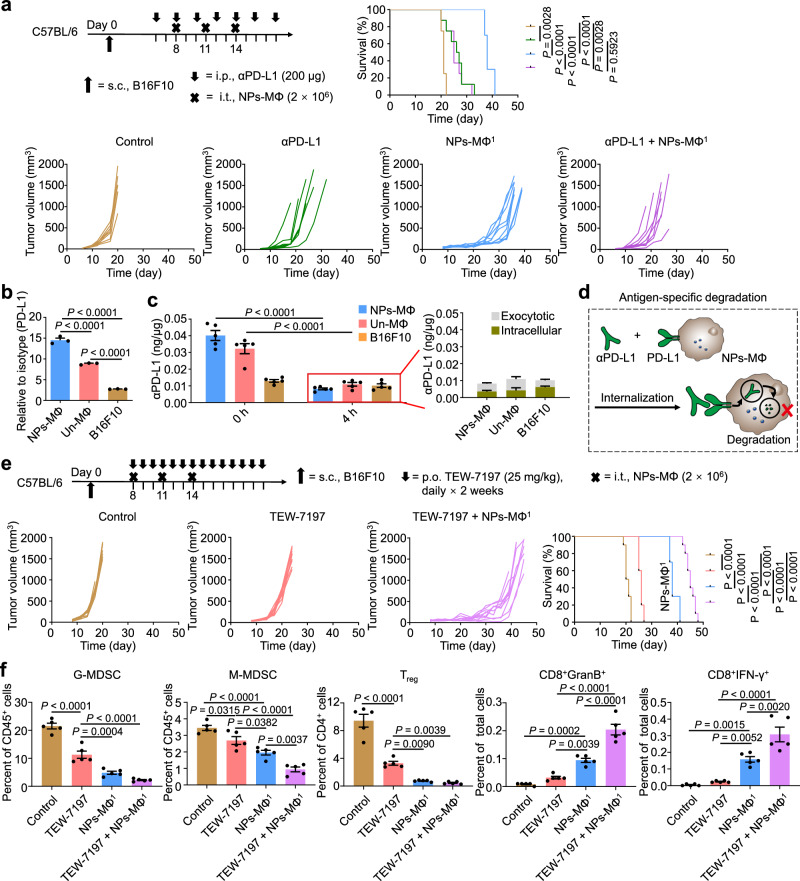

TGF-β inhibitor but not PD-L1 blockade improves the adoptive macrophage therapy

Based on the above findings of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells and the upregulation of PD-L1 in the relapsed tumor following the transfer of NPs-MΦ, we combined the adoptive NPs-MΦ1 therapy with anti-PD-L1 antibody (αPD-L1) to evaluate if the synergistic antitumor effect was obtained. The medium survival time of the mice receiving NPs-MΦ1 plus the PD-L1 blockade was not improved in comparison with that treated with the αPD-L1 alone (25 days versus 26.5 days), and significantly shorter than that with NPs-MΦ1 alone (25 days versus 38 days) (Fig. 7a, Supplementary Table 1). These results indicated that anti-PD-L1 reduced the therapeutic efficacy of NPs-MΦ. The PD-L1 expression in Un-MΦ and NPs-MΦ was approximately 3.22-fold and 5.29-fold higher than in B16F10 cancer cells, respectively, among which the highest was that in NPs-MΦ (Fig. 7b). The intracellular uptake of αPD-L1 positively correlated with the PD-L1 expression among the tested cells following a 1-h incubation analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 7c, left, designated as 0 h). After 4 h, the αPD-L1 content in NPs-MΦ, calculated as the sum of the intracellular and exocytotic amount, was reduced to approximately 20.39% of the initial level (Fig. 7c, left, blue columns, 4 h versus 0 h). By contrast, the αPD-L1 in B16F10 cells was decreased to approximately 78.31%. This result demonstrated a significant antigen-specific degradation of αPD-L1 by NPs-MΦ following the receptor-mediated internalization due to their elevated PD-L1 expression and enhanced digestive capability (Fig. 7d).

Fig. 7. TGF-β inhibitor but not PD-L1 blockade improves the adoptive macrophage therapy.

a Combinatorial αPD-L1 and the adoptive macrophage transfer therapy (NPs-MΦ1) for B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice. Upper, the treatment regimens. Lower, individual tumor growth curves and the corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves, log-rank analysis (n = 8 mice for Control, αPD-L1 or αPD-L1 + NPs-MΦ1 groups, and n = 10 mice for NPs-MΦ1 group). b Expression of PD-L1 in the B16F10 cells, Un-MΦ or NPs-MΦ in vitro, relative to isotype control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 3 biologically independent samples). c Uptake and degradation of αPD-L1 by Un-MΦ, NPs-MΦ, or the tumor cells. The amount of αPD-L1 within the cells after a 1-h incubation with αPD-L1 was measured by ELISA, and designated as ‘0 h’. After replacement with the fresh medium and incubation for another 4 h, the total amount of αPD-L1, designated as ‘4 h’, in the red box was calculated as the sum of the intracellular and exocytotic measurements listed on the right. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post-test (n = 5 biologically independent samples). d Schematic illustration of the PD-L1-mediated internalization and degradation of αPD-L1 by NPs-MΦ. e Combinatorial TGF-β inhibitor and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy (NPs-MΦ1) for B16F10 melanoma-bearing mice. Upper, the treatment regimens and the corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Lower, individual tumor growth curves, log-rank analysis (n = 10 mice). f The changes of immune cell populations in tumors after combinatorial TGF-β inhibitor and the adoptive NPs-MΦ1 therapy in the B16F10 mouse model at day 22. CD11b+Gr-1+ MDSC subsets (CD11b+Gr-1high granulocytic (G-MDSC) and CD11b+Gr-1int monocytic (M-MDSC)), Treg cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) as well as granzyme B-positive CD8+ T cells (CD8+GranB+) and IFN-γ-positive CD8+ T cells (CD8+IFN-γ+) in the tumor were analyzed. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-test (n = 5 mice). Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Further, to investigate whether anti-PD-1 (αPD-1) blockade could overpass the degradation of anti-PD-L1 caused by transferred macrophages, a combinatorial αPD-1 antibody and NPs-MΦ transfer therapy was conducted. The combo treatment significantly reduced B16F10 tumor burden of mice in comparison with the αPD-1 alone or the NPs-MΦ transfer alone (Supplementary Fig. 13a). The medium survival time of mice in the combinatorial group was 49.5 days, significantly longer than that of PD-1 blockade alone of 26 days or NPs-MΦ transfer alone of 38 days (Supplementary Table 1). Compared with the Un-MΦ, the PD-1 expression by NPs-MΦ was reduced to approximately 55.02%, resulting in the lower uptake of αPD-1 by the NPs-MΦ (Supplementary Fig. 13b). After 4 h, the αPD-1 content in NPs-MΦ was reduced to approximately 43.20% of the initial level, while the αPD-1 in B16F10 cells was decreased to about 93.98% (Supplementary Fig. 13c). Despite the degradation of αPD-1 by NPs-MΦ, the tumor-bearing mice benefited from the combinatorial PD-1 blockade and NPs-MΦ therapy. However, the tumor recurrence still existed.

Alternatively, TEW-7197 as a TGF-β signaling inhibitor has completed phase I clinical study in patients with advanced solid tumors (NCT02160106) including melanoma45,46. TEW-7197 was selected to evaluate whether the adoptive macrophage therapy would benefit from the combinatorial TGF-β signaling inhibitors against tumor resistance. The results showed that the adoptive NPs-MΦ combined with TEW-7197 treatment significantly delayed the tumor growth in comparison with TEW-7197 alone or NPs-MΦ transfer alone (Fig. 7e). The medium survival time of mice receiving TEW-7197 alone or NPs-MΦ alone was 26 days or 38 days. By contrast, a combinatorial TEW-7197 with NPs-MΦ transfer therapy was prolonged to 45 days (Supplementary Table 1). Besides, the combinatorial treatment ameliorated immune-suppressive TME, evidenced by the significant reduction of the inhibitory cell subsets of regulatory T (Treg) cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), as well as the increase in the infiltration of IFN-γ-producing and GranB-producing CD8+ T effector cells into tumor (Fig. 7f). These results demonstrated that the TGF-β signaling inhibitor enhanced the antitumor effect of NPs-MΦ. However, the combination therapy was unable to eradicate the tumor with recurrence.

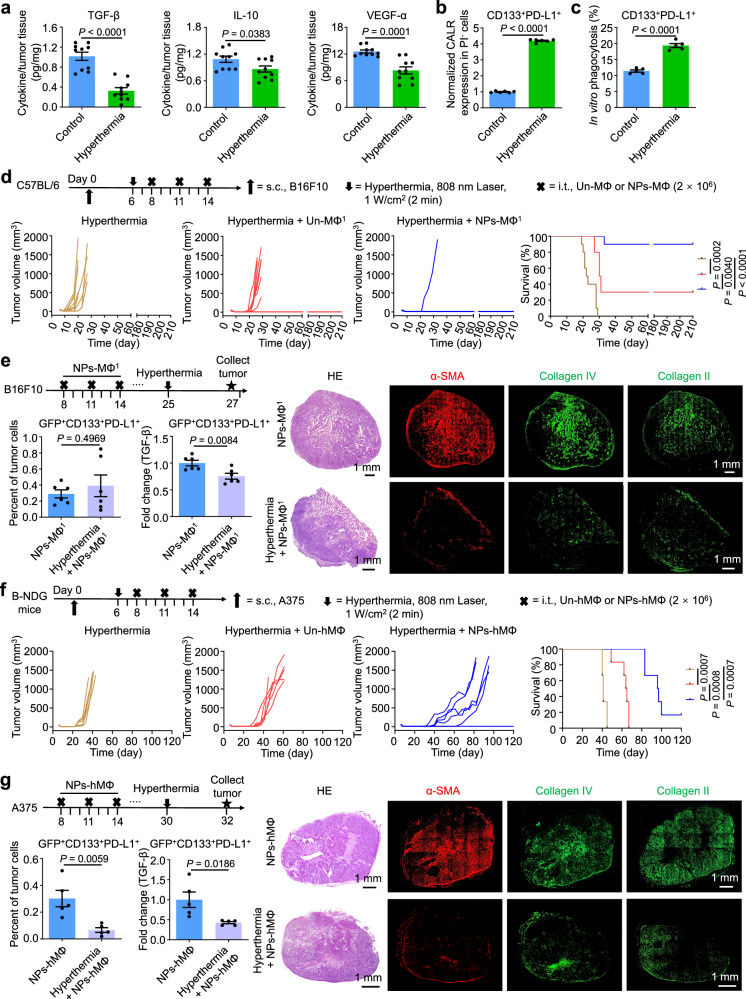

Hyperthermia reverses resistance of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells to adoptive macrophages

With the proposed adjuvant hyperthermia, the production of TGF-β, IL-10 and VEGF-α within the B16F10 tumor was significantly decreased following an 808 nm laser illumination at 1 W/cm2 for 2 min (Fig. 8a). In the in vitro experiment, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells were treated with temperatures ranging from 41 °C to 47 °C for 30 min or 60 min. The results of flow cytometric analysis showed the highest CALR expression on the cell membrane at 45 °C for 30 min, which was about 4.19-fold of the control group at 37 °C (Fig. 8b, Supplementary Fig. 14), resulting in an enhanced phagocytosis by NPs-MΦ (Fig. 8c). To examine the antitumor effect of combinatorial hyperthermia and the adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, we performed the hyperthermia treatment of tumor at 2 days before i.t. injection with the macrophages. Hyperthermia in combination with either the Un-MΦ or NPs-MΦ transfer significantly reduced tumor loading and prolonged medium survival times compared to hyperthermia alone in the mouse B16F10 melanoma model (Fig. 8d). The medium survival time of mice receiving hyperthermia alone or a combinatorial hyperthermia and the Un-MΦ transfer therapy was 22.5 days or 30.5 days. By contrast, a 90% of cure was achieved in the B16F10-bearing mice receiving a combinatorial hyperthermia and the NPs-MΦ transfer therapy (Supplementary Table 1). The long-term survival benefit was supported by the decreased suppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and Treg populations as well as the increased GranB-producing CD8+ T cells and the effector memory CD8+ T cells in spleen (Supplementary Fig. 15). To investigate whether hyperthermia would attenuate TGF-β production in CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells and tumor stiffness in the relapsed B16F10 melanoma model following the NPs-MΦ transfer, the hyperthermia treatment was given following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 25, and the tumor samples were collected at 2 days after hyperthermia treatment. The number of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells did not change in the relapsed B16F10 tumor after hyperthermia treatment, while a significant decrease in the TGF-β level of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells was observed (Fig. 8e, left). The adjuvant hyperthermia treatment led to a significant reduction in the CAFs characterized by the α-SMA, as well as in the main ECM components collagen IV and collagen II in the relapsed B16F10 tumor (Fig. 8e, right).

Fig. 8. Hyperthermia reverses the resistance of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells and improves the antitumor efficacy of the adoptive macrophage transfer.

a Quantification of TGF-β, IL-10, and VEGF-α within the tumor tissues of mice by ELISA, respectively. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 10 mice). b Elevated surface CALR expression in the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells under hyperthermia in vitro. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 6 biologically independent samples). c Enhanced phagocytosis of the hyperthermia-treated CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells by NPs-MΦ. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 5 biologically independent samples). d Combinatorial hyperthermia and adoptive transfer of Un-MΦ or NPs-MΦ in the B16F10-bearing mice. Upper, treatment regimens. Lower, the individual tumor growth curves and Kaplan-Meier survival curves, log-rank analysis (n = 10 mice). e Hyperthermia attenuated TGF-β production in CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells and tumor stiffness in the relapsed B16F10 melanoma following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment. Left, the changes in the number and the intracellular TGF-β level in GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells. The TGF-β level was normalized with that in the GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells without hyperthermia. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 6 mice). Right, micrographs of H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA and collagens. The image shown is representative of n = 3 independent replicates of experiments with similar results. f Combinatorial hyperthermia and adoptive transfer of Un-hMΦ or NPs-hMΦ in human A375 bearing B-NDG mice. Upper, treatment regimens. Lower, individual tumor growth curves and Kaplan-Meier survival curves, log-rank analysis (n = 6 mice). g Hyperthermia attenuated TGF-β production in PD-L1+ cancer cells and tumor stiffness in relapsed A375 melanoma model following the NPs-hMΦ transfer. Left, the changes in the number and the intracellular TGF-β level in GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells. The TGF-β level was normalized with that in the GFP+CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells without hyperthermia. Unpaired two-tailed t-test (n = 5 mice). Right, micrographs of H&E staining and immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA and collagens. The image shown is representative of n = 3 independent replicates of experiments with similar results. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Further, we depleted CD8+ T cells using anti-CD8 antibody twice a week for 3 weeks, to elucidate the role of CD8+ T cells in mediating the antitumor effect and tumor rejection in mice. The efficiency of depletion was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood. The results showed the depletion of CD8+ T cells dramatically reduced the therapeutic efficacy of the adoptive NPs-MΦ transfer. In the cured mice following the combination therapy with hyperthermia and NPs-MΦ, the depletion of CD8+ T cells led to growth of the rechallenged tumor (Supplementary Fig. 16).

In human A375 melanoma model, the medium survival time of mice receiving the combinatorial hyperthermia and the NPs-hMΦ transfer therapy prolonged to 96.5 days, significantly longer than that of hyperthermia alone (41 days) or the group of hyperthermia combined with Un-hMΦ transfer (64.5 days) (Fig. 8f, Supplementary Table 2). Hyperthermia treatment in the relapsed A375 tumor significantly reduced both the number of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells, and the TGF-β expression in the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells (Fig. 8g, left). Adjuvant hyperthermia treatment also resulted in a significant reduction in the CAFs and tumor ECM components in A375 tumor (Fig. 8g, right). These results demonstrated adjuvant hyperthermia may potentially overcome the resistance to the adoptive NPs-MΦ therapy by increasing the susceptibility to the macrophage phagocytosis, decreasing the TGF-β level in PD-L1+ cancer cells and tumor stiffness.

To test the feasibility of hyperthermia with the adoptive macrophage therapy of tumors in deep locations, the intraoperative near-infrared window-II (NIR-II) fluorescence image-guided hyperthermia of the mice bearing orthotopic CT26-Luc colon cancer was performed with our reported theranostic probes BPBBT NPs47. Following the i.v. injection with BPBBT NPs, both primary and metastatic tumor foci of mice were detected under the intraoperative NIR-II fluorescence imaging (Supplementary Fig. 17a, b). The hyperthermia with an NIR laser illumination (5 W/cm2, 2 min, 808 nm) was applied to both primary and metastatic tumor under the imaging guidance, followed by the image-guided i.t. injection of NPs-MΦ. The intraoperatively NIR-II fluorescence image-guided hyperthermia alone and adoptive transfer with NPs-MΦ alone extended the median survival times of mice to 45 days and 48 days, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 17c, d). By contrast, the intraoperatively image-guided combination therapy resulted in a complete cure of mice free of tumors within 60 days of observation.

Discussion

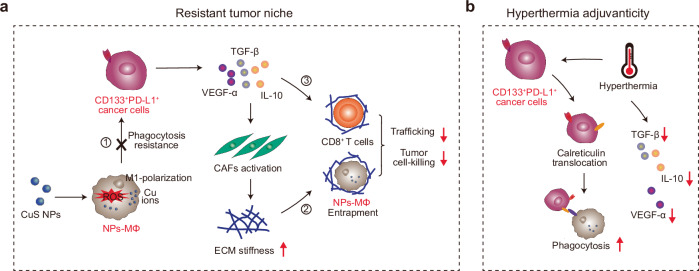

In summary, we identified a subpopulation of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells, and demonstrated their role in melanoma resistant to the adoptive macrophage therapy. The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells overexpressed immunosuppressive molecules to activate the TGF-β signaling pathway in the tumor. The elevated TGF-β in the relapsed tumor induced the CAFs to enhance the stiffness of the ECM, thus prohibiting the transferred macrophages and the infiltrated effector cells from trafficking and infiltration. The CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells dampened the phagocytotic clearance capacity of the adoptive macrophages as well as the tumor cell-killing capability of the effector cells through the immunosuppressive factors (Fig. 9a). We also highlighted that hyperthermia, but not antibody for PD-L1 blockade, reversed the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells resistance to the phagocytosis by transferred macrophages, to cooperatively improve the therapeutic efficacy of the adoptive macrophage transfer (Fig. 9b). Adjuvant hyperthermia presented a promising approach to overcoming the resistance to the macrophage therapy.

Fig. 9. The roles of CD33+PD-L1+ cancer cells in the tumor resistant to adoptive macrophage therapy and hyperthermia adjuvant therapy.

a Schematic illustration of tumor niche fostered by the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells resistant to the adoptive NPs-MΦ therapy. The mechanism involves 1) the inherent resistance of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells to the phagocytosis by the engineered macrophages; 2) the activation of CAFs to increase the stiffness of the ECM to prohibit the transferred macrophages and the effector CD8+ T cells from tumor trafficking; 3) the inhibition of the phagocytosis capacity of the adoptive macrophages as well as the tumor lysis ability of the CD8+ T cells through immunosuppressive factors. b Scheme for hyperthermia adjuvanticity to the adoptive macrophage transfer. Hyperthermia reverses the resistance of the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells to transferred macrophages by increasing the ‘eat me’ signal of CALR, cooperatively improving the therapeutic efficacy of the adoptive macrophage transfer.

A tumor niche was observed characterized by the stiffened tumor-associated ECM, which acted as a physical barrier to inhibit the trafficking of the transferred macrophages. The formation of the adoptive macrophage therapy-resistant tumor niche was ascribed to the TGF-β signaling pathway, which was particularly activated in the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells following the therapy. Previous reports demonstrated the CD133+ mouse melanoma cells capable of regulating the immunosuppressive TME by activating TGF-β35, as well as the TGF-β-responding squamous cell carcinoma stem cells competent to drive tumor relapse via dampening the cytotoxic T cells48, and to increase the drug resistance49. Our data together with these results highlighted that the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells upregulated the TGF-β pathway to foster a tumor niche refractory to either immune cell therapy or chemotherapy. In this niche, TGF-β played a central role in mediating the communication, including the induction of the TME cells towards pro-tumorigenic polarization, the promotion of the CAF-mediated ECM stiffness, and the regulation of cancer cells stemness maintenance20.

The expression of PD-L1 is generally classified into the constitutive and inducible types50. The PD-L1 expression in the tumor cells can be inducible when cocultured with the CAFs activated by TGF-β. A possible mechanism could be through the CXCL5 secreted by CAFs to bind to its receptor CXCR2 on the tumor cells to activate the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway of the tumor cells51,52. Besides the signaling loop of TGF-β, CAFs, and PD-L1, the interplay among TGF-β, EMT, and PD-L1 was reported to induce a higher PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, where TGF-β served as a key inducer of the EMT process20,53,54. In the squamous cell carcinoma model resistant to the adoptive T cell transfer therapy, the CSCs selectively expressed CD80 to substitute CD28 in the relapsed tumor so as to interact with the cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) on the activated cytotoxic T cells to exhaust the transferred T cells48. Besides, the high expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells was widely documented to contribute to tumor immune evasion through mechanisms such as inhibiting the activation, expansion and effector functions of CD8+ T cells55,56, and impeding the phagocytotic clearance by phagocytes57,58. In our study, the increased ‘don’t eat me’ signal of PD-L1 prevented CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells from phagocytosis by the engineered macrophages or lysis by the effector splenocytes. Therefore, CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells characterized by the highest TGF-β level among the tumor cells in vivo, with the upregulated PD-L1 expression in response to TGF-β through autocrine or paracrine, escaped the phagocytosis by the transferred macrophages and created a macrophage therapy-resistant niche for the relapse.

The identification of CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells in the relapsed tumor following the adoptive macrophage therapy holds several significant clinical implications. First, this population may represent a resistance marker of tumor cells based on the mechanism of the TGF-β-activated pathway. Clinical data showed that a heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression among cancer patients, and PD-L1 alone might be a useful but not a definitive biomarker in tumor management55,59–61. In contrast, the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells may serve as a robust biomarker to predict tumor progression and treatment efficacy, since they are detectable in patients with advanced melanoma. Second, the presence of the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells in the tumor implied an additional therapeutic target available for adjuvant interventions in clinical practice. Measures designed to specifically inhibit or eliminate the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells or effectively reverse the CD133+PD-L1+ cancer cells-sustained immunosuppressively physical and biological TME, such as targeting the TGF-β signaling46,62, or other cellular or molecular TME components63,64, are expected to augment the therapeutic efficacy of the existing treatment protocols.

The combined αPD-L1 with the adoptive NPs-MΦ transfer unable to produce a synergetic effect in treating melanoma, was ascribed to the antigen-specific degradation of αPD-L1 by the PD-L1+ macrophages and the attritted PD-L1 blockade in the presence of TGF-β. Comparatively, although the degradation of αPD-1 by the transferred NPs-MΦ, the PD-1 blockade plus adoptive NPs-MΦ transfer showed the enhanced antitumor effect. This may be attributed to the following reasons. First, compared to PD-L1, the expression of PD-1 by the NPs-MΦ was significantly lower, resulting in decreased internalization of the surface-bound αPD-1 (Supplementary Fig. 13b, c). Second, besides the PD-1 blockade effect on the tumor cells, the αPD-1 additionally blocked the PD-1 on CD8+ T cells, to activate the CD8+ T cells and promote the antitumor immune responses. However, the PD-1 blockade plus adoptive NPs-MΦ transfer experienced tumor relapse. Previous study reported the antibody transfer ability of TAMs through a non-specific mechanism. The administered αPD-1 captured from the PD-1+ T cell surface was transferred to the PD-1- TAMs by Fcγ receptor, leading to resistance to the macrophage-mediated αPD-1 therapy65. Our results and the previous research data collectively indicated that immune checkpoint blockade with antibodies may not be appropriate for the adoptive macrophage transfer due to their nature of avid phagocytosis and digestion.

Mild hyperthermia primarily provokes apoptotic responses to elicit immune responses rather than to induce complete necroptotic cell death66. The molecular mechanisms involve attenuation of the density of tumor ECM, recruitment of the immune cells, inhibition of the TGF-β pathway, as well as the production and release of heat shock proteins (HSPs)28,67–69. In general, excessive hyperthermia is referred to as thermal ablation that produces tumor cell necrosis at temperatures exceeding 50 °C for more than 6 min, while mild hyperthermia typically ranging from 40–45 °C for a time duration between 15 min and 72 h may cause cell injury instead of death70,71. Regarding the hyperthermia treatment in our study, we used an 808 nm laser to irradiate the tumor of mice for 2 min. With an infrared thermal imaging camera, a temperature of 51 °C was recorded on the surface of skin above the tumor at the site of laser exposure. The temperature of the subcutaneous tumor especially the deep and marginal regions of tumor was expected to be below 51 °C, due to the skin tissue absorption of the light. Since the tumor recurrence was observed in the mice bearing B16F10 or A375 melanoma treated with hyperthermia alone (Fig. 8d, f), the hyperthermia treatment under such conditions may bring sublethal or partially irreversible tumor damage. Therefore, the thermally injured tumor cells are susceptible to other treatment including phagocytosis by the adoptively transferred macrophages. The released heat shock proteins can chaperone tumor antigens to either DCs or the adoptive macrophages for antigen presentation71. We will compare the effects of different hyperthermia conditions on the immunogenic response in a future study.

Besides the melanoma treatment, the combinatorial hyperthermia with the macrophage transfer may show promising for the treatment of other superficial tumors such as head and neck cancer in clinical practice. Regarding the deep-seated tumors, because the tissue penetration of NIR light is limited to centimeters in depth, surgery or interventional therapy is additionally required, through which an intraoperative or interventional diagnosis can be applied to visualizing the tumor localization to ensure the treatment accuracy of hyperthermia. Our previous studies have demonstrated that the intraoperative NIR-II fluorescence imaging enables the detection of microtumors of size as small as 0.5 mm × 0.3 mm, and substantially improved the accuracy of photothermal therapy under the image-guidance in the orthotopic colon tumor model47. Here, by using the same imaging agents, we showed that the combinatorial intraoperative NIR-II fluorescence image-guided hyperthermia and adoptive NPs-MΦ transfer achieved a complete cure of mice. Since the widely used colonoscopy for colon cancer diagnosis and treatment in clinics, the NIR-II fluorescence image-guided hyperthermia in combination with adoptive macrophage transfer under the colonoscopy shows promise for clinical application to colon cancer treatment.

Methods

Ethics statement

All the animal experiments were performed in compliance with the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the School of Pharmacy, Fudan University. For the animal experiments, the maximal tumor volume in mice permitted was 2000 mm3. The tumor size did not exceed this limit in this study. Human tumor specimens with a diagnosis of melanoma were randomly selected from the biobank at Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice (female, 6-8 weeks old) were ordered from Sino-British Sippr/BK Lab Animal Inc. (Shanghai, China). BALB/c mice (male, 18-20 g) were purchased from Shanghai Linchang Biological Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Male and female B-NDG Il2rg-/-hIL3-hGMCSF-hCSF mice (6-8 weeks old) were purchased from Biocytogen Inc. (Beijing, China). The mice were allowed to adapt to the environment for one week before the experiments, and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with free access to food and water. The light/dark cycle was from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. for light and from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. for dark. The ambient temperature was 20–26 °C and the humidity was 40–60%.

Cell lines

Mouse B16F10 melanoma cell line (cat. CRL-6475), mouse NIH3T3 embryonic fibroblast cell line (cat. CRL-1658) and human A375 melanoma cell line (cat. CRL-1619) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). B16F10 cells stably expressing green fluorescent protein (B16-GFP) and A375 cells stably expressing green fluorescent protein (A375-GFP) were generated through lentiviral transfection of B16F10 cells and A375 cells by Sunbio Medical Biotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China), respectively. Mouse CT26-Luc colon cancer cell line (CT26.WT-Fluc-Neo) was obtained from Imanis Life Sciences. Expect for the CT26-Luc cells cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (HyClone), all other cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, HyClone), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Preparation of CuS NPs-engineered macrophages

Poly(ethylene glycol)-modified copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NPs) were prepared72. Briefly, into 100 ml of water, 1 ml of CuCl2 (100 mM), 100 μl of sodium citrate (0.2 g/ml), 100 mg of SH-PEG5000-methoxy (Seebio Biotech, Inc. Shanghai, China), 100 μl of sodium sulfide solution (Na2S, 1 M) was added under stirring at room temperature. After stirring for 5 min, the mixture was heated to 90 °C and stirred for another 15 min. The mixture gradually turned from dark-brown to deep-green during this period, then cooled down in ice-cold water. The synthesized nanoparticles were concentrated with an ultracentrifuge tube (Amicon Ultra-15, cutoff MW 10 kD, EMD Millipore) at 4000 g for 15 min and washed with ddH2O.

CuS NPs-engineered mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (NPs-MΦ) were prepared14. Briefly, bone marrow cells from C57BL/6 mice were isolated, resuspended in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM, HyClone) with 10 ng/ml macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF, Peprotech), and plated on 6-well ultra-low attachment culture plate (Corning). On day 3, non-adherent cells were removed, and the medium was replaced with fresh medium. On day 6, cells were treated with 7.5 μg/ml CuS NPs for 48 h to obtain NPs-MΦ. Untreated cells were used as the control (Un-MΦ).

The CuS NPs-engineered human macrophages (NPs-hMΦ) were prepared from human peripheral blood monocytes. Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from healthy donor blood samples (AllCells Inc., China) were isolated by Ficoll-Paque PLUS (GE Healthcare). Then, anti-human CD14 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec) were used to enrich CD14+ monocytes according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were resuspended in RPMI medium containing 10 ng/ml of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF, Peprotech), and plated on 6-well tissue culture treated plate (Corning). At day 3 the culture medium was replaced with the fresh medium with the same concentration of GM-CSF. At day 6, the medium was replaced with the fresh medium containing 3.75 μg/ml of CuS NPs. After incubation for another 2 days, the purity and phenotype of the resulting NPs-hMΦ were analyzed by flow cytometry and bulk RNA-seq. The cells without receiving the nanoparticles were used as the untreated control (Un-hMΦ). The antibodies used were listed in Supplementary Table 4.

Tumor models

B16F10 cells (5 × 105) and A375 cells (5 × 106) were suspended in 50 μl of PBS and s.c. injected into the left flank of mice to establish C57BL/6 mice bearing mouse B16F10 melanoma model and B-NDG mice bearing human A375 melanoma model, respectively. For the orthotopic CT26 tumor model, CT26-Luc cells (2 × 106) in 25 μl of PBS were inoculated47. Specifically, BALB/c mice were anesthetized, and the abdominal skin was sanitized. A 3–5 mm incision was made in the lower abdomen to expose the cecum, into which CT26-Luc cells were injected. The cecum was then returned to the abdominal cavity, and the wound was closed with biodegradable sutures.

Tumor treatment

In the B16F10 tumor model, at 8 days post the tumor cell inoculation, the mice were randomly divided into different groups. The macrophages (2 × 106 per mouse) in 25 μl of PBS were intratumorally (i.t.) injected into the tumor. The tumor sizes were measured twice a week. For the three treatment cycles of the macrophage transfer therapy, the mice were i.t. injected with the macrophages at days 8, 11, 14, 20, 23, 26, 32, 35 and 38, respectively (n = 10). NPs-MΦ3, mice received three cycle-treatment with NPs-MΦ; Un-MΦ3, mice received three cycle-treatment with Un-MΦ; Control, mice without treatment. To elucidate the role of CD8+ T cells in mediating the antitumor effect, the NPs-MΦ1 treatment was performed and 200 μg of anti-CD8 antibody (αCD8, BioXCell, clone 2.43, cat. BE0061) per mouse was intraperitoneally (i.p.) injected twice a week for 3 weeks, starting at 1 day before the first dose of NPs-MΦ. For combinatorial αPD-L1 and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, the mice were intraperitoneally (i.p.) administered with αPD-L1 (200 μg/dose/mouse, BioXCell, clone 10 F.9G2, cat. BE0101) at days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18, and received the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days of 8, 11 and 14, respectively (n = 8). For combinatorial αPD-1 and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, the mice were i.p. administered with αPD-1 (200 μg/dose/mouse, BioXCell, clone RMP1-14, cat. BE0146) at days 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16 and 18, and received the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days of 8, 11 and 14, respectively (n = 10). For combinatorial TGF-β signaling inhibitor and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, the mice were daily orally (p.o.) administered with TEW-7197 (25 mg/kg) for 2 weeks began at day 8, and received the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at days of 8, 11 and 14, respectively (n = 10). For combinatorial hyperthermia and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, the tumor-bearing mice were received laser treatment at a power density of 1 W/cm2 for 2 min at day 6 (808 nm, MDL-F-808, Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Technology). The mice then received the NPs-MΦ1 treatment (n = 10). The diameter of the laser spot was adjusted to 0.8 cm and the laser power density was measured by an optical power meter (PS-100, Changchun New Industries Optoelectronics Technology). In a parallel experiment, to the cured B16F10-bearing mice from combinatorial hyperthermia and the NPs-MΦ1 treatment, 200 μg of αCD8 was i.p. injected twice a week for 3 weeks, starting at 1 day before the rechallenge of B16F10 tumor.

In the A375 tumor model, the mice received the i.t. injections of the macrophages at days 8, 11 and 14, respectively (n = 6). The three experimental groups included NPs-hMΦ, Un-hMΦ and Control. For combinatorial hyperthermia and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy, the tumor-bearing mice were i.t. injected of indocyanine green (ICG, 200 μM, 25 μl) plus the laser treatment at day 6 at a power density of 1 W/cm2 for 2 min at 808 nm. The temperature of tumor site reached 51 °C under the guidance of thermal imager (DT-980, CEM, China). Afterwards, the mice received the injections of the macrophages for one cycle-treatment (n = 6).

In the BALB/c mice bearing orthotopic CT26-Luc colon tumor model, a combinatorial intraoperative fluorescence image-guided hyperthermia47 and adoptive macrophage transfer therapy was performed. The theranostic probes BPBBT NPs was prepared using nanoparticle albumin-bound technology47. Briefly, 450 mg of HSA was dissolved in 30 ml of water (1.5%, w/v), and 30 mg of BPBBT was dissolved in 0.68 ml chloroform/ethanol (15/85, v/v). The two solutions were mixed and homogenized at 20000 psi (Nano debee homogenizer, USA) for nine cycles. The colloid suspension was then rotary evaporated, filtered (0.22 μm), and lyophilized.

The tumor treatment was started at day 4 post-tumor inoculation, when the mice were i.v. injected with the BPBBT NPs at a dose of 20 mg/kg. At day 5, the cecum with tumor of mice under anesthesia was surgically exposed. The primary and metastatic tumor foci were detected via the intraoperative near-infrared window-II (NIR-II) fluorescence imaging and received the laser treatment at a power density of 5 W/cm2 for 2 min at 808 nm. Subsequently, the mice were i.t. injected with one dose of the NPs-MΦ prepared from the healthy BALB/c mice under the same image-guidance (3 × 106 per mouse, n = 5). The cecum was then placed back into the abdomen. The abdominal skin of mice was sutured. The tumor burden of mice was monitored by the bioluminescence signal using an IVIS imaging (Caliper, Perkin Elmer) after i.p. injection of D-luciferin (15 mg/ml, 200 μl).

BioAFM analysis

The B16F10 tumor was collected at the relapsed stage following the 1 cycle-based NPs-MΦ transfer therapy at day 35. The mice before the treatment at day 8, and without treatment at day 16 were used as control. Of note, the mice without treatment at day 16, in which the tumor volume approximately reached the similar size ( ~ 500 mm3) to that of mice following the NPs-MΦ1 treatment at day 35. The tumor tissues were cryosectioned (20 μm thickness). The sections were thawed at room temperature before the measurement by BioScope Resolve AFM (Bruker). The mode of PeakForce Quantitative Nanomechanical Mapping (PeakForce QNM) was used to determine the change of stiffness in the tumor tissues by using a tip type of MLCT-BIO with a spring constant of 0.03 N/m and radius of 20 nm. The cantilever was calibrated using the thermal noise method before each experiment. Records were performed by 256 equidistant force-indentation traces with constant velocity in total 65536 points per trace within a 100 × 100 μm2 zone. Traces were then fitted with the Hertz model to determine the elastic properties of the tissue. A Poisson’s ratio of 0.5 was used for the calculation of the Young’s elastic modulus within one zone.

Immunofluorescence staining

For the cell samples, NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ were transferred to the poly-D-lysine-coated chamber slides (NUNC, cat. 154534) and allowed for a 2-h attachment. To evaluate the degradation of the phagocytized cancer cells, the nuclei of the A375 cancer cells were labeled with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma, 14533) at a concentration of 1 μg/ml and the membrane with DiD at the concentration of 1 mM in serum free DMEM for 30 min. The labeled cancer cells were cocultured with NPs-hMΦ or Un-hMΦ for 1 h at a ratio of cancer cells to macrophages 2:1. The un-engulfed cells were removed, and the macrophages were incubated for another 2 h. The cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and counterstained with SYTOX at a concentration of 1 µM for 30 min. After the PBS washing twice, the cells were visualized by Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope using a 63 × oil objective (Zeiss Zen 2012 software).

For the mouse tumor samples, the tumor was collected and embedded in OCT (Sakura Finetek) for cryosectioning (8 μm of thickness). The sections were fixed, permeabilized, blocked and stained overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-collagen II (Boster, cat. BA0533, 1:200) or rabbit anti-collagen IV (Boster, cat. BA3626, 1:200). The sections were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with the corresponding fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature, washed and mounted. The secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit IgG IRDye 800CW (Licor, cat. 926-32211, 1:500) for the imaging of the whole section by Odyssey Infrared Imaging System, or goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, cat. A-21428, 1:500) for confocal imaging. Mouse anti-α-SMA (Boster, cat. BM0002, 1:200) was labeled with Cy5-NHS ester (GE Healthcare) according to manufacturer’s protocol. The Odyssey infrared images analyzed using Image Studio (v5.2, Li-Cor). All the confocal images were analyzed using Olympus VS2000.

For the human melanoma specimens, the samples were collected from the biobank of Renji Hospital (Shanghai, China) for the paraffin embedment and sectioning (3 μm of thickness). The sample slides were dewaxed followed by the antigen retrieval by boiling with the citrate buffer at pH 6.0 for 15 min. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-CD133 (Abcam, clone CMab-43, cat. ab264538) or rat anti-PD-L1 (Abcam, clone CAL10, cat. ab279294). The secondary antibodies were goat anti-mouse IgG Alexa Fluor 633 (Invitrogen, cat. A-21050, 1:500) or goat anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 555 (Invitrogen, cat. A-21434,1:500). CaseViewer (v2.1, 3D Histech) was used to observe the immunofluorescent images. The number of CD133+, PD-L1+ or CD133+PD-L1+ cells within the field of view (FOV) was analyzed by Fiji ImageJ software (v2.1.0/1.53c, Freeware/NIH).

Intratumoral distribution of the transferred NPs-MΦ