Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with higher neurological levels of spinal cord injury (SCI) at or above the sixth thoracic segment (≥T6), exhibit impaired resting cardiovascular control and responses during upper-body exercise. Over time, impaired cardiovascular control predisposes individuals to lower cardiorespiratory fitness and thus a greater risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality. Non-invasive transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (TSCS) has been shown to modulate cardiovascular responses at rest in individuals with SCI, yet its effectiveness to enhance exercise performance acutely, or promote superior physiological adaptations to exercise following an intervention, in an adequately powered cohort is unknown. Therefore, this study aims to explore the efficacy of acute TSCS for restoring autonomic function at rest and during arm-crank exercise to exhaustion (AIM 1) and investigate its longer-term impact on cardiorespiratory fitness and its concomitant benefits on cardiometabolic health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes following an 8-week exercise intervention (AIM 2).

Methods and analysis

Sixteen individuals aged ≥16 years with a chronic, motor-complete SCI between the fifth cervical and sixth thoracic segments will undergo a baseline TSCS mapping session followed by an autonomic nervous system (ANS) stress test battery, with and without cardiovascular-optimised TSCS (CV-TSCS). Participants will then perform acute, single-session arm-crank exercise (ACE) trials to exhaustion with CV-TSCS or sham TSCS (SHAM-TSCS) in a randomised order. Twelve healthy, age- and sex-matched non-injured control participants will be recruited and will undergo the same ANS tests and exercise trials but without TSCS. Thereafter, the SCI cohort will be randomly assigned to an experimental (CV-TSCS+ACE) or control (SHAM-TSCS+ACE) group. All participants will perform 48 min of ACE twice per week (at workloads corresponding to 73–79% peak oxygen uptake), over a period of 8 weeks, either with (CV-TSCS) or without (SHAM-TSCS) cardiovascular-optimised stimulation. The primary outcomes are time to exhaustion (AIM 1) and cardiorespiratory fitness (AIM 2). Secondary outcomes for AIM 1 include arterial blood pressure, respiratory function, cerebral blood velocity, skeletal muscle tissue oxygenation, along with concentrations of catecholamines, brain-derived neurotrophic factor and immune cell dynamics via venous blood sampling pre, post and 90 min post-exercise. Secondary outcomes for AIM 2 include cardiometabolic health biomarkers, cardiac function, arterial stiffness, 24-hour blood pressure lability, energy expenditure, respiratory function, neural drive to respiratory muscles, seated balance and HRQoL (eg, bowel, bladder and sexual function). Outcome measures will be assessed at baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention and after a 6-week follow-up period (HRQoL questionnaires only).

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been obtained from the Wales Research Ethics Committee 7 (23/WA/0284; 03/11/2024). The recruitment process began in February 2024, with the first enrolment in July 2024. Recruitment is expected to be completed by January 2026. The results will be presented at international SCI and sport-medicine conferences and will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN17856698.

Keywords: SPORTS MEDICINE, REHABILITATION MEDICINE, Physical Therapy Modalities, Spine, Neurological injury, CARDIOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study will examine for the first time, in an adequately powered cohort, whether non-invasive transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation (TSCS) improves volitional upper-body exercise capacity in the short- and long-term.

Validated and reliable quantitative assessments will be used to explore how the application of TSCS during acute arm-crank exercise influences cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic and immune responses.

A non-injured control group will be included to determine to what extent autonomic responses at rest and during exercise are ‘normalised’ with the application of TSCS in the spinal cord injured cohort.

Validated and reliable quantitative and qualitative approaches will be used to investigate the effectiveness of long-term (8 weeks) TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise on a broad range of autonomic dysfunctions (eg, cardiovascular, urinary, gastrointestinal and sexual) as part of a pilot randomised clinical trial.

While there is a 6-week follow-up period following the exercise intervention to assess health-related quality of life, to reduce participant burden, this follow-up period will not include any physiological assessments and therefore, the degree to which participants sustain any exercise intervention-related physiological adaptations will remain unknown.

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a complex neurological condition typically caused by trauma, disease or degeneration, that results in not only sensory and motor deficits but also impairments to the autonomic nervous system (ANS), including cardiovascular, thermoregulatory, urinary, gastrointestinal, sexual and immune dysfunctions. While most research has traditionally focused on ‘curing paralysis’, that is, by regaining or improving motor function, it is only more recently that researchers have started to understand the importance of autonomic dysfunctions in individuals with SCI.1 Indeed, autonomic impairments across all of the aforementioned functions have been highlighted as key factors influencing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in the SCI population,2 therefore current research should prioritise how these autonomic dysfunctions can be improved.

Motor-complete SCI results in the loss of motor function below the level of injury and overall mobility. An increase in sedentary time3 4 and physical inactivity5 results in typically low levels of cardiorespiratory fitness (assessed as peak oxygen uptake (V̇O2peak)).6 7 As such, the SCI population is at an earlier and heightened risk for the development of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular dysfunction (eg, cognitive impairment and dementia) and type-2 diabetes mellitus, relative to non-injured individuals.8,13 Furthermore, individuals with a cervical or upper-thoracic level of injury exhibit profound haemodynamic instability14,16 often characterised by resting hypotension, subsequently increasing the risk of developing such chronic conditions.17

In individuals with higher neurological levels of SCI, cardiovascular responses during exercise are typically weakened due to a disruption between the medulla oblongata and the sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons at and below the neurological level of injury.18,20 A diminished supraspinal sympathetic drive to the heart and blood vessels can result in a reduced peak heart rate (HR), low blood pressure (BP), reduced venous return and thus stroke volume that ultimately restricts aerobic exercise performance.21,23 Without sufficient physiological stimuli during exercise, these individuals often experience minimal adaptations following long-term aerobic exercise interventions.24 While some studies have attempted to augment acute upper-body exercise performance with the use of ergogenic aids, these are either dangerous (eg, ‘boosting’ via autonomic dysreflexia (AD)25,28) or the evidence on their effectiveness is inconclusive (eg, lower-body compression,29,32 abdominal binding,33 34 pharmaceuticals or stimulants35,37).

Following a burst in research activity over the last 10 years, spinal cord stimulation (SCS) has shown potential for restoring various neurological dysfunctions following SCI.38 39 Epidural SCS (ESCS) consists of a surgically implanted electrode array in the dural space that provides direct electrical stimulation of dorsal root afferents40 which can increase motor output.41 42 Recent studies have demonstrated that ESCS can also modulate cardiovascular function (ie, by increasing or sustaining arterial BP at rest or in response to an orthostatic challenge)43,47 and can acutely augment upper-body exercise performance (26% increase in V̇O2peak).48 Transcutaneous SCS (TSCS) is a non-invasive strategy that uses electrodes placed on the epidermis. While the exact underlying mechanisms of TSCS are less clear, research has indicated it can also improve motor output.49,51 Like ESCS, work has shown that TSCS can provide beneficial effects for treating and preventing consequences of autonomic dysfunction such as resting52 and orthostatic hypotension,53 by targeting the sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons below the neurological level of injury. Furthermore, its effectiveness at restoring autonomic functions is currently being investigated in several clinical trials.54,56 A recent case-series has demonstrated that time to exhaustion can be augmented by up to 19 min longer in individuals with SCI when arm-crank exercise is paired with TSCS.52 Notably, these improvements were comparable to individuals exercising with ESCS. While these findings are novel, a further adequately powered study is required to conclude that acute exercise performance can be enhanced with TSCS.

Individuals with higher neurological levels of SCI are frequently challenged with changes in BP during activities of daily living, for example, postural changes, bed or wheelchair transfers, after eating or exercise, and changes in environmental temperature.121 57,59 Studies simulating these challenges with the use of autonomic stress tests (eg, orthostatic challenge,60,62 cold pressor test,63 HR response to deep breathing62 and Valsalva manoeuvre62) have indicated that individuals with higher neurological levels of SCI exhibit poor haemodynamic responses versus non-injured individuals with an intact sympathetic nervous system. Others have also demonstrated that heart rate variability (HRV) is altered following SCI (ie, lower sympathetic activity with higher neurological levels of injury).64,66 Given the preliminary evidence that TSCS can target sympathetic outflow,52 53 67 68 exploring whether haemodynamic responses to autonomic stress tests can be stabilised acutely with TSCS would be noteworthy. Further, whether prolonged stimulation combined with exercise (ie, following a multi-week intervention) can elicit plasticity in both the descending motor pathways and autonomic circuits of the spinal cord, and thus improve muscular function and responses to typical autonomic challenges faced by individuals with SCI, also remains unanswered.

Impaired sympathetic outflow following SCI also limits activation of the adrenal gland and spleen resulting in reduced catecholamine secretion,23 which may compromise remodelling of the immune system after bouts of exercise.69 70 In non-injured individuals, activation of the sympathetic nervous system during exercise evokes a rapid mobilisation of lymphocytes, which are subsequently redistributed towards sites of potential infection (ie, lymphoid tissues)71 72 that enhances immunity and potentially reduces the risk of common infections.73 Thus, individuals with SCI likely do not reap the same magnitude of exercise-induced immune benefits as non-injured individuals. As such, individuals with SCI are prone to immune suppression and chronic systemic inflammation, leading to more frequent infections (eg, pneumonia, urinary tract and wound infections) and risk of cardiovascular disease.74,76 A previous case-report demonstrated that ESCS caused downregulation of inflammatory pathways and upregulation of adaptive immune pathways,77 which is consistent with activation of sympathetic outflow and thus carries potential benefits for immunological health. Modulating the physiological responses to acute bouts of exercise with TSCS may therefore result in normalised immune cell mobilisation and redistribution in this specific population.

Loss of autonomic function following SCI can also result in impaired bowel, bladder and sexual functions, which adversely impacts physical and emotional HRQoL.78,81 It is therefore unsurprising that the recovery of bowel, bladder and sexual functions are among the most important areas for recovery with the use of SCS.82 Notably, recent work with ESCS83,85 and non-invasive neuromodulation techniques (eg, transcutaneous electrical nerve, magnetic and vibratory stimulation)86 have revealed promising restorations to such functions. Interestingly, activity-based therapy has been shown to improve lower urinary tract function87 and result in greater bowel control or improved defecation.88 Whether the combined application of TSCS and exercise leads to concomitant improvements to bowel, bladder and sexual functions, perhaps via the activation of other autonomic tracts,89 is currently unknown.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored the use of TSCS during acute or long-term upper-body (eg, arm-crank) exercise in the SCI population. Augmenting exercise capacity with TSCS may have important implications for supporting athletic and/or rehabilitation strategies following SCI. Furthermore, repeated exposure to TSCS may also facilitate an optimal strategy for improving cardiovascular and cardiometabolic health90,92 to offset the risk of chronic disease, and may also lead to concomitant improvements in functional outcomes that are typically impaired in individuals with SCI, such as cognition,93 94 respiratory function90 95 and trunk control.91 92 96

Trial objectives

The study will be formed of acute (AIM 1) and longitudinal (AIM 2) components. The objectives for AIM 1 are as follows:

To investigate the influence of cardiovascular-optimised TSCS (CV-TSCS) on time to exhaustion and cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic and immune responses during acute aerobic arm-crank exercise in individuals with motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic SCI, compared with non-injured controls.

To assess cardiovascular and cerebrovascular responses to a battery of ANS stress tests, with and without CV-TSCS in individuals with motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic SCI, compared with non-injured controls.

The objectives for AIM 2 are as follows:

To investigate the effects of 8 weeks of CV-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise on cardiorespiratory fitness, autonomic cardiovascular function, arterial stiffness, cardiac function, cardiometabolic health biomarkers, respiratory function and trunk stability in individuals with motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic SCI.

To assess the effects of CV-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise acutely (single session) and longitudinally (8 weeks) on corticospinal and spinal excitability of the respiratory muscles in motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic individuals with SCI.

To determine the effects of 8 weeks of CV-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise on cognitive performance and whether the intervention facilitates concomitant improvements in HRQoL, particularly pain, and bowel, bladder and/or sexual function in individuals with motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic SCI.

To evaluate the feasibility of conducting long-term CV-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise in individuals with motor-complete, cervical or upper-thoracic SCI.

Methods and analyses

Study design and setting

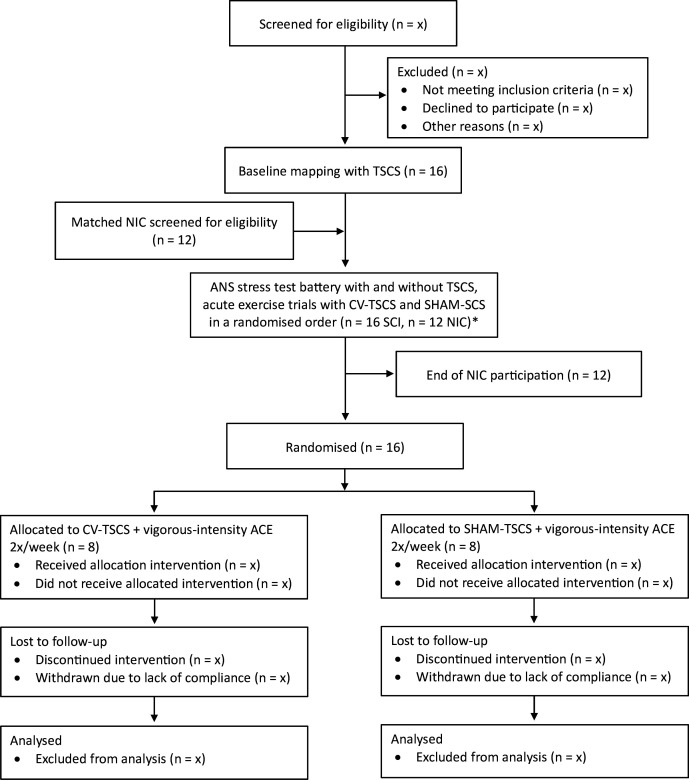

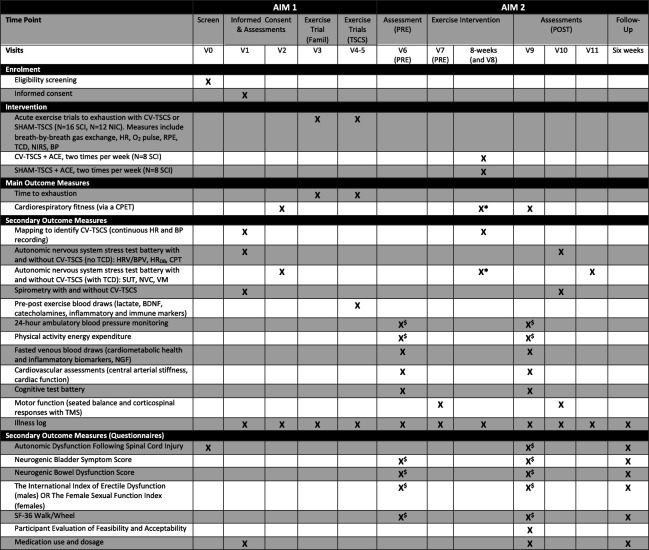

This study consists of an acute component that adopts a repeated-measures, randomised crossover trial design (AIM 1) and a longitudinal component that adopts a single-blind pilot randomised-controlled trial design (AIM 2). During AIM 1, participants will undergo a mapping session with TSCS to identify the specific stimulation parameters that optimise cardiovascular outcomes (ie, parameters that result in a gradual and controlled elevation in systolic BP). Participants will then perform a battery of autonomic function and spirometry tests with and without CV-TSCS. They will also perform three arm-crank exercise trials to exhaustion at various relative intensities, of which one trial will be a familiarisation without stimulation and two trials will be performed with CV-TSCS and sham TSCS (SHAM-TSCS) in a randomised order. During AIM 2, participants will be randomised into two study groups: (1) CV-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise (experimental group; N=8), and (2) SHAM-TSCS paired with arm-crank exercise (control group; N=8). Participants will perform two arm-crank exercise trials per week for 8 weeks. Assessments will take place at baseline (AIM 1), prior to and following the exercise intervention (AIM 2) and at a 6-week follow-up period (AIM 2; HRQoL assessments only). All study-related procedures and assessments will take place in the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Birmingham. The study received a favourable ethical opinion from the Wales Research Ethics Committee 7 (Ref: 23/WA/0284; 03 November 2024) and has been registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry (ISRCTN17856698; 08 February 2024). The recruitment process began in February 2024, with the first enrolment in July 2024. Recruitment is expected to cease by January 2026. An overview of the study is presented in figure 1 and the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials schedule of enrolment, intervention and assessments is presented in figure 2.

Figure 1. Trial flow chart. *NIC receive no stimulation. ACE, arm-crank exercise; ANS, autonomic nervous system, CV-TSCS, cardiovascular optimised transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation; NIC, non-injured controls; SCI, spinal cord injury; SHAM-TSCS, sham TSCS; TSCS, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation.

Figure 2. Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials schedule of enrolment, intervention and assessments. $Participants will perform these assessments in the days before this visit. *Participants will perform a CPET and SUT during the fourth week of the exercise intervention (Visit 8), no other autonomic nervous system stress tests will be conducted. ACE, arm-crank exercise; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BP, blood pressure; BPV, blood pressure variability; CPET, cardiopulmonary exercise test; CPT, cold pressor test; CV-TSCS, cardiovascular-optimised transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation; famil, familiarisation; HRDB, heart rate response to deep breathing; HRV, heart rate variability; NGF, nerve growth factor; NIC, non-injured controls; NVC, neurovascular coupling; NIRS, near-infrared spectroscopy (muscle tissue oxygenation); SCI, spinal cord injury; SF-36, Short-Form-36; SHAM-TSCS, sham transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation; SUT, sit-up test; RPE, rating of perceived exertion; TCD, transcranial Doppler; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; TSCS, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation; VM, Valsalva manoeuvre.

Patient and public involvement

While individuals with SCI were not directly involved in the original design and conception of the protocol, three individuals with SCI (C7-T4; American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) A) were asked to provide their opinions on the length of the intervention, whether the number of outcome assessments would be burdensome, and whether they agreed with the exercise paired with TSCS rationale for supporting health benefits. It was determined that further physiological assessments at the 6-week follow-up could be burdensome on participants, but an extensive HRQoL questionnaire battery, which can be collected remotely, should capture any sustained self-reported effects. Future studies could look to build on our findings by including physiological assessments at a follow-up time point. The terminology in the HRQoL questionnaire battery was also discussed with these individuals, with the general consensus being that there is likely to be minimal distress caused by answering such questions. This is important as individuals with SCI are frequently exposed to being asked questions regarding their pain and bowel, bladder and sexual function by clinical care teams and peers. Several other individuals with SCI provided their thoughts on the participant information sheet and recruitment material to make them end-user friendly. We would like to emphasise that a recent survey found that 91% of responders (N=223) would follow a neuromodulation training/rehabilitation protocol in this field,82 and that more individuals would be interested in receiving TSCS (80%) in comparison to ESCS (61%), thus demonstrating that a protocol of this design would likely be well received by the SCI community. The recruited cohort will be involved in developing our understanding of the feasibility of delivering such a trial in this population. We will actively engage with SCI support networks to disseminate study findings.

Sample size

We aim to recruit 16 participants with SCI. Given the lack of studies in the SCI literature reporting time to exhaustion as a performance outcome, and none with the use of an ergogenic aid, our sample size is based on the effect size drawn from a randomised-crossover study investigating the use of an anti-gravity suit as an ergogenic aid to generate lower-body positive pressure, assist venous return and augment V̇O2peak in individuals with SCI.31 This study reported a greater V̇O2peak with the anti-gravity suit compared to without (with: 15.7±2.4 mL/kg/min, without: 12.5±2.0 mL/kg/min), with a large effect size (Cohen’s d=1.45). This augmented aerobic capacity is likely underpinned by the significantly greater stroke volume and mean arterial BP observed when individuals wore the suit and parallels the hypothesis in the proposed project regarding the use of CV-TSCS for modulating BP and subsequently improving exercise performance. At the time of designing this trial there were no studies available that had tested the impact of TSCS on exercise performance. While a single case-report has demonstrated a greater V̇O2peak with ESCS compared to without (with: 11.8 mL/kg/min, without: 9.4 mL/kg/min),48 an N-of-1 trial does not permit a meaningful power calculation. Our a priori power calculation, with 95% power and 1% level of significance, indicates that a sample size of 12 individuals with SCI is sufficient to detect a significant change in our primary outcome measure (time to exhaustion) during the acute application of TSCS (AIM 1) (G*Power V.3.1.9.6, Heinrich Heine Universität Düsseldorf, Germany). Presently, there are no long-term TSCS and exercise intervention studies that have included outcomes that are consistent with those proposed in this protocol to facilitate a meaningful power calculation for the intervention component of this trial. To account for potential attrition with the 8-week intervention and follow-up in this proposal, a conservative 33% dropout rate was estimated. Therefore, in total 16 individuals with SCI will be enrolled in the project. A further 12 healthy, age- and sex-matched non-injured individuals will be recruited as controls for AIM 1.

Recruitment

The SCI participants will be recruited via a combination of voluntary responses and snowball sampling. A variety of recruitment strategies will be used, including: (1) posters and leaflets displayed in outpatient clinics, local community centres and at outreach group events; (2) presentations or flash talks to SCI communities (eg, local disability sports teams); (3) social media (ie, Facebook, X, websites); and (4) following individual interest. The non-injured control participants will be recruited via convenience sampling, via strategies such as social media posts, staff/student email lists at the University and word-of-mouth. Given the need to age and sex match these participants to the SCI cohort, only individuals that suit these demographics will be eligible for recruitment. Individuals interested in participating will contact a member of the study team to confirm their eligibility and then provide written informed consent. Only individuals with higher neurological levels of injury will be recruited given the greater likelihood of impaired cardiovascular responses during exercise.18,20 Recruitment will also be limited to individuals with motor-complete SCI (AIS A-B) who are typically constrained to volitional upper-body exercise only. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in table 1.

Table 1. Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

SCI participants:

|

SCI participants:

|

AIS, American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; BP, blood pressure; SCI, spinal cord injury; TSCS, transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation

Randomisation

Randomisation will be conducted by the chief investigator (TN) who will assign a miscellaneous code to each participant to allow identification. The order of exercise trials with and without CV-TSCS (AIM 1) will be randomised using a web-based computer software (Research Randomizer: randomizer.org). For AIM 2, TN will generate 16 sealed, brown envelopes with treatment allocations for the exercise intervention (8 CV-TSCS and 8 SHAM-SCS). Following the completion of AIM 1, a random envelope will be selected to allocate each participant into one of the two intervention groups. DH and TN will remain unblinded to treatment allocation as they will be responsible for administering the specific stimulation parameters throughout the intervention, however the participants and remaining collaborators will be blinded. To ensure that participants are blinded to their allocation in AIM 2 (ie, either SHAM-TSCS or CV-TSCS), participants will not be informed of which stimulation parameters they received during each of the acute exercise trials in AIM 1. Participants will also be hidden from BP and other cardiovascular measurements to blind them from their allocation. Furthermore, based on our experiences in a previous study52 and preliminary data as part of this trial, participants are unaware of what stimulation parameters they receive during exercise due to the natural distraction provided by the physical exertion of arm-crank ergometry.

Initial assessments and autonomic function tests

Transcutaneous spinal cord stimulation and mapping session

TSCS will be performed using the non-invasive Spinal Cord Neuromodulator (SCONE; SpineX, Los Angeles, USA). The device will be used with self-adhesive round electrodes (3.2 cm diameter) placed on the skin between spinous processes at the midline over the vertebral column between T8 and L2 spinal segments as a cathode, and two rectangular 5×9 cm self-adhesive electrodes located posteriorly on the skin over the iliac crests as anodes. Specifically, monophasic or biphasic stimulation will be administered, consisting of a pre-programmed 10 kHz carrier frequency combined with low-frequency bursts (30 Hz), each with a pulse width of 1 ms. Current amplitudes for monophasic and biphasic stimulation will range between 10–120 mA and 10–200 mA, respectively. A closed-loop controller system regulates the stimulation intensity applied to the spinal cord. The stimulation intensity can be increased or decreased depending on participants’ ability to effectively maintain BP at a physiological set-point. To reduce the risk of unblinding, details related to the specific SHAM-TSCS condition will only be reported with the results of the trial.

Participants will undergo a baseline mapping session to identify the specific stimulation parameters (ie, specific electrode configurations and intensity of stimulation) that modulate autonomic cardiovascular outcomes (eg, BP, and predicted stroke volume, left ventricular cardiac contractility and total peripheral resistance). Stimulation intensity will be increased until there is a noticeable change in systolic BP from baseline that does not exceed the 150 mmHg cut-off value for pharmacologically-mediated AD intervention.97 Participants will be asked to report symptoms associated with AD throughout (eg, headaches, sweating, goosebumps). Mapping will be performed by repositioning transcutaneous electrodes over specific spinal processes (ie, T8 to L2 spinal segments, to target dormant sympathetic pre-ganglionic neurons below the level of injury) to elicit these optimised responses.52 56 67 A concurrent stepwise increase in stimulation intensity will be applied. During this visit, the participants’ motor activity will be determined via surface electromyography (EMG) recordings placed bilaterally on the trunk (ie, rectus abdominis) and legs (ie, rectus femoris, tibialis anterior and medial gastrocnemius). EMG will be conducted using wireless Bluetooth sensors (Trigno, Delsys, Boston, USA) and the site for each sensor will be prepared by cleaning the skin with rubbing alcohol and removing any hair as necessary with a razor. Data will be recorded at 2000 Hz and stored for offline analysis. Participants will be positioned in the upright, seated position in order to reflect the arm-crank exercise position and to account for spinal curvature. While there is evidence recommending that individuals maintain a neutral or extended spine,98 several other studies have suggested that accounting for curvature may enhance the effectiveness of CV-TSCS in targeting the dorsal root afferents.51 53 99 A trained cardiac sonographer will also perform a transthoracic echocardiogram at the start of the mapping session without CV-TSCS and at the end of the session with CV-TSCS. This will allow us to examine whether there are any beneficial effects of CV-TSCS on cardiac function, as demonstrated previously with ESCS.45

Autonomic function tests

At least 24 hours before arrival, participants will be requested to perform a thorough bowel routine and abstain from alcohol, caffeine consumption and vigorous-intensity exercise. On the visit day, participants will arrive having fasted for at least 1 hour, consuming only water, and will have emptied their bladders before testing begins. Participants will be asked whether they are able to refrain from administering their medication until the testing has finished to eliminate any confounding effects from anticholinergic and sympathomimetic medications on haemodynamic responses.62

Beat-by-beat BP and HR will be recorded via finger plethysmography (NOVA, Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and three-lead ECG, respectively. A resting 15 min baseline will be recorded at the start of each visit. Tests will be split across two visits, either with (a sit-up test, neurovascular coupling and Valsalva manoeuvre) or without (HR response to deep breathing, and cold pressor test) beat-by-beat recordings of cerebral blood velocity via transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. Each test will begin with a resting period to allow haemodynamic responses across tests to return to baseline. For all participants, the order of tests (ie, without and then with CV-TSCS) will not be randomised for the sit-up test, Valsalva manoeuvre or HR response to deep breathing test. This is to avoid prolonged residual physiological effects from CV-TSCS influencing subsequent responses and minimise the additional time burden placed on participants. However, to account for potential familiarisation/habituation to the visual or cold stimuli, participants will perform the neurovascular coupling and cold pressor tests in a randomised order (ie, with then without CV-TSCS, or without then with CV-TSCS). Details of each autonomic function test are described below:

Bedside sit-up test

Participants will rest in the supine position on a bed. Following a 5 min baseline period, participants will be moved into an upright ‘sit-up’ position so that the torso is upright and the legs are unsupported and dangling from the knees at 90° off the bed. The participants will be instructed to remain inactive during the movement so that the procedure is performed as passively as possible. Measurements will then be recorded for 15 min before the participant is returned to the supine position. Beat-by-beat BP, HR and bilateral middle cerebral artery velocity (MCAv) will be monitored throughout with additional brachial BP measurements taken every minute via an automated cuff (Dinamap Pro 300V2, General Electric, Chicago, Illinois, USA), as described previously.100 101 This test has demonstrated reliability in the SCI population.101 The incidence of orthostatic hypotension will be recorded, which will be defined as a drop in systolic or diastolic BP by ≥20 mmHg or ≥10 mmHg, respectively, within the first 3 min of assuming an upright position.102 Where individuals experience this drop in systolic or diastolic BP after the first 3 min, this will be recorded as delayed orthostatic hypotension. The test may be terminated early based on judgement by an experienced researcher or upon a participant reporting presyncope symptoms.

Neurovascular coupling

This test will be conducted in an upright seated position. TCD will be used to assess right posterior cerebral artery velocity and left MCAv. This test has demonstrated a profound association between cognition and abnormal BP in individuals with SCI.103 Participants will be instructed to close their eyes for 30 s and then open their eyes and focus on visual stimuli on a computer screen for 30 s to encourage the activation of the occipital cortex, which will result in an increased cerebral blood velocity in the right posterior cerebral artery to match the neuronal metabolism demands.103 104 This task will be repeated five times.

Valsalva manoeuvre

Participants will be instructed to inhale to total lung capacity and forcefully expire through a tube that incorporates a small leak to prevent glottis closure (Valsalva Assist Device, Meditech Systems, Shaftesbury, UK), at a mouth pressure of 40 mmHg for 15 s.105 Participants will be able to monitor expiratory pressure using a pressure gauge. The Valsalva manoeuvre will be attempted three times, with at least 2 min rest between each manoeuvre to allow systolic BP to return to within ±10 mmHg of baseline. Participants will breathe normally and refrain from moving or talking between attempts. Valsalva ratio will be calculated as the maximum HR during phase II of the Valsalva manoeuvre, divided by the minimum HR within 30 s of phase IV. Further quantitative and qualitative analyses will be conducted as described previously.106 107 MCAv will be assessed bilaterally via TCD.

Heart rateresponse to deep breathing

Participants will be instructed to relax and breathe normally for a 1 min baseline period. They will then perform eight breathing cycles at a frequency of six breaths/min dictated using an auditory cue, requiring 5 s inhalation and 5 s exhalation cycles. Participants will be monitored to ensure they perform each inhalation and exhalation as deeply as possible. The five largest consecutive amplitudes will be averaged to calculate the HR response to deep breathing for each participant.62

Cold pressor test

Participants will be asked to remain quiet for a 1 min baseline recording of BP and HR, after which they will immerse their right hand to wrist level into cold water (≤4°C) for 2 min.108 The participants will then remove their hands and wait for systolic BP to return to within ±10 mmHg of baseline before the procedure is repeated with the right foot immersed to ankle level. Wrist and ankle immersion will then be repeated to ensure responses are reliable.

Spirometry

Forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), FEV1/FVC, peak expiratory flow and forced expiratory flows between 25% and 75% of FVC will be assessed using a spirometer (In2itive, Vitalograph, Buckingham, England). Participants will perform three assessments with and without CV-TSCS, with adequate rest between attempts. Testing will be conducted in accordance with the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society guidelines.109 110

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

For each cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET), participants will first complete a 5 min warm-up on an electronically braked arm-crank ergometer (Angio CPET, Lode, Groningen, the Netherlands) with workload increasing each minute until reaching a rating of perceived exertion (RPE) of 11 (Borg scale: 6–20111). Following a brief rest, they will perform a graded CPET to volitional exhaustion (classified as a cadence <30 rpm on three separate occasions, or for more than 10 s on one occasion), whereby the work rate will be increased every 2 min by 5 W or 10 W for individuals with tetraplegia and paraplegia, respectively.112 113 These increments may be modified following participant feedback during the warm-up (via RPE) to ensure the test duration lasts approximately 8–12 min. Participants will be advised to cycle at approximately 70 rpm. A metabolic cart (Vyntus CPX, Jaeger, Wuerzberg, Germany) with a face mask attached will be used to capture breath-by-breath gas exchange variables. The metabolic cart will be calibrated for volume and known gas concentrations prior to each use, in accordance with manufacturer guidelines. RPE will be recorded following each stage. The highest 15-breath rolling average of oxygen consumption during the test will be recorded as V̇O2peak.114 Peak power output will be determined as the highest wattage achieved in a fully completed incremental stage. Attainment of V̇O2peak will require meeting two of the following three criteria: (1) plateau in V̇O2, (2) respiratory exchange ratio ≥1.15, and (3) RPE≥19.114

AIM 1: acute exercise trials

Participants will be asked to arrive for testing following a 4-hour fast, having also abstained from alcohol and caffeine consumption and vigorous-intensity exercise for >24 hours. Participants will be asked to provide a food diary to record food intake in the 24 hours preceding the visit to standardise their diet across trial days. A thorough bowel management routine will have been completed approximately 24 hours prior to each trial and participants will be asked to empty their bladder prior to exercising.

All exercise trials will be performed on an electronically-braked arm crank ergometer (Angio CPET, Lode, Groningen, the Netherlands). Each trial will begin with a 2 min warm-up at a given work rate (W) corresponding to 31% and 37% of each participant’s V̇O2peak for individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia, respectively.115 Workload will then be increased in 7 min bouts to reflect light, moderate and vigorous exercise intensities115 (table 2). If participants have not fatigued within 21 min, they will perform a further 7 min of vigorous-intensity exercise, after which the intensity will be increased incrementally by 5 W every 3.5 min to accelerate the onset of fatigue. Participants will be advised to cycle at approximately 70 rpm. Time to exhaustion for each participant will be recorded as the duration of the vigorous-intensity exercise performed.

Table 2. Relative exercise intensities (%V̇O2peak) for each 7-min exercise period for individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia.

| Time and relative exercise intensity | Paraplegia | Tetraplegia |

| 0–7 min (light: RPE 9–11) | 40%V̇O2peak | 46%V̇O2peak |

| 7–14 min (moderate: RPE 12–13) | 55%V̇O2peak | 61%V̇O2peak |

| 14–28 min (vigorous: RPE 14–17) | 73%V̇O2peak | 79%V̇O2peak |

| >28 min (RPE>17) | ↑ 5 W every 3.5 min | ↑ 5 W every 3.5 min |

RPE, rating of perceived exertion; V̇O2peak, peak oxygen consumption; W, watts

Participants will first perform one familiarisation session (without TSCS) to cross-check the prescribed exercise intensities. Then, using the optimised SCS parameters obtained from the mapping visit, participants will perform two exercise trials, separated by at least 3 days of recovery, in a randomised order including: (1) CV-TSCS (using the optimal parameters that modulate BP), and (2) SHAM (applying stimulation that does not modulate BP).

During the exercise trials, the following outcomes will be assessed: time to exhaustion at vigorous-intensity (primary outcome measure), gas exchange variables (V̇O2, end-tidal CO2 pressure, respiratory exchange ratio), HR, oxygen pulse (V̇O2/HR), RPE (6–20 Borg scale), beat-to-beat MCAv and skeletal muscle tissue haemodynamics and oxygenation. Brachial BP will also be measured at rest, following the application of CV-TSCS or SHAM-TSCS, after the warm-up and post-exercise (immediately and 15, 30, 60 and 90 min post-exercise). Exercise enjoyment116 and affective valence117 will be measured post-exercise. Venous blood samples will also be collected at rest, immediately post-exercise and 90 min post-exercise to assess concentrations of lactate, circulating catecholamines, inflammatory and immune markers and signalling proteins. Blood samples will not be taken during the familiarisation trials. Further details on these outcomes can be found under Outcome measures.

Healthy non-injured control participants

Twelve healthy, non-injured participants will be recruited that are age- and sex-matched to the SCI cohort, as haemodynamic responses have been shown to differ by sex and age.118 Participants will visit the laboratory four times: (1) informed consent, ANS test battery without TCD and CPET; (2) ANS test battery with TCD, and familiarisation exercise trial; (3) exercise trial to exhaustion with workloads corresponding to their own V̇O2peak; and (4) exercise trial to exhaustion at the same absolute workloads as the SCI participants. The same procedures will be conducted across all visits, but the tests will only be performed without TSCS. Including this group will allow us to characterise responses in a cohort of participants who do not present with autonomic dysfunction and determine to what extent responses are ‘normalised’ with the application of CV-TSCS in the SCI cohort.

AIM 2: exercise intervention

As part of AIM 2, participants will perform 2×48 min per week of aerobic arm-crank exercise sessions, with CV-TSCS or SHAM-TSCS. This volume of exercise aligns with the current SCI-specific exercise guidelines for improving fitness.119 During each session, participants will perform 10×3 min bouts of vigorous-intensity arm-crank exercise, interspersed by 2 min active-rest periods. Participants will be permitted longer rest periods if necessary. Exercise intensity during each 3 min bout will be prescribed at a power output corresponding to~73% and ~79% of each participant’s V̇O2peak for individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia, respectively, as determined from their baseline graded CPET. These population-specific values closely correspond to vigorous-intensity exercise classifications, in comparison to using non-disabled guidelines.115 Exercise intensity will be regulated during the 8-week intervention by capturing participants RPE at the end of each 3 min bout within an exercise session as well as an overall RPE at the end of each session. RPE’s of 14–17 on a 6–20 Borg scale will be classed as vigorous-intensity exercise.115 If self-reported RPE<14, the power output or the number of vigorous-intensity bouts (eg, 10, 11, 12×3 min) for the subsequent exercise session will be increased to ensure an element of progressive overload. Furthermore, perceptual regulation of exercise intensity using RPE has been shown to be a valid approach in the SCI population.120 This will ensure that each exercise session is performed at vigorous-intensity, thereby accounting for possible improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness and obviating the scheduling of multiple CPETs to recalculate relative exercise intensity. The actual targets for duration, intensity and frequency may be adjusted by an accredited clinical exercise physiologist (TN; Academy for Healthcare Science Register ID: 61220) based on the participants’ tolerance to the training parameters. Such an approach has been used previously for progressive exercise training studies performed in this population.121 Where participants miss sessions due to illness or other circumstances, they will be provided with the opportunity to perform ‘make-up’ sessions during an additional week. A 5 min light-intensity warm-up (corresponding to 31% and 37% of each participant’s V̇O2peak for individuals with paraplegia and tetraplegia, respectively) will be performed before each exercise session. Participants will also be instructed to perform a 5 min cool down at a self-selected exercise intensity at the end of each session. During each session, brachial BP will be recorded pre-exercise, mid-exercise and post-exercise on the same arm as a safety measure and to ensure the effects of stimulation have neither subsided (ie, a drop in BP for CV-TSCS) or considerably modulated BP (ie, increase in BP for SHAM).

For participants randomised to the CV-TSCS group, stimulation will be performed continuously throughout each exercise session using the specific stimulation parameters identified during the mapping session in AIM 1. Participants in the SHAM-TSCS group will receive the same sham parameters as AIM 1.

Data collected from the ANS test battery, CPET and spirometry as part of AIM 1 will serve as a baseline for the exercise intervention in AIM 2. These assessments will be repeated following the intervention. Further pre–post intervention assessments include fasted venous blood sampling, central arterial stiffness, cardiac function, cognition, seated balance, 24-hour BP lability, daily energy expenditure and HRV, and HRQoL. Further details on these outcomes can be found under Outcome measures. Mid-way through the exercise intervention, participants will undergo an additional mapping session to identify whether parameters should be manipulated to optimise cardiovascular responses for the subsequent 4 weeks. Participants will also perform a sit-up test and a CPET to quantify any improvements in orthostatic hypotension and cardiorespiratory fitness in the short-term (4 weeks) and long-term (8 weeks) during the exercise intervention. Six weeks following the intervention, participants will complete the HRQoL questionnaires only.

Outcome measures

Time points at which each outcome measure is assessed throughout the study (ie, AIM 1, AIM 2 or both) are presented in figure 2.

Primary outcome measures: time to exhaustion (AIM 1) and cardiorespiratory fitness (AIM 2)

For AIM 1, time to exhaustion will be assessed as the duration of exercise performed at vigorous-intensity during the acute arm-crank exercise trials with and without CV-TSCS. This exhaustion measure will be determined as a drop in cadence below 30 rpm on three separate occasions, or for more than 10 s on one occasion.

For AIM 2, cardiorespiratory fitness will be assessed as V̇O2peak achieved during a graded CPET on an arm-crank ergometer until volitional exhaustion, as described above. This will be assessed prior to (0 weeks), halfway through (4 weeks) and at the end of the 8-week exercise intervention.

Secondary outcome measures

Haemodynamic, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes

Beat-by-beat BP and HR will be recorded during the mapping session and ANS test battery via finger plethysmography (NOVA, Finapres Medical Systems, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and a three-lead ECG, respectively. Stroke volume, left ventricular cardiac contractility and total peripheral resistance will be predicted using the integrated Modelflow® algorithm. Data will be sampled at 1000 Hz through an analogue-to-digital converter (PowerLab 16/35 System, AD Instruments, Oxford, UK) and beat-by-beat BP will be corrected using episodic brachial BP measurements (Dinamap Pro, GE HealthCare, Chicago, USA) via data acquisition software (LabChart 8, AD Instruments, Oxford, UK). Data will be presented as a 30 s rolling average, with mean and peak responses used in analyses.

Cerebral blood velocity in the middle cerebral artery (MCA; neurovascular coupling test, sit-up test, Valsalva manoeuvre, acute exercise trials) and posterior cerebral artery (PCA; neurovascular coupling test) will be insonated using TCD ultrasonography probes (2 MHz probe; MultiDop X4, DWL, Singen, Germany) secured into an adjustable headset (DiaMon, DWL, Singen, Germany). Both MCA and PCA will be located using standardised and well-established search techniques involving probe placement over the zygomatic arch for transtemporal window insonation.122

Tissue haemodynamics and oxygenation will be measured via near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS; NIRO-200NX, Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Near-infrared probes will be placed over the skin of lower-limb and upper-limb skeletal muscle tissue to assess whether TSCS influences the oxygenation of non-active and active limbs during arm-crank exercise. Near-infrared spectroscopy will measure tissue oxygenation index, normalised tissue haemoglobin index and changes in the concentration of oxygenated, deoxygenated and total haemoglobin at the local level.

HRV will be assessed as described previously.123 Participants will be instructed to undergo natural, spontaneous breathing for an initial 7 min period followed by paced breathing for a further 7 min, given that HRV has been shown to be influenced by respiration in the SCI population.123 Participants will breathe in response to auditory cues for inspiration and expiration at a frequency of 15 breaths per minute. The final 5 min of each 7 min period will be extracted for analysis. Time-domain (eg, HR and the root mean square of successive R-R interval differences) and frequency-domain (eg, very-low-frequency, low-frequency, high-frequency and total power) measures of HRV and baroreflex sensitivity will be calculated using the R-R intervals and BP responses recorded during each breathing period.

BP lability will be quantified using a BP monitor (Mobil-o-Graph NG Device; Numed Healthcare, UK) on the participants’ left upper-arm. The device will record BP and HR in 15 min intervals during daytime (09:00–21:00), 60 min intervals during night-time (21:00–06:00) and 30 min intervals the following morning (06:00–09:00). Participants will maintain a diary recording any significant events that would likely cause a change in BP (eg, physical activity, bowel/bladder routines, transfers) or when experiencing any symptoms of BP instability (eg, dizziness, fatigue, headache). They will also be requested to trigger a manual BP measurement on the device when these events occur. In the case of poor hand motor function, caregivers/spouse will be asked to provide diary notes and trigger the device. The frequency and severity of AD or hypotensive events will be captured. The 24-hour ambulatory BP data will also enable us to quantify BP variability (eg, average real variability, coefficient of variation). BP instability will also be self-reported via The Autonomic Dysfunction Following SCI Questionnaire.124

Central arterial stiffness is an independent predictor of cardiovascular-related and all-cause-related mortality125 126 and has been shown to be increased in individuals with SCI.127 Following an overnight fast, arterial pulse waveforms will be acquired at two locations (carotid and femoral arteries) simultaneously to determine pulse transit time and carotid-to-femoral pulse wave velocity. This will be performed using the Vicorder (Smart Medical, Moreton in Marsh, UK) with standard vascular cuffs, which is operator independent and has demonstrated evidence of reliability.128

Cardiac function is impaired following SCI.129,131 Indices of left ventricular function (eg, mitral inflow, myocardial velocities, stroke volume, ejection fraction) will be assessed via transthoracic echocardiography using a Vivid iq ultrasound system (General Electric Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) in accordance with recommendations of the American Society for Echocardiography and European Association of Echocardiography.132 Images will be stored for offline analysis using specialised computer software (EchoPAC V.206, General Electric Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) by a single analyser, blinded to time point and group allocation. The average of three cardiac cycles will be used to determine left ventricular functional indices. Indices of left ventricular mechanics (eg, strain, torsion and twist) will be analysed using two-dimensional speckle-tracking software in accordance with recommended guidelines.133

Respiratory function

Spirometry will be performed with and without CV-TSCS during AIM 1 and will be repeated following the exercise intervention as part of AIM 2.

Blood biomarkers

All venous blood samples will be drawn from the antecubital vein by a trained phlebotomist. For AIM 1, 20 mL samples will be collected before, immediately-post, and 90 min following the acute exercise trials with CV-TSCS and SHAM-TSCS. For AIM 2, 25 mL samples will be collected at rest following an overnight fast before and after the exercise intervention. Post-intervention samples will be taken no earlier than 48 hours following the final exercise intervention session. All serum and plasma samples will be dispensed into 1 mL aliquots and stored at −80°C for batch analysis. An outline of the planned analyses for AIM 1 and AIM 2 are presented in table 3.

Table 3. Blood biomarker analyses.

| AIM 1 | Analytical techniques |

| Haematological profile | |

| Red blood cell, white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet counts, haemoglobin concentrations, haematocrit and haematic indices | Automated haematology system (Horiba Yumizen H500, Horiba Medical, Kyoto, Japan) |

| Catecholamines and metabolic markers | |

| Lactate | Lactate-Glo assay (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) |

| Epinephrine and norepinephrine | CatCombi ELISA (IBL International, Männedorf, Switzerland) |

| Growth factors | |

| BDNF | ELISA (DuoSet, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) |

| Cytokines | |

| Interleukin-6 | ELISA (plasma interleukin-6 high sensitivity, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) |

| Immunophenotyping | |

| T cells (naïve, central memory, effector memory, terminally differentiated effector memory and angiogenic), natural killer cells (regulatory and cytolytic) and monocyte subsets (classical, intermediate and non-classical) | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells will be isolated from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation and stained with fluorescent conjugated antibodies for analysis using flow cytometry |

| AIM 2 | Analytical techniques |

| Haematological profile | |

| Red blood cell, white blood cell, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte and platelet counts, haemoglobin concentrations, haematocrit and haematic indices | Automated haematology system (Horiba Yumizen H500, Horiba Medical, Kyoto, Japan) |

| NGF | ELISA (DuoSet, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) |

| Insulin | ELISA (Mercodia AB, Uppsala, Sweden) |

| C-reactive protein, glucose, HbA1c/Hb and lipid profile (triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL-C, LDL-C, apolipoprotein B) | Automated analyser (Randox RX Daytona+, Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK), in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions using commercially available immunoassays (Randox Laboratories, Antrim, UK) |

BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; HbA1c/Hb, glycated haemoglobin; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NGF, nerve growth factor

Cognition

Cognitive function will be assessed via a shortened neuropsychological test battery, which has previously demonstrated good-to-excellent reliability in individuals with SCI.134 The test battery will be administered orally (ie, motor-free) in a quiet, well-lit room by an experienced researcher, with individual tests targeting various cognitive domains, which include: (1) Digit Span Task (working memory), (2) Oral Symbol Digit Modalities Test (attention, visual scanning) and (3) Controlled Word Association Test (verbal fluency).

Motor function

Trunk stability has been shown to improve following upper-body exercise interventions,135 136 potentially due to a shared control mechanism between the arm and trunk muscles that facilitates corticospinal excitability projecting to the trunk muscles upon arm muscles contracting.136 137 TSCS alone has also demonstrated restoration of trunk stability and upright posture.138 Therefore, combining both upper-body exercise with TSCS may additively improve trunk control. To assess static and dynamic seated balance we will use the validated Function in Sitting Test-SCI.139 EMG sensors will be affixed to the trunk extensors and flexors during each trial to objectively quantify improvements in skeletal muscle activity.

Corticospinal and spinal excitability of respiratory muscles will be assessed using a Magstim 2002 monophasic stimulator (The Magstim Company, UK) through a circular coil. Cervical magnetic stimulation will first be applied over the C3-C7 vertebrae to stimulate the phrenic nerve to evoke diaphragmatic compound muscle action potentials, which will be recorded by chest wall surface EMG, as conducted previously.140 Corticospinal projections from the motor cortex to the diaphragm will then be assessed using transcranial magnetic stimulation. The optimal cortical stimulation site will be identified by moving the coil around the vertex until the largest evoked potential amplitude is observed.141 Stimulus intensity will range from below the resting motor threshold (RMT) to 100% of the maximum stimulator output, increasing by 5% increments, to establish the motor-evoked potential (MEP) recruitment curves of the diaphragm. The RMT is defined as the lowest stimulus intensity that elicits visible MEPs in at least three of six consecutive trials.137 142 Ten stimuli, with an inter-stimulus interval of 5 s, will be delivered at each intensity to produce a mean peak-to-peak amplitude of MEPs. All magnetic stimulation tests will strictly follow published safety, ethical considerations and application guidelines.143 This assessment will be performed before and after the first 8-week exercise intervention session to explore the acute (single session) effects of receiving CV-TSCS or SHAM-TSCS during exercise on the neural drive to respiratory muscles. At the end of the 8-week intervention, this assessment will be performed at rest only and the data from baseline will be used as a comparison to post-intervention to investigate whether there are any longitudinal changes in the neural drive to respiratory muscles that may indicate plasticity.

Daily energy expenditure

Participants will wear an individually calibrated multisensor device for 4 days.3 The Actiheart (Cambridge, Neurotechnology, Papworth Everard, UK) incorporates tri-axial accelerometry and HR to predict physical activity energy expenditure using our previously described individual calibration approach.144 The device will also quantify free-living fluctuations in HRV across a 4-day period.

HRQoL

Bowel function will be assessed via the Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction Score.145 This uses 10 items that are weighted based on their impact on quality of life. The maximum score is 47, while the minimum is 0. Scores are totalled to calculate the severity of bowel dysfunction based on the following thresholds: Very minor (0–6), minor (7–9), moderate (10–3) or severe (14+).

Bladder function will be assessed using The Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score,146 which is a 24-item questionnaire scoring symptoms relating to incontinence (scored 0–29), storage and voiding (scored 0–22) and consequences (scored 0–23), where higher scores represent a worse symptom burden. The questionnaire also includes one general quality of life question scored from 0 (pleased) to 4 (unhappy).

Sexual function for males will be assessed via The International Index of Erectile Function.147 This 15-item questionnaire asks participants to reflect on their sex life within the last 4 weeks, with each question rated on a scale from 0 to 5 and assesses the four domains of male sexual function: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire and intercourse satisfaction. Sexual function for females will be assessed via The Female Sexual Function Index,148 which is a 19-item questionnaire measuring six domains of female sexual function: sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction and pain (ie, pain associated with penetration). Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5, with lower scores indicating lower levels of sexual function. Fifteen items also include a zero score as a sixth response option indicating no sexual activity in the past 4 weeks. Total scores across each domain are calculated using weighting factors.

Overall HRQoL will be assessed using the Short Form-36 (SF-36) walk/wheel questionnaire.149 This questionnaire consists of four subscales of physical quality of life and four subscales of emotional quality of life. Given the notable wording issues in the questionnaire relating to non-injured activities (eg, stair climbing and walking), these words will be replaced with ‘go’ and ‘go up’.150,152

Illness log

A non-validated, in-house illness log will be used to capture illnesses or symptoms of illnesses during each week of study enrolment. Participants will be requested to confirm whether they have experienced any of the 10 listed health codes: (1) no health problems, (2) sick with cold symptoms, (3) sick with influenza symptoms, (4) sick with nausea/vomiting, (5) muscle, joint or bone problems, (6) urinary tract infection symptoms, (7) severe AD, (8) neuropathic pain symptoms, (9) allergen symptoms, or (10) other health problems. Participants will rate the severity of these symptoms on a scale from 1 (almost completely bearable) to 10 (completely unbearable).

Trial feasibility

The Participant Evaluation of Feasibility and Acceptability Questionnaire will be used to obtain information on the usability and satisfaction of adopting CV-TSCS during an exercise intervention in individuals with SCI. This consists of six items arranged on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An overall score of 3 or greater will be used to indicate that the CV-TSCS intervention was acceptable; an approach previously used for individuals living with SCI.153 Additionally, four open-ended questions will be incorporated to assist in identifying the biggest facilitators for exercise; the biggest challenges/barriers to exercise; benefits received from participating in the CV-TSCS exercise intervention; and suggestions for other individuals with SCI to engage in such exercise interventions. Posteriori content analysis will be used for data generated from these questions involving two independent researchers, which will result in themes/categories being quantified with the calculation of frequencies.154 Adverse events (AEs) will be recorded for the duration of the study for each participant (ie, enrolment to the 6-week follow-up period).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses will be conducted using R Statistical Software (V.3.5.2., R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance will be set at p<0.05. Descriptive parameters will be calculated including the appropriate measure of central tendency (eg, mean or median) and variability (eg, standard deviation or interquartile range). For AIM 1, linear mixed models will be performed to identify differences in outcome measures collected during the ANS test battery and acute exercise trials with and without CV-TSCS, and compared with the non-injured cohort. For AIM 2, linear mixed models will be performed to identify changes in outcomes from pre-intervention to mid-intervention and post-intervention across both CV-TSCS and SHAM-TSCS groups. Linear mixed models will also be performed for HRQoL outcomes that are assessed pre–post intervention and at the 6-week follow-up period.

Data management

The chief investigator (TN) will be the custodian of all data. All data management will comply with the Data Protection Act 2018. Data will be stored in line with the University of Birmingham’s policy at the termination of the project and will be kept, securely, for 10 years following completion. All electronic data will be housed on the University of Birmingham’s secure servers. Any transfer of electronic data will be in line with the University of Birmingham IT guidance and will be part of a signed data transfer agreement. Data will be entered into Microsoft Excel documents, which will be password-protected and accessed using a secure VPN. There will be two separate files created, one containing participant identifiable data (ie, name, date of birth, contact details) and a second containing coded results. Only the research team will have access to these documents. All source data (eg, results, information gathered, observations made and activities recorded during exercise trials) recorded on paper, and signed informed consent forms, will be kept in a binder and in a locked filing cabinet at the School of Sport, Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences, accessible only by the research team. If there are acellular (eg, plasma/serum) biological samples remaining on study completion, they will be kept for no longer than 10 years, before being disposed of according to the ‘Human Tissue Code of Practice’ at the end of this time. For analysis of immune markers, peripheral blood mononuclear cell samples will be kept in liquid nitrogen storage in the Human Biomaterials Resources Centre—a Human Tissue Authority licensed human sample biorepository operated by the University of Birmingham. If samples are to be used for analyses distinct from those outlined in the current project, then further ethical approval will be sought. Any samples used for future research will be anonymised and participants may opt-out of this when providing informed consent.

Ethics and dissemination

All safety concerns have been carefully considered during the development of this protocol and have been approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC). Participants will be made fully aware of the risks prior to providing informed consent. All amendments to the protocol will be signed off by the study sponsor (University of Birmingham) before submission to the REC for approval. All researchers involved in this study will have undertaken Good Clinical Practice training. All AEs will be documented. Any serious AEs will be immediately reported to the chief investigator (TN) within 24 hours, who will then inform the study sponsor and REC within 15 days. Participants will be informed of their right to withdraw at any time during the study and up to 2 weeks after the post-intervention follow-up period. There will be no consequences to any participant who withdraws from the study. The University of Birmingham, as the trial sponsor, will be responsible for conducting internal audits of trial conduct and compliance with the protocol, standard operating procedures and Good Clinical Practice and will be responsible for coordinating external audits.

The results of this trial will be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals and presented at exercise (eg, European College of Sport Science, American College of Sports Medicine) and SCI-specific (eg, American Spinal Injury Association, International Spinal Cord Society, International Spinal Research Trust) conferences. Data sets generated during the study will be stored on public repositories such as GitHub or we will provide a statement that data will be made available on reasonable requests to the corresponding author. All data used for such purposes will remain anonymised. Once participants have completed their enrolment, they will receive individualised feedback on their results. However, it will be made clear that members of the direct research team are not medical professionals and that these results should not be viewed as diagnostic measures.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study to comprehensively assess the effects of TSCS on: (1) cardiovascular and cerebrovascular responses to autonomic challenges at rest, (2) cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, metabolic and immune responses to arm-crank exercise, and (3) long-term alterations in cardiorespiratory fitness, cardiometabolic health, autonomic cardiovascular function, respiratory function, cognition, trunk stability and HRQoL, when paired with an arm-crank exercise intervention.

These findings may have important ramifications for supporting individuals with SCI across the physical activity spectrum, be that elite athletes (eg, Paralympians), trained, untrained or sedentary individuals. TSCS may also be an efficacious rehabilitative strategy to stimulate meaningful physiological adaptations to exercise in the acute setting following SCI. This may help to offset the significant reductions in cardiac function,131 vascular alterations below the level of injury,155 156 and the increase in cardiometabolic disease risk factors157 that are typically observed within the first 6 months post-SCI.

Our recent meta-regression identified that the effects of exercise interventions on cardiorespiratory fitness are diminished in older adults with SCI, relative to younger and middle-aged adults.7 Therefore, combining exercise with TSCS may mitigate some of the detrimental effects associated with accelerated ageing following SCI.158 Our findings may also pave the way for studies investigating neuroplasticity to autonomic circuits with TSCS, as has been demonstrated in a recent pre-clinical study.159 Finally, given the preliminary evidence supporting the benefits of SCS in other clinical populations,160,164 our findings may therefore stimulate further research into ameliorating the effects of ANS dysfunctions (eg, multiple systems atrophy or multiple sclerosis), altered motor function (eg, stroke or Parkinson’s disease) or body composition (eg, traumatic limb loss), representing a wider impact and benefit for society.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Parag Gad and SpineX for the generous in-kind donation of the SCONE device. We would also like to thank Spinal Research, Aspire and the Spinal Injuries Association for promoting the study. Lastly, we are grateful for the support of Professor Tania Lam and Mrs Alison Williams (Both at the International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries, University of British Columbia, Canada) who are assisting with the processing and analysis of EMG data.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by a Nathalie Rose Barr PhD studentship (DDH) awarded by the International Spinal Research Trust (grant number NRB123) and an Academy of Medical Sciences Springboard Award (TEN, grant number SBF009\1126). SJTB receives salary support from Heart Research United Kingdom (grant number RG2698/21/23). PAC receives salary support as part of an Academy of Medical Sciences Springboard Award (TEN, grant number SBF009\1126).

Prepub: Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089756).

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

References

- 1.Hou S, Rabchevsky AG. Autonomic consequences of spinal cord injury. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1419–53. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1371–83. doi: 10.1089/neu.2004.21.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nightingale TE, Williams S, Thompson D, et al. Energy balance components in persons with paraplegia: daily variation and appropriate measurement duration. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14:132. doi: 10.1186/s12966-017-0590-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Berg-Emons RJ, Bussmann JB, Stam HJ. Accelerometry-based activity spectrum in persons with chronic physical conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1856–61. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soriano JE, Squair JW, Cragg JJ, et al. A national survey of physical activity after spinal cord injury. Sci Rep. 2022;12:4405. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-07927-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simmons OL, Kressler J, Nash MS. Reference fitness values in the untrained spinal cord injury population. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:2272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodgkiss DD, Bhangu GS, Lunny C, et al. Exercise and aerobic capacity in individuals with spinal cord injury: A systematic review with meta-analysis and meta-regression. PLoS Med. 2023;20:e1004082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Myers J, Lee M, Kiratli J. Cardiovascular disease in spinal cord injury: an overview of prevalence, risk, evaluation, and management. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:142–52. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31802f0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Krassioukov A, et al. Cardiovascular disease and spinal cord injury: results from a national population health survey. Neurol (ECronicon) 2013;81:723–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a1aa68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu J-C, Chen Y-C, Liu L, et al. Increased risk of stroke after spinal cord injury: a nationwide 4-year follow-up cohort study. Neurol (ECronicon) 2012;78:1051–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824e8eaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachdeva R, Gao F, Chan CCH, et al. Cognitive function after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. Neurol (ECronicon) 2018;91:611–21. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahmoudi E, Lin P, Peterson MD, et al. Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury and Risk of Early and Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia: Large Longitudinal Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeVivo MJ, Chen Y, Wen H. Cause of Death Trends Among Persons With Spinal Cord Injury in the United States: 1960-2017. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2022;103:634–41. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV. Contemporary Cardiovascular Concerns after Spinal Cord Injury: Mechanisms, Maladaptations, and Management. J Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1927–42. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzelnick CG, Weir JP, Jones A, et al. Blood Pressure Instability in Persons With SCI: Evidence From a 30-Day Home Monitoring Observation. Am J Hypertens. 2019;32:938–44. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpz089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Wecht JM, Legg Ditterline B, et al. Heart rate and blood pressure response improve the prediction of orthostatic cardiovascular dysregulation in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Physiol Rep. 2020;8:e14617. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groah SL, Weitzenkamp D, Sett P, et al. The relationship between neurological level of injury and symptomatic cardiovascular disease risk in the aging spinal injured. Spinal Cord. 2001;39:310–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Partida E, Mironets E, Hou S, et al. Cardiovascular dysfunction following spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2016;11:189–94. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.177707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz S, Blauwet CA. Implications of altered autonomic control on sports performance in athletes with spinal cord injury. Auton Neurosci. 2018;209:100–4. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2017.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.West CR, Gee CM, Voss C, et al. Cardiovascular control, autonomic function, and elite endurance performance in spinal cord injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:476–85. doi: 10.1111/sms.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claydon VE, Hol AT, Eng JJ, et al. Cardiovascular responses and postexercise hypotension after arm cycling exercise in subjects with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;87:1106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West CR, Mills P, Krassioukov AV. Influence of the neurological level of spinal cord injury on cardiovascular outcomes in humans: a meta-analysis. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:484–92. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmid A, Huonker M, Barturen JM, et al. Catecholamines, heart rate, and oxygen uptake during exercise in persons with spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85:635–41. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figoni SF, Dolbow DR, Crawford EC, et al. Does aerobic exercise benefit persons with tetraplegia from spinal cord injury? A systematic review. J Spinal Cord Med. 2021;44:690–703. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1722935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burnham R, Wheeler G, Bhambhani Y, et al. Intentional induction of autonomic dysreflexia among quadriplegic athletes for performance enhancement: efficacy, safety, and mechanism of action. Clin J Sport Med. 1994;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmid A, Schmidt-Trucksäss A, Huonker M, et al. Catecholamines response of high performance wheelchair athletes at rest and during exercise with autonomic dysreflexia. Int J Sports Med. 2001;22:2–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nightingale TE, Eginyan G, Balthazaar SJT, et al. Accidental boosting in an individual with tetraplegia - considerations for the interpretation of cardiopulmonary exercise testing. J Spinal Cord Med. 2022;45:969–74. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2020.1871253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gee CM, Lacroix MA, West CR. Effect of Unintentional Boosting on Exercise Performance in a Tetraplegic Athlete. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50:2398–400. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hopman MT, Oeseburg B, Binkhorst RA. The effect of an anti-G suit on cardiovascular responses to exercise in persons with paraplegia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:984–90. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houtman S, Thielen JJ, Binkhorst RA, et al. Effect of a pulsating anti-gravity suit on peak exercise performance in individual with spinal cord injuries. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1999;79:202–4. doi: 10.1007/s004210050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pitetti KH, Barrett PJ, Campbell KD, et al. The effect of lower body positive pressure on the exercise capacity of individuals with spinal cord injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:463–8. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199404000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]