Abstract

Vnd/NK-2 protein was detected in 11 neuroblasts per hemisegment in Drosophila embryos, 9 medial and 2 intermediate neuroblasts. Fragments of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene were inserted upstream of an enhancerless βgalactosidase gene in a P-element and used to generate transgenic fly lines. Antibodies directed against Vnd/NK-2 and β-galactosidase proteins then were used in double-label experiments to correlate the expression of β-galactosidase and Vnd/NK-2 proteins in identified neuroblasts. DNA region A, which corresponds to the −4.0 to −2.8-kb fragment of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene was shown to contain one or more strong enhancers required for expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in ten neuroblasts. DNA region B (−5.3 to −4.0 kb) contains moderately strong enhancers for vnd/NK-2 gene expression in four neuroblasts. Hypothesized DNA region C, whose location was not identified, contains one or more enhancers that activate vnd/NK-2 gene expression only in one neuroblast. These results show that nucleotide sequences in at least three regions of DNA regulate the expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene, that the vnd/NK-2 gene can be activated in different ways in different neuroblasts, and that the pattern of vnd/NK-2 gene expression in neuroblasts of the ventral nerve cord is the sum of partial patterns.

Keywords: homeobox‖Drosophila

Fertilization of a Drosophila egg initiates 13 rounds of nuclear division, resulting in an embryo that consists of a syncytium of 5,000 to 6,000 nuclei. Before cellularization, two gene networks, one functioning in the antero-posterior axis and a second functioning in the dorso-ventral axis, initiate regulatory cascades that regulate the unique identity of each of 30 neuroblasts (NBs) in each hemisegment. By the time NBs form, segment polarity genes define the identity of each NB in the antero-posterior axis. Extrinsic signaling and intrinsic regulators including the transcription factor Dorsal, the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF) ligand Spitz, and the Bmp-4 family member Dpp, establish expression domains of three homeodomain proteins that in turn establish unique NB identities in the dorso-ventral axis.

Neural pathways of development are initiated independently in three longitudinal columns of neuroectodermal cells along the dorso-ventral axis of the central nervous system. The ventral nervous system defective (Vnd/NK-2) homeodomain protein (1–3) initiates neural development in the ventral (i.e., medial) portion of neuroectoderm (4), and Intermediate neuroblast defective (Ind) homeodomain protein initiates neural development in the intermediate column of neuroectoderm (5, 6). The mechanism of initiating neural development in the dorsal neuroectoderm column has not been identified; however, Muscle segment homeodomain (Msh) is expressed in the dorsal column of neuroectoderm and is required for specification of some dorsal neuroblasts (7, 8). The segmentation genes, wingless (9), gooseberry distal (10), and hedgehog (11) function in the neuroectoderm to specify the identity of neuroblasts along the anterior–posterior axis of the embryo. Vertebrate homologs of vnd/NK-2, ind, and msh, such as mouse NKx-2.2, Gsh, and Msx, respectively, also are expressed in ventral, intermediate, and dorsal columns in the neural tube (5, 6, 12–14). Vnd/NK-2 homeodomain protein initiates neural development in the ventral neuroectoderm by activating the proneural gene achaete (4). Vnd/NK-2 also probably functions as part of the molecular address of ventral neuroectodermal cells. Vnd/NK-2 also is required for delamination and specification of NBs derived from the ventral column of neuroectodermal cells (15).

The vnd/NK-2 gene is activated initially by Dorsal protein (16). Twist is a coactivator of the vnd/NK-2 gene (16); whereas, Snail represses vnd/NK-2 in the mesoderm (16). Vnd/NK-2 protein, directly or indirectly, promotes the continued expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene (15, 17). Single-minded represses the vnd/NK-2 gene in the mesectoderm (16), mediated by an unidentified repressor (18). Vnd/NK-2 homeodomain protein represses ind (5) and msh (15, 19). Ind also represses vnd/NK-2.§

Transplantation of dorsal neuroectodermal cells to the ventral neuroectoderm converts the developmental fate of the transplanted cells to that of ventral neuroectoderm (20), and the change in developmental fate requires functional Drosophila EFG receptors (21). EGF receptors are activated by Spitz protein (22) secreted from neighboring ventral midline mesectodermal cells (23) and/or secreted Vein protein (24). The EGF receptor is a tyrosine protein kinase; activation of the EGF receptor by Spitz or Vein activates the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, which triggers the activation of a protein kinase cascade and results in the entrance of activated mitogen-activated protein kinase into the nucleus, which modulates gene expression by catalyzing the phosphorylation of transcription factors (for review, see ref. 25). These and other results (26–28) suggest that the vnd/NK-2 gene also is activated by an unknown mechanism mediated by EGF receptors of ventral neuroectodermal cells, via the Ras–mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. In contrast, ventral neuroectodermal cells transplanted to dorsal neuroectoderm continue to develop autonomously as ventral neuroblasts (20).

We have been studying regulation of vnd/NK-2 gene expression to determine how a pattern of NBs is formed in the central nervous system. Previously, segments of DNA from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene were ligated to an enhancerless β-galactosidase (β-gal) reporter gene in a P-element vector and used to generate transgenic lines of flies (17). The −8.4/+0.35-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene was shown to contain the sequences needed for expression of β-galactosidase (β-Gal) in a pattern similar to that of Vnd/NK-2; whereas a −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA fragment expressed β-Gal in a pattern that was similar to that of Vnd/NK-2 in the ventral nerve cord, but expression was lacking in some cephalic neuroectodermal cells or NBs (17). Smaller fragments of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene did not regulate β-Gal expression in the pattern expected for Vnd/NK-2 (17). Estes et al. (18) recently reported the ligation of fragments of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene to a β-gal reporter gene in a P-element and showed in transgenic flies that Single-minded (Sim) represses the vnd/NK-2 gene indirectly, mediated by an unidentified repressor that binds to one or more nucleotide sequences in DNA between −3.6 and −3.1 kb in the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene. In addition, they showed that three regions of DNA in the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, −5.3/−4.2, −4.2/−3.1, and −3.1/−2.8 kb, are required for vnd/NK-2 gene expression (18).

In this report, information is provided on the identification of NBs that express Vnd/NK-2 homeodomain protein and on regions of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene involved in regulation of vnd/NK-2 gene expression in specific NBs. Preliminary reports of some of these results were presented previously.¶,‖

Materials and Methods

Fly Strains.

All fly stocks were maintained under standard culture conditions. Their sources were as follows: Δ2–3 Sb/Ser was obtained from Akira Chiba, hkb5953 from Krishna M. Bhat, Emory University (29), and wingless-lacZ (wg-lacZ) and engrailed-lacZ (en-lacZ) from Judith A. Kassis, National Institutes of Health.

Preparation of DNA Constructs.

The following five DNA fragments from the 5-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, −5.3 to −2.8 kb, −5.3 to −3.5 kb, −5.3 to −4 kb, −4.7 to −2.8 kb, and −4.0 to −2.8 kb, were subcloned into a P-element vector, pCaSpeRhs43lacZ (30) containing an enhancerless lacZ reporter gene, by using EcoRI and BamHI restriction sites, respectively. The −5.3 kb to −2.8-kb fragment was generated by digestion with restriction enzymes; the other four fragments were synthesized by PCR. The primers for PCR were as follows: −5.3 to −3.5-kb construct, 5′-CGACAGGCATTTTGAATTCAAGTCTCCGTTTG-3′ and 5′-CGGGATCCCCGGAAATGCATCATTACCTATG-3′; −5.3 to −4-kb construct, 5′-CGACAGGCATTTTGAATTCAAGTCTCCGTTTG-3′ and 5′-CGCGGATCCACCTTTAAGATGCGAATGTACTG-3′; −4.7 to −2.9-kb construct, 5′-CGGAATTCACTAAACTCAGTTGACCAACTGACC-3′ and 5′-GAGTCCGCATTAGGATCCTTCCTACACAGTTAG-3′; −4.0 to −2.9-kb construct, 5′-CGGAATTCCCTTTTTGACTTTTATACAGCACGG-3′ and 5′-GAGTCCGCATTAGGATCCTTCCTACACAGTTAG-3′. All constructs were purified by equilibrium centrifugation in CsCl-ethidium bromide gradients.

Preparation of Transgenic Fly Lines.

P-element constructs containing vnd/NK-2 5′-flanking region DNA fragments of −5.3 to −2.8 kb, −5.3 to −3.5 kb, −5.3 to −4.0 kb, −4.7 to −2.8 kb, and −4.0 to −2.8 kb were injected (1 μg/μl) into Δ2–3 Sb/Ser embryos to generate transgenic Drosophila lines. Transgenic lines are named −5.3/−2.8, −5.3/−3.5, −5.3/−4.0, −4.7/−2.8, and −4.0/−2.8, according to the vnd/NK-2 5′-flanking DNA fragment carried by the P-element in the Drosophila genome. Each P-element insertion was mapped to a chromosome and made homozygous.

Immunohistochemistry.

The embryos from each transgenic fly line were collected and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS. The embryos were stained first with rabbit antibody against Vnd/NK-2 full-length protein (1/500 dilution) and then with mouse monoclonal antibody against β-Gal (Promega) (1:100 dilution). The embryos then were stained with CyTM5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:100-fold dilution) and fluorescein-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:100 fold dilution) (Jackson ImmunoResearch). The embryos were washed with PBT (PBS, 0.1% BSA, and 0.1% Tween 20) before and after incubation with each antibody (15 min per wash, four washes) at room temperature and then incubated in PBT plus 0.5% normal goat serum for 30 min at room temperature before application of each antibody. Double-stained embryos were preserved in Vectorshield anti-fading medium (Vector Laboratories), and examined by using a Zeiss LSM 410 confocal microscope.

Results and Discussion

Identification of Neuroblasts That Express vnd/NK-2.

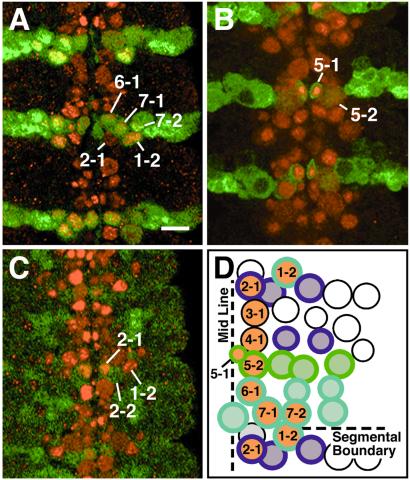

The vnd/NK-2 gene is expressed initially in the Drosophila embryo during the 12th nuclear doubling (stage 4) in two longitudinal stripes of nuclei, each stripe about five nuclei in width (16). Each Vnd/NK-2 positive stripe of nuclei identifies the ventral (i.e., medial) column of neuroectoderm (2, 3, 16). At late stage 8, the first NBs delaminate from the neuroectoderm layer. The vnd/NK-2 gene is expressed in all medial NBs. The expression of Vnd/NK-2 in neuroectoderm is narrowed progressively, and by completion of neuroblast formation (late stage 11), expression is restricted to the ventral column of neuroectodermal cells. Some NBs that express the vnd/NK-2 gene were identified in previous studies (15, 16). Antibody double-label studies on the identity of NBs that express the vnd/NK-2 gene are shown in Fig. 1. Transgenic fly lines that express β-Gal protein in identified NBs (31), such as en-lacZ, wg-lacZ, and hkb5953, were used with an antibody directed against β-Gal, whereas an antibody against full-length Vnd/NK-2 protein was used to detect Vnd/NK-2 protein. Vnd/NK-2 protein was detected in all medial NBs; NBs 1-1, MP-2, 5-2, and 7-1 in late stage 8 and early stage 9 embryos (data not shown). Vnd/NK-2 expression in NB 1-1 is weaker than in other NBs and disappears by stage 11. In addition, NB MP-2 disappears by stage 11. The en-lacZ embryo shown in Fig. 1A expressed β-Gal (green) in the cytoplasm and nuclei of cells in the Engrailed pattern in the posterior compartment, whereas Vnd/NK-2 protein in NBs, located mostly in nuclei, is shown in red. NBs that express both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins were identified by their position and by comparison with previous studies (15, 16) as 1-2, 6-1, 7-1, and 7-2. As shown in Fig. 1B, incubation of wg-lacZ embryos with anti-Vnd/NK-2 and anti β-Gal antibodies revealed two NBs per hemisegment that contained both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins, a small cell that will become NB 5-1, and NB 5-2. Hkb-lacZ has been shown to be expressed in NBs 2-1, 2-2, 2-4, 4-2, and 5-4 during stage 11 (32). As shown in Fig. 1C, only one NB, 2-1, contained both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins per hemisegment in an hkb5953 embryo. Neuroblasts that express vnd/NK-2 mRNA were identified previously by in situ hybridization (15, 16). Mellerick and Nirenberg (16) reported that most medial NB contained relatively high amounts of vnd/NK-2 mRNA, whereas some intermediate or dorsal NBs contained much lower amounts of vnd/NK-2 mRNA. In this report, an antibody directed against Vnd/NK-2 protein was used rather than RNA hybridization, and fewer intermediate and no dorsal NBs that contain Vnd/NK-2 were found. For example, NBs 2-2, 3-2, 4-2, 6-2, 7-3, and 7-4 previously were found to contain Vnd/NK-2 mRNA (16), but we did not detect Vnd/NK-2 protein in these NBs with an antibody to Vnd/NK-2. Chu et al. (15), using a vnd/NK-2 mRNA hybridization assay, also reported that NBs 2-2 and 6-2 contain vnd/NK-2 mRNA.

Figure 1.

Identification of Vnd/NK-2 expressing NBs in the ventral nerve cord. To identify the NBs expressing Vnd/NK-2, the enhancer trap NB marker Drosophila lines en-lacZ, wg-lacZ, and hkb5953 were used. In each line, β-Gal is expressed in identified NBs. Antibodies to Vnd/NK-2 protein (red) and β-Gal protein (green) were used for double staining. (A) Double-stained en-lacZ embryo at stage 11; β-Gal is expressed in the engrailed pattern in posterior compartment cells. NBs 1-2, 6-1, 7-1, and 7-2 were shown to express both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins. The bar corresponds to 5 μm. (B) Double-stained wg-lacZ embryo at stage 11; NBs 5-1 and 5-2 are Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal positive. (C) Double-stained hkb5953 embryo at stage 11; only NB 2-1 contains both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins. (D) Schematic summary of the identity of Vnd/NK-2 positive NBs. At stage 11, the following nine NBs (orange centers) were identified that are Vnd/NK-2 positive per hemisegment: 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, 7-1, and 7-2. MP-2 and 1-1 also express Vnd/NK-2 earlier in development and are not shown here. Light blue, en-lacZ positive NBs; green, wg-lacZ positive NBs; purple, hkb5953 positive NBs (29).

A summary of the nine NBs per hemisegment that express Vnd/NK-2 protein at stage 11, 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, 7-1, and 7-2 is shown in Fig. 1D. In addition, NB MP-2 expresses Vnd/NK-2 earlier in development, and NB 1-1 also transiently expresses Vnd/NK-2. Nine of the 11 NBs that express Vnd/NK-2 homeodomain protein are medial NBs; two, 1-2 and 7-2, are intermediate NBs.

Expression of β-Gal in Neuroectoderm Cells and NBs Directed by the −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA Fragment from the 5′-Upstream Region of the vnd/NK-2 Gene.

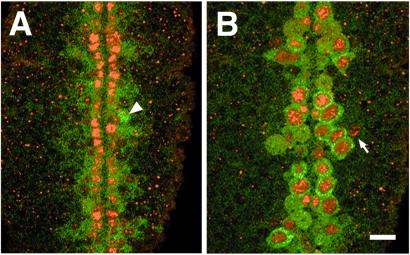

Transgenic lines of flies were generated that contain the −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA fragment from the vnd/NK-2 gene ligated to an enhancerless β-gal gene. The patterns of expression of Vnd/NK-2 protein resulting from endogenous vnd/NK-2 gene expression and β-Gal in the neuroectoderm cell layer of a stage 11 embryo (Fig. 2A) are compared with the patterns of expression in the adjacent neuroblast layer (Fig. 2B). At stage 11, Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins are expressed in a medial column of neuroectodermal cells, 1 cell wide on each side of the ventral mesectoderm (Fig. 2A). The level of expression of β-Gal in neuroectodermal cells (Fig. 2A) was much lower than that of NBs (Fig. 2B), and some ectopic expression of β-Gal was found in adjacent neuroectodermal cells (not shown in Fig. 2A). Relatively low expression of β-Gal in neuroectodermal cells also was found at earlier stages of development (not shown). The pattern of β-Gal expression directed by the −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene was similar to the pattern of Vnd/NK-2 protein directed by the endogenous vnd/NK-2 gene; however, β-Gal expression was not detected in NB 7-2 (Fig. 2B) and in some NBs in the cervical region (not shown). These results show that the −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene is sufficient to regulate Vnd/NK-2 expression in most, but not all, NBs that express Vnd/NK-2 and suggests that additional regulatory regions in DNA may be required for expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in the neuroectoderm, NB 7–2, and in some cervical NBs.

Figure 2.

Endogenous Vnd/NK-2 expression. β-Gal expression regulated by the −5.3/+0.35-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene in neuroectoderm compared with NBs. Red, Vnd/NK-2 protein; green, β-Gal protein. (A) Neuroectoderm layer of a double-labeled embryo at early stage 11. A column of neuroectodermal cells, one cell wide, that contain NK-2 protein is seen on each side of the mesectoderm. The arrowhead points to an NB that is close to the neuroectoderm layer (possibly 6-1) that has a higher level of β-Gal expression than that of neuroectodermal cells. (B) NB layer of double-labeled embryo; β-Gal expression pattern (green), directed by vnd/NK-2 (−5.3/+0.35)-β-gal construct almost completely overlaps the endogenous Vnd/NK-2 pattern; however, Vnd/NK-2 but not β-Gal was expressed in NB 7-2 (arrow). The bar corresponds to 5 μm.

Regulatory DNA Required for Vnd/NK-2 Pattern Formation.

The −5.3 to +0.35-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene was shown to contain most of the nucleotide sequences that are required to generate the normal pattern of Vnd/NK-2 expression in NBs in the embryonic ventral nerve cord, whereas transgenic embryos containing a −2.8 to +0.35-kb DNA fragment did not express β-Gal (17). This suggested that major enhancers for Vnd/NK-2 expression in NBs of the ventral nerve cord are located in a 2.5-kb region of DNA, between −5.3 and −2.8 kb. Smaller fragments of DNA within this 2.5-kb segment of DNA were prepared and subcloned in the P-element vector, pCaspeRhs43lacZ in the 5′-flanking region of the enhancerless β-gal gene. Twenty-four transgenic lines were generated: five for the −5.3 to −2.8-kb DNA fragment (named −5.3/−2.8), two for the −4.7/−2.8 fragment, five containing the −4.0/−2.8 fragment, seven carrying the −5.3/−3.5 fragment, and five lines carrying the −5.3/−4.0 fragment.

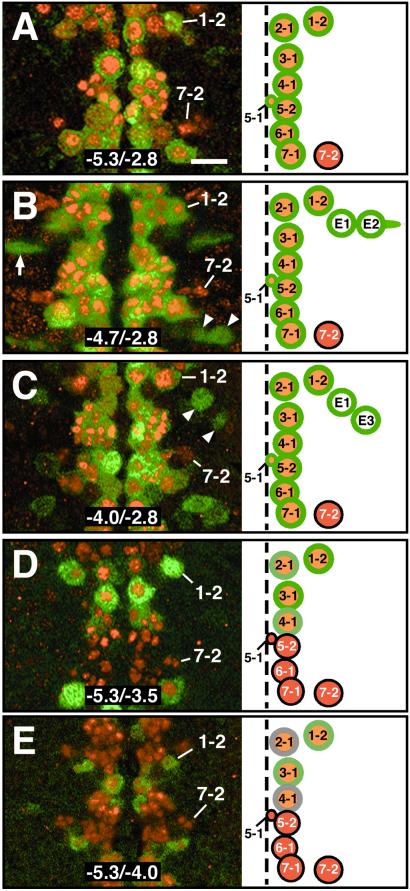

Antibodies directed against Vnd/NK-2 or β-Gal proteins were used for double labeling of transgenic embryos. As shown in Fig. 3A, a stage 11 transgenic embryo with a wild-type vnd/NK-2 gene and the −5.3/−2.8 kb of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene ligated in the 5′-flanking region of the β-gal gene expressed Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins in NBs 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, and 7-1. Vnd/NK-2 protein, but not β-Gal, was expressed in NB 7-2. The −5.3/−2.8-kb fragment of DNA also contains sequences required for the expression of β-Gal earlier in development in NB MP-2 and for transient expression in NB 1-1. Additional small cells that express both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal proteins in Fig. 3A are ganglion mother cells and/or neural progeny of NBs. Similar results were obtained with transgenic Drosophila lines −4.7/−2.8 (Fig. 3B) and −4.0/−2.8 (Fig. 3C); however, ectopic expression of β-Gal was observed in two cells (E1 and E2) in more lateral positions than medial NBs, aligned with transverse NB row 2 or 3 (Fig. 3B). In a transgenic embryo with a −4.0/−2.8-kb DNA fragment inserted in the chromosome (Fig. 3C), ectopic expression of β-Gal also was observed in two cells per hemisegment, E1 and E3; E3 is aligned with transverse NB row 3. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 3D, β-Gal was expressed strongly in only two NBs per hemisegment (NB 1-2 and NB 3-1) and weakly in NBs 2-1 and 4-1 in a transgenic embryo with a −5.3/−3.5-kb DNA insert. Weaker β-Gal expression was observed in NBs 1-2, 3-1, 2-1, and 4-1 in a transgenic embryo with a −5.3/−4.0-kb DNA insert (Fig. 3E) compared with β-Gal expression shown in Fig. 3D. However, expression of β-Gal in NBs 1-2 and 3-1 in the −5.3/−4.0 embryo (Fig. 3E) was higher than expression in NB 2-1 and NB 4-1.

Figure 3.

Regulatory DNA required for Vnd/NK-2 pattern formation in NBs. Fragments of DNA from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, subcloned in the 5′-flanking region of an enhancerless β-gal gene in a P-element, were used to generate transgenic lines of Drosophila. Antibodies directed against Vnd/NK-2 protein (red) or β-Gal (green) were used to double-label NBs in the ventral nerve cord of stage 11 transgenic embryos. The neuroblasts are identified in the panels on the right. An NB with an orange center surrounded by a green ring expressed both Vnd/NK-2 and β-Gal. An NB that expressed Vnd/NK-2, but not β-Gal, is shown in red. Cells that ectopically express β-Gal are shown with white centers surrounded by green. (A) β-Gal expression regulated by the −5.3/−2.8-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene in a transgenic embryo. The bar corresponds to 5 μm. (B) β-Gal expression regulated by the −4.7/−2.8-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene. The arrow and arrowheads indicate cells (E1 and E2) that ectopically express β-Gal. (C) β-Gal expression regulated by the −4.0/−2.8-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene. Arrowheads indicate the ectopic expression of β-Gal in E1 and E3 cells. (D) β-Gal expression regulated by the −5.3/−3.5-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene. β-Gal is expressed strongly in two NB, 1-2 and 3-1, and weakly in NB 2-1 and NB 4-1. (E) β-Gal expression directed by the −5.3/−4.0-kb DNA fragment from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene in a transgenic embryo. The four NBs that express both β-Gal and Vnd/NK-2 shown in D also express both proteins in E; however, β-Gal expression in the embryo shown in E is weaker than the expression shown in D. The levels of expression of β-Gal in NBs 1-2 and 3-1 are greater than the expression found in NBs 2-1 and 4-1.

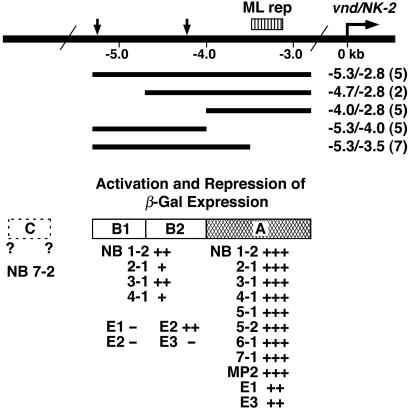

A summary of results is shown in Fig. 4. The fragments of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene are shown that were inserted upstream of an enhancerless β-gal gene in the P-element used to generate transgenic fly lines. The boxes represent regions of DNA required for the expression of β-Gal and Vnd/NK-2 proteins in NBs that normally express Vnd/NK-2 from the endogenous vnd/NK-2 gene as well as DNA regions involved in activation and repression of ectopic expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene. DNA region A, which corresponds to the −4.0 to −2.8-kb fragment of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, contains one or more strong enhancers that are required for expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in nine medial and one intermediate (1-2) NBs as follows: 1-1 (transient expression), 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, MP-2, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, and 7-1. DNA region B, which extends from −5.3 to −4.0 kb of DNA from the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, contains one or more enhancers of moderate strength for vnd/NK-2 gene expression in NBs 1-2 and 3-1 and weaker expression in NBs 2-1 and 4-1. One or more enhancers that activate vnd/NK-2 gene expression in NB 7-2 resides elsewhere in DNA (hypothesized DNA region C) whose location has not been identified. Ectopic expression of the β-gal gene was detected in three large cells per hemisegment, possibly NBs, termed E1, E2, and E3. DNA region A contains one or more nucleotide sequences involved in activation of ectopic expression of the β-gal gene in E1 and E3, whereas DNA region B2 (−4.7/−4.0 kb) contains nucleotide sequences involved in ectopic activation of the β-gal gene in E2 and repression of the gene in E3. DNA region B1 (−5.3/−4.7 kb) contains nucleotide sequences that repress ectopic expression of the β-gal gene in E1 and E2.

Figure 4.

Summary of the analysis of vnd/NK-2 regulatory DNA. Five DNA fragments from the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene were subcloned in the 5′-flanking region of an enhancerless β-gal gene in a P-element. The constructs were used to generate transgenic lines of Drosophila. The number of transgenic lines of flies generated for each construct is shown (enclosed by parentheses). DNA region A, −4.0 to −2.8 kb, is sufficient to direct Vnd/NK-2 expression in the following ten NBs: 1-1 (transient expression, not shown), 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, 7-1, and MP-2. In addition, region A activates ectopic Vnd/NK-2 expression in two cells, E1 and E3. DNA region B (B1 and B2, −5.3 to −4.0 kb) contains nucleotide sequences that activate the vnd/NK-2 gene in four NBs as follows: 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, and 4-1. DNA region B2 (−4.7 to −4.0 kb) activates the vnd/NK-2 gene ectopically in cell E2 and represses the vnd/NK-2 gene in E3. DNA region B1 (−5.3 to −4.7 kb) contains nucleotide sequences that repress the ectopic expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in E1 and E2. Hypothesized DNA region C, whose location has not been identified, activates the vnd/NK-2 gene in NB 7-2. ML rep (−3.6 to −3.1 kb) corresponds to the region of DNA in the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene that Estes et al. (18) have shown is required for midline repression of the vnd/NK-2 gene mediated indirectly by the Sim protein in mesoectodermal cells.

Estes et al. (18) have shown that the nucleotide sequence(s) required for repression of the vnd/NK-2 gene mediated indirectly by the Sim protein in mesectodermal cells is located between −3.6 and −3.1 kb in the 5′-flanking region of the vnd/NK-2 gene. In addition, they showed that three regions in the 5′-upstream region of the vnd/NK-2 gene, −5.3 to −4.2 kb, −4.2 to −3.1 kb, and −3.1 to −2.8 kb, are required for expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in the ventral neuroectoderm. Our results agree with and extend their findings with regard to regulation of the vnd/NK-2 gene. The results also suggest that other regions of DNA that have not been identified may be required for expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene in some cephalic cells and in the neuroectodermal precursors of the 11 neuroblasts per hemisegment that express the vnd/NK-2 gene. The regulatory mechanism(s) involved in activating the vnd/NK-2 gene in region B DNA was found only in medial or near medial NBs of transverse rows 1 through 4, but not in NBs of transverse rows 6 and 7, which raises the possibility that the expression of the corresponding enhancer(s) or repressor(s) proteins may be restricted to the anterior or the posterior part of each segment, respectively.

We conclude that nucleotide sequences in at least three regions of DNA regulate the expression of the vnd/NK-2 gene, that the pattern of vnd/NK-2 gene expression in NBs of the ventral nerve cord is formed from partial patterns, and that three subsets of NBs were identified that differ in the mechanism of activation of the vnd/NK-2 gene. DNA region A is involved in activation of the vnd/NK-2 gene in NBs 1-1, 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, MP-2, 4-1, 5-1, 5-2, 6-1, and 7-1; DNA region B is involved in activation of this gene in NBs 1-2, 2-1, 3-1, and 4-1; and hypothesized DNA region C is involved in activation the vnd/NK-2 gene in NB 7-2.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tom Brody for helpful suggestions concerning the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- NB

neuroblast

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- β-Gal

β-galactosidase

Footnotes

Zhao, G. & Skeath, J.B. (2001) 41st Annual Drosophila Meeting, Washington, D.C., abstr. 186.

Shao, X., Koizumi, K., Tan, D.-P., Odenwald, W. & Nirenberg, M. (1999) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 25, 526.

Shao, X., Koizumi, K. Tan, D.-P., Odenwald, W. & Nirenberg, M. (2001) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 27, 1227.

References

- 1.Kim Y, Nirenberg M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7716–7720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nirenberg M, Nakayama K, Nakayama N, Kim Y, Mellerick D, Wang L-H, Webber K O, Lad R. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1995;758:224–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb24830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiménez F, Martin-Morris L E, Velasco L, Chu H, Sierra J, Rosen D R, White K. EMBO J. 1995;14:3487–3495. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skeath J B, Panganiban G F, Carroll S B. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1994;120:1517–1524. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss J B, Von Ohlen T, Mellerick D M, Dressler G, Doe C Q, Scott M P. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3591–3602. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald J A, Holbrook S, Isshiki T, Weiss J, Doe C Q, Mellerick D M. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3603–3612. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Alessio M, Frasch M. Mech Dev. 1996;58:217–231. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isshiki T, Takeichi M, Nose A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:3099–3109. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.16.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chu-LaGraff Q, Doe C Q. Science. 1993;261:1594–1597. doi: 10.1126/science.8372355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skeath J B, Zhang Y, Holmgren R, Carroll S B, Doe C Q. Nature (London) 1995;376:427–430. doi: 10.1038/376427a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki M, Saigo K. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:3567–3575. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arendt D, Nübler-Jung K. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:2309–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cornell R A, Von Ohlen T. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(99)00049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McMahon A P. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2261–2264. doi: 10.1101/gad.840800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu H, Parras C, White K, Jiménez F. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3613–3624. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mellerick D M, Nirenberg M. Dev Biol. 1995;171:306–316. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saunders H-M H, Koizumi K, Odenwald W, Nirenberg M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8316–8321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes P, Mosher J, Crews S T. Dev Biol. 2001;232:157–175. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Ohlen T, Doe C Q. Dev Biol. 2000;224:362–372. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Udolph G, Lüer K, Bossing T, Technau G M. Science. 1995;269:1278–1281. doi: 10.1126/science.7652576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udolph G, Urban J, Rüsing G, Lüer K, Technau G M. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:3291–3300. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schweitzer R, Shaharabany M, Seger R, Shilo B-Z. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1518–1529. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Golembo M, Raz E, Shilo B-Z. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:3363–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schnepp B, Grumbing G, Donaldson T, Simcox A. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2302–2313. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.18.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seger R, Krebs E G. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raz E, Shilo B-Z. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1937–1948. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yagi Y, Suzuki T, Hayashi S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:3625–3633. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.18.3625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skeath J B. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:3301–3312. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.17.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhat K M, Schedl P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:1675–1688. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.9.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thummel C S, Pirrotta V. Drosophila Inf Serv. 1992;71:150. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doe C. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1992;116:855–863. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chu-LaGraff Q, Schmid A, Leidel J, Brönner G, Jäckle H, Doe C Q. Neuron. 1995;15:1041–1051. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]