Abstract

Background

An increase in the prevalence of lung cancer that is not smoking-related has been noticed in recent years. Unfortunately, these patients are not included in low dose computer tomography (LDCT) screening programs and are not actually considered in early diagnosis. Therefore, improved early diagnosis methods are urgently needed for non-smokers. It is necessary to establish a prediction model for non-smoking individuals at intermediate to high risk of developing lung cancer (LC) and develop a tool to address the significant gap in evaluating pulmonary nodules in non-smokers.

Methods

We retrospectively investigated 1121 patients with pulmonary nodules, who underwent LDCT examinations between September 2019 and March 2023. Five artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms were used to build two kinds of models and identify which one was better at diagnosing non-smoking pulmonary nodules patients. In the first model, we assigned 554 non-smoking individuals to a training cohort and 150 non-smoking patients to an independent validation cohort. The second model included 971 patients for the training set and 150 non-smoking patients for an independent validation set. All LDCT images of participants were obtained for AI analysis. AI of LDCT scans, liquid biopsy, and clinical characteristics were collected for model building.

Results

Among LC patients, 58,4% were non-smokers. Non-smoking patients had a high incidence of LC (71.4%), and women showed a significant excess risk compared with non-smoking men in terms of LC risk. Furthermore, our results indicated that the model built using random forest (RF) method, which integrates clinical characteristics (age, extra-thoracic cancer history, gender), radiological characteristics of pulmonary nodules (nodule diameter, nodule count, upper lobe location, malignant sign at the nodule edge, subsolid status), the artificial intelligence analysis of LDCT data, and liquid biopsy achieved the best diagnostic performance in the independent external non-smokers validation cohort (sensitivity 92%, specificity 97%, area under the curve [AUC] = 0.99).

Conclusions

These results could significantly improve early non-smoker LC diagnosis and treatment for non-smoker patients with malignant nodules. The established multi-omics model is a noninvasive prediction tool for non-smoking malignant pulmonary nodule diagnosis. Validation revealed that these models exhibited excellent discrimination and calibration capacities, especially the first model built using the RF method, suggesting their clinical utility in the early screening and diagnosis of non-smoking LC.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-024-13268-5.

Keywords: LC, Non-smoker, Artificial intelligence, Liquid biopsy, Prediction model, Early diagnosis

Background

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death, globally accounting for 1.80 million deaths in 2020 [1]. The fact that most patients with lung cancer (LC) present at the hospital with an advanced disease highlight the importance of a comprehensive understanding of the adverse consequences of the disease and screening and diagnosis. The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) evaluated the benefits of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) for screening of smokers, finding that annual screening by LDCT reduces the risk of mortality by 20% compared to chest radiography [2]. Standard criteria for LC screening or early diagnosis models in high-risk groups are based on age and smoking history [3–5]. Nevertheless, the increase in LC among Asians cannot be entirely attributed to smoking, especially among women.

An increase in the prevalence of LC that is not smoking-related has been noticed in Asian countries such as China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan in recent years [6, 7]. In Asia, the smoking rate among female LC patients is < 20%, while in Europe and the United States, it reaches 70–85% [8]. Non-smoking LC accounts for most Asian female LCs, and the incidence of LC in non-smoking men was two-fold that of non-smoking women in some parts of Asia [9]. Therefore, non-smoking Asian men and women should be given more attention. Unfortunately, these patients are not included in LDCT screening programs and are not actually considered in early diagnosis. Accordingly, establishing an early diagnosis model for non-smoking patients is paramount.

Liquid biopsy is a new method for the early diagnosis of cancer characterized by novel, sensitive, and specific biomarkers. Liquid biopsy for early LC detection has been extensively investigated in previous studies [10, 11], which used a fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) liquid biopsy approach to detect cells with cytogenetic abnormalities and to rule out LC in individuals with intermediate pulmonary nodules [12, 13]. In addition, artificial intelligence (AI) approaches have received increasing attention for image analysis in the clinical setting. AI can help clinicians improve the diagnostic efficacy and accuracy of LC screening [14, 15] and distinguish malignant and benign nodules by recognizing specific malignant features from LDCT images [16, 17]. It can also be used to analyze the whole pulmonary nodule and identify features characteristic of invasion [14, 18, 19]. For example, some AI models performed equally or even more accurately than skilled clinicians in identifying benign from malignant pulmonary nodules [20]. Also, AI models can enhance diagnostic accuracy and reduce the risk of human errors caused by classifying a large number of medical images [14, 16].

The integration of clinical and radiological characteristics, together with AI interpretation of LDCT images and liquid biopsy testing for cells with cytogenetic abnormalities via a 4-color FISH array, could improve the ability to establish early diagnosis of LC in individuals with intermediate and high-risk pulmonary nodules on LDCT [12]. Consequently, this study aimed to investigate an early LC diagnosis model for non-smokers incorporating artificial intelligence, liquid biopsy, and clinical and radiological characteristics to improve the diagnosis of pulmonary nodules with an intermediate and high risk of LC detected by LDCT.

Methods

Study population

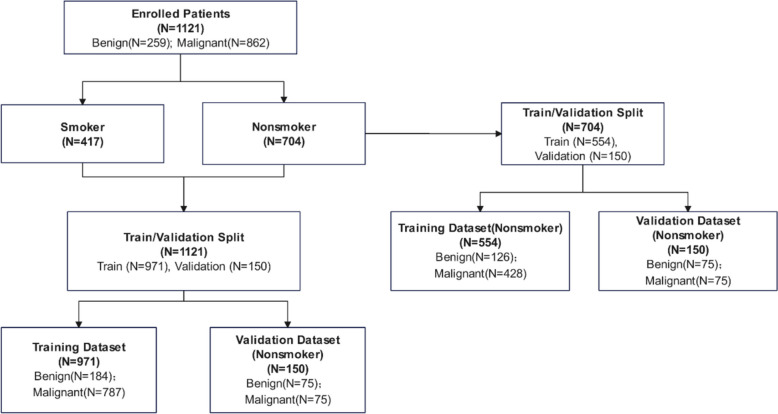

A total of 1121 (487 males and 634 females) pulmonary nodules individuals were retrospectively analyzed. Pulmonary nodules screened by LDCT were identified as intermediate and high-risk for LC by physicians in the usual care routine. The clinician conducted a comprehensive evaluation based on CT imaging analysis, clinical factors and clinical experience. Then these individuals requiring follow-up to rule out malignancy or individuals with a clinical suspicion of LC were defined as at intermediate and high risk. According to coding guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and others, non-smokers were defined as patients who had smoked less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime [21]. A flow diagram describing the subjects is shown in Fig. 1. The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University approved the study for training dataset, and the previously published data provided the external validation set [12].

Fig. 1.

Study design and patients enrollment

Eligible patients recruited were enrolled in the training set to establish early LC prediction models. Subsequently, an independent external validation set composed of non-smoking participants was used to test the diagnostic performance of the comprehensive LC risk prediction model.

Data collection

Clinical information, including age, gender, smoking history, family history of LC was obtained from all participants. Family history included all types of cancers, but the largest number was family history of lung cancer. LDCT images in the 6 months prior to the enrollment of patients were obtained for AI analysis. Moreover, the nodule characteristics such as the solitary, diameter, nodule type, location, and others were collected by LDCT image. Following AI of LDCT scans and liquid biopsy, patients with intermediate and high-risk pulmonary nodules who met the inclusion criteria were subjected to fiberoptic bronchoscopy, fine needle biopsy, and/or surgical resection of their nodules for pathological examination. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification for lung tumors was used to classify lung masses, and staging was based on the 8th edition of the TNM Classification for LC of the International Cancer Control and the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system [22, 23].

AI analysis

An automated diagnostic platform comprising a deep-learning-based AI algorithm with a three-stage end-to-end deep conventional neural network (DCNNs) was developed to analyze the LDCT images of the patients, then detected and located nodules, analyzed and assessed the nodules malignant. The approach to AI analysis has been described in previous studies [12]. Finally, after the images were analyzed, the AI model provided a risk score for developing LC (ranging from 0 to 100%) and a diagnosis statement for each participant.

Liquid biopsy

More and more researchers have recognized the exploration based on copy number variation (CNV) in cancer areas [24, 25]. The circulating genetically abnormal cells (CACs) were detected by peripheral blood 4-color FISH assay developed to generate data for this study [26]. This multiplex interphase FISH assay contained four DNA probes, which are universally amplificated in LC and are closely related to the occurrence and development of LC [13, 26]. This assay, which has previously shown a high degree of accuracy, detected cells containing chromosomal abnormalities at 10q22.3 and 3p22.1 and in the internal control genes CEP 10 and 3q29 [13, 26–28]. Abnormal cells, discovered by the 4-color FISH assay, were identified as intact cells with a nucleus larger than a lymphocyte nucleus and polysomy of at least two probes per nucleus. The FISH assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described [13].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses of the variables are expressed as means, median values, ranges, or numbers expressed as percentages (%). Statistical analysis was performed using Python version 3.8.5 (Python Software Foundation, USA) and MedCalc version 19.0.4 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium). All tests were nonparametric, and p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance. After feature selection, five machine-learning models were employed for model construction. Light gradient boosting (LGB) adopts a leaf-wise growth strategy to construct the tree and gradient-based one-side sampling (GOSS) to find a split [29]. A random forest (RF) model builds decision trees that make predictions based on binary decisions about the input features [30]. A support vector machine (SVM) learns a line (or hyperplane in many dimensions) in feature space that separates two classes of data points with the largest [31]. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) performs variable selection and regulation to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the statistical model it produces [32]. The LR model is used to study the impact of trait variables on the target variable, which is usually a binary classifier [33]. Finally, the performance of each model was validated and compared in the validation set. In our cases, receiver operating curves (ROCs) were used to determine the individual performance of different models.

Results

Patient characteristics

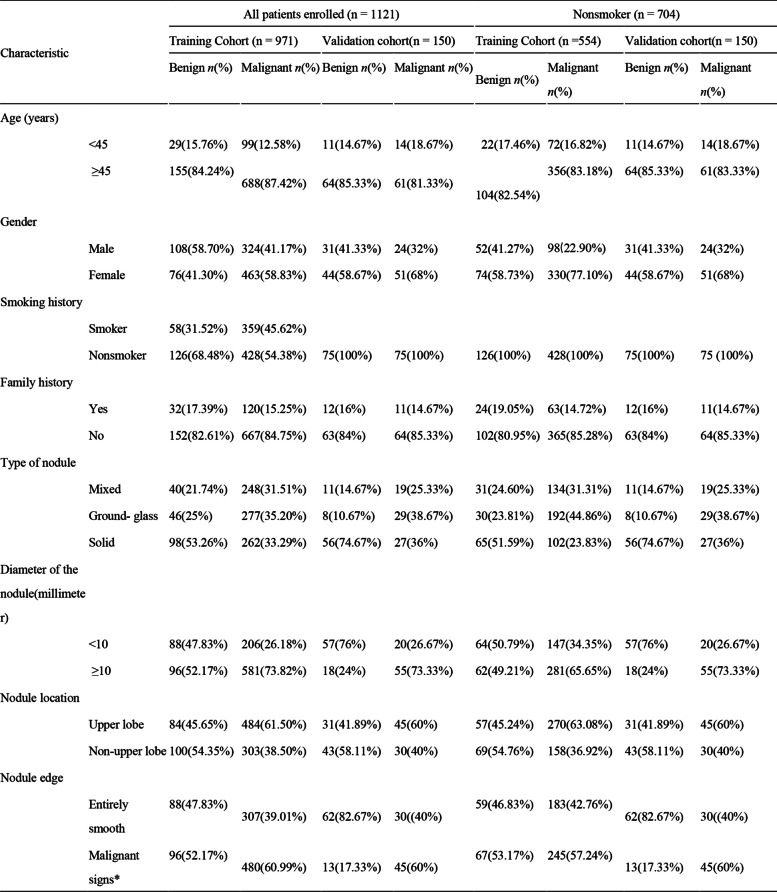

A total of 1121 patients were enrolled. The clinical characteristics of the patients in the training and validation cohorts are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the 1121 patients with pulmonary nodules in the training cohort and validation cohort

*Signs of malignancy indicate nodules with one or more of the following: lobulation, spiculation, vacuole sign, pleural indentation, vessel convergence sign, or other radiological signs of malignancy

The analyzed 1121 (487 males (43.4%) and 634 females (56.6%)) patients who underwent LDCT and were found with pulmonary nodules are shown in Table 1. A total of 13.6% (153/1121) of participants were aged < 45 years old, and 86.4% (968/1121) were ≥ 45 years old. Smoking patients accounted for 37.2% (417/1121) of the study population, and 62.8% (704/1121) were non-smokers. The most common type of nodules were solid nodules (39.5%, 443/1121), followed by ground-glass nodules (32.1%, 360/1121) and mixed nodules (28.4%, 318/1121). The diameter of nodules ≥ 10 mm accounted for 66.9% (750/1121), and 33.1% were < 10 mm (371/1121). There were 57.4% (644/1121) nodules in the upper lobe and 42.5% in other places (476/1121). More than half of the nodules (56.6%, 634/1121) showed signs of malignancy, such as lobulation, spiculation, vacuole sign, pleural indentation, vessel convergence sign, or other radiological signs of malignancy.

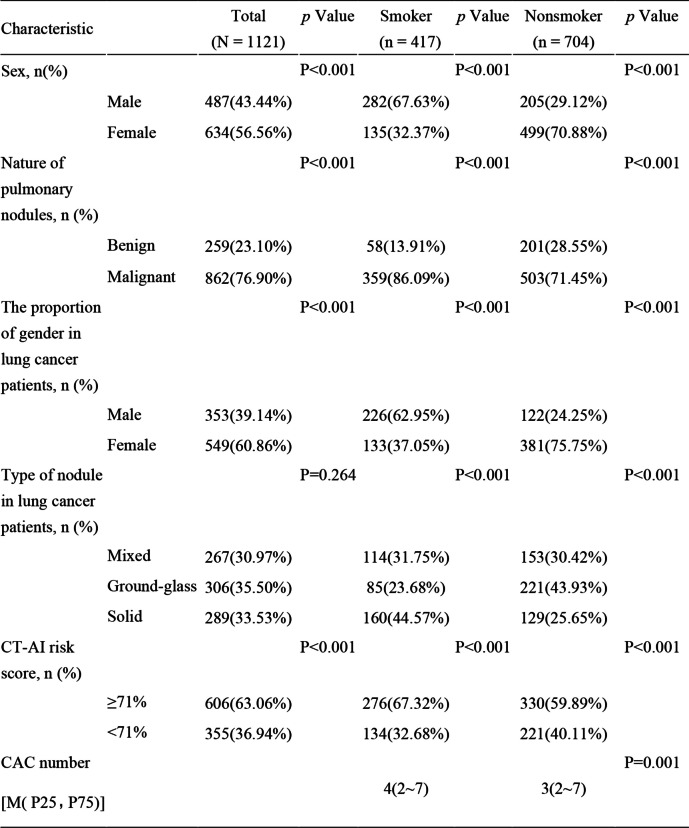

Clinical, liquid biopsy, and AI characteristics of smokers and non-smokers

Women accounted for 56.56% of the overall participants and were dominant in the non-smoker group, which was significantly larger than the male group (70.88% (499/704) vs. 29.12% (205/704)). The LC detection rate was 76.9%, which was higher in women than in men (Table 2). The malignant nodule rate in smokers was 86.09%, which was significantly higher than the benign nodule rate. In particular, this phenomenon was also observed in non-smokers, whose malignant nodule rate was 71.45% (Table 2). In LC patients, men accounted for the vast majority of smokers (male 62.95% vs. female 37.05%), while women made up the overwhelming majority of nonsmokers (female 75.75% vs. male 24.25%) (Table 2). Among LC patients, the most common type of nodule in nonsmokers was ground-grass nodules (43.93%) (Table 2). Whether smokers or non-smokers, the high CT-AI risk score (≥ 71%) proportion was relatively larger than that of less 71% (in smokers, 67.32% vs. 32.68%; in non-smokers, 59.89% vs. 40.11%). The number of CAC was significantly different between smokers and non-smokers in both women and men.

Table 2.

Characteristics of LDCT-screened patients between smokers and non-smokers

Abbreviations: CAC Circulating Genetically Abnormal Cells, CT-AI The risk score for developing lung cancer (ranging from 0 to 100%) using an automated diagnostic platform comprising a deep-learning based Artificial intelligence (AI) approaches with a three-stage end-to-end deep conventional neural network (DCNNs) to analyze the LDCT images

*Signs of malignancy indicate nodules with one or more of the following: lobulation, spiculation, vacuole sign, pleural indentation, vessel convergence sign, or other radiological signs of malignancy

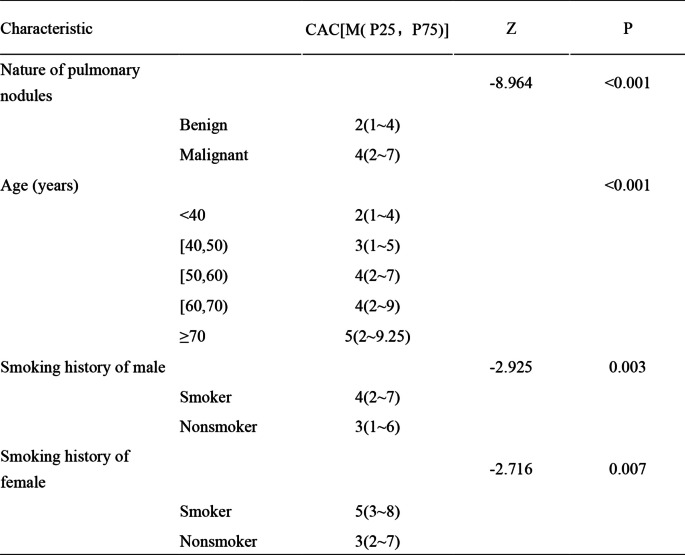

Compared with patients with benign pulmonary nodules, patients in the malignant cohort had significantly greater CACs (p < 0.001) (Table 3). The median (interquartile range) CAC count was 4 (2–7) for smokers compared with 3 (2–7) for non-smokers (Table 2), which was significantly different, and similar trends were found in male and female patients respectively (Table 3). With the increase in age, the CAC count showed an increasing trend (Table 3).

Table 3.

CAC characteristics in all participants

Abbreviations: CAC Circulating Genetically Abnormal Cells

Liquid biopsy and CT-AI characteristics of non-smokers

In the non-smoker group, CAC count had a significant increase between benign and malignant nodules (media 2 (1–4) in benign nodules vs. media 4 (2–7) in malignant nodules), and a similar trend was observed in male and female patients (Table 3, SFigure 1A and B). Among different ages, CAC count generally showed a significant increasing trend with the increase in age in all the non-smokers and female non-smokers (SFigure 1C and D), while there was no noticeable change in the male non-smokers (SFigure 1F and G).

In the non-smoker group, CT-AI classification of risk score significantly increased between benign and malignant nodules and a similar trend was found in male and female patients (SFigures 2A and B). There was no significant difference in the probability of CT-AI classification of risk scores in different age ranges and among non-smokers with or without a family history of cancer (SFigure 2C and G).

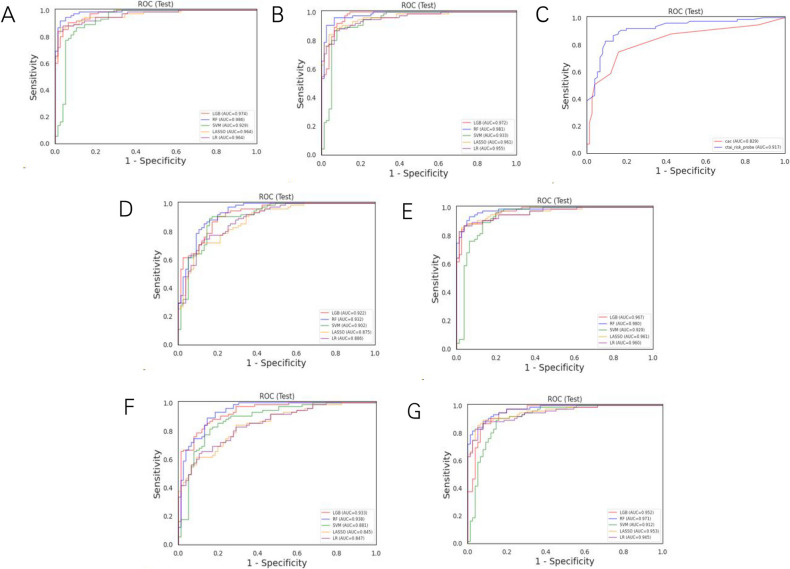

Multivariate logistic regression analysis to build early LC prediction models

Five AI algorithms, namely Support Vector Machine (SVM), Logistic Regression (LR), Light Gradient Boosting (LGB), Random Forest (RF) classifier, and the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO), were used to set the early diagnosis model of LC in non-smoking patients. Under each model-building method, two types of model data categories were established, and each data type contained three sets of predicting features (STable 1). The highest diagnostic performance was found in type 1-A model (the training cohort and the validation external cohort were all non-smokers), which comprised clinical characteristics, radiological characteristics (diameter, nodule count, subsolid status, upper lobe location, and malignant signs at the nodule edge), AI risk score, and liquid biopsy results, with sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of 92% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8586, 0.9814), 97% (95% CI: 0.9369, 1.0098), and 0.99 (95% CI: 0.9731, 0.9999), respectively, using Random Forest (RF) method (STable 1, Fig. 2A). In type 1-B, when predictors were also consistent with clinical characteristics, radiological characteristics, and liquid biopsy results, with the deletion of AI risk score, there was a decrease in the AUC to 0.93 (95% CI: 0.8935, 0.971) (Fig. 2D). In type 1-C, we deleted the liquid biopsy results and kept the other features, and the AUC fell to 0.98 (95% CI: 0.9625, 0.997) (Fig. 2E). In type 2, the model with the highest diagnostic performance was the one that combined clinical characteristics, radiological characteristics (diameter, nodule count, subsolid status, upper lobe location, and malignant signs at the nodule edge), AI risk score, and liquid biopsy results using RF classifier, whose AUC was 0.98 (STable 1, Fig. 2B). In type 2-B, when deleting the AI risk score feature, the AUC dropped to 0.94 (Fig. 2F), while in type 2-C, the AUC sharply dropped to 0.97 when removing the liquid biopsy results feature (Fig. 2G). In Fig. 2C, we evaluated the diagnostic ability of the AI risk score and liquid biopsy results to discriminate between benign and malignant nodules in non-smokers. According to the Youden index, AI risk performed best when the threshold value was set to > 71% (Fig. 2C). This threshold was associated with a sensitivity of 87% (95% CI: 0.7897, 0.9436), a specificity of 87% (95% CI: 0.7897, 0.9436) and AUC of 0.92 (95% CI: 0.8713, 0.9632). Similarly, when the cutoff value for the number of abnormal cells was set to ≥ 3, the sensitivity and specificity were 75% (95% CI: 0.6482, 0.8451) and 84% (95% CI: 0.757, 0.923), respectively. Based on the ROC curves of both tools, the AUC was 0.92 (95% CI: 0.8713, 0.9632) for the AI risk score and 0.83 (95% CI: 0.7619, 0.879) for liquid biopsy in the non-smoking cohort (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

A The AUC of the type 1-A model. B The AUC of type 2-A model. C The AUC of liquid biopsy was 0.83, and the AUC of AI was 0.92 in the non-smoker cohort. D, E The areas under the curve for type 1-B model (D) and 1-C (E). F, G The area AUC for model 2-B (F) and 2-C (G)

Discussion

In the present study, clinical and radiological characteristics, together with the AI risk score of LDCT image analysis and quantitation of abnormal cells detected via a 4-color FISH-based liquid biopsy assay, were used to build an early LC prediction model and diagnose malignant pulmonary nodules in individuals having LDCT images of non-smoking patients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that combined AI for LDCT image analysis and liquid biopsy to build prediction models and diagnose malignant pulmonary nodules in non-smoking individuals in the Chinese cohort.

Our results showed that 76.9% of patients with nodules detected by the LDCT test suffered from LC. Of these 862 patients with LC, 58.4% (503/862) were non-smokers (Table 2). These data were significantly higher than the reported 12.5% of never-smokers with LC in 7 US States [34]. The ratio of female non-smoking LC was 75.75%, which was higher than male LC patients (24.25%) (Table 2) and was consistent with past literature [7, 34]. This indicates that non-smoking patients had a high incidence of LC, and women showed a significant excess risk compared with non-smoking men in terms of LC risk. Accordingly, non-smoking patients who, unfortunately are often overlooked, especially women, should be given more attention in early diagnosis of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules.

The results of the present study supported that a high prevalence of ground glass nodules (GGN) type commonly occurred in non-smokers, and patients with adenocarcinoma had a higher proportion of non-smoking patients (Table 2), which is consistent with previous literature [7, 34–40]. Pulmonary GGN is becoming an important clinical dilemma in oncology as their diagnosis in clinical practice has been increasing [41]. GGN on computed tomography (CT) manifests as hazy lesions, and these manifestations encompass both malignant and benign lesions, such as focal interstitial fibrosis, inflammation, or hemorrhage [42]. However, slowly growing or stable GGNs are still considered early LCs, preinvasive lesions, atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (AAH), or adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS). Consequently, it would be useful to be able to predict the malignant lesions and choose the right criteria for surgery.

CAC test showed a significant difference between benign and malignant nodules in non-smokers, which proved to be an effective auxiliary diagnostic index. In non-smoking female patients, the CAC numbers differed among each age period, especially in those older than 40 years (SFigure 1E). Age is a significant risk factor for LC, and the age criteria for LC screening also tend to vary. The age range for screening was 40–80 years [43] among different trials or screening guidelines [44–47]. Our CAC results suggest that in the early screening of LC, the screening scope should be refined and stratified according to gender to achieve early refined screening of LC.

Family history has been shown to have a role in predisposing individuals to LC [48, 49]. In their study, Yin et.al. pointed out that when making stratification by smoking status among Chinese women in Singapore, the association between family history of LC and the LC risk was evident among never-smokers [50]. The current study showed no significant difference between the CAC count and LC risk in non-smoking patients with or without a family history (SFigure 1F and 1G). The inconsistent conclusions may be due to the different groups that were analyzed and the complexity of signatures in the non-smoking population [51], which should be further investigated in the future.

We evaluated the diagnostic ability of the liquid biopsy results and AI risk score to discriminate between benign and malignant nodules in non-smokers. The diagnostic efficiency of CT-AI was higher than that of CAC. The downward trend of AUC after removing CT-AI was more obvious than that after removing CAC. Regardless of the model type, CT-AI contributed significantly more to the non-smoker diagnosis model than CAC. However, both CAC and CT-AI showed to be better methods for the early diagnosis of non-smokers, having the potential to reduce harmful side effects such as pneumothorax and bleeding caused by invasive biopsy. When these results were combined with multiple predictors, namely clinical characteristics, and radiological characteristics, they could attain the highest diagnostic value (Fig. 2A and B). These findings prove that using a classifier with a broad range of validated predictors may improve the diagnostic accuracy for non-smokers early LC.

The present study has some notable points and limitations. First, we could not obtain a pathological diagnosis for those whose nodules were benign and who did not choose to have surgery or biopsy. We choose a balanced test set to ensure the robustness of test performance results. Second, our study cohort was small compared to some screening studies. However, this is a diagnostic study in the non-smoking population, which included individuals with positive LDCT results evaluated as intermediate and high-risk for LC by physicians in the usual care routine.

In the future, we hope to apply these models in a prospective study with a large sample size to further validate and refine our classifiers and improve early non-smoking LC diagnosis. The non-smoking population constitutes a group of people who were easily ignored in the past. Improving the early diagnosis of this population could help improve their LC detection rate. Using these multivariate non-smoking LC prediction models could help non-smoking LC patients obtain individualized care, such as relieving the patients’ anxiety, reducing the follow-up time to less frequent LDCT scans, and reducing the time to a definitive diagnosis to obtain prompt treatment. We believe noninvasive tools such as these classifiers might be good complementary tools for physicians to assess early non-smoking LC.

Conclusions

Among LC patients, 58.4% (503/862) were non-smokers. In non-smokers, the LC incidence rate reached 71.45%. The ratio of female LC was 75.75%, which was apparently higher than in male LC patients (24.25%). Non-smoking patients who were unfortunately often overlooked, especially women, should be given more attention in the early diagnosis of benign and malignant pulmonary nodules. Our results indicate that the model using RF method, which integrates clinical characteristics (age, extra-thoracic cancer history, gender), radiological characteristics of pulmonary nodules (nodule diameter, nodule count, upper lobe location, malignant sign at the nodule edge, subsolid status), the artificial intelligence analysis of LDCT data, and liquid biopsy achieved the best diagnostic performance in the independent external non-smokers validation cohort (n = 150)(sensitivity 92% (95% CI: 0.8586, 0.9814), specificity 97% (95% CI: 0.9369, 1.0098), with area under the curve [AUC] = 0.99. The established multi-omics model is a non-invasive prediction tool for non-smoking malignant pulmonary nodule diagnosis. Moreover, it provides an auxiliary means for the early diagnosis of non-smokers, thus helping to reduce the mortality rate of non-smoking LC patients and improve their survival rates.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: SFigure 1 CAC Characteristics in Non-smokers. (A) CAC count in benign and malignant nodules. (B) CAC count in benign and malignant nodules between male and female patients. (C) CAC count among different age ranges in whole non-smokers. (D, E) CAC count among different age ranges in male non-smokers (D) and female non-smokers (E). (F) CAC count between non-smokers with or without a family history. (G) Malignancy of nodules between non-smokers with or without family history. CAC: Circulating Genetically Abnormal Cells.

Additional file 2: SFigure 2 CT-AI Characteristics in Non-smokers. (A) CT-AI classification of the risk score in benign and malignant nodules. (B) CT-AI classification of the risk score in benign and malignant nodules between male and female patients. (C) CT-AI classification of risk score among different age ranges in whole non-smokers. (D, E) CT-AI classification of risk score among different age ranges in male non-smokers (D) and female non-smokers (E). (F) CT-AI classification of risk score between non-smokers with or without a family history. CT-AI: the risk score for developing lung cancer (ranging from 0 to 100%) using an automated diagnostic platform comprising a deep-learning based Artificial intelligence (AI) approaches with a three-stage end-to-end deep conventional neural network (DCNNs) to analyze the LDCT images.

Additional file 3: STable 1. Early Diagnosis Models of LC with Different Predictors in Non-Smokers.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Bingjie Li for suggestions of the changes. We would like to thank all authors, reviewers, and editors for their critical discussion of this manuscript and apologize to those not mentioned due to space limitations.

Abbreviations

- AAH

Atypical Adenomatous Hyperplasia

- AI

Artificial Intelligence

- AIS

Adenocarcinoma in Situ

- CACs

Circulating Genetically Abnormal Cells

- CNV

Copy Number Variation

- DCNNs

Deep Conventional Neural Network

- FISH

Fluorescent in Situ Hybridization

- GGN

Ground Glass Nodules

- GOSS

Gradient-based One-side Sampling

- LASSO

Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator

- LC

Lung Cancer

- LDCT

Low-dose Computed Tomography

- LGB

Light Gradient Boosting

- LR

Logistic Regression

- NLST

National Lung Screening Trial

- RF

Random Forest

- ROCs

Receiver Operating Curves

- SVM

Support Vector Machine

Authors’ contributions

HL conducted the conception. RN, YJH, and LW designed the research studies. HJC, GRZ, and YLY provided of study materials. XL, YYT, and YLK conducted the statistical analysis. HL revised the manuscript. All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the program for Health Commission of Henan Province (SB201901016). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

To preserve patient confidentiality, the datasets that support the findings of this study are not openly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (Ethics approval number: 2021-KY-0606–001). Due to the retrospective study design, the ethical review board approved a waiver of written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ran Ni, Yongjie Huang and Lei Wang contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clini. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, Fagerstrom RM, Gareen IF, Gatsonis C, Marcus PM, Sicks JD. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, Caughey AB, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Doubeni CA, Kubik M, et al. Screening for lung cancer: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(10):962–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, MacMahon H, Mulshine JL, Munden RF, Salgia R, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144(1):33–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, Kanne JP, Kinsinger LS, Wiener RS, Soo Hoo G, Detterbeck FC. Screening for Lung Cancer: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;153(4):954–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detterbeck FC, Nicholson AG, Franklin WA, Marom EM, Travis WD, Girard N, Arenberg DA, Bolejack V, Donington JS, Mazzone PJ, et al. The IASLC Lung cancer staging project: summary of proposals for revisions of the classification of lung cancers with multiple pulmonary sites of involvement in the forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification. J Thor Oncol. 2016;11(5):639–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Subramanian J, Govindan R. Lung cancer in never smokers: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(5):561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim JU, Han S, Kim HC, Choi CM, Jung CY, Cho DG, Jeon JH, Lee JE, Ahn JS, Kim Y, et al. Characteristics of female lung cancer in Korea: analysis of Korean National Lung Cancer Registry. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(9):4612–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park B, Kim Y, Lee J, Lee N, Jang SH. Sex difference and smoking effect of lung cancer incidence in asian population. Cancers. 2020;13(1):113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perakis S, Speicher MR. Emerging concepts in liquid biopsies. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng H, Wu X, Yin J, Wang S, Li Z, You C. Clinical applications of liquid biopsies for early lung cancer detection. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9(12):2567–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye M, Tong L, Zheng X, Wang H, Zhou H, Zhu X, Zhou C, Zhao P, Wang Y, Wang Q, et al. A Classifier for Improving Early Lung Cancer Diagnosis Incorporating Artificial Intelligence and Liquid Biopsy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:853801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz RL, Zaidi TM, Pujara D, Shanbhag ND, Truong D, Patil S, Mehran RJ, El-Zein RA, Shete SS, Kuban JD. Identification of circulating tumor cells using 4-color fluorescence in situ hybridization: Validation of a noninvasive aid for ruling out lung cancer in patients with low-dose computed tomography-detected lung nodules. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128(8):553–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahuja AS. The impact of artificial intelligence in medicine on the future role of the physician. PeerJ. 2019;7: e7702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oke JL, Pickup LC, Declerck J, Callister ME, Baldwin D, Gustafson J, Peschl H, Ather S, Tsakok M, Exell A, et al. Development and validation of clinical prediction models to risk stratify patients presenting with small pulmonary nodules: a research protocol. Diagnostic and prognostic research. 2018;2:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Espinoza JL, Dong LT. Artificial Intelligence Tools for Refining Lung Cancer Screening. J Clin Med. 2020;9(12):3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ardila D, Kiraly AP, Bharadwaj S, Choi B, Reicher JJ, Peng L, Tse D, Etemadi M, Ye W, Corrado G, et al. End-to-end lung cancer screening with three-dimensional deep learning on low-dose chest computed tomography. Nat Med. 2019;25(6):954–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu KH, Lee TM, Yen MH, Kou SC, Rosen B, Chiang JH, Kohane IS. Reproducible Machine Learning Methods for Lung Cancer Detection Using Computed Tomography Images: Algorithm Development and Validation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e16709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varghese C, Rajagopalan S, Karwoski RA, Bartholmai BJ, Maldonado F, Boland JM, Peikert T. Computed tomography-based score indicative of lung cancer aggression (SILA) predicts the degree of histologic tissue invasion and patient survival in lung adenocarcinoma spectrum. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(8):1419–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Gao M, Xie J, Deng Y, Tu W, Yang H, Liang S, Xu P, Zhang M, Lu Y, et al. Development, validation, and comparison of image-based, clinical feature-based and fusion artificial intelligence diagnostic models in differentiating benign and malignant pulmonary ground-glass nodules. Front Oncol. 2022;12:892890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LoPiccolo J, Gusev A, Christiani DC, Jänne PA. Lung cancer in patients who have never smoked - an emerging disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21(2):121–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholson AG, Tsao MS, Beasley MB, Borczuk AC, Brambilla E, Cooper WA, Dacic S, Jain D, Kerr KM, Lantuejoul S, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of lung tumors: impact of advances since 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2022;17(3):362–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim W, Ridge CA, Nicholson AG, Mirsadraee S. The 8(th) lung cancer TNM classification and clinical staging system: review of the changes and clinical implications. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2018;8(7):709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drews RM, Hernando B, Tarabichi M, Haase K, Lesluyes T, Smith PS, Morrill Gavarró L, Couturier DL, Liu L, Schneider M, et al. A pan-cancer compendium of chromosomal instability. Nature. 2022;606(7916):976–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steele CD, Abbasi A, Islam SMA, Bowes AL, Khandekar A, Haase K, Hames-Fathi S, Ajayi D, Verfaillie A, Dhami P, et al. Signatures of copy number alterations in human cancer. Nature. 2022;606(7916):984–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katz RL, He W, Khanna A, Fernandez RL, Zaidi TM, Krebs M, Caraway NP, Zhang HZ, Jiang F, Spitz MR, et al. Genetically abnormal circulating cells in lung cancer patients: an antigen-independent fluorescence in situ hybridization-based case-control study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(15):3976–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katz RL, Zaidi TM, Fernandez RL, Zhang J, He W, Acosta C, Daniely M, Madi L, Vargas MA, Dong Q, et al. Automated detection of genetic abnormalities combined with cytology in sputum is a sensitive predictor of lung cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21(8):950–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ye M, Zheng X, Ye X, Zhang J, Huang C, Liu Z, Huang M, Fan X, Chen Y, Xiao B, et al. Circulating genetically abnormal cells add non-invasive diagnosis value to discriminate lung cancer in patients with pulmonary nodules ≤10 mm. Front Oncol. 2021;11:638223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li K, Yao S, Zhang Z, Cao B, Wilson CM, Kalos D, Kuan PF, Zhu R, Wang X. Efficient gradient boosting for prognostic biomarker discovery. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2022;38(6):1631–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swanson K, Wu E, Zhang A, Alizadeh AA, Zou J. From patterns to patients: Advances in clinical machine learning for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Cell. 2023;186(8):1772–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noble WS. What is a support vector machine? Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(12):1565–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang J, Choi YJ, Kim IK, Lee HS, Kim H, Baik SH, Kim NK, Lee KY. LASSO-Based machine learning algorithm for prediction of lymph node metastasis in T1 Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53(3):773–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nick TG, Campbell KM. Logistic regression. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ). 2007;404:273–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siegel DA, Fedewa SA, Henley SJ, Pollack LA, Jemal A. Proportion of never smokers among men and women with lung cancer in 7 US States. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):302–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato Y, Fujimoto D, Morimoto T, Uehara K, Nagata K, Sakanoue I, Hamakawa H, Takahashi Y, Imai Y, Tomii K. Natural history and clinical characteristics of multiple pulmonary nodules with ground glass opacity. Respirology (Carlton, Vic). 2017;22(8):1615–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho J, Kim ES, Kim SJ, Lee YJ, Park JS, Cho YJ, Yoon HI, Lee JH, Lee CT. Long-term follow-up of small pulmonary ground-glass nodules stable for 3 years: implications of the proper follow-up period and risk factors for subsequent growth. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(9):1453–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiramatsu M, Inagaki T, Inagaki T, Matsui Y, Satoh Y, Okumura S, Ishikawa Y, Miyaoka E, Nakagawa K. Pulmonary ground-glass opacity (GGO) lesions-large size and a history of lung cancer are risk factors for growth. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3(11):1245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee JH, Park CM, Lee SM, Kim H, McAdams HP, Goo JM. Persistent pulmonary subsolid nodules with solid portions of 5 mm or smaller: Their natural course and predictors of interval growth. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(6):1529–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kakinuma R, Noguchi M, Ashizawa K, Kuriyama K, Maeshima AM, Koizumi N, Kondo T, Matsuguma H, Nitta N, Ohmatsu H, et al. Natural history of pulmonary subsolid nodules: a prospective multicenter study. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(7):1012–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matsuguma H, Mori K, Nakahara R, Suzuki H, Kasai T, Kamiyama Y, Igarashi S, Kodama T, Yokoi K. Characteristics of subsolid pulmonary nodules showing growth during follow-up with CT scanning. Chest. 2013;143(2):436–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Migliore M, Fornito M, Palazzolo M, Criscione A, Gangemi M, Borrata F, Vigneri P, Nardini M, Dunning J. Ground glass opacities management in the lung cancer screening era. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(5):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park CM, Goo JM, Lee HJ, Lee CH, Chun EJ, Im JG. Nodular ground-glass opacity at thin-section CT: histologic correlation and evaluation of change at follow-up. Radiographics. 2007;27(2):391–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.[Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis of early lung cancer (2023 Edition)]. Zhonghua jie he he hu xi za zhi = Zhonghua jiehe he huxi zazhi = Chinese journal of tuberculosis and respiratory diseases 2023, 46(1):1–18. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Toumazis I, Bastani M, Han SS, Plevritis SK. Risk-Based lung cancer screening: a systematic review. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2020;147:154–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Field JK, Duffy SW, Baldwin DR, Brain KE, Devaraj A, Eisen T, Green BA, Holemans JA, Kavanagh T, Kerr KM, et al. The UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial: a pilot randomised controlled trial of low-dose computed tomography screening for the early detection of lung cancer. Health Technol Assess (Winchester, England). 2016;20(40):1–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becker N, Motsch E, Trotter A, Heussel CP, Dienemann H, Schnabel PA, Kauczor HU, Maldonado SG, Miller AB, Kaaks R, et al. Lung cancer mortality reduction by LDCT screening-Results from the randomized German LUSI trial. Int J Cancer. 2020;146(6):1503–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tanner NT, Silvestri GA. Screening for lung cancer using low-dose computed tomography. are we headed for dante’s paradise or inferno?. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(10):1100–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wünsch-Filho V, Boffetta P, Colin D, Moncau JE. Familial cancer aggregation and the risk of lung cancer. Sao Paulo Medical J. 2002;120(2):38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gorlova OY, Weng SF, Zhang Y, Amos CI, Spitz MR. Aggregation of cancer among relatives of never-smoking lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(1):111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin X, Chan CPY, Seow A, Yau WP, Seow WJ. Association between family history and lung cancer risk among Chinese women in Singapore. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen YJ, Roumeliotis TI, Chang YH, Chen CT, Han CL, Lin MH, Chen HW, Chang GC, Chang YL, Wu CT, et al. Proteogenomics of non-smoking lung cancer in East Asia Delineates Molecular Signatures of Pathogenesis and Progression. Cell. 2020;182(1):226-244.e217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: SFigure 1 CAC Characteristics in Non-smokers. (A) CAC count in benign and malignant nodules. (B) CAC count in benign and malignant nodules between male and female patients. (C) CAC count among different age ranges in whole non-smokers. (D, E) CAC count among different age ranges in male non-smokers (D) and female non-smokers (E). (F) CAC count between non-smokers with or without a family history. (G) Malignancy of nodules between non-smokers with or without family history. CAC: Circulating Genetically Abnormal Cells.

Additional file 2: SFigure 2 CT-AI Characteristics in Non-smokers. (A) CT-AI classification of the risk score in benign and malignant nodules. (B) CT-AI classification of the risk score in benign and malignant nodules between male and female patients. (C) CT-AI classification of risk score among different age ranges in whole non-smokers. (D, E) CT-AI classification of risk score among different age ranges in male non-smokers (D) and female non-smokers (E). (F) CT-AI classification of risk score between non-smokers with or without a family history. CT-AI: the risk score for developing lung cancer (ranging from 0 to 100%) using an automated diagnostic platform comprising a deep-learning based Artificial intelligence (AI) approaches with a three-stage end-to-end deep conventional neural network (DCNNs) to analyze the LDCT images.

Additional file 3: STable 1. Early Diagnosis Models of LC with Different Predictors in Non-Smokers.

Data Availability Statement

To preserve patient confidentiality, the datasets that support the findings of this study are not openly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.