Abstract

Environmental rules and regulations are essential instruments the government administration uses to control environmental problems in this era of advanced technologies and smooth economic growth. This paper aims to examine how environmental regulations, both mandatory and incentive-based, impact on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in the presence of urbanization, foreign trade, economic growth and energy efficiency (EE) in logistics transportation. The influence of explicating factors on dependent variables, such as the highest, lowest, and mean, is estimated using the quantile regression model. We applied a number of econometric techniques like unit root test, panel co-integration, quantiles regression (CO2), quantiles regression (Energy efficiency), endogeneity test, and finally, we applied the robustness test to verify the results. This research uses quantile regression to estimate the influence of environmental regulations on releasing carbon dioxide and energy efficiency, using panel data of China’s thirty provinces from 2005 to 2019. Environmental policies in the Ningxia, Qinghai, and Hainan provinces impose higher pollution penalties, which significantly impact reducing CO2 emissions. These regions release more environmental regulations, and in the provinces that fall between the 25th and 50th percentiles, mandatory environmental regulations significantly lower CO2 emissions. Incentive environmental regulations regarding the environment have a more significant effect on energy efficiency in the 50th–75th, 75th–90th, and higher 90th percentile groups since these groups have made more significant investments in research and development. Meanwhile, the Yunnan, Heilongjiang, and Xinjiang provinces have higher energy efficiency levels due to mandatory environmental legislation. The results provide the correct information to the government to implement effective environmental regulations to achieve sustainable development goals.

Keywords: Environmental regulations, Economic growth, Environmental regulations, CO2, Energy efficiency, Logistics industry, Urbanization

Subject terms: Environmental sciences, Environmental social sciences

Introduction

China is one of the world’s largest producers of CO2 emissions, having risen to the top of global rankings since 20081. According to data from the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, China emitted a staggering 11.5 billion tons of CO2 in recent years, marking its significant contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions. Given the severity of these environmental impacts, government authorities have implemented environmental regulations as a vital tool for regulating the behavior of production companies and controlling environmental degradation2. These regulations are essential for managing industrial activities that contribute to high pollution levels, including those in energy-intensive sectors like logistics. Without stringent regulatory measures, CO2 emissions could continue to rise unchecked, exacerbating the global climate crisis.

The logistics industry is a critical focus in this context due to its dual role in supporting economic growth and significantly contributing to energy efficiency and CO2 emissions. As the backbone of domestic and international trade, China’s logistics sector has expanded rapidly alongside economic development, making it one of the most energy-intensive industries. This sector’s relevance becomes particularly pronounced when examining the interplay between technological advancements and environmental regulations. Technological innovations, such as energy-efficient transportation systems, automated logistics networks, and smart warehousing, hold immense potential for reducing emissions. However, their adoption is closely tied to the regulatory environment, which influences corporate behavior through mandatory environmental regulations (MERP) and incentive environmental regulations (IER).

Environmental regulations are broadly categorized into two types: mandatory environmental regulations and incentive-based environmental regulations. Each type of regulation affects the logistics industry through distinct mechanisms, with differing implications for energy efficiency (EE) and CO2 emissions. Mandatory environmental regulations impose strict guidelines that companies must adhere to, often through legal requirements or penalties. In contrast, incentive-based regulations offer rewards, such as tax breaks or subsidies, to encourage companies to adopt cleaner technologies or more sustainable practices. This study aims to examine empirically how these two types of environmental regulations impact energy efficiency and CO2 emissions in the logistics industry3. By analyzing both regulatory categories separately, this research provides a clearer understanding of their unique effects. Moreover, based on the empirical findings, this study will propose practical recommendations for policymakers to consider when developing more effective emission reduction strategies.

Previous research on CO2 emissions in the logistics sector offers a strong foundation but also reveals critical gaps. Most studies focus exclusively on how environmental regulations, as a whole, affect CO2 emissions. However, environmental regulations can be divided into mandatory and incentive-based types, each influencing CO2 emissions differently. Analyzing the effects of environmental regulations without distinguishing between these two types may lead to broad conclusions that need more specificity and practical application4. Consequently, this research attempts to fill that gap by dissecting the distinct roles these two forms of regulation play in the logistics industry. It aims to provide more actionable insights for policymakers and industry stakeholders grappling with balancing economic activity with environmental sustainability5.

The research problem in this study revolves around the environmental impact of the logistics sector, specifically its significant contribution to CO2 emissions, and the role of environmental regulations in mitigating these emissions while enhancing energy efficiency (EE). Despite being a vital driver of economic growth (GDP) and urbanization (UN), the logistics sector is also one of the largest sources of carbon emissions. This poses a critical challenge for policymakers and industry stakeholders: balancing the sector’s economic contributions with the urgent need to address its environmental consequences.

The research problem, therefore, lies in understanding the differential impacts of mandatory and incentive-based environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency within the logistics sector. This involves addressing the knowledge gap regarding how these regulatory types influence environmental and energy outcomes across regions with diverse economic and environmental conditions. Focusing on these specific aspects, the study aims to provide actionable insights for developing more nuanced and region-specific environmental policies, ultimately contributing to sustainable development goals. To address these limitations, this study separates environmental regulations into incentive-based and mandatory categories and explores their effects on energy efficiency and CO2, in the logistics sector. The findings are expected to offer strategic insights for government managers and policymakers, helping them design more targeted environmental governance tools. The study also emphasizes the importance of recognizing regional differences when implementing regulatory measures, as the effectiveness of mandatory and incentive-based regulations may vary significantly depending on local economic and environmental conditions.

Conventional econometric methods, such as threshold regression and panel data models, generally need to improve in evaluating the nuanced effects of these regulations on CO2 and EE. These methods are primarily limited to estimating mean impacts, which overlook the diverse and often asymmetric effects that regulations can have at different emissions levels. To overcome this limitation, the present study employs quantile regression techniques, which offer a more robust approach to estimating heterogeneous effects6. Using quantile regression, this research can more accurately capture the varying impacts of mandatory and incentive-based environmental regulations across the spectrum of CO2 and energy EE in the logistics sector. Ultimately, the findings will provide communities and governments with valuable insights, allowing them to develop more focused and influential industrial and environmental policies tailored to the unique challenges of different regions and industries.

Moreover, the effectiveness of these regulatory frameworks can vary depending on their broader approach. Market-based policies, such as emissions trading schemes or carbon taxes, leverage economic incentives to drive compliance, whereas systems-level approaches, including comprehensive planning frameworks or industry-wide energy standards, aim to create structural change. These distinct policy paradigms may yield differential impacts on the logistics sector, requiring a nuanced analysis to understand their relative effectiveness in reducing emissions and improving energy efficiency.

The following sections are included in this document as an extra to the intro. A summary of the research is covered in the following section, model theory and the creation of an empirical model are covered in the third, and empirical findings, including multicollinearity and unit roots tests, are presented in the fourth quantile regression results, cointegration tests, and normality checks. The endogeneity test is presented in the fifth section; the robustness test, the empirical findings, and the underlying causes are covered in detail in the sixth section. The final section contains the conclusions and policy implications.

Literature review

The logistics sector is a vital component of economic development and a significant source of CO2 emissions, contributing to global environmental challenges. Numerous studies have examined the sector’s environmental impact, focusing on how regulations influence CO2 emissions reduction and energy efficiency (EE). For instance7,8, highlights the overall benefits of environmental regulations in reducing emissions. However, most of these studies treat environmental regulations as homogeneous without distinguishing between mandatory and incentive-based approaches9. This lack of differentiation limits their practical applicability in policy design. Furthermore, conventional methodologies, such as panel data models and threshold regression, must capture these regulations’ nuanced and regionally varied effects.

The connection between CO2 emissions from the logistics industry and environmental regulations. Utilizing the generalized second3, discovered that environmental regulations in Southeast Asian nations prompted logistics firms to increase their sustainable energy use. According to10, the logistics industry managed the increase in CO2 emissions by improving its power architecture. Comparably, the examination of EU nations revealed that environmental regulations and CO2 emissions were causally related in both directions11. Air travel is a fuel-intensive logistics industry sector with among the quickest growth rates12.

Businesses were compelled by stricter environmental regulations to employ more biomass fuel and encourage a decrease in CO2 emissions13. This finding was also confirmed by the survey findings for road and sea freight transportation14. In another study15, the Canadian logistics sector revealed significant variations in how environmental regulations affected CO2 emissions. Nonetheless, the findings of studies conducted by16,17 demonstrated that with the influence of the surroundings, there were still very few rules. The primary cause is the ineffective implementation of their ecological strategy18.

There have substantial challenges when trying to gauge the extent of their environmental impact due to a lack of a universally accepted measuring method and an inadequate understanding of the proper amount of greenhouse gas emissions in the complex logistics sector. The results show that CO2 emission projections are more accurate when gradient-boosting models are used19. To assess the short- and long-term impacts and diverse causal linkages, the long-term findings indicate that circular economy and green logistics may reduce CO2 emissions. However, the creation of municipal garbage adversely affects the environment.

Furthermore, the enduring association between economic growth, circular economy, and green logistics substantiates the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) concept. The research also establishes a bidirectional correlation between these indicators and CO2 emissions in the long term20. Enhancing carbon emission efficiency within the logistics industry is crucial for attaining carbon neutrality. We analyze carbon emissions in China to mitigate emissions and enhance efficiency within the logistics industry. The findings indicate a markedly low average value for the logistics industry in China, accompanied by a spatially declining gradient distribution. The average pure technological efficiency is the primary catalyst for enhancing the logistics industry. Environmental restrictions and people’s consumption levels positively influence the logistics business. Nonetheless, economic status, industrial composition, governmental investment, and energy intensity have a detrimental effect21.

How environmental regulations affect the logistics sector’s energy efficiency. The environmental record of economically advanced countries has demonstrated that manufacturing firms could reduce their usage of fossil fuels and increase their energy efficiency if environmental regulations were strengthened3. This finding was also supported by the panel’s easy transition analysis strategy findings9. A few academics examined how environmental regulations affect the energy industry’s effectiveness8.

The findings indicated that, in one sense, environmental regulations increased the energy efficiency of producing companies22. Technology innovation could also enhance production efficiency and reduce energy utilization, therefore encouraging energy-saving measures23. However, environmental regulations may force transportation firms to increase their use of automobiles using fresh energy. This enhanced energy efficiency and decreased the need for fossil fuels24.

A study of the maritime transportation infrastructure (TI) indicates that environmental limitations have little effect on the sector’s energy efficiency25. Ocean cargo vessels’ year-round seafaring, which made supervision difficult, represented one of the primary causes26. Nonetheless, the study results on air travel showed that stringent environmental regulations could force air carriers to strategically arrange their means of transportation and boost fuel economy27.

Most of the research that has been done so far examines how environmental regulations affect CO2 emissions from a broad standpoint. Mandatory environmental legislation and incentive environmental regulations are the two subcategories of environmental regulations28, and the effect tools of those dual regulations on carbon dioxide emissions are very dissimilar. Most research on CO2 emissions in the logistics industry has been done so far using conventional econometric techniques like the completely adapted ordinary least squares approach and the randomized lag regression framework29. All of these techniques presuppose that the parameter sequencing follows an average distribution.

The limitations of earlier studies have informed the work’s development objectives. This article splits environmental regulations into two categories: required environmental regulations and incentive environmental legislation. It then looks at how each category affects energy EE and CO2, respectively. The study’s findings support the government’s use of more adaptable ecological governance instruments to regulate the logistics industry. Most research that has already been done uses average value models such as dispersed lag, vector auto regression, and error correction models to look at the logistics industry.

The effect of inducing variables on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency can only be projected by these algorithms on the median. Social and economic phenomena also exhibit cyclical oscillations as the economic cycle shifts. The constant’s frequency fluctuates high and low, making the parameter’s sequence frequently non-stationary and irregularly distributed. The outcome of the parameter series deviates from the normal distribution when quantile regression is compared with conventional mean designs; the former is trustworthy and robust. Furthermore, quantile regression can calculate the total impact of the explaining factor, considering the influence of the highest, lowest, and median numbers on the variable being explained30.

This study fills these gaps by systematically analyzing the distinct impacts of mandatory and incentive-based environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency. Employing quantile regression offers a more robust understanding of how these regulations influence outcomes across different emissions and energy efficiency levels. Additionally, the research considers regional disparities, providing actionable insights for policymakers to tailor environmental strategies to local economic and environmental conditions.

Method and model specification

The basic principle of the quantile regression approach

The quantile regression model was selected for this study due to its ability to capture nonlinear and heterogeneous and’ different distributional points of the dependent variable, particularly in environmental and energy efficiency (EE) dynamics. Unlike traditional mean regression models, quantile regression offers a more comprehensive analysis by identifying relationship variations at different quantiles of CO2 emissions and energy efficiency levels. This is particularly relevant for examining the effects of environmental regulations, as their impact may differ significantly across low, medium, and high emitters.

While nonlinear threshold models are also a robust choice for analyzing nonlinear relationships, they are primarily suited to identifying discrete shifts or threshold effects at specific points in the independent variables. In contrast, quantile regression provides a more granular understanding of the conditional distribution. It is beneficial for analyzing datasets characterized by skewness, heteroscedasticity, or outliers of standard environmental and energy data features. Additionally, quantile regression avoids the need to predetermine thresholds, which could introduce subjectivity or limit the scope of analysis and instead enables a more flexible exploration of effects across the entire data spectrum.

The study’s objectives to analyze the asymmetric impacts of mandatory and incentive-based environmental regulations across provinces with varying CO2 emissions, the quantile regression model was deemed the most appropriate. This methodological choice aligns with the study’s aim of providing nuanced insights that can inform region-specific and percentile-specific policy interventions.

The classic means models can estimate the ordinary influence of the factors that explain the explanatory variables. Economic events are erratic. This results in financial cycles that are frequently skewed, with both right- and left-skewed distributions. When skewed variable data is estimated utilizing mean models, it produces a rise in the variability. It can compensate for these intrinsic flaws of the current average techniques and provide the total effect of the causal variables’ explanatory variables31. Quantile regression has gained popularity recently in organizations32, economics, and the environment33. The quantile regression method’s equation is as follows:

|

1 |

|

2 |

In this case, y is the factor that has to be stated x is the vectors of variables that explain it, µ is the random error term, θ is the percentage, and β is the amount that has to be assessed. The bootstrap method is used to estimate the quantile regression model, improving the accuracy of parameter estimates. The research to see34 for further details on the exact estimating process used in the bootstrap approach.

Model of CO2, and first theory

Environmental regulations are now crucial for making up for economic shortcomings and resolving environmental issues35. Growing investments in technology R&D, modernizing manufacturing machinery, and implementing energy-saving technologies are all encouraged by stronger environmental rules. However, the cost of producing companies’ emissions of pollutants has soared due to more substantial environmental restrictions, and businesses have suffered significant economic consequences. The effect of environmental restrictions on the logistics sector has been the subject of a restricted amount of associated research36. On the other hand, there are two categories of environmental regulations: required environmental regulations and incentive environmental regulations.

How the logistics industry’s transport infrastructure (TI) affects CO2. The primary forms of transportation used in logistics involve air, sea, railroad, and highway. China’s trains are powered by electricity at this point; therefore, CO2 emissions are not generated directly by rail transportation. The percentage of the entire shipment count from air and water transportation is negligible. The logistics industry’s primary transportation form is automobiles37. The logistics industry’s overall shipment count was 28.0%. 44% of all customer movement over the same time frame was attributed to highway traffic. Consequently, the TI transportation infrastructure (%) is represented in this article by the highway shipping ratio to the overall transportation volume. This can look into the effects of the logistics industry’s modes of transport and CO2 emissions.

How international trade affects the logistics sector’s CO2 emissions. The most significant trade economy in the entire globe at present is China’s38. China’s entire value of imports and exports was 32.16 trillion yuan in 2020. Trade in goods and services propels China’s logistics sector’s explosive growth. First, commodity imports and raw materials such as metal ores, copper concentrate, dairy goods, and animal items must be delivered to manufacturing facilities or end users. Secondly, China’s export-oriented businesses need logistical transit for many completed goods and raw materials. These goods include cotton, apparel, footwear, caps, steel, machinery, and technology.

Finally, trading with other countries helps draw big international corporations to China for investment. International companies use cutting-edge technologies and managerial styles. Through technological spillovers, large international corporations can incentivize local logistics companies to upgrade their equipment and technology while lowering their carbon footprint. This research incorporates foreign trade within the conceptual structure (100 million yuan) due to the tight connection between the logistics industry and foreign trade.

How the framework of energy use affects CO2 emissions in the logistics sector. Most energy used in logistics is fossil fuel, such as coal. Large-scale CO2 emissions are an inevitable result of extensive fossil fuel use. CO2 emissions can be significantly decreased by consuming less fossil fuel and increasing the usage of greener fuels like biofuel gasoline and biomass fuel. Its power system significantly influences the logistics sector’s CO2 emissions.

Applied model of CO2

The standard model for analyzing emissions of pollutants is now the STIRPAT model.

|

3 |

Where I stand for a particular contaminant found in the environment, P stands for population factors, T for technological aspects, and A for financial variables. These three factors’ mutual impact coefficients are denoted by c, d, and b. The unpredictable disturbance term is indicated by e. These three fundamental parameters that affect pollutant emissions are listed in Eq. (4). Furthermore, as demonstrated by the theoretical process research previously, the logistics industry’s CO2 emissions are directly correlated with incentives and required environmental legislation, logistics infrastructure, international trade, and utilization of energy structure. Thus, this study incorporates the aforementioned components into Eq. (3). In the meantime, the current study takes the logarithm of all factors to eliminate the potential heteroscedasticity. The particular model that was built looks like this:

|

4 |

In above equation L, denotes logarithm for all variables, while independent variables, urbanization is denoted by UN, economic growth (GDP), technological advancement (TP), incentive environmental regulations (IER), mandatory environmental regulations (MERP), logistics transportation (LT), foreign trade (FT), energy structure (ES), fiscal decentralization (FD), foreign direct investment (FDI), transportation infrastructure (LTI), and carbon dioxide emissions in the logistics sector by CO2. A constant term is denoted by C, whereas the value that needs to be evaluated is represented by β1, β2, and β11. To study CO2 emissions, this research builds a special model based on the quantile model’s conceptual structure (Eq. 5).

|

5 |

Where C stands for constant term and Q for quantile regression. τ denotes the percentile point, with a range of values from 0 to 1. Five sample percentile points (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th) are frequently selected by research currently in publication for empirical study in that specific procedure. This method is also applied to the empirical investigation in the present paper.

Model of EE, and second theory

The next part identifies the primary influencing elements of energy efficiency in the logistics sector according to the findings of current studies. The following is an explanation of the theoretical connection between these variables and energy efficiency:

How environmental rules affect energy efficiency in the logistics sector. There are negative externalities associated with environmental pollution, and the environment is beneficial to the public. Numerous industrial businesses pollute the environment in order to lessen their financial burden. It is challenging to address environmental pollution via market processes. As a result, the authorities now use environmental legislation as a key tool to reduce environmental pollution. Environmental legislation with incentives can encourage businesses and government agencies to invest more in R&D and technical staff, boosting energy efficiency (EE). Industries have upgraded their machinery and increased their use of renewable energy sources due to the harsh penalties from required regulations on excessive chemical emissions39. Both environmental requirements significantly impact energy efficiency. To examine these two environmental regulations’ effects on EE, this research integrates them into a theoretical structure.

The way that fiscal decentralization (FD) affects the logistics sector’s energy consumption. Because local governments have an informational advantage, fiscal decentralization (FD) can increase spending efficiency40. The process of acquiring information has an impact on scale as well as the distribution of technical and environmental knowledge. The cost will be less if qualified government organizations gather and disseminate scientific and environmental data. Local governments can receive energy technology information more effectively with fiscal decentralization, increasing energy efficiency. The article presents the intricate relationship between fiscal decentralization (FD) and energy efficiency (EE) within a theoretical structure.

How the logistics sector’s transportation infrastructure (TI) affects energy efficiency. Logistics transport requires a transit infrastructure. The logistics business can proliferate if there is perfect infrastructure for transportation. The use of energy in the logistics sector is impacted by infrastructure for transportation in two primary ways41. Firstly, enhancing transportation networks helps to increase energy efficiency by lowering the energy used for interregional transit. Secondly, better transportation infrastructure (TI) has the potential to stimulate economic expansion. Economic development will increase the consumption of fossil fuels by expanding the need for transportation. The transport industry can lower its energy consumption through scale effects when there is a significant demand for transportation, which can increase energy efficiency. This article integrates transport infrastructure (TI) into the conceptual structure because of the intricate relationship between transportation infrastructure and energy efficiency. Infrastructure for transportation can be calculated as follows: land area (km/km2) / (railway + road mileage).

The process by which technological advancement affects the use of energy in the logistics sector. Long-term technological advancements play a significant role in raising EE. Technological advancements can help transportation firms enhance their machinery and manufacturing, increasing energy efficiency42. A fast-speed train, for instance, can boost energy efficiency and expedite the flow of logistics cargo. Furthermore, using gas and oil hybrid vehicles can drastically reduce the amount of fossil fuel oil used, increasing the energy effectiveness of road transportation. On the opposing side, fresh highways and high-speed rail lines can be constructed, and infrastructure for transportation can be improved thanks to technological advancements. This encourages cheaper and more effective cross-regional passenger and cargo transit. This increases energy efficiency and reduces the amount of energy used. It is evident that there are numerous ways in which technological advancements may affect energy efficiency, and these effects are extensive. As a result, the methodology used in this study incorporates technological advancement. The number of units per 10,000 persons (Unit/10,000) indicates technological advancement.

Direct investment businesses typically have cutting-edge machinery and technology. According to43, modern machinery and technology have implications that may result in the logistics industry updating its machinery and technology. Consequently, increasing output and reducing energy usage are facilitated by foreign direct investment (FDI). As a result, the logistics sector’s energy efficiency increases. This study presents foreign direct investment within the conceptual structure, considering its significance for energy efficiency. Real foreign direct investment, or 100 million yuan, calculates foreign direct investment (FDI). The way that urbanization affects the logistics sector’s energy efficiency. Many individuals from rural areas have moved into towns due to urbanization, and the number of urban residents has increased quickly. The need for transportation has proliferated due to cities’ size, population density, and operations44. However, labor and technical skills are now more frequently transferred among metropolitan agglomerations due to urbanization. The need for transportation will rise as a result. Transportation scale-ups can lead to economies of scale and increased energy efficiency. This article incorporates urbanization into the conceptual structure because of the tight link between urbanization and power effectiveness in the logistics sector.

Applied model of EE

Equation (6) of this paper’s experimental model of energy utilization in the logistics sector depends on the theoretical research mentioned above.

|

6 |

In order to create a certain type of energy efficiency (Eq. 7), the variables in Eq. (6) are introduced into Eq. (2) in this study.

|

7 |

Where τ is the quantile, while Q shows quantile regression.

Data description

The paper’s analysis includes the data covering China’s thirty counties between 2005 and 2019. The following describes how the parameter’s number is calculated. The logistics industry’s CO2 emissions are calculated as follows: 1.90 kg/kg of coal consumed; 2.93 kg/kg of gasoline; 3.10 kg/kg of diesel; 3.17 kg/kg of fuel oil; 3.01 kg/kg of kerosene; 3.02 kg/kg of crude oil; and 2.16 kg/m3 of natural gas. The China Energy Statistical Yearbook is the primary source of information about CO2 emissions in the logistics industry. Table 1 displays descriptive statistical findings for the various economic factors accordingly. On the other hand, energy efficiency (EE) is determined by the economic profit divided by the amount of energy consumed (Yuan/tce).

Table 1.

Statistical analysis.

| Factors | Unit | Mean | Std.dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO 2 | 10,000 tons | 2777.5 | 1795.1 | 151.5 | 10,299.0 |

| EE | Yuan/ton | 9223.0 | 17,019.0 | 2309.6 | 279,198.0 |

| FD | % | 106.4 | 73.6 | 41.1 | 465.3 |

| ES | % | 4.23 | 25.35 | 0.0001 | 42.50 |

| UN | % | 53.0 | 12.7 | 25.8 | 88.5 |

| IER | Yuan/person | 14.7 | 11.0 | 1.11 | 83.6 |

| MERP | Piece | 110.3 | 135.6 | 4 | 1374 |

| TP | Yuan/person | 14.8 | 24.0 | 0.32 | 161.3 |

| FT | 100 million yuan | 7419.8 | 12,816.4 | 32.3 | 74,428.0 |

| LT | % | 75.4 | 12.0 | 35.6 | 96.8 |

| FDI | 100 million dollars | 8801.6 | 15,501.1 | 55.4 | 136,261.7 |

| TI | km/km2 | 0.76 | 0.40 | 0.03 | 1.06 |

The ratio of the urban population (UN) to the overall population (%) represents urbanization. The ratio of regional per capita fiscal spending to national per capita fiscal expenditure (%) is a proxy for fiscal decentralization (FD). The amount of imports and exports commerce (100 million yuan) is used to gauge foreign trade (FT). Land area (km/km2) / (railway miles + road mileage) equals transportation infrastructure. The transport infrastructure (TI) into the conceptual structure because of the intricate relationship between transportation infrastructure and energy efficiency. Infrastructure for transportation can be calculated as follows: land area (km/km2) / (railway + road mileage).

The foreign direct investment (FDI), is a sum invested in China by foreign enterprises (100 million yuan). Economic growth (GDP), and Technological advancement (TP), which is measured by the number of patents per 10,000 people (Unit/10,000 people). Logistics transportation by (LT) is measured by road freight volume in the total freight volume (%). Energy structure by (ES) is represented by the proportion of coal use in the logistics industry to its total energy consumption (%), and all these dependent variables data are derived from the China Statistical Yearbook.

The data for mandatory environmental regulations (MERP) and incentive environmental regulations (IER) were sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook, which tracks regulatory frameworks in China. Mandatory regulations include legally binding measures, such as emission caps and penalties for non-compliance (Legal requirements and penalties for emissions). In contrast, incentive-based regulations encompass subsidies, tax credits, and grants for adopting energy-efficient technologies. The dataset spans 2005 to 2019 and was chosen to align with significant regulatory changes in China. Despite limitations in time coverage, this period provides critical insights into the effectiveness of these policies. Regional variations in regulatory enforcement and economic activities are also considered, with data collected from 30 provinces representing diverse economic and environmental contexts.

Addressing the issue of data transparency and the potential limitations of the dataset is crucial for enhancing the credibility and scope of this study. The paper relies on panel data from 30 Chinese provinces spanning 2005 to 2019, a comprehensive dataset that allows for a robust analysis of the impact of environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency in the logistics sector. However, reflecting on certain limitations and opportunities for enrichment is equally important.

One limitation of the data source is its reliance on provincial-level aggregates, which may obscure intra-provincial variations and local dynamics within specific logistics hubs or industrial zones. These finer details could reveal more granular trends, such as how urban centres versus rural areas respond differently to environmental regulations. Future research could incorporate city-level or even firm-level data, allowing for a more detailed exploration of the effects of environmental policies on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency.

Another area for improvement is the potential for data gaps or inconsistencies over the study period. For instance, variations in reporting standards, data collection methodologies, or regulatory compliance across provinces could affect the uniformity and comparability of the dataset. Acknowledging these potential discrepancies and their implications for the study’s findings is essential. Employing supplementary data sources or triangulating findings with alternative datasets could provide additional validation and depth to the analysis. Finally, the dataset focuses primarily on the logistics sector and its sub-sectors such as air, rail, and sea transport. Each sub-sector has distinct operational characteristics and environmental impacts, which could influence the efficacy of mandatory and incentive-based regulations.

Results and discussion

The logistics industry plays a pivotal role in economic development and significantly contributes to global CO2 emissions. This duality highlights the pressing need for sustainable solutions within the sector. Despite technological advancements and increasingly stringent environmental regulations, regional disparities and inefficiencies in mitigating emissions persist. These challenges are particularly pronounced in China, where the logistics industry operates across diverse regional contexts, each with unique socioeconomic and environmental characteristics. Understanding these complexities is critical to addressing the broader global challenge of reducing CO2 emissions.

The purpose of this study investigates the drivers of CO2 emissions and the factors influencing energy efficiency (EE) in the logistics industry across 30 Chinese provinces. It employs quantile regression to explore the nonlinear relationships and heterogeneity inherent in these dynamics. Unlike traditional models, this approach provides a nuanced understanding of how factors such as economic growth, urbanization, and technological advancement influence CO2 emissions and energy efficiency across varying regional contexts.

This research contributes significantly to the growing literature on sustainable logistics and environmental management. Combining an analysis of CO2 emissions and energy efficiency within the logistics industry using quantile regression, the study captures non-linear effects and regional heterogeneity often overlooked in conventional approaches. The results comprehensively understand the interplay between economic, technological, and environmental factors in shaping emissions and energy efficiency outcomes.

Unit root test

Data from panels has greater detail than longitudinal and cross-sectional data. Many academics have used survey information in the past few decades to investigate social and economic concerns such as climate change, job mobility, and financial sector instability. Because socioeconomic events are characterized by fluctuation, the order of economic factors is frequently non-stationary40. According to econometric theory, a linear regression is only a “pseudo-regression” if the collection of economic variables utilized for the model estimate is not stationary. A regression estimate must be preceded by a stationarity examination of the socioeconomic data set being utilized to prevent spurious regression. To determine the unit root test. The IPS45 (Im-Pesaran- Shin) tests are the primary panel unit root test techniques. First of all, the test equation is as follows:

|

8 |

Wherein p is the lag order & en is the autoregressive coefficient. Breitung test. e1,nt and e2,nt, accordingly, are the residuals that result from regressing Δynt and yn, t-1 on their lag term (Δyn, t-1, Δyn, t-2, …, Δyn, t-p). After applying orthogonal dispersion conversion to the residuals, a new equation emerges:

|

9 |

Lastly, carry out the subsequent regression:

|

10 |

(3) The following is the IPS testing calculation:

|

11 |

The following constitute the presumptions of the Fisher-ADF test.

|

12 |

The evaluation statistic’s calculation is as the following:

|

13 |

Every testing technique has distinct qualities and a variety of uses. When evaluating financial data using greater-order auto regression, the ADF test is appropriate. The efficacy of the ADF test will be significantly diminished if the number of respondents collecting information is small. The LLC test and the test have comparable application areas. This paper tests these economic sequences using the aforesaid methodologies to increase the dependability of the evaluation findings. Table 2’s results show that no single factor sequence passed every test. This indicates that there is non-stationarity among these parameter series.

Table 2.

Unit Root outcomes.

| Series | LLC | Breit | IPS | Fisher ADF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LCO2 | − 5.012*** | 1.555 | − 0.421 | 81.516** |

| LEE | − 2.127*** | 1.601 | − 0.033 | 60.800 |

| LFD | − 5.120*** | 2.035 | 0.464 | 52.615 |

| LES | 2.600 | 4.301** | 7.566 | 1.877*** |

| LUN | − 1.026*** | −2.346*** | 1.082 | 48.801 |

| LIER | − 4.118*** | − 0.181 | − 1.812** | 77.536* |

| LMERP | − 4.727*** | 1.705 | − 1.055** | 100.002*** |

| LTP | 0.236*** | 1.704 | 2.186 | 35.072*** |

| LFT | − 5.302*** | − 0.211 | − 1.703** | 77.622** |

| LLT | − 1.158*** | 3.058 | 1.563 | 54.114** |

| LFDI | 0.380*** | 8.056 | 3.335 | 36.874*** |

| LTI | − 73.064*** | − 1.074 | − 59.712*** | 330.730*** |

Cointegration tests

In the early stages, researchers primarily solved non-stationary economic time sequence regress using the first-order differential approach. The sequence of economic factors will lose their economic significance if the first-order differential approach is used46. The first-order difference approach creates a new variable sequence by figuring out the difference in the values of the variable data. Economically speaking, the distinct parameter series is meaningless. The inadequate nature of numerous researchers in statistics and econometrics inspired to do related studies by the first-order differential technique, including Engle, and the cointegration concept was first put forth by47. The main idea behind the cointegration concept is to estimate so long as they have a co-integration connection among all explanatory factors and the clarified factors. The48,49 Pedroni and Kao tests are the primary panel cointegration techniques currently in use. The following is the equation for the ADF statistic.

|

14 |

The following formula can be used to get the Pedroni testing data.

|

15 |

The cointegration test is conducted using one of these approaches, and Table 3 displays the outcomes. The significance test is passed by all statistic results from both tests. It suggests that there exists a causal connection among the variables that influence CO2 emissions and those that influence energy efficiency.

Table 3.

Co-integration outcomes.

| Test | CO2 emissions | CO2 emissions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dickey-Fuller | 1.462** | 1.100*** | |

| Kao test | Unadjusted Dickey-Fuller | 1.400*** | 1.047*** |

| Modified Phillips- Perron | 8.372*** | 8.685*** | |

| Pedroni test | Phillips-Perron | − 13.208*** | − 6.533*** |

|

Augmented Dickey- Fuller |

− 8.253*** | − 5.827*** |

Quantile regression results of CO2 and EE

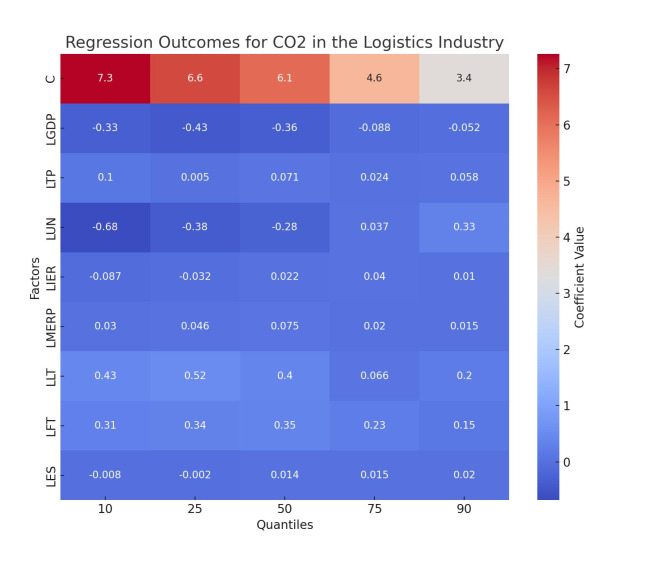

We can divide 100 percentiles (i.e., 1%, 2%, and 100%) between 0 and 1. The effect size of the explanatory factor on the variable in question at each measure can be estimated using quantile regression. This study chooses five representative quantile points based on pertinent research findings: the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th. Tables 4 and 5 display the estimation outcomes for all quantile points. This section also employs a mean approach to regression estimation to illustrate the benefits of quantile regression. The median influence of influencing variables on energy efficiency and CO2 emissions may only be estimated via mean regression; the influence of variables on energy efficiency and CO2 emissions across various percentile points cannot be estimated. Tables 4 and 5 present the outcomes of the significance test, indicating that all explaining factors’ statistic values survived. Figure 1 shows the regression outcomes for CO2 in the logistics industry.

Table 4.

Endogeneity outcomes (CO2) in the logistics industry.

| Factors | Q-regression | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | ||

| Cons | 9.046*** | 5.633*** | 3.701*** | 4.070** | 1.115*** | 3.701*** |

| LGDP | − 0.304** | − 0.274*** | − 0.153*** | − 0.210 | − 0.020* | − 0.153** |

| LTP | 0.077*** | 0.068** | − 0.010** | − 0.037** | − 0.075** | − 0.010*** |

|

LUN FDI |

− 1.083** -0.541** |

− 0.440** -0.227*** |

− 0.011* -0.417** |

0.712** -0.412** |

0.811** -0.114*** |

− 0.011*** -0.112*** |

| LIER(− 1) | − 0.048* | − 0.034** | 0.010*** | 0.038** | 0.143** | 0.010*** |

| LIER(− 2) | − 0.120** | − 0.011*** | 0.002** | 0.071* | 0.156** | − 0.002*** |

| LMERP(− 1) | 0.057** | 0.077** | 0.107** | 0.020*** | 0.003*** | 0.107** |

| LMERP(− 2) | 0.070* | 0.082** | 0.077*** | 0.035** | 0.066*** | 0.177*** |

| LLT | 0.227** | 0.480*** | 0.280** | − 0.027** | 0.180** | 0.270** |

| LFT | 0.313*** | 0.320*** | 0.288*** | 0.236*** | 0.178*** | 0.288*** |

|

LES FD LTI |

− 0.001*** -0.411** 0.014*** |

0.002** -0.241** 0.411*** |

0.008*** -0.785** 0.417*** |

0.004*** -0.014*** 0.952** |

0.003*** -0.014*** 0.742*** |

0.008*** -0.581** 0.352*** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.477 | 0.418 | 0.322 | 0.286 | 0.301 | 0.322 |

Table 5.

Endogeneity outcomes (EE), in the logistics industry.

| Factors | Q-regression | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | ||

| Cons | 10.010*** | 8.767*** | 8.255*** | 8.262*** | 6.221*** | 8.255*** |

| LGDP | 0.080** | 0.005** | 0.068** | 0.040** | 0.077*** | 0.068** |

|

LUN LTI |

− 0.065** 0.751** |

0.700*** 0.741*** |

0.857** 0.451** |

0.847** 0.412*** |

1.500*** 0.478*** |

0.867*** 0.742*** |

| LIER(− 1) | 0.047*** | 0.086* | 0.085** | 0.177*** | 0.240** | 0.185** |

| LIER(− 2) | 0.060* | 0.087* | 0.026** | 0.080** | 0.113*** | 0.026** |

| LMERP(− 1) | − 0.003*** | − 0.016** | − 0.042*** | − 0.038* | − 0.050** | − 0.042** |

| LMERP(− 2) | − 0.013*** | − 0.063** | − 0.062** | − 0.021** | − 0.010*** | − 0.062*** |

|

LTP LFT |

0.136*** 0.554** |

0.140*** 0.445** |

0.062*** 0.004*** |

0.078** 0.147** |

− 0.042*** 0.0.119*** |

0.062*** 0.015*** |

|

LFDI LES |

− 0.020** -0.044*** |

− 0.020** 0.095** |

− 0.066** 0.0471** |

− 0.087** 0.458*** |

− 0.011*** 0.478*** |

− 0.066** 0.019*** |

|

LFD LLT |

− 0.445*** 0.147** |

− 0.678*** 0.478*** |

− 0.735*** 0.958*** |

− 0.655*** 0.998*** |

− 0.664*** 0.242*** |

− 0.735*** 0.215*** |

| Pseudo R2 |

0.1 58 |

0.180 | 0.162 | 0.131 | 0.120 | 0.162 |

Fig. 1.

CO2 in the logistics industry.

The Table 6 presents the quantile regression results for the determinants of CO2 emissions in the logistics industry, along with the F-statistic and median results. Each independent variable is analyzed across different quantiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles) to account for heterogeneous impacts at various emission levels. The median regression results and statistical significance of the F-statistics are also provided. The constant term (C) is positive and statistically significant across all quantiles, indicating a baseline level of CO2 emissions in the logistics industry regardless of other factors. The magnitude of the constant term decreases as we move from lower to higher quantiles, suggesting diminishing baseline emissions at higher emission levels.

Table 6.

Regression outcomes of CO2 in the logistics industry.

| Factors | Q-regression | F-Stat | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |||

| C | 7.261*** | 6.585*** | 6.086*** | 4.627* | 3.384*** | − | 6.086*** |

| LGDP | − 0.330** | − 0.427*** | − 0.357*** | − 0.088** | − 0.052** | 1.60** | − 0.357*** |

| LTP | 0.100*** | 0.005*** | 0.071** | 0.024** | 0.058*** | 2.00*** | 0.071*** |

| LUN | − 0.680** | − 0.380** | − 0.276** | 0.037*** | 0.334 | 2.12** | − 0.276** |

| LIER | − 0.087** | − 0.032* | 0.022** | 0.040** | 0.010*** | 1.68** | 0.022*** |

| LMERP | 0.030*** | 0.046*** | 0.075*** | 0.020** | 0.015** | 2.42*** | 0.174*** |

| LLT | 0.431** | 0.520*** | 0.400** | 0.066 | 0.203 | 1.75** | 0.400** |

|

LFT FDI |

0.308*** 0.114** |

0.335*** 0.213** |

0.346*** 0.224*** |

0.228*** 0.547* |

0.152*** 0.951* |

2.31*** 0.874* |

0.346*** 0.449*** |

|

LES LFD LTI |

− 0.008* -0.0411** 0.159** |

− 0.002** -0.417* 0.248** |

0.014*** -0.121** 0.752*** |

0.015* -0.711** 0.742*** |

0.020* -0.587** 0.742*** |

2.60*** -0.149** 0.541*** |

0.014** -0.589** 0.411*** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.580 | 0.420 | 0.412 | 0.274 | 0.308 | − | 0.312 |

Economic growth (GDP) shows a negative and statistically significant effect on CO2 emissions across all quantiles, indicating that increased economic growth leads to reduced emissions. Economic growth in the logistics sector may support cleaner practices or technologies, contributing to lower emissions. The effect is more pronounced at lower quantiles, reflecting more substantial reductions in emissions for regions or scenarios with initially lower CO2 levels. Moreover, technological advancement (TP) also have positively and statistically significantly impacts CO2 emissions across all quantiles. The findings suggest that technological development in the logistics industry is associated with increased emissions, possibly due to the adoption of energy-intensive technologies. The effect is relatively consistent across quantiles, indicating that the relationship does not vary substantially across emission levels.

Urbanization (UN) demonstrates mixed effects. It negatively and statistically significantly impacts CO2 emissions at lower quantiles (10th and 25th). Urbanization in less emission-intensive scenarios may lead to better environmental outcomes through improved efficiency. However, it becomes positive at higher quantiles, indicating that in regions or cases with higher emissions, urbanization may exacerbate CO2 levels.

Incentive environmental regulations (IER) exhibit varying effects. The impact is negative and statistically significant at lower quantiles, indicating that these regulations effectively reduce emissions in low-emission scenarios. However, the impact becomes positive at higher quantiles, suggesting limited effectiveness or even adverse effects in more emission-intensive regions. On the other hand mandatory environmental regulations (MERP) consistently show a positive and statistically significant impact on CO2 emissions across all quantiles. This unexpected result might indicate that these regulations must be more stringent or are associated with compliance costs, leading to higher emissions in some instances.

Logistics transportation (LT) positively affects CO2 emissions at the lower quantiles (10th and 25th) and the median, but the relationship weakens at higher quantiles. This indicates that transportation activities are a significant source of emissions, particularly in lower to moderate emission scenarios, but their relative impact diminishes in higher-emission contexts. While, foreign trade (FT) consistently exhibits a positive and statistically significant effect on CO2 emissions across all quantiles. This highlights the contribution of trade-related activities to emissions in the logistics sector and emphasizes the need for sustainable trade practices to mitigate environmental impacts.

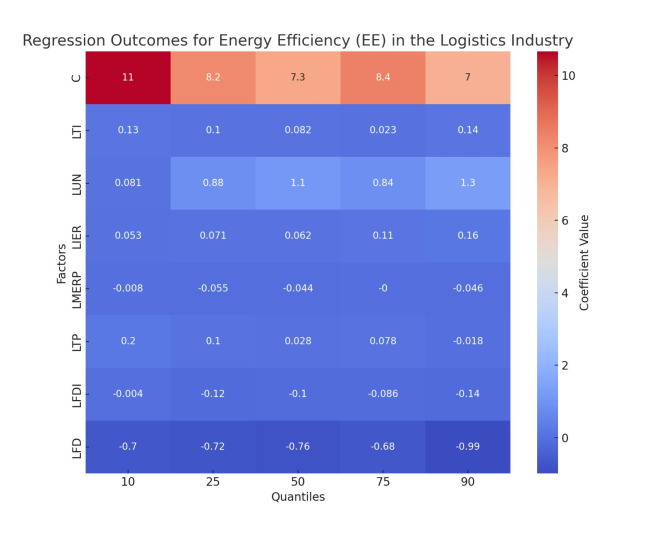

The energy structure (ES) has an insignificant relationship with CO2 emissions across all quantiles. This result suggests that the composition of energy use in the logistics industry does not significantly impact emissions within the analyzed context. In summary, the results underline the complex and varying relationships between economic, regulatory, and sectoral factors and CO2 emissions in the logistics industry, highlighting the importance of tailored policies for different emission scenarios. Figure 2, shows the regression outcomes of energy efficiency in the logistics industry.

Fig. 2.

Energy efficiency in the logistics industry.

The Table 7 provides the quantile regression outcomes for the logistics industry’s determinants of energy efficiency (EE), assessed across various quantiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles). The analysis highlights the heterogeneity in the factors influencing EE at different levels, supplemented by median regression results and F-statistics for model validation.

Table 7.

Regression outcomes of EE in the logistics industry.

| Factors | Q-regression | F-Stat | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | |||

| C | 10.662*** | 8.203*** | 7.300*** | 8.402*** | 7.048*** | − | 7.300*** |

| LGDP | 0.133*** | 0.105*** | 0.082* | 0.023*** | 0.142*** | 1.06* | 0.082** |

|

LUN LES |

0.081** -0.258** |

0.878*** -0.696** |

1.134*** 0.558* |

0.841*** 0.771** |

1.300*** -0.589*** |

2.08** 0.699** |

1.136*** 0.547** |

|

LIER LFT |

0.053*** 0.992** |

0.071*** 0.225** |

0.062*** 0.524*** |

0.106*** 0.417** |

0.162*** 0.369*** |

4.36*** 0.951*** |

0.062*** 0.875*** |

| LMERP | − 0.008*** | − 0.055** | − 0.044** | − 0.0*** | − 0.046** | 2.78*** | − 0.044* |

|

LTP LLT |

0.203*** 0.145*** |

0.103*** 0.58** |

0.028*** 0.851*** |

0.078** 0.047** |

− 0.018** 0.841*** |

5.60*** 0.854*** |

0.028*** 0.922*** |

| LFDI | − 0.004** | − 0.123*** | − 0.105*** | − 0.086*** | − 0.138*** | 2.08*** | − 0.105*** |

|

LFD LTI |

− 0.705*** 0.221** |

− 0.720*** 0.417*** |

− 0.760*** 0.233** |

− 0.684*** 0.774** |

− 0.987*** 0.352** |

1.70*** 0.074*** |

− 0.760*** 0.041*** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.147 | 0.173 | 0.158 | 0.143 | 0.140 | − | 0.158 |

Transportation infrastructure (TI) demonstrates a positive and statistically significant impact on EE across all quantiles. The relationship indicates that advancements in technology contribute significantly to enhancing energy efficiency, with the effect being more pronounced at lower and higher quantiles, suggesting a critical role for technology in both low- and high-efficiency scenarios. Urbanization (UN) has a statistically significant and positive impact on EE from the 25th quantile onward. This relationship suggests that urbanization contributes to improvements in energy efficiency, particularly in regions or scenarios with moderate to high levels of efficiency. The effect becomes more potent at higher quantiles, indicating that urbanized areas are more likely to benefit from enhanced energy-saving practices or infrastructure.

Incentive-based environmental regulations (IER) have a positive and statistically significant impact on EE across all quantiles, with the magnitude increasing at higher quantiles. This result underscores the effectiveness of incentives, such as subsidies or tax breaks, in encouraging investments in energy-saving technologies and practices, particularly in contexts with higher efficiency levels. Mandatory environmental regulations (MERP), on the other hand, exhibit a negative and statistically significant relationship with EE across all quantiles. This counterintuitive result may suggest that mandatory regulations impose compliance costs or operational restrictions that inadvertently reduce energy efficiency, particularly at moderate to high levels of efficiency.

Technological advancement (TP) generally has a positive and statistically significant effect on EE at lower quantiles and the median. However, the effect diminishes and becomes negative at the highest quantile. This trend indicates that while transportation advancements contribute to energy efficiency in low- to moderate-efficiency scenarios, their benefits may translate less effectively in highly efficient settings, potentially due to diminishing returns or increased energy demand in advanced systems. Foreign direct investment (FDI) shows a consistently negative and statistically significant relationship with EE across all quantiles. This finding implies that FDI in the logistics industry might not prioritize energy-efficient technologies or practices, leading to lower energy efficiency overall.

Fiscal decentralization (FD) also exhibits a negative and statistically significant impact on EE at all quantiles, with the magnitude increasing at higher quantiles. This indicates that fiscal decentralization, as measured in this study, might not align with energy efficiency goals, potentially due to a focus on economic expansion that prioritizes other factors over energy conservation. In summary, the results highlights the diverse influences of technological, urban, regulatory, and financial factors on energy efficiency in the logistics sector. The findings suggest that while technological innovation and incentive regulations promote EE, mandatory regulations and fiscal variables present challenges, calling for targeted strategies to balance these factors effectively.

This suggests that incentive-based environmental regulations can potentially increase the logistics sector’s EE. Furthermore, incentive environmental legislation significantly affects CO2 emissions in quantile groups that fall into the 50th–75th, 75th–90th, and higher 90th. Several economically advanced provinces, including Guangdong, are among these groupings states of Zhejiang, Shandong, Fujian, and Tianjin. These states have grown economically, and their logistics sector has expanded quickly. The logistics sector’s explosive expansion has resulted in significant CO2 emissions and fossil fuel usage. Various provinces have given the ecological environment more consideration and recently released several regional guidelines to promote sustainable energy usage. As an illustration, the government funds the usage of biodiesel and ethanol in fuel, as well as financial support for transforming fuel-powered cars into hybrid cars powered by gas and oil. This dramatically boosts production while consuming less energy, increasing energy efficiency.

There has been no apparent improvement in energy efficiency, as indicated by the negative regression coefficients of mandatory environmental rules. Mandatory environmental regulations significantly impact businesses’ production operations, acting as a “hard constraint.” For instance, production companies who do not meet the requirements run the danger of having their operations halted. This hampers both social stability and steady economic growth (GDP). As a result, mandatory environmental policies have been carefully crafted by Chinese governments at all levels. Mandatory environmental standards often need to be correctly implemented by producing enterprises. Consequently, increasing energy efficiency in the logistics sector is unaffected by mandated environmental requirements.

The findings of this study offer several practical solutions and suggestions to address the identified challenges. First, sector-specific policies should be prioritized to address regional and modal disparities within the logistics industry. For instance, promoting rail and sea freight over more carbon-intensive road and air transport can significantly reduce emissions. Second, financial and regulatory frameworks should incentivize the adoption of low-carbon technologies across all logistics sectors. Third, improving urban logistics planning can help minimize inefficiencies and emissions in densely populated areas. These solutions emphasize the need for targeted interventions considering the unique characteristics of different logistics sectors and regions. These solutions have been addressed further in the last section of this manuscript in policy implications.

Endogenous test

This study recognizes the potential issue of endogeneity, which could arise due to reverse causality, omitted variable bias, or simultaneous causality between environmental regulations, CO2 emissions, and energy efficiency. To mitigate this concern, we incorporate several control variables that help isolate the specific effects of environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency in the logistics industry. These control variables include urbanization, foreign trade, economic growth, and energy efficiency, all critical factors influencing the implementation of regulations and environmental outcomes.

By including these variables, we aim to reduce the risk of omitted variable bias, ensuring that other structural or economic factors do not confound the estimated effects of mandatory and incentive-based regulations. Additionally, including control variables helps account for possible indirect effects or feedback loops that may exist between economic activity and environmental performance. For instance, economic growth and foreign trade can impact both the regulatory environment and the carbon intensity of production processes. Thus, it is essential to include them as controls to obtain a clearer picture of the causal relationship.

In Tables 4 and 5, to further address endogeneity, the study employs several econometric techniques, including the use of instrumental variables where appropriate, to establish the direction of causality and ensure the robustness of the results. These controls and techniques collectively aim to isolate the effect of environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency, ensuring that the findings reflect the true impact of regulatory measures rather than being driven by underlying economic or structural factors.

Social and economic phenomena are frequently linked together, bolstering government agencies, and industrial companies will benefit from environmental restrictions by investing more in technical R&D and gear replacement. This also helps to lower CO2 emissions and increase energy efficiency. Consequently, increasing energy efficiency and decreasing CO2 emissions will require authorities to move more quickly to pass environmental regulations and levies, like resource taxation and licenses for carbon emissions. There is a causal connection between environmental legislation and both CO2 emissions and energy efficiency. If the hypothesis encounters endogeneity issues, the explanation variable and the variable that depends share a causal relationship. Econometric models frequently contain endogeneity. Endogeneity arises when there is a strong association between the reliant and explanatory variables, which can lead to detrimental effects like elevated estimate prejudice. To determine that the potential endogeneity poses a significant detrimental effect on estimated outcomes, this study employs the instrument using the conceptual variables approach to run the endogeneity test.

The findings presented in Table 5 demonstrate that both the LIER(-1) and LIER(-2) regression coefficients are favorable. It’s identical as LIER regression coefficient’s sign. The regression coefficients for LMERP(-1) and LMERP(-2) are both negative. It is in line with regression coefficient of LMERP’s sign. After integrating the aforementioned findings, it is possible to draw the conclusion that endogeneity has little to no negative impact on the estimation outcomes.

Robustness test

This work efforts to perform robustness tests in the next dual features to guarantee the dependability of the predicted results. First of all modify the duration of the sample. In 2011, “The Implementation Plan for Energy” was released by the Chinese National Development and Reform Commission. The energy consumption and CO2 emissions of logistics businesses will be strictly regulated by this order. The robustness of the empirical model in this study was evaluated using quantile regression applied to both CO2 emissions and energy efficiency (EE) in the logistics industry. Quantile regression was chosen as the primary method for robustness checks because it captures the effects of explanatory variables across the entire distribution of the dependent variables rather than focusing solely on mean effects. This approach is particularly relevant for policies like environmental regulations, which are likely to have varying impacts across different CO2 emissions and EE levels. Using quantile regression ensures that the study accounts for heterogeneity in the data, providing a more nuanced understanding of the examined relationships.

For CO2 emissions, the results in Table 8 demonstrate consistency across different quantiles (10th, 25th, median, 75th, and 90th), which validates the reliability of the findings. For example, the log of GDP (LGDP) exhibits a significant negative relationship with CO2 emissions at all quantiles, suggesting that economic growth, under current conditions, contributes to emission reductions in the logistics sector. Similarly, variables like the log of technological advancement (TP) and the log of foreign trade (LFT) consistently show positive relationships with CO2 emissions across quantiles, emphasizing their role as contributors to environmental pressures. The log of incentive-based environmental regulations (LIER) demonstrates mixed effects, with their impact varying across different emissions levels, further highlighting the importance of understanding distributional effects.

Table 8.

Robustness check (CO2) in the logistics industry.

| Factors | Q-regression | Median | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | ||

| Cons | 7.746*** | 7.543*** | 6.011** | 1.630** | − 5.784** | 6.011** |

| LGDP | − 0.811** | − 0.646*** | − 03460** | − 0.162** | − 0.750** | − 0.360** |

| LTP | 0.147** | 0.074** | 0.147** | 0.004** | 0.004*** | 0.002*** |

| LUN | − 0.014** | − 0.146** | − 0.287** | 0.605*** | 0.078*** | − 0.287** |

| LIER | − 0.080* | − 0.075*** | 0.002*** | 0.014** | 0.100** | − 0.002*** |

| LMERP | 0.063*** | 0.030** | 0.076*** | 0.182*** | 0.187*** | 0.076*** |

|

LLT LFDI |

0.700** -0.017*** |

0.620** -0.892*** |

0.440** -0.358*** |

0.447*** -0.369** |

0.842** -0.523*** |

0.440*** -0.447*** |

| LFT | 0.342*** | 0.323*** | 0.341*** | 0.212*** | 0.127*** | 0.341*** |

|

LES LFD LTI |

− 0.040** -0.323** 0.451** |

− 0.013** -0.118*** 0.741*** |

0.013** -0.996** 0.128** |

0.001*** -0.332*** 0.751*** |

0.010** -0.149*** 0.321*** |

− 0.013*** -0.362*** 0.781*** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.507 | 0.412 | 0.340 | 0.305 | 0.4779.340 | 0.151 |

Regarding energy efficiency, the results in Table 9 also provide robust evidence. The quantile regression results indicate that incentive-based environmental regulations (IER) and technological advancement (TP) positively influence EE across most quantiles. This demonstrates that these factors consistently promote energy efficiency across various performance levels within the logistics sector. Conversely, fiscal decentralization (FD) negatively affects EE across quantiles, indicating potential misalignment between financial structures and energy efficiency goals. These findings underline the importance of targeted policy interventions to ensure financial systems contribute positively to sustainability objectives.

Table 9.

Robustness check (EE).

| Variables | Med | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | ||

| Constant | 9.108*** | 7.475*** | 8.474*** | 10.645*** | 8.522*** | 8.474*** |

| LGDP | 0.080** | 0.105** | 0.086*** | 0.104*** | 0.267*** | 0.086*** |

|

LUN LLT |

0.646** 0.521** |

1.034*** 0.365*** |

0.674** 0.852*** |

− 0.002*** 0.421*** |

0.773** 0.149*** |

0.674*** 0.427*** |

| LIER | 0.060*** | 0.012** | 0.050*** | 0.153** | 0.163*** | 0.050*** |

| LMERP | − 0.028** | − 0.060** | − 0.030** | − 0.013*** | − 0.003*** | − 0.030*** |

|

LTP LFT |

0.200*** | 0.053** | 0.041** | 0.065*** | − 0.044*** | 0.041*** |

|

LFDI LES |

− 0.041*** -0.215*** |

− 0.105** -0.751*** |

− 0.081*** -0.351*** |

− 0.001*** -0.012*** |

− 0.075*** -0.241*** |

− 0.080*** -0.251*** |

|

LFD LTI |

− 0.732*** 0.442*** |

− 0.647*** 0.499*** |

− 0.605*** 0.152** |

− 0.374** 0.753*** |

− 0.486*** 0.669*** |

− 0.605*** 0.663*** |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.187 | 0.128 | 0.120 | 0.134 | 0.167 | 0.120 |

The choice of quantile regression as a robustness check is well-justified, as it provides a comprehensive view of how the studied variables influence CO2 emissions and EE across their distributions. This approach is particularly valuable in identifying heterogeneous effects that conventional methods like mean-based regression models might overlook. The pseudo-R-squared values reported at each quantile further support the robustness of the results, confirming that the model explains the observed relationships effectively and reliably.

While other robustness checks, such as nonlinear threshold models, could provide additional insights, the choice of quantile regression aligns well with the study’s objectives. It ensures a detailed and accurate analysis of the differential impacts of environmental regulations, which is crucial for deriving actionable policy recommendations. By employing this approach, the study provides a robust and nuanced framework for understanding the interplay between environmental regulations, CO2 emissions, and energy efficiency in the logistics sector. There has been no change in the explaining factors’ effect compared to the findings in Tables 7 and 4. This suggests that the quantile model has some robustness and that modifications to the data collection duration did not significantly affect the estimated outcomes.

A thorough examination and explanation of the factors that led to the empirical findings should be conducted. This subsection provides a thorough examination of numerous significant empirical findings. The outcome of this study differs significantly from that of50. They demonstrate the opposite association between environmental legislation and CO2 emissions utilizing an autoregressive distributed lag model, which cannot calculate the connection’s geographical variations. A win-win arrangement among the parties can be achieved mainly through economic and environmental regulations51.

Environmental regulations can force producing businesses to control CO2 emissions by incorporating negative externalities into manufacturing expenses. Based on the Coase Theorem, sustainable development is easily achievable with zero transaction expenses. However, transaction fees exist in actual manufacturing, of course. Thus, as a guarantee, a strong incentive structure is needed to accomplish the sustainable growth of the logistics industry. Pollution fines are one of the more established and versatile types of environmental regulations. China’s standard pollutant discharge fee has climbed dramatically since 2007. The price of pollution emissions has significantly increased, and incentives for cleaner air have risen and enhanced. Manufacturing enterprises have more incentives to cut CO2 emissions as additional environmental expenses are gathered52. According to statistics, the lower 10th percentile group experienced an average rise rate in sewage charges between 2005 and 2019. The bottom 10th percentile grouping has the fastest growing sewage costs, forcing the local logistics industry to upturn funding for apparatus advancements and usage of energy improvement to cut CO2 emissions.

According to53, they cannot identify the variations in the influence of obligatory CO2 emissions rules on the environment. The varying numbers of ecological decisions can be utilized to clarify the heterogeneous effects of required environmental regulations on interprovincial CO2. The creation and environmental restrictions that are necessary are strictly implemented and are an effective way to control businesses that produce pollution. National and local protective legislation and environmental regulations are among the mandatory environmental regulations reference points52.

More investment in sustainable development and protecting the environment to achieve environmental regulations, which will reduce pollution emissions. Businesses that release more significant amounts of waste than allowed will face administrative penalties from environmental supervision departments. Administrative agencies use penalties to compel businesses to adopt environmentally friendly practices and lower pollutant emissions. The quickest pace of increase in the number of environmental decrees is observed in the 25th–50th percentile group. The swiftly rising environmental regulations compel the regional logistics sector to increase environmental spending, promoting decreased CO2 emissions52.

This outcome differs from54 research. Using a threshold regression model, they find a positive U-shaped connection between environmental legislation and EE using a nonlinear perspective. The primary cause is the disparity in the empirical models that were employed. Investment in differentiated R&D could clarify the outcome of this manuscript. Findings in OECD nations indicate that composite fiscal decentralization (FD) considerably reduces carbon emissions only at medium to high (5th–9th) emissions quantiles. Conversely, green innovation lowers carbon emissions from lower to medium (1st–5th) emissions quantiles. Institutional changes enhance environmental sustainability across all emissions quantiles (1st–9th). The emissions-reducing impact of composite FD, green innovation, and institutional governance is most pronounced at elevated emissions quantiles and least significant at diminished emissions quantiles55.

This outcome differs substantially from56 findings. They identify that by employing generalized estimations of times, energy efficiency gains are not significantly impacted by mandated environmental regulations, primarily due to variations in environmental regulations between provinces. The mandated environmental regulations compel producing businesses to adhere to emission requirements through administrative measures. Due to environmental regulations, businesses now face higher costs to reduce CO2 emissions57. Businesses that discharge pollutants above the required level will face severe negative consequences from mandatory environmental legislation, including the revocation of company permits, the suspension of manufacturing, and harsh financial penalties. Companies have boosted their investments in pollution control in response to mandated environmental regulations for reducing emissions and possible uses of patented technology57. The group of lower 10th quantiles comprises the provinces of Heilongjiang, Yunnan, and Xinjiang. These regions’ economic growth (GDP) degree is less advanced than economically developed provinces. Within the bottom 10th quantile group, environmental regulations have increased significantly in response to the increasing need for environmental governance. Local businesses have increased the money they invest in emission- and energy-reducing equipment. Thus, the lowest 10th quantile group is more affected by statutory environmental regulations regarding energy efficiency.

Conclusion

This study explores the nuanced impact of mandatory and incentive-based environmental regulations on CO2 emissions and energy efficiency within China’s logistics sector. Employing quantile regression techniques on panel data spanning 30 provinces from 2005 to 2019, the findings underscore the critical role of environmental governance in mitigating emissions and promoting energy efficiency in this high-impact industry. The results reveal several pivotal insights that provide actionable implications for policymakers, industry stakeholders, and researchers.

Mandatory environmental regulations (MERP) are particularly effective in reducing CO2 emissions in regions with lower to moderate pollution levels, as observed in provinces within the 25th to 50th percentile of emissions. These regulations leverage strict enforcement mechanisms, such as penalties for non-compliance, which compel businesses to adopt more environmentally friendly practices. Provinces like Ningxia, Qinghai, and Hainan demonstrate significant reductions in emissions, highlighting the importance of stringent regulatory frameworks for emission mitigation. Conversely, incentive-based environmental regulations (IER) show a pronounced impact on improving energy efficiency, particularly in higher-performing regions (50th–75th and 75th–90th percentiles). These regions benefit from policies like subsidies and tax incentives that encourage investment in green technologies and R&D. Provinces such as Yunnan, Heilongjiang, and Xinjiang exhibit enhanced energy efficiency due to these targeted incentive programs, emphasizing the effectiveness of fostering innovation and technological adoption.