Abstract

Background

Sarcopenia, a prevalent muscle disorder in the older adults, is characterized by accelerated loss of muscle mass and function, contributing to increased risks of falls, functional decline, and mortality. The relationship between dietary oxidative balance score (DOBS) and sarcopenia, however, remains unclear.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) 2011–2018 cohort, which included 8,240 participants, aged 47.2 ± 17.6 years (48.6% male, 51.4% female). The participants were selected from geographic locations across all 50 states and the District of Columbia, using a stratified, multistage probability sampling design to collect health and nutritional data representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population. We employed the generalized additive model to identify potential non-linear relationships and utilized the two-piecewise linear regression model to investigate the association between DOBS and sarcopenia in American adults.

Results

Participants were categorized into quartiles based on their DOBS, and sarcopenia was diagnosed in 702 individuals (8.5%). In the unadjusted model, DOBS exhibited a significant negative correlation with sarcopenia (β = 0.97, 95% Confidence Interval (CI): 0.96 to 0.99, P < 0.001). This association remained consistent in the model with minimal adjustment for age and gender (β = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96 to 0.98, P < 0.001) and in the fully adjusted model including additional covariates (β = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96 to 0.99, P < 0.001). After adjusting for potential confounders, we identified a non-linear association DOBS and sarcopenia, with an inflection point at 23. The effect sizes and CIs to the left and right of the inflection point were 1.62 (95% CI: 1.09 to 2.41, P = 0.016) and 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95 to 0.98, P < 0.001), respectively. Subgroup analyses confirmed the stability of this relationship across various demographic and health-related variables.

Conclusions

This research provides new insights into the association between diet quality, as assessed by DOBS, and sarcopenia, reinforcing the critical role of a balanced, antioxidant-rich diet in adult muscle.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12986-025-00894-4.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, Adolescents, Cross-sectional studies, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)

Introduction

Sarcopenia, i.e. muscle failure, is a muscle disease rooted in adverse muscle changes that accrue across a lifetime characterized primarily by low muscle strength. Sarcopenia has traditionally been linked to ageing and older people but is now understood to begin earlier in life and to have multiple contributing factors beyond age, highlighting the importance of early intervention strategies [1, 2]. It also affects younger adults under certain conditions. From ages 20 to 80, individuals typically lose about 30% of muscle mass and 20% in cross-sectional area (CSA) [3]. Women experience a muscle mass loss rate of 0.64–0.70% annually after 75 years, while men lose 0.80–0.98% per year [4]. Sarcopenia is partly attributed to increased oxidative metabolism, elevating reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [5]. Excessive ROS can damage DNA, proteins, and lipids, disrupting redox balance and cellular signaling, particularly in aging skeletal muscles [6, 7].

Dietary modification, a simple yet effective intervention, is key not just in managing health issues but also in prevention of diseases related to oxidative stress [8, 9]. A balanced diet enhances antioxidant levels, optimizes fatty acid ratios, increases dietary fiber, and encourages consumption of fruits, vegetables, and high-quality proteins, mitigating oxidative stress effects. Conversely, unhealthy diets, high in oil, salt, sugary beverages, excess alcohol, red meat, and involving high-temperature cooking, exacerbate oxidative stress. The dietary oxidative balance score (DOBS) is a comprehensive indicator that reflects the overall balance between various pro-oxidants and antioxidants in the diet [10, 11]. Higher DOBS indicates a better antioxidant profile and has been used to assess chronic disease risks like type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer [12, 13].

However, the association between DOBS and sarcopenia has not been adequately investigated, with few relevant reports currently available. Mahmoodi et al. [14] employ a case-control design with 160 participants, initial findings suggesting a protective effect of higher OBS against sarcopenia, adjusting for potential confounders like age, gender, and dietary factors revealed no statistically significant associations. Küçükdiler et al. [15] support that oxidative stress and imbalance between oxidative and antioxidant systems may be an important factor in both type 2 diabetes and sarcopenia. These findings should be considered with caution due to the limited number of included studies. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to investigate the association between DOBS and sarcopenia. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between DOBS and sarcopenia in adults, meticulously controlling for a wide range of confounding factors and conducting comprehensive subgroup analyses to ensure the stability of the findings. Our findings could have significant implications for the management of diet in patients with sarcopenia.

Methods

Study population

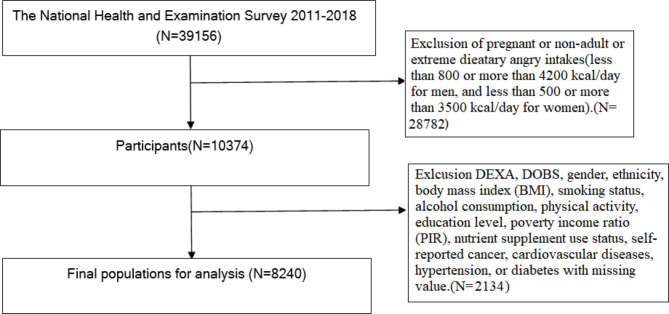

The NHANES employs a stratified, multistage probability sampling design to collect health and nutritional data representative of the civilian, non-institutionalized U.S. population [16, 17]. Specifically, the survey aims geographic locations across all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Participants are selected from these locations using a complex sampling framework that involves multiple stages. Initially, individual counties or small groups of contiguous counties are selected. Finally, households within these block clusters are randomly selected, and residents are invited to participate. This multistage process ensures that the survey sample is representative of the broader U.S. population across age, sex, and ethnicity dimensions. This study utilized NHANES data from 2011 to 2018, involving non-pregnant adults aged 18 years and older who participated in the survey. This cross-sectional analysis evaluates the prevalence of sarcopenia, defined as the total number of cases diagnosed among participants during the 2011–2018 NHANES survey cycles. We do not report incidence, as this study does not track new cases of sarcopenia over time. In this study, we examined data from 39,156 participants from the NHANES 2011–2018 cohort. From this population, we excluded 30,916 participants due to missing values in essential variables such as DEXA scans, DOBS, extreme dietary energy intakes [18], gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, poverty income ratio (PIR), nutrient supplement use status, and self-reported comorbidities including cancer, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes status. Following these exclusions, a total of 8240 individuals were included in the analysis of this cross-sectional study. Ethical approval was obtained from the NCHS Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided informed consent. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; DOBS, dietary oxidative balance score; BMI,body mass index; DEXA:dual energy X-ray absorptiometry

Definition of sarcopenia

Participants, aged between 18 and 59 years, underwent dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) whole-body evaluations using the Hologic Discovery Model A densitometers (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). Exclusions for DEXA scans included pregnancy, weight over 300 pounds due to scanner capacity, height over 6’5” because of the table limitations, recent exposure to barium-based radiographic contrast, or recent nuclear medicine studies. All scans were orchestrated using the Hologic software (V.8.26: a3), with DEXA being instrumental in gauging the appendicular skeletal muscle mass. The sarcopenia index was calculated as the ratio of total appendicular skeletal muscle mass (in kg) to Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2). Sarcopenia was defined based on the lowest sex-specific sarcopenia index cut-off values (0.789 for men, 0.512 for women), as determined by the foundation for the National Institutes of Health(FNIH) [19].

Assessment of DOBS

Dietary data for this study were sourced from two 24-hour recall interviews as part of NHANES. The initial interview occurred in person at a Mobile Examination Center (MEC), followed by a telephone interview within 3 to 10 days. The dietary data was derived from the average of these two recall sessions. To ensure robust dietary data we included participants who completed both dietary recalls. Out of the total participants who completed the initial dietary recall, a total of 73% participants also had data available from the second 24-hour recall. This dual-recall method helps mitigate recall bias and enhances the accuracy of dietary intake reporting, contributing to a more reliable Dietary DOBS calculation. DOBS was calculated by summing the scores of specific pro-oxidant and antioxidant factors [20]. The study considered three pro-oxidants and fourteen antioxidants, extensively researched for DOBS calculation. Dietary intake was segmented into tertiles for scoring: antioxidants were scored from 1 to 3 (first to third tertiles), and pro-oxidants inversely. Alcohol intake was categorized according to previously established criteria [21], with participants classified into non-drinkers, moderate drinkers, and heavy drinkers. The DOBS was calculated from the nutrient scores, with higher scores indicating a stronger dietary antioxidant profile. Detailed DOBS component setup is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Parameters of dietary composition used for DOBS construction

| Dietary composition | Property | DOBS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Dietary fiber (g/d) | Aa | ≤ 12.40 | 12.41–18.60 | > 18.61 |

| Ln-transformed carotene (µg/d) | A | ≤ 8.31 | 8.32–9.18 | > 9.19 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg/d) | A | ≤ 1.56 | 1.57–2.37 | > 2.38 |

| Niacin (mg/d) | A | ≤ 18.13 | 18.14–26.54 | > 26.55 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg/d) | A | ≤ 1.45 | 1.46–2.29 | > 2.30 |

| Folic acid (µg/d) | A | ≤ 288.50 | 288.51–431.00 | > 431.01 |

| Ln-transformed vitamin B12 (µg/d) | A | ≤ 1.43 | 1.44–1.92 | > 1.93 |

| Ln-transformed vitamin C (mg/d) | A | ≤ 3.83 | 3.84–4.63 | > 4.64 |

| Vitamin E (mg/d) | A | ≤ 5.81 | 5.82–9.25 | > 9.26 |

| Calcium (mg/d) | A | ≤ 663.00 | 663.01–1009.50 | > 1009.51 |

| Magnesium (mg/d) | A | ≤ 224.00 | 224.01–314.00 | > 314.01 |

| Zinc (mg/d) | A | ≤ 8.89 | 8.90–12.79 | > 12.80 |

| Copper (mg/d) | A | ≤ 0.97 | 0.98–1.43 | > 1.44 |

| Selenium (µg/d) | A | ≤ 82.15 | 82.16–119.25 | > 119.26 |

| Total fat (g/d) | Pb | > 83.13 | 55.29–83.12 | ≤ 55.29 |

| Iron (mg/d) | P | > 16.31 | 11.25–16.30 | ≤ 11.24 |

| Alcohol (male) (g/d) | P | > 30.01 | 0.01–30.00 | 0.00 |

| Alcohol (female) (g/d) | P | > 15.01 | 0.01–15.00 | 0.00 |

aAntioxidant. bPro-oxidant. DOBS: dietary oxidative balance score

Assessment of covariates

Based on existing literature and clinical experience, the selected covariates for this study were identified as follows: Demographic data: age (continuous variable), age group (<39, ≥ 39), race, educational level, and PIR (< 1,1–3, ≥ 3). Examination data: BMI (continuous variable). Questionnaire data: alcohol consumption (Non-drinker, 1 to < 5 drinks/month,5 to < 10 drinks/month,10 + drinks/month), smoking status (current, former, never smoker), physical activity (vigorous, moderate, light). Comprehensive data: hypertension status (yes or no), diabetes status (yes, no, or borderline), self-reported cancer (yes or no), nutrient supplement use status (yes or no), and cardiovascular diseases (yes or no). Categorization of these variables followed NHANES protocols.

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analyses to assess the stability of the association between DOBS and sarcopenia across different subpopulations. The subgroups were define age (< 39 years, ≥ 39 ), gender (male, female), diabetes (yes, no), cardiovascular diseases (yes, no), self-reported cancer (yes, no), hypertension (yes, no), and nutrient supplement use status (yes, no). Interaction terms between DOBS and each subgroup variable were introduced by the fully adjusted model to test potential effect modification. A p-value for interaction < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R statistical software and Empower Stats. Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For non-parametrically distributed variables, results were represented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), and group comparisons were made using non-parametric tests, such as the Mann-Whitney U test for two groups or the Kruskal-Wallis test for multiple groups. Whether the covariances were adjusted determined by the following principle: when added to this model, changed the matched odds ratio by at least 10% [22]. For assessing the association between DOBS and sarcopenia, we employed logistic regression analysis to estimate β-coefficients, representing the odds ratios for the likelihood of sarcopenia across different DOBS levels. This approach was complemented by a two-piecewise linear regression model to investigate potential threshold effects where the relationship between DOBS and sarcopenia might change at specific DOBS values. A two-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

In the 2011–2018 NHANES study involving 8,240 participants, 702 individuals (8.5%) were diagnosed with sarcopenia. The characteristics of these participants are detailed in Table 2. The prevalence of sarcopenia increased across DOBS quartiles: Quartile 1 (lowest DOBS): 5.2%, Quartile 2: 7.8%, Quartile 3: 9.6%, and Quartile 4 (highest DOBS): 11.5%. Analysis revealed no significant differences in age(p = 0.126), diabetes(p = 0.363), cardiovascular disease (P = 0. 594), self-reported cancer(P = 0.064), alcohol consumption(p = 0.166), physical activity status(p = 0.279), and hypertension(p = 0.170) among the different DOBS groups. In contrast, those who adhered to a pro-oxidative diet, compared to participants consuming antioxidant-rich diets, were predominantly female, had a higher BMI, had a lower socioeconomic status, and were more likely to be current smokers. However, it’s noteworthy that educational attainment shows a contrasting trend; there are actually more individuals with college degrees or higher education in the higher DOBS quartiles. The differences in DOBS quartiles across ethnic groups (P < 0.001) are particularly notable. The data indicates that the distribution of DOBS varies significantly by ethnicity, suggesting that dietary patterns contributing to oxidative balance may be culturally or regionally influenced. The p-value is < 0.001 for nutrient supplement use across DOBS quartiles, indicating significant variations. The data shows an increase in the percentage of participants reporting nutrient supplement use as the DOBS quartile increases. This may suggest that individuals with a higher intake of dietary supplements are also those who engage in dietary behaviors that improve the DOBS.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

| DBOS quartile | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 2067 | 1969 | 2217 | ||

| Age | 38.84 ± 11.72 | 39.18 ± 11.45 | 39.67 ± 11.33 | 39.43 ± 11.47 | 0.126 |

| Poverty level index | 2.18 ± 1.58 | 2.51 ± 1.63 | 2.67 ± 1.66 | 2.81 ± 1.69 | < 0.001 |

| < 1 | 555 (27.93%) | 463 (22.40%) | 379 (19.25%) | 390 (17.59%) | |

| ≥ 1, < 3 | 853 (42.93%) | 819 (39.62%) | 782 (39.72%) | 827 (37.30%) | |

| ≥ 3 | 579 (29.14%) | 785 (37.98%) | 808 (41.04%) | 1000 (45.11%) | |

| BMI | 29.41 ± 7.17 | 29.20 ± 7.11 | 28.76 ± 6.68 | 28.29 ± 6.42 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | ||||

| Male | 607 (30.55%) | 889 (43.01%) | 1026 (52.11%) | 1437 (64.82%) | |

| Female | 1380 (69.45%) | 1178 (56.99%) | 943 (47.89%) | 780 (35.18%) | |

| Ethnicity | < 0.001 | ||||

| Mexican American | 218 (10.97%) | 283 (13.69%) | 306 (15.54%) | 372 (16.78%) | |

| Other Hispanic | 190 (9.56%) | 212 (10.26%) | 214 (10.87%) | 207 (9.34%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 741 (37.29%) | 743 (35.95%) | 694 (35.25%) | 848 (38.25%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 530 (26.67%) | 442 (21.38%) | 371 (18.84%) | 355 (16.01%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 213 (10.72%) | 295 (14.27%) | 311 (15.79%) | 352 (15.88%) | |

| Other Race | 95 (4.78%) | 92 (4.45%) | 73 (3.71%) | 83 (3.74%) | |

| Educational level | < 0.001 | ||||

| Less than 9th grade | 88 (4.43%) | 129 (6.24%) | 123 (6.25%) | 109 (4.92%) | |

| 9-11th grade | 302 (15.20%) | 242 (11.71%) | 204 (10.36%) | 181 (8.16%) | |

| High school graduate/GED or equivalent | 470 (23.65%) | 461 (22.30%) | 405 (20.57%) | 409 (18.45%) | |

| Some college | 751 (37.80%) | 702 (33.96%) | 599 (30.42%) | 683 (30.81%) | |

| College graduate or above | 376 (18.92%) | 533 (25.79%) | 638 (32.40%) | 835 (37.66%) | |

| Diabetes status | 0.363 | ||||

| Yes | 170 (8.56%) | 150 (7.26%) | 133 (6.75%) | 169 (7.62%) | |

| No | 1783 (89.73%) | 1883 (91.10%) | 1794 (91.11%) | 2004 (90.39%) | |

| Borderline | 34 (1.71%) | 34 (1.64%) | 42 (2.13%) | 44 (1.98%) | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.594 | ||||

| Yes | 24 (1.21%) | 22 (1.06%) | 18 (0.91%) | 18 (0.81%) | |

| No | 1963 (98.79%) | 2045 (98.94%) | 1951 (99.09%) | 2199 (99.19%) | |

| Self-reported cancer | 0.064 | ||||

| Yes | 97 (4.88%) | 88 (4.26%) | 70 (3.56%) | 76 (3.43%) | |

| No | 1890 (95.12%) | 1979 (95.74%) | 1899 (96.44%) | 2141 (96.57%) | |

| Hypertension status | 0.170 | ||||

| Yes | 497 (25.01%) | 490 (23.71%) | 469 (23.82%) | 490 (22.10%) | |

| No | 1490 (74.99%) | 1577 (76.29%) | 1500 (76.18%) | 1727 (77.90%) | |

| Nutrient supplement use status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 509 (25.62%) | 577 (27.91%) | 639 (32.45%) | 849 (38.29%) | |

| No | 1478 (74.38%) | 1490 (72.09%) | 1330 (67.55%) | 1368 (61.71%) | |

| Smoking status | < 0.001 | ||||

| Current | 476 (23.96%) | 385 (18.63%) | 319 (16.20%) | 274 (12.36%) | |

| Former | 1265 (63.66%) | 1348 (65.22%) | 1292 (65.62%) | 1481 (66.80%) | |

| Never smoker | 246 (12.38%) | 334 (16.16%) | 358 (18.18%) | 462 (20.84%) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 0.166 | ||||

| Non-drinker | 285 (14.34%) | 301 (14.56%) | 271 (13.76%) | 273 (12.31%) | |

| 1 to < 5 drinks/month | 1484 (74.69%) | 1491 (72.13%) | 1434 (72.83%) | 1664 (75.06%) | |

| 5 to < 10 drinks/month | 106 (5.33%) | 135 (6.53%) | 124 (6.30%) | 132 (5.95%) | |

| 10 + drinks/month | 112 (5.64%) | 140 (6.77%) | 140 (7.11%) | 148 (6.68%) | |

| Physical activity | 0.279 | ||||

| Vigorous | 342 (17.21%) | 404 (19.55%) | 366 (18.59%) | 417 (18.81%) | |

| Moderate | 871 (43.83%) | 841 (40.69%) | 838 (42.56%) | 967 (43.62%) | |

| Light | 774 (38.95%) | 822 (39.77%) | 765 (38.85%) | 833 (37.57%) |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentage. Q, quartile; BMI, body mass index.DOBS: dietary oxidative balance score. Statistical analysis: One-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Significance level: P < 0.01 (two-tailed). Bold values indicate statistical significance

The results of association between DOBS and sarcopenia

Following our focused analysis on the association between DOBS and sarcopenia using multivariate methodologies, we ensured a thorough control for various confounders, furthering the reliability of our findings, with results detailed in Table 3. The crude model showed a positive association between DOBS and sarcopenia (β = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96 to 0.99, P < 0.001). This association remained largely unchanged in the model adjusted minimally for age and gender (β = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.96to 0.98, P < 0.001), and in the fully adjusted model including additional covariates (β = 0.97, 95%CI: 0.96 to 0.98, P < 0.001). In the categorical analysis of DOBS, participants were divided into quartiles. The association between DOBS quartiles and sarcopenia were evaluated using multivariate regression models. In the unadjusted model for DOBS quartiles, Quartiles 2 and 3 showed no significant association, while Quartile 4 (0.65; 95% CI: 0.52–0.81; p < 0.001) exhibited a significantly lower risk, suggesting a stronger negative association as DOBS increases. The pattern in the minimally adjusted model remained similar to the unadjusted model, with Quartile 4 exhibiting a substantial decrease in risk (0.60; 95% CI: 0.48–0.76; p < 0.001). In the fully adjusted model for DOBS quartiles, Quartile 4 again exhibited a significant decrease in risk (0.65; 95% CI: 0.51–0.82; p < 0.001) compared to Quartile 1, the reference group. A trend analysis confirmed a significant positive trend (p for trend < 0.001) across increasing DOBS quartiles. These results suggest that higher DOBS is associated with a statistically significant increase in the likelihood of sarcopenia, with the strongest association observed in the highest DOBS quartile.

Table 3.

Relationship between DOBS and Sarcopenia in different models

| Variable | Crude model (β, 95%CI, P) | Minimally adjusted model (β, 95%CI, P) | Fully adjusted model(β, 95%CI, P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DBOS | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) < 0.001 | 0.97(0.96, 0.99) < 0.001 |

| DBOS quartile | |||

| Q1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Q2 | 0.93 (0.75, 1.14) 0.500 | 0.90 (0.72, 1.11) 0.341 | 0.92 (0.74, 1.14) 0.482 |

| Q3 | 0.87(0.70, 1.08) 0.220 | 0.82 (0.65, 1.02) 0.080 | 0.86 (0.69, 1.08) 0.217 |

| Q4 | 0.65 (0.52, 0.81) < 0.001 | 0.60 (0.46, 0.76) < 0.001 | 0.65 (0.51, 0.82) < 0.001 |

| P for trend | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Crude model: we did not adjust other covariates

Minimally adjusted model: we adjusted age and gender

Fully adjusted model: we adjusted age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, PIR, nutrient supplement use, self-reported cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes

CI: confidence interval; DOBS: dietary oxidative balance score; PIR: poverty income ratio

Significance level: P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Bold values indicate statistical significance

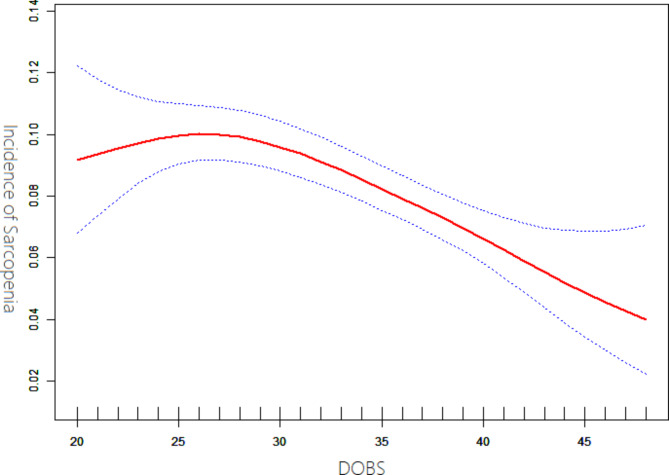

The results of non-linear relationship

Our study, illustrated in Fig. 2, revealed a non-linear association between DOBS and sarcopenia, controlling for variables such as age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, PIR, nutrient supplement use, self-reported cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. Employing a two-piecewise linear regression model, we identified an inflection point at a DOBS of 23. To the left of this point, the effect size was 1.62 (95% CI: 1.09 to 2.41, P = 0.016). On the right side of the inflection point, significant interactions between DOBS and sarcopenia were observed, with an effect size of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.95 to 0.98, P < 0.001), as detailed in Table 4.

Fig. 2.

Association between DOBS and incidence of sarcopenia. Model adjusted for age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, PIR, nutrient supplement use, self-reported cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes

Table 4.

The results of the non-linear relationship between DOBS and Sarcopenia

| Inflection point of DOBS | Effect size (β) | 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 23 | 1.62 | 1.09, 2.41 | 0.016 |

| ≥ 23 | 0.97 | 0.95, 0.98 | < 0.001 |

Effect: sarcopenia, Cause: DOBS

Adjusted: age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, PIR, nutrient supplement use, self-reported cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes

Statistical analysis: Two-piecewise linear regression. Significance level: P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Bold values indicate statistical significance

CI: confidence interval; DOBS: dietary oxidative balance score; PIR: poverty income ratio

The results of subgroup analyses

Sub-group analyses, detailed in Table 5, indicated that the association between DOBS and sarcopenia did not differ significantly across subgroups defined by age, gender diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, self-reported cancer, hypertension, and nutrient supplement use status (all p-values for interaction > 0.05).

Table 5.

Effect size of DOBS on Sarcopenia in prespecified and exploratory subgroups

| Characteristic | Number of Participants (%) | Effect Size (95% CI) | P-value | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.77 | |||

| < 39 | 3,120 (38%) | 0.971(0.950, 0.993) | 0.017 | |

| ≥ 39 | 5,120 (62%) | 0.975(0.959, 0.992) | 0.022 | |

| Gender | 0.62 | |||

| Male | 3,959 (48%) | 0.976 (0.958, 0.995) | 0.013 | |

| Female | 4,281 (52%) | 0.969 (0.951, 0.989) | 0.009 | |

| Diabetes | 0.30 | |||

| Yes | 622 (7.5%) | 0.986 (0.951, 1.023) | 0.281 | |

| No | 7,222 (87.6%) | 0.972 (0.958, 0.987) | 0.015 | |

| Borderline | 396 (4.8%) | 0.924(0.856, 0.997) | 0.034 | |

| Hypertension | 0.93 | |||

| Yes | 1,946 (23.6%) | 0.972 (0.949, 0.996) | 0.021 | |

| No | 6,294 (76.4%) | 0.973 (0.958, 0.989) | 0.018 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 0.79 | |||

| Yes | 82 (1%) | 0.987(0.882, 1.104) | 0.736 | |

| No | 8,158 (99%) | 0.972(0.959, 0.986) | 0.012 | |

| Self-reported cancer | 0.53 | |||

| Yes | 331 (4%) | 0.992(0.931, 1.058) | 0.668 | |

| No | 7,909 (96%) | 0.972(0.958, 0.985) | 0.010 | |

| Nutrient supplement use | 0.15 | |||

| Yes | 2,574 (31.2%) | 0.958 (0.935, 0.983) | 0.001 | |

| No | 5,666 (68.8%) | 0.979 (0.963, 0.993) | 0.007 |

Note 1: Above model adjusted for age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, education level, PIR, nutrient supplement use, self-reported cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes

Note 2: In each case, the model is not adjusted for the stratification variable

Statistical analysis: stratified linear regression models. Significance level: P < 0.05 (two-tailed). Bold values indicate statistical significance

CI: confidence interval; DOBS: dietary oxidative balance score

Discussion

Utilizing a cross-sectional analysis of representative samples from the NHANES cohort, our study uncovered a reverse U-shaped correlation between the dietary oxidative balance score (DOBS) and sarcopenia. Subgroup analyses further confirmed the stability of this relationship. These findings highlight the significance of maintaining an antioxidant-rich diet for adult muscle health. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the potential link between DOBS and sarcopenia in adults. Previous studies, such as those by Küükdiler et al. and Mahmoodi et al., have explored the association between oxidative stress, antioxidant status, and sarcopenia. Küçükdiler et al. [15] focused on older diabetic patients and suggested that oxidative stress and the imbalance between oxidant and antioxidant systems could be pivotal in the development of sarcopenia. Similarly, the initial findings of Mahmoodi et al. [14] indicated a protective effect of higher OBS levels against sarcopenia among older adults, although these associations lost statistical significance upon adjusting for confounders such as age, diet, and lifestyle factors. Our study supports these findings to some extent and extends them by providing a statistically robust analysis with a significant sample size from a nationally-representative dataset. Particularly distinctive in our study is the identification of an inflection point (DOBS = 23) where the benefits of dietary oxidative balance are observed to significantly rise. This non-linear association highlights a potential threshold effect, suggesting that dietary quality may begin to notably impact muscle health.

Recent studies have underscored the critical roles of oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in muscle atrophy [23]. These factors interact and potentially converge on multiple intracellular signaling pathways, thereby disrupting the balance between protein synthesis and degradation, thereby triggering apoptosis – a key mechanism leading to significant muscle mass loss [24]. Importantly, these factors implicated in sarcopenia do not operate in isolation; rather, their causal pathways frequently intersect or overlap, particularly in the context of oxidative stress. The damaging effects of high levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) on macromolecules such as lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins are well-documented [25]. Under normal physiological conditions, the generation of reactive species is tightly controlled by scavenging systems; however, an excess of oxidants can lead to oxidative stress, resulting in damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids. This is particularly evident in lipid and protein oxidation, which can disrupt mitochondrial metabolism and cause bioenergetic impairment, ultimately linked to decreased muscle mass and strength [26]. Collectively, the impact of oxidative stress in skeletal muscle may culminate in mitochondrial dysfunction, a decrease in protein synthesis, an increase in protein degradation, and apoptosis. This occurs through the modulation of critical signaling pathways, ultimately resulting in diminished muscle mass.

Population-based evidence indicates that the specific manner in which food is consumed profoundly impacts the balance of oxidative stress, which is attributable to the antioxidant qualities of various nutrients [27]. Dietary components with direct effects include those with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities, such as beta-carotene [28] and zinc [29]. Proteins, fats, and cholesterol, known for potentially causing inflammation or oxidation, also play a significant role. Indirect dietary components encompass nutrients that influence gut microbiota composition and metabolites, such as dietary fiber [30] and probiotic [31]. Furthermore, poor dietary habits like high-fat, high-sugar, or low-fiber diets may escalate inflammation and oxidative stress levels [32]. Dietary adjustment is recognized as a crucial strategy for the prevention and treatment of diseases [33], and its application in various diseases has been demonstrated to yield numerous health benefits [34].

In regular diets, multiple nutrients are consumed together, leading to complex interactions that challenge the isolation of individual effects of dietary antioxidants on health outcomes. Geurtsen et al. [35] recent review underscore and γ-glutamyltransferase that glutathione, when combined with vitamin C or E, reduces mitochondrial DNA damage, unlike when used alone. Rebrin et al. [35]studied the impact of a mix of antioxidants on oxidative stress in skeletal muscle and mitochondria of senescence-accelerated mice. These mice, fed with vitamins E and C, bioflavonoids, polyphenols, and carotenoids for 10 months, showed significantly increased glutathione activity and a reductive shift in its redox state compared to controls. Therefore, evaluating dietary oxidative stress on muscle health is more effective through a comprehensive index like DOBS, rather than a single antioxidant. Notably, DOBS has been shown to negatively correlate with classic oxidative stress markers likerum F2-isoprostanes and gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) [36]. This means that individuals with higher DOBS scores, indicative of a more antioxidant- diet, tend to have lower levels of these oxidative stress markers. This negative correlation supports the validity of DOBS as a measure of dietary oxidative balance and its potential impact on oxidative stress in the body. However, it is important to that while these correlations have been reported in previous studies, we did not directly assess these markers in our current study due to data constraints.

Some studies have focused on the overall impact of the oxidative balance score (OBS), which encompasses both DOBS and lifestyle OBS. It’s important to note that dietary components usually contribute to over 75% of the total OBS in most studies, indicating a significant emphasis on dietary factors [37]. Moreover, the mechanisms by which lifestyle OBS components, such as obesity and physical activity, affect sarcopenia are multifaceted. For instance, physical activity’s role in reducing sarcopenia might be more attributable to the intensity and duration of resistance exercise than to its antioxidant effects [38]. Therefore, our approach is to specifically examine the effects of DOBS on sarcopenia, treating non-dietary factors, which are a smaller part of OBS, as covariates to reduce potential bias as much as possible.

This study has notable strengths. Firstly, it utilizes data from a large, nationally representative database, collected through standardized protocols that minimize biases, including selection, information, and measurement biases. Secondly, we controlled for important confounding factors in our analyses to reduce the potential for spurious associations. Thirdly, we conducted subgroup analyses to explore potential heterogeneity in the association between DOBS and sarcopenia across different sub-populations defined by demographic and health-related characteristics. However, it is important to note that subgroup analyses are exploratory and should be interpreted with caution, since they may have limited statistical power and are susceptible to multiple testing. Finally, DOBS was categorized into tertiles, and linear trend tests were performed to ensure data analysis robustness. However, the study has limitations. Firstly, its cross-sectional nature limits causal inference, highlighting the need for more prospective studies for validation. Secondly, the dietary assessment methods used in this study to collect data and calculate DOBS are prone to various sources of error, including recall bias, portion size estimation errors, social desirability bias, interviewer bias, and limitations of the nutrient database. Although covariates were adjusted for, completely eliminating potential biases caused by unmeasured confounding factors may not be possible. Thirdly, the study lacked serum antioxidant measurements and the lack of direct assessment of muscle strength or physical performance. These limitations prevent the confirmation of the physiological impact of dietary antioxidants on sarcopenia. In future studies, incorporating serum antioxidant levels and objective measures of muscle function is recommended to validate and expand upon these findings. Fourthly, While the association between DOBS and sarcopenia showed statistical significance, with a β of 0.97 (95% CI: 0.96–0.99) in the fully adjusted model, the effect size is relatively small. Given that the β value is close to 1, the clinical relevance of this association may be limited. This suggests that while DOBS may have some impact on sarcopenia risk, the magnitude of this effect might not be substantial enough to warrant significant clinical concern or intervention based solely on this factor. Finally, this study does not differentiate between primary sarcopenia, which occurs without other contributing causes, and secondary sarcopenia, which arises due to such as cancer cachexia or corticosteroid use, significantly influencing muscle health. Additionally, a subgroup analysis distinguishing these categories would offer greater insight into the effect of DOBS on different sarcopenia types. The presence of comorbidities may confound the results, making the findings more applicable to secondary sarcopenia, which should be acknowledged as a limitation. Future research should focus on more precise categorization of sarcopenia types to refine our understanding of the relationship between dietary oxidative balance and muscle deterioration.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention and the participants who enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Author contributions

Y.W.:Writing – review & editing, Data curation. S.Z.:Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Z.X.C.: Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. W.J.Z.: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision. J.S.: Data curation, Project administration, Resources. Q.Z.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the project of Wenzhou basic science and technology (grant no. Y20240652).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All data for this study were obtained from the NHANES database, and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Ethics Review Board approved the NHANES, approval no. #2005- 06, # 2011- 17. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of NCHS. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older people. 2010;39(4):412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: Revis Eur Consensus Definition Diagnosis. 2019;48(1):16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WJJTAjocn. Skeletal muscle loss: cachexia, sarcopenia, and inactivity. 2010;91(4):1123S-1127S. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Mitchell WK, Williams J, Atherton P, Larvin M, Lund J, Narici, MJFip. Sarcopenia, Dynapenia, and the impact of advancing age on human skeletal muscle size and strength; a quantitative review. 2012;3:260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Brioche T, Lemoine-Morel, SJCpd. Oxidative stress, Sarcopenia, antioxidant strategies and exercise: molecular aspects. 2016;22(18):2664–78. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ryan MJ, Jackson JR, Hao Y, Leonard SS. Alway SEJFrb, medicine. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase reduces oxidative stress and improves skeletal muscle function in response to electrically stimulated isometric contractions in aged mice. 2011;51(1):38–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Hofer T, Marzetti E, Xu J et al. Increased iron content and RNA oxidative damage in skeletal muscle with aging and disuse atrophy. 2008;43(6):563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Longo VD, Anderson RMJC. Nutrition, longevity and disease: from molecular mechanisms to interventions. 2022;185(9):1455–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Iddir M, Brito A, Dingeo G et al. Strengthening the immune system and reducing inflammation and oxidative stress through diet and nutrition: considerations during the COVID-19 crisis. 2020;12(6):1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shivappa N, Steck SE, Hurley TG, Hussey JR, Hébert JRJP. Designing and developing a literature-derived. population-based Diet Inflamm Index. 2014;17(8):1689–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hernández-Ruiz Á, García-Villanova B, Guerra-Hernández E, Amiano P, Ruiz-Canela M, Molina-Montes EJN. A review of a priori defined oxidative balance scores relative to their components and impact on health outcomes. 2019;11(4):774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang X, Hu J, Liu L et al. Association of Dietary Inflammatory Index and Dietary oxidative balance score with all-cause and Disease-Specific Mortality: findings of 2003–2014 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2023;15(14):3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Martínez CF, Esposito S, Di Castelnuovo A et al. Association between the inflammatory potential of the Diet and Biological Aging: a cross-sectional analysis of 4510 adults from the Moli-Sani Study Cohort. 2023;15(6):1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Mahmoodi M, Shateri Z, Nazari SA et al. Association between oxidative balance score and sarcopenia in older adults. 2024;14(1):5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Küçükdiler A, Varli M, Yavuz Ö et al. Evaluation of oxidative stress parameters and antioxidant status in plasma and erythrocytes of elderly diabetic patients with Sarcopenia. 2019;23(3):239–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Statistics NCfH. National health and nutrition examination survey: Analytic guidelines, 1999–2010. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Servic; 2013. [PubMed]

- 17.Johnson CL, Paulose-Ram R, Ogden CL, et al. National health and nutrition examination survey. Analytic guidelines; 2013. pp. 1999–2010. [PubMed]

- 18.Bucala RJTJoci. Diabetes, aging, and their tissue complications. 2014;124(5):1887–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. 2014;69(5):547–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Park YMM, Shivappa N, Petimar J et al. Dietary inflammatory potential, oxidative balance score, and risk of breast cancer: findings from the Sister Study. 2021;149(3):615–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhang W, Peng S-F, Chen L et al. Association between the oxidative balance score and telomere length from the national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2002. 2022;2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al. Phenylpropanolamine risk Hemorrhagic Stroke. 2000;343(25):1826–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter CS, Hofer T, Seo AY, Leeuwenburgh CJAP, Nutrition M. Molecular mechanisms of life-and health-span extension: role of calorie restriction and exercise intervention. 2007;32(5):954–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Meng S-J, Yu L-JJI. Oxidative stress, molecular inflammation and sarcopenia. 2010;11(4):1509–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Bua E, Johnson J, Herbst A et al. Mitochondrial DNA–deletion mutations accumulate intracellularly to detrimental levels in aged human skeletal muscle fibers. 2006;79(3):469–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Marzetti E, Calvani R, Cesari M et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and sarcopenia of aging: from signaling pathways to clinical trials. 2013;45(10):2288–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Calder PC, Bosco N, Bourdet-Sicard R et al. Health relevance of the modification of low grade inflammation in ageing (inflammageing) and the role of nutrition. 2017;40:95–119. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Kaulmann A. Bohn TJNr. Carotenoids, inflammation, and oxidative stress—implications of cellular signaling pathways and relation to chronic disease prevention. 2014;34(11):907–929. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Bonaventura P, Benedetti G, Albarède F. Miossec PJAr. Zinc and its role in immunity and inflammation. 2015;14(4):277–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Tao N, Gao Y, Liu Y, Ge FJA-EJA, Science E. Carotenoids from the peel of Shatian Pummelo (Citrus grandis Osbeck) and its antimicrobial activity. 2010;7(1):110–5.

- 31.Tsai Y-L, Lin T-L, Chang C-J, et al. Probiotics Prebiotics Amelioration Dis. 2019;26(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aleksandrova K, Koelman L, Rodrigues CEJR. Dietary patterns and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation: a systematic review of observational and intervention studies. 2021;42:101869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Food as medicine. : translating the evidence. Nat Med 29 2023;753–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Fontana L, Partridge LJC. Promoting health and longevity through diet: from model organisms to humans. 2015;161(1):106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Rebrin I, Zicker S, Wedekind KJ et al. Effect of antioxidant-enriched diets on glutathione redox status in tissue homogenates and mitochondria of the senescence-accelerated mouse. 2005;39(4):549–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Lakkur S, Bostick RM, Roblin D, et al. Oxidative balance score and oxidative stress biomarkers in a study of whites. Afr Americans Afr Immigrants. 2014;19(6):471–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lei X, Xu Z, Chen WJJAD. Association of oxidative balance score with sleep quality: NHANES 2007–2014. 2023;339:435–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Shojaa M, Von Stengel S, Kohl M, Schoene D, Kemmler WJOI. Effects of dynamic resistance exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis with special emphasis on exercise parameters. 2020;31:1427–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.