Abstract

Background

Numerous meta-analyses have identified various risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), prompting a comprehensive study to synthesize evidence quality and strength.

Methods

This umbrella review of meta-analyses was conducted throughout PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Evidence strength was evaluated according to the evidence categories criteria.

Results

We identified 101 risk factors throughout 175 meta-analyses. 31 risk factors were classified as evidence levels of class I, II, or III. HBV and HCV infections increase HCC risk by 12.5-fold and 11.2-fold, respectively. These risks are moderated by antiviral treatments and virological responses but are exacerbated by higher HBsAg levels, anti-HBc positivity, and co-infection. Smoking, obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, diabetes, low platelet, elevated liver enzymes and liver fluke infection increase HCC risk, while coffee consumption, a healthy diet, and bariatric surgery lower it. Medications like metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs), aspirin, statins, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors reduce HCC risk, while acid suppressive agents, particularly proton pump inhibitors, elevate it. Blood type O reduces the risk of HCC, while male gender and older age increase the risk.

Conclusions

HBV and HCV are major HCC risk factors, with risk mitigation through antiviral treatments. Lifestyle habits such as smoking and alcohol use significantly increase HCC risk, highlighting the importance of cessation. Certain drugs like aspirin, statins, GLP-1 RAs, and metformin may reduce HCC occurrence, but further research is needed to confirm these effects.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, risk factor, incidence, umbrella review

Introduction

Highlighting primary liver cancer’s severity is crucial, ranking sixth in global prevalence and third in lethality [1]. Projections suggest 1.4 million new cases and 1.3 million fatalities by 2040 [2]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constitutes about 90% of cases [3], with closely aligned incidence and mortality rates emphasizing its significant threat [4]. HCC primarily affects adults aged 60 to 70, with a marked male predominance [5]. High HCC incidences are reported in regions with high hepatitis B and C prevalence, like East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, while Western countries see rising cases due to increasing obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus prevalence [6].

The causes of HCC are varied, including chronic viral hepatitis, excessive alcohol intake, aflatoxin exposure, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and metabolic syndromes. Preventive measures targeting these factors and regular screenings are essential [7]. Prevention involves hepatitis B vaccination, antiviral therapy, lifestyle changes for obesity and metabolic syndrome, and reducing alcohol and aflatoxin exposure [8–11]. Primary prevention aims to address HCC’s root causes, leading to reduced disease burden, better outcomes, and lower healthcare costs [12,13].

Despite extensive research, a thorough categorization of HCC risk factors is lacking. While numerous meta-analyses have identified various factors associated with HCC, there is still a need for a comprehensive synthesis of evidence. The declining incidence of HCC due to hepatitis B vaccination and improved antiviral treatments highlights the importance of addressing other contributing risk factors [14]. Our objective is to consolidate existing evidence, categorize pertinent risk factors, and propose precise preventive strategies aimed at enhancing comprehension of HCC etiology and mitigating its global burden.

Methods

Umbrella review methods

We rigorously analyzed data from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses on risk factors associated with HCC in this umbrella review [15,16]. This study was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The study was previously registered on PROSPERO (CRD42023454708) (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). Patient participation was not directly involved in this study, which relied on secondary data analysis. Therefore, there was no need for patient engagement to guide interpretation or contribute to manuscript preparation.

Literature search

We have developed a comprehensive and systematic search strategy to identify relevant literature. The search encompassed multiple databases-PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews-spanning from their inception to December 2024. We employed a search strategy using terms such as “hepatocellular carcinoma,” “risk,” and “incidence” to locate systematic reviews and meta-analyses across all fields. Additionally, we thoroughly examined the citations in the retrieved eligible papers to find any relevant publications possibly overlooked in the initial database searches.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria were meticulously defined to systematically assess non-genetic risk factors associated with HCC incidence. Included were systematic reviews or meta-analyses that analyzed data from human randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or observational studies. Specifically, meta-analyses were eligible if they reported estimated summary effect measures (e.g. risk ratios (RRs), odds ratios (ORs), hazard ratios (HRs), weighted mean differences (WMDs), or standardized mean differences (SMDs)) along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Studies on genetic factors, hepatic pathologies beyond HCC (benign or malignant), and those primarily focusing on the prognosis of HCC patients were excluded. Systematic reviews lacking meta-analyses and those failing to provide comprehensive study-specific data, such as risk estimates with corresponding 95% CIs also were excluded. The studies with unavailable data were also omitted. In cases of multiple meta-analyses on the same risk factor, we prioritized studies without population restrictions in our selection process. The latest meta-analysis was chosen for publications exceeding a two-year interval. If the interval was less than two years, the study with a larger number of analyzed studies was selected. In instances of an equal number of studies, preference was given to those with more prospective studies. Two independent reviewers (JW and YG) screened titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third reviewer (SZ).

Data extraction

We meticulously extracted key data from eligible studies, including the first author’s name, publication year, exposure contrast, number of cases and participants, and summary effect estimate. Additionally, we recorded details such as the number of studies in each meta-analysis, their design, and the effects model employed. Statistical metrics, including I2 statistic and P values from Cochran’s Q and Egger’s tests, were analyzed to assess heterogeneity and potential publication bias. We also extracted additional data from studies conducting dose-response and subgroup analyses, including P values for nonlinearity tests and specific subgroup results.

Evaluation of the quality of included meta-analyses and evaluation of the strength of evidence

We employed the AMSTAR (a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews), recognized for its efficacy in evaluating the methodological rigor of systematic reviews, to assess the methodological quality of the included meta-analyses [17,18].

The evaluation of evidence strength for each identified risk factor linked to HCC was conducted meticulously. We categorized the evidence into five distinct classes based on comprehensive criteria: Class I for convincing evidence, Class II for highly suggestive evidence, Class III for suggestive evidence, Class IV for weak evidence, and non-significant findings. Factors considered in classification encompassed case and participant numbers, statistical significance, small study effects, excess significance bias, 95% prediction interval, and between-study heterogeneity (Table 1) [19].

Table 1.

Evidence categories criteria.

| Evidence class | Description |

|---|---|

| Class I: convincing evidence | >1000 cases (or >20,000 participants for continuous outcomes), statistical significance at p < 10−6 (random-effects), no evidence of small-study effects and excess significance bias; 95% prediction interval excluded the null, no large heterogeneity (I2 < 50%) |

| Class II: highly suggestive evidence | >1000 cases (or >20,000 participants for continuous outcomes), statistical significance at p < 10−6 (random-effects) and largest study with 95% CI excluding the null value |

| Class III: suggestive evidence | >1000 cases (or >20,000 participants for continuous outcomes) and statistical significance at p < 0.001 |

| Class IV: weak evidence | The remaining significant associations with p < 0.05 |

| NS: non-significant | p > 0.05 |

Data analysis

We performed a reassessment of RRs, ORs, HRs, WMDs, and SMDs, along with their corresponding 95% CIs, within each meta-analysis that reported these parameters, alongside the original studies’ case and participant numbers. This reanalysis was conducted utilizing either random or fixed effects models, depending on the specific context. Moreover, we evaluated heterogeneity utilizing the I2 statistic and Cochran’s Q test, and when feasible, we applied Egger’s regression test to examine small study effects [20]. Egger’s test was used when at least ten studies were included. Sensitivity analyses were performed for outcomes categorized as Class I, II, or III in evidence strength, where data sufficed. This step was crucial for assessing if excluding specific studies affected the credibility of the evidence.

In cases where the most recent meta-analysis omitted earlier articles, we integrated their data for reanalysis. If reanalysis proved unfeasible, we extracted summary data and thoroughly evaluated heterogeneity and publication bias. Significance thresholds were set at p < 0.10 for heterogeneity tests and p < 0.05 for all other analyses. Review Manager 5.4 facilitated evidence synthesis, while Stata 12.1 supported Egger’s test and sensitivity analysis.

Results

Characteristics of meta-analyses

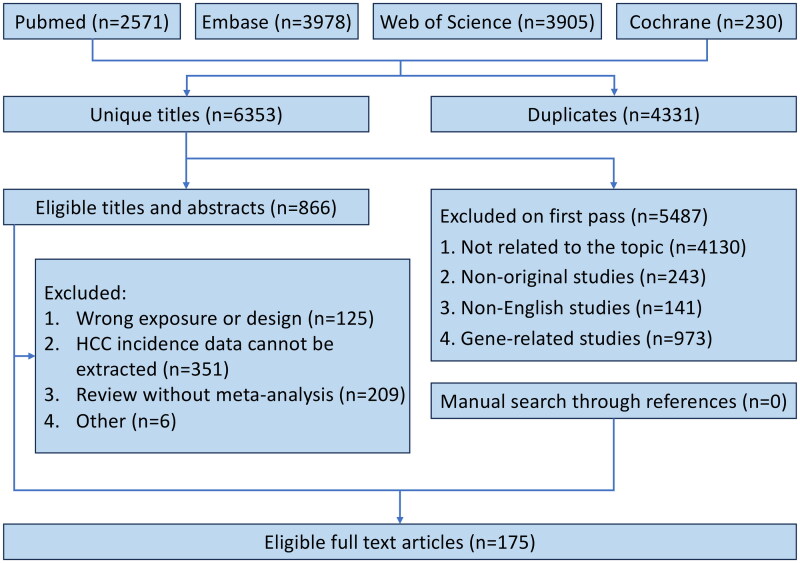

The literature search and selection process illustrated in Figure 1, initially identified 10684 articles. After rigorous screening, 175 meta-analyses were identified, with 6 of them being meta-analyses of RCTs.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of systematic search and selection process.

Our comprehensive analysis identified 101 distinct risk factors for HCC incidence, with 73 being statistically significant, as shown in Table 2. Of these, 48 were associated with increased HCC risk, while 25 appeared to decrease it. However, 28 risk factors did not reach statistical significance. After a quality assessment using our evidence categories criteria, the majority of these risk factors were categorized as either class IV or having non-significant (NS) evidence. Notably, only 31 risk factors, comprising 30.7% of the total, were classified as class I, class II, or class III evidence. Among these, 8 were linked to Hepatitis B virus or Hepatitis C virus.

Table 2.

Summary of risk factors associated with hepatocellular carcinoma incidence.

| Risk factor | Total eligible MA | Included MA | Exposure contrast | No. of Case/cohort | MA metric | Estimate [95% CI] | No. of studies (T/R/C/P) | Effects model | I2, Q test P value | Egger test P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant associations | ||||||||||

| Acid suppressive agent | 1 | Song 2020 | Any versus none | 42899/802342 | RR | 1.40 [1.17 to 1.68] | 5/0/4/1 | Random | 57%, 0.06 | NA |

| Adiponectin | 2 | Zhang 2020 | 1 μg/ml increment | 261/1064 | OR | 1.066 [1.03 to 1.11] | 4/0/0/4 | Fixed | NA, 0.338 | NA |

| Aflatoxin | 3 | Liu 2012 | Any versus none | 1000/3069 | OR | 4.75 [2.78 to 8.11] | 9/0/1/8 | Random | 75.56%, < 0.000 | NA |

| Age | 3 | Yin 2024 | Elderly versus young | 1191/466425 | HR | 1.81 [1.51 to 2.17] | 10/0/10/0 | Random | 96.5%, 0.000 | NA |

| Alcohol | 7 | Li 2011 | Any versus none | 3812/14739 | OR | 1.56 [1.16 to 2.09]* | 18/0/0/18 | Random | 83%, <0.00001 | NA |

| Alpha-glucosidase Inhibitors | 1 | Arvind 2021 | Any versus none | 11069/56791 | OR | 1,08 [1.02 to 1.14] | 3/0/0/3 | Random | 21%, 0.28 | 0.32 |

| Anti-HBc | 1 | Coppola 2016 | Any versus none | 2521/44553 | RR | 1.67 [1.44 to 1.95] | 26/0/16/10 | Random | 75.7%, <0.001 | NA |

| Antiviral therapy for HCV | 11 | Bang 2017 | Any versus none | 1759/15701 | OR | 0.392 [0.275 to 0.557] | 25/3/22/0 | Random | 86.881%, <0.001 | 0.11 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase-to-Platelet Ratio Index (posttreatment) | 1 | Zhang 2019 | Highest versus lowest | 124/2884 | HR | 3.69 [2.52 to 5.42] | 5/0/5/0 | Fixed | 7.8%, 0.362 | 0.031 |

| Aspartate Aminotransferase-to-Platelet Ratio Index (pretreatment) | 1 | Zhang 2019 | Highest versus lowest | 494/7398 | HR | 2.56 [1.78 to 3.68] | 11/0/11/0 | Random | 71.5%, 0.000 | 0.039 |

| Aspirin | 19 | Ma 2023 | Any versus none | 126739/3745832 | HR | 0.75 [0.71 to 0.80] | 24/0/20/4 | Random | 95%, <0.0001 | < 0.001 |

| Bariatric surgery | 2 | Ramai 2021 | Any versus none | NA /3249691 | OR | 0.63 [0.53 to 0.75] | 5/0/4/1 | Random | 79%, <0.00001 | NA |

| Black race | 1 | Lu 2022 | Black versus white | 4359/23952 | OR | 2.42 [1.10 to 5.31] | 5/0/0/5 | Random | 95.2%, 0.000 | NA |

| Blood type O | 1 | Liu 2018 | Type O versus non type O | 1960/94807 | OR | 0.76 [0.66 to 0.87] | 4/0/1/3 | Random | 0%, 0.55 | NA |

| Carvedilol | 1 | He 2023 | Any versus none | NA/17574 | OR | 0.62 [0.52 to 0.74] | 6/3/3/0 | Random | 0.0%, 0.776 | 0.786 |

| Clusterin | 1 | Namdar 2022 | HCC versus Non-cancer | 359/547 | SMD | 1.89 [0.76 to 3.03] | 6/0/0/6 | Random | 96.28%, <0.001 | 0.01 |

| Coffee | 7 | Yu 2023 | Highest versus lowest | 5980/2494279 | RR | 0.53 [0.47 to 0.59] | 21/0/13/8 | Fixed | 0.00%, 0.634 | 0.002 |

| Dairy intake | 1 | Zhou 2017 | Highest versus lowest | 2041/1084666 | RR | 1.38 [1.00 to 1.91] | 8/0/3/5 | Random | 78.5%, 0.000 | >0.1 |

| Diabetes | 19 | Wang, P 2012 | Any versus none | 33765/7271652 | RR | 2.31 [1.87 to 2.84] | 42/0/25/17 | Random | NA, <0.01 | 0.1228 |

| Dietary approaches to stop hypertension | 1 | Shu 2024 | Highest adherence versus lowest adherence | 1326/406292 | HR | 0.77 [0.66 to 0.91] | 4/0/4/0 | Random | 0.6%, 0.389 | NA |

| Dyslipidemia | 3 | Xiao 2024 | Any versus none | 2946/1237460 | RR | 0.78 [0.65 to 0.93] | 15/0/11/4 | Random | 86%, <0.01 | 0.058 |

| Education (illiteracy) | 1 | Lu 2022 | Illiteracy versus ever educated | 3686/14761 | OR | 1.37 [1.00 to 1.89] | 11/0/011 | Random | 85.6%, 0.000 | 0.803 |

| Elevated liver enzymes | 1 | Guo 2023 | Any versus none | 1785/421559 | OR | 2.92 [2.37 to 3.59] | 7/0/6/1 | Fixed | 33%, 0.17 | 0.257 |

| Family history of HCC | 1 | Lyu 2016 | Any versus none | 995/4524 | OR | 3.58 [2.53 to 5.06] | 7/0/2/5 | Fixed | 0%, 0.49 | 0.81 |

| Farmer | 1 | Lu 2022 | Any versus none | 3453/7449 | OR | 1.49 [1.06 to 2.08] | 13/0/0/13 | Random | 80.6%, 0.000 | 0.31 |

| Fish | 5 | Yu 2022 | Highest versus lowest | 2554/1231551 | RR | 0.91 [0.86 to 0.96] | 9/0/5/4 | Fixed | 40.90%, 0.095 | 0.066 |

| Gender | 8 | Guo 2023 | Male versus female | 2205/702967 | OR | 2.45 [2.03 to 2.97] | 11/0/6/5 | Fixed | 50%, 0.03 | 0.118 |

| GLP-1 RAs | 2 | Shabil 2024 | Any versus none | NA/5387826 | HR | 0.41 [0.28 to 0.55] | 7/0/7/0 | Random | 74%, <0.01 | NA |

| Green tea | 2 | Yu 2023 | Highest versus lowest | 6985/1482343 | RR | 0.80 [0.67 to 0.95] | 18/0/14/4 | Random | 72.30%, <0.001 | 0.215 |

| HBcrAg | 1 | Cao 2024 | Highest versus lowest | NA/8836 | HR | 3.12 [2.40 to 4.06] | 12/0/12/0 | Random | 43.2%, 0.043 | 0.381 |

| HBeAg seroconversion | 2 | Zhou 2018 | Any versus none | 113/2173 | RR | 0.60 [0.39 to 0.92] | 9/0/9/0 | Fixed | 2%, 0.42 | 0.53 |

| HBsAg level | 2 | Thi Vo 2019 | Highest versus lowest | 1840/11962 | OR | 2.46 [2.15 to 2.83] | 8/0/6/2 | Fixed | 50%, 0.05 | 0.3647 |

| HBsAg seroclearance | 3 | Anderson 2021 | Any versus none | NA/187783 | RR | 0.30 [0.20 to 0.43] | 26/1/25/0 | Random | NA, NA | NA |

| HBV | 7 | Cho 2011 | Any versus none | 9059/1550271 | OR | 13.5 [9.5 to 19.1] | 47/0/10/37 | Random | NA, NA | NA |

| HBV and HCV double infection | 4 | Cho 2011 | Any versus none | 3878/24223 | OR | 51.1 [33.7 to 77.6] | 22/0/2/20 | Random | NA, NA | NA |

| HBV DNA level | 2 | Chen 2016 | 6.5 log10 copies/ml versus 2 log10 copies/ml | 1162/9365 | RR | 3.06 [1.11 to 8.44] | 9/0/4/5 | Random | 56%, NA | 0.76 |

| HCV | 7 | Cho 2011 | Any versus none | 6572/97114 | OR | 12.2 [9.2 to 16.2] | 41/0/4/37 | Random | NA, NA | <0.05 |

| HDV and HBV double infection | 4 | Alfaiate 2020 | Any versus none | NA/98289 | OR | 1.28 [1.05 to 1.57] | 93/0/25/68 | Random | 67.0%, 0.01 | 0.84 |

| HEV | 1 | Yin 2023 | Any versus none | 1873/10552 | OR | 1.94 [1.26 to 3.00] | 7/0/0/7 | Random | 92.41%, 0.00 | 0.1 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 2 | Madala 2021 | Any versus none | 866/4451 | OR | 4.75 [3.06 to 7.37] | 26/0/1/25 | Random | 69%, <0.01 | 0.00003 |

| Healthy eating index | 1 | Shu 2024 | Highest versus lowest | 2050/901954 | HR | 0.67 [0.54 to 0.85] | 7/0/6/1 | Random | 74.7%, 0.001 | NA |

| Income | 1 | Lu 2022 | Lowest versus highest | 4573/18583 | OR | 1.74 [1.00 to 3.03] | 9/0/0/9 | Random | 95.8%, 0.000 | NA |

| Insulin | 1 | Singh 2013 | Any versus none | 22611/240220 | OR | 2.61 [1.46 to 4.65] | 7/0/2/5 | Random | 88%, <0.01 | NA |

| Labor | 1 | Lu 2022 | Any versus none | 2405/5482 | OR | 1.52 [1.07 to 2.18] | 6/0/0/6 | Random | 71.3%, 0.004 | NA |

| Leptin | 1 | Zhang 2020 | HCC versus Non-cancer | 640/1896 | SMD | 1.83 [1.09 to 2.58] | 12/0/1/11 | Random | 97.5%, 0.000 | 0.025 |

| Liver fibrosis | 3 | Guo 2023 | Any versus none | 469/5763 | OR | 6.40 [3.89 to 10.53] | 12/0/11/1 | Random | 63%, 0.002 | 0.000 |

| Liver fluke | 1 | Xia 2015 | Any versus none | 1597/3534 | OR | 4.69 [2.32 to 9.49] | 7/0/0/7 | Random | 79%, <0.0001 | NA |

| Low albumin | 1 | Guo 2023 | Any versus none | 185/10185 | OR | 2.11 [1.11 to 4.00] | 4/0/4/0 | Fixed | 0%, 0.80 | 0.183 |

| Low platelet | 1 | Guo 2023 | Any versus none | 1353/17361 | OR | 4.61 [2.81 to 7.56] | 6/0/6/0 | Fixed | 0%, 0.79 | 0.029 |

| Mediterranean diet | 1 | Shu 2024 | Any versus none | 1848/902006 | HR | 0.65 [0.56 to 0.75] | 6/0/5/1 | Random | 0.0%, 0.757 | 0.436 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 4 | Chen 2018 | Any versus none | 1053/127198 | RR | 1.43 [1.19 to 1.72] | 6/0/6/0 | Random | 29%, 0.19 | 0.64 |

| Metformin | 8 | Li 2022 | Any versus none | NA/1452265 | RR | 0.59 [0.51 to 0.68] | 24/0/15/9 | Random | 96.5%, 0.000 | 0.034 |

| Nadolol | 1 | He 2023 | Any versus none | NA/7865 | OR | 0.74 [0.64 to 0.86] | 7/5/2/0 | Random | 0.0%, 0.796 | 0.786 |

| NAFLD | 3 | Petrelli 2022 | Any versus none | 14805/715099 | HR | 1.88 [1.46 to 2.42] | 43/0/42/1 | Random | 96%, <0.00001 | 0.18 |

| Obesity | 9 | Yang 2020 | Any versus none | NA/2354579 | RR | 1.90 [1.61 to 2.24] | 14/0/14/0 | Random | 58.2%, NA | 0.26 |

| Parity | 1 | Guan 2016 | Any versus none | 571/2484 | RR | 1.556 [1.126 to 2.149] | 10/0/0/10 | Random | 58.7%, 0.007 | 0.116 |

| Physical activity | 1 | DiJoseph 2023 | Highest versus lowest | NA/777662 | OR | 0.65 [0.45 to 0.95] | 7/0/5/2 | Random | 93%, <0.00001 | NA |

| Place of birth | 1 | Lu 2022 | Rural versus urban | 386/1060 | OR | 1.46 [1.09 to 1.96] | 2/0/0/2 | Fixed | 0.0%, 0.716 | NA |

| PPI | 4 | Zhou 2022 | Any versus none | NA/843501 | OR | 1.69 [1.30 to 2.20] | 9/0/5/4 | Random | 94%, <0.01 | <0.001 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1 | Liang 2012 | Any versus none | 177/13576 | RR | 18.80 [10.81 to 26.79] | 12/0/12/0 | Random | 79.1%, <0.001 | NA |

| Processed meat | 4 | Yu 2022 | Highest versus lowest | 1601/1636697 | RR | 1.20 [1.02 to 1.41] | 7/0/5/2 | Fixed | 26.30%, 0.228 | 0.615 |

| Pro-inflammatory dietary pattern | 1 | Shu 2024 | Any versus none | 1106/224281 | HR | 2.21 [1.58 to 3.09] | 5/0/3/2 | Random | 25.3%, 0.253 | NA |

| Schistosome | 1 | Lu 2022 | Any versus none | 277/554 | OR | 3.17 [1.92 to 5.23] | 2/0/0/2 | Fixed | 0.0%, 0.888 | NA |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 1 | Bhagavathula 2022 | Any versus none | 22316/1051096 | RR | 0.66 [0.56 to 0.79] | 8/0/6/2 | Random | 92.9%, 0.000 | 0.506 |

| Selenium | 2 | Bjelakovic 2008 | Any versus none | 177/9798 | RR | 0.56 [0.42 to 0.76] | 4/4/0/0 | Random | 0%, 0.57 | 0.009 |

| Smoking | 8 | Abdel-Rahman 2017 | Any versus none | 9722/1718302 | OR | 1.55 [1.46 to 1.65] | 53/0/22/31 | Fixed | 49%, <0.0001 | NA |

| Statins | 19 | Rafsanjani 2024 | Any versus none | 68698/5732948 | RR | 0.56 [0.50 to 0.63] | 40/3/23/14 | Random | 90.6%, 0.000 | NA |

| Sugar-sweetened beverage | 1 | Li 2021 | Highest versus lowest | 372/477486 | RR | 2.00 [1.33 to 3.03] | 2/0/1/1 | Random | 0%, 0.526 | 0.0005 |

| Sustained virologic response in Hepatitis C | 9 | Bang 2017 | Any versus none | 2038/27497 | OR | 0.203 [0.164 to 0.251] | 35/1/34/0 | Random | 39.319%, 0.010 | 0.09 |

| Thiazolidinedione (TZD) | 3 | Arvind 2021 | Any versus none | 19466/281180 | OR | 0.92 [0.86 to 0.97] | 8/0/2/6 | Random | 43%, 0.06 | 0.46 |

| Traditional chinese medicine | 1 | Tu 2024 | Any versus none | NA/2702 | RR | 0.61 [0.51 to 0.72] | 10/10/0/0 | Fixed | 44%, 0.07 | NA |

| Vegetable | 2 | Yang 2014 | Highest versus lowest | 3338/1486584 | RR | 0.70 [0.56 to 0.87] | 17/0/9/8 | Random | 79.1%, <0.001 | 0.06 |

| White meat | 2 | Yu 2022 | Highest versus lowest | 2366/2130349 | RR | 0.76 [0.63 to 0.92] | 9/0/6/3 | Random | 68.30%, 0.001 | NA |

| Non-significant associations | ||||||||||

| Alpha-linolenic acid | 1 | Gao 2015 | Highest versus lowest | 583/91291 | RR | 0.70 [0.30 to 1.10] | 2/0/1/1 | Random | 0%, 0.999 | <0.01 |

| Antioxidant intake | 2 | Bjelakovic 2008 | Any versus none | 284/130674 | RR | 0.80 [0.56 to 1.14] | 9/9/0/0 | Random | 38.5%, 0.11 | 0.009 |

| Antiviral therapy for HBV | 7 | Thiele 2013 | Any versus none | 566/7094 | RR | 0.88 [0.73 to 1.05] | 26/4/5/17 | Random | 64.7%, 0.000 | 0.73 |

| Asian race | 1 | Lu 2022 | Asian versus white | 3521/21483 | OR | 5.36 [0.72 to 40.14] | 3/0/0/3 | Random | 98.7%, 0.000 | NA |

| BCAA | 1 | van Dijk 2023 | Any versus none | NA/NA | RR | 0.82 [0.60 to 1.12] | 6/3/3/0 | Random | NA, NA | NA |

| Blood type A | 1 | Liu 2018 | Type A versus non type A | 1960/94807 | OR | 1.27 [0.96 to 1.68] | 4/0/1/3 | Random | 68%, 0.02 | NA |

| Blood type AB | 1 | Liu 2018 | Type AB versus non type AB | 1960/94807 | OR | 1.05 [0.86 to 1.29] | 4/0/1/3 | Random | 0%, 0.64 | NA |

| Blood type B | 1 | Liu 2018 | Type B versus non type B | 1960/94807 | OR | 0.78 [0.43 to 1.42] | 4/0/1/3 | Random | 78%, 0.01 | NA |

| Carbohydrate intake | 1 | Yang 2023 | Highest versus lowest | 694/747346 | RR | 1.05 [0.84 to 1.32] | 5/0/5/0 | Fixed | 0.0%, 0.604 | 0.436 |

| Fatty liver | 4 | Han 2023 | Any versus none | 5181/79837 | HR | 1.18 [0.92 to 1.51] | 13/0/13/0 | Random | 88.9%, 0.000 | 0.249 |

| Fruit | 1 | Yang 2014 | Highest versus lowest | 2990/1051912 | RR | 0.93 [0.80 to 1.09] | 12/0/6/6 | Random | 46.8%, 0.037 | 0.7 |

| Glycemic Index | 1 | Yang 2023 | Highest versus lowest | 1157/1061595 | RR | 1.11 [0.80 to 1.53] | 6/0/5/1 | Random | 62.2%, 0.021 | 0.341 |

| High ferritin | 1 | Guo 2023 | Any versus none | 95/768 | OR | 1.31 [0.79 to 2.16] | 3/0/2/1 | Fixed | 0%, 0.71 | 0.849 |

| Hispanic race | 2 | Lu 2022 | Hispanic versus white | 3521/21483 | OR | 1.90 [0.87 to 4.17] | 3/0/0/3 | Random | 93.5%, 0.000 | NA |

| Hypertension | 5 | Seretis 2019 | Any versus none | 11634/344249 | RR | 1.30 [0.99 to 1.71] | 7/0/4/3 | Random | 93.9%, 0.000 | 0.758 |

| Marital status | 1 | Lu 2022 | Married versus unmarried | 1891/7375 | OR | 0.68 [0.36 to 1.29] | 6/0/0/6 | Random | 93.5%, 0.000 | NA |

| Meat | 3 | Yu 2022 | Highest versus lowest | 849/1032063 | RR | 1.01 [0.90 to 1.13] | 5/0/3/2 | Fixed | 15.50%, 0.316 | NA |

| Meglitinide | 1 | Arvind 2021 | Any versus none | 11310/58237 | OR | 1.19 [0.89 to 1.60] | 4/0/0/4 | Random | 72%, 0.01 | 0.44 |

| Non-aspirin NSAIDs | 3 | Liu 2022 | Any versus none | 3373/1978763 | HR | 0.95 [0.80 to 1.15] | 4/0/4/0 | Random | 56.9%, 0.073 | 0.335 |

| Nut | 1 | Wu 2015 | Highest versus lowest | 750/1463 | RR | 1.574 [0.563 to 4.401] | 4/0/0/4 | Random | 82.3%, 0.001 | NA |

| Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid | 2 | Wang 2020 | Highest versus lowest | 1071/154150 | RR | 0.83 [0.62 to 1.11] | 3/0/2/1 | Fixed | 9.2%, 0.331 | 0.334 |

| Oral contraception | 1 | Maheshwari 2007 | Any versus none | 670/5624 | OR | 1.45 [0.93 to 2.27] | 8/0/0/8 | Random | 20.4%, NA | 0.0001 |

| Pesticide | 1 | Lu 2022 | Any versus none | 3888/19817 | OR | 1.52 [0.95 to 2.42] | 5/0/0/5 | Random | 81.1%, 0.000 | NA |

| Place of residence | 1 | Lu 2022 | Rural versus urban | 3334/18913 | OR | 1.05 [0.76 to 1.44] | 3/0/0/3 | Random | 61.3%, 0.035 | NA |

| Propranolol | 1 | He 2023 | Any versus none | NA/34240 | OR | 0.94 [0.62 to 1.44] | 18/7/11/0 | Random | 89.6%, 0.000 | 0.786 |

| Red meat | 4 | Yu 2022 | Highest versus lowest | 2773/1709838 | RR | 1.04 [0.91 to 1.18] | 10/0/6/4 | Random | 50.50%, 0.033 | NA |

| Sulfonylurea | 2 | Arvind 2021 | Any versus none | 19466/281180 | OR | 1.25 [0.98 to 1.60] | 8/0/2/6 | Random | 75%, 0.0002 | 0.56 |

| TIPS | 1 | Chen 2019 | Any versus none | 129/859 | OR | 1.37 [0.96 to 1.97] | 5/1/4/0 | Random | 9%, 0.36 | NA |

MA, meta-analysis; CI, confidence interval; T, total No. of studies; R, randomized controlled trial; C, cohort studies; P, population-based case-control and/or cross-sectional studies; RR, risk ratio; OR, odds ratio; HR, hazard ratio; SMD, standardized mean difference; RRR, relative risk ratio; NA, not available; Anti-HBc, Hepatitis B core antibody; GLP-1 RAs, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; HBcrAg, Hepatitis B core-related antigen; HEV, Hepatitis E virus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HBeAg, Hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; BCAA, branched-chain amino acids; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

99% confidence interval.

Class I, class II, or class III risk factors

Virus-related

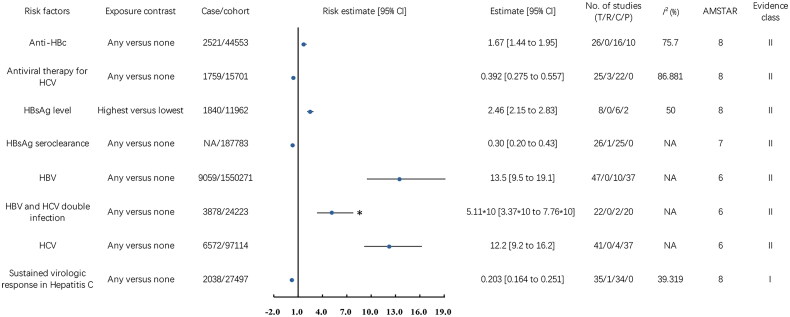

We emphasized significant findings regarding risk factors relating to HBV and HCV and their impact on HCC risk, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Associations between virus-related risk factors (Class I, Class II, and Class III) and hepatocellular carcinoma incidence. CI, confidence interval; T, total No. of studies; R, randomized controlled trials; C, cohort studies; P, population-based case-control and/or cross-sectional studies; AMSTAR, a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews; anti-HBc, Hepatitis B core antibody; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; NA, not available; *, the data was the result of the original data divided by 10.

In a 2011 meta-analysis comprising 10 cohort and 37 case-control studies involving 9,059 cases of HCC and 1,550,271 participants, HBV infection was associated with a 12.5-fold increased risk of HCC (OR 13.5, 95% CI 9.5 to 19.1, classified as Class II evidence (Class II)) [21]. In Hepatitis B patients, a 2021 meta-analysis, based on 1 RCT and 25 cohort studies (187,783 participants), showed that clearing Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) reduced HCC risk by 70% (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.20 to 0.43, Class II) [22]. In a 2019 meta-analysis of 6 cohort and 2 case-control studies, involving 1,840 HCC cases and 11,962 participants, higher HBsAg levels were associated with a 1.46-fold increase in HCC risk (OR 2.46, 95% CI 2.15 to 2.83, Class II) [23]. In HBsAg-negative individuals with chronic liver disease, a 2016 meta-analysis of 16 cohort and 10 case-control studies showed that positivity for anti-HBc antibodies was linked to a 67% higher risk of HCC (RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.44-1.95, Class II) [24].

In a 2011 meta-analysis of 41 studies involving 6,572 HCC cases and 97,114 participants, HCV infection raised the risk of HCC by 11.2 times (OR 12.2, 95% CI 9.2 to 16.2, Class II) [21]. A 2017 meta-analysis of Hepatitis C patients, based on 3 RCTs and 22 cohort studies, found that HCV antiviral therapy reduced the risk of HCC by 60.8% (OR 0.392, 95% CI 0.275 to 0.557, Class II) [25]. In a 2017 meta-analysis, including 1 RCT and 34 cohort studies with 2,038 HCC cases and 27,497 participants, a sustained virologic response (SVR) decreased HCC risk by 79.7% (OR 0.203, 95% CI 0.164 to 0.251, Class I) [25].

A 2011 meta-analysis investigated the influence of HBV and HCV co-infection, comprising 2 cohort studies and 20 case-control studies, with a total of 3,878 HCC cases and 24,223 participants. This thorough analysis revealed a significant 50.1-fold increase in HCC risk among individuals with co-infection (OR 51.1, 95% CI 33.7 to 77.6, Class II) [21].

Non-virus-related

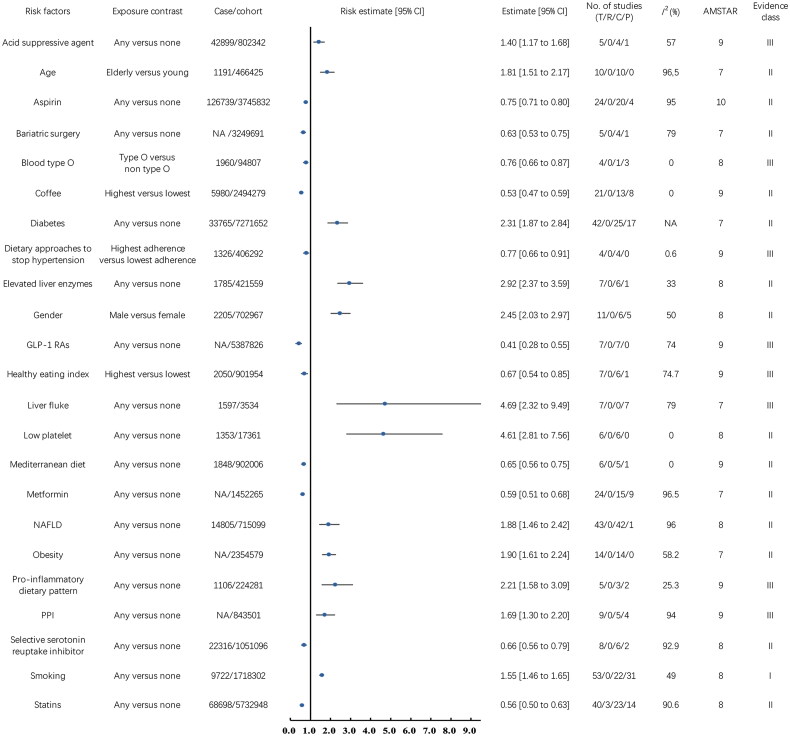

Figure 3 illustrates the relationships between non-virus-related risk factors and HCC incidence. Our analysis identified 23 risk factors falling into this category.

Figure 3.

Associations between non-virus-related risk factors (Class I, Class II, and Class III) and hepatocellular carcinoma incidence. CI, confidence interval; T, total No. of studies; R, randomized controlled trials; C, cohort studies; P, population-based case-control and/or cross-sectional studies; AMSTAR, a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews; GLP-1 RAs, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; NA, not available.

Pre-existing medical conditions and interventions are closely related to the occurrence of HCC. A 2020 meta-analysis of 14 cohort studies (2,354,579 participants) found a 90% increased risk of HCC with obesity (RR 1.90, 95% CI 1.61 to 2.24, Class II) [26]. Similarly, a 2022 meta-analysis of 42 cohort studies and 1 case-control study (14,805 HCC cases, 715,099 participants) revealed an 88% higher risk associated with NAFLD (HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.42, Class II) [27]. Further analysis in 2023 of NAFLD patients across 23 cohort studies and 7 case-control studies (726,656 participants) identified a 192% higher HCC risk with elevated liver enzymes (OR 2.92, 95% CI 2.37 to 3.59, Class II) and a 361% increased risk with low platelet counts (OR 4.61, 95% CI 2.81 to 7.56, Class II) [28]. Bariatric surgery lowers HCC risk by 37% in obese patients, as per a 2021 meta-analysis involving 4 cohort studies and 1 case-control study with 3,249,691 participants (OR 0.63, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.75, Class II) [29]. Diabetes was identified as a risk factor in a 2012 meta-analysis of 25 cohort studies and 17 case-control studies, involving 33,765 HCC cases and 7,271,652 participants, showing a 1.31-fold increase in HCC risk (RR 2.31, 95% CI 1.87 to 2.84, Class II) [30]. A 2015 meta-analysis of 7 case-control studies, including 1,597 HCC cases and 3,534 participants, found liver fluke infection associated with a 3.69-fold increased risk of HCC (OR 4.69, 95% CI 2.32 to 9.49, Class III) [31].

Lifestyle plays a crucial role in the risk of developing HCC. A 2017 meta-analysis, encompassing 22 cohort studies and 31 case-control studies with 9,722 HCC cases and 1,718,302 participants, found a 55% increase in HCC risk associated with smoking (OR 1.55, 95% CI 1.46 to 1.65, Class I) [32]. Conversely, a 2023 meta-analysis of 13 cohort studies and 8 case-control studies with 5,980 HCC cases and 2,494,279 participants found that coffee consumption reduced HCC risk by 47% (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.59, Class II) [33]. Furthermore, a 2024 meta-analysis [34] that evaluated 7 cohort studies and 6 case-control studies with 1,275,933 participants and 5,869 HCC cases revealed varied effects of diet on HCC risk: a 33% risk reduction associated with a higher healthy eating index (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.85, Class III), a 23% reduction with adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.91, Class III), and a 35% reduction linked to the Mediterranean diet (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.75, Class II). However, a pro-inflammatory dietary pattern was linked to a 1.21-fold increased risk of HCC (HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.58 to 3.09, Class III).

Past drug history is also significantly associated with the incidence of HCC. A 2022 meta-analysis including 15 cohort studies and 9 case-control studies with 1,452,265 participants revealed that metformin use decreased HCC risk by 41% (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.68, Class II) [35]. Additionally, a 2024 analysis of 7 cohort studies involving 5,387,826 diabetes patients highlighted a 59% reduction in HCC risk with the use of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) (HR 0.41, 95% CI 0.28 to 0.55, Class III) [36]. Aspirin use was associated with a 25% reduction in HCC risk, as shown in a 2023 meta-analysis of 20 cohort studies and 4 case-control studies including 126,739 HCC cases and 3,745,832 participants (HR 0.75, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.80, Class II) [37]. Statins use was linked to a 44% decreased risk of HCC, based on a 2024 meta-analysis of 3 RCTs, 23 cohort studies, and 14 case-control studies including 68,698 HCC cases and 5,732,948 participants (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.63, Class II) [38]. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were associated with a 34% reduction in HCC risk, according to a 2022 meta-analysis of 6 cohort studies and 2 case-control studies with 22,316 HCC cases and 1,051,096 participants (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.79, Class II) [39]. However, acid suppressive agents and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were found to increase the risk of HCC. A 2020 meta-analysis of 4 cohort studies and 1 case-control study with 42,899 HCC cases and 802,342 participants showed a 40% increased risk with acid suppressive agents (RR 1.40, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.68, Class III) [40], and a 2022 meta-analysis of 5 cohort studies and 4 case-control studies with 843,501 participants indicated a 69% increased risk with PPIs use (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.30 to 2.20, Class III) [41].

Demographic factors significantly affect the risk of developing HCC. A 2023 meta-analysis combining 6 cohort studies and 5 case-control studies, involving 702,967 participants and 2,205 HCC cases, found that males have a 145% higher risk of developing HCC compared to females (OR 2.45, 95% CI 2.03 to 2.97, Class II) [28]. Further, a 2024 meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies with 466,425 participants and 1,191 HCC cases highlighted an 81% increased risk associated with older age (HR 1.81, 95% CI 1.51 to 2.17, Class II) [42]. Additionally, a 2018 meta-analysis of 1 cohort study and 3 case-control studies including 1,960 HCC cases and 94,807 participants revealed that having blood type O was associated with a 24% decreased risk of HCC (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.87, Class III) [43].

Class IV risk factors

Twelve factors were found to be associated with a reduced risk of HCC. Consumption of green tea was associated with a reduced risk, with an RR of 0.80 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.95) [33]. HBeAg seroconversion in individuals with Hepatitis B indicated a considerable decrease in HCC risk, with an RR of 0.60 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.92) [44]. Engaging in physical activity was found to lower the risk of HCC, as shown by an OR of 0.65 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.95) [45]. Selenium intake was linked to a reduced risk of HCC with an RR of 0.56 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.76) [46]. The use of Thiazolidinedione (TZD) was associated with a lower risk of HCC (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.97) [47]. Fish consumption was associated with a slightly decreased risk (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.96) [48]. A diet rich in vegetables was correlated with a decreased HCC risk (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.87) [49], as was the consumption of white meat (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.92) [48]. Additionally, Carvedilol and Nadolol were effective in reducing HCC risk, with ORs of 0.62 (95% CI 0.52 to 0.74) and 0.74 (95% CI 0.64 to 0.86), respectively [50]. Traditional Chinese medicine showed a promising decrease in risk (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.72) [51]. And the presence of dyslipidemia was associated with a lower incidence of HCC (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.93) in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) patients [52].

Thirty factors were associated with a higher risk of HCC. Elevated levels of adiponectin were linked to a slightly higher risk (OR 1.066, CI 1.03 to 1.11) [53]. Exposure to aflatoxin significantly increased the risk (OR 4.75, 95% CI 2.78 to 8.11) [54]. Alcohol consumption was associated with a higher risk of HCC (OR 1.56, 99% CI 1.16 to 2.09) [55], along with the use of alpha-glucosidase inhibitors (OR 1.08, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.14) [47]. Increased aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index values, both posttreatment (HR 3.69, 95% CI 2.52 to 5.42) and pretreatment (HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.78 to 3.68), were associated with elevated risks [56]. Being of Black race (OR 2.42, 95% CI 1.10 to 5.31) [57], high levels of clusterin (SMD 1.89, 95% CI 0.76 to 3.03) [58], and dairy intake (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.91) [59] also contributed to increased risks. Illiteracy (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.89) [57], a family history of HCC (OR 3.58, 95% CI 2.53 to 5.06) [60], and working as a farmer (OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.06 to 2.08) [57] were linked with higher risks. Elevated HBV DNA levels (RR 3.06, 95% CI 1.11 to 8.44) [61], HDV and HBV double infection (OR 1.28, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.57) [62], and helicobacter pylori infection (OR 4.75, 95% CI 3.06 to 7.37) [63] were significant risk factors. Lower income levels (OR 1.74, 95% CI 1.00 to 3.03) [57], insulin use (OR 2.61, 95% CI 1.46 to 4.65) [64], labor-intensive work (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.18) [57], higher leptin levels (SMD 1.83, 95% CI 1.09 to 2.58) [53] were all linked with increased risks. Metabolic syndrome (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.72) [65], parity (RR 1.556, 95% CI 1.126 to 2.149) [66], birthplace in rural (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.96) [57], primary biliary cirrhosis (RR 18.80, 95% CI 10.81 to 26.79) [67], processed meat consumption (RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.41) [48], schistosome infection (OR 3.17, 95% CI 1.92 to 5.23) [57], and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption (RR 2.00, 95% CI 1.33 to 3.03) [68] also increased the risk of HCC. Liver fibrosis significantly increased HCC risk (RR 6.40, 95% CI 3.89 to 10.53) [28], as did Hepatitis B core-related antigen (HBcrAg) (HR 3.12, 95% CI 2.40 to 4.06) [69] and Hepatitis E virus infection (OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.26 to 3.00)[70]. Furthermore, low albumin levels were linked with a 1.11-fold higher of HCC risk (OR 2.11, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.00) [28].

Non-significant risk factors

Twenty-eight factors were found to have no significant association with the incidence of HCC. These factors include alpha-linolenic acid [71], antioxidant intake [46], and antiviral therapy for HBV [72]. Additionally, no significant correlation was observed between HCC and various demographic factors such as Asian race [57], Blood types A, AB, and B [43], as well as Hispanic race [57] and marital status [57]. Dietary factors including carbohydrate intake [73], fruit consumption [49], total meat [48], and red meat intake [48], along with specific nutritional components like omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid [74], also showed no substantial link to HCC risk. Medical conditions and treatments such as fatty liver [75], glycemic index [73], hypertension [76], ferritin [28], and the use of propranolol [50], meglitinide [47], non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [77], and sulfonylurea [47] were similarly not significantly associated with HCC. Furthermore, lifestyle and environmental factors including nut consumption [78], oral contraception usage [79], pesticide exposure [57], and place of residence [57], as well as medical procedures like transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) [80], were not found to be significantly related to the incidence of HCC.

Heterogeneity and risk of publication bias

Our analysis revealed that 66 risk factors (65.3%) exhibited significant heterogeneity, indicated by an I2 statistic >50% or a P value from Cochran’s Q test <0.1. Conversely, 30 risk factors demonstrated no significant heterogeneity. Additionally, there were 5 risk factors for which the assessment of heterogeneity was not available.

In terms of publication bias, 17 risk factors showed significant publication bias. On the other hand, 43 risk factors showed no significant publication bias. However, for 41 risk factors, the data were not available to assess the risk of publication bias.

AMSTAR and evidence classification

The median AMSTAR score across all evaluated risk factors was 8, with a range of 5 to 10 and an interquartile range of 8 to 9. Detailed information was recorded in Supplementary Table 1.

Regarding the classification of evidence strength, smoking and SVR in Hepatitis C patients were distinguished as having Class I evidence, indicating the highest level of evidence strength. Among the remaining 99 risk factors assessed, 21 were categorized as Class II, while 8 risk factors were identified as Class III. Additionally, 42 risk factors fell into Class IV, representing weak evidence. Notably, 28 risk factors were classified as non-significant.

Discussion

Principal findings and possible explanations

In this umbrella review, we thoroughly analyzed the relationship between 101 different risk factors and the incidence of HCC. Our comprehensive analysis revealed that 48 factors were associated with an increased risk of developing HCC, while 25 factors are linked to a decreased risk. Furthermore, the evidence strength for 31 of these risk factors was categorized into classes I, II, and III. Notably, 8 of these risk factors were related to viral infections, underscoring the significant role of viral etiologies in HCC development. The remaining 23 risk factors spanned a broad range of categories, including lifestyle, past drug history, pre-existing medical conditions or interventions, etc.

HBV infection significantly increases the incidence of HCC. Chronic Hepatitis B (CHB) leads to repeated cycles of liver damage and regeneration, a process that promotes tumorigenesis [81]. The lack of proofreading activity in HBV’s reverse transcriptase results in frequent gene mutations, more so than in other DNA viruses [82]. Various mutations, particularly those accumulated over long-term infection, can predict the onset of HBV-associated HCC [83]. Further complicating the virus-host interaction is the immune evasion mechanism. Long-term accumulation of epitope mutations in HBcAg and HBeAg under immune pressure from cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) diminishes the virus-specific CTL response, allowing the virus to evade immune surveillance [84]. Viral DNA integration into the host genome is a critical molecular mechanism in the occurrence of HCC, with about 85% to 90% of tumor cells from HCC patients showing evidence of HBV DNA integration [81]. This integration can lead to significant copy number variations near the integration sites, causing genomic instability in hepatic cells and inducing mutations, chromosomal deletions, and gene rearrangements [85–87].

HBsAg, primarily considered a marker of HBV infection [88], is translated from mRNA using the transcriptionally active covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) as a template, reflecting the number of infected hepatocytes [89]. High HBsAg level is generally considered to be associated with elevated HBV DNA level, indicative of increased viral replication and higher HCC risk [90,91]. Clearance of HBsAg is typically associated with favorable clinical outcomes, indicating disease remission [92]. Nucleos(t)ide analog (NA) treatment, which is the main antiviral regimen for HBV infection, primarily affects the reverse transcription of pregenomic RNA but does not impact cccDNA and subgenomic RNA linked to HBsAg levels [93]. Consequently, NA therapy seldom results in HBsAg clearance, and achieving HBsAg loss may take several decades with current treatment protocols. That may explain why antiviral therapy for HBV does not significantly reduce the incidence of HCC. The presence of anti-HBc in HBsAg-negative subjects, suggesting resolved HBV infection, has been used as a surrogate marker of occult HBV infection [24]. HBV DNA is detectable in a significant portion of such cases, indicating prolonged exposure to occult HBV replication that may favor HCC onset [94].

HCV is another viral etiology known to cause HCC. Similar to HBV, HCV can evade the host’s immune clearance, leading to persistent chronic hepatitis, fibrosis, and ongoing hepatocyte damage and repair [95]. This cycle increases the frequency of genetic mutations in liver cells, thereby elevating the risk of HCC [96]. Unlike HBV, HCV is a single-stranded RNA virus that does not integrate directly into the host cell DNA. However, HCV can still induce carcinogenesis through epigenetic remodeling of host DNA. HCV viral proteins, including the core protein and non-structural proteins, can lead to abnormal expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes [97]. Additionally, HCV viral proteins contribute to the development of steatosis and insulin resistance (IR), exacerbating inflammation and oxidative stress, which further predisposes to carcinogenesis [98,99]. In contrast to HBV, HCV infection is curable, particularly with the advent of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), which have achieved viral clearance rates of over 95% [100]. Achieving an SVR is considered a cure for Hepatitis C. Therefore, antiviral therapy and achieving SVR can significantly reduce the incidence of HCC in patients with HCV.

The co-infection of hepatitis viruses notably escalates the risk of HCC, as these viruses exhibit distinct carcinogenic mechanisms that, when combined in hepatocytes, can influence various stages of cancer development [101,102]. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests a reciprocal interference between viruses, affecting each other’s replication [21]. Similarly, the concurrent presence of liver fluke and HBV intensifies HCC risk by impairing liver functionality and encouraging HBV spread [103]. Liver flukes cause epithelial damage and inflammation, progressing to liver conditions conducive to cancer [31]. Additionally, the immune response to liver fluke infection, characterized by the activation of ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways, is implicated in promoting tumorigenesis [104].

Apart from infectious liver diseases, numerous pre-existing medical conditions and interventions are closely linked to the incidence of HCC. Conditions such as obesity, NAFLD, and diabetes significantly elevate the risk of developing HCC by promoting oxidative stress, leading to DNA damage and gene mutations [30,105,106]. These risk factors also trigger inflammation, resulting in liver cell damage, fibrosis, and cirrhosis [107–109]. Furthermore, they are associated with alterations in the gut microbiota composition, increasing intestinal permeability and the translocation of bacterial components, closely tied to HCC development [110]. For instance, deoxycholic acid, produced by the gram-positive bacteria Clostridium, generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause DNA damage [111]. The interplay of these risk factors compounds the effect, accelerating HCC development. With the accumulation of fat in liver cells, obesity acts as an independent risk factor for NAFLD [112]. IR, a main cause of Type 2 diabetes, could stem from excessive adiposity and chronic inflammation [113]. IR also promotes the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-a and IL-6 [114]. This creates a feedback loop of IR and inflammation, exacerbating NAFLD under lipotoxic conditions. IR also increases levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), encouraging cellular proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis, which can lead to cancer [115]. Bariatric surgery emerges as an effective intervention for severely obese patients with NAFLD and diabetes, outperforming other weight loss methods in achieving significant weight reduction [116]. It has been shown to resolve hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in most cases, thereby reducing the HCC risk in patients with obesity and diabetes [117].

The occurrence of HCC is closely linked to lifestyle factors. Smoking significantly increases the likelihood of developing HCC. Tobacco smoke contains various carcinogens like tar and vinyl chloride, which cause damage to liver cell DNA and induce gene mutations, leading to cancer [10]. Additionally, toxic substances in smoking products activate pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, triggering the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC) [118,119]. This activation leads to the production of extracellular matrix components and fibrotic tissue, contributing to liver cirrhosis and, subsequently, HCC. The increased oxidative stress caused by smoking not only results in DNA damage but also enhances HSC activation and fibrosis. Smoking also has a synergistic effect with chronic viral hepatitis infections, such as HBV and HCV, intensifying the risk of HCC. A meta-analysis has demonstrated that the interaction between HBV and smoking goes beyond simple addition, while the interaction between HCV and smoking exceeds mere multiplication [120]. Smoking impairs immune function, reducing the clearance of hepatitis viruses and increasing viral replication in the body, thus heightening the risk of HCC development [121].

Coffee significantly reduces the incidence of HCC due to its rich content of caffeine, chlorogenic acid, and diterpenes [33]. These compounds exhibit antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects, neutralizing harmful free radicals, reducing oxidative stress, and decreasing DNA mutations in liver cells that can initiate cancer [122]. Furthermore, coffee promotes improved metabolic functions, such as enhanced glucose regulation and insulin sensitivity, lowering diabetes risk—a known risk factor for HCC [123]. It also improves lipid metabolism, reducing the occurrence of NAFLD, another HCC risk factor. Regular consumption of coffee is associated with reduced liver enzyme levels, such as gamma-glutamyltransferase and alanine aminotransferase, indicators of liver health and disease [124]. Additionally, coffee intake may slow the progression of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, reduce HCC cell proliferation, inhibit hepatitis virus activity, counteract aflatoxin B1-induced genotoxicity, and positively influence gut microbiota, contributing to overall liver health and reduced liver damage [125–128].

Numerous medications, including several antidiabetic drugs, have proven effective in lowering the incidence of HCC. Furthermore, the benefits of these drugs extend beyond merely reducing cancer rates; they also significantly enhance the prognosis for patients diagnosed with HCC [129]. Metformin, for instance, targets IR and hyperinsulinemia, which both are acknowledged risk factors for HCC [130]. By enhancing the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway while inhibiting the mTOR pathway, it also curtails protein synthesis, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis [35]. Metformin has alson been shown to dose-dependently reduce the expression of Livin, a protein that plays a role in both cell proliferation and survival [129]. GLP-1 RAs enhance glucose regulation via their incretin properties. Therapies based on incretins have demonstrated effectiveness in halting crucial processes involved in liver carcinogenesis. These include diminishing the activity of transforming growth factor alpha and hepatocyte growth factor, lowering oxidative stress in the liver, and managing systemic inflammation [36, 131]. Statins, known for their cholesterol-lowering effects, also deter cancer cell proliferation by halting the conversion of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) to mevalonate and diminishing isoprene production [132]. They further alleviate liver inflammation by reducing IL-6 and TNF-α expression, curtailing metalloproteinase activity, and lessening ROS production [133]. Additionally, statins augment the antiviral efficacy of interferon (IFN) and ribavirin treatments against HCV [134]. Platelets directly engage with white blood cells and endothelial cells, secreting numerous substances such as thromboxane A2, factors that induce angiogenesis, and growth factors, which encourage the growth and spread of cancer cells [135]. Additionally, platelets significantly contribute to the development of liver disease associated with HBV by facilitating the gathering of virus-specific CTLs within the liver, leading to increased liver inflammation [136]. Aspirin, an anti-platelet medication, reduces HCC risk by interfering with platelet functions. It also hampers Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) activity, an enzyme from inflammatory cells that aids angiogenesis, thereby inhibiting tumor growth [137]. Aspirin has shown potential in blocking HCV entry and diminishing HCV RNA and protein expression [138]. SSRIs counteract the negative impacts of serotonin on liver inflammation, fibrosis, and HCC cell proliferation by inhibiting its reuptake, thus reducing HCC risk [139,140]. Furthermore, SSRIs provide benefits for patients with major depression and alcohol use disorder, mitigating HCC risks associated with alcohol and exhibiting antiviral properties that enhance IFN-mediated effects [141,142]. However, acid-suppressive agents, particularly PPIs, have been associated with an elevated risk of developing HCC. Although a definitive cause has yet to be identified, several potential mechanisms have been proposed. Chronic hypochlorhydria can lead to hypergastrinemia, and research indicates that HCC cells may express gastrin receptors, which could contribute to tumor growth [143,144]. Furthermore, the reduction in gastric acid can induce alterations in the gut microbiota composition. Such changes could heighten the risk of infections, leading to toxicity, inflammation, and DNA damage in liver cells, potentially increasing the susceptibility to HCC [145,146]. However, caution should be exercised regarding this finding due to the significant heterogeneity observed in the meta-analysis. Another meta-analysis, which adjusted data for comorbidities and concurrent medications, found the association between PPIs and HCC to be insignificant [147]. Furthermore, some studies have even indicated potential synergistic effects of PPIs on chemotherapeutic agents for tumors, suggesting a complex interaction that could influence the risk of HCC under certain conditions [148].

Interestingly, a link between ABO blood type and the incidence of HCC has been observed. Individuals with blood type O have a notably lower risk of developing HCC compared to those with other blood types. While the specific mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear, some studies suggest that individuals with blood type O are less likely to contract hepatitis B or C, which are major risk factors for HCC [43,149]. Additionally, there appears to be a negative correlation between blood type O and the severity of liver fibrosis [150]. Research also indicates that the A antigen may possess immune escape and anti-apoptotic properties that facilitate the proliferation and survival of HCC cells. Since individuals with blood type O lack the A antigen, they may have a better defense against the development of HCC [151].

Strengths and limitations

This umbrella review marks the first extensive summary of risk factors for HCC, drawing from prior meta-analyses of observational studies and RCTs. Given HCC’s poor prognosis and high mortality rate, identifying its risk factors and implementing preventive measures against HCC is of paramount importance. This objective is the main focus of our study. Our research utilized systematic methodologies, incorporating a comprehensive search across four scientific databases and independent review and data extraction by two researchers. When data allowed, we recalculated RR, OR, HR, WMD, or SMD with a 95% CI using either random or fixed effects models, alongside assessing heterogeneity and publication bias for every meta-analysis included. The quality of these meta-analyses was evaluated using the AMSTAR tool, and the evidence’s strength was determined based on the evidence categories criteria.

Our study acknowledges multiple limitations that are crucial for interpreting our results. Significant heterogeneity among the included studies arises from diverse study designs, participant populations, and measurement methods for variables like coffee consumption and smoking. This variety in methodologies might impact the uniformity of our findings, suggesting a need for future research that utilizes multicentric, large-scale designs with standardized measurement criteria to address these discrepancies. Additionally, the meta-analyses we reviewed often exhibit publication bias, which may distort the results, highlighting a tendency to publish studies with more significant findings. When studies predominantly originate from certain regions, such as Asia or Europe, it can lead to geographic bias. This bias occurs because the findings may not be applicable to populations from other regions due to genetic, environmental, dietary, and lifestyle differences that can influence health outcomes. Moreover, small sample sizes within these studies might further contribute to publication bias. The dependence on secondary data from these meta-analyses introduces selection bias, as we rely on the original studies’ selection criteria and data quality, limiting our ability to control data integrity. There may be instances of data omission or analytical errors within these datasets that could affect our analytical conclusions.

A considerable number of analyzed risk factors were categorized as weak evidence (Class IV) or non-significant, often due to small sample sizes or insufficient P values. This highlights the need for more robust study designs and larger sample sizes to fortify the evidence base. We also recognize the exclusion of critical risk factors such as cirrhosis, owing to the lack of specific meta-analyses addressing these factors, which creates gaps in our analysis and may limit the scope of our risk factor assessment. Lastly, inconsistencies in study scoring and the inability to consistently reanalyze all data due to potential data loss pose challenges to the robustness and reliability of our findings. These issues underline the importance of enhancing methodological consistency and data verification in future studies.

Conclusions and recommendations

This umbrella review pinpointed 101 unique risk factors for HCC, highlighting 31 factors with class I, II, or III evidence and 42 with class IV evidence. Infection with hepatitis viruses, particularly HBV and HCV, remains a major risk factor. Vaccination against hepatitis B and antiviral treatment for hepatitis C are effective preventive measures. Additionally, lifestyle factors like smoking and alcohol consumption significantly increase the risk of developing HCC, making cessation crucial for prevention. Certain medications, such as aspirin, statins, GLP-1 RAs, and metformin, have shown potential in reducing the incidence of HCC. More high-quality prospective studies are necessary to substantiate these findings.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Author contributions

JW and KQ, who share first authorship, made equivalent contributions to the research. JW and KQ conceptualized and designed the study. JW, KQ, SZ, YG, DW, and KJ conducted the selection of studies, extraction of data, analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. HW played a supervisory role throughout the project and was involved in the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors have given their approval for the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1598–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel A, Meyer T, Sapisochin G, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2022;400(10360):1345–1362. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petrick JL, Florio AA, Znaor A, et al. International trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, 1978-2012. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(2):317–330. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, et al. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123–133. doi: 10.1002/hep.29466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sachar Y, Brahmania M, Dhanasekaran R, et al. Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with Hepatitis B. Viruses. 2021;13(7):1318. doi: 10.3390/v13071318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao J-H. Hepatitis B vaccination and prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;29(6):907–917. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galati G, Muley M, Viganò M, et al. Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: literature review and risk analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(7):603–610. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2019.1617272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelber-Sagi S, Noureddin M, Shibolet O.. Lifestyle and hepatocellular carcinoma what is the evidence and prevention recommendations. Cancers (Basel). 2021;14(1):103. doi: 10.3390/cancers14010103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez M, González-Diéguez ML, Varela M, et al. Impact of alcohol abstinence on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcohol-related liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116(12):2390–2398. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simon TG, Chan AT.. Lifestyle and environmental approaches for the primary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2020;24(4):549–576. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zunica ERM, Heintz EC, Axelrod CL, et al. Obesity management in the primary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(16):4051. doi: 10.3390/cancers14164051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singal AG, Kanwal F, Llovet JM.. Global trends in hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology: implications for screening, prevention and therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(12):864–884. doi: 10.1038/s41571-023-00825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aromataris E, Fernandez R, Godfrey CM, et al. Summarizing systematic reviews: methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):132–140. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papatheodorou S. Umbrella reviews: what they are and why we need them. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(6):543–546. doi: 10.1007/s10654-019-00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Y, Chen Z, Chen B, et al. Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review. BMJ. 2023;381:e071609. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-071609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ioannidis JPA. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ. 2009;181(8):488–493. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irwig L, Macaskill P, Berry G, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ. 1998;316(7129):470–471. 470; author reply. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7129.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho LY, Yang JJ, Ko K-P, et al. Coinfection of hepatitis B and C viruses and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(1):176–184. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson RT, Choi HSJ, Lenz O, et al. Association between seroclearance of Hepatitis B surface antigen and long-term clinical outcomes of patients with chronic Hepatitis B virus infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(3):463–472. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thi Vo T, Poovorawan K, Charoen P, et al. Association between Hepatitis B surface antigen levels and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic Hepatitis B infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20(8):2239–2246. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.8.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coppola N, Onorato L, Sagnelli C, et al. Association between anti-HBc positivity and hepatocellular carcinoma in HBsAg-negative subjects with chronic liver disease: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(30):e4311. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bang CS, Song IH.. Impact of antiviral therapy on hepatocellular carcinoma and mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17(1):46. doi: 10.1186/s12876-017-0606-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang C, Lu Y, Xia H, et al. Excess body weight and the risk of liver cancer: systematic review and a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutr Cancer. 2020;72(7):1085–1097. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2019.1664602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrelli F, Manara M, Colombo S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neoplasia. 2022;30:100809. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2022.100809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo WP, Zhang HY, Liu LX.. Risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023;27(24):11890–11903. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202312_34788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramai D, Singh J, Lester J, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: bariatric surgery reduces the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;53(9):977–984. doi: 10.1111/apt.16335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang P, Kang DH, Cao W, et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28(2):109–122. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia J, Jiang SC, Peng HJ.. Association between liver fluke infection and hepatobiliary pathological changes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132673. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Rahman O, Helbling D, Schöb O, et al. Cigarette smoking as a risk factor for the development of and mortality from hepatocellular carcinoma: an updated systematic review of 81 epidemiological studies. J Evid Based Med. 2017;10(4):245–254. doi: 10.1111/jebm.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, Liang D, Li J, et al. Coffee, green tea intake, and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2023;75(5):1295–1308. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2023.2178949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shu W, Liu L, Jiang J, et al. Dietary patterns and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2024;21(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s12986-024-00822-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li QM, Xu HR, Sui CJ, et al. Impact of metformin use on risk and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetes mellitus. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2022;46(2):101781. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2021.101781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shabil M, Khatib MN, Ballal S, et al. Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Glucagon-like Peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment in patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2024;24(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12902-024-01775-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma S, Qu G, Sun C, et al. Does aspirin reduce the incidence, recurrence, and mortality of hepatocellular carcinoma? A GRADE-assessed systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023;79(1):39–61. doi: 10.1007/s00228-022-03414-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashemi Rafsanjani MR, Rahimi R, Heidari-Soureshjani S, et al. Statin use and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a comprehensive meta. Analysis and systematic review. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2024. doi: 10.2174/0115748928282686231221070441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhagavathula AS, Woolf B, Rahmani J, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and dose-response analysis of cohort studies with one million participants. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;78(7):1199–1200. doi: 10.1007/s00228-022-03309-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song HJ, Jeon N, Squires P.. The association between acid-suppressive agent use and the risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(10):1437–1456. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-02927-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou WC, Chen XL, Fan QG, et al. Using proton pump inhibitors increases the risk of hepato-biliary-pancreatic cancer. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:979215. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.979215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin H, Yan Z, Zhao F.. Risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Technol Health Care. 2024;32(6):3943–3954. doi: 10.3233/thc-231331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu F, Li C, Zhu J, et al. ABO blood type and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;12(9):927–933. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2018.1500174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou TC, Lai X, Feng MH, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatitis e antigen seroconversion. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25(10):1172–1179. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiJoseph K, Thorp A, Harrington A, et al. Physical activity and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2023;68(3):1051–1059. doi: 10.1007/s10620-022-07601-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, et al. Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastrointestinal cancers. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2008. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004183.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arvind A, Memel ZN, Philpotts LL, et al. Thiazolidinediones, alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, meglitinides, sulfonylureas, and hepatocellular carcinoma risk: a meta-analysis. Metabolism. 2021;120(pagination):154780. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2021.154780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu J, Liu Z, Liang D, et al. Meat intake and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutr Cancer. 2022;74(9):3340–3350. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2022.2077386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang Y, Zhang D, Feng N, et al. Increased intake of vegetables, but not fruit, reduces risk for hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(5):1031–1042. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He X, Zhao Z, Jiang X, et al. Non-selective beta-blockers and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1216059. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1216059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tu A, Zhu X, Dastjerdi PZ, et al. Evaluate the clinical efficacy of traditional Chinese Medicine as the neoadjuvant treatment in reducing the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e24437. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e24437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao S, Liu Y, Fu X, et al. Modifiable risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2024;137(11):1072–1081.e32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang LL, Yuan QH, Li M, et al. The association of leptin and adiponectin with hepatocellular carcinoma risk and prognosis: a combination of traditional, survival, and dose-response meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):1167. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-07651-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Chang CC, Marsh GM, et al. Population attributable risk of aflatoxin-related liver cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(14):2125–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li Y, Yang HA, Cao J.. Association between alcohol consumption and cancers in the Chinese population-A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang C, Wu J, Xu J, et al. Association between aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index and hepatocellular carcinoma risk in patients with chronic hepatitis: a meta-analysis of cohort study. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:2046825. doi: 10.1155/2019/2046825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu W, Zheng F, Li Z, et al. Association between environmental and socioeconomic risk factors and hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:741490. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.741490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beheshti Namdar A, Kabiri M, Mosanan Mozaffari H, et al. Circulating clusterin levels and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Control. 2022;29:10732748211038437. doi: 10.1177/10732748211038437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou J, Yang Y, Chen Z, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: dairy consumption and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Journal of Public Health (Germany). 2017;25(6):591–599. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyu X, Liu K, Chen Y, et al. Analysis of risk factors associated with the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic HBV-infected Chinese: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(6):604. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13060604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen X, Wu F, Liu Y, et al. The contribution of serum hepatitis B virus load in the carcinogenesis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from two meta-analyses. Oncotarget. 2016;7(31):49299–49309. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alfaiate D, Clément S, Gomes D, et al. Chronic hepatitis D and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hepatol. 2020;73(3):533–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madala S, MacDougall K, Surapaneni BK, et al. Coinfection of helicobacter pylori and hepatitis c virus in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13(12):530–540. doi: 10.14740/jocmr4637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh S, Singh PP, Singh AG, et al. Anti-diabetic medications and the risk of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):881–891; quiz 892. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen YX, Li XF, Wu S, et al. Metabolic syndrome and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:6277–6285. doi: 10.2147/ott.S154848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guan ZF, Zhu HC, Xia XC, et al. Parity is a risk factor for hepatobiliary neoplasm: a meta-analysis of 16 studies. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9:952–964. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liang Y, Yang ZX, Zhong RQ.. Primary biliary cirrhosis and cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2012;56(4):1409–1417. doi: 10.1002/hep.25788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li YT, Guo LLZ, He KY, et al. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice and human cancer: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. J Cancer. 2021;12(10):3077–3088. doi: 10.7150/jca.51322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]