Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2) is synthesised by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1 (mPGES-1). PGE-2 exhibits pro-inflammatory properties in inflammatory conditions. However, there remains limited understanding of the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 pathway in Angiostrongylus cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis. This study revealed several key findings regarding the activation of the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 pathway and its correlation with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis induced by A. cantonensis infection. Immunostaining revealed an increase in the expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the subarachnoid space and glial cells compared to control subjects. Inhibition of the NLRP3 inflammasome by small interfering RNA (siRNA) blocked extracellular secretory proteins (ESPs) stimulated COX-2, mPGES-1 and PGE-2 in microglia. MCC950, an NLRP3 inhibitor, inhibited the levels of the COX-2, mPGES-1, and PGE-2 proteins induced by A. cantonensis in mice. Treatment of mice infected with A. cantonensis with the COX-2 inhibitor NS398 significantly reduced the levels of mPGES-1, PGE-2, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) levels. Similarly, the mPGES-1 inhibitor MF63 significantly reduced PGE-2 and MMP-9 levels in A. cantonensis-infected mice. Administration of MCC950, NS398, or MF63 resulted in marked attenuation of blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability and eosinophil counts in A. cantonensis-infected mice. These findings highlight the critical role of the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 pathway and its regulation by the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis induced by A. cantonensis infection. Furthermore, pharmacological interventions targeting this pathway, such as MCC950, NS398, and MF63, show promising therapeutic potential in mitigating associated inflammatory responses and disruption of the BBB. The results indicate that blocking NLRP3 using pharmacological (MCC950) and gene silencing (siNLRP3) methods emphasised the crucial involvement of NLRP3 in the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 pathway. This suggests that the activation of the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 axis in response to A. cantonensis infection may be mediated through a mechanism involving the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00436-025-08454-8.

Keywords: Angiostrongylus cantonensis, Cyclooxygenase-2, Inflammasome, Meningoencephalitis, Prostaglandin E2

Introduction

Neuroangiostrongyliasis, caused by infection with the rat lungworm Angiostrongylus cantonensis, is the leading cause of human eosinophilic meningoencephalitis worldwide (Jarvi and Prociv 2021). Humans, as accidental hosts, acquire the infection by ingesting raw or undercooked snail meat, various paratenic hosts harboring third-stage larvae, or green vegetables contaminated with infective larvae (Wang et al. 2008). The migration of larvae to brain tissue causes severe damage to the central nervous system (CNS), potentially leading to coma and death (Graeff-Teixeira et al. 2009). Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) contributes to blood-cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier and blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption in a murine model of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by A. cantonensis infection (Chiu and Lai 2013, 2014). In response to infection, signaling cascades produce pro-inflammatory mediators, triggering an exacerbated immune response. Another inflammatory pathway involves the activation of inflammasomes (Generoso et al. 2024). Studies have highlighted the role of the NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome in CNS disorders commonly associated with neuroinflammation. Parasite infections can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, as observed in toxoplasmosis (Gorfu et al. 2014) and angiostrongyliasis meningoencephalitis (Lam et al. 2020). Once the NLRP3 inflammasome is activated, it completes the assembly of the inflammasome including the sensor NLRP3, the adaptor apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC), and the effector caspase-1, leading to caspase-1 activation and increased release of downstream inflammatory cytokines, as well as to pyroptosis (Zhang et al. 2024). Remarkably, dysregulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome extends beyond the CNS boundaries and permeates into the enteric and peripheral immune systems, thereby altering the microbiota-gut-brain axis. The integrity of the BBB and intestinal epithelial barrier is also compromised by this inflammation (Ghaffaripour Jahromi et al. 2024). NLRP3 inflammasome-derived IL-1β plays a protective role in stress-induced gastric injury via activation of the COX-2/PGE2 axis (Higashimori et al. 2021).

In a neurological disease, excess prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2) is known to be produced at the sites of brain lesion and contributes to the progression of symptoms (Andreasson 2010). PGE-2 is derived from membrane phospholipids through three sequential enzymatic processes; phospholipase A2, which releases arachidonic acid from membrane phospholipids, cyclooxygenase (COX) that converts arachidonic acid to PGH-2, and microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1) that isomerises PGH-2 to PGE-2 (Ikeda-Matsuo 2017). COX-2 has been implicated in a neurotoxic role across various models of inflammatory brain diseases. Genetic disruption and chemical inhibition of COX-2 have consistently led to reductions in PGE-2 levels and improvements in symptoms, suggesting that PGE-2 produced by COX-2 may contribute to the progression of brain inflammation (Yagami et al. 2016; Ikeda-Matsuo 2017). These findings strongly indicate that inflammatory mechanisms are pivotal in the upregulation of COX-2. Furthermore, the NLRP3 inflammasome has been identified as a key regulator upstream in this process, facilitating the activation of COX-2 (Zhang et al. 2022).

Angiostrongyliasis meningoencephalitis is associated with increased breakdown of the BBB and brain injury (Chiu and Lai 2014). The COX-2 inhibitor reduces BBB damage and leukocyte infiltration after focal cerebral ischemia (Candelario-Jalil et al. 2007). Additionally, inhibition of PGE-2 by genetic disruption or pharmacological inhibition of COX-2 may contribute to neuroprotective effects. Therefore, to elucidate the role of PGE-2, studies of mPGES-1, the terminal enzyme for the synthesis of PGE-2, have recently become an active area of research in brain inflammatory conditions. In the present study, our aim was to investigate the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome after A. cantonensis infection and the therapeutic effect of MCC950 on the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 pathway in angiostrongyliasis meningoencephalitis. We hypothesised that the NLRP3 inhibitor can reduce the activation of COX-2 and mPGES-1, which in turn leads to a reduction in PGE-2 and an improvement in symptoms of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

A total of 60 BALB/c male mice were used in the experiment, procured from the National Laboratory Animal Centre, Taipei, Taiwan. All mice were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle photoperiod and raised until they reached 5 weeks of age, weighing between 20 and 25 g. The mice were provided Purina Laboratory food and water ad libitum. They were housed in a specific pathogen-free room at the Animal Centre, Chung-Shan Medical University (Taichung, Taiwan), for more than a week prior to the start of the experimental infection (Chiu and Lai 2013). Throughout the experiment, mice were monitored daily for access to food, water, bedding and overall health conditions. Following infection with A. cantonensis, mice were closely observed for signs of disease, such as ruffled fur, decreased activity or tachypnea, as well as any weight loss. In particular, no mortality was recorded among mice during the infection and subsequent drug treatment phases. To ensure humane euthanasia, mice were subjected to CO2 exposure until respiratory arrest occurred, followed by cervical dislocation as a confirmatory euthanasia method before necropsy. This study was carried out with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chung-Shan Medical University, and all procedures were carried out in accordance with institutional guidelines for animal experiments. Affidavit of approval of animal use protocol Chung-Shan Medical University experiment animal center approval No. 2804.

Antibodies

Below are the antibodies and manufacturing company numbers used in this study. Goat anti-mouse COX-2 polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-1746, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-mouse polyclonal mPGES-1 (abcam, # ab62050, Cambridge, UK). Rabbit anti- mouse PGE-2 polyclonal antibody (abcam, #ab2318, Cambridge, UK). Rabbit anti-mouse NLRP3 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, #15,101, Danvers, MA, USA). Mouse anti-mouse β-actin monoclonal antibody (Sigma, #A2228, St. Louis, MO, USA). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (abcam, #ab6721, Cambridge, UK). HRP-conjugated anti-goat IgG (abcam, #ab6741, Cambridge, UK). HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (abcam, #ab205719, Cambridge, UK).

Larval preparation

Infectious larvae (third stage, L3) of A. cantonensis were obtained from Achatina fulica snails, which had been bred for several months and infected with larvae of A. cantonensis through rat hosts at the Wufeng Experimental Farm (Taichung, Taiwan). L3 larvae were retrieved from tissues using a method previously outlined but with several adjustments (Chen et al. 2022). The nail shells were crushed and tissues were homogenized in a pepsin-HCl solution (pH 1 to 2, 500 IU of pepsin/g of tissue) and digested by agitation at 37° C for 2 h. The L3 larvae in the sediment were collected by sequential washes with double distilled water and enumerated under a microscope.

Animal infection

A total of 18 BALB/c male mice were randomly distributed into 5 experimental groups, labelled D5, D10, D15, D20, and D25, each consisting of 3 mice, together with a control group of 3 mice. Before infection, mice were deprived of food and water for 12 h. Mice in groups D5, D10, D15, D20 and D25 were orally inoculated with 30 larvae of A. cantonensis and subsequently sacrificed on days 5, 10, 15, 20, or 25 after inoculation (PI), respectively. The control group mice received water only and were sacrificed on day 25 PI. Following sacrifice, the brains were immediately extracted and frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analysis.

Treatment of animals

A total of 42 mice were randomly allocated into six groups, each group consisting of 7 mice. Before infection, food and water were held for 12 h. The uninfected control mice received oral administration of distilled water only on Day 10 post-inoculation (PI). All other groups, including untreated infected control mice, were infected with 30 A. cantonensis larvae and intraperitoneal injection with distilled water only on day 10 PI. The treatment groups were intraperitoneal injection with DMSO alone (10 mg/kg/day, Sigma-Aldrich, #34,869, St. Louis, MO, USA), MCC950 alone (10 mg/kg/day, Sigma-Aldrich, #5,381,200,001, St. Louis, MO, USA), NS398 (10 mg/kg/day, Sigma Aldrich, #349,254, Saint Louis, MO, USA) and MF63 (30 mg/kg/day, Cayman Chemical, #CAS 892549-43-8, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) for 7 consecutive days, starting on day 10 PI. Subsequently, all mice were sacrificed 22 days after inoculation for further analysis.

Preparation of excretory and secretory products (ESPs)

Third-stage infectious larvae of A. cantonensis were acquired from A. fulica snails following the method described by Chen et al. (2022). These larvae were used to infect mice and the fifth stage larvae of A. cantonensis was harvested from mouse brains 20 days after infection. Subsequently, the harvested worms were washed thoroughly to eliminate host cells. A total of 200 intracranial larvae were suspended in 400 ml of sterile water. The larvae were then mechanically disrupted using a clear glass pestle and subjected to sonication on ice (75 W for 10 s, repeated 10 times, with 2-min intervals) three times to facilitate the release of soluble antigens. After sonication, the samples were centrifuged at 11,500 g for 5 min at 4° C and the resulting supernatant was collected. This supernatant was further filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. The total protein concentration in the filtrate was determined using the bicinchoninic acid method and the ESPs were stored at − 80 °C until further use.

Cell culture and stimulation assay

The mouse microglial cell line N9, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (#CVCL-0452), was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, #11,875,093, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (Gibco, #10,100,147, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and maintained at 37° C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates (Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. Once a monolayer was formed, the cells were stimulated with 50 µg/ml of ESPs as an infected group. The negative control group received an equal volume of liquid, prepared using the ESPs extraction procedure, but without culturing A. cantonensis.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

siRNA transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (11,668,027, Life Technologies, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were transfected with targeted siRNA or scrambled siRNA (20 pM) mixed with 6 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 diluted in 150 μl of reduced serum medium (Life Technologies, #31,985,062, CA, USA). The resulting siRNA-lipid complexes were added to cells, incubated for 6 h, and then the medium was replaced and maintained for an additional 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with cocaine (10 μM) or left untreated, and harvested after an additional 24 h as previously described (Chivero et al. 2021). The knockdown efficiencies were evaluated by Western blotting.

Collection of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)

A single CSF sample was collected from the magna cisterna for ELISA and zymography assays. Mice were anaesthetised by intraperitoneal injection of urethane (1.25 g/kg). Each mouse was placed in a stationary apparatus at a 135° angle with respect to the head and body. The skin over the neck area was shaved and cleaned three times with 70% ethanol. Subsequently, the subcutaneous tissue and muscles were carefully separated. A capillary tube was then inserted through the dura mater into the cisterna magna and CSF was aspirated into the capillary tube following established procedures (Chiu and Lai 2014). The collected CSF was transferred to a 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube and centrifuged at 3000 × g at 4° C for 5 min. The resulting supernatant was carefully collected in another 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube and stored in a freezer at − 80 °C until further analysis.

Western blot analysis

Electrophoresis, coupled with subsequent Western blot analysis, stands as an essential methodology for probing protein alterations within cerebrum tissues. Initially, cerebrum tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min to remove debris. Subsequently, protein concentrations (30 µg) in the supernatant were determined using protein assay kits (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), using bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA) as standard. These proteins were then diluted 1:1 in a loading buffer composed of 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 5% bromophenol blue, 2% glycerol, 2-mercaptoethanol, and 0.5 M Tris–HCl (pH 6.8). Subsequently, the sample mixtures were boiled for 5 min before 10% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed at room temperature and 110 V for 90 min, followed by electrotransfer to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (PVDF) (Pall Corporation, Coral Gables, FL, USA) at a constant current of 30 V and at 4° C overnight. Following electrotransfer, PVDF membranes were subjected to two 10-min washes in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-T) at room temperature, repeating this process three times. The membrane surface was then blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk in PBS at 37° C for 1 h, followed by three saturations with PBS-T for 10 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted at 1:1000 at 37° C for 1 h. After incubation, PVDF membranes were washed three times with PBS-T before being incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted at 1:10,000 at 37° C for 1 h, facilitating the detection of bound primary antibodies. Finally, the labelled proteins were visualised utilizing an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK), and the densities of specific immunoreactive bands were quantified using a computer-assisted imaging densitometer system.

Immuno-histochemistry

The mouse cerebrum was individual fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin for a duration of 24 h. After fixation, the specimens were subjected to dehydration through a series of graded ethanol (50%, 75%, 100%) and xylene, eventually was embedded in paraffin at 55 °C for 24 h. For immunohistochemical purposes, relatively thick (10 μm) serial sections of the paraffin-embedded brains were meticulously cut and mounted onto glass slides. These sections were then dewaxed with xylene and rehydrated using a series of ethanol solutions (100%, 95% and 75%) for 5 min each. Subsequently, they were treated with 3% H2O2 in methanol for 10 min to deactivate any endogenous peroxidase activity, followed by three 5-min washes with PBS. Subsequently, the sections were blocked with 3% BSA at room temperature for 1 h, before being incubated with primary antibodies at a 1:50 dilution in 1% BSA at 37° C for 1 h. After another round of three washes in PBS, the sections were exposed to HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, USA) at a 1:100 dilution in 1% BSA at 37 °C for 1 h, followed by three additional washes in PBS. Finally, sections were incubated for 3 min at room temperature with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (0.3 mg/ml) in 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5) containing 0.3 μl/ml H2O2. After this incubation, the sections were subjected to a final round of three washes in PBS before being mounted in 50% glycerol in PBS for examination under a light microscope. Th images were analyzed using Image J 1.54 g software (Bethesda, MD, USA).

Gelatin zymography

The procedures were performed based on zymography utilizing gelatin-containing SDS polyacrylamide gels, as previously detailed (Chen et al. 2017). Unboiled protein samples (30 µg) were mixed with an equal volume of standard loading buffer before loading. The samples were loaded onto polyacrylamide gels at a concentration of 7.5% (mass/volume), which included copolymerised substrate gelatin (0.1%) for SDS-PAGE (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO, USA) to evaluate gelatinase activities. SDS-PAGE was carried out in a running buffer (1% SDS, 25 mM Tris, and 250 mM glycine) at room temperature and 110 V for 1 h. Subsequent to electrophoresis, each gel was washed for two 30-min in denaturing buffer (2.5% Triton X-100) at room temperature, followed by two washes with double distilled water at room temperature for 10 min each. The gel was then incubated in a reaction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5; containing 0.02% Brij-35, 0.01% NaN3 and 10 mM CaCl2) at 37 °C for 18 h. After incubation, the gel was stained with 0.25% Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for 1 h and destained using a solution comprising 15% methanol and 7.5% acetic acid. The resulting gel displayed a uniform background, except in regions where gelatinases had migrated and cleaved their respective substrates. Quantitative analysis of gelatinases was performed using a computer-assisted imaging densitometer system (UN-SCAN-ITTM gel Version 5.1, Silk Scientific, Provo, Utah, USA).

Evaluation of BBB permeability

BBB permeability was evaluated by measuring Evans blue concentrations in the mouse cerebrum, following the methodology outlined by Chen et al. (2019). Initially, mice received an injection of Evans blue dye (5 ml/kg body weight; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in saline via the tail vein. After a 2-h circulation period, mice were anaesthetised and subjected to transcardial perfusion with saline to eliminate intravascular dye. The mouse cerebrum was weighed and homogenised in a 50% trichloroacetic acid solution. The resulting homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min and the supernatants were carefully collected. Each supernatant was then subjected to absorbance measurement at 620 nm using a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U3000, Tokyo, Japan) to quantify Evans Blue concentrations.

Eosinophil counts in the CSF

The CSF was collected and placed in a centrifuge, spinning at 400 × g for 10 min. The resulting sediments were then gently mixed with 2 ml of acetic acid and 100 ml of Unopette buffer (Vacutainer System, Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The eosinophils were identified using the Unopette stained system. A hemocytometer cell counting chamber (Paul Marienfeld, Lauda-Koenigshofen, Germany) was used to count eosinophils in the sample under a microscope.

Statistical analysis

Differences among the various groups of mice were evaluated using Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric analysis followed by Dunn multiple comparison tests. All results were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was considered for P values < 0.05.

Results

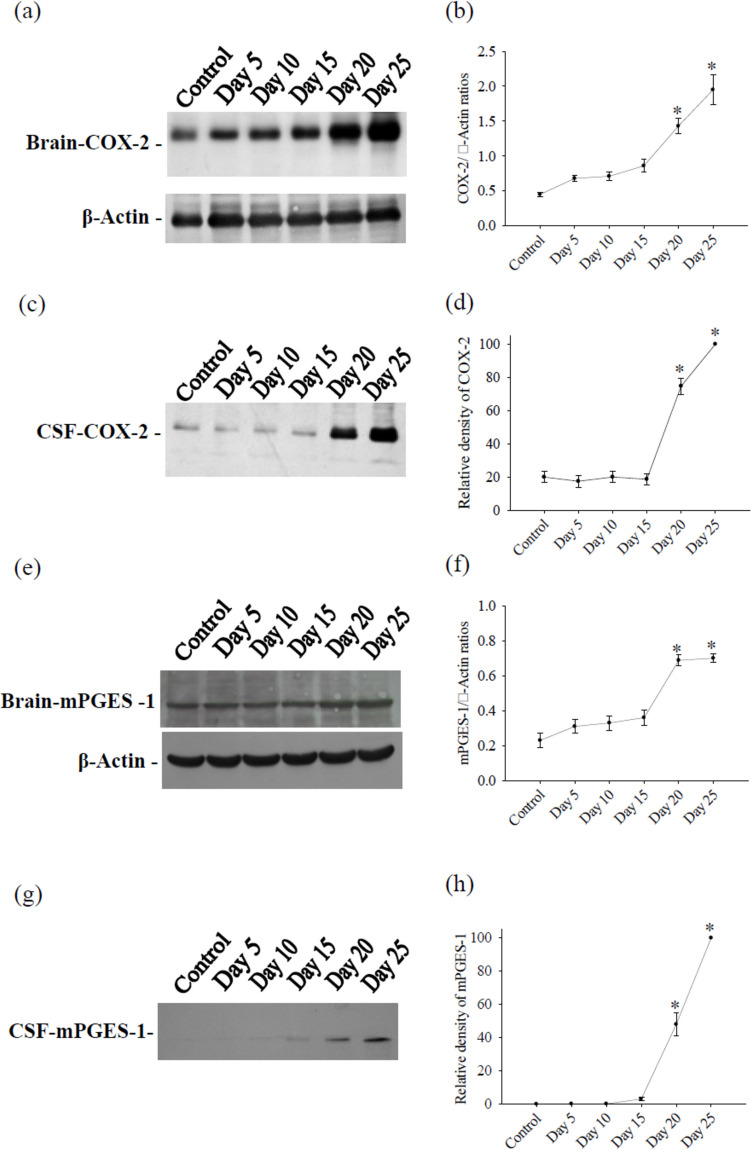

COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the mouse cerebrum and CSF

The results of the Western blot revealed weak expression of COX-2 in both the cerebrum and the CSF of control mice. However, after infection with A. cantonensis, protein levels of COX-2 significantly increased on days 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 in the cerebrum. In the CSF, COX-2 showed a significant elevation on days 20 and 25 after infection. Furthermore, mPGES-1 protein levels showed a significant increase on days 20 and 25 after infection with A. cantonensis. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of COX-2 and mPGES-1 from mouse cerebrum and CSF. Protein bands were detected using specific antibodies for cerebrum COX-2 a, CSF COX-2 c, cerebrum mPGES-1 e and CSF mPGES-1 g. Protein levels was performed using computer-assisted imaging densitometry b, d, f, h, with β-actin serving as loading control in cerebrum. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were indicated by *

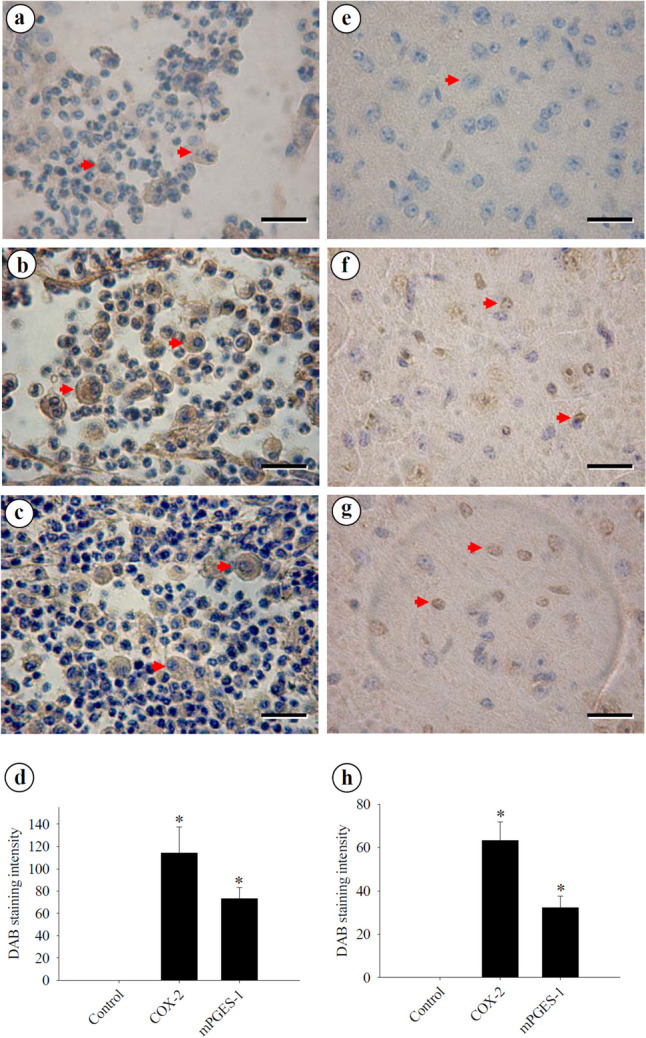

Immunohistochemical localization of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in mouse brain

Weak signals for the infiltration of leukocytes in the subarachnoid space were detected when using normal serum as control (Fig. 2a). However, strong positive signals for COX-2 (Fig. 2b) and mPGES-1 (Fig. 2c) were observed in these infiltrating leukocytes. The quantification of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in leukocytes was significantly increased compared to the control (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, no signals were detected in the brain cells of mice when using normal serum (Fig. 2e). However, strong positive signals for COX-2 (Fig. 2f) and mPGES-1 (Fig. 2g) were observed in glial cells. Quantification of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in glial cells was significantly increased compared to the control (Fig. 2h).

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical distribution of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the mouse cerebrum. Immunohistochemistry staining is a powerful technique used to detect COX-2 and mPGES-1 antigen expression in cells within brain tissue sections. a Weak signals were detected in infiltrating macrophages (arrowheads) within the subarachnoid space when normal serum was used. b Strong positive signals for COX-2 were observed in infiltrating macrophages (arrowheads) within the subarachnoid space. c Strong positive signals for mPGES-1 were detected in infiltrating macrophages (arrowheads) within the subarachnoid space. Macrophages are large cells, typically round or oval in shape, with a large, kidney-shaped or oval nucleus. d Quantification of COX-2 b and PGES-1 c in leukocytes within the subarachnoid space. e No signal was detected in brain cells (arrowhead) of the mouse when normal serum was used. f Strong positive signals for COX-2 were observed in glial cells (arrowheads). g Strong positive signals for mPGES-1 were detected in glial cells (arrowheads). h Quantification of COX-2 e and PGES-1 f in glial cells in the brain tissue. Th images were analyzed using Image J 1.54 g software. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Bar scales = 40 μm

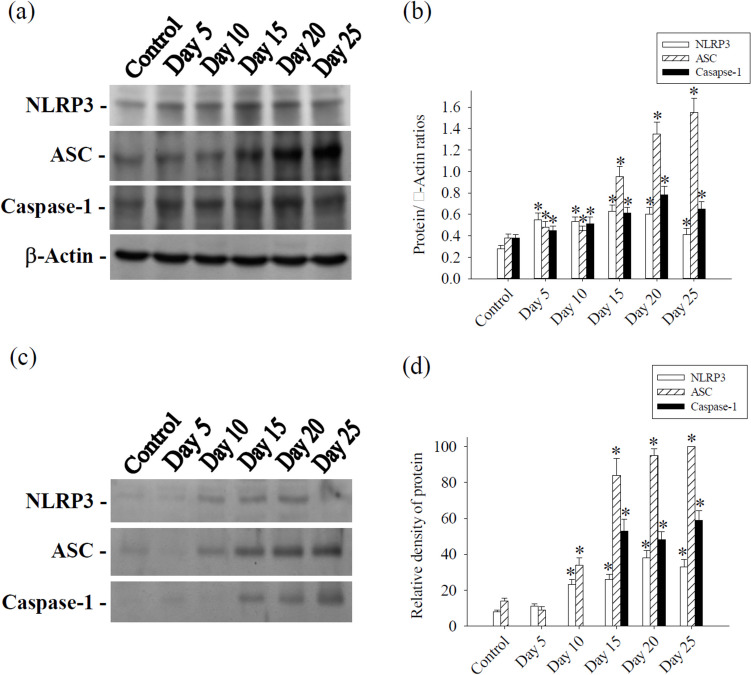

NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 in mouse cerebrum and CSF

In the cerebrum, protein levels of NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 significantly increased on days 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 following infection with A. cantonensis. In the CSF, NLRP3 and ASC protein levels showed a significant rise on days 10, 15, 20 and 25 after A. cantonensis infection. Caspase-1 protein levels exhibited significant increases on days 15, 20 and 25 post-infection. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of NLRP3, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) and caspase-1 from mouse cerebrum and CSF. a Protein bands were detected using specific antibodies for NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 from cerebrum. β-actin serving as loading control. c Protein bands of NLRP3, ASC and caspase-1 were detected from CSF. Protein levels were performed using computer-assisted imaging densitometry b, d. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were indicated by *

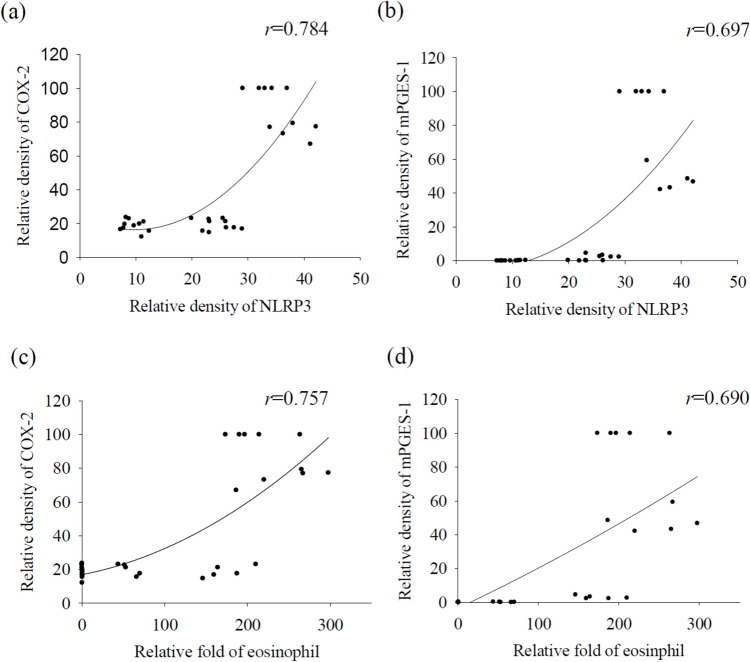

Correlation of NLRP3 and eosinophil count with COX-2 and mPGES-1

NLRP3 and eosinophilia in CSF were observed exclusively in infected BALB/c mice, with no instances in uninfected mice. A correlation analysis was performed to assess the relationship of NLRP3 and eosinophil count with the level of COX-2 and mPGES-1 proteins in A. cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. The results indicated a significant correlation between NLRP3 and the densities of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the CSF, determined by the Spearman rank correlation test (Fig. 4a, b). Similarly, a significant correlation was observed between the eosinophil count and the densities of both COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the CSF. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of NLRP3 and eosinophil count with COX-2 and mPGES-1. NLRP3 in the CSF showed significant correlations with the densities of COX-2 a and mPGES-1 b. The eosinophil count in the CSF showed significant correlations with the densities of COX-2 c and mPGES-1 d, determined by Spearman’s rank correlation test. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment

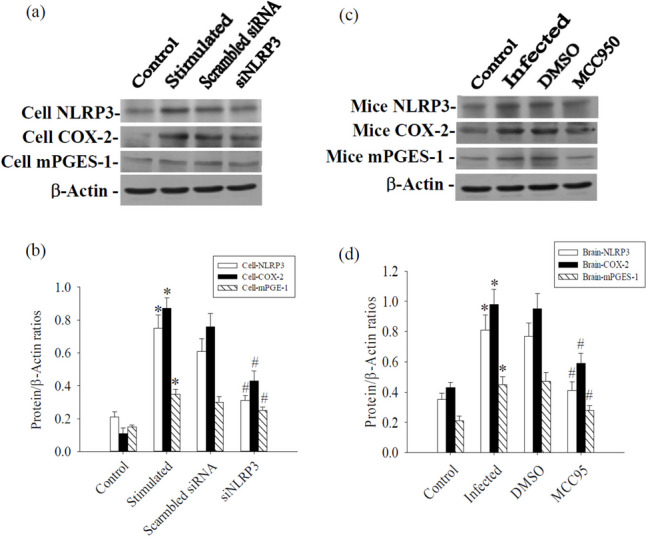

Protein levels of NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 after silencing of NLRP3 in microglia and MCC950 treated mice

Expression levels of NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 were markedly elevated in microglia stimulated by ESPs and in mice induced by A. cantonensis infection. The silencing of NLRP3 resulted in the inhibition of NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 in microglia stimulated by ESPs (Fig. 5a, b). Furthermore, treatment with MCC950 led to a reduced expression of NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 in cerebrum tissue during eosinophilic meningoencephalitis in mice (Fig. 5c, d). It was observed that MCC950 potentially reduces COX-2 expression by suppressing NLRP3 activation. These findings collectively suggest the involvement of the COX-2/mPGES-1 cascade via the NLRP3 inflammasome in both in vitro and in vivo settings. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials.

Fig. 5.

Influence of NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 after NLRP3 silencing in microglia and MCC950 treated mice cerebrum. a NLRP3 silencing inhibited ESPs stimulated NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 in microglia. c MCC950 inhibited Angiostrongylus cantonensis-induced NLRP3, COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the cerebrum of mice. b and d Quantification of protein levels was determined using computer-assisted imaging densitometry. β-actin served as a loading control. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were indicated by * for a significant increase in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to the control and # for a significant decrease in treated mice compared to infected mice with A. cantonensis

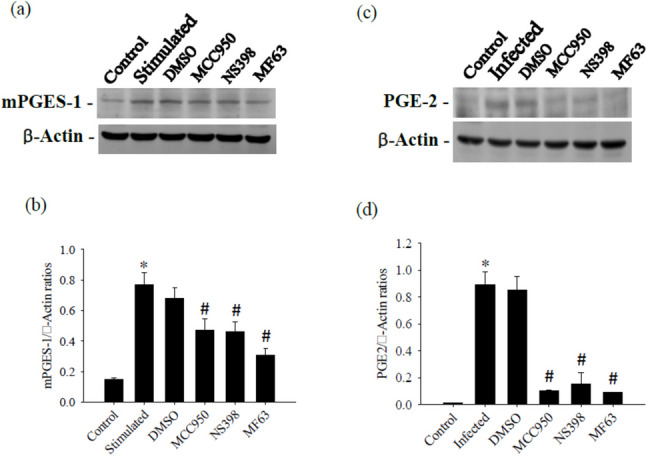

MCC950, NS398, and MF63 exert distinct effects on mPGES-1 and PGE-2 levels

mPGES-1 serves as the terminal enzyme downstream of COX-2 in the inducible PGE-2 synthesis cascade. To determine whether PGE-2 synthesis reduced from the action of NLRP3, we initially examined the effects of NLRP3 inhibitors, specifically MCC950, on A. cantonensis-induced PGE-2 production in the cerebrum. Treatment with NS-398 led to a significant reduction in PGE-2 levels. Furthermore, the mPGES-1 inhibitor MF63 selectively inhibited PGE-2 production, further supporting the involvement of mPGES-1 in this cascade. Furthermore, A. cantonensis-induced mPGES-1 and PGE-2 levels were markedly reduced by treatment with MCC950, NS398, or MF63, underscoring the importance of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in mediating PGE-2 synthesis in this context. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effects of NS398 and MF63 on mPGES-1 and PGE-2. The test groups were: uninfected mice (control); Angiostrongylus cantonensis-infected untreated mice (infected); mice treated with NS398; mice treated with MF63. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were denoted by * to indicate a significant increase in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to control, and # to indicate a significant decrease in treated mice compared to infected mice with A. cantonensis

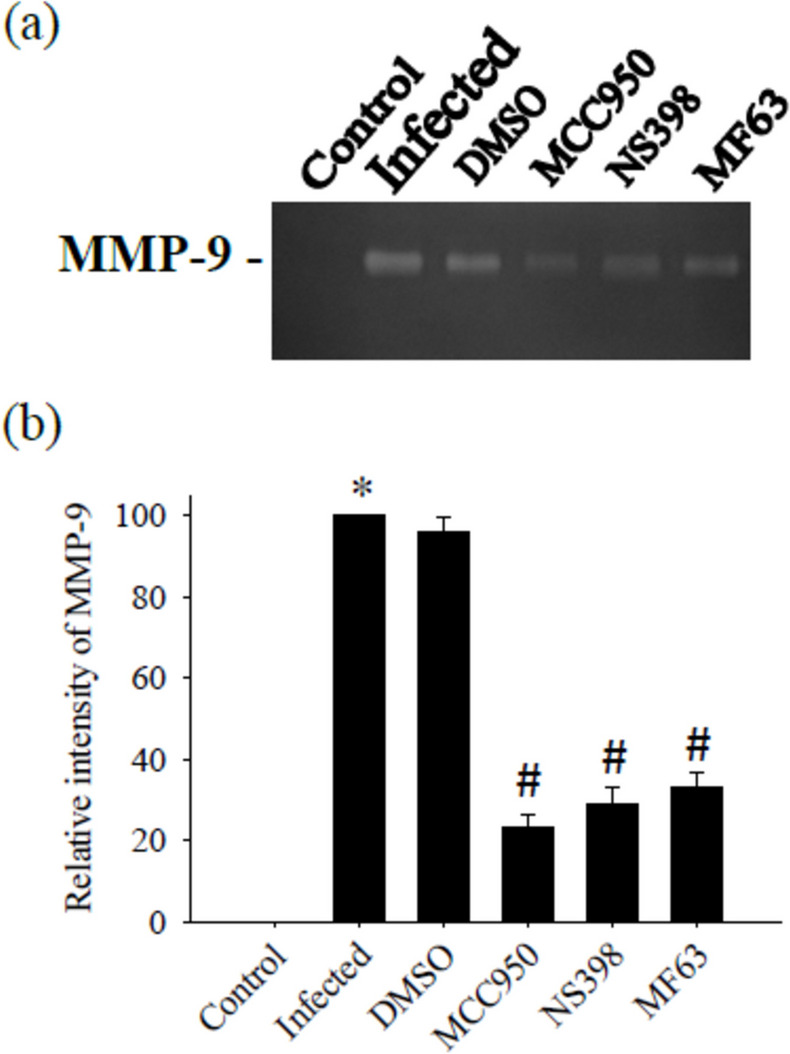

The activity of MMP-9 is influenced by treatment with MCC950, NS398, and MF63

This study aimed to explore the impact of MCC950, an inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome, on the activity of MMP-9 induced by A. cantonensis. MMP-9 levels were markedly elevated in mice induced by A. cantonensis infection. We evaluated the effect of MCC950 on the enzymatic activity in the CSF through gelatin zymography. The results demonstrated that MCC950 effectively inhibited MMP-9 activity. Furthermore, the investigation of MMP-9 levels in the CSF by Western blotting revealed that MMP-9 activity was significantly suppressed by NS398 and MF63, indicating the involvement of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in the regulation of MMP-9 activity in this context. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Influence of MMP-9 activity by treatment with MCC950, NS398 and MF63. The test groups were: uninfected mice (control); Angiostrongylus cantonensis-infected untreated mice (infected); mice treated with MCC950; mice treated with NS398; mice treated with MF63. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. Statistically significant differences were denoted by * to indicate a significant increase in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to control, and # to indicate a significant decrease in treated mice compared to infected mice with A. cantonensis

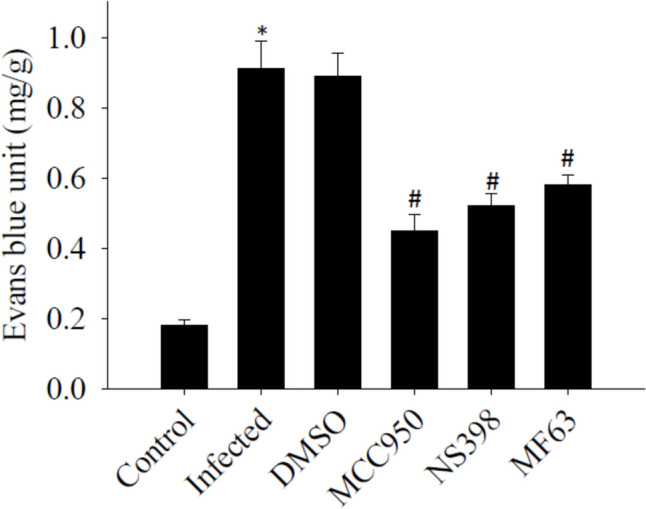

The impact of MCC950, NS398, and MF63 on BBB permeability

BBB permeability increased significantly (P < 0.05) in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to uninfected controls. Administration of the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950, the COX-2 inhibitor NS398, and the mPGES-1 inhibitor MF63 after A. cantonensis infection resulted in a reduction in the disruption of the BBB in infected mice, comparable to the levels observed in the control group. These findings underscore the potential of NLRP3, COX-2, and mPGES-1 inhibitors in mitigating BBB dysfunction associated with A. cantonensis infection. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Influence of blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability by treatment with MCC950, NS398 and MF63. The test groups were: uninfected mice (control); Angiostrongylus cantonensis-infected untreated mice (infected); mice treated with MCC950; mice treated with NS398; mice treated with MF63. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. The notation * signifies a statistically significant increase in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to the control, while # indicates a statistically significant decrease in treated mice compared to infected mice with A. cantonensis

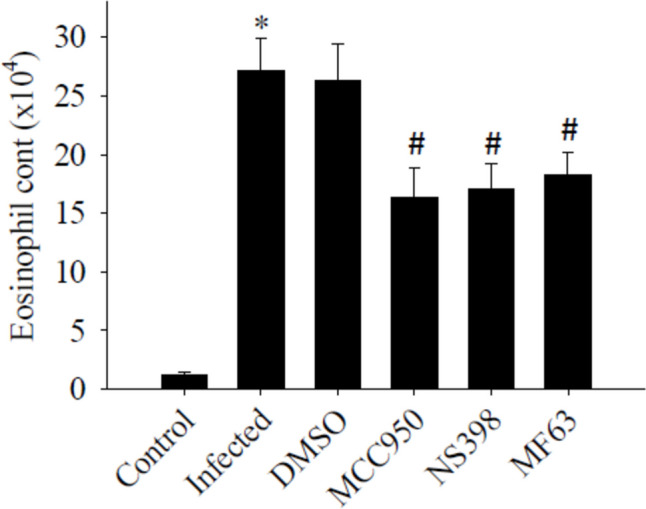

The effects of MCC950, NS398, and MF63 on eosinophil counts

Eosinophils in the CSF increased significantly increased (P < 0.05) in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to uninfected controls. However, A. cantonensis-induced eosinophils were significantly reduced by treatment with MCC950, NS398, or MF63. The inhibition of NLRP3, COX-2, or mPGES-1 effectively suppressed brain inflammation in the BALB/c model. The experiment was conducted three times independently, with consistent results observed across all trials (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Influence of eosinophil counts by treatment with MCC950, NS398, and MF63. The test groups were: uninfected mice (control); Angiostrongylus cantonensis-infected untreated mice (infected); mice treated with MCC950; mice treated with NS398; mice treated with MF63. All values are the average of at least three independent experiments ± standard error of mean (SD), with a technical duplicate in each experiment. * denotes a statistically significant increase in mice infected with A. cantonensis compared to the control group, while # indicates a statistically significant decrease in treated mice compared to infected mice with A. cantonensis

Discussion

Under normal physiological conditions, the presence of COX-2 is minimal, but notably heightened in response to inflammatory triggers (Blais et al. 2005). Our findings demonstrate that COX-2 expression was scarce in the saline group but significantly elevated in A. cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Similarly, the expression kinetics of mPGES-1 mirrored those of COX-2 in response to A. cantonensis infection. These observations strongly imply the pivotal role of an inflammatory mechanism in the induction of COX-2. Furthermore, upstream regulation involves the NLRP3 inflammasome in mediating COX-2 activation (Zhang et al. 2022). Our study revealed a positive correlation between COX-2 production and eosinophil counts. Silencing NLRP3 through siRNA substantially attenuated the COX-2/mPGES-1 cascade in microglia. In our animal model, treatment with MCC950 effectively reversed the pronounced elevation of COX-2 and mPGES-1 in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. These findings strongly suggest that the NLRP3 inflammasome may play a crucial role in mediating A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis by activating the COX-2/mPGES-1 cascade.

Numerous studies indicate that elevated levels of PGE-2, synthesised by COX-2, play a significant role in brain inflammation (Ikeda-Matsuo Y. 2017). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis remain largely elusive. In our current investigation, we observed a significant increase in the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 cascade in BALB/c mice after A. cantonensis infection. To assess whether activation of COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 signaling contributes to A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis, we employed the COX-2 inhibitor NS398 and the mPGES-1 inhibitor MF63. Intriguingly, inhibition of COX-2 led to a reduction in mPGES-1 and PGE-2 levels induced by the challenge of A. cantonensis. At the same time, the release of PGE-2 was reduced by NS398 and MF63. These findings suggest that blocking PGE-2 production by inhibiting its synthetic enzymes, COX-2 or mPGES-1, could improve the brain inflammatory response in A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis. Taken together, our results strongly support the notion that the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 cascade serves as a detrimental factor in A. cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis.

COX-2 activity has been identified as a key regulator of MMP-9 activity and is essential to maintain the integrity of the BBB during brain inflammation (Aid et al. 2010). However, the involvement of MMP-9 activation in COX-2-mediated BBB disruption in angiostrongyliasis meningoencephalitis remains unclear. Previous findings from our laboratory suggested that MMP-9 could contribute to BBB breakdown and facilitate eosinophil infiltration into the cerebral parenchyma through BBB leakage during A. cantonensis infection (Chiu and Lai 2014). In this study, we observed a positive correlation between COX-2/mPGES-1 expression and MMP-9 activity in the CSF. We hypothesised that pharmacological inhibition of COX-2/mPGES-1 would mitigate BBB damage by reducing MMP-9 activity in a mouse model of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. Indeed, infection with A. cantonensis led to a significant increase in enzymatic activity in the CSF, which was markedly attenuated by pharmacological inhibition using NS398 and MF63. Our findings reveal, for the first time, that disruption of BBB during eosinophilic meningoencephalitis can be significantly mitigated by administering a COX-2 inhibitor. Modulation of COX-2 activity in eosinophilic meningoencephalitis through COX-2 inhibitors or agents that regulate PGE-2 formation may offer promising therapeutic strategies to address the disruption of the BBB. Therefore, it is plausible to speculate that the protective effect of COX-2/mPGES-1 inhibition against the BBB dysfunction is of considerable importance.

Microglia and eosinophils are both types of immune cells, but are found in different parts of the body and serve distinct functions. However, recent research suggests that there may be interactions between them under certain conditions, particularly in the context of neuroinflammation and autoimmune diseases (Owens et al. 2020). In microglia, COX-2 and mPGES-1 are involved in neuroinflammatory responses, potentially affecting the neuroimmune environment in various neurological conditions (de Oliveira et al. 2016). While the direct effect of COX-2/mPGES-1 in microglia on eosinophil count specifically in the brain or systemic circulation is not fully elucidated, there is a plausible connection through the inflammatory mediator PGE-2. Increased COX-2/mPGES-1 activity in microglia could enhance the inflammatory response, potentially leading to the recruitment and activation of eosinophils, contributing to both peripheral and possibly neuroinflammatory processes. Further research would be needed to fully clarify this relationship in A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis.

Eosinophils have been shown to possess cytotoxic effects in A. cantonensis infection, with noticeable eosinophil infiltration occurring around the worm surface (Yoshimura et al. 1984). Our previous findings indicated that MMP-9 was sequestered within small eosinophil granules and subsequently released into the subarachnoid space through cytoplasmic granules or cell rupture (Tseng et al. 2004). In this study, we observed a significant correlation between the eosinophil count in the CSF and the expression of COX-2/mPGES-1. Eosinophils in A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis decreased markedly with inhibition of COX-2 and mPGES-1. We showed that NS398 and MF63 exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting COX and mPGES-1 activities, both of which have been deemed essential targets for the development of anti-inflammatory treatments in various pathologies, including eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. These findings strongly suggest that the regulatory effects of A. cantonensis on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis are mediated by the COX-2/mPGES-1 axis. Thus, this study enhances our understanding of the inflammatory mechanisms involved and proposes a potential therapeutic strategy for A. cantonensis infections.

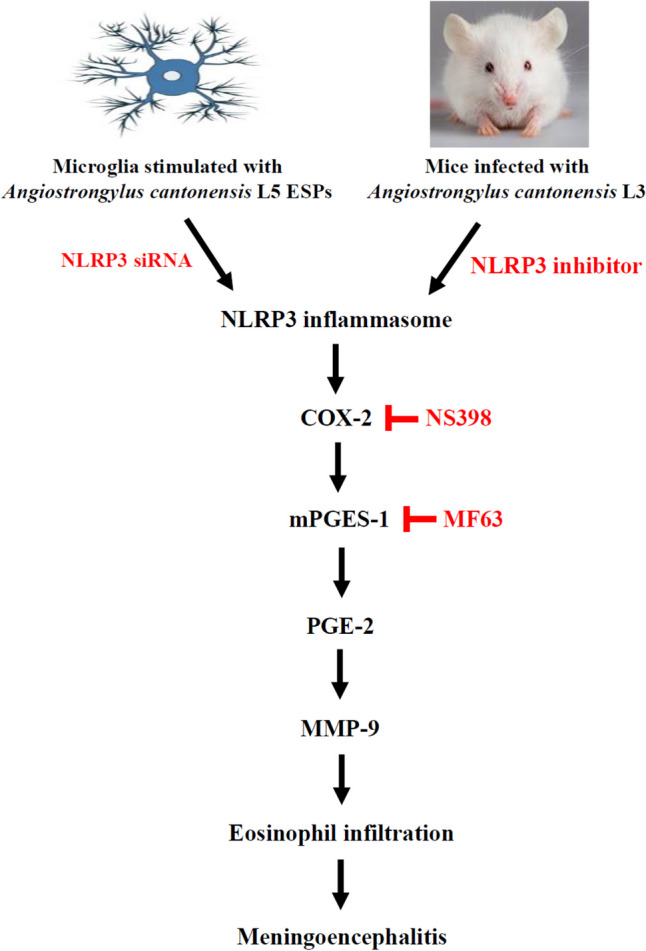

Our findings highlight that blocking NLRP3 reduces COX-2 and mPGES-1 both in vitro and in vivo. This suggests that the NLRP3 inflammasome may play a key role in mediating A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis by activating the COX-2/mPGES-1 cascade. Furthermore, the release of PGE-2 was reduced by the COX-2 inhibitor NS398 and the mPGES-1 inhibitor MF63. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of COX-2/mPGES-1 was found to mitigate damage to the BBB by reducing MMP-9 activity in a mouse model. This underscores the involvement of the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 axis in the regulation of MMP-9 activity in A. cantonensis-infected mice. Eosinophils were found to increase in A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis and were markedly decreased upon inhibition of COX-2 and mPGES-1. We demonstrated that NS398 and MF63 exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting COX and mPGES-1 activities. These results suggest a crucial role for NLRP3 inflammasome involved in the production of chemical mediators that contribute to the inflammatory response in A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

A schematic diagram illustrating the proposed signaling pathway involved in Angiostrongylus cantonensis-induced COX-2, mPGES-1 and PGE2: COX-2 is an inducible enzyme that converts arachidonic acid into PGH2, which is further transformed into prostaglandins, including PGE-2. Inflammatory PGE2 is produced from PGH2 by an enzyme called microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 (mPGES-1). In a murine model of angiostrongyliasis meningoencephalitis, inhibition of NLRP3 led to decreased expression of COX-2 and mPGES-1. Additionally, treatment with MCC950, NS398 or MF63 suppressed eosinophil count by reducing MMP-9 activities by inhibiting the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE2 pathway. These findings reveal the involvement of COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE2-mediated signaling pathways in the regulation of MMP-9 activity and subsequent eosinophilic meningoencephalitis

In summary, our study elucidates the crucial role of NLRP3 in mediating A. cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis by activating the COX-2/mPGES-1/PGE-2 cascade in BALB/c mice. The activation of this cascade appears to contribute significantly to the pathogenesis of A. cantonensis-induced meningoencephalitis. These findings provide valuable information that could potentially advance our understanding and treatment of A. cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis, opening avenues for further research and therapeutic development in this area.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

(PDF 318 KB)

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Ping-Sung Chiu from the Department of Parasitology at Chung Shan Medical University for his invaluable assistance in facilitating the execution of this study.

Author contribution

Shih-Chan Lai: Conceptualization, supervision and writing – original draft. Ke-Min Chen: Methodology, resources and Software. Cheng-You Lu: Validation and visualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from Chung-Shan Medical University (CSMU-INT-112–17), Taiwan.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study received approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Chung-Shan Medical University, and all procedures were conducted following institutional guidelines for animal experiments. The manuscript does not include any clinical or patient data.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aid S, Silva AC, Candelario-Jalil E, Choi SH, Rosenberg GA, Bosetti F (2010) Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 differentially modulate lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption through matrix metalloproteinase activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30:370–380. 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasson K (2010) Emerging roles of PGE2 receptors in models of neurological disease. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 91:104–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blais V, Turrin NP, Rivest S (2005) Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibition increases the inflammatory response in the brain during systemic immune stimuli. J Neurochem 95:1563–1574. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candelario-Jalil E, Gonzalez-Falcon A, Garcia-Cabrera M, Leon OS, Fiebich BL (2007) Post-ischaemic treatment with the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor nimesulide reduces blood-brain barrier disruption and leukocyte infiltration following transient focal cerebral ischaemia in rats. J Neurochem 100:1108–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Shyu LY, Hsin YL, Chen KM, Lai SC (2017) Resveratrol relieves Angiostrongylus cantonensis - induced meningoencephalitis by activating sirtuin-1. Acta Trop 173:76–84. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Shyu LY, Lin YC, Chen KM, Lai SC (2019) Proteasome serves as pivotal regulator in Angiostrongylus cantonensis-induced eosinophilic meningoencephalitis. PLoS ONE 14:e0220503. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KM, Lan KP, Lai SC (2022) Heme oxygenase-1 modulates brain inflammation and apoptosis in mice with angiostrongyliasis. Parasitol Int 87:102528. 10.1016/j.parint.2021.102528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu PS, Lai SC (2013) Matrix metallopeinase-9 leads to claudin-5 degradation through the NF-κB pathway in BALB/c mice with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. PLoS ONE 8:e53370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu PS, Lai SC (2014) Matrix metalloproteinase-9 leads to leakage of the blood-brain barrier in mice with eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Acta Trop 140:141–150. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivero ET, Thangaraj A, Tripathi A, Periyasamy P, Guo ML, Buch S (2021) NLRP3 inflammasome blockade reduces cocaine-induced microglial activation and neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol 58:2215–2230. 10.1007/s12035-020-02184-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira AC, Yousif NM, Bhatia HS, Hermanek J, Huell M, Fiebich BL (2016) Poly(I:C) increases the expression of mPGES-1 and COX-2 in rat primary microglia. J Neuroinflammation 13:11. 10.1186/s12974-015-0473-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Generoso JS, Faller CJ, Collodel A, Catalão CHR, Dominguini D, Petronilho F, Barichello T, Giridharan VV (2024) NLRP3 activation contributes to memory impairment in an experimental model of pneumococcal meningitis. Mol Neurobiol 61:239–251. 10.1007/s12035-023-03549-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffaripour Jahromi G, Razi S, Rezaei N (2024) NLRP3 inflammatory pathway. Can we unlock depression? Brain Res 1822:148644. 10.1016/j.brainres.2023.148644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorfu G, Cirelli KM, Melo MB, Mayer-Barber K, Crown D, Koller BH, Masters S, Sher A, Leppla SH, Moayeri M, Saeij JP, Grigg ME (2014) Dual role for inflammasome sensors NLRP1 and NLRP3 in murine resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. mBio 5:e01117–13. 10.1128/mBio.01117-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Graeff-Teixeira C, da Silva ACA, Yoshimura K (2009) Update on eosinophilic meningoencephalitis and its clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 22:322–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashimori A, Watanabe T, Nadatani Y, Nakata A, Otani K, Hosomi S, Tanaka F, Kamata N, Taira K, Nagami Y, Tanigawa T, Fujiwara Y (2021) Role of nucleotide binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome in stress-induced gastric injury. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 36:740–750. 10.1111/jgh.15257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda-Matsuo Y (2017) The role of mPGES-1 in inflammatory brain diseases. Biol Pharm Bull 40:557–563. 10.1248/bpb.b16-01026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvi S, Prociv P (2021) Angiostrongylus cantonensis and neuroangiostrongyliasis (rat lungworm disease): 2020. Parasitology 148:129–132. 10.1017/S003118202000236X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam HYP, Chen TT, Chen CC, Yang TH, Cheng PC, Peng SY (2020) Angiostrongylus cantonensis activates inflammasomes in meningoencephalitic BALB/c mice. Parasitol Int 77:102119. 10.1016/j.parint.2020.102119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens T, Benmamar-Badel A, Wlodarczyk A, Marczynska J, Mørch MT, Dubik M, Arengoth DS, Asgari N, Webster G, Khorooshi R (2020) Protective roles for myeloid cells in neuroinflammation. Scand J Immunol 92:e12963. 10.1111/sji.12963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng YK, Tu WC, Lee HH, Chen KM, Chou HL, Lai SC (2004) Ultrastructural localization of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in eosinophils from the cerebrospinal fluid of mice with eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 98:831–841. 10.1179/000349804X3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang QP, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, Chen XG, Lun ZR (2008) Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis 8:621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagami T, Koma H, Yamamoto Y (2016) Pathophysiological roles of cyclooxygenases and prostaglandins in the central nervous system. Mol Neurobiol 53:4754–4771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura K, Uchida K, Sato K, Oya H (1984) Ultrastructural evidence for eosinophil-mediated destruction of Angiostrongylus cantonensis transferred into the pulmonary artery of nonpermissive hosts. Parasite Immunol 6:105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Tang Y, Huang P, Luo S, She Z, Peng H, Chen Y, Luo J, Duan W, Xiong J, Liu L, Liu L (2024) Role of NLRP3 inflammasome in central nervous system diseases. Cell Biosci 14:75. 10.1186/s13578-024-01256-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Wang XL, Shi H, Meng LQ, Quan HF, Yan L, Yang HF, Peng XD (2022) Betaine inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome hyperactivation and regulates microglial M1/M2 phenotypic differentiation, thereby attenuating lipopolysaccharide-induced depression-like behavior. J Immunol Res 9313436:9313436. 10.1155/2022/9313436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 318 KB)

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.