Abstract

Background

Lamotrigine clearance can change drastically in pregnant women with epilepsy (PWWE) making it difficult to assess the need for dosing adjustments. Our objective was to characterize lamotrigine pharmacokinetics in PWWE during pregnancy and postpartum along with a control group of nonpregnant women with epilepsy (NPWWE).

Methods

The Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study was a prospective, observational, 20 site, cohort study conducted in the United States (December 2012 and February 2016). Inclusion criteria included patients aged 14–45 years, gestational age <20 weeks at the time of recruitment, IQ >70 points, and receiving lamotrigine. PWWE participated throughout pregnancy and 18 months postpartum with NPWWE having matched visit intervals. Plasma drug and hormone concentrations were measured at each of the seven visits. A population mixed‐effects modeling approach was used to describe lamotrigine clearance change.

Results

221 (170 PWWE, 51 NPWWE) women were included. Baseline apparent clearance (clearance for NPWWE and when not pregnant for PWWE) was identical between the two groups (2.79 L/hour. with 36% between‐subject variability). Two subpopulations were identified in PWWE: ~91% of PWWE had a maximum increase to 275% of baseline clearance with 50% of the maximum increase reached at 12 weeks gestational age and ~9% had no significant change in clearance during gestation. Following delivery, a first‐order mono‐exponential decline (1.27 weeks−1) in clearance as a function of postpartum week described a return of clearance to baseline. The use of estrogen‐based medication and enzyme‐inducing antiseizure medications increased nonpregnant clearance by a further 0.33‐fold and 0.84‐fold, respectively.

Discussion

During pregnancy, 91% of PWWE experience a 275% change from nonpregnant baseline in lamotrigine clearance whereas the remaining PWWE experience little to no change. Nonpregnant baseline lamotrigine clearance was higher in both PWWE and NPWWE with the administration of oral estrogen‐containing medications. Our results are of clinical importance as they indicate a subpopulation without the need for substantial dose changes during pregnancy and a source of potential difference across nonpregnant individuals.

Keywords: epilepsy, hormones, lamotrigine, pharmacokinetics, pregnancy

1. INTRODUCTION

Lamotrigine is one of the most frequently prescribed antiseizure medications (ASMs) in pregnancy, 1 , 2 primarily driven by lamotrigine being found to have low teratogenic potential in multiple large pregnancy registry studies and favorable neurodevelopmental outcomes following prenatal exposure. 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Although lamotrigine is relatively safe in pregnancy, blood concentrations fall significantly during pregnancy returning to preconception levels postpartum. Pregnancy‐related physiological changes alter pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine with the potential to worsen seizure control. 7 , 8 Clinically, doses are increased in pregnancy and subsequently decreased in postpartum to maintain therapeutic benefit which may or may not be guided by serum lamotrigine therapeutic concentration monitoring. 2 , 8 , 9

Lamotrigine is predominantly metabolized by UDP‐glucuronosyltransferases (UGT), particularly UGT1A4, to lamotrigine‐2‐N‐glucuronide. 10 , 11 , 12 In vitro evidence suggests upregulation of the UTG1A4 enzyme by estradiol is mediated through estrogen receptor‐α (ERα), specifically protein‐1 (Sp1). 13 Thus, estradiol increases in pregnancy are a potential mechanism for increasing lamotrigine clearance in pregnancy. This observation is supported by studies showing increases in both metabolite concentration and metabolite‐to‐parent ratios in pregnancy. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 Lamotrigine clearance increases as early as 5 weeks gestational age 19 with increases of over 250% by the end of gestation compared with preconception baseline. 7 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 One single‐site study reported that pregnant women with epilepsy (PWWE) on lamotrigine fall into one of two groups: women experiencing a significant increase in clearance during pregnancy (77% of the population) and women experiencing little to no increase in clearance during pregnancy (23% of the population). 21 The etiology leading to the presentation of the two groups has not been identified to date.

Few formal analyses have been performed characterizing lamotrigine pharmacokinetics during pregnancy. 19 , 21 Studies are limited by logistical and ethical considerations for collecting many samples from a pregnant individual, leading to sparse data. No prior studies have enrolled comparator nonpregnant women with epilepsy (NPWWE) to understand differences in lamotrigine pharmacokinetics between PWWE and NPWWE. Traditional statistical analyses are difficult with such datasets, limiting our understanding of ASM dispositional changes during gestation. The Maternal Outcomes and Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (MONEAD) study prospectively recruited both PWWE and NPWWE providing not only the ability to characterize ASM clearance changes that happen during pregnancy but also allowing comparison to a nonpregnant control group. The objectives of this analysis were to characterize lamotrigine pharmacokinetics in both PWWE and NPWWE and to identify clinically relevant covariates affecting lamotrigine disposition.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design

MONEAD is a National Institutes of Health (NIH)‐funded, 20‐site prospective, observational cohort study with recruitment of both NPWWE and PWWE. Key inclusion criteria for women with epilepsy included ages 14–45 years and the ability to maintain a daily medication and seizure diary. Exclusion criteria for all women included IQ < 70, other major medical illnesses, history of switching ASMs within 1 month prior to enrollment or during pregnancy, and recreational drug use. PWWE‐specific inclusion criteria included <20 weeks gestational age at the time of recruitment. PWWE‐specific exclusion criteria included exposure to non‐ASM teratogens during pregnancy, a detected fetal major congenital malformation, or history of known genetic disorder in herself or a primary relative. The study was approved by the individual site Institutional Review Boards and consent was obtained from all adult patients prior to participation.

At enrollment, participants self‐identified their race (American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, White, multiracial, other/unknown) and ethnicity (Hispanic, non‐Hispanic). Both the pregnant and nonpregnant cohorts were enrolled in the study for a total of seven visits. For PWWE, visits were scheduled during pregnancy (visits 1–3), during the labor and delivery hospitalization (visit 4), and at 3, 6, and 9 months postpartum (visits 5–7). For NPWWE, the seven visits were spread over 18 months with similar time points to PWWE. At each visit, blood samples were collected via phlebotomy, missed doses were recorded via daily diaries, and information on ASM dose changes, time of last dose, comedications, and gestational age (calculated basedon the estimated due date) was collected. The nonpregnant control cohort was recruited to resemble the pregnant woman cohort regarding race and ethnicity, seizure type, seizure frequency, ASM monotherapy versus polytherapy, and specific ASMs. Visits where dose or concentration information was missing were excluded from analyses. It should be noted that the ASM doses and regimen, including any change to dose and comedications throughout the study were managed by the patient's health care providers. The study protocol did not mandate any change to medications or doses due to the observational nature of the study.

Plasma ASM concentrations were measured via validated liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry assay at the University of Minnesota (MONEAD Pharmacokinetics Core Laboratory, Minneapolis). 25 All samples from an individual were run on the same analytical run to decrease analytical variability. Approximately 7% of all samples were rerun on subsequent runs to ensure reproducibility.

2.2. Population pharmacokinetic analysis

Population pharmacokinetic analyses were performed using a qualified installation of nonlinear mixed‐effects modeling software, NONMEM version 7.4.2 (ICON Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD, USA) coupled with Pirana version 2.8.1. Plots were constructed using R version 3.6.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). The first‐order conditional estimation method with η‐ε interaction (FOCE‐I) was employed for all model runs.

Literature evidence suggests lamotrigine exhibits first‐order linear pharmacokinetics well described by a one‐compartmental model. 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 An alternative model exists for lamotrigine which assumes concentrations to be at steady‐state due to the relatively long elimination half‐life of lamotrigine (23–37 h) compared with dosing intervals, leading to minor changes in concentrations over a dosing interval. 19 , 21 Both the one‐compartment and steady‐state infusion models were tested. The steady‐state infusion model used was:

where Cpred is the predicted lamotrigine concentration, Dosing Rate is the total dose of lamotrigine per 24 hours, and CL/F is the apparent oral clearance of lamotrigine. Interindividual variability (IIV) was modeled using an exponential error model for parameters in both models:

Where θ i is the parameter estimate for the ith individual, TVθ is the typical value of the parameter in the population, η θi are individual‐specific random effects for the ith individual and assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance ω. 2 This assumption imparts a log‐normal distribution on the parameter of interest and expresses the variability as a coefficient of variation (CV). For each model additive, proportional, and combined residual unexplained variability (RUV) models were evaluated. Each was assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and variance σ. 2 Model development was guided by goodness‐of‐fit criteria, including diagnostic scatter plots, the plausibility of parameter estimates, the precision of parameter estimates, and our knowledge of physiological changes in pregnancy.

For the one‐compartment model, CL/F and V/F (apparent volume of distribution) were allometrically scaled with the last nonpregnant weight (weight at the last postpartum study visit) for both cohorts. As the steady‐state infusion model has no V/F parameter, only CL/F was scaled allometrically similar to the one‐compartment model.

Gestational age (GA) was used to capture changes in pharmacokinetic parameters as it may reflect factors that change throughout pregnancy, many of which are co‐linear and correlated to gestational age (e.g., estradiol concentrations, esterone concentrations, progesterone concentrations, and body weight) as was observed for this study as well via graphical analysis. It has been established in a prior study that steady‐state infusion models for lamotrigine using GA as the independent variable have a better fit as compared to estradiol. 19 Therefore, we chose to use GA as the independent variable.

Change in CL/F and V/F were explored as a function of GA using three functions: linear increase, quadratic increase, and E max model. The linear increase parametrizes a slope for change in parameter with GA. The quadratic function uses two parameters to describe change, one for GA and a second to add curvature for the square of GA. An E max model is parametrized with two parameters; however, it describes a curve with a theoretical maximum value of change.

Where Δ refers to a change in parameter, is the maximum value of change in the parameter, GA is the gestational age in weeks and is the gestational week at half‐maximal change. A mixture model subroutine was implemented in NONMEM to identify subpopulations with differences in change in CL/F with GA. In a mixture model, one proposes the possibility of more than one population without a priori defining patients to be in one population or the other. NONMEM assigns each patient to a subpopulation by determining which subpopulation is more likely given an individual's data.

2.3. Covariate analysis

The effect of clinically relevant covariates on CL/F was guided graphically. Forward addition (p‐value <0.05) and backward elimination (p‐value <0.01) were used to add covariates to the model. Covariates known to be correlated to GA (e.g., estradiol or progesterone concentrations) were not tested as covariates due to collinearity which was verified graphically. The following covariates were tested in the model: age, ethnicity, smoking status, use of hormonal medications (estrogen‐containing vs. those medications not containing estrogen), and use of enzyme‐inducing ASMs (carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and primidone).

2.4. Model evaluation

A nonparametric bootstrap procedure 33 was employed for model evaluation. One thousand data sets were generated by random sampling with replacement from the original data set using Perl speaks NONMEM linked to NONMEM. Population parameters were estimated for each bootstrap dataset using the final model. The bootstrap results were pooled only from the runs with successful convergence and covariance steps. The 2.5th, 50th, and 97.5th percentiles of the parameter distributions were computed and compared with the results from the NONMEM final model.

Physiologically lamotrigine V/F has been estimated to be between 1.0 and 1.47 L/kg, 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 making proportional error model estimates the most physiologically relevant. The large variation in estimates could indicate a deficiency of data to adequately estimate V/F. We thus opted to run a sensitivity analysis on the V/F parameter to see the effect on the CL/F nonpregnant parameter and its change during pregnancy with the three residual error models.

2.5. Subpopulation analysis

The subpopulations identified via the mixture model were further analyzed for differences, including differences in body weight, race, ethnicity, age, smoking, alcohol, newborn biological sex, and estrone, estradiol, and progesterone concentrations, between the two subpopulations using a linear mixed‐effects models (implemented in R). 34 It should be noted that the subpopulation analysis is a post hoc analysis and is not a part of the population pharmacokinetic analysis.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patient demographics and treatment

Our analysis included a total of 221 (170 PWWE, 51 NPWWE) women on lamotrigine. Demographics between PWWE and NPWWE were comparable (Table 1). We observed that in the PWWE cohort, the total daily dose was higher during pregnancy compared with postpartum. Additionally, the total daily dose for NPWWE was lower compared with the PWWE pregnancy visits. The use of hormonal medications was not limited to NPWWE and postpartum PWWE as some women were prescribed hormonal medications during pregnancy for indications, such as history of preterm labor, history of miscarriage, and in vitro fertilization protocols.

TABLE 1.

Summary of patient demographics and medications.

| Cohort | Pregnant women with epilepsy | Nonpregnant women with epilepsy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 170 | 51 |

| Number of Samples | 936 | 291 |

| Age, Median (range), years | 31.0 (20.0–43.0) | 29.0 (16.0–40.0) |

| Race | ||

| Asian | 4 | 1 |

| African American | 12 | 2 |

| White | 146 | 47 |

| Native Hawaiian | ‐ | ‐ |

| Multiracial | 6 | ‐ |

| Other/Unknown | 2 | 1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 26 | 9 |

| Non‐Hispanic | 134 | 42 |

| Gestational age | ||

| Median (range), weeks | 5–42 | ‐ |

| Postpartum weeks | ||

| Median (range), weeks | 0–48 | ‐ |

| Weight | ||

| Median (range), kg | ||

| Trimester 1 | 65.5 (47.0–122.5) | |

| Trimester 2 | 73.9 (47.5–127.0) | |

| Trimester 3 | 76.5 (52.2–127.2) | |

| Postpartum/Nonpregnant | 70.5 (41.2–138.3) | 68.6 (51.2–111.8) |

| Lamotrigine total daily dose | ||

| Median (range), mg | ||

| Trimester 1 | 400 (100–900) | |

| Trimester 2 | 500 (50–1900) | |

| Trimester 3 | 600 (50–2100) | |

| Postpartum/nonpregnant | 400 (50–1200) | 350 (125–800) |

| Hormonal medications | ||

| Progestin‐only based | 20 | 4 |

| Estrogen‐only based | ‐ | ‐ |

| Combination | 9 | 13 |

| None | 141 | 33 |

| Antiseizure medications | ||

| Enzyme‐inducing | 7 | 2 |

| Others | 163 | 49 |

3.2. Pharmacokinetic analysis

3.2.1. Model building

Both the steady‐state infusion and one‐compartment models were successfully implemented in NONMEM. Nonpregnant state was defined for both NPWWE at all visits and PWWE at postpartum visits. In the one‐compartment model, the residual error model type significantly affected the estimation of both nonpregnant V/F and the change in V/F over pregnancy. The combined and additive error models estimated nonpregnant V/F to be double (130 L) and nearly triple (162 L) the value, respectively, of the proportional error model estimate (68.3 L).

For the sensitivity analysis, we fixed V/F at five different values (70 L, 95 L, 100 L, 150 L, and 180 L). All other model parameters including nonpregnant CL/F and change in V/F, and CL/F by GA were estimated for all three GA functions (linear, quadratic, and Emax). The estimation of the nonpregnant CL/F parameter was not significantly affected (range 2.9 L/hour. –3.1 L/hour) in any of the sensitivity analyses. Additionally, the sensitivity analyses did not affect change in CL/F in any of the three evaluated GA models. The selection of the residual error model was also not consequential in the estimation of either nonpregnant CL/F or its change with pregnancy. However, the estimation of V/F and change in V/F as a function of GA was affected by the residual error model formulation. At each sensitivity analysis in each GA model, the proportional error model had the lowest change in V/F with the GA parameter. Whereas estimates for change in V/F with GA parameter were nearly threefold and twofold being estimated for additive and combined error models, respectively. The sensitivity analysis confirmed the lack of unique information to support the estimation of V/F.

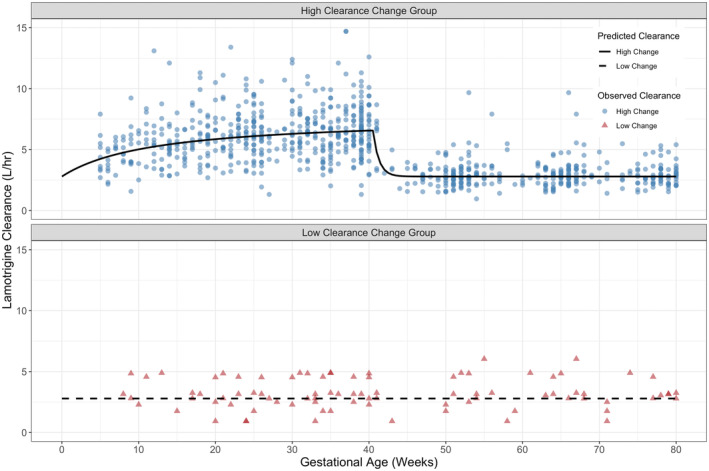

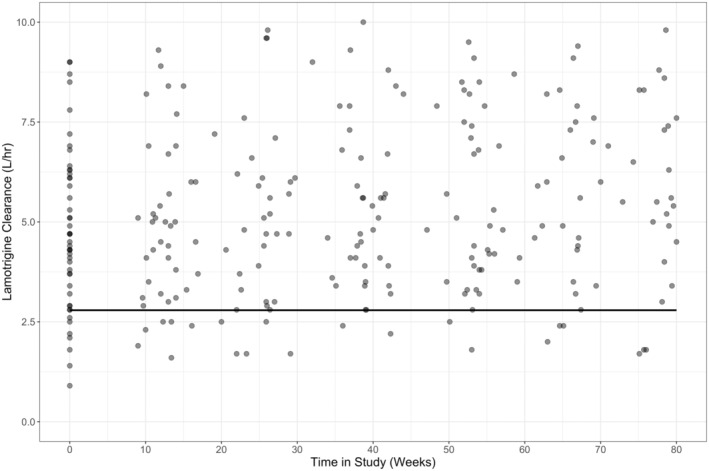

As the estimation of V/F is sensitive to the error model chosen, the steady‐state infusion model was preferred which does not estimate V/F. Using goodness‐of‐fit plots and parameter precisions, it was identified that an E max model best described the change in clearance during pregnancy. An exponential decline model was used to describe the return of clearance to baseline postpartum; however, the zero‐order rate was not estimable and hence fixed to a literature value. We tested for the possibility that a fraction of our pregnant women belongs to a subpopulation with a significantly lower rate of enhanced clearance via the implementation of mixture models in NONMEM. Two subpopulations were identified with an average of nearly 9% (represented by n = 13, or ~8%, of the cohort) of PWWE population experiencing no estimable change in clearance during pregnancy (low clearance change subpopulation) whereas the remaining 91% of PWWE experienced an average 4.9 L (275% of baseline) increase in clearance during pregnancy (high clearance change subpopulation) which reached half‐maximal clearance increase (EC50) by 12 weeks GA. The inclusion of the mixture model resulted in a significant drop in the OFV (ΔOFV = −40, p < 0.001) and reduced the between‐subject variability on E max by 25%. A plot of the model post hoc and observed clearances are shown in Figure 1. Comparatively, Figure 2 shows that post hoc and observed clearances for the NPWWE population significantly contrast the PWWE group.

FIGURE 1.

Post hoc estimates of lamotrigine clearance in pregnant women with epilepsy with high clearance change (top), and low clearance change (bottom). Data points indicate the observed CL/F. Lines through the data indicate population‐predicted CL/F profiles.

FIGURE 2.

Post hoc estimates of lamotrigine clearance in nonpregnant women with epilepsy. Data points indicate the observed CL/F. Solid lines through the data indicate population‐predicted CL/F profiles.

3.2.2. Covariate analysis

The relationship between clinical covariates and clearance was examined by ETA plots. The forward addition and backward elimination process revealed two statistically significant covariates on nonpregnant clearance. Use of hormonal medication (estrogen‐containing vs. those medications not containing estrogen) and use of enzyme‐inducing ASM increased nonpregnant clearance by a further 0.33‐fold and 0.84‐fold, respectively.

3.2.3. Model evaluation

Diagnostic plots for different stages of pregnancy revealed that the final model was consistent with observed data (Figures S2 and S3). The final estimated model parameters were within 13% of the medians obtained from the bootstrap procedure (Table 2). The 95% confidence interval (CI) of parameters from NONMEM were comparable to bootstrap 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. The final model equations to estimate clearance during pregnancy and postpartum are presented in Table S1. The simultaneous fitting of model equations provided an adequate description of the data and resulted in physiologically meaningful parameter estimates with considerable precision.

TABLE 2.

Final model parameter estimates.

| Parameter | Estimate (%RSE) | Shrinkage a (%) | Bootstrap 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| (L/hour) | 2.79 (3) | ‐ | 2.64–2.93 |

| (L/hour) | 4.9 (9) | ‐ | 4.07–5.73 |

| (weeks) | 12 (25) | ‐ | 6.5–17.58 |

| (1/weeks) | 1.27 (FIXED) | ‐ | ‐ |

| P2 (%) | 9.04 (30) | ‐ | 3.3–14.3 |

| Estrogen‐based medications (%) | 33.3 (28) | ‐ | 13.5–53.0 |

| Enzyme‐inducing ASM (%) | 83.9 (28) | ‐ | 62.8–96.3 |

| BSV (%) | 35.9 (8) | 10 | 29.8–39.21 |

| BSV (%) | 46.3 (12) | 21 | 32.3–53.2 |

| RUVproportional (%) | 23.4 (9) | 11 | 18.1–27.2 |

| RUVadditive (μg/mL) | 0.56 (52) | 11 | 0.15–0.81 |

Abbreviations: BSV, between‐subject variability; RSE, relative standard error; RUV, residual unexplained variability.

Shrinkage refers to the percent of regression to the mean for the parameter in question. , baseline nonpregnant clearance for both pregnant and nonpregnant women with epilepsy (L/hour); , maximum clearance increase during gestation (L/hour); , gestational age at 50% of maximum (weeks); , first‐order rate of return of lamotrigine clearance to baseline in postpartum; P2, % population with no clearance change; estrogen‐based medications, % increase in baseline clearance with the use of estrogen‐based hormonal medications; enzyme‐inducing ASM, % increase in baseline clearance with the use of enzyme‐inducing antiseizure medications.

3.3. Subpopulation analysis

Further investigations were performed to identify relationships between any clinically relevant variables available in the study and the two mixture subpopulations for CL/F. However, no differences were observed in any of the tested variables (Figure S1). Additional descriptive analyses were performed between the two subpopulations (Table S2) which indicate an increase in total daily dose in both subpopulations during pregnancy, however only the low clearance subpopulation has an increase in dose‐normalized concentrations. This is a further indication of the existence of a subpopulation that experiences very little to no change in lamotrigine clearance during pregnancy. Additionally, the post‐partum total daily dose and the dose‐normalized concentrations are comparable between the two subpopulations indicating the clearance difference only during pregnancy.

4. DISCUSSION

We characterized lamotrigine pharmacokinetics in the largest known group of PWWE and NPWWE to date. Lamotrigine clearance increased significantly during pregnancy leading to substantial decreases in lamotrigine concentrations. Additionally, lamotrigine clearance decreased postpartum in the PWWE cohort and was comparable to NPWWE clearance after approximately 3 weeks. The population pharmacokinetic model identified two subpopulations of PWWE during pregnancy in which lamotrigine clearance increased in a saturating fashion with 275% of baseline for 91% of the pregnant women whereas the remaining 9% experienced no change in clearance. An attempt was made to identify the etiology of the two subpopulations of clearance change with available clinical covariates. One plausible mechanism of clearance was probable differences in estradiol and estrone trends between the two subpopulations during pregnancy and postpartum. No significant differences could be identified between the two subpopulations for any other covariates. Although not available and tested in this analysis, clearance changes being affected by mutations downstream of an estradiol receptor (ERα) may be a possible mechanism. 13 Another possible mechanism is through mutations in the primary metabolic enzyme for lamotrigine, UGT1A4. Although genetic polymorphisms may contribute to the formation of subgroups, currently there are no studies that simultaneously evaluate multiple genes within the lamotrigine pharmacokinetic pathway, nor are there studies exploring the role of pharmacogenomics in predicting the degree of accelerated lamotrigine clearance during pregnancy.

The changes characterized in the population model were consistent with the observed dose‐normalized‐concentration changes throughout gestation and increases in lamotrigine clearance in other studies. 7 , 20 , 21 , 35 The existence of two populations of pregnant women who exhibit differences in clearance is confirmatory to a smaller, independent study in 60 women. 21 Authors in the smaller study were able to characterize approximately 23% of the study population with a small clearance change during pregnancy (0.0115 L/hour/week). However, in our study, we identified a smaller group of the population (9%) that had no estimable clearance change during pregnancy. The difference in the proportion between the two studies could possibly be attributed to the population that was sampled, which was in the absence of the etiology of the subgroups. Regardless, both of these studies indicate a number of women who may not require dose changes to maintain therapeutic levels of lamotrigine during pregnancy. Routine therapeutic drug monitoring is thus recommended in PWWE taking lamotrigine, as the etiology of the lack of clearance change during pregnancy is not yet identified. Uninformed dose increases in this populations have been projected to increase lamotrigine concentrations to toxic levels. 36

A unique feature of our analysis is the modeling of both GA and postpartum weeks as continuous covariates. This approach is clinically relevant and more statistically powerful than accounting for the effect of these covariates in a categorical manner. Physiologically, clearance is expected to gradually change over time rather than displaying sudden variations over trimesters. Overall, the model predicted an E max type increase in clearance during pregnancy and a nonlinear exponential decline in clearance after delivery. Estradiol is known to increase throughout pregnancy and it is hypothesized that estradiol upregulates UGT1A4 causing increases in clearance. 13 An E max model is thus consistent with physiological changes expected in enzyme kinetics which follow an E max pattern (Michaelis–Menten kinetics). 37 Due to collinearity, physiological relevance, as well as statistical performance, we opted to use GA (i.e., an indirect measure of estradiol) over individual estradiol concentrations as predictor variables for clearance change during pregnancy. Attempts were made during our analyses to quantify gestational changes to the volume of distribution, however, sensitivity analysis revealed these to be unidentifiable. Although the volume parameter in nonpregnant states could be fixed, doing so propagated the misidentification of the volume change trend in pregnancy without affecting the clearance estimates and justified the use of the continuous infusion model approach. The convenience and sparse nature of the pharmacokinetic sampling were identified as a plausible reason.

Covariate analysis revealed that the use of estrogen‐based hormonal medications or enzyme‐inducing medications significantly increased nonpregnant clearance resulting in decreases in nonpregnant lamotrigine concentrations. The effect of hormones and enzyme‐inducing ASMs on lamotrigine clearance is well established in the literature. 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 38 , 39 The Lamictal package insert recommends lamotrigine dose adjustments for women starting estrogen‐containing medication or any enzyme‐inducing ASMs. 38 Etiologically, both of these covariates upregulate UGT1A4 and increase the clearance mechanism of lamotrigine.

There are limitations to these analyses. First, gestation‐related changes in volume were not quantified. However, clinical dosing of lamotrigine is guided by steady‐state lamotrigine concentrations which our model adequately captures. Second, identification of etiology of the two clearance change subpopulations could not be identified despite the availability of several covariates which were not available in previous studies. Further explorations of etiology are planned especially with polymorphisms of UGTs. However, it is worthwhile to mention that this study confirms the existence of two subpopulations of women, one of which may not require lamotrigine dose changes during pregnancy. Lastly, it should be noted that the study was conducted only in the United States in a relatively white, non‐Hispanic population. The genetic variability may be limited and not generalizable to individuals with different ancestral genetics. However, regardless of race or ethnicity, pregnancy leads to a significant increase in hormones that upregulate UGTs. Hence, a significant population regardless of ethnicity and race may experience changes as described by our analysis.

This is the largest study characterizing changes in lamotrigine clearance during pregnancy and after delivery in PWWE and the only study with a comparative NPWWE cohort. Varying degrees of increase in clearance were observed during pregnancy possibly reflective of differences in the inducibility of metabolizing enzymes. A large proportion of pregnant women with a faster rate of lamotrigine clearance change would require more frequent and larger dosage adjustments and closer monitoring than those with a lower or no change in clearance. Further studies are needed to identify the causality of the two groups. Systematic studies with the inclusion of multiple variables including genetic information would aid in determining if particular single‐nucleotide polymorphisms are involved in the regulation and expression of UGT1A4 or induction‐related estrogen receptors. 40 , 41 , 42 Following childbirth, clearance rapidly returns to baseline levels and are indiscernible with NPWWE clearance values. Thus, lamotrigine doses should be tapered to preconception doses within 3 weeks of delivery. Optimizing therapy for lamotrigine using the presented model that is complemented by therapeutic drug monitoring will prevent overdosing and exposing both mother and fetus to high levels of lamotrigine, while reducing breakthrough seizures by preventing underdosing. If validated appropriately, the model could be implemented in a dosing tool to help physicians taper the dose and personalize therapy. The utility of models also encompasses simulations that can be performed to help highlight lamotrigine under‐ versus overdosing scenarios. 36 Lastly, similar models could be applied for characterizing the pharmacokinetics of other ASMs in pregnancy if the underlying assumptions are met to characterize the frontier of newer ASMs that are increasingly being used in pregnancy.

To conclude, our study supports the use of therapeutic drug monitoring of lamotrigine during and after pregnancy as currently, it is not possible to prospectively identify if a pregnant individual will need a dose change or not. Equally important can be monitoring of concentrations after birth as there is a rapid decrease in lamotrigine clearance back to baseline levels, increasing the possibility of toxicity if doses are not changed which would not only affect the mother's health, but her ability to care for her newborn.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AK and YL were involved with the analysis and interpretation of data and drafting/revision of the manuscript content. PBP, KJM, and AKB were involved with study design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting/revision of the manuscript content.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and National Institute of Child Health and Development (grants U01‐NS038455 [Drs Meador and Pennell]), 2U01‐NS038455 [Drs Meador, Pennell], R01‐HD105305 [Drs Birnbaum and Pennell] and University of Minnesota's Doctoral Dissertation Fellowship [Dr Karanam]. The funding organizations did not directly participate in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Ashwin Karanam—Dr. Karanam is currently employed by Pfizer, Inc., although his work on this study was during graduate school at the University of Minnesota. Page B. Pennell—Dr. Pennell has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Karger Foundation; honoraria for grant reviews from Harvard Medical School and the National Institutes of Health; advisory board honorarium from Harvard School of Public Health; speaking honoraria and/or travel reimbursements from the American Epilepsy Society, American Academy of Neurology, and various academic medical centers, and royalties from UpToDate, Inc. Kimford J. Meador—Dr. Meador has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Eisai, and Medtronic Inc. The Epilepsy Study Consortium pays his university for research consultant time related to Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher‐Smith Laboratories, UCB Pharma, and Vivus Pharmaceuticals. In addition, he is Co‐I and Director of Cognitive Core of the Human Epilepsy Project for the Epilepsy Study Consortium and on the editorial boards for Neurology, Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology, Epilepsy and Behavior, and Epilepsy and Behavior Case Reports. Yuhan Long declares no conflicts of interest. Angela K. Birnbaum—Dr. Birnbaum has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, Vireo Health, and UCB Pharma. Dr. Birnbaum is also a co‐inventor of a patent for intravenous carbamazepine (Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals).

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The investigators thank the children and families who have given their time to participate in the MONEAD study. The authors thank all the members of the MONEAD study for their contributions. (These authors were compensated as part of the National Institutes of Health grant that funded this study).

Karanam A, Pennell PB, Meador KJ, Long Y, Birnbaum AK. Characterization of lamotrigine disposition changes during and after pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Pharmacotherapy. 2025;45:33‐42. doi: 10.1002/phar.4640

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hernandez‐Diaz S, Smith CR, Shen A, et al. Comparative safety of antiepileptic drugs during pregnancy. Neurology. 2012;78(21):1692‐1699. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182574f39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, et al. Changes in antiepileptic drug‐prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10‐14. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(6):530‐538. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, et al. Fetal loss and malformations in the MONEAD study of pregnant women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2020;94(14):e1502‐e1511. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell E, Kennedy F, Russell A, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drug monotherapies in pregnancy: updated results from the UK and Ireland epilepsy and pregnancy registers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(9):1029‐1034. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cunnington MC, Weil JG, Messenheimer JA, Ferber S, Yerby M, Tennis P. Final results from 18 years of the international lamotrigine pregnancy registry. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1817‐1823. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pennell PB, Peng L, Newport DJ, et al. Lamotrigine in pregnancy: clearance, therapeutic drug monitoring, and seizure frequency. Neurology. 2008;70(22 Pt 2):2130‐2136. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000289511.20864.2a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence‐based review): obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency: report of the quality standards subcommittee and therapeutics and technology assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73(2):126‐132. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b2f8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Birnbaum AK, Meador KJ, Karanam A, et al. Antiepileptic drug exposure in infants of breastfeeding mothers with epilepsy. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(4):441‐450. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.4443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Argikar UA, Remmel RP. Variation in glucuronidation of lamotrigine in human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica. 2009;39(5):355‐363. doi: 10.1080/00498250902745082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Argikar UA, Senekeo‐Effenberger K, Larson EE, Tukey RH, Remmel RP. Studies on induction of lamotrigine metabolism in transgenic UGT1 mice. Xenobiotica. 2009;39(11):826‐835. doi: 10.3109/00498250903188985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rowland A, Elliot DJ, Williams JA, Mackenzie PI, Dickinson RG, Miners JO. In vitro characterization of lamotrigine N2‐glucuronidation and the lamotrigine‐valproic acid interaction. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34(6):1055‐1062. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen H, Yang K, Choi S, Fischer JH, Jeong H. Up‐regulation of UDP‐glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A4 by 17beta‐estradiol: a potential mechanism of increased lamotrigine elimination in pregnancy. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37(9):1841‐1847. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.026609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohman I, Beck O, Vitols S, Tomson T. Plasma concentrations of lamotrigine and its 2‐N‐glucuronide metabolite during pregnancy in women with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(6):1075‐1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Christensen J, Petrenaite V, Atterman J, et al. Oral contraceptives induce lamotrigine metabolism: evidence from a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2007;48(3):484‐489. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ohman I, Vitols S, Tomson T. Lamotrigine in pregnancy: pharmacokinetics during delivery, in the neonate, and during lactation. Epilepsia. 2000;41(6):709‐713. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pennell PB, Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Helmers SL, Montgomery JQ, Henry TR. The impact of pregnancy and childbirth on the metabolism of lamotrigine. Neurology. 2004;62(2):292‐295. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000103286.47129.f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Browning KR, Birnbaum AK, Montgomery JQ, Newman ML, Clements SD. Lamotrigine clearance is increased by estrogen‐containing oral contraceptives. Neurology. 2006;66(5):A73. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Karanam A, Pennell PB, French JA, et al. Lamotrigine clearance increases by 5 weeks gestational age: relationship to estradiol concentrations and gestational age. Ann Neurol. 2018;84(4):556‐563. doi: 10.1002/ana.25321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tran TA, Leppik IE, Blesi K, Sathanandan ST, Remmel R. Lamotrigine clearance during pregnancy. Neurology. 2002;59(2):251‐255. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.2.251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Polepally AR, Pennell PB, Brundage RC, et al. Model‐based lamotrigine clearance changes during pregnancy: clinical implication. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2014;1(2):99‐106. doi: 10.1002/acn3.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ohman I, Luef G, Tomson T. Effects of pregnancy and contraception on lamotrigine disposition: new insights through analysis of lamotrigine metabolites. Seizure. 2008;17(2):199‐202. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Voinescu PE, Park S, Chen LQ, et al. Antiepileptic drug clearances during pregnancy and clinical implications for women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2018;91(13):e1228‐e1236. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pennell PB. Antiepileptic drug pharmacokinetics during pregnancy and lactation. Neurology. 2003;61(6 Suppl 2):S35‐S42. doi: 10.1212/wnl.61.6_suppl_2.s35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Subramanian M, Birnbaum AK, Remmel RP. High‐speed simultaneous determination of nine antiepileptic drugs using liquid chromatography‐mass spectrometry. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30(3):347‐356. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181678ecb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hussein Z, Posner J. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine monotherapy in patients with epilepsy: retrospective analysis of routine monitoring data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43(5):457‐465. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1997.00594.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mallaysamy S, Johnson MG, Rao PG, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine in Indian epileptic patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(1):43‐52. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1311-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rivas N, Buelga DS, Elger CE, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine with data from therapeutic drug monitoring in German and Spanish patients with epilepsy. Ther Drug Monit. 2008;30(4):483‐489. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e31817fd4d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Punyawudho B, Ramsay RE, Macias FM, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine in elderly patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;48(4):455‐463. doi: 10.1177/0091270007313391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen C. Validation of a population pharmacokinetic model for adjunctive lamotrigine therapy in children. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(2):135‐145. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00237.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grasela TH, Fiedler‐Kelly J, Cox E, Womble GP, Risner ME, Chen C. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine adjunctive therapy in adults with epilepsy. J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;39(4):373‐384. doi: 10.1177/00912709922007949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan V, Morris RG, Ilett KF, Tett SE. Population pharmacokinetics of lamotrigine. Ther Drug Monit. 2001;23(6):630‐635. doi: 10.1097/00007691-200112000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Parke J, Holford NH, Charles BG. A procedure for generating bootstrap samples for the validation of nonlinear mixed‐effects population models. Comput Methods Prog Biomed. 1999;59(1):19‐29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-2607(98)00098-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. R. Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022. https://wwwr‐projectorg/. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pennell PB, Karanam A, Meador KJ, et al. Antiseizure medication concentrations during pregnancy: results from the maternal outcomes and neurodevelopmental effects of antiepileptic drugs (MONEAD) study. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(4):370‐379. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.5487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Barry JM, French JA, Pennell PB, Karanam A, Harden CL, Birnbaum AK. Empiric dosing strategies to predict lamotrigine concentrations during pregnancy. Pharmacotherapy. 2023;43(10):998‐1006. doi: 10.1002/phar.2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Johnson KA. A century of enzyme kinetic analysis, 1913 to 2013. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(17):2753‐2766. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. GlaxoSmithKline . Lamictal Prescribing Information [package insert]. Accessed November 5, 2020 https://www.gsksource.com/pharma/content/dam/GlaxoSmithKline/US/en/Prescribing_Information/Lamictal/pdf/LAMICTAL‐PI‐MG.PDF.

- 39. Weintraub D, Buchsbaum R, Resor SR Jr, Hirsch LJ. Effect of antiepileptic drug comedication on lamotrigine clearance. Arch Neurol. 2005;62(9):1432‐1436. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.9.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mitra‐Ghosh T, Callisto SP, Lamba JK, et al. PharmGKB summary: lamotrigine pathway, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2020;30(4):81‐90. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou J, Argikar UA, Remmel RP. Functional analysis of UGT1A4(P24T) and UGT1A4(L48V) variant enzymes. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12(12):1671‐1679. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lopez M, Dorado P, Monroy N, et al. Pharmacogenetics of the antiepileptic drugs phenytoin and lamotrigine. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2011;26(1):5‐12. doi: 10.1515/DMDI.2011.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.