Abstract

Background

Substance‐specific mass media campaigns which address young people are widely used to prevent illicit drug use. They aim to reduce use and raise awareness of the problem.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in preventing or reducing the use of or intention to use illicit drugs amongst young people.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 1), including the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group's Specialised Register; MEDLINE through PubMed (from 1966 to 29 January 2013); EMBASE (from 1974 to 30 January 2013) and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I (from 1861 to 3 February 2013).

Selection criteria

Cluster‐randomised controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, interrupted time series and controlled before and after studies evaluating the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in influencing drug use, intention to use or the attitude of young people under the age of 26 towards illicit drugs.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures of The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

We included 23 studies involving 188,934 young people, conducted in the USA, Canada and Australia between 1991 and 2012. Twelve studies were randomised controlled trials (RCT), two were prospective cohort studies (PCS), one study was both a RCT and a PCS, six were interrupted time series and two were controlled before and after (CBA) studies. The RCTs had an overall low risk of bias, along with the ITS (apart from the dimension 'formal test of trend'), and the PCS had overall good quality, apart from the description of loss to follow‐up by exposure.

Self reported or biomarker‐assessed illicit drug use was measured with an array of published and unpublished scales making comparisons difficult. Pooled results of five RCTs (N = 5470) show no effect of media campaign intervention (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.02; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.15 to 0.12).

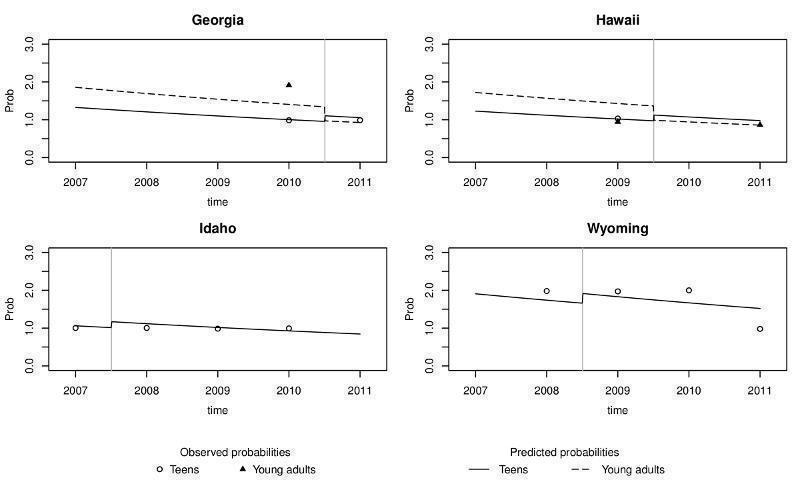

We also pooled five ITS studies (N = 26,405) focusing specifically on methamphetamine use. Out of four pooled estimates (two endpoints measured in two age groups), there was evidence of a reduction only in past‐year prevalence of methamphetamine use among 12 to 17 years old.

A further five studies (designs = one RCT with PCS, two PCS, two ITS, one CBA, N = 151,508), which could not be included in meta‐analyses, reported a drug use outcome with varied results including a clear iatrogenic effect in one case and reduction of use in another.

Authors' conclusions

Overall the available evidence does not allow conclusions about the effect of media campaigns on illicit drug use among young people. We conclude that further studies are needed.

Keywords: Humans, Illicit Drugs, Mass Media, Australia, Canada, Health Promotion, Health Promotion/methods, Prospective Studies, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Retrospective Studies, Substance‐Related Disorders, Substance‐Related Disorders/prevention & control, United States

Plain language summary

Do media campaigns prevent young people from using illicit drugs?

Media campaigns to prevent illicit drug use are a widespread intervention. We reviewed 23 studies of different designs involving 188,934 young people and conducted in the United States, Canada and Australia. The studies tested different interventions and used several questionnaires to interview the young people about the effects of having participated in the studies brought to them. As a result it was very difficult to reach conclusions and for this reason we are highlighting the need for further studies.

Background

Health promotion, mass media campaigns are initiatives typically undertaken by national authorities which use communication media to disseminate information about, for example, health or threats to it and to persuade people to adopt behavioural changes. Mass media campaigns are implemented via television and radio broadcasts, newspaper or magazine advertisements, billboards and road posters. They can also use colourful advertisements and brochures available for travellers on buses and the metro and, more recently, a broad range of available technology including the Internet, mobile phone short messages and email lists. Media campaigns can be of short or longer duration and sometimes they encompass several consequent rounds of delivery. They can be standalone interventions or be integrated into complex social marketing programmes.

Mass media campaigns for the prevention of illicit drug use are very common worldwide but only few campaigns have been formally evaluated (Wammes 2007). Furthermore, most of those evaluations (Rossi 2003) assessed only the process (in terms of understanding, retention and appeal of the messages) and the very few that assessed outcomes (in terms of behaviours of use) often found weak or counterproductive effects.

Description of the condition

Initiation of use of all substances typically occurs during the teens or early years of adulthood (ESPAD 2011; UNODC 2012). Since the neurological or psychological factors that may influence how and whether addiction develops are unknown, "even occasional drug use can inadvertently lead to addiction" (Leshner 1997; Leshner 1999). Indeed, research has found that drug use leading to dependence usually starts in adolescence (Camí 2003; McLelland 2000; Swendsen 2009).

Since the neurological and social mechanisms of dependence are similar for all addictive substances, a common view, therefore, is that prevention should focus on an age group (teenagers) rather than specific substances (Ashton 2003; Leshner 1997; Nestler 1997; Wise 1998).

Description of the intervention

The mass media (TV, Internet, radio, newspapers, billboards) have increasingly been used as a way of delivering preventive health messages. They have the potential to modify the knowledge or attitudes of a large proportion of the community (Redman 1990). They also have the potential to reach large populations of susceptible individuals and groups that may be difficult to access through more traditional approaches. In addition, in terms of the per capita cost of prevention messages, they are relatively inexpensive (Brinn 2010).

This review is limited to mass media campaigns that aim to prevent the uptake of illicit drug use (both in general or that of specific substances) or to reduce or stop the use of illicit drugs. It excludes mass media campaigns that aim to promote safer or less harmful use of drugs.

The following table summarises the main characteristics of most mass media campaign.

| Category | Objective | Target audience | Details |

| Information campaign | Warning | General or youth population | Information about the dangers and risks of a range of illicit substances |

| Empowerment | General population, especially parents | Information about how to contribute to drug prevention through your own behaviour | |

| Information about where and how to seek support, counselling and treatment regarding illicit drug use, especially for your children | |||

| Youth population | Information about where and how to seek support, counselling and treatment regarding illicit drug use | ||

| Support | General population | Information about existing prevention interventions or programmes in communities, in schools or for families in order to strengthen community involvement and support for them | |

| Social marketing campaign | Correct erroneous normative beliefs | General or youth population | Declared purpose is to correct erroneous normative beliefs about the extent and acceptance of drug use in peer populations ("you're not weird if you don't use because 80% of your peers don't either") |

| Setting or clarifying social and legal norms | General or youth population | Declared purpose is to deglamorise and demystify drug use and related behaviour (e.g. drug driving) and to explain the rationale of community norms and control measures | |

| Setting positive role models or social norms | General or youth population | Declared purpose is to promote non‐drug‐use‐related prototypes of lifestyles, behaviour and personality |

How the intervention might work

Most campaigns are based on a limited number of theoretical models, such as the health belief model (lack of knowledge about health harms may lead to drug use), the theory of planned behaviour (drug use is a rational decision due to attitude toward drugs, perceived social norms and perceived control over drugs) and the social norms theory (overrated perception of prevalence among peers may lead to drug use). In summary, the theories most frequently used as base for anti‐drugs mass media campaigns are:

Health belief model. This model (Glanz 2002) is based on the concept that the perceived susceptibility to and the severity of the disease and the perceived benefits of action to avoid disease are the key factors in motivating a positive health action. So, based on some elements of the model, the provision of factual information about the negative effects and dangers of drugs should deter use or prevent substance abuse by creating negative attitudes towards drug use.

Intervention based on this theory: information campaign

Theory of reasoned action/theory of planned behavior. The theory of reasoned action/theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen 1991) proposes that an individual's behavioural intentions have three constituent parts: the individual's attitude towards the behaviour, the social norms as perceived by the individual and the perceived control over the behaviour. Individuals may weight these differently in assessing their behavioural intentions. According to this model, drug use is a consequence of a rational decision (intention), which is based on the belief about drug use, the social norms towards drug use and the belief about control over the behaviour.

Intervention based on this theory: social marketing campaigns with the objective of setting or clarifying social and legal norms as well as information campaigns

Social norms theory. This theory (Perkins 1986) states that "our behaviour is influenced by incorrect perceptions of how other members of our social groups think and act" (Berkowitz 2004, p. 5). Campaigns based on this theory, which are also referred to as 'normative education', challenge the misconception that many adults and most adolescents use drugs. For example, students are provided with information on the prevalence ‐ from either national or local surveys ‐ of drug use among their peers so that they can compare their own estimates of drug use with the actual prevalence.

Related to this is the Super‐Peer Theory (Strasburger 2008). The Super‐Peer Theory postulates that media portrayal of drug use (or casual sex or violence) influences the susceptible teens.

Intervention based on this theory: social marketing campaigns that aim to correct erroneous normative beliefs

Social learning theory. The social learning theory (Bandura 1977) postulates that personality is an interaction between environment, behaviours and the psychological processes of an individual. Also referred to as observational learning, the theory of social learning places an emphasis on observing and modelling other people's behaviours, attitudes and emotional reaction.

Intervention based on this theory: social marketing campaigns setting positive role models or social norms

Why it is important to do this review

Bühler and Kröger (Bühler 2006) conclude their review of reviews with the recommendation to use media campaigns only as supporting measures and not as a single strategy alone, whereas Hawks 2002, in line with the review of reviews by the Health Development Agency (HDA) (McGrath 2006), concludes that "the use of the mass media on its own, particularly in the presence of other countervailing influences, has not been found to be an effective way of reducing different types of psychoactive substance use. It has however been found to raise information levels and to lend support to policy initiatives".

Despite concerns in reviews about poor effectiveness and possible harm of anti‐drug prevention activities (Faggiano 2008), media campaigns are still very popular worldwide and in European Union member states (EMCDDA 2009).

An assessment of both positive and negative (iatrogenic) effects is important for ethical reasons as well, because mass media campaigns ‐ unlike other social or health interventions ‐ are imposed on populations that have neither asked for nor explicitly consented to the intervention (Sumnall 2007). A systematic review of all the studies assessing media campaign interventions aimed at preventing illicit drug use in young people is therefore necessary in order to inform future strategies and to help design campaigns that avoid harm. Such a review will also contribute to the identification of further areas for research.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in preventing or reducing the use of or intention to use illicit drugs amongst young people.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Any study that evaluates the effectiveness of mass media campaigns in influencing drug use, intention to use or the attitude of young people towards illicit drugs.

Randomised controlled trials in which the unit of randomisation is an individual or a cluster (the school, community or geographical region)

Controlled trials without randomisation allocating schools, communities or geographical regions

Prospective and retrospective cohort studies

Interrupted time series

Controlled before and after studies

Types of participants

Young people under the age of 26.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

The following definition was adopted by a similar Cochrane review (Brinn 2010): "Mass media is defined here as channels of communication such as television, radio, newspapers, billboards, posters, leaflets or booklets intended to reach large numbers of people and which are not dependent on person to person contact". To be included in the review, a study needs to assess a mass media campaign explicitly aimed at influencing people's drug use, intention to use or attitude towards illicit drugs use.

Control intervention

1) No intervention; 2) other types of communication interventions such as school‐based drug abuse prevention programmes (Faggiano 2008); 3) community‐based prevention programmes; 4) lower exposure to intervention; 5) time before exposure to intervention.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Self reported or biomarker‐assessed illicit drug use

Secondary outcomes

Intentions not to use/to reduce use/to stop use

Attitudes towards illicit drug use

Knowledge about the effects of illicit drugs on health

Understanding of intended message and objectives

Perceptions (including perceptions of peer norms and perceptions about illicit drug use)

Adverse effects induced by the campaign (reactance, i.e. a reaction to contradict the prevailing norms of rules and positive descriptive norms, i.e. increased perception that drug use in peer population is common, normal or acceptable)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We obtained relevant trials from the following sources:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library 2013, Issue 1) which includes the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group's Specialised Register;

MEDLINE through PubMed (freely accessible at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) (from 1966 to 29 January 2013);

EMBASE (from 1974 to 30 January 2013);

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I (from 1861 to 3 February 2013).

We compiled detailed search strategies for each database searched. These were based on the search strategy developed for PubMed but revised appropriately for each database to take account of differences in controlled vocabulary and syntax rules.

The search strategy for:

CENTRAL is shown in Appendix 1;

PubMed is shown in Appendix 2;

EMBASE is shown in Appendix 3;

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses A&I was: (media campaigns OR mass media) AND illicit drug* AND preventi*.

We searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies on the following Internet sites:

Searching other resources

We also searched other sources to identify relevant studies. We assessed conference proceedings that were likely to contain relevant material and contacted the authors. We contacted investigators or experts in the field to seek information on unpublished or incomplete trials. We also reviewed EMCDDA National Focal Points Annual National Reports for any description of relevant studies conducted in Europe.

We used the first studies identified as fulfilling the inclusion criteria to inspect the MeSH terms and to integrate the search strategies. Moreover, we used the "related articles" function of PubMed in a "capture‐recapture method" to validate the inclusiveness of the search strategy.

We did not apply any language restriction.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (EA and MF) inspected the search hits by reading the titles and the abstracts. We obtained each potentially relevant study identified in the search in full text and at least two review authors assessed studies for inclusion independently. In case of doubts as to whether a study should have been included, this was resolved by discussion between the review authors. We collated and assessed multiple publications as one study.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (EA and AB) independently extracted data and input relevant information into Review Manager (Review Manager 2012) for meta‐analysis. Two review authors (MF and FF) assessed the theoretical background of the campaigns. We discussed and solved every step by consensus. We produced a narrative synthesis of the key findings along with a meta‐analysis of studies which used appropriate measures.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Four review authors (EA, AB, MF and FF) performed quality assessments independently. We discussed and solved any disagreement by consensus. We uploaded final assessments into Review Manager. In order to obtain more information on the criteria for reducing risk of bias, we contacted the authors of most of the studies.

To assess RCTs we followed the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane Reviews is a two‐part tool, addressing seven specific domains, namely sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias) blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) and other source of bias. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement relating to the risk of bias for that entry, in terms of low, high or unclear risk. The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) were addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study. Blinding of participants might not be applicable for this type of intervention, and we therefore considered blinding of personnel and outcome assessors (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias). We considered a study to have low risk of bias if the data were obtained with an anonymous questionnaire or administered by computer. We considered incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) for all outcomes.

For ITS studies we used the tools developed by the Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) Group (Appendix 4). For cohort studies we used the SIGN Quality Criteria described in Appendix 5.

Measures of treatment effect

We intended to analyse dichotomous outcomes (such as intention to use or actual use of illicit substances) by calculating the risk ratio (RR) or odds ratio (OR) for each trial and express the uncertainty in each result with their 95% confidence intervals. We only found continuous outcome measures which we analysed by calculating the standardised mean difference (SMD) with its corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

Unit of analysis issues

In the case of cluster‐randomised trials the unit of analysis is either the school or the town. We stated at protocol level that in this case we would have taken into account the criteria for assessing bias in cluster‐randomised trials as described in the Cochrane Handbook. We inflated each arm's standard deviation for two studies (Slater 2006; Newton 2010) by multiplying it by the study design effect, a coefficient which takes into account the average cluster size and the study intra‐class correlation.

Dealing with missing data

Where needed, we contacted the authors of the studies for integration of any possible missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The presence of heterogeneity between the trials was tested using the I2 statistic and the Chi2 test. A P value of the I2 statistic higher than 0.50 and a P value of the Chi2 test lower than 0.10 suggests that there is some evidence of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to use funnel plots (plots of the effect estimate from each study against the standard error) to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials, which could indicate possible publication bias. In fact we did not reach the minimum number of (10) studies included in the meta‐analysis which is suggested as sufficient for conducting a funnel plot (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We intended to carry out a meta‐analysis by combining RR/OR or the SMD where possible. We performed a meta‐analysis of the RCTs using a random‐effect model in order to take into consideration the heterogeneity among studies.

For the studies evaluating the Meth Project (Colorado Meth 2011; Georgia Meth 2011; Hawaii Meth 2011; Idaho Meth 2010; Wyoming Meth 2011) we performed a separate meta‐analysis. An interrupted time series (ITS) design was applied for estimating the differences in prevalence of methamphetamine use before and after the Meth Project intervention, adjusting for any underlying temporal trend. Statistical models were based on multilevel mixed effects logistic regression, with State as a random intercept modelling baseline log odds of methamphetamine use to vary randomly across states. The relatively few data points did not allow exploring of more complex models, e.g. the temporal trend could not be assumed to vary randomly across states. The fixed part of the final model assumes (i) a different baseline by age group, but similar among states; (ii) a linear temporal trend homogeneous across states; (iii) an effect of the intervention differing by age group but constant across time and occurring immediately after the intervention. The model may be written as logit(useij) = β0 + u0j + β1timei + β2intervi + β3agei + β4age×intervi + ϵij, with use as prevalence of methamphetamine use, time as a continuous variable, intervention and age as two‐level categorical variables and J indicating state. The exponentiated coefficient β2 is interpretable as the ratio between the odds of using methamphetamine after (numerator) and before (denominator) the intervention (Gilmour 2006).The model was fitted separately for past‐month and past‐year use of methamphetamine. Data points regarding lifetime use of methamphetamine were not analysed.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We intended to perform stratified meta‐analysis in order to assess the differential effect of the campaigns based on different theoretical approaches. However the impact of media campaigns may be mediated by the sub‐cultural environment and, in particular, by the attitude towards substance use in a given culture. Therefore, at protocol level it was anticipated that subsets of studies were to be analysed by characteristics of target participants (regional location, users versus non‐users etc.) whenever possible. Studies could also be compared by type of campaign, based on different theoretical approaches. We did not reach the number of studies sufficient to perform any type of sub‐set analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

To incorporate the assessment of risk of bias in the review process we first plotted the intervention effect estimates against the assessment of risk of bias. We subsequently inspected the results stratified for risk of bias and we did not find significant associations between measure of effect and risk of bias. We therefore decided to not include the 'Risk of bias' assessment in the meta‐analysis and to discuss it narratively in the results section. The items considered in the sensitivity analysis were the random sequence, blinding of personnel and outcome assessors, and selective reporting.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies and Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The study flow chart is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram. Please note that some studies include more than one article. This explains why there are 23 included studies out of 28 included articles.

Search sources

On 29 January 2013 we performed a PubMed (MEDLINE) search as described in Appendix 2, which identified 5877 records. On 30 January 2013 we searched CENTRAL which returned 566 results and EMBASE which gave 4945 records. On 3 February 2013 we also performed a ProQuest 'Dissertations & Theses A&I' search which returned 6638 records.

We also obtained additional records (N = 317) from one single paper (Hornik 2006) using PubMed's 'Similar articles' feature, and from papers extracted from 10 reviews (Battjes 1985; Berberian 1976; Hailey 2008; Kumpfer 2008; Romer 1994; Romer 1995; Schilling 1990; Stephenson 2003b; Wakefield 2010; Werb 2011), three reports (EMCDDA 2010; Know the Score 2007; NCI 2008) and three book chapters (Crano 2001; Flay 1983; Moskowitz 1983).

Screening

We independently screened records from each source search, i.e. no automatic removal of duplicates was used because of the risk of false‐positive duplicates. Therefore, we screened 18,343 titles and abstracts. Of them, we excluded 18,253 records (99.5%) as obviously irrelevant.

Full‐text analysis

We examined the full‐text articles of the remaining 90 records. Of them, 62 records were either excluded (N = 53) due to ineligibility of intervention type, participant age and reported outcome, or set in a pending status (N = 9) due to missing information. We contacted authors whenever possible.

Twenty‐eight records corresponded to 23 unique studies which were included in this review. A subset of 13 studies (eight RCTs and five ITS) could also be included in meta‐analyses, mostly thanks to personal communication with some authors who provided us with unpublished data and additional reports.

Included studies

Study design

Out of 23 unique studies, 12 were randomised controlled trials (RCT) (Czyzewska 2007; Fang 2010; Fishbein 2002; Kelly 1992; Lee 2010; Newton 2010; Palmgreen 1991; Polansky 1999; Schwinn 2010; Slater 2011; Yzer 2003; Zhao 2006), two were prospective cohort studies (PCS) (Hornik 2006; Scheier 2010), one study was both a RCT and a PCS (Slater 2011), six were ITS (Carpenter 2011; Colorado Meth 2011; Hawaii Meth 2011; Idaho Meth 2010; Palmgreen 2001; Wyoming Meth 2011) and two were before and after (CBA) studies (Georgia Meth 2011; Miller 2000).

Population

No study enrolled subjects younger than 10 years old. Twenty‐one studies included subjects older than 10 and younger than 20 years old. Two studies included subjects older than 20 years old and younger than this review's limit of 26 years old; one of them included only people older than 20 (Miller 2000) and one people aged 18 to 22 (Palmgreen 1991).

Three studies included only girls (Fang 2010; Kelly 1992; Schwinn 2010). The others did not specify any sex‐related selection criteria.

Two studies focused on specific ethnic or racial groups: one on Mexican‐American boys and girls (Polansky 1999) and one on Asian‐American girls (Fang 2010). The remaining studies did not use ethnicity, racial or socioeconomic characteristics to define the selection criteria.

Intervention

Mass media components

Eight studies evaluated standalone TV/radio commercials (Czyzewska 2007; Fishbein 2002; Kelly 1992; Palmgreen 1991; Palmgreen 2001; Polansky 1999; Yzer 2003; Zhao 2006) and four studies evaluated standalone Internet‐based interventions (Fang 2010; Lee 2010; Newton 2010; Schwinn 2010). Eleven studies evaluated multi‐component interventions, three regarding TV/radio and printed advertising (Miller 2000; Slater 2006; Slater 2011) and eight regarding TV/radio commercials, printed advertisements and Internet advertising (Carpenter 2011; Hornik 2006; Scheier 2010 and the five Meth Projects). No study evaluated interventions using standalone printed advertising.

Three studies added a school‐based drug prevention curriculum (Slater 2006; Slater 2011) or a combination of peer education, computer resources, campus policy and campus‐wide events (Miller 2000) to the mass media component(s).

Setting

Eleven studies were conducted in only one setting: eight studies in a school/college setting (Czyzewska 2007; Fishbein 2002; Kelly 1992; Lee 2010; Miller 2000; Newton 2010; Polansky 1999; Yzer 2003), two in a community setting (Fang 2010; Schwinn 2010) and one in a national/statewide setting (Palmgreen 2001).

Twelve studies were conducted in multiple settings: three in school and community settings (Palmgreen 1991; Slater 2006; Zhao 2006), eight in community and national settings (Carpenter 2011; Hornik 2006; Scheier 2010 and the five Meth Projects), while one (Slater 2011) reported evaluations of two similar but distinct interventions ‐ one implemented in a school and community setting and one aired to the whole nation.

Comparison group

Fourteen studies compared one or more mass media interventions with no intervention (Fang 2010; Fishbein 2002; Lee 2010; Miller 2000; Palmgreen 2001; Schwinn 2010; Slater 2006; Yzer 2003; Zhao 2006 and the five Meth projects). Four studies compared higher to lower exposure to a mass media intervention (Carpenter 2011; Hornik 2006; Scheier 2010; Slater 2011). Five studies compared anti‐drug advertisements with another intervention (Czyzewska 2007; Kelly 1992; Newton 2010; Palmgreen 1991; Polansky 1999). Two studies (Palmgreen 1991; Yzer 2003) had different intervention arms comparing either another intervention or no intervention. For details of control interventions see the table Characteristics of included studies.

The following table summarises the interventions evaluated and the exposure of the comparison groups, as well as the theories underlying the interventions.

| Studies | Explicit underpinning theory | Intervention | Comparison group | ||||

| Internet‐based intervention |

PSA (public service ‐ TV/radio) advertisements |

Printed advertisement | No intervention | Lower exposure to intervention | Other intervention/different combination of same intervention | ||

| Palmgreen 1991 | Influence of sensation‐seeking on drug use | X | X | ||||

| Kelly 1992 | Role of discussion on attitudes and opinions | X | X | ||||

| Polansky 1999 | Decision theory | X | X | ||||

| Miller 2000 | Self regulation theory | X | X | X | |||

| Palmgreen 2001 | Influence of sensation‐seeking on drug use | X | X | ||||

| Fishbein 2002 | Beliefs, norms or self efficacy | X | X | ||||

| Yzer 2003 | Theories of behavioral change: persuasion effects | X | X | X | |||

| Slater 2006 | Social‐ecological framework (norms and expectations influence drug use) | X | X | X | |||

| Zhao 2006 | Normative beliefs | X | X | ||||

| Czyzewska 2007 | Reactance theory | X | X | ||||

| Hornik 2006 | Unclear | X | X | X | X | ||

| Scheier 2010 | Social marketing | X | X | X | X | ||

| Schwinn 2010 | Social learning theory | X | X | ||||

| Lee 2010 | Readiness to change | X | X | ||||

| Fang 2010 | Family‐oriented | X | X | ||||

| Newton 2010 | Social influence approach | X | X | ||||

| Idaho Meth 2010 | Perception of risk and perception of social disapproval are correlated with drug consumption | X | X | X | X | ||

| Colorado Meth 2011 | |||||||

| Georgia Meth 2011 | |||||||

| Hawaii Meth 2011 | |||||||

| Wyoming Meth 2011 | |||||||

| Slater 2011 | Autonomy and aspiration perceptions as mediators marijuana use | X | X | X | |||

| Carpenter 2011 | Unclear; evaluated many heterogeneous mass media campaigns | X | X | X | X | ||

Outcome

The sum of studies described in this paragraph exceeds the number of included studies because many studies measured more than one outcome.

Sixteen studies measured the effect of mass media campaigns on illicit drugs use. Thirty‐six studies reported the following secondary outcomes (seven were without primary outcomes):

seven studies: intentions not to use/to reduce use/to stop use;

15 studies: attitudes towards illicit drug use;

two studies: knowledge about the effects of illicit drugs on health;

one study: understanding of intended message and objectives;

11 studies: perceptions (including perceptions of peer norms and perceptions about illicit drug use).

Country

Twenty‐one studies were conducted in the USA, one in the USA and Canada (Schwinn 2010), and one in Australia (Newton 2010).

Duration

No follow‐up was described, or was applicable, for seven studies (Carpenter 2011; Czyzewska 2007; Fishbein 2002; Palmgreen 1991; Polansky 1999; Yzer 2003; Zhao 2006). Follow‐up was shorter than 12 months for four studies (Fang 2010; Kelly 1992; Lee 2010; Schwinn 2010), and longer than or equal to 12 months for the remaining 12 studies.

Excluded studies

Several thousand studies were excluded after screening their title and abstract because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Fifty‐three studies required closer scrutiny and are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Four were excluded because the population studied did not meet the inclusion criteria; nine studies included interventions different from our inclusion criteria The remainder were excluded because the study design did not met the inclusion criteria.

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

Approximately half of the included studies are randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials. One of them is a mixed RCT‐cohort study (Slater 2011). The results of their 'Risk of bias' assessments are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3 and described in detail in Table 1.

2.

Randomised controlled trial 'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Randomised controlled trial 'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

1. 'Risk of bias' assessment of interrupted time series studies.

| Miller 2000 | ||

| Criterion | Score | Notes |

| a) Protection against secular changes | ||

| The intervention is independent of other changes | Done | "The usual environmental influences such as prices, taxes, state regulations, campus policies, and enforcement did not change substantially during the study period. Neither was there any reason to expect that students on the two campuses would respond differentially to anonymous surveys. The only obvious difference between the two campuses that might be expected to affect substance use differentially was the implementation of the prevention program at UNM", page 756 |

| There are sufficient data points to enable reliable statistical inference | Not done | 2 data points (before and after) |

| Formal test for trend. Complete this section if authors have used ANOVA modelling | Done | |

| b) Protection against detection bias | ||

| Intervention unlikely to affect data collection | Done | "All questionnaires were completed anonymously. To encourage participation, those who returned the survey (by mail) were entered into a lottery for cash prizes by separating a numbered ticket, returning one part with the completed survey and retaining the other half. Winning numbers were announced through the campus newspaper, the Daily Lobo. As an additional incentive for the follow‐up survey, respondents were invited to participate in a contest to guess the actual levels of alcohol/drug use on campus, as revealed by the first survey", page 750 |

| Blinded assessment of primary outcome(s) | Done | Anonymous surveys, page 750 |

| c) Completeness of data set | Done | "At baseline (fall) assessment, 1,400 surveys were distributed to enrolled UNM students, a sample of approximately 6% selected randomly by the university s computerized mailing list program. Of these, 567 surveys were returned and usable (41%). At the control campus, 1,080 surveys were distributed to a random sample of students, 457 of whom returned them (42.3%). [..] The return rates were 431 (31%) at UNM and 434 (34%) at NMSU", page 751 |

| d) Reliable primary outcome measure(s) | Done | "Use measures (14 items) included a frequency (number of drinking days per 30) and quantity index of drinking (number of standard drinks consumed per drinking occasion; range: 0‐15) that were multiplied to form a single quantity frequency measure (number of drinks per month) [..]", page 750 "Problem measures included 14 indicators of alcohol dependence and adverse consequences of heavy drinking or illicit drug use in the prior year. [..]", page 750 "Risk assessment included 13 items regarding the extent to which students perceived risk or consequences related to alcohol or other drug use [..]", page 750 |

| Palmgreen 2001 (includes Stephenson 1999) | ||

| Criterion | Score | Notes |

| a) Protection against secular changes | ||

| The intervention is independent of other changes | Unclear | |

| There are sufficient data points to enable reliable statistical inference | Done | 32 data points |

| Formal test for trend. Complete this section if authors have used ANOVA modelling | Done | ANOVA modelling was used. See from page 186 on |

| b) Protection against detection bias | ||

| Intervention unlikely to affect data collection | Done | Methodology of data collection is not reported to have changed across data points |

| Blinded assessment of primary outcome(s) | Done | Anonymous computer‐administered questionnaire (p. 293) |

| c) Completeness of data set | Unclear | |

| d) Reliable primary outcome measure(s) | Done | 30‐day use of marijuana, attitudes, beliefs, intentions |

| Idaho Meth 2010, Colorado Meth 2011, Georgia Meth 2011, Hawaii Meth 2011 and Wyoming Meth 2011 | ||

| Criterion | Score | Notes |

| a) Protection against secular changes | ||

| The intervention is independent of other changes | Unclear | |

| There are sufficient data points to enable reliable statistical inference | Done | Data points for each study ranged from 2 to 4 including only one baseline survey. However, overall, there are a sufficient number of observations |

| Formal test for trend. Complete this section if authors have used ANOVA modelling | Not done | |

| b) Protection against detection bias | ||

| Intervention unlikely to affect data collection | Done | Despite some slight changes, methodology of data collection is consistent across studies and across data points |

| Blinded assessment of primary outcome(s) | Done | Anonymous questionnaires |

| c) Completeness of data set | Unclear | Not applicable |

| d) Reliable primary outcome measure(s) | Done | Past‐month use of marijuana, attitudes, perceptions |

| Carpenter 2011 | ||

| Criterion | Score | Notes |

| a) Protection against secular changes | ||

| The intervention is independent of other changes | Done | Adjustment by many individual and market variables (page 949) |

| There are sufficient data points to enable reliable statistical inference | Not done | 3 data points (page 949) |

| Formal test for trend. Complete this section if authors have used ANOVA modelling | Done | "multivariate logistic regression" (page 949) |

| b) Protection against detection bias | ||

| Intervention unlikely to affect data collection | Done | Ads were broadcasted independently on the surveys |

| Blinded assessment of primary outcome(s) | Done | Monitoring the Future (MTF) surveys used anonymous questionnaires |

| c) Completeness of data set | Unclear | |

| d) Reliable primary outcome measure(s) | Done | Past‐month and lifetime marijuana use (page 951) |

Overall the quality of the included RCTs is acceptable: the stronger dimension is the consideration of risk of attrition bias (incomplete data addressed in the discussion) and the weaker dimension the risk of selection bias (unclear description of method for randomisation). More than half of the studies were clearly free of selective outcome reporting. In one case (Schwinn 2010) there was a clear indication of potential high risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Ecological factors are likely to interfere with the effect of a media campaign. These factors can include exposures to other media campaigns (advertisements), films or mass media debates directly addressing illicit drugs or other factors acting indirectly (for example, a popular singer who dies from an overdose).

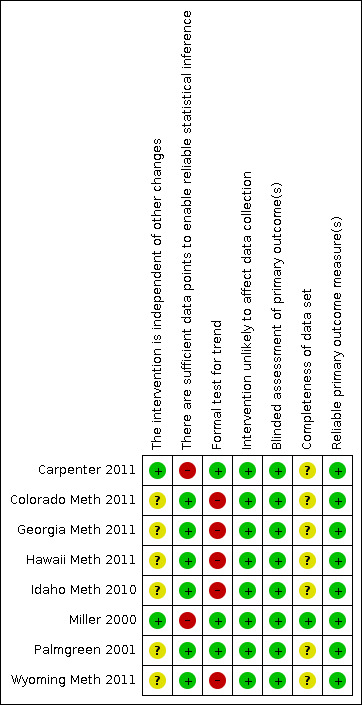

Interrupted time series (ITS) and before and after studies (CBA)

Six studies are ITS and two studies are CBA. The results of their 'Risk of bias' assessments are presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

4.

Interrupted time series 'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Interrupted time series 'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Overall the studies reported sufficient data points to enable reliable statistical inferences; they also had good strategies to ensure anonymous or computer‐administered questionnaires and to ensure that interventions did not affect data collection. The reliability of primary outcome measures was also satisfactory for all the studies. The weaker points were the lack of a formal test for trends and the unclear completeness of the data sets for many studies.

Prospective cohort studies (PCS)

Three studies are cohort studies and one of them is a mixed RCT‐cohort study (Slater 2011). The results of their 'Risk of bias' assessments are presented in Table 2, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

2. 'Risk of bias' assessment of cohort studies (Hornik 2006, Scheier 2010, Slater 2011).

| Hornik 2006 | ||

| Criterion | Score/Info | Notes |

| In a well‐conducted cohort study: | ||

| The study addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question | Well covered | "We examined the cognitive and behavioral effects of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign on youths aged 12.5 to 18 years and report core evaluation results", abstract |

| Selection of subjects | ||

| The 2 groups being studied are selected from source populations that are comparable in all respects other than the factor under investigation | Well covered | "The sample was selected to provide an efficient and nearly unbiased cross‐section of US youths and their parents. Respondents were selected through a stratified 4‐stage probability sample design: 90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2229‐30 |

| The study indicates how many of the people asked to take part did so, in each of the groups being studied | Well covered | Evaluation of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings, Appendix A, page A‐6, table A‐1 and page A‐11 tables A‐8 to A‐10 |

| The likelihood that some eligible subjects might have the outcome at the time of enrolment is assessed and taken into account in the analysis | Well covered | "Analyses were restricted to youths who were nonusers of marijuana at the current round (for cross‐sectional analyses) or at the previous round (for lagged analyses).", page 2232 |

| What percentage of individuals or clusters recruited into each arm of the study dropped out before the study was completed | 35% | "The overall response rate among youths for the first round was 65%, with 86% to 93% of still eligible youths interviewed in subsequent rounds.", page 2230 Evaluation of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings, page 2‐12, table 2‐A "Completed interviews by wave" |

| Comparison is made between full participants and those lost to follow‐up, by exposure status | Not reported | |

| Assessment | ||

| The outcomes are clearly defined | Well covered | "For 3 reasons, all drug‐related measures reported here relate to marijuana use. [..] Four measures or indices represented the following constructs: (1) marijuana intentions, (2) marijuana beliefs and attitudes, (3) social norms, and (4) self‐efficacy to resist use.", page 2230 |

| The assessment of outcome is made blind to exposure status | Not applicable | Blinding to exposure status was not applicable for this study |

| Where blinding was not possible, there is some recognition that knowledge of exposure status could have influenced the assessment of outcome | Well covered | "A measure of general exposure to antidrug advertising was derived from responses to questions about advertising recall for each medium or media grouping: television and radio, print, movie theatres or videos, and outdoor advertising.", page 2230 |

| The measure of assessment of exposure is reliable | Well covered | "For 3 reasons, all drug‐related measures reported here relate to marijuana use.", page 2230 |

| Evidence from other sources is used to demonstrate that the method of outcome assessment is valid and reliable | Well covered | "For 3 reasons, all drug‐related measures reported here relate to marijuana use. First, marijuana is by far the illicit drug most heavily used by youths. Second, for other drugs, the low levels of use meant that the NSPY sample sizes were not large enough to detect meaningful changes in use with adequate power. Third, to the extent that the campaign did target a specific drug, it was almost always marijuana. [..] The cognitive measures were developed on the basis of 2 health behavior theories, the theory of reasoned action and social cognitive theory", page 2230 |

| Exposure level or prognostic factor is assessed more than once | Well covered | "3 nationally representative cohorts of US youths aged 9 to 18 years were surveyed at home 4 times.", abstract |

| Confounding | ||

| The main potential confounders are identified and taken into account in the design and analysis | Well covered | "Potential confounder measures. The analyses employed propensity scoring for confounder control by weighting adjustments,9–14 incorporating a wide range of standard demographic variables and variables known to be related to youths' drug use or thought likely to be related to exposure to antidrug messages. Propensity scores were developed for the general and specific exposure measures. More than 150 variables were considered possible confounders.", page 2231 |

| Statistical analysis | ||

| Have confidence intervals been provided? | Well covered | Tables 1‐4, pages 2233‐4 |

| Overall assessment of the study | ||

| How well was the study done to minimise the risk of bias or confounding, and to establish a causal relationship between exposure and effect? Code ++,+, or − |

++ | Propensity scoring from 150 confounders, page 2231 |

| Taking into account clinical considerations, your evaluation of the methodology used, and the statistical power of the study, are you certain that the overall effect is due to the exposure being investigated? | Yes | This study includes very good control for possible confounders |

| Are the results of this study directly applicable to the patient group targeted in this guideline? | Unclear | Results are applicable to US youth; it is unclear whether they are generalisable outside the US |

| Description of the study | ||

| Do we know who the study was funded by? | Public Funds (NIDA), Government (Congress) | "Research for and preparation of this article were supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (grants 3‐N01‐DA085063‐002 and 1‐R03‐DA‐020893‐01). The evaluation of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign was funded by Congress as part of the original appropriation for the campaign. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy directly supervised the campaign. The National Institute on Drug Abuse supervised the evaluation; Westat, with the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania as a subcontractor, received the contract. All authors were funded for this evaluation and other projects by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.", page 2235 |

| How many centres are patients recruited from? | USA as a whole | "90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2230 |

| From which countries are patients selected? (Select all those involved. Note additional countries after 'Other') | USA | |

| What is the social setting (i.e. type of environment in which they live) of patients in the study? | Mixed | "More than 150 variables were considered possible confounders. [..] They include [..] urban–rural residency; [..]", page 2231 |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be INCLUDED in the study? | 4‐stage selection | "Respondents were selected through a stratified 4‐stage probability sample design: 90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2229‐30 |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be EXCLUDED from the study? | Youth living in boarding schools and college dormitories | "As mentioned previously, youth residing in group quarters were not eligible for selection in any of the three recruitment waves. Thus, youth living in boarding schools and college dormitories were excluded from the scope of the survey. This exclusion was made because it was felt that dormitory residents could not be easily interviewed at their parents' homes and that their experiences were so", Report, A‐10 |

| What intervention or risk factor is investigated in the study? (Include dosage where appropriate) | The National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign | |

| What comparisons are made in the study (i.e. what alternative treatments are used to compare the intervention/exposure with). Include dosage where appropriate | Lower exposure versus higher exposure to anti‐drug campaign | "The analyses reported here were based on 3 types of measures: recalled exposure to antidrug messages aired by the campaign and other sources; cognitions and behavior related to marijuana, as outcomes; and individual and household characteristics, including a wide range of variables known to be related to drug cognitions and use and to exposure to antidrug messages.", page 2230 |

| What methods were used to randomise patients, blind patients or investigators, and to conceal the randomisation process from investigators? | Randomisation: not applicable, but propensity scoring was employed Blinding of patients: not applicable Blinding of investigators: not reported Randomisation concealment: not applicable |

|

| How long did the active phase of the study last? | September 1999 to June 2004 (58 months) | |

| How long were patients followed up for, during and after the study? | November 1999 to June 2004 (56 months). | |

| List the key characteristics of the patient population. Note if there are any significant differences between different arms of the trial | Representative of US youths aged 9 to 18 | "The sample was selected to provide an efficient and nearly unbiased cross‐section of US youths and their parents", page 2229 |

| Record the basic data for each arm of the study. If there are more than 4 arms, note data for subsequent arms at the bottom of the page | Tables 1‐4, pages 2233‐4 | |

| Record the basic data for each IMPORTANT outcome in the study. If there are more than 4, note data for additional outcomes at the bottom of the page | Tables 1‐4, pages 2233‐4 | |

| Notes. Summarise the authors' conclusions. Add any comments on your own assessment of the study, and the extent to which it answers your question | Through June 2004, the campaign is unlikely to have had favourable effects on youths and may have had delayed unfavourable effects The evaluation challenges the usefulness of the campaign |

|

| Scheier 2010 | ||

| Criterion | Score/Info | Notes |

| In a well‐conducted cohort study: | ||

| The study addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question | Well covered | "In this study, we examined whether awareness (recall) of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign (NYADMC) benefited youth by attenuating their drug use.", abstract |

| Selection of subjects | ||

| The 2 groups being studied are selected from source populations that are comparable in all respects other than the factor under investigation | Well covered | Same as Hornik 2008 ("The sample was selected to provide an efficient and nearly unbiased cross‐section of US youths and their parents. Respondents were selected through a stratified 4‐stage probability sample design: 90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2229‐30) |

| The study indicates how many of the people asked to take part did so, in each of the groups being studied | Well covered | Same as Hornik 2008 (Evaluation of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings, Appendix A, page A‐6, table A‐1 and page A‐11 tables A‐8 to A‐10) |

| The likelihood that some eligible subjects might have the outcome at the time of enrolment is assessed and taken into account in the analysis | Well covered | Same questionnaire was administered at baseline and at follow‐up. "National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY) [..] could be used to assess youths' awareness of the campaign messages and monitor any corresponding changes in drug use trends.", page 241‐2 |

| What percentage of individuals or clusters recruited into each arm of the study dropped out before the study was completed | 35% | Same as Hornik 2008 ("The overall response rate among youths for the first round was 65%, with 86% to 93% of still eligible youths interviewed in subsequent rounds. ", page 2230 Evaluation of the National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings, page 2‐12, table 2‐A "Completed interviews by wave") |

| Comparison is made between full participants and those lost to follow‐up, by exposure status | Well covered | "Attrition analyses were structured to determine whether certain factors operate systematically to cause dropout from the study. Proportional analyses using the v2 test were used for cross tabulation of binary measures and logistic regression modelling to examine the optimal predictors of retention (coded '1' stay and '0' dropout). We used the WesVar software program to estimate logistic regression models of panel attrition. This statistical modelling program enables us to adjust (through poststratification) the sample variance estimators for the undersampling of primary sampling units and correct any bias in parameter estimates related directly to the complex sampling design (using replicate variance estimators to adjust standard errors for design effects). Proportional tests indicated that panel youth were significantly more likely to be female, smoke more cigarettes, drink alcohol, and smoke marijuana (all v2 proportional tests significant at the p .0001) compared with dropout youth. Given the large number of variables possibly related to retention status, logistic models were run separately for five individual domains (demographics, campaign awareness, drug use, school‐related factors, and psychosocial risk).7 Following tests of the individual domains, we culled only significant predictors and tested these in a combined model predicting retention. The final model indicated that retained youth were less at risk for marijuana use (unstandardized b =‐3.51, p<= .0001, OR =.03), engaged in more antisocial behavior (evidencing suppression: [b = .23, p <=.0001, OR = 1.26]), spent fewer hours listening to the radio on a daily basis (b =‐.09, p <=.01, OR = .91), and were more likely to have attended school in the past year (b = 1.05, p<= .01, OR = 2.87) compared with their dropout counterparts. Using the Cox‐Snell likelihood pseudo‐R2 statistic, the model accounted for 12% of the variance in retention status, F(14,87) = 12.127, p <=.0001.", page 250 |

| Assessment | ||

| The outcomes are clearly defined | Well covered | "Assessment of alcohol and drug use relied on an Anonymous Computer Assisted Self‐report Interview (ACASI). Two alcohol use items6 assessed being drunk or high ("How many times were you drunk or very high from alcohol in the last 12 months?") with response categories ranging from "I don't use alcohol" (0) through "40 or more occasions" (7); and heavy alcohol use based on a measure of binge drinking ("How many days have you had five or more drinks in the last 30 days?") with response categories ranging from "I don't drink" (0) through "10 or more times" (6). Cigarette use was assessed with a single item ("How many cigarettes smoked a day during the last 30 days?") with response categories ranging from "None" (0) through "More than 35 per day, about 2 packs or more" (7). A single frequency item assessed marijuana involvement ("How many times have you used marijuana in the last 12 months?") with response categories ranging from "I have never used marijuana" (0) through "40 or more occasions" (6).", page 248 |

| The assessment of outcome is made blind to exposure status | Not applicable | Blinding to exposure status was not applicable for this study |

| Where blinding was not possible, there is some recognition that knowledge of exposure status could have influenced the assessment of outcome | Not reported | |

| The measure of assessment of exposure is reliable | Well covered | "Turning to the campaign awareness parameters, we see two findings worth noting. First, growth in campaign awareness is positive for the earlier years (12 to 14), except for television viewing behavior, which had a slope not significantly different from zero. As these youth became older (14 to 18), their awareness declined for every media venue except specific recall (videos shown on laptops) and radio listening behavior. Also, the magnitude of the slope terms were considerably larger at the younger age for recall of stories about drugs and youth, brand awareness, specific recall, and radio listening but larger in magnitude for television (declining) as these youth transitioned to high school.", page 253 "Figure 2 graphically presents a generic template for testing the bivariate cohort growth models. Again, two slope trends are posited to capture the different rates of growth for youth when they were younger versus when they were older, and this is repeated for both drug use (D) and awareness (A) measures.", page 253 |

| Evidence from other sources is used to demonstrate that the method of outcome assessment is valid and reliable | Well covered | "Assessment of alcohol and drug use relied on an Anonymous Computer Assisted Self‐report Interview (ACASI). Two alcohol use items6 assessed being drunk or high ("How many times were you drunk or very high from alcohol in the last 12 months?") with response categories ranging from "I don't use alcohol" (0) through "40 or more occasions" (7); and heavy alcohol use based on a measure of binge drinking ("How many days have you had five or more drinks in the last 30 days?") with response categories ranging from "I don't drink" (0) through "10 or more times" (6). Cigarette use was assessed with a single item ("How many cigarettes smoked a day during the last 30 days?") with response categories ranging from "None" (0) through "More than 35 per day, about 2 packs or more" (7). A single frequency item assessed marijuana involvement ("How many times have you used marijuana in the last 12 months?") with response categories ranging from "I have never used marijuana" (0) through "40 or more occasions" (6).", page 248 |

| Exposure level or prognostic factor is assessed more than once | Well covered | Yes: 4 rounds of data collection. Table 1, page 249 |

| Confounding | ||

| The main potential confounders are identified and taken into account in the design and analysis | Not reported | |

| Statistical analysis | ||

| Have confidence intervals been provided? | No | Page 264 |

| Overall assessment of the study | ||

| How well was the study done to minimise the risk of bias or confounding, and to establish a causal relationship between exposure and effect? Code ++, +, or − |

‐ | "...there was no "intervention" to speak of, but rather the campaign took shape as a naturalistic observational study conducted at a particular point in time with no clear demarcation from various historical influences that could affect patterns of reported drug use", page 264 |

| Taking into account clinical considerations, your evaluation of the methodology used, and the statistical power of the study, are you certain that the overall effect is due to the exposure being investigated? | No, because no adjustment for confounders was reported | |

| Are the results of this study directly applicable to the patient group targeted in this guideline? | Unclear | Results are applicable to US youth; it is unclear whether they are generalisable outside the US |

| Description of the study | ||

| Do we know who the study was funded by? | No | |

| How many centres are patients recruited from? | USA as a whole | Same as Hornik 2008 ("90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2230) |

| From which countries are patients selected? (Select all those involved. Note additional countries after 'Other') | USA | |

| What is the social setting (i.e. type of environment in which they live) of patients in the study? | Mixed | Same as Hornik 2008 ("More than 150 variables were considered possible confounders. [..] They include [..] urban–rural residency; [..]", page 2231) |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be INCLUDED in the study? | 4‐stage selection | Same as Hornik 2008 ("Respondents were selected through a stratified 4‐stage probability sample design: 90 primary sampling units—typically county size—were selected at the first stage, geographical segments were selected within the sampled primary sampling units at the second stage, households were selected within the sampled segments at the third stage, and then, at the final stage, 1 or 2 youths were selected within each sampled household, as well as 1 parent in that household.", page 2229‐30) |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be EXCLUDED from the study? | Youth living in boarding schools and college dormitories | Same as Hornik 2008 ("As mentioned previously, youth residing in group quarters were not eligible for selection in any of the three recruitment waves. Thus, youth living in boarding schools and college dormitories were excluded from the scope of the survey. This exclusion was made because it was felt that dormitory residents could not be easily interviewed at their parents' homes and that their experiences were so", Report, Appendix A, A‐10) |

| What intervention or risk factor is investigated in the study? (Include dosage where appropriate) | The National Youth Anti‐Drug Media Campaign | "...there was no "intervention" to speak of, but rather the campaign took shape as a naturalistic observational study conducted at a particular point in time with no clear demarcation from various historical influences that could affect patterns of reported drug use", page 264 |

| What comparisons are made in the study (i.e. what alternative treatments are used to compare the intervention/exposure with). Include dosage where appropriate | Exposure versus drug use | Varius models, e.g. see page 256 |

| What methods were used to randomise patients, blind patients or investigators, and to conceal the randomisation process from investigators? | Randomisation: not applicable Blinding of patients: not applicable Blinding of investigators: not reported Randomisation concealment: not applicable | |

| How long did the active phase of the study last? | September 1999 to June 2004 (58 months) | |

| How long were patients followed up for, during and after the study? | November 1999 to June 2004 (56 months) | |

| List the key characteristics of the patient population. Note if there are any significant differences between different arms of the trial | Representative of US youths aged 9 to 18 | Same as Hornik 2008 ("The sample was selected to provide an efficient and nearly unbiased cross‐section of US youths and their parents", page 2229) |

| Record the basic data for each arm of the study. If there are more than 4 arms, note data for subsequent arms at the bottom of the page | Table 2, page 251 | |

| Record the basic data for each IMPORTANT outcome in the study. If there are more than 4, note data for additional outcomes at the bottom of the page | Tables 3‐4‐5, pages 252‐7 | |

| Notes. Summarise the authors' conclusions. Add any comments on your own assessment of the study, and the extent to which it answers your question | When they were younger, these youth accelerated their drug use and reported increasing amounts of campaign awareness. When they were older, [..] no effects for marijuana were significant but trended in the direction of increased awareness associated with declining drug use |

"Behavior change is guided by the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA: Ajzen & Fishbein, 1973, 1977) and draws also from social persuasion (McGuire, 1961, 1966, 1968) and communication theories (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953). According to the TRA, the influence of attitudes (i.e., subjective evaluations of behavior consequences) and beliefs (subjective norms and behavioral outcomes or expectancies) on behavior is mediated through intentions (i.e., future intent to engage the behavior). In other words, youth form impressions of whether drugs are good or bad, and they combine this information with normative beliefs (whether their close friends approve of drug use) and behavioral expectations (perceived benefits and negative consequences of drug use) toward drug use. These steps are necessary but not sufficient conditions, as the final decision to use drugs is guided by their behavioral willingness or intentions.", page 242 "To date, analyses of the media campaign efficacy have used traditional linear regression or correlation techniques to examine campaign effects. While this tactic has been useful to delineate the basic statistical associations between campaign awareness and drug use, a major weakness of this approach is that it fails to provide a developmental perspective and incorporate systematic features of change in either awareness or drug use.[..] Growth modelling is clearly a more definitive way to address the question of change and increasingly has been advocated as a means to assess prevention effects that unfold over time (Brown, Catalano, Fleming, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2005; Mason, Kosterman, Hawkins, Haggerty, & Spoth, 2003; Park et al., 2000; Taylor, Graham, Cumsille, & Hansen, 2000). [..] The age mixture within each round makes it imperative to estimate growth using age‐ cohort models", page 242‐3 |

| Slater 2011 | ||

| Criterion | Score/Info | Notes |

| In a well‐conducted cohort study: | ||

| The study addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question | Well covered | "...(a) provide two simultaneous tests of autonomy and aspiration perceptions as mediators of impact on marijuana use as a consequence of exposure to each of these campaigns, b) conduct the first independent assessment of the ONDCP media campaign, which did not have a formal independent evaluation in place during the years of this study, and c) assess the simultaneous impact of a national campaign and a similar community/in‐school effort.", page 12‐13 |

| Selection of subjects | ||

| The 2 groups being studied are selected from source populations that are comparable in all respects other than the factor under investigation | Not reported | "3,236 students participated in at least one survey, with 48% males, 52% females and a mean age at baseline of 12.4 years (SD = 0.6); 75% were European‐American, 11.5% African‐American, and 13.5% of other racial backgrounds. One‐quarter of the youth were of Hispanic ethnicity.", page 15 |

| The study indicates how many of the people asked to take part did so, in each of the groups being studied | Poorly addressed | Only average: "The average rate of student participation in each school was 32% of total student enrolment, lower than the prior study because of stricter IRB requirements being imposed on recruitment procedures. 57.1% of respondents provided data at all four measurement occasions; 27.2% provided data on three, 9.4% provided data on two and 5.3% provided data on just one of the measurement occasions. Missed surveys appear to be a matter more of absenteeism or slips in getting students to survey sessions, than of panel mortality; 84.5% of participants filled out the wave 1 survey, 86.2% wave 2, 86.1% wave 3, and 81.3% wave 4.", page 15 |

| The likelihood that some eligible subjects might have the outcome at the time of enrolment is assessed and taken into account in the analysis | Well covered | "Lifetime use of marijuana was measured at each measurement wave [..]", page 15 |

| What percentage of individuals or clusters recruited into each arm of the study dropped out before the study was completed | 42.9% | "The average rate of student participation in each school was 32% of total student enrolment, lower than the prior study because of stricter IRB requirements being imposed on recruitment procedures. 57.1% of respondents provided data at all four measurement occasions; 27.2% provided data on three, 9.4% provided data on two and 5.3% provided data on just one of the measurement occasions. Missed surveys appear to be a matter more of absenteeism or slips in getting students to survey sessions, than of panel mortality; 84.5% of participants filled out the wave 1 survey, 86.2% wave 2, 86.1% wave 3, and 81.3% wave 4.", page 15 |

| Comparison is made between full participants and those lost to follow‐up, by exposure status | Not reported | |

| Assessment | ||

| The outcomes are clearly defined | Well covered | "Autonomy and Aspirations Inconsistent With Marijuana Use Autonomy inconsistent with marijuana use was measured using responses to four items following the phrase "Not using marijuana": 1) is a way to be true to myself; 2) is an important part of who I am; 3) is a way of being in control of my life; and 4) is a way of showing my own independence, where responses ranged from 1 = definitely disagree to 4 = definitely agree. Similarly, aspirations inconsistent with marijuana use were measured using the responses to three items following the phrase "Using marijuana would: 1) keep me from doing the things I want to; 2) mess up my plans for when I am older; and 3) get in the way of what is important to me." Because responses to each scale's items were heavily skewed, with 82% of respondents selecting "definitely agree" for all aspiration items and 84% of respondents selecting "definitely agree" for all autonomy items, each scale was dichotomized such that a "1" was assigned if all responses to the scale items were "definitely agree" and a "0" otherwise. The Cronbach's alpha values (Cronbach 1951) for each dichotomized measure were .9 or greater at each of the four waves. Marijuana Use Lifetime use of marijuana was measured at each measurement wave using four questions: "How old were you the first time you used marijuana?", "How often in the last month have you used marijuana?", "How often in the last 3 months have you used marijuana?", and "Have you ever tried marijuana? (pot, grass, hash, etc.)?" If a subject responded affirmatively to any one question (or indicated an age when they first used marijuana), lifetime marijuana use was scored a "1", while an indication of never using marijuana resulted in a score of "0". The reliability for the scale was above 0.7 for the first two measurement occasions, .64 on the third occasion, and .69 at the fourth occasion.", page 15 |

| The assessment of outcome is made blind to exposure status | Not applicable | Blinding to exposure status was not applicable for this study |

| Where blinding was not possible, there is some recognition that knowledge of exposure status could have influenced the assessment of outcome | Not reported | |

| The measure of assessment of exposure is reliable | Well covered | p. 15 |

| Evidence from other sources is used to demonstrate that the method of outcome assessment is valid and reliable | Well covered | = 1.7 |

| Exposure level or prognostic factor is assessed more than once | Well covered | 4 waves, page 17 |

| Confounding | ||

| The main potential confounders are identified and taken into account in the design and analysis | Adequately addresses | p. 16 |

| Statistical analysis | ||

| Have confidence intervals been provided? | Well covered | Standard errors, e.g. Table 1 and 2, p. 18 |

| Overall assessment of the study | ||

| How well was the study done to minimise the risk of bias or confounding, and to establish a causal relationship between exposure and effect? Code ++, +, or − |

+ | |

| Taking into account clinical considerations, your evaluation of the methodology used, and the statistical power of the study, are you certain that the overall effect is due to the exposure being investigated? | Fairly: selectivity (do no know if representative); no propensity scoring for national media campaign | |

| Are the results of this study directly applicable to the patient group targeted in this guideline? | Unclear | Results are applicable to US youth; it is unclear whether they are generalisable outside the US |

| Description of the study | ||

| Do we know who the study was funded by? | Public Funds (NIDA) | "This research was supported by grant DA12360 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to the first author.", page 12 |

| How many centres are patients recruited from? | 20 communities | |

| From which countries are patients selected? (Select all those involved. Note additional countries after 'Other') | USA | |

| What is the social setting (i.e. type of environment in which they live) of patients in the study? | Mixed | p. 14 |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be INCLUDED in the study? | IRB requirements | "The average rate of student participation in each school was 32% of total student enrolment, lower than the prior study because of stricter IRB requirements being imposed on recruitment procedures", page 15 |

| What criteria are used to decide who should be EXCLUDED from the study? | Exaggerators | "Students who responded that they had tried all drugs listed including one that had been invented were considered exaggerators and were excluded from analyses; there were no more than 0.4% of such exaggerators in any given wave of data collection.", page 15 |

| What intervention or risk factor is investigated in the study? (Include dosage where appropriate) | (a) school‐ and community‐based media intervention 'Be Under Your Influence' and (b) national anti‐drug media campaign 'Above the Influence' | p. 12 |

| What comparisons are made in the study (i.e. what alternative treatments are used to compare the intervention/exposure with). Include dosage where appropriate | Exposure versus drug use/aspirations/autonomy; exposure x time versus drug use/aspirations/autonomy | |

| What methods were used to randomise patients, blind patients or investigators, and to conceal the randomisation process from investigators? | Randomisation: not applicable for mass media campaign, but done for 'Be Under Your Own Influence' school‐ and community‐based media intervention | |