Abstract

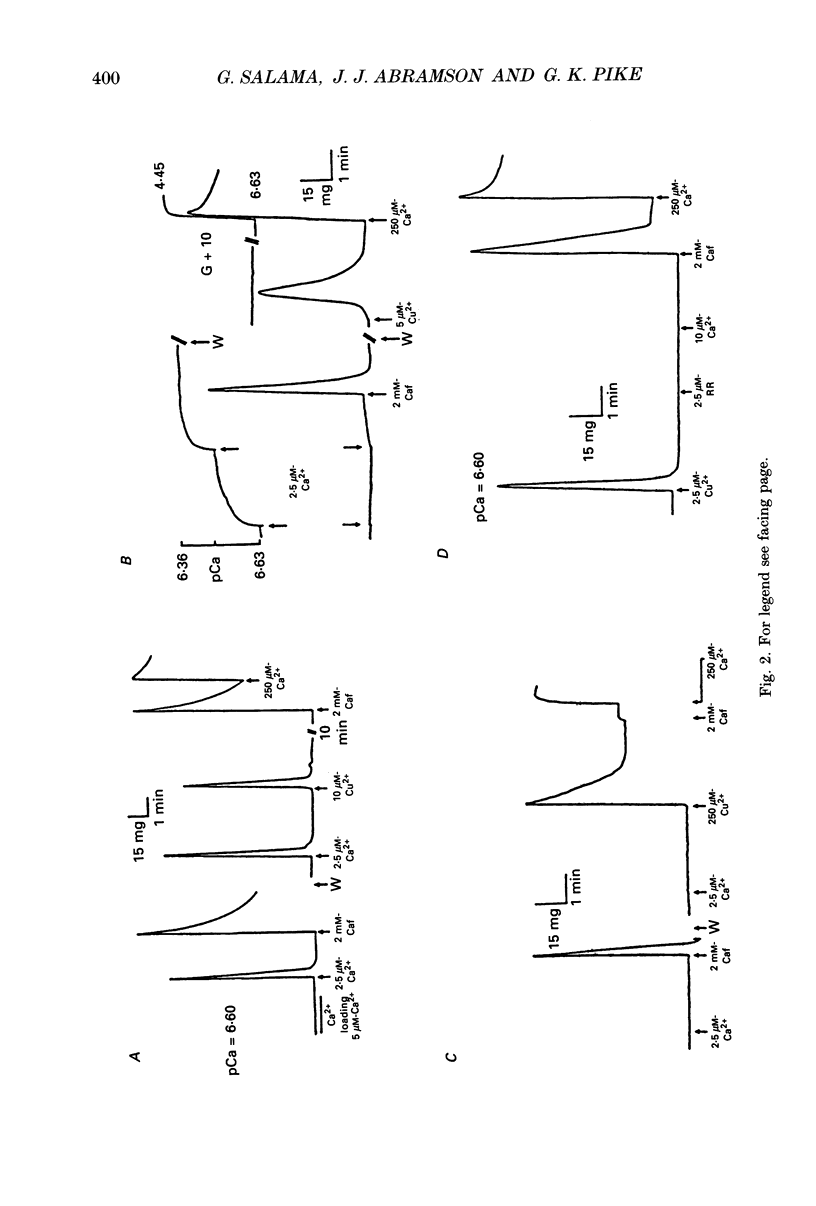

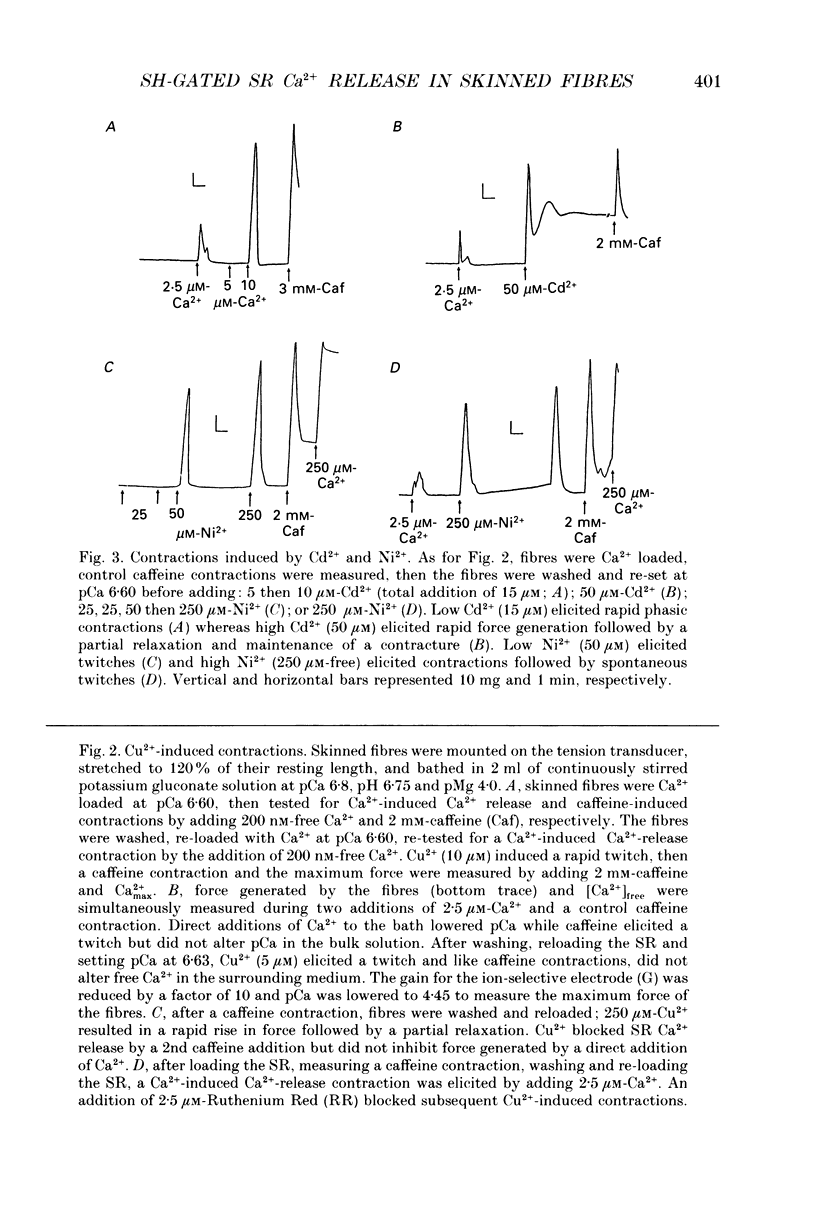

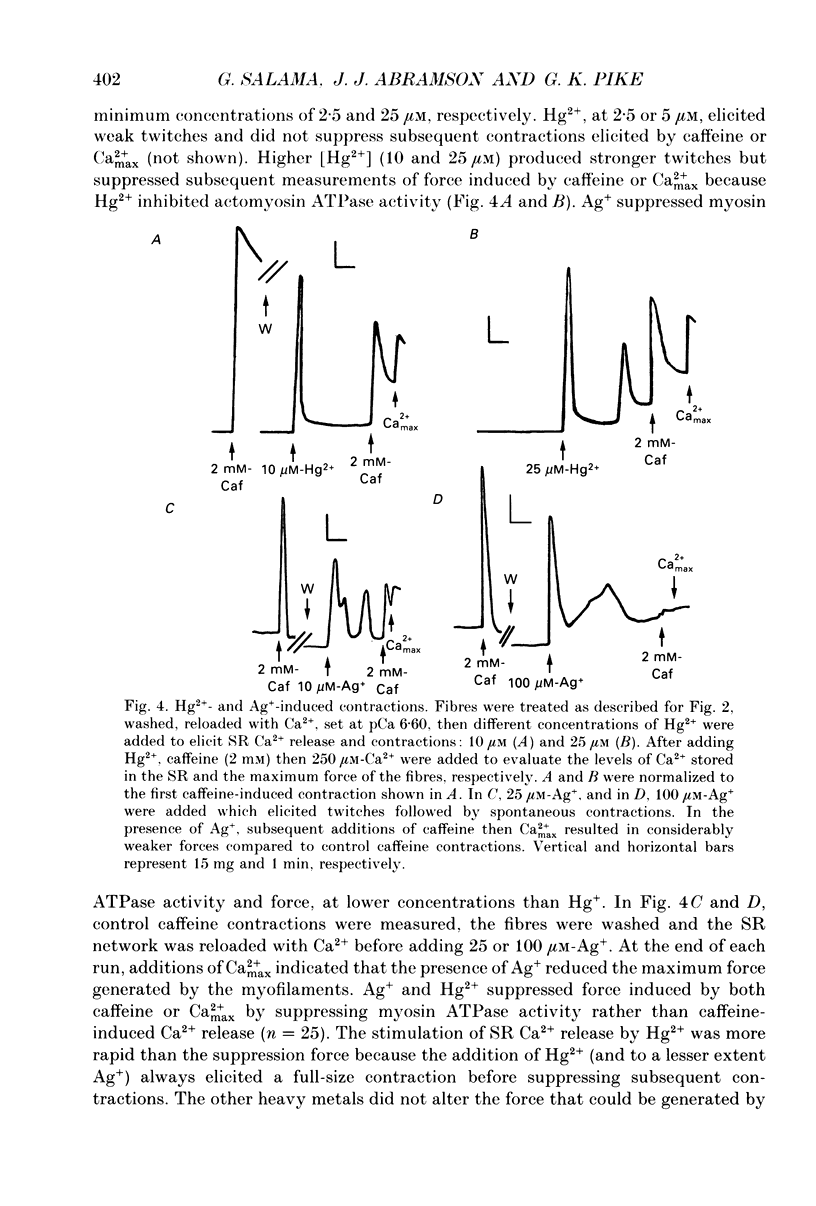

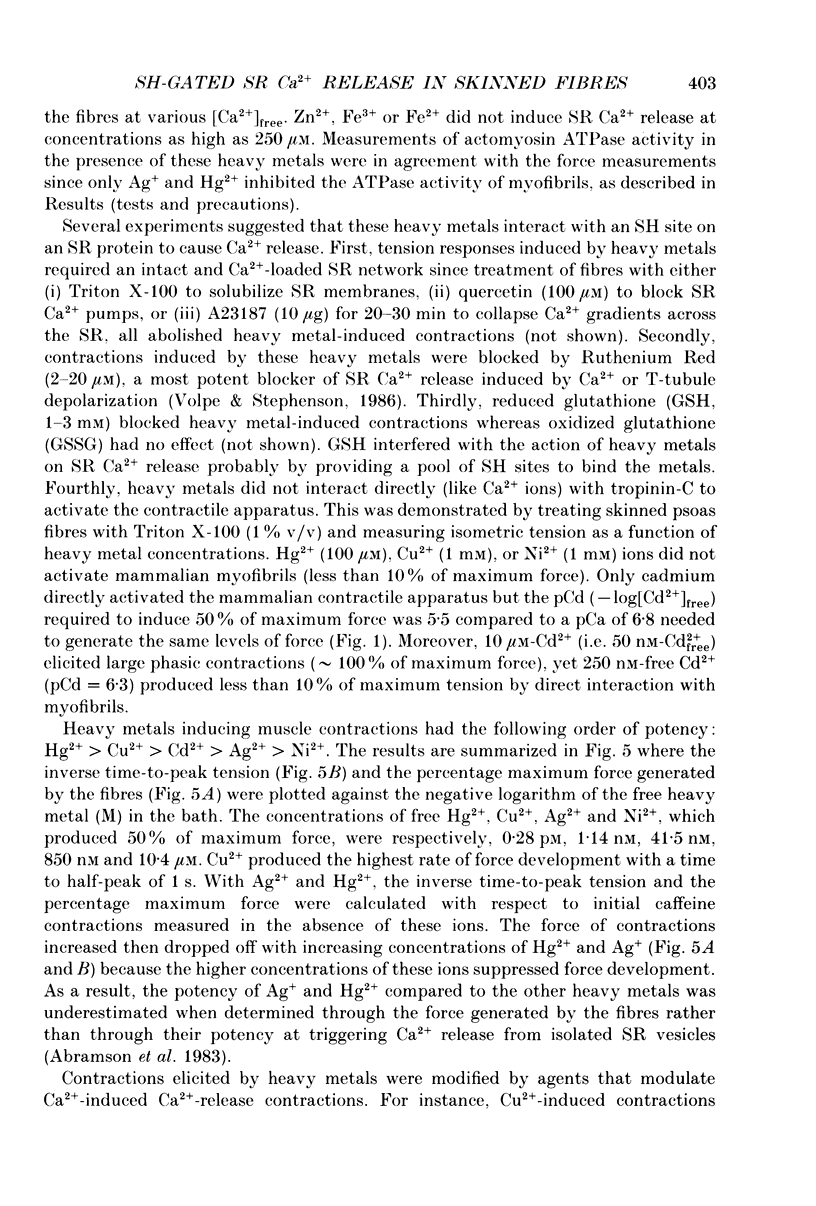

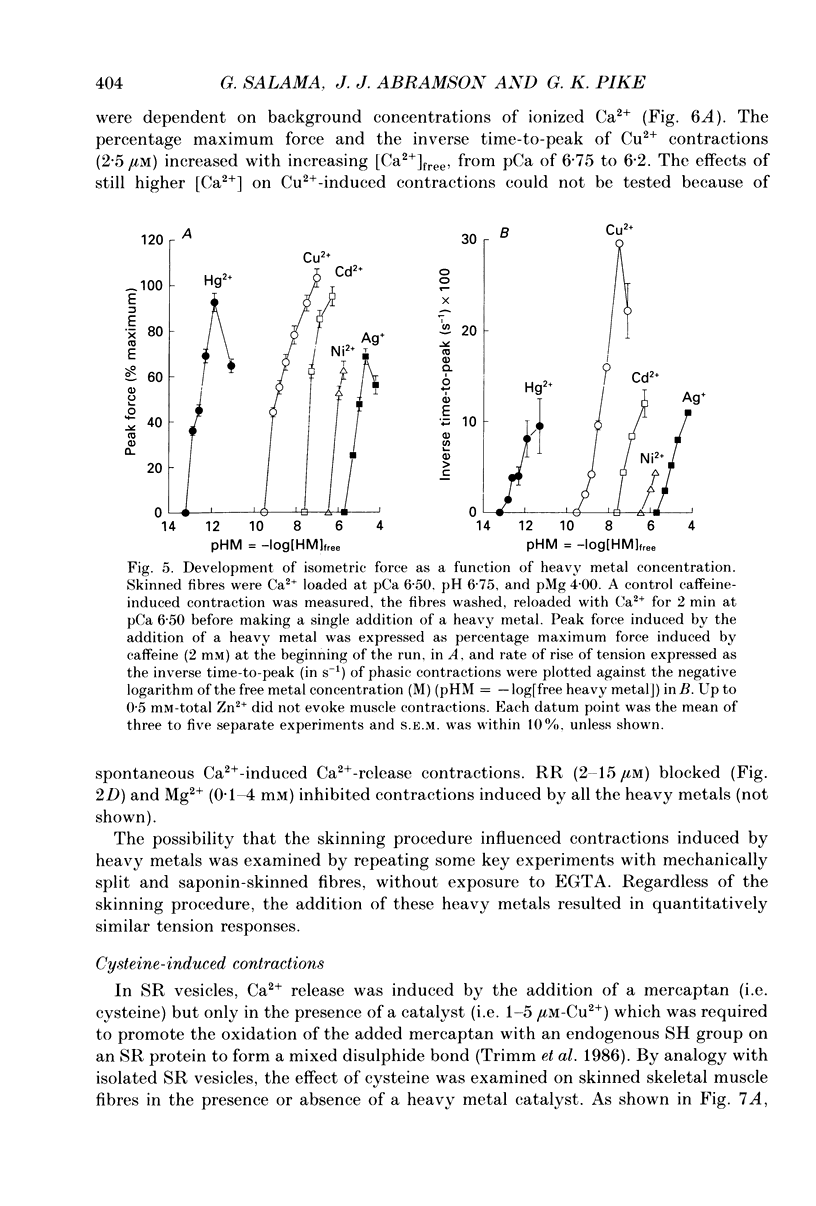

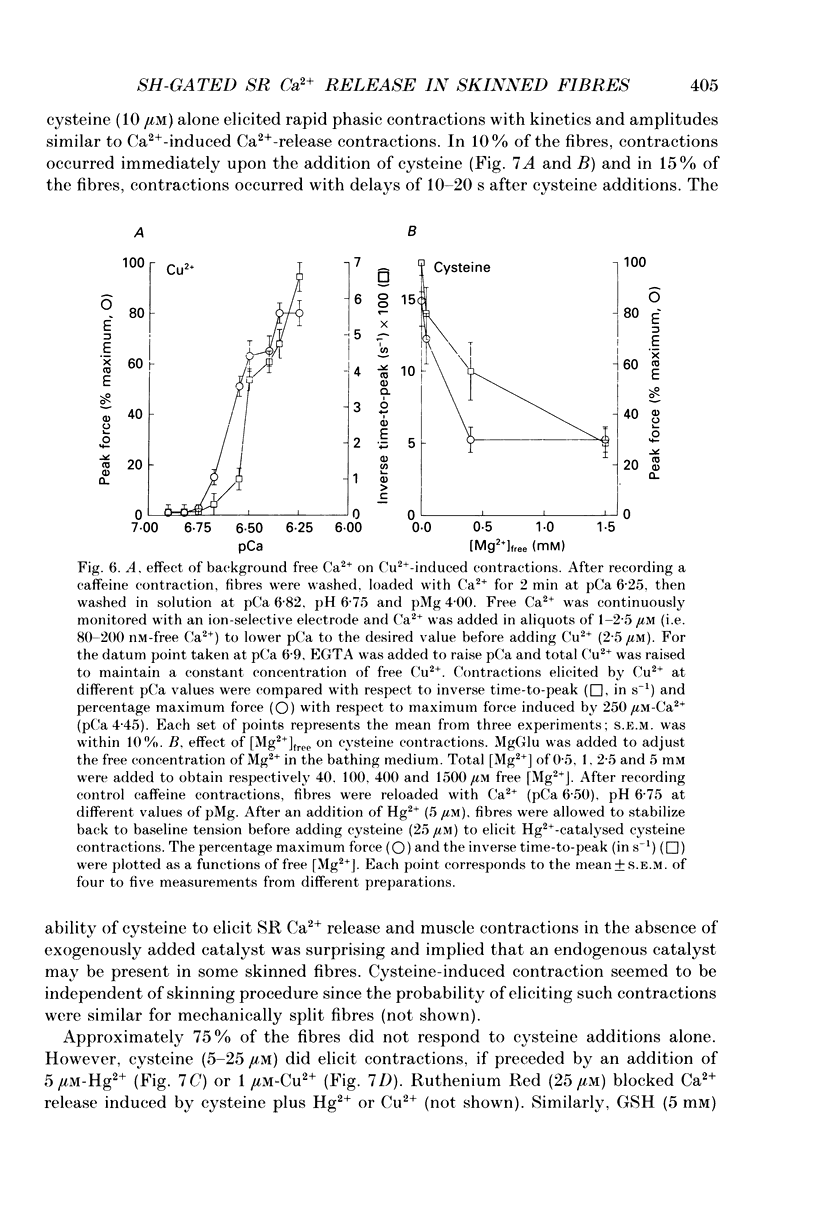

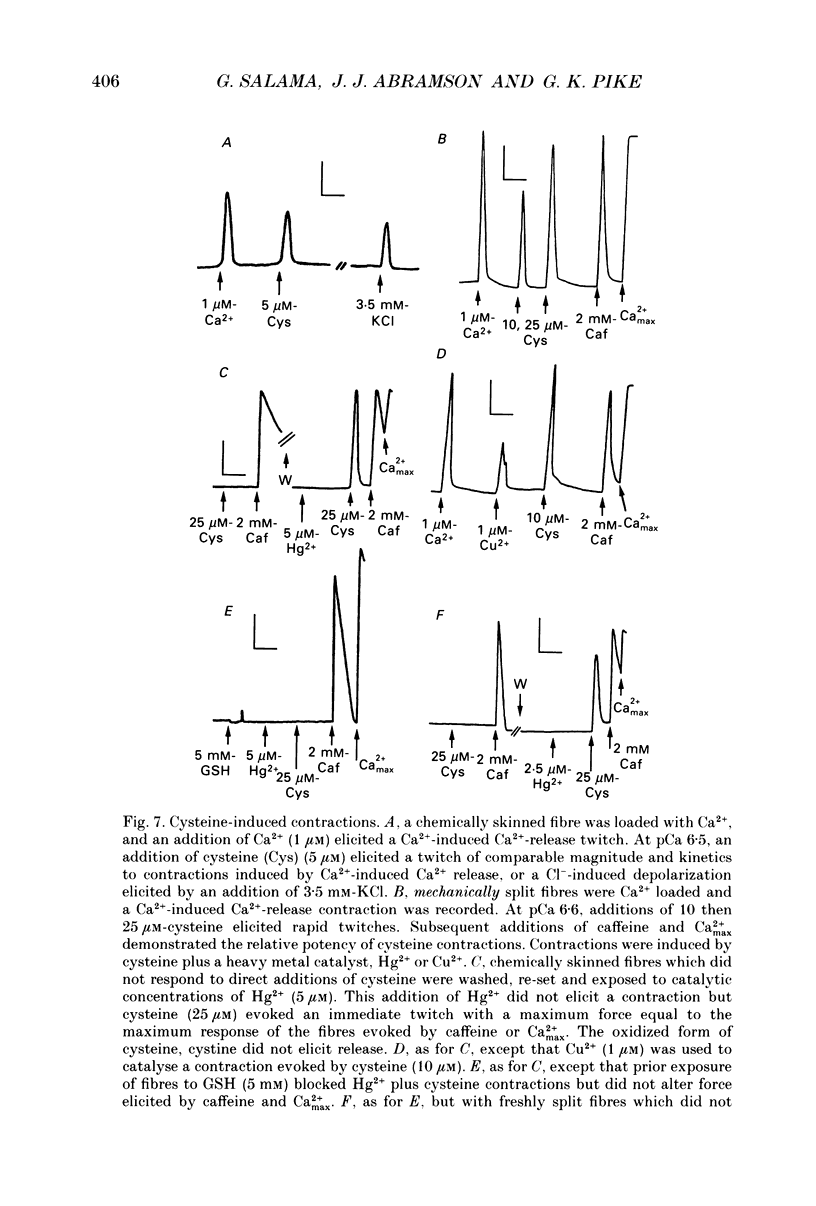

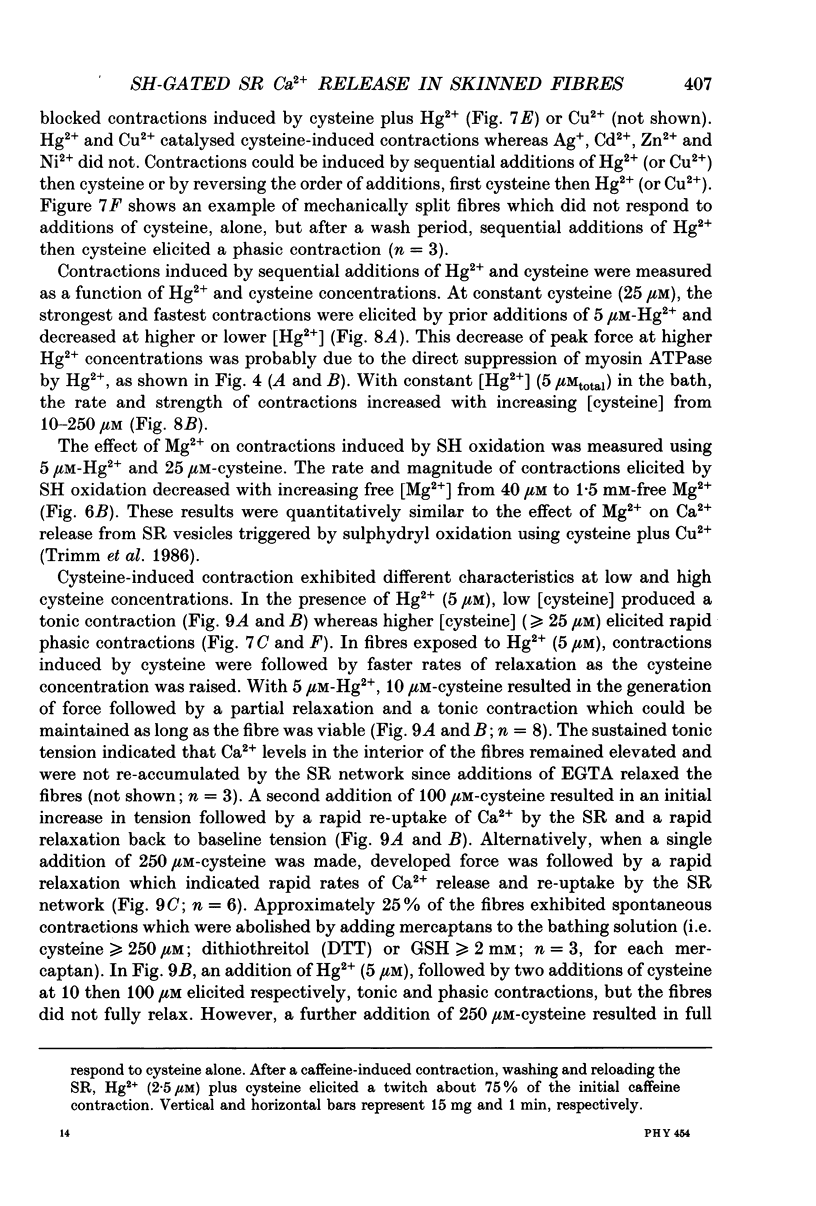

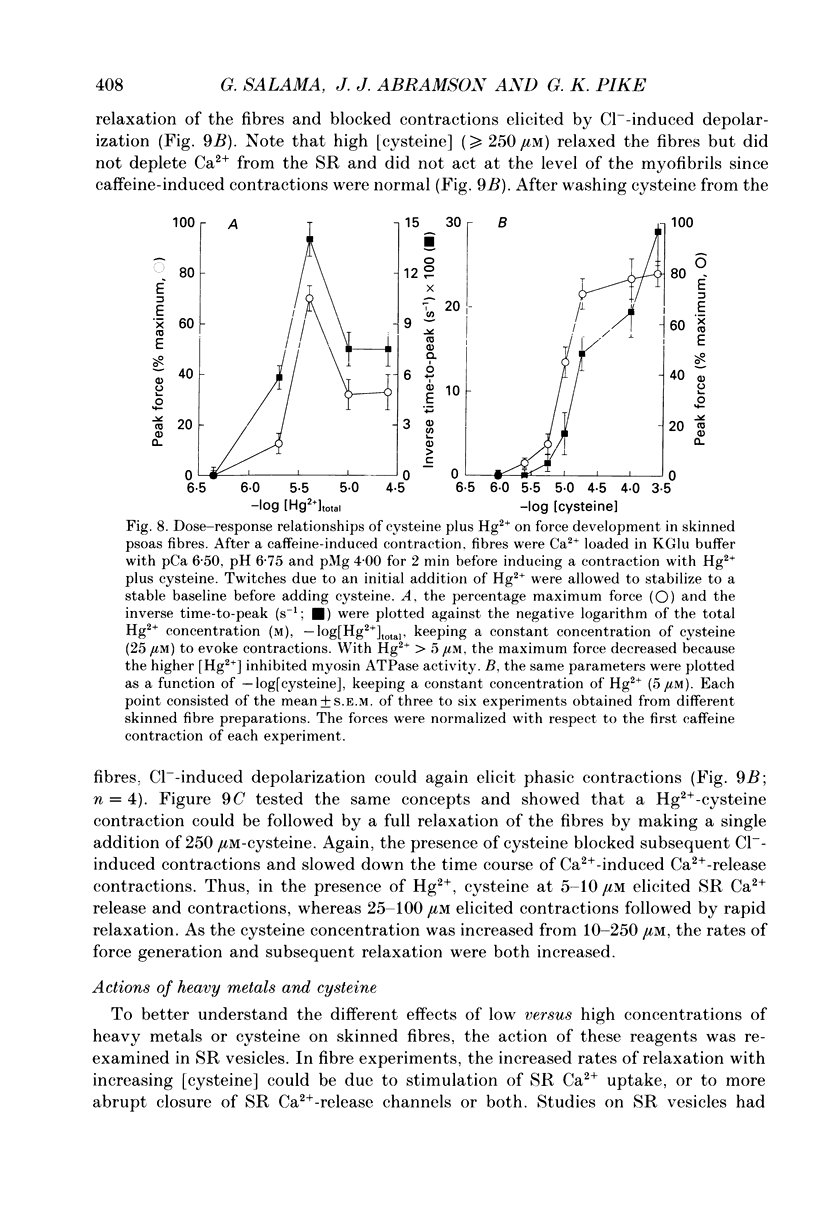

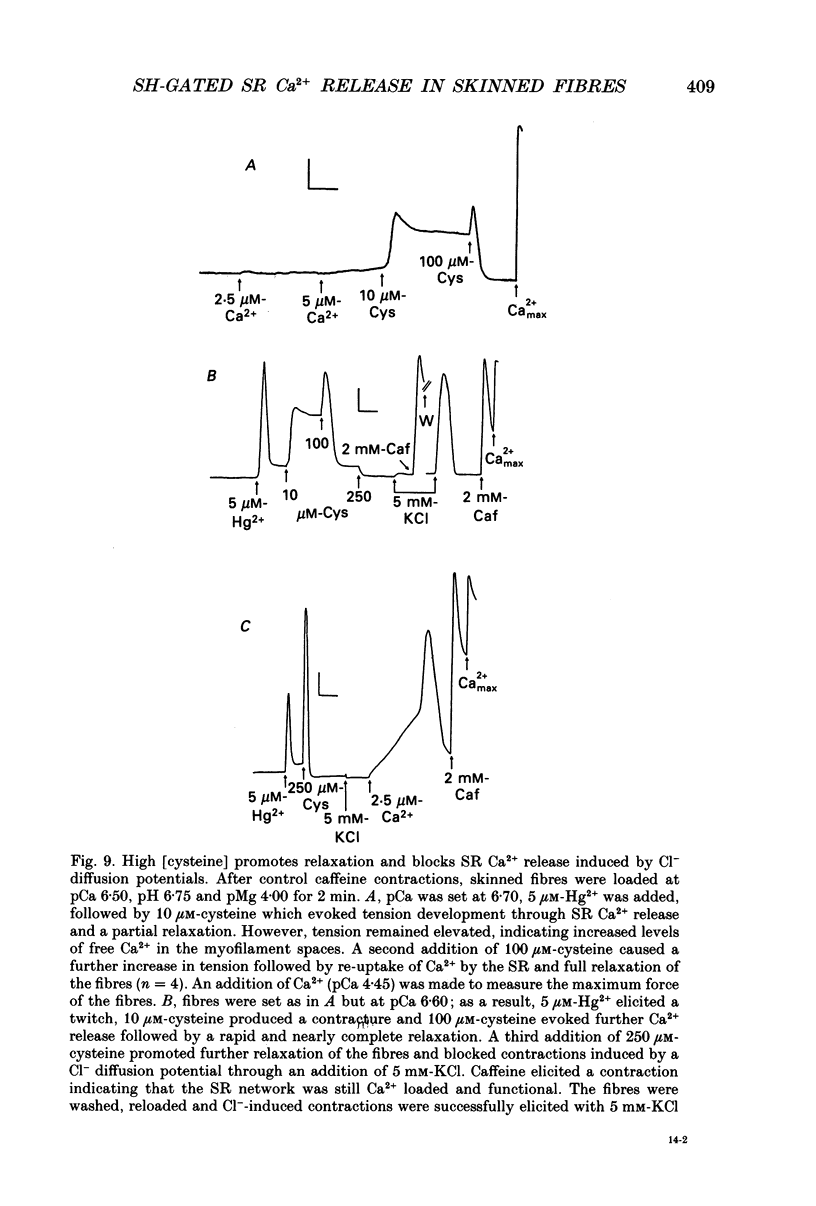

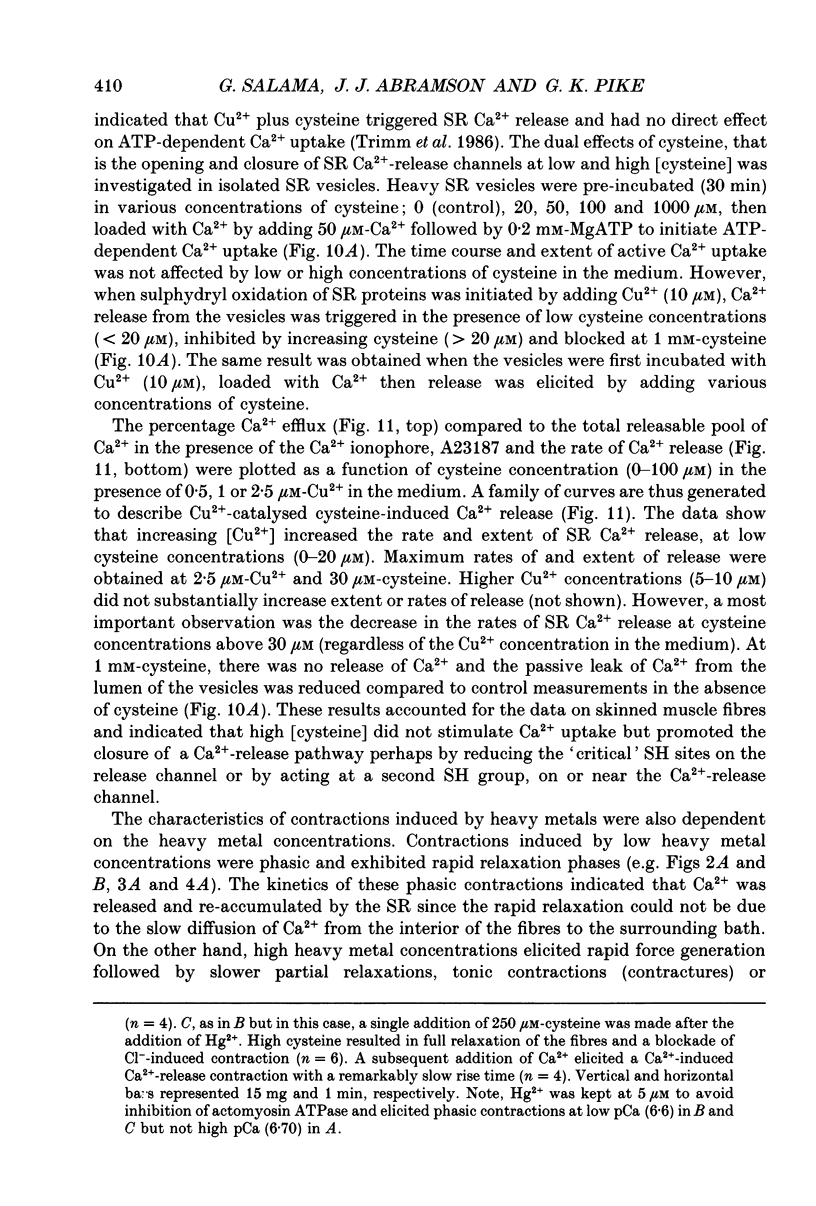

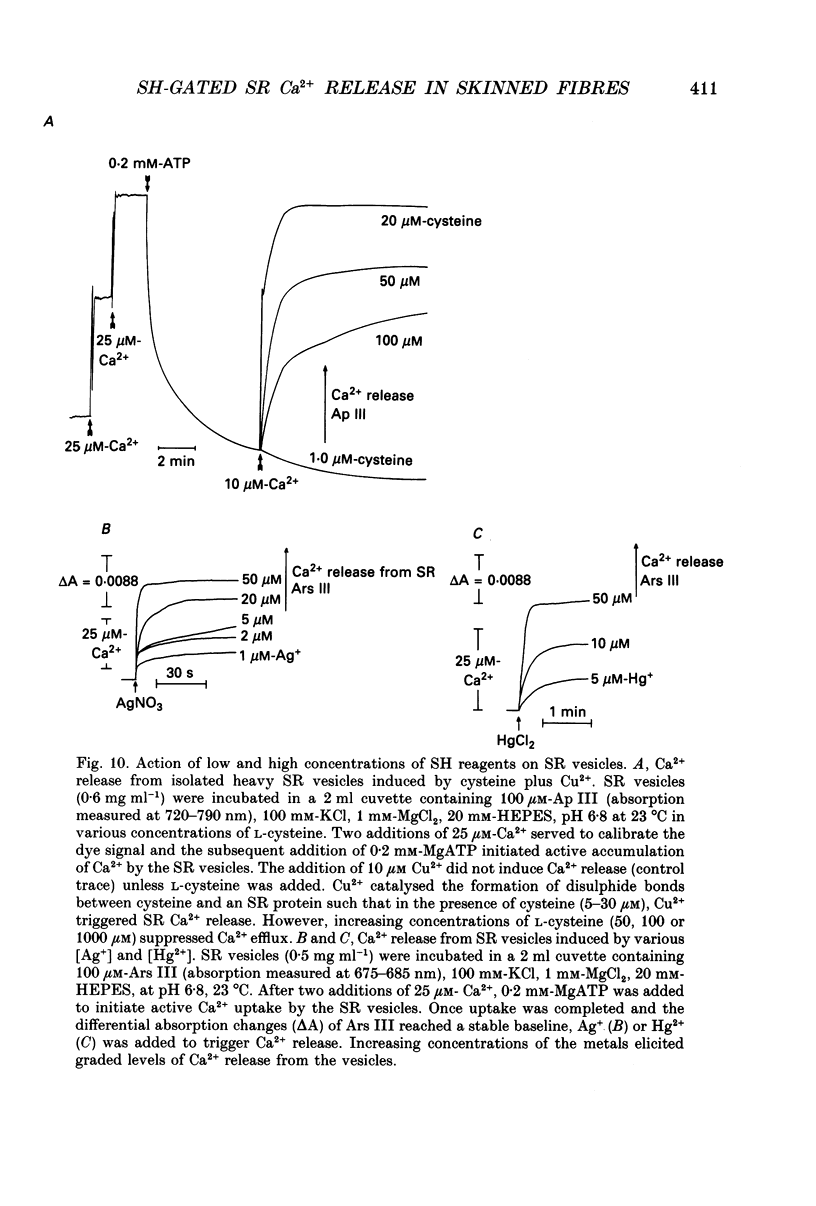

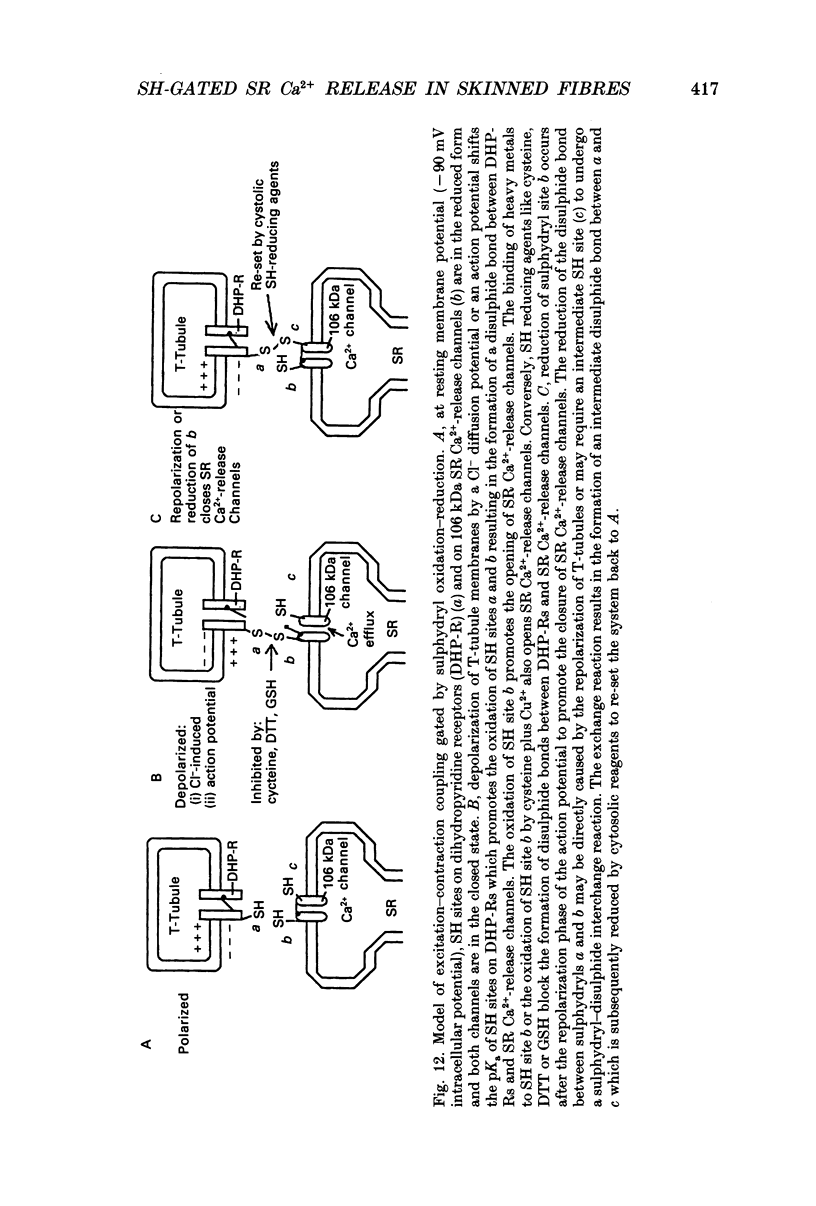

1. By analogy with studies on sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) vesicles, Ca2+ release induced by heavy metals and mercaptans (e.g. cysteine) was investigated in rabbit skinned psoas fibres through measurements of isometric tension. 2. Heavy metals (at 2-5 microM) elicited phasic contractions by triggering Ca2+ release from the SR and had the following order of potency: Hg2+ > Cu2+ > Cd2+ > Ag+ > Ni2+. Higher concentrations produced tonic contractions due to maintained high Ca2+ permeability of SR membranes. 3. Contractions induced by heavy metals required a functional and Ca(2+)-loaded SR, were dependent on [Ca2+]free, blocked by Ruthenium Red (RR), inhibited by free Mg2+ and reduced glutathione (GSH) but not by oxidized glutathione (GSSG). Such contractions were not elicited through direct interaction(s) of heavy metals with the myofilaments. 4. In the presence of catalytic concentrations of Hg2+ or Cu2+ (2-5 microM), additions of cysteine (25-100 microM) elicited rapid twitches, producing 70% of maximal force with a time to half-peak of 2 s. Contractions induced by cysteine plus a catalyst required a functional SR network, were dependent on free [Mg2+] and were blocked by RR or GSH but not by GSSG. 5. In the presence of Hg2+ (2-5 microM), low concentrations of cysteine (10 microM) elicited tonic contractures, but subsequent or higher additions of cysteine (50-100 microM) caused further SR Ca2+ release and tension, followed by rapid and full relaxation. 6. High cysteine (200-250 microM, without Cu2+ or Hg2+) blocked contractions elicited by Cl- induced depolarization of sealed T-tubules. High cysteine probably acted as a sulphydryl reducing agent which promoted rapid relaxation of the fibres through the closure of Ca(2+)-release channels and ATP-dependent re-uptake of Ca2+ by the SR. 7. In some batches of skinned fibres (approximately 10%), cysteine (5-50 microM) alone (without Hg2+ or Cu2+ catalyst) produced rapid twitches. This implied that the catalyst(s) necessary to promote the sulphydryl oxidation reaction with exogenously added cysteine may be present in intact fibres but is usually lost by the skinning procedure. 8. The data demonstrate that skeletal fibres contain a highly reactive and accessible sulphydryl site on an SR protein which can be reversibly oxidized and reduced to respectively, open and close SR Ca(2+)-release channels. A model of sulphydryl-gated excitation-contraction coupling is proposed where the voltage sensor on the T-tubule membrane directly oxidizes sulphydryl sites on SR Ca(2+)-release channels.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abramson J. J., Trimm J. L., Weden L., Salama G. Heavy metals induce rapid calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles isolated from skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Mar;80(6):1526–1530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki T., Oba T., Hotta K. Hg2+-induced contracture in mechanically skinned fibers of frog skeletal muscle. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1985 Sep;63(9):1070–1074. doi: 10.1139/y85-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B., Snowdowne K. W. Measurement of intracellular ionized calcium with aequorin. Methods Enzymol. 1986;124:90–116. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)24011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunder D. G., Dettbarn C., Palade P. Heavy metal-induced Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1988 Dec 15;263(35):18785–18792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallini D., De Marco C., Duprè S., Rotilio G. The copper catalyzed oxidation of cysteine to cystine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1969 Mar;130(1):354–361. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(69)90044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood A. B., Wood D. S., Bock K. L., Sorenson M. M. Chemically skinned mammalian skeletal muscle. I. The structure of skinned rabbit psoas. Tissue Cell. 1979;11(3):553–566. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(79)90062-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. Calculator programs for computing the composition of the solutions containing multiple metals and ligands used for experiments in skinned muscle cells. J Physiol (Paris) 1979;75(5):463–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferenczi M. A., Goldman Y. E., Simmons R. M. The dependence of force and shortening velocity on substrate concentration in skinned muscle fibres from Rana temporaria. J Physiol. 1984 May;350:519–543. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson D. G., Schwartz H. W., Franzini-Armstrong C. Subunit structure of junctional feet in triads of skeletal muscle: a freeze-drying, rotary-shadowing study. J Cell Biol. 1984 Nov;99(5):1735–1742. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.5.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford L. E., Podolsky R. J. Intracellular calcium movements in skinned muscle fibres. J Physiol. 1972 May;223(1):21–33. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1972.sp009831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilkert R., Zaidi N., Shome K., Nigam M., Lagenaur C., Salama G. Properties of immunoaffinity purified 106-kDa Ca2+ release channels from the skeletal sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992 Jan;292(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90043-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai F. A., Erickson H. P., Rousseau E., Liu Q. Y., Meissner G. Purification and reconstitution of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle. Nature. 1988 Jan 28;331(6154):315–319. doi: 10.1038/331315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G., Darling E., Eveleth J. Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides. Biochemistry. 1986 Jan 14;25(1):236–244. doi: 10.1021/bi00349a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutin M. J., Abramson J. J., Salama G., Dupont Y. Rapid Ag+-induced release of Ca2+ from sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles of skeletal muscle: a rapid filtration study. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989 Sep 18;984(3):289–292. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T., Hotta K. Silver ion-induced tension development and membrane depolarization in frog skeletal muscle fibres. Pflugers Arch. 1985 Dec;405(4):354–359. doi: 10.1007/BF00595688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oba T., Iwama H., Aoki T. Ruthenium red and magnesium ion partially inhibit silver ion-induced release of calcium from sarcoplasmic reticulum of frog skeletal muscles. Jpn J Physiol. 1989;39(2):241–254. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.39.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachey L. D. The sarcoplasmic reticulum and transverse tubules of the frog's sartorius. J Cell Biol. 1965 Jun;25(3 Suppl):209–231. doi: 10.1083/jcb.25.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Stambuk R. A., Casida J. E. Ca2+-activated ryanodine binding: mechanisms of sensitivity and intensity modulation by Mg2+, caffeine, and adenine nucleotides. Mol Pharmacol. 1987 Mar;31(3):232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessah I. N., Waterhouse A. L., Casida J. E. The calcium-ryanodine receptor complex of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985 Apr 16;128(1):449–456. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)91699-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S. D., Salama G. The heavy metal ions Ag+ and Hg2+ trigger calcium release from cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990 Feb 15;277(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90548-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios E., Brum G. Involvement of dihydropyridine receptors in excitation-contraction coupling in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1987 Feb 19;325(6106):717–720. doi: 10.1038/325717a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robillard G. T., Konings W. N. A hypothesis for the role of dithiol-disulfide interchange in solute transport and energy-transducing processes. Eur J Biochem. 1982 Oct;127(3):597–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama G., Abramson J. Silver ions trigger Ca2+ release by acting at the apparent physiological release site in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1984 Nov 10;259(21):13363–13369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama G., Scarpa A. Mode of action of diethyl ether on ATP-dependent Ca2+ transport by sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 1983 Nov 15;32(22):3465–3477. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(83)90378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. S., Coronado R., Meissner G. Single channel measurements of the calcium release channel from skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Activation by Ca2+ and ATP and modulation by Mg2+. J Gen Physiol. 1986 Nov;88(5):573–588. doi: 10.1085/jgp.88.5.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. S., Imagawa T., Ma J., Fill M., Campbell K. P., Coronado R. Purified ryanodine receptor from rabbit skeletal muscle is the calcium-release channel of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Gen Physiol. 1988 Jul;92(1):1–26. doi: 10.1085/jgp.92.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson D. G., Thieleczek R. Activation of the contractile apparatus of skinned fibres of frog by the divalent cations barium, cadmium and nickel. J Physiol. 1986 Nov;380:75–92. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson E. W. Excitation of skinned muscle fibers by imposed ion gradients. I. Stimulation of 45Ca efflux at constant [K][Cl] product. J Gen Physiol. 1985 Dec;86(6):813–832. doi: 10.1085/jgp.86.6.813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimm J. L., Salama G., Abramson J. J. Sulfhydryl oxidation induces rapid calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1986 Dec 5;261(34):16092–16098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara J., Tsien R. Y., Delay M. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate: a possible chemical link in excitation-contraction coupling in muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Sep;82(18):6352–6356. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.18.6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe P., Stephenson E. W. Ca2+ dependence of transverse tubule-mediated calcium release in skinned skeletal muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol. 1986 Feb;87(2):271–288. doi: 10.1085/jgp.87.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida T., Kuranaga I., Inoue A. Interaction of myosin with thin filaments during contraction and relaxation: effect of ionic strength. J Biochem. 1982 Aug;92(2):407–412. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N. F., Lagenaur C. F., Abramson J. J., Pessah I., Salama G. Reactive disulfides trigger Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum via an oxidation reaction. J Biol Chem. 1989 Dec 25;264(36):21725–21736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi N. F., Lagenaur C. F., Hilkert R. J., Xiong H., Abramson J. J., Salama G. Disulfide linkage of biotin identifies a 106-kDa Ca2+ release channel in sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1989 Dec 25;264(36):21737–21747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]