Abstract

Abstract

Objective

Burnout syndrome, characterised by emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and decreased personal accomplishment, is well documented in the medical workforce. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of burnout in New Zealand resident doctors (doctors who have yet to complete their specialty training).

Design

Cross-sectional survey study of resident doctors in New Zealand.

Setting

Distributed by email.

Participants

509 resident doctors currently working in New Zealand. Doctors not currently working or those who have completed their specialty training (consultants) were excluded.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Participants were asked about a number of demographic and work-related factors and to complete the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which measures the three dimensions of burnout: ‘Emotional Exhaustion’, ‘Depersonalisation’ and low ‘Personal Accomplishment’.

Results

409/509 (80%) of respondents had scores indicating high burnout on at least one dimension. 163 (32%) had high burnout on one dimension, 111 (22%) on two dimensions and 135 (26%) on all three dimensions. Feeling well supported protected against burnout in all three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (OR 0.34, CI 0.19 to 0.60), depersonalisation (OR 0.52, CI 0.31 to 0.86) and decreased personal accomplishment (OR 0.51, CI 0.29 to 0.78). Having a manageable workload protected against emotional exhaustion (OR 0.23, CI 0.13 to 0.37) and depersonalisation (OR 0.39, CI 0.24 to 0.61). Increasing weekly exercise was protective for personal accomplishment (OR 0.846, CI 0.73 to 0.98). Having children was protective for depersonalisation (OR 0.7, CI 0.53 to 0.90). A personal history of depression or anxiety was associated with burnout on all three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (OR 2.86, CI 1.67 to 5.00), depersonalisation (OR 1.66, CI 1.01 to 2.73) and decreased personal accomplishment (OR 1.71, CI 1.05 to 2.80). Alcohol misuse was associated with an increased risk of depersonalisation (OR 1.68, CI 1.08 to 2.62), and feeling inadequately remunerated was associated with emotional exhaustion (OR 2.27, CI 1.28 to 4.17). Qualitative data revealed concerns about poor staffing, inadequate remuneration, a focus on service provision over education, slow career progression and difficulty balancing work and specialty examinations.

Conclusions

Burnout has a high prevalence in New Zealand’s resident doctor workforce. Several associations and qualitative themes were identified. These findings may aid in the development of interventions to mitigate burnout in the medical workforce.

Keywords: Burnout, MEDICAL EDUCATION & TRAINING, Occupational Stress

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study uses a validated tool to assess burnout in the New Zealand resident doctor population, with qualitative responses to contextualise the findings.

Previous research has identified that workforce surveys yield valid burnout estimates despite typically having low response rates.

Despite this, non-response bias may mean that the results are not representative of the resident doctor population as a whole.

As a cross-sectional study, temporality cannot be established between some of the identified associations and the presence of burnout.

Introduction

Burnout in the medical field has been well documented around the world, with higher rates of burnout reported in medical doctors when compared with the general public.1 2 Burnout has also been associated with various demographic and work-related factors, including age, relationship status and workplace seniority.3 In the New Zealand Senior Medical Officer (specialist) workforce, burnout has been associated with female gender, younger age, poor self-rated health status and certain specialties.4

One leading theory of burnout describes it as a syndrome composed of three main facets: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalisation (DP) and a low sense of personal accomplishment (PA).5 EE manifests as feelings of exhaustion resulting from the psychological efforts made at work.6 DP is defined as a response of detachment, indifference and unconcern towards the work being performed and/or the people who receive it.6 PA is reflected in a negative professional self-evaluation and doubts about the ability to perform the job effectively, as well as a greater tendency to evaluate results negatively.5,8

Burnout has been found to be associated with an increased risk of medical errors and reduced quality of care.9,13 A systematic review on the topic found that burnout was associated with poor quality of care but noted that the true effect size may be smaller than reported for a number of reasons.14 In addition, burnout is clearly worrisome for the health of those affected and may have implications for medical workforce retention and absenteeism.15

There are reports of increased burnout during the early stages of training, with less work experience, in resident physicians and in younger specialist physicians.3 4 16 The COVID-19 pandemic brought additional challenges for people working in the health system, which may have influenced experiences of burnout.17

Resident Medical Officers (resident doctors) are doctors who have finished medical school but are yet to complete their postgraduate specialist training. Resident doctors can have anywhere from one to ten or more years of postgraduate experience.

While previous work has explored burnout in the New Zealand specialist medical workforce4 and a small subset of resident doctors (orthopaedic surgery registrars),18 no study has assessed the rates of burnout in New Zealand resident doctors as a whole. Using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), this cross-sectional study aimed to assess the prevalence of burnout in the New Zealand resident doctor population, as well as any associations between demographic and other work-related factors and burnout. Identifying factors associated with burnout and establishing a baseline prevalence will be useful for implementing strategies to reduce the burden of burnout and as a basis for further studies.

Methods

Informed consent was obtained from each participant using an Information Sheet and a ‘Consent to Participate’ select box, both approved by the committee. Between December 2023 and March 2024, an email link to an anonymous 53-question survey (SurveyMonkey) was sent to all 1812 resident medical officers (resident doctors) on the Specialty Trainees of New Zealand Union mailing list. To minimise non-response bias, the entire mailing list of the doctor’s union was used, without regard to specialty or career stage. Multiple follow-up attempts were made (up to three reminders), and the demographics of the respondents are reported to allow consideration of generalisability. The Checklist for Reporting Of Survey Studies was used and is available in the online supplemental materials.

The first part of the survey asked about demographic factors (gender, ethnicity, age, relationship status, children, socioeconomic status as estimated by childhood familial income), work and career-related data (postgraduate year (PGY), role, specialty, hours worked per week, hours preparing for teaching per week, whether currently studying for college examinations and roster type) and other background questions (time since last annual leave, whether work was considered manageable, adequate financial remuneration, whether the participant felt supported and recent belittling by senior staff members). Participants were also asked about alcohol use, with the three questions of the AUDIT C screening tool embedded in the demographic section. Participants with scores of ≥3 for female participants and ≥4 for male participants were considered to be at risk of alcohol misuse.19

To maximise participation, participants could choose to leave any demographic or background questions they were uncomfortable with blank. When calculating demographic data for survey participants, only those who answered a particular question were included. For example, if 496 participants indicated their gender, 496 (rather than 509) was used as the denominator when calculating the percentage of respondents who were male, female or non-binary/other.

The second part of the survey contained the Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel, a validated tool used to assess burnout.5 The MBI assesses the three main facets of Burnout: Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalisation and PA in a 22-question survey. For each facet of burnout, a total severity score can be calculated, stratified and ranked into either low, medium or high. Burnout manifests as higher scores in the EE and DP facets and lower scores in the PA facet. Cut-offs and scores are summarised in table 1. A resident doctor was considered ‘burnt out’ if they scored in the high burnout range for any of the three facets. Potential factors were then assessed to see if there were any statistically significant associations related to each facet of burnout.

Table 1. Maslach burnout index score summary18.

| Emotional exhaustion score (0–54) | Depersonalisation score (0–30) | Personal accomplishment score (0–48) | |

| Low burnout | <19 | <6 | >39 |

| Moderate burnout | 19–26 | 6–9 | 34–39 |

| High burnout | >26 | >9 | <34 |

Statistics

Multivariable logistic regression was used to establish independent associations between potential risk factors and the outcome. Missing data were handled using the complete-case method under the ‘missing completely at random’ assumption.20 Results from logistic regression models are presented as OR, aOR, with their respective 95% CI. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. To assess potential multicollinearity, the mean scaled generalised variance inflation factor (GVIF) was calculated for each model. Analyses were performed using and R Statistical Software (V.4.3.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Qualitative data

As part of the survey, respondents were given a free-text box with the instruction ‘Please enter any other comments regarding your current feelings about work and what factors you think contribute to this.’ The qualitative data were analysed using established coding and analysis methods.21 Patterns in the open-ended responses were initially identified by coding the text into categories such as staffing, support, remuneration, career progression, workload and nature of work. All responses across all participants that were coded in each category were then reviewed together to identify common themes and develop new insights. For example, all text coded as ‘career progression’ was reviewed together to develop a deeper and more nuanced picture of the underlying training concerns among resident doctors.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of this study.

Results

The survey was sent to 1812 doctors a total of three times, of whom 509 completed it (28% response rate). 53% of respondents were female and 47% were male. The median age of survey respondents was 30–34 years. The demographic data of survey respondents are outlined in table 2. 80% (409/509) of respondents had scores indicating high burnout on at least one dimension (high levels of EE, DP, or low PA). 100 (20%) respondents reported no burnout markers, 163 (32%) had burnout on one dimension, 111 (22%) on two and 135 (26%) had burnout on all three measured facets.

Table 2. Demographic data of survey respondents.

| Demographic | Number of respondents (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 232 (47) |

| Female | 262 (53) |

| Non-binary/other | 2 (0) |

| Age | |

| 20–24 | 10 (2) |

| 25–29 | 143 (29) |

| 30–34 | 220 (45) |

| 35–39 | 96 (19) |

| 40+ | 25 (5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Māori | 27 (6) |

| Pākehā/New Zealand European | 250 (55) |

| Pacific | 8 (2) |

| Asian | 101 (22) |

| Other | 71 (15) |

| Years of experience post medical school (PGY year) | |

| 1–3 | 70 (16) |

| 4–5 | 103 (23) |

| 6–7 | 125 (28) |

| 8–9 | 68 (15) |

| 10+ | 77 (18) |

| Role | |

| Medical registrar (basic trainee) | 42 (9) |

| Medical registrar (advanced trainee) | 86 (18) |

| Junior registrar/non-trainee (surgical specialty) | 75 (16) |

| Senior registrar/trainee (surgical specialty) | 61 (13) |

| Other training programme registrar (GP, anaesthetics, radiology, emergency medicine, rural hospital, etc) | 125 (26) |

| House officer/senior house officer (prevocational) | 85 (18) |

GP, general practitionerPGY, postgraduate year

Associations

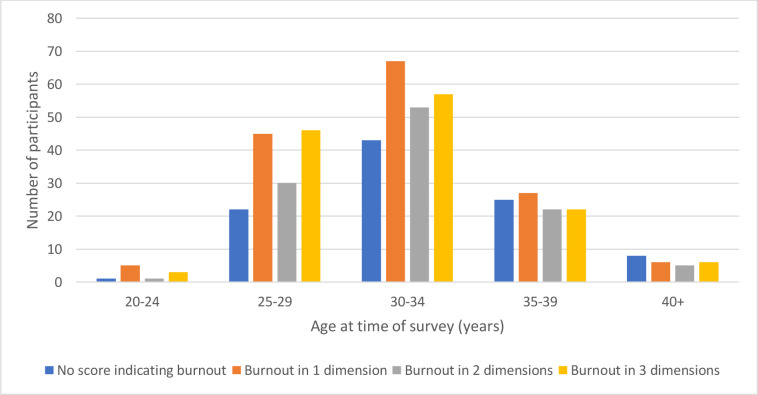

Burnout scores by gender and age group are visualised in figures1 2, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in burnout prevalence based on demographic data including gender, age, ethnicity, PGY year or role (table 2). The factors independently associated with burnout syndrome, as determined by multivariate analysis, are shown in table 3. The feeling of having a manageable workload, being adequately remunerated and being well supported were all protective for EE. Alcohol misuse was associated with increased DP. Having children, feeling well supported and having a manageable workload were all protective for DP. Feeling well supported and exercising frequently were associated with increased PA. A personal history of depression or anxiety was associated with EE, DP and PA. The mean scaled GVIF for the EE, DP and PA models were below 2 (1.08, 1.14 and 1.08, respectively), indicating no relevant multicollinearity in any of the models.

Figure 1. Number of participants with a survey score indicating high burnout by gender. ‘No score indicating burnout’ indicates no score indicating high burnout across any of the 3 dimensions (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, reduced personal accomplishment). ‘Burnout in 1 dimension’ represents a score indicating high burnout in any 1 of the 3 dimensions. ‘Burnout in 2 dimensions’ represents a score indicating high burnout in any 2 of the 3 dimensions. ‘Burnout in 3 dimensions’ represents a score indicating high burnout in all 3 dimensions.

Figure 2. Number of participants with a survey score indicating high burnout by age at time of survey. ‘No score indicating burnout’ refers to no score indicating high burnout across any of the 3 dimensions (emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, reduced personal accomplishment). ‘Burnout in 1 dimension’ represents a score indicating high burnout in any 1 of the 3 dimensions. ‘Burnout in 2 dimensions’ represents a score indicating high burnout in any 2 of the 3 dimensions. ‘Burnout in 3 dimensions’ represents a score indicating high burnout in all 3 dimensions.

Table 3. Factors independently associated with burnout syndrome by multivariate analysis.

| OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Emotional exhaustion | |||

| Protective | |||

| Feeling the workload is manageable | 0.23 | 0.13 to 0.37 | <0.01 |

| Feeling well supported | 0.34 | 0.19 to 0.60 | <0.01 |

| Risk factors | |||

| History of depression/anxiety | 2.86 | 1.67 to 5.00 | <0.01 |

| Feeling inadequately remunerated | 2.27 | 1.28 to 4.17 | <0.01 |

| Depersonalisation | |||

| Protective | |||

| Increasing numbers of children | 0.70 | 0.53 to 0.90 | <0.01 |

| Feeling well supported | 0.52 | 0.31 to 0.86 | 0.012 |

| Feeling the workload is manageable | 0.39 | 0.24 to 0.61 | <0.01 |

| Risk factors | |||

| History of depression/anxiety | 1.66 | 1.01 to 2.73 | 0.045 |

| At risk of alcohol misuse | 1.68 | 1.08 to 2.62 | <0.01 |

| Decreasedpersonal accomplishment | |||

| Protective | |||

| Feeling well supported | 0.51 | 0.29 to 0.78 | 0.018 |

| Increased weekly exercise | 0.85 | 0.73 to 0.98 | 0.023 |

| Risk factors | |||

| History of depression/anxiety | 1.71 | 1.05 to 2.80 | 0.031 |

Other findings

RMOs reported working a median of 50–59 hours per week. Median hours at work for registrars in medical specialties were 50–59 hours (minimum <40 hours, maximum 60–69 hours). Registrars on training programmes that do not fall under the physician or surgeon training programmes (radiology, anaesthetics, emergency medicine, etc) reported a median of 50–59 hours per week (minimum <40 hours, maximum 70–79 hours). Registrars in surgical specialties reported a median of 60–69 hours per week (minimum 50–59 hours, maximum 80+ hours). Increased hours were not independently associated with an increased incidence of burnout in this study.

Vocational, medical and surgical registrars all reported a median of 3–5 hours per week preparing for compulsory teaching. This did not include time spent conducting research or preparing for specialty examinations. Fifty-seven percent (293/509) of respondents were at risk of alcohol misuse based on the AUDIT-C screening tool.

Qualitative responses

Themes identified from qualitative responses included staffing concerns, inadequate remuneration, a focus on service provision over education, difficulty getting onto surgical training, and difficulty balancing examinations and work commitments. These themes are summarised with examples in table 4.

Table 4. Summary of qualitative responses.

| Theme | Examples |

| Poor staffing, management and resourcing | “Ongoing worsening shortage of staff - worst at the junior level, that is greatly impacting all hospitals, all departments and all current doctors… It impacts morale and is causing burnout.”“Chronic understaffing - causes difficulties within teams and for transferring care to community, with patients not being picked up.”“Overworked with inadequate staffing, even when all staff are present. Frequent vacancies with no relievers to cover night shifts, sickness, or leave.”“Under-resourced almost universally. The healthcare system is in complete disarray, and the whole system seems broken.”“Same mistakes being made in the health system in NZ as were made in Ireland 10–15 years ago.”“If the working conditions [continue to] deteriorate to a level approaching those in (Ireland/the UK), many doctors from the UK and Ireland will leave despite being permanent residents/citizens as there is no longer an incentive to stay. Australia is a realistic and attractive alternative.”“Management is entirely incompetent, changes almost monthly and is oblivious to the realities of [resident doctor] work.”“The medical registrar night shifts at our large, tertiary hospital are quite distressing to cover due to the extremely long wait that most of the patients have had in our ED by the time they are seen, and also the shortage of nurses to monitor them/commence treatment while they are in the waiting room.” |

| Inadequate support | “I feel that some of the lack of support comes from the SMOs* being burnt out.”“Unsupportive environment. Department runs by service manager who also managing other bigger departments hence the needs of my department is sacrificed.”“I feel poorly supported. Work is busy but would be manageable if better supported.”“Not having enough SMOs* in the department puts a lot of extra stress on [registrars] and takes away from our training opportunities. Te Whatu Ora really needs to focus on filling SMO* roles to maintain trainee health and encourage trainees to return as consultants.” |

| Inadequate remuneration | “Far too little pay… taking into account the training required and the nature of the work… it seems ridiculous that a doctor would struggle to pay for ordinary day-to-day expenses and yet here we are.”“I feel like my life is 99% work, hardly anything otherwise, yet financially struggling to meet day-to-day expenses, mortgage, childcare…”“I feel completely undervalued as my remuneration is a joke…Why would anyone return to the public health care system [as a consultant] under these conditions instead of working overseas or exclusively in private?”“Grossly underpaid for the hours done… it’s absolute madness & soul destroying.”“Working in Australia really opened my eyes to the pay discrepancy here.”“Income hasn't kept up with cost of living.”“The current hourly pay rates just make what is asked of us not worth it. Am seriously considering other careers.” |

| Difficulty getting on to surgical training | “I feel like my life is on hold until I get onto training and work feels like an extended job interview for the last 4 years.”“Stress about trying to get onto SET† training.”“I have previously experienced burnout as a junior registrar … Not having job security or guidance was a massive factor, as was the pressure of effectively having a multi-year job interview process [for surgical training] with little feedback and support.” |

| Balancing workload, family and examinations | “Training program not sympathetic to family needs and no good job prospects at the end of training. Makes me regret choosing medicine.”“Just feel like there’s too much to keep on top of. Working 60 hour weeks, studying 20 hour weeks for exams.”“Working full time and studying for specialty exams is verging on impossible.”“Currently studying for part 2 exams and feeling slightly resentful that my Australian counterparts work significantly fewer hours and have significantly more time for self-care and study while being paid more.”“I feel very undervalued in general… I also feel angry at the significant time (hundreds of hours!) I spend out of work studying for exams.” |

| Service provision over education and training | “Busier each day with limited learning/training opportunities due to service provision.”“95% service provision with no protected time for learning.”“Interest in junior registrars careers is very low and the focus is on service provision.”“(Specialty) training in [location] is about service provision, not about training registrars.”“No time for project work, no time to attend teaching.”“We have only had a handful of the weekly teaching sessions we are meant to have due to the high clinical workload and short staffing.” |

SMO refers to a Senior Medical Officer or Consultant Physician or Surgeon. This is equivalent to the term ‘Attending Physician’ in the United StatesUSA.

SET Training refers to any of the nine surgical training programsprogrammes overseen by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, the training body for surgeons in Australia and New Zealand.

Discussion

Our data reveal high rates of burnout among resident doctors in New Zealand. 8% of participants scored in the ‘high burnout’ category on at least one of the EE, DP, or PA dimensions. Furthermore, 48% of respondents scored in the ‘high burnout’ range for two or more dimensions. These results are consistent with recent studies of doctors in the UK National Health Service,22 the findings of a study of New Zealand orthopaedic surgery registrars,18 and a survey of 366 Australian GP registrars, of whom 75% experienced moderate to high levels of burnout using an abbreviated MBI.23

High burnout has also been documented in the New Zealand specialist workforce. Chambers et al reported a 50% prevalence of high personal burnout in a survey study of 1487 New Zealand Senior Medical Officers (consultants) using the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory.4 Their study identified independent associations between work-related burnout and female gender, working more than 14 consecutive hours or having a fair or poor health status. They also observed decreasing burnout rates with increasing age, which may be relevant to the high rates of burnout observed in our study.

In the current study, feeling well supported was protective for all three dimensions of burnout (EE, DP and PA) in resident doctors. It is unclear whether this is a causal association or if a resident doctor’s perception of ‘support’ changes when suffering from burnout syndrome. Regardless, the qualitative responses revealed a significant concern around a lack of support, with multiple individuals describing feeling inadequately supported due to poor senior medical staff morale or inadequate numbers of senior staff (table 3). This feeling of inadequate support is also concerning regarding the ability to create an effective and enjoyable learning environment. A strong theme from the qualitative data was that high service provision demands left inadequate time for learning and teaching. Not only is a focus on teaching essential to ensure New Zealand continues to train a specialist workforce of the highest standard, but these teaching and learning moments help create collegial and supportive environments that may be protective against burnout.

Despite comments in the qualitative data regarding the challenges of balancing work and home life, our survey data revealed a statistically significant association between having children and protection from DP. This is not a novel finding. A previous study of 702 German physicians, also utilising the MBI-HSS, found that having children lowers the probability of burnout in physicians, particularly in the dimensions of EE and DP.24 These findings were further supported by a study of US primary care and psychiatry residents.25 Buehrsch et al hypothesise that this association is because physicians with children are forced to leave work behind more effectively, and that physicians who are parents may spend more leisure time with their children.

In the current study, exercising frequently was protective for PA, in keeping with previously published literature on exercise and well-being, as well as increased feelings of PA.26 A systematic review on the topic found that physical activity may constitute an effective medium for the reduction of burnout.27 Empowering resident doctors to exercise more frequently may help alleviate some of the burden of burnout.

Our data show that feeling inadequately remunerated is independently associated with EE. This is in keeping with previous studies that have found that long-term care workers with high compensation levels are more likely to have low burnout levels28 and that higher perceived salary is associated with higher job satisfaction.29 Our qualitative data showed a strong theme of perceived inadequate per-hour remuneration among resident doctors (table 3).

Another theme in the qualitative data was around progression onto surgical training programmes. Junior surgical registrars applying for competitive surgical training programmes must be at least in their fourth year out of medical school (PGY4) to apply. A successful applicant would then commence training in their PGY5 year.30 These positions are highly competitive (eg, orthopaedic surgery had a 26% acceptance rate for the 2023 intake),30 and there is a single national training scheme with no alternative training bodies.30 As such, it is common for registrars to spend several further years as a junior registrar prior to being selected. This was clearly a source of stress for many respondents. However, there was no difference in burnout prevalence between junior surgical registrars and senior surgical trainees, consistent with a previous study of New Zealand orthopaedic registrars.18

A personal history of depression or anxiety was associated with burnout on all three dimensions (DP, EE, PA), and alcohol misuse was associated with an increased risk of DP. This is perhaps unsurprising. Burnout, anxiety and depression share common features, and a meta-analysis on the topic found significant associations between burnout and depression, and burnout and anxiety.7 However, the authors noted that, nevertheless, they are all ‘different and robust constructs’. In terms of alcohol misuse, an association between burnout and alcohol dependence is well established, but it is unclear whether the relationship is causal.31

This study had several limitations. First, it is possible that our results are not representative of the resident doctor population as a whole due to non-response bias. Those who responded may be more or less likely to be burnt out than those who did not respond. Second, there are inherent biases in survey studies. It is possible that resident doctors submitted answers that potentially under-reported or over-reported how they were feeling, or answers that they felt expected to submit. However, Simonetti et al found no difference between unadjusted and propensity-adjusted estimates of burnout, suggesting that workforce surveys may yield valid burnout estimates despite typically having low response rates.30 Third, as a cross-sectional study, it is difficult to establish temporality between some of the factors and the presence of burnout. Finally, the study may not have been adequately powered to detect differences in burnout between certain demographic factors.

Conclusion

Our data reveal a high prevalence of burnout in the New Zealand resident doctor workforce. Several protective and risk factors were identified. Furthermore, several key themes emerged from the qualitative data. These findings may act as a benchmark against which future studies of burnout can be measured and may inform interventions to mitigate burnout in the resident doctor workforce.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted with support from Specialty Trainees of New Zealand, a union for Resident Medical Officers (Resident Doctors) in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089034).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (reference number 23/141). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

References

- 1.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–85. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyondblue National mental health survey of doctors and medical students. 2019. [11-Nov-2021]. www.beyondblue.org.au Available. Accessed.

- 3.Taranu SM, Ilie AC, Turcu A-M, et al. Factors Associated with Burnout in Healthcare Professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14701. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192214701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers CNL, Frampton CMA, Barclay M, et al. Burnout prevalence in New Zealand’s public hospital senior medical workforce: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013947. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. 3rd. Scarecrow Education; 1997. Maslach burnout inventory; pp. 191–218. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edú-Valsania S, Laguía A, Moriano JA. Burnout: A Review of Theory and Measurement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:1780. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koutsimani P, Montgomery A, Georganta K. The Relationship Between Burnout, Depression, and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol. 2019;10:284. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103–11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein J, Grosse Frie K, Blum K, et al. Burnout and perceived quality of care among German clinicians in surgery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:525–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzq056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians’ quality of care. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11:328–42. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.11.4.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen K-Y, Yang C-M, Lien C-H, et al. Burnout, job satisfaction, and medical malpractice among physicians. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:1471–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fahrenkopf AM, Sectish TC, Barger LK, et al. Rates of medication errors among depressed and burnt out residents: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:488–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39469.763218.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017–22. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00227-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tawfik DS, Scheid A, Profit J, et al. Evidence Relating Health Care Provider Burnout and Quality of Care: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:555–67. doi: 10.7326/M19-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries N, Boone A, Godderis L, et al. The Race to Retain Healthcare Workers: A Systematic Review on Factors that Impact Retention of Nurses and Physicians in Hospitals. Inquiry . 2023;60:00469580231159318. doi: 10.1177/00469580231159318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Australian Medical Association . Barton, ACT: AMA; 2008. AMA survey report on junior doctor health and wellbeing. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gemine R, Davies GR, Tarrant S, et al. Factors associated with work-related burnout in NHS staff during COVID-19: a cross-sectional mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e042591. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martyn TLB, Savage E, MacLean SBM. An assessment of burnout in New Zealand orthopaedic resident medical officers. N Z Med J. 2022;135:11–21. doi: 10.26635/6965.5705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med . 1998;158:1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63:581–92. doi: 10.1093/biomet/63.3.581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schreier M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. 2012. pp. 1–280. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imo UO. Burnout and psychiatric morbidity among doctors in the UK: a systematic literature review of prevalence and associated factors. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41:197–204. doi: 10.1192/pb.bp.116.054247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman R, Mullan J, Bonney A. A cross-sectional study of burnout among Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:47. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Children lower the probability of burnout in physicians. [05-Apr-2024]. https://www.longdom.org/open-access/children-lower-the-probability-of-burnout-in-physicians-26235.html Available. Accessed.

- 25.Woodside JR, Miller MN, Floyd MR, et al. Observations on Burnout in Family Medicine and Psychiatry Residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32:13–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bretland RJ, Thorsteinsson EB. Reducing workplace burnout: the relative benefits of cardiovascular and resistance exercise. PeerJ. 2015;3:e891. doi: 10.7717/peerj.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naczenski LM, Vries JD de, Hooff MLM van, et al. Systematic review of the association between physical activity and burnout. J Occup Health. 2017;59:477–94. doi: 10.1539/joh.17-0050-RA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim BJ, Choi CJW. Impact of compensation and willingness to keep same career path on burnout among long-term care workers in Japan. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21:64. doi: 10.1186/s12960-023-00845-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barili E, Bertoli P, Grembi V, et al. Job satisfaction among healthcare workers in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0275334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0275334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. [04-Apr-2024]. https://www.nzoa.org.nz/sites/default/files/DH9152_NZOA_AnnualReport2022_Final.pdf Available. Accessed.

- 31.Ahola K, Honkonen T, Pirkola S, et al. Alcohol dependence in relation to burnout among the Finnish working population. Addiction . 2006;101:1438–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]