Abstract

Through morphological and molecular studies, the natural life cycle of Taenia talicei Dollfus, 1960 (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from Argentine Patagonia is elucidated, involving subterranean rodents (Ctenomyidae) as intermediate hosts, and the Andean fox Lycalopex culpaeus (Canidae) as definitive host. Metacestodes (mono- and polycephalic fimbriocerci) were found mainly in the peritoneal cavity of Ctenomys terraplen, and the strobilate adult in the intestine of L. culpaeus. Correspondence between metacestodes and strobilate adults was based primarily on number, size and shape of rostellar hooks: 45–53 hooks alternated in two rows, small hooks 88–180 μm long and large hooks 230–280 μm long, with the characteristic shape described in the two main description of the species, both that of the metacestode (original description) and that of the strobilate adult (obtained experimentally). Further genetic analysis (cox1 gene mtDNA) corroborated the conspecificity between the metacestodes and the strobilate adults found in the Andean fox in the same study area. Genetic analysis also revealed conspecificity of the taxon found in Patagonia with the species registered in GenBank as T. talicei, obtained from different intermediate and definitive hosts from Peru and Argentina. Taenia talicei was previously reported from Argentina in the form of metacestodes naturally infecting two other species of Ctenomys. However, the strobilate adult was only described from the experimental infection of a domestic dog. Hence, this is the first report of the natural life cycle of T. talicei and of a species of Taenia endemic from South America.

Keywords: Taenia, Life cycle, Ctenomys, Lycalopex, Cox1, Argentina

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Ctenomys spp. (Rodentia) act as intermediate hosts of T. talicei in Argentinian Patagonia.

-

•

Mono- and polycephalic fimbriocerci coexisted in the ctenomyid host.

-

•

Adults of T. talicei naturally infect Patagonian Andean foxes Lycalopex culpaeus.

-

•

Taenia talicei is sister group of Taenia tianguangfui and Taenia polyacantha.

1. Introduction

The genus Taenia Linnaeus, 1758 is one of the most studied tapeworms, but its taxonomy, systematics, and species still remain controversial and conflicting (Ganzorig and Gardner, 2024). Species of the genus are not easily identified by morphological means, since many of the characters overlap. This does not so much apply to the few human parasitic species, but rather to those from carnivores, particularly when several species occur in one host species within a given geographical area (Loos-Frank, 2000). Identification of species and separation from the rest is possible using molecular methods, but they must have been previously correctly described by morphological methods. Verster (1969) published her invaluable revision of Taenia and not only set standards on important and less important characters but also decided on the taxonomy and validity of species (Loos-Frank, 2000).

Phylogeny is fundamental as it constrains explanations about history and forms our foundation for recognizing and diagnosing species. In the absence of such a framework taxonomists historically relied on intuitive processes, personal judgment and authority, often embracing a typological view of species that disregarded otherwise unequivocal historical and biological criteria (Hoberg, 2006). During the last ten years, researchers have made several contributions on the phylogeny of these important parasites (e.g., Hoberg, 2006; Lavikainen et al., 2008, 2016; Haukisalmi et al., 2011; Nakao et al., 2013; Terefe et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016; Arrabal et al., 2017, 2023; Wu et al., 2021; Bagnato et al., 2022, 2023; Shanebeck et al., 2024). The cestode family Taeniidae actually consists of four valid genera, Taenia, Hydatigera Lamarck, 1816; Versteria Nakao, Lavikainen, Iwaki, Haukisalmi, Konyaev, Oku, Okamoto and Ito (2013) and Echinococcus Rudolphi, 1801 Nakao et al., (2013). The genus Echinococcus is monophyletic due to a remarkable similarity in morphology, features of development and genetic makeup. By contrast, Taenia is a highly diverse group formerly made up of different genera. Recent molecular phylogenetic analyses strongly suggest the paraphyly of Taenia (Nakao et al., 2013).

Species of Taenia have a life cycle that requires two obligate mammalian hosts, an intermediate herbivore and a definitive terrestrial carnivore. Taenia species have worldwide distribution, although endemic species are known from each zoogeographic region (Ganzorig and Gardner, 2024). The cysticercus is the characteristic metacestode of the taeniids (Chervy, 2002), but a small group of Taenia species (e.g. T. selousi Mettrick, 1962; T. endothoracicus (Kirschenblatt, 1948); T. twitchelli (Schwartz, 1927) shows metacestodes of the polycephalic type, characterized by scoleces with elongate stalks arising by exogenous budding from a central bladder that later regresses. These polycephalic metacestodes, as well as the fimbriated metacestodes or fimbriocerci (elongate, unsegmented metacestodes with characteristic folds, e.g., T. martis, T. polyacantha, T. twitchelli) are derived with respect to the cysticercus, though their ontogenetic relationships and homology are uncertain (Rausch and Fay, 1988; Hoberg et al., 2000; Chervy, 2002).

In 1954, Voge reported the finding of taeniid metacestodes in the peritoneal cavity of the rodents Ctenomys peruanus Sanborn and Pearson (Ctenomyidae), Phyllotis osilae Allen and Chinchillula sahamae Thomas (Cricetidae) from Peru. She paid special attention to the exogenous proliferation exhibited by these metacestodes, and suggested that such type of asexual, metacestodes multiplication, as observed in all specimens studied, and in three species of rodents, should be interpreted as a normal part of the development of this taeniid. She left pending, however, the specific identification of the metacestodes described, until more was known about the strobilate adults of taeniids in the High Andes (Voge, 1954). A few years later, Dollfus (1960) described Taenia talicei Dollfus (1960) based on metacestodes recovered from the peritoneal cavity of Ctenomys torquatus Lichtenstein from Uruguay. Twenty-eight years later, in 1988, Rausch and Gardner identified metacestodes (“multi-strobilate larvae”) in mesenteries of Ctenomys opimus Wagner in Bolivia that they identified as T. talicei (Gardner et al., 2021). Five decades passed from the publication of Dollfus (1960) until Rossin et al. (2010), in Argentina, redescribed the species based on metacestodes (cysticerci, fimbriocerci and polycephalic larvae) found in the peritoneal cavity of Ctenomys australis (Rusconi) and Ctenomys talarum Thomas from Buenos Aires province, and strobilate adults obtained through experimental infection of a domestic dog with some of those metacestodes. Latter was the first description of the strobilate adult of this Taenia species (Rossin et al., 2010).

More recent publications on T. talicei are lacking. Notwithstanding, there are unpublished sequences (Table 1) attributed to this species available in GenBank [30 nucleotide sequences, of which 13 correspond to the NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 gene (nad1) and 17 to cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1)]. Such sequences are derived from strobilate adults recovered from Andean foxes and domestic dogs (definitive hosts) and from metacestodes recovered from Lagidium peruanum Meyen (Chinchillidae), Phyllotis xanthopygus (Waterhouse) from Peru and Ctenomys tuconax Thomas from Argentina (intermediate hosts).

Table 1.

Taeniid taxa included in the phylogenetic analysis with information on mammal host, stage, locality, GenBank accession number [partial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (Cox1) gene sequences], references and code used on phylogenetic tree; records of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) are in bold. Abbreviations: A, adult; M, metacestodes.

| Taeniid species | Mammalian host | Stage | Locality | GenBank Accession Number | References | Code on the tree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taenia Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||||

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Ctenomys terraplen (Ctenomyidae) (Ct29.1) | metacestode | Argentina (Arg) | PP738877 | This study | Taenia talicei_ Arg_PP738877_Ct29.1 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Ctenomys terraplen (Ctenomyidae) (Ct29.2) | metacestode | Arg | PP738957 | This study | Taenia talicei_ Arg_PP738957_Ct29.2 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Ctenomys terraplen (Ctenomyidae) (Ct30) | metacestode | Arg | PP738958 | This study | Taenia talicei_ Arg_PP738958_Ct30 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Lycalopex culpaeus (Canidae) (Lc5) | adult | Arg | PP738968 | This study | Taenia talicei_ Arg_PP738968_Lc5 |

| Taenia sp. | Lycalopex culpaeus (Canidae) (Lc1) | adult | Peru (Per) | MG385632 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_MG385632_Lc1 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Lycalopex culpaeus (Canidae) (Lc2) | adult | Per | MG385629 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_MG385629_Lc2 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Ctenomys tuconax (Ctenomyidae) (Ctu) | metacestode | Arg | PP050508 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Arg_PP050508_Ctu |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Phyllotis xanthopygus (Cricetidae) (Px1) | metacestode | Per | PP050507 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_PP050507_Px1 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Phyllotis xanthopygus (Cricetidae) (Px2) | metacestode | Per | PP050506 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_PP050506_Px2 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Canis lupus familiaris(Canidae) (Clf1) | adult | Per | PP050501 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_PP050501_Clf1 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Canis lupus familiaris(Canidae) (Clf2) | adult | Per | PP050498 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_PP050498_Clf2 |

| T. taliceiDollfus (1960) | Lagidium peruanum (Chinchillidae) (Lp) | metacestode | Per | PP050500 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (unpublished) | Taenia talicei_ Per_PP050500_Lp |

| T. arctosHaukisalmi et al. (2011) | Alces alces (Cervidae) (Aa) | metacestode | Finland (Fin) | GU252131 | Lavikainen et al. (2010) | Taenia arctos_Fin_GU252131_Aa |

| T. arctos Haukisalmi, Lavikainen, Laaksonen and Meri, 2012 | Ursus arctos horribilis (Ursidae) (Uah) | adult | United States (USA) | KF356387 | Catalano et al. (2014) | Taenia arctos_USA_KF356387_Uah |

| T. asiatica Eom and Rim, 1993 | Human (Hu) | adult | Japan (Jap) | LC405943 | Yamasaki et al. (2021) | Taenia asiatica_Jap_LC405943_Hu |

| T. caixuepengi Wu2021 | Ochotona curzoniae (Ochotonidae) (Oc) | metacestode | China (Chi) | MT882036 | Wu et al. (2021) | Taenia caixuepengi_Chi_MT882036_Oc |

| T. crassiceps (Zeder, 1800; Rudolphi, 1810 | ? | ? | Canada (Can) | NC_002547 | Le et al. (2000) | Taenia crassiceps_Can_NC_002547 |

| T. crocutae Mettrick and Beverly-Burton, 1961 | Crocuta crocuta (Hyaenidae) (Cc) | adult | Africa (Afr) | NC_024591 | Terefe et al. (2014) | Taenia crocutae_Afr_NC_024591_Cc |

| T. hydatigena Pallas, 1766 | Ovis sp. (Bovidae) (Ov) | metacestode | Chi | NC_012896 | Jia et al. (2010) | Taenia hydatigena_Chi_NC_012896_Ov |

| T. krabbei Moniez, 1879 | Vulpes lagopus (Canidae) (Vl) | adult | Norway (Nor) | EU544576 | Lavikainen et al. (2008) | Taenia krabbei_Nor_EU544576_Vl |

| T. laticollis Rudolphi, 1819 | ? | adult | Fin | AB731727 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Taenia laticollis_Fin_AB731727 |

| T. lynciscapreoliHaukisalmi et al. (2016) | Lynx lynx (Felidae) (Ll) | adult | Fin | JX860629 | Haukisalmi et al. (2016) | Taenia lynciscapreoli_ Fin_ JX860629_ Ll |

| T. madoquae (Pellegrini, 1950) | ? | adult | Kenya (Ken) | AB731726 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Taenia madoquae_Ken_AB731726 |

| T. martis (Zeder, 1803) | ? | metacestode | Croatia (Cro) | AB731758 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Taenia martis_Cro_AB731758 |

| T. multiceps Leske, 1780 | Canis lupus familiaris(Canidae) (Clf) | adult | Chi | NC_012894 | Jia et al. (2010) | Taenia multiceps_Chi_NC_012894_Clf |

| T. omissa Lühe, 1910 | Puma concolor(Felidae) (Pc) | adult | Per | KR095314 | Gomez-Puerta et al. (2016) | Taenia omissa_Per_KR095314_Pc |

| T. omissa Lühe, 1910 | Puma concolor(Felidae) (Pc) | adult | Arg | OQ921988 | Arrabal et al. (2023) | Taenia omissa_Arg_OQ921988_Pc |

| T. ovis (Cobbold, 1896) | Ovis sp. (Bovidae) (Ov) | metacestode | New Zealand (NZ) | AB731675 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Taenia ovis_NZ_AB731675_Ov |

| T. pisiformis (Bloch, 1780) | Canis lupus familiaris (Canidae) (Clf) | adult | Chi | NC_013844 | Jia et al. (2010) | Taenia pisiformis_Chi_NC_013844_Clf |

| T. polyacantha Leuckart, 1856 | Vulpes vulpes (Canidae) (Vv) | adult | Turkey (Tur) | MN067543 | Erol et al. (2021) | Taenia polyacantha_Tur_MN067543_Vv |

| T. regis Baer, 1923 | Panthera leo (Felidae) (Pl) | adult | Afr | NC_024589 | Terefe et al. (2014) | Taenia regis_Afr_NC_024589_Pl |

| T. saginata Goeze, 1782 | Human (Hu) | adult | Belgium (Bel) | NC_009938 | Jeon et al. (2007) | Taenia saginata_Bel_NC_009938_Hu |

| T. serialis (Gervais, 1847) | ? | adult | Australia (Aus) | AB731674 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Taenia serialis_Aus_AB731674 |

| T. solium Linnaeus, 1758 | Sus scofra domesticus (Suidae) | metacestode | Ecuador (Ec) | AB066491 | Nakao et al. (2002) | Taenia solium_Ec_AB066491_Ssd |

| T. tianguangfuiWu, Li L., Fan, Ni, Ohiolei, Li W. H., Li J. Q., Zhang, Fu, Yan and Jia (2021) | Neodon fuscus (Cricetidae) (Nf) | metacestode | Chi | MT882037 | Wu et al. (2021) | Taenia tianguangfui_Chi_MT882037_Nf |

| T. twitchelli Schwartz, 1924 | Gulo gulo (Mustelidae) (Gg) | adult | Rusia (Rus) | EU544598 | Lavikainen et al. (2008) | Taenia twitchelli_Rus_ EU544598_Gg |

| Hydatigera Lamarck, 1816 | ||||||

| H. kamiyai Iwaki, 2016 | Apodemus flavicollis (Muridae) (Af) | metacestode | Serbia (Ser) | OQ569731 | Lavikainen et al. (2016) | Hydatigera kamiyai_Ser_ OQ569731_Af |

| H. krepkogorski Schulr and Landa, 1934 | ? | metacestode | Chi | AB731762 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Hydatigera krepkogorski_Chi_AB731762 |

| H. parva Baer, 1926 | ? | metacestode | Chi | AB731763 | Catalano et al. (2019) | Hydatigera parva_Chi_AB731763 |

| H. taeniformis Batsch, 1786 | Mastomys huberti (Muridae) (Mh) | metacestode | Senegal (Sen) | MH036507 | Nakao et al. (2013) | Hydatigera taeniaeformis_Sen_ MH036507_Mh |

| Echinococcus Rudolphi, 1801 | ||||||

| E. multilocularis Leuckart, 1863 | Vulpesspp. (Canidae) (Vu) | adult | USA | AB461419 | Nakao et al. (2009) | Echinococcus multilocularis_USA_AB461419_Vu |

| E. oligarthrus (Diesing, 1863) | Puma concolor(Felidae) (Pc) | adult | Arg | KX129804 | Arrabal et al. (2017) | Echinococcus oligarthrus_Arg_KX129804_Pc |

| E. ortleppi López-Neyra and Soler Planas, 1943 | Cattle (Ca) | hydatid cyst | Arg | NC_011122 | Nakao et al. (2007) | Echinococcus ortleppi_Arg_NC_011122_Ca |

| VersteriaNakao, Lavikainen, Iwaki, Haukisalmi, Konyaev, Oku, Okamoto and Ito, 2013 | ||||||

| V. cuja Bagnato, Gilardoni and Digiani, 2022 | Galictis cuja (Mustelidae) (Gc) | adult | Arg | OL345572 | Bagnato et al. (2022) | Versteria_cuja_Arg_OL345572_Gc |

| V. cuja Bagnato, Gilardoni and Digiani, 2022 | Ctenomys terraplen (Ctenomyidae) (Ct) | metacestode | Arg | ON980784 | Bagnato et al. (2022) | Versteria_cuja_Arg_ON980784_Ct |

| V. mustelae (Gmelin, 1790) | Eospalax baileyi (Spalacidae) (Eb) | metacestode | Chi | KC898934 | Zhao et al. (2014) | Versteria_mustelae_Chi_KC898934_Eb |

| V. mustelae (Gmelin, 1790) | Myodes rufocanus (Cricetidae) (Mruf) | metacestode | Rus | EU544570 | Lavikainen et al. (2008) | Versteria_mustelae_Ru_EU544570_Mruf |

| V. mustelae (Gmelin, 1790) | Mustela lutreola (Mustelidae) (Ml) | adult | Spain (Spa) | MH431789 | Fournier-Chambrillon et al. (2018) | Versteria_mustelae_Sp_MH431789_Ml |

| V. rafeiShanebeck et al. (2024) | Neogale vison (Mustelidae) (Nv) | adult | Can | OR448764 | Shanebeck et al. (2024) | Versteria_rafei_Can_OR448764_Nv |

| Versteria sp. | Mustela erminea (Mustelidae) (Me) | adult | USA | KT223035 | Lee et al. (2016) | Versteria_sp_USA_KT223035_Me |

| Versteria sp. | Human (Hominidae) (Hu) | metacestode | USA | MK681866 | Lehman et al. (2019) | Versteria_sp_USA_MK681866_Hu |

| Versteria sp. | Mustela erminea (Mustelidae) (Me) | adult | USA | KT223033 | Lee et al. (2016) | Versteria_sp_USA_KT223033_Me |

| Versteria sp. | Pongo pygmaeus (Primates) (Pp) | metacestode | USA | KF303340 | Goldberg et al. (2014) | Versteria_sp_USA_KF303340_Pp |

Ctenomys terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi and Martin is an endemic tuco-tuco from open areas within the forest between Esquel and Corcovado in northwestern Chubut province (Argentina), recently described by Brook et al. (2024). The species belongs to the “magellanicus” species group, the most species-rich and widely distributed linage in Patagonia. Ctenomys terraplen inhabits open areas in Subantarctic or Andean-Patagonian forests, in sandy and clayey soil (Brook et al., 2024). To date, the only known endoparasite for C. terraplen is Versteria cuja Bagnato, Gilardoni and Digiani, 2022 (Taeniidae), in the form of metacestodes affecting several organs (Bagnato et al., 2022; 2023). In Bagnato et al. (2023) C. terraplen was consigned as Ctenomys sp. 1 because the species was not named at that moment. Within the framework of the study of Patagonian Ctenomys (Brook, in review, PhD Thesis), we had the opportunity to examine several specimens of tuco-tucos of different species from Chubut province, including eleven specimens of C. terraplen and one identified as Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen. Three of the rodents examined harbored, in the peritoneal cavity, mono and polycephalic metacestodes. These metacestodes, however, differed in several aspects (size of the scolex, number, size and shape of hooks, localization in the host) from the metacestodes of Versteria cuja from the same host species described in a previous work (Bagnato et al., 2023). In addition, the scoleces of these new metacestodes were morphologically similar to those of some strobilated adults of a taeniid species obtained by the first author from an Andean fox from the same area (unpubl. data). Morphological and molecular analyses were then conducted on these new metacestodes and on the strobilate adults found in the Andean fox, in order to investigate their relationship and that with other taeniid species. Resulting from those investigations, in this paper we shed light on the natural life cycle of T. talicei from Argentine Patagonia, provide morphological and molecular characterizations of the parasite stages found in their respective hosts, and assess the position of T. talicei in a partial phylogeny including 34 species of taeniids.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area and sample collection

Between December 2018 and June 2019 five dead specimens (three females and two males) of Lycalopex culpaeus (Lc) were collected and transported to the laboratory for standard mammalian studies and parasitological examination. Four specimens (Lc1-4) were given to us by a local farmer from the vicinity of Laguna La Zeta (42° 48.9′ S; 71° 22.9′ W); the fifth one (Lc5) was found road-killed in Los Alerces National Park (42° 58.2′ S; 71° 35′ W), near Esquel, Chubut province, Argentina. Specimen LIEB-M-1806 (Lc2) was necropsied fresh and the other ones were kept frozen at −18 °C until further examination.

In addition, between January 2018 and April 2022, 12 specimens of tuco-tucos (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae), sampled as part of FB's Doctoral Thesis were examined for parasites. Eleven tuco-tucos were identified as Ctenomys terraplen from Laguna Terraplén (42.96°S, 71.49°W), near Los Alerces National Park (LANP), Corcovado (43.54° S, 71.46° W) and areas between these two localities. Another specimen (Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen) was collected at Laguna El Cronómetro (43.24° S, 71.09° W), Chubut province, Patagonia, Argentina. All captures were made under permits provided by Dirección Fauna y Flora Silvestre from the Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería, Industria y Comercio del Chubut [Resolutions N° 098/2018, Nº 097/2019 (foxes); 1468/2019, N° 404/2021, N° 103/2023 (tuco-tucos)]. Specimens of Ctenomys were caught using Oneida Victor N° 0 traps with rubber covers and euthanized by cervical dislocation (Sikes et al., 2011). Some of the specimens were prospected for parasites fresh, others were frozen at −18 °C until examination and others were placed in 96 % ethanol directly.

All hosts were inspected for endoparasites under a Leica EZ4 stereomicroscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The gastrointestinal tract was separated into oesophagus, stomach, caecum and intestine. The body cavity, liver, pancreas, spleen, gall bladder, gonads, lungs, heart and kidneys were also examined for parasites.

2.2. Parasitological study

Both metacestodes (fimbriocerci) and strobilate adults were mostly fixed in 4 % formalin/distilled water after washing in 0.9 % saline, and preserved and stored in 70 % ethanol. Other specimens were stored directly in absolute ethanol for molecular analysis. Specimens intended for morphological study were stained with Borax carmine, Langeron's carmine or Gömöri's trichrome, dehydrated in a graduated ethanol series, cleared in eugenol and mounted in Canada balsam for examination under Leica DM500 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) light microscope. To study the rostellum and rostellar hooks in detail, rostella from several metacestodes and adults were dissected, mounted between slide and coverslip in Hoyer's and Berlese's fluids and allowed to dry.

Photographs were taken with a Leica ICC50W camera with software connected to the microscope. Measurements, unless otherwise stated, are given in micrometres (μm) as mean ± standard deviation, followed by range in parentheses. Prevalence and mean intensity were calculated following Bush et al. (1997). Mounted vouchers of metacestodes and not well clarified strobilate adult of T. talicei were deposited in the Parasitological Collection of the Laboratorio de Investigaciones en Evolución y Biodiversidad (LIEB-Pa), Esquel, Chubut province, Argentina. Complete specimens or skulls of L. culpaeus, C. terraplen and Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen were deposited in the Mammal Collection of the LIEB (LIEB-M), Esquel, Chubut province, Argentina.

2.3. DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

DNA extractions were performed on four samples: three C. terraplen metacestodes from Corcovado, and one L. culpaeus strobilate adult from Los Alerces National Park. For each sample, the Puro PB-L Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Quilmes, Argentina) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. A mitochondrial DNA region, cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene (cox1) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using previously published oligonucleotide primers (Bowles et al., 1992; Bowles and McManus, 1993a, 1993b). The forward primer sequence was 5′-TTTTTTGGGCATCCTGAGGTTTAT-3′, and the reverse primer sequence was 5′-TAAAGAAAGAACATAATGAAAATG-3'. PCRs were performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 4 μl template, 1X Master Mix-PCR Pegasus (EA0401, Biological Products, Argentina), 10 μM of each primer, and nuclease-free water. Negative controls were always included to monitor for contamination. The PCR cycle program consisted of an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s at 40 °C, 90 s at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 3 min. Amplification products were visualized by electrophoresis in 1% (w/v) Tris–borate/EDTA (TBE) agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. Amplicons were submitted for sequencing to Macrogen Inc. (South Korea) using the same primers employed for amplification.

2.4. Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

Sequences obtained from fimbriocerci of C. terraplen were aligned and compared with the cox1 sequences obtained from strobilate adults of the Andean fox using Multalin software (available at http://www.sacs.ucsf.edu/cgi-bin/multalin.py).

The sequences obtained were later deposited in GenBank and compared using BLAST (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with other 49 cox1 sequences (including strobilate adults and metacestodes) of Taenia species occurring in carnivores, ungulates and rodents, representing 34 taxa from different geographical regions (Table 1). The concatenated alignments were performed using Multiple Alignment Fast Fourier Transform (MAFFT) software (available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/mafft/summary?jobId=mafft-I20240503-145848-0392-17861125-p1m).

Phylogenetic molecular analyses were conducted on the aligned cox1 sequences and were inferred by both Maximum-Likelihood (ML) method using MEGA11 (Tamura et al., 2021) and by Bayesian Inference (BI) using Mr. Bayes program (v3.2.6, available at http://www.phylogeny.fr/one_task.cgi?task_type=mrbayes; Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001; Dereeper et al., 2008, 2010). Regarding ML, to determine the nucleotide substitution model that gave the best fit to our data set, the MEGA11 software which held the JModel test analysis was employed, with model selection based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Models with the lowest BIC scores (Bayesian Information Criterion) are considered to describe the substitution pattern the best. Non-uniformity of evolutionary rates among sites may be modeled by using a discrete Gamma distribution (+G) with 5 rate categories and by assuming that a certain fraction of sites are evolutionarily invariable (+I). For estimating ML values, a tree topology was automatically computed. The analysis involved 53 nucleotide sequences. Codon positions included were 1st+2nd+3rd + Noncoding. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 200 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7.

The number of substitution types was fixed to 2. For Bayesian Inference (BI) the 4 by 4 model was used for substitution, while rate variation across sites was fixed to “gamma”. Four Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run for 10,000 generations, sampling every 10 generations, with the first 250 sampled trees discarded as “burn-in”. Finally, a 50 % majority rule consensus tree was constructed.

2.5. Statistical analysis

A 1-way analysis of variance was performed (factor: intermediate host species) using the R software and plyr package (R Core Team, 2024) in R Studio (RStudio Team, 2024) for comparison measurements between metacestodes of C. terraplen and Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen (data used in discussion section, e.g., p value).

3. Results

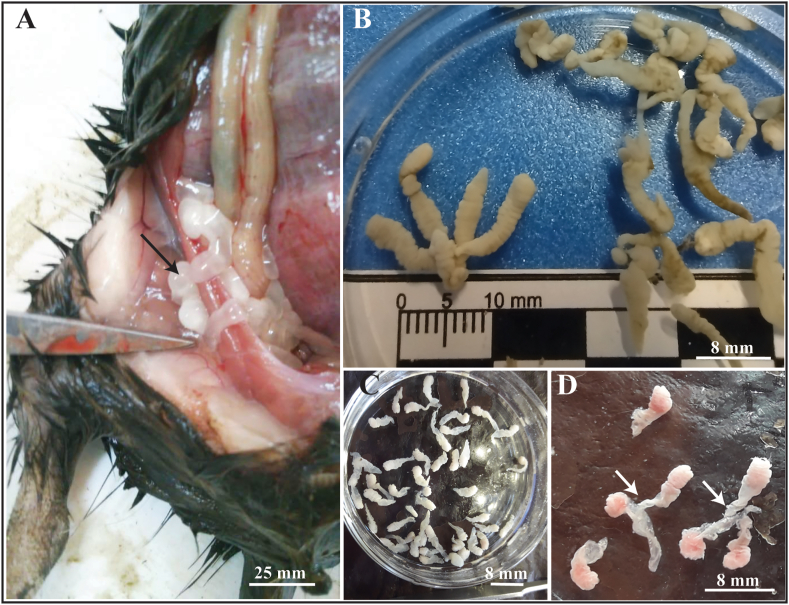

Metacestodes of Taenia talicei were found in two individuals of C. terraplen (Fig. 1 A, C-D) from Corcovado and in the one identified as Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen from Laguna El Cronómetro (LEC) (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

(A–D). Metacestodes of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) (Cestoda: Taeniidae) invading peritoneal cavity in Ctenomys spp. (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae) from Chubut province, Argentina. (A) Fimbriocerci (arrow) in peritoneal cavity of C. terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi and Martin from Corcovado. (B) Multiple (polycephalic) fimbriocerci from C. aff. C. terraplen from Laguna El Cronómetro. (C) Monocephalic fimbriocerci from C. terraplen. (D) Polycephalic fimbriocerci (arrows) from C. terraplen. Arrows indicate the common bladder.

Cyclophyllidea van Beneden in Braun (1900)

Taeniidae Ludwig, 1886

Taenia Linnaeus, 1758

Taenia talicei Dollfus (1960)

3.1. Description of metacestodes

Based on 27 monocephalic and 7 polycephalic metacestodes (fimbriocerci) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Table 2). Metacestodes elongated, white, with invaginated scoleces (Fig. 1).

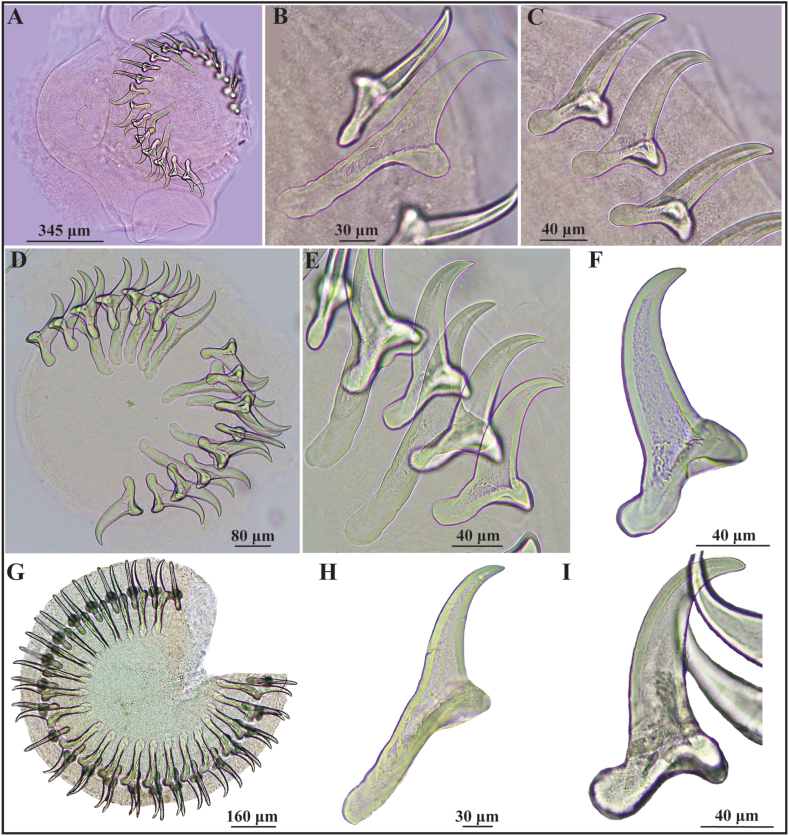

Fig. 2.

(A–I). Rostellar hooks of metacestodes of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) (Cestoda: Taeniidae) in Ctenomys spp. (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae) from Chubut province, Argentina. (A–C). Scolex and rostellar hooks of fimbriocerci from C. terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi and Martin from Corcovado (individual LIEB-M-1735). (A) Scolex showing rostellum with rostellar hooks, and suckers. (B) Large hook. (C) Small hooks. (D–F). Rostellar hooks of fimbriocerci from C. terraplen (individual LIEB-M-1736). (D) Rostellum showing alternating hooks, large and small. (E) Large and small hooks. (F) Small hook. Hoyer's mounting fluid. (G–I). Rostellum and rostellar hooks of fimbriocerci from Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen from Laguna El Cronómetro (individual LIEB-M-1809). (G) Rostellum showing the two crowns of alternating hooks, large and small. (H) Large hook. (I) Small hook. Berlese's mounting fluid.

Table 2.

Comparison of morphometrics of metacestodes (single fimbriocerci) of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) from intermediate hosts reported from South America (in μm). Abbreviations: n, number of measurements; SD, standard deviation.

| Hosts | Ctenomys terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi & Martin | Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen | Ctenomys torquatus Lichtenstein | Ctenomys peruanus Sanborn & Pearson | Ctenomys australis (Rusconi) | Ctenomys talarum Thomas | Phyllotis xanthopygus (Waterhouse) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Present study | Present study | Dollfus (1960) | Voge (1954) | Rossin et al. (2010) | Rossin et al. (2010) | Gomez-Puerta (2017) |

| Locality/Country | Corcovado, Chubut province, Argentina | Laguna El Cronómetro, Chubut province, Argentina | Montevideo, Uruguay | Puno Department, Peru | Buenos Aires province, Argentina | Buenos Aires province, Argentina | Marangani District, Cusco, Peru |

| Characters | N | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LARGE HOOKS | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Total length (TL) | 24 | 268 ± 15 | 230–280 | 33 | 263 ± 13 | 230–280 | 2 | – | 245–247 | – | – | 190–220 | 50 | 236 ± 2 | 230–243 | 50 | 243 ± 3 | 240–248 | 14 | 228 ± 1 | 218–237 |

| Total width (TW) | 24 | 77 ± 15 | 40–94 | 27 | 70 ± 10 | 50–81 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 77 ± 0.6 | 72–82 |

| Basal length (BL) | 24 | 159 ± 17 | 120–180 | 27 | 158 ± 12 | 130–170 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 148 ± 0.9 | 141–153 |

| Apical length (AL) | 24 | 128 ± 7 | 110–140 | 26 | 125 ± 5 | 120–130 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 109 ± 0.5 | 106–112 |

| Guard length (GL) | 24 | 26 ± 8 | 13–44 | 27 | 23 ± 5 | 13–31 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 22 ± 0.3 | 21–25 |

| Guard width (GW) | 24 | 34 ± 6 | 25–50 | 27 | 34 ± 5 | 25–43 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 30 ± 0.3 | 29–32 |

| Blade curvature (BC) | 24 | 22 ± 25 | 6–140 | 26 | 17 ± 4 | 9–25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 17 ± 0.3 | 15–18 |

| Handle width (HW) | 24 | 29 ± 4 | 18–37 | 27 | 30 ± 6 | 19–38 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 19 ± 0.5 | 15–22 |

| Nº large hooks | 3 | 25 ± 1 | 24–26 | 4 | 25 ± 2 | 23–27 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SMALL HOOKS | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Total length (TL) | 49 | 152 ± 20 | 88–180 | 32 | 159 ± 11 | 130–180 | 2 | – | 154–160 | – | – | 120–140 | 50 | 154 ± 4 | 150–160 | 50 | 161 ± 3 | 158–168 | 14 | 147 ± 0.6 | 144–155 |

| Total width (TW) | 45 | 79 ± 13 | 50–130 | 25 | 72 ± 13 | 49–88 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 80 ± 0.8 | 75–84 |

| Basal length (BL) | 45 | 81 ± 20 | 9–100 | 25 | 77 ± 11 | 56–90 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 77 ± 0.9 | 70–81 |

| Apical length (AL) | 45 | 120 ± 8 | 100–130 | 25 | 113 ± 6 | 100–130 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 104 ± 0.4 | 101–105 |

| Guard length (GL) | 45 | 21 ± 5 | 13–31 | 25 | 20 ± 4 | 12–29 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 22 ± 0.4 | 21–25 |

| Blade curvature (BC) | 45 | 16 ± 4 | 7–24 | 24 | 16 ± 6 | 6–25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 14 | 20 ± 0.2 | 20–22 |

| Nº small hooks | 3 | 25 ± 1 | 24–26 | 4 | 24 ± 2 | 22–26 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nº total hooks | 2 | 48 | 48 | 4 | 49 ± 3 | 45–53 | 2 | – | 48–52 | – | – | 40–44 | 10 | 46 ± 3 | 40–50 | 10 | 46 ± 6 | 40–52 | 48 | – | 44–50 |

| Body length (mm) | 11 | 7 ± 2 | 2–10 | – | – | – | 2 | 6 | – | – | – | 9–15 | 10 | 20 ± 8 | 9–35 | 10 | 11 ± 5 | 5–20 | – | 9.6 | 6–12 |

| Maximum body width (mm) | 12 | 7 ± 0.4 | 3–4 | – | – | – | – | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Suckers diameter | 4 | 345 ± 105 | 280–500 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 291 ± 22 | 260–320 | 10 | 258 ± 40 | 200–320 | – | 315 | 304–324 |

| Rostellum diameter | 8 | 583 ± 118 | 470–800 | 4 | 613 ± 134 | 420–730 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 | 424 ± 47 | 370–500 | 10 | 407 ± 12 | 390–420 | – | 629 | 612–647 |

| Scolex length (+invaginated neck) (mm) | 8 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 0.9–3.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.09 | 1.08–1.12 |

| Scolex width (+invaginated neck) (mm) | 7 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1–1.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Monocephalic metacestodes from Corcovado (Fig. 2A-F): body 8 ± 2.4 (2.4–11.9) mm (n = 18) long by 3.1 ± 0.6 (2.4–4) mm (n = 18) maximum wide. Suckers diameter 345 ± 105 (280–500) (n = 4); rostellum diameter 583 ± 118 (470–800) (n = 8); invaginated scolex 2.6 ± 0.8 (0.9–3.7) (n = 8) mm long by 1.5 ± 0.4 (1–1.9) (n = 7) mm wide.

Monocephalic metacestodes from LEC (Fig. 2G-I): 16 ± 5.8 (11.5–29.4) mm (n = 8) long by 3.3 ± 0.5 (2.5–3.9) mm (n = 8) maximum wide. Suckers not visible, rostellum diameter 613 ± 134 (420–730) (n = 4).

Polycephalic metacestodes from LEC: composed of two to five fimbriocerci arising from a common bladder (Fig. 1B). Whole forms 19.4 ± 6.3 (11–27.8) mm (n = 7) long by 7.9 ± 4.5 (3.3–14.9) mm (n = 7) maximum wide. Individual fimbriocerci of polycephalic metacestodes: 10.7 ± 1.5 (8.7–12.6) mm (n = 18) long by 3 ± 0.2 (2.6–3.2) mm (n = 18) maximum wide. Common bladder 1.7 ± 0.3 (1.4–2.4) mm (n = 8) long by 1.8 ± 0.5 (1.1–2.8) mm (n = 8) maximum wide. Scolex 4.1 mm (n = 1) long by 1.4 mm (n = 1) maximum wide.

Rostellar hooks fully formed, arranged in two rows, with three typical parts: handle, blade and guard. Number and dimensions of large and small hooks (according to Haukisalmi et al., 2011) of metacestodes from these and from other intermediate hosts (data from literature) are given in Table 2.

3.2. Description of adult scolex and proglottids

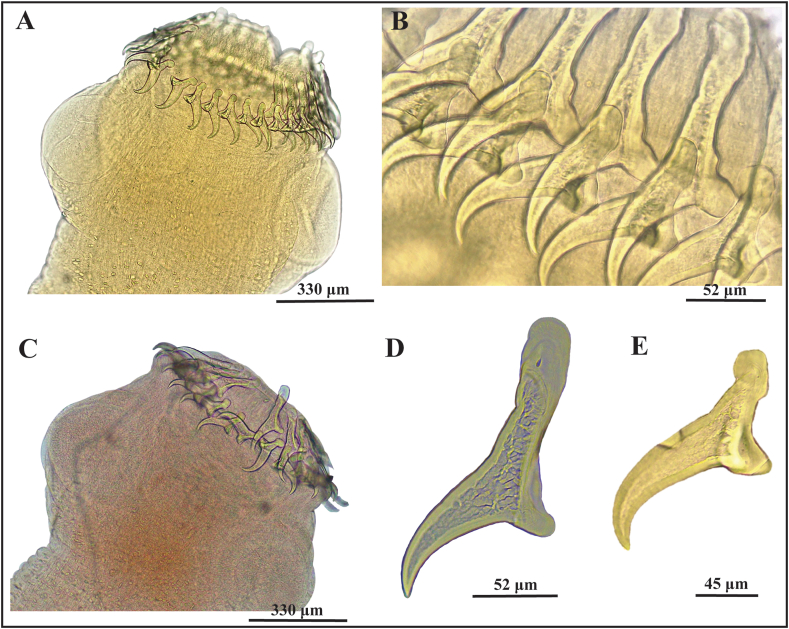

Strobilate adults (Fig. 3): white in vivo. Strobila >47 mm (n = 1) total length. Scolex 870 ± 40 (820–900) (n = 4) long by 900 ± 180 (750–1110) (n = 4) wide, bearing four rounded muscular suckers 330 ± 64 (270–390) in diameter (Fig. 3 A, C). Rostellum armed, 583 ± 125 (430–690) in diameter, with two rows of hooks. Number and dimensions of large and small hooks (Fig. 3 B, D, E) (according to Haukisalmi et al., 2011) of strobilate adults from this and from other known definitive hosts (data from literature) are given in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

(A–D). Rostellar hooks of strobilate adults of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) (Cestoda: Taeniidae) in Lycalopex culpaeus (Molina) (Carnivora: Canidae) from Chubut province, Argentina. (A–B). From Laguna La Zeta. (A) Scolex, showing rostellum with hooks, and suckers. (B) Alternating large and small hooks. (C) Small hooks. (D–F) From Los Alerces National Park. (D) Scolex, showing rostellum with hooks, and suckers. (E) Large hook. (F) Small hooks.

Table 3.

Comparison of morphometrics of adult scoleces of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) from definitive hosts reported from South America (in μm). Abbreviations: n, number of measurements; SD, standard deviation.

| Hosts | Lycalopex culpaeus (Molina) (natural host) | Canis lupus familiaris Linnaeus, 1758 (experimental host) | L. culpaeus (natural host) | Lycalopex gymnocercus Fischer (natural host) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Present study | Rossin et al. (2010) | Ayala-Aguilar et al. (2013) | Scioscia (2015) |

| Locality/Country | Chubut province, Argentina | Buenos Aires province, Argentina | La Paz, Bolivia | Buenos Aires province, Argentina |

| Characters | N | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range | n | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LARGE HOOKS | ||||||||||||

| Total length (TL) | 5 | 266 ± 5 | 260–270 | – | 238 | 232–242 | – | 210 | 200–220 | 7 | 225 | – |

| Total width (TW) | 5 | 99 ± 20 | 75–120 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 63 | – |

| Basal length (BL) | 5 | 172 ± 11 | 160–180 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Apical length (AL) | 5 | 132 ± 8 | 120–140 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Guard length (GL) | 5 | 26 ± 4 | 20–31 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Guard width (GW) | 5 | 35 ± 7 | 25–44 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Blade curvature (BC) | 5 | 17 ± 3 | 13–19 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Handle width (HW) | 5 | 35 ± 4 | 30–38 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nº large hooks | 1 | 24 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| SMALL HOOKS | – | – | – | |||||||||

| Total length (TL) | 12 | 155 ± 11 | 130–170 | – | 168 | 150–187 | 130 | 130–150 | 7 | 148 | – | |

| Total width (TW) | 12 | 88 ± 14 | 60–110 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | 48 | – |

| Basal length (BL) | 12 | 91 ± 5 | 81–96 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Apical length (AL) | 12 | 119 ± 10 | 100–130 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Guard length (GL) | 12 | 22 ± 7 | 10–38 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Blade curvature (BC) | 12 | 17 ± 2 | 12–19 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nº small hooks | 1 | 24 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Nº total hooks | 1 | 48 | – | 46 | – | 44–50 | – | 40 | 36–42 | – | – | 35–40 |

| Body length (mm) | 1 | >470 | – | – | 268 | 273–391 | – | – | 5–20 | – | – | – |

| Maximum body width (mm) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Suckers diameter | 4 | 330 ± 64 | 270–390 | – | 273 | 220–330 | 330 | 320–350 | – | – | – | |

| Rostellum diameter | 4 | 583 ± 125 | 430–690 | – | 168 | 150–187 | – | – | – | |||

| Scolex length (mm) | 4 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 0.82–0.9 | – | 0.63 | 0.45–0.86 | 0.58 | 0.57–0.59 | – | – | – | |

| Scolex width (mm) | 4 | 0.90 ± 0.18 | 0.75–1.11 | – | 0.1 | 0.71–1.2 | 1.03 | 0.82–1.11 | – | – | – | |

Partial length of strobilate adults fragment 25 ± 9 (13–34) (n = 4) mm by 1280 ± 200 (940-1520) (n = 6) maximum wide. Proglottids acraspedote. Immature proglottids 430 ± 20 (500–900) (n = 15) long by 600 ± 90 (520–700) (n = 15) wide; mature proglottids 600 ± 50 (540–630) (n = 15) long by 890 ± 210 (690-1110) (n = 15) wide and gravid proglottids 830 ± 120 (630-1030) (n = 35) long by 1120 ± 250 (700-1380) (n = 35) wide. Distance from the lateral margin to the osmoregulatory canals in immature proglottids 110 (n = 1), not observed in mature proglottids; in gravid proglottids 100 ± 40 (80–130) (n = 10). Distance between osmoregulatory canals in immature proglottids 380 ± 100 (250–460) (n = 20), not observed in mature proglottids; in gravid proglottids 830 ± 160 (720–950) (n = 14).

The few strobili available were stained with conventional cestode staining methods, but without good results. Differentiation was not attained, precluding the observation of the genitalia or other internal organs and obtaining additional meristic data.

3.2.1. Taxonomic summary

Intermediate hosts: Tuco-tuco del bosque, Ctenomys terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi and Martin; Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae).

Definitive host: Andean fox, Lycalopex culpaeus (Molina) (Carnivora: Canidae).

Site of infection: in intermediate hosts, peritoneal cavity; in definitive host, small intestine.

Localities: Corcovado (43.54° S, 71.46° W) (metacestodes in C. terraplen); Laguna El Cronómetro (43.24° S, 71.09° W) (metacestodes in Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen); field near Laguna La Zeta (42.81 °S, 71.38 °W) and Los Alerces National Park (42.97 °S,71.58 °W) (strobilate adults in L. culpaeus), Chubut province, Argentina.

Prevalence (P) and intensity of infection: In C. terraplen: P = 18.2 % (two out of eleven). The two specimens were infected with 34 and 45 monocephalic metacestodes, and two and three polycephalic metacestodes, respectively. Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen: the only infected specimen harboured 19 metacestodes (12 mono- and seven polycephalic metacestodes). In Lycalopex culpaeus: P = 40 % (two out of five Andean foxes infected with two and four strobilate adults, respectively).

Material deposited (vouchers): From C. terraplen and Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen: mono- and polycephalic metacestodes, LIEB-Pa-97. From L. culpaeus: strobilate adults, LIEB-Pa-96.

Host specimens deposited: LIEB-M-1735, LIEB-M-1736 (C. terraplen), LIEB-M-1809 (Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen). LIEB-M-1806, LIEB-M-1792 (L. culpaeus).

GenBank access numbers: PP738877, PP738957, PP738958 (cox1, fimbriocerci from C. terraplen, Corcovado); PP738968 (cox1, strobilate adult from L. culpaeus, Los Alerces National Park).

Comments.

The number, size and shape of the large and small hooks observed in our specimens were largely coincident with the data published by Dollfus (1960) and Rossin et al. (2004, 2010) on metacestodes of T. talicei from Ctenomys spp. Proliferating metacestodes reported by Voge (1954) from Peruvian rodents (including a species of Ctenomys), could be conspecific with T. talicei according to Rossin et al. (2010). All of these records fall within the range of measurements of the specimens studied herein (Table 2). Additionally, all the previous works indicated the peritoneal cavity as the site of infection in the intermediate hosts. Although Dollfus and Rossin et al. also found metacestodes in the liver, we did not find metacestodes in other organs.

Monocephalic and polycephalic metacestodes were found in the two localities. However, larger, more developed metacestodes and a greater proportion of polycephalic metacestodes were found in Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen from Laguna El Cronómetro (LEC). Moreover, we found significant differences (p = 4.2e-05∗∗∗) in the body size between the metacestodes from Corcovado and those from LEC. Such differences in the body size of the whole metacestodes may be attributed to the age of the infection. Indeed, the tuco-tucos from Corcovado presented smaller and probably not fully developed metacestodes, with few polycephalic metacestodes and little budding per vesicle, unlike the infection of the tuco-tuco from LEC where the metacestodes were much larger, and polycephalic metacestodes were more abundant, there was higher number of budding per vesicle and each fimbriocercus was much larger (twice as large) than the forms from Corcovado (Fig. 1B, D). This confirms what was observed by Voge (1954), who attributed differences in size among metacestodes from different hosts, as well as the relative size of the common vesicle and the proportion of multiple and simple fimbriocerci, to the age of the infection. According to Voge (1954), in recent infections simple cysticerci predominate whereas in older infections additional metacestodes proliferate from the bladder and multiple metacestodes increase in number. In these presumably fully grown metacestodes, the common bladder was usually much smaller or entirely absent, being replaced in some forms by a hardened tissue. Similarly, Rossin et al. (2010) registered monocephalic fimbriocerci in C. australis, which were twice as large as those found in C. talarum in the same study area and, in turn, all were larger than the measurements reported by Dollfus (1960). Rossin et al. (2010) also found cysticerci co-occurring with fimbriocerci and polycephalic metacestodes, what was interpreted as polymorphism in larval development of this species. Therefore, metacestodes of T. talicei seem to have a relatively wide range of hosts and morphometric variability, the latter not depending on the host species but on the age of the infection and the degree of development in which the metacestodes are found. This means that we should rely mainly on the shape, size and number of hooks rather than the measurements of the whole metacestode to help determine this taeniid species.

In regard to the strobilate adult, our identification was based mainly on the morphology and measurements of the rostellum, suckers and hooks, using the description by Rossin et al. (2010). Indeed, shape and measurements of hooks from strobilate adults were very similar to those recorded by Rossin et al. (2010) (from the experimental infection of a domestic dog in Argentina), but also to those found by Ayala-Aguilar et al. (2013) (as Taenia sp.) from a naturally infected Andean fox in Bolivia (Table 3, Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 in Rossin et al., 2010, Fig. 1, Fig. 2 in Ayala-Aguilar et al., 2013).

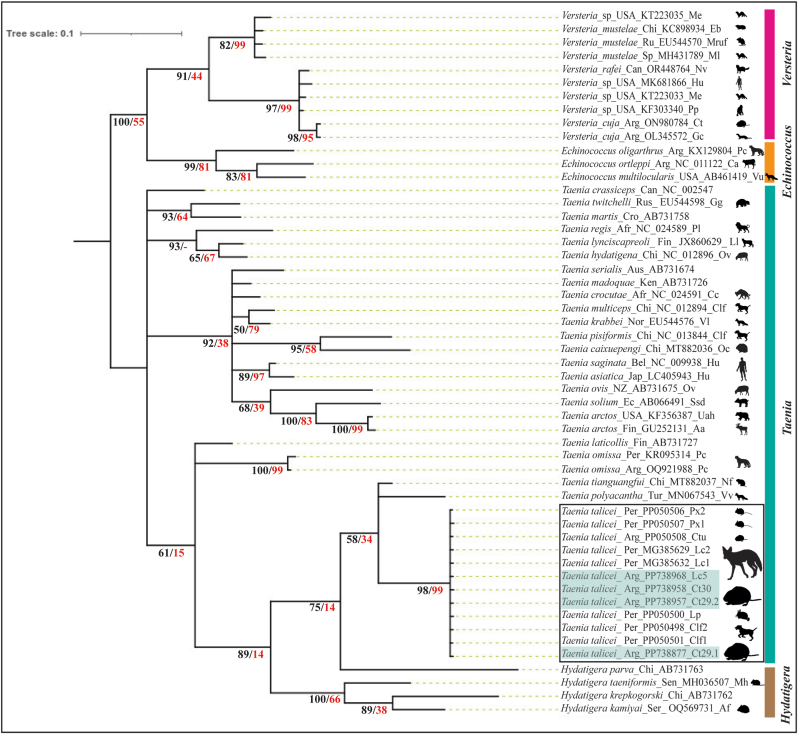

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships of Taenia taliceiDollfus (1960) (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from the tuco-tuco Ctenomys terraplen Brook, González, Tomasco, Verzi and Martin (Arg_Ct29-30) and the Andean fox Lycalopex culpaeus (Molina) (Arg_Lc) from Chubut province, Argentina, with other Taeniidae genera, as inferred from mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene sequences analyzed using Maximum-Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods. Nodal support is indicated under the internodes as BI (posterior probabilities, black)/ML (bootstrap value, red); values < 0.70 (BI) and <50 (ML) are indicated by a dash. The tree is drawn to ML scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site (below the branches). The subclade of T. talicei is indicated in the black rectangle and the sequences of the present study are highlighted in light blue; its hosts are indicated to be larger than the rest.

3.3. Molecular and phylogenetic analysis

Based on morphological evidence we performed molecular analyses of fimbriocerci from C. terraplen and a strobilate adult from L. culpaeus. PCR amplification of cox1, mtDNA from fimbriocerci in the peritoneal cavity of C. terraplen produced six products of 371, 378, 282, 382, 380 and 373 bp, respectively. Amplification from the intestinal worm in the Andean fox produced two products, both of 375 bp. All these sequences showed 100 % similarity.

Regarding the phylogenetic tree, as outgroup we selected a species within the genus Versteria instead of a more distantly related species. This decision was based on prior observations indicating that the use of highly divergent outgroups resulted in excessive divergence, causing the collapse of the group of interest and hindering the resolution of phylogenetic relationships among the species. This approach preserved the phylogenetic structure within the group and allowed for a more robust interpretation of the results. Results indicated that the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model (HKY) (G + I) was the most appropriate. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown under the branches. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach, and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. A discrete gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (5 categories (+G, parameter = 0.15)). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site (under the branches). This analysis involved 53 nucleotide sequences and there was a total of 200 positions in the final dataset.

The estimates of evolutionary divergence between sequences were conducted in MEGA11 (Tamura et al., 2021). The rate variation among sites was modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 0.5). All ambiguous positions were removed for each sequence pair (pairwise deletion option). Pairwise nucleotide sequence divergences were calculated using the Tamura-Nei model with a gamma setting of 0.5. Then, we calculated the mean pairwise divergences for both intra- and interspecific variation. For the BI, to determine the evolution model that gave the best fit to our dataset the program jModeltest 2.1.1 (Darriba et al., 2012) was employed, with model selection based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). Results indicated that AC = CG, AT = GT and an unequal base frequency with an estimate of gamma distributed among-site rate variation (HKY + G + I) was the most appropriate.

Cox1 tree topologies resulting from the ML and BI analysis were identical, with BI producing higher branch support (Fig. 4). The genus Taenia formed a paraphyletic group. The isolates obtained in this study appeared in the phylogenetic tree closely related to a group of species from Peru and Argentina, composed of Taenia sp. from L. culpaeus (MG385632.1, 99.73 % similarity, Peru); T. talicei from L. culpaeus (MG385629.2, 99.73 % similarity, Peru) and from C. l. familiaris (PP050501.1, PP050498.1, 100 % similarity, Peru); T. talicei from Ctenomys tuconax (Argentina), Phyllotis xanthopygus (Peru), and Lagidium peruanum (Peru), with genetic distances of 0.00 (Table 4). The clade composed of T. talicei formed the closely related group and had the lowest genetic distance (0. 09) (Table 4), with Taenia tiangungfui Fan et al. (2014). The highest genetic distance was observed with Taenia pisiformis (Bloch, 1780) Gmelin, 1790 (0.26) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Intra- and interspecific pairwise divergence within genus Taenia in the complete sequences of mitochondrial cox1 gene. The new data are in bold.

| Taenia species | Geographical distribution | Intraspecific pairwise distance | Interspecific pairwise distance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraspecific | |||

| Taenia_talicei_Arg_PP738877_Ct29.1 | Patagonia Argentina | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Arg_PP738957_Ct29.2 | Patagonia Argentina | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Arg_PP738958_Ct30 | Patagonia Argentina | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Arg_PP738968_Lc5 | Patagonia Argentina | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_MG385632_Lc1 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_MG385629_Lc2 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Arg_PP050508_Ctu | North-western Argentina | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_PP050507_Px1 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_PP050506_Px2 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_PP050501_Clf1 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_PP050498_Clf2 | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Taenia_talicei_Per_PP050500_Lp | Peru | 0.00 | |

| Interspecific | |||

|

T. talicei vs. Taenia_tianguangfui_Chi_MT882037_Nf |

China | 0.09 | |

| Taenia_polyacantha_Tur_MN067543_Vv | Türkiye | 0.11 | |

| Taenia_hydatigena_Chi_NC_012896_Ov | China | 0.14 | |

| Taenia_crassiceps_Can_NC_002547 | Canada | 0.16 | |

| Taenia_laticollis_Fin_AB731727 | Finland | 0.16 | |

| Taenia_regis_Afr_NC_024589_Pl | Africa | 0.16 | |

| Taenia_twitchelli_Ru_EU544598_Gg | Russia | 0.16 | |

| Taenia_lynciscapreoli_Fin_JX860629_Ll | Finland | 0.16 | |

| Versteria_mustelae_Chi_EU544570_Mruf | China | 0.16 | |

| Taenia_crocutae_Afr_NC_024591_Cc | Africa | 0.17 | |

| Taenia_serialis_Aus_AB731674 | Australia | 0.17 | |

| Versteria_mustelae_Ru_EU544570_Mruf | Russia | 0.17 | |

| Versteria_sp_USA_KF303340_Pp | USA | 0.17 | |

| Versteria_rafei_Can_OR448764_Nv | Canada | 0.17 | |

| Taenia_martis_Cro_AB731758 | Croatia | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_mustelae_Sp_MH431789_Ml | Spain | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_sp_USA_KT223035_Me | USA | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_sp_USA_KT223033_Me | USA | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_sp_USA_MK681866_Hu | USA | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_cuja_Arg_OL345572_Gc | Argentina | 0.18 | |

| Versteria_cuja_Arg_ON980784_Ct | Argentina | 0.18 | |

| Taenia_madoquae_Ken_AB731726 | Kenya | 0.19 | |

| Taenia_multiceps_Chi_NC_012894_Clf | China | 0.19 | |

| Taenia_saginata_Bel_NC_009938_Hu | Belgium | 0.19 | |

| Hydatigera_parva_Sen_MH036507_Mh | Senegal | 0.19 | |

| Taenia_asiatica_Jap_LC405943_Hu | Japan | 0.20 | |

| Taenia_krabbei_Nor_JX507239_Vl | Norway | 0.20 | |

| Echinococcus_ortleppi_Arg_NC_011122_Ca | Argentina | 0.20 | |

| Taenia_arctos_Fin_KF356387_Uah | Finland | 0.21 | |

| Taenia_caixuepengi_Chi_MT882036_Oc | China | 0.21 | |

| Taenia_omissa_Arg_OQ921988_Pc | Argentina | 0.21 | |

| Taenia_omissa_Per_KR095314_Pc | Peru | 0.21 | |

| Taenia_ovis_NZ_AB731675_Ov | New Zeland | 0.21 | |

| Hydatigera_krepkogorski_Chi_AB731762 | China | 0.21 | |

| Hydatigera_taeniformis_Bel_AB745096 | Belgium | 0.21 | |

| Echinococcus_multilocularis_USA_AB461419_Vu | USA | 0.21 | |

| Taenia_arctos_Fin_GU252131_Aa | Finland | 0.22 | |

| Hydatigera_kamiyai_Ser_OQ569731_Af | Serbia | 0.22 | |

| Echinococcus_oligarthrus_Arg_KX129804_Pc | Argentina | 0.22 | |

| Taenia_solium_Ecu_AB066491_Ssd | Ecuador | 0.24 | |

| Taenia_pisiformis_Chi_NC_013844_Clf | China | 0.26 | |

4. Discussion

Our analyses confirmed not only that the metacestodes from Ctenomys spp. and the Andean fox are the same (100 % similarity between cox1 sequences), but they also belong to the species T. talicei, with genetic distances of 0.00 between the sequences deposited in GenBank and ours (Table 4). We can thus confirm the presence of T. talicei in northwestern Patagonia, Argentina, with a life-cycle involving the subterranean rodents of the genus Ctenomys (i.e., C. terraplen and Ctenomys aff. C. terraplen) as intermediate hosts, and the Andean fox L. culpaeus as definitive host.

Taenia talicei shares with T. polyacantha Leuckart, 1856 the type of larva (fimbriocercus), rodents as intermediate hosts and canids as definitive hosts. However, its distribution is in the northern hemisphere (Abuladze, 1964; Verster, 1969; Rausch and Fay, 1988). On the other hand, the very low genetic distance with T. tianguangfui is also remarkable, this species was described from a metacestode (cysticercus) in a rodent, Neodon fuscus (Buchner), but the strobilate adult or its definitive host are still unknown. In addition, the distribution is very distant (China) (Fan et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2021). It can also be observed in the phylogeny that the T. talicei group together with T. tianguangfui, T. polyacantha and the Hydatigera species have a recent appearance with respect to evolutionary time.

Taenia talicei is the first described species of Taenia that can be considered endemic from South America (Rossin et al., 2010) and, up to now, records of the species are far more frequent from its intermediate hosts than from definitive ones. The former are mainly small rodents, preferably of the genus Ctenomys that inhabit Argentina, Bolivia and Uruguay (C. australis, C. talarum, C. tuconax, C. terraplen, C. aff. C. terraplen, C. opimus, C. torquatus), whereas in Peru this taeniid was found not only in tuco-tucos (C. peruanus) but also in other rodents, including larger ones such as the northern viscacha Lagidium peruanum (available data in GenBank, see Table 1). The metacestodes found in Phyllotis xanthopygus from Peru by Gomez-Puerta (2017) could reasonably be attributed to this species, based on morphology, hosts, site of infection, and geographic location. Therefore, we can not rule out that other rodent species are involved in the cycle in this study area (i.e., Patagonia). However, other species of cricetid rodents (belonging to genera Abrothrix, Geoxus, Irenomys) from the area where we collected T. talicei have been examined, but with negative results.

Until now, there was no published information on the natural definitive hosts of T. talicei. In Argentina, Rossin et al. (2004) obtained the strobilate adult through the experimental infection of a domestic dog with metacestodes from naturally infected C. talarum and C. australis. Rossin et al. (2010) speculated that the natural definitive hosts could be wild carnivores inhabiting the area where metacestodes were collected (south-eastern Buenos Aires province), such as the Geoffroy's cat Leopardus geoffroyi d'Orbigny and Gervais, or the Pampas fox Lycalopex gymnocercus Fischer, both known to prey on C. talarum and C. australis. Some years later Scioscia (2015, PhD Thesis) found strobilate adult cestodes that were identified as Taenia sp. in Pampas foxes from the southern departments of Villarino, Patagones and Tandil (Buenos Aires province). A prevalence of 25 % (n = 80) and mean intensity of 4.9 was found. Scioscia (2015) inferred that the species in question could be T. talicei according to the number, size and morphology of the rostellar hooks, but in the absence of mature proglottids in good condition the identity of the species could not be confirmed. The measurements of rostellar hooks provided by Scioscia (2015) are quite close to the mean values of the species (Table 3) and, looking at the photographs presented in her work, it is possible to infer that it is indeed T. talicei.

Thus, the few available evidence indicates that the natural definitive hosts of this taeniid species in South America would be canids: the Andean fox L. culpaeus, at least in localities from the Andean region and the South American Transition zone (sensu Morrone et al., 2022). Uncertainties or possible erroneous identifications of Taenia in both L. culpaeus and L. gymnocercus (Ayala-Aguilar et al., 2013; Oyarzún-Ruiz et al., 2020; Gomez-Perta et al., unpublished data), and the Pampas fox L. gymnocercus in the Chacoan subregion and Andean region (Scioscia, 2015) should be mentioned. Regarding the Andean fox, it is distributed from Colombia through the Andes Mountains to the southern tip of South America, where it reaches the Atlantic coast towards the east (Chébez et al., 2014). It is an opportunistic predator whose diet fluctuates throughout the year according to the availability of resources, including small mammals -mainly rodents, among them Ctenomys-, lagomorphs, ungulates, birds, reptiles, arthropods and carrion (Pia et al., 2003; Zapata et al., 2005, 2007; Walker et al., 2007; Chébez et al., 2014). The heterogeneous distribution of the different rodent species that serve as prey for the Andean fox throughout its distribution might explain the presence of the parasite in such a number of intermediate hosts in Argentina, Bolivia and Peru.

Among more than 30 species of endoparasites reported from the Andean fox throughout its distribution (Fugassa, 2020), the lack of previous reports of T. talicei is rather striking. There are, however, reports of strobilate adults of other members of Taenia that were attributed to non-endemic species such as T. hydatigena Pallas, 1766 and T. multiceps Leske, 1780 (Moro, 1998; Oyarzún-Ruiz et al., 2020) or remained without specific identification (Taenia sp.) (Ayala-Aguilar et al., 2013). The finding of Moro (1998) was not accompanied by illustrations that make inferences about the identity of the species involved. Instead, the findings of Ayala-Aguilar et al. (2013) and Oyarzún-Ruiz et al. (2020) included photographs and, based on the morphology, host, and geographic localization it is likely that such findings correspond actually to T. talicei. Unfortunately, such reports did not include genetic data that we could use in our analyses.

Thus, the few available evidence indicates that the natural definitive hosts of this taeniid species in South America would be canids. It is confirmed for the Andean fox L. culpaeus, at least in localities from the Andean region and the South American Transition zone (sensu Morrone et al., 2022) (this work, Gomez-Puerta et al., unpublished data). And we should also mention the uncertain, unconfirmed records or possible erroneous identifications (discussed above) in both L. culpaeus (Ayala-Aguilar et al., 2013; Oyarzún-Ruiz et al., 2020), and L. gymnocercus in the Andean region (Oyarzún-Ruiz et al., 2020) and Chacoan subregion (Scioscia, 2015). There are no evidence, so far, that T. talicei would be present in felids.

Regarding whether T. talicei is a potentially zoonotic species, Rossin et al. (2010) pointed out that since the species can develop in domestic dogs, and Ctenomys species can be found in urban or semi-urban environments, the possibility exists of establishing synanthropic cycles that include the dog as definitive host, making it relevant as a route of human exposure. However, to date there is no confirmation that the species affects humans.

This study is the first report of the natural life cycle of an endemic species of Taenia from South America. It integrates molecular and ecological aspects of the interaction between a fox, a subterranean rodent and a parasitic tapeworm. Future studies could show this tapeworm to be more widespread geographically, probably infecting more species, both intermediate and definitive.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Estefanía Bagnato: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Juan José Lauthier: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis. Federico Brook: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology, Data curation. Gabriel Mario Martin: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Methodology. María Celina Digiani: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación, Argentina (E.B., PICT Nº, 2019-00569), (M.C.D., PICT Nº, 2019–03535).

Declarations of interest

none.

Acknowledgements

The authors specially thank Turcato family, Ricardo (estate owner), M. Dromaz, I. Powell and family, J. Cignetti and G. Bauer for help in the field. Darío Balcazar, Marina Ibáñez Shimabukuro and Micaela Ricuzzi (Centro de Estudios Parasitológicos y de Vectores-CEPAVE-CCT-CONICET La Plata, Buenos Aires) for molecular analyses (extraction, purification and amplification of ADN). The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers who helped to improve the paper. To the Dirección Fauna y Flora Silvestre from Ministerio de Agricultura, Ganadería, Industria y Comercio del Chubut for collecting permissions. GMM thanks E. Watkins and M. Simeon for economic support.

Contributor Information

Estefanía Bagnato, Email: ebagnato@comahue-conicet.gob.ar.

Juan José Lauthier, Email: juanjoselauthier@gmail.com.

Federico Brook, Email: brook.federico@gmail.com.

Gabriel Mario Martin, Email: gmartin_ar@yahoo.com.

María Celina Digiani, Email: mdigiani@fcnym.unlp.edu.ar.

References

- Abuladze K.I. vol. IV. Akademii Nauk USSR; Moscow, Russia: 1964. (Principles of Cestodology). [Google Scholar]

- Arrabal J.P., Arce L.F., Macchiaroli N., Kamenetzky L. Ecological and molecular associations between Neotropical wild felids and Taenia (Cestoda: Taeniidae) in the Atlantic forest: a new report for Taenia omissa. Parasitol. Res. 2023;122:2999–3012. doi: 10.1007/s00436-023-07989-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrabal J.P., Avila H.G., Rivero M.R., Camicia F., Salas M.M., Costa S.A., Nocera C.G., Rosenzvit M.C., Kamenetzky L. Echinococcus oligarthrus in the subtropical region of Argentina: first integration of morphological and molecular analyses determines two distinct populations. Vet. Parasitol. 2017;240:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala-Aguilar G., Nallar R., Alandia-Robles E., Alandia-Robles R., Mollericona J.L., Ayala-Crespo G. Parásitos intestinales del zorro andino (Lycalopex culpaeus, Canidae) en el Valle Acero Marka de los Yungas (La Paz, Bolivia) Ecol. en Boliv. 2013;48:104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato E., Acuña F., Brook F., Martin G.M., Barbeito C.G., Digiani M.C. Natural life cycle of Versteria cuja (Taeniidae) in Argentina and histopathology of metacestodiasis in intermediate hosts. Parasitology. 2023;150:488–497. doi: 10.1017/S0031182023000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagnato E., Gilardoni C., Martin G.M., Digiani M.C. A new species of Versteria (Cestoda: Taeniidae) parasitizing Galictis cuja (Carnivora: Mustelidae) from Patagonia, Argentina: morphological and molecular characterization. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2022;19:68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., Blair D., McManus D.P. Genetic variants within the genus Echinococcus identified by mitochondrial DNA sequencing. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992;54:165–174. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90109-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., McManus D.P. Molecular variation in Echinococcus. Acta Trop. 1993;53:291–305. doi: 10.1016/0001-706X(93)90035-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J., McManus D.P. Rapid discrimination of Echinococcus species and strains using a polymerase chain reaction-based RFLP method. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1993;57:231–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook F., González B., Tomasco I.H., Verzi D.H., Martin G.M. Within the forest: a new species of Ctenomys (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae) from northwestern Patagonia. J. Mammal. 2024;20:1–18. doi: 10.1093/jmammal/gyae101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bush A.O., Lafferty K.D., Lotz J.M., Shostak A.W. Parasitology Meets Ecology on Its Own Terms: Margolis et al. Revisited. J. Parasitol. 1997;83:575. doi: 10.2307/3284227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Lejeune M., Verocai G.G., Duignan P.J. First report of Taenia arctos (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from grizzly (Ursus arctos horribilis) and black bears (Ursus americanus) in North America. Parasitol. Int. 2014;63:389–391. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano S., Bâ K., Diouf N.D., Léger E., Verocai G.G., Webster J.P. Rodents of Senegal and their role as intermediate hosts of Hydatigera spp. (Cestoda: Taeniidae) Parasitology. 2019;146:299–304. doi: 10.1017/S0031182018001427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chébez J.C., Pardiñas U., Teta P. Mamíferos Terrestres. Patagonia sur de Argentina y Chile. Vázquez Mazzini Editores. 2014 Buenos Aires. [Google Scholar]

- Chervy L. The terminology of larval cestodes or metacestodes. Syst. Parasitol. 2002;52:1–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1015086301717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G.L., Doallo R., Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. 772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A., Audic S., Claverie J.-M., Blanc G. BLAST-EXPLORER helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., Dufayard J.-F., Guindon S., Lefort V., Lescot M., Claverie J.-M., Gascuel O. Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:W465–W469. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollfus R. Cystique dún nouveau Taenia, de la cavit peritoneale dun Ctenomys (Rodentia) del lUruguay. Arch. la Soc. Biol. Montevideo. 1960;25:47–51. [Google Scholar]

- Erol U., Sarimehmetoglu O., Utuk A.E. Intestinal system helminths of red foxes and molecular characterization Taeniid cestodes. Parasitol. Res. 2021;120:2847–2854. doi: 10.1007/s00436-021-07227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y.L., Lou Z.Z., Li L., Yan H.B., Han X.M., Li J.Q., Liu C.N., Yang Y.R., McManus D.P., Jia W.Z. Preliminary study on taxonomic status of cysticerci from Microtus fuscus in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau of China. Chinese Vet. Sci./Zhongguo Shouyi Kexue. 2014;44:789–793. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier-Chambrillon C., Torres J., Miquel J., André A., Michaux J., Lemberger K., Carrera G.G., Fournier P. Severe parasitism by Versteria mustelae (Gmelin, 1790) in the critically endangered European mink Mustela lutreola (Linnaeus, 1761) in Spain. Parasitol. Res. 2018;117:3347–3350. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-6043-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugassa M.H. Updated checklist of helminths found in terrestrial mammals of Argentine Patagonia. J. Helminthol. 2020;94:1–56. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X20000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzorig S., Gardner S.L. In: Concepts in Animal Parasitology. Gardner S.L., Gardner S.A., editors. Zea Books; Lincoln, Nebraska, United States: 2024. Eucestoda; pp. 251–261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner S.L., Botero-Cañola S., Aliaga- Rossel E., Dursahinhan A.T., Salazar-Bravo J. Conservation status and natural history of Ctenomys, tuco-tucos in Bolivia. Therya. 2021;12:15–36. doi: 10.12933/therya-21-1035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg T.L., Gendron-Fitzpatrick A., Deering K.M., Wallace R.S., Clyde V.L., Lauck M., Rosen G.E., Bennett A.J., Greiner E.C., O’Connor D.H. Fatal metacestode infection in orangutan caused by unknown Versteria species. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:109–113. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.131191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Puerta L.A. Hallazgo de fimbriocercos de Taenia sp. (Cestoda: Taeniidae) en el ratón orejón de ancas amarillas (Phyllotis xanthopygus) Rev. Peru. Biol. 2017;24:319–322. doi: 10.15381/rpb.v24i3.13909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Puerta L.A., Alarcon V., Pacheco J., Franco F., Lopez-Urbina M.T., Gonzalez A.E. Molecular and morphological evidence of Taenia omissa in pumas (Puma concolor) in the Peruvian Highlands. Brazilian J. Vet. Parasitol. Jaboticabal. 2016;25:368–373. doi: 10.1590/S1984-29612016046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukisalmi V., Lavikainen A., Laaksonen S., Meri S. Taenia arctos n. sp. (Cestoda: Cyclophyllidea: Taeniidae) from its definitive (brown bear Ursus arctos Linnaeus) and intermediate (moose/elk Alces spp.) hosts. Syst. Parasitol. 2011;80:217–230. doi: 10.1007/s11230-011-9324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haukisalmi V., Konyaev S., Lavikainen A., Isomursu M., Nakao M. Description and life-cycle of Taenia lynciscapreoli sp. n. (Cestoda, Cyclophyllidea) ZooKeys. 2016;584:1–23. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.584.8171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoberg E.P., Jones A., Rausch R.L., Eom K.S., Gardner S.L. A phylogenetic hypothesis for species of the genus Taenia (Eucestoda: Taeniidae) J. Parasitol. 2000;86:89–98. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0089:APHFSO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoberg E.P. Phylogeny of Taenia: species definitions and origins of human parasites. Parasitol. Int. 2006;55:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H.-K., Kim K.-H., Eom K.S. Complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Taenia saginata: comparison with T. solium and T. asiatica. Parasitol. Int. 2007;56:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W.-Z., Yan H.-B., Guo A.-J., Zhu X.-Q., Wang Y.-C., Shi W.-G., Chen H.-T., Zhan F., Zhang S.-H., Fu B.-Q., Littlewood D.T.J., Cai X.-P. Complete mitochondrial genomes of Taenia multiceps, T. hydatigena and T. pisiformis: additional molecular markers for a tapeworm genus of human and animal health significance. BMC Genom. 2010;11:447. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen A., Haukisalmi V., Lehtinen M.J., Henttonen H. A phylogeny of members of the family Taeniidae based on the mitochondrial cox1 and nad1 gene data. Parasitology. 2008;135:1457–1467. doi: 10.1017/S003118200800499X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen A., Haukisalmi V., Lehtinen M.J., Laaksonen S., Holmström S., Isomursu M., Oksanen A., Meri S. Mitochondrial DNA data reveal cryptic species within Taenia krabbei. Parasitol. Int. 2010;59:290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavikainen A., Iwaki T., Haukisalmi V., Konyaev S.V., Casiraghi M., Dokuchaev N.E., Galimberti A., Halajian A., Henttonen H., Ichikawa-Seki M., Itagaki T., Krivopalov A.V., Meri S., Morand S., Näreaho A., Olsson G.E., Ribas A., Terefe Y., Nakao M. Reappraisal of Hydatigera taeniaeformis (Batsch, 1786) (Cestoda: Taeniidae) sensu lato with description of Hydatigera kamiyai n. sp. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016;46:361–374. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le T.H., Blair D., Agatsuma T., Humair P.F., Campbell N.J.H., Iwagami M., Littlewood D.T.J., Peacock B., Johnston D.A., Bartley J., Rollinson D., Herniou E.A., Zarlenga D.S., McManus D.P. Phylogenies inferred from mitochondrial gene orders - a cautionary tale from the parasitic flatworms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:1123–1125. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.M., Wallace R.S., Clyde V.L., Gendron-Fitzpatrick A., Sibley S.D., Stuchin M., Lauck M., O'Connor D.H., Nakao M., Lavikainen A., Hoberg E.P., Goldberg T.L. Definitive hosts of Versteria tapeworms (Cestoda : Taeniidae) causing Fatal infection in North America. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016;22:707–710. doi: 10.3201/eid2204.151446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman B., Leal S.M., Procop G.W., O'Connell E., Shaik J., Nash T.E., Nutman T.B., Jones S., Braunthal S., Shah S.N., Cruise M.W., Mukhopadhyay S., Banzon J. Disseminated metacestode Versteria species infection in Woman, Pennsylvania, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:1429–1431. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.190223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loos-Frank B. An up-date of Verster's (1969) 'Taxonomic revision of the genus Taenia Linnaeus' (Cestoda) in table format. Syst. Parasitol. 2000;45:155–184. doi: 10.1023/A:1006219625792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro P.L. Intestinal parasites of the grey fox (Pseudalopex culpaeus) in the central Peruvian Andes. J. Helminthol. 1998;72:87–89. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X00001048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrone J.J., Escalante T., Rodríguez-Tapia G., Carmona A., Arana M., Mercado-Gómez J.D. Biogeographic regionalization of the Neotropical region: new map and shapefile. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2022;94:1–5. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202220211167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M., Lavikainen A., Iwaki T., Haukisalmi V., Konyaev S., Oku Y., Okamoto M., Ito A. Molecular phylogeny of the genus Taenia (Cestoda: Taeniidae): Proposals for the resurrection of Hydatigera Lamarck, 1816 and the creation of a new genus Versteria. Int. J. Parasitol. 2013;43:427–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M., McManus D.P., Schantz P.M., Craig P.S., Ito A. A molecular phylogeny of the genus Echinococcus inferred from complete mitochondrial genomes. Parasitology. 2007;134:713–722. doi: 10.1017/S0031182006001934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M., Okamoto M., Sako Y., Yamasaki H., Nakaya K., Ito A. A phylogenetic hypothesis for the distribution of two genotypes of the pig tapeworm Taenia solium worldwide. Parasitology. 2002;124:657–662. doi: 10.1017/S0031182002001725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao M., Xiao N., Okamoto M., Yanagida T., Sako Y., Ito A. Geographic pattern of genetic variation in the fox tapeworm Echinococcus multilocularis. Parasitol. Int. 2009;58:384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyarzún-Ruiz P., Di Cataldo S., Cevidanes A., Millán J., González-Acuña D. Endoparasitic fauna of two South American foxes in Chile: Lycalopex culpaeus and Lycalopex griseus. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária. 2020;29:1–15. doi: 10.1590/s1984-29612020055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pia M.V., López M.S., Novaro A.J. Effects of livestock on the feeding ecology of endemic culpeo foxes (Pseudalopex culpaeus smithersi) in central Argentina. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2003;76:313–321. doi: 10.4067/S0716-078X2003000200015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2024. R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rausch R.L., Fay F.H. Postoncospheral development and cycle of Taenia polyacantha Leuckart, 1856 (Cestoda: Taeniidae) First part. Ann. Parasitol. Hum. comparée. 1988;63:263–277. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1988634263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin A., Malizia A.I., Denegri G.M. The role of the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia: Octodontidae) in the life cycle of Taenia taeniaeformis (Cestoda: Taeniidae) in urban environments. Vet. Parasitol. 2004;122:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossin M.A., Timi J.T., Hoberg E.P. An endemic Taenia from South America: validation of T. talicei Dollfus, 1960 (Cestoda: Taeniidae) with characterization of metacestodes and adults. Zootaxa. 2010;2636:49. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.2636.1.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team . RStudio, Inc.; Boston, MA: 2024. RStudio: Integrated Development for R.http://www.rstudio.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Scioscia N.P. Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata; 2015. Parásitos del zorro gris, Lycalopex gymnocercus de la provincia de Buenos Aires. (PhD Thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Shanebeck K.M., Bennett J., Green S.J., Lagrue C., Presswell B. A new species of Versteria (Cestoda: Taeniidae) parasitizing Neogale vison and Lontra canadensis (Carnivora: Mustelidae) from Western Canada. J. Helminthol. 2024;98:e4. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X23000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikes R.S., Gannon W.L., Mammalogists A.C., of U.C., of the A.S. Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research. J. Mammal. 2011;92:235–253. doi: 10.1644/10-MAMM-F-355.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]