Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate health literacy in orthopedic shoulder and elbow patients.

Methods

This retrospective cross-sectional study included all new English-speaking adult patients presenting to two fellowship-trained shoulder and elbow surgeons from October 2020–July 2021. Patients who did not complete the Brief Health Literacy Screen Tool (BRIEF) were excluded, leaving 594 patients. Patient demographics and patient-reported outcome scores were also collected.

Results

Average BRIEF score was 18.7 (range, 4–20), with limited health literacy (BRIEF <17) in 84 patients (14.1%). Patients with limited health literacy were significantly older (58 ± 18 vs. 54 ± 15 years, p = 0.03), less likely to be employed (34 [40%] vs. 332 [65%], p < 0.001), and less likely to have private insurance (35 [42%] vs. 330 [65%], p < 0.001). Average area deprivation index percentile was significantly higher (more deprivation) with limited (38 ± 20) compared to adequate health literacy (32 ± 21; p = 0.027). PROMIS physical (40.5 ± 8.5 vs. 45.5 ± 7.6, p = 0.001) and mental health scores (46.9 ± 10.5 vs. 51.0 ± 8.6, p = 0.015) and pain visual analog scale scores (5.3 ± 2.9 vs. 4.6 ± 2.7, p = 0.017) were significantly worse with limited health literacy.

Discussion

Limited health literacy is present in shoulder and elbow patients and may affect patient-reported outcomes. Surgeons must recognize this in order to provide high-level equitable care.

Level of evidence

Level III, retrospective cohort.

Keywords: shoulder, elbow, health literacy, patient-reported outcomes, disparities

Introduction

Limited health literacy, defined as a relatively low capacity to gain access to, understand and use health and medical information, 1 represents a challenge for providing effective patient-centered care. Approximately 33–68% of patients in the United States have limited health literacy,2–4 which impacts patients’ ability to make informed health and medical decisions and has been associated with poor outcomes, high healthcare costs and high mortality across medical disciplines.4–6 Patients with limited health literacy have also been reported to have higher utilization of emergency medical services, lower use of preventative services and more avoidable hospital admissions compared to those with adequate health literacy,5–8 all of which contribute to the high healthcare costs that have been associated with limited health literacy.2–4

The implications of limited health literacy are especially important in orthopedic surgery because musculoskeletal complaints account for 18% of healthcare visits in the United States and affect nearly 75% of those over the age of 65.9,10 Limited health literacy can be a serious obstacle to the effective physician–patient communication necessary for discussions of diagnosis and treatment. Limited health literacy may also impact certain patient-reported outcome scores in specific orthopedic populations both preoperatively and postoperatively,11–13 which has implications for surgeon's understanding and utilization of these assessment tools. Risk factors for limited health literacy in orthopedic patients may include race, education, age, and employment status, although that may vary depending on the clinical setting, specific patient population, and assessment tool.14,15

Shoulder pain is the second most common musculoskeletal complaint after low back pain and occurs in up to 50% of the U.S. adult population annually. 16 There are few studies on health literacy in patients with shoulder and elbow complaints and the potential impact of limited health literacy on patient-reported outcomes in this population. This study aimed to determine the incidence of limited health literacy in a population of orthopedic shoulder and elbow patients, the demographic factors associated with limited health literacy in this population, and how limited health literacy impacts patient-reported outcome measures.

Materials and methods

Institutional IRB approval was obtained for this retrospective cross-sectional study. All new patients presenting to one of two fellowship-trained shoulder and elbow surgeons at a large tertiary referral hospital system from October 2020 to July 2021 were eligible for inclusion. The clinical sites included are located in urban and suburban locations and have a large catchment area that also includes rural areas across multiple counties and states.

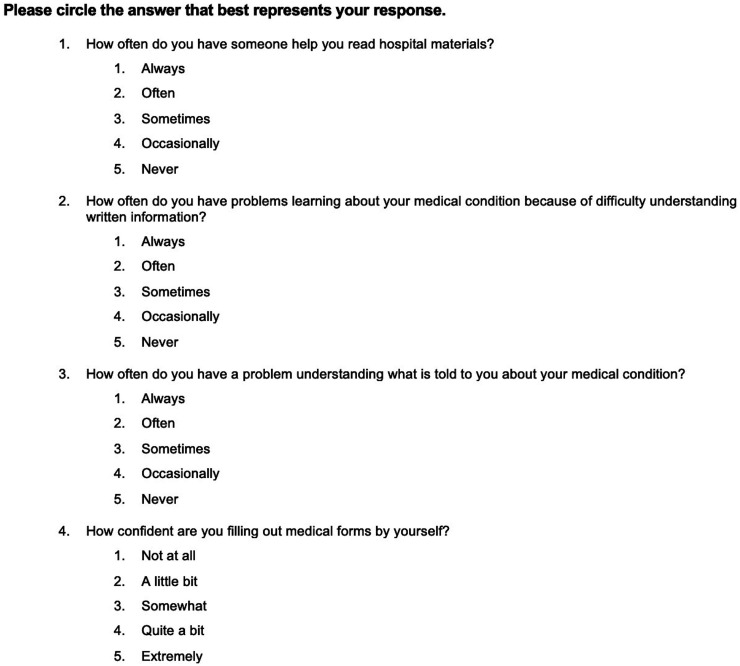

As part of standard clinical practice, all patients complete a patient-reported outcomes assessment at their initial visit. Assessments can be completed online before the appointment or at the office either electronically on an iPad or using pencil and paper. Administered assessments include the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) score, Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Physical and Mental Health scores, a pain visual analog scale (VAS) and the Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool (BRIEF). ASES, PROMIS Physical and Mental and pain VAS are three validated patient-reported outcome measurements. ASES is a functional assessment specific to the shoulder. PROMIS physical and mental health assess well-being more broadly. The BRIEF is a four-question metric to quantify a patient's level of health literacy (Figure 1).2,17 It has been validated against other health literacy metrics in a variety of patient populations as a screening tool for limited health literacy.18,19 Scores range from 2 to 20, with score of 17 or greater indicating adequate health literacy, 13–16 indicating marginal health literacy and 4–12 indicating inadequate health literacy.2,17 For study purposes, all patients with BRIEF score of less than 17 were considered to have limited health literacy. Patients who did not complete the BRIEF during their initial assessment were excluded from the study. Of 643 patients who completed new patient paperwork during the study period, 49 (7.6%) did not complete the BRIEF and were excluded, leaving a total of 594 patients in the study.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of BRIEF score of less than 17 was calculated for the sample population to determine the prevalence of limited health literacy. Mean and range of BRIEF scores were also determined.

Patient demographics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, employment status, type of insurance and residential address were collected from the electronic medical record for all included patients. The area deprivation index (ADI) for each patient was determined based on the 9-digit zip code of their address. The ADI is a validated zip code-based metric of neighborhood-level socioeconomic disadvantage 20 that takes into account 17 different census metrics such as income, education level and crime statistics for a geographic area. The metric has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality across medical disciplines. 21 ADI is reported as a percentile from 1 to 100, with a lower percentile indicating less disadvantage. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize population demographics, and univariate statistical analyses were used to compare demographic variables between those with and without adequate health literacy. Descriptive statistics were also used to compare the ASES, PROMIS Physical and Mental Health and pain VAS for those with adequate versus limited health literacy. Univariate statistical analyses were used to compare these patient-reported outcome variables between those with and without adequate health literacy.

For all analyses, a p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel Data Analysis Pack 2019.

Results

Study data are available upon request.

Prevalence of limited health literacy

The average age was 55 years (range, 12–92). Of the 594 patients, 298 were female (50.2%), 427 were White (71.9%) and 121 were Black (20.4%). The average BRIEF score was 18.7 (range, 4–20), with 84 patients (14.1%) identified as having limited health literacy (score < 17).

Demographic factors associated with limited health literacy

Patients with limited literacy were significantly older (58 ± 18 years) than those with adequate health literacy (54 ± 15; Table 1). There was no significant difference in race/ethnicity or gender between the groups. Those with limited health literacy were less likely to be employed (34 [40.5%] vs. 332[65.1%]) and less likely to have private insurance (35 [41.7%] vs. 330 [64.7%]) compared to those with adequate literacy. ADI percentile was significantly higher in those with limited health literacy compared to those with adequate literacy, indicating a higher level of social deprivation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic information between those with adequate and limited health literacy (n = 594).

| Parameter | Adequate health literacy | 95% confidence interval | Limited health literacy | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 54 ± 15 | 52.7–55.3 | 58 ± 18 | 54.1–61.9 | <0.001* |

| Gender, % (N) | 0.787 | ||||

| Male | 49.7% (253) | 51.1% (43) | |||

| Female | 50.3% (257) | 48.9% (41) | |||

| Race, % (N) | 0.108 | ||||

| Black | 19.6% (100) | 25.0% (21) | |||

| White | 73.9% (377) | 65.5% (55) | |||

| Other | 6.5% (33) | 9.5% (8) | |||

| Employed, % (N) | 65.1% (332) | 40.5% (34) | <0.001* | ||

| Private insurance, % (N) | 64.7% (330) | 41.7% (35) | <0.001* | ||

| ADI, mean ± SD | 32.2 ± 21.0 | 30.4–34.0 | 37.8 ± 20.0 | 33.5–42.1 | 0.027* |

| BRIEF, mean ± SD | 19.6 ± 0.7 | 19.5–19.7 | 13.2 ± 2.8 | 12.6–13.8 | <0.001* |

SD: standard deviation; ADI: area deprivation index; BRIEF: Brief Health Literacy Screening Tool.

*Significantly different (p < 0.05).

Health literacy and patient-reported outcome measures

A total of 587 patients (98.8%) completed PROMIS physical and mental health scores. Significantly lower PROMIS physical health scores and mental health scores were observed in patients with limited health literacy compared to those with adequate health literacy (Table 2). In the 586 patients (98.7%) who completed the pain VAS, those with limited health literacy had higher average pain VAS score compared to those with adequate health literacy (5.3 ± 2.9 vs. 4.6 ± 2.7, p = 0.017; Table 2). For the 563 patients (94.8%) who completed the ASES score, scores did not differ significantly between those with limited versus adequate health literacy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of patient-reported outcomes between those with adequate and limited health literacy.

| Outcome measure | Adequate health literacy (mean ± SD) | 95% confidence interval | Limited health literacy (mean ± SD) | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASES (N = 563) | 50.5 ± 23.6 | 48.5–52.5 | 48.0 ± 25.4 | 45.9–50.1 | 0.385 |

| Pain VAS (N = 586) | 4.6 ± 2.7 | 4.4–4.8 | 5.3 ± 2.9 | 4.7–6.0 | 0.017* |

| PROMIS physical (N = 587) | 46.3 ± 8.0 | 45.7–46.9 | 42.3 ± 9.2 | 41.6–43.0 | <0.001* |

| PROMIS mental (N = 587) | 52.1 ± 8.8 | 51.4–52.8 | 48.4 ± 10.3 | 47.6–49.2 | 0.001* |

SD: standard deviation; ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score; VAS: visual analog scale; PROMIS: Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System.

*Significantly different (p ≤ 0.05).

Discussion

Limited health literacy represents a challenge to orthopedic surgeons trying to provide effective patient-centered care. This cross-sectional study of 594 patients presenting to an outpatient shoulder and elbow clinic found that 84 patients, or almost 15%, had limited health literacy and that it was more common in those with older age, government insurance, lack of employment and greater social deprivation. PROMIS scores and pain VAS were significantly worse in patients with limited health literacy. These findings represent an opportunity to improve patient access to care and adapt existing systems to ensure appropriate understanding of patient assessment measures on the part of both surgeons and patients. Recognition of the problem of limited health literacy in shoulder and elbow patients and careful consideration in the selection of the health literacy assessment tools and patient-reported outcome measures used in this population are critical to providing equitable care for all.

The prevalence of limited health literacy identified in this study was lower than that reported previously, but there is considerable variability among those reports. One study of 200 patients presenting to an outpatient hand surgery clinic reported that 86 (43%) of patients had limited health literacy 14 as measured with the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) instrument. Another study of 248 orthopedic patients in the emergency department identified limited health literacy in 120 (48%) patients using the NVS and in 171 (69%) patients using a more musculoskeletal-focused questionnaire, Literacy in Musculoskeletal Problems (LiMP). 15 A recent study of 230 patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty found that 58 (25.2%) of patients had limited health literacy as measured by BRIEF. 13 BRIEF is a four-question screening tool, whereas the NVS and LiMP are longer questionnaires. The LiMP specifically assesses musculoskeletal health literacy, requiring a more technical knowledge base than many other health literacy assessments, 15 whereas the NVS focus on numeracy can affect results depending on a patient's comfort and skill with numbers. 22 The more complex nature of these assessments may contribute to the higher rates of limited health literacy reported. In general, the lack of consistency in assessments of health literacy in orthopedic literature hinders our ability to grasp the scope of this problem in different populations. A short questionnaire like the BRIEF may be useful for identifying the most significant limitations in health literacy in a population, whereas a longer specific questionnaire may help to identify the details of health literacy limitations and guide intervention targets. Consideration of the goals of the health literacy assessment and the administration setting can help guide instrument selection in practice.

An additional contributing factor to the lower rate of limited health literacy identified in our study compared to previous studies may be related to our specific study setting and may reflect particular difficulties navigating aspects of the healthcare system for those with the most limited health literacy, including appointment scheduling, obtaining a referral and bringing required insurance documentation, which may be necessary to make it to an outpatient subspecialty orthopedic appointment. 23 Our study identified a rate of 14.1% in an orthopedic clinic, but the higher rates of limited health literacy seen in studies in the emergency department setting may be more reflective of the true incidence of limited health literacy in the general population because there are fewer logistical hurdles to obtaining care in that setting. 15 The possible barriers in our study, such as the potential obstacles of referrals and insurance documentation may also exist in different health systems or practice groups when patients try to access care, leading to circumstances where patients with the most limited health literacy may not even reach the office. Physicians and healthcare administrators should continually assess the barriers to care, particularly for those with limited health literacy, that exist in their specific practice settings. Methods of appointment scheduling, instructions regarding referrals, and the survey length and processes used for obtaining patient-reported outcomes prior to clinic are all potential areas for improvement to help minimize barriers to care for those with limited health literacy.

The current findings suggest that social deprivation may be a useful factor to consider with health literacy in the effort to provide equitable healthcare to all patients. ADI has not been previously studied as it relates to health literacy, but ADI is calculated based partly on income and education level, 20 factors that have been shown to be correlated with health literacy in orthopedic populations.14,15 Our results suggest that both specific social factors like income and composite metrics like ADI are related to health literacy. Social health as measured by ADI has been shown to have an independent impact on patient-reported outcome scores in orthopedic patients. 24 In health literacy screening, identification of limited health literacy in a patient should also potentially raise suspicion for social deprivation. The implications of high social deprivation on orthopedic care are not known, but a more comprehensive understanding of patient challenges is key to providing high-quality patient-centered care.

Similar to other orthopedic populations in the literature, shoulder and elbow patients with limited health literacy in this study were older, less likely to employed, and more likely to have government insurance compared to those with adequate health literacy. In the outpatient hand surgery clinic setting, older age, lower income, and public insurance have been correlated with limited health literacy. 14 Race and gender were not associated with adequacy of health literacy in the current study. However, in a study of patients in the emergency department with orthopedic complaints, Caucasian race and higher education level were associated with better health literacy. 15 Differences in the demographic variables associated with limited health literacy may also be due to differences between the studied patient populations and the choice of literacy assessment tools. For example, age may not correlate with limited health literacy in a sports medicine clinic largely treating young active adults because of less age variability compared to that in an emergency department.

PROMIS metrics (physical health and mental health) and pain VAS showed statistically significant differences in baseline values depending on level of health literacy in this study, whereas ASES did not. These differences in some patient-reported outcome measures for those with and without limited health literacy may be due to true differences in mental health and function between the groups. Studies of hip and knee arthroplasty patients have found that patients with limited health literacy have lower expectations for surgery and lower patient-reported outcomes after surgery (Western Ontario and McMasters Universities Arthritis Index [WOMAC]).11,25 However, it is also important to consider that differences between the groups may be an artifact of the metrics themselves. Patient-reported outcome assessments may give inaccurate results if used in populations substantially different from those in which they were originally validated, which is often difficult to determine because health literacy is not documented in most validation studies. 26 A mixed-methods analysis of multiple common orthopedic outcome tools found that even though the tools were at an appropriate reading level, focus group feedback still identified formatting and language improvements that could aid those with limited health literacy. 27 Patient-reported outcome metrics are important to patient care in orthopedics, but only if they accurately measure what they intend to measure across all patients. Validation studies of patient-reported outcome measures in populations with limited health literacy should be prioritized. Consideration of shorter or simpler assessments may be beneficial in the interim. Surgeons should prioritize the use of patient-reported outcome measures that are widely applicable across levels of health literacy when selecting measures in practice.

This study does have limitations. It evaluated one group of patients at one point in time, and therefore no conclusions can be drawn about the causes of our findings. This study was performed at a tertiary referral center, and the results may not be generalizable to practices in other settings with differing patient populations. Larger studies of the demographic factors impacting health literacy and the relationship of patient-reported outcomes to health literacy are needed. All patients in this study were English-speaking, and therefore the impact of primary language differences on health literacy could not be assessed. The study used only one of several validated metrics for health literacy, which may also limit generalizability. This study also used four specific patient-reported outcome measures that are routinely collected on all new patients at our institution, and other commonly used instruments might show different associations with health literacy. Finally, this study assessed patients only at their first visit. Future studies should assess the impact of health literacy on treatment and outcomes and how patient-reported outcomes change over time.

Conclusion

In this study, approximately 15% of new patients presenting to a shoulder and elbow clinic had limited health literacy, which was more common in patients with older age, unemployment, government insurance and social deprivation. PROMIS physical and mental health scores and pain VAS were significantly worse in patients with limited health literacy. Shoulder and elbow surgeons should consider the prevalence of limited health literacy in their patients, those who may be at higher risk, and the impact of literacy on patient-reported outcome measures to ensure the provision of high-level equitable care.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Melissa A. Wright https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5404-6547

Aman Chopra https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6654-4030

References

- 1.Kindig DA, Nielsen-Bohlman L. Health literacy: a presription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academics Press, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haun J, Noland-Dodd V, Varnes J, et al. Testing the BRIEF health literacy screening tool. Fed Pract 2009; 26: 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, et al. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 175–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenbaum AJ, Uhl RL, Rankin EA, et al. Social and cultural barriers: understanding musculoskeletal health literacy: AOA critical issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98: 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker DW, Parker RM, Williams MV, et al. The relationship of patient Reading ability to self-reported health and use of health services. Am J Public Health 1997; 87: 1027–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker DW, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Functional health literacy and the risk of hospital admission among medicare managed care enrollees. Am J Public Health 2002; 92: 1278–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett CL, Ferreira MR, Davis TC, et al. Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 1998; 16: 3101–3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, et al. Health literacy and preventive health care use among medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care 2002; 40: 395–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_10/sr10_260.pdf (accessed March 30, 2023).

- 10.Bone and Joint Initiative. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States, https://www.boneandjointburden.org/docs/The%20Burden%20of%20Musculoskeletal%20Diseases%20in%20the%20United%20States%20(BMUS)%203rd%20Edition%20(Dated%2012.31.16).pdf (accessed April 25, 2022).

- 11.Narayanan AS, Stoll KE, Pratson LF, et al. Musculoskeletal health literacy is associated with outcome and satisfaction of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2021; 36: S192–S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roh YH, Lee BK, Park MH, et al. Effects of health literacy on treatment outcome and satisfaction in patients with mallet finger injury. J Hand Ther 2016; 29: 459–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puzzitiello RN, Colliton EM, Swanson DP, et al. Patients with limited health literacy have worse preoperative function and pain control and experience prolonged hospitalizations following shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2022; 31: 2473–2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menendez ME, Mudgal CS, Jupiter JB, et al. Health literacy in hand surgery patients: a cross-sectional survey. J Hand Surg Am 2015; 40: 798–804, e792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenbaum AJ, Pauze D, Pauze D, et al. Health literacy in patients seeking orthopaedic care: results of the literacy in musculoskeletal problems (LIMP). Project. Iowa Orthop J 2015; 35: 187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wofford JL, Mansfield RJ, Watkins RS. Patient characteristics and clinical management of patients with shoulder pain in U.S. Primary care settings: secondary data analysis of the national ambulatory medical care survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005; 6: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haun J, Luther S, Dodd V, et al. Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: implications for assessment selection in research and practice. J Health Commun 2012; 17: 141–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stagliano V, Wallace LS. Brief health literacy screening items predict newest vital sign scores. J Am Board Fam Med 2013; 26: 558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace LS, Cassada DC, Rogers ES, et al. Can screening items identify surgery patients at risk of limited health literacy? J Surg Res 2007; 140: 208–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969–1998. Am J Public Health 2003; 93: 1137–1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, et al. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2014; 161: 765–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med 2005; 3: 514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy H, Janke A. Health literacy and access to care. J Health Commun 2016; 21: 43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wright MA, Adelani M, Dy C, et al. What is the impact of social deprivation on physical and mental health in orthopaedic patients? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019; 477: 1825–1835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hadden KB, Prince LY, Bushmiaer MK, et al. Health literacy and surgery expectations in total hip and knee arthroplasty patients. Patient Educ Couns 2018; 101: 1823–1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone AA, Broderick JE, Junghaenel DU, et al. PROMIS Fatigue, pain intensity, pain interference, pain behavior, physical function, depression, anxiety, and anger scales demonstrate ecological validity. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 74: 194–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadden K, Prince LY, Barnes CL. Health literacy demands of patient-reported evaluation tools in orthopedics: a mixed-methods case study. Qual Manag Health Care 2018; 27: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]