Abstract

Serological typing of MNS polymorphic antigens – M, N, S and s – remains a fundamental technique in transfusion medicine and prenatal care, providing essential information for matching blood donors and recipients and managing haemolytic disease. Although this method is well proven and routinely used, it is not a comprehensive solution, as it has several weaknesses. Alternatively, multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a commonly used genotyping tool due to its potency and ability to amplify several DNA targets simultaneously in a single reaction. In this work, we aimed to develop multiplex PCR and evaluate its performance for GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S, and GYPB*s allele identification using serological and DNA sequencing methods. We also aimed to investigate the correlation between these alleles and Mia-associated hybrid glycophorins (GPs). Remarkably, multiplex PCR was well optimised, and the results aligned with serological phenotyping and DNA sequencing data with maximum accuracy and reliability; this confirmed our findings on its validity in predicting MNSs phenotypes. In addition, this work strongly demonstrates, for the first time, a moderate correlation between the GYPA*M/M and GYPB*s/s genotypes and Mia-associated hybrid GPs among Thai donors. Individuals with the GYPA*M/M and GYPB*s/s genotypes, predicted M + N − S− s + phenotypes, will thus most likely to express the Mi(a+) antigen. Nevertheless, further studies are required to validate these results and elucidate the underlying correlations.

Keywords: MNS blood group system, Multiplex PCR, Red cell genotyping, Mia-associated hybrid glycophorins, Genetic variability

Subject terms: Molecular medicine, Genetics research, Genotype

Introduction

The immunised antibodies against the first two antigens – M (MNS1) and N (MNS2) – of the MNS blood group system were found in rabbits injected with human red blood cells (RBCs) in 1927, aside from the A and B antigens first discovered by Landsteiner and Levine1. In 1947, an alloantibody recognising the S antigen (MNS3) discovered an antigen related to M and N2. Although the relationship between MN and S was obviously not allelic, it could have resulted from very closely linked loci3. Four years later, the s antigen (MNS4), antithetical to S, was identified4, and family investigations subsequently confirmed the close linkage between MN and Ss5.

The MNS blood group system (International Society of Blood Transfusion, ISBT002) is a complex and diverse blood group system that currently comprises 50 antigens, numbered MNS1 through MNS506. These antigens can be categorised as four polymorphic, 10 high- and 36 low-frequency antigens, and they are carried on glycophorin A (GPA), glycophorin B (GPB), or variant glycophorins (GPs)3,6. MNSs are polymorphic in all populations tested3: the frequencies of the common phenotypes in Caucasian individuals are M + N + S + s + 24%, M + N + S− s + 22%, M − N + S − s + 15%, respectively7; in Blacks, they are M + N + S− s + 33%, M − N + S − s + 19%, M + N − S− s + 16%, respectively7; and in Thais, they are M + N + S− s + 40.35%, M + N − S− s + 35.96%, M + N − S + s + 8.11%, respectively8. Although it is known that numerous low-frequency antigens arise from amino acid substitutions and/or glycosylation alterations in GPA or GPB, most of these antigens are associated with aberrant hybrid GPs that contain a part of both GPA and GPB3. Mia (MNS7) is an antigen comprising eight hybrid GPs. Their frequencies are rare in most populations (< 0.01%); in contrast, higher frequencies are observed in Asian populations, especially in Taiwanese (7.3%)9 and Thai (9.7%)10 individuals. Antigens expressed on GPA, GPB and hybrid GPs are immunogenic and might trigger an immune response when exposed to individuals lacking these antigens3. Specific antibodies to the above-mentioned MNS antigens are thought to be clinically significant regarding reported cases of haemolytic disease of the foetus and newborn (HDFN) and haemolytic transfusion reactions (HTRs), which might be immediate or delayed3,7.

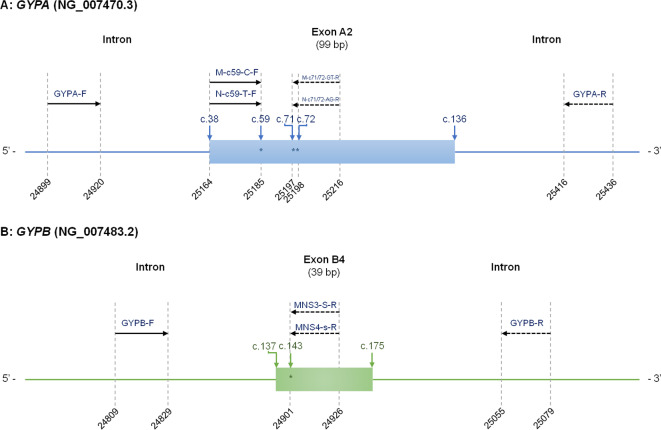

M and N determinants are carried on GPA, which are serologically represented as the MN blood groups. The amino acid composition of the extracellular tip of GPA exhibits polymorphic variation at positions 20 and 24 (counting from the translation-initiating methionine). The p.Ser20Leu polymorphism arises from a single nucleotide variant (SNV), c.59 C > T (TCA/TTA); the p.Gly24Glu polymorphism arises from two SNVs, c.71G > A and c.72T > G (GGT/GAG) in the GYPA*M and GYPA*N of GYPA exon A2, respectively11. While S and s are carried on GPB, position 48 is represented by an amino acid substitution: Met and Thr are critical for the S and s antigens, respectively (GYPB*S, c.143T; GYPB*s, c.143 C of GYPB exon B4)12. Unequal crossing over and gene conversion are the two main mechanisms forming variant hybrid GPs that result in eight different Mia-positive hybrid GPs – GP.Vw, GP.Hut, GP.Mur, GP.Hop, GP.Bun, GP.HF, GP.Kip, and GP.MOT. Of these, GP.Mur is the most common, particularly in Thailand, while the others are restricted to a particular region or ethnicity13.

The hemagglutination technique is a standard method used to identify blood group antigens. Despite this, there are limitations to serological typing, including the following: distinguishing recently transfused patients with accurate phenotypes, displaying false positive reactions in individuals with a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT), and lacking the availability of reliable typing reagents14. Nevertheless, in circumstances in which serological techniques are unable to identify blood groups, emerging technologies for blood group genotyping may provide an additional alternative approach15. Most PCR sequence-specific primers (PCR-SSP) are based on the detection of independently known SNVs. Nathalang O, et al. developed two sets of primers targeting the GYPB*S and GYPB*s alleles for Thailand using an in-house PCR-SSP16. This reduced the possibility of errors arising from independent reactions and simplified the process of interpreting outcomes. By enabling the simultaneous detection of multiple targets within a single target, multiplex PCR increases the accuracy of data handling and is also time- and cost-effective. Intharanut K, et al. designed multiplex PCR to detect seven alleles and Mia-associated hybrid GPs17. The first primer set produces four types of amplicons, depending on the gene present and specified for FY*A, JK*A, RHCE*e, and DI*A. The second set of primers targets FY*B, JK*B, RHCE*E alleles, and hybrid GPs17. However, GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S, and GYPB*s have different nucleotide sequence lengths; this encourages them to be distinct from other sets of primers in multiplex PCRs that have not yet been set up in Thailand or other countries. Likewise, it is undetermined which alleles producing MNSs antigens and commonly observed Mia-associated hybrid GPs in Thais are correlated. The aim of this study was to develop multiplex PCR and assess its efficacy in comparison to serological tests for the detection of the GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s alleles. In addition, we aimed to target those alleles expressing MNSs antigens to illustrate the associations between their alleles and Mia-associated hybrid GPs.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and preparation

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University (HREC-TUSc), Pathumtani, Thailand, obtained approval for this study in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (COE No. 016/2567), and written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants. Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-anticoagulated samples were randomly collected from the whole blood of 150 unrelated healthy Thai blood donors at the Blood Bank at Thammasat University Hospital (TUH) in Pathumtani, Central Thailand, between May and June 2024. Genomic DNA was extracted from these samples using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit, according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). The samples were then kept at − 20 °C until genotyping. An additional 415 DNA samples from healthy, unrelated Thai blood donors were randomly collected from our inventory of DNA banks (TUH). All donors provided demographic information for themselves, their parents, and their grandparents, including family names, birthplace, residence, ethnic self-identity, and spoken language. These samples were subsequently examined using in-house multiplex PCR.

M, N, S, and s phenotyping

A total of 150 blood samples were tested for M, N, S, and s antigen positivity using the conventional tube technique (CTT). The commercially available monoclonal anti-M (Clone M-11H2) and anti-N (Clone 1422C7) reagents (CE-Immundiagnostika, Eschelbronn, Germany) were employed for the M and N phenotyping of the samples according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An indirect antiglobulin test (IAT) was used to examine all samples using commercially available polyclonal anti-S and anti-s (CE-Immundiagnostika, Eschelbronn, Germany). DAT was additionally performed on all samples that had a positive IAT result to rule out any false-positive results.

DNA sequencing

The multiplex PCR results were confirmed by sequencing the genomic DNA of 100 samples (approximately 20% of the total samples), which were randomly repeated. PCR amplification of the GYPA and GYPB target genes yielded fragments of 538 and 271 bps, respectively. While the amplified segments of the gene of GYPB encompassed SNV c.143 C > T, the amplified GYPA gene fragment had SNVs c.59 C > T, c.71G > A and c.72T > G. All genes targeted during PCR amplification for DNA sequencing were the same as those in the PCR mixtures and conditions. The primer pair sequences and final concentrations used to generate each gene target are shown in Table 1. Each PCR reaction comprised combining forward and reverse primers with 100 ng of genomic DNA and a 2× PCR reaction mixture (Phusion High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). The T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was utilised for thermocycling with the indicated multiplex PCR protocol. Afterward, the targeted amplicons were purified using a gel extraction kit (GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the eluted fragments were sequenced employing these PCR primers using the Sanger method (Celemics, Inc., Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Table 1.

Particulars of the multiplex PCR primers, target alleles, and product sizes.

| Primer name | Sequence (5’ to 3’) | Target allele | Amplicon size (bp) | Specific antigen | Final Concentration (µmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mix A | |||||

| GYPA-F | CAGATGAGAAAACCAAGGCACG | GYPA | 538 | GYPA | 1.000 |

| GYPA-R | TCAGAGGCAAGAATTCCTCCA | 1.000 | |||

| GYPA-F | CAGATGAGAAAACCAAGGCACG | GYPA*M | 318 | M | 1.000 |

| M-c71/72-GT-R | TGAAGTGTGCATTGCCACAC | 0.125 | |||

| M-c59-C-F | CAATTGTGAGCATATCAGCATC | GYPA*M | 273 | M | 0.375 |

| GYPA-R | TCAGAGGCAAGAATTCCTCCA | 1.000 | |||

| GYPB-F16 | CCCGCAGAACAGTTTGATTCC | GYPB*S | 118 | S | 0.500 |

| MNS3-S-R16 | AGTGAAACGATGGACAAGTTGTCCCA | 0.500 | |||

| Mix B | |||||

| GYPA-F | CAGATGAGAAAACCAAGGCACG | GYPA | 538 | GYPA | 1.000 |

| GYPA-R | TCAGAGGCAAGAATTCCTCCA | 1.000 | |||

| GYPA-F | CAGATGAGAAAACCAAGGCACG | GYPA*N | 318 | N | 1.000 |

| N-c71/72-AG-R | TGAAGTGTGCATTGCCACCT | 0.125 | |||

| N-c59-T-F | CAATTGTGAGCATATCAGCATT | GYPA*N | 273 | N | 0.375 |

| GYPA-R | TCAGAGGCAAGAATTCCTCCA | 1.000 | |||

| GYPB-F16 | CCCGCAGAACAGTTTGATTCC | GYPB*s | 118 | s | 0.500 |

| MNS4-s-R16 | AGTGAAACGATGGACAAGTTGTCCCG | 0.500 | |||

| Internal control | |||||

| HGH-1070-F18 | GCCTTCCCAACCATTCCCTTA | HGH | 1,070 | HGH | 0.500 |

| HGH-1070-R18 | GTCCATGTCCTTCCTGAAGCA | 0.500 | |||

| DNA Sequencing | |||||

| GYPA-F | CAGATGAGAAAACCAAGGCACG | GYPA | 538 | GYPA | 0.750 |

| GYPA-R | TCAGAGGCAAGAATTCCTCCA | 0.750 | |||

| GYPB-F16 | CCCGCAGAACAGTTTGATTCC | GYPB | 271 | GYPB | 0.750 |

| GYPB-R16 | TTCTTTGTCTTTACAATTTCGTGTG | 0.750 | |||

*The nucleotides shown in bold indicate the sequence specificity of each allele.

Bp base pair, GYPA Glycophorins A, GYPB Glycophorins B, HGH Human growth hormone.

Mia-associated hybrid GPs typing by PCR-SSP

The PCR-SSP was employed to determine whether the Mia antigen was present or absent at the molecular level. In brief, two sets of primers specific to the GYP(A-B-A) and GYP(B-A-B) hybrid genes were used, together with the internal control primers specific to HGH. The fragments of the set of GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun and GYP*HF, plus the fragment of the other set of GYP*Vw, were amplified to find potentially predicted Mia-associated hybrid GPs in accordance with previously described conditions18.

Oligonucleotides specific to the M, N, S, and s antigens

Table 1 displays the primer combination sequences utilised in the two primer mixes (MIX A and MIX B), the identified allele, the amplicon size and the specific antigens of each mixture. To develop a shortlist of S and s antigen-specific PCR primers and internal control primers, several pairs of primers were selected from the published literature16,19. In addition, we employed the Primer3Plus software to design PCR primers based on the distinct sequences of the remaining alleles20. Figure 1 illustrates a schematic representation of the primers used in this study, along with the position of the intron and exon sequences. All unmodified DNA oligonucleotides were purchased (U2Bio Co., Ltd., Thailand) with standard high affinity purification and kept refrigerated at 4 °C.

Fig. 1.

Schematic depiction of the GYPA (A) and GYPB (B) gene sections illustrating the locations of the polymorphisms (*) and the oligonucleotide primers used in this study. The intron is indicated by a thin line, and exon sequences belonging to the gene-based genomic reference sequences of GYPA (NG_007470.3) and GYPB (NG_007483.2) are displayed as blue and green boxes, respectively. The numbering scheme is contingent on the reference genes. The GYPB-R primer was used for DNA sequencing but was not included in the multiplex PCR testing

Multiplex PCR protocol

The multiplex PCR for the M, N, S and s genotyping comprised two reaction mixes (A and B) of each distinct amplification target for each mix, as demonstrated in Table 1. Each reaction mix contained four distinct primer pairs along with one HGH-specific primer pair serving as the internal control. The PCR reaction was carried out in 20 µL reaction mixtures that contained the 2× PCR reaction mixture (Green Hot Start PCR Master Mix, Biotechrabbit GmbH, Hennigsdorf, Germany), each allele-specific primer pair, 50–150 ng of template genomic DNA, and HGH-internal control primers. The final concentrations of each primer used in the multiplex PCR are presented in Table 1. Multiplex PCR was performed on a T100 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). Thermal cycling started with a 30 s incubation step at 95 °C for polymerase activation, followed by 10 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C for DNA denaturing and 1 min at 69 °C for annealing and extension, followed by 25 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C for DNA denaturing, 50 s at 62 °C for annealing, and 30 s at 72 °C for extension and a final extension of 5 min at 72 °C.

The PCR products (20 µL) were then investigated by electrophoresis using 1.5% agarose gel stained with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). After being electrophoresed in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer at 100 volts, they were scrutinised for specific amplicons using a blue light transilluminator. The known DNA controls throughout each PCR batch were GYPA*M/M and GYPB*S/s (M + N − S + s+), GYPA*M/N and GYPB*S/S (M + N + S + s−) and GYPA*N/N and GYPB*s/s (M − N + S − s+), respectively, providing positive and negative inspections.

Evaluation of the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of the multiplex PCR protocol

To verify the reliability and validity of the developed multiplex PCR, the technicians were blinded to the results of the DNA sequencing and phenotyping. Discrepancies between the genotyping and phenotyping results from the multiplex PCR, if any, were confirmed using standard DNA sequencing. To verify repeatability under testing conditions identical to those of the initial test, multiplex PCR genotyping was carried out on 100 randomly picked samples from the 150 known MNSs typing groups, and their results were sequenced to validate our in-house multiplex PCR method. Following this, the sensitivity of the multiplex PCR detection was investigated using amounts ranging from 10 to 300 ng/µL with both known positive and negative controls.

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of the observed phenotypes was characterised using descriptive statistics and presented as percentages. The genotype and allele frequencies were determined by direct counting. The observed genotype frequencies were compared to the expected genotypes under Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using the chi-square (χ2) test. The distribution of observed allele frequency counts among Thais was compared with the other population frequencies to investigate any differences using the χ2 test of homogeneity. Moreover, the strength of the correlation was determined by the correlation coefficient Phi. The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS, Version 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with the threshold for statistical significance set at p ≤ .05.

Results

MNSs phenotypes in Thai blood donors

We examined 150 donor blood samples in our study to determine the phenotypes of this blood group system and the prevalence of MNSs antigens. Table 2 shows the frequencies of common MNSs antigens and phenotypes. The M and s antigens were the most detected antigens found out of 136 samples (0.907) and 149 samples (0.993); on the other hand, the N and S antigens were the least frequently found antigens, appearing in 107 samples (0.713) and 20 samples (0.133), respectively. Six phenotypes were observed in the population. M + N + S− s+ (78/150, 0.520) was the most frequent phenotype of the MNS blood group, whereas M + N + S + s− (1/150, 0.007) was the least frequent phenotype. The frequency of the four phenotypes – M + N − S− s+, M + N + S + s+, M − N + S − s + and M + N − S + s+ – was 0.253, 0.093, 0.093 and 0.033, respectively. In the current investigation, the other six phenotypes were not observed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics and frequencies of common MNSs antigens and phenotypes in Thai blood donors.

| Phenotype/Antigen | Number | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| M + N– S + s– | 0 | 0.000 |

| M + N– S + s+ | 5 | 0.033 |

| M + N– S– s+ | 38 | 0.253 |

| M + N– S– s– | 0 | 0.000 |

| M + N + S + s– | 1 | 0.007 |

| M + N + S + s+ | 14 | 0.093 |

| M + N + S– s+ | 78 | 0.520 |

| M + N + S– s– | 0 | 0.000 |

| M– N + S + s– | 0 | 0.000 |

| M– N + S + s+ | 0 | 0.000 |

| M– N + S– s+ | 14 | 0.093 |

| M– N + S– s– | 0 | 0.000 |

| Total | 150 | 1.000 |

| M+ | 136 | 0.907 |

| N+ | 107 | 0.713 |

| S+ | 20 | 0.133 |

| s+ | 149 | 0.993 |

Multiplex PCR for MNSs genotyping

The outcomes of a double-tube multiplex PCR were used to discriminate between four alleles for MNSs antigens – GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s. Multiplex Mix A could be employed to distinguish both the GYPA*M and GYPB*S alleles, while multiplex Mix B could be used to distinguish the GYPA*N and GYPB*s alleles. The GYPA gene was amplified (538 bp) by the designed primers with effectiveness, as were the GYPA*M or GYPA*N alleles (318 bp), which were separated by the nucleotide changes c.71G > A and c.72T > G, the GYPA*M or GYPA*N alleles (273 bp), which were separated by the nucleotide change c.59 C > T and the GYPB*S or GYPB*s allele (118 bp), which was amplified by the c.143 C > T nucleotide change. The HGH internal control displayed an expected band of 1,070 bp in each multiplex set, indicating that PCR amplification was completed effectively. Agarose gel electrophoresis was used to identify PCR products of different sizes for each target gene and allele, as shown in Fig. 2. Multiplex PCR results for representative DNA control samples of four phenotypes are displayed in Fig. 2, containing M + N − S− s+ (Lanes 001 A and 001B), M + N + S− s+ (Lanes 002 A and 002B), M − N + S + s− (Lanes 003 A and 003B), M + N + S + s+ (Lanes 004 A and 004B) and non-template controls (Lanes NCA and NCB). The specific amplification of the desired PCR products through all primer pairs was established by gel electrophoresis and observed amplicons. The results are compiled for each genotype in Table 3.

Fig. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis results for multiplex PCR with DNA control samples of four phenotypes. Lanes 001A and 001B, M+ N− S− s+; Lanes 002A and 002B, M+ N+ S− s+; Lanes 003A and 003B, M− N+ S+ s−; Lanes 004A and 004B, M+ N+ S+ s+; Lanes NCA and NCB, non-template controls; Lane M: DNA ladder marker (GeneRuler 100 bp Plus; Fermentas, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Gene and allele markers corresponding to the amplified fragments are indicated on the right. Molecular sizes are displayed (in bp) on the left and right.

Table 3.

Multiplex PCR evaluation with representative possible genotypes.

| Genotype | Multiplex Mix A—gene/allele (bp) | Multiplex Mix B—gene/allele (bp) | Predicted Phenotype | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGH | GYPA | GYPA*M, c.71T and c.72T | GYPA*M, c.59 C | GYPB*S, c.143T | HGH | GYPA | GYPA*N, c.71 A and c.72G | GYPA*N, c.59 C | GYPB*s, c.143 C | ||

| (1,070) | (538) | (318) | (273) | (118) | (1,070) | (538) | (318) | (273) | (118) | ||

| GYPA*M/M, GYPB*S/S | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | M + N– S + s– |

| GYPA*M/M, GYPB*S/s | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | M + N– S + s+ |

| GYPA*M/M, GYPB*s/s | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | M + N– S– s+ |

| GYPA*M/N, GYPB*S/S | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | – | M + N + S + s– |

| GYPA*M/N, GYPB*S/s | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | M + N + S + s+ |

| GYPA*M/N, GYPB*s/s | + | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | M + N + S– s+ |

| GYPA*N/N, GYPB*S/S | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | M– N + S + s– |

| GYPA*N/N, GYPB*S/s | + | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | M– N + S + s+ |

| GYPA*N/N, GYPB*s/s | + | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | M– N + S– s+ |

Bp base pair, GYPA Glycophorins A, GYPB Glycophorins B, HGH Human growth hormone.

Evaluation of the developed multiplex PCR

DNA samples from known phenotypes were employed to verify the devised multiplex PCR method, and multiplex reaction contamination was evaluated using water as a non-template control. The multiplex PCR was conducted through 150 known donor DNA samples, and the findings of DNA sequencing and MNSs antigen typing by CTT were compared with each corresponding amplicon. The multiplex PCR genotyping results were entirely congruent with the standard phenotyping and predicting phenotypes from genotyping results. To assess the repeatability of our method, multiplex PCR was performed on 100 randomly selected DNA samples from the 150 known MNSs typing groups. The results of our test for repeatability revealed identical outcomes to the inaugural test. Additionally, the positive and negative DNA controls, along with DNA amounts ranging from 10 to 300 ng/µL, were used to assess multiplex PCR sensitivity. Samples with DNA amounts as low as 25 ng/µL were successfully detected through specific amplicons. Consequently, in the cohort of 150 Thai donor DNA samples, our multiplex PCR test demonstrated robust sensitivity, specificity and repeatability.

Implementing the devised multiplex PCR and comparing their frequencies

The 565 DNA samples from Thais – 150 with known MNSs and 415 with unknown MNSs typing – were genotyped using the validated multiplex PCR. The genotype and allele frequencies of these samples are shown in Table 4. The minor allele frequency (MAF) for GYPA*N and GYPB*S was determined in all groups to be approximately 30–40% and 7%, respectively, and the genotype frequencies observed in each group under investigation were computed in accordance with the HWE test. The HWE test revealed that the observed genotype frequencies of GYPA*M and GYPA*N in the overall population under investigation were inconsistent (p < .05), whereas GYPB*S and GYPB*s were consistent (p > .05).

Table 4.

Genotype, allele for GYPA and GYPB, minor allele frequency, and HWE among Thai blood donors.

| Total samples (n = 565) | Known MNSs typing (n = 150) | Unknown MNSs typing (n = 415) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GYPA and GYPB genotype frequency (n) | |||

| *M/M, *S/S | 0.000 (0) | 0.000 (0) | 0.000 (0) |

| *M/M, *S/s | 0.048 (27) | 0.033 (5) | 0.053 (22) |

| *M/M, *s/s | 0.361 (204) | 0.253 (38) | 0.400 (166) |

| *M/N, *S/S | 0.007 (4) | 0.007 (1) | 0.007 (3) |

| *M/N, *S/s | 0.076 (43) | 0.093 (14) | 0.070 (29) |

| *M/N, *s/s | 0.439 (248) | 0.520 (78) | 0.410 (170) |

| *N/N, *S/S | 0.002 (1) | 0.000 (0) | 0.002 (1) |

| *N/N, *S/s | 0.004 (2) | 0.000 (0) | 0.005 (2) |

| *N/N, *s/s | 0.064 (36) | 0.093 (14) | 0.053 (22) |

| Allele frequency (n) | |||

| GYPA*M | 0.670 (757) | 0.597 (179) | 0.696 (578) |

| GYPA*N | 0.330 (373) | 0.403 (121) | 0.304 (252) |

| MAF | 0.330 | 0.403 | 0.304 |

| HWE (χ2: DF = 2, p-value) | 18.429, 0.001 | 12.461, 0.002 | 9.458, 0.009 |

| GYPB*S | 0.073 (82) | 0.070 (21) | 0.073 (61) |

| GYPB*s | 0.927 (1,048) | 0.930 (279) | 0.927 (769) |

| MAF | 0.073 | 0.070 | 0.073 |

| HWE (χ2: DF = 2, p-value) | 1.588, 0.452 | 0.110, 0.946 | 1.630, 0.443 |

GYPA Glycophorins A, GYPB Glycophorins B, HWE Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

In total, the GYPA*M/N, GYPB*s/s, the most common genotype, was observed in 248 donors (0.439) with the predicted M + N + S− s + phenotype. Following this, 204 donors (0.361) had the GYPA*M/M, GYPB*s/s genotype with the predicted M + N − S− s + phenotype, and 43 donors (0.076) had the GYPA*M/N, GYPB*S/s genotype with the predicted M + N + S + s + phenotype. The GYPA*M/M, GYPB*S/S genotype went undetected in the study. In addition, GYPA*M and GYPB*s allele frequencies were established as belonging to the two most predominant alleles, occurring at 0.670 and 0.927, respectively (Table 4).

We identified four alleles encountered within two genes in the 565 Thai donors, the majority of which were variants with the GYPB*s allele. Subsequently, allele frequencies observed in the Thai population were compared with those reported in the other 12 ethnic groups (Fig. 3)21,22. Allele frequencies of three variants – GYPA c.59 C > T, c.71G > A and c.72T > G – encoding GYPA*M and GYPA*N among Thais did not differ significantly among the Alaska Native/Aleut and Hispanic groups (p > .05). In contrast to Thais versus 10 other populations – African American, American Native, Caucasian, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Japanese, Korean, South Asian, and Southeast Asian – there were notable differences (p < .05). Another variant (GYPB c.143 C > T) was not different among Asians (Filipino, Japanese and Korean) but different from the remaining nine populations.

Fig. 3.

The allele frequencies of the variants were compared between 12 distinct ethnic groups and Thais, using data obtained from previous studies. The symbols ●, ○, ▲, △, ■, □, ◆, ◇, ⬣, , ▼, ▽ and ★ denote allele frequencies of African American, American Native, Alaska Native/Aleut, Caucasian, Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, Japanese, Korean, South Asian, Southeast Asian, and Thai, respectively. The allele frequencies that were significantly different (p < .05) between Thai and other populations are displayed in red, while the non-statistically significant differences are displayed in blue

Estimating the allelic correlations between Mia-associated hybrid GPs and other alleles, genotypes, and haplotypes of MNS

After we implemented the method for Mia-associated hybrid GP detection, the positive results of either or both sets of PCR-SSP could predict the Mi(a+) phenotype among Thai donors. Of the 565 Thai blood donors, only 67 (11.86%) tested positive after applying the set of primers designed specifically for the GYP*Hut, GYP*Mur, GYP*Hop, GYP*Bun and GYP*HF tests. Another set of PCR-SSP did not detect any GYP*Vw in any of the samples. Phi correlations were calculated for Mia-associated hybrid GPs among the 23 alleles, genotypes and haplotypes of MNS (Fig. 4). The presence of Mia-associated hybrid GPs primarily correlated with the GYPA*M allele (p = .018, Phi = 0.100), whereas they did not predict the GYPB*s allele (p = .300). In our investigation, the moderate correlation with the GYPA*M/M, GYPB*s/s genotype showed the highest significance (p = .003, Phi = 0.123) as soon as Mia-associated hybrid GPs were present.

Fig. 4.

Phi correlation heat map: Blue denotes a positive correlation (darker blue indicates a stronger correlation); green denotes a negative correlation. The phi index ranged from −1 to +1. Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < .05 level. NA = not available.

Discussion

In practice, serological methods have broader use and persist as the gold standard for routine immunohematology workups. Blood transfusion safety is greatly enhanced if molecular methods are used to proceed further with the anticipated phenotyping and reliably identify the antigen in situations in which serology testing is not executed. The initial objective of the study was to develop multiplex PCR and evaluate its effectiveness in detecting GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s alleles in tandem with serological testing. We used CTT to investigate the frequency of MNSs phenotypes among Thai blood donors in this sample cohort. The findings of the study revealed that their frequencies in this Thai cohort were similar to previously reported occurrences in Thailand, wherein M + N + S− s + was typically detected (52.00% vs. 40.35%)8. Similarly, they were comparable with those reported in Blacks7, Europeans3 and African Americans3, with percentages of 33.0%, 22.6% and 33.4%, respectively. Studies on MNS phenotyping in different regions and ethnic groups exhibit distinctive patterns that highlight the diverse genetic makeup of the general population. These variations underscore the significance of customised blood transfusion protocols in various geographical areas to ensure compatibility and minimise immunological complications.

The dosage effect, in which the strength of antigen–antibody interactions varies depending on the number of antigen copies present on RBCs, is challenging to profile antigens in the MNS blood group system – M, N, S and s3. Beyond this phenomenon, there are additionally various types of limitations to serological phenotyping, including the occasional yield of false positive results due to factors that can interfere with donor RBCs in the patient’s blood circulation and existing positive DAT, the inability to distinguish between auto and alloantibodies and phenotypic discrepancies (weak or missing)23. Blood group genotyping, therefore, enables one to address many of the limitations of serological phenotyping by providing comprehensive, accurate and reproducible results. In the current work, we built an in-house multiplex PCR that could potentially be used to predict MNSs phenotypes by identifying the GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s alleles. The devised multiplex PCR genotyping outcomes were validated by the complete agreement between the genotyping and phenotyping results as well as standard DNA sequencing. Furthermore, this genotyping approach highlights extraordinarily high fidelity with reliable findings, even at low DNA concentrations (25 ng/µL). Their genotyping with 100 randomly selected donors exhibited 100% concordance between the multiplex PCR and DNA sequencing results and the initial experiments, demonstrating reproducibility. Consequently, successful validation has been rendered achievable according to the multiplex PCR’s noteworthy consistency and reproducibility.

In spite of the application of this multiplex PCR, red cells belonging to individuals who are homozygous for the extremely rare MNS-null gene – MK, which produces neither M nor N antigens – could be identified. Although the loss occurs throughout both genes (GYPA and GYPB), apart from exon A1 and the upstream promoter region of GYPA24, our multiplex PCR comprised specific primers for GYPA that covered exon A2. Hence, the expected outcomes should either display internal control bands only or no bands that reflect the specific primers of GYPA and GYPB3. In addition, individuals who have the extremely rare phenotype in Thais, S − s− U−, which is caused by homozygosity for a deletion of GYPB encompassing exons B2–B6, lack GPB yet express the MN antigen normally25. Multiplex PCR should yield the expected results, including the presence of internal control bands and normal bands reflecting specific primers for the GYPA*M and/or GYPA*N alleles. Considering the other rare En(a−) phenotype, their cells express normal Ss antigens but do not express any of the several GPA-borne high-frequency antigens, which initially implicated a loss encompassing GYPA exons A2–A7 and GYPB exon B13. A Thai patient who displayed this phenotype was noted; the patient was homozygous for GYPA*M c.295delG (p.Val99Ter)26. The inability of multiplex PCR to detect the mutation implies that En(a−) was not expected to be distinct from the MN antigen prediction. As this issue regarding this method might have occurred in only a small number of cases, requests for additional investigation should be taken into consideration to perform DNA sequencing and analysis of these genes. The method invented also exclusively depends on the detection of those particular DNA sequences, thereby providing an ideal test for the GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s alleles. Comparing this multiplex PCR to genotyping with commercially available kits, the cost per test is approximately USD 4.50, which is a 70-fold reduction. The disproportionately high cost and combination of these alleles with other alleles in commercially available kits have encouraged the development of this multiplex PCR typing approach for internal use, which may be used routinely for genotyping21,22. Furthermore, we would have continued to type an extensive number of patients and donors into our populations, particularly for patients who receive transfusions frequently, such as those with thalassemia and chronic renal disease of Thai ancestry who are susceptible to red cell alloimmunisation and who regularly donate blood27. Thus, genotyping these patients and donors has assisted in clarifying the causes underlying the chronic alloimmunisation observed in some patients. It may also be a crucial strategy for enhancing therapeutic treatments and their outcomes. As the method progresses and the number of genotyped donors expands, it is essential to continue assessing the reliability, effectiveness and financial consequences of implementing risk-based patient strategies for genotyping.

In a Thai belonging, this is the first report of allele and genotype frequencies for GYPA*M, GYPA*N, GYPB*S and GYPB*s. As demonstrated by GYPA*M and GYPA*N, the highly discordant regions within GYPA were not in HWE; this is possibly because of the sample size, allele frequencies and cohort study. Minelli et al. proposed that estimates of alpha (α) from small studies could have been more vulnerable to sampling error; however, even after accounting for this, there is strong evidence that sample size has an inverse relationship with the absolute magnitude of the underlying actual variations from HWE28. Nevertheless, all population tests evaluated were found to be within the HWE in GYPB*S and GYPB*s, suggesting that in the absence of external disruption, the samples employed remained stable throughout generations. The observed GYPA*N and GYPB*S alleles in these groups likewise had MAFs of around 30–40% and 7%, respectively. Based on those with high MAFs, which typically occur at frequencies greater than 5%, it may be concluded that this variation is common29. Although both GYPA*M and GYPB*s constitute the predominant alleles across all ethnic groups, historical, environmental and evolutionary factors can cause significant variances in their allele frequencies across various ethnic backgrounds. This is the first study that we are aware of regarding demographic differences for Thai individuals based on GYPA*M and GYPA*N frequencies. The χ2 test for homogeneity was used to evaluate differences and determine whether the two groups had the same allelic distribution. Widely varying and significant differences have been noted between Thai groups and 10 racial groups21,22. These variations are most likely caused by variations in the sample size and investigated markers on three SNVs. Within the genomic GYPB*S and GYPB*s regions, our findings are consistent with a previous report on Thais, where their frequencies in central Thais were similar to those of the Korean population and significantly different from those of other populations16. Comprehending the fluctuations in allele frequencies associated with the production of antibodies against red cell antigens is crucial for customising medical interventions and enhancing public health outcomes among heterogeneous populations. The data on allele frequencies in various populations from this study might be valuable as a resource for additional evaluation in establishing allele-match transfusion strategies for all transfusions before alloimmunisation occurs, particularly for chronic transfused patients; this is the ideal approach to prevent alloimmunisation30.

Most populations are recognised as having a low prevalence of the Mia antigen. However, Southeast Asians, particularly those in Thailand, have higher frequencies of occurrence13,17,18. The high percentage of Mia positivity (11.86%) in this cohort without GP.Vw is consistent with other findings that indicate the frequency of Mia positivity in Thai cohort distributions, ranging from 9.3–12.5%17,18,31. The Phi correlation index was calculated for Mia-associated hybrid GPs and other alleles, genotypes and haplotypes of MNS. In particular, the GYPA*M/N and GYPB*s/s genotypes were frequently observed in the Thai population; no correlation was noted with Mia-associated hybrid GPs. There was a statistically significant positive correlation solely between Mia-associated hybrid GPs and the GYPA*M allele, while the correlation was stronger for the GYPA*M/M, GYPB*s/s genotype, with a medium-strong value. Therefore, genetic profile information may offer a potent method for determining the genotypes underlying anti-Mia pre-existing patients. Occasionally, anti-Mia is not available, and M + N − S− s + donors should not be chosen for compatible blood findings in such patients due to possible Mi(a+) found in this phenotype. Further studies with larger samples are required to determine whether genotypes or alleles in the MNS blood group, if any, confer an association with Mia-associated hybrid GPs. Furthermore, understanding which alleles and genotypes correlate with one another has become crucial in fields including genetics, genomics and personalised medicine, as this highlights the genetic basis of traits and diseases32.

Currently, there are increasing reports of foetal haemolysis, HTRs, and newborn haemolysis caused by anti-Mia3,13. Consequently, the distribution frequency of this antigen and antibody has some therapeutic value for managing clinical blood transfusions and monitoring antibodies in patients and pregnant women. This study investigates the relationship between these MNS genotypes and Mia-associated hybrid GPs in the Thai population. The addition of Mia positive RBCs, which include MNS hybrid GPs positive, such as Mur/Mia antigen positive, is recommended for the routine clinical detection of irregular antibodies. In the lack of corresponding monoclonal reagents, the prevalent hybrid GPs blood types of MNS in blood donors may be identified using molecular biology techniques. Furthermore, our established multiplex PCR may predict the presence of Mia antigen given the notable association between the genotypes of GYPA*M/M and GYPB*s/s and the expression of Mia antigen on the corresponding RBCs. Essentially, patients who now or previously had anti-Mia must receive donor RBCs that tested negative for the corresponding antigen.

Conclusion

In summary, the simple, flexible, accurate, reliable and versatile MNS genotyping method – a two-tube multiplex PCR – reported in this study will expedite forward-genetics approaches, not only in polymorphic MNS antigens but also in other red cell antigen development, including clinically important red cell antigens. Furthermore, the findings of this study suggest a moderate association between Mia-associated hybrid GPs and the GYPA*M/M and GYPB*s/s genotype among Thai donors. The transformative impact of the red cell genotype information reported in this study should be useful in various medical and therapeutic settings, improving patient care and outcomes in transfusion medicine, prenatal care and chronic disease management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all donors and laboratory personnel for participation in the study.

Author contributions

T.K., and K.I. had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis; Concept and design: K.I.; Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: T.K., O.N., D.A., and K.I.; Drafting of the manuscript: T.K., and K.I.; Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: T.K., O.N., S.C., T.C., D.A., and K.I. Statistical analysis: K.I.; Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors. Supervision: O.N., and K.I.

Funding

This work was supported by the Thammasat University Research Fund, Contract No. TUFT 80/2567.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Landsteiner, K. & Levine, P. A. New Agglutinable factor differentiating Individual Human bloods. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med.24, 600–602 (1927). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh, R. J. & Montgomery, C. M. A new human iso-agglutinin subdividing the MN blood groups. Nature160, 505 (1947). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daniels, G. MNS blood group system in Human Blood Groups (ed Daniels, G.) 96–161 (Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, (2013).

- 4.Levine, P., Kuhmichel, A. B., Wigod, M. & Koch, E. A new blood factor, s, allelic to S. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med.78, 218–220 (1951). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanger, R. & Race, R. R. The MNSs blood group system. Am. J. Hum. Genet.3, 332–343 (1951). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT). Red cell immunogenetics and blood group terminology (2024).

- 7.Reid, M. E., Lomas-Francis, C. & Olsson, M. L. MNS blood group system in The Blood Group Antigen Facts book (eds Reid, M. E., Lomas-Francis, C. & Olsson, M. L.) 53–134 (Elsevier Academic, (2012).

- 8.Chandanayingyong, D., Sasaki, T. T. & Greenwalt, T. J. Blood Groups Thais Transfus.7, 269–276 (1967). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broadberry, R. E. & Lin, M. The incidence and significance of anti-mia in Taiwan. Transfusion34, 349–352 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandanyingyong, D. & Pejrachandra, S. Studies on the Miltenberger complex frequency in Thailand and family studies. Vox Sang. 28, 152–155 (1975). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siebert, P. D. & Fukuda, M. Isolation and characterization of human glycophorin a cDNA clones by a synthetic oligonucleotide approach: nucleotide sequence and mRNA structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 83, 1665–1669 (1986). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siebert, P. D. & Fukuda, M. Molecular cloning of a human glycophorin B cDNA: nucleotide sequence and genomic relationship to glycophorin A. Erratum in. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 84, 6735–6739 (1987). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez, G. H., Hyland, C. A. & Flower, R. L. Glycophorins and the MNS blood group system: a narrative review. Ann. Blood. 6, 39 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peyrard, T. Molecular tools for investigating immunohaematology problems. VOXS10, 31–38 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li, H. Y. & Guo, K. Blood Group Testing. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 827619 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nathalang, O. et al. Predicted S and s phenotypes from genotyping results among Thai populations to prevent transfusion-induced alloimmunization risks. Transfus. Apher Sci.57, 582–586 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Intharanut, K., Bejrachandra, S., Nathalang, S., Leetrakool, N. & Nathalang, O. Red cell genotyping by Multiplex PCR identifies Antigen-matched blood units for transfusion-dependent Thai patients. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 44, 358–364 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palacajornsuk, P., Nathalang, O., Tantimavanich, S., Bejrachandra, S. & Reid, M. E. Detection of MNS hybrid molecules in the Thai population using PCR-SSP technique. Transfus. Med.17, 169–174 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thinley, J., Nathalang, O., Chidtrakoon, S. & Intharanut, K. Blood group P1 prediction using multiplex PCR genotyping of A4GALT among Thai blood donors. Transfus. Med.31, 48–54 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Untergasser, A. et al. Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res.35, W71–W74 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaney, M. et al. Red blood cell antigen genotype analysis for 9087 Asian, Asian American, and native American blood donors. Transfusion55, 2369–2375 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashmi, G. et al. Determination of 24 minor red blood cell antigens for more than 2000 blood donors by high-throughput DNA analysis. Transfusion47, 736–747 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyrard, T. Use of genomics for decision-making in transfusion medicine: laboratory practice. VOXS8, 11–15 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rahuel, C. et al. Alteration of the genes for glycophorin A and B in glycophorin-A-deficient individuals. Eur. J. Biochem.177, 605–614 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tate, C. G., Tanner, M. J., Judson, P. A. & Anstee, D. J. Studies on human red-cell membrane glycophorin A and glycophorin B genes in glycophorin-deficient individuals. Biochem. J.263, 993–996 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suwanwootichai, P. et al. Fatal haemolytic transfusion reaction due to anti-Ena and identification of a novel GYPA c.295delG variant in a Thai family. Vox Sang. 117, 1327–1331 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teawtrakul, N. et al. Red blood cell alloimmunization and other transfusion-related complications in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: A multi-center study in Thailand. Transfusion62, 2039–2047 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minelli, C., Thompson, J. R., Abrams, K. R., Thakkinstian, A. & Attia, J. How should we use information about HWE in the meta-analyses of genetic association studies? Int. J. Epidemiol.37, 136–146 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirschhorn, J. N. & Daly, M. J. Genome-wide association studies for common diseases and complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet.6, 95–108 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller, M. RH genetic variation and the impact for typing and personalized transfusion strategies: a narrative review. Ann. Blood. 8, 18 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nathalang, O., Khumsuk, P., Chaibangyang, W. & Intharanut, K. Characterization of GYP(B-A-B) hybrid glycophorins among Thai blood donors with Mia-positive phenotypes. Blood Transfus.22, 198–205 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu, Y. F., Goldstein, D. B., Angrist, M. & Cavalleri, G. Personalized medicine and human genetic diversity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Med.4, a008581 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.