Abstract

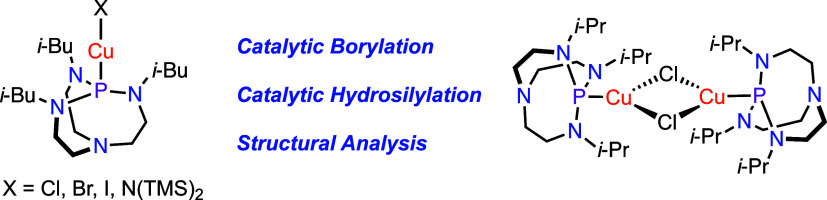

Copper(I) complexes of isobutyl- (i-BuL) and isopropyl-substituted (i-PrL) proazaphosphatranes have been synthesized. Structural and computational studies of a series of monomeric complexes i-BuLCuX (X = Cl, Br, I) and dimeric [i-PrLCuCl]2 provide insight into the transannulation within and steric properties of the proazaphosphatrane ligand. These halide complexes are competent precatalysts in a model borylation reaction, and the silylamido complex i-BuLCuN(TMS)2 catalyzes hydrosilylation of benzaldehyde under mild conditions.

Short abstract

Structural and computational studies of a series of monomeric complexes i-BuLCuX (X = Cl, Br, I) and dimeric [i-PrLCuCl]2 provide insight into the transannulation within and steric properties of the proazaphosphatrane ligand.

Introduction

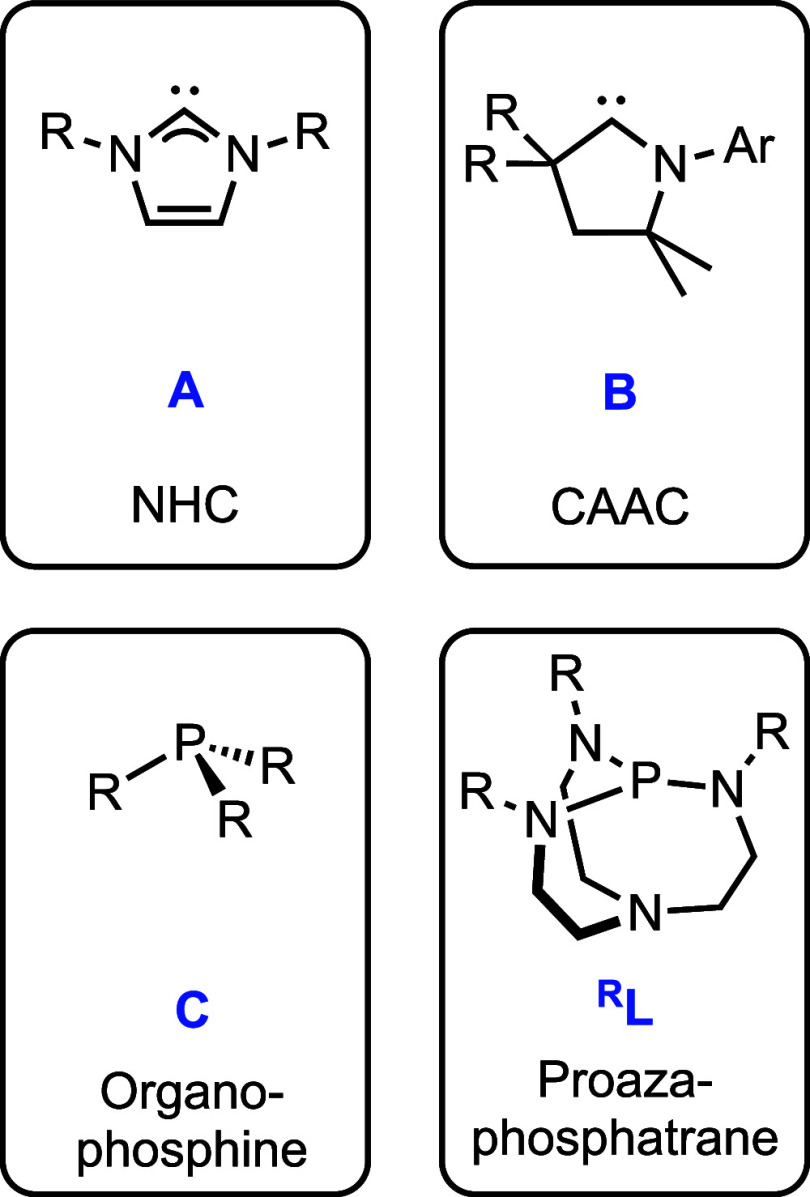

Low-coordinate copper(I) complexes, especially two-coordinate, 14-electron ones, are employed in numerous fields, including catalysis,1−3 small molecule activation,4−6 materials chemistry,7,8 and modeling of bioinorganic compounds.9,10 To harness the properties of these complexes, bulky, strongly binding ancillary ligands are often employed to mitigate aggregation of the complexes and tune metal properties (Figure 1). Carbene ligands, especially N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs, A)11 and cyclic alkyl(amino) carbenes (CAACs, B),12,13 are effective in improving the thermal stability of copper complexes,14 enforcing low nuclearity,15 and engendering broad reactivity16 and valuable physical properties.17,18 Sterically encumbered organophosphines (C) have also provided access to two-coordinate copper(I) complexes; however, these compounds are rarer, especially heteroleptic monometallic ones.19−23 Development and understanding of other classes of supporting ligands are necessary to advance the chemistry of low-coordinate copper.

Figure 1.

Ligand classes for preparing two-coordinate copper complexes.

Proazaphosphatranes (RL, Figure 1) represent a unique class of ligands for the stabilization of transition metals. Though initially only metalated with rhenium,24 mercury,24 and platinum25 in the early 1990s, interest in the coordination chemistry of proazaphosphatranes has grown in the past decade. These ligands rival trialkyl phosphines in donor ability and have tunable steric bulk at the three equatorial nitrogens, providing properties easily quantified by Tolman electronic parameters and cone angle, respectively.26 The conformational flexibility of these molecules allows them to accommodate changing coordination environments and oxidation states of metal through variable transannular interactions.27,28 The proazaphosphatrane motif can be incorporated into polydentate ligands29 and used to prepare bimetallic complexes30 as well. Studies of gold and rhodium proazaphosphatrane complexes have also shown that these aminophosphines may share the properties of both NHCs and organophosphines.31 Furthermore, the use of proazaphosphatranes in transition metal catalysis is limited to single accounts with platinum32 and silver33 and extensive use with palladium;34,35 no catalysis with earth-abundant metals has been reported, and the use of discrete metal-proazaphosphatrane precatalysts has been described only once.28 Herein, we report the synthesis of copper(I) proazaphosphatrane complexes and an analysis of their structures and reactivity.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structural Analysis

Copper(I) halide proazaphosphatrane complexes were prepared by the treatment of RL with copper(I) halides in THF (Scheme 1). Complexes i-BuLCuX (X = Cl, Br, I) are monomeric in the solid state (Figure 2), making this series one of only three reported in which a triad of monomeric copper(I) halide complexes is supported by the same phosphorus-based ligand.19,21,22 The Cu–P and Cu–X bond distances in these compounds are similar to those in the series where the ligand was tris(2,4,6-trimethoxyphenyl)phosphine (TMPP)21 and t-BuXPhos,19 but are markedly more linear (Table 1; see Table S1 for comparative data). This difference may be attributed to the absence of coordinating groups in i-BuL, whereas the oxygens in TMPP and the aryl ring in t-BuXPhos interact with the copper center of their complexes. The complexes in the i-BuLCuX series have near-identical 1H NMR spectra in C6D6 with a downfield translation of all resonances by less than 0.2 ppm going from the chloride to bromide to iodide. All complexes also exhibit a broad 31P resonance found between 104 to 108 ppm. The use of i-PrL with CuCl resulted in the formation of a dimeric structure with bridging chlorides in the solid state, a ubiquitous motif in copper(I) halide chemistry.36 Attempts to coordinate MeL and BnL to copper(I) halides resulted in complex mixtures and insoluble materials without the desired product in both cases. All isolated complexes are air-sensitive but can be stored indefinitely in a glovebox at −35 °C.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Proazaphosphatrane Copper(I) Halide Complexes.

Figure 2.

Solid state structures of proazaphosphatrane copper(I) halide complexes. All hydrogen atoms were omitted for clarity.

Table 1. Crystallographic and Computed Metrics for i-BuLCuX.

| X | P–Cu–X (deg) (expt.) | Cu–X (Å) (expt.) | Cu–P (Å) (expt.) | P···Nap (Å) (expt.) | P···Nap (Å) (theory)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | 3.270 | ||||

| Cl | 180.00(2) | 2.1153(5) | 2.1668(5) | 3.172(1) | 3.262 |

| Br | 180.00(2) | 2.2412(5) | 2.1703(5) | 3.181(1) | 3.258 |

| I | 175.44(2) | 2.4223(4) | 2.1897(6) | 3.219(2) | 3.255 |

All values are for the gas phase.

A key feature of proazaphosphatranes is their ability to undergo transannulation, a phenomenon in which intramolecular interaction between phosphorus and the apical nitrogen (Nap) of the molecule increases and, consequently, transannular distance decreases.37 Transannulation increases with decreased electron density at phosphorus, typically because of ligation to a Lewis acid.24 It is this phenomenon that causes the exceptional basicity of these molecules.38,39 We hypothesized that transannulation in the proazaphosphatrane ligand of i-BuLCuX might increase with the electronegativity of the halide, as has been seen with haloazaphosphatranes.40,41 In the solid state, the transannular interaction increases modestly with increasing electronegativity of the halide substituent for these complexes, resulting in a contraction of the transannular distance from 3.219(2) Å with iodide to 3.172(1) Å with chloride (Table 1). These values suggest that i-BuL forms a quasi-azaphosphatrane (transannular distance between 1.97 and 3.35 Å)42 when bound to copper(I), regardless of the accompanying halide ligand. To address the issue of crystal packing forces and to examine the theoretical i-BuLCuF, we also modeled these complexes computationally in the gas phase. The transannular distances for the four computed compounds were within 0.02 Å of one another and were higher than but within 0.1 Å of experimental results (Table 1). Natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis indicated that there is no meaningful bonding interaction between phosphorus and the apical nitrogen for any of the complexes. It can be concluded from these experimental and theoretical data that the halide does not perturb transannulation significantly; in previous studies, the oxidation state of metal was found to have the most significant impact on the phosphorus–apical nitrogen interaction.27,28

We next examined the steric bulk of i-BuL and i-PrL. The cone angles of i-BuL and i-PrL had previously been measured as 200° and 179°, respectively;26 however, the steric projection of the equatorial alkyl groups of RL around the metal center suggests that buried volume (%Vbur)43 may facilitate comparison with both phosphines and NHCs.44 Additionally, cone angle45 does not necessarily correlate with the nuclearity of 1:1 copper(I) halide phosphine complexes. For example, in the case of copper(I) chlorides, P(o-tolyl)3 (194°)46 and PCy3 (179°)47 support the formation of dimers in the solid state, whereas Pt-Bu3 (182°) yields a tetramer.15 The %Vbur of RL in the solid state structures of their copper(I) chlorides were 38.5% (R = i-Pr) and 46.1% (R = i-Bu), highlighting the greater steric protection afforded around copper in the latter case (Table 2). The %Vbur values of the ligands in the gas phase structures of RLCuCl were similar to the solid state values. For comparison, i-BuL has a %Vbur comparable to that of PMes3 (47.6%) and greater than that of the ubiquitous NHC 1,3-bis(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)imidazole-2-ylidene (39.0%).44 Because proazaphosphatranes are conformationally flexible molecules, we also examined the range of buried volumes that can be achieved with these ligands; knowledge of these ranges is valuable in understanding reactivity patterns in catalysis.48 High-energy conformers were found for both i-PrLCuCl and i-BuLCuCl. The higher energy conformer of i-PrLCuCl has a higher %Vbur than its minimum energy conformer (49.2% vs 38.9%), whereas the opposite relationship is seen for i-BuLCuCl (38.5% vs 46.1%, Table 2). Simultaneously, the transannular distance in computed i-PrLCuCl increases with the higher energy conformer, while the same metric decreases for i-BuLCuCl. These changes highlight the structural complexity of proazaphosphatranes and the multiple features that contribute to the conformational flexibility of these compounds.

Table 2. Buried Volume Determination for Copper(I) Chloride Proazaphosphatrane Complexesa.

| %Vbur (expt.) | %Vbur, min. energy structure (theory) | P···Nap (Å), min. energy structure (theory) | %Vbur, high-energy structure (theory) | P···Nap (Å), high-energy structure (theory) | ΔEc (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i-PrL | 38.5 | 38.9b | 3.204 | 49.2b | 3.298 | 3.7 |

| i-BuL | 46.1 | 46.1 | 3.262 | 38.5 | 3.150 | 5.1 |

See Supporting Information for full calculation details.

Based on monomer.

Difference in energy between lowest energy structure and high-energy structure.

Reactivity

Copper(I) halide complexes are effective precatalysts for the borylation of aryl iodides at ambient temperature when supported by NHCs49 or phosphines.50 The importance of balancing steric protection around and accessibility at the metal center was previously noted in designing a ligand for this transformation,49 and conformationally flexible ligands have been shown to strike this balance in other cross-coupling reactions.51 Inspired by these precedents and observations, we evaluated the borylation of iodobenzene using bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2) catalyzed by our proazaphosphatrane complexes (Table 3). The reaction between these coupling partners in the presence of simple cuprous halides resulted in under one turnover, and no reaction was observed in the absence of CuX or only in the presence of i-BuL. For the proazaphosphatrane complexes, catalysis was achieved, albeit with a relatively low turnover. i-BuLCuI provided a 41% yield (4.1 TON), which was markedly higher than its bromide (22% yield, 2.2 TON) and chloride (16% yield, 1.6 TON) analogues, and [i-PrLCuCl]2 (16% yield, 1.6 TON). In the literature, higher catalyst performance was achieved with aryl halides (bromides and iodides) and B2pin2 under similar reaction conditions using n-Bu3P and CuI (e.g., 10 mol % catalyst with 4-iodotoluene, 92% yield)50 and a bicyclic NHC copper(I) chloride system (e.g., 5 mol % catalyst with bromobenzene 71% yield).49 We also attempted to prepare the complex i-BuLCuOt-Bu as a precatalyst because copper(I) tert-butoxide complexes undergo transmetalation to form copper(I) boryl species that have been invoked in borylation.52 Treatment of the halide complexes with KOt-Bu resulted in the displacement of i-BuL as well as the formation of a new phosphorus-containing species that may be i-BuLCuOt-Bu, a mixture that was unsuitable for catalytic studies. The addition of i-BuL to copper(I) tert-butoxide also resulted in the same species as well as unbound i-BuL (see Supporting Information). Taken together, these results suggest that copper(I) proazaphosphatranes are competent precatalysts for borylation but may undergo complex speciation under catalytic conditions; indeed, copper(I) phosphine complexes with boryl ligands are unstable53 and ones with tert-butoxide ligands have only been structurally characterized as dimers.53,54

Table 3. Examination of Copper-Catalyzed Borylation of Iodobenzenea.

| Cl | Br | I | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CuX | 5% | 7% | <5% |

| i-BuLCuX | 16% | 22% | 41% |

| i-PrLCuX | 16% |

Reported yields were determined by GC/MS analysis vs dodecane as an internal standard. Yields are an average of duplicate runs.

Copper(I) NHC15,55 and phosphine15,36 complexes are effective catalysts for the hydrosilylation of a range of carbonyl compounds, which motivated us to examine our own complexes in this class of transformation. Reactions often involve the generation of a copper tert-butoxide precatalyst that is then converted into a reactive copper hydride intermediate;15,55 however, based on our borylation results, we recognized that such a species might not be effective given the lability of i-BuL. This detail is particularly important because proazaphosphatranes catalyze the hydrosilylation of aldehydes, presumably through coordination with the silicon of the silylating agent, to form a reactive five-coordinate intermediate.56 The recent synthesis and use of silver hexamethyldisilazide complexes in hydrofunctionalization57,58 inspired us to synthesize i-BuLCuN(TMS)2 (Figure 3). Treatment of i-BuLCuCl with LiHMDS led to the formation of the desired product. A crystal structure of this highly soluble and air-sensitive complex was not obtained, but the compound was characterized by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of LCuN(TMS)2.

The reaction of benzaldehyde and diphenylsilane was chosen as a model reaction for hydrosilylation because of their use both in copper36 and silver57,58 systems (Table 4). These compounds do not react without a catalyst; however, in the presence of i-BuL, full conversion to a 58:42 mixture of (benzyloxy)diphenylsilane (D):diphenyldibenzyloxysilane (E) was achieved within an hour. When subjected to the same conditions but in the presence of i-BuLCuN(TMS)2, the hydrofunctionalization proceeds at a lower rate and with increased selectivity for D, indicating that dissociated i-BuL alone is not catalyzing the transformation. Treatment of i-BuLCuN(TMS)2 with benzaldehyde or Ph2SiH2 does not result in the formation of any new species by NMR. These results suggest that i-BuLCuN(TMS)2 is a precatalyst for hydrosilylation, and the active catalyst favors the reaction of a single carbonyl with a secondary silane, and if a hydride intermediate is generated, it forms transiently.

Table 4. Catalytic Hydrosilylation of Benzaldehyde.

Conversion is based on the consumption of aldehyde as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Conclusions

We have expanded the coordination chemistry of proazaphosphatranes to include copper. Ligand i-BuL grants access to a rare series of two-coordinate copper(I) complexes that vary only by a halide substituent, allowing the systematic examination of transannulation as a function of the second ligand. In addition to these molecules being precatalysts for a model borylation reaction, i-BuLCuCl can be converted to i-BuLCuN(TMS)2, which is a precatalyst for hydrosilylation. These findings suggest that proazaphosphatranes can be employed outside the second and third rows of the transition metals to prepare low-coordinate base metal catalysts for a variety of applications.

Experimental Section

All experimental details are described in the Supporting Information.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. CHE-2044834 (M.W.J.). The Thomas F. and Kate Miller Jeffress Memorial Trust and University of Richmond are acknowledged for initial funding of this research. M.W.J. is grateful to the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation for the Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award. K.J.D. acknowledges the support from the National Science Foundation (NSF-RUI Award (CHE-2055119) and NSF-MRI Grants (CHE-0958696, University of Richmond, and CHE-1662030, the MERCURY consortium)). Daniel Duplessis synthesized BnL for this study. The authors thank Dr. Diane Kellogg for her invaluable assistance with GC/MS analysis. Finally, we are indebted to Philip Joseph, who made this work and all other studies in our research group possible during his career as stockroom manager of the Department of Chemistry at the University of Richmond.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.4c04779.

Author Contributions

§ W.E.A. and V.A.O. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Liu R. Y.; Buchwald S. L. CuH-Catalyzed Olefin Functionalization: From Hydroamination to Carbonyl Addition. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 1229–1243. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch C.; Krause N.; Lipshutz B. H. CuH-Catalyzed Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 2916–2927. 10.1021/cr0684321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbert J. D.; Cazin C. S. J.; Nolan S. P. Copper N-Heterocyclic Carbene Complexes in Catalysis. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 912–926. 10.1039/c2cy20816d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M. E.; Boroujeni M. R.; Ghosh P.; Greene C.; Kundu S.; Bertke J. A.; Warren T. H. Electrocatalytic Ammonia Oxidation by a Low-Coordinate Copper Complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 21136–21145. 10.1021/jacs.2c07977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Hou Z. N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC)–Copper-Catalysed Transformations of Carbon Dioxide. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3395–3403. 10.1039/c3sc51070k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huerfano I. J.; Laskowski C. A.; Pink M.; Carta V.; Hillhouse G. L.; Caulton K. G.; Smith J. M. Redox-Neutral Transformations of Carbon Dioxide Using Coordinatively Unsaturated Late Metal Silyl Amide Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 20986–20993. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Housecroft C. E.; Constable E. C. TADF: Enabling Luminescent Copper(I) Coordination Compounds for Light-Emitting Electrochemical Cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 4456–4482. 10.1039/D1TC04028F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaab J.; Djurovich P. I.; Thompson M. E.. Two-Coordinate, Monovalent Copper Complexes as Chromophores and Luminophores. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; van Eldik R.; Ford P. C., Eds.; Academic Press, 2024; Vol. 83, Chapter 6, pp 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Mankad N. P.; Antholine W. E.; Szilagyi R. K.; Peters J. C. Three-Coordinate Copper(I) Amido and Aminyl Radical Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3878–3880. 10.1021/ja809834k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groysman S.; Holm R. H. A Series of Mononuclear Quasi-Two-Coordinate Copper(I) Complexes Employing a Sterically Demanding Thiolate Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 621–627. 10.1021/ic801836k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazreg F.; Cazin C. S. J.. NHC–Copper Complexes and Their Applications. In N-Heterocyclic Carbenes; Nolan S. P., Ed.; Wiley-VCH, 2014; pp 199–242. [Google Scholar]

- Roy S.; Mondal K. C.; Roesky H. W. Cyclic Alkyl(Amino) Carbene Stabilized Complexes with Low Coordinate Metals of Enduring Nature. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 357–369. 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazzar R.; Soleilhavoup M.; Bertrand G. Cyclic (Alkyl)- and (Aryl)-(Amino)Carbene Coinage Metal Complexes and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 4141–4168. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafabadi B. K.; Corrigan J. F. Enhanced Thermal Stability of Cu–Silylphosphido Complexes via NHC Ligation. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 14235–14241. 10.1039/C5DT02040A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díez-González S.; Kaur H.; Zinn F. K.; Stevens E. D.; Nolan S. P. A Simple and Efficient Copper-Catalyzed Procedure for the Hydrosilylation of Hindered and Functionalized Ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 4784–4796. 10.1021/jo050397v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beig N.; Goyal V.; Bansal R. K. Application of N-Heterocyclic Carbene–Cu(I) Complexes as Catalysts in Organic Synthesis: A Review. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2023, 19, 1408–1442. 10.3762/bjoc.19.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M.; Mukthar N. F. M.; Schley N. D.; Ung G. Yellow Circularly Polarized Luminescence from C1-Symmetrical Copper(I) Complexes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1228–1231. 10.1002/anie.201913672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle J. P.; Sirianni E. R.; Korobkov I.; Yap G. P. A.; Dey G.; Barry S. T. Study of Monomeric Copper Complexes Supported by N-Heterocyclic and Acyclic Diamino Carbenes. Organometallics 2017, 36, 2800–2810. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse S. S.; Buchanan J. K.; Dais T. N.; Ainscough E. W.; Brodie A. M.; Freeman G. H.; Plieger P. G. Structural Trends in a Series of Bulky Dialkylbiaryl-phosphane Complexes of CuI. Acta Crystallogr. 2021, C77, 513–521. 10.1107/S2053229621008159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herberhold M.; Akkus N.; Milius W. 1:1 Adducts of Copper(I) and Silver(I) Halides with the Olefinic Phosphane Tri(1-Cyclohepta-2, 4, 6-Trienyl)Phosphane. Molecular Structures of CuX[P(C7H7)3] (X = Cl, Br), AgCl[P(C7H7)3] and {Cu(μ3-I)[P(C7H7)3]}4. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2003, 629, 2458–2464. 10.1002/zaac.200300274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker L.-J.; Bowmaker G. A.; Hart R. D.; Harvey P. J.; Healy P. C.; White A. H. Structural, Far-IR, and Solid State 31P NMR Studies of Two-Coordinate Complexes of Tris(2,4,6-Trimethoxyphenyl)Phosphine with Copper(I) Iodide. Inorg. Chem. 1994, 33, 3925–3931. 10.1021/ic00096a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowmaker G. A.; Cotton J. D.; Healy P. C.; Kildea J. D.; Silong S. B.; Skelton B. W.; White A. H. Solid-State Phosphorus-31 NMR, Far-IR, and Structural Studies on Two-Coordinate (Tris(2,4,6-Trimethoxyphenyl)Phosphine)Copper(I) Chloride and Bromide. Inorg. Chem. 1989, 28, 1462–1466. 10.1021/ic00307a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alyea E. C.; Ferguson G.; Malito J.; Ruhl B. Monomeric (Trimesitylphosphine)-Copper(I) Bromide. X-Ray Crystallographic Evidence for the First Two-Coordinate Copper(I) Phosphine Halide Complex. Inorg. Chem. 1985, 24, 3719–3720. 10.1021/ic00217a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J. S.; Laramay M. A. H.; Young V.; Ringrose S.; Jacobson R. A.; Verkade J. G. Stepwise Transannular Bond Formation between the Bridgehead Atoms in Z-P(MeNCH2CH2)3N Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 3129–3131. 10.1021/ja00034a065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xi S. K.; Schmidt H.; Lensink C.; Kim S.; Wintergrass D.; Daniels L. M.; Jacobson R. A.; Verkade J. G. Bridgehead-Bridgehead Communication in Untransannulated Phosphatrane ZP(ECH2CH2)3N Systems. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 2214–2220. 10.1021/ic00337a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thammavongsy Z.; Kha I. M.; Ziller J. W.; Yang J. Y. Electronic and Steric Tolman Parameters for Proazaphosphatranes, the Superbase Core of the Tri(Pyridylmethyl)Azaphosphatrane (TPAP) Ligand. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 9853–9859. 10.1039/C6DT00326E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thammavongsy Z.; Cunningham D. W.; Sutthirat N.; Eisenhart R. J.; Ziller J. W.; Yang J. Y. Adaptable Ligand Donor Strength: Tracking Transannular Bond Interactions in Tris(2-Pyridylmethyl)-Azaphosphatrane (TPAP). Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 14101–14110. 10.1039/C8DT03180K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A. D.; Gravalis G. M.; Schley N. D.; Johnson M. W. Synthesis, Structure, and Reactivity of Palladium Proazaphosphatrane Complexes Invoked in C–N Cross-Coupling. Organometallics 2018, 37, 3073–3078. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thammavongsy Z.; Khosrowabadi Kotyk J. F.; Tsay C.; Yang J. Y. Flexibility Is Key: Synthesis of a Tripyridylamine (TPA) Congener with a Phosphorus Apical Donor and Coordination to Cobalt(II). Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 11505–11510. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b02133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutthirat N.; Ziller J. W.; Yang J. Y.; Thammavongsy Z. Crystal Structure of NiFe(CO)5[Tris(Pyridylmethyl)Azaphosphatrane]: A Synthetic Mimic of the NiFe Hydrogenase Active Site Incorporating a Pendant Pyridine Base. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. E 2019, 75, 438–442. 10.1107/S2056989019003256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatelet B.; Nava P.; Clavier H.; Martinez A. Synthesis of Gold(I) Complexes Bearing Verkade’s Superbases. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 2017, 4311–4316. 10.1002/ejic.201700897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aneetha H.; Wu W.; Verkade J. G. Stereo- and Regioselective Pt(DVDS)/P(iBuNCH2CH2)3N-Catalyzed Hydrosilylation of Terminal Alkynes. Organometallics 2005, 24, 2590–2596. 10.1021/om050034l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai T.; Hu H.; Wang Z.; Martinez A.; Dufaud V.; Gao G. Azaphosphatrane/Ag2O Catalyzed the Carboxylative Cyclization of Propargylic Alcohols and CO2. Mol. Catal. 2024, 555, 113892 10.1016/j.mcat.2024.113892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You J.; Verkade J. G. A General Method for the Direct α-Arylation of Nitriles with Aryl Chlorides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5051–5053. 10.1002/anie.200351954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkat Reddy C. R.; Urgaonkar S.; Verkade J. G. A Highly Effective Catalyst System for the Pd-Catalyzed Amination of Vinyl Bromides and Chlorides. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4427–4430. 10.1021/ol051612x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihara T.; Semba K.; Terao J.; Tsuji Y. Copper-Catalyzed Hydrosilylation with a Bowl-Shaped Phosphane Ligand: Preferential Reduction of a Bulky Ketone in the Presence of an Aldehyde. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 1472–1476. 10.1002/anie.200906348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkade J. G. Atranes: New Examples with Unexpected Properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993, 26, 483–489. 10.1021/ar00033a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanga P. B.; Verkade J. G.; Schwesinger R. pKa Measurements of P(RNCH2CH3)3N. J. Org. Chem. 2000, 65, 5431–5432. 10.1021/jo000427o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah S. S.; Rohman S. S.; Kashyap C.; Guha A. K. Protonation of Verkade Bases: A Theoretical Study. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 2575–2582. 10.1039/C8NJ04977G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone T. C.; Briceno-Strocchia A. I.; Stephan D. W. Frustrated Lewis Pair Oxidation Permits Synthesis of a Fluoroazaphosphatrane, [FP(MeNCH2CH2)3N]+. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 15299–15304. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b02605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews A. D.; Prasad S.; Schley N. D.; Donald K. J.; Johnson M. W. On Transannulation in Azaphosphatranes: Synthesis and Theoretical Analysis. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 15983–15992. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b02467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.-D.; Verkade J. G. Unusual Phosphoryl Donor Properties of O = P(MeNCH2CH2)3N. Inorg. Chem. 1998, 37, 5189–5197. 10.1021/ic9714652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falivene L.; Cao Z.; Petta A.; Serra L.; Poater A.; Oliva R.; Scarano V.; Cavallo L. Towards the Online Computer-Aided Design of Catalytic Pockets. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 872–879. 10.1038/s41557-019-0319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavier H.; Nolan S. P. Percent Buried Volume for Phosphine and N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands: Steric Properties in Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 841–861. 10.1039/b922984a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman C. A. Phosphorus Ligand Exchange Equilibriums on Zerovalent Nickel. Dominant Role for Steric Effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 2956–2965. 10.1021/ja00713a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akrivos P. D.; Hadjikakou S. K.; Karagiannidis P.; Mentzafos D.; Terzis A. Study of the Geometric Preferences of Copper(I) Halide Coordination Compounds with Triarylphosphines. Crystal Structure of [Cu2I2{P(m-tolyl)3}3]. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1993, 206, 163–168. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)82862-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Churchill M. R.; Rotella F. J. Molecules with an M4X4 Core. 10. Failure of the 1:1:1 Tricyclohexylphosphine-Copper(I)-Chloride Complex to Form a Tetramer. Crystal Structure of Dimeric (Tricyclohexylphosphine)Copper(I) Chloride, [(P(cHx)3)CuCl]2. Inorg. Chem. 1979, 18, 166–171. 10.1021/ic50191a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman-Stonebraker S. H.; Smith S. R.; Borowski J. E.; Peters E.; Gensch T.; Johnson H. C.; Sigman M. S.; Doyle A. G. Univariate Classification of Phosphine Ligation State and Reactivity in Cross-Coupling Catalysis. Science 2021, 374, 301–308. 10.1126/science.abj4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando S.; Matsunaga H.; Ishizuka T. A Bicyclic N-Heterocyclic Carbene as a Bulky but Accessible Ligand: Application to the Copper-Catalyzed Borylations of Aryl Halides. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 9671–9681. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleeberg C.; Dang L.; Lin Z.; Marder T. B. A Facile Route to Aryl Boronates: Room-Temperature, Copper-Catalyzed Borylation of Aryl Halides with Alkoxy Diboron Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5350–5354. 10.1002/anie.200901879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altenhoff G.; Goddard R.; Lehmann C. W.; Glorius F. Sterically Demanding, Bioxazoline-Derived N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands with Restricted Flexibility for Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15195–15201. 10.1021/ja045349r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitar D. S.; Müller P.; Sadighi J. P. Efficient Homogeneous Catalysis in the Reduction of CO2 to CO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17196–17197. 10.1021/ja0566679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borner C.; Anders L.; Brandhorst K.; Kleeberg C. Elusive Phosphine Copper(I) Boryl Complexes: Synthesis, Structures, and Reactivity. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4687–4690. 10.1021/acs.organomet.7b00775. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmen T. H.; Goeden G. V.; Huffman J. C.; Geerts R. L.; Caulton K. G. Alcohol Elimination Chemistry of (CuOtBu)4. Inorg. Chem. 1990, 29, 3680–3685. 10.1021/ic00344a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur H.; Zinn F. K.; Stevens E. D.; Nolan S. P. (NHC)CuI (NHC = N-Heterocyclic Carbene) Complexes as Efficient Catalysts for the Reduction of Carbonyl Compounds. Organometallics 2004, 23, 1157–1160. 10.1021/om034285a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Wroblewski A. E.; Verkade J. G. P(MeNCH2CH2)3N: An Efficient Promoter for the Reduction of Aldehydes and Ketones with Poly(Methylhydrosiloxane). J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 8021–8023. 10.1021/jo990624r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso C. P.; Zeil D. V.; Blair V. L. Catalytic Exploration of NHC–Ag(I)HMDS Complexes for the Hydroboration and Hydrosilylation of Carbonyl Compounds. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 7828–7835. 10.1039/D3DT01042B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr S. A.; Kelly J. A.; Boutland A. J.; Blair V. L. Structural Elucidation of Silver(I) Amides and Their Application as Catalysts in the Hydrosilylation and Hydroboration of Carbonyls. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 4947–4951. 10.1002/chem.202000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.