Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is characterised by partially reversible airflow limitation. Many patients have little reversibility to short acting bronchodilators, but long acting bronchodilators are frequently advocated.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of long acting beta‐2 adrenoceptor agonists (LABAs) in COPD patients demonstrating poor reversibility to short‐acting bronchodilators.

Search methods

The Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register was searched ('all years' to 2005) along with the reference lists from identified randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Selection criteria

All RCTs comparing inhaled LABAs (salmeterol or formoterol) with placebo in the treatment of patients with stable, poorly reversible COPD. Studies were a minimum of four weeks in duration.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently performed data extraction and study quality assessment. If we required additional data, we contacted authors and pharmaceutical companies sponsoring the identified RCTs.

Main results

Twenty‐three published and unpublished studies (6061 participants) were included in the review. There was a significant change in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) in favour of salmeterol 50 mcg twice daily (BID) of 51 mls (95% confidence intervals (CI) 32 to 70), end of study morning peak expiratory flow (PEF) 14.89 L/min (95% CI 10.86 to 18.91). Supplemental short‐acting bronchodilator usage was reduced by just under one puff per day. There were significant differences in the total, activity and impact domain scores of the St George's respiratory questionnaire in favour of salmeterol 50 mcg BID. Findings from other health status measurements and symptom scores were conflicting. There was no significant difference in exercise tolerance. The number of participants experiencing exacerbations was significantly reduced with salmeterol 50 mcg treatment compared with placebo (numbers needed to treat to benefit 24).

Authors' conclusions

This review shows that the treatment of patients with COPD with salmeterol 50 mcg produces modest increases in lung function. There were varying effects for other important outcomes such as health related quality of life or reduction in symptoms. However, there was a consistent reduction in exacerbations which may help people with COPD who suffer frequent deterioration of symptoms prompting healthcare utilisation. The strength of evidence for the use of salmeterol 100 mcg, formoterol 12 mcg, 18 mcg, 24 mcg was insufficient to provide clear indications for practice.

Keywords: Humans; Adrenergic beta‐Agonists; Adrenergic beta‐Agonists/therapeutic use; Albuterol; Albuterol/analogs & derivatives; Albuterol/therapeutic use; Bronchodilator Agents; Bronchodilator Agents/therapeutic use; Ethanolamines; Ethanolamines/therapeutic use; Formoterol Fumarate; Lung Diseases, Obstructive; Lung Diseases, Obstructive/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Salmeterol Xinafoate

Plain language summary

Long‐acting beta2‐agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

This review aims to determine the effectiveness of long‐acting beta‐agonists, salmeterol or formoterol, in the treatment of COPD (emphysema/chronic bronchitis). These drugs improve airflow in the lungs, and enable people with COPD to get on with their daily activities. Twenty‐four studies (6061 participants) reported the effects of LABAs in people with COPD. People taking salmeterol 50 mcg daily do have fewer exacerbations than those on placebo, and some improvement in lung function and certain quality of life scores. The findings were not consistent enough to support a general recommendation for the use of these drugs in the group of people with COPD with minimal variation in their lung function, although there is some evidence of improvement in important outcomes and these findings require further exploration in additional trials.

Background

COPD is characterised by airways obstruction that is not fully reversible. Even though many patients have a poor response to short acting bronchodilators, long‐acting beta‐2 adrenoceptor agonists are increasingly recommended for administration to all patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as regular long term therapy. These drugs are beneficial as additive maintenance therapy in the reversible airflow obstruction which occurs in asthma (Ni Chroinin 2005). It is important to establish whether this class of drugs has any benefit in COPD, particularly as they are relatively expensive to the health system. There are clear cost implications for healthcare budgets of prescribing long‐acting beta agonists and thus it is important to evaluate if there are any clear clinical benefits of use in terms of lung function, exercise tolerance, quality of life, exacerbations and rescue short acting beta‐agonist use. We therefore aim to review the literature to determine the evidence of the efficacy of this medication in patients with COPD who have a poor spirometric response to short acting bronchodilator.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of regular LABAs, administered via inhalation over at least four weeks to adults with COPD on:

Lung function, as measured by forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), Peak expiratory flow (PEF);

Exercise tolerance;

Quality of life;

Dyspnoea and symptoms;

Incidence of exacerbations;

Need for rescue salbutamol.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published, unpublished and ongoing RCTs, including parallel group and crossover design trials.

Types of participants

Participants with stable COPD without asthma as characterised by:

no recent infections, exacerbations, hospitalisations in the past month; and

FEV1 75% or less than predicted, FEV1/FVC less than 70% predicted; and

-

poor reversibility after a short dose of short acting beta‐2 agonist, defined as:

less than 15 % reversibility of FEV1 from baseline; or

less than 15 % reversibility of FEV1 as a % of the predicted normal value;

generally moderate severity of airways disease.

Types of interventions

Use of regular long‐acting beta‐2 adrenoceptor agonists (including salmeterol and formoterol or other), delivered via inhalation (metered dose inhaler or dry powder) for at least four weeks compared with placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Lung function tests, including FEV1 and PEF

Exercise tolerance, including six‐minute walk test

Health related quality of life (HRQL), including the St George's respiratory questionnaire (SGRQ), chronic respiratory diseases questionnaire (CRDQ), medical short form 36 (SF‐36), European quality of life questionnaire (EQ‐5D).

Dyspnoea and symptom measurements, including TDI, symptom scores

Exacerbations

Rescue medication use

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Trials Search Co‐coordinator searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register (July 2005). The Register is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL, and hand searching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. All records in the Register coded as 'COPD' were searched using the terms:

((beta* AND agonist*) AND long*) OR ((beta* AND adrenergic*) AND long*) OR (bronchodilator* AND long*) OR (salmeterol or formoterol or eformoterol or bambuterol or fenoterol)

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of identified RCTs to identify additional relevant references. Additional data were sought from online registers of published and unpublished clinical trial data (www.ctr.gsk.co.uk; www.astrazeneca.com; www.clinicalstudyresults.org).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Trials potentially suitable for inclusion in the review included all published and non‐published randomised controlled trials of parallel group or crossover design that were identified from titles, abstracts and keywords of references obtained in the literature search. We obtained full text versions of the studies wherever possible. Two authors assessed the suitability for inclusion, methodology and quality of the studies without consideration of the results. Differences were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Two authors extracted data from the trials independently, without blinding of authorship, onto standardised data extraction sheets. Qualitative data included the author, year of publication, setting, duration of study, baseline characteristics of participants and withdrawals. Quantitative data included dichotomous and continuous outcome measures. Standard errors were converted to standard deviations. We contacted authors and pharmaceutical companies sponsoring identified in an attempt to obtain missing and raw data. Data were estimated from graphs for some outcomes if values were not reported in the paper and we were unable to obtain the information from the authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed study quality according to whether studies met the following pre‐specified quality criteria (as yes, no or unclear, Handbook 2008):

Randomisation ‐ was sequence generation and allocation concealment adequate? Blinding ‐ were the treatments known to the patients, investigators and those assessing outcomes?

We also performed quality assessment of studies using the five point scale of Jadad 1996. Previous versions of this review applied both Jadad and Cochrane allocation concealment scores (Appendix 1).

Dealing with missing data

We have also attempted to minimise the impact of missing estimates of variance. If no standard deviations were reported in published or unpublished trial reports, and were not forthcoming following correspondence, we have imputed them based upon trials contributing to the same outcome. This has only been done if there are more than three studies with estimates of variance present in the analysis (see Table 1 for details of outcomes where this has been done). If only a P value has been reported and no standard deviations, we have estimated the standard error for the mean difference and entered the data as generic inverse variance (GIV).

1. Imputations.

| Comparison & Outcome | Study | Source of imputation |

| Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study (parallel study) | Gupta 2002 | SDs for Boyd 1997; Chapman 2002; Mahler 1999 and Hanania 2003 |

| Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study (parallel study) | SCO40030 | SDs for Boyd 1997; Chapman 2002; Mahler 1999 and Hanania 2003 |

Assessment of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity was investigated using the I2 statistic (An I2 > 20% was considered statistically significant heterogeneity (Higgins 2003)). Pooled effect estimates were reported from fixed‐effect modelling, but if I2 > 20% we carried out random‐effects modelling, and we explored possible reasons for the variation between the studies.

Data synthesis

Data were entered into Review Manager software by one author and checked by a second author. For dichotomous outcomes, we expressed results of the analyses as an odds ratio (OR, 95% confidence intervals (CI)). For continuous outcomes, results of the analyses were expressed as a mean difference (MD, 95% CI) or a standardised mean difference (SMD, 95% CI). SMDs were utilised to conduct pooled analysis of outcomes if there was variation in the method of reporting of those outcomes. If a more positive outcome is favourable (e.g. FEV1, CRDQ) data were entered as positive values to generate positive MDs. In this case, the titles of the horizontal axes have been reversed so that effects that favour the treatment under review move to the right.

We have calculated a number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) for efficacy outcomes and a number needed to treat to harm (NNTH) for safety variables. We have taken the combined control group event rate, and used this as an estimate of the baseline risk. We have used the pooled OR and 95% confidence intervals to estimate NNT from online visual Rx (www.nntonline.net).

The planned comparisons for meta‐analysis were:

Salmeterol versus placebo;

Formoterol versus placebo;

Other beta‐2 adrenoceptor agonist versus placebo

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroups identified for analysis a priori included:

Use of different long acting beta‐2 adrenoceptor agonists (salmeterol and formoterol, or other);

Different dosages;

Different study duration;

-

Reversibility as defined as:

less than 15 % reversibility of FEV1 from baseline;

less than 15 % reversibility of FEV1 as a % of the predicted normal value;

Different severity of airways disease.

A post‐hoc subgroup analysis related to (4) was also used to explore the consistency of effect between studies if the baseline reversibility met the inclusion criteria of the review, and in studies where this was not easy to ascertain (mainly unpublished trial reports, which did not provide extensive details of methodological design and entry criteria).

Results

Description of studies

Twenty‐three studies met the eligibility criteria of the review. These studies recruited 6061 participants.

There were 15 published RCTs identified describing the effects of LABAs, administered via inhalation over at least four weeks to adults with poorly reversible COPD. Two definitions for reversibility to a short‐acting beta agonist were considered in this review. Reversibility to a short acting beta agonist was defined as a less than 15% reversibility of FEV1 from baseline in eleven studies including the Ulrik 1995; Grove 1996; Boyd 1997; Mahler 1999; van Noord 2000; Rennard 2001; Rossi 2002; Gupta 2002; Mahler 2002; Celli 2003 and Hanania 2003 studies. Reversibility to a short acting beta agonist was defined as a less than 15% reversibility of predicted normal FEV1 in four studies including the Chapman 2002; Wadbo 2002; Calverley 2003 and Dal Negro 2003 studies. Four studies included participants with both reversible and poorly‐reversible COPD including the Rennard 2001; Mahler 2002; Rossi 2002 and Hanania 2003 studies and presented stratified results. From these studies, only the patient subgroups with poorly‐reversible COPD were included in this review.

An additional subset of eight unpublished RCTs have also been identified following hand searching of the GSK online trials register (408DP‐03; Dauletbaev 2001; SCO40030; SMS40298; SMS40314; SMS40315; SMS40318; Stockley 2002). These studies are presented as short documents. In only Dauletbaev 2001 and SMS40318 were baseline entry criteria sufficiently described to permit the findings from these studies to contribute to the primary set of analyses. The remainder did not provide sufficiently detailed entry criteria in order to determine whether the studies recruited reversible, non‐reversible or mixed populations. For this reason they contribute data as part of a series of sensitivity analyses.

Trials that included participants with both reversible and poorly reversible COPD, and met all other inclusion criteria, but did not report outcomes in the poorly reversible COPD groups, were excluded from this review if we were unable to obtain data from authors or drug companies. These trials included Anderson 1997; Mahler 1997; Dahl 2001; Donohue 2002; Aalbers 2002; Brusasco 2003; Calverley 2003a; and Szafranski 2003. Six abstracts were identified from recent American Thoracic Society meetings and European Respiratory Society Annual Congresses as requiring further information to assess the suitability for inclusion in this review. One ongoing study protocol (TORCH) was identified as meeting the requirements for inclusion in the review but the results of the study are not yet available. This will be the largest (approximately 6,200 participants) randomised, double blind, placebo controlled parallel group study for salmeterol 50 mcg when the results are expected to become available in 2006.

Participants

The sample sizes of the parallel studies were variable, in the range of 144 to 674 participants. Total number of participants contributing data from these studies was 5979. The crossover studies had small sample sizes of 63 and 29 participants.

Interventions

Eleven parallel group studies investigated the effects of salmeterol 50 mcg (Boyd 1997; Mahler 1999; van Noord 2000; Rennard 2001; Chapman 2002; Gupta 2002; Mahler 2002; Calverley 2003; Celli 2003; Dal Negro 2003; Hanania 2003). One parallel group study investigated the effect of salmeterol 100 mcg (Boyd 1997). There were two crossover studies which investigated the effects of salmeterol 50 mcg (Ulrik 1995; Grove 1996)

There was one parallel group study that investigated the effect of formoterol 12 mcg (Rossi 2002), one parallel group study that investigated the effect of formoterol 18 mcg (Wadbo 2002) and one parallel group study that investigated the effect of formoterol 24 mcg (Rossi 2002).

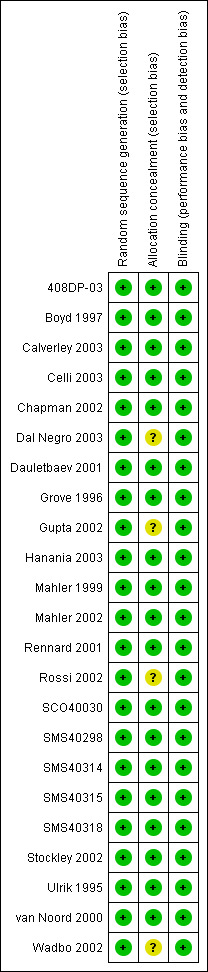

Risk of bias in included studies

Methods of randomisation were described adequately or obtained from authors or study sponsors for all of the studies (Figure 1). All studies were described as double blind, and appropriate means of masking treatment were confirmed for all the studies. Based on correspondence with GSK, we were able to ascertain that usual processes for generating randomisation schedules and concealing allocation were at a low risk of bias (Appendix 2). On the basis of these judgements, the studies were well‐designed and at a low risk of bias in terms of allocation and blinding.

1.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Eight studies commented on the number of participants excluded from the trials (Calverley 2003; Celli 2003; Chapman 2002; Dal Negro 2003; Grove 1996; Hanania 2003; Mahler 2002; Ulrik 1995). Thirteen studies commented on withdrawals and dropouts (Ulrik 1995; Boyd 1997; Mahler 1999; van Noord 2000; Rennard 2001; Chapman 2002; Mahler 2002; Rossi 2002; Stockley 2002; Wadbo 2002; Calverley 2003; Celli 2003; Dal Negro 2003; Hanania 2003; 408DP‐03; Dauletbaev 2001; SCO40030; SMS40298; SMS40314; SMS40315; SMS40318).

Effects of interventions

Meta‐analysis was only possible for some outcomes because of variation in the reporting of study outcomes.

(1) Lung function

Meta‐analyses were performed for mean FEV1 (mls) change from baseline, end of study pre‐bronchodilator FEV1, and mean FEV1 change from baseline (% predicted) due to variation between the studies in the reporting of data.

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg twice daily versus placebo

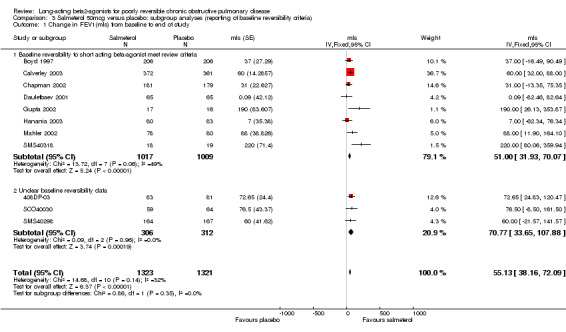

Change in FEV1 (mls)

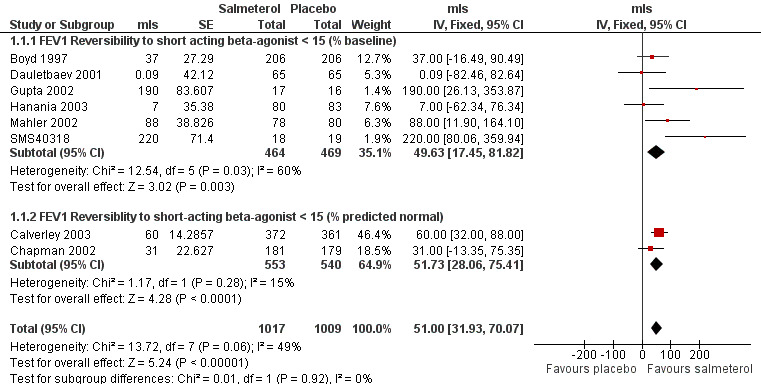

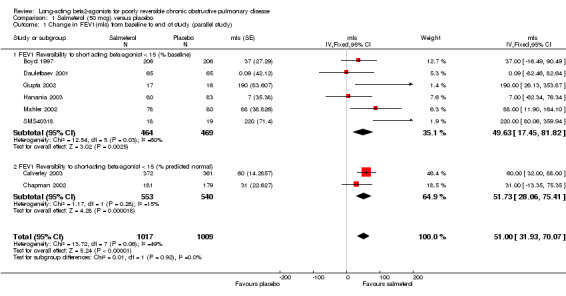

Boyd 1997; Calverley 2003; Chapman 2002; Dauletbaev 2001; Gupta 2002; Hanania 2003; Mahler 2002; SMS40318. There was a significant change in FEV1 (mls) in favour of salmeterol (MD 51 mls (95% CI 31.93 to 70.07), eight studies, N = 2026, Figure 2). There was a high degree of statistical heterogeneity (I2 49%). Celli 2003 reported no significant changes in FEV1, but no numerical data were provided.

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, outcome: 1.1 Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study (parallel study).

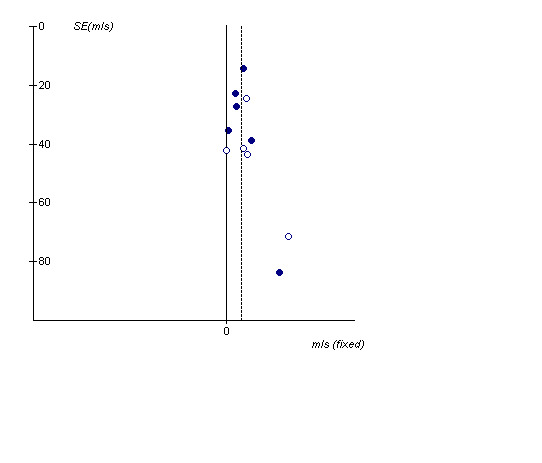

The inclusion of several unpublished trials (including three where baseline reversibility criteria were not easily established: 408DP‐03; SCO40030; SMS40298) did not significantly alter the pooled effect estimate or increase the level of statistical heterogeneity (MD 55.13 mls (95% CI 38.16 to 72.09; 11 studies, N = 2644; I2 0). Visual inspection of the funnel plot with and without these studies suggested that publication bias only partially influences the distribution of studies around the fixed effect (Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot demonstrating the distribution of effect sizes around the 'fixed' effect (vertical dotted line). The 'hollow' dots represent studies which were unpublished, the 'complete' dots represent data from published clinical trials

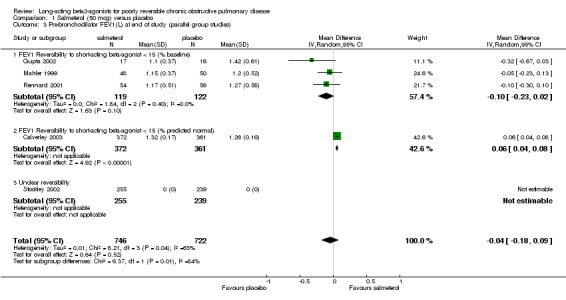

Absolute FEV1 (litres)

Mahler 1999; van Noord 2000; Rennard 2001; Gupta 2002; Calverley 2003 Pooled analysis showed no significant change in pre‐bronchodilator FEV1 with salmeterol (‐0.03 mls (95% CI ‐0.13 to 0.06), N = 1798. Statistical heterogeneity was high [I2 74.5%]. Additional studies contributing data for the subgroup of studies where baseline reversibility to short‐acting beta‐agonist was less than 15% predicted normal is required to see whether the observed difference between the subgroup estimates has validity.

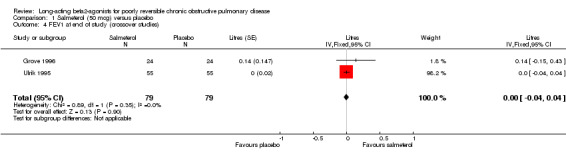

Two crossover studies involving 79 participants reported pre‐bronchodilator end of study FEV1 (Ulrik 1995; Grove 1996). Pooled analysis showed no significant difference between the two interventions (0 (95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.04)).

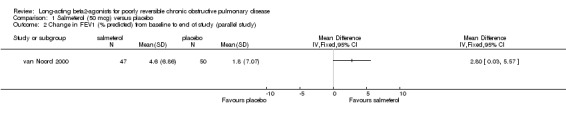

Change in FEV1 (% predicted)

One parallel group study involving 97 participants (van Noord 2000) reported a significant increase in mean FEV1 change from baseline (% predicted).

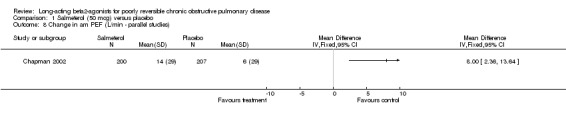

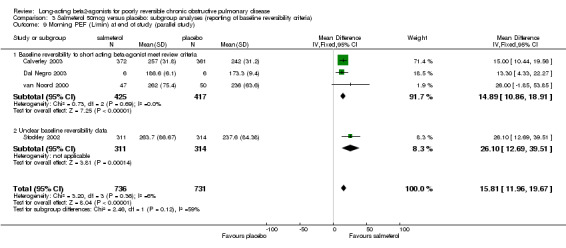

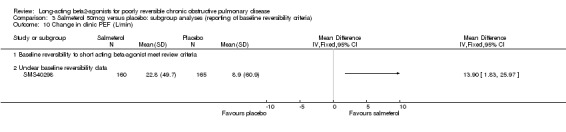

PEF (parallel group study)

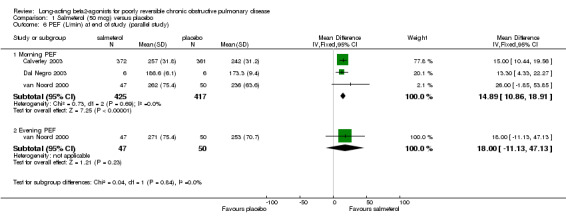

Morning PEF (L/min) at end of study (van Noord 2000; Stockley 2002; Calverley 2003; Dal Negro 2003): There was a significant difference in favour of salmeterol (15.81 L/min (95% CI 11.96 to 19.67), N = 1467).

Night time PEF (L/min) at end of study: van Noord 2000 reported no significant difference in end of study night time PEF (L/min).

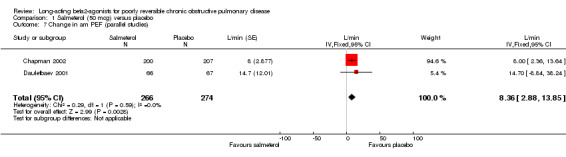

Change in PEF (L/min) morning (Chapman 2002; Dauletbaev 2001): There was a significant difference in favour of salmeterol (L/min 8.36 L/min (95% CI 2.88 to 13.85), N = 540).

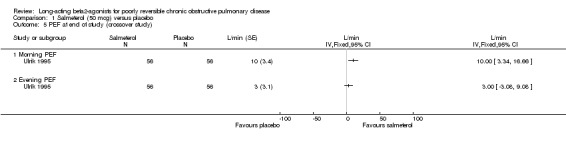

PEF (crossover study)

Morning and night time (L/min) at end of study: Ulrik 1995 reported a significant difference in morning PEF (10 L/min (95% CI 3.34 to 16.66), N = 55). However, there was no significant difference in evening PEF (3 L/min (95% CI ‐3.08 to 9.08).

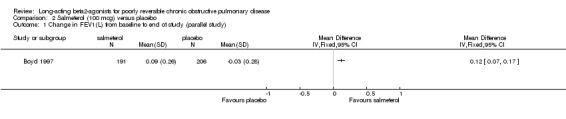

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

Change in FEV1

Boyd 1997 reported a significant change in FEV1 in favour of salmeterol (MD 0.12 Litres (95% CI: 0.07 to 0.17), N = 412).

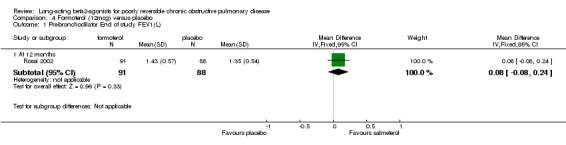

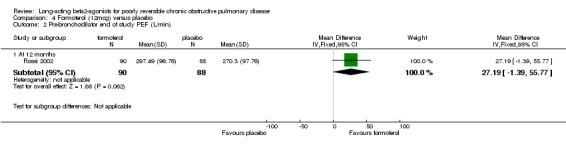

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg versus placebo

FEV1 (L)

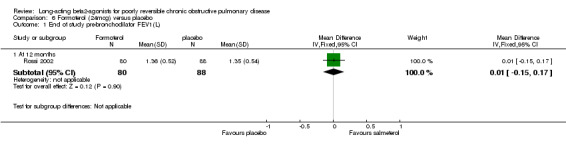

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in pre‐bronchodilator FEV1.

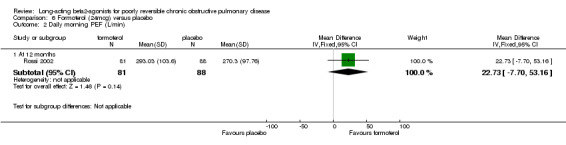

PEF (parallel group study)

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in pre‐bronchodilator PEF.

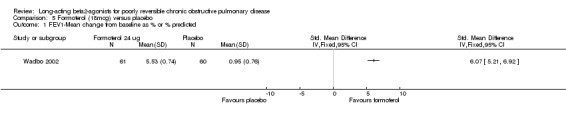

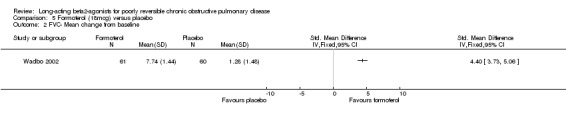

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

Mean change (% predicted FEV1)

Wadbo 2002 reported a significant mean change from baseline in % predicted FEV1 in favour of formoterol (6.07% (95% CI 5.12, 6.92), N = 121).

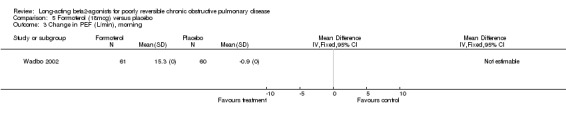

Change in morning PEF (L/min)

Wadbo 2002 reported a significant change in morning PEF (l/min) favouring formoterol, although no estimates of variance were available.

(e) Formoterol 24 mcg versus placebo

FEV1 (L)

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in pre‐bronchodilator FEV1.

PEF (L/min), morning

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in morning PEF (L/min).

(2) Exercise tolerance

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg versus placebo

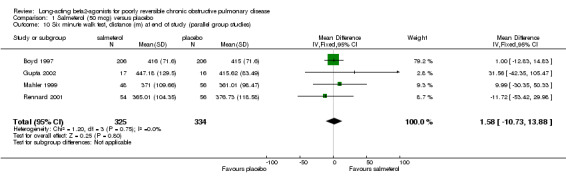

Six minute walk test, distance (metres) at end of study (parallel group study)

Boyd 1997; Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001; Gupta 2002 There was no significant difference between salmeterol or placebo groups in distance walked (1.58 metres (95% CI ‐10.73 to 13.88), N = 659).

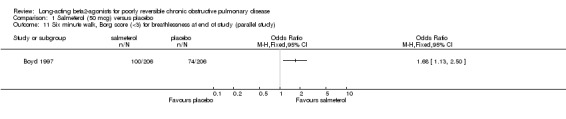

Six minute walk test, Borg score (< 3) for breathlessness at end of study

Boyd 1997 reported that significantly more patients in the salmeterol treated group had Borg scores less than three (three indicating moderate dyspnoea) compared with placebo (Peto OR 1.68 (95% CI 1.13 to 2.48), N = 412).

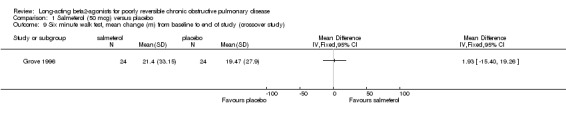

Six minute walk test, distance (m) at end of study (crossover study)

Grove 1996 reported no significant difference between salmeterol 50 mcg and placebo in the mean change in distance walked from baseline (1.93 (95% CI ‐15.40 to 19.26), N = 24).

Cycle ergometry (crossover study)

Grove 1996 reported no significant difference between salmeterol 50 mcg treatment and placebo for Borg scores and various physiological measurements including oxygen uptake, ventilation, heart rate and oxygen saturation (N = 24).

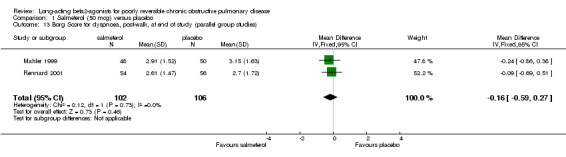

Six minute walk test, end of study post‐walk Borg dyspnoea scores

Borg dyspnoea scores were reported in two studies involving 208 participants (Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001). There was no significant difference between treatment groups (MD ‐0.16 (95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.27).

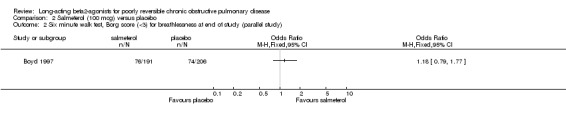

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

Boyd 1997 reported no significant difference in proportions of patients with Borg scores less than three (Peto OR 1.18 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.77)). Boyd 1997 reported no significant difference between salmeterol 100 mcg and placebo in the distance walked at six minutes but did not provide data values.

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg versus placebo

No studies.

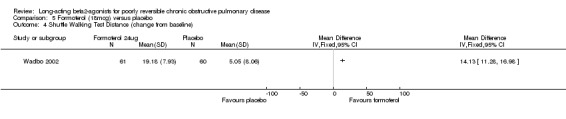

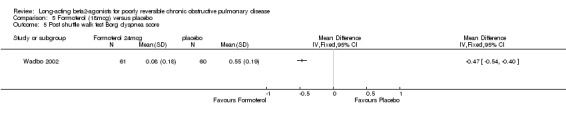

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

Wadbo 2002 reported change in shuttle walking distance from baseline which showed a significant increase in the formoterol group (14.13 (95% CI 11.28 to 16.98), N = 121).

Wadbo 2002 also reported post shuttle Borg scores which showed a significant improvement in favour of formoterol (‐0.47 (95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.40), N = 121).

(e) Formoterol 24 mcg versus placebo

No studies.

(3) Quality of life

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg BID versus placebo

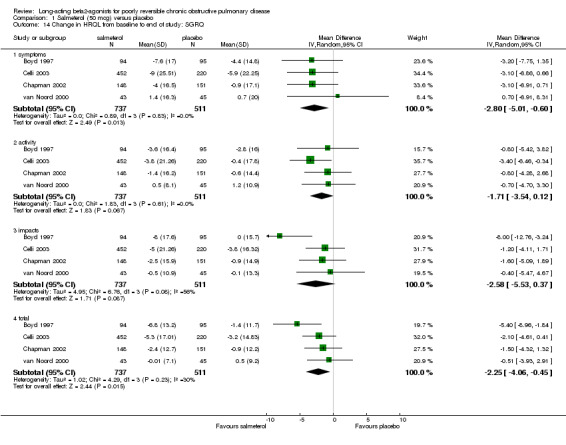

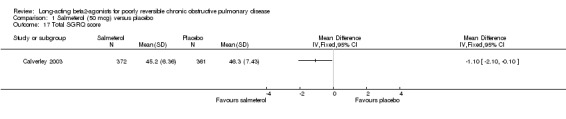

St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

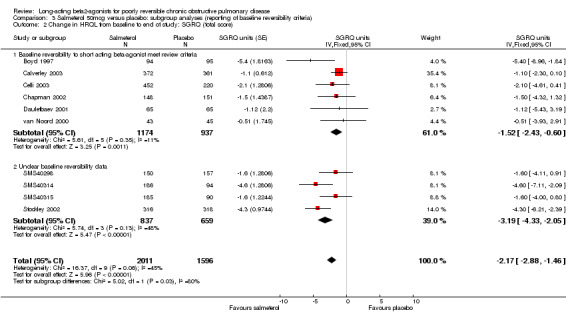

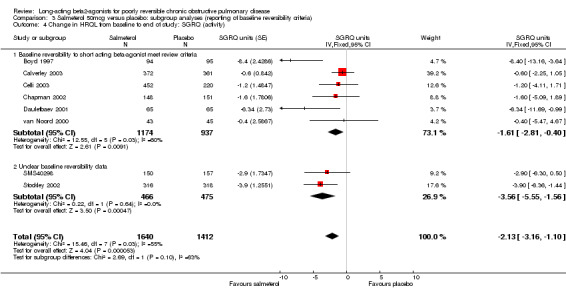

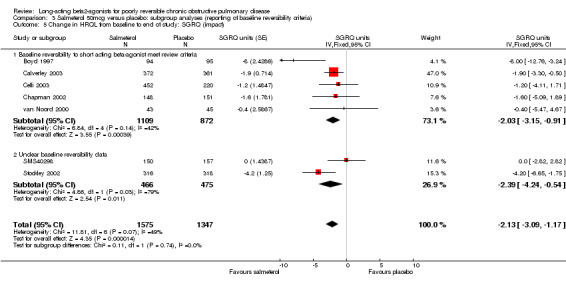

Data from published and unpublished sources were available and contribute to the pooled analyses of the SGRQ domains. We report the pooled and subgroup findings of the studies where baseline reversibility criteria meet the inclusion criteria of the review (Boyd 1997; Calverley 2003; Celli 2003; Chapman 2002; Dauletbaev 2001; van Noord 2000), and studies where baseline reversibility of the study populations was unclear (SMS40298; SMS40314; SMS40315; Stockley 2002).

Change in total SGRQ score

Overall pooled estimate: ‐2.17 units (95% CI ‐2.88 to ‐1.46), 10 studies, N = 3607 Studies where baseline reversibility meets review inclusion criteria: ‐1.52 (95% CI ‐2.43 to ‐0.6), six studies, N = 2111. Unclear baseline reversibility: ‐3.19 units (95% CI ‐4.33 to ‐2.05), four studies, N = 1496. Difference between subgroup estimates: 1.67 units (95% CI 0.2 to 3.13), P = 0.025).

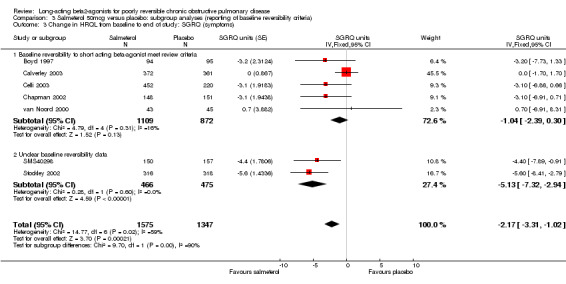

Change in symptoms domain

Overall pooled estimate: ‐2.17 (95% CI ‐3.31 to ‐1.02), seven studies, N = 2894 Subgroup of studies where baseline reversibility meets review criteria: ‐1.04 (95% CI ‐2.39 to 0.3), five studies, N = 1981. Unclear baseline reversibility: ‐5.13 (95% CI ‐7.32 to ‐2.94), two studies, N = 941. Difference between subgroup estimates: 4.09 (95% CI 1.52 to 6.66), P = 0.002

Change in activity domain

Overall pooled estimate: ‐2.13 (95% CI ‐3.16 to ‐1.10), eight studies, N = 3282 Subgroup of studies where baseline reversibility meets review criteria: ‐1.61 (95% CI ‐2.81 to ‐0.4), six studies, N = 2111 Unclear baseline reversibility: ‐3.56 (95% CI ‐5.55 to ‐1.56), two studies, N = 941 Difference between subgroup estimates: 1.95 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 4.28), P = 0.1

Change in impacts domain

Overall pooled estimate: ‐2.13 (95% CI ‐3.09 to ‐1.17), seven studies, N = 2922 Subgroup of studies where baseline reversibility meets review criteria: ‐2.03 (95% CI ‐3.15 to ‐0.91), five studies, N = 1981 Unclear baseline reversibility: ‐2.39 (95% CI ‐4.24 to ‐0.54), two studies, N = 941 Difference between subgroup estimates: 0.36 (95% CI ‐1.8 to 2.52), P = 0.74

The application of random‐effects modelling did not alter the significance of the pooled effect estimates irrespective of the presence of statistical heterogeneity.

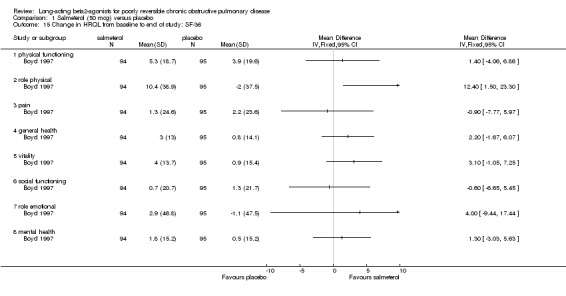

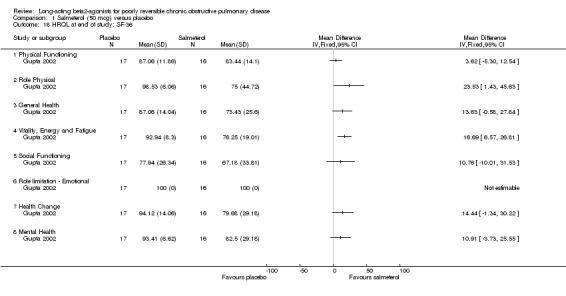

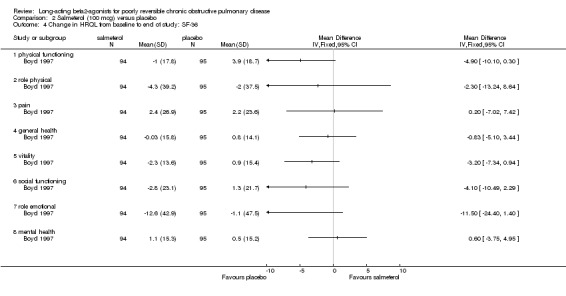

Medical Short Form 36 (SF‐36)

The SF‐36 was administered in two studies. Positive scores on the SF‐36 indicate an improvement in quality of life, and negative scores indicate deterioration. One study involving 189 participants (Boyd 1997) reported the change in SF‐36 domain scores. General health as measured by the SF‐36 showed significant improvement in only one of the eight components, Role Physical (MD 12.4 (95% CI: 1.5 to 23.3)).

One parallel group study involving 33 participants (Gupta 2002) reported end of study SF‐36 domain scores. There were significant changes in favour of salmeterol in the role ‐ physical (MD 23.53, 95% CI 1.43 to 45.63), vitality energy and fatigue (MD 16.69, 95% CI 6.57 to 26.81) domains.

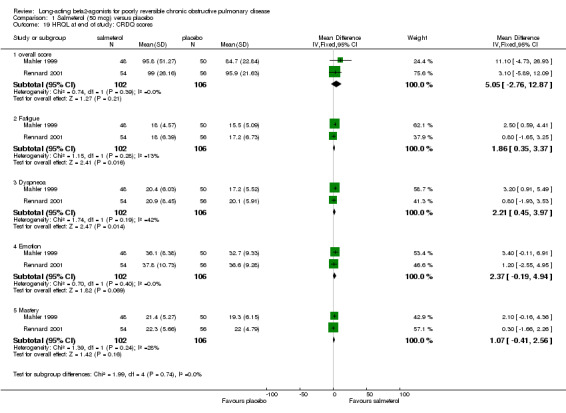

The Chronic Respiratory Diseases Questionnaire (CRDQ)

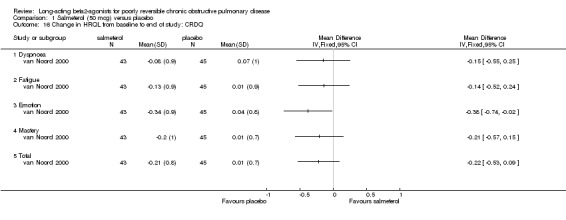

van Noord 2000; Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001

Two studies involving 208 participants reported end of study CRDQ domain scores (Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001). Significant treatment differences were demonstrated in the Fatigue (MD 1.86 (95% CI 0.35 to 3.37), I2 = 12.9%) and Dyspnoea (MD 2.21 (95% CI 0.45 to 3.97), I2 = 42.5%) domains which were not observed in the overall score (MD 5.05 (95% CI ‐2.76 to 12.87), Emotion (MD 2.37 (95% CI ‐0.19 to 4.94) and Mastery domains (MD 1.07 (95% CI ‐0.41 to 2.56), I2 = 27.8%) domains.

Mahler 1999 reported that a significantly greater proportion of participants in the salmeterol group demonstrated an increase in overall CRDQ score of 10 points, exceeding the MCD for Total score (Reidelmeier 1996) in the poorly reversible stratum of participants. This result was not confirmed by van Noord 2000.

European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EQ‐5D)

Celli 2003 reported the change in the weighted health index EQ‐5D did not reach statistical significance between salmeterol and placebo. Data were not presented in the publication, and have not been forthcoming from the study investigators.

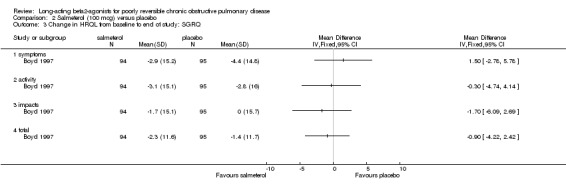

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

None of the SGRQ or SF‐36 scores improved significantly on salmeterol 100 mcg (Boyd 1997).

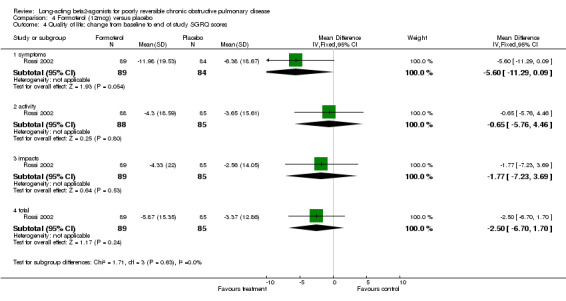

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg versus placebo

St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

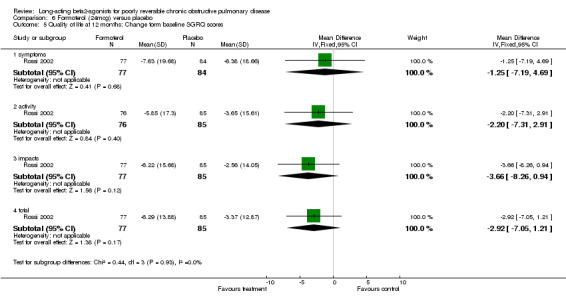

One parallel group study involving 173 participants reported mean change in SGRQ scores and reported no significant changes in any of the four domains (symptoms, activity, impacts, totals) (Rossi 2002).

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

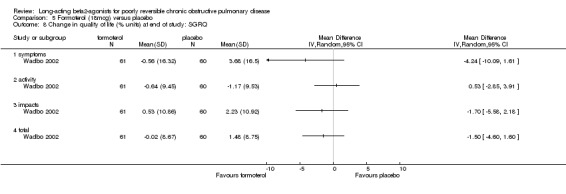

One parallel group study involving 121 participants (Wadbo 2002) reported mean SGRQ scores change from baseline and found no significant changes between formoterol and placebo in symptoms, impacts, activity and total SGRQ scores.

(e) Formoterol 24 mcg versus placebo

St Georges Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)

Rossi 2002 reported mean SGRQ scores change from baseline and found no significant changes in any of the four domains (symptoms, activity, impacts, totals).

(4) Dyspnoea and Symptom Scores

Several measures of dyspnoea were used.

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg versus placebo

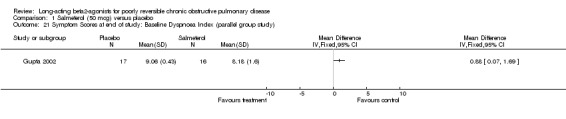

Baseline dyspnoea index (BDI) The baseline dyspnoea index was used by one parallel group study involving 33 participants which reported end of study scores (Gupta 2002). There was a significant difference in favour of salmeterol (MD 0.88 (95% CI 0.07 to 1.69).

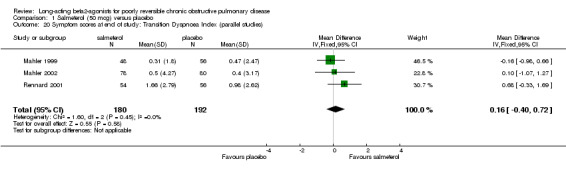

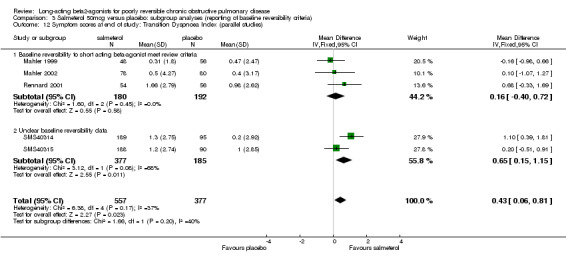

Transitional dyspnoea index (TDI)

Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001; Mahler 2002; SMS40314; SMS40315 There was no significant difference between salmeterol and placebo in the published studies where (MD 0.16 (95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.72), three studies, N = 372). Pooled analysis with two unpublished studies gave a significant difference in favour salmeterol (MD 0.43 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.81), N = 934). However, there was moderate statistical heterogeneity (I2 37.3%), and the pooled effect estimate was non‐significant with random‐effects modelling (0.41 (95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.9).

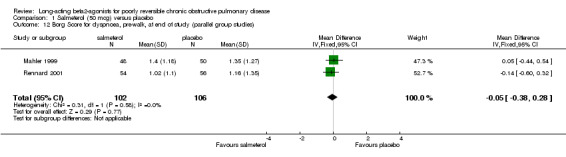

Symptom scores (pre‐walk Borg scores)

No significant difference (MD ‐0.05 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.28), N = 208.

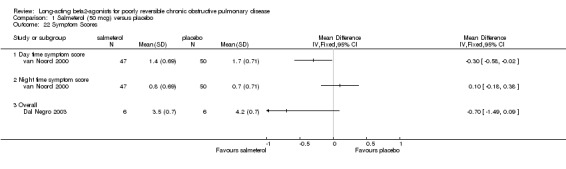

van Noord 2000 reported that mean daytime symptom scores were significantly reduced by salmeterol treatment (MD ‐0.3 (95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.02) but not mean night time scores (MD 0.10 (95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.38).

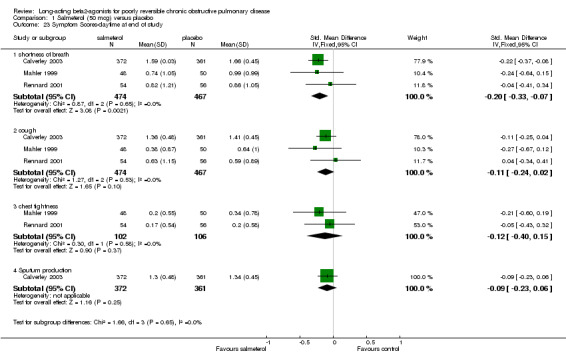

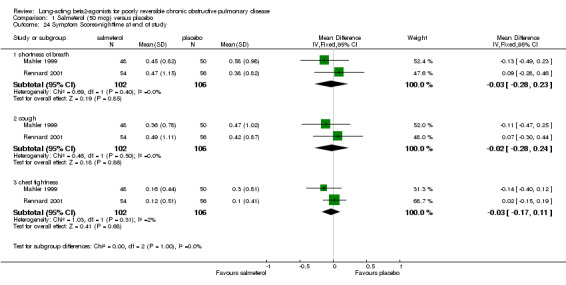

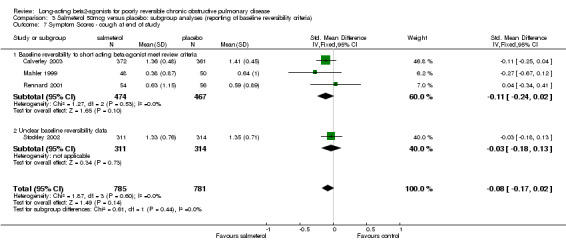

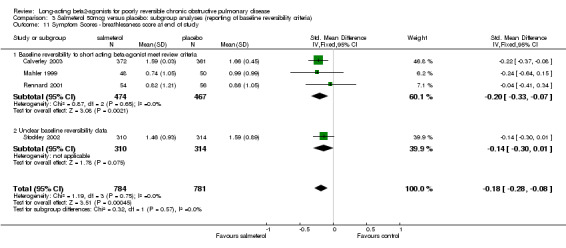

Symptom scores (shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough and sputum production)

Three published studies (Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001; Calverley 2003) and one unpublished study (Stockley 2002) reported data for one or more of these four symptom domains. With data available from Stockley 2002 there were significant differences in shortness of breath (SMD ‐0.18 (95% CI ‐0.28 to ‐0.08), but no significant difference in cough (SMD ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.02). For the remaining outcomes where only data from published studies were available, there were no significant differences in either chest tightness (SMD ‐0.12 (95% CI ‐0.40 to 0.15) and sputum production (SMD (‐0.09, 95% CI:‐0.23, 0.06).

Night symptoms

Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001 No significant differences in dyspnoea (MD ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.23), cough (MD ‐0.02 (95% CI ‐0.28 to 0.24) and chest tightness (MD ‐0.03 (95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.11). Dal Negro 2003 reported overall symptoms scores which was not statistically significant [MD ‐0.70, 95% CI ‐1.49 to 0.09].

Boyd 1997 reported statistically significant differences in favour of salmeterol in median day and night time symptom scores. Chapman 2002 reported no significant difference between salmeterol and placebo for median daytime and night‐time symptom scores. Median day and night time symptom scores were reported to be significantly lower in the salmeterol treatment period compared to the placebo period in a crossover study (Ulrik 1995).

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

Boyd 1997 reported no significant difference in the number of participants with lower Borg breathlessness scores between salmeterol and placebo (Peto OR 1.18 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.77)). This study reported statistically significant differences in favour of salmeterol in median day and night time symptom scores.

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg versus placebo

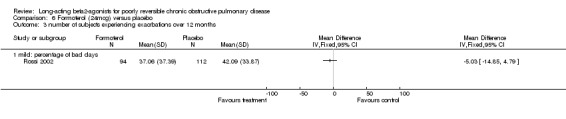

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in median symptom scores between treatment groups.

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

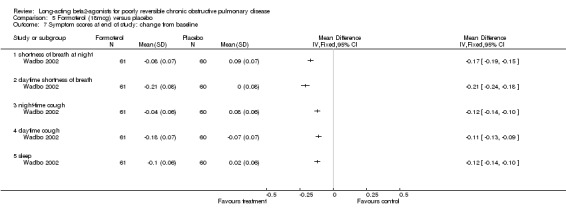

Wadbo 2002 reported a significant reduction in favour of formoterol in shortness of breath at night (MD ‐0.17 (95% CI ‐0.19 to ‐0.15), daytime shortness of breath (MD ‐0.21 (95% CI ‐0.24 to ‐0.18), night‐time cough (MD ‐0.12 (95% CI ‐0.14 to ‐0.10), daytime cough (MD ‐ 0.11 (95% CI ‐0.13 to ‐0.09) and sleep (MD ‐0.12 (‐0.14 to ‐0.10).

(e) Formoterol 24 mcg versus placebo

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in median symptom scores between treatment groups.

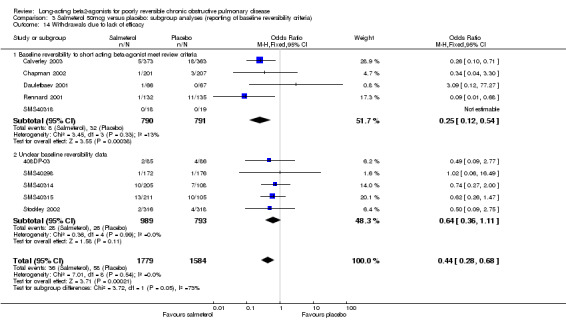

(5) Exacerbations and withdrawal due to lack of efficacy

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg versus placebo

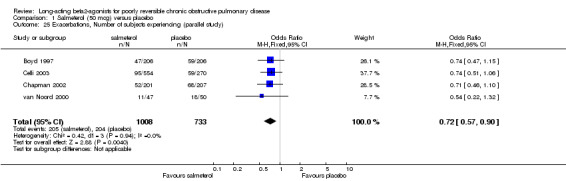

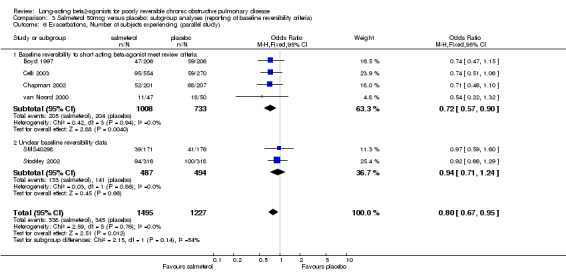

Number of participants experiencing exacerbations (parallel study)

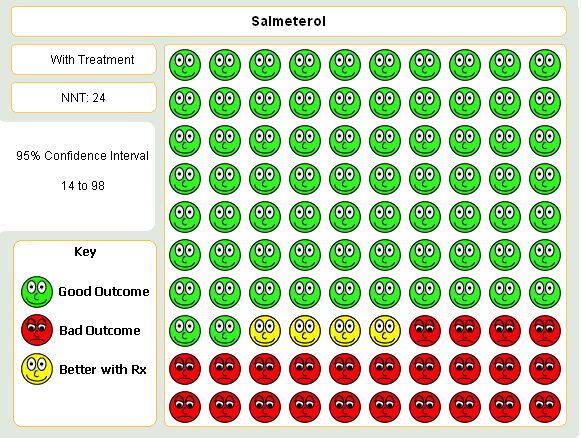

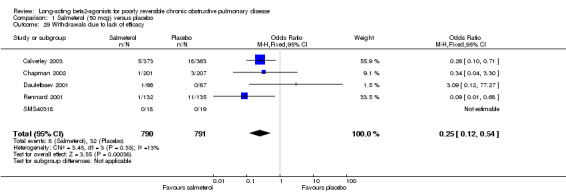

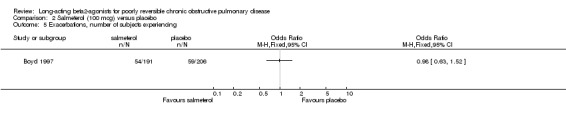

Boyd 1997; van Noord 2000; Chapman 2002; Celli 2003; Stockley 2002; SMS40298 The odds of experiencing an exacerbation were significantly reduced with salmeterol compared with placebo (OR 0.72 (95% CI 0.57 to 0.90, N = 1741). Including data from unpublished studies also gave a significant result (0.8 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.95). Assuming a baseline risk of around 28%, this gave a NNTB of 24 (95% CI 14 to 98, see Figure 4).

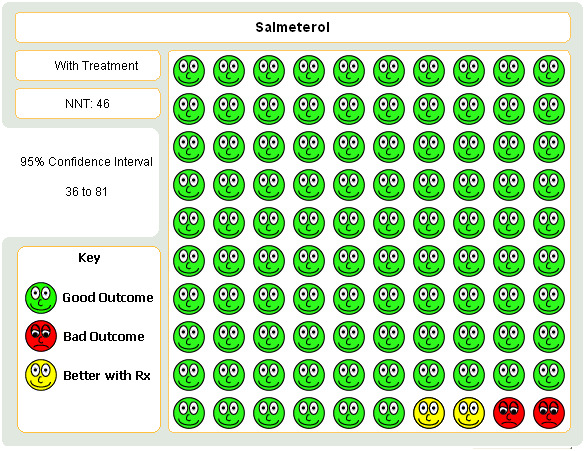

4.

Graphic to demonstrate that 24 people with COPD would need to be treated with salmeterol 50mcg BID in order to prevent one exacerbation in the short term.

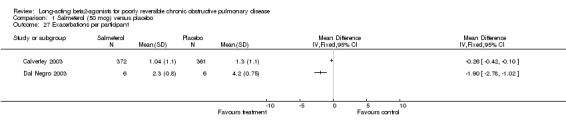

Two parallel group studies (Calverley 2003; Dal Negro 2003) reported the mean number of exacerbations per year. Whilst both studies reported significant differences in favour of salmeterol there was a high level of statistical heterogeneity (I square 92.3%). This may reflect a more homogenous, but selected group of patients in Dal Negro 2003.

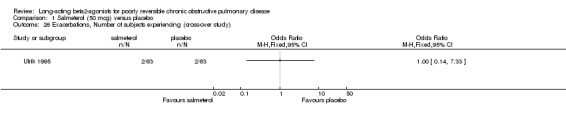

Number of participants experiencing exacerbations (crossover study)

Ulrik 1995 demonstrated no significant differences between treatment groups in the number of participants experiencing exacerbations while on treatment (OR 1.0 (95% CI: 0.14 to 7.33).

Study withdrawal due to lack of efficacy

There was a significant reduction in withdrawal due to lack of efficacy in participants treated with salmeterol (Peto OR 0.29 (95% CI 0.15 to 0.54, five studies, N = 1581)). When data from studies with unclear reversibility criteria were included, the effect remained significant (OR 0.44 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.68), N = 3363). Assuming a baseline risk of around 4%, this gives a NNTB of 46 (95 % CI 36 to 81, see Figure 5).

5.

Graphic to demonstrate that 46 people with COPD would need to be treated with salmeterol 50mcg BID in order to prevent one withdrawal due to lack of efficacy.

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

Boyd 1997 reported no significant difference in the odds of exacerbations between salmeterol and placebo (Peto OR 0.98 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.52).

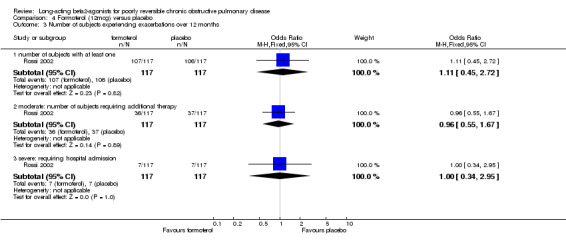

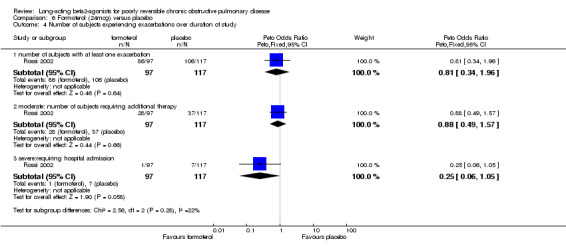

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg versus placebo

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in the odds of exacerbations between formoterol placebo.

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

No studies

(e) Formoterol 24 mcg versus placebo

Rossi 2002 reported no significant difference in the odds of exacerbations between formoterol placebo.

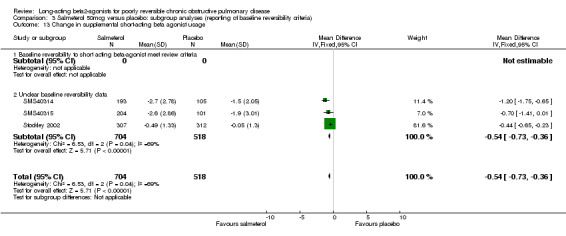

(6) Rescue medication use

(a) Salmeterol 50 mcg versus Placebo

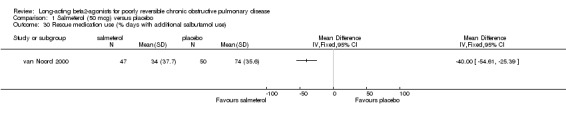

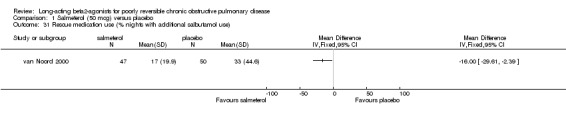

Percentage of days and nights with additional salbutamol use van Noord 2000 reported a significantly lower percentage of days and nights with additional salbutamol use in favour of salmeterol (MD ‐40.0% (95% CI ‐54.61 to ‐25.39) and (MD ‐16.0% (95% CI ‐29.61 to ‐2.39) respectively).

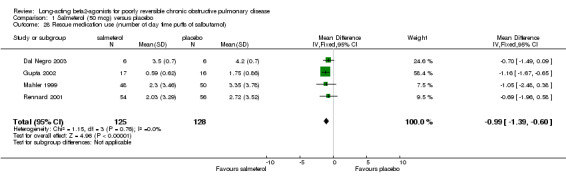

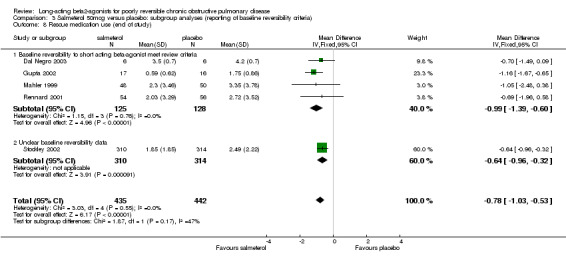

Number of daytime puffs of salbutamol (Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001, Gupta 2002, Dal Negro 2003; Stockley 2002) There was a significant difference in favour of salmeterol in the mean number of daytime puffs of short‐acting beta agonist (MD ‐0.78 (95% CI ‐1.03 to ‐0.53), N = 877). This finding was not affected by the inclusion of data from a study with unclear baseline reversibility (Stockley 2002).

Other One study reported a significant increase in the number of nights without short‐acting beta agonist use in favour of salmeterol (Ulrik 1995). Boyd 1997 reported that median daytime salbutamol use was significantly lower in salmeterol treated participants compared with placebo (P < 0.001) and that the median percentage reduction in rescue medication use favoured salmeterol (P = 0.014). Chapman 2002 did not find a significant difference between salmeterol and placebo in the use of rescue salbutamol.

(b) Salmeterol 100 mcg versus placebo

Boyd 1997 reported that median daytime salbutamol 100 mcg use was significantly lower in salmeterol treated participants compared with placebo (P < 0.001), and that the night‐time percentage reduction in salbutamol use in salmeterol treated participants was significantly lower than in placebo treated participants (P = 0.005).

(c) Formoterol 12 mcg & 24 mcg versus placebo

Rossi 2002 reported median rescue salbutamol use per day and median number of days without rescue salbutamol over the whole treatment period for both formoterol 12 mcg and 24 mcg doses. As this study included participants with both reversible and irreversible COPD and the results for this outcome was not stratified by reversibility it is not possible to include the relevant results in this review.

(d) Formoterol 18 mcg versus placebo

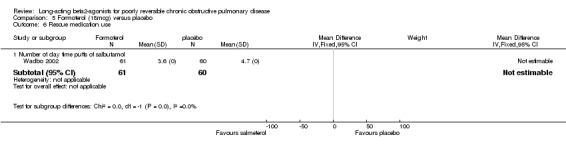

Wadbo 2002 reported that mean rescue short‐acting beta agonist use in the formoterol group was 3.6 daily inhalations compared with 4.7 daily inhalations in the placebo group in the last two months of treatment. No statistical tests of significance were applied as there was variation in the type of short‐acting beta agonist used and the data were not dose‐adjusted.

Discussion

This review aimed to determine the effectiveness of LABAs in COPD patients who demonstrate poor reversibility to short‐acting bronchodilators. The presence of increased resistance to airflow from airways obstruction is a characteristic of COPD. Although effective as an additive agent in asthma (Ni Chroinin 2005), salmeterol and formoterol are frequently advocated in the treatment of patients with COPD, where the acute response to bronchodilators in COPD is often minimal.

Respiratory Function

This review found statistically significant changes in favour of salmeterol for some lung function outcomes (change in FEV1, change in FEV1 (% predicted), change in PEF and end of study morning PEF). The clinical meaning of these differences, and their relationship with other variables such as quality of life and exacerbations, are yet to be established. The discrepancy between change and end of treatment FEV1 outcomes may be explained by the natural adjustment of imbalance between groups at baseline with change scores, and the superior statistical power derived from the larger number of studies (2026 versus 1468 participants). The effect of long‐acting beta‐agonists in COPD patients who have a reversible component for their airways disease to short acting beta agonists is outside the scope of this review. However, this review included studies with both groups of participants that were stratified by reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist. This included the Mahler 1999; Rennard 2001; Mahler 2002; Rossi 2002 and Hanania 2003 trials. These studies reported greater improvement in lung function in the subgroup with reversibility to short acting beta agonist versus the subgroup with poor reversibility.

The treatment period in the crossover studies should be of sufficient duration to detect improvements, but none were observed. The absence of demonstrable effect in these studies may be due to small sample sizes, which have less power to detect change.

In advanced COPD, exertional dyspnoea has been correlated with the level of dynamic lung hyperinflation (DH) (O'Donnell 1997). One study has demonstrated that Inspiratory Capacity (IC) correlates better with improvements in exercise tolerance and reduces dyspnoea than expiratory flow measurements (O'Donnell 1999). The improvements in IC and exercise tolerance (after ipratropium treatment) occurred in a proportion of participants (31%) who showed little or no improvement in FEV1 (< 10% predicted). Utilisation of FEV1 measurements in the studies in this review may therefore have underestimated the potential benefits of LABA therapy. However, the lack of improvement in exercise tolerance suggests this is not the case.

Exercise Tolerance, HRQoL and Symptom scores

Traditionally the efficacy of bronchodilator medication has been assessed in terms of changes in airflow obstruction using spirometry and peak flow measures. However, exercise tolerance, HRQL and symptom scores are important outcomes for people with COPD, and areas where one would hope to see significant improvements with LABAs. This review showed inconsistent effects of LABA across the reported outcomes.

The SGRQ was designed to allow direct comparisons of the health gain obtainable with therapies in asthma and COPD (Jones 1992). Being a disease specific HRQL instrument it is sensitive to treatment related improvements. The size of the treatment effects for change in total, activity and impact domains were small and the level of improvement did not exceed the four unit difference as a threshold for clinical significance in total SGRQ or its components (Jones 1991). Deselecting Boyd 1997 reduced the level of statistical heterogeneity indicating that a higher compliance rate with medication in this study or a more reversible group of participants, may have led to better outcomes with salmeterol. This study showed clinically significant improvements for the SGRQ total score and the impacts domain for the salmeterol 50 mcg group but not for the 100 mcg group suggesting that adverse effects participants experience at the higher dose may outweigh the benefits. Following the addition of new data, random‐effects modelling did not alter the direction of summary estimates in the domains of the SGRQ. The difference between subgroups when defined by the availability of reversibility criteria ('known to meet the review criteria' versus 'unclear') were significant according to the t test. However, the within subgroup I2 statistic for total SGRQ score was indicative of a heterogeneous subgroup of studies. Due to the unclear baseline reversibility thresholds, the influence of possible 'reversible' participants on the findings could vary between the unpublished studies.

The Chronic Respiratory Diseases Questionnaire (CRDQ) is a HRQL instrument COPD that measures both physical and emotional attributes. It is a seven point scale where a change of 0.5 units represents a clinically small change, 1.0 represents a moderate change and 1.5 represents a large change. A statistically significant and clinically large change in the fatigue and dyspnoea domains was detected in the salmeterol 50 mcg group. The reason behind the large statistical heterogeneity in the dyspnoea group is unclear.

The SF‐36 questionnaire is a generic HRQL instrument that assesses eight domains. The two studies investigating salmeterol 50 mcg presented SF‐36 scores differently, thus limiting opportunities for meta‐analysis. In general, the SF‐36 was unable to detect improvements in quality of life after salmeterol treatment, except in a few domains. Boyd 1997, which detected a clinically significant difference in the total SGRQ score for the salmeterol 50 mcg group, did not detect a difference in the SF‐36 questionnaire with the exception of the role physical domain. However, the SF‐36 may lack the disease specific sensitivity to detect changes in a population with COPD. Gupta 2002 reported that baseline scores for the placebo group tended to be higher than for the salmeterol group and improvement was shown in both the placebo and salmeterol groups. Given the treatment group had a lower baseline score, the improvement may have been heightened.

Exacerbations and withdrawal due to lack of efficacy

A reduction in exacerbations of COPD is one of the aims of all maintenance therapy (NICE/BTS 2004). Importantly, this review has demonstrated that the number of participants experiencing exacerbations was reduced with salmeterol 50 mcg treatment compared to placebo treatment (NNTB 21). This finding may be of significance given the relationship between exacerbations and deterioration in health related quality of life in COPD (Spencer 2004). The duration of treatment in these studies ranged from 12 to 52 weeks. This effect supports the finding on withdrawal due to lack of efficacy, although the NNTB was suggestive of a lower impact (NNTB 46). This may reflect differing surrogates of disease control and perception of benefit, but remains an important feature of clinical trial design in this population. Rossi 2002 (12 months duration) found no significant differences for exacerbation rates for formoterol 12 mcg and 24 mcg versus placebo. More trials with longer study duration are probably necessary to detect a change in exacerbation rate and the TORCH study, a three year study due for publication in 2006 will add important evidence regarding exacerbations and mortality.

Rescue short‐acting beta‐agonist use

There was a small but statistically significant reduction in number of daytime puffs of salbutamol in the salmeterol 50 mcg group compared with placebo. This is a predictable outcome given the long duration of action of these drugs which may improve medication compliance and reduce patient burden. Rescue medication use in the formoterol 18 mcg study (Wadbo 2002) showed the placebo group had one additional daily inhalation over the placebo group.

The quality of the evidence

The majority of studies were of good quality and included multi‐centre, multinational trials with varying numbers of participants. The search strategy was rigorous and included American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society abstracts. Authors and drug companies involved in trials were contacted in order to obtain any missing or unpublished data.

Limitations of the review

Meta‐analysis for a number of outcomes were limited. Several factors contributed to this problem: The small number of RCTs available meeting the criteria for inclusion in the review; inconsistent methods of reporting outcomes across studies; lack of provision of numerical data for outcome measures or standard deviations for mean effect sizes were not available. Imputation based on an average standard deviation is one possible countermeasure to censored reporting of data in clinical trials, but we were only able to undertake this in a limited number of outcomes (Table 1).

Publication bias is a known threat to the validity of any pooled estimate of efficacy (Sterne 2001) and we have identified a number of unpublished studies which are analysed in addition to the primary analyses on the published studies. Given the specific nature of COPD we analyse in this review, these studies may not have been conducted according to our entry criteria. However, their availability has enabled to us to assess whether the lack of a description of entry criteria could explain a response differential. The extent to which this was the case varied between the outcomes, and may in part reflect the different primary outcomes they selected, as well as indicating the mixed patient population hitherto excluded from this review.

There was variation in the duration of each of the studies and this may have had some effect on the results. We pooled studies of differing durations of exposure to treatment provided the treatment period was at least four weeks as it was felt that the treatment effect would be evident after four weeks of treatment. However, sensitivity analysis based on study duration was not required for most outcomes as indicated by the low I2 values where meta‐analysis was possible. Study duration did not resolve the heterogeneity for outcomes with I2 values greater than 20%.

Individual trials had different requirements for what additional medications were permitted for the participants to use. Some studies allowed patients to continue their non‐long acting beta‐agonist regular medication if maintained at a constant dose throughout (Grove 1996; Mahler 1999; Chapman 2002; Mahler 2002; Rossi 2002; Stockley 2002; Wadbo 2002; Celli 2003; Dal Negro 2003; 408DP‐03) permitted participants to continue with theophylline. This is important because the patient may have been taking additional drugs with similar mechanisms of action, the drugs may have additive or synergistic effects, or the benefits conferred by them may have underpowered the studies to find significant effects between long‐acting beta‐agonist.

We have not collected data on adverse events in this review. It was felt between the authors that the side‐effects associated with salmeterol may be affected by bronchodilation such that in a trial setting non‐responders may take an extra puff or two of study drugs to achieve some bronchodilation thus potentially increasing in systemic effects. Given that we have only been able to collect data for a subset of poorly reversible participants from many of the studies. This issue remains unclear.

The relevance of the evidence

This systematic review may differ slightly from other more recent COPD maintenance therapy reviews in that it was only concerned with those patients who have poor reversibility to short‐acting bronchodilators (Nannini 2004; Barr 2005). Recent consensus statements and guidelines have moved away from defining COPD in terms of bronchodilator response, and instead promote symptom history over spirometric findings in the definition and diagnosis of COPD. Airways obstruction is instead described as being not fully reversible (GOLD 2001; ATS/ERS 2004; NICE/BTS 2004). The findings of this review may not therefore apply directly to recent 'guideline' defined COPD. Although the validity of the reversible/non‐reversible dichotomy has been called in to question (Calverley 2003b), the progressive nature of the disease, and the mechanism of beta‐agonists justify selecting out those patients in whom these drugs are recommended, but whose initial response to beta‐agonist does not suggest that lung function will improve. The response of such people to maintenance beta‐agonist therapy has been explored in only a subset of trials. We defined poorly reversible COPD as an increase in FEV1 of < 200ml and < 15% of the baseline or percent predicted FEV1 after a short acting beta agonist. Studies in which the definition of reversibility were unclear were identified for sensitivity analysis, because the study population potentially includes a subset of participants who may have a larger reversible component of their disease. Whilst certain domains of the SGRQ gave more positive effects from the unclear studies (i.e. symptoms and total score), the effect on lung function, rescue bronchodilator usage, symptom scores, peak flow, and exacerbations did not reach statistical significance with data from studies applying unclear reversibility criteria.

Summary

This review has found evidence that long‐acting beta‐agonist treatment in people with poorly reversible COPD leads to statistically significant improvements in lung function, quality of life, symptom scores and significantly fewer exacerbations. The clinical relevance of these effects may be small, and should be borne in mind when deciding whether this treatment option is a viable maintenance therapy in people with COPD. Future trials are likely to recruit people with COPD defined more by symptom and smoking histories, and may therefore be less reliant on spirometry as a guide to assessing acute response to bronchodilator therapy. The role of long‐acting beta agonists in the treatment of COPD may become limited as other more potent therapies such as combination therapies show impressive effects over mono components, including salmeterol and formoterol (Nannini 2004).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The evidence considered in this review only relates to those patients with poorly reversible COPD. In these patients who are treated with salmeterol 50 mcg there is a small statistically significant improvement in lung function. In the absence of evidence as to whether this difference is meaningful, this effect is of uncertain clinical significance. There were some benefits in quality of life measures and reduction in symptoms. Exacerbations and rescue salbutamol use were both reduced following treatment with salmeterol 50 mcg for at least four weeks. People who suffer frequent deterioration in symptoms prompting additional medication usage could benefit from this therapy. The strength of evidence for the use of salmeterol 100 mcg, formoterol 12 mcg, 18 mcg, 24 mcg was insufficient to provide clear guidance for practice. Clinicians should consider the trade‐offs between the possibly small clinical benefit of long‐acting beta‐agonists versus the side effect profile and financial cost for the individual patient.

Implications for research.

Longer term studies than those in this systematic review (for example TORCH) are needed to assess more fully the effect on exacerbations and health care utilisation, before more definite conclusions can be drawn. In addition to measures of symptoms, studies should include a measure of exercise tolerance and HRQL with perhaps less emphasis on FEV1 given emerging evidence. Cost‐benefit analysis is also an important outcome. Further studies are needed to clarify whether the positive responses observed (improved health status and reduced breathlessness) with LABA therapy are related to FEV1 reversibility status of participants/inclusion of asthmatics in these studies. This will require the incorporation of measurements of lung hyperinflation in spirometric assessments.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 21 November 2012 | Review declared as stable | This review is no longer being updated. A new review on LABA for COPD is being prepared (for protocol see Karner 2012). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1999 Review first published: Issue 1, 2000

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 23 March 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Addition of 18 published and unpublished studies. Whilst all of these studies contributed data, the reversibility criteria for some of the unpublished studies was unclear. They were therefore included as a subgroup analysis. The new studies are: 408DP‐03; Calverly 2003; Celli 2003; Chapman 2002; Dal Negro 2003; Dauletbaev 2001; Gupta 2002; Hanania 2003; Mahler 2002; Rennard 2001; Rossi 2002; SCO40030; SMS40298; SMS40314; SMS40315; SMS40318; Stockley 2002; Wadbo 2002 Changes to the review. The confidence intervals for change in FEV1 tightened; changes in health related quality of life measurements show significant differences in favour of salmeterol; there is now evidence that salmeterol reduces the odds of an exacerbation of COPD (NNT 21). |

| 31 August 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The updated review Quality of life data from Jones et al available now as change scores Review updated with four studies added to the review (Goodwin 1997; Mahler 1999; van Noord 2000; R‐van Molken 1999). Pooling of studies possible for some outcomes. SMD analysis of FEV1 outcome. |

Notes

This review is no longer being updated. A new review on LABA for COPD is being prepared (for protocol see Karner 2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elizabeth Arnold, Veronica Stewart, Bettina Reuben, Karen Blackhall, Steve Milan, and Anna Bara for her help and assistance with data extraction, and Paul Jones and Peter Gibson, for advice. We would also like to thank Dr. Alison Grove, Dr Gerry Hagan and GSK who responded to our enquiries and requests for data.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Archive of previous methods for assessing study quality

Allocation concealment: Grade A: adequate Grade B: uncertain Grade C: clearly inadequate

Five point Jadad 1996: 1. The study was described as randomised (yes: 1, no: 0) 2. The method of randomisation was described and was appropriate (yes: 1, no: ‐1) 3. The study was described as double blind (yes: 1, no: 0) 4. The method of blinding was described and was appropriate (yes: 1, no: ‐1) 5. There was a description of withdrawals and drop outs (yes: 1, no: 0)

Appendix 2. Randomsiation procedures for GSK‐sponsored studies

The procedures for randomising GSK sponsored studies has been detailed in correspondence between Richard Follows and TL, the details of which are given below:

The randomisation software is a computer‐generated, centralised programme (RandAll). After verification that the randomisation sequence is suitable for the study design (crossover, block or stratification), Clinical Supplies then package the treatments according the randomisation list generated. Concealment of allocation is maintained by a third party, since the sites phone in and are allocated treatments on that basis. Alternatively a third party may dispense the drug at the sites. Unblinding of data for interim analyses can only be done through RandAll, and are restricted so that only those reviewing the data are unblinded to treatment group allocation.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study (parallel study) | 8 | 2026 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 51.00 [31.93, 70.07] |

| 1.1 FEV1 Reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist < 15 (% baseline) | 6 | 933 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 49.63 [17.45, 81.82] |

| 1.2 FEV1 Reversiblity to short‐acting beta‐agonist < 15 (% predicted normal) | 2 | 1093 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 51.73 [28.06, 75.41] |

| 2 Change in FEV1 (% predicted) from baseline to end of study (parallel study) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Pre‐bronchodilator FEV1(L) at end of study (parallel group studies) | 5 | 1468 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.18, 0.09] |

| 3.1 FEV1 Reversibility to short‐acting beta‐agonist < 15 (% baseline) | 3 | 241 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.10 [‐0.23, 0.02] |

| 3.2 FEV1 Reversibility to short‐acting beta‐agonist < 15 (% predicted normal) | 1 | 733 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.06 [0.04, 0.08] |

| 3.3 Unclear reversibility | 1 | 494 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 FEV1 at end of study (crossover studies) | 2 | 158 | Litres (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.04, 0.04] |

| 5 PEF at end of study (crossover study) | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5.1 Morning PEF | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5.2 Evening PEF | 1 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 6 PEF (L/min) at end of study (parallel study) | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Morning PEF | 3 | 842 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.89 [10.86, 18.91] |

| 6.2 Evening PEF | 1 | 97 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 18.0 [‐11.13, 47.13] |

| 7 Change in am PEF (parallel studies) | 2 | 540 | L/min (Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.36 [2.88, 13.85] |

| 8 Change in am PEF (L/min ‐ parallel studies) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 9 Six minute walk test, mean change (m) from baseline to end of study (crossover study) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 10 Six minute walk test, distance (m) at end of study (parallel group studies) | 4 | 659 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.58 [‐10.73, 13.88] |

| 11 Six minute walk, Borg score (<3) for breathlessness at end of study (parallel study) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 12 Borg Score for dyspnoea, pre‐walk, at end of study (parallel group studies) | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.38, 0.28] |

| 13 Borg Score for dyspnoea, post‐walk, at end of study (parallel group studies) | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.16 [‐0.59, 0.27] |

| 14 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 14.1 symptoms | 4 | 1248 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.80 [‐5.01, ‐0.60] |

| 14.2 activity | 4 | 1248 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐1.71 [‐3.54, 0.12] |

| 14.3 impacts | 4 | 1248 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.58 [‐5.53, 0.37] |

| 14.4 total | 4 | 1248 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐2.25 [‐4.06, ‐0.45] |

| 15 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SF‐36 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 15.1 physical functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.2 role physical | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.3 pain | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.4 general health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.5 vitality | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.6 social functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.7 role emotional | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 15.8 mental health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 16 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: CRDQ | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 16.1 Dyspnoea | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 16.2 Fatigue | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 16.3 Emotion | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 16.4 Mastery | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 16.5 Total | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 17 Total SGRQ score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 18 HRQL at end of study: SF‐36 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 18.1 Physical Functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.2 Role Physical | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.3 General Health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.4 Vitality, Energy and Fatigue | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.5 Social Functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.6 Role limitation ‐ Emotional | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.7 Health Change | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 18.8 Mental Health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 19 HRQL at end of study: CRDQ scores | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 19.1 overall score | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.05 [‐2.76, 12.87] |

| 19.2 Fatigue | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.86 [0.35, 3.37] |

| 19.3 Dyspneoa | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.21 [0.45, 3.97] |

| 19.4 Emotion | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.37 [‐0.19, 4.94] |

| 19.5 Mastery | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [‐0.41, 2.56] |

| 20 Symptom scores at end of study: Transition Dyspnoea Index (parallel studies) | 3 | 372 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [‐0.40, 0.72] |

| 21 Symptom Scores at end of study: Baseline Dyspnoea Index (parallel group study) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 22 Symptom Scores | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 22.1 Day time symptom score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 22.2 Night time symptom score | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 22.3 Overall | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 23 Symptom Scores‐daytime at end of study | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 23.1 shortness of breath | 3 | 941 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.20 [‐0.33, ‐0.07] |

| 23.2 cough | 3 | 941 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.24, 0.02] |

| 23.3 chest tightness | 2 | 208 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.12 [‐0.40, 0.15] |

| 23.4 Sputum production | 1 | 733 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.09 [‐0.23, 0.06] |

| 24 Symptom Scores‐nighttime at end of study | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 24.1 shortness of breath | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.28, 0.23] |

| 24.2 cough | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.02 [‐0.28, 0.24] |

| 24.3 chest tightness | 2 | 208 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.17, 0.11] |

| 25 Exacerbations, Number of subjects experiencing (parallel study) | 4 | 1741 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.57, 0.90] |

| 26 Exacerbations, Number of subjects experiencing (cross‐over study) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 27 Exacerbations per participant | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 28 Rescue medication use (number of day time puffs of salbutamol) | 4 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.99 [‐1.39, ‐0.60] |

| 29 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy | 5 | 1581 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.12, 0.54] |

| 30 Rescue medication use (% days with additional salbutamol use) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 31 Rescue medication use (% nights with additional salbutamol use) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study (parallel study).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Change in FEV1 (% predicted) from baseline to end of study (parallel study).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Pre‐bronchodilator FEV1(L) at end of study (parallel group studies).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 FEV1 at end of study (crossover studies).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 PEF at end of study (crossover study).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 6 PEF (L/min) at end of study (parallel study).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 7 Change in am PEF (parallel studies).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 8 Change in am PEF (L/min ‐ parallel studies).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 9 Six minute walk test, mean change (m) from baseline to end of study (crossover study).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 10 Six minute walk test, distance (m) at end of study (parallel group studies).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 11 Six minute walk, Borg score (<3) for breathlessness at end of study (parallel study).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 12 Borg Score for dyspnoea, pre‐walk, at end of study (parallel group studies).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 13 Borg Score for dyspnoea, post‐walk, at end of study (parallel group studies).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 14 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ.

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 15 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SF‐36.

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 16 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: CRDQ.

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 17 Total SGRQ score.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 18 HRQL at end of study: SF‐36.

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 19 HRQL at end of study: CRDQ scores.

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 20 Symptom scores at end of study: Transition Dyspnoea Index (parallel studies).

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 21 Symptom Scores at end of study: Baseline Dyspnoea Index (parallel group study).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 22 Symptom Scores.

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 23 Symptom Scores‐daytime at end of study.

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 24 Symptom Scores‐nighttime at end of study.

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 25 Exacerbations, Number of subjects experiencing (parallel study).

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 26 Exacerbations, Number of subjects experiencing (cross‐over study).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 27 Exacerbations per participant.

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 28 Rescue medication use (number of day time puffs of salbutamol).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 29 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 30 Rescue medication use (% days with additional salbutamol use).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Salmeterol (50 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 31 Rescue medication use (% nights with additional salbutamol use).

Comparison 2. Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in FEV1(L) from baseline to end of study (parallel study) | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Six minute walk test, Borg score (<3) for breathlessness at end of study (parallel study) | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 symptoms | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 activity | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.3 impacts | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.4 total | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SF‐36 | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4.1 physical functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.2 role physical | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.3 pain | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.4 general health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.5 vitality | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.6 social functioning | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.7 role emotional | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 4.8 mental health | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 5 Exacerbations, number of subjects experiencing | 1 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 1 Change in FEV1(L) from baseline to end of study (parallel study).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 2 Six minute walk test, Borg score (<3) for breathlessness at end of study (parallel study).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 3 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 4 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SF‐36.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Salmeterol (100 mcg) versus placebo, Outcome 5 Exacerbations, number of subjects experiencing.

Comparison 3. Salmeterol 50mcg versus placebo: subgroup analyses (reporting of baseline reversibility criteria).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Change in FEV1(mls) from baseline to end of study | 11 | 2644 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 55.13 [38.16, 72.09] |

| 1.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 8 | 2026 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 51.00 [31.93, 70.07] |

| 1.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 3 | 618 | mls (Fixed, 95% CI) | 70.77 [33.65, 107.88] |

| 2 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ (total score) | 10 | 3607 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.17 [‐2.88, ‐1.46] |

| 2.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 6 | 2111 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.52 [‐2.43, ‐0.60] |

| 2.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 4 | 1496 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.19 [‐4.33, ‐2.05] |

| 3 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ (symptoms) | 7 | 2922 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.17 [‐3.31, ‐1.02] |

| 3.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 5 | 1981 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.04 [‐2.39, 0.30] |

| 3.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 2 | 941 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.13 [‐7.32, ‐2.94] |

| 4 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ (activity) | 8 | 3052 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.13 [‐3.16, ‐1.10] |

| 4.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 6 | 2111 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.61 [‐2.81, ‐0.40] |

| 4.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 2 | 941 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐3.56 [‐5.55, ‐1.56] |

| 5 Change in HRQL from baseline to end of study: SGRQ (impact) | 7 | 2922 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.13 [‐3.09, ‐1.17] |

| 5.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 5 | 1981 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.03 [‐3.15, ‐0.91] |

| 5.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 2 | 941 | SGRQ units (Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.39 [‐4.24, ‐0.54] |

| 6 Exacerbations, Number of subjects experiencing (parallel study) | 6 | 2722 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.67, 0.95] |

| 6.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 4 | 1741 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.57, 0.90] |

| 6.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 2 | 981 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.71, 1.24] |

| 7 Symptom Scores ‐ cough at end of study | 4 | 1566 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.17, 0.02] |

| 7.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 3 | 941 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.24, 0.02] |

| 7.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 1 | 625 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.03 [‐0.18, 0.13] |

| 8 Rescue medication use (end of study) | 5 | 877 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.78 [‐1.03, ‐0.53] |

| 8.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 4 | 253 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.99 [‐1.39, ‐0.60] |

| 8.2 Unclear baseline reversibility data | 1 | 624 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.64 [‐0.96, ‐0.32] |

| 9 Morning PEF (L/min) at end of study (parallel study) | 4 | 1467 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 15.81 [11.96, 19.67] |

| 9.1 Baseline reversibility to short acting beta‐agonist meet review criteria | 3 | 842 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 14.89 [10.86, 18.91] |