Abstract

Background

Monitoring HIV infection estimates is critical to guide health interventions and assess their impact, especially in highly vulnerable groups to the infection such as African pregnant women. This study describes the trends of HIV infection over eleven years in women attending selected antenatal care (ANC) clinics from southern Mozambique.

Methods

We performed a secondary analysis of data registered at the ANC clinic of the Manhiça District Hospital and from the Ministry of Health's HIV National Program Registry between 2010 and 2021. HIV incidence was calculated using prevalence estimates. HIV incidence trends over time were obtained by fitting splines regression model.

Results

Data from 21,810 pregnant women were included in the analysis. Overall HIV prevalence was 29.3% (95% CI: 28.7–29.9), with a reduction from 28.2% (95% CI: 25.6–30.8) in 2010 to 21.7% (95% CI: 19.8–23.6) in 2021, except for a peak in prevalence (35.3%, 95% CI: 30.1–40.8) in 2016. Over the study period, by maternal age group, the largest reduction in HIV prevalence was in the 15–20 year-old group [62% reduction, from 14.3% (95% CI 10.8–18.4) to 5.3% (95% CI: 3.6–7.5)], followed by the 20–25 year old group [43% reduction, from 29.0% (95% CI: 24.2–34.5) to 16.6% (95% CI: 13.6–19.8)] and the 25–30 year old group [13% reduction, from 36.9% (95% CI: 31.0–43.1) to 32.0% (95% CI: 27.3–37.0)] (p < 0.001). Incidence of HIV infection increased from 12.75 per 100 person-years in 2010 to 18.65 per 100 person-years in 2018, and then decreased to 11.48 per 100 person-years in 2021.

Conclusions

The prevalence of HIV decreased while the overall incidence stayed similar in Mozambican pregnant women, during 2010 to 2021. However, both estimates remain unacceptably high, which indicates the need to revise current preventive policies and implement effective ones to improve HIV control among pregnant women.

Keywords: HIV; Prevalence; Incidence; Pregnancy; Manhiça, Mozambique

Introduction

HIV infection continues to be a major global public health problem with an estimated 39 million (33.1—45.7 million) deaths due to the infection since the beginning of the epidemic [1]. Eastern and southern Africa contribute with the highest burden of the infection harbouring more than half (20.8 million) of all individuals living with HIV in the world [2].

Mozambique is one of the countries where the HIV epidemic stroke hardest, with an estimated 2.4 million (2.2- 2.6 million) people living with HIV (12.5% of the population), in 2023 [3]. HIV infection incidence in the country was estimated at 150,000 (85,000–240,000) new infections per year in the decade 2000–2010 [4, 5]. Since then, the number of new HIV infections has decreased although it remains high with an estimated 87,000 (72,000–108,000) new infections in 2023 [6]. Women, especially between 15 and 24 years of age are disproportionately affected by HIV being three times more likely to be infected (9.8%) compared to men (3.2%) while carrying an increased risk of complications if pregnant [7] and affecting both the mother and the offspring [8]. HIV-infected pregnant women are at higher risk for infections and anaemia, which can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes also heightens the risk of vertical transmission of HIV [9].

Globally, the decline in HIV incidence has stalled since 2017, which may be explained by the continued limited timely access to effective HIV control interventions by underserved groups, such as African women of reproductive age, especially those living in rural areas [10]. In Mozambique, since 2013, the national HIV control program recommends Option B + consisting of lifelong administration of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to all HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women, and since 2016, to universal test and treat irrespective of the CD4 + cell counts [11, 12]. The package of interventions to manage advanced HIV disease (AHD), including screening, treatment and/or prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, rapid ART initiation and intensified adherence support for those identified with AHD was introduced in 2018. In 2019, dolutegravir (DTG)-based regimens replaced other ARV drugs as first line ART [13]. However, evidence of the impact of these interventions on pregnant women’s health remains scarce [14, 15].

Monitoring the epidemiological trends of HIV infection among pregnant women can improve assessing the effectiveness of control strategies and help guide their design for greater impact. In this study, we analysed the trends in HIV infection among pregnant women in southern Mozambique over an eleven-year period.

Methods

Study area

All studies included in this analysis were conducted in Manhiça District, located 80 km north of Maputo. The Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça (CISM) runs a Demographic and Health Surveillance System (DHSS) since 1996 [16]. There are 23 health centers in the District, one rural hospital and one referral hospital, the Manhiça District Hospital (MDH) [17]. The area is endemic for malaria infection [18]. HIV prevalence in women attending the antenatal care (ANC) visit was 29% in 2010 [19]. National estimates from 2023 indicate that the majority of HIV-infected pregnant women who initiated ART at the ANC were compliant with ART three months after they began to receive it [3, 20].

The HIV control program in Mozambique

At the time of diagnosis, HIV-positive individuals are registered into the HIV National Program Registry and receive a unique numeric identifier (NID) to allow patient tracking [21]. A blood sample for CD4 + cell count is collected and the test is repeated only if clinical failure is suspected; HIV viral load is measured six months after ART initiation [22]. First line ART in adults consisted of tenofovir (TDF) /lamivudine (3TC) /efavirenz (EFV) or zidovudine (AZT) /3TC /nevirapine (NVP) and second line consisting of AZT /3TC /lopinavir-ritonavir (LPV/r) or abacavir (ABC) /3TC /LPVr, which changed in 2019 when DTG replaced EFV [23, 24]. Pregnant women attending an ANC clinic for the first time are offered HIV testing and if the result is negative, HIV testing is repeated every three months until the end of breastfeeding. If the HIV test is positive, ART for prevention of mother to child transmission (MTCT) of HIV is initiated and ART is provided monthly throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis (CTXp) is also given during pregnancy to HIV-infected pregnant women and continued until cessation of breastfeeding, regardless of the CD4 + cell count.

Study design

This is a secondary analysis of data collected from three clinical studies conducted during ANC visits at four district health facilities (MDH, Maragra, Nwamatibjana, and Ilha Josina) between 2010 and 2021. Following national guidelines, all pregnant women were screened for HIV infection at their first ANC visit. The studies included in this analysis have been described previously [25–27]. In brief, the first study was a clinical trial conducted between March 2010 and December 2011 to evaluate the safety and efficacy of mefloquine as intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) for malaria [25]. The second study, conducted between October 2016 and October 2019, explored the burden of malaria in pregnancy across different levels of malaria transmission and immunity [26]. The third study, conducted from November 2019 to November 2021, was a clinical trial assessing the safety and efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for IPTp in HIV-infected women [27]. An additional dataset came from routine data collected by the Ministry of Health (MoH)'s HIV National Program Registry, containing aggregated data from pregnant women attending ANC at MDH and Nwamatibjana health center. This data, covering the period from January 2012 to December 2015, was used to calculate HIV prevalence.

HIV infection was determined using either an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or the Determine HIV-1/2 Rapid Test (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), with positive results confirmed using the Uni-Gold Rapid Test (Trinity Biotech Co., Wicklow, Ireland). The HIV status of HIV-exposed children was assessed using dried blood spots and the Amplicor HIV-1 DNA-PCR kit (Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, New Jersey, USA) at all health facilities, except at MDH, where some children were tested using the Abbott mPIMA Point-of-Care (POC) platform [28]. Hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was measured using a portable Hb spectrophotometer, the Hemocue Hb 201 analyzer (HemoCue, Ängelholm, Sweden), along with a microcuvette (Hemocue Hb 201 Microcuvette, HemoCue, Ängelholm, Sweden).

Statistical analysis

Yearly HIV prevalence and a 95% confidence interval were estimated based on the studies mentioned above and the MoH's HIV National Program Registry. The changes in HIV prevalence across years between women age groups were assessed using logistical regression model containing main and interaction effects of age group and time. HIV incidence was calculated using prevalence estimates from the clinical studies, as the routine data set from the MoH's HIV National Program Registry did not include information on the women's ages. This calculation followed the model developed by Hallett, which has been validated in various settings [29–32]. This model is based on the synthetic cohort principle and relies on the decomposition of prevalence changes by age group of width between two cross-sectional prevalence estimates separated by years of time, and it assumes that individuals of age in the first prevalence estimate will be represented by individuals aged years in the second prevalence estimate. In the present analysis, the HIV prevalence estimates of the years 2010, 2011, 2012, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021 were used to calculate the HIV incidence. Two methods were used to calculate HIV incidence over the study period. The first method—“method 1”-, uses mortality rates, while the second method—“method 2” -, uses survival data after HIV infection. For the method 1, three HIV scenarios were assumed, namely the early (defined as epidemics that are still expanding), stable (epidemics that have stopped expanding) and declining epidemic (epidemics that are in decline). The pattern over time was obtained by fitting b-splines regression model with piecewise cubic polynomials, having incidence as the dependent variable and the year as predictor. The frequency of MTCT of HIV and the prevalence of maternal anemia were also estimated for the period 2010—2021. The prevalence of MTCT of HIV was calculated as the number of HIV-infected children divided by the number of children born to HIV-infected women in each study. Anaemia was defined as a hemoglobin concentration lower than 11 g/dL. Mild anaemia was defined as a Hb concentration of 10–10.9 g/dL, moderate anaemia as a Hb of 7–9.9 g/dL, and severe anaemia as a Hb < 7 g/dL [33]. The Chi-squared Test was used to assess trends of MTCT of HIV and anaemia for the period 2010–2021. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using R® software (version 4.2) [34] and RStudio (version 2022.12) [35].

Results

Characteristics of study participants at first antenatal care visit

Data from 21,810 pregnant women were included in the analysis, of these, 12,256 (56.2%) women were participants in the three clinical studies, and 9,554 (43.8%) women provided data included in the MoH's HIV National Program Registry. Table 1 shows the participant’s characteristics at first ANC visit. The median maternal age was 23.6 years (interquartile range (IQR): 19.0–29.0) while the median gestational age was 20.0 weeks (IQR 16.0–24.0). A significant reduction was observed in gestational age at first ANC visit over the eleven-year period of the analysis (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women from the three studies at first antenatal care visit in 2010, 2011, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021

| Year | 2010 N = 1215 n (%) |

2011 N = 1643 n (%) |

2016 N = 320 n (%) |

2017 N = 1815 n (%) |

2018 N = 1901 n (%) |

2019 N = 1605 n (%) |

2020 N = 1832 n (%) |

2021 N = 1925 n (%) |

Total N = 12,256 n (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): median (IQR) |

23.9 (19.5–29.3) |

24.2 (19.5–29.9) |

24.0 (21.0–30.0) |

24.0 (20.0–30.0) |

24.0 (20.0–30.0) |

23.0 (19.0–30.0) |

23.0 (19.0–29.0) |

23.0 (19.0–29.0) |

23.6 (19.0–29.0) |

< 0.001* |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| [15 – 20) | 351 (28.9) | 447 (27.2) | 50 (15.6) | 443 (24.4) | 472 (24.8) | 410 (25.5) | 506 (27.6) | 552 (28.7) | 3255 (25.3) | < 0.001** |

| [20 – 25) | 339 (27.0) | 438 (26.7) | 117 (36.6) | 529 (29.1) | 552 (29.0) | 474 (29.5) | 539 (29.4) | 580 (30.1) | 3587 (30.4) | |

| [25 – 30) | 255 (21.0) | 352 (21.4) | 63 (19.7) | 377 (20.8) | 394 (20.7) | 303 (18.9) | 383 (20.9) | 375 (19.5) | 2518 (21.2) | |

| [30 – 35) | 185 (15.2) | 234 (14.2) | 53 (16.6) | 288 (15.9) | 278 (14.6) | 234 (14.6) | 233 (12.7) | 236 (12.3) | 1754 (13.8) | |

| [35 – 40) | 60 (4.9) | 122 (7.4) | 30 (9.4) | 134 (7.4) | 160 (8.4) | 142 (8.8) | 136 (7.4) | 139 (7.2) | 924 (7.3) | |

| [40 – 45) | 26 (2.2) | 50 (3.0) | 7 (2.2) | 44 (2.4) | 45 (2.4) | 42 (2.6) | 35 (1.9) | 45 (2.2) | 276 (2.4) | |

| Gestational age (weeks): median (IQR) | 23.0 (19.0–27.0) | 23.0 (18.0–27.0) | 21.0 (17.0–25.0) | 20.0 (16.0–24.0) | 20.0 (16.0–24.0) | 20.0 (16.0–24.0) | 19.0 (16.0–24.0) | 20.0 (16.0–24.0) | 20.0 (16.0–24.0) | < 0.001* |

* Kruskal Wallis test testing for differences across years in median age

**Chi2 test testing for differences in distribution of age group categories across years

HIV prevalence in pregnant women over time

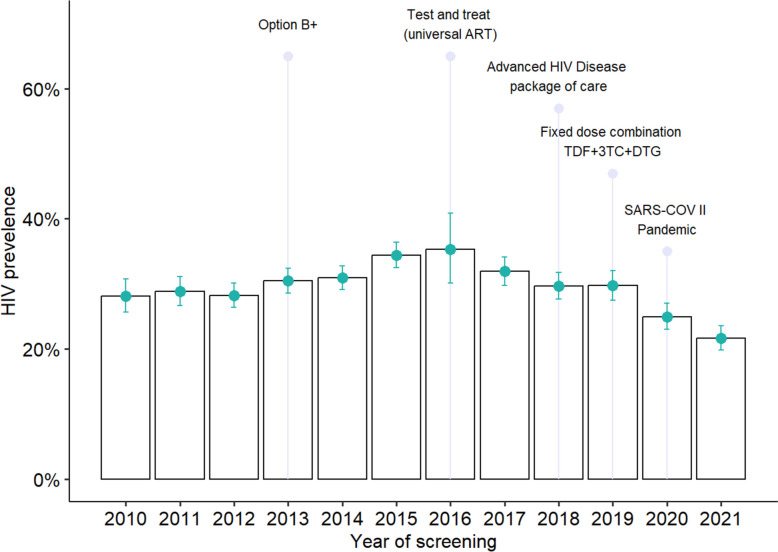

Throughout the study period, the overall prevalence of HIV infection was 29.3% (95% CI: 28.7–29.9). Figure 1 shows the annual HIV prevalence estimates from 2010 to 2021, highlighting the timing of HIV control interventions and the onset of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. HIV prevalence increased from 28.2% (95% CI: 25.6–30.8) in 2010 to a peak of 35.3% (95% CI: 30.1–40.8) in 2016. Then, there was a significant 23.0% decrease in prevalence by 2021, dropping to 21.7% (95% CI: 19.8–23.6) after the introduction of DTG-based regimens in 2019, compared to 2010 (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of pregnant women living with HIV at the ANC Manhiça District per year and timing of implementation of HIV control interventions and SARS-COV II pandemic during 2010—2021

Figure 2 presents the proportions of pregnant women living with HIV at the ANC per year at the Manhiça District by age group over the study period (2010–2021). The most substantial reduction in HIV prevalence occurred in the 15–20 year-old group, with a 62% decrease [from 14.3% (95% CI: 10.8–18.4) to 5.3% (95% CI: 3.6–7.5)]. This was followed by a 43% reduction in the 20–25 year-old group year age group [from 29.0% (95% CI: 24.2–34.5) to 16.6% (95% CI: 13.6–19.8)], and a 13% reduction in the 25–30 year-old group [from 36.9% (95% CI: 31.0–43.1) to 32.0% (95% CI: 27.3–37.0)] (p < 0.001 for all). In contrast, HIV prevalence increased between 2010 and 2021 in the 30–35, 35–40, and 40–45 year age groups, by 12%, 34%, and 25%, respectively. However, these increases were not statistically significant (p-values: 0.831, 0.679, and 0.531).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of pregnant women living with HIV at the ANC per year at the Manhiça District by age group during 2010—2021

HIV incidence estimates in study participants

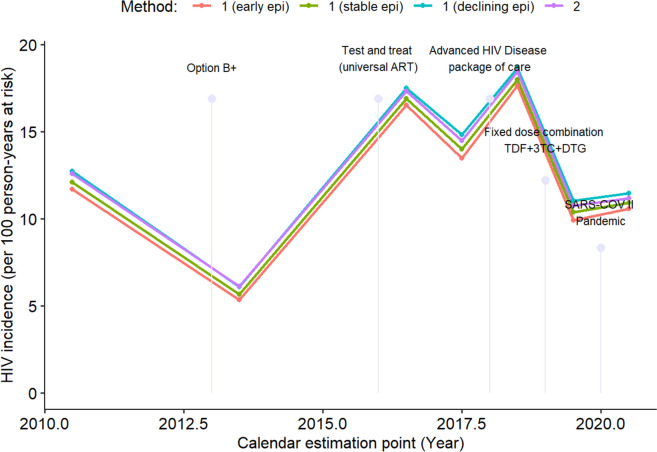

Table 2 presents the HIV incidence rates calculated at the mid-point between prevalence estimates using both estimation methods and the three epidemic scenarios described above. The HIV incidence rates estimated by "method 2" closely matched the declining incidence rates calculated by "method 1." Fig. 3 HIV incidences trends and the timing of various HIV control interventions implemented during the study period. According to the declining incidence curve from "method 1", HIV incidence significantly increased from 12.75 infections per 100 person-years in mid-2010 to a peak of 18.65 infections per 100 person-years in mid-2018. Subsequently, HIV incidence decreased to 11.48 infections per 100 person-years by 2020–2021, following the introduction of the advanced HIV disease care package and first-line DTG-based ART in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Since the MoH's National HIV Program Registry routine dataset lacked information on women's ages, an HIV incidence prediction model was employed to estimate incidence for the period 2012–2015 (Fig. 4). The trend in HIV incidence shown in Fig. 4 aligns with the curve in Fig. 3, which is based on HIV incidence calculated exclusively from prevalence estimates derived from clinical studies.

Table 2.

HIV incidence estimate for pregnant women aged [15–45) years based on method 1 (estimates incidence from prevalence under three scenarios of mortality) and on method 2 (estimates incidence from prevalence of survival information after HIV infection)

| Calendar estimation point | Prevalence Surveys (Year) | Estimated incidence using Method 1 | Estimated incidence using Method 2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early | Stable | Declining | |||

| 2010.5 | 2010, 2011 | 6.23 [4.59—9.34] | 6.63 [4.89—9.70] | 7.27 [5.36—10.25] | 7.16 [5.29—10.09] |

| 2011.5 | 2011, 2012 | 29.09 [10.69—42.38] | 29.42 [10.96—42.63] | 29.92 [11.3—42.98] | 29.53 [11.12—42.70] |

| 2014.5 | 2012, 2016 | 2.71 [1.48 – 6.00] | 2.95 [1.62—6.27] | 3.65 [1.88—6.74] | 3.83 [2.01—6.75] |

| 2016.5 | 2016, 2017 | 8.43 [5.29—12.16] | 8.8 [5.61—12.51] | 9.36 [6.13—13.05] | 9.23 [6.07—12.87] |

| 2017.5 | 2017, 2018 | 7.08 [5.14—9.97] | 7.58 [5.51—10.44] | 8.35 [6.14—11.12] | 8.06 [5.93—10.79] |

| 2018.5 | 2018, 2019 | 9.01 [6.75—12.28] | 9.43 [7.13—12.7] | 10.16 [7.76—13.35] | 9.98 [7.65—13.13] |

| 2019.5 | 2019, 2020 | 5.24 [3.68—8.49] | 5.65 [3.97—8.89] | 6.32 [4.54—9.55] | 6.09 [4.38—9.25] |

| 2020.5 | 2020, 2021 | 5.46 [3.88—7.96] | 5.79 [4.15—8.28] | 6.30 [4.60—8.78] | 6.07 [4.43—8.51] |

The incidence was calculated as weighted mean of the age-group incidences, with weights based on age-group sample size: per 100 person-years (95% CI interval). The three scenarios: early (defined as epidemics that are still expanding), stable (epidemics that have stopped expanding) and declining epidemic (epidemics that are in decline)

Fig. 3.

HIV incidence estimate for individuals aged [15–50) and timing of implementation of HIV control interventions and SARS-COV II pandemic during 2010 – 2021

Fig. 4.

HIV incidence prediction model employed to estimate incidence for the period 2012–2015, since the MoH's National HIV Program Registry routine dataset lacked information on women's ages

Anaemia prevalence in study participants

Haemoglobin concentration data was available for 1,576 (46.0%) of the 3,423 HIV-positive pregnant women included across the three studies (Table 3). A majority (60.4%; 796/1,337) of these women experienced some degree of anaemia: mild (26.1%), moderate (31.6%), or severe (2.7%). Over the 11-year study period, the overall proportion of women presenting with anaemia at their first ANC visit decreased by 32%, from 66.4% (95% CI 61.1–71.4) to 45.2% (95% CI 38.7–51.9) (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Proportion of anaemia among pregnant women living with HIV at the ANC of the Manhiça District during 2010 – 2021

| Year | 2010 N = 342 n (%) |

2011 N = 474 n (%) |

2016 N = 37 n (%) |

2017 N = 170 n (%) |

2018 N = 32 n (%) |

2019 N = 28 n (%) |

2020 N = 263 n (%) |

2021 N = 230 n (%) |

Total N = 1576 n (%) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin Mean (SD) | 10.3 (1.8) | 10.1 (1.9) | 10.1 (1.7) | 10.4 (1.8) | 10.3 (2.0) | 10.9 (1.4) | 11.0 (1.4) | 11.0 (1.7) | 10.5 (1.8) | < 0.001 |

| Anaemiaa | ||||||||||

| No |

114 (33.6) |

131 (28.5) |

9 (24.3) |

59 (35.1) |

14 (43.8) |

16 (57.1) |

135 (51.5) |

126 (54.8) |

604 (38.8) |

< 0.001 |

| Yes |

225 (66.4) |

328 (71.5) |

28 (75.7) |

109 (64.9) |

18 (56.2) |

12 (42.9) |

127 (48.5) |

104 (45.2) |

951 (61.2) |

|

| Anaemia levelsb | ||||||||||

| Mild |

96 (28.3) |

124 (27.0) |

10 (27.0) |

44 (26.2) |

6 (18.8) |

4 (14.3) |

66 (25.2) |

54 (23.5) |

404 (26.2) |

|

| Moderate |

116 (34.2) |

185 (40.3) |

17 (45.9) |

59 (35.1) |

9 (28.1) |

8 (28.6) |

61 (23.3) |

47 (20.4) |

502 (32.6) |

|

| Severe |

13 (4.9) |

19 (3.7) |

1 (3.5) |

6 (2.2) |

3 (1.6) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

3 (1.3) |

47 (2.9) |

< 0.001 |

SD Standard deviation, N number per year, n number according to the variable categories

a Anaemia was defined as a hemoglobin (Hb) concentration lower than 11 g/dL

bAnaemia levels defined by Hb concentration: mild (10–10.9 g/dL), moderate (7–9.9 g/dL), and severe (< 7 g/dL)

Frequency of MTCT of HIV

During the study period, the prevalence of MTCT of HIV decreased from 9.2% in 2010, to 5.5% in 2018, and then significantly to 0.6% in the study carried out in 2019–2021, coinciding with the introduction of the fixed dose combination of TDF + 3TC + DTG as first line ART.

Discussion

This study provides the longest descriptive analysis of HIV prevalence and incidence trends among pregnant women in Africa. Notably, the inclusion of data from two years following the introduction of the DTG-based regimen as first-line ART offers a valuable opportunity to indirectly assess its impact on HIV control. Despite efforts, HIV prevalence among Mozambican pregnant women remained high throughout the eleven-year period (2010–2021). Additionally, the incidence of new infections was alarmingly high, exceeding the threshold of three infections per 100 person-years, which defines high-risk areas for HIV acquisition [36]. These findings highlight that the HIV epidemic continues to pose a significant public health challenge in this region of southern Africa.

HIV prevalence rose from 28.2% in 2010 to a peak of 35.3% during 2012–2016, then declined to 21.7% in 2021. The initial increase can be attributed to expanded testing efforts, driven not only by the implementation of Option B + in 2013 but also by the adoption of the test-and-treat policy in 2016, which improved HIV diagnosis rates [11]. According to literature, incidence and prevalence in high-risk groups often rise sharply in the early stages of an epidemic, as observed in this analysis between 2010 and 2016. As the epidemic progresses, the rate of contact with already infected individuals increases, reducing the reproduction of the virus and slowing the rise in incidence. Eventually, incidence declines while prevalence can continue to rise if people living with HIV on ART survive, or prevalence decreases if mortality exceeds the incidence rate [37]. However, this pattern does not fully explain our findings, as the study focused on a fixed age group (15–30 years) with a constantly changing population. Therefore, the prevalence decline observed after 2016 likely reflects a reduction in new infections.

The HIV prevalence and incidence trends observed in this study align with those reported in other sub-Saharan African countries among pregnant women during the same period [38]. For instance, in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, HIV prevalence increased from 35.3% in the pre-ART era (2001–2003) to 39.3% during the ART rollout (2009–2013), similar to the pattern seen in Manhiça. Likewise, an analysis of nationwide surveillance data from pregnant women in Botswana showed a decline in HIV prevalence from 25.8% in 2015 to 22.7% in 2019, coinciding with the implementation of control measures such as Option B + , universal test and treat, and DTG-based regimens [39].

The HIV prevalence estimated in this analysis is lower than that reported for pregnant women attending ANC in the same area during 2000–2010, when prevalence rose from 12% in 1999 to 49% in 2008 [19, 40]. Additionally, the HIV incidence trend observed in this study is also lower than that of the previous decade, which showed a stable incidence of approximately 12 cases per 100 person-years [40]. In this analysis, after adjusting for age group population size, the HIV incidence calculated using method 2 (based on mortality rates) closely aligned with the incidence calculated using method 1 (based on survival after HIV infection), lending greater reliability to the results. This consistency suggests that the HIV epidemic among pregnant women in Mozambique is in a mature or declining phase. The observed decline is likely due to the improved rollout of ART, particularly the switch from EFV to DTG as first-line treatment, as DTG leads to rapid viral suppression [11, 13]. This shift may also explain the significant reduction in mother-to-child transmission of HIV observed in the area since 2019 [41].

The mean gestational age of women attending the first ANC visit decreased during the study period from 23 to 20 weeks, although this is still far from the first trimester recommended by the WHO to attend the first ANC [42]. The late ANC attendance has negative implications in the effective prevention of MTCT of HIV, especially in naïve HIV-positive women, since it is recommended that ART during pregnancy starts at least 24 weeks prior to delivery to adequately reduce MTCT of HIV [43]. Efforts are thus also needed to improve early ANC attendance.

Although the overall prevalence of anaemia remained high, there was a notable decline in the proportion of HIV-positive women with anaemia during the study period. Previous studies indicate that anaemia prevalence is high among ART-naïve HIV-positive pregnant women and tends to decrease once ART is initiated [44]. The reduction in anaemia prevalence from 66.4% in 2010 to 45.2% in 2021 may be linked to the implementation of Option B + and the test-and-treat strategy, which increased the number of pregnant women receiving ART early in their pregnancies. Additionally, currently recommended ARV medications are associated with a lower risk of anaemia. Nevertheless, these findings highlight the need for more frequent anaemia screening and management for HIV-positive pregnant women.

The main limitation of this study is that the data originated from studies not specifically designed to assess HIV estimates. However, these studies were conducted in comparable settings, with the populations consistently comprising pregnant women. Additionally, sensitivity analyses—systematically omitting each prevalence point estimate revealed no significant differences in the shape or magnitude of the incidence estimates. Therefore, the prevalence estimates are sufficiently robust to accurately reflect the scale of the epidemic in the study area. Also, due to the lack of information on HIV-associated mortality in Mozambique, the incidences calculated using method 1 were based on mortality rates from neighbouring countries. Finally, the small sample size in older age groups (> 40 years) resulted in wide 95% confidence intervals, leading to less precise estimates for that group. Nevertheless, the findings can provide valuable insights for monitoring the HIV epidemic among one of the most vulnerable populations to the infection.

Conclusions

Estimates of HIV infection among Mozambican pregnant women have decreased over the past decade, likely due to the expansion of treatment and control strategies. However, the burden of infection remains unacceptably high within this vulnerable population, raising concerns that it may become a neglected condition. These findings underscore the urgent need for enhanced and innovative HIV control strategies for pregnant women in high-burden countries.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants and the healthcare workers from Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça and Manhiça District Hospital who assisted with data collection, and the district health authorities, the Ministry of Health and the Fundação Ariel Glaser contra o SIDA pediátrico for their collaboration on the on-going research activities in the Manhiça district.

Abbreviations

- ABC

Abacavir

- AHD

Advanced HIV disease

- ANC

Antenatal care

- ART

Antiretroviral therapy

- ARV

Antiretroviral

- AZT

Zidovudine

- CI

Confidence interval

- CISM

Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça

- CNBS

Comité Nacional de Bioética para Saúde

- CTXp

Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis

- DHSS

Demographic and Health Surveillance System

- DTG

Dolutegravir

- EFV

Efavirenze

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- POC

Point-of-Care

- Hb

Hemoglobin

- IQR

Interquartile range

- IPTp

Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy

- LPV/r

Lopinavir-ritonavir

- MDH

Manhiça District Hospital

- MoH

Ministry of Health

- MTCT

Mother to child transmission

- NID

Numeric identifier

- NVP

Nevirapine

- PMTCT

Prevention of mother to child transmission

- TDF

Tenofovir

- 3TC

Lamivudine

Authors’ contributions

Project conception and protocol design: CM, TN, RG. Coordination of clinical data collection: RG, AV, AM, MM, GM, AM, EM, PV, PA, ES, AC, NF, TN. Statistical analysis and interpretation of data: AN, LQ, AM, RG, PA, TN, CM. Contributed to the writing of the manuscript: AM, TN, RG, AN, PV, NE, AF, ES, CM. Reviewed the draft and approved the decision to submit the paper: all authors.

Funding

Data analysis was supported by the CISM. CISM is supported by the Government of Mozambique and the Spanish Agency for International Development (AECID).

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All studies included in this analysis were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and have received ethical approval by The National Bioethics Committee of Mozambique (147/CNBS/08; 80/CNBS/16 and 504/CNBS/18) and the Ethic Committee of the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (Spain). Within the studies, after informing the pregnant women about the study objectives and methods, women consented for their participation, by signing a written informed consent. One copy of the consent form was handled to the participant. The Ministry of Health (MoH) approved the use of data collected through the HIV National Program Registry.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Raquel González and Tacilta Nhampossa contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2023 UNAIDS GLOBAL AIDS UPDATE. 2023. Available from: https://thepath.unaids.org/wp-content/themes/unaids2023/assets/files/2023_report.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 2.UNAIDS. FACT SHEET 2023. 2023. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 3.MISAU. 2023 HIV/AIDS Report. 2023. Available from: https://misau.gov.mz/. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 4.MISAU. Plano Estratégico Nacional de Combate as ITS, HIV e SIDA (PEN ITS/HIV/SIDA) - sector saúde 2004–2008. 2004. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-07/moz-Plano-Estrategico-Nacional-combate-STI-HIV-SIDA.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 5.MISAU. Plano Estratégico Nacional de Resposta ao HIV e SIDA 2021 - 2025 PEN V. 2021. Available from: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/planos-estrategicos-do-hiv. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 6.MISAU. 2021 HIV/AIDS Report. 2021. Available from: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/relatorios-anuais. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 7.Inquérito de Indicadores de Imunização, Malária e HIV/SIDA em Moçambique (IMASIDA) 2015: Relatório de Indicadores Básicos de HIV. Instituto Nacional de Saúde, Instituto Nacional de Estatística de Moçambique. 2017. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/AIS12/AIS12.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 8.Calvert C, Ronsmans C. The contribution of HIV to pregnancy-related mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2013;27(10):1631–9. https://doi.or/10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835fd940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Chilaka VN, Konje JC. HIV in pregnancy - An update. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Jan;256:484–91. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33246666. https://doi.or/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.CDC. CDC Data Confirm: Progress in HIV Prevention Has Stalled. Available from: https://www.hiv.gov/blog/cdc-data-confirm-progress-hiv-prevention-has-stalled. Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

- 11.misau. Acceleration Plan for the Response to HIV/AIDS. Mozambique Ministry of Health. 2013. Available from: http://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/planos-estrategicos-do-hiv. Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

- 12.WHO. WHO. 2013 [cited 2010 Jul 20]. Consolidated Guidelines on The Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating And Preventing HIV infection. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/85321/1/9789241505727_%0Aeng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

- 13.MISAU. Circular Normas Clínicas 08.03.2019 Introdução DTG - COMITÉ TARV No Title. 2019; Available from: https://comitetarvmisau.co.mz/docs/orientacoes_nacionais/Circular_Normas_Clínicas_08_03_19.pdf. Accessed 31 Jan 2024.

- 14.Ahoua L, Arikawa S, Tiendrebeogo T, Lahuerta M, Aly D, Becquet R, et al. Measuring retention in care for HIV-positive pregnant women in Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) option B+ programs: the Mozambique experience. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):322. 10.1186/s12889-020-8406-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuente-Soro L, Fernández-Luis S, López-Varela E, Augusto O, Nhampossa T, Nhacolo A, et al. Community-based progress indicators for prevention of mother-to-child transmission and mortality rates in HIV-exposed children in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 202;21(1):520. 10.1186/s12889-021-10568-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Nhacolo A, Jamisse E, Augusto O, Matsena T, Hunguana A, Mandomando I, et al. Cohort profile update: Manhiça health and demographic surveillance system (HDSS) of the Manhiça health research centre (CISM). Int J Epidemiol. 2021. 10.1093/ije/dyaa218/6102235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Nhampossa T, González R, Nhacolo A, Garcia-Otero L, Quintó L, Mazuze M, et al. Burden, clinical presentation and risk factors of advanced HIV disease in pregnant Mozambican women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):756. 10.1186/s12884-022-05090-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guinovart C, Sigaúque B, Bassat Q, Loscertales MP, Nhampossa T, Acácio S, et al. The epidemiology of severe malaria at Manhiça District Hospital, Mozambique: a retrospective analysis of 20 years of malaria admissions surveillance data. Lancet Glob Heal. 2022;10(6):e873–81. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González R, Munguambe K, Aponte J, Bavo C, Nhalungo D, Macete E, et al. High HIV prevalence in a southern semi-rural area of Mozambique: a community-based survey. HIV Med. 2012;13(10):581–8. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2012.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MISAU. 2022 HIV/AIDS Report. 2022. Available from: https://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/relatorios-anuais. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 21.Lambdin B, Micek M. An assessment of the accuracy and availability of data in electronic patient tracking systems for patients receiving HIV treatment in central Mozambique. BMC Heal Serv. 2012;12(1):30. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MISAU. Introdução de Normas Clinicas Atualizadas e dos Modelos Diferenciados de Serviços, para o seguimento do paciente HIV positivo – CIRCULAR 2. 2019. Available from: https://comitetarvmisau.co.mz/docs/orientacoes_nacionais/Circular_Normas_Clínicas_08_03_19.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 23.MISAU. Tratamento Antiretroviral e Infecções Oportunistas do Adulto, Adolescente, Grávida e Criança. 2016. Available from: http://www.misau.gov.mz/index.php/%0Aguioes#. Accessed 22 Jan 2024.

- 24.MISAU. Circular Normas Clínicas 08.03.2019 Introdução DTG - COMITÉ TARV. 2019; Available from: https://comitetarvmisau.co.mz/docs/orientacoes_nacionais/Circular_Normas_Clínicas_08_03_19.pdf.

- 25.González R, Mombo-Ngoma G, Ouédraogo S, Kakolwa MA, Abdulla S, Accrombessi M, et al. Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy with Mefloquine in HIV-Negative Women: A Multicentre Randomized Controlled Trial. Mofenson LM, editor. PLoS Med. 2014;11(9):e1001733. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Matambisso G, Brokhattingen N, Maculuve S, Cisteró P, Mbeve H, Escoda A, et al. Gravidity and malaria trends interact to modify P. falciparum densities and detectability in pregnancy: a 3-year prospective multi-site observational study. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):396. 10.1186/s12916-022-02597-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.González R, Nhampossa T, Mombo-Ngoma G, Mischlinger J, Esen M, Tchouatieu AM, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in HIV-infected pregnant women: protocol of a multicentre, two-arm, randomised, placebo-controlled, superiority clinical trial (MAMAH. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):e053197. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNICEF. Key Considerations for Introducing New HIV Point-of-Care Diagnostic Technologies in National Health Systems [Internet]. Available from: https://knowledge.unicef.org/diagnostics/resource/key-considerations-introducing-new-hiv-point-care-diagnostic-technologies.

- 29.González R, Augusto OJ, Munguambe K, Pierrat C, Pedro EN, Sacoor C, et al. HIV Incidence and Spatial Clustering in a Rural Area of Southern Mozambique. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e013205. 10.1371/journal.pone.0132053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim AA, Hallett T, Stover J, Gouws E, Musinguzi J, Mureithi PK, et al. Estimating HIV Incidence among Adults in Kenya and Uganda: A Systematic Comparison of Multiple Methods. Boni M, editor. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17535. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017535. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Hallett TB, Stover J, Mishra V, Ghys PD, Gregson S, Boerma T. Estimates of HIV incidence from household-based prevalence surveys. AIDS. 2010;24(1):147–52. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/00002030-201001020-00019. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833062dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Hallett TB, Zaba B, Todd J, Lopman B, Mwita W, Biraro S, et al. Estimating Incidence from Prevalence in Generalised HIV Epidemics: Methods and Validation. Ghys P, editor. PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e80. Available from: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.WHO. NUTRITION LANDSCAPE INFORMATION SYSTEM (NLiS). Available from: https://www.who.int/data/nutrition/nlis/info/anaemia. Accessed 22 May 2024.

- 34.R Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2021. URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- 35.RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. Boston: RStudio, PBC; 2020. Available from: http://www.rstudio.com/. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- 36.WHO. Preventing HIV during pregnancy and breastfeeding in the context of PrEP. 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-HIV-2017.09. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- 37.UNAIDS. Trends in HIV incidence and prevalence: natural course of the epidemic or results of behavioural change?. UNAIDS/99.12E (English original) June 1999, editor. Geneva; 1999. Available from: https://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub04/una99-12_trends-hiv-incidence_en.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- 38.Graybill LA, Kasaro M, Freeborn K, Walker JS, Poole C, Powers KA, et al. Incident HIV among pregnant and breast-feeding women in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2020;34(5):761–76. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000002487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kapoor A, Mussa A, Diseko M, Mayondi G, Mabuta J, Mmalane M, et al. Cross‐sectional trends in HIV prevalence among pregnant women in Botswana: an opportunity for PrEP? J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25(3). 10.1002/jia2.25892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Perez-Hoyos S, Naniche D, Macete E, Aponte J, Sacarlal J, Sigauque B, et al. Stabilization of HIV incidence in women of reproductive age in southern Mozambique. HIV Med. 2011;12(8):500–5. 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.González R, Nhampossa T, Mombo-Ngoma G, Mischlinger J, Esen M, Tchouatieu AM, et al. Safety and efficacy of dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine for intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnant women with HIV from Gabon and Mozambique: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024 Jan; 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00738-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.WHO Recommendations on Antenatal Care for a Positive Pregnancy Experience. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. PMID: 28079998. [PubMed]

- 43.Larson BA, Halim N, Tsikhutsu I, Bii M, Coakley P, Rockers PC. A tool for estimating antiretroviral medication coverage for HIV-infected women during pregnancy (PMTCT-ACT). Glob Heal Res Policy. 2019;4(1):29. 10.1186/s41256-019-0121-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamir Z, Alemu J, Tsegaye A. Anemia among HIV infected individuals taking art with and without zidovudine at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28(1):73. 10.4314/ejhs.v28i1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.