Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to identify the genes associated with the development of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and potential therapeutic targets.

Methods

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by self-transcriptome sequencing of tumor tissues and paracancerous tissues resected during surgery and combined with The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data to screen for the genes associated with LUAD prognosis. The expression was validated at mRNA and protein levels, and the gene knockdown was used to examine the impact and underlying mechanisms on lung cancer cells.

Results

A total of 227 DEGs were identified by transcriptome sequencing, and the 20 DEGs with the most significant differences were used for co-analysis with TCGA data. The findings suggested that KRT16 and ANXA10 might have an important role in the development of LUAD after validating the mRNA and protein expression levels at the cellular level. The knockdown of KRT16 and ANXA10 inhibited the proliferation of lung cancer cells, and the cell cycle was blocked in the G1 phase. The expression of the G1/S–phase cell cycle checkpoint–related proteins cyclin D1 and cyclin E was inhibited by KRT16 and ANXA10 knockdown, respectively. The tumor formation ability decreased after KRT16 or ANXA10 knockdown in vivo.

Conclusions

KRT16 and ANXA10 are potential genes regulating the development of LUAD. Also, they may be potential targets for the targeted therapy of LUAD by inhibiting the proliferation of lung cancer cells and blocking the cell cycle by affecting key protein expression levels at cell cycle checkpoints.

Keywords: ANXA10, KRT16, Lung adenocarcinoma, TCGA, Transcriptome sequencing

Introduction

Lung cancer, a formidable adversary in the realm of malignancies, reigns supreme as one of the most pervasive and fatal tumors on a global scale [1]. The World Health Organization data show that approximately 2 million individuals are diagnosed with lung cancer annually [2]. Among its various types, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) emerges as the predominant subtype, accounting for approximately 85% of all lung cancer diagnoses. Compared with squamous cell carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the main pathological type [3]. Despite the remarkable progress in medical research and innovative technologies in early-stage lung cancer therapeutics over recent years, advanced lung cancer treatment is still challenging [3]. Presently, various strategies are used to treat NSCLC including, but not limited to, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, precision-targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [4]. Of these, targeted therapy and immunotherapy have emerged as promising approaches, garnering widespread acclaim for their efficacy and profound potential in enhancing the life quality of those afflicted. Yet, lung cancer, with its complexities and diversities, demands a one-size-fits-all therapeutic approach. This has led to investigations into the molecular underpinnings of lung cancer, focusing on the genetic intricacies and distinct expression paradigms associated with the disease [5]. The previous decade has witnessed groundbreaking revelations in lung cancer biology, powered by meticulous gene function research. Pivotal discoveries, such as the mutations in genes such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), and ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1), now stand as defining markers for specific NSCLC subtypes, serving as prime targets in the contemporary targeted therapeutic landscape [6].

EGFR is a well-recognized target in lung cancer drug research. Therapies targeting EGFR, including gefitinib and erlotinib, have demonstrated notable efficacy in treating patients with NSCLC with EGFR mutations. The development of EGFR inhibitors has progressed to third-generation compounds such as osimertinib, which can target drug-resistant mutations, specifically T790M. Their inclusion in clinical practice has improved patient survival rates [6]. ALK is another critical target in lung cancer research. The introduction of ALK-targeted drugs has significantly changed the therapeutic landscape. Crizotinib was the first approved drug for ALK-positive lung cancer, followed by next-generation ALK inhibitors, such as ceritinib, alectinib, and brigatinib, which have shown improved outcomes, especially for patients who did not respond to crizotinib. ALK inhibitors, especially crizotinib, offer promising results for patients with ROS1 fusion gene mutations [7]. The drug spectrum has been further broadened with the introduction of entrectinib for ROS1-positive NSCLC. Research focusing on EGFR, ALK, and ROS1 therapies has significantly advanced lung cancer treatment [8]. However, the challenges of drug resistance and potential unknown genetic mutations necessitate continuous monitoring and ongoing research. Identifying new therapeutic targets remains crucial, given the complex nature of lung cancer pathology. Fortunately, efforts to discover new NSCLC targets are being made.

KRAS stands out in the context of LUAD mutations. Sotorasib has been identified as a potential drug targeting the KRAS G12C mutation, with clinical trials supporting its efficacy [9]. Though less common, mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor (MET) and rearranged during transfection (RET) gene mutations in lung cancer have been targeted therapeutically. Crizotinib and capatinib have shown effectiveness against MET mutations, whereas pratinib and selatinib have been effective against RET mutations [10, 11]. Although human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) mutations and amplification are less prevalent in lung cancer, clinical trials suggest that agents such as trastuzumab and adetinib have potential against HER2-driven tumors [12].

The landscape of therapeutic targets is continuously evolving, leading to the development of innovative drugs with the potential to significantly improve outcomes for patients with lung cancer. This study also focused on this aspect. It used transcriptome sequencing of surgical tissues, combined with TCGA data mining, to discover the potential key genes involved in the progression of LUAD. Our goal was to understand the functions of these genes, establishing a foundation offering insights to direct future research and development of novel lung cancer therapies.

Materials and methods

Clinical sample collection and processing

A cohort of five patients undergoing surgical intervention for LUAD was evaluated. All patients initially presented at First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University hospital and were preliminarily diagnosed with NSCLC based on a CT scan. The postoperative histopathological assessment confirmed the diagnosis of LUAD for each patient. The basic characteristics of patients are outlined in Table 1. During the surgical procedure, the samples were extracted from both the tumor and the para-cancer tissues located 2 cm from the tumor margin. These samples were immediately stored at − 80 °C. Subsequently, the samples were dispatched to Meiji Biology (Shanghai, China) under controlled conditions with dry ice for further transcriptome sequencing analysis.

Table 1.

The details of 5 patients in this study cohort

| Number | Age | Sex | Date of diagnosis | Date of operation | Neoadjuvant therapy | Pathological stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 57 | Male | 2022-Aug-19 | 2022-Aug-10 | No | T2N0M0 |

| Patient 2 | 74 | Male | 2022-Aug-23 | 2022-Aug-10 | No | T2N0M0 |

| Patient 3 | 53 | Male | 2022-Aug-23 | 2022-Aug-12 | No | T2N1M0 |

| Patient 4 | 68 | Male | 2022-Aug-22 | 2022-Aug-15 | No | T2N0M0 |

| Patient 5 | 70 | Male | 2022-Aug-22 | 2022-Aug-16 | No | T1N0M0 |

Differentially expressed gene and enrichment analyses

The transcriptome data were processed using the R language (version 4.2.1). Initially, the DESeq2 package (3.7) was employed for differential data analysis, examining the raw count matrix for potential disparities. Following the standard procedure within this package, the variance stabilizing transformation method was used to normalize the count matrix. For visual representation, differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were plotted as a heatmap using the ComplexHeatmap package (2.13.1). The data were converted into log2 values and subsequently clustered based on the Euclidean distance. Additionally, volcano maps were generated using the ggplot2 package, setting threshold values at 3 for logFC and 0.01 for P value. Further, DEGs were channeled for Disease Ontology (DO), Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analyses. The clusterProfiler package (4.4.4) facilitated enrichment analysis. The selected species was human (Homo sapiens), and the ID conversion package employed was org.Hs.eg.db (3.17).

TCGA data mining

The data mining of TCGA was conducted using the website platform The University of ALabama at Birmingham CANcer data analysis Portal (UALCAN) (https://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) [13]. This online tool facilitated the juxtaposition of the expression levels of specific genes within LUAD tissue sequencing data of TCGA and enabled the assessment of the prognostic relationship of individual genes using a ratio of 1:3 to differentiate between higher– and lower–gene expression groups. A significance threshold was set at P < 0.05.

Cell culture

Five kinds of cell lines were employed: the normal lung epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (SCSP-5067) and NSCLC cell lines A549 (SCSP-503), NCI-H1299 (SCSP-589), H1975 (SCSP-597), and 801D (TCHu 61). All cell lines were procured from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Shanghai, China) and subsequently authenticated using STR. The cells were cultured in the RPMI1640 medium (G4531-500ML, Servicebio, China) supplemented with 10% FBS (G8002-500ML, Servicebio, China) in a cell culture incubator set at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

RNA was isolated from the cells using the TRIzol reagent (G3013-100ML, Servicebio, China). RNA concentration was detected using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, USA). From the extracted RNA, 1 µg was then reverse transcribed to cDNA using an RT-PCR kit (RR014A, Takara, Japan). The quantification of mRNA levels was conducted using PowerUp SYBR Green (A25742, Applied Biosystems, USA). The details of the primers used for these experiments are outlined in Table 2. The relative mRNA expression was calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method. In this study, three independent qPCR experiments were performed, and the average of the relative expression multiples was taken to calculate the expression differences.

Table 2.

The primer for qPCR in this study

| Gene | Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| RAET1L | Forward Primer | GATGGACAGACCTTCCTACTCT |

| RAET1L | Reverse Primer | GGCTCCAGGATGAACCGTT |

| KRT14 | Forward Primer | TGAGCCGCATTCTGAACGAG |

| KRT14 | Reverse Primer | GATGACTGCGATCCAGAGGA |

| KRT16 | Forward Primer | GACCGGCGGAGATGTGAAC |

| KRT16 | Reverse Primer | CTGCTCGTACTGGTCACGC |

| DSG3 | Forward Primer | CACCTACCGAATCTCTGGAGT |

| DSG3 | Reverse Primer | GGGCATTTAGAGCCCGACA |

| ANXA10 | Forward Primer | GCTGGCCTCATGTACCCAC |

| ANXA10 | Reverse Primer | CAAGCAGTAGGCTTCTCGC |

| MYOC | Forward Primer | AGGAACTGAAGTCCGAGCTAA |

| MYOC | Reverse Primer | GTTCTCCACATCCGGTGTCTC |

| CA4 | Forward Primer | CTCTGGCTACGATAAGAAGCAAA |

| CA4 | Reverse Primer | CAGTGCAGGTGCAACTGTTT |

| KRT6A | Forward Primer | GCACATCCACCACCATCAGGAG |

| KRT6A | Reverse Primer | CCACCGAAACCAAATCCACTCCC |

Protein extraction and western blot

The cells were lysed using RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors (Beyotime Biotechnology, China) for determining the expression levels of DEGs. Western blot was used to detect the protein expression, employing the following: 4%–12% preformed adhesive (ET12412Gel, ebio-ACE, China), MOPS-SDS running buffer (BR0001-02, ebio-ACE), transmembrane buffer (G2148-1L, Servicebio, China), TBST buffer (G2150-1L, Servicebio), and ECL chemiluminescence kit (G2161-200ML, Servicebio). Western blot was performed following the methodologies described in a previous study [14]. The primary antibodies for this study were procured from Proteintech (Wuhan, China) and were as follows: GAPDH (10494-1-AP), DSG3 (29942-1-AP), MYOC (14238-1-AP), KRT16 (17265-1-AP), ANXA10 (66869-1-Ig), CDK2 (10122-1-AP), CDK4 (11026-1-AP), CDK6 (14052-1-AP), cyclin D1 (26939-1-AP), and cyclin E (11935-1-AP). Before antibody hybridization, the blank lane was cut and the full length of the protein lane was preserved. Three independent Western blots were used for each protein, and the results of one of them were presented at random.

CRISPR–Cas9 knockout system for cell line construction

The px458 vector, referenced as 48138 in Addgene, contains a green fluorescent protein gene, ampicillin resistance, and a sequence designed specifically for Bbs1 enzyme cleavage. It was used to craft the vector plasmid for the CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing system to knock out KRT16 and ANXA10 in LUAD cells. We evaluated several sgRNA sequences, which culminated in the development of a CRISPR–Cas9 tool plasmid that adeptly knocked down the target genes. The sgRNA sequences were as follows: KRT16: 5′-GACCGGCGGAGATGTGAACG-3′; ANXA10: 5′- CTCAGCGCTGCAATGCACAA-3′. After screening the cells with a fluorescent dye and a single clone, stably expressing cell lines with KRT16 and ANXA10 knockdown were finally obtained. Western blot was used to verify the knockout effect. The detailed program of gene knockout followed the protocol from Addgene.

Cell counting kit 8

The KRT16 knockout, ANXA10 knockout, and control group cells were seeded into 96-well plates (3000 cells per well). Cell viability was determined at intervals of 24, 48, and 72 h using the cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8) assays (Cat. c0038, Beyotime, China). The assays were conducted in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. In this study, three independent CCK-8 experiments were performed, and the average of the relative growth rate multiples was taken to calculate the differences in proliferation ability.

Cell cycle assay

The cells were cultured in six-well plates at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells/well. Then they were fixed with 80% ethanol 48 h after transfection and placed at − 20 °C overnight to assess the cell cycle. Subsequently, the cells were stained with PI/RNase staining buffer from the cell cycle kit (Cat. c1052, Beyotime, China). The cell cycle distribution was ascertained using flow cytometry, and the acquired data were further analyzed employing ModFit LT software (version 5.0). In this study, three independent experiments were performed by flow cytometry, and the average cell cycle distribution was used to calculate the cell cycle differences.

Cell-derived xenograft assay

The cells were digested from the culture flasks using trypsin and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After counting the total number of cells, the cell sediment was resuspended using PBS and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 107/mL. BALB/c nude mice were used to construct the cell-derived xenograft model. Further, 1 × 106 cells were injected intramuscularly into the arm. The tumor volume and weight were detected after 21 days. The experiment was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Anhui medical university (LLSC20231439) and conducted in strict accordance with the animal welfare guidelines. In accordance with animal ethics and welfare regulations, the volume of mouse tumors does not exceed 1000 cm3. In this study, all animals exceeded this requirement. At the same time, according to the requirements of animal welfare, the mice in this study were killed by carbon dioxide execution, and the relevant operations were carried out after the death.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 6.0.1). The data were presented as mean ± standard deviation from a minimum of three independent trials. The Student t test was employed to determine the differences between the two groups. One-way analysis of variance was used to determine differences among groups. A P value < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

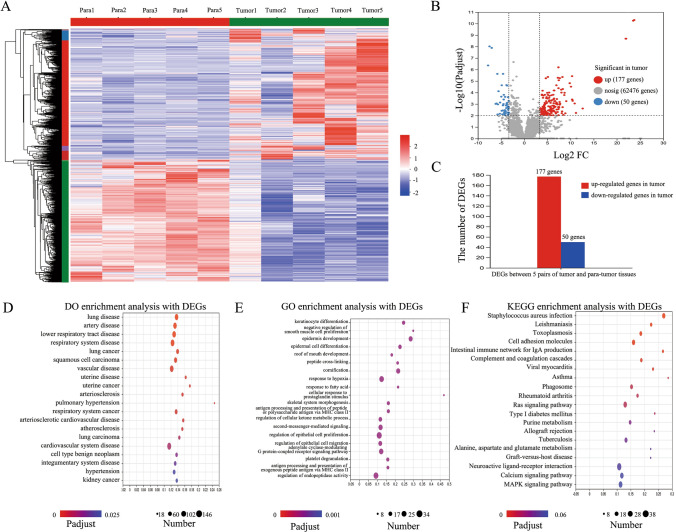

Identification of 227 DEGs and functional enrichment analysis

In the initial phase of this study, we obtained surgical tissue specimens from five patients diagnosed with LUAD, along with their para-cancer tissue samples, and subjected these tissues to transcriptome sequencing. This approach yielded 62,701 transcripts. Among these, 225 genes exhibited significant differential expression between tumor and para-cancer tissues (Fig. 1A). Specifically, 177 genes were upregulated in tumor tissues, whereas 50 genes were upregulated in para-cancer tissues (Fig. 1B and C).

Fig. 1.

Identification of 227 DEGs and functional enrichment analysis. A Heatmap of DEGs between LUAD and paracancerous tissues. B Volcano map showing the DEG expression among the total genes detected in this sequencing data. C A total of 177 upregulated and 50 downregulated genes in the LUAD tissues. D Top 20 diseases from DO enrichment analysis with the 227 DEGs. E Top 20 items from GO enrichment analysis with the 227 DEGs. F Top 20 pathways from KEGG enrichment analysis with the 227 DEGs

Functional enrichment analyses, including DO, GO, and KEGG, were conducted on these 225 genes. We highlighted the top 20 enriched terms based on the number of associated genes and significance (P < 0.05). The DO analysis revealed that DEGs predominantly contributed to respiratory diseases (Fig. 1D), aligning with the characteristics of the samples used in this study. The GO enrichment analysis emphasized processes such as keratinocyte differentiation and epidermis development (Fig. 1E). Meanwhile, the KEGG pathway analysis highlighted several pathways renowned for their regulatory roles in lung cancer, such as RAS and MAPK, among the top 20 enriched pathways (Fig. 1F).

Cross-analysis with TCGA data to identify DEGs in LUAD

We further screened the DEGs to enhance our identification of the key regulatory genes in LUAD in the present study. From the 175 upregulated genes in LUAD tissues and 50 downregulated genes, we isolated the top 10 genes based on the magnitude of their expression difference, yielding 20 genes for further examination.

Considering the small sample size of our RNA-seq cohort, the data from TCGA were employed in this study for supplementary screening. We subsequently tapped into the TCGA database to ascertain whether these 20 genes exhibited analogous expression patterns in LUAD tissue sequencing data in TCGA. Our analysis revealed a striking similarity: except SPRR2A and KRT13, the remaining 18 DEGs showcased similar expression trajectories between our sequencing dataset and the TCGA repository (Fig. 2). A comprehensive representation of the expression patterns of these 20 DEGs from our dataset is provided in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Basic expression of 20 DEGs in the TCGA dataset. This comparison involved 59 paracancerous tissues and 515 LUAD tissues. *Indicates the same trend between TCGA and RNA-seq datasets in this study

Table 3.

The details of 20 DEGs from our dataset

| Gene name | Gene description | Log2FC(Tumor/Para) | Padjust | Regulate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAET1L | Retinoic acid early transcript 1L | 23.76932 | 4.92E-11 | Up |

| SPRR1A | Small proline rich protein 1A | 12.62996 | 0.002443 | Up |

| SPRR2A | Small proline rich protein 2A | 11.18004 | 0.00594 | Up |

| KRT14 | Keratin 14 | 10.8915 | 0.000892 | Up |

| KRT16 | Keratin 16 | 10.45697 | 0.000528 | Up |

| KRT6A | Keratin 6A | 10.35728 | 0.000402 | Up |

| SBSN | Suprabasin | 10.33489 | 3.79E-06 | Up |

| DSG3 | Desmoglein 3 | 10.09948 | 3.11E-05 | Up |

| KRT13 | Keratin 13 | 9.090992 | 0.000562 | Up |

| ANXA10 | Annexin A10 | 8.897599 | 0.006343 | Up |

| ANGPTL7 | Angiopoietin like 7 | − 4.55759 | 2.38E-06 | Down |

| CA4 | Carbonic anhydrase 4 | − 4.57515 | 0.001316 | Down |

| CD300LG | CD300 molecule like family member g | − 4.60965 | 0.003578 | Down |

| SH3GL2 | SH3 domain containing GRB2 like 2, endophilin A1 | − 4.67883 | 0.003661 | Down |

| ITLN2 | Intelectin 2 | − 4.85197 | 0.003877 | Down |

| MYOC | Myocilin | − 4.93547 | 0.000229 | Down |

| PI16 | Peptidase inhibitor 16 | − 5.5356 | 7.67E-05 | Down |

| PPBP | Pro-platelet basic protein | − 5.68227 | 0.001073 | Down |

| ANKRD1 | Ankyrin repeat domain 1 | − 6.99993 | 1.3E-08 | Down |

| RBP2 | Retinol binding protein 2 | − 7.78308 | 4.41E-07 | Down |

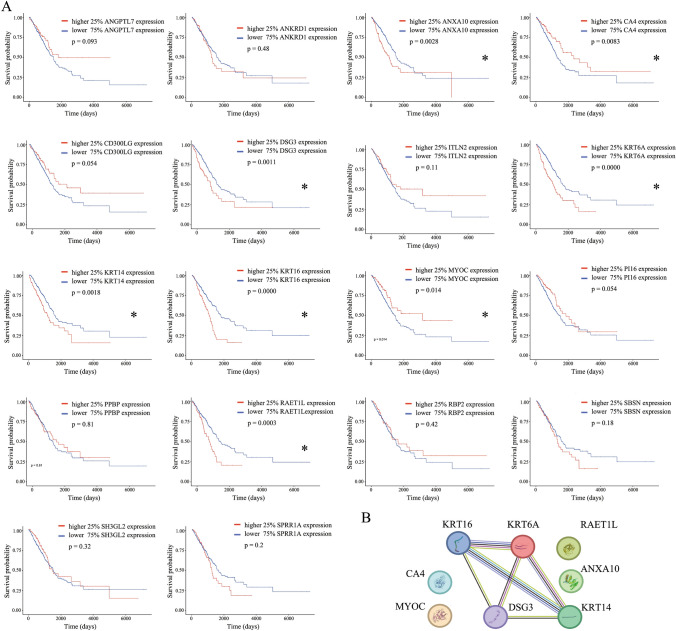

Use of TCGA survival data to pinpoint DEGs associated with survival in LUAD

This study further screened the 18 putative LUAD DEGs, previously identified as having consistent expression patterns, to isolate genes closely linked to the progression and prognosis of LUAD. The expression levels of each gene guided the categorization of data from 502 LUAD cases in the TCGA database to accentuate the comparative analysis. Patients were stratified into higher- and lower-expression cohorts, using a 1:3 ratio, allowing for a comparison of prognostic outcomes based on distinct gene expression profiles. As a result, our findings underscored that out of the 18 DEGs, 8 genes (RAET1L, KRT14, KRT16, KRT6A, DSG3, ANXA10, MYOC, and CA4) manifested significant prognostic differences contingent upon their expression levels (Fig. 3A). Delving further, the PPI analysis illuminated a pronounced interrelation among KRT16, KRT6A, KRT14, and DSG3. Conversely, genes such as RAET1L, ANXA10, MYOC, and CA4 were found to be relatively independent (Fig. 3B). These eight DEGs were further analyzed.

Fig. 3.

Survival analysis of 20 DEGs in the TCGA dataset and the PPI analysis of prognostic-related genes in the 20 DEGs. A Overall survival analysis of 20 DEGs in the TCGA dataset. B PPI analysis of eight prognosis-related genes. *P < 0.05

Expression verification of LUAD DEGs in cell lines

This study aimed to validate the mRNA and protein expression patterns of the identified eight DEGs, employing the human normal lung epithelial cell line BEAS-2B alongside various NSCLC cell lines. Following mRNA expression analysis, KRT16, DSG3, ANXA10, and MYOC were found to exhibit an expression trajectory akin to the transcriptome data (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the expression patterns of the remaining four DEGs in the tumor cell lines diverged from previous observations. Further, we assessed the protein expression levels of KRT16, DSG3, ANXA10, and MYOC within these cells. The resulting trends were consistent with the mRNA findings (Fig. 4B). The expression consistency of DSG3 and MYOC across the four NSCLC cell lines was found to be somewhat variable. Therefore, KRT16 and ANXA10 were selected for verifying the downstream gene function.

Fig. 4.

Basic expression of eight DEGs in normal pulmonary epithelial and LUAD cell lines. A mRNA level of eight DEGs in normal pulmonary epithelial and LUAD cell lines. B Protein expression of four DEGs validated at the aforementioned mRNA level in normal pulmonary epithelial and LUAD cell lines. *P < 0.05, compared with BEAS-2B cells

Knockout of KRT16 and ANXA10 inhibited the proliferation ability and reset the cell cyclin in NSCLC cells

The preliminary experiments revealed a significant influence of two genes, KRT16 and ANXA10, on cell morphology and growth (data not shown). This investigation pinpointed KRT16 and ANXA10 as potential novel regulators influencing LUAD initiation and progression. After pre-experiment and publication reference, A549 cells, one of the most commonly used cells in LUAD studies, were employed as the knockout gene cell model. KRT16 and ANXA10 were knocked out using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. The Western blot showed a lack of protein expression in the knockout cells (Fig. 5A and D). The CCK8 revealed a noticeable decrement in the proliferation rates across cell lines with suppressed KRT16 and ANXA10 levels (Fig. 5B and E). Notably, the A549 cell lines, after KRT16 and ANXA10 knockdown, exhibited a pronounced accumulation in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 5C and F).

Fig. 5.

Gene function of KRT16 and ANXA10 in LUAD cell lines. A KRT16 expression was knocked out in A549 and H1299 cells. B ANXA10 expression was knocked out in A549 and H1299 cells. C and D Proliferation ability was inhibited in KRT16 knockout cells. E and F Proliferation ability was inhibited in ANXA10 knockout cells. G and H Knockout of KRT16 or ANXA10 could arrest the A549 and H1299 cells in the G1 phase. I Flow diagram of A549 cells with KRT16 or ANXA10 knockout. J Cell cycle–related protein expression in A549 cells with KRT16 or ANXA10 knockout. *P < 0.05, compared with the NC group

Venturing deeper into the mechanistic underpinnings, we probed the expression levels of proteins pivotal to the G1/S–phase checkpoint of the cell cycle. Our findings revealed that KRT16 suppression led to a decline in the levels of cyclin D1, CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 (Fig. 5G). In contrast, ANXA10 knockdown manifested a marked reduction in cyclin E, CDK2, and CDK6. Such marked reduction was absent in cell lines that underwent simultaneous knockdown of both KRT16 and ANXA10. These findings suggested that KRT16 and ANXA10 might be instrumental in modulating the expression of key regulatory proteins at the G1/S checkpoint of the LUAD cell cycle. Meanwhile, this study examined the ability of KRT16 and ANXA10 to influence tumorigenesis in model animals. The results showed that KRT16 or ANXA10 knockout cell lines had weaker tumorigenic capacity than normal control cells, were smaller in size, and weighed less (Fig. 5H).

Discussion

An in-depth analysis of the transcriptome data from our collected surgical samples pinpointed the top 20 genes exhibiting significant expression disparities as potential regulators in lung cancer. By juxtaposing these findings with the TCGA dataset, we further narrowed down to eight genes, which demonstrated a strong association with lung cancer survival and prognosis. In this study, 18 of the top 20 DEGs in surgical samples showed the same expression trend in TCGA, which was expected. The reasons for the inconsistencies may be as follows: (1) individual differences among tumor patient samples; (2) The heterogeneity of tumor tissue itself; (3) Different transcriptome sequencing technology platforms and batch effects; (4) Differences in data processing methods and details during processing. At the same time, we also verify the result. Subsequent validation using qPCR and Western blotting established KRT16 and ANXA10 as potential regulators in LUAD. We modulated the cellular expression levels of KRT16 and ANXA10 to explore their roles in LUAD. Our findings highlighted that KRT16 and ANXA10 were intricately linked to both the proliferation and cell cycle dynamics of LUAD.

KRT16 is an intermediate filament protein that is crucial in epithelial tissue structure and function. Its association with various cancers, especially in contexts deviating from healthy epithelial cells, has attracted increased attention in cancer research [15, 16]. KRT16 has been linked with both heightened and diminished expression in different malignancies, suggesting its multifaceted role in cancer progression [15, 17, 18]. Our study focused on understanding the role of KRT16 in lung cancer through in-depth data analysis and molecular exploration. An interesting result is that we have found that several KRT family proteins were related to the occurrence and development of LUAD and the prognosis of LUAD patients, including not only KRT16, but also KRT6A and KRT16, and these three are also highly correlated in the PPI network. The KRT protein family plays an important role in lung cancer. Studies have shown that specific KRT gene expression is strongly associated with the prognosis of patients with lung cancer [19]. For example, KRT8 is independent risk factors for LUAD prognosis, and their high expression is associated with poor prognosis in patients [20]. In addition, in lung cancer, by reducing the level of carcinogenic KRT7 and stabilizing PTEN protein, it plays a role in tumor inhibition and enhancement of apoptosis [21]. At present, relevant drugs have been developed.

Another gene, ANXA10, a newer member of the Annexin family, is recognized for its potential association with tumorigenesis [22]. Annexins are calcium- and phospholipid-binding proteins involved in numerous cellular activities, including growth and differentiation [23]. The varied expression of ANXA10 across different cancers points to its complex role in oncology [24–26]. Although some cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma show a negative correlation with the expression of ANXA10, others such as colorectal cancer demonstrate an opposite pattern [27]. Further research is needed to decipher the precise role of ANXA10 in cancer progression.

Our study delved into the roles of KRT16 and ANXA10 in LUAD. Our initial steps involved establishing the differential expression of these genes between lung cancer and para-cancer tissues. We used transcriptomic data complemented by cellular mRNA and protein expression validation, and discerned an elevated expression of KRT16 and ANXA10 in lung cancer tissues compared with their noncancerous counterparts. This discovery postulated that KRT16 and ANXA10 might play a role in the development and progression of LUAD. We modulated the expression of these genes in the lung cancer cell lines A549 to further elucidate their roles. This intervention led to a marked reduction in their expression. A comparison of the tumorigenic properties across cells with varied KRT16 expression levels revealed that KRT16 and ANXA10 suppression manifested in reduced proliferation and decelerated cell cycle progression. This suggested that attenuating KRT16 expression could potentially mitigate the aggressive phenotypes typical of LUAD cells. Building on these findings, we proceeded to examine the protein expression dynamics of KRT16 and ANXA10 as pivotal proteins at various cell cycle checkpoints. Our results indicated that diminished KRT16 expression influenced the G1/S transition of the cell cycle, specifically by modulating the levels of cyclin D/CDK2/CDK6. Concurrently, both ANXA10 and KRT16 appeared to orchestrate the cell cycle arrest by impacting the cyclin E/CDK4 expression. Cyclin D1 and cyclin E collectively oversaw the G1/S–phase checkpoint [28]. This checkpoint was instrumental in dictating the transition of cells from the G1 phase to the S–phase of the cycle. Drawing from these insights, we postulated that KRT16 and ANXA10 might offer a promising therapeutic avenue for LUAD by fine-tuning their expression dynamics. However, our study, constrained by technological capacities, did not penetrate the deeper mechanistic interplays involving these genes. Hence, mechanistic investigations remain a future endeavor to holistically comprehend the roles of KRT16 and ANXA10 in LUAD.

This study had the following limitations. First, the sample size of RNA-seq data in this study was small. While using the TCGA data, the differences in the clinical characteristics between TCGA and self-sequencing samples in this study were not considered, leading to bias in results. Second, this study did not functionally validate all DEGs analyzed from the RNA-seq data and TCGA, and the screening process resulted in the loss of potentially important genes. Future studies should focus on the molecular mechanisms of KRT16 and ANXA10.

Conclusions

In our study, a combination of transcriptome sequencing from surgical specimens, TCGA data exploration, and mRNA and protein expression analysis in cell lines highlighted KRT16 and ANXA10 as potential pivotal factors in the progression of LUAD. Furthermore, our findings suggested that KRT16 and ANXA10 could modulate the cell cycle in lung cancer cells, particularly through interactions with checkpoint proteins during the G1/S–phase transition. These insights position KRT16 and ANXA10 as promising therapeutic targets for LUAD.

Author contributions

WL: designed the work; acquisition analysis; interpretation of data; wrote the draft manuscript. JS: acquisition analysis; interpretation of data; RZ: designed the work; acquisition analysis; XF: designed the work; acquisition analysis; interpretation of data; revised the manuscript.

Funding

Anhui Provincial Health Research Project Qilu Cancer Special Project (AHWJ2023BAa20005). Bethune-qiyin Future Multidisciplinary Research Capacity Building Project (BFC-QYWL-QL-20240905-01). Natural Science Foundation project of Anhui Province (2308085MH237). Colleges and Universities Provincial Natural Science Research Project of Anhui (2023AH053315). Research Fund of Anhui Institute of translational medicine (2022zhyx-C22).

Data availability

RNA-sequencing data were deposited into the National Genomics Data Center under accession number PRJCA032466.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was in agreement with the statements of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University University Ethics Committee (No. 2023041). All patients have signed informed consent forms.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wen-jian Liu, Email: liuwenjian85@126.com.

Ren-quan Zhang, Email: zhangrenquan@live.cn.

Xiao-yun Fan, Email: xiaoyunfan@ahmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osmani L, et al. Current WHO guidelines and the critical role of immunohistochemical markers in the subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC): moving from targeted therapy to immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2018;52(Pt 1):103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thai AA, et al. Lung cancer. Lancet. 2021;398(10299):535–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lahiri A, et al. Lung cancer immunotherapy: progress, pitfalls, and promises. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reck M, Remon J, Hellmann MD. First-line immunotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(6):586–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.da Cunha Santos G, Shepherd FA, Tsao MS. EGFR mutations and lung cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:49–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider JL, Lin JJ, Shaw AT. ALK-positive lung cancer: a moving target. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(3):330–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin JJ, Shaw AT. Recent advances in targeting ROS1 in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(11):1611–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reck M, et al. Targeting KRAS in non-small-cell lung cancer: recent progress and new approaches. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(9):1101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada G, et al. Rare molecular subtypes of lung cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2023;20(4):229–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Solomon BJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of first-line lorlatinib versus crizotinib in patients with advanced, ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: updated analysis of data from the phase 3, randomised, open-label CROWN study. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11(4):354–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu Y, et al. Targeting HER2 alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: therapeutic breakthrough and challenges. Cancer Treat Rev. 2023;114: 102520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandrashekar DS, et al. UALCAN: an update to the integrated cancer data analysis platform. Neoplasia. 2022;25:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hnasko TS, Hnasko RM. The western blot. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1318:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, et al. Targeting the KRT16-vimentin axis for metastasis in lung cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2023;193: 106818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zieman AG, Coulombe PA. Pathophysiology of pachyonychia congenita-associated palmoplantar keratoderma: new insights into skin epithelial homeostasis and avenues for treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(3):564–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elazezy M, et al. Emerging insights into Keratin 16 expression during metastatic progression of breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(15):3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuanhua L, et al. TFAP2A induced KRT16 as an oncogene in lung adenocarcinoma via EMT. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15(7):1419–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li G, et al. Keratin gene signature expression drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition through enhanced TGF-beta signaling pathway activation and correlates with adverse prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Heliyon. 2024;10(3): e24549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, et al. KRT8 serves as a novel biomarker for LUAD and promotes metastasis and EMT via NF-kappaB signaling. Front Oncol. 2022;12: 875146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Z, et al. The long non-coding RNA keratin-7 antisense acts as a new tumor suppressor to inhibit tumorigenesis and enhance apoptosis in lung and breast cancers. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(4):293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang X, et al. ANXA10 promotes melanoma metastasis by suppressing E3 ligase TRIM41-directed PKD1 degradation. Cancer Lett. 2021;519:237–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iaccarino L, et al. Anti-annexins autoantibodies: their role as biomarkers of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10(9):553–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, et al. Knockdown of ANXA10 induces ferroptosis by inhibiting autophagy-mediated TFRC degradation in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(9):588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun R, et al. Annexin10 promotes extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma metastasis by facilitating EMT via PLA2G4A/PGE2/STAT3 pathway. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:142–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munksgaard PP, et al. Low ANXA10 expression is associated with disease aggressiveness in bladder cancer. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(9):1379–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, et al. ANXA10 is a prognostic biomarker and suppressor of hepatocellular carcinoma: a bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedroza-Garcia JA, Xiang Y, De Veylder L. Cell cycle checkpoint control in response to DNA damage by environmental stresses. Plant J. 2022;109(3):490–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

RNA-sequencing data were deposited into the National Genomics Data Center under accession number PRJCA032466.