Abstract

Adult human hearts exhibit limited regenerative capacity. Post-injury cardiomyocyte (CM) loss can lead to myocardial dysfunction and failure. Although neonatal mammalian hearts can regenerate, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain elusive. Herein, comparative transcriptome analyses identify adherens junction protein N-Cadherin as a crucial regulator of CM proliferation/renewal. Its expression correlates positively with mitotic genes and shows an age-dependent reduction. N-Cadherin is upregulated in the neonatal mouse heart following injury, coinciding with increased CM mitotic activities. N-Cadherin knockdown reduces, whereas overexpression increases, the proliferation activity of neonatal mouse CMs and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived CMs. Mechanistically, N-Cadherin binds and stabilizes pro-mitotic transcription regulator β-Catenin, driving CM self-renewal. Targeted N-Cadherin deletion in CMs impedes cardiac regeneration in neonatal mice, leading to excessive scarring. N-Cadherin overexpression, by contrast, promotes regeneration in adult mouse hearts following ischemic injury. N-Cadherin targeting presents a promising avenue for promoting cardiac regeneration and restoring function in injured adult human hearts.

Subject terms: Cardiac regeneration, Cardiovascular diseases

Adult human hearts exhibit restricted regenerative ability, where cardiomyocyte loss leads to dysfunction, while neonatal hearts can regenerate, though the molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here, the authors show that N-cadherin plays a crucial role in driving cardiomyocyte self-renewal by stabilizing β-catenin, representing a unique opportunity to promote cardiac regeneration and restore contractile function in the injured adult heart

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a prevalent and expanding public health concern, impacting over 23 million individuals globally. Despite significant progress has been made over the last few decades in improving the outcomes of cardiovascular diseases like acute coronary syndrome, congenital and valvular heart diseases, the mortality rate of HF remains largely unchanged1–4. The prevalence of HF continues to rise, and the 5-year mortality rate for symptomatic HF remains around 50%, which is worse than many cancers5,6. One of the fundamental reasons underlying the recalcitrant nature of HF is that adult mammalian heart has very limited capacity to regenerate after injury. The damaged cardiomyocytes (CMs), therefore, is replaced by fibrotic tissue, leading to remodeling of the surrounding myocardium, deteriorated contractile function, and ultimately, HF and death.

While the regenerative capacity of adult mammalian heart is limited, it is well-established that some lower vertebrates such as zebrafish and newt can regenerate myocardium throughout life7–9. Importantly, recent studies have revealed that neonatal mouse heart can fully regenerate after cryoinjury, myocardial infarction (MI) or apical resection (AR) of the left ventricle (LV)10–12. The regenerative capacity of the neonatal mouse heart, however, is only transient and declines sharply by 7 days of age10. A recent study by Haubner et al. reported that newborn humans may also have the potential to fully regenerate their hearts after injury13. These data suggest that mammals, including humans, can regenerate their hearts, but this ability is age-dependent and limited to a narrow time window after birth. Identifying the molecular switches triggering CM renewal in neonatal mammalian heart, therefore, could provide the basis for novel therapeutic approaches to regenerate lost myocardium and to restore contractile function in the adult failing heart.

Several signaling molecules/pathways have been shown to stimulate adult rodent heart regeneration by promoting CM proliferation. Neuregulin 1 (NRG1/Nrg1), an EGF-like growth factor binding to ErbB4, and ErbB2 receptors, for example, plays a crucial role in CM proliferation and maturation14,15; the treatment with recombinant NRG1 stimulates CM proliferation in adult mouse hearts, resulting in improved cardiac function after MI14. Yes-associated protein (YAP/Yap1), a transcriptional coactivator downstream of the Hippo pathway, has been shown to enhance CM proliferation, reduce scar size, and preserve cardiac function following MI when genetically overexpressed or activated through mutation of the Hippo pathway protein Sav1 (Salvador homolog1)16,17. A report showed that experimental hypoxia in vivo promotes adult CM proliferation by reducing reactive oxygen species and reactivating CM mitosis18. Extracellular matrix protein Agrin and sarcomere dystrophin glycoprotein complex have been reported to link extracellular biomechanical inputs to Hippo signaling cascade, thereby influencing adult CM proliferation19,20. Recently, Mohamed et al. showed that overexpression of a combination of cell-cycle regulators including cycling-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1), CDK4, cycling B1, and cyclin D1 in post-mitotic adult CMs induces stable proliferation and cytokinesis, leading to significant improvement in cardiac function following MI injury21. Moreover, transient expression of pluripotent factors Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM), has been shown to induce dedifferentiation and proliferation of adult CMs, thereby preserving cardiac function following injury22. However, prolonged expression of OSKM results in cellular reprogramming and cardiac tumor formation22. Taken together, these data suggest that a deeper understanding of the regulatory elements of CM renewal is the key to awakening the latent cardiac regeneration machinery in adult mammalian heart, which could lead to the discovery of a potential cure for HF.

In the present study, exploiting comparative transcriptional analyses in neonatal and adult CMs, we determined that Cdh2, which encodes N-Cadherin, a member of the calcium-dependent cell adhesion protein cadherin superfamily, could contribute critically to CM self-renewal. As a key adhesion molecule in the myocardium, N-Cadherin plays a critical role in maintaining the structural integrity and function of CMs by forming adherens junctions at the intercalated discs, facilitating mechanical coupling, electrical communication, and synchronized contraction of the heart. Germline deletion of N-Cadherin causes embryonic lethality resulting from multiple developmental anomalies including severe cardiovascular defects23. Inducing N-Cadherin deletion in the CMs disrupts cell-cell adherens contacts and destabilization of gap junction, resulting in conduction defects, spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, and premature cardiac death24,25. The functional role of N-Cadherin in regulating CM proliferation and regeneration, however, has never been investigated. Here, we showed that the expression levels of N-Cadherin correlate positively with the regenerative capacity of mouse hearts and that N-Cadherin expression is induced in regenerating mouse myocardium in response to injury. Mechanistic studies revealed that N-Cadherin physically interacts with and stabilizes β-Catenin, a potent pro-mitotic transcriptional factor, thereby augmenting CM proliferation. Importantly, the regenerative capacity of neonatal mice heart (<P7) was completely abolished in mice with cardiac-specific depletion of N-Cadherin, whereas replenishing Cdh2/N-Cadherin in adult mouse heart using AAV boosted de novo CM proliferation and restored cardiac function following MI injury. Taken together, our data suggest a critical yet previously undiscovered role of N-Cadherin in regulating CM renewal and that enhancing N-Cadherin expression/function can be a powerful therapeutic approach in restoring cardiac function following cardiac injury.

Results

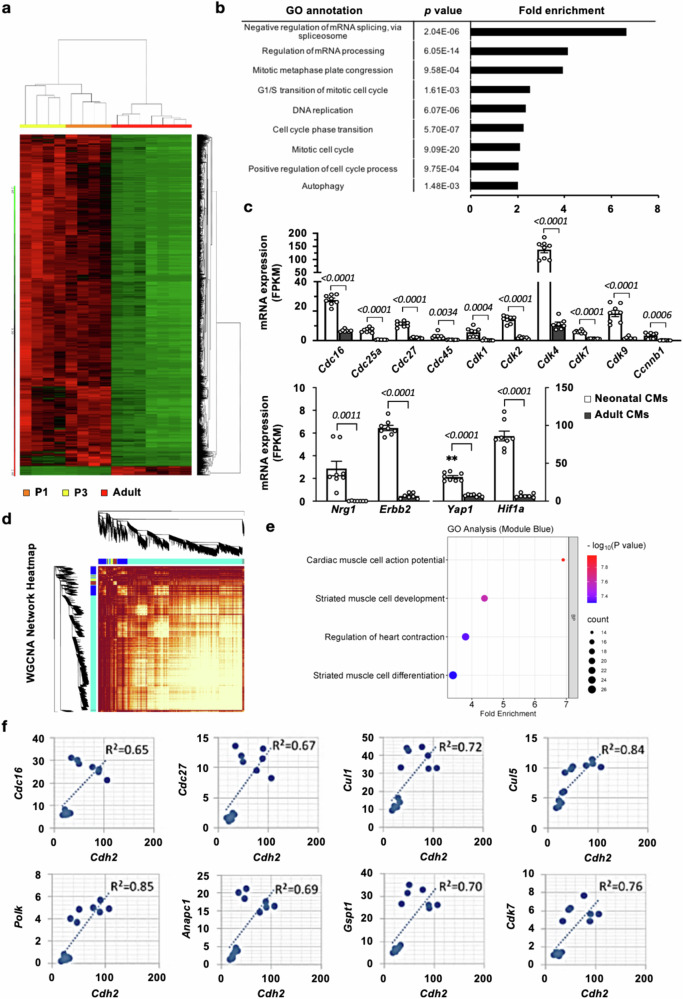

RNA sequencing analyses identified Cdh2 (N-Cadherin) as a potential regulator of cardiac regeneration

As neonatal (<P7), but not adult, mouse CMs are known to fully regenerate the heart in response to injury10, we hypothesized that the differences in transcriptomic profiles between neonatal and adult mouse CMs could serve as a guide to identify the crucial pathways/mediators that regulate CM renewal. To test this hypothesis directly, deep RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) was conducted using the RNA samples from isolated ventricular CMs from neonatal (on postnatal day 1 and 3 [P1 and P3], both n = 4) and adult (8–12 weeks, n = 7) mice. A total of 18,527 mRNAs were detected by paired-end RNA-Seq, where 2895 mRNAs (2822 up and 73 down) were differentially expressed in neonatal vs. adult CMs (Fig. 1a). Consistent with the higher proliferative capacity of neonatal CM, gene ontology (GO) and pathway analyses of the transcripts upregulated in neonatal CMs showed a strong enrichment in genes that are involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA replication, and mitosis (Fig. 1b). Indeed, genes that are essential for cell cycle progression and proliferation including Cdc16, Cdk4, Cdk9, and Ccnb1 were expressed at much higher levels in neonatal, compared with adult, CMs (Fig. 1c). Also consistent with the higher regenerative capacity in neonatal hearts, genes involved in cardiac regeneration, such as Nrg1, Erbb2, Yap1, and Hif1a, were markedly higher in neonatal than in adult CMs (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Identification of Cdh2 (N-Cadherin) as a novel mediator of cardiomyocyte (CM) proliferation/regeneration.

a Heatmap and cluster dendrograms of mRNAs expressed in isolated neonatal (P1 and P3) and adult CMs. b Gene ontology (GO) analysis of transcripts that were significantly upregulated in neonatal CMs revealed a significant enrichment in genes involved in mitosis, cell cycle, and DNA replication, consistent with the higher proliferative activity in neonatal CM. c RNA-Seq analysis revealed that genes involved in cell cycle progression, DNA synthesis, and proliferation (upper panel) and genes known to promote cardiac regeneration (lower panel) were expressed at a markedly higher level in neonatal (results from P1 and P3 neonatal CMs were pooled, n = 8), compared to adult (n = 7), CMs. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. d Network heatmap and cluster dendrograms for the Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) on adult and neonatal CM RNA-Seq data. e Bubble plot and GO analysis of the genes in the blue co-expression module identified by WGCNA. f Cdh2 expression level showed a strong positive correlation with that of cell cycle-related genes in murine CMs. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

To identify potential novel mediators of CM regeneration, pairwise correlations between all identifiable mRNAs in neonatal and adult isolated CM samples were computed, followed by constructing a gene coexpression network through Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). A total of 8 coexpression gene modules were formed and color coded (Fig. 1d)26,27. One of the co-expression modules, labeled in blue, consisted of 584 genes (Supplementary Table 1) that showed significant enrichment in functions related to CM action potential (6.9-fold enrichment, P = 1.1 × 10−8), development (4.9-fold enrichment, P = 1.0 × 10−7) and differentiation (3.4-fold enrichment, P = 4.9 × 10−8, Fig. 1e). Within this coexpression gene module, the expression level of Cdh2, which encodes N-Cadherin, exhibited a strong positive correlation with the genes encoding various cell cycle/proliferation-related proteins including Cdc16, Cdc27, Cul1, Cul5, Polk, Anapc1, Gspt1, and Cdk7 (Fig. 1f). In addition, RNA-Seq data revealed that Cdh2 expression level was highest in P1, reduced by half in P3, and lowest in adult, CMs (Fig. 2a), which is correlated with the age-dependent reduction in proliferative/regeneration capacity of murine CMs. Consistent with the results from transcript analyses, protein expression levels of N-cadherin were markedly higher in the P1 neonatal, compared with P21, and adult, mouse left ventricular (LV) CMs (Fig. 2b). These data, therefore, suggest a potential link between Cdh2 and CM cell proliferation and regeneration.

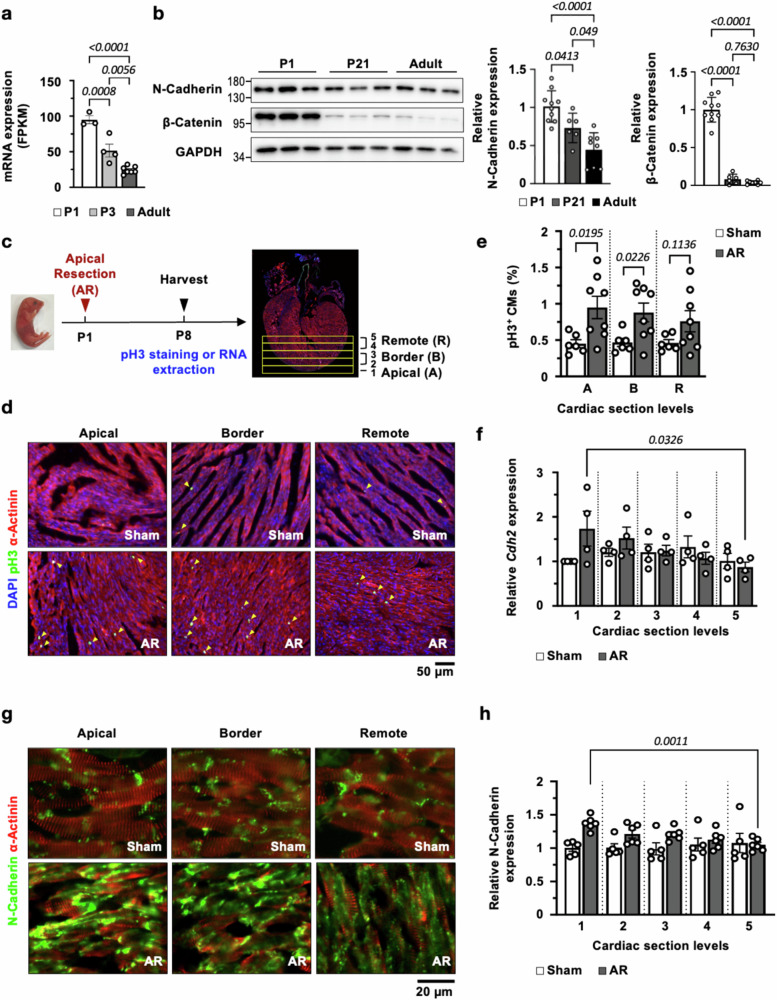

Fig. 2. Cardiac Cdh2 (N-Cadherin) level reduces dramatically beyond the regenerative age window and is upregulated in neonatal heart following injury.

a Cardiac Cdh2 expression level exhibited an age-dependent reduction from P1, P3 to adult CM (n = 3, 4, and 7, respectively). A one-way ANOVA test (p < 0.0001) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. b Immunoblotting showed that N-Cadherin and β-Catenin were significantly higher in neonatal P1 and sharply declined in P21 and adult mouse hearts (n = 10, 6, and 8, respectively). A one-way ANOVA test (p < 0.0001 in relative N-Cadherin and β-Catenin expression) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. c Schematic illustration of cardiac apical resection (AR) in P1 neonatal mice. CMs proliferation (by pH3 staining) and Cdh2 expression levels were assayed on P8 (day 7 post-AR) in apical (1), border (2 and 3) and remote zones (4 and 5). d Immunofluorescence (IF) staining showed a marked increase in pH3+ CMs (arrowheads) in post-resected, compared to sham-operated, neonatal mouse hearts, particularly in the apical and border zones. e Quantification of pH3+ CMs (n = 6 for sham-operated; and n = 8 for AR neonatal mouse hearts). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. f Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) revealed a significant (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.0326) upregulation of Cdh2 in mouse hearts following AR injury, highest in the apical zone and reduced gradually toward the remote zone (n = 4 in each group). g IF staining showed a marked increase in N-Cadherin in apical and border region in post-resected, compared to sham-operated, neonatal mouse hearts. h Quantification of N-Cadherin intensity revealed a significant (one-way ANOVA, p = 0.0011) upregulation of N-Cadherin in mouse hearts following AR injury (n = 5 for sham-operated; and n = 6 for AR neonatal mouse hearts). These Cdh2 and N-Cadherin expression gradients were not observed in the sham-operated heart. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

To further evaluate the relationship between Cdh2/N-Cadherin and cardiac regenerative activity, cardiac AR was conducted in P1 neonatal mouse hearts, followed by assays to quantify CM proliferation and Cdh2 expression 7 days (P8) after surgery (Fig. 2c). As shown in Fig. 2d, e, immunofluorescence (IF) staining revealed a marked increase in phospho-histone H3+ (pH3+) CMs, particularly in the border zone next to the resected cardiac apex, compared to sham-operated hearts, demonstrating increased CM proliferation in neonatal mouse heart in response to cardiac injury10. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR, Fig. 2f) and IF staining (Fig. 2g) of serial cardiac sections (from apex to remote zones, scheme shown in Fig. 2c) revealed a significant upregulation of N-Cadherin transcript (Cdh2) and protein in the post-resection hearts, highest in the apical zone and declined gradually toward the remote zone. This Cdh2 expression gradient, however, was not observed in the sham-operated mouse heart (p < 0.05 by ANOVA, Fig. 2f–h). Taken together, the observed temporal-spatial correlation between cardiac Cdh2 gene/protein expression and age-dependent regenerative capacity/proliferation-related gene expression suggest a potential role of Cdh2/N-Cadherin in regulating cardiac muscle regeneration.

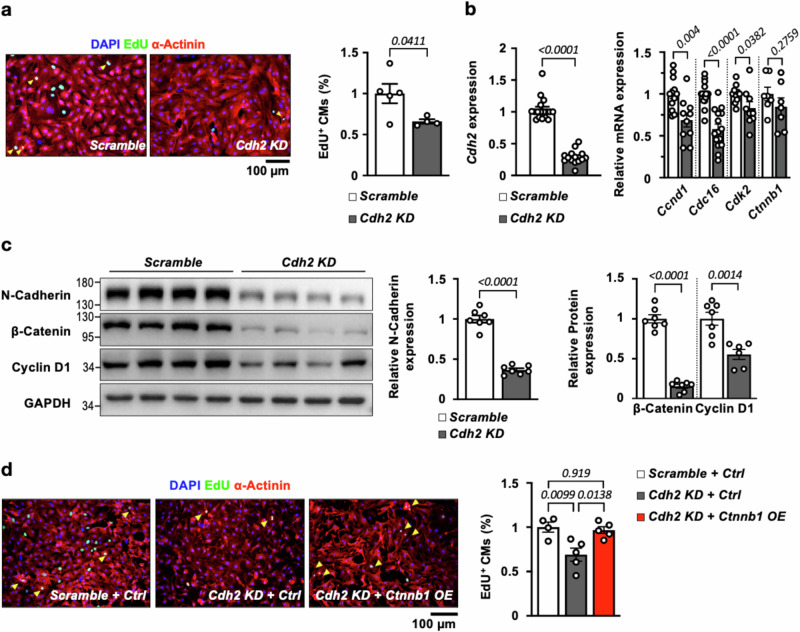

N-Cadherin promotes CM proliferation through post-transcriptional regulation of β-Catenin

Consistent with the hypothesis that Cdh2/N-Cadherin is involved in the regulation of CM proliferation/regeneration, knocking down Cdh2 in neonatal mouse CMs led to significantly reduced CM proliferation (Fig. 3a, assayed by EdU labeling), which was accompanied by a reduction in cell-cycle related genes (Ccnd1, Cdc16, and Cdk2) (Fig. 3b) and protein (Cyclin D1, encoded by Ccnd1, Fig. 3c). Furthermore, forced expression of Cdh2 in neonatal mouse CMs using adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying Cdh2 gene led to a marked increase in proliferative activity (Fig. S1a) and upregulation of cell-cycle related genes and protein (Fig. S1b, c). Collectively, these results clearly indicate that Cdh2/N-Cadherin is both necessary and sufficient for maintaining/enhancing the mitotic activities of CMs.

Fig. 3. Depletion of Cdh2/N-Cadherin reduces the proliferative capacity of neonatal CMs.

a EdU labeling experiments revealed that the proliferative capacity was significantly reduced in Cdh2 KD (n = 4), compared to Scramble control (n = 5), neonatal mouse CMs. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. b qRT-PCR confirmed a ~70% reduction of Cdh2 in neonatal CMs treated with Cdh2-targeting shRNA (left panel, n = 17 for Scramble; and n = 14 for Cdh2 KD neonatal mouse CMs). The expression levels of cell-cycle related genes, including Ccnd1 (n = 12 for Scramble; and n = 10 for Cdh2 KD neonatal mouse CMs), Cdc16 (n = 18 for Scramble; and n = 15 for Cdh2 KD neonatal mouse CMs), and Cdk2 (n = 11 for Scramble; and n = 9 for Cdh2 KD neonatal mouse CMs) were markedly reduced in Cdh2 KD, compared to controls (right panel). Notably, Ctnnb1 (n = 7 in each group), which encodes β-Catenin, was not affected by Cdh2 KD. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. c Immunoblotting revealed that the protein expression of N-Cadherin (n = 7 in each group), β-Catenin (n = 7 in each group), and cell-cycle protein Cyclin D1 (n = 7 for Scramble; and n = 6 for Cdh2 KD CMs) was dramatically reduced in Cdh2 KD, compared to Scramble control, CMs. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. d Reduced proliferative capacity in Cdh2 KD neonatal CMs could be restored by Ctnnb1 OE (n = 4 for Scramble + Ctrl; n = 5 for Cdh2 KD + Ctrl; and n = 5 for Cdh2 KD + Ctnnb1 OE neonatal CMs). A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0057) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

Previous reports showed that cadherin-mediated cell-cell connection may control cell proliferation by regulating the Hippo pathway28. Because Yap is a pro-mitotic transcription co-activator and a highly conserved core component of the Hippo pathway, we then determined if the pro-mitotic effects of N-Cadherin in CMs is mediated through Hippo/Yap cascade. As shown in Fig. S1c, immunoblotting showed that neither p-Yap (Ser127) nor total Yap was changed in neonatal CM with Cdh2 overexpression. In addition, knocking down Cdh2 in neonatal CMs did not affect the nuclear localization of activated Yap (Fig. S2). The observation that changes in Cdh2/N-Cadherin levels did not affect the expression or nuclear localization of Yap in CMs suggest that Cdh2/N-Cadherin is unlikely to regulate CM mitotic activity through the Hippo pathway.

Next, we went on to determine if the pro-mitotic effects of N-Cadherin in CMs is linked to another well-known pro-mitotic factor β-Catenin, which binds to the cytoplasmic domain of N-cadherin. β-Catenin is a transcriptional regulator known to promote cell proliferation29,30 and control the expression of Ccnd1/Cyclin D1, one of the cell cycle protein genes regulated by Cdh2/N-Cadherin observed in our experiments (Fig. 3b, c, Fig. S1b, c). As shown in Fig. 2b, β-Catenin protein expression levels were markedly reduced in P21 and adult, compared to P1 neonatal, mouse heart, similar to the age-dependent downregulation of N-Cadherin in the mouse heart. In addition, knocking down Cdh2 led to a marked reduction (Fig. 3c), whereas forced expression of Cdh2 led to an increase (Fig. S1c), in β-Catenin protein levels in neonatal CMs. However, the expression levels of Ctnnb1, the transcript encoding β-Catenin, did not show a discernible change with Cdh2 knockdown or overexpression in neonatal CMs (Fig. 3b, Fig. S1b). These findings suggest that β-Catenin expression in CMs is regulated by N-Cadherin post-transcriptionally.

To determine if activated β-Catenin signaling accounts for the pro-mitotic activity of Cdh2/N-Cadherin in CMs, a β-Catenin inhibitor, KYA1797K, which directly targets the destruction complex and induces β-Catenin degradation31, was used to treat neonatal CMs with Cdh2 overexpression. As shown in Fig. S1d, treatment with KYA1979K abolished the pro-mitotic effects of forced Cdh2 expression in neonatal CMs completely. In addition, depletion of Ctnnb1/β-Catenin abrogated the enhanced CM proliferative capacity induced by Cdh2 overexpression (Fig. S1e), whereas forced expression of Ctnnb1/β-Catenin restored the CM proliferation activity repressed by Cdh2 knockdown (Fig. 3d). Taken together, these results demonstrate that Cdh2/N-Cadherin modulates CM proliferative activity by controlling β-Catenin expression, likely through post-transcriptional regulation.

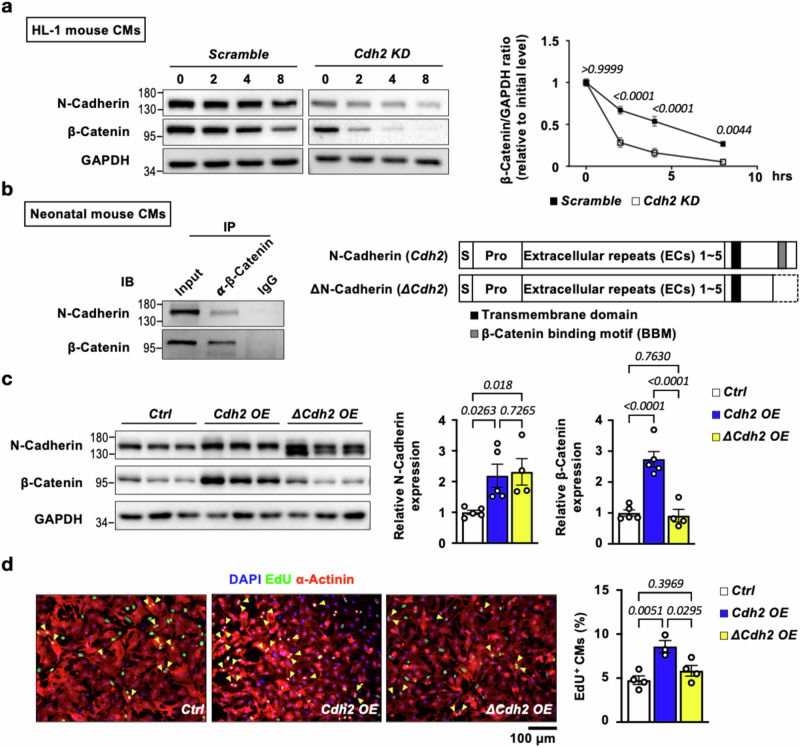

N-Cadherin stabilizes β-Catenin with its C-terminal β-Catenin binding motif (BBM), thereby driving CM proliferation through enhanced β-Catenin signaling activity

Cellular levels of β-Catenin can be controlled through cadherin-mediated sequestration into membrane-bound and free cytosolic pools. The cytosolic β-Catenin can be further stabilized via cadherin-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway, facilitating its translocation to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, β-Catenin can activate downstream transcriptional programs in response to Wnt signaling32 suggesting that cardiac N-Cadherin could bind and sequester/stabilize β-Catenin, leading to an increased β-Catenin pool poised for activation. Consistent with this hypothesis, a cycloheximide pulse chase assay performed in HL-1 mouse CMs with knockdown or overexpression of Cdh2/N-Cadherin (Fig. S3), revealing that the protein half-life of β-Catenin was significantly reduced (from ~4.5 h to ~1.5 h) in HL-1 CMs with Cdh2 depletion (Fig. 4a). Also consistent with the notion that N-Cadherin binds with β-Catenin, co-immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed the physical interaction between N-Cadherin and β-Catenin (Fig. 4b) in neonatal mouse CMs. IF staining also revealed strong co-localization of N-Cadherin with β-Catenin at the cell membrane in neonatal mouse CMs (Fig. 5a, b). As N-Cadherin is known to interact with β-Catenin via a β-Catenin binding motif (BBM) at its C-terminus, we generated expression constructs of WT (Cdh2) and BBM-truncated mutant N-Cadherin (ΔCdh2) (Fig. 4b) to determine if BBM is required for N-Cadherin-mediated β-Catenin regulation and CM proliferation. In line with the results presented above, forced expression of Cdh2 in neonatal mouse CMs led to a marked upregulation of β-Catenin protein level (Fig. 4c) and a significant increase in EdU+ proliferative CM (Fig. 4d) without affecting CM size (Fig. S4a). Ectopic expression of ΔCdh2 in CMs, however, did not result in a discernible change either in β-Catenin protein expression (Fig. 4c) or CM proliferation, compared with control (Fig. 4d). Of note, neither Cdh2 nor ΔCdh2 overexpression affected the transcript expression levels of β-Catenin/Ctnnb1 (Fig. S5a). Taken together, these results suggest that the physical interaction between N-Cadherin and β-Catenin through BBM stabilizes β-Catenin protein, leading to enhanced CM proliferation driven by β-Catenin.

Fig. 4. The pro-mitotic effects mediated by N-Cadherin in CMs depend on its interaction with β-Catenin.

a The protein half-life of β-catenin upon Cdh2/N-Cadherin knockdown in mouse HL-1 CMs was determined using a cycloheximide chase assay, which revealed an accelerated degradation of β-Catenin in Cdh2 KD, compared to Scramble control, CMs (n = 7 in each group at various time points). A two-way ANOVA test (Interaction p = 0.0001; Time points p < 0.0001; and Group p < 0.0001) was utilized followed by a Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. b Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments using neonatal mouse cardiac lysates showed that N-Cadherin could be pulled down with β-Catenin, indicating their physical interaction (left panel). The Co-IP experiments were performed in three independent biological replicates. Schematic illustration of the functional domains of N-Cadherin protein. The β-Catenin binding motif (BBM) locates at the C-terminus of N-Cadherin. Cdh2: wild-type N-Cadherin; ΔCdh2: c-terminus-truncated N-Cadherin. c Immunoblotting revealed that β-Catenin was markedly increased in Cdh2-, but not ΔCdh2-, overexpressed mouse neonatal CMs (n = 5 for Ctrl; n = 5 for Cdh2 OE; and n = 4 for ΔCdh2 OE mouse neonatal CMs). Quantification of N-Cadherin and β-Catenin proteins was shown on the right. A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0306 in relative N-Cadherin expression; and p < 0.0001 in relative β-Catenin expression) was utilized followed by a Fisher’s LSD post-test correction. d Overexpression of WT, but not C-terminus-truncated (ΔCdh2), N-Cadherin led to increased neonatal CMs proliferation, suggesting that BBM is required for the promo-mitotic effects of N-Cadherin in CMs (n = 4 for Ctrl; n = 3 for Cdh2 OE; and n = 4 for ΔCdh2 OE mouse neonatal CMs). A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0059) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

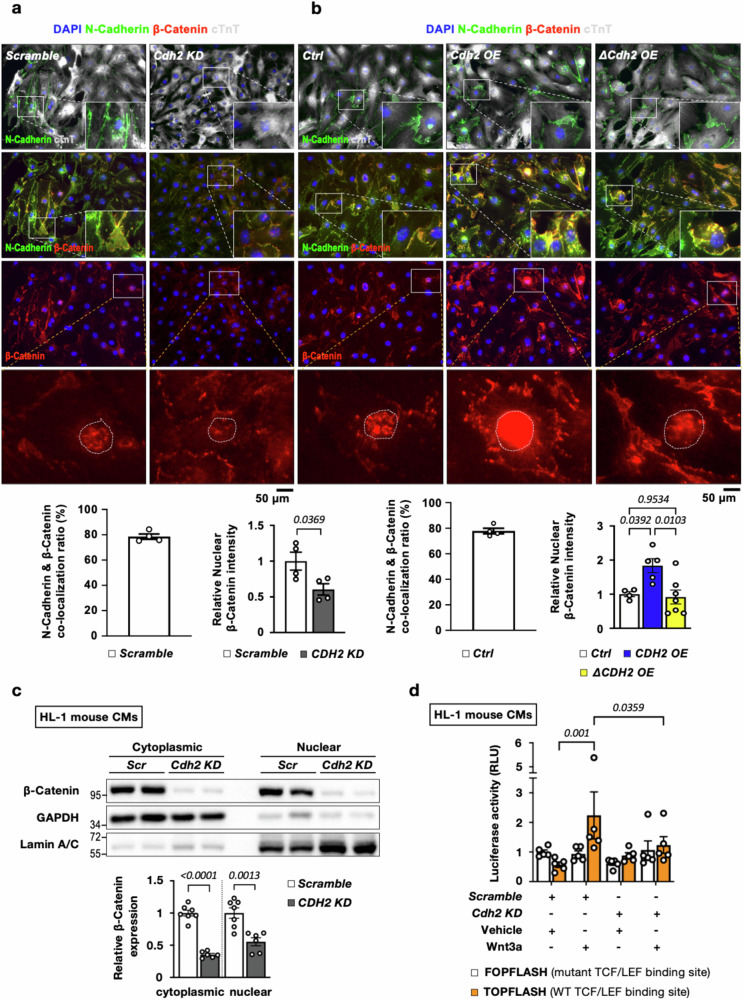

Fig. 5. The nuclear localization and activities of β-Catenin in the CMs are reduced with N-Cadherin depletion.

a IF staining revealed a strong co-localization between N-Cadherin and β-Catenin at the cell membrane in neonatal mouse CM (Scramble control, n = 4). The fluorescence intensity of β-Catenin in CM nuclei was dramatically reduced in Cdh2-depleted neonatal mouse CMs (n = 4 in each group). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. b N-Cadherin and β-Catenin were highly co-localized at the cell membrane of neonatal mouse CM (Control, n = 4). The β-Catenin signal intensity in the nuclei was markedly increased in WT Cdh2-, but not ΔCdh2-, overexpressed neonatal mouse CMs, suggesting that N-Cadherin enhances nuclear retention of β-Catenin through BBM-mediated physical binding (n = 4 for Ctrl; n = 5 for Cdh2 OE; and n = 7 for ΔCdh2 OE mouse neonatal CMs). A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0096) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. c Immunoblots to detect β-Catenin in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of HL-1 mouse CMs with and without Cdh2 KD. GAPDH and Lamin A/C were used as cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively (n = 7 for Scramble; n = 6 for Cdh2 KD HL-1 mouse CMs). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. d Luciferase reporter (TOPFLASH) assays showed that the transcriptional activity triggered by Wnt3a-induced β-Catenin activation was significantly suppressed in Cdh2 KD, compared with Scramble control, HL-1 mouse CMs, revealing the essential role of cardiac N-Cadherin in relation to the nuclear activity of β-Catenin (n = 5 in each group). A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0308) was utilized followed by a Fisher’s LSD post-test correction. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

Next, we went on to determine if N-Cadherin affects the nuclear localization and activity of β-Catenin in the CMs. As shown in Fig. 5a, IF staining revealed a marked reduction of β-Catenin intensity in the nuclei of neonatal CMs with Cdh2 knockdown, compared to those with scramble control. On the other hand, ectopic expression of Cdh2, but not BBM-truncated ΔCdh2 mutant, led to increased β-Catenin nuclear localization in neonatal CMs (Fig. 5b). These data suggest that N-Cadherin promotes the accumulation of β-Catenin in the nuclei of CMs, which is dependent on BBM-mediated N-Cadherin-β-Catenin binding. Immunoblotting further confirmed a marked reduction of β-Catenin protein level both in the cytoplasmic and nuclear fraction, as well as a reduced nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, in HL-1 mouse CMs with Cdh2 knockdown (Fig. 5c). IF staining also revealed that Cdh2 knockdown impaired β-catenin nuclear accumulation induced by Wnt activator CHIR99021 in mouse CMs (Fig. S6). In addition, the activation of TCF/LEF TOPFLASH luciferase reporter by β-Catenin following Wnt3a treatment was completely abrogated with Cdh2 depletion in the HL-1 mouse CMs (Fig. 5d). In contrast, overexpression of WT Cdh2, but not the ΔCdh2 mutant, increased both cytoplasmic, and nuclear levels of β-Catenin protein in mouse CMs (Fig. S7a), which was accompanied by enhanced TCF/LEF TOPFLASH luciferase activity at baseline and after Wnt3a treatment (Fig. S7b). Collectively, these data demonstrate that N-Cadherin/Cdh2 promotes CM proliferation through regulating canonical Wnt signaling. N-Cadherin binds and stabilizes β-Catenin, thereby augmenting the pro-mitotic transcriptional activity driven by β-Catenin.

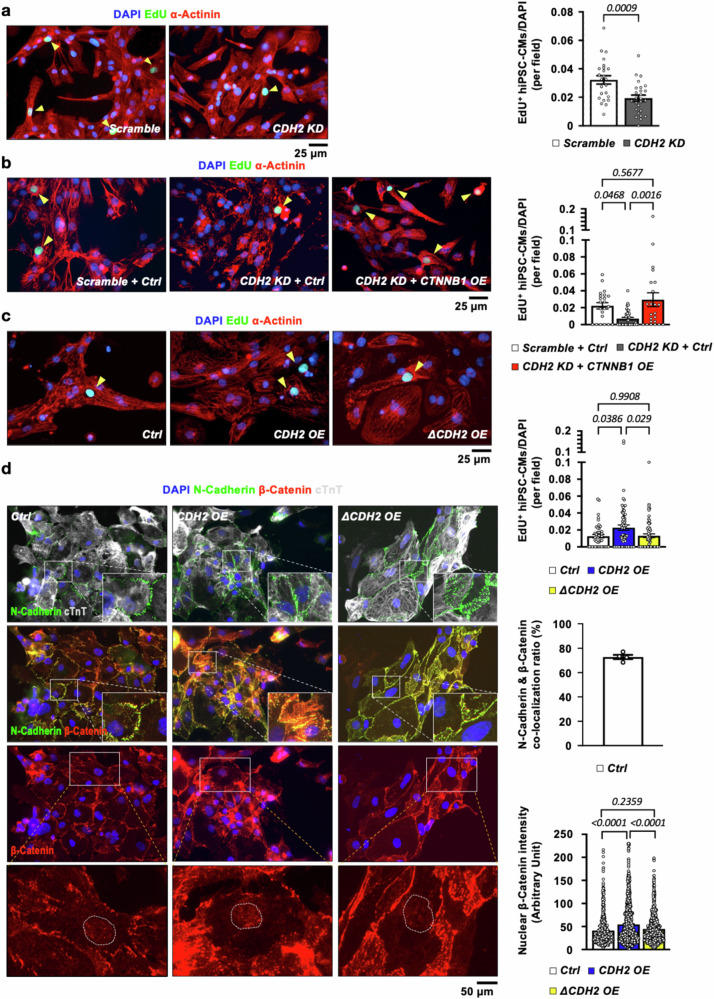

The β-Catenin-dependent pro-mitotic effect of N-Cadherin is conserved in human CMs

To determine if N-Cadherin/CDH2 also regulates the mitotic activity of human CMs, experiments were conducted on human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs). Consistent with the findings in mouse CMs, CDH2 depletion in hiPSC-CMs led to a significant reduction in cell proliferation as evidenced by lower rate of EdU labeling (Fig. 6a) and downregulation of cell cycle gene CCND1 (Fig. S8a). This was accompanied by a significant downregulation of β-Catenin protein, but not mRNA, level in hiPSC-CMs (Fig. S8b). Importantly, replenishing β-Catenin/CTNNB1 restored the proliferative activity in CDH2 KD hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 6b). By contrast, forced expression of CDH2 led to a significantly increased proliferation rate (Fig. 6c), upregulation of CCND1 (Fig. S5b) and increased nuclear localization of β-Catenin in hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 6d) without inducing cellular hypertrophy (Fig. S4b), the effects of which were completely abolished by truncating the BBM domain of N-Cadherin (ΔCDH2, Fig. 6c, d). Similar to the observations made in mouse CMs, N-Cadherin, and β-catenin were highly co-localized at the cell membrane in hiPSC-CMs (Fig. 6d). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the pro-mitotic activity of N-Cadherin driven by β-Catenin-dependent transcriptional activity is mechanistically conserved in both mouse and human CMs.

Fig. 6. The pro-mitotic effect of N-Cadherin/β-Catenin cascade is conserved in human iPSC-derived CMs (hiPSC-CMs).

a Knocking down CDH2 in human iPSC-derived CMs (hiPSC-CMs) led to a significant reduction in their proliferative activity as evidenced by decreased EdU labeling (N = 3 in each group, n = 24 for Scramble; and n = 26 for CDH2 KD hiPSC-CMs). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. b Ectopic expression of CTNNB1 in hiPSC-CMs rescued the suppressed proliferative activity resulting from CDH2 depletion (N = 3 in each group, n = 22 for Scramble + Ctrl; n = 38 for CDH2 KD + Ctrl; and n = 23 for CDH2 KD + CTNNB1 OE hiPSC-CMs). Overexpression of WT CDH2, but not C-terminus-truncated CDH2 (ΔCDH2), increased the proliferative activity (N = 3 in each group, n = 46 for Ctrl; n = 72 for CDH2 OE; and n = 65 for ΔCDH2 OE hiPSC-CMs) (c) and nuclear accumulation of β-Catenin (d) in hiPSC-CMs (N = 3 in each group, n = 487 for Ctrl; n = 998 for CDH2 OE; and n = 751 for ΔCDH2 OE hiPSC-CMs). A one-way ANOVA test (p = 0.0014 in b; p = 0.013 in c; and p < 0.0001 in d) was utilized followed by a Tukey post-test correction. N-Cadherin and β-Catenin were highly co-localized at the cell membrane of hiPSC-CMs (n = 4). All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

N-Cadherin is indispensable for cardiac regeneration in neonatal mouse heart in response to injury

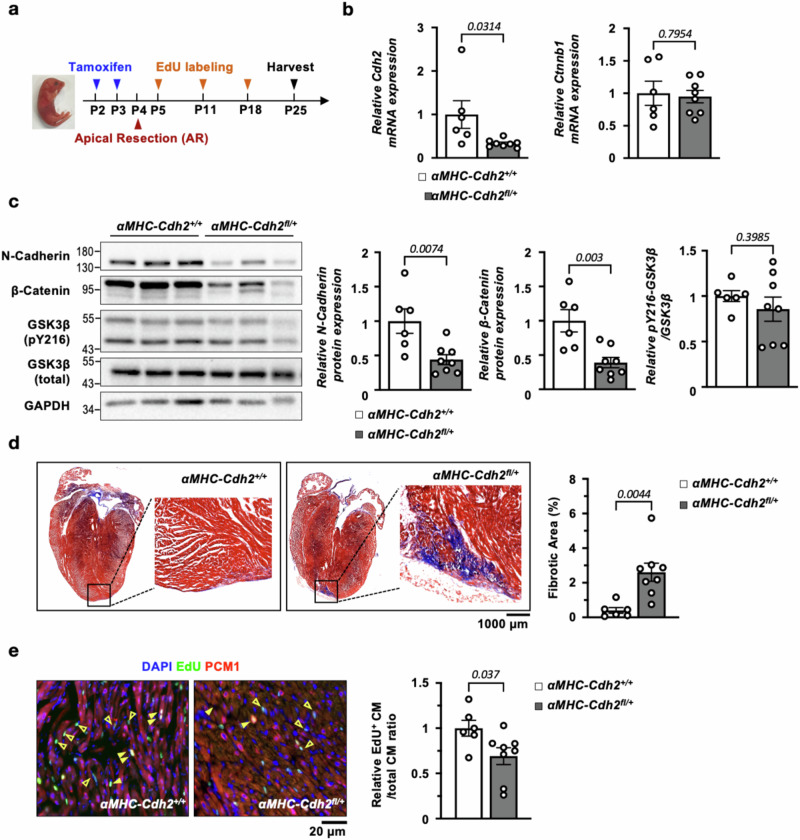

To determine the in vivo contribution of N-Cadherin to cardiac regeneration, an inducible, cardiac-specific heterozygous Cdh2 knockout (αMHC-CreERT2;Cdh2flox/+, abbreviated as αMHC-Cdh2fl/+) mouse line was generated. Global knockout of N-Cadherin is known to cause embryonic lethality due to severe defects in cardiac development33,34; therefore, to avoid the confounding effects of developmental issues, experiments were conducted using heterozygous Cdh2 knockouts induced at the post-natal stage. Indeed, αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ mice, after deleting one allele of Cdh2 gene following two consecutive tamoxifen-treatment at P2-3, developed normally into adulthood. There were no discernible differences in cardiac gross morphology, heart weight/body weight (HW/BW) ratio, CM size (Fig. S9), or electrocardiogram (ECG, Fig. S10), compared to controls (αMHC-CreERT2, denoted as αMHC-Cdh2+/+). After tamoxifen administration, neonatal αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ and αMHC-Cdh2+/+ mice were subjected to AR at P4, followed by assays to quantify histological changes (Masson’s Trichrome staining) and CM renewal (EdU-labeling, experimental scheme shown in Fig. 7a) at P25. As shown in Fig. 7b, c, qPCR and immunoblotting confirmed a ~50% reduction in Cdh2 mRNA and protein levels in αMHC-Cdh2fl/+, compared to αMHC-Cdh2+/+, mouse hearts. Consistent with our in vitro findings, cardiac haploinsufficiency of Cdh2 resulted in a marked reduction in β-Catenin protein (Fig. 7c) without affecting its transcript levels (Fig. 7b). The levels of activated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β, phosophor-Y216), a key component of the β-Catenin destruction complex35, were similar between αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ and control mouse heart, excluding its involvement in N-Cadherin-dependent β-Catenin regulation (Fig. 7c). Interestingly, Cdh2 haploinsufficiency also resulted in reduced levels of pAkt, but not pERK, two signaling molecules implicated in CM survival, proliferation and β-catenin regulation36,37, in the myocardium, suggesting a potential interaction between N-Cadherin and Akt signaling pathway (Fig. S11a).

Fig. 7. N-Cadherin is required for the regeneration of neonatal mouse heart following injury.

a Experimental design to determine the requirement of N-Cadherin for the regeneration of neonatal mouse heart following injury. b Comparing to αMHC-CreERT2 control animals (n = 6), Cdh2 transcript was reduced by ~50% in cardiac-specific Cdh2-haploinsufficient animals (n = 8). The mRNA level of β-Catenin, Ctnnb1, was unchanged in the mouse hearts following Cdh2 depletion. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. c β-Catenin protein levels were markedly downregulated in αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ (n = 8), compared with control (n = 6), LV. There was no discernible change in the levels of total and phosphor-(pY216) GSK3β in αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ compared with control, LV, revealing that the activity of β-Catenin destruction complex is not involved in N-Cadherin-dependent β-Catenin regulation. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. d Masson’s trichrome staining of neonatal αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ (n = 8) and αMHC-Cdh2+/+ (n = 6) mouse cardiac sections 21 days following AR. While control animals achieved complete regeneration, αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ mice failed to regenerate the injured heart, leaving a significantly larger scar in the cardiac apex. Quantification of scar/fibrotic area is shown in the right. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. e The proportion of EdU+ CMs was dramatically reduced in αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ (n = 8), compared to control (n = 6), mouse heart following AR injury. Arrowheads: de novo CMs, hollow arrowheads: proliferating non-CMs. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

Three weeks following AR surgery, control mouse hearts achieved full regeneration without scarring, whereas the αMHC-Cdh2fl/+ hearts failed to regenerate properly as evidenced by a marked increase in fibrosis at the cardiac apex as observed in Masson’s Trichrome staining (Fig. 7d). In addition, the de novo CM (EdU+/PCM1+ cells) generation was significantly reduced in αMHC-Cdh2fl/+, compared to control, neonatal mice (Fig. 7e). In contrast, disrupting the junctional function of N-Cadherin using exherin (50 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally, from Day 1 to Day 5 following apical resection) did not affect the cardiac regenerative capability of neonatal mice (Fig. S12). This suggests that the pro-regenerative action of N-Cadherin is independent of its canonical role as a junctional protein and the external electromechanical cues mediated through adherens junctions. In addition, cardiac Cdh2 haploinsufficiency didn’t affect the biodistribution of N-Cadherin, as N-Cadherin remained predominantly enriched in CMs, rather than in endothelial cells or fibroblasts (Fig. S13a). Together, these results clearly demonstrate the prerequisite role of N-Cadherin in cardiac regeneration, where a 50% loss of cardiac Cdh2 is sufficient to abolish CM renewal, resulting in incomplete cardiac regeneration and excessive scarring in neonatal mouse hearts following injury.

Forced cardiac N-Cadherin expression in vivo promotes myocardial regeneration, improving cardiac function in adult mouse heart after MI

Next, we went on to determine if increasing N-Cadherin levels in the adult mouse heart could promote cardiac regeneration and impact cardiac function. A single intraperitoneal injection of an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) viral vector carrying mouse Cdh2-P2A-CFP driven by a cardiac-specific cTnT promoter (AAV-cTnT-Cdh2-P2A-CFP, abbreviated as cTnT-Cdh2) was administered (5109 viral genome) in wild-type C57BL/6J mice at P8 Fig. 8a. This resulted in a sustained ~1.8- to 2-fold increase in cardiac Cdh2/N-Cadherin mRNA and protein levels into adulthood (Fig. 8b). Mice administered with the cTnT-Cdh2 AAV9 vector developed normally and had similar cardiac/CM sizes (Fig. S14) and ECG morphologies (Fig. S15) with those receiving a control AAV9 vector (AAV-cTnT-CFP, abbreviated as cTnT-CFP). Moreover, ectopic expression of Cdh2 did not disturb biodistribution of N-Cadherin, as N-Cadherin remained highly enriched in CMs (Fig. S13b). In line with the impact of N-Cadherin on cardiac Akt signaling observed in Cdh2-haploinsufficient mouse hearts, viral vector-mediated N-Cadherin overexpression led to a significant increase in pAKT, but not pERK, in the myocardium (Fig. S11b).

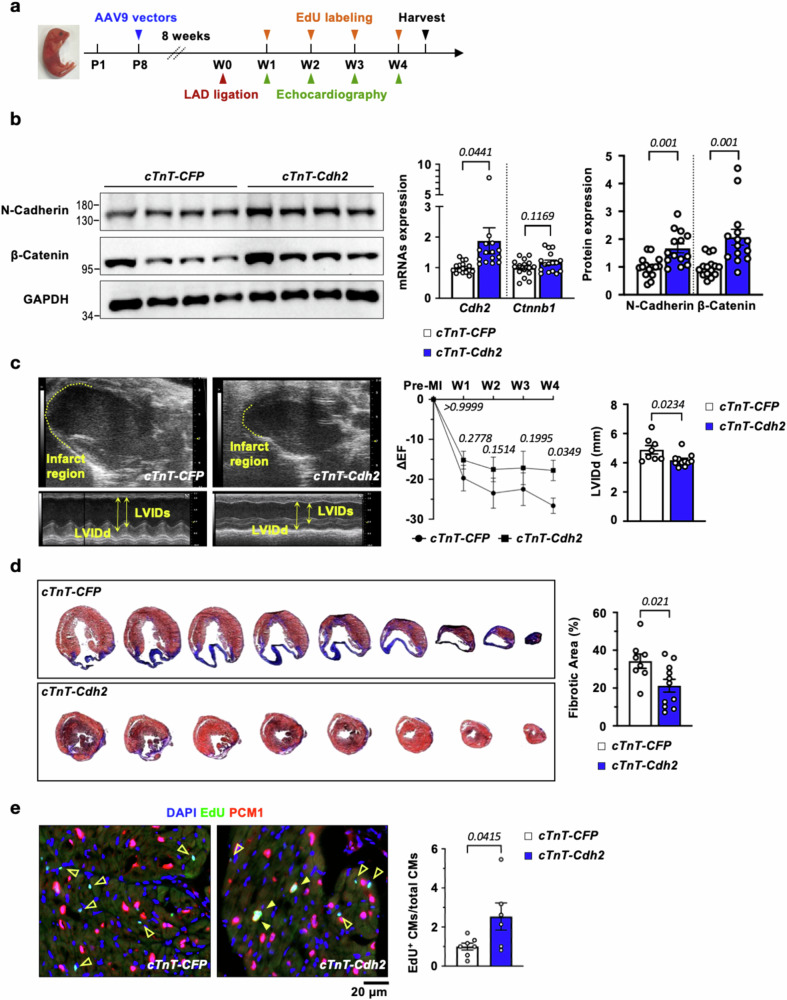

Fig. 8. Replenishing Cdh2/N-Cadherin in the adult mouse heart drives CM self-renewal and ameliorate MI-induced cardiac dysfunction.

a Experimental design to determine if replenishing Cdh2 in the adult heart could promote CM proliferation and mitigate post-MI cardiac dysfunction. b AAV9-mediated cardiac-specific overexpression of Cdh2/N-Cadherin led to a marked upregulation of β-Catenin protein, but not mRNA, in mouse LV (RNA-Cdh2: n = 16 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 15 for cTnT-Cdh2, RNA-Ctnnb1: n = 16 in each group; Protein: n = 15 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 14 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. c Echocardiographic analysis revealed a smaller infract region, reduced left ventricle end-diastolic dimension (LVIDd, n = 8 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 11 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart) and increased ejection fraction (EF, n = 10 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 9 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart) in animals receiving cTnT-Cdh2, compared to control (cTnT-CFP), AAV9 vectors. ΔEF indicates the change of EF following MI injury comparing to pre-MI baseline. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for LVIDd analysis. A two-way ANOVA test (Interaction p = 0.6614; Time points p < 0.0001; and Group p = 0.009) was utilized followed by a Fisher’s LSD test for ΔEF analysis. d Cardiac sections were collected below the ligation level with 400 µm intervals, followed by Masson’s Trichrome staining. Replenishing Cdh2 led to a marked reduction in the scar size following MI (n = 8 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 11 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. (e) The number of proliferative CMs (EdU+/PCM1+) was significantly increased in animals transduced with cTnT-Cdh2, compared to control, AAV9 (n = 7 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 6 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart). Arrowhead: de novo CMs, hollow arrowhead: proliferating non-CMs. A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

cTnT-Cdh2 and cTnT-CFP AAV9 vector-treated animals were subjected to MI induced by ligation of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery at 8–10 weeks, followed by weekly echocardiography and EdU labeling until 4 weeks after MI (experimental scheme illustrated in Fig. 8a). Control cTnT-CFP AAV9-treated animals subjected to MI developed a large infarct area at the LAD territory, enlarged LV chamber size and progressive deterioration of LV contractility (quantified using ejection fraction [EF] on echocardiography) (Fig. 8c). By contrast, cTnT-Cdh2 AAV9-treated animals sustained a smaller akinetic region at the infarct site, less LV chamber dilation, and preserved LV contractile function compared to the control group, 4 weeks following MI (Fig. 8c). Importantly, AAV-mediated cardiac Cdh2 overexpression resulted in a markedly reduced scar size (Fig. 8d) and a significantly higher number of EdU+ proliferative CMs (Fig. 8e), compared to controls. Angiogenesis, quantified by the density of isolectin B4+ ECs in the post-MI mouse heart, however, was not affected by either Cdh2 depletion (Fig. S16a) or overexpression (Fig. S16b).

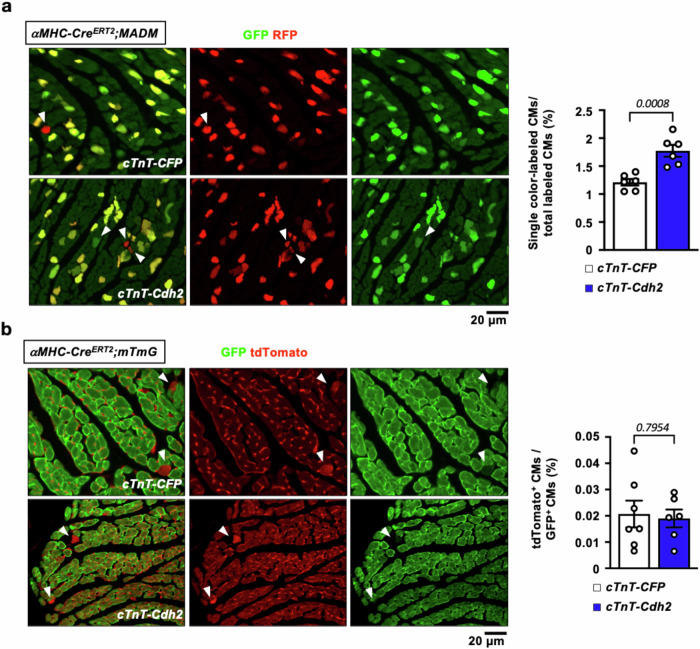

To circumvent the limitation of EdU labeling, especially in the context of CM polyploidy and potential DNA repair upon injury, and to quantify CMs undergoing cell division/cytokinesis directly38, a transgenic mouse line designed to lineage-trace actively dividing CMs, Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (αMHC-CreERT2; MADM)39, was employed (Fig. S17a). In this mouse model, MADM recombination only occurs in CMs upon administration of tamoxifen. CMs undergoing cell division produce daughter cells that are either red, green, yellow (double-colored with red and green), or colorless, depending on the allelic recombination of fluorescent reporters. CMs appear yellow or colorless if they fail to divide or if no recombination occurs. Therefore, single-colored (red or green) cells represent the population of CMs that have definitely undergone cell division, although this may slightly underestimate the count, as double-colored and colorless CMs could have also divided.

As shown in Fig. 9a, a significantly increased number of single-colored (red or green) CMs was observed in Cdh2-overexpressed, compared to control, mouse heart, 4 weeks following MI, indicating that increased cardiac Cdh2 levels drive CM division in adult mouse heart upon ischemic injury. Similar to the cardioprotective effects of Cdh2 overexpression observed in WT mice, ectopic expression of Cdh2 in αMHC-CreERT2;MADM animals led to a significantly improved LV contractility and less chamber dilation than those receiving a control vector (Fig. S17d, e). Additional experiments were performed in αMHC-CreERT2; mTmG reporter mice, in which CMs were labeled with GFP after 4 consecutive doses of tamoxifen administered 2 weeks before MI surgery (Fig. S18). cTnT-Cdh2 and cTnT-CFP AAV9 vector-treated αMHC-CreERT2; mTmG mice exhibited comparable ratio of tdTomato+/GFP+ CMs 4 weeks following MI (Fig. 9b), suggesting a negligible contribution of non-cardiomyocyte to Cdh2-induced CM renewal. Similar to the observation in WT mice, ectopic cardiac Cdh2/N-Cadherin overexpression resulted in a marked upregulation of β-Catenin protein without affecting its transcript level, in αMHC-CreERT2; MADM (Fig. S17b, c) and αMHC-CreERT2; mTmG mouse hearts (Fig. S18b, c). Collectively, these data unequivocally demonstrate that increased cardiac Cdh2/N-Cadherin levels drive CM renewal upon ischemic injury, leading to improved cardiac contractility, limited cardiac chamber remodeling, and scarring in the adult mouse heart.

Fig. 9. Replenishing Cdh2/N-Cadherin in the adult mouse heart drives CM self-renewal and division.

a The αMHC-CreERT2;MADM reporter mouse line was utilized to quantify CMs undergoing self-renewal/division by counting single color-labeled (red or green) CMs. cTnT-Cdh2 AAV9 transduction led to a significantly increased number of newly divided CMs (arrowheads) than those treated with control AAV9 (n = 6 in each group). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. b The αMHC-CreERT2;mTmG reporter mice were utilized to determine the origin of de novo CMs following injury. After tamoxifen induction 2 weeks before MI surgery, CMs were labeled with GFP, whereas non-CMs were labeled in red. Arrowheads indicate CMs derived from non-CM origins, which were labeled with membrane-targeted tdTomato. The ratio of tdTomato+/GFP+ CMs was comparable in cTnT-Cdh2- and cTnT-CFP AAV9-treated groups (n = 7 for cTnT-CFP; and n = 6 for cTnT-Cdh2 adult heart). A two-tailed t-test was utilized for comparison between groups. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. Exact p values are indicated in figures.

Discussion

The adult mammalian heart has a limited capacity for repair and regeneration following injury, leading to the permanent loss of CMs, fibrosis, heart failure, and ultimately, death. Our study has uncovered a non-canonical role of the adhesion junction protein N-Cadherin in the regulation of CM self-renewal, mediated by post-translational binding and stabilization of the pro-mitotic transcription regulator β-Catenin. In this capacity, N-Cadherin serves as a molecular reservoir for β-Catenin, ensuring a readily available supply to be activated in response to regenerative stimuli. Consequently, this activation drives the transcription of cell cycle-related genes, such as Cyclin D1, leading to an increase in de novo CM production. We have shown that cardiac-specific depletion of N-Cadherin compromises the regenerative capacity of neonatal mouse heart, whereas forced expression of N-Cadherin in the adult mouse heart promotes CM proliferation, diminishes scar size, and preserves myocardial function following MI injury (Fig. S19). These findings demonstrate a critical yet previously unrecognized role of N-Cadherin in sustaining CM renewal, which could open avenues for the development of new therapies for HF.

The results from the present study suggest that while β-catenin bound to N-Cadherin is sequestered at the adherence junction complex, this membranous pool of β-catenin is protected from degradation by β-catenin destruction complex. This provides a reservoir of β-catenin that becomes available for nuclear translocation upon Wnt activation. In one recent study by Yan et al.40, for example, overexpression of N-Cadherin in adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells was shown to increase active β-catenin levels through caveolin-mediated membrane-nuclear trafficking. On the other hand, it has been reported that tyrosine phosphorylation at the C-terminus of N-Cadherin may facilitate the release of β-catenin from N-Cadherin41,42. It is possible that caveolin-mediated trafficking or post-translational modification of N-Cadherin by injury-induced signaling (such as Wnt) may trigger the activation and nuclear translocation of this N-Cadherin-bound pool of β-catenin. Indeed, while N-Cadherin/Cdh2 overexpression alone resulted in a moderate but significant increase in TOPFLASH luciferase reporter activity in CMs, the co-administration of Wnt3a could further increase the luciferase reporter activity in CMs with N-Cadherin OE, exceeding the levels induced by Wnt3a treatment or N-Cadherin OE alone (Fig. S7b). These results suggest that Wnt signaling activation is required in conjunction with N-Cadherin to induce a strong nuclear β-catenin activity and drive cardiac proliferation.

Wnt signaling pathways, including multiple Wnt proteins43 and Wnt target genes44, have been shown to be strongly induced in the myocardium following ischemic injury, especially at the infarct border zone44, contributing to the regulation of inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis following MI. Because N-Cadherin-mediated β-Catenin activation is greatly potentiated by Wnt ligand (Fig. S7b), it is likely that a damage trigger such as Wnt signaling activation is necessary to maximize the proliferation-promoting effects of N-Cadherin. This may, at least partially, explain the lack of cardiac hypertrophy phenotype at baseline in mice with N-Cadherin overexpression. While driving a moderate N-Cadherin expression in the adult mouse heart using AAV (~2-fold increase in our study) can enhance the regenerative capacity following cardiac injury, excessive N-Cadherin overexpression may be detrimental. Transgenic mice with high-level cardiac N-Cadherin overexpression, for example, develop dilated cardiomyopathy45, likely due to remodeling of the intercalated disc structure and function.

Neuregulin-1 (NRG1), one of the most studied stimulants of cardiac regeneration46,47, triggers CM proliferation through activating tyrosine kinase receptors ErbB2/ErbB4 on CMs14,48. Activation of NRG1/ErbB2 signaling has been shown to increase β-catenin protein levels in CMs through repression of GSK3β activity48. In addition, NRG1/ErbB2 signaling drives CM de-differentiation, proliferation and hypertrophy through activation of ERK and AKT48. It has been shown that Cdh2 overexpression enhances the survival and engraftment of transplanted hiPSC-CM through activating AKT36. Together with our observation that N-Cadherin regulates β-catenin levels and AKT activities, two known downstream targets of NRG1, these suggest a potential crosstalk between N-Cadherin, Wnt and NRG1-dependent pathways in CMs.

N-Cadherin, as the major transmembrane component of cardiac adherens junction, forms the intercalated disc and is essential to maintain electrical and mechanical coupling between CMs25,49. N-Cadherin also transduces external mechanical cues into intracellular signals in the CMs, driving the cell plasticity and orientation response of CMs to stretch50,51. Interestingly, the pro-mitotic effects of N-Cadherin in CMs seem to be independent of its classical role as a junctional protein. This is evident as inhibition of its junctional function did not affect neonatal mouse heart regeneration following injury (Fig. S12). Additionally, isolated neonatal mouse CMs and hiPSC-CMs can be driven into cell cycle by N-Cadherin even without forming cell-cell contact. Furthermore, this non-canonical, pro-regenerative function of N-Cadherin does not rely on external electromechanical cues, as in vitro experiments unequivocally demonstrate its capability to promote CM renewal without external electrical stimuli or mechanical stretching.

Consistent with the pro-mitotic function of cardiac N-Cadherin observed in postnatal mouse heart, one report by Soh et al. showed that N-Cadherin is required for the establishment and maintenance of anterior heart field (AHF)-cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs), where loss of N-Cadherin resulted in diminished proliferation and premature differentiation of CPCs in the AHF, leading to abnormal cardiac development. Moreover, loss of N-Cadherin in CPCs led to lower β-Catenin expression and activity, whereas introducing stabilized β-Catenin reversed the impact of N-Cadherin deficiency in AHF-CPCs52. These findings collectively suggest that the N-Cadherin/β-Catenin signaling axis serves as a crucial regulator of CM proliferation and maturation during development. The observed rapid decline in cardiac N-Cadherin and β-Catenin expression levels during the postnatal stage could be a key factor in transitioning proliferative/immature CMs into a differentiated/mature state, allowing adaptation to hemodynamic and metabolic stresses experienced after birth. Further investigations are needed to test this hypothesis directly.

Multiple recent studies have demonstrated cardioprotective effects of N-Cadherin against ischemic heart injury. In a study by Yan et al., adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells engineered to express higher levels of N-Cadherin showed an enhanced capacity to stimulate CM proliferation and angiogenesis, which contributed to improved cardiac function after ischemic injury40. Furthermore, overexpression of N-Cadherin in hiPSC-CMs increased their survival, engraftment, and functional integration into the post-MI mouse myocardium, thereby augmenting the reparative properties of implanted hiPSC-CMs in the ischemic failing heart36. Here, we provide direct experimental evidence supporting a cell-autonomous role of N-Cadherin in driving CM self-renewal through amplifying β-Catenin-dependent pro-mitotic activities. These cardioprotective effects of N-Cadherin observed both in CMs and stromal cells suggest that enhancing N-Cadherin expression in cardiac tissue could be a powerful new approach to promote post-injury myocardial repair and regeneration.

One potential concern of promoting cardiac regeneration through augmenting N-Cadherin/β-Catenin cascade is their oncogenic potential. N-Cadherin is aberrantly expressed in various cancer types and is known to promote tumor growth, invasion and metastasis53. In our experiments, long-term (3 months) ectopic N-Cadherin expression with AAV9 did not cause cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. S9) or tumor formation in cardiac and non-cardiac tissues. These data indicate that AAV9-mediated N-Cadherin expression driven by a cardiac-specific cTNT promoter is not oncogenic up to 3 months. It remains to be determined, however, if prolonged overexpression of cardiac N-Cadherin is associated with tumor growth, especially in large mammalian animal models.

In conclusion, the present study unveiled the non-canonical function of adherens junction protein N-Cadherin in maintaining the proliferative potential of CMs through post-translational stabilization and upregulation of pro-mitotic β-Catenin. We showed that cardiac-specific deficiency of N-Cadherin impedes cardiac regeneration in neonatal mice, whereas forced expression of N-Cadherin in post-MI adult mouse heart improves cardiac function by promoting de novo CM production. These discoveries highlight a prerequisite and previously unknown function of N-Cadherin in supporting the renewal of cardiac muscle, offering new possibilities for developing novel treatments for HF.

Methods

Isolation of neonatal and adult mice CM

CMs were isolated from postnatal day 1 (P1) WT neonatal C57BL/6 mice. Neonatal mouse cardiac ventricles were first minced and dissociated into single-cell suspension using Neonatal Mouse and Rat Heart Dissociation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec) with a gentleMACS™ dissociator. CMs were then further enriched from cardiac cell suspension using the Neonatal Mouse CM Isolation Kit and autoMACS® Columns (Miltenyi Biotec). Neonatal mouse CMs were cultured on fibronectin-coated cell culture dishes and fed with DMEM/M199 (5:1, Sigma-Aldrich) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco). When performing viral particle transduction, a smaller volume of culture medium containing 1% FBS was used to maximize the transduction efficiency.

For adult CM isolation, 8–12-week-old male WT C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized and the heart was harvested, washed in PBS, cannulated at the aortic root and retrogradely perfused with collagenase II-containing digestion buffer at 37 °C for 8 min. After removal of atrial tissues, ventricles were minced, washed and re-suspended in M199. Adult ventricular CMs were plated on laminin (1 μg/ml)-coated dish and maintained in M199 with 10% FBS54.

RNA sequencing library preparation

Total cellular RNA was isolated from adult CM (n = 7), neonatal day 1 (P1, n = 4), and day 3 (P3, n = 4) CM. RNA libraries were prepared using TrueSeq RNA Sample Prep Kits (Illumina) by the manufacturer’s recommendations. In brief, RNA from postnatal day 1, 3 as well as adult mice was twice oligo (dT) selected using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. The poly-A (+) RNA was then eluted, fragmented and reverse transcribed into first strand cDNA using random hexamers, followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis. Double-stranded cDNAs were end-repaired and adenylated (singly) at the 3’ ends. Barcoded adapters containing unique six-base index sequences and T-overhangs were ligated to the cDNA samples prepared from each of the individual mouse LV samples. Individual cDNA libraries were PCR amplified and purified; five to six barcoded libraries were pooled in equimolar (10 nmol/L) amounts and diluted to 4 pmol/L for cluster formation of a single flow cell lane, followed by pair-end sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer.

RNA sequencing data processing

After demultiplexing the sequencing data, adapter sequences were removed and the individual libraries were converted to the FASTQ format. Sequence reads were mapped to the mouse genome (mm10) with Hisat2, allowing up to two mismatches. Sequence reads aligned to the mouse genome were imported into Partek Genomics Suite version 6.6 (Partek, St Louis, MO) for sequence read clustering, counting, and annotation. The RefSeq transcript database was chosen as the annotation reference and subsequent data analyses were focused on sequence reads mapping to coding exons. The read counts of each known transcript were normalized to the length of the individual transcript and to the total mapped read counts in each sample and expressed as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads). Sequence reads mapped to different isoforms of individual genes were pooled together for subsequent comparative analysis55.

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA)

A weighted co-expression gene network encompassing all confidently detected mRNAs (FPKM ≥ 0.1 in all 15 samples, n = 9667) was constructed using WGCNA R package56. Briefly, for each pair of genes, their expression correlation across the 15 mouse CM RNA samples was calculated. Soft thresholding at β = 6, following the scale-free topology criterion, was applied to the Pearson correlation matrix to ascertain the strength of connections between genes. The connectivity (k) for each gene was calculated by summing these connection strengths with all other genes. Genes exhibiting similar connection strength patterns (topological overlap) within the network were categorized into distinct “modules”. Each module is characterized by genes sharing similar expression profiles across samples, and these profiles are uniquely different from those in other modules, indicating high correlation within the same module. GO and bubble plot analyses of genes of individual modules were performed using WEB-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit (WebGestalt, http://webgestalt.org)57.

HL-1 cardiomyocyte culture

HL-1 cardiac muscle cells were cultured in fibronectin/gelatin pre-coated plate and maintained with Claycomb Medium (Sigma-Aldrich, 51800 C) containing 100 µM norepinephrine, 10% FBS (Gibco), 100 μg/mL Penicillin/Streptomycin and 2 mM L-glutamine54.

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells-derived CM

Human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) derived from the peripheral blood mononuclear cells of a healthy female subject was obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research Center in Taiwan. The hiPSCs were maintained on hESC-qualified Matrigel (Corning) in Essential 8 flex medium (Gibco). The cells were passaged every 3 days at 80% confluence with 0.5 mM EDTA in DPBS without CaCl2 and MgCl2 (Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Human iPSCs were differentiated into CM (hiPSC-CM) using a small molecule-based differentiation protocol described previously58. The hiPSCs were treated with 7uM CHIR99021 (Cayman) in RPMI/B27-insulin (Gibco) for 48 h (D0 to D2). Then the cells were treated with 5uM IWP4 (Cayman) in RPM/B27-insulin for another 48 h. The cells were cultured in RPMI/B27-insulin, with media changes every other day until the CM start beating. In the CM purification step, hiPSC-CMs were cultured in glucose-free RPMI (Gibco) supplement with 4 mM lactic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) and L-ascorbic acid 2- phosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) until non-CM cells were removed. CMs were then dissociated with Accutase (Innovative Cell Technology) and maintained in RPMI/B27.

For CDH2 knockdown experiments in hiPSC-CM, post-differentiation D20 hiPSC-CMs were used. Lentiviral transduction was conducted on day 1 and cells were harvested on day 3. EdU labeling was performed from day 2 to day 3. For CDH2 overexpression experiments, post-differentiation D30 hiPSC-CMs were used. AAV transduction was performed on day 1 with medium change on day 2 and day 5. Cells were harvested on day 7.

Lentiviral transduction for gene knockdown in vitro

Lentiviral particles containing shRNAs pLKO.1 shCdh2 (TRCN0000094855) were used to knockdown Cdh2 in P1 neonatal mouse CM and HL-1 cells. Lentiviral particles containing pLKO.1 shScr (TRCN00001) were used as a non-targeting control. P1 neonatal CM and HL-1 cells were transduced using a lentiviral vector at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20 and 10, respectively. After transduction, HL-1 cells were selected using puromycin (3 μg/mL).

AAV transduction for gene overexpression in vitro

An adeno-associated viral vector (AAV) expressing mCdh2 was used to overexpress Cdh2 in neonatal mouse CM. P1 neonatal CMs were transduced with 4.5109 viral genome AAV in 1% M199 medium 24 h after plating. Culture medium was changed 18–24 h after transduction. Cells were harvested and/or analyzed on day 6.

Pharmacological inhibitors

To assess the role of β-Catenin in N-Cadherin-mediated effects in CM, P1 neonatal CM was treated with 10 μM β-Catenin inhibitor KYA1797K (TargetMol) two days following Cdh2 overexpression with AAV, where distilled water was used as vehicle control. Exherin (50 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally, from Day 1 to Day 5 following apical resection) was utilized to disrupt the junctional function of N-Cadherin.

Apical resection (AR)

AR was performed in postnatal day 1 or day 4 mice. Neonatal mice were anaesthetized through hypothermia by placing them on ice for 4 min. Lateral thoracotomy was performed on mice and the heart was exposed by applying external pressure to the abdomen. About 10% of the apex was excised using iridectomy scissors. The thoracic wall and the skin were then closed with 7-0 nylon sutures. Sham-operated mice (thoracotomy only) were used as controls. Following surgery, mice were recovered under a heat lamp and nursed by a dam after recovery10.

Myocardial infarction (MI)

To induce MI, left anterior descending artery (LAD) ligation was performed on 8–12-week-old WT C57BL/6, αMHC-CreERT2; MADM and αMHC-CreERT2; mTmG mice. Mice were anesthetized with Tribromoethanol (Avertin, 0.25 mg/kg, intraperitoneally, i.p., Sigma-Aldrich), intubated with a 22G endotracheal tube and connected to a small animal ventilator. A thoracotomy between the 4th and 5th rib was performed to expose the heart. LAD was ligated at 2 mm below left atrium with a 7-0 nylon suture. The thoracic incision was closed with a 6-0 nylon suture. Mice were placed under a heat lamp until they recovered. Echocardiography was performed at baseline and 1, 2, 3, 4 weeks following surgery.

Echocardiography

Echocardiography was performed using a Vevo 2100 Imaging System (VisualSonic Inc., Toronto, Canada) to assess the cardiac function of experimental animals. Mice were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane and placed in a supine position. Parameters including interventricular septal thickness (IVS), left ventricular internal dimension and left ventricular posterior wall thickness were measured at end-systolic and end-diastolic phases, where left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, %) was calculated.

Electrocardiogram

Electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded from the experimental animals using the Biopac Student Lab System. Mice were anesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane; needle electrodes were subcutaneously inserted at 4 limbs. ECG were recorded for a total of 20 min and the ECG recordings from 5 to 15 min were analyzed.

EdU labeling and co-staining with cellular markers

P1 neonatal CMs were treated with 10 μM 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (EdU, Abcam) in culture medium for 48 h before fixation. For neonatal mice, animals were intraperitoneally injected with EdU (50 mg/kg) on day 1, 7, 14 post-ARs59,60. Mouse hearts were harvested on day 21 following AR surgery. For adult mice, EdU was administered intraperitoneally on day 1, 8, 15, 22 post-myocardial infarction surgery with 10 mg/kg EdU61. Adult mouse hearts were harvested on week 4 after MI surgery. OCT-embedded cardiac sections were used for following staining.

An EdU Staining Proliferation Kit (iFluor 488 by Abcam, #ab219801) was used to stain EdU-labeled sample following the manufacturer’s instructions. In short, EdU-treated cells or cardiac sections were permeated with 1x permeabilization buffer at room temperature for 20 min. After washing, samples were incubated in a freshly prepared reaction cocktail, containing CuSO4, EdU additive solution, and iFlour 488 azide for 30 min at room temperature.

P1 neonatal CMs cultured on 8-well chamber slide (ibidi, #80841-90) were washed with ice-cold PBS, fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min, permeabilized with 1x permeabilization buffer at room temperature for 20 min and followed by EdU staining as described above. The slides were blocked in 2% BSA and then incubated with primary antibodies, including sarcomeric α-actinin (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, #A7811), phospho-Histone H3 (pH3) (1:5000, Abcam, #ab177218), N-Cadherin (1:2000, Servicebio, #GB12135), β-Catenin (1:50, Cell Signaling, #8480), and cardiac troponin T (1:1000, Proteintech, #15513-1-AP) conjugated with FlexAble 2.0 CoraLite® Plus 647 antibody labeling kit (Proteintech, #KFA503) in 2% BSA at 4 °C overnight. After additional washing with PBS, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 555 or 594 anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:500, Biolegend, #405324 and #406418) in 2% BSA for 60 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were stained with DAPI (2 μg/mL) and mounted with a coverslip (Vector Laboratories Inc).

For tissue staining, paraffin- or OCT-embedded cardiac sections were used. After deparaffinization or removal of OCT, tissue sections were incubated with 2% BSA and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 1 h, incubated with PCM1 (1:250, Sigma-Aldrich #HPA023374) as CM marker, sarcomeric α-actinin (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich), N-Cadherin (1:2000, Genetex, #GTX127345), isolectin B4 (1:1000, Vector Laboratories, #DL-1207) and Vimentin (1:1000, Abcam, #ab8978) and then secondary antibody in a humidified chamber using described protocols26,62,63.

Images were detected utilizing a fluorescence microscope, EVOS M7000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), or Nikon ECLIPSE Ni-L (Nikon). CMs undergoing proliferation (EdU- or pH3- and sarcomeric-α-actinin double-positive or EdU-PCM1 double-positive cells) and β-Catenin fluorescent intensity were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Histology

Cardiac tissues were fixed with 10% formalin or 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 1-day, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Masson’s trichrome staining (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to determine the fibrotic areas in the cardiac sections.

Analysis of RNA expression in different cardiac regions

After AR in P1 mice, mouse hearts were harvested 7 days later, snap-frozen, and embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound. Cryosectioning was performed (300 μm-thick from apex to base) to collect different regions of the cardiac tissues. Following removal of OCT, RNA was extracted from the cardiac sections using Trizol (Invitrogen Life Technologies) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

AAV9 viral vector production and transduction

AAV9 viral vectors containing cTnT-mCdh2-P2A-CFP and cTnT-CFP (control) were produced by NTU CBT-LS-AAV Core, where AAV Helper Free Packaging System (Cell Biolabs, Inc.) was used for AAV9 production. In brief, cTnT promoter-driven mouse Cdh2-P2A-CFP and control (cTnT-CFP) was cloned into B1268 pAAV MCS Expression Vector (Cell Biolabs, Inc. VPK 410). A total of 10 μg pAAV Cdh2 Expression vector, pAAV, and pHelper constructs were co-transfected into HEK 293T cells using jetPRIME (Polyplus). The cells were harvested 72 h later, followed by AAV viral particle extraction using AAVpro® Extraction Solution A and B (Takara) and purification using PEG Virus Precipitation Kit (Biovision). Finally, PEG was removed by adding KCl to 1 M and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min. The viral particles were enriched in the supernatant and stored at −80 °C. AAV viral titer was determined using AAVpro® Titration Kit with real-time PCR. Control and mCdh2-expressing AAV9 particles (5109 viral genome) were injected intraperitoneally in P8-12 mice by insulin syringe with a 30-gauge needle. The extent of cardiac overexpression of mCdh2 was determined at 8–12 weeks of age.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear lysate extraction

Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein lysates were extracted from Cdh2 knockdown and control HL-1 cells by using NE-PER™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Cycloheximide pulse-chase assay

To determine the impact of Cdh2 depletion on the stability of β-Catenin protein, Cdh2-knockdown and control HL-1 cells were treated with 50 μg/mL cycloheximide to block protein translation. The cell lysates of Cdh2-knockdown and control HL-1 cells were collected at 0, 2, 4, 8 h after cycloheximide treatment, followed by quantification of β-Catenin protein levels with immunoblotting. The remaining β-Catenin level at each time point was expressed relative to that at time 0. In these experiments, GAPDH was used as control.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cardiac tissue and cells using TRIzol agent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) using described methods26,55. Reverse transcription was performed with Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) followed by SYBR-Green qRT-PCR. The list of primer sequences used in the study is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Total protein was extracted from mouse cardiac tissues, neonatal CM, or HL-1 cells using 1X Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (MCE). Protein concentration was determined using a Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Protein samples were mixed with T-Pro laemmli reagent (T-Pro Biotechnology) and denatured by heating. Equal amount of protein for each sample was loaded in the 8-10% SDS-PAGE gel. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, blocked in 5% BSA with 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature, incubated with primary antibodies including N-Cadherin (1:1000, Genetex), Cyclin D1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2978), β-Catenin (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), p-GSK3β (Ser9) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #5558S), GSK-3β (1:500, Santa Cruz, #sc-377213), p-Yap (Ser127) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4911), Yap (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4912), p-AKT (Ser473) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4060S), AKT (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9272S), p-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2 Thr202/Tyr204) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9101S), p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, #9102), Lamin A/C (1:1000, Santa Cruz, #sc-376248), Lamin A/C (1:1000, Servicebio, #GB11407), and GAPDH mAb-HRP (1:30000, MBL, #M171-7) at 4 °C overnight. After washing, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit whole IgG secondary antibodies (1:5000, Pierce) for 1 h. Protein signals were detected by adding Western Bright ECL HRP (Advansta) or TOOLS Ultra ECL-HRP (TOOLS, #TU-ECL02) substrate and imaged/quantified using ChemiDoc MP system and ImageLab software v.5.1 (BioRad Laboratories).

Statistics and reproducibility

Prism 9 (GraphPad) software was utilized for statistical analyses. All experimental data are presented as means ± SEM. A two-tailed t-test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between experimental groups. One-way ANOVA in conjunction with post hoc Tukey’s or Fisher’s LSD test was utilized for multiple group comparison. Two-way ANOVA in conjunction with post hoc Bonferroni’s or Fisher’s LSD test was utilized for multiple group and time comparison. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Study approval

All studies were carried out following the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC, No. 20180099) of National Taiwan University, College of Medicine. Both genders of neonatal- and adult male-hearts were included in this study. However, it remains uncertain whether the results are applicable to female mice. All experimental animals were assigned unique identifiers to blind experimenters to genotypes and treatment. A block randomization method was used to assign experimental animals to groups on a rolling basis to achieve an adequate sample number for each experimental condition.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of the Animal Core, Biomedical Resource Core, and the imaging core at the First Core Labs, National Taiwan University College of Medicine, for technical assistance. We also thank the technical services provided by the 2nd, 3rd, 7th, and 8th Core Labs of the Department of Medical Research at National Taiwan University Hospital. This work was funded by Taiwan National Science and Technology Council Grants 111-2628-B-002-008, 111-2314-B-002-069 MY3, 112-2314-B-002-277 MY3, 112-2918-I-002-002 and 112-2926-I-002-511-G (K.C.Y.), an Innovative Research Grant from Taiwan National Health Research Institute NHRI-EX112-11213BI (K.C.Y.), a CRC Translational Research Grant IBMS-CRC111-P01 (K.C.Y. and S.L.L.) and a Grand Challenge Program Grant AS-GC-110-L06 (K.C.Y. & S.L.L.) from Academia Sinica, Taiwan, grants from National Taiwan University Hospital NTUH. VN111-08, VN112-06, VN-113-03, 111-S0042, 112-S0307, 112-S0311, 113-S0196, 111-IF0005, 113-IF0002, 113-E0008 (K.C.Y.), Collaborative Research Projects of National Taiwan University College of Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital and Min-Sheng General Hospital 109F005-110-B3, 109F005-111-C2, 119F005-112-M2 (K.C.Y.), grants from the Excellent Translation Medicine Research Projects of National Taiwan University College of Medicine and National Taiwan University Hospital, NSCCMOH-131-41, 111C101-051, 112C101-031 (K.C.Y.) and Career Development Grants from National Taiwan University 112L7849, 113L7832 (K.C.Y.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Y.W.T., Y.S.T., Y.S.W., and K.C.Y.; experimental design: Y.W.T., Y.S.T., Y.S.W., S.L.L., W.C.L., and K.C.Y.; data collection and analyses: Y.W.T., Y.S.T., Y.S.W., W.L.S., M.Y.Y., Y.C.H., W.H.H., J.C.C., C.L.L., K.H.W.; reagent and technical support: W.P.C.; manuscript writing, review, and editing: all authors.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All deep sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus repository (GEO ID: GSE253966). The raw data and uncropped scans of blots of all Figures and Supplementary Figures. are provided in the Source Data file with this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yi-Wei Tsai, Yi-Shuan Tseng.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-56216-y.

References

- 1.Chen, J., Normand, S. L., Wang, Y. & Krumholz, H. M. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA306, 1669–1678 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jhund, P. S. et al. Long-term trends in first hospitalization for heart failure and subsequent survival between 1986 and 2003: a population study of 5.1 million people. Circulation119, 515–523 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy, D. et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med.347, 1397–1402 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMurray, J. J., Petrie, M. C., Murdoch, D. R. & Davie, A. P. Clinical epidemiology of heart failure: public and private health burden. Eur. Heart J.19, P9–P16 (1998). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Askoxylakis, V. et al. Long-term survival of cancer patients compared to heart failure and stroke: a systematic review. BMC Cancer10, 105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crater, S. W. et al. Real-time application of continuous 12-lead ST-segment monitoring: 3 case studies. Crit. Care Nurse20, 93–99 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamba, L., Harrison, M. & Lien, C. L. Cardiac regeneration in model organisms. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc Med.16, 288 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witman, N., Murtuza, B., Davis, B., Arner, A. & Morrison, J. I. Recapitulation of developmental cardiogenesis governs the morphological and functional regeneration of adult newt hearts following injury. Dev. Biol.354, 67–76 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poss, K. D., Wilson, L. G. & Keating, M. T. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science298, 2188–2190 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porrello, E. R. et al. Transient regenerative potential of the neonatal mouse heart. Science331, 1078–1080 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haubner, B. J. et al. Complete cardiac regeneration in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Aging4, 966–977 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strungs, E. G. et al. Cryoinjury models of the adult and neonatal mouse heart for studies of scarring and regeneration. Methods Mol. Biol.1037, 343–353 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haubner, B. J. et al. Functional recovery of a human neonatal heart after severe myocardial infarction. Circ. Res118, 216–221 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bersell, K., Arab, S., Haring, B. & Kuhn, B. Neuregulin1/ErbB4 signaling induces cardiomyocyte proliferation and repair of heart injury. Cell138, 257–270 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foglia, M. J. & Poss, K. D. Building and re-building the heart by cardiomyocyte proliferation. Development143, 729–740 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heallen, T. et al. Hippo pathway inhibits Wnt signaling to restrain cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart size. Science332, 458–461 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]