Abstract

Introduction

The cost benefit of intercostal nerve cryoablation during surgical lobectomy for postoperative pain management is unknown. The current study compared hospital economics, resource use, and clinical outcomes during the index stay and accompanying short-term follow-up. Patients who underwent lobectomy with standard of care treatment for postsurgical pain management and cryoablation were compared to those with standard of care treatment only. We hypothesized that cryoablation would reduce narcotic use and index hospital and short-term costs.

Methods

A retrospective, propensity matched cohort of surgical patients treated between 2016 and 2022 from a US National All-Payer Database were used. Cost and outcome comparisons were made between groups using chi-square and t tests.

Results

From a cohort of 23,138 patients, 266 pairs with a mean age of 69 years were included. Matching variables included age, gender, lobe resected, and prior opioid use. Both groups had significant comorbidity history and prior opioid use; 66% (n = 175 both groups) underwent open lobectomy and 53% (n = 142 vs. 143) had the upper lobe resected. Cryoablation intervention was associated with 1.3 days reduced hospital stay (8.8 vs. 10.1 days, p = 0.31) and no difference in perioperative safety. After 90 days, postsurgery cryoablation patients had lower opioid prescription refills (27.3 vs. 36.9 morphine milligram equivalents, p = 0.03). Cryoablation patient costs trended less than non-cryoablation patients during index ($38,753 vs. $43,974, p = 0.10) and lower through 6 months (total costs, $65,703 vs. $74,304, p = 0.10). There was no difference in postsurgery resource use, but a smaller proportion of cryoablation patients had outpatient hospital visits (83.1%, N = 221 vs. 92.9%, n = 247, p < 0.01).

Conclusion

Cryoablation during lobectomy is safe and does not add incremental hospital costs. Clinical meaningful reductions in length of stay and postsurgery opioid use were observed with cryoablation intervention. The addition of cryoablation during surgery to reduce postoperative pain appears to be a cost-effective therapy.

Keywords: Medicare claims, Cancer, Cost-effective, Cryoablation, Lobectomy, Opioids, Pain management, Surgery

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Postsurgical pain following lobectomy for cancer is challenging to treat, especially for those who have a prior history of opioid use. |

| The current study compared hospital economics, resource use, and clinical outcomes during the index stay and accompanying short-term follow-up in patients undergoing lobectomy with cryoablation with standard of care treatment for postsurgical pain management compared to those with standard of care treatment only. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| The use of cryoablation for postsurgical pain was associated with a 1.3-day shorter length of stay compared to non-cryoablation patient. Index hospital costs were $5221 lower for cryoablation compared to non-cryoablation patients, although not reaching statistical significance. Opioid use was decreased significantly (26%, p = 0.03) by day 90 of follow-up for the cryoablation patients. |

| These results suggest that the addition of cryoablation for postsurgical pain management is cost-effective and associated with good clinical outcomes. |

Introduction

In the USA, there are over 50,000 lung cancer surgeries performed annually [1]. Pain following surgery is a major concern, especially after a thoracotomy approach [2]. Pain interferes with recovery, impacts quality of life [3], and is a risk factor for long-term chronic pain with narcotic use [4]. Thoracic epidurals and paravertebral blocks are usually the first-line regional anesthetic strategies for thoracic surgical procedures [5]. In addition to providing opioids for pain control, epidurals carry the risk of hematoma, infection, and postoperative hypotension [6, 7]. Given increased concern about the risk of long-term opioid use, other non-pharmacological strategies should be considered, especially the short-term recovery period.

One non-pharmacological alternative method for acute pain management after thoracotomy is intercostal cryoanalgesia with cryoablation, which involves intraoperative freezing of intercostal nerves by the operating surgeon [8]. This approach has been effective at treating postoperative pain, without permanent nerve damage and reducing opioid use in other populations [9–11], but remains understudied in lung cancer surgery [12]. Even less is known about the economic impact of cryoablation within hospital and payor economics, which is important for value-based care. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to assess the impact of adjunctive intraoperative cryoablation performed during lung cancer surgery and impact on opioid use, hospital cost, and patient outcomes. We hypothesized that cryoablation would reduce narcotic use and index hospital and short-term costs.

Methods

Data Source

A contemporary, nationally representative database was used for the analysis (STATinMED’s RWD Insights). This data was publicly available and aggregated and included claims data from approximately 80% of the US health care system (Medicare, Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and commercial insurances). This data is sourced directly from claims clearing houses, which are responsible for managing claims transactions as they go between payers and providers. Data were de-identified, and data use complied with the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for the privacy and security of protected health information. Since this study used retrospective data, initially available in the public and anonymized the study did not meet Health and Human Service Services definition as human research (as defined in 45 CFR 46.102) and was exempt from IRB review.

Patient Selection

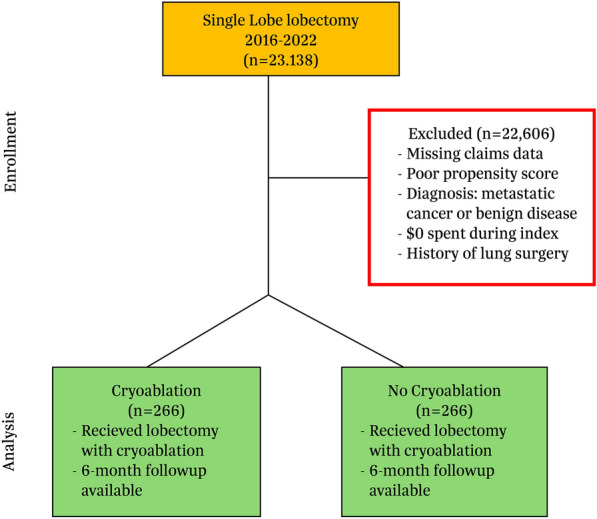

Patients aged 18 years or older undergoing single surgical lobectomy between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2022 were selected for the study (Fig. 1). Patients with open, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), or robotic-assisted thoracic (RATS) approach were included. Patients in the cryoablation group had International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Procedure Classification System (ICD-10-PCS) procedure code (01580ZZ or 01584ZZ) during the index visit. The cryoablation procedure is performed as a distinct ancillary ablation procedure (− 50 to − 70 °C for 120 s per level) at multiple levels using the AtriCure CryoICE cryoablation system (AtriCure, Inc; Mason, OH) (Fig. 2). Under direct visualization the surgeon identifies the intercostal nerves and ablates the intercostal spaces, usually five levels before lobectomy. In the authors hands, cryoablation typically requires 8–12 min operative time to administer and is considered ancillary to the planned primary lobectomy procedure. The cryoablation intervention was added to non-standardized standard of care (SOC; epidural, regional blocks, opioids, non-opioids, etc.) for postsurgical pain management at each institution and compared to those undergoing SOC without cryoablation.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram. Adult patients who had lobectomy for lung cancer performed between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2022 were included. Patients with missing claims data preoperatively and during follow-up, those with metastatic cancer or infectious etiology, or $0 spent for index procedure were excluded. The final matched cohort included 266 patients in both groups

Fig. 2.

Cryoablation of intercostal nerve during surgical lobectomy

Patients had continuous capture of medical and pharmacy benefits for the 12-month pre and at least 6 months after the index date. Six months postoperatively was chosen given the importance to assess continued use of opioids following surgery. Exclusion criteria included prior lung surgery such as lobectomy, pneumonectomy, or sublobar resection (segmentectomy and wedge resection) in the 12 months prior to index. Other exclusion criteria included lung resection for metastatic disease, benign disease, or $0 spent on the index visit.

Patient Demographics

Patient demographic characteristics and procedure variables were recorded at the index date and included age, gender, lobe resected, geographic area, and insurance type. Comorbidities of interest were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) present in claims. Key comorbid conditions included presurgery atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, smoking status, opioid use, and chemotherapy status.

Clinical and Economic Outcomes

The primary study endpoints were average length of stay (ALOS), postdischarge resource use, hospital readmissions, emergency department (ED) visits, and hospital outpatient and pharmacy costs over time. Opioid use and dosage were estimated as morphine milligram equivalents (MME) from prescriptions filled (Supplemental Methods). Secondary endpoints included safety variables such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, prolonged air leak, and acute respiratory failure.

Medicare cost reports from claims submissions using cost-to-charge ratios (CCR) were used to estimate average hospital costs. Costs included both direct and indirect costs and included various cost centers (operating room, pharmacy, supplies, etc.). CCR are standard ways in which US Medicare reports costs and utilization. Summed costs over time included total healthcare costs, inpatient services, outpatient services, and total outpatient pharmacy costs (included National Drug Code, NDC) claims only. Physician fees were not included in the cost analysis, as they usually represent less than 10% of hospital reimbursement.

Propensity Matching and Statistical Analysis

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to control patient baseline differences. PSM reduces the effects of bias and confounding variables by removing confounding factors between groups and increasing comparability between the groups [13]. Variables used in the PSM logistical regression included age, gender, prior opioid use status, surgical approach, and lobe resected. Patients who underwent lobectomy with and without cryoablation were matched using the nearest neighbor matching method, a caliper width of 0.1, and no replacement resulting in a 1:1 matched sample reducing standardized differences to less than 0.1 after matching. After matching, comparisons were described using proportions for categorical variables and means with standard divisions for continuous variables. Differences between groups were tested with the chi-square test for categorical variables and Student t test for continuous variables. To minimize the effect of outliers on our estimates we employed Winsorization at the 97.5th and 2.5th percentiles when outliers were identified. For patients with opioid dosage above the 97.5th percentile the values were set to the 97.5th percentile level. Similarly, for those below the 2.5th percentile, the values were set to the 2.5th percentile level. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using R Version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 22,872 patients were available for matching with 266 lobectomy patients with ancillary cryoablation during surgery (Table 1). Patient cohorts were well matched, with standard mean differences below 10.0. Mean age for the lobectomy without and with cryoablation groups was 68.8 and 68.6 years, respectively. Both groups had a higher proportion of women to men, a greater proportion of Caucasians than non-Caucasians, and more than 70% with Medicare coverage. Over 80% of procedures were elective in nature, and more than 50% were performed at teaching institutions. Clinically, both groups had 50% or greater proportion of patients with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, a smoking history, and were opioid users in the previous year.

Table 1.

Patient and hospital characteristics of propensity matched patients who had lobectomy with or without cryoablation of peripheral intercostal nerve for postoperative pain control

| Variable | Pre-matched | Propensity matched | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy (n = 22,872) | Lobectomy without cryoablation (n = 266) | Lobectomy with cryoablation (n = 266) | p value | |

| Patients | ||||

| Mean age | 68.3 (9.4) | 68.8 (9.5) | 68.6 (10.1) | 0.84 |

| Female | 13,092 (57.2) | 143 (53.8) | 146 (54.9) | 0.86 |

| White | 16,124 (70.5) | 201 (75.6) | 181 (68.0) | 0.07 |

| Black | 1750 (7.7) | 17 (6.4) | 24 (9.0) | 0.33 |

| Medicare insurance | 16,055 (70.2) | 190 (71.4) | 195 (73.3) | 0.70 |

| Medicaid insurance | 2274 (9.9) | 20 (7.5) | 25 (9.4) | 0.53 |

| Commercial insurance | 3540 (15.5) | 43 (16.2) | 34 (12.8) | 0.32 |

| US census region and teaching status | ||||

| Midwest | 6638 (29.0) | 94 (35.3) | 65 (24.4) | < 0.01 |

| Northeast | 4310 (18.8) | 37 (13.9) | 27 (10.2) | 0.23 |

| South | 8549 (37.4) | 102 (38.3) | 110 (41.4) | 0.54 |

| West | 3371 (14.7) | 33 (12.4) | 64 (24.1) | < 0.01 |

| Teaching hospital | 12,450 (54.4) | 143 (53.8) | 152 (57.1) | 0.49 |

| Elective procedure | 19,030 (83.2) | 216 (81.2) | 230 (86.5) | 0.13 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | 802 (3.5) | 7 (2.6) | 9 (3.4) | 0.80 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2355 (10.3) | 28 (10.5) | 31 (11.7) | 0.78 |

| CHF | 2162 (9.5) | 28 (10.5) | 25 (9.4) | 0.77 |

| COPD | 11,680 (51.1) | 132 (49.6) | 145 (54.5) | 0.30 |

| Diabetes | 5811 (25.4) | 72 (27.1) | 66 (24.8) | 0.62 |

| Hypertension | 14,993 (65.6) | 188 (70.7) | 170 (63.9) | 0.12 |

| Obesity | 4000 (17.5) | 52 (19.5) | 46 (17.3) | 0.58 |

| Renal failure or dialysis | 2574 (11.3) | 35 (13.2) | 32 (12.0) | 0.79 |

| Smoking history | 15,033 (65.7) | 175 (65.8) | 177 (66.5) | 0.93 |

| Quan Charlson Comorbidity Indexa | 4.2 (3.2) | 4.2 (3.2) | 4.1 (2.8) | 0.80 |

| Cancer or opioid therapy in year prior to surgery | ||||

| Opioid use | 19,478 (85.2) | 225 (84.6) | 231 (86.8) | 0.54 |

| Methadone use | 43 (0.2) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Chemotherapy | 6329 (27.7) | 79 (29.7) | 75 (28.2) | 0.77 |

| Radiation therapy | 681 (3.0) | 6 (2.3) | 8 (3.0) | 0.79 |

| Immunotherapy | 705 (3.1) | 7 (2.6) | 12 (4.5) | 0.35 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

CHF congestive heart failure, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

aScores on the Quan Charlson Comorbidity Index are computed by adding the weights that are assigned to the specific diagnoses. The minimum possible score is 0 and the maximum possible score is 24

Open lobectomies were performed in 65.8% (n = 175) in both groups, and minimal invasive surgery (VATS or RATS) was performed in the remaining procedures (Table 2). During surgery, the upper lobes were the most resected lobes. ALOS was 1.3 days less for cryoablation patients (8.8 days vs. 10.1 days, p = 0.31), but did not reach statistical significance. Similar numerical reductions in ALOS were observed for cryoablation patients who had presurgical opioid use in the year prior (9.0 days vs. 10.9 days, p = 0.21), but again not significant. There was no difference in prolonged air leak, pneumothorax, or major bleed in the first 30 days after surgery between groups (Table 3). Both groups also had similar rates of postoperative atrial fibrillation (n = 50, 18.8% vs. n = 54, 20.3%, p = 0.74).

Table 2.

Surgical characteristics and length of stay of propensity matched patients who had lobectomy with or without cryoablation of peripheral intercostal nerve during surgery for postoperative pain control

| Variable | Propensity matched | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy without cryoablation (n = 266) | Lobectomy with cryoablation (n = 266) | p value | |

| Surgery performed, lobe resected, and mechanical ventilation | |||

| Open lobectomy | 175 (65.8) | 175 (65.8) | 1.00 |

| MIS VATS lobectomy | 55 (20.7) | 52 (19.5) | 0.83 |

| MIS RATS lobectomy | 36 (13.5) | 39 (14.7) | 0.80 |

| Right upper lobe | 80 (30.1) | 87 (32.7) | 0.58 |

| Right middle lobe | 21 (7.9) | 25 (9.4) | 0.64 |

| Right lower lobe | 62 (23.3) | 53 (19.9) | 0.40 |

| Left upper lobe | 62 (23.3) | 56 (21.1) | 0.60 |

| Left lower lobe | 41 (15.4) | 45 (16.9) | 0.72 |

| Those requiring mechanical ventilation > 24 h | 6 (2.3) | 4 (1.5) | 0.75 |

| Hospital length of stay | |||

| Index stay days | 10.1 (17.6) | 8.8 (11.8) | 0.31 |

| % with index stay > 14 days | 30 (11.3) | 22 (8.3) | 0.31 |

| Index stay days, prior opioid use | 10.9 (19.0) | 9.0 (12.6) | 0.21 |

| Discharge location | |||

| Home | 160 (60.2) | 175 (65.8) | 0.21 |

| Home health service | 76 (28.6) | 72 (27.1) | 0.78 |

| Skilled nursing facility | 9 (3.4) | 6 (2.3) | 0.60 |

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

MIS minimal invasive surgery, VATS video assisted thoracoscopic surgery, RATS robotic assisted thoracoscopic surgery

Table 3.

Surgical safety of propensity matched patients who had lobectomy with or without cryoablation of peripheral intercostal nerve during surgery for postoperative pain control

| Variable | Propensity matched | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy without cryoablation (n = 266) | Lobectomy with cryoablation (n = 266) | p value | |

| 30-day safety events | |||

| All-cause mortality | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.00 |

| Air leak | 23 (8.6) | 19 (7.1) | 0.63 |

| Pneumonia | 20 (7.5) | 33 (12.4) | 0.08 |

| Pneumothorax | 30 (11.3) | 39 (14.7) | 0.30 |

| Pulmonary collapse | 78 (29.3) | 83 (31.2) | 0.71 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 7 (2.6) | 5 (1.9) | 0.77 |

| Major bleed | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0.62 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 50 (18.8) | 54 (20.3) | 0.74 |

Values are n (%)

Opioid use was assessed through average prescription dosage refill and represented a proxy for opioid use (Table 4). Some of the opioids tracked included tramadol, codeine, opium, morphine, and oxycodone (Supplemental Table). Non-opioid treatments were not assessed. There were no differences at discharge through the first 90 days after surgery in average opioid dosage refill. However, between 90 and 180 days after surgery, the cryoablation group had 26% lower opioid requirements than no cryoablation (27.3 MME vs. 36.9 MME, p = 0.03). A similar 28% reduction in opioid use was found for those who were chronic opioid users postoperatively, defined as average opioid usage in the first 14 days postoperatively and also at 90–180 days postoperatively (22.4 MME vs. 31.2 MME during 90–180 days, p = 0.02). Overall inpatient and outpatient postoperative resources did not differ between groups (Table 5). Visits to the emergency room and hospital readmission rates were similar, although cryoablation patients had fewer outpatient hospital visits in the 6 months after surgery (n = 221, 83.1% vs. n = 247, 92.9%, p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Opioid prescription dosage refill during follow-up in propensity matched patients who had lobectomy with or without cryoablation of peripheral intercostal nerve during surgery for postoperative pain control

| Variable | Lobectomy without cryoablation (n = 266) | Lobectomy with cryoablation (n = 266) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index through 30 days | 12.7 (17.3) | 13.0 (17.7) | 0.84 |

| 31 days through 90 days | 27.4 (30.2) | 25.8 (26.7) | 0.70 |

| 91 days through 180 days | 36.9 (34.7) | 27.3 (29.1) | 0.03 |

| Average of 14-day post index and 91–180 days post surgery | 31.2 (31.3) | 22.4 (28.5) | 0.02 |

Values are mean ± standard deviation

Table 5.

Costs and resource use during index and follow-up in propensity matched patients who had lobectomy with or without cryoablation of peripheral intercostal nerve during surgery for postoperative pain control

| Variable | Propensity matched | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lobectomy without cryoablation (n = 266) | Lobectomy with cryoablation (n = 266) | p value | Cost difference between groups | |

| Inpatient, outpatient and total costs through 6 months | ||||

| Index total costs | $43,974 ($41,879) | $38,753 ($29,513) | 0.10 | $5221 |

| Index total costs < $40,000 | 175 (65.8) | 177 (66.5) | 0.93 | |

| Total inpatient costs through 6 months | $50,225 ($57,006) | $44,697 ($34,914) | 0.18 | $5528 |

| Total outpatient costs post index through 6 months | $20,969 ($38,646) | $17,296 ($27,644) | 0.21 | $3673 |

| Total pharmacy costs post index through 6 months | $3110 ($4635) | $3710 ($7133) | 0.25 | − $600 |

| Total inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy costs through 6 months | $74,304 ($73,073) | $65,703 ($45,701) | 0.10 | $8601 |

| Total inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy costs through 6 months for prior opioid users | $80,345 ($75,659) | $65,771 ($46,012) | 0.01 | $14,574 |

| Resource use comparisons | ||||

| % with at least 1 ED visit after surgery through 30 days | 18 (6.8) | 17 (6.4) | 1.0 | |

| % with at least 1 ED visit after surgery through 6 months | 54 (20.3) | 58 (21.8) | 0.75 | |

| % with at least 1 readmit after surgery through 30 days | 25 (9.4) | 30 (11.3) | 0.57 | |

| % with at least 1 readmit after surgery through 6 months | 53 (19.9) | 57 (21.4) | 0.75 | |

| Total inpatient days per patient including index through 6 months | 11.1 (19.1) | 10.4 (14.0) | 0.63 | |

| % with 1 or more outpatient hospital visit after surgery through 6 months | 247 (92.9) | 221 (83.1) | < 0.01 | |

Values are n (%) or mean ± standard deviation

ED emergency department

Index admission costs trended lower for cryoablation patients by $5221 ($38,753 vs. $43,974, p = 0.10). Operating room ($11,159 vs. $15,592, p = 0.02) and normal bed stay ($1740 vs. $2311, p = 0.26) costs drove some of the lower index costs for cryoablation, but supply ($2177 vs. $1603, p = 0.03) costs were higher for cryoablation. Similar lower costs for index admission were observed for those undergoing elective planned procedures ($38,869 vs. $44,868, p = 0.06). Over 6 months of follow-up, cryoablation had a $8601 lower cumulative cost ($65,703 vs. $74,304, p = 0.10). Those with prior opioid use showed $14,574 costs savings with cryoablation ($65,771 vs. $80,345, p = 0.01) over the 6-month period.

Discussion

Our results suggest that cryoablation during lobectomy for the treatment of postoperative pain may have some advantages over SOC alone. Cryoablation is performed by the surgeon intraoperatively by freezing intercostal nerves during the procedure. The adjunctive ablation induces cell damage and temporarily disrupts nerve conduction, while axons regenerate. This allows for a pain-free period promoting complete rapid recovery and reduces the risk for pain-related complications. Some research has expressed a concern for permanent nerve injury and other adverse events associated with cryoanalgesia [14, 15]. We did not find a difference in adverse events between groups, suggesting cryoablation was safe in this cohort of patients; however, admittedly, this data set did not allow as detailed a description of adverse events as prospective studies.

In follow-up, opioid use was 26% lower for the cryoablation group 3 months post surgery suggesting better pain control. Other surgical studies with both adults [12, 16] and adolescents [11] have observed similar results. A comparable reduction in opioid use was found in those who were prior opioid users before surgery as well as those who were classified as chronic opioid users post surgery. Although we were not able to collect pain scores in patients in the current study, our clinical results are consistent with recent studies in patients with lung cancer undergoing cryoablation that found reductions in hospital patient pain and postsurgery opioid use [17, 18]. Since opioid use was estimated on the basis of refill prescription amounts and not actual usage, the true reduction of opioid use after surgery may have been underestimated.

Although not measured in the current study, a potential reduction in patient pain could explain why patients in the cryoablation group were discharged 1.3 days sooner, and subsequent index hospital treatment costs were lower ($5221). Hospital cost center differences were observed during the index visit for bed stay, ICU, and pharmacy costs contributing to the lower index stay costs for cryoablation. Although epidural usage was not available for the study, and SOC would be different amongst hospitals in the study, it is possible that some of the cost savings during the index visit were impacted by reduced epidural use. However, claims data used in this study did not allow us to assess this.

The hospital economic findings in the current study suggest that cryoablation allows hospitals to purchase the cryoablation device for postsurgical pain treatment without incremental reimbursement, and cost savings obtained during the index stay appear to offset the expense of the cryoablation device. These results mirror other economic study results with cryoablation during surgery demonstrating lower hospital index costs [17, 19]. Reduced ALOS in the current study with cryoablation would have expediated bed turnover and allowed more procedures to be performed for hospitals concerned with procedural volumes.

In addition to lower index costs for cryoablation patients, total healthcare costs through 6 months follow-up were $8601 lower for cryoablation driven by fewer inpatient and outpatient hospital visits. Those who were prior opioid users before surgery had an even bigger healthcare costs savings over the 6 months following surgery ($14,574). Cryoablation in this study impacted both index and long-term healthcare costs positively. These results are important given the challenge of hospitals and payors to support the incremental cost of ancillary procedures added to primary procedure to improve outcomes.

This analysis is subject to several limitations associated with retrospective studies including selection bias, consistency in data entry between hospitals included in the study, even with the most robust analysis. Several variables were matched, but cancer stage was not available and could have impacted patient severity. One of the primary outcomes in the study, ALOS, should be interpreted with caution, given that some institutions use different protocols when determining when to send patients home (home caregiver available, actual pain reduction, mobility, etc.), but less is a critical metric for hospital administrators. Thirdly, although prescription refills dosage was captured, it is possible that patient’s actual dosage taken was different than refill amounts, impacting results. Fourthly, this study did not compare surgical approach and impact on outcomes. Since groups were propensity matched, it is unlikely approach had an impact, but this cannot be completely ruled out. A fifth limitation, SOC was not controlled for, and it is possible that differences in SOC treatments impacted results (different gabapentin and epidural use, etc.). A sixth limitation was the small amount of adverse event data available. Key adverse events were captured, but some events were not available such as neuropathy, and are better assessed in prospective studies. Lastly, these results were in patients who mostly used opioids prior to surgery, and the results may be less generalizable in opioid-naïve patients.

Conclusion

Patients undergoing lobectomy with cryoablation demonstrated a significant reduction in opioid use postoperatively and fewer postoperative hospital visits. The lower costs during the index procedure combined with improved outcomes suggests the addition of cryoablation during surgery may be cost-effective and should be considered for use in thoracic surgery given its benefit. Additional randomized studies should be completed to confirm these findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Yazid Barhoush and Emily Achter. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Daniel L Miller, Jacob Hutchins, John P. Kuckelman and Michael A. Ferguson. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Funding resources were acquired by Michael A Ferguson.

Funding

Sponsorship for this study and Rapid Service Fee were funded by AtriCure.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because public data sets were aggregated by STATinMED and licensed for the study.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Daniel L. Miller: AtriCure Speakers Bureau. Jacob Hutchins: AtriCure Speakers Bureau. Michael A. Ferguson: AtriCure Employee. John P. Kuckelman, Yazid Barhoush and Emily Achter have nothing to disclose.

Ethics Approval

Data were de-identified, and data use complied with the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) for the privacy and security of protected health information. Since this study used retrospective data, initially available in the public and anonymized the study did not meet Health and Human Service Services definition as human research (as defined in 45 CFR 46.102) and was exempt from IRB review.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Presented at the AATS International Thoracic Surgical Oncology Summit Annual Meeting on September 28, 2024, in New York, NY.

References

- 1.Potter AL, Puttaraju T, Sulit JC, et al. Assessing the number of annual lung cancer resections performed in the United States. Shanghai Chest. 2023;7:2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bendixen M, Jørgensen OD, Kronborg C, Andersen C, Licht PB. Postoperative pain and quality of life after lobectomy via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or anterolateral thoracotomy for early-stage lung cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(6):836–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei C, Gong R, Zhang J, Sunzi K, Xu N, Shi Q. Pain experience of lung cancer patients during home recovery after surgery: a qualitative descriptive study. Cancer Med. 2023;12(19):20212–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schug SA, Bruce J. Risk stratification for the development of chronic postsurgical pain. Pain Rep. 2017;2(6):e627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guerra-Londono CE, Privorotskiy A, Cozowicz C, et al. Assessment of intercostal nerve block analgesia for thoracic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2133394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freise H, Van Aken HK. Risks and benefits of thoracic epidural anesthesia. Br J Anaest. 2011;107:859–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gramigni E, Bracco D, Carli F. Epidural analgesia and postoperative orthostatic haemodynamic changes: observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30:398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barnard D. The effects of extreme cold on sensory nerves. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1980;62:180–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka A, Al-Rstum Z, Leonard SD, et al. Intraoperative intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia improves pain control after descending and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repairs. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;109:249–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morikawa N, Laferriere N, Koo S, Johnson S, Woo R, Puapong D. Cryoanalgesia in patients undergoing Nuss repair of pectus excavatum: technique modification and early results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2018;28:1148–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graves CE, Moyer J, Zobel MJ, et al. Intraoperative intercostal nerve cryoablation during the Nuss procedure reduces length of stay and opioid requirement: a randomized clinical trial. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54:2250–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pourak K, Kubiak R, Arivoli K, et al. Impact of cryoablation on operative outcomes in thoracotomy patients. Interdiscip Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2024;38(2):ivae023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek S, Park SH, Won E, Park YR, Kim HJ. Propensity score matching: a conceptual review for radiology researchers. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16:286–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sztain JF, Gabriel RA, Said ET. Thoracic epidurals are associated with decreased opioid consumption compared to surgical infiltration of liposomal bupivacaine following video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for lobectomy: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:694–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medina M, Foiles SR, Francois M, et al. Comparison of cost and outcomes in patients receiving thoracic epidural versus liposomal bupivacaine for video-assisted thoracoscopic pulmonary resection. Am J Surg. 2019;217:520–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Connor LA, Houseman B, Cook T, Quinn CC. Intercostal cryonerve block versus elastomeric infusion pump for postoperative analgesia following surgical stabilization of traumatic rib fractures. Injury. 2023;54(11): 111053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Connor LA, Dua A, Orhurhu V, Hoepp LM, Quinn CC. Opioid requirements after intercostal cryoanalgesia in thoracic surgery. J Surg Res. 2022;274:232–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khanbhai M, Yap KH, Mohamed S, Dunning J. Is cryoanalgesia effective for post-thoracotomy pain? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18:202–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauman ZM, Loftus J, Raposo-Hadley A, et al. Surgical stabilization of rib fractures combined with intercostal nerve cryoablation proves to be more cost effective by reducing hospital length of stay and narcotics. Injury. 2021;52(5):1128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because public data sets were aggregated by STATinMED and licensed for the study.