Abstract

Background

The evolving healthcare landscape emphasizes the need for health systems to adapt to growing complexities, with new models of care enabling healthcare providers to optimize their scope of practice and coordination of care. Despite increasing interest in advanced practice, confusion persists regarding the roles and scopes of practice of healthcare providers, exacerbated by variations in regulations and titles. We sought to clarify the differences between specialized healthcare professionals, practitioners, and clinical specialists; to describe their roles; and to propose initiatives aimed at supporting the implementation of advanced practice within a university hospital.

Methods

An action research design was conducted in a Swiss university hospital by the deputy healthcare director, five clinical specialists, one nurse practitioner, one nurse specialist, and six managers. A multimethod approach was used to generate data, which included a literature review, meeting minutes, unstructured interviews, and a questionnaire assessing healthcare providers’ perceptions about the clinical specialist role. Semi-structured interviews and a group interview with nursing leaders from Swiss hospitals were conducted to understand their use of clinical roles at the advanced level. Unstructured interviews were reduced and organized into categories. Survey data were analyzed with descriptive statistics, and an inductive content analysis method was used for semi-structured interviews and the group interview.

Results

Managers and healthcare providers shared a vision of clinical specialists’ activities but emphasized the lack of clarity surrounding these functions. Role clarity was emphasized as crucial for sustainability of advanced practice. A model that defined healthcare specialist, practitioner, and clinical specialist roles was developed. It included title standardization, use of an implementation strategy, creation of a tool to facilitate profile selection, and implementation of a communication plan. Further initiatives aimed to enhance training funding, establish regulations, and optimize advanced practice implementation and governance within the hospital.

Conclusions

The study results encourage clarification of clinical roles to facilitate their implementation and optimize resources. They also suggest initiatives to support advanced practice implementation, such as a communication plan and an implementation strategy, reflection on the current governance model, and integration of advanced practice providers. Ongoing efforts involve collaboration with academics, managers, and discussions at the political level.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12913-025-12268-w.

Keywords: Advanced practice, Role clarification, Action research

Patient care underscores the pressure faced by health systems worldwide to adapt to evolving needs. The development of new care models is a key element in this transformation. For nurses and allied health professionals, there is a need to capitalize on their full value and scope of practice to maintain patient safety and quality of care and to avoid the waste of underutilized competences [1]. However, different roles are associated with different competence levels and different scopes of practice.

The lack of clarity between specialized and advanced roles has been described [2–6] and identified as a major barrier to the effective use of skills and the implementation of a full scope of practice [3, 4, 6]. Efficient use of health professionals is essential in the context of shortage and scarcity of resources. The European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN) distinguishes between three nursing categories: general care nurse, specialist nurse, and advanced practice nurse (APN) [7]. Each category has defined competences, qualifications, and activities. The aim of EFN is to harmonize these categories across European countries [7]. The role distinction has been expanded to other healthcare professions, such as physiotherapists, midwives, occupational therapists, radiology technicians, and dieticians in several European countries [8–10].

Specialists are defined as general care providers with a non-master of sciences postgraduate education in a specialty [2, 5, 11, 12]. Education may include clinical courses, practice experience, and on-the job training. Some nursing specialties are well recognized, such as critical care nursing, and certification is available in several countries. In some specialties, certifications are required for care to be reimbursed by health insurance, as is the case in Switzerland for stomatherapy and diabetes nursing care.

Advanced practice providers are professionals who have acquired further knowledge and expertise at the Master of Sciences level [2, 13–16]. They have expanded skill in clinical judgment and large autonomy in responding to patients’ care needs. In addition, they can judiciously use and adapt evidence to the patient’s context [2, 13–16]. Both advanced practice roles – clinical specialist and practitioner – are currently present in Swiss healthcare facilities [17, 18]. However, advance practice is not yet regulated on a federal level. To date, each state, called a canton in Switzerland, has significant autonomy in regulating healthcare practices, leading to large variations in competences and scopes of practice among advanced practice roles [17, 18]. In some facilities, the two advanced practice roles are not differentiated, and only the term advanced practitioner is used [17]. Scope of practice also varies substantially, with some cantons allowing for a broader range of clinical activities while others have more restrictive regulations.

For decades in Switzerland, nurses and professional nursing organizations have made efforts to promote the interests of the profession, improve working conditions, and enhance the quality of care. In 2021, the acceptance of the nursing initiative for strong nursing care paved the way for federal discussions on regulating the roles of advanced practice nurses (APNs) at the national level [19]. In 2023, the Swiss Federal Council recognized the need to regulate advanced practice and its financing through insurance, but only for nurses. Despite this, this recognition represents a significant step forward for advanced practice in Switzerland.

To date, in the Canton of Geneva, advanced practice has mainly developed around clinical specialist roles, particularly for nurses. However, only a limited number of professionals meet the international and national education requirements of a Master of Sciences degree.

Healthcare institutions are eager to introduce nurse practitioners and have begun implementing these roles within their organizational structures. However, the difference in the scope of practice of practitioners, clinical specialists, and specialized providers remains unclear [2, 5, 14].

The combination of changes in health legislation, evolving healthcare landscape, and need to clarify advanced practice has led the nursing and allied healthcare professionals’ management of the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) to set up a working group with the following objectives:

To describe the roles of specialized healthcare professionals, clinical specialists, and practitioners.

To clarify the differences between these roles.

To propose initiatives aiming to support the implementation of advanced practice within our organization.

Methods

Study setting

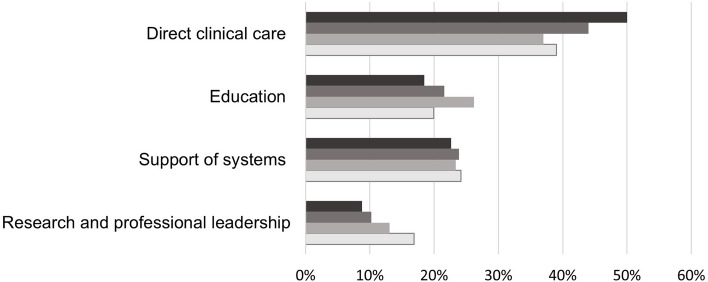

The project was conducted at HUG, a university hospital comprising eight public hospitals and two clinics. It employs about 4500 as non-medical healthcare professionals, among whom 1500 are considered specialist healthcare professionals and providing specialized direct patient care. In terms of clinical specialists, 42 individuals have this role, with 15 having completed a Master of Sciences: 10 in nursing sciences, 1 in health sciences with a physiotherapy option, 1 in midwifery sciences, 1 in education sciences, and 2 in public health. Most clinical specialists are attached to the Nursing and Allied Healthcare Professionals Directorate and have a transversal role, enabling them to intervene across various services and departments within their domain of expertise. Clinical specialist activities include direct and indirect patient care, care development, and education. The distribution of activities differs among clinical specialists, and research remains a field that is least explored by these roles. At the time of the study, there was no advanced practitioner providers employed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Clinical specialist domains of activities at HUG. Legend -

2020

2020

2021

2021

2022

2022

2023

2023

Study design

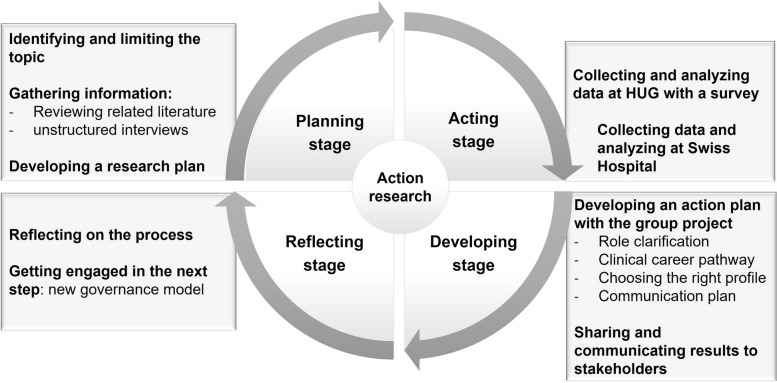

An action research design was chosen for this study because of its collaborative and participatory nature [20]. The action research process by Mertler (2017) [21] was used to operationalize this project. Mertler defined four main stages to guide action research: planning, acting, developing, and reflecting (Fig. 2). The planning stage has already been detailed in the introduction and the methodology section. The action stage is outlined in the data collection methods and the synthesis of results derived from the data. The development stage is presented as the results of this action research, showcasing the action plan based on the study’s findings. Finally, the reflection stage is discussed in the discussion section of this paper.

Fig. 2.

Step-by-step process of action research in HUG based on the model of Mertler (2017) [20]

Working group participants

The project was conducted by the deputy healthcare director of HUG. A working group was formed with all five clinical specialists, six managers, one nurse practitioner, and one nurse specialist. The participants had all responded to a call from the Director of Nursing and Allied Health to study and work on the theme. Several professions were represented, including nursing, midwifery, nutrition, physiotherapy, and radiologic technology. Supplementary Table 2 (Additional file 1) provides an overview of the working group participants, including their professional roles, educational backgrounds, and areas of expertise. After an initial session that brought together all participants, the group was divided into two subgroups. The first subgroup worked on the description of the links between management and clinical roles. The second subgroup worked on defining initiatives that aimed to support the implementation of advanced practice within the organization. Both groups worked on clarifying the differences between specialized healthcare professionals, clinical specialists, and nurse practitioners. All groups were inspired by the action research methodology with a circular and iterative process of planning, acting, developing, and reflecting stages [21].

Data gathering

The project took place between September 2021 and March 2023. The group chose a multimethod approach to collect evidence related to this study. The evidence comprised a blend of insights drawn from a literature review, clinical practice, and local and external contexts. Surveys, a group interview, and unstructured and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data. Multiple group and subgroup meetings played a role in generating proposals and advancing developments.

Unstructured interviews

To gather information, the first group conducted unstructured interviews with clinical specialists and partners within the organization who collaborate with clinical specialists. Five clinical specialists, six head nurses, one head physiotherapist, and two head physicians from HUG were interviewed. Professionals were asked about how clinical specialists collaborate with healthcare facilities and services, as well as the need for connections between clinical specialists and services. Notes were taken during the interviews by two members of the first group and subsequently compared within hours to ensure completeness and accuracy.

Surveys

The information collected through the unstructured interviews led the first group to create an electronic questionnaire specifically for this study, using FORMS. Supplementary Table 3 (Additional file 2) presents the questionnaire developed to assess healthcare providers’ perceptions about the clinical specialist role.

The survey aimed to learn participant perceptions about the clinical specialist role within the organization. To assess participants’ perceptions of clinical specialist activities, participants were invited to respond to 12 Likert-scale questions ranging from 1 (Totally agree) to 5 (Totally disagree). The questions were as follows: Clinical specialist interventions should occur at the level of: patient consultation? team consultation? coaching, guidance? analysis of professional practice? education? service project? institutional project? care development? service meeting? department meeting? research activities? commission meetings?

The survey was addressed to 382 persons: healthcare managers, clinical specialists, and nonmedical health professionals with a master’s or doctoral degree working in the institution.

Semi-structured interviews and a group interview

With the aim of understanding advanced practice roles and organization in Swiss hospitals, semi-structured interviews and a group interview were conducted by the head nurse of clinical specialists, the deputy nursing director, and the clinical nurse specialist in acute care. Participants are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Semi-structured interviews and group interview participants

| Participant | Type of organization | |

|---|---|---|

| Individual semi-structured interviews | 1 Care director | Swiss French ophthalmic hospital |

| 1 Deputy director | Swiss French university hospital | |

| 1 Deputy director | Swiss German university hospital | |

| 1 Head physiotherapist | Swiss French university hospital | |

| 1 Head physiotherapist | Swiss French hospital | |

| Focus group interview |

1 Nursing director 1 Deputy nursing director 1 Clinical nursing specialist |

Swiss German university hospital |

The semi-structured interviews and the group interview were conducted based the same interview guide (see Supplementary Table 4 in Additional file 3). The interviews, lasting approximately 45 minutes, were conducted by videoconference by the first author (PTM), and recorded with the participants’ consent. A written summary highlighting the key elements of each interview was subsequently provided to the participants for their review and approval. To further analyze the external context and to gain insights from multiple experts, a group interview was conducted. For this group interview, notes were taken during the interview by three of the authors (PTM, SK, MJR) and compared within hours to ensure completeness and accuracy.

Data analysis

The unstructured interviews were reduced and organized into categories that were inductively generated [22] by two members of the first subgroup and presented to all group members for discussion.

Survey data were analyzed by using descriptive statistics and processed in an Excel file while ensuring participant confidentiality. Data from managers and clinicians were analyzed separately and subsequently combined.

For the semi-structured interviews, verbatim transcriptions were made. From the recorded interviews transcribed verbatim, we used an inductive content analysis method for data processing, extracting categories related to the described phenomenon which was carried out by the group members with an academic background (PTM, ADA) [23, 24]. The inductive analysis process encompassed three stages: data selection for analysis, development of a categorization matrix, and data coding [23, 24]. Data were organized in an Excel file to display the categories. The findings were presented to the first group to verify the consistency of the coding and results. For the group interview, the notes were analyzed by PTM, SK and MJR following the same process as described above.

Ethical considerations

As part of the process to enhance healthcare quality, the study did not require approval from the Research Ethics Committee, as it fell outside the scope of Swiss law on human research. Prior to the interviews, we obtained consent from the participants to answer the questions, and the questionnaires were administered anonymously. Participants in both the survey and the interviews granted consent for their data to be used. To avoid any feeling of pressure on the participants, the Deputy Nursing Director leading the project was not directly involved in the internal data collection. This study followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results from the data collection

Unstructured interviews

Two main categories emerged from the unstructured interviews conducted with HUG professionals: the “need to clarify clinical specialists’ activities” and the “need for role clarification.” According to the participants, clinical specialists’ activities included patient and team consultation, teleconsultation, and collaboration with physicians, educators, and managers. Role clarification and visibility were mentioned as critical elements for the sustainability of this role. Participants emphasized the importance of making the missions, roles, and added value of clinical specialists known and visible.

Survey

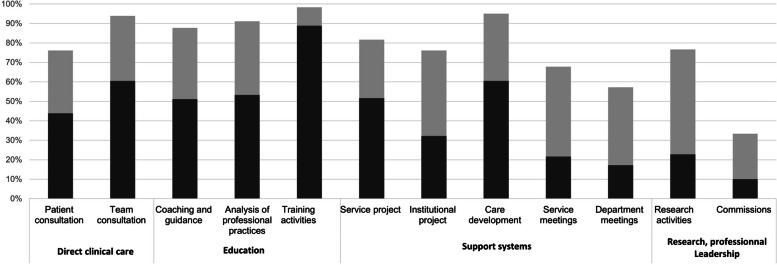

The survey was sent to 382 participants and 180 responded (47.1%). Of the respondents, 132 were managers (73.3%), 33 (18.3%) were clinical specialists, and 15 (8.3%) were healthcare providers with a master’s degree. This reflects the composition of teams at the time of the study, comprising both managers and clinical experts, with a predominance of managerial roles. Most participants (n=130, 72.2%) reported the need to clarify the clinical specialist role within the organization in relation to specialist and practitioner roles. The majority (n=132, 73.3%) also reported the need to improve information related to advanced practice. Of 132 managers, 116 (87.9%) were interested in working with a clinical specialist. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the relevance of clinical specialists’ activities are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the relevance of clinical specialists’ activities (n=180). Legend -

Totally agree

Totally agree

Agree

Agree

Interviews and a group interview

The results of both interviews and the group interview were categorized as follows: roles, advanced practice professionals, prerequisite for the function, implementation, and main domains.

Two advanced practice roles were described: the clinical specialist and the practitioner specialist. In some institutions, the two advanced practice roles were not clearly distinguished. The titles adopted for the roles varied between institutions and cantons. Nevertheless, the participants emphasized the importance of distinguishing between the two roles. Another Swiss university hospital had a career advancement framework consisting of eight levels for nurses, midwives, and other healthcare professionals. This framework allowed for progression in clinical practice, management, and education. Furthermore, within the hospital departments, governance was shared among these three partners [25]. The advanced practice roles could be held by nurses, midwives, physiotherapists, medical radiology technicians, dietitians, and optometrists, among others. However, most advanced practice providers were nurses.

An advanced practice role required a master’s level education, expertise in a specific area, and a minimum of 2 to 5 years of experience in healthcare. The experience and the additional educational training were the main differences between the levels.

The participants recommended utilizing a structured implementation framework for advanced practice and developing a communication plan to facilitate role clarification. They also stressed the importance of staying focused on the planned activities to achieve the desired results.

The domains highlighted depended on the expert’s profile and assigned mandates. Prominent domains included direct clinical care (through clinical practice in complex situations and consultations), education, management and multidisciplinary meetings, care project development, conferences, and committees.

Results of the action research: the action plan

The action plan was developed collaboratively with all group members linking the findings from the interviews, the survey and literature on the implementation of advanced practice roles. It belongs to the developing stage of this action-research cycle (see Fig. 2).

Description of profiles

The first objective of this study was to describe the roles of specialized nurse and allied healthcare professionals, clinical specialists, and practitioners. From previous studies [2, 5, 7, 13–15, 26–31], as well as data collected with the questionnaire, interviews, and a group interview, descriptive profiles for both specialist and advanced practice professional roles were developed to ensure a shared understanding. Supplementary Table 5 (Additional file 4) provides a detailed description of these roles. The ambiguity surrounding advanced practice and specialist roles, as well as the need for clarification expressed by members of the working group and healthcare professionals from HUG, motivated the creation of these descriptive profiles. Delineating roles will reduce ambiguity within the organization and among stakeholders [27]. The development of clear role descriptions is a critical point for policy making and role implementation [32]. This strategy could help to avoid tensions related to understanding role boundaries, developing professional identity, and exercising role autonomy [27].

Role clarification and initiatives aiming to support advanced practice

The second and third objectives of this study were to clarify the differences between specialist and advanced practice roles and to propose initiatives aimed at supporting the implementation of advanced practice within our organization.

As consistent titles within a country and organization are recommended to promote clarity of roles, the working group suggested adopting the terminology that will be used in Switzerland for these roles [27, 33, 34]. The regulation of advanced nursing practice is expected to be released in the spring of 2026, providing clarity on titles and scopes of practice for nurses. Inconsistent use of titles creates role confusion and is a persistent barrier to the effective use of nursing resources [3, 6, 27, 35]. Ensuring title consistency can help define advanced practice role positions in the healthcare workforce [27, 32].

After the descriptive roles and title uniformization, another suggestion was to update career paths in the clinical field and develop concise summaries for each role accompanied by an illustrative example. Specifying a clear career pathway contributes to future role retention and sustainability [27]. Such a pathway is currently under work and should be available at the end of 2025.

Development of a tool to facilitate the choice of the right role for a given activity

Work sessions led the second group to develop a tool based on the participatory, evidence-based, patient-focused process for advanced practice nursing role development, implementation, and evaluation (PEPPA) framework [36]. According to the leaders of several healthcare institutions in Switzerland and various studies [36–39], the use of the PEPPA framework [36] is recommended to guide advanced practice implementation. Considering the complexity and time required to use this framework, the group members developed a tool based on this model to streamline the selection of the most suitable clinical expert profile for a given activity. This tool facilitated stakeholders’ engagement in pinpointing the required profile, as recommended by the PEPPA model [36]. The tool consists of an interview guide with 18 questions and a grid classifying the answers into five categories and 18 subcategories. Supplementary Table 6 (Additional file 5) provides an overview of these categories and subcategories. The categories were created from the descriptions of each role that had been previously developed. The questions are aimed at stakeholders within the environment where the new expert role is to be implemented. They seek to understand the activities and skills expected by the stakeholders, helping to determine the right role for the desired activities. The instrument has already been used four times since January 2022 to determine the clinical role required for certain activities within the institution. In practice, three focus groups were conducted with the stakeholders, including caregivers, patients, management executives, and human resources. After each focus group, the results were validated with the participants. The results lead to the implementation of two clinical nurse specialists, a clinical physiotherapy specialist, and a specialized nurse.

Developing clinical specialist roles

To develop clinical specialist roles, the proposals included appointing clinical specialists to oversee specific areas of care, mirroring other Swiss university hospital models, and introducing these roles into the existing governance model across various departments [25].

Developing practitioners’ roles

The members of the working group recommended collaboration with nursing and medical management to introduce nurse practitioners for the follow-up of specific patient cohorts. Engaging stakeholders in the process will allow for a more precise identification of needs and the establishment of shared goals for a clearly defined advanced practice role [6, 29, 32, 36]. This will enhance understanding of advance practice roles and promote the optimal use of knowledge, skills, and expertise across all domains and scopes of practice [36]. Further discussions with the authorities were also suggested to establish regulations, more specifically for nurse practitioners. The involvement of policymakers could help to shape policies, secure necessary resources, and ensure the recognition and support of advanced practice roles [6, 32]. Following this recommendation, two nurse practitioners were introduced, with four more currently undergoing training. The tool outlined by Cancer Care Ontario for integrating new advanced practice roles was utilized to engage stakeholders, clearly define the required activities for the role, and establish expected outcomes [40]. Discussions between local authorities and the Nursing and Health Care Directorate resulted in an adaptation of the existing regulatory framework, enabling nurse practitioners to be employed within a state institution.

Communication plan

This work has revealed the need to design and implement an internal and external communication plan to complement the clarification process and support the implementation of advanced practice. Supplementary Table 7, (Additional file 6) details the communication plan. This strategy is advocated by several studies [27, 29, 37, 41]. The communication plan focused on advanced practice roles, their scope of practice, Swiss regulations, required training, advanced practice in other contexts, and outcomes related to patients, teams, and the system. Presentations were held in the presence of the Nursing and Allied Healthcare Professionals Directorate, Medical Directorate, departmental nursing and medical directors, and a local politician. This initiative clarified advanced practice for nursing and medical leaders within the institution and at the political level, engaging them and gaining their support for deploying advanced practice roles. Collaboration among policymakers, organizations, and healthcare professionals is essential for integrating these roles into the health system [6, 32, 42]. In September 2023 and 2024, a symposium was held for healthcare professionals from both within and outside the hospital to present and discuss various topics related to advanced practice. These topics included regulations, roles, scopes of practice, training, and outcomes. The event aimed to promote national awareness of advanced practice roles, reduce barriers to their adoption, and educate stakeholders and decision makers about their benefits. To provide a comprehensive solution, group members updated the institution’s website (link) to reach a broader audience and prevent confusion issuing from outdated information on advanced practice.

Review fundings for training

To further advance the development of advanced practice roles, the group suggested reassessing the access to funding for advanced practice training within the institution. Advocating for dedicated funding to support advanced practice education is crucial for the successful implementation and sustainability of these roles [6, 27]. Discussions are currently taking place to explore more adequate funding schemes.

Discussion

This action research aimed to describe the roles of specialized healthcare professionals, clinical specialists, and practitioners, clarify the differences between these roles and propose initiatives aiming to support the implementation of advanced practice within our organization.

The participants in this study demonstrated significant confusion between the roles of specialized health professionals and those in advanced practice, prompting the research group to delineate these roles and initiate a communication plan to promote clarity. This finding aligns with previous studies [5, 17, 43–46] and the International Council of Nurses guidelines on advanced practice nursing [13], which emphasize the critical need to differentiate between specialized and advanced practice roles in healthcare settings.

The PEPPA framework [36] was originally developed to guide the implementation of advanced practice roles. However, it does not explicitly address the need to distinguish between advanced practice roles and specialized roles. In contrast, the current study sought to address this gap by developing a tool designed to help determine the most appropriate role for a given activity. Our tool might therefore be considered as a complement to existing tools that were already developed to follow the steps of the PEPPA framework [36].

By sharing the results from the data gathering and the action plan, all group members started to reflect on the process by preparing presentations linked to the communication plan and an internal report. The communication plan allowed the involvement of numerous stakeholders, which a critical step outlined in the PEPPA framework [36] and previous studies to raise stakeholders’ awareness about these roles [6, 27, 29, 32, 35, 42, 47, 48]. The implementation of advanced practice was well received, with recognition of the value of advanced practice in optimizing patient care and processes. Stakeholders endorsed the proposals and supported the continued implementation of advanced practice roles. As such, our study confirms the critical role that nurse manager play in the implementation of advanced nursing practice at the institutional level [35, 42, 47–49]. To advance this effort, the head of clinical specialists, two clinical specialists, and a research physiotherapist were asked by the Director of Nursing and Allied Health to collaborate with nurse and allied health managers to design a new governance model, including the creation of clinical specialist roles. This initiative expanded discussions on governance, leading to the introduction of a clinical ladder for nursing and allied health professions. This goes well beyond the initial aims of this action research and can be considered as a new project. Integrating advanced practice roles into strategic workforce plans and clinical governance models could contribute to the successful implementation, retention, and sustainability of these roles [27]. Furthermore, this is an opportunity to systematically operationalize these roles with a clear structure and processes at the institutional level as it is recommended for a successful implementation [35]. The implementation of this new governance model is currently in its early phase.

This research highlights the need for dedicated funding to support advanced practice training and role development, in line with the findings of other studies [6, 27, 29, 32, 39, 44]. Priority has been given to finding solutions for initial training, as currently, advanced practice roles within the institution remain limited in number. Advanced practice education is designed as a full-time program, with the option to complete it part-time over a longer duration. Despite this flexibility, it still poses significant challenges for individuals balancing personal and professional responsibilities while pursuing this education. This challenge becomes more complex for individuals without a Bachelor of Science degree, as they require additional time to complete the necessary studies to be able to enter a Master of Science program. Therefore, providing financial support during the education period could ease the transition and encourage participation in advanced practice programs. As financial aspects are overseen by the managers, involving them in these reflections has been key to raising their awareness of these concerns.

Strengths and limitations

The reflection on the process, its strengths, and limitations, was undertaken by the research authors and ended the action research cycle (see Fig. 2). All group members were invited to actively participate in each step of the action research process: planning, action, development, and reflection. Several meetings facilitated the sharing and analysis of data, leading to the construction of the action plan. This active participation and engagement posed occasionally a threat to the research rigor, as participants engaged in data collection without always audio-taping the interviews. Finally, a subgroup from the initial group were engaged in reflective discussions on the process and contributed as authors of this paper. The entire process spanned 18 months, with its participatory approach yielding a rich dataset and capturing diverse perspectives. The proposed actions were thoughtfully designed to align with the local culture, contributing to their acceptability to all stakeholders. In action research, it is important that the work possesses cultural validity, credibility among stakeholders, practical applicability (i.e., solves a real-world problem) and a transcontextual meaning [20]. This action research actively engaged participants, including managers, in the research process, which fostered their commitment and ownership of the results. This approach led to solutions that were relevant and tailored to our specific context.

However, it was not possible to keep all group members consistently engaged throughout the process due to time constraints and conflicting priorities. By the end of the process, only nine out of fourteen members remained actively involved. Additionally, there was managerial pressure to develop an action plan following the results of the local survey. Balancing the need for immediate action and the need for rigorous research are typical in action research, as the time required for thorough research is not always aligned with institutional timelines [20].

The involvement of the Deputy Nursing Director in the research group provided the authority to propose and plan changes impacting the entire organization. This participation was highly beneficial, as it ensured a deep understanding of institutional norms and facilitated navigation through organizational politics. However, it may also have created an unequal power relationship among the research group influencing participation and decision-making.

The group not only collected internal data but also sought to gain a deeper understanding of the implementation of advanced practice roles by conducting interviews with leaders from other hospitals and performing a literature review. The literature review helped confirm or refine the action plan. It was also encouraging to find that our local findings or actions were similarly described elsewhere, either as barriers, facilitators, or change strategies [6, 17, 27, 29, 32, 35, 39, 42, 44, 47, 48]. Furthermore, an external observer was involved in the reflective phase of the study to evaluate whether she agreed or disagreed with its findings. These measures contribute to the external credibility of the study.

Nevertheless, this study serves to elucidate advanced practice roles and suggests practical strategies for their clarification and implementation. As this problem has been described in several international studies [2–6, 26, 38, 41] the findings of this research may inspire initiatives in other settings.

Conclusions

This action research underscored the importance of defining clear scopes of practice, leading to detailed descriptions for specialists, clinical specialists, and practitioners. It emphasizes the need to clarify these roles and align titles with regulations to avoid confusion. These findings align with those of other researchers who have highlighted this need on an international scale [5, 50]. In this study, we aimed to establish strategies for implementing advanced practice roles within a Swiss French university hospital; however, these strategies may be applicable to other institutions worldwide. This research underscores the importance of a comprehensive communication plan to disseminate accurate and up-to-date information, not only focusing on nursing roles but also encompassing all allied health professionals. Next steps will involve evaluating the tool created to select suitable clinical expert profiles and developing a mechanism to evaluate advanced practice outcomes within the organization. The logic model could be key in achieving this objective [40], as it provides a clear framework outlining the inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impacts of each professional, helping to visualize how resources lead to outcomes [40]. By defining specific outcomes and integrating stakeholders, the logic model facilitates ongoing monitoring and evaluation [40]. This framework could provide opportunities for progress and clarification of specialist and advanced practice roles among healthcare professionals, administrators, and policymakers. To further support advanced practice developments, ongoing discussions at both regional and national political levels will also need to be pursued. Finally, this study has prompted reflection on the nursing and allied health professions governance model in our setting to provide excellence in care.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 2. Characteristics of working group.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 3. Questionnaire assessing healthcare providers’ perceptions about the clinical specialist role.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 4. Interview guide.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 5. Role descriptions of the specialist, clinical specialist, and practitioner.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 6. Categories used to determine the proper role for the desired activities.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table 7. Communication plan.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all employees of HUG who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- APN

Advanced practice nurse

- EFN

European Federation of Nurses Associations

- HUG

Geneva University Hospitals

Authors’ contributions

P.T.M. methodology, investigation, analysis, writing original draft preparation, review and editing. M-J.R. conceptualization, methodology, analysis, investigation, resources, writing, review and editing, supervision, funding. M.E. writing, review and editing. A.D-A. methodology, investigation, analysis, review and editing. S.K. methodology, investigation, analysis, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Geneva Open Access funding for this research was provided by the research fund of the Care Directorate at HUG.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Since this study is part of a process to improve healthcare quality and does not pertain to human health functions, it does not fall under the scope of the Swiss Human Research Act. Additionally, the questionnaires were anonymous, and participants had the choice to respond or not. All participants in the working groups were informed about the study during meetings, and this was recorded in the minutes. As this is action research, participants collaborated with the understanding that the situation needed change. The Director of Nursing and Allied Professions provided her consent for the study. It was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Committee on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Initiative on the Future of Nursing, at the Institute of Medicine; Institute of Medicine. The future of nursing: leading change, advancing health. Washington: National Academies Press; 2011. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/12956. Accessed 1 Nov 2023.

- 2.World Confederation for Physical Therapy: European Region. Advanced practice physiotherapy in the European region of the WCPT position statement. 2018. https://www.erwcpt.eu/_files/ugd/3e47dc_81deca95db8d4b77a64a2ee0db56ee81.pdf. Accessed 26 Aug 2024.

- 3.Parker JM, Hill MN. A review of advanced practice nursing in the United States, Canada, Australia and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR), China. Int J Nurs Sci. 2017;4(2):196–204. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carryer J, Wilkinson J, Towers A, Gardner G. Delineating advanced practice nursing in New Zealand: a national survey. Int Nurs Rev. 2018;65(1):24–32. 10.1111/inr.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jokiniemi K, Bryant-Lukosius D, Roussel J, Kilpatrick K, Martin-Misener R, Tranmer J, et al. Differentiating specialized and advanced nursing roles: the pathway to role optimization. Can J Nurs Leadersh. 2023;36(1):57–74. 10.12927/cjnl.2023.27123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryant-Lukosius D, Martin-Misener R. ICN policy brief: advanced practice nursing: an essential component of country level human resources for health. International Council of Nurses; 2016. https://fhs.mcmaster.ca/ccapnr/documents/ICNPolicyBrief6AdvancedPracticeNursing_000.pdf. Accessed 26 Jun 2024.

- 7.European Federation of Nurses Associations. EFN workforce matrix 3+1 executive summary. 2017. https://www.efn.eu/wp-content/uploads/EFN-Workforce-Matrix-31-Executive-Summary-May-2017.pdf. Accessed 18 Jun 2024.

- 8.Gysin S, Sottas B, Odermatt M, Essig S. Advanced practice nurses’ and general practitioners’ first experiences with introducing the advanced practice nurse role to Swiss primary care: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):163. 10.1186/s12875-019-1055-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGee P, Inman CJ, editors. Advanced practice in healthcare: dynamic developments in nursing and allied health professions. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, editor. Health workforce policies in OECD countries: right jobs, right skills, right places. Paris: OECD; 2016. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-workforce-policies-in-oecd-countries_9789264239517-en.html. Accessed 18 Jun 2024.

- 11.European Coalition for Diabetes Care. Diabetes in Europe: policy puzzle, the state we are in. 2014. https://www.fend.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Policy-Puzzle-PP4finalweb.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2024.

- 12.American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Board certification. https://www.aacn.org/certification?tab=First-Time%20Certification. Accessed 16 Dec 2023.

- 13.Conseil international des infirmières. Directives sur la pratique infirmière avancée 2020. 2020. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/ICN_APN%20Report_FR_WEB.pdf. Accessed 27 Jun 2024.

- 14.Cignacco E, Schlenker A, Amman-Fiechter S, Damke T, de Labrusse CC, Krahl A, et al. Advanced midwifery practice in Switzerland: development and challenges. Eur J Midwifery. 2024;8(April):1–7. 10.18332/ejm/185648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Association suisse des ergothérapeutes. Advanced practice in occupational therapy. 2019. https://www.zhaw.ch/storage/gesundheit/ueber-uns/veranstaltungen/symposien/2021-interprof-ap-symposium/evs-grundlagenpapier-ap-in-ergotherapie-2019-de-u-fr.pdf. Accessed 12 Jun 2024.

- 16.National Health System England. Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England. 2017. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Multi-professional%20framework%20for%20advanced%20clinical%20practice%20in%20England.pdf. Accessed 18 Jun 2024.

- 17.Beckmann S, Schmid-Mohler G, Spichiger E, Eicher M, Nicca D, Ullmann-Bremi A, et al. Mapping advanced practice nurses’ scope of practice, satisfaction, and drivers of role performance. Pflege. 2024. 10.1024/1012-5302/a000980. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Osinska M, Koch R, Mahrer-Imhof R, Zuñiga F. Enquête master 2022 - enquête auprès des diplômés d’un Master of Science in Nursing en sciences infirmières exerçant en Suisse. Berne, Bâle: ASI, APN-CH, INS; 2022. https://apn-ch.ch/assets/News/Masterumfrage-2022_F.pdf. Accessed 22 May 2024.

- 19.Confédération Suisse. Initiative sur les soins infirmiers: nouvelle loi et mesures supplémentaires pour améliorer les conditions de travail. 2023. https://www.admin.ch/gov/fr/accueil/documentation/communiques.msg-id-92653.html. Accessed 11 May 2024.

- 20.Williamson G, Bellman L, Webster J. Action research in nursing and healthcare. London: SAGE Publications; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mertler CA. Action research: improving schools and empowering educators. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linka E, Lanter R, Staudacher D, Rettke H. Laufbahnen ohne Grenzen. Erste Erfahrungen mit dem “USZ-Laufbahnmodell Pflege.” 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336669535_Laufbahnen_ohne_Grenzen_Erste_Erfahrungen_mit_dem_USZ-Laufbahnmodell_Pflege. Accessed 26.08.2024.

- 26.Kilpatrick K, DiCenso A, Bryant-Lukosius D, Ritchie JA, Martin-Misener R, Carter N. Practice patterns and perceived impact of clinical nurse specialist roles in Canada: results of a national survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(11):1524–36. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans C, Poku B, Pearce R, Eldridge J, Hendrick P, Knaggs R, et al. Characterizing the outcomes, impacts and implementation challenges of advanced clinical practice roles in the UK: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(8):e048171. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brault I, Kilpatrick K, D’Amour D, Contandriopoulos D, Chouinard V, Dubois CA, et al. Role clarification processes for better integration of nurse practitioners into primary healthcare teams: a multiple-case study. Nurs Res Pract. 2014;2014:170514. 10.1155/2014/170514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilpatrick K, Tchouaket E, Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A. Structural and process factors that influence clinical nurse specialist role implementation. Clin Nurse Spec CNS. 2016;30(2):89–100. 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jokiniemi K, Hølge-Hazelton B, Kristofersson GK, Frederiksen K, Kilpatrick K, Mikkonen S. Core competencies of clinical nurse specialists: a comparison across three Nordic countries. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(23–24):3601–10. 10.1111/jocn.15882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jokiniemi K, Heikkilä A, Meriläinen M, Junttila K, Peltokoski J, Tervo-Heikkinen T, et al. Advanced practice role delineation within Finland: a comparative descriptive study. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(6):1665–75. 10.1111/jan.15074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jokiniemi K, Suutarla A, Meretoja R, Kotila J, Axelin A, Flinkman M, et al. Evidence-informed policymaking: modelling nurses’ career pathway from registered nurse to advanced practice nurse. Int J Nurs Pract. 2020;26(1):e12777. 10.1111/ijn.12777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheydt S, Hegedüs A. Tasks and activities of Advanced Practice Nurses in the psychiatric and mental health care context: a systematic review and thematic analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;118:103759. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doran D, Duffield C, Risk P, Nahm S, Chu CH. A descriptive study of employment patterns and work environment outcomes of specialist nurses in Canada. Clin Nurse Spec. 2014;28(2):105–14. 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bryant-Lukosius D, Wong FKY. Global development of advanced practice nursing. In: Tracy MF, O’Grady ET, Phillips SJ, editors. Advanced practice nursing: an integrative approach. 7th ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2022. p. 137–65. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bryant-Lukosius D, Spichiger E, Martin J, Stoll H, Kellerhals SD, Fliedner M, et al. Framework for evaluating the impact of advanced practice nursing roles. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016;48(2):201–9. 10.1111/jonm.12759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ninane F, Brioschi Levi H, Lehn I, D’Amour D. Implantation du rôle d’infirmière clinicienne spécialisée dans un centre hospitalier universitaire en Suisse une recherche action. Rev Francoph Int Rech Infirm. 2018;4(4):e215–22. 10.1016/j.refiri.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serena A, Dwyer AA, Peters S, Eicher M. Acceptance of the advanced practice nurse in lung cancer role by healthcare professionals and patients: a qualitative exploration. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2018;50(5):540–8. 10.1111/jnu.12411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aguilard S, Colson S, Inthavong K. Stratégies d’implantation d’un infirmier de pratique avancée en milieu hospitalier: une revue de littérature. Sante Publique (Bucur). 2017;29(2):241–54. 10.3917/spub.172.0241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cancer Care Ontario. Step five: define the new model of care and APN role. In: Advanced practice nursing toolkit. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/treatment-modality/nursing-care/advanced-practice-nursing-toolkit. Accessed 26 Jun 2024.

- 41.Kerr H, Donovan M, McSorley O. Evaluation of the role of the clinical Nurse Specialist in cancer care: an integrative literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021;30(3):e13415. 10.1111/ecc.13415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schober MM, Gerrish K, McDonnell A. Development of a conceptual policy framework for advanced practice nursing: an ethnographic study. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(6):1313–24. 10.1111/jan.12915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gardner G, Duffield C, Doubrovsky A, Adams M. Identifying advanced practice: a national survey of a nursing workforce. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;55:60–70. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Hussein MT, Ha C. Facilitators and barriers to the transition from registered nurse to nurse practitioner in Canada. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2023;35(6):359. 10.1097/JXX.0000000000000868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torrens C, Campbell P, Hoskins G, Strachan H, Wells M, Cunningham M, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the advanced nurse practitioner role in primary care settings: a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;104:103443. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mackavey C, Henderson C, van Leeuwen E de Z, Maas L, Ladd A. The advanced practice nurse role’s development and identity: an international review. Int J Adv Pract. 2024;2(1):36–44. 10.12968/ijap.2024.2.1.36. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jokiniemi K, Haatainen K, Meretoja R, Pietilä AM. Advanced practice nursing roles: the phases of the successful role implementation process. Int J Caring Sci. 2014;7(3):946–54. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:37429731. Accessed 17 Dec 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jokiniemi K, Kärkkäinen A, Korhonen K, Pekkarinen T, Pietilä A. Outcomes and challenges of successful clinical nurse specialist role implementation: participatory action research. Nurs Open. 2023;10(2):704–13. 10.1002/nop2.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Unsworth J, Greene K, Ali P, Lillebø G, Mazilu DC. Advanced practice nurse roles in Europe: implementation challenges, progress and lessons learnt. Int Nurs Rev. 2024;71(2):299–308. 10.1111/inr.12800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kilpatrick K, Tewah R, Tchouaket E, Jokiniemi K, Bouabdillah N, Biron A, et al. Describing clinical nurse specialist practice: a mixed-methods study. Clin Nurse Spec CNS. 2024;38(6):280–91. 10.1097/NUR.0000000000000856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 2. Characteristics of working group.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 3. Questionnaire assessing healthcare providers’ perceptions about the clinical specialist role.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 4. Interview guide.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table 5. Role descriptions of the specialist, clinical specialist, and practitioner.

Additional file 5: Supplementary Table 6. Categories used to determine the proper role for the desired activities.

Additional file 6: Supplementary Table 7. Communication plan.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.