Abstract

Background

Despite a reduction of both incidence and mortality from CRC, recent studies have shown an increase in the incidence of early-onset CRC (EO-CRC). Data on this setting are limited. The aim of our study was to evaluate the clinical and molecular profiles of metastatic EO-CRC patients in order to identify differences compared to a late-onset CRC (LO-CRC) control group.

Methods

We retrospectively collected data from 1272 metastatic colorectal cancers from 5 different Italian Institutions. The main objective was to the evaluate clinical outcome for EO-CRC patients in comparison to patients included in the control group.

Results

In the overall population, mOS was 34,7 in EO-CRC pts vs 43,0 months (mo) (p < 0,0001). In the RAS/BRAF mutated subgroup mOS in EO-CRC pts was 30,3 vs 34,0 mo (p = 0,0156). In RAS/BRAF wild-type EO-CRC mOS was 43,0 vs 50,0 mo (p = 0,0290). mPFS was 11,0 in EO-CRC pts vs 14,0 mo (p < 0,0001).

Conclusion

Findings indicate a general worse prognosis for patients with early-onset colorectal cancer compared to late-onset patients. Interestingly this seems to occur regardless of the molecular status. These observations might have a considerable impact on clinical practice and research.

Subject terms: Colon cancer, Rectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common tumor worldwide and the second most common cause of cancer-related death [1, 2]. An epidemiological shift in the age at which CRC is diagnosed has been described for unknown reasons [3]. Over the past two decades, a decreased incidence and mortality in high-income countries was shown. Especially in the elderly owing to improved adherence to national and regional screening programs and, to a lesser extent, therapies. In the age group 50–64 years the above-mentioned epidemiological indicators decreased, although a plateau has followed in the last decade [4]. However, an increased incidence in adults younger than 50 years occurred worldwide [5–10].

Early-onset (EO) colorectal cancer is defined by a diagnosis in adults aged between 18 and 49 years: incidence has been increasing since the mid-1990s, mainly driven by rectal cancer [11], associated with an increased mortality. In the following ten years, it is estimated that 25% of rectal and 10–12% of colon cancers will be diagnosed in people younger than 50 years [10–13] and CRC will be the leading cause of cancer death in people aged 20-49 by the year 2030 [6]. Notably, EO-CRCs patients are not diagnosed through organized screening and, then, diagnosis can be significantly delayed [14–16]. Early exposure to carcinogens, including those related to dietary and lifestyle factors, environmental agents, obesity, and antibiotics could probably play a key pathogenetic role [17–19], in association with the imbalance of the gut microbiome [20, 21].

Younger patients more commonly develop left-sided and rectal tumors [22], have proficient MMR, and exhibit a poorly differentiated/undifferentiated histological pattern [14–27]. Furthermore, cancer that occurs at an early age, compared to that diagnosed at an age >50 years, is more frequently diagnosed at an advanced stage, with a higher risk of regional or distant metastases [27]. Finally, individuals under the age of 50 should have lower chances of being obese or smokers compared to those over 50 [28]. EO-CRC is more likely to be associated with a hereditary syndrome than late-onset (LO) disease: pathogenic germline variants was found in 16–25% VS. 10–15% in LO-CRC. However, 75–84% are sporadic, without an identifiable genetic predisposition [29–31]. A retrospective, multicentre study was carried out to assess differences in clinical and molecular features, as well as outcomes between metastatic EO- versus LO-CRC.

Methods

Study population

Data of 1272 metastatic colorectal patients from five different Italian settings were collected. Six hundred ninety-three patients were diagnosed with EO (≤50 years) metastatic CRC, whereas 579 are a historical cohort of patients aged >50 years. The patients included in the study had been diagnosed with metastatic colorectal cancer between 2008 and 2019. All patients had at least one metastatic site and underwent at least one line of treatment for metastatic disease. Patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Scale from 0 to 2. All patients had an available molecular profile including at least KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and dMMR/MSI-H status. Molecular profile analyzes were performed on the primary tumor using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sequencing or Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). NGS analysis was available for 273 (21.5%). The primary study objective was to compare overall survival of EO- and LO-CRC samples, and of molecular subgroups (i.e., RAS and BRAF groups). The secondary objectives were: Progression-free survival (PFS) of EO- and LO-CRC samples and of molecular subgroups; overall response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) after the first-line treatment. Finally, we performed multivariate analysis for all survival variables (sex, ECOG PS, CEA and Ca19.9 values, first line chemotherapy regimen, age, sideness, metastasectomy and molecular profile) through Cox proportional hazards regression. This study was performed in accordance with the study protocol, the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as those indicated in the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (GCP; ICH E6, 1995), and all applicable regulatory requirements.

Statistical analysis

Sample characteristics were summarized by mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), and by absolute and relative (percentages) frequencies. Differences between subgroups were evaluated using Student t or Mann–Whitney U tests for quantitative variables, and by Pearson Chi-square or Fisher exact tests for qualitative ones. A two-tailed p-value was considered as statistically significant. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test evaluated differences between strata. The role of independent variables was assessed with a logistic regression analysis. PFS was defined as the time from treatment start until progression, second cancer, or death from any cause. Overall survival was defined as the time interval between the date of the treatment start to death or the last follow-up visit for patients who were lost at follow-up. The response rate was defined as the percentage of patients who achieved a partial or complete response to treatment according to RECIST Version 1.1. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who had a partial or complete response to therapy. DCR was defined as the percentage of patients with stable disease or partial/complete response to treatment.

Based on the scientific literature [32], to assess an increased risk of progression or death in younger patients (around 15%), assuming a probability alpha of 0.01 and a beta of 0.01, with a ratio of 1.19, the required sample size would have been 987 patients (536 + 451). Statistical analysis was performed with STATA17 software and the MedCalc Statistical Software Version 20.2016 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2022).

Results

Patients characteristics

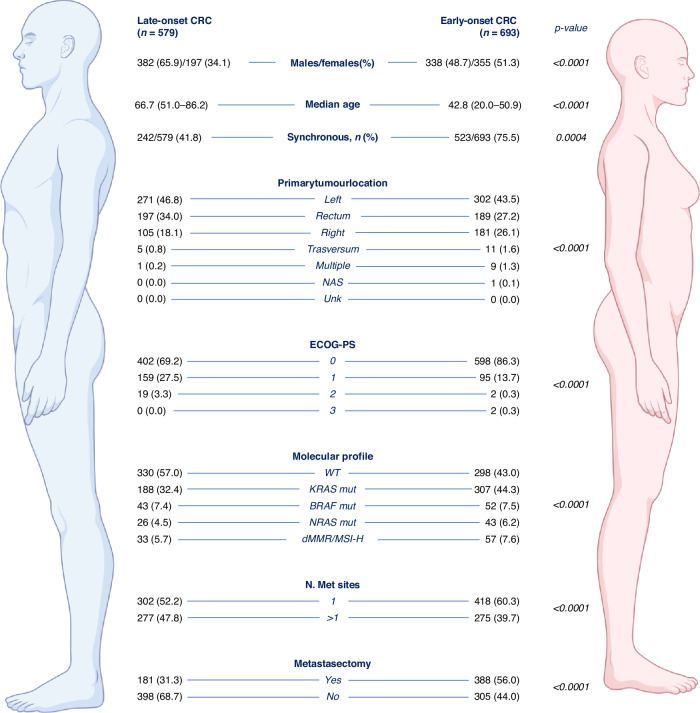

Six hundred and ninety-three EO-CRC patients were compared with a control group of 579 patients. Median (IQR) age was 42.8 (20.0–50.9) years in EO-CRC and 66.7 (51.0–86.2) years in LO-CRC, with a male percentage of 48.7% VS. 65.9%. LO-CRC was located in the left colon (46.8%), in the rectum (34.0%), in the right colon (18.1%), and in the transverse colon (0.8%). EO-CRC was mainly located in the left colon (43.5%), followed by rectum (27.2%), right colon (26.1%), transverse colon (1.6%). Patients with EO-CRC were more frequently diagnosed with synchronous metastasis (75.5% VS. 41.8%) and an ECOG-PS score of 0 (86.3% VS. 69.2%) (Fig. 1). 53.1% of patients underwent resection of the primary tumor, while 21.0% of patients with rectal cancer and synchronous metastases received palliative radiotherapy. In Table 1, the data shows the first-line treatment that the patients received.

Fig. 1.

Patients characteristics.

Table 1.

First line chemotherapy regimens.

| EO-CRCs n(%) | LO-CRCs n(%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Doublet + anti-VEGF | 288 (41.6) | 259 (44.7) |

| Doublet + anti-EGFR | 162 (23.4) | 189 (32.7) |

| Triplet + anti-VEGF | 175 (25.3) | 83 (14.3) |

| Triplet + anti-EGFR | 38 (5.5) | 9 (1.6) |

| Other | 30 (4.2) | 39 (6.7) |

Molecular characteristics

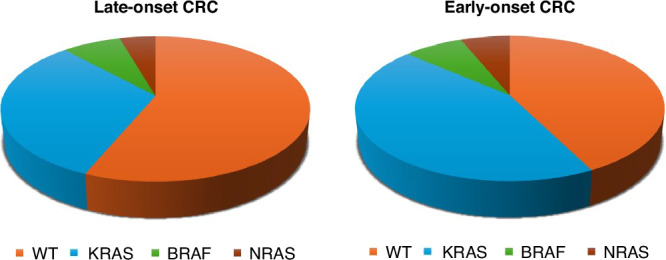

A higher percentage of RAS mutations was found in EO-CRCs: 50.5% VS. 36.9%; 44.3% VS. 32.4% had KRAS mutations, 7.5% VS. 7.4% BRAF V600E mutations, and 6.2% VS. 4.5% NRAS mutations. Wild-type was higher (57.0% VS. 43.0%) in LO-CRCs.

Considering patients with KRAS mutations, 307 were EO-CRC and 188 were LO-CRC. Among the EO-CRC patients, the distribution of specific mutations was as follows: 28 patients (9.1%) had the G12C mutation, 79 (25.7%) were G12D mut, 16 (5.2%) G12A mut, 62 (20.2%) G12V mut, 55 (17.9%) G13D mut, 19 (6.2%) A146 mut, 3 (0.9%) K117N mut, and 45 (14.6%) had other KRAS mutations. In patients with LO-CRC, mutations distribution was similar: 15 patients (7.9%) had the G12C mutation, 52 (27.6%) G12D mut, 11 (5.8%) G12A mut, 41 (21.8%) G12V mut, 26 (13.8%) G13D mut, 19 (6.4%) A146 mut, and 31 (16.4%) had other KRAS mutations.

NGS found at least one mutation in 145 LO- and 116 EO-CRC (P: 0.058): TP53 mutation in 24.8%, p53 wild-type in 8.7% and mutated in 16.1%. EO-CRC patients showed a higher prevalence of TP53 alterations and a lower of wild type (P: 0.0094). APC mutational status was wild type in 7.3% and mutated in 10.8%. APC alterations were more prevalent in LO-CRC (P: 0.0074) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pie charts. Molecular profile distribution in LO-CRCs and EO-CRCs patients.

Correlation with clinical outcome

Median OS was lower in EO-CRCs: 34.7 VS. 43.0 months (HR: 1.33; 95% CI 1.16–1.52), with an increased risk of progression or death in younger patients. Median PFS was significantly lower in EO-CRCs: 11.0 VS. 14.0 months (HR: 1.35; 95% CI 1.18–1.55) (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3. Kaplan–Meier curves for EO-CRC and LO-CRC, overall population.

a Overall survival and b progression-free survival in the overall population.

In the subgroup, RAS/BRAF wild-type, EO-CRC showed a lower median OS and PFS: 43.0 VS. 50.0 months (HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.02–1.56) and 13.0 VS. 16.0 months (HR 1.31; 95% CI 1.08–1.60), respectively (Fig. 4a, b).

Fig. 4. Kaplan–Meier curves for EO-CRC and LO-CRC, RAS and BRAF wild-type population.

a Overall survival and b progression-free survival in the wild-type population.

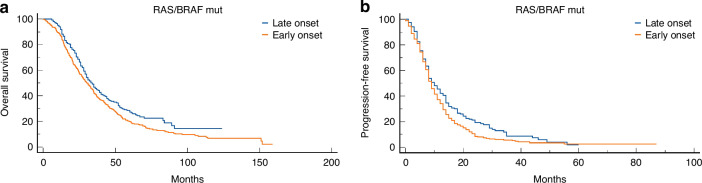

In the subgroup, RAS/BRAF mutated median OS and PFS were lower in EO-CRC patients: 30.32 VS. 34.0 months (HR 1.25; 95% CI 1.04–1.50) and 9.0 VS. 10.0 months (HR 1.28; 95% CI 1.06–1.55), respectively (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5. Kaplan–Meier curves for EO-CRC and LO-CRC, RAS/BRAS mutated population.

a Overall survival and b progression-free survival in the RAS/BRAF mutated population.

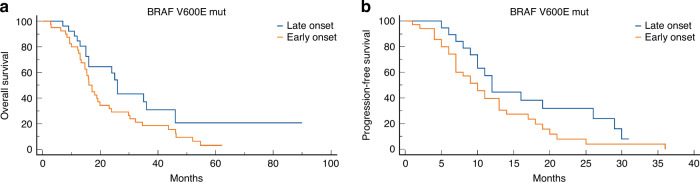

In the BRAF V600E mutated subgroup, EO-CRC patients showed a lower median OS and PFS: 16.0 VS. 26.0 months (HR 1.75; 95% CI 1.01 to 3.02) and 10.0 VS. 12.0 months (HR 1.70; 95% CI 0.92 to 3.14), respectively (Fig. 6a, b).

Fig. 6. Kaplan–Meier curves for EO-CRC and LO-CRC, BRAF V600E mutated population.

a Overall survival and b progression-free survival in the BRAF V600E mut population.

ORR in EO- and LO-CRC was 63% and 67%, respectively, whereas DCR was 87.8% and 93.5%, respectively. EO-CRC showed a higher PD rate (12.4% VS. 6.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall response rates.

| Evaluable patients | Late Onset (n = 539) n(%) | Early Onset (n = 614) n(%) |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 51 (9.5) | 46 (7.5) |

| PR | 311 (57.7) | 345 (56.2) |

| SD | 142 (26.3) | 147 (23.9) |

| PD | 35 (6.5) | 76 (12.4) |

| ORR | 362 (67.2) | 391 (63.7) |

| DCR | 504 (93.5) | 538 (87.6) |

Patients with metachronous metastases had a significantly longer mOS and mPFS compared to patients with synchronous metastases: 52.0 vs. 34.0 months (p < 0.0001) for mOS and 14.0 vs. 12.0 months (p < 0.0001) for mPFS, respectively. However, within the two subgroups, EO patients had significantly shorter mOS and mPFS compared to LO patients. Among patients with synchronous metastases, EO patients had a mOS of 33.0 months compared to 37.0 months for LO patients (p < 0.0001). In the case of metachronous metastases, EO patients had a mOS of 43.0 months compared to 61.0 months for LO patients (p < 0.0001).

Patients with liver involvement, 59.2% of whom were early-onset, had a worse mOS compared to patients without liver involvement: 35.0 VS 43.0 months (p = 0.0006). Peritoneal metastases, found in 64% of EO patients, also showed significantly lower mOS: 31.0 vs. 40.0 months (p = 0.0001).

Patients with lung as the only metastatic site, 58% of whom were late-onset, showed a significantly higher mOS compared to patients with more than one metastatic site: 43.0 vs. 35.0 months (p = 0.0006). In the context of diffuse metastatic disease, a total of 9 patients developed brain metastases, 6 of whom were EO and 3 were LO.

In the overall population, patients who underwent metastasectomy had a higher mOS compared to those who did not undergo the procedure. However, within the metastasectomy group, patients with early-onset colorectal cancer had a lower mOS compared to those with late-onset colorectal cancer (46.0 VS 60.0 months, p < 0.0001). Similar results were observed when analyzing subgroups of RAS-BRAF wild type patients (53.0 VS 81.0 months, p < 0.0001) and RAS-BRAF mutated patients (42.0 VS 45.0 months, p < 0.0001).

The following parameters were considered in the multivariate analysis: baseline values of CEA and Ca19.9 biomarkers, ECOG PS, age, primary tumor site, first-line regimen, metastasectomy, and molecular profile (All RAS/BRAF mutated). The study found that individuals aged 50 or younger had a strong negative correlation with overall survival (p = 0.0005). Other factors that were independently associated with overall survival were ECOG-PS (p < 0.0001) and metastasectomies (p = 0.0058) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis.

| Standard error | P value | Exp(b) | 95% CI Exp(b) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA | 0,0001 | 0,1990 | 1,0002 | 0,9999 to 1,0004 |

| Ca19.9 | 0,0000 | 0,3329 | 1,0000 | 1,0000 to 1,0000 |

| ECOG-PS | 0,2187 | 0,0001 | 2,8795 | 1,8755 to 4,4209 |

| 1st line Regimen | 0,1316 | 0,9595 | 1,0067 | 0,7778 to 1,3031 |

| Age ≤ 50 yo | 0,2327 | 0,0005 | 2,2401 | 1,4197 to 3,5348 |

| Sideness | 0,1335 | 0,3223 | 1,1413 | 0,8785 to 1,4827 |

| Metastasectomy | 0,2109 | 0,0058 | 0,5589 | 0,3697 to 0,8451 |

| Sex | 0,2018 | 0,7599 | 1,0636 | 0,7162 to 1,5797 |

| All RAS/BRAF mut | 0,1949 | 0,5574 | 1,1212 | 0,7651 to 1,6429 |

Discussion

Despite EO-CRC shows a peculiar molecular, clinical, and prognostic pattern, guidelines are based on studies including all patient categories, avoiding diagnostic and therapeutic tailoring. Our study showed that >70% EO-CRC patients have left-sided lesions, and nearly one-third with rectal cancer [28–34]; moreover, a higher percentage have metastatic disease at diagnosis (75.5% with synchronous metastases). A more advanced stage of disease at diagnosis is more likely as described in large cohorts [14, 27, 35, 36]. The absence of screening programs in those aged <50 years could contribute to diagnostic delay (7 to 9 months) [37, 38]. A higher incidence of BRAF V600E wild-type status, absence of a methylator phenotype, and evidence of CIN were found in sporadic EO-CRC [29] TP53 and CTNNB1 alterations are more prevalent in the EO-CRC cohort, whereas APC, KRAS, BRAF, and FAM123B variants in the older cohort [39]. In line with the literature, a higher percentage of KRAS mutations was described: 50.5% VS. 36.9% with similar proportions of BRAF V600E mutation (7.5% VS. 7.4%).

In particular, KRAS mutations are associated with a worse prognosis compared to the non-mutated population, even in patients with liver metastases who have undergone resection [40].

Higher prevalence of TP53 mutation and lower of APC mutation were confirmed in EO-CRC patients (72% VS. 58% and 50% VS. 67.4%, respectively). A review of 9 phase III trials in patients with advanced CRC [41] and several cohort studies [42–44] showed that although younger age is associated with shorter PFS, no difference in OS or RR was found in younger patients. However, in a study of stage IV CRC, age was a significant predictor of OS, with younger patients showing worse survival and PFS [32]. Despite the aggressive nature and advanced stage at diagnosis, survival of EO-CRC was found to be equivalent to LO-CRC [22, 26, 28, 35, 45–49]. First-line chemotherapy is associated with a higher PD rate in EO-CRC (12.4% VS. 6.5%). Furthermore, median OS and PFS were lower. We showed that the increased risk of death and progression can be found in the subgroups RAS/BRAF mutated, RAS/BRAF WT, and BRAF V600E mutated.

The main limitations of our study is its retrospective nature and the recruitment of an unselected population, with different clinical approaches in the participating centers. Additionally, adherence to screening programs in LO-CRC patients may have contributed to the early diagnosis of metastatic disease, thereby partially impacting the differences in survival rates. Finally, it should be noted that the analysis was conducted from 2008 to 2019, before the availability of several therapies, which at the time were not approved, were pending approval, or were not widely used such as: encorafenib, tucatinib, and pembrolizumab.

Another aspect to consider is the availability of NGS tests available in the time frame considered. Over the years, NGS panels have improved in performance and in the number of genes that can be evaluated with a single test, therefore with modern panels more mutations can be detected.

In the dataset, there were a total of 90 patients with dMMR or MSI-H. Out of these, 17 were treated with immunocheckpoint inhibitors (12 EO patients and 5 LO patients). However, due to the low numbers, it is difficult to draw statistically significant differences. In this subgroup of patient, 23 cases of Lynch syndrome were diagnosed. It should be noted that in the time frame indicated, the MSI-H test was not yet universally performed, and therefore was not available for some patients.

It is also important to investigate the role of targeted therapies for the KRAS G12C mutation and the potential impact they could have on differences in prognosis.

In conclusion, EO-CRC show peculiar clinical and biological features, with a more aggressive and more advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Outcomes are not better, mirroring different biology or a greater tumor burden at presentation. Further research should focus on translational studies to assess differences in treatment resistance and early metastasis.

Author contributions

Andrea Pretta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Pina Ziranu: Resources, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Eleonora Perissinotto: Resources, Data Curation. Filippo Ghelardi: Resources, Data Curation. Federica Marmorino: Resources, Data Curation. Riccardo Giampieri: Resources, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Mariangela Puci: Data Curation, Formal analysis. Maria Caterina De Grandis: Resources, Data Curation. Eleonora Lai: Resources. Vincenzo Nasca: Resources, Data Curation. Paolo Ciracì: Resources, Data Curation. Marco Puzzoni: Resources. Krisida Cerma: Resources. Data Curation. Carolina Sciortino: Resources, Data Curation. Ada Taravella: Resources, Data Curation. Gianluca Pretta: Writing - Review & Editing. Lorenzo Giuliani: Resources, Data Curation. Camilla Damonte: Resources, Data Curation. Valeria Pusceddu: Resources, Data Curation. Giovanni Sotgiu: Data Curation, Formal analysis. Rossana Berardi: Resources. Sara Lonardi: Resources, Data Curation. Francesca Bergamo: Resources, Data Curation. Filippo Pietrantonio: Resources, Data Curation. Chiara Cremolini: Resources, Data Curation. Mario Scartozzi: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing.

Data availability

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics Committee approval was obtained for the study (Protocol number 2020/10912 – code: EMIBIOCCOR) from Cagliari Indipendent Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all participants for their tissues to be utilized for this work. This study was performed in accordance with the study protocol, the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki as well as those indicated in the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Note for Guidance on Good Clinical Practice (GCP; ICH E6, 1995), and all applicable regulatory requirements.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akimoto N, Ugai T, Zhong R, Hamada T, Fujiyoshi K, Giannakis M, et al. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:230–43. 10.1038/s41571-020-00445-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araghi M, Soerjomataram I, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Cabasag CJ, Morrison DS, et al. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence in seven high-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:511–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma J, Rosenberg PS, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw322 10.1093/jnci/djw322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey CE, Hu CY, You YN, Bednarski BK, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Skibber JM, et al. Increasing disparities in the age-related incidences of colon and rectal cancers in the United States, 1975-2010. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:17–22. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feletto E, Yu XQ, Lew JB, St John DJB, Jenkins MA, Macrae FA, et al. Trends in colon and rectal cancer incidence in Australia from 1982 to 2014: analysis of data on over 375,000 cases. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28:83–90. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner DR, Ruan Y, Shaw E, De P, Heitman SJ, Hilsden RJ. Increasing colorectal cancer incidence trends among younger adults in Canada. Prev Med. 2017;105:345–9. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larsen IK, Bray F. Trends in colorectal cancer incidence in Norway 1962-2006: an interpretation of the temporal patterns by anatomic subsite. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:721–32. 10.1002/ijc.24839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araghi M, Soerjomataram I, Bardot A, Ferlay J, Cabasag CJ, Morrison DS, et al. Changes in colorectal cancer incidence in seven high-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:511–8. 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:145–64. 10.3322/caac.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.REACCT Collaborative, Zaborowski AM, Abdile A, Adamina M, Aigner F, d’Allens L, Allmer C, et al. Characteristics of early-onset vs late-onset colorectal cancer: a review. JAMA Surg. 2021;156:865–74. 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.2380. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bhandari A, Woodhouse M, Gupta S. Colorectal cancer is a leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality among adults younger than 50 years in the USA: a SEER-based analysis with comparison to other young-onset cancers. J Investig Med. 2017;65:311–5. 10.1136/jim-2016-000229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen FW, Sundaram V, Chew TA, Ladabaum U. Advanced-stage colorectal cancer in persons younger than 50 years not associated with longer duration of symptoms or time to diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:728–37.e3. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu GS, Anders R, Walde A, Leal AD, Teng King G, Leong S, et al. High incidence of advanced stage cancer and prolonged rectal bleeding history before diagnosis in young-onset patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3576

- 16.Yarden RI, Newcomer KL; Never Too Young Advisory Board, Colorectal Cancer Alliance. Young onset colorectal cancer patients are diagnosed with advanced disease after multiple misdiagnoses. 2019 AACR Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA; 2019.

- 17.Liu PH, Wu K, Ng K, Zauber AG, Nguyen LH, Song M, et al. Association of obesity with risk of early-onset colorectal cancer among women. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:37–44. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen BW, Bjerregaard LG, Ängquist L, Gögenur I, Renehan AG, Osler M, et al. Change in weight status from childhood to early adulthood and late adulthood risk of colon cancer in men: a population-based cohort study. Int J Obes. 2018;42:1797–803. 10.1038/s41366-018-0109-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J, Haines C, Watson AJM, Hart AR, Platt MJ, Pardoll DM, et al. Oral antibiotic use and risk of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom, 1989-2012: a matched case-control study. Gut. 2019;68:1971–8. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akimoto N, Ugai T, Zhong R, Hamada T, Fujiyoshi K, Giannakis M, et al. Rising incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer - a call to action. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:230–43. 10.1038/s41571-020-00445-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eng C, Jácome AA, Agarwal R, Hayat MH, Byndloss MX, Holowatyj AN, et al. A comprehensive framework for early-onset colorectal cancer research. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:e116–28. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00588-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdelsattar ZM, Wong SL, Regenbogen SE, Jomaa DM, Hardiman KM, Hendren S. Colorectal cancer outcomes and treatment patterns in patients too young for average-risk screening. Cancer. 2016;122:929–34. 10.1002/cncr.29716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teng A, Lee DY, Cai J, Patel SS, Bilchik AJ, Goldfarb MR. Patterns and outcomes of colorectal cancer in adolescents and young adults. J Surg Res. 2016;205:19–27. 10.1016/j.jss.2016.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Georgiou A, Khakoo S, Edwards P, Minchom A, Kouvelakis K, Kalaitzaki E, et al. Outcomes of patients with early onset colorectal cancer treated in a UK Specialist Cancer Center. Cancers. 2019;11:1558. 10.3390/cancers11101558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang JT, Huang KC, Cheng AL, Jeng YM, Wu MS, Wang SM. Clinicopathological and molecular biological features of colorectal cancer in patients less than 40 years of age. Br J Surg. 2003;90:205–14. 10.1002/bjs.4015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang DT, Pai RK, Rybicki LA, Dimaio MA, Limaye M, Jayachandran P, et al. Clinicopathologic and molecular features of sporadic early-onset colorectal adenocarcinoma: an adenocarcinoma with frequent signet ring cell differentiation, rectal and sigmoid involvement, and adverse morphologic features. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1128–39. 10.1038/modpathol.2012.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.You YN, Xing Y, Feig BW, Chang GJ, Cormier JN. Young-onset colorectal cancer: is it time to pay attention? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:287–9. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cercek A, Chatila WK, Yaeger R, Walch H, Fernandes GDS, Krishnan A, et al. A comprehensive comparison of early-onset and average-onset colorectal cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1683–92. 10.1093/jnci/djab124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinicrope FA. Increasing incidence of early-onset colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:1547–58. 10.1056/NEJMra2200869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirzin S, Marisa L, Guimbaud R, De Reynies A, Legrain M, Laurent-Puig P, et al. Sporadic early-onset colorectal cancer is a specific sub-type of cancer: a morphological, molecular and genetics study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e103159. 10.1371/journal.pone.0103159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lieu CH, Golemis EA, Serebriiskii IG, Newberg J, Hemmerich A, Connelly C, et al. Comprehensive genomic landscapes in early and later onset colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:5852–8. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieu CH, Renfro LA, de Gramont A, Meyers JP, Maughan TS, Seymour MT, et al. Association of age with survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis from the ARCAD Clinical Trials Program. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2975–84. 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer JE, Narang T, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Pochapin MB, Christos PJ, Sherr DL. Increasing incidence of rectal cancer in patients aged younger than 40 years: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer. 2010;116:4354–9. 10.1002/cncr.25432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glover M, Mansoor E, Panhwar M, Parasa S, Cooper GS. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer in average risk adults 20-39 years of age: a population-based national study. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:3602–9. 10.1007/s10620-019-05690-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kneuertz PJ, Chang GJ, Hu CY, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Eng C, Vilar E, et al. Overtreatment of young adults with colon cancer: more intense treatments with unmatched survival gains. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:402–9. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.3572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saraste D, Järås J, Martling A. Population-based analysis of outcomes with early-age colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2020;107:301–9. 10.1002/bjs.11333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ben-Ishay O, Brauner E, Peled Z, Othman A, Person B, Kluger Y. Diagnosis of colon cancer differs in younger versus older patients despite similar complaints. Isr Med Assoc J. 2013;15:284–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dozois EJ, Boardman LA, Suwanthanma W, Limburg PJ, Cima RR, Bakken JL, et al. Young-onset colorectal cancer in patients with no known genetic predisposition: can we increase early recognition and improve outcome? Medicine. 2008;87:259–3. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181881354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsilimigras DI, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Bagante F, Moris D, Cloyd J, Spartalis E, et al. Clinical significance and prognostic relevance of KRAS, BRAF, PI3K and TP53 genetic mutation analysis for resectable and unresectable colorectal liver metastases: a systematic review of the current evidence. Surg Oncol. 2018;27:280–8. 10.1016/j.suronc.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rhaiem R, Duramé A, Primavesi F, Dorcaratto D, Syn N, Rodríguez ÁH, et al. Critical appraisal of surgical margins according to KRAS status in liver resection for colorectal liver metastases: should surgical strategy be influenced by tumor biology? Surgery. 2024;176:124–33. 10.1016/j.surg.2024.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blanke CD, Bot BM, Thomas DM, Bleyer A, Kohne CH, Seymour MT, et al. Impact of young age on treatment efficacy and safety in advanced colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of patients from nine first-line phase III chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2781–6. 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung YF, Eu KW, Machin D, Ho JM, Nyam DC, Leong AF, et al. Young age is not a poor prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1255–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00805.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schellerer VS, Merkel S, Schumann SC, Schlabrakowski A, Förtsch T, Schildberg C, et al. Despite aggressive histopathology survival is not impaired in young patients with colorectal cancer : CRC in patients under 50 years of age. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:71–9. 10.1007/s00384-011-1291-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McMillan DC, McArdle CS. The impact of young age on cancer-specific and non-cancer-related survival after surgery for colorectal cancer: 10-year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:557–60. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanford SD, Zhao F, Salsman JM, Chang VT, Wagner LI, Fisch MJ. Symptom burden among young adults with breast or colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:2255–63. 10.1002/cncr.28297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldvaser H, Purim O, Kundel Y, Shepshelovich D, Shochat T, Shemesh-Bar L, et al. Colorectal cancer in young patients: is it a distinct clinical entity? Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:684–95. 10.1007/s10147-015-0935-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vatandoust S, Price TJ, Ullah S, Roy AC, Beeke C, Young JP, et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer in young adults: a study from the South Australian population-based registry. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:32–6. 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang MJ, Ping J, Li Y, Adell G, Arbman G, Nodin B, et al. The prognostic factors and multiple biomarkers in young patients with colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10645 10.1038/srep10645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez L, Brennan K, Karim S, Nanji S, Patel SV, Booth CM. Disease characteristics, clinical management, and outcomes of young patients with colon cancer: a population-based study. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2018;17:e651–61. 10.1016/j.clcc.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.