Abstract

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) is a highly heterogeneous disease, necessitating the discovery of novel biomarkers to enhance individualized treatment approaches. Recent research has shown the significant involvement of ubiquitin-related genes (UbRGs) in the progression of LIHC. However, the prognostic value of UbRGs in LIHC has not been investigated. In this study, the mRNA expression profiles and clinical data were obtained from public databases of LIHC patients. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator Cox regression model was employed to construct a multigene signature in the TCGA cohort. Our results showed that a twelve UbRGs signature was developed to categorize patients into two risk groups, with significant differences in expression between LIHC and normal tissues. Patients in the high-risk group exhibited significantly reduced overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival compared to those in the low-risk group. The risk score was identified as an independent predictor for OS in multivariate Cox regression analyses. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis confirmed the predictive capacity of the signature. Functional analysis revealed enrichment of immune-related pathways and differences in immune status between the two risk groups. The risk score was correlated with 35 transcription factors and 26 eRNA enhancers, and positively associated with tumor mutation burden. Patients in the high-risk group demonstrated decreased sensitivity to targeted and chemotherapeutic drugs than those in the low-risk group. In conclusion, our study identified a twelve UbRGs signature that may serve as a prognostic predictor for LIHC patients and and provide valuable insights for cancer treatment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-01768-0.

Keywords: Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin-related gene pair, Overall survival, Functional analysis, Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) is the most common malignant tumor, ranking sixth in terms of incidence among malignancies and being the fourth leading cause of tumor-related death worldwide. Despite being diagnosed with LIHC, patients often face a bleak prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of only 18%, second only to pancreatic cancer [1]. This is due to its high invasive rate, postoperative recurrence rate, and metastasis rate [2]. Furthermore, considering the limited treatment strategies for LIHC, the therapeutic effect in most patients of LIHC remains unsatisfactory, with notable variations among individuals [3]. Hence, there is an urgent need for the identification of new biomarkers to provide guidance for therapeutic options and to enhance the clinical outcomes of patients suffering from LIHC.

Recently, it has been discovered that the epigenetic regulation of ubiquitination (Ub) has a significant impact on the risk of tumors. Ub is a prevalent post-translational protein modification that is typically facilitated by ubiquitin activating enzymes (E1s), ubiquitin binding enzymes (E2s), ubiquitin ligase (E3s), and deubiquiting enzymes (DUB) [4]. The ubiquitin pathway is intricately linked to the incidence and progression of tumors, encompassing aspects such as cell cycle, p53 activation, DNA damage repair, and more. Targeting the ubiquitin pathway has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for cancer patients [5]. Molecularly targeted drugs and small molecule inhibitors of ubiquitination-related enzymes have been utilized in the clinical treatment of cancer [6]. The use of Olozomib, isazomide, and Bortezomib has yielded notable therapeutic outcomes. In recent years, Scholars have used URGs to predict the immune response to cancer, including lung adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer. The prognostic signature based on URGs accurately predicts immune cell infiltration, tumor mutation burden (TMB) within the tumor microenvironment (TME), and the effectiveness of immunotherapy for cancer treatment [7]. Several studies have found a link between URGs and the initiation and development of HCC. However, the role of URGs in HCC has not been thoroughly examined [8, 9].

Here, we conducted a systematic study on the function of ubiquitin-related genes (UbRGs) in LIHC using the TCGA datasets to identify key UbRGs that had a distinct correlation with the outcomes of LIHC patients, established a prognostic signature based on six ubiquitin-related gene pairs (UbRGPs), and further analyzed its performance in predicting transcription factors (TFs) and eRNA enhancers, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and immune infiltration as well as drug sensitivity.

Materials and methods

TCGA and UbRGs data collection

The detailed workflow is presented in Fig. 1. The data, including the transcriptome profile, somatic cell mutation, and clinical characteristics of LIHC patients, was all obtained from the TCGA database. The TCGA-LIHC cohort was composed of 50 normal patients and 374 LIHC patients for the purpose of gene differential expression analysis. Four patients who lacked clinical pathological data or overall survival (OS) were excluded from this study. Furthermore, we employed the "caret" package to randomly partition 370 LIHC patients in the TCGA queue into two groups, namely the test and training sets. The training set comprises 185 patients for the purpose of constructing prognostic features, whereas the testing set consists of 185 patients for internal validation. The clinical pathological data of the queue is presented in Supplementary Table S1, revealing that the training and testing queues exhibit homogeneity.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the study

From the iUUCD 2.0 database, a total of 1393 UbRGs were retrieved [10], and 1307 mRNA expression profiles of UbRGs were extracted from the TCGA-LIHC Transcriptome database, which were correlated with LIHC.

Construction of differentially expressed UbRGPs

Acquisition of Ubiquitin-Related Gene Expression Data: Gene expression data was processed using the R package “limma.” For genes with multiple expression values, the mean expression value was calculated. Genes with expression values less than or equal to 0 were excluded. A total of 1307 UbRGs were extracted from the gene expression data for further analysis.

Identification of UbRG modules associated with tumor tissue using WGCNA: The R package “WGCNA” was used to perform hierarchical clustering analysis on the data. To minimize discrepancies in value ranges, the log2 transformation was applied. Outlier samples were removed by setting the cluster height to 20,000 during hierarchical clustering. A soft threshold of 6, a minimum module size of 50 genes, and a cutting depth of 2 were selected to identify gene modules from the topological overlap matrix (TOM). The first principal component of each module was used as the module eigengene, and the correlation between module eigengenes and clinical phenotypes (e.g., tumor status) was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficients.

Pairing of gene modules and screening of gene pairs with relative expression levels within a certain range (20–80%): Genes within the selected gene modules were paired, and the expression levels of each gene pair were compared across all samples. The gene with the higher expression level in each pair was marked as 1, and the other as 0 [11]. A total of 1848 gene pairs met the screening criteria, defined as having relative expression ratios between 20 and 80% (based on the proportion of 1 in all samples).

Establishment and evaluation of UbRGPs-related prognostic signature

Among 374 tumor patients, 4 were excluded due to missing clinical information, leaving 370 patients for predictive model building and validation. These 370 patients were randomly divided into test and validation sets in a 1:1 ratio. Variable screening and model building were performed using the test set. From 1848 gene pairs, 36 were identified as significantly associated with overall survival (OS) using univariate Cox regression (p < 0.001). These 36 gene pairs were included in a least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO)-Cox proportional hazards model. After 1000 iterations and tenfold cross-validation, the penalty parameter lambda that minimized the partial likelihood deviance was determined to be 0.08312316. Ultimately, LASSO selected 12 significant gene pairs. From these, 12 gene pairs were identified, and multivariate Cox regression along with bidirectional stepwise regression were used to select the 6 most biologically significant gene pairs (p < 0.05). A final optimal risk prediction model was fitted. The risk scores for both the training and validation sets were calculated using the optimal Cox risk model, and the samples were classified into high-risk and low-risk groups based on the median score. The survival curves of the high-risk and low-risk groups were compared using the logrank test, and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the training and test sets were calculated to evaluate the predictive performance of the model [12].

Regarding the formula for the risk score in this context, it is calculated as:

where:

Coefj is the coefficient for the j-th gene from the Cox model.

Xj is the expression value of the j-th gene for the sample.

Construction of calibration curves and nomogram

The survival probability of individuals can be evaluated using a nomogram, which was constructed by integrating risk scores and other clinical pathological information through the "RMS" package. The survival probability of each patient is determined by the total score of each factor [13]. Calibration curves were utilized to assess the consistency between the actual and anticipated survival. Furthermore, the predictive survival evaluation of the nomogram was assessed using ROC.

Correlation analysis of transcription factors (TFs) and eRNA enhancers

A total of TFs and eRNA enhancers were from the human tissue-specific enhancer database (TiED, https://lcbb.swjtu.edu.cn/TiED). The correlation was observed between the UbRGs-Related Prognostic Signature genes and TFs, as well as between these genes and eRNA enhancers. The R packages "dplyr," "pheatmap," "reshap2," "ggpubr," and "ggalluvian" were utilized for the analysis. The correlation coefficient p-value was set at 0.5, and the correlation test p-value was set at 0.001 for the filtering condition.

A total of 1369 TFs from the TiED database were included in the analysis. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between these TFs and 12 signature genes, retaining TF-gene pairs with β > 0.5 and p < 0.001.

A total of 123 significant TF-gene pairs were identified. From the TiED database, 1584 enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) were included in the analysis. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between these eRNAs and 12 signature genes, retaining eRNA-gene pairs with β > 0.5 and p < 0.001. A total of 63 significant eRNA-gene pairs were identified.

Functional enrichment analysis

To gain a deeper comprehension of the carcinogenesis of mRNA, the "ClusterProfiler" package (version 3.18.0) in R was utilized to enhance the KEGG pathway. We utilized the ggplot2 package in R software to generate a boxplot. The R software’s "heatmap" package was utilized to generate the heatmap. GSEA was performed to analyze differentially expressed genes between the high-risk and low-risk groups. The analysis referenced the c2.cp.kegg.Hs.symbols.gmt gene set file, filtering out genes with an average expression of less than 0.5. The minimum gene set size was set to 15, the maximum gene set size to 500, and the significance threshold for pathways was set to 0.05.

Immune infiltration analysis in the TME

To investigate immunocyte infiltration in the TME, the CIBERSORT R-pack was used to analyze the immune infiltration values of samples in low- and high- risk groups. The immunocyte infiltration between high-risk and low-risk groups was displayed by heatmap, and a Wilcoxon sign rank test was used to analyze the differences. Comparing the immune related functions between the two groups was evaluated using "GSVA," "GSEABase," "ggpubr," and "reshappe2" R packages, and comparison of immune checkpoint differences was analyzed using "reshappe2, " "ggplot2," and "ggpubr" R packages.

Analysis of tumor mutation burden (TMB)

The data was analyzed using various R packages such as "survival," "caret," "glmnet," "survivor," and "timeROC" to perform TMB analysis. The TMB difference between high-risk and low-risk groups was analyzed using the "ggpubr" and "reshappe2" R packages. The R-packages "survival" and "survivor" were utilized to analyze the survival of TMB.

Analysis of drug sensitivity

The R packages "oncoPredict" and "parallel" were utilized to analyze the differential expression of high-risk and low-risk groups in drug sensitivity. We used "ggplot2" and "ggpubr" to create a box diagram. The Wilcoxon sign rank test was used to analyze the differences among drugs.

Statistical analysis

R software (version 4.1.3), Perl language packages, and GraphPad Prism software (version 8) were used for all statistical analyses. The OS and progression-free survival (PFS) differences between the various groups were compared using the Kaplan–Meier analysis with the log-rank test. Cox regression analyses were conducted on both univariate and multivariate to identify independent predictors of OS. All statistical results with p < 0.05 were deemed asstatistically significant.

Results

Construction of differentially expressed UbRGPs in LIHC

To construct the differentially expressed UbRGPs, we built a co-expression network of DEGs in 1307 UbRGs obtained from the TCGA-LIHC Transcriptome database and subsequently identified the co-expression genes of expression set modules that exhibit a significant correlation with clinical traits. A scale-free network was constructed using a soft threshold of β = 12 (R2 = 0.85) (Fig. 2A). All the genes were categorized into co-expression modules, each containing 50 distinct genes, and illustrated with different colors (Fig. 2B). We conducted plotting of the eigenvector clustering module (Fig. 2C) and gathered the MEbrown module that had the lowest p-value (Fig. 2D, p = 0.63*4E−48). Afterward, we assembled UBRGPs. Figure 2E shows the module membership in the brown module versus gene significance. Finally, the differentially expressed UbRGPs (0 or 1 frequency between 20 and 80%) were established for further analysis. To conclude, the differential expression of UbRGs was constructed to establish UBRGPs.

Fig. 2.

WGCNA co-expression network analysis. A Analysis of the scale-free index and the mean connectivity for different soft-threshold powers. B Dendrogram of all differentially expressed genes clustered according to the measurement of dissimilarity. The color band illustrates the outcomes of the automatic single-block analysis. C Clustering of modular eigenvectors. D Correlation between modules and clinical trait according to Pearson correlation. E The module membership in brown module versus gene significance

Construction of the prognostic signature of UbRGPs in LIHC

To generate the prognostic signature of UbRGPs in LIHC, a prognostic model was formed by integrating the previously mentioned UBRGPs and TCGA-LIHC survival data and utilizing LASSO Cox regression analysis. The TCGA cohort was randomly divided into a testing set (n = 185) and a training set (n = 185). In the training set, thirty-six UbRGPs were found to be correlated with OS when the criterion of p < 0.001 was considered. The forest map (Fig. 3A) displays the 95% confidence interval (CI) and hazard ratio (HR) of each prognosis-related UbRGP, signifying that the majority of these gene pairs are risk and protective factors. Based on the optimal values of λ, six UbRGPs were chosen for the stepwise LASSO Cox analysis (Fig. 3B, C). In the end, six UbRGPs were utilized in the construction of the prognostic signature, and the particulars of these gene pairs can be found in Supplementary Table S2. According to the forest map, the WRAP53|CCNF, ESR1|RNFT2, FBXL6|DCAF13, THOC6|CDC20, and FBXW4|SHKBP1 were identified as protective factors with HR < 1, while UBE2T|NSMCE2 was the only risk factor with HR > 1 (Fig. 3, p < 0.05). Through differential analysis of model genes, it was found that the genes WRAP53, CCNF, UBE2T, NSMCE2, RNFT2, FBXL6, DCAF13, FBXW4, SHKBP1, THOC6, and CDC20 were upregulated in tumor samples, while ESR1 was downregulated in tumor samples compared to normal samples (Fig. 3D, E, p < 0.001). In summary, we constructed the prognostic signature of UbRGPs in LIHC and observed significant differences between LIHC and normal tissue.

Fig. 3.

Construction of the Prognostic Signature of UbRGPs. A Prognosis-related UbRGs. B, C LASSO Cox analysis. D, E Differential analysis of model genes. F–I Kaplan–Meier plot of the risk score and OS, PFS. J ROC curves. K–M A scatter diagram of the risk score and survival status distribution. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The risk score was calculated using the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model.The train set was divided into high-risk group (n = 91) and low-risk group (n = 94) based on the median risk score, whereas the test set was classified into high-risk group (n = 97) and low-risk group (n = 88). The Kaplan–Meier curve consistently showed that patients in the high-risk group of OS and PFS had a significantly poorer prognosis than those in the low-risk group (Fig. 3F–I; F: All set, p < 0.001; G:Training set, p < 0.05; H:Testing set, p < 0.001; I: All set, p < 0.001). The prediction accuracy, as evaluated by AUCs, was reported to be 0.740, 0.707, and 0.645 in the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year ROC curves, respectively (Fig. 3J). Additionally, the time-dependent AUC values were calculated (Supplement Fig. 8A). Figure 3K–M depicted a scatter diagram of the risk score and survival status distribution, as well as a heatmap of each patient in the training and testing sets (Fig. 3K–M; K: All set; L: Training set; M: Testing set). It can be inferred that high-risk patients had a higher probability of death earlier than low-risk patients. To conclude, the aforementioned findings demonstrate that the six UbRGPs signature can accurately predict the survival probability of patients with LIHC.

The risk scores were positively associated with poor pathological grading and clinical stage and served as an independent prognostic indicator

The correlation between the signature-based risk scores and clinical parameters such as age, gender, immune score, cluster, and T, N, and TNM stages was examined in the TCGA cohort. Patients in stages Ш and stages II had a higher risk score compared to patients in stages I (Supplementary Figure S1A, p = 1.6E−05 and p = 0.0007). Additionally, patients in stages G4, G3, and G2 had a higher risk score than those in stage G1 (Supplementary Figure S1B, p = 0.00033, p = 5E−07, and p = 0.036), and patients in stages T4, T3, and T2 had a higher risk score than those in stage T1 (Supplementary Figure S1C, p = 0.00059, p = 0.00032, and p = 0.00017). However, there were no differences in terms of N stage, M stage, age, or gender (Supplementary Figure S1D–G, p > 0.05).

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression were analyzed to investigate the effect of the risk score. The results revealed that the risk score had a significant correlation with OS in the univariate Cox regression analysis (HR = 2.884, 95% CI = 1.967–4.229, p < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S1H). Furthermore, multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that the risk score was an independent prognostic indicator (HR = 2.441, 95% CI = 1.580–3.770, p < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S1I). To evaluate the accuracy of the risk score prognostic indicator, the ROC curve was employed, which demonstrated that the risk AUC was 0.740. This outperformed other clinical features such as age, AUC = 0.531; gender, AUC = 0.509; grade, AUC = 0.499; stage, AUC = 0.671 (Supplementary Figure S1J). The accuracy of the risk score in predicting OS was high, as indicated by the results.

The clinical nomogram was established and demonstrated high accuracy in predicting OS

To accurately quantify LIHC, we developed a nomogram that integrates age, gender, stage, and risk score to predict OS. This nomogram enables a more precise assessment of patient risk, facilitating informed decisions regarding future treatment strategies (Fig. 4A). To evaluate the prediction accuracy of the nomogram, we employed a calibration curve that compares observed outcomes with predicted outcomes (C-index = 0.740, 95% CI: 0.687–0.793, Fig. 4B). The area under the curve (AUC) values at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.804, 0.804, and 0.797, respectively (Fig. 4C), meanwhile we still calculate the time-dependent AUC values (Supplementary Fig. 8B). These findings indicate that the risk score serves as an independent prognostic indicator, and the nomogram effectively predicts the prognosis of LIHC patients. Notably, the AUC values in both the TCGA dataset and the validation dataset exceeded 0.7, demonstrating that the new signature has a significant capacity for predicting survival. In addition, compared with the nomogram model that includes risk scores, the nomogram model that only includes age, gender, grade, and stage shows lower accuracy in predicting OS (C-index = 0.690, 95% CI: 0.636–0.743, Supplementary Figure S2); AUC values at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.755, 0.757, and 0.750, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2C), meanwhile we still calculate the time-dependent AUC values (Supplementary Fig. 8C). This novel signature shows potential as an independent prognostic factor and was utilized to evaluate the TCGA dataset of patients diagnosed with LIHC.

Fig. 4.

Nomogram development and validation. A Nomogram to predict the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS. B Calibration curve for the OS nomogram model in LIHC. C ROC curves

Internal functional mechanism investigation related to the prognostic signature

The expression of TFs and eRNA enhancers related to the signature of UbRGs

We conducted an investigation into the association between the expression of the prognostic signature of UBRGs and TFs, as well as eRNA Enhancers. The expression of the prognostic signature of UBRGs was associated with 35 TFs, which include ZNF93, ZNF707, ZNF706, ZNF7, ZNF696, ZNF628, ZNF530, ZNF251, ZNF207, ZNF205, ZBTB17, ZBTB12, YBX1, THAP11, TFAP4, SAFB, MYPOP, MYBL2, MXD3, MTF2, MTERF3, MSANTD3, HSF1, FOXM1, E2F8, E2F7, E2F6, E2F5, E2F4, E2F2, DNTTIP1, DNMT1, CXXC1, CENPA, and ESR1 (Supplementary Figure S2A). Additionally, the prognostic signature of UBRGs was linked to 26 eRNA enhancers, which include ZNF337-AS1, THUMPD3-AS1, TENM3-AS1, STX4, STK3, STEAP1B, RNF139-AS1, PCAT1, NUTM2A-AS1, NBDY, MSH6, LINC01615, LINC00205, FOXO3B, FAM225A, FAM120AOS, EMG1, DCP1A, CHST12, CDKN2B-AS1, CDK6-AS1, AL355574.1, AF279873.3, AC069360.1, AC023403.1, and AC012574.2 (Supplementary Figure S2B).

Functional enrichment analysis related to the prognostic signature

To elucidate the biological pathways associated with the prognostic signature, KEGG pathway analyses were conducted on the high-risk and low-risk groups. We investigated the disparities in biological functions between the two risk groups using Functional Enrichment Analysis. The results of the analysis revealed that the high-risk group exhibited enrichment in various biological processes, including the cell cycle, DNA replication, and hematopoietic cell lineage (Supplementary Figure S3A). In contrast, multiple metabolic-related pathways, such as fatty acid metabolism and drug metabolism via cytochrome P450, were found to be active in the low-risk group (Supplementary Figure S3B). These findings highlight distinct pathophysiological mechanisms underlying LIHC and suggest that this complexity may contribute to the differences in disease progression and patient outcomes.

Immune landscapes related to the signature

Subsequently, to investigate the immune landscape associated with the signature, we performed an analysis of TME cell infiltration characteristics. The tumor infiltrating immune cell heatmap revealed the presence of immune cells in each tumor sample across the two risk groups, which could be observed in Fig. 5A. Differences in the infiltration of certain immune cells between the high-risk and low-risk groups were observed, as illustrated in Fig. 5B. In the high-risk group, there was a lower infiltration of T cells CD4 memory resting, NK cells activated, monocytes, and mast cells resting compared to the low-risk group (Fig. 5B, p < 0.001, p = 0.036, p = 0.006 and p = 0.025). However, there was an increased infiltration of T cells CD4 memory activated and T cells follicular helper in the high-risk group (Fig. 5B, p < 0.001 and p = 0.032). To delve deeper into the correlation between risk scores and immune status, we carried out a differential analysis of immune-related functions and immune checkpoints. The results for B cells, mast cells, neutrophils, Tfh, NK cells, parainflammation, Type_I_IFN_Response, and Type_II_IFN_Response showed a significant difference between the high-risk and low-risk groups (Fig. 5C, p < 0.05). Apart from Tfh, the high-risk group showed lower levels of the other immune-related functions (Fig. 5C, p < 0.05). Significant differences in gene expression of checkpoint molecules, such as CD28, ICOS, TNFRSF9, HAVCR2, and LAG3, were observed between the high-risk and low-risk groups, with higher gene expression in the high-risk group (Fig. 5D, p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001). The results showed clear signs of immunocyte infiltration in two groups, and a correlation was observed between the tumor immune microenvironment and the risk score.

Fig. 5.

Immune landscapes related to the prognostic signature. A, B Immune cell infiltration analysis in the two risk groups. C Immune-related function analysis in the two risk groups. D Expression level of immune checkpoints in the two risk groups. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

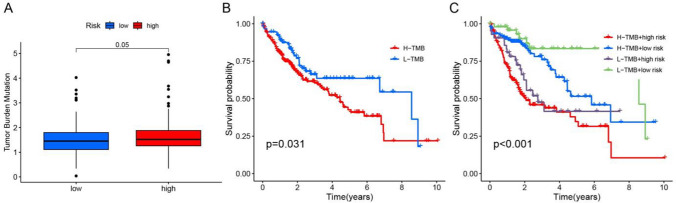

TMB related to the prognostic signature

The analysis of somatic mutations in both low-risk and high-risk groups revealed that the TMB of the high-risk group was significantly higher than that of the low-risk group (Fig. 6A, p = 0.05), and patients with high TMB had a shorter OS (Fig. 6B, p = 0.031). To conduct a survival analysis, we combined the risk score and TMB and determined that patients in the high-risk group with high TMB mutations had a dismal prognosis (Fig. 6C, p < 0.001). The outcome could potentially serve as a valuable prognostic indicator for LIHC.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of TMB. A Comparison of TMB between the two groups. B Kaplan–Meier plot of TMB and OS. C Kaplan–Meier plot illustrating the relationship between OS and the risk score with TMB

Drug sensitivity analysis related to the prognostic signature

We further explored the correlation between the sensitivity of 74 drugs of chemo- and targeted therapy and the prognostic signature. Patients in the high-risk group displayed reduced sensitivity to SB505124 (Supplementary Figure S4A, p = 2.5E−08), yet they exhibited reduced resistance to 72 other drugs, which included 5-Fluorouracil, Dihydrorotenone, I-BRD9, MK-1775, ML323, Oxaliplatin, Talazoparib, Vinblastine, and YK-4–279 (Supplementary Figure S4B-J, p = 4.5E−09, p = 1.7E−09, p = 1.8E−08, p = 1.7E−08, p = 1.6E−10, p = 2.5E−08, p = 4.3E−08, p = 4.3E−08, and p = 2.1E−09). Fig. S4A–J showed that these drugs are the top nine most significantly correlated drugs that impact prognosis. The results of sensitivity to other drug concentrations were shown in Fig. S4 (Supplementary Figure S4, p < 0.001). These findings imply that the prognostic signature has the potential to predict the sensitivity of chemotherapy and targeted therapy, thereby guiding clinical treatment choices and achieving satisfactory clinical outcomes.

The protein expression of UBRGs significantly increased in LIHC

The Human Protein Atlas was utilized to obtain immunohistochemistry-based antibody-specific staining scores in LIHC, which were classified into four grades: high, medium, low, and undetected (Supplementary Figure S5). The protein expression data correlated with the mRNA results (Fig. 3E), indicating that WRAP53, CCNF, NSMCE2, RNFT2, DCAF13, FBXW4, SHKBP1, THOC6, and CDC20 were highly expressed in LIHC tissues, while their expression was low in normal liver tissues (Supplementary Figure S5). The proteins of ESR1 were highly expressed in LIHC tissues, while the specific reasons for this result still require further exploration, as ESR1 mRNA expression was downregulated. As a result, the aforementioned UBRGs have the potential to serve as prognostic predictors or even treatment targets.

Discussion

LIHC has emerged as one of the most prevalent life-threatening cancers. Given its invasive nature, high rates of recurrence and metastasis, the prognosis and survival of HCC patients continue to be disappointing [14]. Hence, it is crucial to identify novel prognostic and predictive markers. In this study, we examined the characteristics of UbRGs, analyzed their correlation with TFs and eRNA enhancers, explored the correlation between the prognostic signature of UbRGPs and TME and TMB, and predicted the drug sensitivity of chemotherapy and targeted therapy in LIHC.

In recent years, a significant amount of research related to cancer has been conducted, with a focus on a few functional gene profiles that have been identified as playing a significant role in the development and progression of cancer [15, 16]. Several studies have highlighted the significance of ubiquitination-related genes in the development of diverse tumors, including LIHC. In the present study, we developed a prognostic signature comprising six UbRGPs, which include twelve UbRGs (WRAP53, CCNF, UBE2T, NSMCE2, ESR1, RNFT2, FBXL6, DCAF13, FBXW4, SHKBP1, THOC6, and CDC20), to efficiently classify patients with LIHC into low- and high-risk groups within the TCGA cohort. Previous studies have confirmed that these UbRGs are closely associated with the progression of LIHC. WRAP53 is recognized as a prominent tumor driver and plays a diagnostic role in LIHC [17, 18]. UBE2T has been shown to overcome LIHC radioresistance by disrupting the UBE2T-H2AX-CHK1 pathway [19]. NSMCE2 demonstrates increased expression in LIHC samples compared to adjacent non-tumor tissue samples [20]. FBXL6 has been identified as a critical driver of LIHC metastasis, and targeting the TKT-ROS-mTOR-PD-L1/VRK2 axis represents a novel therapeutic approach for patients with metastatic LIHC who express high levels of FBXL6 [21]. Additionally, the FBXL6-HSP90AA1-c-MYC axis may play a significant role in the development of LIHC [22]. Studies have revealed that DCAF13 is frequently overexpressed in LIHC, and this overexpression is strongly associated with poor survival rates among LIHC patients [23]. Knockdown of CCNF in LIHC cell lines has been shown to reduce cell proliferation in vitro, suggesting that CCNF may serve as a potential therapeutic target for LIHC [24]. ESR1 has beenconfirm as a therapeutic target in HCC management [25]. Furthermore, CDC20 protein is highly expressed in liver cancer cells and is associated with P53 mutations [26].

Recently, there has been an increasing focus on the role of enhancers in malignant tumors. It has been confirmed that enhancer proteins regulate tumour proliferation, cell migration, angiogenesis, and apoptosis and are intricately involved in tumor resistance, occurrence, and development. eRNA is an innovative type of lncRNA that substantially contributes to enhancer activity and function [27]. In this study, we identified 35 TFs and 26 eRNA enhancers related to the expression of UbRGs. The aforementioned TFs and eRNA enhancers may serve as a significant factor in predicting prognosis and diagnosis of LIHC.

The microenvironment’s immune-associated cells play a crucial role in the incidence and progression of tumors and have garnered growing importance [28]. In the present study, we utilized the CIBERSORT algorithm to determine the relative abundance of 22 distinct types of immune cells that were present in LIHC samples. Our research indicates that individuals in the high-risk group had a lower infiltration rate of immune cells, indicating that the activation of immune cells may be a positive correlation with a better prognosis.We observed that the high-risk group had a significantly higher infiltration of T cells CD4 memory activated and T cells follicular helper compared to the low-risk group. The significant difference was observed between the two risk groups in B_cells, APC_co_stimulation, mast_cells, neutrophils, Tfh, NK_cells, parainflammation, Type_I_IFN_Response and Type_II_IFN_Response. Recently, new treatment strategies, such as cancer immunosuppressive therapy, have prolonged the lives of patients. Among them, checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have emerged as the first-line treatment option for advanced HCC. In the treatment of advanced HCC and other cancer types, immunotherapeutic methods have increasingly focused on monoclonal antibodies against cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), which lock the immune checkpoint inhibition pathways [29, 30]. In this study, we found that immunological checkpoints, including CTLA-4, PD-1, LAG-3, TIGIT, and so on, exhibited significantly higher levels of expression in the high-risk group when stratified by a novel signature. These checkpoints play crucial roles in suppressing excessive immune responses, maintaining self-tolerance, and preventing self-damage [31]. Tumors can exploit these immune checkpoint pathways to inhibit anti-tumor immune responses and evade immune surveillance, ultimately leading to tumor outgrowth and progression [32]. It has been reported that targeting deubiquitinases may enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy by facilitating the degradation of the PD-L1 protein [33–35]. The combination of small molecule inhibitors that directly target either ubiquitinases/deubiquitinases or PD-1/PD-L1 protein adaptors represents a cutting-edge approach for cancer patients [36, 37]. Furthermore, CTLA-4 has been identified as an inhibitory immune checkpoint, and blocking CTLA-4 has been shown to increase anti-tumor responses [38]. Preliminary evidence suggests potential causal relationships between CTLA-4 protein abundance and E3 ubiquitin ligases [39, 40]. In a mouse model of colorectal cancer, blocking HAVCR2 has been shown to enhance anti-tumor responses and promote tumor clearance [41]. Patients exhibiting similar levels of immunological checkpoints may be able to distinguish themselves using the novel signature.

The efficacy of immunotherapy has been shown to be with the TMB. The higher the TMB, the greater the tumor remission effect and clinical benefits that can be achieved through immunotherapy [42]. In our study, it was observed that the TMB of the high-risk group was statistically higher than that of the low-risk group, indicating that the HR group had a better response to ICI therapy compared to the low-risk group. Some studies have indicated that certain types of cancer, including non-small-cell lung cancer and colorectal cancer, with high TMB values are typically associated with a poor prognosis [43, 44]. Our study showed that patients with high TMB had a shorter OS, which is consistent with the findings of previous reports. To further investigate the role of TMB in survival analysis, we combined the risk score and TMB and found that the high-risk group with high TMB mutations had the worst prognosis. As a conclusion, our findings confirm that the prognostic score of HCC patients is positively correlated with TMB and can aid in predicting the prognostic risk of patients.

We also observed that the prognostic signature was associated with the sensitivity of 75 drugs. The results demonstrated that patients in the high-risk group displayed greater susceptibility to chemotherapeutic and targeted therapeutic agents, such as 5-Fluorouracil, Oxaliplatin, Talazoparib, and Vinblastine. In contrast, patients in the low-risk group exhibited reduced sensitivity to these drugs. It has been reported that 5-Fluorouracil chemotherapy, in conjunction with lenvatinib and toripalimab, exhibited promising antitumor activity with manageable toxicities in advanced LIHC with extrahepatic metastasis [45]. A randomized, double-blind comparative study suggests that Combined FOLFOX4 (infusions of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) with all-trans retinoic acid is a safe and effective treatment for patients with advanced LIHC and extrahepatic metastasis in eastern China [46]. Furthermore, a biomolecular exploratory, randomized, Phase III trial demonstrated that interventional hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy using infusional fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (HAIC-FO) achieved better survival outcomes than sorafenib in advanced LIHC, even in the presence of a high intrahepatic disease burden [47]. Additionally, an open-label, Phase 2 trial indicated that Talazoparib monotherapy exhibited durable antitumor activity in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair alterations [48].

Currently, there is a lack of comprehensive research on the role of URGs in patients with LIHC. While some previous studies have established the prognostic significance of URGs in specific malignancies, including pancreatic and prostate cancer, further investigation is needed in the context of liver cancer. This research not only validates the prognostic importance of URGs in LIHC but also explores their potential application in immunotherapy. Such findings offer valuable insights for clinicians, aiding in patient risk stratification and the selection of suitable therapeutic strategies. However, our research has several limitations that must be considered. First, the study relied heavily on data obtained from TCGA, where the majority of patients were either White or Asian. Therefore, the application of our findings to patients of other ethnicities should be approached with caution. Second, while we constructed a prognostic signature and validated it using internal datasets, it is important to acknowledge the potential for source bias. As a result, additional clinical cohorts are necessary to further validate our findings. Third, our study focused on RNA levels, suggesting that further investigations at the protein level may be required. To clarify the specific underlying mechanisms, additional in vitro experiments are warranted. Our model is based on twelve specific UbRGs, and the roles of other UbRGs in LIHC biology necessitate further exploration. Nevertheless, this study provides valuable insights for clinicians regarding patient risk stratification and the selection of appropriate therapies.

Conclusions

In this study, we developed a new prognostic model consisting of 12 UbRGs. Our findings demonstrate that this model is significantly correlated with OS in both the test and validation cohorts. This novel model provides valuable insights into predicting the prognosis of LIHC. However, the underlying mechanisms linking UbRGs and tumor immunity in LIHC are still not fully understood and require further investigation.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We would like to give our sincere appreciation to the colleagues for their helpful suggestions on this article.

Author contributions

S.Z. provided Conception and design; X.C., S.L,L.C., S.C. provided Collection and assembly of data; X.C., S.L.,L.C., S.C.,Q.L. provided Data analysis and interpretation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (82103534), Supported by GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515110994, 2021A1515011500).

Data availability

The public data set of this study can be found in the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiuyun Chen and SenLin Li contributed equally.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganesan P, Kulik LM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: new developments. Clin Liver Dis. 2023;27:85–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Deng B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: molecular mechanism, targeted therapy, and biomarkers. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023. 10.1007/s10555-023-10084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange SM, Armstrong LA, Kulathu Y. Deubiquitinases: from mechanisms to their inhibition by small molecules. Mol Cell. 2022;82:15–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han S, Wang R, Zhang Y, et al. The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in tumor invasion and metastasis. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:2292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Q, Zhang W. Progress in anticancer drug development targeting ubiquitination-related factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Cheng S, Liu Y, et al. Gene signature and prognostic value of ubiquitination-related genes in endometrial cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21(1):3. 10.1186/s12957-022-02875-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lv T, Zhang B, Jiang C, et al. USP35 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression by protecting PKM2 from ubiquitination-mediated degradation. Int J Oncol. 2023;63(4):113. 10.3892/ijo.2023.5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Xia P, Yang Z, et al. Cullin-associated and neddylation-dissociated 1 regulate reprogramming of lipid metabolism through SKP1-Cullin-1-F-box(FBXO11) -mediated heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A2/B1 ubiquitination and promote hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transl Med. 2023;13(10): e1443. 10.1002/ctm2.1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou J, Xu Y, Lin S, et al. iUUCD 2.0: an update with rich annotations for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D447–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Cui Y, Diehn M, et al. Development and validation of an individualized immune prognostic signature in early-stage nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obuchowski NA, Bullen JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves: review of methods with applications in diagnostic medicine. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63:07TR01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiang G, Dong X, Xu T, et al. A nomogram for prediction of postoperative pneumonia risk in elderly hip fracture patients. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2020;13:1603–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coffin P, He A. Hepatocellular carcinoma: past and present challenges and progress in molecular classification and precision oncology. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 10.3390/ijms241713274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Porta-Pardo E, Tokheim C, et al. Pan-cancer proteogenomics connects oncogenic drivers to functional states. Cell. 2023;186:3921–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andre F, Filleron T, Kamal M, et al. Genomics to select treatment for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Nature. 2022;610:343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gadelha RB, Machado CB, Pessoa F, et al. The role of WRAP53 in cell homeostasis and carcinogenesis onset. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44:5498–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdelmoety AA, Elhassafy MY, Said R, et al. The role of UCA1 and WRAP53 in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a single-center case-control study. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;9:129–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun J, Zhu Z, Li W, et al. UBE2T-regulated H2AX monoubiquitination induces hepatocellular carcinoma radioresistance by facilitating CHK1 activation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sucularli C. Identification of BRIP1, NSMCE2, ANAPC7, RAD18 and TTL from chromosome segregation gene set associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 2022;268–269:28–36. 10.1016/j.cancergen. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Lin XT, Yu HQ, et al. Elevated FBXL6 expression in hepatocytes activates VRK2-transketolase-ROS-mTOR-mediated immune evasion and liver cancer metastasis in mice. Exp Mol Med. 2023. 10.1038/s12276-023-01060-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shi W, Feng L, Dong S, et al. FBXL6 governs c-MYC to promote hepatocellular carcinoma through ubiquitination and stabilization of HSP90AA1. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cao J, Hou P, Chen J, et al. The overexpression and prognostic role of DCAF13 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1393383911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao D, Li S, Guo H, et al. A predictive model based on the FBXO family reveals the significance of cyclin F in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2024;29(5):202. 10.31083/j.fbl2905202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nie Y, Yan J, Huang X, et al. Dihydrotanshinone I targets ESR1 to induce DNA double-strand breaks and proliferation inhibition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Phytomedicine. 2024;130: 155767. 10.1016/j.phymed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao S, Zhang Y, Lu X, et al. CDC20 regulates the cell proliferation and radiosensitivity of P53 mutant HCC cells through the Bcl-2/Bax pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(13):3608–21. 10.7150/ijbs.64003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Z, Li W. Enhancer RNA: what we know and what we can achieve. Cell Prolif. 2022;55: e13202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, et al. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Dai Z, Wu W, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of immune checkpoints PD-L1 and CTLA-4 in cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen W, Huang Y, Pan W, et al. Strategies for developing PD-1 inhibitors and future directions. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;202: 115113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X, Song X, Li K, et al. FcgammaR-binding is an important functional attribute for immune checkpoint antibodies in cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyck L, Mills KHG. Immune checkpoints and their inhibition in cancer and infectious diseases. Eur J Immunol. 2017;47:765–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mao R, et al. UCHL1 promotes expression of PD-L1 in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2020. 10.1111/cas.14529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burr ML, et al. CMTM6 maintains the expression of PD-L1 and regulates antitumour immunity. Nature. 2017;549:101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mezzadra R, et al. Identification of CMTM6 and CMTM4 as PD-L1 protein regulators. Nature. 2017;549:106–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Horita H, Law A, Hong S, et al. Identifying regulatory posttranslational modifications of PD-L1: a focus on monoubiquitinaton. Neoplasia. 2017;19:346–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature. 2018;553:91–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing R, Gao J, Cui Q, et al. Strategies to improve the antitumor effect of immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 783236. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.783236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stempin CC, Rojas Marquez JD, et al. GRAIL and Otubain-1 arerelated to T cell hyporesponsiveness during trypanosoma cruzi infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(1): e0005307. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson HM, et al. Impaired proteasome function activates GATA3 in T cells and upregulates CTLA-4: relevance for Sezary syndrome. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:249–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang YH, Zhu C, Kondo Y, et al. CEACAM1 regulates TIM-3-mediated tolerance and exhaustion. Nature. 2015;517(7534):386–90. 10.1038/nature13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sha D, Jin Z, Budczies J, et al. Tumor mutational burden as a predictive biomarker in solid tumors. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:1808–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He B, Dong D, She Y, et al. Predicting response to immunotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer using tumor mutational burden radiomic biomarker. J Immunother Cancer. 2020. 10.1136/jitc-2020-000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang H, Liu J, Yang J, et al. A novel tumor mutational burden-based risk model predicts prognosis and correlates with immune infiltration in ovarian cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 943389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guo J, Yu Z, Sun D, et al. Two nanoformulations induce reactive oxygen species and immunogenetic cell death for synergistic chemo-immunotherapy eradicating colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2021;20:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun J, Mao F, Liu C, et al. Combined FOLFOX4 with all-trans retinoic acid versus FOLFOX4 with placebo in treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: a randomized, double-blind comparative study. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lyu N, Wang X, Li JB, et al. Arterial chemotherapy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil versus sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a biomolecular exploratory, randomized, Phase III trial (FOHAIC-1). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:468–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Bono JS, Mehra N, Scagliotti GV, et al. Talazoparib monotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair alterations (TALAPRO-1): an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1250–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The public data set of this study can be found in the TCGA database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).