Abstract

Background

Acute kidney injury (AKI) in the context of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) encompasses a broad spectrum of phenotypes with associated disparate outcomes. We evaluate the impact of ‘ongoing AKI’ on prognosis and cardiorenal outcomes and describe predictors of ‘ongoing AKI’.

Methods

A prospective multicentre observational study of patients admitted with ADHF requiring intravenous furosemide was completed, with urinary angiotensinogen (uAGT) measured at baseline. AKI was defined using Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI criteria. AKI recovery status was defined as ‘no AKI’, ‘recovered AKI’ or ‘ongoing AKI’ based on renal function at hospital discharge. Event-free survival analysis was performed to predict death and cardiorenal outcomes at hospital discharge and 6-month follow-up. Multinomial logistic regression was performed to identify predictors of ongoing AKI. Multiclass receiver operator curve analysis was performed to evaluate the relationship between renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers and uAGT in predicting ongoing AKI.

Results

Among 271 enrolled patients, 121 (44.6%) patients developed AKI, of whom 62 patients had ongoing AKI. Ongoing AKI was associated with increased risk of death (HR 6.89, p<0.001), in-hospital end-stage kidney disease (HR 44.39, p<0.001), 6-month composite of death, transplant, left ventricular assist device and heart failure hospitalisation (HR 3.09, p<0.001), and 6-month composite major adverse kidney events (HR 5.71, p<0.001). Elevated baseline uAGT levels, chronic beta-blocker and thiazide diuretic therapy, and lack of RAS blocker prescription at recruitment were associated with ongoing AKI. While uAGT levels were lower with RAS blocker prescription, in patients with ongoing AKI, uAGT levels were elevated regardless of RAS blocker status.

Conclusion

Patients experiencing ongoing AKI during ADHF admission were at increased risk of death and other adverse cardiorenal outcomes. Differential uAGT response in patients receiving RAS blockers with ongoing AKI suggests biomarkers may be helpful in predicting treatment responses and cardiorenal outcomes.

Keywords: HEART FAILURE, Biomarkers, Heart Transplantation, Heart-Assist Devices

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Renal dysfunction increases morbidity and mortality in acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF); however, the impact of acute kidney injury (AKI) varies across trials. Similarly, there is a disparate approach to management, particularly with regard to renin-angiotensin system blockers and diuretics in the face of AKI.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study identifies ongoing AKI, a subset of acute kidney disease (AKD), as a prognostically relevant event in ADHF. Furthermore, it identifies clinical and biomarkers predicting ongoing AKI.

This study introduces the concept of biomarkers of renin-angiotensin system (RAS) activation and their interaction with RAS blockers in predicting ongoing AKI.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Ongoing AKI or AKD should be used to prognosticate ADHF patients. Future research should assess serial urinary angiotensinogen response, along with other biomarkers of RAS activation and haemodynamic status to guide titration of guideline-directed medication therapy, loop diuretics and sequential nephron blockade, administration of vasoactive medications and escalation to short-term mechanical circulatory support.

Background

Renal dysfunction in the setting of acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) is well established as an adverse prognostic marker; however, the impact of acute kidney injury (AKI) during admission remains contentious.1,7 Disparate outcomes are likely related to differing definitions of relevant kidney injury outcomes, complex pathophysiology related to heart failure, sequelae of dual organ dysfunction and comorbid conditions, and finally, differences in management in response to kidney injury. Significant research in all domains is required to understand more about cardiorenal interactions, to tailor management and prognosticate outcomes.

Kidney injury itself is a continuum, with changes in the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) AKI criteria implemented in 2012 to identify patients with functional renal impairment relative to physiological demand, as well as those with established injury.8 This is relevant in the setting of acute heart failure whereby some patients have transient fluctuations in serum creatinine (sCr) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) in response to haemodynamic shifts and medication changes, while others will have more established kidney injury. Acute kidney disease (AKD), defined as ongoing damage or loss of kidney function persisting beyond exposure to an AKI inciting event, helps to distinguish these phenotypes. Various clinical trajectories of AKD have been described, with ongoing or persistent AKI used to describe AKI that fails to recover to baseline, or repeated AKI events without return to baseline. We evaluate the impact of ongoing AKI, as a marker of established kidney injury on cardiorenal outcomes, and identify predictors of ongoing AKI.

Methods

Study design

The study protocol was approved by the sponsor hospital’s human research ethics committee (2020/ETH00702). This was a prospective observational study conducted across two tertiary cardiology services between January 2021 and November 2022. Consecutive cardiology admissions were screened for eligibility. Inclusion criteria were adult patients aged ≥18 years admitted with symptoms and signs of acute decompensation of either de novo or chronic heart failure requiring administration of intravenous furosemide. Exclusion criteria included acute renal failure at admission (sCr>354 µmol/L or acute renal replacement therapy requirement), NT-proBNP inconsistent with heart failure diagnosis (<300 ng/L as per 2021 ESC guidelines), chronic renal replacement therapy or administration of nephrotoxins including contrast, aminoglycosides or vancomycin within the 7 days prior to recruitment. Additionally, patients admitted during COVID-19 ward restrictions or who were COVID-19 positive were not included due to infection control policy. Consenting patients were then enrolled into the study.

Once enrolled, a urine sample was collected within 24 hours of admission to the cardiology ward. This was analysed for urine albumin, sodium, urea and creatinine concentrations within 24 hours of collection by the same hospital pathology service and subsequently stored in a −80°C freezer. At the conclusion of the study, frozen samples were thawed and analysed for urinary angiotensinogen (uAGT) concentration using commercially available ELISA kits (Duoset, R&D systems, MN, USA) independent of clinical data and then normalised to urinary creatinine (uAGT:Cr). Timing of last furosemide administration prior to each urine sample was categorised into <2 hours, 2–24 hours or >24 hours. Administration of other diuretics (mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists—MRA, thiazide diuretics or sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors—SGLT2i) and renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers (including ACE inhibitors—ACEI, angiotensin-II receptor blockers—ARB, angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors—ARNI) within 24 hours of the baseline sample was also recorded. Baseline demographic data, creatinine levels at admission, hospital discharge, hospital peak, minimum (up to 3 months prior admission), in addition to admission and discharge medications and echocardiogram data were collected. Six-month follow-up data was obtained for all patients including death, heart failure events such as heart failure hospitalisation, need for heart transplantation (HTx) or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation, stable outpatient sCr and need for renal replacement therapy (RRT).

Definitions

Acute kidney injury during hospital admission was defined using the KDIGO AKI criteria, as shown in table 1, adjudicated on all sCr samples taken during the hospital admission. Minimum creatinine value was defined as the nadir creatinine during the hospital admission or within the 3 months prior to hospital admission where available. Acute kidney injury recovery status was graded into ‘no AKI’, ‘recovered AKI’ whereby sCr returned to within 27 µmol of the minimum value, and ‘ongoing AKI’. eGFR was calculated using the 2021 CKD-EPI formula. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 calculated using the minimum creatinine value. End-stage kidney disease (ESKD) was defined as progression to stage V chronic kidney disease or requirement for RRT during the hospital admission. Major adverse kidney events (MAKE) were defined as a sustained drop in eGFR>50% from the hospital discharge value, progression to stage V chronic kidney disease or initiation of RRT within the 6 months following hospital discharge.

Table 1. KDIGO acute kidney injury (AKI) stages.

| Serum creatinine (sCr) change | |

| Stage 1 | Increase of ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 µmol/L) over 48 hours period orIncrease 1.5–2× over 7-day period |

| Stage 2 | Increase 2–3× over 7-day period |

| Stage 3 | Increase >3× over 7-day period orIncrease in sCr to ≥4.0 mg/dL (353.6 µmol/L) orInitiation of renal replacement therapy |

Objectives

The primary objective of the study was to establish differences in cardiorenal event-free survival according to AKI recovery status including (1) all-cause mortality at any time, (2) composite of death, urgent HTx or durable LVAD implantation during admission, (3) ESKD during admission, (4) composite of death, HTx, LVAD or heart failure hospitalisation at 6 months follow-up or (5) MAKE at 6 months follow-up. The secondary objectives of the study were to: (1) identify biomarkers and clinical parameters predicting risk of recovered and ongoing AKI compared with no AKI during hospital admission; (2) identify whether the above biomarkers and clinical parameters similarly predicted cardiorenal events in-hospital and at 6 months follow-up; and (3) conduct exploratory analysis on the interaction between RAS blockers and urinary biomarkers according to AKI recovery status.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were summarised as mean±SD or median with IQR for continuous variables based on normality, and counts with percentages for categorical data. All statistical tests were two sided, and p values <0.05 were considered significant.

Time to event analysis was performed using Kaplan Meier Survival and Cox regression analysis, with censoring for HTx, LVAD and death in all analyses.

To determine differences between AKI recovery status, univariate analysis for all baseline demographics, admission and baseline sample medications, urinary biomarker and biochemistry levels was first performed using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test for continuous and χ² test for categorical variables. All parameters with significant p value were tested using univariate multinomial logistic regression with ‘no AKI’ as the reference group. Significant univariate predictors of ongoing AKI were included in a multivariable multinomial logistic regression model showing differences in no AKI, recovered AKI and ongoing AKI.

To examine the relationship between urinary angiotensinogen and RAS blockers in discriminating AKI recovery status, multiclass receiver operator curve analysis was conducted. This method averages the area under the curve of the following scenarios: (1) No AKI (control) vs Recovered AKI (cases); (2) No AKI (control) vs Ongoing AKI (cases); (3) Recovered AKI (control) vs Ongoing AKI (cases).

Results

A total 396 patients were eligible for enrolment across both sites, with 271 patients recruited into the study, as shown in online supplemental figure 1. Of the excluded patients, 99 were unable or did not consent to the study, and a further 36 patients were discharged from hospital prior to being approached for participation. The median age was 73 years (IQR 60–83), with 82 (30.3%) participants identifying as female. Median length of stay was 8 days (IQR 4.5–14). Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (left ventricular ejection fraction LVEF <50%) comprised 60.1%, with 36.9% of the entire cohort having severe left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF <30%). Diabetes affected 100 (36.9%) participants, while 106 (39.1%) had CKD.

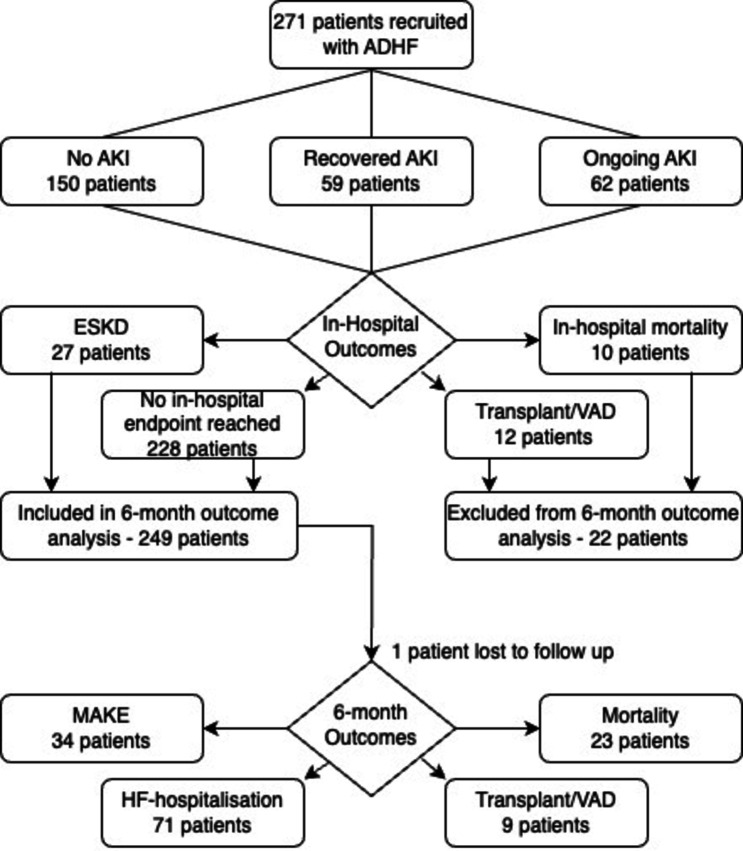

Acute kidney injury occurred in 121 patients (44.6%), with AKI grade 1 in 92 patients (33.9%), AKI grade 2 in 6 patients (2.2%) and AKI grade 3 in 23 patients (8.5%). Recovered AKI occurred in 59 patients (21.8%), while ongoing AKI occurred in 62 patients (22.9%). The overall disposition of patients is shown in figure 1. 10 patients did not survive to hospital discharge, with a further 12 patients requiring urgent HTx or LVAD implantation and 27 progressing to ESKD. Of the 248 patients with 6-month follow-up data available, a further 23 patients died, 71 patients experienced heart failure rehospitalisation, 9 patients underwent HTx or LVAD and 34 patients experienced MAKE. Baseline demographics, admission medications, serum and urine results are shown according to AKI recovery status in table 2.

Figure 1. Flowchart of outcomes in recruited patients.

Table 2. Baseline demographics and biochemistry according to AKI recovery status.

| Baseline demographics | No AKI(n=150) | Recovered AKI (n=59) | Ongoing AKI (n=62) | P value |

| Age (years) | 69.7±16.9 | 71.6±15.3 | 71.5±14.0 | 0.653 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male (n=189) | 101 (53.4) | 43 (22.8) | 45 (23.8) | ref. |

| Female (n=82) | 49 (59.8) | 16 (19.5) | 17 (20.7) | 0.630 |

| Heart failure classification | ||||

| HFpEF (n=106) | 65 (61.3) | 19 (17.9) | 22 (20.8) | ref. |

| HFrEF (n=163) | 84 (51.5) | 39 (23.9) | 40 (24.5) | 0.274 |

| Ejection fraction grade | ||||

| Normal (n=106) | 65 (61.3) | 19 (17.9) | 22 (20.8) | ref. |

| Mild (n=28) | 17 (60.7) | 4 (14.3) | 7 (25.0) | 0.870 |

| Moderate (n=35) | 19 (54.3) | 8 (22.9) | 8 (22.9) | 0.686 |

| Severe (n=100) | 48 (48.0) | 27 (27.0) | 25 (25.0) | 0.139 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| IHD (n=106) | 51 (34.0) | 25 (42.4) | 30 (48.3) | 0.136 |

| Diabetes (n=100) | 40 (26.7) | 25 (42.4) | 35 (56.5) | <0.001* |

| Hypertension (n=148) | 77 (51.3) | 31 (52.5) | 40 (64.5) | 0.201 |

| Atrial fibrillation (n=155) | 88 (58.7) | 35 (59.3) | 32 (51.6) | 0.671 |

| CKD (n=106) | 37 (24.7) | 28 (47.5) | 41 (66.1) | <0.001* |

| Admission medications | ||||

| ACEI/ARB/ARNI (n=131) | 73 (48.7) | 28 (47.5) | 30 (48.3) | 0.987 |

| Beta-blocker (n=157) | 76 (50.7) | 41 (69.5) | 40 (64.5) | 0.023* |

| Loop diuretic (n=148) | 71 (47.3) | 41 (69.5) | 36 (58.1) | 0.012* |

| MRA (n=72) | 36 (24.0) | 19 (32.2) | 17 (27.4) | 0.491 |

| Thiazide diuretic (n=21) | 7 (4.7) | 9 (15.3) | 5 (8.1) | 0.039* |

| SGLT2i (n=27) | 12 (8.0) | 10 (16.9) | 5 (8.1) | 0.128 |

| Serum and urine biochemistry | ||||

| Admission eGFR | 71.2±22.9 | 46.3±23.6 | 42.1±22.0 | <0.001* |

| Minimum eGFR | 76.7±23.1 | 60.4±26.5 | 50±25.2 | <0.001* |

| Baseline log(uAGT/Cr) | 6.49±1.97 | 7.93±2.48 | 7.62±2.53 | <0.001* |

| Baseline uNA | 88.7±33.2 | 70.6±33.1 | 72.1±35.2 | <0.001* |

| Baseline uCr | 5.02±4.86 | 4.89±4.28 | 5.55±3.58 | 0.671 |

| Baseline uUrea | 140±104 | 146±98.6 | 148±85.3 | 0.822 |

| Baseline uAlb:Cr | 30.5±90.2 | 114±513 | 86±189 | 0.122 |

| Medications within 24 hours of first urine sample | ||||

| RAS blocker (n=96) | 64 (42.6) | 12 (20.3) | 20 (32.3) | 0.008* |

| MRA (n=85) | 48 (32.0) | 18 (30.5) | 19 (30.6) | 0.967 |

| SGLT2i (n=23) | 10 (6.7) | 7 (11.9) | 6 (9.7) | 0.444 |

| Thiazide diuretic (n=15) | 4 (2.7) | 3 (5.1) | 8 (12.9) | 0.014* |

ACEIangiotensin converting enzyme inhibitorsAKIacute kidney injuryARBangiotensin-II receptor blockerARNIangiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitorCKDchronic kidney diseaseeGFRestimated glomerular filtration rateHFpEFheart failure with preserved ejectionHFrEFheart failure with reduced ejection fractionIHDischaemic heart diseaseMRAmineralocorticoid receptor antagonistRASrenin-angiotensin systemSGLT2isodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitorsuAGTCr – urinary angiotensinogen normalised to urinary creatinineuAlbCr – urine albumin:creatinine ratiouCrurine creatinineuNaurine sodiumuUreaurine urea

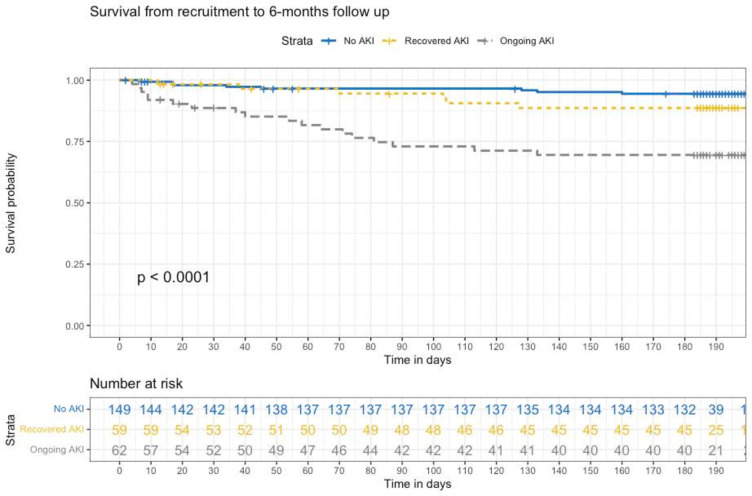

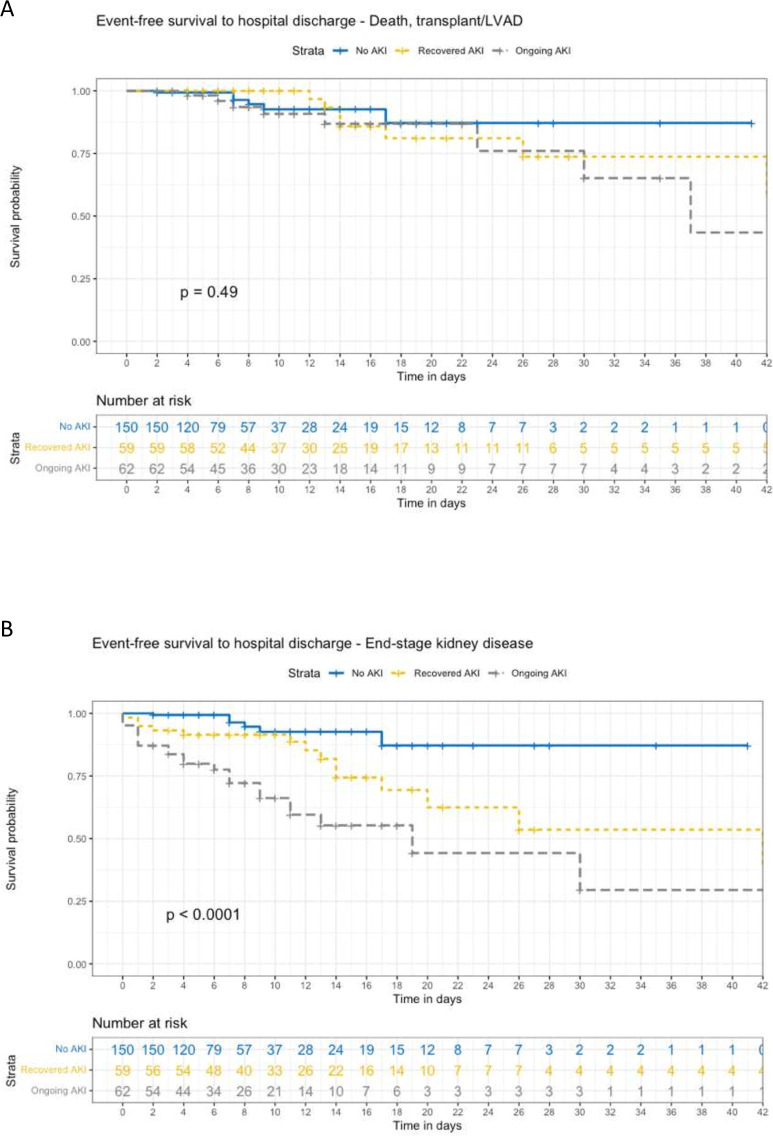

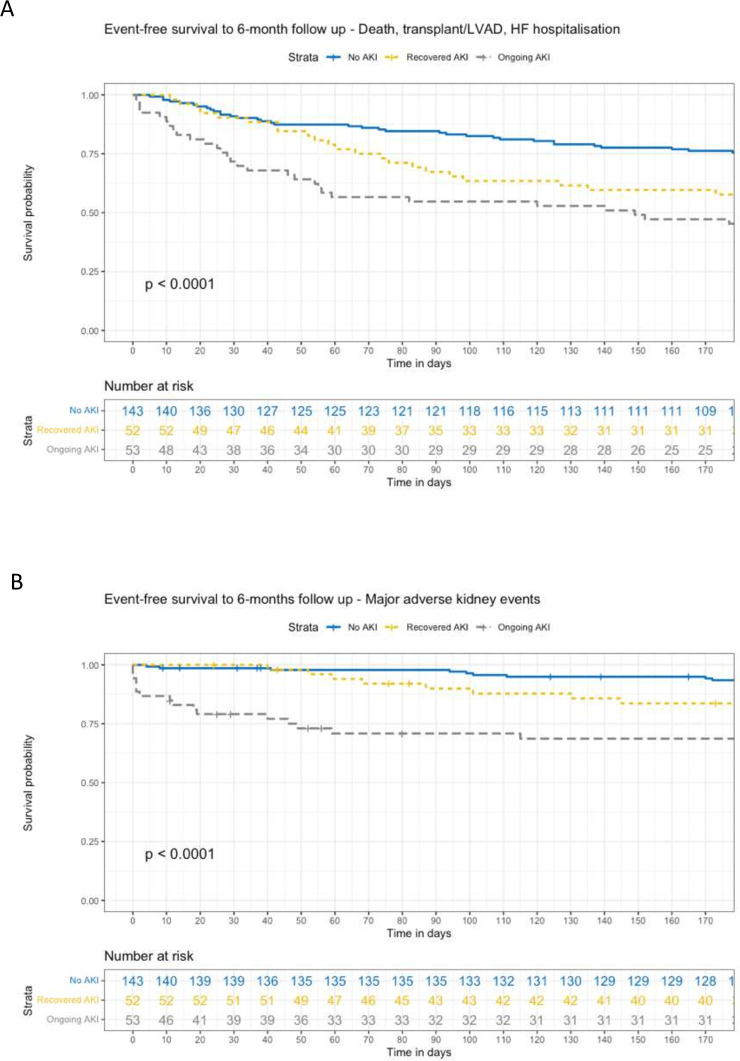

Time-to-event analysis was performed to examine the relationship between multiple cardiorenal adverse outcomes in-hospital and at 6 months follow-up, with censoring for death, HTx and LVAD. Figure 2 shows the overall survival to 6 months according to AKI recovery status. On Cox regression analysis, ongoing AKI was associated with an HR of 6.89 for mortality (95% CI 3.01 to 15.75, p<0.001), while recovered AKI was not significantly associated with mortality (table 3). Figure 3 shows time to event relationships between AKI recovery status and in-hospital events, including survival to discharge free from death, urgent HTx or LVAD, and survival to discharge free from ESKD. Figure 4 shows time to event relationship between AKI recovery and the composite of mortality, need for HTx or LVAD and heart failure hospitalisation, as well as the time to event relationship with MAKE at 6 months follow-up. Table 3 summarises the Cox hazard ratios for each adverse event according to AKI recovery status, notably showing an increased hazard for each event in those with ongoing AKI (with the exception of in-hospital composite of mortality, urgent LVAD or HTx).

Figure 2. Survival from recruitment to 6-month follow-up.

Table 3. Cox proportional hazard models for AKI recovery status and adverse cardiorenal outcomes.

| Recovered AKI | Ongoing AKI | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Overall outcomes | ||||||

| Death | 1.96 | 0.68 to 5.66 | 0.215 | 6.89 | 3.01 to 15.75 | <0.001* |

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||||

| Death, HTx/LVAD | 1.06 | 0.34 to 3.27 | 0.923 | 1.73 | 0.60 to 5.01 | 0.313 |

| End-stage kidney disease | 13.71 | 1.67 to 112.0 | 0.013* | 44.39 | 5.92 to 332.8 | <0.001* |

| Post-discharge outcomes | ||||||

| Death, HTx/LVAD, HF hospitalisation | 1.91 | 1.12 to 3.25 | 0.018* | 3.09 | 1.89 to 5.03 | <0.001* |

| Major adverse kidney event | 2.31 | 0.91 to 5.84 | 0.078 | 5.71 | 2.59 to 12.59 | <0.001* |

AKIacute kidney injuryHFheart failureHTxheart transplantationLVADleft ventricular assist device

Figure 3. Event-free survival to hospital discharge. Panel A – Composite of death, transplant and LVAD. Panel B – End-stage kidney disease.

Figure 4. Event-free survival to 6-month follow-up. Panel A – Composite of death, transplant, LVAD and heart failure hospitalisation. Panel B – Major adverse kidney events.

On univariate multinomial analysis, baseline CKD, diabetes mellitus, baseline urine sodium, log-transformed urinary angiotensinogen:creatinine (uAGT:Cr), chronic use of beta-blocker, loop diuretic or thiazide diuretic, and absence of RAS blocker within 24 hours of baseline urine sample were associated with ongoing AKI, as shown in table 4. On multivariate multinomial analysis, chronic beta-blocker and thiazide diuretic use, absence of RAS blocker within 24 hours of baseline urine sample and log-transformed uAGT:Cr significantly predicted ongoing AKI, but not recovered AKI.

Table 4. Univariate and multivariate multinomial regression model for predictors of recovered and ongoing AKI.

| UV RRR | 95% CI | P value | MV RRR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| Intercept | Recovered AKI | – | – | – | 0.24 | 0.04 to 1.66 | 0.149 |

| Ongoing AKI | – | – | – | 0.07 | 0.01 to 0.52 | 0.010* | |

| Baseline CKD | Recovered AKI | 5.96 | 3.13 to 11.35 | <0.001* | 5.39 | 2.49 to 11.66 | <0.001* |

| Ongoing AKI | 2.76 | 1.47 to 5.19 | 0.002* | 2.10 | 0.95 to 4.66 | 0.067 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Recovered AKI | 3.56 | 1.92 to 6.62 | <0.001* | 2.87 | 1.40 to 5.89 | 0.004* |

| Ongoing AKI | 2.02 | 1.08 to 3.80 | 0.029* | 2.33 | 1.10 to 4.92 | 0.027* | |

| Beta-blocker at admission | Recovered AKI | 1.77 | 0.96 to 3.26 | 0.067 | 1.47 | 0.65 to 3.34 | 0.276 |

| Ongoing AKI | 2.22 | 1.17 to 4.21 | 0.015* | 2.46 | 1.05 to 5.75 | 0.033* | |

| Loop diuretic at admission | Recovered AKI | 1.54 | 0.85 to 2.80 | 0.156 | 0.86 | 0.40 to 1.85 | 0.705 |

| Ongoing AKI | 2.53 | 1.34 to 4.81 | 0.004* | 1.38 | 0.62 to 3.09 | 0.426 | |

| Thiazide diuretic at admission | Recovered AKI | 1.79 | 0.55 to 5.88 | 0.336 | 2.99 | 0.66 to 13.50 | 0.154 |

| Ongoing AKI | 3.68 | 1.30 to 10.39 | 0.014* | 9.41 | 2.51 to 35.38 | 0.001* | |

| Baseline urinary sodium | Recovered AKI | 0.99 | 0.98 to 0.99 | 0.002* | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | 0.002* |

| Ongoing AKI | 0.98 | 0.98 to 0.99 | 0.001* | 0.98 | 0.97 to 0.99 | 0.015* | |

| Log baseline uAGT:Cr | Recovered AKI | 1.26 | 1.09 to 1.46 | 0.002* | 1.10 | 0.93 to 1.30 | 0.277 |

| Ongoing AKI | 1.35 | 1.16 to 1.57 | <0.001* | 1.26 | 1.06 to 1.51 | 0.011* | |

| RAS blocker prior first sample | Recovered AKI | 0.64 | 0.34 to 1.19 | 0.160 | 0.79 | 0.37 to 1.67 | 0.534 |

| Ongoing AKI | 0.34 | 0.17 to 0.70 | 0.003* | 0.39 | 0.17 to 0.90 | 0.027* |

AKIacute kidney injuryCKDchronic kidney diseaseMVmultivariateRASrenin-angiotensin systemRRRrelative risk ratiouAGTCrurinary angiotensinogen normalised to urine creatinineUVunivariate

The HR for the cardiorenal composite events and parameters predictive of ongoing AKI are summarised in online supplemental table 1. Importantly, although the background use of beta-blockers was associated with increased risk of ongoing AKI, their use was also associated with trend to lower risk of death, consistent with existing heart failure literature. RAS blocker use similarly remained protective against death, in-hospital progression to ESKD and 6-month MAKE. Log-transformed uAGT:Cr levels and thiazide diuretic use were associated with increased risk of death, which remained significant on multivariate analysis. Log-transformed uAGT:Cr also predicted in-hospital progression to ESKD, 6-month heart failure composite and 6-month MAKE.

In light of the above results, an exploratory analysis was conducted to investigate the differential response of uAGT:Cr to RAS blockers in the setting of ongoing AKI, as shown in online supplemental figure 2. The boxplots suggest lowers levels of log-transformed uAGT:Cr in patients without AKI (both with and without RAS blocker). In patients with recovered AKI, log-transformed uAGT:Cr levels appear elevated in patients who did not receive RAS blockers, but not in those who were treated with RAS blockers. Conversely, in patients with ongoing AKI, log-transformed uAGT:Cr levels appear elevated regardless of RAS blocker use. The multiclass average AUC for logarithm transformed uAGT:Cr was 0.63 in all patients, improving to an AUC of 0.66 in patients who had received RAS-blockers, as shown in online supplemental figure 3a . Using the non-transformed uAGT:Cr values, the multiclass average AUC was 0.61 in all patients, improving to an AUC of 0.67 in patients who had received RAS-blockers, as shown in online supplemental figure 3b.

Discussion

This study emphasises the risk of (1) all cause mortality, (2) heart failure events such as need for urgent HTx, LVAD or heart-failure hospitalisation, and (3) the risk of renal endpoints such as in-hospital end-stage kidney disease and 6-month major adverse kidney events, in patients with ongoing AKI following ADHF admission. Urinary biomarkers such as uAGT, in addition to chronic beta-blocker therapy and thiazide-diuretic use, and absence of RAS blocker administration 24 hours prior recruitment predicted ongoing AKI at hospital discharge. Urinary angiotensinogen was similarly associated with increased hazard of short-term and long-term renal adverse endpoints, with administration of RAS blockers being protective against these events.

The relationship between renal dysfunction and adverse outcomes in patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure has been extensively described. The ADHERE registry reported concomitant renal dysfunction in 60% of patients admitted with ADHF, demonstrating a graduated increase in mortality during admission according to CKD stage.3 9 Multiple subsequent trials have described the association between acute kidney injury and adverse outcomes, although with differing definitions for their renal endpoints, and associated disparity in clinical outcomes. This is confounded by the inherent 48-hour delay from renal insult to injury diagnosis based on current creatinine-based AKI criteria. Further attempts have been made to distinguish different AKI phenotypes in ADHF, with Metra et al describing the combination of AKI and congestion as mediating increased mortality risk, while Shirakabe et al described ‘true worsening renal function’ as worsening AKI throughout the course of hospital admission in an attempt to improve risk prediction models.10 11 Acute kidney disease, particularly in the form of persistent or ongoing AKI, has been associated in non-heart failure populations with significant increase in 1-year mortality. In critically ill patients experiencing stage 2 or 3 AKI, compared with 1-year mortality of 9.8% in ‘recovered AKI’ patients, those with ‘AKI relapse, no recovery’ or ‘never reversed AKI’ had 1-year mortality of 58.1% and 59.8% respectively.12

Changes in management strategy in patients with AKI are similarly disparate. To date, trials of multiple renal vasodilators, cardiac inotropes and ultrafiltration have failed to consistently show superiority over placebo or intravenous loop diuretic therapy in improving renal function.13,19 In clinical practice, the most common response to AKI is dose-reduction in heart failure therapies with registry data suggesting 61.5% of patients had their ACEI or ARB discontinued or dose-reduced in response to AKI, and administration of intravenous fluids in 46.9% of patients.20 In this registry, the impact of down-titration of heart failure therapies was increased congestion score at discharge and possible increase in mortality at 6 months, although the latter no longer remained significant following multivariate adjustment.20 It is important to note that in unselected chronic kidney disease patients, the cessation of ACEI and ARB was not associated with any difference in eGFR at 3 years.21

To address the delay to AKI diagnosis and discrepant outcomes in ADHF registries, multiple biomarkers have been studied to allow earlier diagnosis, identify the potential site or duration of injury and ideally provide insights into therapeutic options. The utility of a biomarker-based AKI diagnosis was described by Angeletti et al, who intervened with renoprotective measures in response to elevated plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) in heart failure patients, resulting in lower severity of AKI.22 Unfortunately, the most commonly described biomarkers, such as plasma and urinary NGAL, urinary kidney injury molecule 1, urinary N-acetyl beta-D-glucosaminidase and cystatin C show either variable or poor discriminatory ability to predict AKI in the setting of ADHF.23,38

Lesser studied biomarkers such as uAGT have shown promise in a limited number of studies.26 30 Angiotensinogen is cleaved by renin to form angiotensin-I, and is the rate-limiting step of the renin-angiotensin system.39 Systemic angiotensinogen is produced in the liver, and owing to its size, it does not cross the glomerular filtration barrier in normal kidneys. Thus, elevated uAGT levels in urine either represent filtration through damaged glomerular basement membrane, or increased expression from the proximal tubule in response to AKI.40 41 The presence of both renin and angiotensin-converting enzyme in the proximal tubule thus allows conversion to angiotensin-II, which then act directly on angiotensin II receptors, providing evidence of an intrarenal RAS that functions independently of systemic RAS.40 Both human and animal studies have suggested uAGT levels are suppressed by administration of RAS blockers.39 42

In our study, we identified ongoing AKI as a higher risk phenotype, confirming this was associated with short-term and long-term cardiorenal outcomes. We explored predictors of ongoing AKI, notably elevated uAGT levels, chronic beta blocker therapy, chronic thiazide use and lack of RAS blocker within 24 hours of first sample collection. Chronic beta blocker therapy was not associated with other renal or cardiac endpoints, likely reflecting chronicity of heart failure as the driver of ongoing AKI, rather than beta-blocker therapy itself. Thiazide diuretics were associated with increased mortality, but not other short-term and long-term renal endpoints. Their use in clinical practice is most common in the setting of diuretic resistance, again highlighting patients at higher risk of ongoing kidney injury. Finally, RAS blocker use appeared protective against ongoing AKI; furthermore, it reduced the risk of in-hospital and 6-month renal endpoints. This confirms findings of earlier studies suggesting that RAS blocker cessation for AKI confers adverse outcomes. In an exploratory analysis of urinary angiotensinogen and RAS blocker use, we noted improved multiclass discrimination for AKI recovery status when evaluating uAGT levels in patients treated with RAS blockers, suggesting uAGT response may be helpful in determining RAS-responsive patients, thus providing a more judicious approach to RAS blocker prescription.

There are several limitations to our study. First, this was an observational study; thus, management of AKI was left to physician discretion. As described earlier, this potentially introduces discrepancies, with some opting for less aggressive diuresis and withholding of nephrotoxins and RAS blockers, while others may more aggressively attempt volume reduction with combination of high-dose diuretics and vasodilators or inotropes, all of which impact differently on congestion and neurohumoral modulation and eventually impact on long-term outcomes. This is particularly important with RAS blocker therapy, as there may be selection bias in withholding RAS blockers in patients with baseline CKD or those already presenting with AKI. Given background RAS prescription did not predict ongoing AKI, but RAS administration at the time of recruitment was protective, we cannot determine whether pausing the prescription increased risk of ongoing AKI, or simply reflected AKI at the time of recruitment. Second, we focused on biomarkers and medications at the time of enrolment in predicting ongoing AKI. However, analysis of serial measurements may be more predictive of treatment response and mitigate the impact of variations in clinical practice. Third, our population is heterogenous, incorporating both HFrEF and HFpEF patients, although we did not find any difference in the rates of ongoing AKI between these two cohorts. We did not use all AKD trajectories described in the original consensus document in our definition of ‘ongoing AKI’, excluding the subtype of patients who had gradual decline in eGFR without ever meeting KDIGO AKI criteria.43 This subtype may experience similar adverse cardiorenal outcomes, however, is challenging to adjudicate in acute heart failure admissions, particularly as our median admission length was 8 days, thus not allowing a sufficient in-patient follow-up period to adequately capture all of these events. Furthermore, medications such as SGLT2i and RAS blockers, often introduced during the stable period of heart failure hospitalisation, are associated with transient decline in eGFR which are expected to recover in 4–6 weeks. To avoid inclusion of these patients, in our cohort, patients had to meet the initial KDIGO AKI criteria to be then categorised into ‘recovered’ or ‘ongoing AKI’. We used currently accepted serum creatinine-based definitions of renal endpoints; however, these are impacted by age and muscle mass, the latter being particularly altered in cardiac sarcopaenia. Our exploratory analysis on RAS blockers and AKI recovery status is likely underpowered; however, this signal should be explored in larger studies as it may help guide ongoing RAS blocker prescription in the context of AKI.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that ongoing AKI at hospital discharge is an important mediator of increased risk of cardiorenal events at long-term follow-up. Determinants of ongoing AKI appear driven by chronicity of heart failure, diuretic resistance and an important interaction between intrarenal RAS activation and response to RAS blockade. This relationship should be further studied in animal and human models, and if confirmed, may provide a biomarker-based treatment algorithm with respect to RAS blocker prescription in decompensated heart failure patients experiencing acute kidney injury.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Alyssa Lochrin and David Humphries for their assistance in biobanking and analysis of urine specimens, and the ward staff at both study sites for facilitating sample acquisition.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by St Vincent’s Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee - 2020/ETH00702. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Requests for data sharing will need to be approved by the human research ethics committee.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Damman K, Valente MAE, Voors AA, et al. Renal impairment, worsening renal function, and outcome in patients with heart failure: an updated meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:455–69. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berra G, Garin N, Stirnemann J, et al. Outcome in acute heart failure: prognostic value of acute kidney injury and worsening renal function. J Card Fail. 2015;21:382–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heywood JT, Fonarow GC, Costanzo MR, et al. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and its impact on outcome in 118,465 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a report from the ADHERE database. J Card Fail. 2007;13:422–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horiuchi YU, Wettersten N, Veldhuisen D van, et al. Potential Utility of Cardiorenal Biomarkers for Prediction and Prognostication of Worsening Renal Function in Acute Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2021;27:533–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okubo Y, Sairaku A, Morishima N, et al. Increased Urinary Liver-Type Fatty Acid-Binding Protein Level Predicts Worsening Renal Function in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. J Card Fail. 2018;24:520–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCallum W, Tighiouart H, Testani JM, et al. Acute Kidney Function Declines in the Context of Decongestion in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:537–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wettersten N, Horiuchi Y, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide trend predicts clinical significance of worsening renal function in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1553–60. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Section 1: Introduction and Methodology. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:13–8. doi: 10.1038/kisup.2011.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, Blair JEA, et al. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Classification, Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Strategies: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e840–78. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metra M, Davison B, Bettari L, et al. Is worsening renal function an ominous prognostic sign in patients with acute heart failure? The role of congestion and its interaction with renal function. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:54–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.963413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shirakabe A, Hata N, Kobayashi N, et al. Worsening renal failure in patients with acute heart failure: the importance of cardiac biomarkers. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6:416–27. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kellum JA, Sileanu FE, Bihorac A, et al. Recovery after Acute Kidney Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:784–91. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0799OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Massie BM, O’Connor CM, Metra M, et al. Rolofylline, an Adenosine A 1 −Receptor Antagonist, in Acute Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1419–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triposkiadis FK, Butler J, Karayannis G, et al. Efficacy and safety of high dose versus low dose furosemide with or without dopamine infusion: the Dopamine in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure II (DAD-HF II) trial. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teerlink JR, Metra M, Felker GM, et al. Relaxin for the treatment of patients with acute heart failure (Pre-RELAX-AHF): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-finding phase IIb study. The Lancet. 2009;373:1429–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60622-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metra M, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, et al. Effects of Serelaxin in Patients with Acute Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:716–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bart BA, Goldsmith SR, Lee KL, et al. Ultrafiltration in Decompensated Heart Failure with Cardiorenal Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2296–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen HH, Anstrom KJ, Givertz MM, et al. Low-dose dopamine or low-dose nesiritide in acute heart failure with renal dysfunction: the ROSE acute heart failure randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2533–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giamouzis G, Butler J, Starling RC, et al. Impact of dopamine infusion on renal function in hospitalized heart failure patients: results of the Dopamine in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure (DAD-HF) Trial. J Card Fail. 2010;16:922–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.07.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boulos J, Darawsha W, Abassi ZA, et al. Treatment patterns of patients with acute heart failure who develop acute kidney injury. ESC Heart Fail. 2019;6:45–52. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bhandari S, Mehta S, Khwaja A, et al. Renin-Angiotensin System Inhibition in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2021–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2210639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angeletti S, Fogolari M, Morolla D, et al. Role of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin in the Diagnosis and Early Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury in a Case Series of Patients with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Case Series. Cardiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3708210. doi: 10.1155/2016/3708210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shirakabe A, Hata N, Kobayashi N, et al. Serum heart-type fatty acid-binding protein level can be used to detect acute kidney injury on admission and predict an adverse outcome in patients with acute heart failure. Circ J. 2015;79:119–28. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-14-0653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shirakabe A, Hata N, Kobayashi N, et al. Clinical Usefulness of Urinary Liver Fatty Acid-Binding Protein Excretion for Predicting Acute Kidney Injury during the First 7 Days and the Short-Term Prognosis in Acute Heart Failure Patients with Non-Chronic Kidney Disease. Cardiorenal Med. 2017;7:301–15. doi: 10.1159/000477825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verbrugge FH, Dupont M, Shao Z, et al. Novel urinary biomarkers in detecting acute kidney injury, persistent renal impairment, and all-cause mortality following decongestive therapy in acute decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2013;19:621–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang X, Chen C, Tian J, et al. Urinary Angiotensinogen Level Predicts AKI in Acute Decompensated Heart Failure: A Prospective, Two-Stage Study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;26:2032–41. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014040408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dankova M, Minarikova Z, Danko J, et al. Novel biomarkers for prediction of acute kidney injury in acute heart failure. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2020;121:321–4. doi: 10.4149/BLL_2020_050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray PT, Wettersten N, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Utility of Urine Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin for Worsening Renal Function during Hospitalization for Acute Heart Failure: Primary Findings of the Urine N-gal Acute Kidney Injury N-gal Evaluation of Symptomatic Heart Failure Study (AKINESIS) J Card Fail. 2019;25:654–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sokolski M, Zymliński R, Biegus J, et al. Urinary levels of novel kidney biomarkers and risk of true worsening renal function and mortality in patients with acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:760–7. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Yang X, Lei Y, et al. Urinary Biomarkers at the Time of AKI Diagnosis as Predictors of Progression of AKI among Patients with Acute Cardiorenal Syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1536–44. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00910116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alvelos M, Pimentel R, Pinho E, et al. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in the diagnosis of type 1 cardio-renal syndrome in the general ward. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:476–81. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06140710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Breidthardt T, Socrates T, Drexler B, et al. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin for the prediction of acute kidney injury in acute heart failure. Crit Care. 2012;16:R2. doi: 10.1186/cc10600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Damman K, Valente MAE, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Plasma Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin and Predicting Clinically Relevant Worsening Renal Function in Acute Heart Failure. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1470. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald S, Arendts G, Nagree Y, et al. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL) predicts renal injury in acute decompensated cardiac failure: a prospective observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang C-H, Chang C-H, Chen T-H, et al. Combination of Urinary Biomarkers Improves Early Detection of Acute Kidney Injury in Patients With Heart Failure. Circ J. 2016;80:1017–23. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atici A, Emet S, Cakmak R, et al. Type I cardiorenal syndrome in patients with acutely decompensated heart failure: the importance of new renal biomarkers. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:3534–43.:15180. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201806_15180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Palazzuoli A, Ruocco G, Pellegrini M, et al. Comparison of Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin Versus B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and Cystatin C to Predict Early Acute Kidney Injury and Outcome in Patients With Acute Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad T, Jackson K, Rao VS, et al. Worsening Renal Function in Patients With Acute Heart Failure Undergoing Aggressive Diuresis Is Not Associated With Tubular Injury. Circulation. 2018;137:2016–28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kobori H, Alper AB, Jr, Shenava R, et al. Urinary angiotensinogen as a novel biomarker of the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system status in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2009;53:344–50. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.123802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobori H, Ozawa Y, Suzaki Y, et al. Young Scholars Award Lecture: Intratubular angiotensinogen in hypertension and kidney diseases. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:541–50. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsusaka T, Niimura F, Shimizu A, et al. Liver angiotensinogen is the primary source of renal angiotensin II. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1181–9. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011121159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sachetelli S, Liu Q, Zhang S-L, et al. RAS blockade decreases blood pressure and proteinuria in transgenic mice overexpressing rat angiotensinogen gene in the kidney. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1016–23. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chawla LS, Bellomo R, Bihorac A, et al. Acute kidney disease and renal recovery: consensus report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13:241–57. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.