Abstract

The striatum, a core brain structure relevant for schizophrenia, exhibits heterogeneous volumetric changes in this illness. Due to this heterogeneity, its role in the risk of developing schizophrenia following exposure to environmental stress remains poorly understood. Using the putamen (a subnucleus of the striatum) as an indicator for convergent genetic risk of schizophrenia, 63 unaffected first-degree relatives of patients (22.08 ± 4.80 years) with schizophrenia (UFR-SZ) were stratified into two groups. Compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 59), voxel-based and brain-wide volumetric changes and their associations with stressful life events (SLE) were tested. These stratified associations were validated using two large population-based cohorts (the ABCD study; n = 1680, 11.92 ± 0.62 years; and UK Biobank, n = 20547, 55.38 ± 7.43 years). Transcriptomic analysis of brain tissues was used to identify the biological processes associated with the brain mediation effects on the SLE-psychosis relationship. The stratified UFR-SZ subgroup with smaller right putamen had a smaller volume in the left caudate when compared to HC; this caudate volume was associated with both a higher level of SLE and more psychotic symptoms. This caudate-SLE association was replicated in two independent large-scale cohorts, when individuals were stratified by both a higher polygenic burden for schizophrenia and smaller right putamen. In UFR-SZ, the caudate cluster mediated the relationship between SLE and more psychotic symptoms. This mediation was associated with the genes enriched in both glutamatergic synapses and response to oxidative stress. The stratified association between the striatum and stress highlights the differential vulnerability to stress, contributing to the complexity of the gene-by-environment etiology of schizophrenia.

Subject terms: Schizophrenia, Human behaviour

Introduction

Schizophrenia has long been related to glutamatergic dysregulation and disrupted dopaminergic signaling in the striatum following environmental stresses [1]. However, dopamine imaging evidence have observed inconsistent changes at the striatum in individuals at increased genetic risk of schizophrenia [2, 3]. The putamen, a part of the striatum, had both the highest heritability given by a twin study and the strongest genetic associations among all subcortical regions [4]. Given such strong genetic associations, it is plausible to hypothesize that individuals carrying different genetic risks for schizophrenia may have distinct brain vulnerabilities to environmental stresses [5]. Therefore, individuals sharing a common brain vulnerability to environmental stresses may be identified by some stratification of the genetic risks for schizophrenia.

Stressful life events (SLE, e.g., family, work/study, social interaction), as typical environmental risks for schizophrenia [6], have been associated with structural changes in both widespread cortical regions and fewer subcortical regions, such as the hippocampus, caudate [7]. However, individual variability is significant in terms of susceptibility to SLE, as both enlarged [8] or contracted [9] caudate volumes have been reported in patients with posttraumatic stress disorders when compared with healthy controls. As proposed by the differential susceptibility theory, this individual variability indicates certain genetic predispositions rendering some brain structures more vulnerable to environmental stresses [5]. Therefore, stratification for such genetic predispositions might hold the key to the discovery of neural mediators for the gene-by-environment effects in schizophrenia.

Striatal dysfunction is one of the most replicable stress-related mechanisms in schizophrenia pathology [10]. However, increased [11], decreased [12], and nonsignificant changes [13] of the striatal volumes (i.e., caudate, putamen, and nuclear accumbens) have all been reported in patients with schizophrenia when compared with healthy controls. Especially, patients with schizophrenia had greater individual variations in their putamen volumes [14]. Recently, the larger and smaller putamen volumes have been used as neuroimaging markers to define two distinct subtypes of schizophrenia, respectively [15]. Notably, the smaller-putamen volume has also been associated with both higher polygenetic risks [16] and rare genetic risk variants [17] for schizophrenia. This evidence suggests that different putamen volumes might indicate distinct genetic predispositions for schizophrenia. Therefore, stratifying by the putamen volume may be a promising way to uncover the neural mediators for the gene-by-environment effects in schizophrenia.

Another significant source for heterogeneity is the antipsychotic medication, which can change the putamen volume to a notable extent [13], making it difficult to detect these gene-by-environment effects. Compared with health controls (HC), volumetric changes in the unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia (UFR-SZ) are more relevant to genetic risks for schizophrenia. They not only share similar genetic predispositions for this disorder as the patients, but also are free of antipsychotic drugs. Therefore, the gene-by-environment effects might be better identified by examining the environmental effects on the volumetric changes in UFR-SZ.

Given the decreased putamen volume reported in the adolescent offsprings of schizophrenia [18] and in the clinical high-risk for schizophrenia [19], we hypothesized that in UFR-SZ, a lower putamen volume indicating certain genetic predisposition renders brain structures more vulnerable to SLE, and some of this risk could be intrinsic, affecting other parts of the striatum per se. To test this hypothesis, we stratified UFR-SZ participants (n = 63) by their putamen volumes. Compared with healthy controls (HC; n = 59), we tested for significant volumetric changes in each subgroup group and their associations with SLE. Next, we validated these associations using two large population-based cohorts of healthy children (n = 1680) and middle-to-old individuals (n = 20,547). Finally, we tested whether the mediation effects of these significant volumetric changes on the stress-symptom relationships were associated with biological processes relevant to oxidative stress by a transcriptomic analysis using brain tissues [20].

Methods and materials

Participants

This study included 63 unaffected first-degree relatives of schizophrenia (UFR-SZ) and 59 healthy controls (HCs) matched with the age, self-reported gender, and years of education. All UFR-SZ subjects are family members of schizophrenia patients from the wards of the Second Xiangya Hospital, in Changsha, Human, China. They have at least one first-degree relative who met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. The patients themselves were not recruited in this study, considering the complex medicine use, disease duration (i.e., first-episode and chronic schizophrenia), and large age range (i.e., parents, children, siblings) of the schizophrenia patients in the UFR-SZ family. Besides, 59 HCs were recruited via advertising in the local media. The ones who did not have a personal history of DSM-IV Axis I disorder themselves or among their first- to third-degree relatives were included. Both UFR-SZ and HC participants were 13 to 35 years old, right-handed, Han Chinese with gender and age matched. They were excluded if they met any one of the following criteria: any history or current psychiatric disorder, mental retardation, major somatic disease, or head injury resulting in a sustained loss of consciousness for over 5 min. Data on substance use (i.e., the use of alcohol, tobacco, and hormonal drugs) was collected, and the sum score was recorded.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in this study during recruitment. This study was in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital (No. S009, 2018).

Measures

In the UFR-SZ, the Structured Interview for the prodromal syndrome (SIPS) was assessed for symptoms, including positive, negative, disorganization and general symptoms [21]. The SLE were measured by the life event scale [22] to evaluate the environmental stress suffered by all participants within the 1-year period before participation (Supplementary Method S1). Three common cognitive functions that are usually impaired in schizophrenia were assessed by Certain parts of MATRICS™ Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB™) in all participants within 24 h around the MRI scan [23], including the Revised Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT), Trail Making Test (TMT), and Continuous Performance Test (CPT) [24]. As recommended in the literature, total recall score (sum of the words recalled in trials 1, 2, and 3, i.e., HVLT123) and delayed recall score (the number recalled in 20 min, i.e., HVLT memory) in HVLT, time taken to complete TMT part A and B (i.e., TMT-A, TMT-B) in TMT and average response time (i.e., visual and auditory average) in CPT were used in the current study.

Structural imaging acquisitions

For each participant, MRI scans were acquired on a Siemens 3.0 T magnetic resonance imager equipped with a 16-channel head coil located in the Magnetic Imaging Centre of Hunan Children’s Hospital, Changsha, China. Participants were asked to stay awake with eyes closed, and foam pads and earplugs were used to minimize head motion and noise. structural images were obtained using a T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo sequence with TE = 2.33 ms; TR = 2530 ms; slice number = 192; voxel size = 1 × 1 × 1 mm3; flip angle = 7°; FOV = 256 mm.

Volume-based morphometry analysis

Using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox 12 (CAT12: Version 12.8) in Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM12: Version 7487), volume-based morphometry analysis was applied to detect the brain volume alterations in UFR-SZ relative to HCs. Before the T1 preprocessing, all images were visually checked, and no image of bad quality (i.e., obvious motion or artifacts) was excluded. The T1 images were preprocessed by the standard procedures recommended in CAT12, including bias-field corrected to control the effects of MRI inhomogeneities, transformed by the affine registration, normalized using the DARTEL algorithm at the voxel size of 1.5 mm3, and then segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) using tissue probability maps. The modulated gray matter segmentations were smoothed at FWHM = 6 mm before further statistical analysis.

Validation datasets

After quality control, we found 1680 adolescents had the T1-weighted images, SLE assessments, and SZ-PRS scores at the 2-year follow-up in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study (release 5.0; aged 11.92 ± 0.62 years, 55% males; white ethnicity). The T1-weighted images were collected from 21 imaging centers and preprocessed by the standard procedures in CAT12, and smoothed at FWHM = 8 mm [25]. As used by the literature [26], SLE was measured by the total score of the posttraumatic stress disorder subscale, including 17 items for various traumatic events in the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. More details are provided in Supplementary Method S2.

In UK Biobank (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/), we also used the T1-weighted images, SLE assessments, and SZ-PRS scores of 20547 individuals (aged 55.38 ± 7.43 years, 45.69% male proportion; white British ethnicity). The T1-weighted images were collected from four imaging centers and preprocessed by the same procedure described above. Following the literature [27], SLE was measured by the total score of five adulthood traumatic events, including physical violence by partner, belittlement by partner or ex-partner, sexual interference by partner or ex-partner without consent, not being in a confiding relationship or not able to pay rent/mortgage. More details are provided in Supplementary Method S3.

Statistics

Group difference analyses

Group comparisons for the environmental and cognitive variables were conducted by either two-sample tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) while controlling for age, gender, and years of education. Multiple comparisons were corrected by the FDR q < 0.05. When examining the group difference in the structural neuroimaging features (i.e., gray matter volume), the total intracranial volume (TIV) was also included as covariates except for the age, gender, and years of education. Group comparison of voxel-based morphometry (VBM) was conducted using a two-sample t-test and masked the brain area of comparison in the automated anatomical labeling atlas 3 without the cerebellum while controlling for age, sex, years of education, and TIV. Clusters with significant group differences were identified by the Gaussian random field (GRF) correction with a voxel-wise p < 0.001, a cluster-wise p < 0.05, and a cluster size >30.

Associations of the volume extracted from each significant cluster with the psychotic symptom scores (i.e., the SIPS), the general functioning score (i.e., the GAF), the environmental stress scores (i.e., the SLE), and the cognitive test scores (i.e., the HVLT, CPT, and TMT) were estimated by the partial Spearman correlation with the same covariates as described above. Multiple comparisons were corrected by the FDR q < 0.05.

Group stratification by the putamen

To test the hypothesis that a subgroup of the UFR-SZ participants might be particularly vulnerable to the SLE, we divided them into different subgroups according to the volumes of left or right putamen separately, based on their role in being neuroimaging makers for subtypes in schizophrenia [15, 16]. For each stratification, the UFR-SZ group was divided into two subgroups using the median volume of given lateral putamen in the HC group, i.e., the above- and the below-median subgroups.

For the subgroups separated above, we first tried to locate the brain clusters significantly differing from those in the health controls while overlooking clusters within the brain areas used for subgroup generation., and then tested the associations of these clusters with both the SLE and the psychotic symptoms. Specifically, considering the same set of covariates and significance as described above, a VBM comparison was conducted in each subgroup of UFR-SZ with HC. The associations of the significant clusters with both the symptom scores and life event scores were assessed by the same partial Spearman correlation with FDR correction as described above. Finally, we tested whether the associations between the SLE and the psychotic symptoms were mediated by the volumes of the significant clusters in this subgroup using the Mediation toolbox with 3000 bootstraps for significance (https://github.com/canlab/MediationToolbox).

Independent validations in the ABCD and the UK Biobank

Brain clusters (identified in above UFR-SZ) that associated with SLE or psychotic symptoms were applied as brain masks to calculate whether same stress-volume or stress-symptom connection remained existed in ABCD adolescents and individuals in UK Biobank. Using cutoffs (i.e., both the median of SZ-PRS and the median of volume of the right putamen) to define individuals with higher genetic risk for SZ and smaller volume of the right putamen, who were comparable to the below-median subgroup of UFR-SZ, we investigated whether there were vulnerable individuals in the ABCD cohort and in UK biobank. Using the lm-function in R (version 4.2.1), a linear model was applied to investigate the correlation between SLE and volumes while accounting for age, sex, site, and TIV.

Gene enrichment analysis

Gene expression data of the brain from the Allen Human Brain Atlas (AHBA, http://www.brain-map.org) were analyzed here. Consistent with the procedures in our previous study [28], AHBA preprocessing pipeline included the reannotation, data filtering, probe selection and normalization except for the difference that 2583 samples from the whole brain were applied here. Partial least square (PLS) regression was conducted to find the gene expressions that were spatially correlated with the mediation effects of voxel-level volume for the association between SLE and the total SIPS score in the brain. The significance of PLS components were identified by 1000 permutations (p < 0.05) and were transformed to Z statistics using 1000 bootstraps. Gene enrichment analysis was performed based on the Human Molecular Signatures Database (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/) and conducted for the gene sets with significant positive (Z > 3) and negative (Z < −3) using FDR cutoff of 0.05. The significant enrichments were confirmed by applying a more stringent threshold (i.e., genes ranked top or bottom 1%).

Results

Demographics, environmental, cognitive, and volume statistics

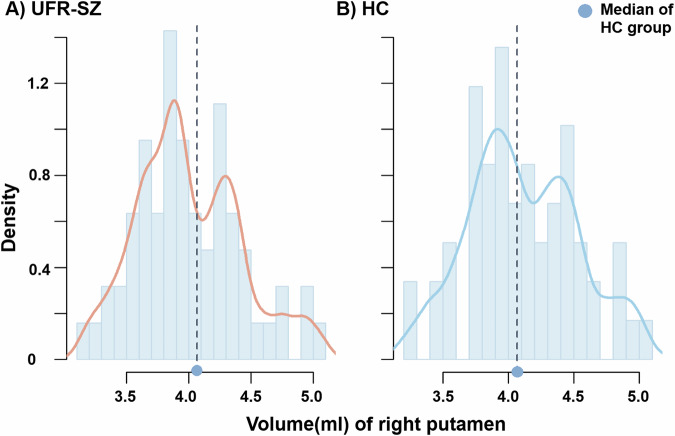

The UFR-SZ participants (of whom 35 were females; mean[SD] age 22.08[4.86] years) showed matched age, gender, and years of education with HCs (of whom 26 were females; mean[SD] age 21.17[3.28] years; Table 1). Seven of 63 UFR-SZ and nine of 59 HCs reported at least one use of the above substances. The UFR-SZ participants had suffered more SLE than HCs (F1, 117 = 4.482, p = 0.036) and had impaired memory in the HVLT (F1, 119 = 12.287, p < 0.001) and slower response in the TMT-B (F1, 119 = 3.923, p = 0.050). Volume-based morphometric analysis showed larger brain volume in UFR-SZ than HC, including the frontal area (i.e., orbital and superior frontal cortex), precuneus, inferior occipital, and temporal cortex as presented in Supplementary Table S1. No significant association between these clusters and behavioral, environmental stress, or cognitive score (i.e., SIPS, SLE, or HVLT) was identified in UFR-SZ. Two separate peaks existed in the distribution of right putamen volume among UFR-SZ (Fig. 1), but not in left putamen (Supplementary Fig. S1). In the following analysis, UFR-SZ were stratified by the median volume of the right putamen while using the stratification of the left putamen as a contrast.

Table 1.

Demographics and behavioral characteristics of the sample.

| UFR-SZ patients | HCs | T/χ2/F | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Subjects (Female) | 63(35) | 59(26) | 1.182 | 0.277 | ||

| Age | 22.08 | 4.86 | 21.17 | 3.28 | 1.203 | 0.231 |

| Education (year) | 13.35 | 3.16 | 14.36 | 2.74 | −1.875 | 0.063 |

| Substance use | 0.29 | 0.87 | 0.34 | 0.76 | −0.360 | 0.720 |

| TIVa | 1458.36 | 127.75 | 1472.44 | 128.81 | 0.001 | 0.979 |

| Gray matterb | 700.31 | 61.84 | 699.29 | 62.93 | 2.458 | 0.120 |

| White matterb | 500.32 | 54.31 | 505.25 | 52.39 | 0.001 | 0.973 |

| Cerebrospinal fluidb | 257.73 | 45.11 | 267.89 | 48.16 | 1.466 | 0.228 |

| Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndrome | ||||||

| Total | 4.03 | 5.48 | / | / | / | / |

| Positive | 0.79 | 1.23 | / | / | / | / |

| Negative | 1.60 | 3.11 | / | / | / | / |

| Disorganization | 0.63 | 0.96 | / | / | / | / |

| General | 1.02 | 1.48 | / | / | / | / |

| Global Assessment of Functioning | 84.15 | 6.21 | / | / | / | / |

| Stressful life event scalea | 18.97 | 24.97 | 8.86 | 14.81 | 4.482 | 0.036* |

| HVLT123a | 24.90 | 3.84 | 27.98 | 3.90 | 5.489 | 0.021*# |

| HVLT memorya | 9.13 | 1.96 | 10.43 | 1.66 | 12.287 | <0.001***# |

| TMT task performancea | ||||||

| TMT-A time (s) | 37.80 | 19.73 | 31.91 | 9.56 | 0.425 | 0.516 |

| TMT-B time (s) | 104.57 | 65.63 | 80.98 | 35.15 | 3.923 | 0.050* |

| Continuous Performance Taska | ||||||

| Visual average (ms) | 866.03 | 130.30 | 834.11 | 40.25 | 1.089 | 0.299 |

| Auditory average (ms) | 865.68 | 42.24 | 883.38 | 125.93 | 2.928 | 0.090 |

HVLT revised Hopkins verbal learning test, TMT trail making test.

*p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, #p value survived FDR correction.

aComparison controlled for age, gender, and years of education.

bComparison controlled for age, gender, years of education, and total intracranial volume (TIV).

Fig. 1. Distribution of the right putamen volume.

A Whole UFR-SZ group. B HC group. Dotted line represented the median volume of the right putamen among the HC group. UFR-SZ unaffected first relatives of patients with schizophrenia, HC healthy controls.

Volumetric changes and environmental, psychiatric connection in the below- and above-median subgroups of UFR-SZ

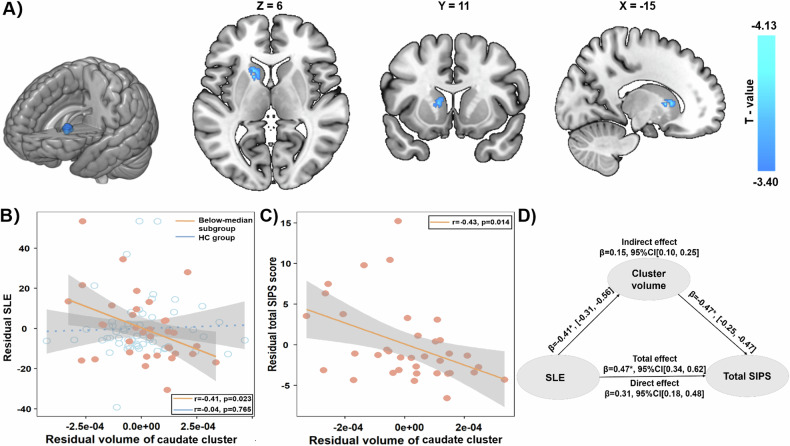

In the subgroup with smaller right putamen, namely the below-median subgroup, the volume was reduced in one cluster in the left caudate after the GRF correction (220 voxels; T = −4.13, p < 0.001 at the peak voxel [−15, 11, 6]; Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the lower volume of the cluster in the left caudate was associated with more SLE (r = −0.41, p = 0.023, n = 36; Fig. 2B) and more psychotic symptoms (i.e., higher total SIPS score, r = −0.43, p = 0.014, n = 37; Fig. 2C) in the subgroup with smaller right putamen. As hypothesized, the association with the SLE in the subgroup with smaller right putamen was significantly stronger than in the HC group (the caudate cluster: z = −1.77, p = 0.038, one-tailed, Fig. 2B). Moreover, the volume of the caudate cluster mediated the association between SLE and the total SIPS score (Fig. 2D). These results were not affected by the substance use, i.e., significant associations between the volume of caudate cluster and SLE (r = −0.41, p = 0.026, n = 36) and SIPS (r = −0.43, p = 0.015, n = 37) as well as the significant mediation effect. After the above stratification by right putamen, memory function (i.e., HVLT) remained significantly deficient in the below-median subgroup only (Table 2). The volume of the caudate cluster in the below-median subgroup of UFR-SZ was smaller when compared with both the whole group of HC (Cohen’s d = −1.121 with 95%CI = [−1.567, −0.675]) and the below-median subgroup of HC (d = −0.643 with 95%CI = [−1.146, −0.140]). Meanwhile, none of the group-difference clusters in the above-median subgroup of UFR-SZ had any significant association with either SIPS or SLE (Supplementary Fig. S2 and Table S3).

Fig. 2. Significantly reduced cluster and associations with both SLE and psychotic symptoms in the below-median subgroup of UFR-SZ.

A Volume reduction in a caudate cluster. B Comparison between the associations of the SLE and the caudate cluster in the below-median subgroup of UFR-SZ (in orange) and in the health controls (in blue). C Association between the caudate cluster and the symptom score in the UFR-SZ subgroup. D The mediation effect of the caudate cluster on the association between the SLE and the total SIPS score. Cooler color represents a greater reduction in volume. The below-median subgroup is short for the UFR-SZ subgroup with a smaller right putamen volume. SLE stressful life events, UFR-SZ unaffected first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia, SIPS structured interview for the prodromal syndrome, CI confidence interval.

Table 2.

Comparison among the subgroups of the unaffected first-degree relatives of the patient with schizophrenia and the healthy controls.

| Above-median (n = 26) | Below-median (n = 37) | HCs (n = 59) | F value | P value | Post hoc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Age | 21 | 4.82 | 22.84 | 4.82 | 21.17 | 3.28 | 2.24 | 0.111 | |

| Subjects (female) | 26(7) | 37(28) | 59(26) | 16.13 | <0.001***# | ||||

| Education(year) | 12.81 | 3.42 | 13.73 | 2.95 | 14.36 | 2.74 | 2.51 | 0.086 | |

| Intracranial volumea | 1554.07 | 89.39 | 1391.11 | 106.26 | 1472.44 | 128.81 | 7.64 | <0.001***# | Above median >Below-median (p < 0.001)#, Above median >HCs(p = 0.047) |

| Gray matterb | 753.12 | 47.91 | 663.20 | 39.52 | 669.29 | 62.93 | 4.76 | 0.010*# | Above median > Below-median (p = 0.026), Above median >HCs(p = 0.012)# |

| White matterb | 537.55 | 42.11 | 474.15 | 46.30 | 505.25 | 52.39 | 0.41 | 0.663 | |

| Cerebrospinal fluidb | 263.40 | 34.85 | 253.76 | 51.21 | 267.89 | 48.16 | 4.19 | 0.018*# | Above median < Below-median (p = 0.027), Above median <HCs(p = 0.027) |

| Structured interview for prodromal syndromea | |||||||||

| Total | 4.81 | 6.11 | 3.47 | 4.99 | / | / | 1.03 | 0.314 | |

| Positive | 1.19 | 1.55 | 0.50 | 0.85 | / | / | 2.78 | 0.101 | |

| Negative | 1.81 | 3.27 | 1.44 | 3.02 | / | / | 0.28 | 0.601 | |

| Disorganization | 0.85 | 1.26 | 0.47 | 0.65 | / | / | 3.64 | 0.062 | |

| General | 0.96 | 1.48 | 1.06 | 1.49 | / | / | 0.01 | 0.905 | |

| GAFa | 82.85 | 7.16 | 85.08 | 5.32 | / | / | 1.44 | 0.235 | |

| Stressful life event scalea | 23.12 | 31.23 | 15.89 | 18.98 | 8.86 | 14.81 | 3.70 | 0.028*# | Above median >HCs(p = 0.021) |

| HVLT123a | 25.50 | 4.13 | 26.19 | 3.65 | 27.98 | 3.90 | 2.76 | 0.067 | |

| HVLT memorya | 9.27 | 2.01 | 9.03 | 1.94 | 10.43 | 1.66 | 6.38 | 0.002**# | Below-median <HCs(p = 0.003)# |

| TMT task performancea | |||||||||

| TMT-A time | 37.30 | 22.47 | 38.16 | 17.87 | 31.90 | 9.56 | 0.21 | 0.810 | |

| TMT-B time | 115.43 | 76.27 | 96.94 | 56.86 | 80.98 | 35.15 | 2.09 | 0.128 | |

| Continuous performance taska | |||||||||

| Visual average (ms) | 872.69 | 177.18 | 861.22 | 84.32 | 834.11 | 40.25 | 0.54 | 0.582 | |

| Auditory average (ms) | 855.71 | 50.39 | 872.51 | 34.75 | 883.38 | 125.93 | 1.46 | 0.236 | |

Above-median, subgroup with a larger right putamen; Below-median, subgroup with a smaller right putamen.

GAF global assessment of functioning, HVLT revised hopkins verbal learning test, TMT trail making test.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, #p value survived FDR correction.

aComparison controlled for age, gender, and years of education.

bComparison controlled for age, gender, years of education, and total intracranial volume (TIV).

In contrast, we also stratified using the left putamen volume. We found that none of the clusters showing a group-difference had any significant association with either SIPS or SLE (Table S4).

Independent validations using the ABCD and UK Biobank cohort

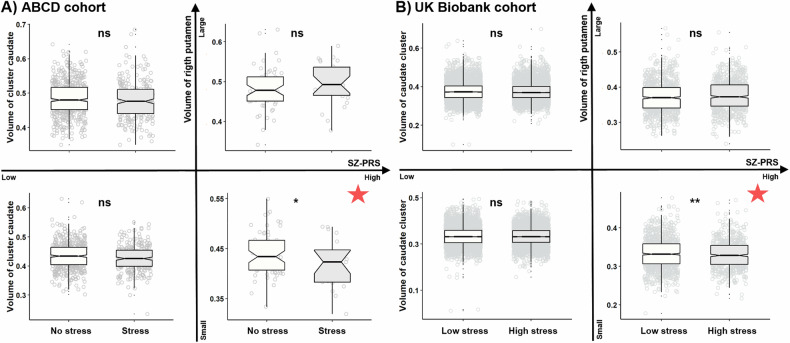

Among 1680 adolescents in the ABCD sample, we found 85 vulnerable individuals, who had both the higher SZ-PRS above the median plus one SD and the below median volume of the right putamen. In this vulnerable group, we found that more experience of SLE was associated with a smaller volume of the caudate cluster (β = −21.327, 95%CI = [−38.938, −3.715], P = 0.018, EV = 38.73%, Fig. 3A). To exclude the potential effect of psychotic experiences on the caudate volume, among 1480 adolescents in the ABCD sample without psychotic syndromes (i.e., severity score <6) [29], we found 75 vulnerable individuals. We replicated the above SLE-volume association in the vulnerable group (Supplementary fig. S3).

Fig. 3. Comparisons of the caudate cluster’s volume between individuals exposed to lower and higher SLE in different groups.

A Adolescents in the ABCD cohort were divided into four groups by the higher/lower SZ-PRS and larger/smaller right putamen volume. For each group, the caudate cluster’s volume was compared between individuals with (Stress) and without SLE (No stress). B Individuals in UK Biobank cohort were divided into the similar four groups. For each group, the caudate cluster’s volume was compared between individuals with the below-median (Low stress) and above-median SLE (High stress). SLE stressful life events, SZ-PRS polygenetic risk score for schizophrenia, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ns non-significant, the red star indicates the vulnerable group.

Among 20547 middle-to-old aged adults in UK Biobank, 1631 vulnerable individuals were identified. Again, in this vulnerable group, more experience of SLE was associated with a smaller volume of the caudate cluster (β = −0.0009, 95%CI = [−0.0015, −0.0002], P = 0.009, 1000 times permutation test, EV = 12.95%, Fig. 3B and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Oxidative stress-related biological processes associated with the mediation effects in the below-median subgroup

Our transcriptomic analysis of the brain mediation effects on the SLE-psychosis relationship (Supplementary Figs. S5, S6) showed more stress-related and glutamine-related pathways in the subgroup with smaller right putamen (stress-related, 37 pathways; glutamine-related 21 pathways, Z > 3 or Z < −3) as compared with the subgroup with larger right putamen (stress-related, 8 pathways; glutamine-related 9 pathways, |Z| > 3) (Supplementary Table S5, 6). Specifically, in the subgroup with smaller right putamen, we identified (1) stress-related pathways, including response to oxidative stress, cell death in response to oxidative stress, etc., and (2) glutamine-related pathways, including the glutamate receptor signaling pathway, synaptic transmission glutamatergic, etc. (Supplementary Table S5).

When the significant gene sets were more strictly restricted to the top 1% genes, the response to oxidative stress (GO:0006979) pathway was still enriched for only the positive gene set in the smaller-putamen group (adjust p = 0.004; Supplementary Table S7, 8).

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed a large sample of genetic, environmental, neuroimaging, and symptom data (N = 22349). We discovered that a left caudate cluster was more vulnerable to stressful life events only when UFR-SZ had a smaller right putamen volume, which is not the case when UFR-SZ was considered as a whole group. Notably, this finding was replicated in both adolescents from the ABCD cohort and middle-to-old adults from the UK Biobank. Furthermore, the left caudate cluster mediated the association between the SLE and psychotic symptoms, and this brain mediation effect was associated with biological pathways, including oxidative stress response and glutamatergic signaling. These findings highlight the importance of neuroimaging-based stratification to identify the mediators of the gene-by-environment interactions in the etiology of schizophrenia [30].

The current finding indicates a role for the genetic risk for schizophrenia to be mediated via smaller right putamen. In prior studies, smaller putamen has been associated with rare genetic risk variants for schizophrenia [17, 31], while the larger putamen has been associated with a common genetic risk variant [32]. These previous findings have suggested that the putamen volume may have the potential to serve as a neuroimaging stratifier to indicate differential genetic risks for schizophrenia. In the current study, we have shown that stratifying by the right putamen volume can identify a subgroup of UFR-SZ sharing a common brain vulnerability in response to stressful life events. This finding is well-supported by the prior work implicating right putamen, but not left putamen, in the poor outcomes of schizophrenia [33], while its enlargement is predictive of improved antipsychotic treatment response in drug-naive schizophrenia [34]. It is possible that the larger putamen could be an indicator of a compensatory mechanism to the genetic risk under environmental stress [35], therefore no association with the psychotic symptoms was identified.

The current findings uncovered a caudate pathway for the two-hit theory of schizophrenia among individuals with both high genetic risk and smaller right putamen volume. It has long been theorized that environmental stresses working on genetic predispositions of schizophrenia sensitize the dopamine system, especially in the striatum [36]. However, in previous PET studies, the findings of both elevation [37] and no elevation [38] of the striatum dopamine synthesis capacity have been reported in patients with schizophrenia as compared with healthy controls. It is reasonable to hypothesize that this inconsistency might be owing to the comorbid addiction [39] and the genetic heterogeneity in schizophrenia [40], different subsets of the genetic risk factors carried by different individuals may cause distinct vulnerabilities of the striatum in response to environmental stresses. This hypothesis is supported by the current finding of the caudate cluster and its replications in two independent, large-scale, and population-based samples. Notably, our transcriptomic findings of the biological pathways related to the responses to oxidative stress provide new evidence supporting the key role of oxidative stress in the pathophysiological mechanism of schizophrenia [41]. Oxidative stress has reciprocal interactions with the dopaminergic system, a key player in schizophrenia [42]. The regulation of the oxidative stresses by the genes, such as the glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), that has been associated with dystrophic axons in putamen [43] and its lower expression levels have been reported in schizophrenia as compared with health controls [44]. Post-mortem studies have reported reduced glutathione levels, a biomarker of oxidative stress [45], in the brains of schizophrenic patients, especially in caudate [46].

Alternatively, the right putamen volume might be a collider for the apparent caudate-environment or caudate-symptom associations after the stratification. For example, there might be no associations between the caudate volume and the SLE, but both had influences on the putamen volume. Therefore, restricting the analysis within the individuals with smaller-putamen volume might bring artifact association between the caudate volume and the SLE. To test this alternative explanation, we conducted a Bayesian network analysis [47] for four variables, including the psychotic symptoms, the SLE, the right putamen volume, and the volume of the left caudate cluster. After 1000 bootstraps, we found no evidence for the right putamen as a collider variable in either the caudate-environment or the caudate-symptom relationships, i.e., no V structure in the resulting network (Supplementary Fig. S7).

In summary, the current study of individuals with genetic high risk for schizophrenia discovered a caudate pathway linking the environmental stress to the psychotic symptoms in a subgroup characterized by smaller putamen.

Limitations

The current study also has some limitations. First, given the high heterogeneity in schizophrenia, the current findings need to be validated in future multicenter studies with larger sample sizes of UFR-SZ. Second, future studies with a follow-up design are needed to test if the identified environment-caudate-symptom pathway can predict the risk of receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Third, cerebellum was not included in our group comparison of voxel-based morphometry, future analysis will consider the cerebellum given its possible role in psychiatry [48]. Fourth, many types of life events (i.e., sexual abuse, physical abuse, psychological abuse, hurt or death of family member, parental discord, tensions at work) were examined in this study, however, other SLEs (social exclusion, discrimination, or migration) [49] were needed to complete our analysis [50]. Fifth, individuals with familial risk of schizophrenia were analyzed to avoid the effects of antipsychotics and illness, further study enrolled fist-episode schizophrenia was essential to test the concrete effects of SLEs on brain.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was partially supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFE0191400 and 2023YFE0109700), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82272079 and 81871056, 82401769), the Program of Shanghai Academic Research Leader (No. 23XD1423400), and the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (No.s: 2018SHZDZX01 and 2021SHZDZX0103), and University of Sydney-Fudan University BISA Flagship Research Program, the Scientific Research Launch Project for new employees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Validation analysis in the UK Biobank was conducted under the UK Biobank application number 19542. The ABCD Study is supported by the National Institutes of Health and additional federal partners under award numbers U01DA041022, U01DA041028, U01DA041048, U01DA041089, U01DA041106, U01DA041117, U01DA041120, U01DA041134, U01DA041148, U01DA041156, U01DA041174, U24DA041123, and U24DA041147. A full list of supporters is available at https://abcdstudy.org/federal-partners.html. A listing of participating sites and a complete listing of the study investigators can be found at https://abcdstudy.org/consortium_members/. ABCD consortium investigators designed and implemented the study and/or provided data but did not necessarily participate in the analysis or writing of this report. This manuscript reflects the views of the authors and may not reflect the opinions or views of the NIH or ABCD consortium investigators. The ABCD data repository grows and changes over time. The ABCD data used in this report came from the Data Release 5.0 (10.15154/8873-zj65). An NDA study 10.15154/4n6r-cf27 has been created for the data used in this report. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Author contributors

QL and YH conceptualized the study; XM and NF analyzed the data; QL, LP, XC, YH, and JF interpreted the findings; LC, ZG, XC, LY, LO, YW, CL, JK, JF, and YH contributed to the acquisition and preprocessing of the data; XM, NF, LP, YH, and QL drafted the manuscript; All authors revised it critically for important intellectual content.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, QL, upon reasonable request with proposal. The Matlab and R codes of this study are available at https://github.com/Fengnanahub/Stratify-UFR-by-PutamenVol.git.

Competing interests

There is no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. LP acknowledges research support from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded to the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University (through New Investigator Supplement to LP); Monique H. Bourgeois Chair in Developmental Disorders and Graham Boeckh Foundation (Douglas Research Centre, McGill University) and salary award from the Fonds de recherche du Quebec-Sante ´ (FRQS).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Xiaoqian Ma, Nana Feng, Lena Palaniyappan.

Contributor Information

Ying He, Email: yinghe@csu.edu.cn.

Qiang Luo, Email: qluo@fudan.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41398-025-03237-2.

References

- 1.Stilo SA, Murray RM. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Owen MJ, Murray RM. The role of genes, stress, and dopamine in the development of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:9–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radua J, Schmidt A, Borgwardt S, Heinz A, Schlagenhauf F, McGuire P, et al. Ventral striatal activation during reward processing in psychosis: a neurofunctional meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibar DP, Stein JL, Renteria ME, Arias V, Alejandro D, Sylvane, Jahanshad N, et al. Common genetic variants influence human subcortical brain structures. Nature. 2015;520:224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Belsky J. Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Int J Child Care Educ Policy. 2013;7:15–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sideli L, Murray RM, Schimmenti A, Corso M, La BD, Trotta A, et al. Childhood adversity and psychosis: a systematic review of bio-psycho-social mediators and moderators. Psychol Med. 2020;50:1761–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holz NE, Zabihi M, Kia SM, Monninger M, Aggensteiner P, Siehl S, et al. A stable and replicable neural signature of lifespan adversity in the adult brain. Nat Neurosci. 2023;26:1603–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Looi JCL, Maller JJ, Pagani M, Högberg G, Lindberg O, Liberg B, et al. Caudate volumes in public transportation workers exposed to trauma in the Stockholm train system. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2009;171:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sussman D, Pang E, Jetly R, Dunkley B, Taylor M. Neuroanatomical features in soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder. BMC Neurosci. 2016;17:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCutcheon RA, Marques TR, Howes OD. Schizophrenia—an overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okada N, Fukunaga M, Yamashita F, Koshiyama D, Yamamori H, Ohi K, et al. Abnormal asymmetries in subcortical brain volume in schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1460–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haijma SV, Van Haren N, Cahn W, Koolschijn PCM, Hulshoff Pol HE, Kahn RS. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39:1129–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Erp TG, Hibar DP, Rasmussen JM, Glahn DC, Pearlson GD, Andreassen OA, et al. Subcortical brain volume abnormalities in 2028 individuals with schizophrenia and 2540 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:547–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brugger SP, Howes OD. Heterogeneity and homogeneity of regional brain structure in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:1104–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chand GB, Dwyer DB, Erus G, Sotiras A, Varol E, Srinivasan D, et al. Two distinct neuroanatomical subtypes of schizophrenia revealed using machine learning. Brain. 2020;143:1027–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chand GB, Singhal P, Dwyer DB, Wen J, Erus G, Doshi J, et al. Schizophrenia imaging signatures and their associations with cognition, psychopathology, and genetics in the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:650–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ching CR, Gutman BA, Sun D, Villalon RJ, Ragothaman A, Isaev D, et al. Mapping subcortical brain alterations in 22q11. 2 deletion syndrome: effects of deletion size and convergence with idiopathic neuropsychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Leeuw M, Bohlken MM, Mandl RC, Hillegers MH, Kahn RS, Vink M. Changes in white matter organization in adolescent offspring of schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong SB, Lee TY, Kwak YB, Kim SN, Kwon JS. Baseline putamen volume as a predictor of positive symptom reduction in patients at clinical high risk for psychosis: a preliminary study. Schizophr Res. 2015;169:178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palaniyappan L, Sabesan P, Li X, Luo Q. Schizophrenia increases variability of the central antioxidant system: a meta-analysis of variance from MRS studies of glutathione. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:796466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McGlashan T, Miller T, Woods S, Rosen J, Hoffman R, Davidson L. Structured Interview for Prodromal Syndromes. New Haven, CT: PRIME Research Clinic, Yale School of Medicine; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin JY, Huang Y, Su YA, Yu Xin, Lyu XZ, Liu Q, et al. Association between perceived stressfulness of stressful life events and the suicidal risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. Chin Med J. 2018;131:912–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Baade LE, Barch DM, Cohen JD, et al. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:214–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benedict RH, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins verbal learning test–revised: normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen C, Luo Q, Chamberlain SR, Morgan S, Romero R, Du J, et al. What is the link between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disturbance? a multimodal examination of longitudinal relationships and brain structure using large-scale population-based cohorts. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;88:459–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bustamante D, Amstadter AB, Pritikin JN, Brick TR, Neale MC. Associations between traumatic stress, brain volumes and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in children: data from the ABCD Study. Behav Genet. 2022;52:75–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yapp E, Booth T, Davis K, Coleman J, Howard LM, Breen G, et al. Sex differences in experiences of multiple traumas and mental health problems in the UK Biobank cohort. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2023;58:1819–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feng N, Palaniyappan L, Robbins TW, Cao L, Fang S, Luo X, et al. Working memory processing deficit associated with a nonlinear response pattern of the anterior cingulate cortex in first-episode and drug-naïve schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:552–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Psychosis risk screening with the prodromal questionnaire—brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129:42–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davis J, Eyre H, Jacka FN, Dodd S, Dean O, McEwen S, et al. A review of vulnerability and risks for Schizophrenia: beyond the two hit hypothesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;65:185–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Warland A, Kendall KM, Rees E, Kirov G, Caseras X. Schizophrenia-associated genomic copy number variants and subcortical brain volumes in the UK Biobank. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:854–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo Q, Chen Q, Wang W, Desrivières S, Quinlan EB, Jia T, et al. Association of a schizophrenia-risk nonsynonymous variant with putamen volume in adolescents: a voxelwise and genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:435–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchsbaum MS, Shihabuddin L, Brickman AM, Miozzo R, Prikryl R, Shaw R, et al. Caudate and putamen volumes in good and poor outcome patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;64:53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li M, Chen Z, Deng W, He Z, Wang Q, Jiang L, et al. Volume increases in putamen associated with positive symptom reduction in previously drug-naive schizophrenia after 6 weeks antipsychotic treatment. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1475–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palaniyappan L. Clusters of psychosis: compensation as a contributor to the heterogeneity of schizophrenia. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2023;48:E325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birnbaum R, Weinberger DR. Genetic insights into the neurodevelopmental origins of schizophrenia. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:727–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumakura Y, Cumming P, Vernaleken I, Buchholz HG, Siessmeier T, Heinz A, et al. Elevated [18F] fluorodopamine turnover in brain of patients with schizophrenia: an [18F] fluorodopa/positron emission tomography study. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8080–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenberg DP, Kohn PD, Hegarty CE, Smith NR, Grogans SE, Czarapata JB, et al. Clinical correlation but no elevation of striatal dopamine synthesis capacity in two independent cohorts of medication-free individuals with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1241–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thompson JL, Urban N, Slifstein M, Xu X, Kegeles LS, Girgis RR, et al. Striatal dopamine release in schizophrenia comorbid with substance dependence. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:909–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brugger SP, Angelescu I, Abi-Dargham A, Mizrahi R, Shahrezaei V, Howes OD. Heterogeneity of striatal dopamine function in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of variance. Biol Psychiatry. 2020;87:215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alameda L, Fournier M, Khadimallah I, Griffa A, Cleusix M, Jenni R, et al. Redox dysregulation as a link between childhood trauma and psychopathological and neurocognitive profile in patients with early psychosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:12495–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steullet P, Cabungcal J, Monin A, Dwir D, O’Donnell P, Cuenod M, et al. Redox dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and NMDA receptor hypofunction: a “central hub” in schizophrenia pathophysiology? Schizophr Res. 2016;176:41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellinger FP, Bellinger MT, Seale LA, Takemoto AS, Raman AV, Miki T, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 is associated with neuromelanin in substantia nigra and dystrophic axons in putamen of Parkinson’s brain. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang D, Wu X, Xue X, Li W, Zhou P, Lv Z, et al. Ancient dormant virus remnant ERVW-1 drives ferroptosis via degradation of GPX4 and SLC3A2 in schizophrenia. Virol Sin. 2024;39:31–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossi R, Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Giustarini D. Oxidized forms of glutathione in peripheral blood as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1406–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murray AJ, Rogers JC, Katshu MZUH, Liddle PF, Upthegrove R. Oxidative stress and the pathophysiology and symptom profile of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:703452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pearl J. Models, Reasoning and Inference. 19. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim M, Leonardsen E, Rutherford S, Selbæk G, Persson K, Steen NE, et al. Mapping cerebellar anatomical heterogeneity in mental and neurological illnesses. Nat Mental Health. 2024:1–12.

- 49.Varchmin L, Montag C, Treusch Y, Kaminski J, Heinz A. Traumatic events, social adversity and discrimination as risk factors for psychosis-an umbrella review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:665957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schiavone S, Colaianna M, Curtis L. Impact of early life stress on the pathogenesis of mental disorders: relation to brain oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:1404–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, QL, upon reasonable request with proposal. The Matlab and R codes of this study are available at https://github.com/Fengnanahub/Stratify-UFR-by-PutamenVol.git.