Abstract

Urologic patients with anatomic abnormalities can be particularly susceptible to urinary tract infections (UTI). UTI with urease-producing bacteria can promote struvite urinary calculi and pose unique treatment problems. There is potential for rapid stone growth and bacterial eradication can be difficult secondary to urothelial or stone colonization. Antibiotic resistance among urease-producing organisms further complicates treatment. In this report, we describe the use of intravesical vancomycin in the treatment of a patient with struvite bladder calculi secondary to urease-producing Corynebacterium urealyticum cystitis, resistant to enteral antibiotics. This highlights the potential of intravesical antibiotics for the treatment of UTI.

Keywords: Urinary tract infection, Urease, Bladder calculi, Antibiotics, Exstrophy

1. Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTI) in pediatric patients with complex urologic conditions can be a frustrating challenge for pediatric urologists, with significant clinical and quality of life implications. Current treatment strategies include management of bowel and bladder dysfunction, surgical correction of anatomic or functional abnormalities, and oral or intravenous antibiotics. UTI from urease-producing bacteria can promote urinary calculi formation by altering urine chemistry. Urease hydrolyses urea to carbon dioxide and ammonia, which is further hydrolyzed to form ammonium and bicarbonate. The resulting alkalinized urine leads to struvite (ammonium magnesium phosphate) crystallization if the urine pH is > 7.2, or carbonate apatite if the pH is 6.8–7.2.1 However, many patients with urease-driven stone formation develop mixed urinary calculi of struvite, apatite, and calcium oxalate.1 Intrinsic stone inhibitors, such as citrate, may also be metabolized by bacteria, reducing their inhibitory effects. While Proteus species are the most common source of struvite stones, a variety of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria can produce urease, including Staphylococcus, Pseudomonas, Providencia, Klebsiella, Providencia, and Morgenalla species.2 Corynebacterium urealyticum is a gram-positive, urease-producing bacilli that remains an uncommon source of UTI, but one that readily leads to struvite stone formation, and potentially encrusted pyelitis and encrusted cystitis.3 Risk factors for C. urealyticum UTI include immunosuppression, urologic manipulation, recurrent UTI, and broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure.4

Intravesical antibiotics (IVA), delivered through bladder catheterization, have been shown to safely prevent recurrent UTIs in select patient populations.5 Indeed, daily gentamicin bladder irrigation has been shown to reduce recurrent UTIs in adult and pediatric patients with neurogenic bladder who perform CIC.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 While IVA use in recurrent UTI is promising, the use of IVA in treating acute bacterial cystitis, and in UTI associated with urease-producing organisms, remains poorly studied. Herein, we describe the use of intravesical vancomycin in the successful treatment of a patient with struvite bladder calculi and UTI secondary to urease-producing Corynebacterium urealyticum which was resistant to enteral antibiotics.

2. Case presentation

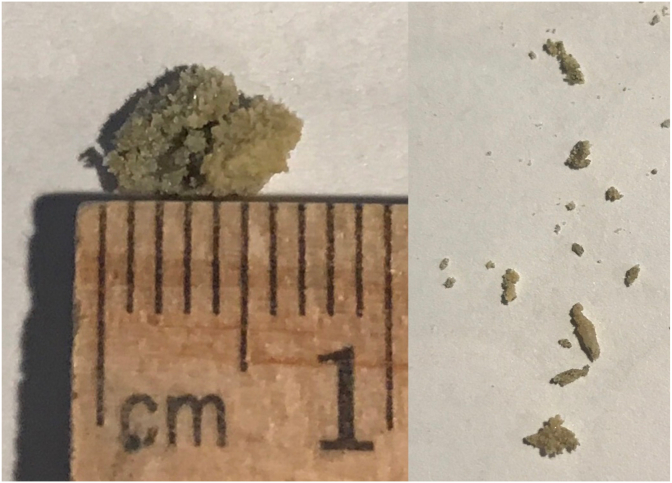

A 14-year-old male with a history of classic bladder exstrophy presented with a one-month history of worsening constipation, dysuria, intermittent gross hematuria, foul smelling urine, and passage of small stones with gritty stone material in the urine (Fig. 1). His history was significant for primary exstrophy closure as an infant, epispadias repair, and modified Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck reconstruction. He had a history of constipation, normal voiding, and small volume urinary incontinence requiring the use of pads. His previous post-void-residuals were low (10-15 cc). His risk factors for urinary tract infections included a history of bladder exstrophy, vesicoureteral reflux, chronic constipation, and poor fluid intake. He had previous been on both nitrofurantoin and cephalexin antibiotic prophylaxis, which had both been discontinued. Prior renal function studies were normal (Cr 0.3). Voided urine culture at presentation revealed >40,000 CFU/ml Corynebacterium urealyticum resistant to erythromycin, gentamicin, and penicillin, and sensitive to vancomycin. Stone analysis revealed mixed struvite and calcium apatite stone composition. His initial management included 24-h urine studies, increased fluid intake, polyethylene glycol laxative, with plans for inpatient admission to treat the multidrug resistant UTI.

Fig. 1.

Struvite bladder stones from C. urealyticum UTI.

Two consecutive 24-h urine studies revealed abnormalities consistent with a urease-producing UTI, with an alkaline urine and a mean pH of 8.9 (normal 5.8–6.2), and a highly elevated mean ammonium of 166.5 mmol/day (normal 15–60 mmol/day) (Table 1). Urinary citrate was reduced, with a mean of 260 mg/day (normal >450 mg/day). Urine volume was on the low end of normal, with a mean of 700ml (normal 0.5–4L/day).

Table 1.

24-hour urine values before and after C. urealyticum UTI IVA treatment.

| Pre-Treatment | C. urealyticum UTI | Post-Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume (L/d) | 0.62 | 0.68 | 1.68 |

| pH | 6.5 | 8.9 | 6.4 |

| Ammonium (mmol/d) | 15 | 167 | 21 |

| Calcium (mg/d) | 49 | 15 | 18 |

| Oxalate (mg/d) | 16 | 45 | 34 |

| Citrate (mg/d) | 214 | 260 | 274 |

| Magnesium (mg/d) | 56 | 4 | 54 |

| SS Calcium Oxalate | 5.5 | 1.9 | 1.1 |

| SS Calcium Phosphate | 1.16 | 0.26 | 0.18 |

| SS Uric Acid | 0.26 | 0.0 | 0.12 |

| Uric Acid (g/d) | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.26 |

SS, supersaturation. UTI values represent mean of two 24-h urine collections.

The patient was subsequently admitted and underwent renal bladder ultrasound, cystoscopy, catheter placement, intravesical antibiotic treatment, and bowel clean out. On day 1, cystoscopy revealed a normal bladder with debris. Urine culture collected with cystoscopy revealed >80,000 CFU/ml C. urealyticum. Ultrasound revealed normal appearing kidneys and bladder, and no evidence of kidney stones. A foley catheter was placed for IVA with both gentamicin and vancomycin. Instillations were performed by instilling 30ml of antibiotic in saline and clamping the catheter for 30 minutes. He received 30ml of gentamicin (48mg per 100ml saline) intravesically twice daily on days 1–3. On day 3, C. urealyticum urine culture sensitivities revealed resistance to erythromycin, gentamicin, and penicillin, and sensitivity to vancomycin. Based on sensitivities, gentamicin IVA was discontinued. He received 30ml of vancomycin (416mg per 100ml saline) intravesically every 6 hours on days 1–7 for a total of 26 vancomycin doses. Serum gentamicin and vancomycin levels were not measured.6,10,11 Senna and polyethylene glycol was administered for bowel cleanout until obtaining watery stools. On day 10 his foley catheter was removed. Repeat urine culture from his catheter at that time revealed 30,000 CFU/ml coagulase negative Staphyloccus, which was asymptomatic and not treated.

After three years of follow-up, the patient remained stone free, without recurrence of stones or C. urealyticum UTI. Two months after IVA treatment, he had one subsequent Staphylococcus aureus UTI, diagnosed and treated at an outside hospital. Repeat urine cultures at 6 and 9 months after IVA revealed no evidence of UTI. Post-treatment 24-h urine studies revealed normalization of urine pH and ammonium (Table 1).

3. Discussion

Stone formation is relatively common among bladder exstrophy epispadias complex (BEEC) patients, with up to 15 % requiring a stone procedure after developing urinary calculi in childhood.12 In prior exstrophy series, 90 % of stones developed in the bladder and were mainly mixed composition of calcium apatite, calcium oxalate, and struvite. More than half of bladder stones were due to urease-producing UTI, and occurred at relatively similar rates among native bladders and patients with bladder augmentation.12

Given the propensity for urease-producing organisms to drive struvite stone formation, careful antibiotic selection is an important part of struvite stone management. To complicate antibiotic treatment, trends in bacterial resistance have consistently shown the spread of antibiotic resistant bacterial strains worldwide.13,14 Multidrug resistance (MDR) has been reported in C. urealyticum, with common resistance to β-lactams, aminoglycosides, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones, while many C. urealyticum isolates remain susceptible to vancomycin.3 The patient presented here with MDR C. urealyticum demonstrates the difficulty in MDR UTI treatment, which may require parenteral therapy due to the limited number of antibiotic treatment options.

The authors consider IVA treatment in cases of complicated bacterial cystitis, either acute or recurrent. Special consideration is given to cases with MDR organisms who do not have viable oral treatment options, and in patients that already perform CIC. In cases of complicated pyelonephritis, intravenous antibiotics are preferred. IVA with gentamicin and vancomycin have been demonstrated to be safe, with little trans-urothelial absorption.6,10,11 As such, gentamicin and vancomycin serum levels were not monitored in our patient. Absorption of IVA, including gentamicin, may be different in patients with intestinal bladder augmentation.6 Although our patient was treated as an inpatient for monitoring, outpatient treatment with IVA may become a valid treatment option for patients with MDR UTI, or struvite bladder stones from urease-producing acute bacterial cystitis. This is especially attractive in patients who already perform CIC. In addition, direct intravesical antimicrobial instillation may allow for drug delivery at higher urine drug concentrations than those achieved via parenteral or enteral administration.7

4. Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of vancomycin bladder irrigation for UTI treatment of C. urealyticum. This adds to the evidence that IVA are an effective treatment option for acute cystitis in select populations. Further studies are needed to explore this drug delivery method in the management of UTI.

Funding sources

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jason E. Michaud: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization. Christian C. Morrill: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Ahmad Haffar: Investigation, Data curation. Heather N. Di Carlo: Resources, Project administration, Data curation. John P. Gearhart: Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts.

Acknowledgements

We thank The Kwok Family Foundation for their support of bladder exstrophy research.

References

- 1.Flannigan R., Choy W.H., Chew B., Lange D. Renal struvite stones—pathogenesis, microbiology, and management strategies. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11(6):333–341. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bichler K.H., Eipper E., Naber K., Braun V., Zimmermann R., Lahme S. Urinary infection stones. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19(6):488–498. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soriano F., Tauch A. Microbiological and clinical features of Corynebacterium urealyticum: urinary tract stones and genomics as the Rosetta Stone. Clin Microbiol Infect Off Publ Eur Soc Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):632–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappuccino L., Bottino P., Torricella A., Pontremoli R. Nephrolithiasis by Corynebacterium urealyticum infection: literature review and case report. J Nephrol. 2014;27(2):117–125. doi: 10.1007/s40620-014-0064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pietropaolo A., Jones P., Moors M., Birch B., Somani B.K. Use and effectiveness of antimicrobial intravesical treatment for prophylaxis and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs): a systematic review. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19(10):78. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0834-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Defoor W., Ferguson D., Mashni S., et al. Safety of gentamicin bladder irrigations in complex urological cases. J Urol. 2006;175(5):1861–1864. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marei M.M., Jackson R., Keene D.J.B. Intravesical gentamicin instillation for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infections in complex paediatric urology patients: evidence for safety and efficacy. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17(1):65.e1–65.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox L., He C., Bevins J., Clemens J.Q., Stoffel J.T., Cameron A.P. Gentamicin bladder instillations decrease symptomatic urinary tract infections in neurogenic bladder patients on intermittent catheterization. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(9):E350–E354. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.4434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huen K.H., Nik-Ahd F., Chen L., Lerman S., Singer J. Neomycin-polymyxin or gentamicin bladder instillations decrease symptomatic urinary tract infections in neurogenic bladder patients on clean intermittent catheterization. J Pediatr Urol. 2019;15(2):178.e1–178.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marei M.M., Jackson R., Keene D.J.B. Intravesical gentamicin instillation for the treatment and prevention of urinary tract infections in complex paediatric urology patients: evidence for safety and efficacy. J Pediatr Urol. 2021;17(1):65.e1–65.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hajjar R.R., Philpot C., Morley J.E. Continuous bladder irrigation with vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(7):886–887. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silver R.I., Gros D.A., Jeffs R.D., Gearhart J.P. Urolithiasis in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 1997;158(3 Pt 2):1322–1326. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Center for Disease, Dynamics Economics & Policy ResistanceMap: antibiotic resistance. 2020. https://resistancemap.cddep.org/AntibioticResistance.php

- 14.CDC . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2019. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States. CDC. [Google Scholar]