Abstract

Zinc (Zn) and its alloys have been the focus of recent materials and manufacturing research for orthopaedic implants due to their favorable characteristics including desirable mechanical strength, biodegradability, and biocompatibility. In this research, a novel process involving additive manufacturing (AM) augmented casting was employed to fabricate zinc-magnesium (Zn-0.8 Mg) artifacts with surface lattices composed of triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS), specifically gyroid. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis confirmed that Zn-Mg intermetallic phases formed at the grain boundary. Micro indentation testing resulted in hardness value ranging from 83.772 to 99.112 HV and an elastic modulus varying from 92.601 to 94.625 GPa. Results from in vitro cell culture experiments showed that cells robustly survived on both TPMS and solid scaffolds, confirming the suitability of the material and structure as biomedical implants. This work suggests that this novel hybrid manufacturing process may be a viable approach to fabricating next generation biodegradable orthopaedic implants.

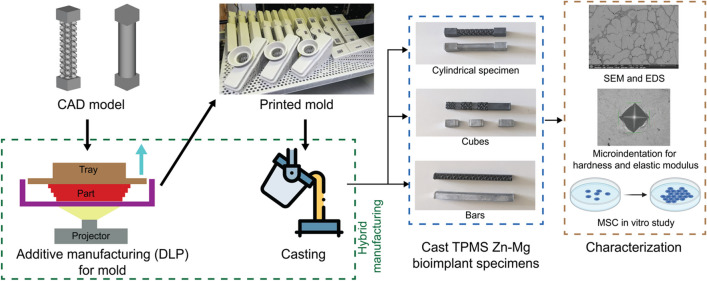

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Investment casting, Tissue engineering, Mechanical properties, Additive manufacturing, Intermetallics, In vitro tissue engineering

Introduction

Recently, zinc (Zn) has become a biomaterial of interest in orthopaedic fracture repair applications due to its favorable biological characteristics, which include osteoconductivity, mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [1–5]. Biodegradable trauma implants have an underexplored clinical potential. These devices gradually dissolve while the fracture heals, leading to increased mechanical loading on the fracture callus, which has been shown to improve and accelerate healing [6–10]. This approach may also eliminate the need for additional surgery for implant removal [11]. Zn has a favorable degradation rate (around 0.1 ~ 0.3 mm/year [12, 13]) which closely matches with natural bone healing process (around 0.2 ~ 0.5 mm/year [14, 15]) when compared to other biocompatible metals like magnesium (Mg) (around 0.8 ~ 2.7 mm/year [15–17]) and Iron (Fe) (< 0.2 mm/year [13, 18]). In addition, biodegradable Zn products are compatible with human tissues [19] and do not accumulate in the body [20].

In addition to having a biodegradation rate closely aligned with natural bone growth, zinc (Zn) also demonstrates favorable biodegradation outcomes. Corrosion products of other implant materials, like Fe do not degrade easily in the body [21] and pure Fe corrosion products can stay in the body for up to 9 months and potentially become toxic for the human body [22, 23]. In contrast, products from Zn degradation like Zn ions can be eliminated from the body through urination and defecation [20, 24]. Furthermore, the degradation products (i.e., zinc oxide, zinc hydroxide, hydrozincite, and hopeite) are generally considered to be inert as they do not provoke significant immune response [25]. In addition to that, Zn ions released during the degradation process get absorbed by the tissues [26]. Zn ions are the second most abundant trace element in the human body and play a critical role in various biological functions including being cofactor of over 300 enzymes in the human body [26, 27]. Additionally, Zn also helps with natural growth, protein, and DNA synthesis making them an attractive candidate for the bone implant [28]. The primary mode of Zn degradation in vivo is through surface erosion forming a protective layer of oxide [26]. While surface erosion is the dominant process, bulk degradation also occurs. Small, irregular pits and shallow cracks can form within the Zn implant over time. The degradation rate of Zn alloys is typically uniform and slows down over time. This controlled degradation is advantageous for maintaining the structural integrity of implants during the healing process [25].

Despite having a favorable biocompatibility and biodegradation behavior, the pure Zn lacks mechanical strength for implant application. Alloying is a well-practiced solution to improve the strength and biodegradation behavior of Zn by introducing one or more second phases [29–33]. In recent times, the Mg has garnered more attention for alloying with Zn. Mg is not soluble in Zn and forms intermetallic compounds [24, 32, 33]. These secondary Zn-Mg phases are harder than the Zn and have been shown to improve the strength from a harder phase. Also, the corrosion resistance performance was shown to improve from the solid solution hardening [32, 34]. Furthermore, Mg acts as a grain refiner and the intermetallics restrict grain growth resulting in finer microstructure and improved strength [24, 35]. Several studies looked in the effect of the amount of Mg content (ranging from 0 to 3 wt%) to understand its effect on the Zn alloy [12, 24, 36, 37]. The Mg content is considered to be low for these alloys. Hammam et al. [24] found that increasing the Mg content results in a higher degree of fineness of the microstructure up to 0.6 wt%. Adding further Mg resulted in a coarser microstructure. A similar trend of increasing grain refinement with increasing Mg content was observed in the study conducted by Krieg et al. [36]. Furthermore, they found the finer microstructure resulted in better corrosion resistance. Kubásek et al. [38] showed that a composition of 0.8 wt% Mg resulted in the highest ultimate tensile strength improving over 465% compared to pure Zn. Adding further Mg resulted in reduced strength. For these reasons, a Zn alloy with 0.8 wt% Mg was selected for this study.

In addition to the material used for the implant, the structure of the device also plays a critical role in the biological function. The degree of cell attachment to an implant is highly affected by the surface area [39–41] of the device. Internal lattice structures within the implant can be effectively designed to alter mechanical strength and increase the effective surface area [42, 43]. In particular, triply periodic minimal surface lattice designs (TPMS) have the potential to increase surface area for the same volume better than other lattice designs [44–49]. TPMS structures offer an attractive design framework because they allow fluids to pass freely throughout the entire interconnected pore network [50, 51]. There are a number of different TPMS structures available that have been used for biomedical implants like gyroid, primitive, diamond, and I-WP. Among these, gyroid tends to be stiffer and have more isotropic mechanical behavior compared to other TPMS structures. In addition, the smooth surface of gyroids makes them less prone to stress concentration during loading, potentially resulting in better structural integrity [52]. Furthermore, gyroids have better suitability for additive manufacturing [53]. For these reasons, gyroid was selected for this study over the other TPMS structures.

Additive manufacturing (AM) has improved the ability to manufacture complex lattice structures that are otherwise difficult or impossible to machine. However, direct metal AM is an expensive process, and mechanical properties of parts depend heavily on the print direction [54, 55]. Instead, casting and subtractive machining approaches are typically used for metal implants due to the consistency in part characteristics. Casting has been used to manufacture several orthopaedic implants approved by the Food and Drug Administration and used in patients [56–58]. In general, solid cast parts have more homogenous mechanical properties compared to AM parts, which are often anisotropic.

Despite being able to produce parts with homogenous mechanical characteristics, casting lacks the ability to generate, and control interconnected porous lattice structures which are good for cell proliferation and bone growth [59, 60]. AM can provide the freedom of structural design, but direct AM of pure Zn is still in its early stages of technological development. One common issue with AM of Zn is the inability to print 100% dense parts [61]. Furthermore, a relatively small gap between the melting and boiling temperature of Zn (420 °C and 907 °C) makes any direct thermal energy-based AM process difficult for Zn and susceptible to pore generation [62]. Finally, the mismatch between the melting temperature of Zn and Mg can also affect the manufacturing process. All these considerations make the Zn-Mg alloy to be a suitable candidate for the hybrid AM process where the mold will be 3D printed to impart complex internal structure for the casting process. The hybrid AM process captures the structural freedom imparting from the AM process and combines it with the favorable characteristics of cast part.

The objective of this research is to establish and validate a workflow for AM-augmented zinc-based implants via casting that can include advantageous TPMS lattice architecture. Currently, the feasibility and efficacy of a hybrid AM approach for zinc-based cast implants with lattice architectural design and cell viability are not well studied. Currently, the feasibility and efficacy of a hybrid AM approach for zinc-based cast implants with lattice architectural design and cell viability are not well studied. Most studies have focused on cast ingots, either formed directly into solid shapes [63–65] or went through forming process like rolling and extrusion [66–69]. In both instances, the direct cast specimen lacked any internal structure. In this study, we successfully fabricated TPMS and solid scaffolds through an AM-augmented casting process and conducted mechanical, chemical, and cell culture experimentation. The results indicated favorable mechanical characteristics and cellular activities suitable for use as bone scaffolds. We hypothesized that AM-augmented zinc implant materials would demonstrate similar structural, mechanical, chemical, and cellular properties to traditional zinc implant materials which are solid cast with a composition of Mg ranging from 0 to 3 wt%.

Material and methods

Two designs of test coupons were used in this study: cylinders (17.5 mm), and witness cubes (25 mm) in both solid and TPMS designs using computer-aided drawing (CAD) software (nTop, New York, NY). Sheet-based gyroid structures with a cell size of 6 mm and sheet thickness of 1 mm were designed prior to fabricating ceramic molds for investment casting (Fig. 1) The molds were printed in porcelain ceramics using a digital light processing (DLP) machine (Admaflex 300, ADMATEC, Netherlands). The Zn-Mg alloy was prepared by melting ingots of commercially available pure Zn (99.99%) and pure Mg (99.99%). The melting process was done in a graphite-coated crucible in an electric furnace at a temperature of 690 °C. The molten metals were stirred with a graphite rod to ensure proper mixing. After the skimming of the slags off, the preheated molds were cast with 550 ± 5 °C.

Fig. 1.

a Investment mold used for casting Zn specimen, b cylindrical samples; solid cylinder on the left and cylinder with gyroid body on the right

SEM, EDS, and microhardness testing

The solid witness cubes were polished down to 1 µm using an ALLIED MetPrep 3 according to ASTM E3 [70] and cleaned in an ultrasonic bath using micro-organic soap to remove any micro-contaminants and polishing solutions. Subsequently, the samples were characterized using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Thermo Scientific Apreo 2, Waltham, MA) equipped with energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) unit at a working distance of 10 mm with an operating voltage and current of 15 kV and 1.6 nA, respectively. In addition, microhardness samples were progressively polished to 1 µm to avoid any influence of surface roughness. Tests were conducted using a Vickers diamond indenter (NANOVEA PB1000, Irvine, CA) according to ASTM E2546 [71]. The maximum applied force was 1 N with a loading and unloading rate of 0.05 N/sec at a creep of 5 s for the measured Poisson’s ratio of 0.25. The modulus of the material was calculated by following the displacement of the indenter in the specimen. Any change in the indentation after reaching maximum applied force was due to elastic recovery in the specimen and the slope of this line can be used to calculate the modulus [72].

In vitro cell culture experiment

Solid and TPMS cylindrical specimens (n = 9) (17.5 mm diameter × 60 mm height) were fabricated for cell seeding. The cylinders were cut into smaller discs (17.5 mm diameter × 6.5 mm height) using a wire-electrical discharge machining (W-EDM) process which ensured that a negligible amount of material was lost in the machining process. These discs were then cleaned and sterilized in an ethanol gradient followed by an overnight immersion in 20 mg/ml fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich F1141). Immediately before seeding, scaffolds were washed in 1X PBS to remove any unbound fibronectin. Scaffolds were seeded with bovine mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), previously isolated from the femoral and tibial bone marrow of juvenile calves, which had been passaged 3 times prior to application. Cells were seeded at a density of 6666 cells/mm2 on both surfaces, and scaffolds were cultured upright at standard culture conditions (21% O2, 5% CO2, 37 °C) in a non-TC-treated polystyrene 12-well plate for 4 weeks. Scaffolds were given fresh basal media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s high glucose medium (Invitrogen 11965084) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (R&D Systems S11150) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin/fungizone (Invitrogen 15240062) twice a week.

The metabolic activity of attached cells was quantified using an Alamar blue assay (ThermoFisher DAL1100) according to the manufacturer’s instructions every week for 4 weeks. Briefly, samples were incubated in Alamar blue cell viability reagent (diluted 1:10 in basal media) at standard culture conditions for 3 h on an orbital shaker set to “5,” after which 100 ml of media from each sample was taken in triplicate and its fluorescent signal read on a plate reader (excitation: 560 nm, emission: 590 nm). At week 4, scaffolds were removed from culture for cell staining (n = 3) and biochemical analysis (n = 6). The nuclei and actin filaments of attached cells were stained using DRAQ5 (ThermoFisher 62251) and Alexa Fluor 546 Phalloidin (ThermoFisher A22283), respectively, as previously described [73]. Following removal from culture, scaffolds were washed in 1X PBS three times. Cells were permeabilized for 5 min at 4 °C using a solution of 0.5% v/v Triton X-100, 10.75% w/v sucrose, and 0.06% w/v magnesium chloride in 1X PBS followed by three more washes in 1X PBS. Actin was labeled by incubating samples for 1 h at 37 °C in a solution of 0.001% v/v Alexa Fluor 546 Phalloidin and 1% w/v bovine serum albumin in 1X PBS, followed by three washes in 1X PBS. Finally, scaffolds were incubated in 5 mM DRAQ5 for 15 min at ambient temperature, washed three times in 1X PBS, and imaged using a multichannel confocal microscope (Nikon A1R).

To prepare for biochemical analysis, scaffolds (n = 6) were digested in 0.5% proteinase K overnight (2 ml per sample) at 60 °C. Digestion solutions were analyzed for DNA content using a Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA assay kit (ThermoFisher P7589) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in which 10 ml of each digested sample was reacted with 100 ml of PicoGreen working solution in triplicate for 5 min. Its fluorescent emission was subsequently read on a plate reader (excitation, 480 nm; emission, 520 nm). Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content was measured using a dimethylmethylene blue (DMMB) assay as previously described [74]. In brief, 40 ml of each digested sample was reacted with 250 ml DMMB dye in triplicate, and absorbance at 540 and 595 nm was read immediately using a plate reader. Delta was calculated by subtracting 595 nm absorbance from 540 nm absorbance and plotted on a chondroitin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich 230699) standard curve. Data from these biochemical assays were analyzed for normal distribution using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test (α = 0.05). Alamar blue assays were analyzed with a parametric one-way ANOVA, while measures of DNA and GAG content were compared with the two-tailed Student t-tests (α = 0.05).

Result and discussion

Microstructure

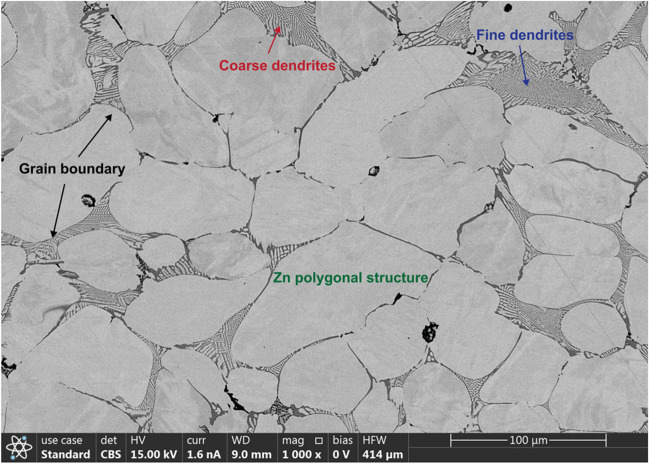

The cast Zn-0.8 Mg alloy showed large polygonal grains (80.23 µm in average) and Zn-Mg dendritic structure and the ratio of dendritic zone to grain was 11.12% (Fig. 2). At the dendritic structure of Zn, there were binary eutectic phases of the Zn and Mg surrounding the dendritic Zn. Previous research has shown that for different Zn-Mg alloys with Mg content ranging from 0 to 1 wt%, increasing the Mg content up to 0.8 wt% leads to such dendritic formation [24]. Previous study has also shown that increasing the Mg content in the range of 0wt% to 1wt% resulted in finer dendrite formation in Zn which indicates that higher content of Mg acts as a growth restrictor of Zn dendrite [63, 75]. Degradation studies showed better performance with finer Zn microstructure compared to coarser Zn microstructure. Furthermore, Qu et al. [76] studied samples with grain size ranging from 40 to 160 µm and found that the smaller grain size can decrease stress mismatch at the bone-implant interface reducing the biodegradation rate and helping prevent oxide cracking. The average grain size of samples evaluated was around 80.23 ± 10.72 µm. The finer grain size can be attributed to the rapid cooling in solidification phase using the AM mold which is consistent with previous studies [77, 78]. There are methods available for post-processing that can reduce the Zn grain size further down to 20 µm [79]. In addition, grain size also influences the strength of the specimen. Thus, controlling the amount of Mg in the Zn-Mg alloy allows for the control of microstructure to tailor the rate of biodegradation and the strength.

Fig. 2.

SEM image of Zn witness coupon showing the polygonal shapes of Zn grains and their grain boundaries. Representative coarse and fine dendritic regions are shown in red and blue color, respectively

Chemical composition

EDS testing revealed the elemental composition of Zn (92.5 wt%) and Mg (0.872 wt%). In particular, the Zn-Mg intermetallic was evident at the grain boundary in the dendritic region (Fig. 2). SEM analysis (Fig. 3) revealed the segregation of Mg in the dendritic region at the grain boundaries. This is due to the formation of Zn-Mg intermetallic which can inhibit the degradation process of the implant. The amount of Mg plays a critical role in the rate of biodegradation of the implant. Hammam et al. [24] showed that, increased Mg content results in faster degradation. This is attributed to the formation of Zn hopeite (Zn3(PO4)2.4H2O) on the surface from released Zn ions which is an insoluble compound, retarding the corrosion rate. Additionally, Mg ions released from the degradation process produce electrochemically inert compound like Mg hydroxyl carbonate (Mg2(OH2) CO3) on the surface that inhibits further degradation [80]. The higher amount of Mg resulted in forming a secondary intermetallic that resulted in diminishing the degradation-inhibiting effect of the Mg and the alloy. Although higher Mg content has shown to have faster degradation [24, 81], the Zn-Mg intermetallic segregation along the grain boundary lowers the biodegradation rate compared to pure Zn [24]. Also, it is postulated that the elevated carbon content was introduced during the casting phase within the foundry. There are trace amounts of aluminum (Al) which can also function as a grain growth inhibitor for Zn [82]. It is likely that Al has contributed to the smaller Zn grain size exhibited in the specimen. Furthermore, Al can lower the biodegradation rate of Zn. In summary, the material composition of the specimen is highly suitable for implants.

Fig. 3.

EDS analysis of a representative witness coupon. a SEM image. b EDS surface map showing the overlay of the materials. c Zn surface map. d Mg surface map; dominantly distributed in the dendritic region. e Al surface map. f Material composition (wt%)

Mechanical properties

The microhardness tests done on the solid samples (Fig. 4) revealed a hardness of 91.442 ± 7.67 HV for 1 N force. For context, the mean hardness of human bones varies from 33.30 HV to 43.82 HV, with the certain regions exhibiting hardness around 42.54 ± 5.59 HV [83, 84]. Higher hardness of the implant results in higher resistance to wear which prolongs the life of the implant [85, 86]. Micro indentation was used to calculate Young’s modulus of the specimens, and the samples showed values in the range of 93.613 ± 1.012 GPa. Previous research reported Young’s modulus of 97 ± 14 GPa which is similar to the results observed in this study [87]. The following Table 1 summarizes the properties of Zn-Mg alloy used in this study. It is possible that the microhardness test indentation captured the hardness of both the grain and the dendritic region. A nanohardness test will be appropriate to find the hardness of the grain and dendritic region.

Fig. 4.

a, b Sample indentation on the surface for measuring hardness. c Load vs depth graph shows loading curve of two representative samples

Table 1.

Mechanical properties of the samples

| Alloy composition | Hardness (HV) | Young’s modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Zn-0.8wt%Mg | 91.442 ± 7.67 | 93.613 ± 1.012 |

Fe and Mg are two of the most common biodegradable metals studied as implant materials. In comparison to Zn, Fe has a much higher Young’s modulus (210 GPa [88]). In addition, iron implants produce oxide in the body which can be toxic [89, 90]. Furthermore, it is preferable for orthopaedic implants to have modulus similar to natural human bone as mismatch in Young’s modulus between the materials can result in stress shielding [91, 92], which ultimately leads to bone resorption [93, 94] and unfavorable osseointegration [95, 96]. Young’s modulus of human bones ranges from 0.01 to 30 GPa [97, 98] which is lower when compared to Young’s modulus of Fe implant materials. Although Young’s modulus of Mg implant materials (42.5 ± 3.5 GPa [99]) is closer to human bone and half of Zn [66], multiple studies have shown that Mg degrades at a faster rate and oxidizes during the process, an undesirable quality for bone implants [100–102]. Thus, the combination of moderately high Young’s modulus and slower degradation rate attributed to the presence of Mg, as demonstrated in other studies, suggests that the Zn-Mg alloy is a better candidate for bone implant.

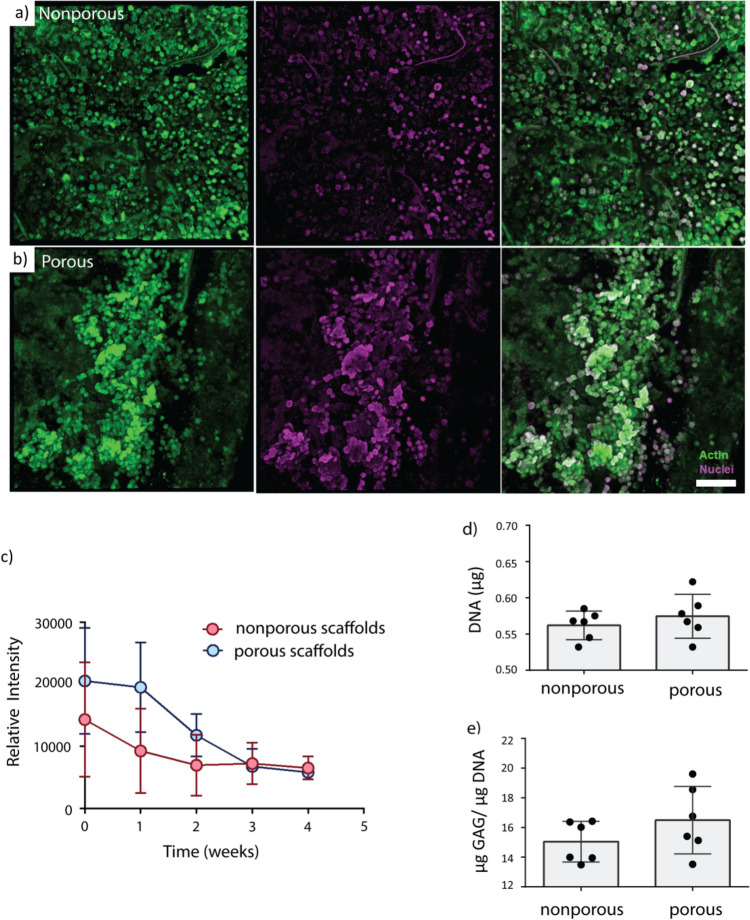

In vitro cell culture results

Cells robustly survived on the surface over the study. Confocal imaging in week 4 revealed that rounded mesenchymal stromal cells homogenously covered the entire surface of both solid and gyroid TPMS Zn-Mg scaffolds in a single cell layer (Fig. 5a). Due to the influence of the TPMS scaffolds’ large macroscopic pores (average diameter of 1.55 mm), MSCs were found in dense clusters on the scaffolds’ surface struts whereas MSCs were found to be evenly distributed on solid test coupons (Fig. 5b). No differences in cell morphology were observed between groups.

Fig. 5.

Representative confocal microscopy images for a solid and b TPMS samples. Cellular distribution was more uniform for solid samples compared to TPMS (scale bar = 100 microns). c Measures of metabolic activity via Alamar blue showed higher initial activity in the TPMS scaffolds that resolved by week 3. Measures of d DNA and e GAG content in the solid and TPMS samples showed no significant differences between groups

TPMS scaffolds had elevated levels of cell metabolism after initial seeding that became equivalent to solid scaffolds by week 3 which can be attributed to a larger surface area for more cells to attach. Based on the confocal microscopy images, the cells quickly covered the whole surface of the test coupons, proliferating over the first week of culture on solid samples and the first two weeks of culture on TPMS samples due to their larger surface area, and then just required maintenance metabolism, which led to overall decreases in metabolic activity over time. It is also likely that cells, which originally attached more interiorly on TPMS implants, perished over the first 2 weeks of culture, contributing to the reduction in cell metabolism observed on these scaffolds. Limited diffusion into the internal TPMS channels may have caused a decrease in live cell number towards the center of the TPMS scaffolds which can lead to equivalent metabolism on solid and TPMS scaffolds by week 3. Cell metabolism decreased in both solid and TPMS specimens over the course of 4 weeks (Fig. 5c).

Although no explicit live/dead assays were performed, which is certainly a limitation of the study in part due to the small number of samples available for testing, it has been established that a major driver of cell survival is the ability for those cells to access nutrients and rid their immediate environment of waste products. Previous work demonstrated that cells in the center of large scaffolds (8 mm diameter × 4.5 mm height) deposited less matrix overall in the center of these constructs due to low oxygen concentrations [103]. It has also been shown that cells are likely driven towards apoptosis in large scaffolds (10 mm diameter × 2.34 mm height) treated with the same volume of media as the TPMS scaffolds in this study due to low glucose diffusion towards the implants’ centers and the consumption of that glucose by more external cells. Given that the Zn-Mg coupons in this study are even larger (17.5 mm diameter × 60 mm height) than those used previously to characterize cell survival in vitro, we expected the effect of low oxygen and low glucose to be more pronounced.

No differences in DNA content or glycosaminoglycan content existed between solid and TPMS groups (Fig. 5d and e). Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content is a major component of cartilage tissue that can be produced by MSCs in various stages of chondrogenic differentiation. The observed lower content of GAG content indicates that these cells are most likely not differentiating into chondrocytes. Overall, cells on both scaffold types covered the entire surface by 4 weeks with similar morphologies and similar quantities of DNA and GAGs. These similarities can be attributed to the scaffolds’ identical compositions and surface textures.

There were a few limitations in this research which will be addressed in future studies. Overall, the sample sizes used in the experiments were relatively small (n = 3). This led to several issues. First, we believe that cell proliferation was more variable at earlier time points. Specifically, we think that proliferation in the TPMS group was likely higher at weeks 0–2. However, due to the limited number of samples, we were unable to perform proliferation analysis at multiple timepoints. Instead, we were limited to performing these assays at the end of the experiment, which limits our ability to characterize growth over time. The cell study only included a single cell type and specific alloy composition, which limits the generalizability of results for a wider range of Zn-Mg compositions and cell types. Additionally, a true control group, such as a 316L stainless steel group, was not included. Furthermore, there was trace amount of Ni present which has the potential to provoke immune response. In future work, studies that incorporate other TPMS structures and control materials need to be performed to better understand the relationships between structure and in vivo function of devices. Also, a better sterile environment will be used in the preparation of the alloy to avoid elements that have the potential to provoke immune response. Finally, this study did not consider bio-mechanical loading of implants (e.g., cadaver or sawbone constructs). Future work in this area will be critical to fully understand the interplay between fatigue mechanical loading, biodegradation of implants, and cellular responses.

Conclusion

In this study, a novel AM-augmented casting method was used to produce cast TPMS with biodegradable Zn-0.8 Mg alloy. Typically, TPMS structures are made from an AM process similar to the designs explored in this study. However, instead of using AM to directly manufacture the implant, casting molds were produced via AM (i.e., DLP) for indirect AM, i.e., AM-augmented casting of biodegradable Zn-Mg implants. The aim of this work was to validate this indirect AM process and explore the suitability of the cast parts to be used as orthopaedic implants. The SEM analysis revealed finer polygonal Zn microstructure with dendritic region, which is a positive indication of both higher biomechanical strength and slower biodegradation rate, which are two critical characteristics in an ideal biodegradable implant material. The EDS analysis confirmed the alloy composition, and the surface map showed the location of Mg segregates predominantly at the grain boundary resulting from the intermetallics of Zn and Mg. Micro indentation revealed nano-hardness and Young’s modulus within the normal range of implants designed with Mg and Fe, but closer to that of human bone than Fe. Cells were able to thrive on the surface of the fabricated implants. Although there were more viable cells on the TPMS structures than the solid structures shortly after cell seeding, there were no significant differences between groups by the 4-week endpoint. The hybrid manufacturing process for producing implants with Zn-0.8 Mg alloy resulted in parts having similar structural, mechanical, chemical, and cellular properties to traditional zinc implant material. Overall, this indirect AM-augmented casting process combines the design freedom of additive manufacturing with the reliability of casting, expanding the horizon for biodegradable implants.

Funding

This research work was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under CAREER Award 1944120, NIH/NIAMS P30AR069619 and R03AR082449.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wen X, Wang J, Pei X, Zhang X. Zinc-based biomaterials for bone repair and regeneration: mechanism and applications. J Mater Chem B. 2023;11:11405–25. 10.1039/D3TB01874A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Shalawi FD, Mohamed Ariff AH, Jung D-W, MohdAriffin MKA, Seng Kim CL, Brabazon D, Al-Osaimi MO. Biomaterials as implants in the orthopedic field for regenerative medicine: metal versus synthetic polymers. Polymers (Basel). 2023;15:2601. 10.3390/polym15122601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang H, Jia B, Zhang Z, Qu X, Li G, Lin W, Zhu D, Dai K, Zheng Y. Alloying design of biodegradable zinc as promising bone implants for load-bearing applications. Nat Commun. 2020;11:401. 10.1038/s41467-019-14153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li P, Dai J, Li Y, Alexander D, Čapek J, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Wan G, Han J, Yu Z, Li A. Zinc based biodegradable metals for bone repair and regeneration: bioactivity and molecular mechanisms. Mater Today Bio. 2024;25:100932. 10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y, Du T, Qiao A, Mu Y, Yang H. Zinc-based biodegradable materials for orthopaedic internal fixation. J Funct Biomater. 2022;13:164. 10.3390/jfb13040164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenwright J, A.E. Goodship. Controlled mechanical stimulation in the treatment of tibial fractures., Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989;36–47. [PubMed]

- 7.J. Kenwright, J. Richardson, J. Cunningham, S. White, A. Goodship, M. Adams, P. Magnussen, J. Newman, Axial movement and tibial fractures. A controlled randomised trial of treatment, J Bone Joint Surg Br 73-B (1991) 654–659. 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.2071654. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Goodship AE, Cunningham JL, Kenwright J. Strain rate and timing of stimulation in mechanical modulation of fracture healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;355S:S105–15. 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boerckel JD, Kolambkar YM, Stevens HY, Lin ASP, Dupont KM, Guldberg RE. Effects of in vivo mechanical loading on large bone defect regeneration. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1067–75. 10.1002/jor.22042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott AM, Mason DE, Lin ASP, Guldberg RE, Boerckel JD. Influence of structural load-bearing scaffolds on mechanical load- and BMP-2-mediated bone regeneration. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2016;62:169–81. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pietrzak WS, Eppley BL. Resorbable polymer fixation for craniomaxillofacial surgery. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2000;11:575–85. 10.1097/00001665-200011060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabir H, Munir K, Wen C, Li Y. Recent research and progress of biodegradable zinc alloys and composites for biomedical applications: biomechanical and biocorrosion perspectives. Bioact Mater. 2021;6:836–79. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pogorielov M, Husak E, Solodivnik A, Zhdanov S. Magnesium-based biodegradable alloys: degradation, application, and alloying elements. Interv Med Appl Sci. 2017;9:27–38. 10.1556/1646.9.2017.1.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh Z, Najeeb S, Khurshid Z, Verma V, Rashid H, Glogauer M. Biodegradable materials for bone repair and tissue engineering applications. Materials. 2015;8:5744–94. 10.3390/ma8095273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuai C, Li S, Peng S, Feng P, Lai Y, Gao C. Biodegradable metallic bone implants. Mater Chem Front. 2019;3:544–62. 10.1039/C8QM00507A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dorozhkin SV. Calcium orthophosphate coatings on magnesium and its biodegradable alloys. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:2919–34. 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zberg B, Uggowitzer PJ, Löffler JF. MgZnCa glasses without clinically observable hydrogen evolution for biodegradable implants. Nat Mater. 2009;8:887–91. 10.1038/nmat2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sing NB, Mostavan A, Hamzah E, Mantovani D, Hermawan H. Degradation behavior of biodegradable Fe35Mn alloy stents. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2015;103:572–7. 10.1002/jbm.b.33242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowen PK, Guillory RJ, Shearier ER, Seitz J-M, Drelich J, Bocks M, Zhao F, Goldman J. Metallic zinc exhibits optimal biocompatibility for bioabsorbable endovascular stents. Mater Sci Eng C. 2015;56:467–72. 10.1016/j.msec.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu Q, Sun X, Zhao J, Zhao L, Chen Y, Fan L, Li Z, Sun Y, Wang M, Wang F. The effects of zinc deficiency on homeostasis of twelve minerals and trace elements in the serum, feces, urine and liver of rats. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2019;16:73. 10.1186/s12986-019-0395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schinhammer M, Hänzi AC, Löffler JF, Uggowitzer PJ. Design strategy for biodegradable Fe-based alloys for medical applications☆. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:1705–13. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaishankar M, Tseten T, Anbalagan N, Mathew BB, Beeregowda KN. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2014;7:60–72. 10.2478/intox-2014-0009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong X, Cai W, Lin J, Wang K, Jin L, Shi Z, Zhang D, Lin J, Li Y, Dargusch M, Wen C. Biodegradable Zn−3Mg−0.7Mg2Si composite fabricated by high-pressure solidification for bone implant applications. Acta Biomater. 2021;123:407–17. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammam RE, Abdel-Gawad SA, Moussa ME, Shoeib M, El-Hadad S. Study of microstructure and corrosion behavior of cast Zn–Al–Mg alloys. Int J Metalcast. 2023. 10.1007/s40962-022-00944-0. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shao X, Wang X, Xu F, Dai T, Zhou JG, Liu J, Song K, Tian L, Liu B, Liu Y. In vivo biocompatibility and degradability of a Zn–Mg–Fe alloy osteosynthesis system. Bioact Mater. 2022;7:154–66. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kannan MB, Moore C, Saptarshi S, Somasundaram S, Rahuma M, Lopata AL. Biocompatibility and biodegradation studies of a commercial zinc alloy for temporary mini-implant applications. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15605. 10.1038/s41598-017-15873-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng Y, Chen H. Aberrance of zinc metalloenzymes-induced human diseases and its potential mechanisms. Nutrients. 2021;13:4456. 10.3390/nu13124456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang S, Zhang X, Zhao C, Li J, Song Y, Xie C, Tao H, Zhang Y, He Y, Jiang Y, Bian Y. Research on an Mg–Zn alloy as a degradable biomaterial. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:626–40. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang H, Liu H, Wang L, Yan K, Li Y, Jiang J, Ma A, Xue F, Bai J. Revealing the effect of minor Ca and Sr additions on microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of Zn-0.6 Mg alloy during multi-pass equal channel angular pressing. J Alloys Compd. 2020;844:155923. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155923. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jarzębska A, Bieda M, Kawałko J, Rogal Ł, Koprowski P, Sztwiertnia K, Pachla W, Kulczyk M. A new approach to plastic deformation of biodegradable zinc alloy with magnesium and its effect on microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater Lett. 2018;211:58–61. 10.1016/j.matlet.2017.09.090. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao S, Seitz J-M, Eifler R, Maier HJ, Guillory RJ, Earley EJ, Drelich A, Goldman J, Drelich JW. Zn-Li alloy after extrusion and drawing: structural, mechanical characterization, and biodegradation in abdominal aorta of rat. Mater Sci Eng, C. 2017;76:301–12. 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li HF, Xie XH, Zheng YF, Cong Y, Zhou FY, Qiu KJ, Wang X, Chen SH, Huang L, Tian L, Qin L. Development of biodegradable Zn-1X binary alloys with nutrient alloying elements Mg Ca and Sr. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10719. 10.1038/srep10719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue P, Ma M, Li Y, Li X, Yuan J, Shi G, Wang K, Zhang K. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and in vitro corrosion behavior of biodegradable Zn-1Fe-xMg alloy. Materials. 2020;13:4835. 10.3390/ma13214835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gong H, Wang K, Strich R, Zhou JG. In vitro biodegradation behavior, mechanical properties, and cytotoxicity of biodegradable Zn–Mg alloy. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2015;103:1632–40. 10.1002/jbm.b.33341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang L, Li X, Yang L, Zhu X, Wang M, Song Z, Liu HH, Sun W, Dong R, Yue J. Effect of Mg contents on the microstructure, mechanical properties and cytocompatibility of degradable Zn-0.5Mn-xMg alloy. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14:195. 10.3390/jfb14040195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krieg R, Vimalanandan A, Rohwerder M. Corrosion of Zinc and Zn-Mg alloys with varying microstructures and magnesium contents. J Electrochem Soc. 2014;161:C156–61. 10.1149/2.103403jes. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu X, Sun J, Qiu K, Yang Y, Pu Z, Li L, Zheng Y. Effects of alloying elements (Ca and Sr) on microstructure, mechanical property and in vitro corrosion behavior of biodegradable Zn–1.5Mg alloy. J Alloys Compd. 2016;664:444–52. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.10.116. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kubásek J, Pospíšilová I, Vojtěch D, Jablonská E, Ruml T. Structural, mechanical and cytotoxicity characterization of as-cast biodegradable Zn-xMg (x= 0.8–8.3%) alloys. Mater Tehnol. 2014;48:623–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feller L, Jadwat Y, Khammissa RAG, Meyerov R, Schechter I, Lemmer J. Cellular responses evoked by different surface characteristics of intraosseous titanium implants. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–8. 10.1155/2015/171945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.PeŠŠková V, Kubies D, Hulejová H, Himmlová L. The influence of implant surface properties on cell adhesion and proliferation. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2007;18:465–73. 10.1007/s10856-007-2006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Brien FJ, Harley BA, Yannas IV, Gibson LJ. The effect of pore size on cell adhesion in collagen-GAG scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2005;26:433–41. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Shen Y, Sun Y, Yang J, Gong Y, Wang K, Zhang Z, Chen X, Bai L. Design and mechanical testing of porous lattice structure with independent adjustment of pore size and porosity for bone implant. J Market Res. 2022;18:3240–55. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.du Plessis A, Yadroitsava I, Yadroitsev I, le Roux S, Blaine D. Numerical comparison of lattice unit cell designs for medical implants by additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2018;13:266–81. 10.1080/17452759.2018.1491713. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Catchpole-Smith S, Sélo RRJ, Davis AW, Ashcroft IA, Tuck CJ, Clare A. Thermal conductivity of TPMS lattice structures manufactured via laser powder bed fusion. Addit Manuf. 2019;30:100846. 10.1016/j.addma.2019.100846. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L, Hu Z, Wang MY, Feih S. Hierarchical sheet triply periodic minimal surface lattices: design, geometric and mechanical performance. Mater Des. 2021;209:109931. 10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109931. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang L, Feih S, Daynes S, Chang S, Wang MY, Wei J, Lu WF. Energy absorption characteristics of metallic triply periodic minimal surface sheet structures under compressive loading. Addit Manuf. 2018;23:505–15. 10.1016/j.addma.2018.08.007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tilton M, Borjali A, Isaacson A, Varadarajan KM, Manogharan GP. On structure and mechanics of biomimetic meta-biomaterials fabricated via metal additive manufacturing. Mater Des. 2021;201:109498. 10.1016/j.matdes.2021.109498. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tilton M, Borjali A, Griffis JC, Varadarajan KM, Manogharan GP. Fatigue properties of Ti-6Al-4V TPMS scaffolds fabricated via laser powder bed fusion. Manuf Lett. 2023;37:32–8. 10.1016/j.mfglet.2023.06.005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tilton M, Jacobs E, Overdorff R, AstudilloPotes M, Lu L, Manogharan G. Biomechanical behavior of PMMA 3D printed biomimetic scaffolds: effects of physiologically relevant environment. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2023;138:105612. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2022.105612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castro, Pires, Santos, Gouveia, Fernandes. Permeability versus design in TPMS scaffolds. Materials. 2019;12:1313. 10.3390/ma12081313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Feng J, Fu J, Yao X, He Y. Triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) porous structures: from multi-scale design, precise additive manufacturing to multidisciplinary applications. Int J Extreme Manuf. 2022;4:022001. 10.1088/2631-7990/ac5be6. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li D, Liao W, Dai N, Xie YM. Comparison of mechanical properties and energy absorption of sheet-based and strut-based gyroid cellular structures with graded densities. Materials. 2019;12:2183. 10.3390/ma12132183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Timercan A, Sheremetyev V, Brailovski V. Mechanical properties and fluid permeability of gyroid and diamond lattice structures for intervertebral devices: functional requirements and comparative analysis. Sci Technol Adv Mater. 2021;22:285–300. 10.1080/14686996.2021.1907222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rovetta R, Ginestra P, Ferraro RM, Zohar-Hauber K, Giliani S, Ceretti E. Building orientation and post processing of Ti6Al4V produced by laser powder bed fusion process. J Manuf Mater Process. 2023;7:43. 10.3390/jmmp7010043. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu Y, Liu J, Kang L, Tian J, Zhang X, Hu J, Huang Y, Liu F, Wang H, Wu Z. An overview of 3D printed metal implants in orthopedic applications: present and future perspectives. Heliyon. 2023;9:e17718. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hernández-Rodríguez MAL, Mercado-Solís RD, Pérez-Unzueta AJ, Martinez-Delgado DI, Cantú-Sifuentes M. Wear of cast metal–metal pairs for total replacement hip prostheses. Wear. 2005;259:958–63. 10.1016/j.wear.2005.02.080. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thomé E, Lee HJ, de Sartori IAM, Trevisan RL, Luiz J, Tiossi R. A randomized controlled trial comparing interim acrylic prostheses with and without cast metal base for immediate loading of dental implants in the edentulous mandible. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2015;26:1414–20. 10.1111/clr.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohammadi S, Esposito M, Wictorin L, Aronsson B-O, Thomsen P. Bone response to machined cast titanium implants. J Mater Sci. 2001;36:1987–93. 10.1023/A:1017518629057. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dong Z, Han C, Zhao Y, Huang J, Ling C, Hu G, Wang Y, Wang D, Song C, Yang Y. Role of heterogenous microstructure and deformation behavior in achieving superior strength-ductility synergy in zinc fabricated via laser powder bed fusion. Int J Extreme Manuf. 2024;6:045003. 10.1088/2631-7990/ad3929. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shuai C, Li D, Yao X, Li X, Gao C. Additive manufacturing of promising heterostructure for biomedical applications. Int J Extreme Manuf. 2023;5:032012. 10.1088/2631-7990/acded2. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montani M, Demir AG, Mostaed E, Vedani M, Previtali B. Processability of pure Zn and pure Fe by SLM for biodegradable metallic implant manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp J. 2017;23:514–23. 10.1108/RPJ-08-2015-0100. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han C, Huang J, Ye X, Liu B, Dong Z, Yang Y, Gao J, Yang K, Chen G. Microstructure evolution and ductility improvement of additively manufactured biodegradable zinc–magnesium alloys via annealing. Int J Bioprint. 2024;0:3034. 10.36922/ijb.3034.

- 63.Hammam RE, Abdel-Gawad SA, Moussa ME, Shoeib M, El-Hadad S. Study of microstructure and corrosion behavior of cast Zn–Al–Mg alloys. Int J Metalcast. 2023;17:2794–807. 10.1007/s40962-022-00944-0. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moussa ME, El-Hadad S, Shoeib M. Influence of dendritic fragmentation through Mg addition on the electrochemical characteristics of Zn–0.5 wt% Al alloy. Int J Metal. 2022;16:1034–44. 10.1007/s40962-021-00662-z. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yu J, Wang L, Wang Y, Cao X, Li Y, Xing B, Lu L, Cheng W, Wang H, Shin KS, Vedani M. Corrosion behavior of as-cast magnesium-4 % zinc alloys in simulated body fluid solution: the influence of minor calcium and manganese addition. Materwiss Werksttech. 2022;53:819–34. 10.1002/mawe.202200025. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tong X, Wang H, Zhu L, Han Y, Wang K, Li Y, Ma J, Lin J, Wen C, Huang S. A biodegradable in situ Zn–Mg2Ge composite for bone-implant applications. Acta Biomater. 2022;146:478–94. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moreno L, Matykina E, Yasakau KA, Blawert C, Arrabal R, Mohedano M. As-cast and extruded Mg Zn Ca systems for biodegradable implants: characterization and corrosion behavior. J Magn Alloys. 2023;11:1102–20. 10.1016/j.jma.2023.02.001. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li C, Huang T, Liu Z. Effects of thermomechanical processing on microstructures, mechanical properties, and biodegradation behaviour of dilute Zn–Mg alloys. J Market Res. 2023;23:2940–55. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.01.203. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang K, Tong X, Lin J, Wei A, Li Y, Dargusch M, Wen C. Binary Zn–Ti alloys for orthopedic applications: corrosion and degradation behaviors, friction and wear performance, and cytotoxicity. J Mater Sci Technol. 2021;74:216–29. 10.1016/j.jmst.2020.10.031. [Google Scholar]

- 70.ASTM E3 Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens, E3 Standard Guide for Preparation of Metallographic Specimens, (2017). https://www.astm.org/e0003-11r17.html (accessed April 11, 2024).

- 71.ASTM E2546 Standard Practice for Instrumented Indentation Testing, E2546 Standard Practice for Instrumented Indentation Testing, (2015). https://www.astm.org/e2546-15.html (accessed April 6, 2024).

- 72.Meredith N, Sherriff M, Setchell DJ, Swanson SAV. Measurement of the microhardness and Young’s modulus of human enamel and dentine using an indentation technique. Arch Oral Biol. 1996;41:539–45. 10.1016/0003-9969(96)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fainor M, Mahindroo S, Betz KR, Augustin J, Smith HE, Mauck RL, Gullbrand SE. A tunable calcium phosphate coating to drive in vivo osseointegration of composite engineered tissues. Cells Tissues Organs. 2023;212:381–96. 10.1159/000528965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Farndale RW, Sayers CA, Barrett AJ. A direct spectrophotometric microassay for sulfated glycosaminoglycans in cartilage cultures. Connect Tissue Res. 1982;9:247–8. 10.3109/03008208209160269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Farahany S, Tat LH, Hamzah E, Bakhsheshi-Rad HR, Cho MH. Microstructure development, phase reaction characteristics and properties of quaternary Zn-0.5Al-0.5Mg-xBi hot dipped coating alloy under slow and fast cooling rates. Surf Coat Technol. 2017;315:112–22. 10.1016/j.surfcoat.2017.01.074. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Qu Z, Liu L, Deng Y, Tao R, Liu W, Zheng Z, Zhao M-C. Relationship between biodegradation rate and grain size itself excluding other structural factors caused by alloying additions and deformation processing for pure Mg. Materials. 2022;15:5295. 10.3390/ma15155295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O. Wick, The control of the grain size of zinc, Bachelors Theses and Reports, 1928 - 1970 (1936). https://digitalcommons.mtech.edu/bach_theses/67 (accessed May 13, 2024).

- 78.Bons LJ. Method of grain refining zinc. 1965.

- 79.Bednarczyk W, Wątroba M, Kawałko J, Bała P. Can zinc alloys be strengthened by grain refinement? A critical evaluation of the processing of low-alloyed binary zinc alloys using ECAP. Mater Sci Eng: A. 2019;748:357–66. 10.1016/j.msea.2019.01.117. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mostaed E, Sikora-Jasinska M, Drelich JW, Vedani M. Zinc-based alloys for degradable vascular stent applications. Acta Biomater. 2018;71:1–23. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prosek T, Nazarov A, Bexell U, Thierry D, Serak J. Corrosion mechanism of model zinc–magnesium alloys in atmospheric conditions. Corros Sci. 2008;50:2216–31. 10.1016/j.corsci.2008.06.008. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huang T, Liu Z, Wu D, Yu H. Microstructure, mechanical properties, and biodegradation response of the grain-refined Zn alloys for potential medical materials. J Market Res. 2021;15:226–40. 10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.08.024. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yin B, Guo J, Wang J, Li S, Liu Y, Zhang Y. Bone material properties of human phalanges using vickers indentation. Orthop Surg. 2019;11:487–92. 10.1111/os.12455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu W, Zhu Y, Chen W, Li S, Yin B, Wang J, Zhang X, Liu G, Hu Z, Zhang Y. Bone hardness of different anatomical regions of human radius and its impact on the pullout strength of screws. Orthop Surg. 2019;11:270–6. 10.1111/os.12436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Skjöldebrand C, Tipper JL, Hatto P, Bryant M, Hall RM, Persson C. Current status and future potential of wear-resistant coatings and articulating surfaces for hip and knee implants. Mater Today Bio. 2022;15:100270. 10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhao T, Li Y, Liu Y, Zhao X. Nano-hardness, wear resistance and pseudoelasticity of hafnium implanted NiTi shape memory alloy. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2012;13:174–84. 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ledbetter HM. Elastic properties of zinc: a compilation and a review. J Phys Chem Ref Data. 1977;6:1181–203. 10.1063/1.555564. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Benito JA, Jorba J, Manero JM, Roca A. Change of Young’s modulus of cold-deformed pure iron in a tensile test. Metall Mater Trans A. 2005;36:3317–24. 10.1007/s11661-005-0006-6. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Badhe RV, Akinfosile O, Bijukumar D, Barba M, Mathew MT. Systemic toxicity eliciting metal ion levels from metallic implants and orthopedic devices – a mini review. Toxicol Lett. 2021;350:213–24. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu L, Wen W, Wang X, Huang D, Cao J, Qi X, Shen S. Ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles cause significant toxicity by specifically inducing acute oxidative stress to multiple organs. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2022;19:24. 10.1186/s12989-022-00465-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Piao C, Wu D, Luo M, Ma H. Stress shielding effects of two prosthetic groups after total hip joint simulation replacement. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9:71. 10.1186/s13018-014-0071-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brizuela A, Herrero-Climent M, Rios-Carrasco E, Rios-Santos J, Pérez R, Manero J, Gil Mur J. Influence of the elastic modulus on the osseointegration of dental implants. Materials. 2019;12:980. 10.3390/ma12060980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shi L, Shi L, Wang L, Duan Y, Lei W, Wang Z, Li J, Fan X, Li X, Li S, Guo Z. The improved biological performance of a novel low elastic modulus implant. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55015. 10.1371/journal.pone.0055015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Heary RF, Parvathreddy N, Sampath S, Agarwal N. Elastic modulus in the selection of interbody implants. J Spine Surg. 2017;3:163–7. 10.21037/jss.2017.05.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kunii T, Mori Y, Tanaka H, Kogure A, Kamimura M, Mori N, Hanada S, Masahashi N, Itoi E. Improved osseointegration of a TiNbSn alloy with a low Young’s modulus treated with anodic oxidation. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13985. 10.1038/s41598-019-50581-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dai X, Zhang X, Xu M, Huang Y, Heng BC, Mo X, Liu Y, Wei D, Zhou Y, Wei Y, Deng X, Deng X. Synergistic effects of elastic modulus and surface topology of Ti-based implants on early osseointegration. RSC Adv. 2016;6:43685–96. 10.1039/C6RA04772F. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Morgan EF, Keaveny TM. Dependence of yield strain of human trabecular bone on anatomic site. J Biomech. 2001;34:569–77. 10.1016/S0021-9290(01)00011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ciarelli MJ, Goldstein SA, Kuhn JL, Cody DD, Brown MB. Evaluation of orthogonal mechanical properties and density of human trabecular bone from the major metaphyseal regions with materials testing and computed tomography. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:674–82. 10.1002/jor.1100090507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sumitomo T, Cáceres CH, Veidt M. The elastic modulus of cast Mg–Al–Zn alloys. J Light Met. 2002;2:49–56. 10.1016/S1471-5317(02)00013-5. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Choudhary L, Singh Raman RK. Magnesium alloys as body implants: fracture mechanism under dynamic and static loadings in a physiological environment. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:916–23. 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hänzi AC, Gerber I, Schinhammer M, Löffler JF, Uggowitzer PJ. On the in vitro and in vivo degradation performance and biological response of new biodegradable Mg–Y–Zn alloys. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:1824–33. 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Singh Raman RK, Choudhary L. Cracking of magnesium-based biodegradable implant alloys under the combined action of stress and corrosive body fluid: a review. Emerg Mater Res. 2013;2:219–28. 10.1680/emr.13.00033. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buckley CT, Meyer EG, Kelly DJ. The influence of construct scale on the composition and functional properties of cartilaginous tissues engineered using bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2012;18:382–96. 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.