Abstract

This study investigates the effects of varying exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) rates and temperatures on the combustion and emissions characteristics of a compression ignition engine fueled with hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO). Understanding these effects is essential for optimizing renewable fuel applications in compression ignition engines, contributing to cleaner combustion, and supporting sustainable transportation initiatives. The experiments revealed that increasing the EGR rate to 20% not only reduces NOx emissions by approximately 25% but also increases smoke by around 15%, highlighting a trade-off between NOx and particulate matter control. When EGR temperature is increased from 130 to 220 °C, NOx emissions rise by about 10%, accompanied by a 12% increase in smoke emissions, indicating that elevated EGR temperatures can counteract the NOx-reducing benefits of EGR by raising the overall combustion temperature. Additionally, a higher EGR rate shifts particle size distributions, reducing nucleation mode particles by about 30% while increasing accumulation mode particles, with peak concentrations moving toward larger diameters. These findings suggest that precise control of EGR parameters is essential for optimizing emissions performance and ensuring the feasibility of HVO as an alternative fuel in compression ignition engines.

1. Introduction

The wide-scale use of fossil fuels worldwide has led to severe environmental problems. The combustion of fossil fuels produces carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, which are major contributors to climate change. In addition, it reduces air quality, leading to increased haze and acid rain. These environmental issues not only cause widespread damage to ecosystems but also pose significant threats to human health and economic activities. In this case, the demand for alternative fuels especially environmentally friendly fuels have become increasingly urgent, which featured of renewable, low-carbon, and zero-carbon options.1 By reducing reliance on fossil fuels and promoting the development and adoption of these new fuels, environmental pressures can not only be alleviated, but the economy can also be driven toward sustainable development.2

The rise of biofuels is one of the key measures to address global climate change and the challenges of energy sustainability.3 As the negative environmental impacts of fossil fuels become increasingly apparent, the search for clean and renewable alternative fuels has become a major focus of global energy policy. Biofuels are a type of renewable energy produced from biomass materials such as plant oils, animal fats, starches, and cellulose.4,5 They emit relatively low levels of carbon dioxide during combustion and absorb an equivalent amount of carbon dioxide during growth, making them considered carbon-neutral energy sources. Currently, biofuels are widely used in transportation, power generation, and heating. The most common biofuels include ethanol, conventional biodiesel (such as fatty acid methyl ester, FAME),6 and biomethane.7 These fuels can not only directly replace or be blended with existing fossil fuel systems but also offer good combustion efficiency and lower emissions. Moreover, the production of biofuels can achieve efficient resource recycling by utilizing agricultural waste, used oils, and other materials, further enhancing their environmental benefits.8 However, the widespread adoption of biofuels also faces challenges such as sustainability of feedstock supply, energy consumption in the production process, and potential conflicts with food security. Therefore, countries and research institutions worldwide are continually exploring new biofuels and improvement technologies to enhance production efficiency and expand their applications, aiming to gradually increase their share in the global energy mix.9

Diesel engines, known for their efficiency, durability, and powerful output, have become the mainstays in global transportation, industrial, and agricultural sectors. However, traditional diesel engines primarily rely on fossil fuels, leading to significant environmental issues, particularly the emission of large amounts of greenhouse gases and air pollutants like nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter (PM).10 Therefore, how to maintain the high performance of diesel engines while reducing their environmental impact has become one of the key research focuses. In this case, the application of renewable fuels in diesel engines has emerged as an important area of research. Renewable fuels, such as biodiesel, synthetic fuels, and biomethane, are gradually becoming strong alternatives for diesel engine fuels due to their low carbon emissions and clean combustion characteristics.11,12 These fuels can be used in existing diesel engines and, under certain conditions, even demonstrate superior combustion efficiency and emission characteristics. For example, biodiesel, with its higher oxygen content, promotes more complete combustion, thereby reducing emissions of carbon monoxide (CO) and unburned hydrocarbons (HCs).13,14 Meanwhile, to further optimize diesel engine emissions, advanced engine technologies such as exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) systems have been widely implemented. EGR technology works by recirculating a portion of the exhaust gases back into the combustion chamber, lowering combustion temperatures and thereby reducing NOx formation.15 Studies have shown that when EGR technology is combined with renewable fuels, this combination not only effectively reduces NOx emissions but may also improve combustion efficiency, decrease PM formation, and achieve cleaner combustion.16

Among the many renewable fuels, hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) has emerged as a strong candidate to replace traditional diesel due to its superior chemical and physical properties.17 HVO can be used as a diesel fuel, either as a blend with petroleum diesel or as an additive in mixed fuels for compression ignition (CI) engines.18−20 It has a higher heating value of 43–45 MJ/kg, which exceeds that of conventional diesel at 42.60 MJ/kg.21 This higher energy content means that HVO can deliver more power per unit of fuel, potentially enhancing the engine efficiency and performance. As a result, using HVO as a fuel can contribute to an improved fuel economy and reduced overall fuel consumption in diesel engines. The production of HVO involves hydrotreating vegetable oils, which removes common impurities found in traditional biodiesel, such as the high oxygen content in FAME.22,23 This process makes HVO chemically closer to fossil diesel, resulting in superior combustion performance.24 Compared with traditional biodiesel, HVO offers several advantages. First, HVO has higher combustion efficiency, enabling a more complete combustion process, which helps reduce emissions of CO and unburned HC.25 Second, HVO excels in emission control, as its low sulfur and low aromatic content significantly reduce the formation of sulfur oxides and PM.26 Further, HVO primarily consists of a mixture of normal (n)-alkanes and iso-alkanes, without the presence of cycloalkanes and aromatics.27 This composition leads to a higher cetane number, which enhances ignition quality, and a lower tendency to produce soot during combustion. These characteristics make HVO particularly well-suited for use in CI engines, as they contribute to cleaner combustion, reduced particulate emissions, and improved engine efficiency.28 Additionally, HVO has higher oxidative stability, preventing the oxidative degradation that traditional biodiesel often suffers during storage, thus ensuring long-term fuel stability.29 These characteristics allow HVO to be directly used in existing diesel engines without any modifications, and when combined with advanced engine technologies, such as EGR, it can further optimize diesel engine emissions. These advantages make HVO a renewable fuel with broad application prospects, not only helping diesel engines achieve cleaner combustion but also contributing to the green transition of the global energy structure.30

Research on the application of HVO in diesel engines typically focuses on its effects on spray characteristics, combustion behavior, and emission profiles. Khuong et al. investigated the evaporation characteristics of HVO surrogate fuels under high ambient conditions. The results show that HVOs have higher evaporation rates than diesel at various temperatures and pressures due to the lower final boiling points. Higher ambient pressure leads to a shorter droplet lifetime and higher evaporation rate.31 Kim et al. tested 16 kinds of fuel samples by blending them with diesel and HVO, and compared the engine performance with these blended fuels. They found that iso-HVO blended fuels have better power and fuel efficiency than BD blended fuels. It also showed low THC and CO but similar NOx and PM to biodiesel blends.32 According to Hulkkonen’s studies, due to different physical properties of HVO and diesel fuels, fuel spray characteristics differ.33 Generally, incomplete combustion, knocking, and high emissions may occur if fuel droplets are not evaporated in a timely manner.34 The reduction in fuel viscosity improves the spray quality, which may lead to faster droplet evaporation and more complete combustion.35 Hunicz et al. conducted the first in-depth study assessing the potential of HVO with partially premixed combustion. In their test, cetane number is key for efficient low-temperature combustion with high dilution and HVO achieves 43% indicated thermal efficiency with near-Euro VI engine-out emissions.36 In the study of Ogunkoya,37 renewable diesel fuels were tested in compression ignition engines. Lower fuel consumption and combustion pressure are observed for renewable diesel. Meanwhile, lower soot and NOx emissions are obtained for renewable diesel. For a newer combustion system, using HVO has demonstrated that higher proportions of low-pressure EGR combined with lower fuel injection pressures are advantageous at lower loads. At higher loads, advancing the combustion center, increasing injection pressure, and reducing pilot injection quantities can be achieved without exceeding the baseline diesel's noise and NOx levels..38 In addition to comparative tests conducted on traditional engine test benches, some researchers have conducted studies focusing on the performance of the entire vehicle. Three HVO blends, HVO-7, HVO-30, and HVO-100, fossil diesel, and B7 were used in the study of Suarez-Bertoa,39 and the results show that HVO-100 resulted in lower CO2 emissions and vehicle emissions did not show fuel related trends. In another study by Hernández,40 HVO and two advanced biofuels were tested in a Euro 6 vehicle at 24 °C and −7 °C, revealing that engine efficiency was comparable across all fuels, with a slight improvement observed for HVO. The study found that NOx and LNT efficiency was primarily affected by EGR and ambient temperature, while notable differences between fuels were observed in the DOC performance during the engine warm-up period.

EGR technology, as a mature and effective emission control method, is widely used in diesel engines to reduce NOx emissions.41 The EGR system works by recirculating a portion of exhaust gases from the exhaust system back into the intake system, reducing the oxygen concentration and combustion temperature in the combustion chamber, thereby inhibiting NOx formation. This technology plays a crucial role in enhancing diesel engine emission control, especially in meeting increasingly stringent emission regulations. In studies combining diesel engines with EGR technology, different EGR rates and temperatures have significant impacts on the combustion process and emission characteristics.42 While higher EGR rates can more effectively reduce NOx emissions, they may also lead to incomplete combustion, thereby increasing emissions of PM and CO. Additionally, changes in EGR gas temperature can affect the combustion reaction rate and temperature distribution within the combustion chamber, leading to varying impacts on pollutant formation.43 For diesel engines running on HVO fuel, the EGR technology also holds significant potential. Due to the clean combustion characteristics of HVO fuel, combining it with EGR technology may reduce NOx emissions while further optimizing the levels of other pollutants.44 This combination not only helps to meet stricter emission standards but also enhances fuel combustion efficiency and overall thermal efficiency. The focus on the EGR temperature is particularly relevant for HVO due to its unique combustion properties. With a low aromatic content and high cetane number, HVO tends to exhibit different combustion reactions under varying temperature conditions compared with conventional diesel or other biofuels. Adjusting EGR temperature influences critical parameters like ignition delay and premixed combustion, which play a significant role in optimizing clean combustion characteristics.45,46 In addition, since adjustments in EGR rate and temperature can trigger complex combustion chemical reactions, studying their synergistic effects with HVO fuel is crucial for understanding and optimizing diesel engine emission control.47

In recent years, there has been increasing interest in alternative fuels for compression ignition engines to mitigate environmental impacts and enhance engine efficiency. HVO has emerged as a promising renewable fuel due to its superior combustion properties, such as a higher cetane number and lower aromatic content, which contribute to cleaner combustion and reduced emissions. Since the primary feedstocks for HVO production are vegetable oils and waste fats, which are relatively limited in supply, and the production process requires complex catalytic hydrogenation, its production costs are significantly higher than those of conventional diesel fuel. Although HVO has advantages in reducing carbon emissions, its high production costs and high price limit its widespread adoption. Future widespread adoption will depend on improved production efficiency and cost reductions through scaling. In addition, the application of EGR and the temperature of recirculated exhaust gases can significantly influence combustion dynamics and emission profiles in HVO-fueled engines. Despite the recognized potential of HVO, there is limited research exploring the combined effects of EGR and EGR temperature on combustion characteristics and emissions in compression ignition engines. This study aims to investigate the influence of the EGR rate and EGR temperature on the combustion process, thermal efficiency, and emissions when operating a compression ignition engine with HVO fuel. The findings are expected to provide valuable insights and a theoretical foundation for optimizing EGR strategies to maximize the environmental benefits of HVO in compression ignition engines.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Engine and Test Fuel

The experiment was conducted using an AVL four-stroke 0.7 L research single-cylinder engine, equipped with a common rail diesel injection system capable of reaching injection pressures up to 200 MPa. A single-cylinder engine was selected in this study due to its controlled experimental environment, which enables precise adjustments of variables, such as EGR rate and temperature. This setup allows us to investigate the fundamental combustion and emission characteristics of the HVO fuel under well-defined conditions, providing foundational insights that can inform future studies. The diesel fuel injection system includes a Bosch high-pressure pump and an injector nozzle with six holes, each with a diameter of 0.18 mm. The engine is designed with two integrated balance shafts, which play a crucial role in improving the overall performance and durability of the engine by counteracting inherent imbalances during operation. Since the test engine was a research single-cylinder engine, it was not equipped with any aftertreatment system Table 1.

Table 1. Engine Specifications.

| parameters | specification |

|---|---|

| displacement volume [L] | 0.7 |

| bore/stroke [mm/mm] | 93/102 |

| compression ratio | 17.2:1 |

| number of valves | 4 |

| injection system | common rail DI injector |

| type of combustion chamber | ω type |

In this study, a second-generation HVO fuel was examined and produced through a two-stage catalytic hydroprocessing of vegetable oil. The production process involves an initial hydrotreating step, followed by isomerization, which converts the heavy-chain HCs in vegetable oil into lighter HCs within the diesel range. As a result, this fuel is fully paraffinic, with aromatic, sulfur, and oxygen contents falling below detectable limits. The properties of the tested fuel are detailed in Table 2. Due to its paraffinic nature and lower final boiling point, HVO has a lower density compared to traditional diesel, leading to a reduced heating value per unit volume. However, on a mass basis, HVO exhibits a heating value higher than that of conventional diesel, attributed to its higher hydrogen-to-carbon (H/C) ratio. Additionally, HVO’s aromatic content is nearly negligible, at less than 0.1% by weight. The stability of HVO also surpasses that of conventional diesel, making it suitable for long-term storage and use in vehicles or stationary engines without the risk of degradation, even if they remain idle for extended periods.

Table 2. Parameters of Physical and Chemical Properties of HVO for Testing.

| parameters | specification |

|---|---|

| molecular formula | C14H30 |

| density [g/cm3] | 0.78 |

| 10% distillation [°C] | 249 |

| 90% distillation [°C] | 252 |

| theoretical AFR | 14.97 |

| cetane number | 76 |

| latent heat of vaporization [kJ/kg] | 44.1 |

2.2. Test-Cell Layout

In this study, a research-grade single-cylinder engine was employed, designed without an exhaust gas turbocharger for intake pressurization. To simulate supercharging conditions, the intake system utilized an external stand-alone simulated supercharging unit, the AVL 515, which provided adjustable output gas pressure for precise control during experimentation. Air intake flow was measured with high accuracy using a hot-wire mass flow meter, ensuring reliable data on the engine’s air consumption. To maintain a consistent intake air temperature, an inline air heater was integrated into the system, maintaining the intake temperature at 30 ± 1 °C. This level of control over intake conditions was critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible experimental results. The EGR temperature was controlled through an EGR cooler located within the recirculation loop, allowing precise adjustments to achieve the desired gas temperature. The engine’s gaseous emissions were analyzed using the HORIBA 7200DEGR system, while PM was quantified with the Cambustion DMS 500 system, both of which are high-precision instruments providing comprehensive emissions data. Combustion parameters were captured via an AVL GU22C piezoelectric cylinder pressure sensor mounted on the cylinder head, with data acquisition and analysis conducted through AVL Indi-Com software, offering detailed insights into the combustion process. An open rapid prototyping electronic control unit was utilized to enable precise adjustments of key engine parameters, including common rail pressure, injection timing, and the number and quantity of injections. This level of control facilitated the fine-tuning of the engine’s performance, allowing for the optimization of efficiency and emissions in accordance with the specific research objectives. Boundary conditions, such as engine temperature, were stringently regulated using the AVL 577 system, which maintained a coolant temperature at 80 ± 1 °C and an oil temperature at 88 ± 2 °C, ensuring consistent thermal conditions throughout the experimental procedures. Engine speed and load parameters were controlled via an AVL PUMA control system, which ensured a stable and repeatable testing environment. The layout of the engine test stand and associated experimental instruments is illustrated in Figure 1, providing an overview of the experimental setup and ensuring all components were properly integrated and optimized for the study.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the test rig configuration.

2.3. Engine Test Conditions

In the experiments, the engine was operated at the maximum torque speed of 1800 rpm, and three commonly used load conditions were selected, represented by gross indicated mean effective pressure (GIMEP) values of 0.5, 0.9, and 1.2 MPa. In the calculations for the combustion process, indicated power was used instead of brake power due to the limitations in mechanical efficiency of the single-cylinder engine. These limitations are primarily attributed to the difference in driven accessories compared to a four-cylinder engine. Consequently, the total indicated power was utilized to assess the engine load conditions. In the experiments, cylinder pressure data were collected over 200 consecutive engine cycles under each operating condition. The quantities derived from these pressure data were evaluated based on the average values of these cycles. Emissions, including pollutants in the exhaust gases, were measured directly from the raw exhaust, with samples taken as 15s averages once the system reached a stable state. All specific measurements, such as emission concentrations, were correlated with the engine’s indicated power, which represents the power generated internally by the engine, excluding mechanical losses. As mentioned, this is a test study, where the effects of the EGR ratio and EGR temperature on the combustion and emissions in a DI diesel engine with HVO fuel are evaluated.

3. Results and Discussion

To systematically investigate the effects of EGR ratio and EGR temperature on combustion and emission characteristics in a diesel engine with fuel of HVO, this study was included with three primary experimental sections. First, the combined impact of EGR rate and injection pressure on emissions was evaluated to analyze the synergistic effects of these parameters in reducing emissions. Second, the influence of different EGR temperatures on the combustion process was analyzed. Lastly, the study examined the impact of EGR temperature on particle size distribution, exploring how temperature variations affect the formation and emission characteristics of particulates. All experiments were conducted under comparable engine operating conditions with HVO fuel, ensuring the independence of parameter variations and the comparability of results.

3.1. Impact of EGR Rate and Injection Pressure on Emissions

The introduction of EGR reduces the oxygen concentration in the intake air, decreasing the likelihood of fuel molecules interacting with oxygen atoms during combustion. To counteract this effect, increasing the injection pressure enhances the mixing of fuel and intake air, compensating for the decrease in oxygen concentration. By adjustment of the injection pressure, this study examines the synergistic effects of injection pressure and EGR rate on combustion characteristics and emissions. To further investigate the mechanism by which EGR affects the combustion process, the experiment precisely adjusted the injection timing to stabilize the combustion phase (CA50) at approximately 8 °CA after the top dead center. This ensured that the combustion process exhibited good repeatability and comparability. Figure 2 indicates the comparative effects of EGR rates on the combustion process under different injection pressures. As observed from these figures, under lower load, the relatively high proportion of premixed combustion allows for a significant increase of the EGR ratio, while maintaining a constant combustion phase. The reduction in oxygen concentration with a higher EGR ratio suppresses the combustion reaction rate, thereby decreasing the peak heat release rate and resulting in a more controlled combustion process. However, under a higher load, the increase in fuel injection quantity makes the duration of the ignition delay period critically important. By increasing the EGR rate, the ignition delay period is extended, providing more time for the premixing of fuel and air, thereby increasing the amount of premixed combustion. The enhancement of premixed combustion improves combustion efficiency and also helps reduce NOx emissions under certain load conditions. Further analysis of combustion characteristics under different injection pressures reveals that, under a lower load, the impact of EGR on the peak heat release rate is relatively limited even with increased injection pressure. However, as the load increases, a high injection pressure significantly enhances the kinetic energy of the fuel spray, improving the mixing of fuel and air, thereby substantially increasing the amount of premixed combustion. In this case, by reducing the intake oxygen concentration, it is possible to effectively suppress the excessive increase in the combustion rate while increasing the amount of premixed combustion, thereby preventing an excessive rate of pressure rise during the combustion process. Therefore, under the condition of a fixed combustion phase, the synergistic control of high injection pressure and low intake oxygen concentration, which provided by a higher EGR ratio, can achieve a highly premixed combustion process, while effectively preventing excessive pressure rise rates caused by overly rapid combustion reactions.

Figure 2.

Comparison of EGR on heat release rate with different injection pressure under various load conditions.

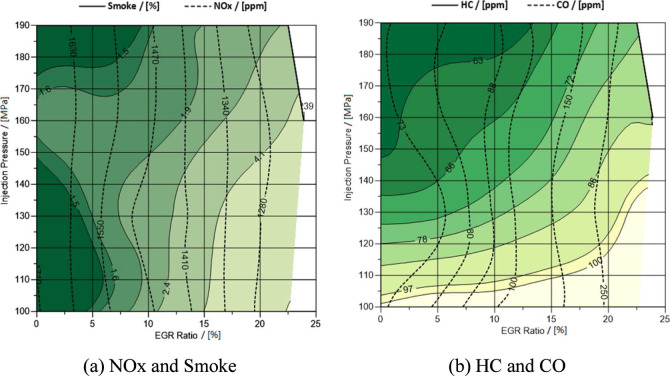

Figure 3 illustrates contour plots of the emission characteristics of a compression ignition engine fueled with HVO, showing variations with the EGR ratios and fuel injection pressure. In these figures, the x axis represents the EGR ratio and the y axis represents the fuel injection pressure. In Figure 3a, the contour lines represent smoke opacity and NOx emissions, with solid lines indicating smoke and dashed lines indicating NOx emissions. It can be observed from the figure that as the EGR ratio increases, NOx emissions show a significant reduce trend, while smoke opacity increases to some extent. This phenomenon occurs because EGR introduces part of the exhaust gas back into the cylinder, lowering the combustion temperature and thereby reducing NOx formation. Under EGR conditions, the presence of inert gases such as CO2 and H2O reduces oxygen availability, which affects combustion reactions and helps lower peak temperatures, thereby reducing NOx formation. However, the lower combustion temperature also leads to an increase in incomplete combustion, which in turn raises smoke. When the EGR ratio is low (<10%), even with an injection pressure increase to 190 MPa, NOx emissions remain at a high level (>1600 ppm), while smoke stays within a lower range. This indicates that under low EGR ratios, although higher fuel injection pressure helps enhance fuel atomization quality, the combustion temperature remains high, resulting in significant NOx formation. However, when the EGR ratio increases to above 15%, NOx emissions significantly drop below 1400 ppm, particularly under the combination of high EGR ratio and high injection pressure. This indicates that effective EGR introduction can significantly suppress NOx emissions. However, the increase in smoke also becomes notable at this point, especially under lower injection pressures. This suggests that under high EGR rates, although NOx emissions are significantly reduced, excessive EGR can lead to incomplete combustion, thereby increasing smoke. Further analysis suggests that appropriate adjustment of the EGR ratio can achieve an optimal balance between NOx emissions and smoke. Under moderate EGR ratio (10–15%) and high injection pressures (>170 MPa), NOx emissions can be significantly reduced while keeping smoke at a relatively low level.

Figure 3.

Contour plots of the emission characteristics.

Figure 3b shows contour plots of HC and CO emissions as functions of EGR ratios and fuel injection pressures, with solid lines representing HC emissions and dashed lines representing CO emissions. In conjunction with the analysis of Figure 4a, it can be observed from Figure 4b that as the EGR ratio increases, both HC and CO emissions show an increasing trend, consistent with the increase in smoke seen in Figure 4a. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the decrease in combustion temperature due to increased EGR, leading to incomplete combustion and the formation of more partially oxidized products. When the EGR ratio is <10%, HC emissions are relatively low, and CO emissions remain at a low level. However, as the EGR ratio further increases, especially above 15%, HC emissions significantly rise, exceeding 100 ppm, and CO emissions also increase significantly too. This indicates that under high EGR ratios, incomplete combustion becomes more pronounced, leading to increased HC and CO formation. Figure 3b also shows the impact of the injection pressure on HC and CO emissions. Overall, as injection pressure increases, both HC and CO emissions decrease, with this reduction trend being more pronounced when the EGR ratio is between 10 and 15%. For example, when the injection pressure exceeds 160 MPa, even as the EGR ratio increases above 15%, HC and CO emissions remain relatively low. This suggests that high injection pressure helps improve fuel atomization and combustion efficiency, thereby mitigating the incomplete combustion caused by increased EGR.

Figure 4.

Comparison of heat release rate with different EGR temperature under various loads.

3.2. Effect of EGR Temperature on the Combustion Process and Emissions

In the process of achieving premixed combustion in compression ignition engines, EGR is widely regarded as one of the key methods for controlling combustion characteristics. The introduction of EGR not only increases the inert components in the intake air, such as carbon dioxide and water vapor, but also raises the heat capacity of the intake, effectively suppressing the peak combustion temperature in the cylinder and reducing NOx formation. However, during actual engine operation, the significant amount of heat carried by the EGR can notably affect the intake air temperature, which in turn influences the intake air density and the engine’s volumetric efficiency. This impact not only is due to changes in the intake air quantity but also alters the thermodynamic state and chemical activation environment within the cylinder, leading to complex interactions that affect the combustion process and emission characteristics. Therefore, an in-depth study of combustion and emission behaviors under different EGR temperature conditions is crucial for optimizing the overall engine performance. This section systematically adjusts the temperature of the recirculated exhaust gas to explore its effects on intake conditions and in-cylinder thermodynamic states, aiming to reveal the combustion characteristics and emission patterns of the engine under different EGR temperatures.

Figure 4 illustrates the effect of the EGR temperature on the heat release rate during the combustion process of a compression ignition engine under different loads. Specifically, Figure 4a represents the case where GIMEP is 0.5 MPa, Figure 4b corresponds to a GIMEP of 0.9 MPa, and Figure 4c shows the heat release rate curve at a GIMEP of 1.2 MPa. In each figure, the variation in the heat release rate with crank angle reveals the significant effect of increasing EGR temperature on the combustion process. As seen in Figure 4a, under low-load conditions, the peak heat release rate slightly decreases as the EGR temperature increases. This indicates that under low-load conditions, higher EGR temperatures increase the heat capacity within the cylinder, delaying the rapid heat release phase of combustion, reducing the peak combustion temperature, and consequently lowering the peak heat release rate. Additionally, high EGR temperatures may slow the combustion rate of the premixed gases, leading to a smoother combustion process. Figure 4b shows that under medium-load conditions, the peak heat release rate is more significantly affected by the EGR temperature. As the EGR temperature increases from 120 to 190 °C, the peak heat release rate significantly decreases, and the heat release process is slightly advanced. This phenomenon further confirms the suppressive effect of EGR temperature on the combustion rate; as the EGR temperature increases, the in-cylinder temperature rises, resulting in a shorter ignition delay period. Consequently, the amount of premixed combustion decreases, leading to a lower peak heat release rate. This effect highlights the role of EGR temperature in controlling combustion characteristics by influencing ignition delay and the extent of premixed combustion. Figure 4c demonstrates that under high-load conditions, the impact of EGR temperature on the heat release rate is most pronounced. When the EGR temperature rises from 130 to 220 °C, the heat release rate curve exhibits significant fluctuations, with a further reduction in the peak value. This may be due to complex changes in the thermodynamic state within the combustion chamber under high-load and high-temperature EGR conditions, leading to increased local instabilities in the combustion process, which effect the overall heat release characteristics. The above results indicate that EGR temperature has a significant impact on the combustion process of a compression ignition engine under different load conditions. As the load increases, the suppressive effect of EGR temperature on the heat release rate becomes more pronounced, and high-temperature EGR may induce combustion instability under high-load conditions.

Figure 5 illustrates the NOx and smoke emission characteristics of the engine under different EGR temperatures and GIMEP conditions. In this figure, solid contour lines represent NOx emissions, while dashed contour lines represent smoke emissions. It can be observed from the figure that as EGR temperature increases, NOx emissions show an increase trend. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that higher EGR temperatures increase the intake air temperature, leading to an overall increase in the combustion chamber temperature, thereby promoting NOx formation. This trend is particularly pronounced under high-load conditions, indicating that the EGR temperature has a more significant impact on NOx emissions during high-load operation. Simultaneously, smoke emissions also increase with rising EGR temperatures. The introduction of high-temperature EGR increases the intake air temperature, which may lead to an increase in locally over-rich fuel–air mixtures during combustion, resulting in incomplete combustion and the formation of more soot particles. Additionally, higher intake temperatures may shorten the burn duration, slowing the oxidation reactions, and further increase the smoke emissions. Overall, increasing the EGR temperature leads to higher emissions of both NOx and smoke, which contrasts with the traditional understanding that EGR reduces NOx emissions. This is primarily because the rise in the intake air temperature due to elevated EGR temperatures counteracts the suppressive effect of EGR on the combustion temperature.

Figure 5.

Comparison of smoke and NOx emission with various EGR temperatures and loads.

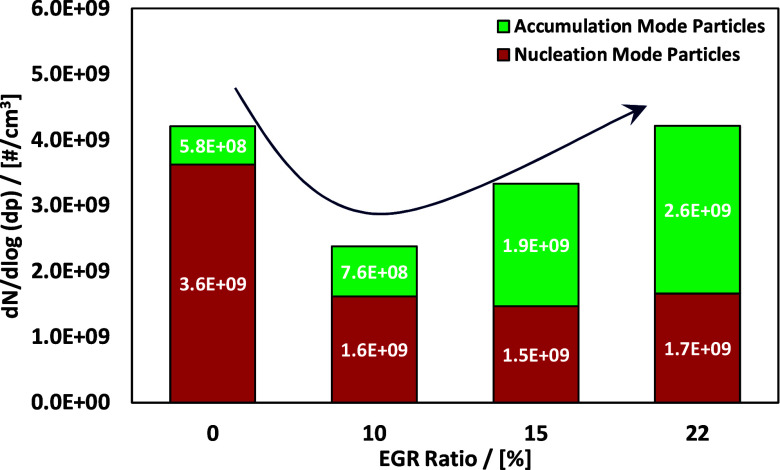

3.3. Effects on Particle Size Distributions

Figure 6 illustrates the effect of the EGR rate on the particle size distribution characteristics of particulate emissions under different load conditions. In this study, nucleation mode particles refer to particles with diameters smaller than 50 nm, while accumulation mode particles are defined as those with diameters ranging from 50 to 1000 nm. This figure shows that as the EGR ratio increases, the number peak concentration of nucleation mode particles significantly decreases, while the number peak concentration of accumulation mode particles increases. Additionally, the number peak concentrations of various modes shift toward larger particle sizes. Under high-load conditions, the particle size distribution curve of particulate emissions exhibits a distinct bimodal distribution, and the effect of EGR rate on the particle size distribution characteristics becomes more pronounced. This occurs because the introduction of EGR reduces the amount of fresh air entering the cylinder, which increases the air–fuel ratio and creates large oxygen-deficient zones. In these zones, some fuel cannot fully contact oxygen during combustion, leading to pyrolysis, cyclization, and dehydrogenation under high temperatures, eventually forming loosely structured, porous carbonaceous particles. Because porous carbonaceous particles have a large specific surface area, they readily adsorb unburned HCs in the cylinder, leading to the growth and aggregation of these particles into larger accumulation mode particulates, thereby increasing their number concentration. It is generally believed that nucleation mode particles primarily form during exhaust cooling and dilution, consisting mainly of soluble organic fractions and some small carbonaceous cores. With the introduction of EGR, the increased number of accumulation mode particles enhances the adsorption of unburned HCs, thereby suppressing the formation of nucleation mode particles. Under low-load conditions, even with a high EGR rate, the overall air–fuel ratio in the cylinder remains relatively large, suppressing particulate formation.

Figure 6.

Particle size distribution characteristics under various EGR ratios.

As observed from Figure 7, the number of nucleation mode particles and accumulation mode particles changes significantly with increasing EGR rates. At an EGR rate of 0, nucleation mode particles dominate, with a concentration of 3.6 × 109 #/cm3, while accumulation mode particles have a relatively lower concentration of 5.8 × 108 #/cm3. This indicates that under conditions without EGR, the engine emissions are primarily composed of smaller nucleation mode particles. When the EGR rate increases to 10%, the number of nucleation mode particles significantly decreases while the concentration of accumulation mode particles increases. At this point, the introduction of EGR reduces the formation of smaller particles and increases the concentration of larger accumulation mode particles. This is because EGR increases the residual components in the combustion chamber, lowering the combustion temperature and thereby reducing the formation of some accumulation mode particles. When the EGR rate reaches 22%, the concentration of nucleation mode particles rises to 1.7 × 109 #/cm3, while accumulation mode particles increase significantly. This trend is attributed to the significant reduction in the intake oxygen concentration at high EGR rates, leading to a notable increase in accumulation mode particles and enhanced agglomeration growth of smaller nucleation mode particles.

Figure 7.

Effect of EGR rate on particle emission characteristics.

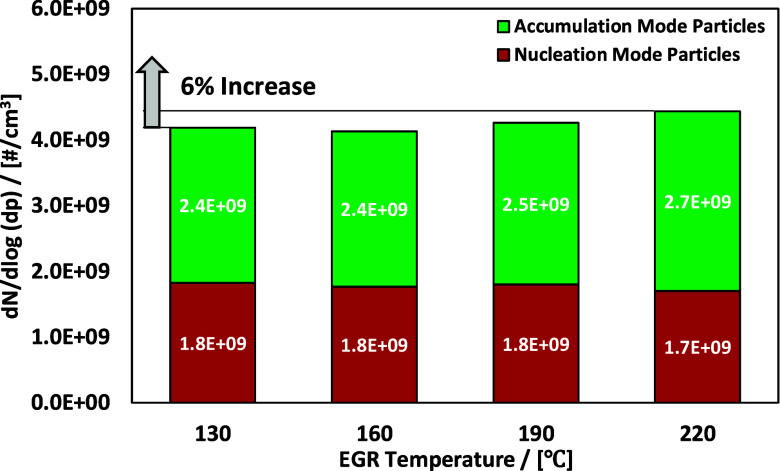

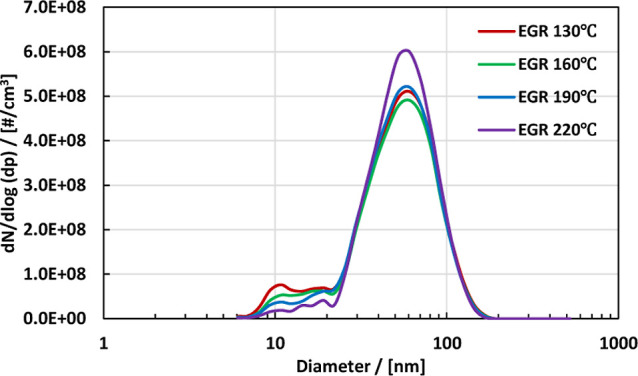

Under different EGR temperatures, as Figure 8 indicates, the particle size distribution curves remain largely unchanged, consistently showing a “bimodal” distribution. The peak range for nucleation mode particles is 10–20 nm, while the peak for accumulation mode particles is between 60 and 70 nm. As the EGR temperature increases, the number concentrations of particles in each mode increase. For particles with diameters smaller than 22 nm, their total number concentration shows a monotonically decreasing trend. This is primarily because, as the EGR temperature rises, the intake air temperature correspondingly increases, reducing the intake charge and increasing the air–fuel ratio. This leads to more high-temperature oxygen-deficient regions in the cylinder, where fuel is prone to pyrolysis during the diffusion combustion phase, forming a large number of carbonaceous particles and thereby increasing the number concentrations of particles in each mode.

Figure 8.

Comparison of particle size distribution of particles under different EGR temperature.

Figure 9 shows the changes in the concentrations of the nucleation mode particles and accumulation mode particles in the exhaust of a compression ignition engine under different EGR temperatures. As observed from this figure, the overall concentrations of nucleation mode particles and accumulation mode particles slightly increase with rising EGR temperatures. Specifically, when the EGR temperature increases from 130 to 220 °C, the concentration of accumulation mode particles rises from 2.4 × 109 #/cm3 to 2.7 × 109 #/cm3, an increase of approximately 6%. In contrast, the concentration of nucleation mode particles shows minimal change, remaining around 1.8 × 109 #/cm3. This indicates that under high-temperature EGR conditions, while the formation of nucleation mode particles is suppressed, the concentration of accumulation mode particles significantly increases with rising temperatures. This may be because high-temperature EGR introduces more inert components, such as water vapor and carbon dioxide, altering the chemical environment in the combustion chamber, which promotes the aggregation and growth of small particles, thereby increasing the formation of accumulation mode particles. Additionally, high-temperature EGR may affect the coagulation rate of particles, further increasing the concentration of the larger particles.

Figure 9.

Effect of EGR temperature on particle emission characteristics.

4. Conclusions

This study examined the effects of varying EGR rates and temperatures on the combustion and emission characteristics of a compression ignition engine fueled with HVO. Using a controlled experimental setup, we evaluated how EGR parameters influence combustion dynamics and emissions. The findings provide valuable insights for optimizing EGR settings with HVO fuel, offering guidance for engine manufacturers in designing or retrofitting engines to enhance combustion efficiency and emissions performance. By appropriately adjusting EGR rates and temperatures, HVO’s viability as an alternative fuel can be strengthened, aligning with stricter emissions standards and supporting sustainable transportation goals. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

(1)

Increasing the EGR rate up to 20% can effectively reduce NOx emissions by approximately 25%. However, this also results in a concurrent increase in smoke by around 15%, especially under higher-load conditions, indicating a trade-off between NOx reduction and particulate emissions.

-

(2)

Raising the EGR temperature from 130 to 220 °C increases NOx emissions by about 10%, while smoke emissions rise by approximately 12%. This suggests that higher EGR temperatures, while beneficial for certain aspects of combustion, can elevate overall combustion temperatures, thereby diminishing the NOx reduction benefits typically associated with EGR.

-

(3)

A higher EGR rate shifts particle size distributions, significantly reducing the concentration of nucleation mode particles but increasing the accumulation mode particles by a similar magnitude. This shift indicates that EGR not only affects gaseous emissions but also alters the physical characteristics of PM.

-

(4)

The combination of a higher EGR rate and increased fuel injection pressure enhances premixed combustion, resulting in better combustion efficiency and lower NOx emissions under controlled combustion phases. However, excessive EGR rates can lead to increased HC and CO emissions due to incomplete combustion, highlighting the need for precise control of these parameters to achieve optimal emission reductions.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Provincial quality project of Anhui Provincial Department of Education (project nos. 2023sdxx189, 2023AH051156, and gxgnfx2022129).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CI

compression ignition

- CO

carbon monoxide

- EGR

exhaust gas recirculation

- FAME

fatty acid methyl ester

- GIMEP

gross indicated mean effective pressure

- HC

hydrocarbon

- HVO

hydrotreated vegetable oil

- NOx

nitrogen oxides

- PM

particulate matter

Author Contributions

J.L. and X.S. contributed equally to this work. J.L.: Data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, and writing–review and editing. Z.H.: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, and project administration. B.T.: Conceptualization, supervision, validation, and writing–review and editing. X.S.: Data curation, writing–review and editing, and supervision. J.P.: Data curation and writing–review and editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Di Blasio G.; Ianniello R.; Beatrice C. Hydrotreated vegetable oil as enabler for high efficient and ultra-low emission vehicles in the view of 2030 targets. Fuel 2022, 310 (Feb.15 Pt.B), 122206. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai P.; Zhang C.; Jing Z.; Peng Y.; Jing J.; Sun H. Effects of Fischer–Tropsch diesel blending in petrochemical diesel on combustion and emissions of a common-rail diesel engine. Fuel 2021, 305 (Dec.1), 121587. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha D.; De Souza T.; Coronado C.; et al. Exergo environmental analysis of hydrogen production through glycerol steam reforming. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46 (1), 1385–1402. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prussi M.; Weindorf W.; Buffi M.; et al. Are algae ready to take off? GHG emission savings of algae-to-kerosene production. Appl. Energy 2021, 304 (C), 117817. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117817. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A.; Thangaraj R.; Mehta P. Farm-to-fire analysis of karanja biodiesel. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefin. 2021, 15 (6), 1737–1752. 10.1002/bbb.2271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Labecki L.; Ganippa L. Effects of injection parameters and EGR on combustion and emission characteristics of rapeseed oil and its blends in diesel engines. Fuel 2012, 98, 15–28. 10.1016/j.fuel.2012.03.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan B.; Kumar N.; Cho H. Performance and emission studies on an agriculture engine on neat Jatropha oil. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2010, 24 (2), 529–535. 10.1007/s12206-010-0101-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerpen J. V. Biodiesel processing and production. Fuel Process. Technol. 2005, 86 (10), 1097–1107. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2004.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douvartzides S.; Charisiou N.; Papageridis K.; Goula M. A. Green diesel: Biomass feedstocks, production technologies, catalytic research, fuel properties and performance in compression ignition internal combustion engines. Energies 2019, 12 (5), 809–841. 10.3390/en12050809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Wang Y.; Somers L.; van de Beld B. Ignition and combustion characteristics of hydrotreated pyrolysis oil in a combustion research unit. Fuel 2022, 316 (May 15), 123419. 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.123419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karavalakis G.; Johson K.; Hajbabaei M.; et al. Application of low-level biodiesel blends on heavy-duty (diesel) engines: feedstock implications on NOx and particulate emissions. Fuel 2016, 181, 259–268. 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.05.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Na K.; Biswas S.; Robertson W.; et al. Impact of biodiesel and renewable diesel on emissions of regulated pollutants and greenhouse gases on a 2000 heavy duty diesel truck. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 107, 307–314. 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.02.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha H.; Pereira R.; Nogueira M.; et al. Experimental investigation of hydrogen addition in the intake air of compressed ignition engines running on biodiesel blend. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42 (7), 4530–4539. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karagöz Y.; Güler I.; Sandalci T.; et al. Effect of hydrogen enrichment on combustion characteristics, emissions and performance of a diesel engine. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41 (1), 656–665. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.09.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omari A.; Pischinger S.; Bhardwaj O.; Holderbaum B.; Nuottimäki J.; Honkanen M. Improving engine efficiency and emission reduction potential of HVO by fuelspecific engine calibration in modern passenger car diesel applications. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2017, 10 (3), 756–767. 10.4271/2017-01-2295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri N.; Khatri K. Hydrogen enrichment on diesel engine with biogas in dual fuel mode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45 (11), 7128–7140. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.12.167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasio G.; Ianniello R.; Beatrice C. Hydrotreated vegetable oil as enabler for high-efficient and ultra-low emission vehicles in the view of 2030 targets. Fuel 2022, 3310, 122206. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.122206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtonen T.; Aakko-Saksa P.; Kuronen M.; Mikkonen S.; Lehtoranta K. Emissions with heavy-duty diesel engines and vehicles using FAME, HVO and GTL fuels with and without DOC + POC aftertreatment. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2009, 2, 147–166. 10.4271/2009-01-2693. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen L.; Linnalia R.; Aakko P.; et al. NExBTL-biodiesel fuel of the second generation; SAE, 2005, No. 2005–01–3771.

- Pflaum H.; Hofmann P.; Geringer B.; Weissel W.. Potential of hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) in a modern diesel engine; SAE, 2010, No. 2010–32–0081.

- Hunicz J.; Mikulski M.; Shukla P.; et al. Partially premixed combustion of hydrotreated vegetable oil in a diesel engine: Sensitivity to boost and exhaust gas recirculation. Fuel 2022, 307 (6), 121910. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulec J.; Cvengros J.; Jorikova L.; et al. Second generation diesel fuel from renewable sources. J. Cleaner Prod. 2010, 18 (9), 917–926. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapuerta M.; Villajos M.; Agudelo J.; et al. Key properties and blending strategies of hydrotreated vegetable oil as biofuel for diesel engines. Fuel Energy Abstr. 2011, 92 (12), 2406–2411. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2011.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krar M.; Kasza T.; Kovacs S.; et al. Bio gas oils with improved low temperature properties. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011, 92 (5), 886–892. 10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murtonen T.; Aakko-Saksa P.; Kuronen M.; et al. Emissions with heavy-duty diesel engines and vehicles using FAME, HVO and GTL fuels with and without DOC + POC aftertreatment; SAE, 2009, No. 2009–01–2693.

- Knothe G. Biodiesel and renewable diesel: a comparison. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36 (3), 364–373. 10.1016/j.pecs.2009.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama K.; Isamu G.; Koji K.; et al. Effects of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) as Renewable Diesel Fuel on Combustion and Exhaust Emissions in Diesel Engine. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2012, 5 (1), 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Pelemo J.; Inambao F.; Onuh E. Potential of used cooking oil as feedstock for hydroprocessing into hydrogenation derived renewable diesel: a review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Sci. Technol. 2020, 13, 500–519. 10.37624/IJERT/13.3.2020.500-519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekman S.; Broch A.; Robbins C.; et al. Review of biodiesel composition, properties, and specifications. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2012, 16 (1), 143–169. 10.1016/j.rser.2011.07.143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ushakov S.; Lefebvre N. Assessment of Hydrotreated Vegetable Oil (HVO) Applicability as an Alternative Marine Fuel Based on Its Performance and Emissions Characteristics. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2019, 12 (2), 109. 10.4271/04-12-02-0007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khuong L. S.; Hashimoto N.; Konno Y.; Suganuma Y.; Nomura H.; Fujita O. Droplet evaporation characteristics of hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) under high temperature and pressure conditions. Fuel 2024, 368, 131604. 10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Kim S.; Oh S.; No S. Y. Engine performance and emission characteristics of hydrotreated vegetable oil in light duty diesel engines. Fuel 2014, 125 (jun.1), 36–43. 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.01.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hulkkonen T.; Hillamo H.; Sarjovaara T.; et al. Experimental study of spray characteristics between hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) and crude oil based EN 590 diesel fuel; SAE, 2011.

- Al Qubeissi M.; Sazhin S.; Al-Esawi N.; et al. Correction to Heating and Evaporation of Droplets of Multicomponent and Blended Fuels: A Review of Recent Modeling Approaches. Energy Fuels 2022, 36 (3), 1746. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c02316. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sallevelt J.; Gudde J.; Pozarlik A.; Brem G. The impact of spray quality on the combustion of a viscous biofuel in a micro gas turbine. Appl. Energy 2014, 132 (nov.1), 575–585. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.07.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunicz J.; Matijošius J.; Rimkus A.; et al. Efficient hydrotreated vegetable oil combustion under partially premixed conditions with heavy exhaust gas recirculation. Fuel 2020, 268, 117350. 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunkoya D.; Roberts W.; Fang T.; et al. Investigation of the effects of renewable diesel fuels on engine performance, combustion, and emissions. Fuel 2015, 140, 541–554. 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.09.061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omari A.; Stefan P.; Parkash B.; et al. Improving Engine Efficiency and Emission Reduction Potential of HVO by Fuel-Specific Engine Calibration in Modern Passenger Car Diesel Applications. SAE Int. J. Fuels Lubr. 2017, 10 (3), 756. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Bertoa R.; Kousoulidou M.; Clairotte M.; et al. Impact of HVO blends on modern diesel passenger cars emissions during real world operation. Fuel 2019, 235, 1427–1435. 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.08.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández J.; Rodríguez-Fernández J.; Calle-Asensio A. Performance and regulated gaseous emissions of a Euro 6 diesel vehicle with Lean NOx Trap at different ambient conditions: Sensitivity to the type of fuel. Energy Convers. Manage. 2020, 219, 113023. 10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaraja J.; Kannan C. Effect of exhaust gas recirculation on advanced diesel combustion and alternate fuels-A review. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 169–184. 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.07.096. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rakopoulos C.; Rakopoulos D.; Mavropoulos G.; et al. Investigating the EGR rate and temperature impact on diesel engine combustion and emissions under various injection timings and loads by comprehensive two-zone modeling. Energy 2018, 157, 990–1014. 10.1016/j.energy.2018.05.178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zu X.; Yang C.; Wang H.; Wang Y. An EGR performance evaluation and decision-making approach based on grey theory and grey entropy analysis. PLoS One 2018, 13 (1), e01916266 10.1371/journal.pone.0191626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeika G.; Matijošius J.; Rimkus A. Research of the impact of EGR rate on energy and environmental parameters of compression ignition internal combustion engine fuelled by hydrogenated vegetable oil (HVO) and biobutanol – Castor oil fuel mixtures. Energy Convers. Manage. 2022, 270, 116198. 10.1016/j.enconman.2022.116198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Velmurugan A.; Rajamurugan T. V.; Rajaganapathy C.; et al. Enhancing performance, reducing emissions, and optimizing combustion in compression ignition engines through hydrogen, nitrogen, and EGR addition: An experimental study. J. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1360–1375. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.09.115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Apparao C. M. S.; Sharma T. K.; Rao G. A. P. Attaining improved control over the start of combustion in dual-fuel HCCI engine through the influence of EGR. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 13993–14004. 10.1007/s10973-024-13690-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hunicz J.; Mikulski M.; Shukla C.; et al. Partially premixed combustion of hydrotreated vegetable oil in a diesel engine: Sensitivity to boost and exhaust gas recirculation. Fuel 2022, 307 (6), 121910. 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.121910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]