Abstract

Particle size and surface properties are crucial for lymphatic drainage (LN), dendritic cell (DC) uptake, DC maturation, and antigen cross-presentation induced by nanovaccine injection, which lead to an effective cell-mediated immune response. However, the manner in which the particle size and surface properties of vaccine carriers such as mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) affect this immune response is unknown. We prepared 50, 100, and 200 nm of MSNs that adsorbed ovalbumin antigen (OVA) while modifying β-glucan to enhance immunogenicity. The results revealed that these MSNs with different particle sizes were just as efficient in vitro, and MSNs with β-glucan modification demonstrated higher efficacy. However, the in vivo results indicated that MSNs with smaller particle sizes have stronger lymphatic targeting efficiency and a greater ability to promote the maturation of DCs. The results also indicate that β-glucan-modified MSN, with a particle size of ∼100 nm, has a great potential as a vaccine delivery vehicle and immune adjuvant and offers a novel approach for the delivery of multiple therapeutic agents that target other lymph-mediated diseases.

Keywords: Smart nanoparticles, Immunomodulatory nano-vaccine, Lymph node targeting, Mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Dendritic cells mature

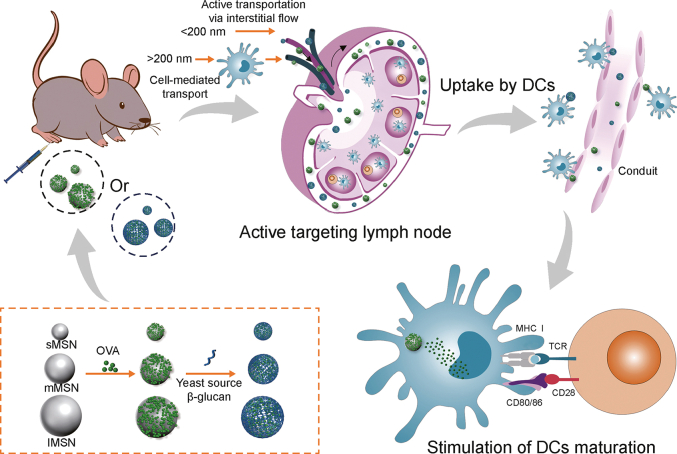

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

We explored the lymph node targeting ability of MSNs with different particle sizes.

-

•

The modification of β-glucan on MSNs improved lymphatic targeting of antigens and demonstrated a better cellular safety.

-

•

∼100 nm-sized β-glucan-modified MSNs hold promise as novel nanovaccine delivery vehicles.

1. Introduction

Because of their better therapeutic efficacy, vaccines based on nanomaterials—also known as nanovaccines—have become a viable new therapeutic option for immunotherapy in recent years [1,2]. Nanovaccines are typically prepared by co-loading antigens and immune adjuvants into nanocarriers [3]. Nanovaccines exhibit several unique benefits over conventional vaccines, chief among them being: (i) enhanced antigen stability through encapsulation shielding of the carrier material; (ii) promotion of homing accumulation of lymph nodes (LNs) and retention of antigen/adjuvant through nano-size effect and specific targeting modifications; (iii) promotion of antigen presentation through enhanced antigen uptake efficiency of antigen-presenting cell (APC); and (iv) enhancement of antigen presentation by providing immune-adjuvant effects to enhance immunogenicity [[4], [5], [6]]. It is evident that by enhancing antigen presentation and immunogenicity, biomedical nanotechnology can significantly improve vaccine delivery efficiency and successfully elicit immune responses.

As mentioned above, lymph nodes (LNs) play an important role in vaccine efficacy by eliciting an immune response in the body [7]. Since LNs are the intended recipient of both adjuvant and antigen [8], they are made up of lobular structures within which B cells and T cells are found in distinct follicles in the cortex and deep paracortical areas, respectively. These cells can interact with resident dendritic cells (DCs) within the LNs as well as migrate DCs that are brought in from the periphery via afferent lymphatic vessels [9]. When it comes to the delivery of nanovaccines to LNs, the lymphatic capillaries serve as the entry point for the selection of exogenous cargo [10]. The intercellular space of lymphatic endothelial cells ranges from 20 to 100 nm, meaning that particle size plays a major role in the entry of nanovaccines into LNs [11]. When administering nanovaccines, there are two primary pathways of entrance into LNs [12]. It was shown that tiny nanocarriers can effectively penetrate draining LNs and aggregate there through peripheral lymphatic arteries. Larger nanocarriers, on the other hand, were mostly held at the injection site before being taken up by peripheral APCs and moving into LNs [13]. The nanovaccines can drain to LNs following subcutaneous injection and be absorbed by APCs, mostly DCs. The adjuvants and antigens were then released into the cytoplasm by the nanovaccines when they broke free from the lysosome. After that, APCs process and present the antigens. Ultimately, immunological responses are triggered by the activation of T and B cells [14].

Nanovaccines that elicit an immune response need to provide sufficient immunogenicity to initiate an adaptive immune response, in addition to being able to target delivery of the antigen to the LNs. It may be possible to overcome this situation by defining a combination of adjuvants [15]. Adjuvant usage can get over this impediment, but it can also cause other issues. For the creation of vaccines, efficient antigen-delivery vehicles that can serve as intrinsic adjuvants as well as antigen carriers are widely desired [16]. mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) as the carrier is characterized by adjustable size, multifunctionality, high stability, and biocompatibility [17]. For macromolecules, MSN can achieve efficient delivery by methods such as adsorption and covalent bonding [18,19]. Therefore, we chose MSN as the core structure of the nanovaccine delivery system to adsorb the model antigen ovalbumin antigen (OVA) while grafting β-glucan to enhance the immunogenicity of MSN. Here, while most polysaccharides have immunomodulatory effects, β-glucan can act on DC-associated C-type lectin receptor (Dectin1)-mediated immune effects while Dectin-1 is required for immune responses to certain fungal infections [20]. In addition, β-glucan can induce functional reprogramming of monocytes, leading to enhanced cytokine production in vivo and in vitro [21]. Instead, α-glucan is able to play a role in pathogenesis by preventing β-glucan from being recognized by host phagocytes [22]. Therefore, we chose β-glucan as an immunoadjuvant.

To better validate this delivery strategy, we specifically designed MSN of small particle size MSN (sMSN), medium particle size MSN (mMSN), and large particle size MSN (lMSN) that simultaneously modified β-glucan on the surface of MSNs (Fig. 1). We hope that surface-modified β-glucan MSNs play a stronger adjuvant role, promote the efficiency of antigen cross-presentation, and significantly facilitate DC maturation. In addition, we aim to validate MSNs with different particle sizes for lymphatic vessel targeting efficiency and ability to recruit and activate DCs within LNs.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing how antigen-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) are targeted at lymph nodes to trigger an adaptive immune response: active target to lymph nodes, uptake by dendritic cells (DCs), maturating DCs, and presenting peptide-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I complex to CD8+ T cells, toll-like receptor (TCR). sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN; OVA: ovalbumin antigen.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Tetraethoxysilane (TEOS, 98%), N-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, 98%), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, 98%), (3-aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES), and OVA were obtained from Aladdin Chemical Inc. (Shanghai, China). Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) was purchased from Tianjin Yongda Chemical Reagent Co. (Tianjin, China). Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) was obtained from Meilun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). Recombinant mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (rmGM-CSF) and allophycocyanin conjugated anti-mouse SIINFEKL/H-2Kb antibody were purchased from Annoron Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). β-Glucan was purchased from Xiamen Helisen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Xiamen, China). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was purchased from APExBIO Technology (Houston, TX, USA). Other antibodies were purchased from Thermo eBioscience Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and Shan Dong Yu Wang Reagent Co. was the supplier of the remaining reagents. (Yucheng, China).

2.2. Animals

The study utilized male C57BL/6 mice (age, 6–8 weeks) were obtained from Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Benxi, China). The mice were housed in a controlled environment that was free from pathogens, with regulated lighting and temperature conditions. All animal experiments were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Use Committee of China Medical University and the National Research Council's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Approval numbers: CMU2021187).

2.3. Cell culture

DC2.4 cells (acquired from Shanghai Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were isolated and cultivated, following the methodology outlined in previous studies [23]. In a concise way, the cells were collected from the bone marrow of the tibia and femur of mice and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 20 ng/mL of rmGM-CSF for 6 days to form immature BMDCs. The culture status of BMDCs is shown in Fig. S1.

2.4. Preparation of MSN of different particle sizes

MSNs with different particle sizes were prepared by one-pot synthesis [24] using the cationic surfactants CTAB and sodium salicylate (NaSal) as structure-directing agents, TEOS as a source of silica, and triethanolamine (TEA) as a catalyst. This is how an MSN was typically synthesized. The ratio of NaSal to CTAB was adjusted to obtain MSN with different particle sizes, and ratios of 0.7:1, 0.5:1, and 0.25:1 (mol/mol) yielded lMSN, mMSN, and sMSN, respectively. First, 0.070 g of TEA was added to 25 mL of ultrapure water and constantly stirred at 80 °C in a water bath for 0.5 h. Subsequently, CTAB and NaSal were added to the solution and constantly stirred for another 1 h. Thereafter, 4 mL of TEOS was added to the water-CTAB-NaSal-TEA solution by quickly stirring for 2 h. Finally, the product was obtained by centrifugation at 12,500 rpm for 10 min. The precipitate was washed three times with distilled water and anhydrous ethanol and mixed with 100 mL of ethanol before adding 1,500 mg of ammonium nitrate to the mixture. The suspension underwent a 12 h reaction at 80 °C before being centrifuged to extract MSNs with varying particle sizes.

2.5. Fabrication of MSN-NH2

The MSN samples with varying particle sizes were dispersed in 100 mL of ethanol solution containing 800 μL of APTES. Subsequently, the mixture underwent a reaction at a temperature of 75 °C for a period of 12 h. Following this, the suspension underwent centrifugation at a speed of 12,500 rpm for a duration of 10 min in order to gather the precipitation. The precipitate was then subjected to three rounds of washing using distilled water and anhydrous ethanol. Subsequently, the precipitate was collected once again using centrifugation at a speed of 12,500 rpm for a duration of 15 min. The resultant precipitate was given the designation MSN-NH2.

2.6. Protein loading

Probe sonication was used for 5 min (300 W; 2 s on and 2 s off) in an ice bath to disperse MSN-NH2 of various particle sizes in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Subsequently, the OVA solution was added to the dispersed MSN solution and adsorbed on the MSN surface by charge interaction using probe sonication in an ice bath for 5 min (150 W; 2 s on and 2 s off). The concentration of OVA solution for OVA/MSN preparation was 2 mg/mL, and the ratio of OVA to MSN was 2:1 (w/w). MSNs with different particle sizes for the adsorption of OVA were addressed as OVA/sMSN, OVA/mMSN, and OVA/lMSN. Excess OVA was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was used to determine encapsulation efficiency and calculate loading capacity by Braford's method. The specific operation is as follows: after incubation with the G-250 reagent prepared from the standard and the protein sample to be examined for 5 min at room temperature, a Multiskan MK3 multifunctional enzyme marker from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) was used to measure the absorbance value at 595 nm, and the content of supernatant OVA was obtained by substituting it into the working curve. The equations were shown in Eq. (1) and Eq. (2)

| (1) |

| (2) |

2.7. β-Glucan modification

In total, 25 mg of β-glucan-COOH was dissolved in 5 mL of distilled water; further, 15 mg of EDC and 10 mg of NHS were added to the solution to activate the carboxyl group of β-glucan-COOH for 2 h. Subsequently, 50 mg of OVA/MSN of different particle sizes was dispersed in an activated β-glucan-COOH solution and stirred for 24 h. Thereafter, β-glucan-modified OVA/MSN with different particle sizes (OVA/β-MSN) was obtained by centrifugation at 12,500 rpm for 10 min.

2.8. Characterization of MSN-NH2 and OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes

The particle size distributions and ζ-potentials of MSN-NH2, OVA/MSN, and OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes were measured using a Nano-ZS90 nanosizer from Malvern Instruments Ltd. (Worcestershire, UK). The morphologies of these MSNs were observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) using a Tecnai G2 F30 from FEI Company (Eindhoven, Netherlands). The OVA loading was determined using the Bradford assay, and the secondary structure of OVA released from the MSN-NH2/β-MSN of different particle sizes was characterized by MOS-450 circular dichroism (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Notably, the successful modification of β-glucan was verified by the characteristic color reaction of glucose by weighing approximately 20 mg of β-MSN, dissolving it in 10 mL of pH 7.4 PBS buffer, ultrasonically dispersing it uniformly, adding 250 μL of β-glucanase in it to reach an enzyme activity of 2.5 U/mL, and subjecting it to the enzyme reaction in a constant temperature shaker (37 °C, 150 rpm) for 2 h. After centrifugation at 12,500 rpm for 5 min, the supernatant (free glucose dissolved by the enzyme) was collected, and the aldehyde group in the glucose molecule was used to identify the modification of β-glucan on MSN of different particle sizes by the redox reaction between the aldehyde group in the glucose molecule and copper hydroxide in Benedict's reagent, which reduced the copper hydroxide to the brick-red precipitate cuprous oxide. The amount of β-glucan modification was presented by TGA-50 Thermogravimetric Analyzer (Shimadzu).

2.9. Toxicity of MSN or β-MSN of different particle sizes to DC2.4 cells

DC2.4 cells were inoculated into 96-well plates at 1 × 104 cells/well. After the cells were wall-approximated, the culture fluid in the wells was aspirated and washed three times with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were subjected to incubation with 100 μL of RPMI 1640 media that contained varying concentrations of MSN and β-MSN with distinct particle sizes. All MSN stock solutions were prepared by sonication in sterile PBS and diluted to different concentrations with RPMI 1640 medium. After 48 h of incubation, a volume of 10 μL of CCK8 was introduced into each well, subsequently followed by an additional incubation period of 2 h. Cell viability was assessed by quantifying the absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm utilizing an enzyme marker from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). In addition, we investigated the cytotoxicity comparison between MSN and MSN-NH2. Because our nano-vaccine is administered by subcutaneous injection, we also examined the cell survival of β-MSN and OVA/β-MSN on HaCaT cells. The experiment was performed in the same way as above.

2.10. Cell uptake

A total of 2 mg of FITC was introduced into the OVA solution, and the resulting mixture was subjected to stirring at a temperature of 4 °C for the duration of 12 h. The unbound FITC molecules were separated from the solution using dialysis, using dialysis bags with a molecular weight cutoff of 3,500 Da. The resulting purified FITC-OVA was then preserved by lyophilization and stored at a temperature of 4 °C, and the purified FITC-OVA was stored after lyophilization at 4 °C. FITC-OVA/MSN and FITC-OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes were prepared by sonication. MSN was loaded in the same way for FITC-OVA or OVA, as detailed in Section 2.6, and FITC-OVA/β-MSN was prepared as for OVA/β-MSN, as detailed in Section 2.7. DC2.4 cells were inoculated into 12-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well and subjected to an uptake assay. When the cells adhered to the wall, they were incubated in a 12-well plate with 10 μg of FITC-OVA, FITC-OVA/MSN, or FITC-OVA/β-MSN in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium for 2 h. Subsequently, the aforementioned cells were gathered, subjected to centrifugation, and underwent three rounds of washing with PBS. The process of flow cytometry was employed to identify and measure the uptake of antigens. The blocking assay of OVA/β-sMSN uptake by β-glucan was also verified. We pre-exposed DC2.4 to different concentrations of β-glucan for 2 h, respectively, and then discarded the β-glucan-containing medium and co-incubated it with 10 μg FITC-OVA/β-sMSN for 2 h. Subsequently, the cellular specimens were gathered, subjected to centrifugation, and subsequently rinsed thrice with PBS, and detected by flow cytometry for OVA/β-sMSN uptake.

The cellular uptake of MSN and β-MSN loaded with OVA of different particle sizes was characterized by laser confocal microscopy (CLSM). The cells were inoculated into 24-well plates at 5 × 104 cells/well. After the cells adhered to the wall, FITC-OVA/MSN and FITC-OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes were prepared into a suspension of 100 μg/mL in sterile PBS (pH 7.4) and added into the corresponding wells to continue incubation for 2 h. Subsequently, 200 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde was added to each well, and the cells were placed in a shaker for 30 min at 37 °C. Thereafter, paraformaldehyde was discarded, cells were washed with sterile PBS (pH 7.4) three times, 300 μL of Hoechst staining solution was added to each well, staining was performed for 30 min at 37 °C, cells were washed with sterile PBS (pH 7.4) three times again, and the appropriate concentration of sealing solution was added onto the slide with a drop of forceps. Further, the cells were removed and inverted on the slide so that their surface was in contact with the blocking solution; thereafter, the fixed cells were observed using a Nikon C2+ Laser Confocal Microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

2.11. Antigen cross-presentation of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes in vitro

DC2.4 cells were inoculated in 12-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. When the cells were adherent, they were incubated for 24 h in 1 mL complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 20 μg of OVA or loaded with 20 μg of OVA with different particle sizes of MSN or β-MSN. After that, the cellular specimens were gathered, subjected to three rounds of PBS rinsing, and subsequently labeled with allophycocyanin conjugated anti-mouse SIINFEKL/H-2Kb antibody from Annoron Biotechnology (Beijing, China). The resulting samples were then assessed for cross-presentation using flow cytometry.

2.12. Adjuvant properties of MSN or β-MSN of different particle sizes in vitro

BMDCs cultured for 6 days were inoculated at 2 × 105 cells/well into 12-well plates and incubated with 100 μg of MSN or β-MSN of different particle sizes for 24 h. Notably, the cells that were treated with PBS were employed as negative controls. Following that, the cells were gathered, rinsed three times with PBS, and subjected to staining with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD80 antibody and allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-mouse CD86 antibody. Flow cytometry technique was employed to determine the simultaneous expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on the surface of BMDCs.

2.13. LN distribution of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes in vivo

In order to examine the efficacy of targeting ability of different particle sizes of OVA/MSN and OVA/β-MSN, 20 μg of near-infrared fluorescent dyes (1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DIR)) labeled DIR-OVA or MSN/β-MSN loaded with 20 μg of DIR-OVA was subcutaneously injected into the hind foot pads of mice (n = 3 animals per group). The inguinal LNs were visualized at designated time points using the IVIS Lumina Series III In Vivo Imaging System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Following a period of 24 h, the inguinal LNs were extracted for ex vivo imaging. The study consisted of three animals per group. The quantification of fluorescence intensity at the inguinal LNs was performed using Living Image 4.3.1 software, which was provided by IVIS Lumina Series III.

2.14. Animal immunization

The administration of all immunisations was conducted through subcutaneous injection into the hind foot pads using a microsyringe. Each preparation contained 20 μg of OVA. Booster immunizations were administered on day 7 after the initial immunization (day 0). Mice were sacrificed on day 14, inguinal LNs were collected (n = 2–3 animals per group), and LN cell suspensions were obtained by tissue grinding for antibody detection.

2.15. In vivo safety evaluation

Twenty-one days following the initial immunization, the mice were euthanized, and their heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys were extracted and then submerged immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde. The treated tissues were subsequently embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Under light microscopy, inflammatory reactions and pathological changes were observed.

2.16. Statistical analysis

The data were represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The unpaired, two-tailed t-test was employed to identify noteworthy distinctions between the two groups, while the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was utilized for comparing numerous groups, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 (ns: no significance).

3. Results

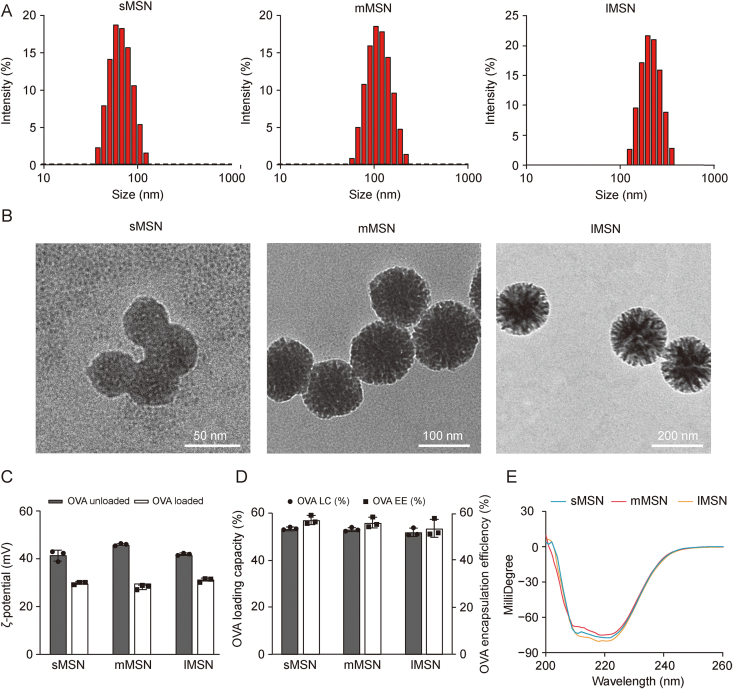

3.1. Characterization of MSN and OVA/MSN of different particle sizes

Fig. 2A and Table S1 show the average hydrodynamic diameters of sMSN, mMSN, and lMSN. The morphology of MSNs with different particle sizes was observed using TEM (Fig. 2B). The results indicated that sMSN, mMSN, and lMSN were uniformly spherical, with average diameters of 50, 100, and 200 nm, respectively. When MSN adsorbed OVA, the ζ-potential was significantly decreased (Fig. 2C); this decrease could be attributed to the combination of the carboxyl group in OVA with the amino group on the surface of MSN, which decreased the positive charge density on the surface of MSN. In addition, capacity and encapsulation efficiency of sMSN, mMSN, and lMSN were calculated using Bradford's method to be >50% (Fig. 2D and Table S2), but there were no significant differences. Verifying the effect of differences in particle size on the ability to target LNs and activate DCs is more convincing. In addition, after the adsorption of OVA by MSN with different particle sizes, to ensure that the spatial structure of OVA did not change, the secondary structure change of OVA released from the surface of MSN was verified by circular dichroism. The results (Fig. 2E) revealed that the adsorption of OVA by MSN with different particle sizes did not affect the spatial structure of OVA.

Fig. 2.

Physicochemical characterization of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) with different particle sizes. (A) The distribution of hydrodynamic diameters. (B) Transmission electron micrographs. (C) ζ-potential of MSN with different particle sizes loaded with or without ovalbumin (OVA). (D) OVA loading capacity (LC) and encapsulation efficiency (EE). (E) Secondary structure of OVA released from MSNs with different particle sizes. sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN.

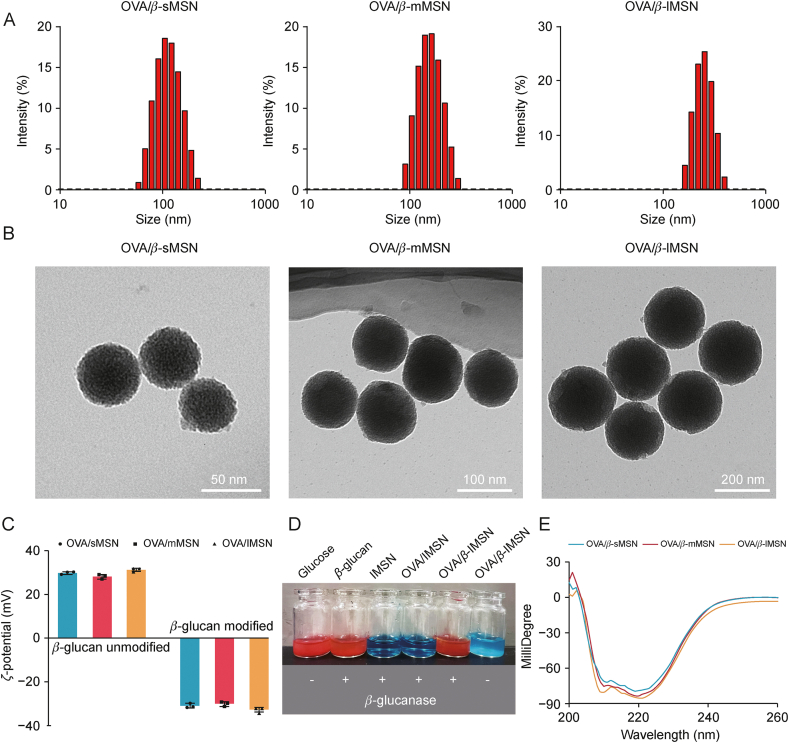

3.2. Characterization of OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes

Fig. 3A and Table S3 show the average hydrodynamic diameters of OVA/β-sMSN, OVA/β-mMSN, and OVA/β-lMSN after the modification of β-glucan. OVA/β-MSN morphology with different particle sizes was observed using TEM (Fig. 3B). The results indicated that after the modification of β-glucan, carriers of different particle sizes remain uniformly spherical, and the average diameter increased by approximately 20 nm, suggesting the successful modification of β-glucan. The ζ-potential of OVA/MSN with different particle sizes was approximately 31.3 ± 0.76 mV, which was attributed to the presence of a large number of amino groups on the surface of OVA/MSN. After the modification of β-glucan, the ζ-potential of OVA/β-MSN became −32.7 ± 1.15 mV; this was attributed to the involvement of carboxyl groups, which confirmed the additional effect of β-glucan (Fig. 3C). The color reaction is a characteristic reaction for qualitative testing of glucose, which is based on the principle that the aldehyde group in the glucose molecule can undergo a redox reaction with copper hydroxide in Benedict's reagent, reducing the copper hydroxide to a brick-red precipitate of cuprous oxide. As shown in Figs. 3D and S2, the reaction of glucose with Benedict's reagent transformed the blue Cu2+ solution into a brick-red Cu+ solution. β-lMSN hydrolyzed by β-glucanase transformed the blue Cu2+ solution into a red solution, consistent with the results of the color reaction of the β-glucan plus enzyme-treated positive control group, whereas mMSN and sMSN transformed the blue Cu2+ solution into orange and green solutions, respectively. This was attributed to the fact that the results of the color reaction are related to the amount of glucose, which produces a brick-red precipitate when the glucose content is high, whereas the solution changes to orange or green when the glucose content is low. These results directly prove the successful establishment of β-MSN. Finally, the spatial structure change of OVA released from β-glucan-modified MSN was verified, as shown in Fig. 3E. In addition, OVA maintains a similar spatial structure, proving that the modification of β-glucan does not affect the secondary structure change of OVA. The amount of modification of β-glucan was determined by TGA. Fig. S3 shows that OVA/β-sMSN β-glucan was modified by 11.063%, OVA/β-mMSN β-glucan by 15.729% and OVA/β-lMSN β-glucan by 17.506%. All of the aforementioned findings, whether direct or indirect, provide evidence for the successful development of OVA/β-MSN with varying particle sizes.

Fig. 3.

Physicochemical characterization of β-glucan modified ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/β-MSN) with different particle sizes. (A) The distribution of hydrodynamic diameters. (B) Transmission electron micrographs. (C) ζ-potential of ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/MSN) with different particle sizes of modified or unmodified β-glucan. (D) Glucose color reaction to demonstrate the hydrolysis process of β-glucan modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles (β-MSN) under β-glucanase. (E) Secondary structure of ovalbumin (OVA) released from β-MSN with different particle sizes. sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN.

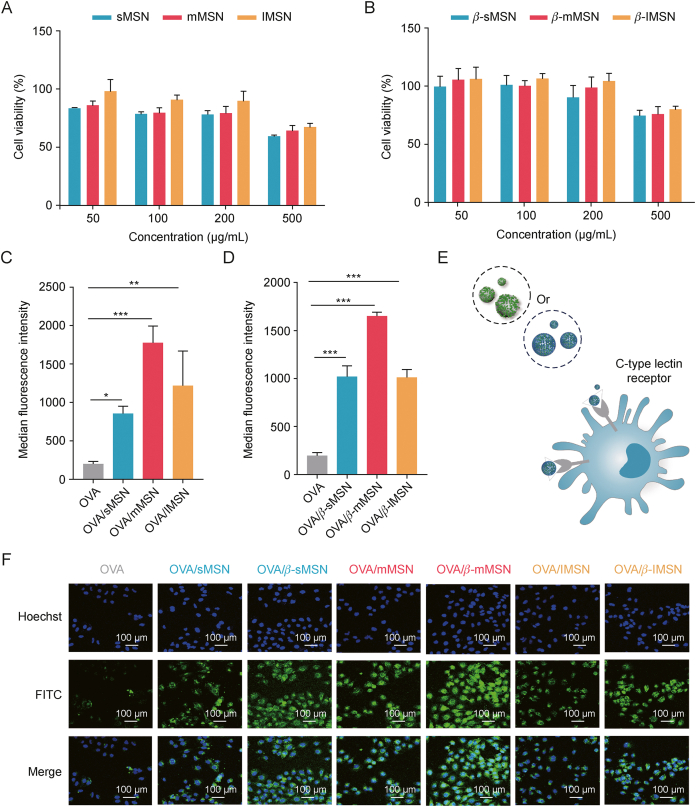

3.3. Cellular toxicity and uptake of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes in vitro

We investigated the toxicity of MSN versus β-MSN with different particle sizes and the uptake characteristics of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes in vitro. We found that the viability of DC2.4 cells was associated with the modification of β-glucan on the MSN surface (Figs. 4A and B). At concentrations of <500 μg/mL, the cell viability of sMSN, mMSN, and lMSN was >70%, whereas that of sMSN, mMSN, and lMSN after β-glucan modification was >80%. Moreover, cell viability was maintained above 70% at a particle concentration of 500 μg/mL, suggesting a better safety profile of β-MSN than that of MSN. Furthermore, we performed a cell safety evaluation of MSN without amination modification in DC2.4 cells (Fig. S4). From the results, the cytotoxicity of MSN-NH2 was stronger than that of MSN but the difference was not significant in the range of 50–200 μg/mL. At the same time, due to our nano-vaccine is administered by subcutaneous injection, we chose HaCaT as a normal cell model to study the cytotoxicity of different particle sizes of β-MSN and OVA/β-MSN on HaCaT. The results showed that both β-MSN and OVA/β-MSN are safe for HaCaT in the 50–500 μg/mL concentration range (Fig. S5).

Fig. 4.

Cytotoxicity and cellular uptake of ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/MSN) or β-glucan modified ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/β-MSN) of different particle sizes in vitro. (A, B) Relative viability of dendritic cell (DC)2.4 cells when subjected to varying doses of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) (A) and β-glucan modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles (β-MSN) (B). (C, D) Uptake efficiency of OVA/MSN (C) and OVA/β-MSN (D) of different particle sizes by DC2.4 cells by flow cytometry. (E) Mechanism by which MSN with β-glucan encapsulation is more readily captured by DC via the C-type lectin receptor. (F) Uptake efficiency of OVA/MSN and OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes by DC2.4 cells using laser confocal microscopy. ∗P < 0.05,∗∗P < 0.01,∗∗∗P < 0.001. OVA: ovalbumin; sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate.

Subsequently, we labeled OVA with FITC dye and evaluated the differences in the uptake of OVA, OVA/MSN with different particle sizes, and OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes in DC2.4 cells. The results revealed that the involvement of MSN significantly improved the efficiency of OVA absorption by DC2.4 cells. indicating that the uptake of mMSN was better and that β-glucan modification significantly increased the effectiveness of OVA internalization by DC2.4 cells (Figs. 4C and D). This may be attributed to the ability of β-glucan to specifically bind to the C-type lectin receptor [25] on the surface of DC2.4 cells (Fig. 4E). In addition, the uptake experiments were qualitatively verified by CLSM, and the results were consistent with those of flow cytometry (Fig. 4F). We then verified the blocking effect of β-glucan on OVA/β-MSN uptake. Surprisingly, in Fig. S6, the uptake of OVA/β-sMSN was significantly increased by DC2.4 incubated with low (0.1 μM/L) and medium (0.5 μM/L) concentrations of β-glucan compared to the untreated group, whereas there was no significant change in the uptake of OVA/β-sMSN by DC2.4 incubated with a high (1 μM/L) concentration of β-glucan. When DC2.4 was incubated with 2 μM/L β-glucan, the uptake of OVA/β-sMSN was further decreased. This is because β-glucan in the low concentration range can promote antigen uptake by DCs. When the concentration of β-glucan was 1 μM/L, the Dectin-1 receptor was saturated, and the process of antigen recognition and uptake by β-glucan-pretreated DC through the Dectin-1 receptor was blocked, thus decreasing the uptake efficiency of antigen. When the concentration was further increased, DC2.4 first took up sufficient β-glucan and the uptake reached saturation, further reducing the ability to take up the antigen. Thus, our OVA/β-MSN can indeed be specifically taken up by DCs, while the Dectin-1 receptor has saturable.

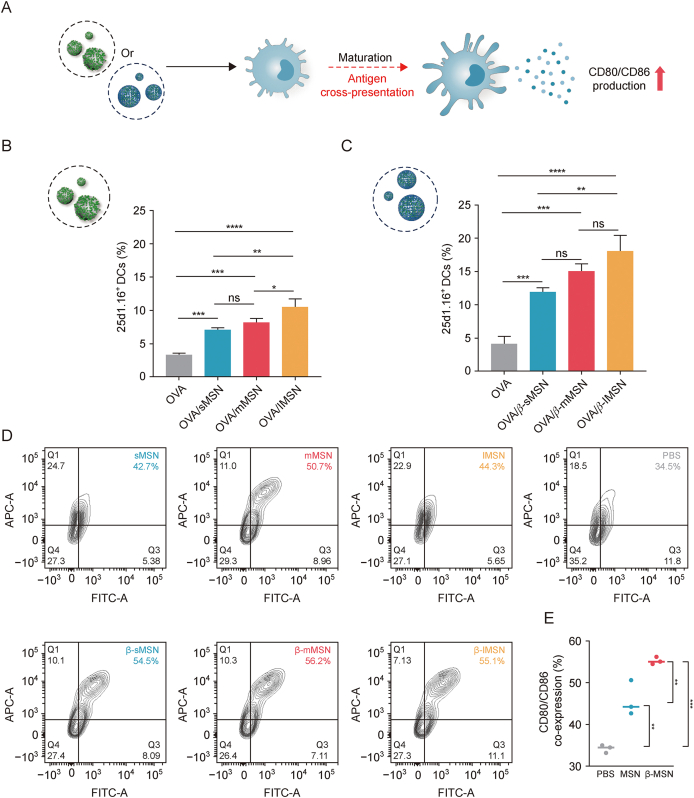

3.4. Cellular cross-presentation and adjuvant properties of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes in vitro

The presentation of short peptides by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I enables CD8+ T cells to monitor tumors and intracellular pathogens [26]. However, immature DCs have limited ability to cross-present and therefore need to mature in order to effectively induce expansion of CD8+T cells [27] (Fig. 5A). Therefore, we first investigated the cross-presentation properties of OVA/MSN in vitro. The evaluation of antigen cross-expression was conducted using flow cytometry analysis, specifically by observing the H-2Kb-SIINFEKL complex on the surface of dendritic cells. This complex was identified using the phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated monoclonal antibody 25d1.16. The findings of the study demonstrated that the administration of OVA/sMSN, OVA/mMSN, and OVA/lMSN resulted in a significant increase in the fraction of 25d1.16-positive cells, with fold changes of 2.2, 2.5, and 3.2, respectively, compared with free OVA, whereas OVA/β-sMSN, OVA/β-mMSN, and OVA/β-lMSN increased the proportion of 25d1.16-positive cells by 2.9-, 3.6-, and 4.4-fold, respectively (Figs. 5B and C). Overall, these results suggest that MSN enhanced DC cross-presentation with the involvement of MSN and that the modification of β-glucan made the promotion even more significant. In order to evaluate the capacity of β-MSN to stimulate the maturation of BMDCs, an examination was conducted to determine the presence of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on the surface of BMDCs. The expression of these factors was significantly elevated by all MSN preparations in comparison to PBS, as shown in Figs. 5D and E, suggesting their potential as adjuvants. The findings of this study provide confirmation of the capacity of β-MSN to augment the efficacy of antigen cross-presentation, while also successfully stimulating BMDCs.

Fig. 5.

Regulatory role of dendritic cells (DCs) by ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/MSN) or β-glucan modified ovalbumin-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/β-MSN) of different particle sizes in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of DCs maturation induced by OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN and treated for antigen cross-presentation. (B, C) Cross-presentation of ovalbumin (OVA) in DC2.4 cells. OVA/MSN (B) and OVA/β-MSN (C). (D) Co-expression of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) after 24 h of incubation with OVA or different MSN formulations. (E) Ability of mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) and β-glucan-modified MSNs (β-MSNs) to promote BMDC maturation. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ns: no significance. sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN; FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate; APC: antigen-presenting cell.

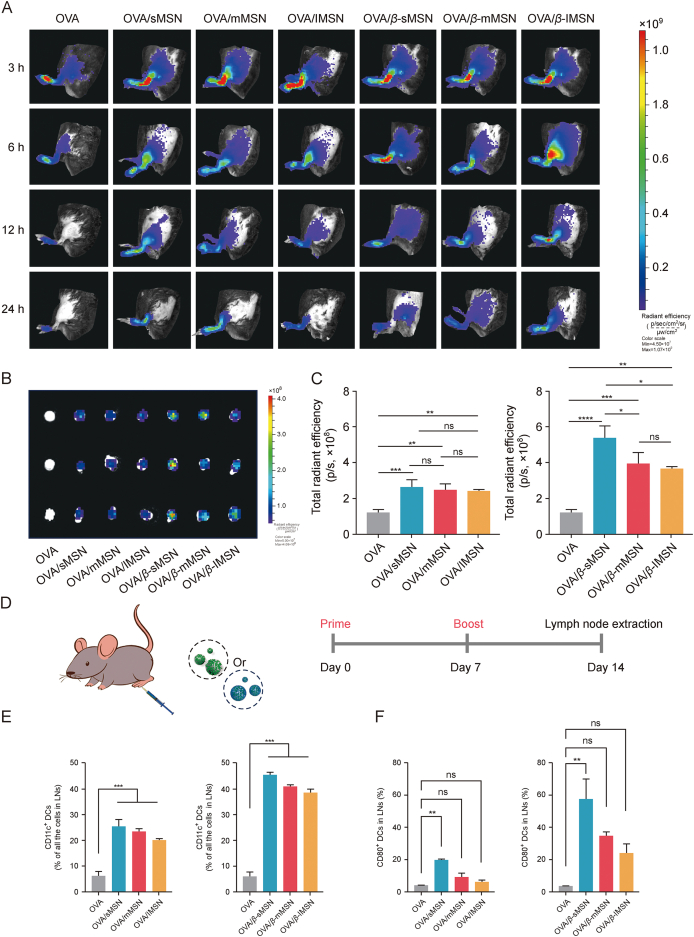

3.5. Ability of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes to target lymph node drainages and activate DCs in vivo

Considering the fact that lymph nodes are the main site for the initiation of adaptive immune responses [28], we evaluated the ability of MSNs with different particle sizes and surface properties (β-glucan modified) to target them. The hind foot pads of mice were subjected to subcutaneous injection using free DIR-OVA, DIR-OVA/MSN, or DIR-OVA/β-MSN, and subsequent observations were made at various time intervals utilizing the IVIS spectrum system. The earliest observation of fluorescent signals originating from free DIR-OVA was made in the popliteal LNs, followed by an immediate decline subsequent to injection. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the fluorescence intensity of DIR-OVA/MSN or DIR-OVA/β-MSN exhibited a consistent upward trend, reaching its maximum level at the 6 h mark following injection, as depicted in Fig. 6A. Fig. 6B displays ex vivo images of inguinal LNs, whereas Fig. 6C presents images depicting the semi-quantification of fluorescence intensity in the same LNs. The results reveal that sMSNs have excellent LN targeting ability, whereas β-glucan-modified MSNs have long-lasting retention ability and can improve nanoimmunotherapy.

Fig. 6.

Targeting draining lymph nodes with the recruitment and activation of dendritic cells (DCs) that reside in lymph nodes (LNs) by ovalbumin (OVA) by OVA-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/MSN) or β-glucan modified OVA-carrying mesoporous silica nanoparticles (OVA/β-MSN) of different particle sizes. (A) 1,1-dioctadecyl-3,3,3,3-tetramethylindotricarbocyanine iodide (DIR)-OVA/MSN or DIR-OVA/β-MSN of different particle sizes migrates from foot pads to lymph nodes (LNs) in vivo. (B) Isolation of inguinal LNs and visualization 24 h after injection. (C) Total radiant efficiency of inguinal LNs at 24 h after injection. (D) Schematic representation of the experimental design in vivo. (E) Effect of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes on DC recruitment in LNs: percentage of CD11c⁺ DCs in total LN cell population. (F) Effect of OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes on DC activation in LNs: percentage of CD80⁺ in CD11c⁺ DCs. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001, ns: no significance. All experiments were repeated two to three times. sMSN: small particle size MSN; mMSN: medium particle size MSN; lMSN: large particle size MSN.

DCs serve as a pivotal connection between the innate and adaptive immune systems, fulfilling essential functions in both the facilitation of immunological defense and the preservation of immune tolerance [29]. Therefore, we investigated the differences in the levels of DC recruitment in LNs by MSN preparations of different particle sizes. The mice were administered subcutaneous injections of 20 μg of OVA or various particle sizes of MSN and β-MSN loaded with 20 μg of OVA on days 0 and 7, as illustrated in Fig. 6D. The levels of DCs in LNs in vivo were measured, and the maturation of DCs was assessed in each group of mice on day 14. All MSN preparations induced higher DC recruitment compared with the free OVA solution. Surprisingly, the OVA/β-MSN group demonstrated a significant enhancement effect on DC recruitment in the LNs of immunized mice. Furthermore, compared with free OVA, the strongest DC maturation was triggered by OVA/β-sMSN, followed by OVA/β-mMSN and OVA/β-lMSN (Figs. 6E and F). These results indicated that OVA was significantly enhanced in terms of its effects on DC recruitment and promotion of DC maturation with the involvement of MSN, which was further enhanced by the modification of β-glucan. Twenty-one days after initial immunization, we isolated the hearts, livers, spleens, lungs, and kidneys. The isolated tissues were subjected to hematoxylin and eosin staining (Fig. S7). No significant abnormal changes were observed in any of the groups of OVA/MSNs versus OVA/β-MSNs-immunized mice compared with the OVA-immunized group. The ratio of red to white marrow in the spleen was normal, and no myocardial abnormalities were observed in any of the heart tissues. Together, these results suggest that our mode of administration and dosage do not result in systemic toxicity and OVA/MSN or OVA/β-MSN with different particle sizes has no damage to normal tissues.

4. Discussion

Induction of a humoral immune response requires antigen drainage to LNs, DC uptake, DC maturation, and cross-presentation, and maximizing the efficiency of these steps is important to achieve the optimal total immune response [[30], [31], [32], [33]]. MSNs have historically served as effective vehicles for the transportation of small-molecule nucleic acids and protein-based pharmaceuticals [34]. In recent times, there has been a growing interest in the utilization of MSNs as vehicles for vaccine administration. The effect of the particle size and surface properties of the vaccine carrier MSN on this immune response is unknown. In the current study, we prepared MSNs with different particle sizes of approximately 50, 100, and 200 nm in diameter and modified them with β-glucan. We evaluated the ability of each MSN to drain LNs against the model antigen OVA and activate DCs residing in the LNs. We found that MSNs with β-glucan modification significantly enhanced the recruitment and maturation of DCs in the LNs, and β-glucan-modified MSNs with small particle sizes demonstrated the optimal performance. In addition, because exogenous antigens are usually processed by antigen-presenting cells and presented to CD4+ T cells via MHC class II molecules, the eradication of viral infections and malignancies necessitates the induction of a CD8+ T cell response, namely by the display of exogenous antigens on MHC class I molecules, a process commonly referred to as cross-presentation [35,36]. Our β-glucan-modified MSNs demonstrated enhanced capacity for antigen cross-presentation.

The difference in particle size of the β-glucan-unmodified MSN did not significantly affect the targeting efficiency of the lymph nodes. In contrast, β-glucan-modified MSNs with small particle sizes demonstrated stronger lymphatic targeting and adjuvant properties than those with larger particle sizes (Fig. 6). Although in vitro results revealed no significant differences in the effect of particle size on DC maturation (Fig. 5), MSNs with smaller particle sizes demonstrated greater lymphatic targeting and DC recruitment than those with larger particle sizes (Figs. 5C and 6F). The stronger effect of β-glucan-modified MSNs with smaller particle sizes on DCs can be attributed to two reasons. First, the smaller particle size makes it easier to drain the MSNs into the lymphatic lumen, and the β-glucan-coated nanoparticles are more rapidly recognized and taken up by DCs in the LNs to exert adjuvant effects. Second, nanoparticles with smaller particle sizes are more bioavailable. According to reports, there exists a direct relationship between the size of pores or particles and the rate of degradation of MSN. Consequently, a smaller pore or particle size leads to an accelerated breakdown of MSN, resulting in a faster release of the encapsulated medicine [37]. Moreover, the rapid degradation of MSN may help improve its safety in vivo. It has been reported that short-rod MSNs are cleared more rapidly than long-rod MSNs in both urinary and fecal excretory pathways, and although MSNs do not cause significant toxicity in vivo, they may induce biliary excretion and glomerular filtration dysfunction [38]. Therefore, the rapid degradation rate of MSNs with smaller particle sizes contributes to biosafety and biocompatibility. In addition, MSNs with smaller particle sizes were likely more bioavailable; this finding is consistent with those of previous reports. The results of the present study indicate that an increase in particle size from ∼32 to ∼142 nm resulted in a monotonically lower systemic bioavailability, independent of the route of administration [39].

The aforementioned results suggest that β-MSNs with reduced particle sizes have promising clinical applications in vaccination. Additionally, β-glucan-modified MSNs ranging from ∼100 nm can serve as effective carriers for protein vaccines and complicated antigens. In future studies, β-MSNs with small particle sizes can be used with numerous existing antigens and an increasing number of new antigens.

5. Conclusion

Synthesized OVA/MSN and OVA/β-MSN were able to effectively target LNs, enlist DCs residing in LNs, and stimulate the maturation of LN-resident DCs. In this study, we enhanced the intensity of the immune response by modulating the properties of MSN to enhance its action on DCs, and the results indicated that ∼100 nm of β-MSN-loaded antigen promoted DC maturation more significantly without combination with other adjuvants, suggesting the potential clinical value of β-sMSN for vaccination. To the best of our knowledge, no previous reports have shown that dextran-modified MSN can induce DC recruitment and maturation in LNs without adjuvants. In future studies, β-MSN of ∼100 nm can serve as a vehicle for the administration of vaccines for adjuvants and various antigens used in different fields.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wen Guo: Experiments designation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Xinyue Zhang: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation. Long Wan: Investigation, Data curation. Zhiqi Wang: Supervision, Data curation. Meiqi Han: Supervision, Data curation. Ziwei Yan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Jia Li: Formal analysis, Investigation. Ruizhu Deng: Formal analysis, Investigation. Shenglong Li: Conceptualization, Methodology. Yuling Mao: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Siling Wang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Doctoral Start-up Foundation of Liaoning Province, China (Grant No.: 2021-BS-127) and China Medical University, China Medical University Cancer Hospital in animal experiments.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpha.2024.02.007.

Contributor Information

Yuling Mao, Email: maoyuling@syphu.edu.cn.

Siling Wang, Email: silingwang@syphu.edu.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhang Q., Zhu Y., Xu H., et al. Multifunctional nanoparticle-based adjuvants used in cancer vaccines. Prog. Chem. 2015;27:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kang Y., Li S. Nanomaterials: Breaking through the bottleneck of tumor immunotherapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023;230 doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong X., Liang J., Yang A., et al. A visible codelivery nanovaccine of antigen and adjuvant with self-carrier for cancer immunotherapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:4876–4888. doi: 10.1021/acsami.8b20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T., Zhang D., Sun D., et al. Current status of in vivo bioanalysis of nano drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Anal. 2020;10:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhardwaj P., Bhatia E., Sharma S., et al. Advancements in prophylactic and therapeutic nanovaccines. Acta Biomater. 2020;108:1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang D., Lin Z., Wu M., et al. Cytosolic delivery of thiolated neoantigen nano-vaccine combined with immune checkpoint blockade to boost anti-cancer T cell immunity. Adv. Sci. (Weinh) 2021;8 doi: 10.1002/advs.202003504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pal I., Ramsey J.D. The role of the lymphatic system in vaccine trafficking and immune response. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:909–922. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu X., Dai Y., Zhao Y., et al. Melittin-lipid nanoparticles target to lymph nodes and elicit a systemic anti-tumor immune response. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1110. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14906-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rawat K., Tewari A., Li X., et al. CCL5-producing migratory dendritic cells guide CCR5+ monocytes into the draining lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2023;220 doi: 10.1084/jem.20222129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stritt S., Koltowska K., Mäkinen T. Homeostatic maintenance of the lymphatic vasculature. Trends Mol. Med. 2021;27:955–970. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng Q., Li H., Jiang H., et al. Tailoring polymeric hybrid micelles with lymph node targeting ability to improve the potency of cancer vaccines. Biomaterials. 2017;122:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tozuka M., Oka T., Jounai N., et al. Efficient antigen delivery to the draining lymph nodes is a key component in the immunogenic pathway of the intradermal vaccine. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2016;82:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kähäri L., Fair-Mäkelä R., Auvinen K., et al. Transcytosis route mediates rapid delivery of intact antibodies to draining lymph nodes. J. Clin. Investig. 2019;129:3086–3102. doi: 10.1172/JCI125740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong X., Zhong X., Du G., et al. The pore size of mesoporous silica nanoparticles regulates their antigen delivery efficiency. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aranda F., Llopiz D., Díaz-Valdés N., et al. Adjuvant combination and antigen targeting as a strategy to induce polyfunctional and high-avidity T-cell responses against poorly immunogenic tumors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3214–3224. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiao Y., Zhang Y., Chen J., et al. A biepitope, adjuvant-free, self-assembled influenza nanovaccine provides cross-protection against H3N2 and H1N1 viruses in mice. Nano Res. 2022;15:8304–8314. doi: 10.1007/s12274-022-4482-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner J., Gößl D., Ustyanovska N., et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as pH-responsive carrier for the immune-activating drug resiquimod enhance the local immune response in mice. ACS Nano. 2021;15:4450–4466. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown T.D., Whitehead K.A., Mitragotri S. Materials for oral delivery of proteins and peptides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019;5:127–148. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao Y., Han M., Chen C., et al. A biomimetic nanocomposite made of a ginger-derived exosome and an inorganic framework for high-performance delivery of oral antibodies. Nanoscale. 2021;13:20157–20169. doi: 10.1039/d1nr06015e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tian J., Ma J., Wang S., et al. Increased expression of mGITRL on D2SC/1 cells by particulate β-glucan impairs the suppressive effect of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells and enhances the effector T cell proliferation, Cell. Immunol. 2011;270:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintin J., Saeed S., Martens J.H.A., et al. Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rappleye C.A., Eissenberg L.G., Goldman W.E. Histoplasma capsulatum alpha-(1, 3)-glucan blocks innate immune recognition by the beta-glucan receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1366–1370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609848104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao Y., Wang X., Chen C., et al. Immune-awakening Saccharomyces-inspired nanocarrier for oral target delivery to lymph and tumors. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022;12:4501–4518. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y., Bernardi S., Song H., et al. Anion assisted synthesis of large pore hollow dendritic mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles: Understanding the composition gradient. Chem. Mater. 2016;28:704–707. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qi C., Cai Y., Gunn L., et al. Differential pathways regulating innate and adaptive antitumor immune responses by particulate and soluble yeast-derived β-glucans. Blood. 2011;117:6825–6836. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-339812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rock K.L., Reits E., Neefjes J. Present yourself! by MHC class I and MHC class II molecules. Trends Immunol. 2016;37:724–737. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han S., Ma W., Jiang D., et al. Intracellular signaling pathway in dendritic cells and antigen transport pathway in vivo mediated by an OVA@DDAB/PLGA nano-vaccine. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2021;19:394. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-01116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y., De Koker S., De Geest B.G. Engineering strategies for lymph node targeted immune activation. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:2055–2067. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu J., Zhang X., Cheng Y., et al. Dendritic cell migration in inflammation and immunity. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021;18:2461–2471. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00726-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas S.N., Vokali E., Lund A.W., et al. Targeting the tumor-draining lymph node with adjuvanted nanoparticles reshapes the anti-tumor immune response. Biomaterials. 2014;35:814–824. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian Y., Jin H., Qiao S., et al. Targeting dendritic cells in lymph node with an antigen peptide-based nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2016;98:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang H., Wang Q., Sun X. Lymph node targeting strategies to improve vaccination efficacy. J. Control. Release. 2017;267:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim S.Y., Noh Y.W., Kang T.H., et al. Synthetic vaccine nanoparticles target to lymph node triggering enhanced innate and adaptive antitumor immunity. Biomaterials. 2017;130:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luther D.C., Huang R., Jeon T., et al. Delivery of drugs, proteins, and nucleic acids using inorganic nanoparticles. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020;156:188–213. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong X., Zhong X., Du G., et al. The pore size of mesoporous silica nanoparticles regulates their antigen delivery efficiency. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li H., Gou R., Liao J., et al. Recent advances in nano-targeting drug delivery systems for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Acta Mater. Med. 2023;2:23–41. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen D., Yang J., Li X., et al. Biphase stratification approach to three-dimensional dendritic biodegradable mesoporous silica nanospheres. Nano Lett. 2014;14:923–932. doi: 10.1021/nl404316v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S.D., Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol. Pharm. 2008;5:496–504. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dogra P., Adolphi N.L., Wang Z., et al. Establishing the effects of mesoporous silica nanoparticle properties on in vivo disposition using imaging-based pharmacokinetics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4551. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06730-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.