Abstract

Purpose

Chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP) is a costly public health threat that is closely related to mental health. This cross-sectional study aimed to investigate the status and factors related to CMP in young males.

Methods

A total of 126 young males with CMP were randomly sampled between June 20 and October 19, 2023. Demographic information was collected using the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Results

Moderate-to-mild CMP was showed (15.51 ± 10.07). Older age, lower education level, shorter sleeping hours, and more severe CMP were associated with lower mental health. Specifically, hierarchical regression and path analysis revealed that sleeping hours partially mediated the relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health (coefficient = 0.249, p < 0 0.001).

Conclusion

Related risk factors are important for targeted intervention and treatment of CMP. Sleep intervention is conducive to depression and anxiety recovery in individuals with CMP. Based on the results of this study, further measures can be taken to mitigate the negative consequences of CMP on public mental health.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-21424-0.

Keywords: Chronic musculoskeletal pain, Depression, Anxiety, Sleeping hours, Young males

Introduction

Chronic pain is most frequently observed in the musculoskeletal system. Approximately 20–30% of the working adult population experienced chronic musculoskeletal pain (CMP), and the number was increasing [1, 2]. Studies have shown that individuals with CMP would experience reduced work ability, impaired social life, as well as affected mental health problems, which greatly affected the quality of life [3]. Therefore, chronic musculoskeletal pain deserves attention due to its widespread incidence and spread of the condition.

The relationship between CMP and mental health has been widely examined. CMP reported significantly higher symptoms in all the studied mental health issues than individuals without CMP. For example, people with CMP reported significantly more symptoms of anxiety and depression [1, 4]. Furthermore, symptoms of anxiety and depression would increase with an increasing number of pain sites and pain intensity. One study found that improvements in clinical outcomes were associated with increased engagement with digital mental health interventions [5]. In other words, improvements in mental health would conducive to pain relief. To find ways to improve the mental health of CMP, further studies are needed on the treatment and preventive measures for a decline in mental health among individuals with CMP.

CMP also affects sleep quality. Previous results have revealed that CMP itself is a strong predictor of insomnia [6]. A strong association between few hours of sleep and chronic back pain was observed in a population-based cross-sectional study [7]. One study showed that people with CMP have poorer sleep quality and higher levels of insomnia than healthy controls [8]. This significant correlation persisted across occupations [9, 10]. Although studies have confirmed a relationship between sleeping hours and chronic pain, it remained unclear whether there was a relationship between CMP and sleeping hours and mental health. Does improving sleep quality and extending sleep hours improve individuals’ mental health? The present study would focus on these relationships and further explore a feasible path to improve the mental health of individuals with CMP.

According to expert consensus, being older and female are risk factors for CMP [7] and such groups have been extensively studied. Previous epidemiological surveys have shown that elderly and female individuals were two major risk factors; therefore, current research focused more on elderly or female individuals [11]. However, with the expansion of city size, population growth, and changes in the labor market, the incidence rate of chronic musculoskeletal pain among people under 30 years of age was also increasing annually [12]. Second, according to relevant research, the incidence of chronic musculoskeletal pain among men was as high as 29.1%. Therefore, research on young men is of great significance; however, this group of people is often overlooked.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the status and factors related to CMP in young males. Consistent with previous studies on females and older individuals, this study also hypothesized that older age, lower education, shorter sleeping hours, and CMP severity were associated with lower mental health. We also hypothesized that sleeping hours might play an important role in the relationship between CMP levels and mental health. Based on the results of this study, further measures can be taken to mitigate the negative consequences of CMP on public mental health.

Methods

Participants and procedure

A cross-sectional study was conducted to investigate the status and factors related to CMP in young males in Shanghai between June 20 and October 19, 2023. Participants were randomly selected from individuals who had been diagnosed with CMP by a professional physician in the orthopedic Clinic of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) 18–35 years old; (b) located in mainland China; (c) normal speech, comprehension, and expression (no psychological or psychiatric background); (d) suffering pain that occurs in muscles, bones, joints, tendons, or soft tissues for more than three months; and (e) males. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) unwillingness to participate in the investigation; (b) hearing or cognitive impairment or an inability to fill out the questionnaire; (c) having missing values; and (d) spent less than 2 min or more than 30 min answering the questionnaire. G*Power 3.1 was used to estimate the sample size at linear regression analysis in 4 predictors, α = 0.05 and effect size f = 0.25. To achieve a statistical testing power of 0.95, the minimum sample size was showed 129 finally.

After the diagnosis and treatment, an online survey was conducted in Chinese using the Questionnaire Star platform (https://www.wjx.cn). On opening the link to the survey, there was an announcement to clarify the purpose of the study and then all the items for the study for those who volunteered to respond. This aimed to make the participants clear about what private information needed to be provided before they decided to participate. Therefore, all participants were entirely voluntary and informed consent for participation was obtained verbally from the study participants prior to study commencement. After signing the informed consent, participants completed the demographic information, and then completed the other two scales about CMP and mental health by using the Questionnaire Star platform. Some participants were in a hurry because of something, so the doctor asked them to complete two scales first, and then collected their demographic information by telephone. Due to it was a cross-sectional study, the present study complied with reporting guidelines of Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Naval Medical University. All the procedures were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 2013.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics. Demographic information included age, education, BMI, sleeping hours, smoking status, drinking status, and whether they frequently entered an air-conditioned environment. Three questions were asked to investigate their relevant situation, namely, “Did you frequent in air-conditioned environments?” “Did you have a history of smoking?” “Did you have a history of drinking?” They can choose “yes” or “no” to these three questions. As for the question of sleeping hours,

“How many hours per night did you actually sleep in the past month?” was asked and participants were asked to enter a number no larger than 24.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain. Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) [13], an international scale, was used to assess chronic musculoskeletal pain. It was divided into the pain rating index (PRI), present pain intensity (PPI), and visual analog scale (VAS). The sum of the three subscale scores represented the degree of chronic musculoskeletal pain. The higher the score, the more severe the chronic musculoskeletal pain is. The Cronbach’s α in the study was 0.902.

Mental health. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [14] was used to assess mental health. The HADS consists of 14 items, of which seven items assess depression and seven items assess anxiety. All items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3. The average score of the 14 items was calculated to represent the level of mental health, meaning that people with higher scores had higher levels of depression and anxiety. The Cronbach’s α in the study was 0.871.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS version 21.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive and frequency statistics (mean, [deviation] and percentages) were used to describe demographic information and the distribution of chronic musculoskeletal pain sites. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and t-test were used to analyze the effect of demographic information on chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pearson’s correlation was used to identify the relationships between the different factors. Hierarchical regression analysis was used to determine independent variables related to mental health. Finally, mediation analyses were conducted to determine the potential mediating effect of the relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health. p < 0.05 was showed as statistical significance.

Results

Demographic information of participants

After screening, it was received responses from 131 participants. Then, two were deleted because of having missing demographic values, and three were excluded due to spending less than 2 min answering the questionnaire. Therefore, a total of 126 were included finally. Figure S1 showed the flow diagram of the selection process (see Supplementary material).

As illustrated in Table 1, the average age of individuals was 26.49 ± 4.32 years (min = 21, max = 35) and an average BMI was 23.67 ± 2.37 (min = 17.901, max = 30.190). The average sleeping hours of the participants was 6.12 ± 1.15. Most of these participants had completed high school or less (63.5%) level of education and were married (69.8%). There were 84 smokers (66.7%) and 58 drinkers (46%). A total of 102 (81%) participants frequently entered the air-conditioned environment. The distribution of chronic musculoskeletal pain sites was showed in the Supplementary material Figure S2.

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants

| Total(n = 126) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Age(M, SD) | 26.49 | 4.32 | |

| BMI(M, SD) | 23.67 | 2.37 | |

| Sleeping hours(M, SD) | 6.12 | 1.15 | |

| Whether frequently enter air-conditioned environment | |||

| Yes | 102 | 81.00 | |

| No | 24 | 19.00 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 38 | 30.20 | |

| Unmarried | 88 | 69.80 | |

| Education | |||

| High school or less | 80 | 63.50 | |

| Bachelor degree and junior college | 40 | 31.70 | |

| Master degree or above | 6 | 4.80 | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 84 | 66.70 | |

| No | 42 | 33.30 | |

| Drinking | |||

| Yes | 58 | 46.00 | |

| No | 68 | 54.00 | |

Demographic related factors of chronic musculoskeletal pain

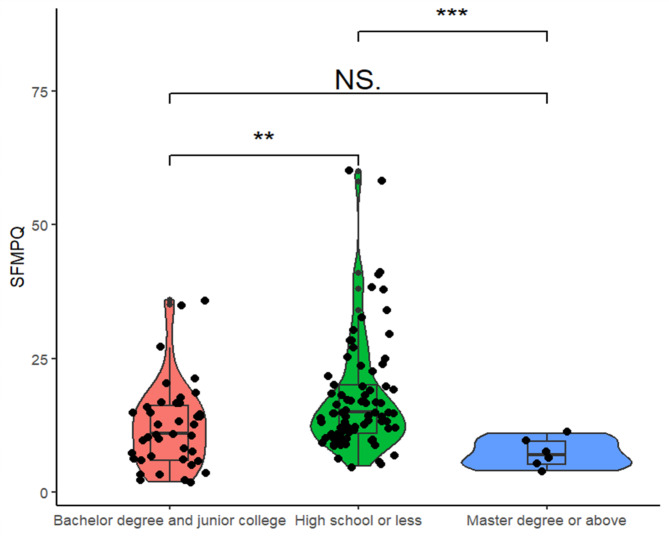

According to the results of t-test (e.g. gender) and F-test, except for education level, no other demographic factors had a significant impact on the SF-MPQ score. Overall, different levels of education had an impact on SF-MPQ scores (F = 6.404, p = 0.002, partial η² = 0.094). According to pairwise testing, there was a significant difference in SF-MPQ scores between individuals with high school or less and bachelor degree and junior college (p = 0.005, 95% CI [1.68, 9.09]) and between individuals with high school or less and master degree or above (p = 0.012, 95% CI [2.29, 18.47]). No significant difference was found between individuals with bachelor degree and junior college and master degree or above. The results were shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The impact of educational level on SF-MPQ score. Note: **p<0.01,***p<0.001

Correlation analysis between different factors

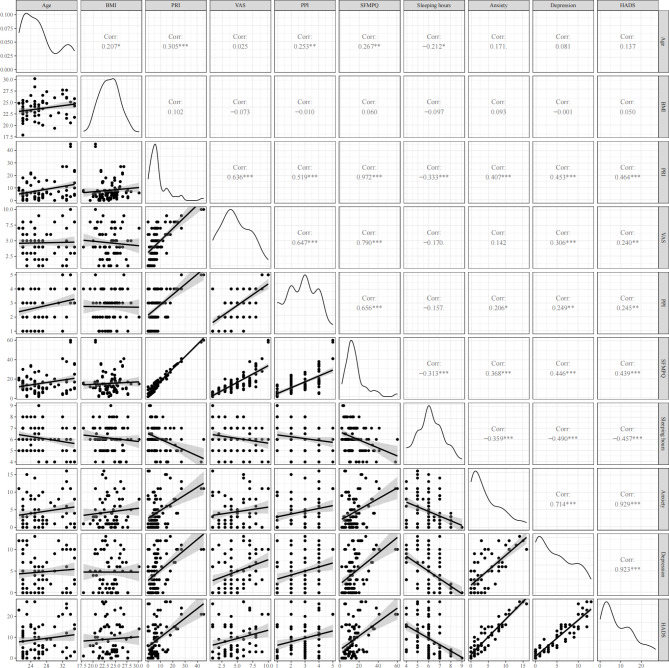

As shown in Fig. 2, Pearson’s correlation analysis revealed that age was significantly correlated with SF-MPQ (r = 0.267, p = 0.002), PPI (r = 0.253, p = 0.004), VAS (r = 0.025, p = 0.785), and PRI (r = 0.305, p = 0.001). Moreover, HADS was significantly correlated with SF-MPQ (r = 0.439, p < 0.001), PPI (r = 0.245, p = 0.006), VAS (r = 0.240, p = 0.007), and PRI (r = 0.464, p < 0.001). Anxiety in HADS was significantly correlated with SF-MPQ (r = 0.368, p < 0.001), PPI (r = 0.407, p < 0.001) and PRI (r = 0.206, p = 0.021). Depression in HADS was significantly correlated with SF-MPQ (r = 0.446, p < 0.001), PPI (r = 0.453, p < 0.001), VAS (r = 0.306, p < 0.001), and PRI (r = 0.249, p = 0.005). Sleeping hours were negatively correlated with SF-MPQ (r = -0.313, p < 0.001) and HADS (r = -0.457, p < 0.001). Therefore, there were significant correlations between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health, indicating the vital role of sleeping hours in the process.

Fig. 2.

Correlation analysis between different factors. Note: ***p<0.001

The predictors of the HADS

To further examine the role of sleeping hours, multivariate linear regression analysis was used. The results of the multivariate linear regression analysis were presented in Table 2. First, age and BMI were added to the model. In the second step, we included the SF-MPQ into the model. Model 1 accounted for 1.9% of the mental health variance. In Model 2, the main effect of the SF-MPQ was significant, which accounted for an additional 17.3% of the variance in the changes of HADS (R2 = 0.193, Adjusted R2 = 0.173, F = 9.735, p < 0.001). SF-MPQ was positively affecting the score of HADS, meaning the value of SF-MPQ increased by 1 standard deviation, and the score of HADS increased by 0.329 standard deviation (B = 0.329, t = 5.128, p < 0.001). In the third step, sleeping hours were included, and 30.7% of the variation in the dependent variable HADS could be explained by sleep hours and CMP (R2 = 0.307, Adjusted R2 = 0.284, F = 13.388, p < 0.001). The SF-MPQ score (B = 0.254, t = 4.091, p < 0.001) positively affected the HADS, indicating the value of SF-MPQ increased by 1 standard deviation, and the score of HADS increased by 0.254 standard deviation. Sleeping hours (B = -2.398, t = -4.454, p < 0.001) negatively affected the HADS, indicating the value of sleeping hours decreased by 1, and the score of HADS increased by 2.398. Given that the absolute value of β of sleep time was greater than that of SF-MPQ score (-0.359 vs. 0.334), the effect of sleep time on HADS was greater than that of SF-MPQ score. The results were consistent even when HADS was divided into anxiety and depression (see Table S1 and S2 in Supplementary materials). Therefore, it was speculated that sleep time maybe play an important role in the relationship between CMP and depression and anxiety.

Table 2.

Regression analyses with HADS as the dependent variable

| Variables | HADS | R Square | Adjusted R Square | R Square Change | F | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | t | |||||||

| Step 1 | |||||||||

| Age | 0.235 | 0.132 | 1.448 | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.019 | 1.208 | 0.302 | |

| BMI | 0.075 | 0.023 | 0.254 | ||||||

| Step 2 | |||||||||

| Age | 0.030 | 0.017 | 0.197 | 0.193 | 0.173 | 0.174 | 9.735 | <0.001*** | |

| BMI | 0.068 | 0.021 | 0.251 | ||||||

| SF-MPQ Score | 0.329 *** | 0.433 | 5.128 | ||||||

| Step 3 | |||||||||

| Age | -0.051 | -0.029 | -0.354 | 0.307 | 0.284 | 0.114 | 13.388 | <0.001*** | |

| BMI | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.017 | ||||||

| SF-MPQ Score | 0.254 *** | 0.334 | 4.091 | ||||||

| Sleeping hours | -2.398 *** | -0.359 | -4.454 | ||||||

NOTE: B = unstandardized beta; β = standardized regression weight.). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001

Note: **p<0.01,***p<0.001

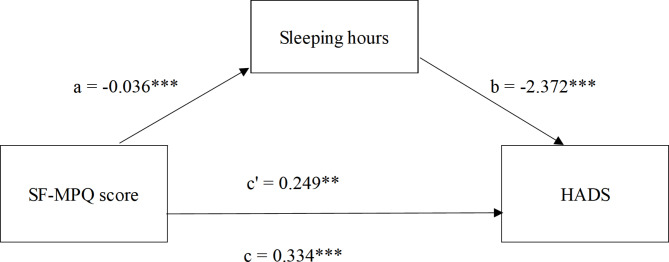

The mediating role of sleeping hours in the relationship of chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health

Hence, multiple mediator analyses were conducted by Process 4.1 in the SPSS 21 package to test the hypothesis that sleeping hours would affect the relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health. The mediating effect was tested with sleeping hours as the mediating variable, SF-MPQ score as the independent variable, and HADS as the dependent variable. Figure 3 showed that sleeping hours was a partial mediator between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health. There were significant direct effects whereby higher SF-MPQ scores were associated with fewer sleeping hours (coefficient = − 0.036, 95% CI [− 0.055, − 0.016], SE = 0.010, t = − 3.664, p < 0.001), and sleeping hours predicted HADS (coefficient = -2.372, 95% CI [-3.417, -1.326], SE = 0.528, t = -4.490, p < 0.001). The direct effect of SF-MPQ scores on HADS was significant (coefficient = 0.249, 95% CI [0.130, 0.369], SE = 0.060, t = 4.143, p = 0.001), showing that people with higher chronic musculoskeletal pain would have more severe mental health problem. The total effect of SF-MPQ scores on HADS was significant (coefficient = 0.334, 95% CI [0.212, 0.455], SE = 0.061, t = 5.434, p < 0.001). There was a significant indirect effect of the SF-MPQ score on HADS through sleeping hours (coefficient = 0.085, bootstrap 95% CI [0.035, 0.153]), and the mediating effect accounts for the total effect of 25.45%. Sleeping hours partially mediated the relationship between chronic musculoskeletal pain and mental health.

Fig. 3.

Sleeping hours mediates the relationship between SF-MPQ score and HADS

Discussion

This cross-sectional study aimed to explore the relationship between CMP and mental health in young males. Moderate-to-mild CMP has been observed in young Chinese males. There was a significant correlation between chronic musculoskeletal pain and HADS, suggesting that individuals with more severe chronic musculoskeletal pain had lower mental health scores. Hierarchical regression revealed that shorter sleeping hours and more severer CMP were predictors for both more depression and anxiety. Further mediation analysis found CMP not only directly leaded to an increase in anxiety and depression, but also affected the mental health of individuals by reducing sleeping time first.

The results of this study indicated that the top two areas with a high incidence of chronic musculoskeletal pain were the lower back and knee, consistent with an epidemiological survey of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Europe [11]. This may be related to the fact that in daily life and work, the lower back and knee joints are more likely to accumulate chronic muscle and joint strain, suggesting timely intervention when pain occurs in the early stages of the lower back and knee joints to avoid accumulating into chronic diseases that affect physical and mental health.

The results indicated that people with lower education levels showed more pain, which was consistent with previous studies [15, 16]. The current study speculated that a lower educational level may be associated with more heavy physical activity. In addition, older age was also a significant risk factor for CMP, which was not only shown in the total score but also in the three dimensions. CMP was a common complaint among older adults and its prevalence has been found to increase with age [6, 17]. However, in the young male cohort, this study also showed that age played an important role in the development of CMP. The related risk factors are important for targeted intervention and treatment of CMP.

Not only significant correlations were observed between CMP and depression and anxiety, but also the degree of CMP could predict the level of depression and anxiety. This was consistent with previous research that showed CMP had a negative impact on mental health. This is understandable because anxiety and depression are often accompanied by pain. In a nationally representative sample, McWilliams et al. found that anxiety disorder was present in 35% of individuals with chronic pain versus 18% of the general population [18]. The number of pain locations could significantly predict anxiety and depression [1]. One study included 189 participants with CMP, revealing the influence of pain on daily activities and the number of pain locations significantly predicted the levels of depression [19]. A person’s perception of pain may be enhanced in the context of depression and anxiety. For example, Picavet et al. found that kinesophobia, or fear of exacerbating pain through exercise, predicted more severe pain and disability in patients with chronic low back pain [20]. Therefore, from this point of view, timely intervention in the mental health of CMP individuals, not only for psychological improvement but also for pain recovery, is of great help.

Sleep hours was an influential and predictor of anxiety and depression in the individuals with CMP. The negative relationship between sleep and CMP has been demonstrated in previous studies [9, 21]. A systematic review with meta-analysis across 6 databases identified prospective longitudinal cohort studies in adults examining the relationship between sleep problems/disorders and chronic musculoskeletal pain, finding CMP at baseline may increase the risk of short-term sleep problems [22], which was also consistent with the results of this study. In addition, it further found that CMP affecting anxiety and depression was through sleeping. Individuals with CMP may have high anxiety and depression scores. It was proposed that in this process, the pain first affected the individuals’ sleeping, and then the lack of sleeping leaded to the increase of anxiety and depression. Given the mediating role of sleeping hours, interventions targeting them would contribute to mental health improvement in individuals with CMP. This finding was consistent with the results of previous studies. The clinically significant levels of depression and anxiety in insomnia patients were 10 and 17 times higher, respectively, than in non-insomnia people [23]. One meta-analysis which included 65 trials comprising 72 sleeping interventions led to a significant medium-sized effect on depression (g+ = −0.63) and anxiety (g+ = −0.51) [24]. In addition to depression and anxiety, lack of sleep has been linked to other mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress, eating disorders, delusions, and hallucinations etc [25–27]. Therefore, the current study speculated that sleep intervention was a feasible method conducive to the recovery of depression and anxiety in individuals with CMP. However, this needs to be validated in future intervention studies.

Limitations

Although certain results existed, some limitations still needed to be discussed. First, the information working background was not collected. The current study found lower education levels showed more CMP and speculated that lower educational level may be associated with more heavy physical activity. Considering the closely relationship between working and CMP, the addition of relevant information could support above result. Second, this was a cross-sectional study and no causal relationship could be drawn between the variables of concern. To further understand the relationship between CMP, mental health, and sleep, multi-time, longitudinal and experimental studies are necessary. For example, changes in anxiety and depression in CMP patients were observed by manipulating sleep time in different control groups. Last but not least, mental health covered a broad spectrum, but only depression and anxiety by using HADS were tested in the present study. Although anxiety and depression were major components of mental health, they were not fully representative. Future studies should include more psychological variables to explore, such as mental resilience and social support etc.

Conclusion

Chronic musculoskeletal pain lasts for a long time and has a high incidence, which can have a negative impact on individual mental health. This study explored the relationship between CMP and depression and anxiety in young males. Moderate-to-mild CMP was presented. Older age, lower education, shorter sleeping hours, and more severer CMP were risk factors for both more depression and anxiety. In term of influencing path, CMP may first affected individuals’ sleeping, and then leaded to bad mood. Interventions targeting sleep have the potential to be a good way to regulate the depression and anxiety of individuals with chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the volunteers who participated in the study.

Abbreviations

- CMP

Chronic musculoskeletal pain

- SF-MPQ

Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire

- HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- PRI

Pain rating index

- PPI

Present pain intensity

- VAS

Visual analog scale

Author contributions

HZ and ZY contributed to the writing of this article and are the co-first authors. TL contributed to the data collection and article revised. YS and YT carried out the preliminary data processing and correction when the paper was revised. YJ, SY led the whole study, including putting this study forward and carrying out the study; and ZW completed revision review comments; they are the co-corresponding authors. All authors approved the final version to be published.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Youth Talent Program in Faculty of Psychology and Mental Health of Navy Medical University (2023RC001); The incubation base project for students’ innovative practical ability of Naval Medical University (FH2025444).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study which cannot be shared for ethical, privacy, or security concerns are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participants were entirely voluntary and informed consent for participation was obtained verbally from the study participants prior to study commencement. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Naval Medical University.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for the publication.

Conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Huipeng Zhou, Zhishi Yang and Ling Tang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yeye Sha, Email: shayeye0323@163.com.

Zhiwei Wang, Email: Shwangzhiwei@vip.sina.com.

Yanpu Jia, Email: JYP6631@163.com.

References

- 1.Garnæs KK, Mørkved S, Tønne T, Furan L, Vasseljen O, Johannessen HH. Mental health among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and its relation to number of pain sites and pain intensity, a cross-sectional study among primary health care patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23(1):1115. 10.1186/s12891-022-06051-9. Published 2022 Dec 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steingrímsdóttir ÓA, Landmark T, Macfarlane GJ, Nielsen CS. Defining chronic pain in epidemiological studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2017;158(11):2092–107. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Falla D. Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53(9):554–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Björnsdóttir SV, Jónsson SH, Valdimarsdóttir UA. Mental health indicators and quality of life among individuals with musculoskeletal chronic pain: a nationwide study in Iceland. Scand J Rheumatol. 2014;43(5):419–23. 10.3109/03009742.2014.881549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng AL, Agarwal M, Armbrecht MA, Abraham J, Calfee RP, Goss CW. Behavioral mechanisms that Mediate Mental and Physical Health Improvements in People with Chronic Pain who receive a Digital Health Intervention: prospective cohort pilot study. JMIR Form Res. 2023;7:e51422. 10.2196/51422. Published 2023 Nov 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sit RWS, Yip BHK, Wang B, Chan DCC, Zhang D, Wong SYS. Chronic musculoskeletal pain prospectively predicts insomnia in older people, not moderated by age, gender or co-morbid illnesses. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1593. Published 2021 Jan 15. 10.1038/s41598-021-81390-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Saes-Silva E, Vieira YP, Saes MO, et al. Epidemiology of chronic back pain among adults and elderly from Southern Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Braz J Phys Ther. 2021;25(3):344–51. 10.1016/j.bjpt.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Water AT, Eadie J, Hurley DA. Investigation of sleep disturbance in chronic low back pain: an age- and gender-matched case-control study over a 7-night period. Man Ther. 2011;16(6):550–6. 10.1016/j.math.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ando H, Ikegami K, Sugano R, et al. Relationships between Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain and Working hours and sleeping hours: a cross-sectional study. J UOEH. 2019;41(1):25–33. 10.7888/juoeh.41.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin WS, Chen YC, Lin TT, Guo YL, Shiao JSC. Short sleep and chronic neck and shoulder discomfort in nurses. J Occup Health. 2021;63(1):e12236. 10.1002/1348-9585.12236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cimas M, Ayala A, Sanz B, Agulló-Tomás MS, Escobar A, Forjaz MJ. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in European older adults: cross-national and gender differences. Eur J Pain. 2018;22(2):333–45. 10.1002/ejp.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Paniz VM, Silva MC, Wegman DH. Increase of chronic low back pain prevalence in a medium-sized city of southern Brazil. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:155. Published 2013 May 1. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Lovejoy, Travis I, et al. Evaluation of the Psychometric properties of the revised short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. J Pain. 2012;13(12):1250–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smarr KL, Autumn L. Keefer. Measures of Depression and depressive symptoms: Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI‐II), Center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale (CES‐D), geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), hospital anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Patient Health Questionnaire‐9 (PHQ‐9). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(S11):S454–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergman S, Herrström P, Högström K, Petersson IF, Svensson B, Jacobsson LT. Chronic musculoskeletal pain, prevalence rates, and sociodemographic associations in a Swedish population study. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(6):1369–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimmino MA, Ferrone C, Cutolo M. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):173–83. 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duke Han S, Buchman AS, Arfanakis K, Fleischman DA, Bennett DA. Functional connectivity networks associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain in old age. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(8):858–67. 10.1002/gps.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Mood and anxiety disorders associated with chronic pain: an examination in a nationally representative sample. Pain. 2003;106(1–2):127–33. 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00301-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gunnarsson H, Safipour J, Elmqvist C, Lindqvist G. Different pain variables could independently predict anxiety and depression in subjects with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Scand J Pain. 2021;21(2):274–82. 10.1515/sjpain-2020-0129. Published 2021 Jan 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JW, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia: predictors of chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(11):1028–34. 10.1093/aje/kwf136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malmborg JS, Bremander A, Olsson MC, Bergman AC, Brorsson AS, Bergman S. Worse health status, sleeping problems, and anxiety in 16-year-old students are associated with chronic musculoskeletal pain at three-year follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1565. 10.1186/s12889-019-7955-y. Published 2019 Nov 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Runge N, Ahmed I, Saueressig T, et al. The bidirectional relationship between sleep problems and chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain. 2024;165(11):2455–67. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000003279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor DJ, Lichstein KL, Durrence HH, Reidel BW, Bush AJ. Epidemiology of insomnia, depression, and anxiety. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1457–64. 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott AJ, Webb TL, Martyn-St James M, Rowse G, Weich S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;60:101556. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allison KC, Spaeth A, Hopkins CM. Sleep and eating disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(10):92. 10.1007/s11920-016-0728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maher AR, Apaydin EA, Hilton L, et al. Sleep management in posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2021;87:203–19. 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharafkhaneh A, Giray N, Richardson P, Young T, Hirshkowitz M. Association of psychiatric disorders and sleep apnea in a large cohort. Sleep. 2005;28(11):1405–11. 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study which cannot be shared for ethical, privacy, or security concerns are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.