Abstract

Cancer represents a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Definitive chemotherapy, surgery and radiotherapy treatment have not improved the “5-year survival period” and have shown recurrence. Currently, cancer immunotherapy is reported to be a promising therapeutic modality that aims to potentiate immune response against cancer by employing immune checkpoint inhibitors, cancer vaccines and immunomodulators. Inhibition of immune checkpoints such as PD-1/PDL1, CTLA and TIM molecules using monoclonal antibodies, ligands or both are proven to be the most successful anticancer immunotherapy. But the application of immunotherapy involves critical challenges such as non-responsiveness and systemic toxicity due to the administration of high dose. To mitigate the above challenges, nanomaterial-based delivery and therapy have been adopted to inhibit the immune checkpoints and induce an anticancer immune response. Specifically, mesoporous silica-based materials for cancer therapy are shown to be versatile materials for the above purpose. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) based cancer immunotherapy overcomes numerous challenges and offers novel strategies for improving conventional immunotherapies. MSN has a high surface area, porosity and biocompatibility; it also has natural immune-adjuvant properties, which have been reported to be the best candidate material for immunotherapeutic delivery. This review will focus on the use of MSN as carriers for delivering immune checkpoint inhibitors and their efficacy in cancer combination therapy.

Keywords: Mesoporous silica nanoparticles, Cancer immunotherapy, Immune-checkpoint inhibitor, PD1/PDL1, CTLA

Introduction to immune response

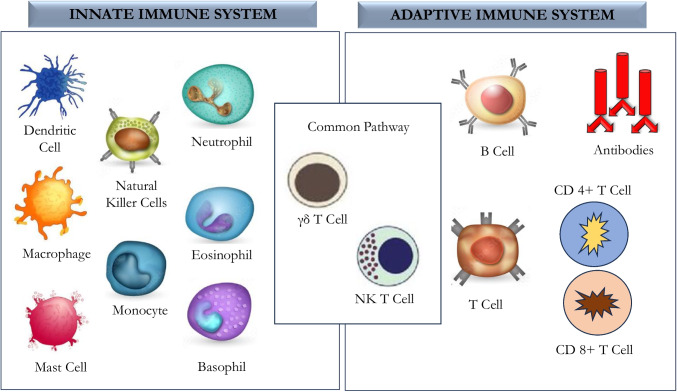

The immune system involves many potent effector mechanisms that can disrupt microbial cells and remove both allergic and toxic substances. The critical feature of the immune system is its ability to detect the structural characteristics of a pathogen or an allergic substance enabling it to mark it as distinct from host cells. Immune response has a self-tolerance capacity, which helps them to avoid destroying self-tissues. Negligence of this self-tolerance property can lead to autoimmune diseases [1]. The immune system consists of innate arms that are non-specific and adaptive/acquired arms that are highly specific. The innate immune system includes saliva, tears, skin barriers, complement proteins, cytokines, and other cells encompassing basophils, neutrophils, eosinophils, macrophages, monocytes, natural killer cells (NK), RBC, platelets and epithelial and endothelial cells. Antigen-presenting cells (APC) of innate immunity include macrophages and dendritic cells that phagocytose and present antigens to immune cells through surface receptors called major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules [2]. APC responds to antigens through cytokine secretion for recruiting and activating a complex network of immune cells, including NK cells, mast cells, phagocytic cells (macrophage, neutrophils), basophils, and eosinophils, towards the site of action to boost host immune response. The innate response also includes soluble proteins and small bioactive molecules in biological fluids released from the cells once activated. These include cytokines to regulate the functioning of other cells, chemokines for the attraction and movement of leukocytes, lipid mediators for inflammation, bioactive amines and enzymes that are involved in tissue inflammation. The innate system also employs cytoplasmic proteins and membrane-bound receptors aiding in molecular binding patterns expressed on the surface of invading microbes [3].

An adaptive immune response is developed over a period by acquiring training by constant exposure to foreign and defective proteins. A salient feature of adaptive immune response is their ability to manifest the immune memory and provide the most effective response against toxins and pathogens with specificity. They have antigen-specific receptors expressed on the surface of B-lymphocytes and release antibodies against proteins of the pathogen. These antigen-specific receptors are encoded by genes assembled by germline elements, forming both TCR (T cell response and immunoglobulin) genes. Thus, the innate and adaptive immune response is the two separate arms of the host response, yet, they act in concert; even though there is a difference in their mechanism of action, the synergy between them is essential. Immune cells such as NKT cells and special T cells (γδ-T cells) bridge the innate and adaptive immune system to act in concert for effective immune responses (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the immune system also encompasses negative regulators, including regulatory T cells and immune checkpoint molecules. These cells and molecules aid in controlling excessive damage caused by inflammation and thus lead to a protective immune response [2, 3].

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of cellular components of the innate, adaptive immune system and the bridging cells of the two arms

Immune response to cancer

Cancer is characterised by uncontrolled cell proliferation in any tissue due to accumulated genetic alterations and loss of normal cellular regulatory processes [4]. These events are reflected as an expression in the form of neoantigens that attach as peptides (from neoantigen) to MHC I molecules on the surface of cancer cells. These cancer-specific peptide MHC class I complexes are then recognised by CD8 + T cells [5]. Although T cell response is initiated, they rarely provide protective immunity. This is due to the evolving nature of cancer cells that express neoplastic antigens, thus avoiding detection and attacks of immune cells [6]. Negative regulators of T cell responses by tumour tissue (immunosuppressive function) through checkpoint molecules’ expression clearly explain the failure of tumour immune surveillance in many patients. Immune response in cancer reflects a set of regulated events and targeting them has led to the development of new drugs and the implementation of clinical strategies [7].

Anticancer immune response

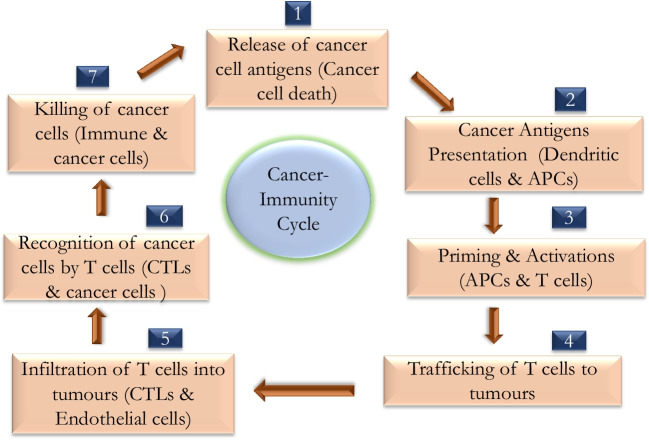

Anticancer immune response leading to the effective killing of cancer cells requires a sequential series of events to proceed and expand iteratively (Fig. 2) called the cancer-immunity cycle. In step 1 of the cancer-immunity cycle, neoantigens produced by mutagenesis are released and captured by APC (such as DCs) for processing. To yield an anticancer T cell response, it is accompanied by signals from APC that amplify immunity to the tumour antigens by certain immunogenic signs [8]. Such immunogenic signs include proinflammatory cytokines and protein factors released from dying tumour cells (Table 1). DCs present captured and processed tumour antigens on MHC II molecules to T cells (step 2), resulting in priming and activating effector T cell responses against the cancer-specific antigens (step 3). The nature of the immune response is determined at this stage, with a critical balance that represents the ratio of T effector cells with T regulatory cells that is vital in determining the outcome. Later, the activated effector T cells traffic to (step 4) and finally infiltrate the tumour bed (step 5), specifically recognising and binding to cancer cells by the interaction between its receptor (TCR) and its cognate antigen bound to MHC I (step 6), and kill their target cancer cell (step 7). The killing of cancer cell releases additional tumour-associated antigen (step 1 repeats), increasing the breadth and depth of response by repeating cyclical steps (Table 1). In cancer patients, the cancer-immunity cycle does not happen optimally. Tumour antigens may not be detected, DCs and T cells may treat antigens as self rather than foreign, thereby activating T regulatory cell responses than effector T cell responses, T cells may not correctly home to tumours or may be inhibited from infiltrating the tumour, or (most importantly) factors in the tumour microenvironment may suppress those effector cells that are produced [8]. Attempts to activate or introduce cancer antigen-specific T cells and to stimulate the proliferation of these cells led to minimal or negligible anticancer immune responses. Most efforts involved therapeutic vaccines because vaccines are easy to deploy and historically represented as an approach with significant benefits [9]. However, cancer vaccines are limited on two accounts. First, immunizing humans to achieve potent cytotoxic T cell responses is still a challenge.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of cancer-immunity cycle. The cycle is divided into seven major steps which starts with the release of antigens from the cancer cell and ends with the killing of cancer cells

Table 1.

List of seven major steps involved in the generation of immune response against cancer with their stimulators and inhibitors

| Steps | ( +) Stimulators | (-) Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|

| Release of cancer antigens | Immunogenic and necrotic cell death | Tolerogenic or apoptotic cell death |

| Cancer antigen presentation | Proinflammatory cytokines (eg. TNF-a, IL-1, IFN-a) and immune cell factors (CD40L/CD40). Endogenous adjuvants released from dying tumours: CDN (STING) ligand, ATP, and HMGB1. Gut microbiome products: TLR ligands | IL-10, IL-4, and IL-13 |

| Priming and activation |

CD28: B7.1 and CD137(4-1BB)/CD137L OX40: OX40L, CD27: CD70, HVEM, GITR, IL-2 and IL-12 |

CTLA4: B7.1 and PD-L1: PD-1 PD-L1: B7.1 and prostaglandins |

| Trafficking of T cells to tumours | CX3CL1, CXCL9, CXCL10 and CCL5 | - |

| Infiltration of T cells to tumours | LFA1: ICAM1 and selectins | VEGF and endothelin B receptor |

| Recognition of cancer cells by T cells | T cell receptor | Reduced peptide MHC expression on cancer cells |

| Killing of cancer cells | IFN-gamma and T cell granule content |

PD-L1: PD-1 and PD-L1: B7.1 TIM-3: Phospholipids, BTLA, VISTA, LAG-3, IDO, arginase and MICA: MICB, B7-H4 and TGF-B |

This limitation reflects continued uncertainties concerning the identities of antigens, how to use them, their mode of delivery and the types of adjuvants required [9]. Second, the presence of immunostatic protein in TME may disable antitumor immune responses before clinically relevant tumour killing can occur. Thus, when these negative signals are in place, the prospects of success for vaccine-based approaches are likely to be limited.

Immunotherapeutic modalities for cancer

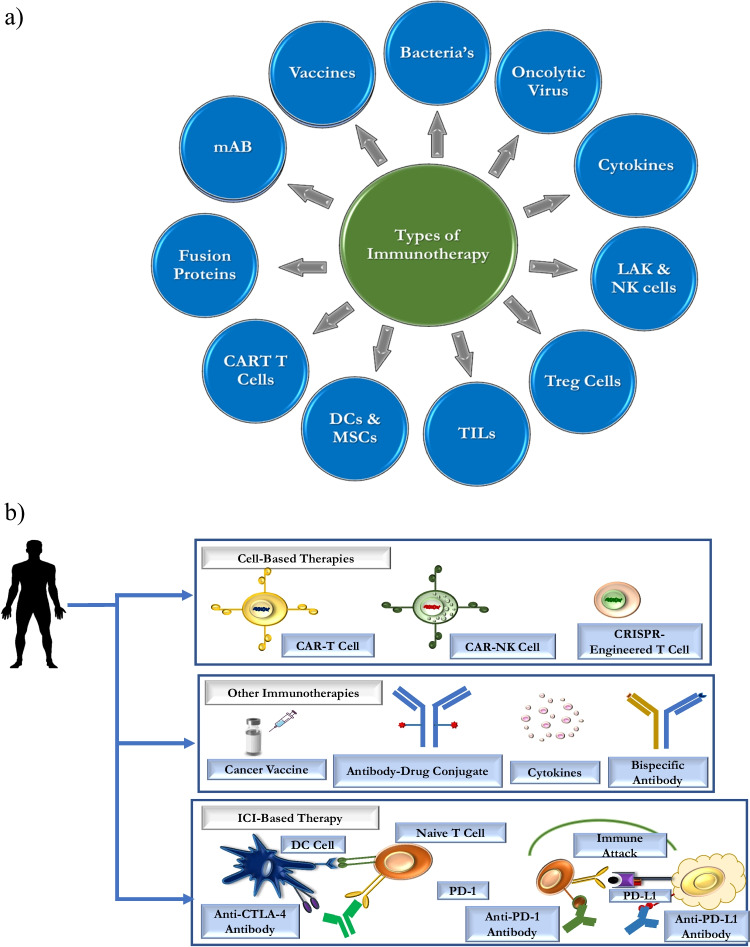

Immunotherapy is a treatment modality wherein the immune system is activated in order to eliminate the cancer cells. One of the mechanisms for cancer growth and spread is the failure of the immune cells and their components to recognise cancer cell and eliminate it. Hence, strategies to train the immune cells to recognise cancer cells, kill them and strategies to block the immunosuppressive action of cancer cells are used (Fig. 3). They show better therapeutic outcomes compared to conventional cancer therapy [10]. The following are the different modes by which immune stimulation against cancer is being achieved:

Bacteria-based immunotherapy: Certain types of cancer are treated with the administration of bacterial pathogens or their products enabling the host to stimulate immune cells against cancer tissue. For instance, Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens are used for the treatment of sarcoma, lymphoma and testis cancer, and non-virulent mycobacterial strain, BCG is reported to be effective in the treatment of lung and renal carcinomas [11].

Oncolytic viruses (OVs)–based immunotherapy: The use of therapeutic viruses is increasing for antitumoral therapy. An oncolytic virus has the capability of attacking tumour cells and enhances immunogenic cell death (ICD) as well as host immunity [12].

Vaccine-based immunotherapy: Therapeutic vaccines containing cancer tissue antigens have been reported to induce anti-cancer immune responses [13].

Monoclonal antibody (mAB)–based immunotherapy: Antibodies against a single epitope of cancer antigen are administered to stimulate immune cell–mediated cancer cell death [14].

Fusion proteins: Interleukin-2 (IL-2), Interferons (IFNs) and GM-CSF are the commonly available fusion proteins for human therapy. These proteins activate immune cells to respond against cancer tissue [15].

Immune cell–based therapy: In this type of intervention, a specific type of immune cell (dendritic cell, T Cell, NK cell) is taken from a cancer patient's blood and they are trained or stimulated in a lab against the cancer antigen and then administered back into the patient. These activated immune cells will easily recognise and will be equipped to eliminate cancer cells [16].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI)–based therapy: Here, inhibitors in the form of antibodies or cells (CART T cells) against immunosuppressive molecules are administered to mitigate the suppression of immune cells [17].

Fig. 3.

Schema showing different modalities of immunotherapies used against cancers. a Represents types of immunotherapies and b represents approaches of cancer immunotherapy based on cell-based therapy, vaccines, and immune checkpoint blockade therapy

Immune checkpoints

Immune checkpoints (IC) are a collection of regulatory pathways built into immune systems exhibiting properties of negative/positive regulators, they are essential for the maintenance of self-tolerance in the prevention of autoimmunity (Fig. 3) [18] and eliciting effective response against pathogenic protein antigens. Some tumours can evade host immunosurveillance and progress through different mechanisms including dysregulation of immune checkpoint expression and also activation of immune checkpoint pathways suppressing anti-tumour immune responses. IC can control the effector T cells and natural killer cell responses by multiple mechanisms. However, ICs have well-defined ligands for suppressing the function of T cells. The two types (Table 2) of ICs are (i) stimulatory (also called accelerator) and (ii) inhibitory (brake) checkpoints. [19] Stimulatory ICs include CD28 [20], ICOS [21], OX-40 (TNFRSF4) [22] and 4-1BB (TNFRSF9) [23] impacting the anticancer responses. While inhibitory ICs include negative regulators present on T cells such as CTLA-4, PD-1, TIM-3, LAG-3 (CD233), TIGIT and CD96. These molecules control excessive immune activation and inflammation [24].

Table 2.

List of immune checkpoint receptors and ligands with their effect upon interaction

| Receptor | Ligands | Effect of receptor–ligand binding |

|---|---|---|

| CD28 | B7 | Stimulatory |

| CTLA-4 | B7-2 (CD86) | Inhibitory |

| PD-1 | PD-L1 | Inhibitory |

| PD-1 | PD-L2 | Inhibitory |

| TIM-3 | Galactin-9, High mobility group protein B1(HMB1), and Phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) | Inhibitory |

| TIGIT | CD155, CD112 and CD113 | Stimulatory |

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI)

Cancer cells utilise IC molecules (Table 2) to evade the attack by effector T cells. The development of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) is a remarkable milestone achieved in the field of immunology. ICI are therapeutic immunomodulatory antibodies that upregulate the host’s anti-tumour immunity by targeting the regulatory molecules on T cells and have demonstrated efficacy in multiple tumour types [25]. ICIs can reactivate anti-tumour immune responses by interrupting the signalling pathways, thus promoting the immune-mediated elimination of cancer cells.

To boost up the durability, safety and response rate of ICB therapy, it is crucial to understand the regulation of immune checkpoints both at its physiological as well as pathological conditions. These immune checkpoints engage in inter-cellular star war by modulating cell–cell interactions (Table 2). This feature differentiates them from housekeeping pathways participating in essential cellular activities. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint signalling has higher variability in immune cells, PD-1 activation can transduce an inhibitory signal and induce T cell exhaustion, but the stimulation of cancer-intrinsic PD-1 promotes cancer cell proliferation [26]. The regulation of immune checkpoint is much more complicated in cancer cells (conditions) mainly due to variations happening in cancer origins, mutational backgrounds, subtypes and stages and the way of treatment contexts. So, more attention has been given to generalise regulatory mechanism that is found in one cancer condition to another [27]. Based on various negative immune checkpoints, the following ICI blocker therapy for cancer has been developed.

ICI based on CTLA-4 blockade

Ipilimumab is the first CTLA-4 blockade therapy approved by FDA [28], it is a fully human monoclonal antibody against CTL antigen 4 (Table 3). After the demonstration of anti-tumour immunity by ipilimumab, studies were carried out in animal models and cancer patients. These studies clearly explained that antibody-based blockade of CTLA-4 can inhibit T reg-associated immune suppression and can promote both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell effector function. Ipilimumab is now used for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), non-small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), prostate cancer and many others [29].

Table 3.

Represents FDA-approved immune checkpoint blockers (antibody-based) with their targets and their action on biological functions

| Target | Biological function | Antibody or Ig fusion protein |

|---|---|---|

| CTLA-4 | Inhibitory receptor | Ipilimumab |

| CTLA-4 | Inhibitory receptor | Tremelimumab |

| PD1 | Inhibitory receptor | Nivolumab |

| PD1 | Inhibitory receptor | Pembrolizumab |

| TIM3 | Inhibitory receptor | Cobolimab |

| TIM3 | Inhibitory receptor | MBG453 |

| TIM3 | Inhibitory receptor | Sym023 |

| TIM3 | Inhibitory receptor | SHR1702 |

| TIGIT | Stimulatory receptor | Etigilimab |

| TIGIT | Stimulatory receptor | Tiragolumab |

ICI based on PD-1 blockade

Nivolumab is a human-IgG4K monoclonal antibody approved by the FDA that targets the PD-1 receptor. It was approved as a first-line therapy for untreated melanoma. Nivolumab exhibits more therapeutic benefits when compared to CTLA-4. Another anti-PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor is pembrolizumab which is used as an alternative to nivolumab as a second-line treatment for patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma [30].

ICI based on TIM3 blockade

TSR-022 (Cobolimab), MBG453 are novel anti-TIM3 monoclonal antibodies. Similarly, Sym023 is a human antibody developed by recombinant technology that can bind to TIM-3. Other TIM-3 inhibitors are INCAGN2390, LY3321367, BMS986258 and SHR1702 [31]. The efficacy of TIM3 blockers against cancer is under clinical trial.

ICI based on T cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) blockade

The inhibition of TIGIT was found to decrease tumour size, resistance to tumour re-challenge and has improved the survival rate. BMS-986207 (NCT 02913313) and MTIG7192A (NCT02794571) are two antibodies used for testing in combination with PD-1 inhibition. Etigilimab (OMP-313M32) is a humanized mAb used to block the binding of TIGIT on CD155. Tiragolumab is a fully humanized mAb used to hinder the activity of TIGIT on CD155 [32].

Although many ICI-based antibodies have been developed for cancer treatment, only two main types of ICIs are currently used; anti-CTLA-4 antibodies (e.g., Ipilimumab) and anti-PD-1 (e.g., Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab) antibodies. Anti-CTLA-4 antibody (Ipilimumab) has shown a reasonable survival rate in patients with melanoma. While compared to other immunotherapeutic methods such as interferon and cancer vaccines, ICI targeting mainly CTLA-4 and PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoints shows therapeutic effects with stronger and longer durability. Yet, ICI therapy has limitations, and one of the primary concerns is its low response rate. For example, humanized anti-PDL-1 inhibitors Tecentriq and Imvigor show a low response rate in carcinoma patients. Another critical challenge is the adverse effects caused due to these ICI, leading to compromised lifestyle and morbidity. To mitigate the above issues, researchers worldwide have used nano-based delivery systems. Nanomaterial-based targeted delivery of ICI will not only improve the response for ICIs and reduce adverse effects but will also aid in using low doses of ICI. In addition, if a nanomaterial with immuno-adjuvant properties is designed and utilised, it will amplify the anti-tumour response manifold. Amongst the various nanomaterial used for immunotherapeutics, mesoporous silica was reported to be the best and versatile nanomaterial for cancer immunotherapeutics [33].

Insight on Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSN)

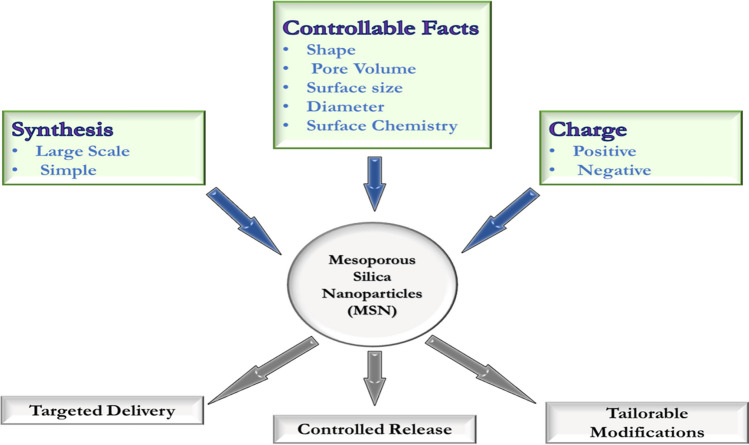

Mesoporous material emerged 25 years back when Kresge and co-workers [34] created a new class of ordered porous molecular sieves characterized by periodic arrangements of uniformly sized mesopores with ordered arrays of uniform nanochannels. MSNs have applications in various fields, such as molecular separation, catalysis, adsorption and biomedicine. Mesoporous material is a promising candidate for biomaterial-based immunotherapy (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Illustrates the novel features (that can be tuned) of the mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) for biomedical application

Mesoporous silica nanoparticle contains amorphous silicon dioxide with a wall surrounding well-defined mesopores that are formed using structure-directing agents (SDAs) co-assembled with silica precursors in the presence of catalysts (Fig. 5) [35]. MSN has empty pores arranged in a 2-D honeycomb-like structure with an exterior particle surface and interior pore surface. Different solvents, additives and SDA synthesize MSN with varied pore size, pore volume, structure and particle size. Excellent porosity and ideal surface chemistry make MSN a promising material platform for drug delivery. A well-studied inorganic material in scientific literature is silica due to its unique physio-chemical characteristics, ease of synthesis and low toxicity. In addition, MSNs have a high surface area, often exceeding 1000 m2/g, making it an ideal material for drug delivery as it can be loaded with hydrophobic or hydrophilic drugs. Ideally, the assembling of silica during MSN synthesis can be tuned to attain a desirable shape, size, and porosity. MSN can contribute diverse biosystem interactions based on physio-chemical properties such as pore size, particle shape, porosity and texture function [36]. These properties, in turn, help in cellular uptake, biodistribution, biodegradability, reduce toxicity and decide the mode of interaction with immune cells. MSN plays a crucial role as an immunopotentiator as it has innate immune adjuvanticity. It enables the design of an effective cancer vaccine carrying a high load of antigens and can also be combined with antigens. MSN helps to transport immunomodulating agents with antigenic payloads and immune stimulators for both peripheral dendritic cells (DC) at the injection site (e.g., Dermal DCs) and draining lymph nodes (dLN). MSNs loaded with immunomodulatory signals can drain into LNs by interstitial flow. Hence, MSNs are widely reported to be the best candidates for chemotherapeutic and immunotherapeutic drug delivery [37].

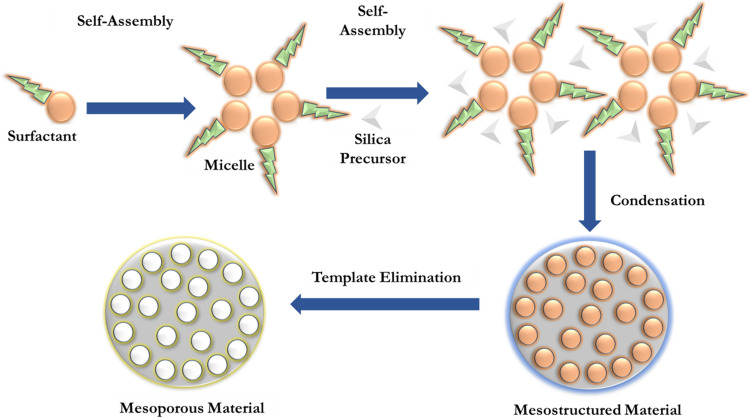

Fig. 5.

Represents a general synthesis strategy for the mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) using a surfactant-templated route

Types of MSNs

Based on the particle pore size, surface area and preparation method, MSNs are mainly grouped into (i) molecules 41 sieves (M41S), (ii) Santa Barbara amorphous (SBA), (iii) organically modified silica (ORMOSIL), (iv) hollow-type MSNs and (v) periodic mesoporous organosilica [38].

Synthesis of MSN

They are composed of silicon oxide (SiO2) and synthesized by surfactant template-based method (Fig. 5) [39]. Commonly, sol–gel, hydrothermal, microwave-assisted, precipitation, reverse micro-emulsion and flame synthesis methods are employed for the synthesis of MSN. Generally, three basic steps are involved in the synthesis of MSN;

-

i)

Generation of silica from precursor.

-

ii)

Self-assembly of template from surfactants (acts as structure directing agent) that aids in the formation of mesopores.

-

iii)

Template removal to produce porous silica nanoparticles.

Briefly, the synthesis process involves the following: surfactant is dissolved in water and alcohol under basic conditions and then tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) or another silicate is added. The surfactant molecules self-assemble into micelles, and the TEOS molecules condense on the surface of the micelles. A silica structure is formed around the micelles, and the surfactant is then removed. The resulting MSNs have a mesoporous structure with pores that are typically 2–5 nm in diameter [40].

Another method for synthesizing MSNs is to use triblock copolymers as templates. Triblock copolymers are molecules that consist of three blocks of different polymers. The blocks are arranged in such a way that they form micelles with a hexagonally ordered mesoporous structure. The MSNs are then formed by the condensation of TEOS or another silicate on the surface of the micelles. The pore size of MSNs can be controlled by several factors, including the concentration of surfactant or triblock copolymer, the type of surfactant or triblock copolymer and the pH of the solution [41]. Similarly, the particle size of MSNs can also be controlled by several factors, including concentration of TEOS or other silicate, stirring rate, and temperature. MSNs can be further modified by grafting or coating with other molecules. This can be done to improve the properties of MSNs for a particular application. For example, MSNs can be grafted with polymers that make them water-soluble or biocompatible. They can also be coated with polymers that make them more resistant to degradation [42].

MSN functionalisation

The surface functionalization of MSNs is achieved by establishing functional groups either on the external or internal surfaces of the MSNs or in some cases, on both surfaces. This can be carried out by one of the two synthetic strategies: stepwise synthesis (post-synthetic grafting) or one-pot synthesis (co-condensation method). By using either of the two methods, monofunctional or multifunctional MSNs are produced, depending on the types of functional groups (one or more than one type) introduced into the MSNs. Hence, the functional groups can be deliberately chosen in order to form functionalized MSNs with appropriate surface properties, morphology, pore size, and structures and thus suitable biocompatibility for medical applications. [43].

Surface modifications can have a major impact on nanoparticle tumour accumulation. PEGylation, which is used to minimise opsonisation and evade the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), can also reduce cellular nanoparticle uptake. However, Gu et al. [44] reported that PEGylated hollow MSNs were more effectively taken up by cancer cells and mouse embryonic fibroblasts than naked particles. Elevated interstitial fluid pressure in solid tumours can create pressure gradients and heterogeneous flow in the interstitium, which can influence the distribution of nanoparticles and lead to reduced particle concentrations in the tumour. Larger tumours and metastases often have necrotic tissue or highly hypovascular areas in the centre, which nanoparticles can barely reach by passive targeting. Active targeting is a more effective way to enhance drug delivery with nanocarriers and drug efficacy. In the case of leukemic diseases, nanoparticle targeting is inevitable because the EPR effect does not apply. Different targeting moieties can be added to the MSNs’ surface, such as small molecules, short peptides, aptamers, whole antibodies or antibody fragments.

Various strategies have been explored for MSN targeting in cancer therapy. One commonly targeted receptor is the folate receptor, which is overexpressed in tumors compared to healthy tissue. Researchers have successfully used folic acid–modified MSN to deliver chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA to laryngeal cancer cells [45]. Folate-targeted MSN has also been utilised to enhance the radioenhancer effect of valproic acid in glioblastoma cells [46]. Another targeting ligand, transferrin, has been employed in MSN to effectively deliver doxorubicin in hepatocellular carcinoma cells [47]. Short peptides such as Cyc6 and the RGD motif have shown promise in targeting bladder cancer and tumors overexpressing integrin αvβ3, respectively [48, 49]. Aptamers, including those targeting EpCAM and nucleolin, have demonstrated enhanced cellular viability reduction in hepatocellular carcinoma and tumor imaging capabilities [50]. Furthermore, whole antibodies or antibody fragments such as retuximab have been utilised for targeting leukemic cells, lymphoma, and tumor vasculature [51]. However, challenges remain in reducing nanoparticle accumulation in organs such as the liver, spleen, lungs and kidneys for an effective cancer therapy.

Biocompatibility, degradation, and pharmacokinetics of MSN

MSNs are biocompatible and get degraded to a non-toxic compound called silicic acid (Si (OH4)) [52]. However, the use of MSN as a nanocarrier has a limitation because of their fast clearance by the immune and excretory systems after injection [53]. This issue is addressed by coating the MSN with suitable polymer or liposomes. MSN can also be modified by coating with chitosan and other natural polymers; camouflaging of MSN with cell membrane has also been reported to improve the compatibility and increase the half-life of MSN in circulation [54].

The critical factors in determining the safety and degradation of the MSN drug delivery system are the rate and extent of adsorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination [55]. MSNs can be administered either by intravenous method or by oral route. Absorption and distribution of MSNs can vary based on the route of administration [56]. When orally administered, they are absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal tract [57]. It later accumulates in the liver, wherein the concentration of MSN increases initially and finally decreases after 7 days [58]. If intravenously administered with the same size, they accumulate in the liver and spleen [57]. These MSN were excreted through urine and faeces with a higher elimination rate after the oral route of administration. In addition to the above factors, the safety and toxicity of MSN also depend on the dosage. Hence, the toxicity of MSNs can be reduced by tuning the physiochemical properties and wisely choosing the route of administration in the host.

In studies conducted on mice, the long-term toxicity of fluorescent MSNs (FMSNs) was evaluated. Mice receiving intraperitoneal injection of FMSNs at a dose of 1 mg/mouse/d, twice per week for 2 months showed no histopathological abnormalities or lesions [59]. Similarly, female nude mice injected intravenously with 1 mg FMSNs/mouse/d, twice per week for 14 days exhibited no histological or gross abnormalities in various organs, including the liver, spleen, kidney, heart, intestine, stomach, muscle and lungs. Kidney tissues were also assessed and showed no signs of damage, inflammation or lesions, except for focal haemorrhage and atrophy of the renal glomerulus [60]. While the biocompatibility and toxicity of MSNs have been extensively studied, factors such as physicochemical parameters, particle characteristics and administration methods need further comprehensive investigation. New generations of MSNs are being developed to enhance biocompatibility and reduce toxicity while improving drug-loading capabilities.

Cellular and molecular interaction of MSN

The biological membrane is a prime barrier for the delivery of intercellular substances through both mechanisms of internalization and the translocations of MSNs when used as a carrier for therapeutics and diagnostics. There are many pathways reported for infiltrating MSN into cellular membranes. Usually, uptake mechanisms are classified into phagocytosis and pinocytosis (micropinocytosis and endocytosis). Small nanoparticles can be taken up by the cells by endocytic pathways such as clathrin-mediated or caveolae-mediated. Endocytic pathways are energy-dependent processes. Many energy-dependent routes might simultaneously be at play during the interaction between MSNs and cell membranes. However, each pathway of the endocytic function of MSNs may lead to a gain or loss of energy depending on many variables associated with cells; nevertheless, the physiochemical properties of MSNs (size of particle and pore, shape, surface charge and chemistry, etc.) in turn direct the outcome of the interaction between cells and particles [61].

After penetrating the cell membrane barrier, MSNs can reach the cytoplasm and release therapeutic drugs. BIO-TEM (Biological transmission electron microscopy) has been used to observe the uniform intracellular distribution of MSNs after endocytosis [62]. After internalization, MSNs are transported to large vesicular endosomes and finally infused with the lysosomes. Even if the endosomes/lysosomes were damaged, MSNs were found to escape from endosomes/lysosomes. Mostly, nanoparticles are spherical shapes found in cytoplasm while absent in the nucleus. MSN trafficking inside cells is studied by confocal microscopy using fluorescent staining of cells using dyes such as acridine orange (AO) that can specifically stain acidic organelles (both endosomes and lysosomes) as red. Still, other cellular regions are stained in green colour. When green fluorescence-labelled MSN overlaps the red fluorescence, that indicates MSNs are internalized into acidic organelles [63]. The following are the impact of various factors affecting cellular uptake:

Shape

The shape of the particle can determine MSN interaction with cells and the systematic distribution of MSNs. MSNs that have a high width-to-height ratio always have larger and faster cellular internalization and provide a significant effect in different aspects of cellular functions such as their proliferation, apoptosis, cytoskeleton formation, biocompatibility, biodegradation, biodistribution and many other crucial factors. MSNs with a high width-to-height ratio are less degradable when compared to MSNs with a lower width-to-height ratio. They also have less systematic absorption and excretion in vivo condition but exhibits better biocompatibility [64].

-

2.

Pore and particle size

The pore diameter is a crucial factor for drug delivery; it should be higher than the size of the drug molecule to accommodate more drug molecules. However, for cellular uptake, MSN particle size plays a key role, resulting in bioactivity. MSN particles of small size can be effectively internalized into cells compared to large-sized particles. Thus, pore size and particle size are important factors to be considered in drug delivery [65].

-

3.

Pore volume

Larger pore volume and surface area can make MSNs more potent to embed more drug molecules into it. The pore volume of MSNs can determine the drug-loading capacity. Pore volume is directly proportional to the drug-loading capacity; as the pore volume increases, in turn, the drug-loading capacity increases. Pore volume is not reported to influence cellular or molecular interaction [66].

-

4.

Surface functionalization

The high versatility of MSNs in biomedical applications is due to their large surface area. Covalent attachment of different functional groups such as hydroxyl-, amino-, thiol- and carboxyl- groups can be carried out during or after the synthesis of MSNs [67]. Physio-chemical properties of MSN can be improved by modifying the surface to achieve better biocompatibility, biodegradability and high drug-loading capacity, cell targeting capacity and targeted drug release. Tuning the MSN as innovative material to respond to external stimuli, which include pH, light, temperature, enzymes, glucose, magnetic and electrical fields, and oxidising or reducing agents, can be accomplished by surface functionalisation. [68].

MSN for anticancer drug delivery system

Due to its characteristic features such as high surface area, pore structure and volume, MSN is a multi-functional platform for cancer therapeutics. MSN has an ideal drug-loading capacity and also allows a sustained drug-release profile (Fig. 6) [69]. Three key factors that enable high drug loading in MSN are (a) electrostatic adsorption or hydrophobic interactions: drugs can be incorporated into pores and onto MSN surfaces. (b) Chemical bonding: mediated by covalent grafting of drugs on the surface of porous channels in MSNs. (c) in situ loading: doping drugs can be done during the synthesis and growth of MSN [69].

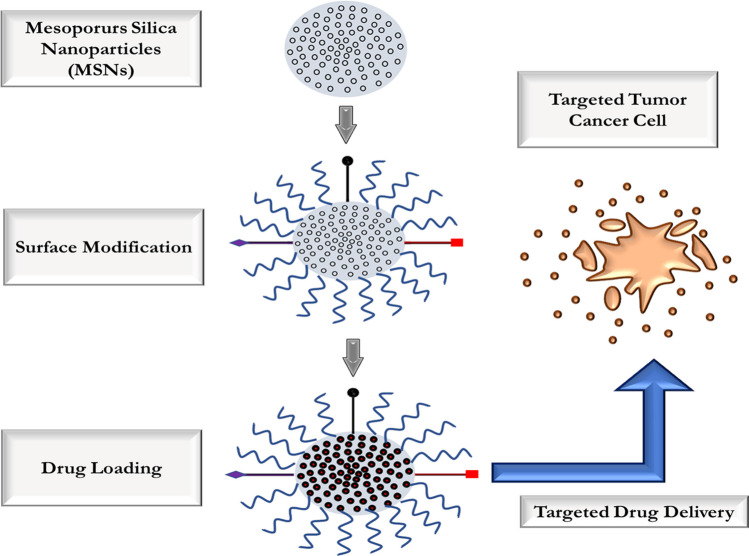

Fig. 6.

Illustrates the mode of drug loading and the delivery of a drug by MSN in targeted tumour cancer cell

The most popular method for drug loading into MSNs is through adsorption by mixing MSNs with drug solution [70]. The silica surface is negatively charged on which water-soluble positively charged drug molecules can get absorbed and thus form a stable MSN-drug complex. Anti-cancer drugs with different charges are electrostatically absorbed through linker molecules such as silane covalently bound to MSN. Hydrophobic interactions load water-immiscible drugs into the pores and surfaces of MSNs. Also, various functional molecules in the form of gatekeepers are conjugated on the surface of MSNs to avoid the premature release of drugs [71].

MSNs as immunomodulators

MSN alone can act as an immune adjuvant and is shown to induce effective anticancer immunity response in vivo studies [56]. A study in mice model shows that MSN can enhance the effector T cells population, namely CD4 + and CD8 + T cells, in the 3 most important organs, i.e., bone marrow, spleen and lymph node. Plain MSN is an ideal and efficient adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy and can co-load antigen and adjuvant together in a single platform. MSN with a nanostructure similar to bacteria was shown to mimic pathogen-like activity and induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and APCs stimulation in tumours [72].

MSN used in immunotherapy can be classified into two types based on particle size and based on their interaction mode with immune cells. MSNs that are nanometre in size and mesoporous silica micro rods (MSRs) of several tens of micrometres in length. Both MSNs and MSRs are ideal cancer vaccine platforms as they have a self-immunoadjuvant property and can carry immune modulatory agents, tumour-associated antigens (TAAs) and chemo-attractants in mesopores [73]. MSN vaccine uptake by APCs, such as immature dendritic cells (iDCs) and macrophages, is a requisite for delivering antigenic information. 3D interparticle macropores of MSD scaffold generated by rod-shaped particles were shown to recruit APC [74]. Immune cells which are recruited get activated and programmed by immunomodulators. Thus, the co-release of antigen and adjuvant can help overlap therapeutic windows. Particle size, shape, pore structure and pore size of MSN can influence the immune response type [75].

MSN-based ICI immunotherapy

MSN has been proven to be a preferred biomaterial for the delivery of ICI by many researchers around the world for various types of cancer, including melanoma [76], hepatic cancer [77], pancreatic cancer [78], colonic cancer [79], breast cancer [80], etc. Most studies have combined them with other therapeutic modalities such as chemotherapy [81], phototherapy and other biomolecular therapies [82]. A list of studies demonstrating the use of MSN in cancer immunotherapy is mentioned in (Table 4). Amongst the different types of ICI, PD-1 or PD-L1 inhibitors have been widely demonstrated in MSN-based cancer therapeutics [88]. Though different studies are carried out with MSN and ICI, PD 1/PDL1 blocking antibodies are the standard modality used in most research studies.

Table 4.

Lists of studies employing mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN) for cancer immunotherapy with the details of the immune checkpoint (ICB) used and the experimental model (in vivo/in vitro) used in the study

| Type of MSN used | Type of cancer | ICB | Modalities used | Model used (in vitro/in vivo) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hollow mesoporous silica-coated MnO nanoparticles (NPs) | Melanoma | α-PD-1 | Chemodynamic combination therapy | Mice | Zhaoli Sun et al. [83] |

| Infrared dye 700 DX silica-phthalocyanine dye | Squamous cell carcinoma | CTLA4 | Near-infrared (NIR-PIT) photoimmunotherapy | Mice | Fukushima H et al. [76] |

| Glutathione-responsive degradable mesoporous silica nanoparticles loaded with SB525334 | Pancreatic cancer | αPD1 therapy | Combined irreversible electroporation (IRE) | Hs766T human pancreatic cancer cells and 4T1 murine breast cancer cells, mice | Peng H et al. [84] |

| Hybrid membrane nanovaccine-mesoporous silica nanoparticle (HM-NPs) | Model in breast cancer cell | Anti-programmed cell death-1 (αPD-1) and anti-programmed cell death ligand-1 (αPD-L1) | Hybrid membrane derived nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy | 4T1 (triple negative breast cancer cell line), HBL-100 (human mammary epithelial cell line) and B16F10 (murine melanoma cell line) cells | Zhao P et al. [85] |

| Conjugated TLR7 agonists onto silica nanoparticles | CT26 colon cancer | PD-1, CTLA-4 | siRNA targeting PD-L1 | Mouse colon cancer cell line CT26, mice | Huang C et al. [86] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles coated with a lipid bilayer (a.k.a. silicasomes) | Colon cancer model | PD-1/PD-L1 | monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy or other immunomodulatory agents | MC38, CT26, LLC, and KPC cell lines, mice | Allen SD et al. [79] |

| Ferumoxytol (Fer) capped PD-L1 antibodies (aPD-L1) loaded ultra large pore mesoporous silica nanoparticles (Fer-ICB UP MSNPs) | Prostate cancer | PD-L1 and aPD-L1 | Sequential magnetic resonance (MR) image-guided local immunotherapy | In vitro and in vivo TRAMP C1 PC mice model | Choi B et al. [87] |

| Crystalline silica | Silicosis | B cell and T cell proliferation | B cell antigen receptor, T cell antigen receptor | CD4( +) T cells and B cells | Eleftheriadis T et al. [82] |

| Fluorescently labelled anionic silica nanoparticle | Metastatic ovarian cancer | PD1 and PD-L1 | Intraperitoneal therapy | OVCAR8-GFP cells, SKOV-3 cell, mice | Haber T et al. [88] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) modified with c(RGDfK)-PLGA-PEG [c(RGDfK)-MSN NPs] | Bladder cancer | PD-L1 | siRNA and miRNA 34a | T24 cells and T24 mice | Shahidi M et al. [89] |

| Biodegradable mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles | 4T1 breast cancer cell membranes | PD-L1 | X-ray radiation responsivity and chemo-immunotherapy | 4T1 breast cells, mice | Shao D et al. [81] |

| Cu-containing mesoporous silica nanosphere-modified β-tricalcium phosphate (Cu-MSN-TCP) scaffolds | Bone tumour cells | May be used in the future for ICI | Photothermal tumour therapy | MG-63 cells, rabbit bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Ma H et al. [90] |

| Mesoporous nanocarrier composed of an upconverting nanoparticle core and a large-pore mesoporous silica shell (UCMS) | General cancer | PD-L1 | Near-infrared (NIR) activated photodynamic therapy (PDT) | Mice | Wang Z et al. [91] |

| Highly biocompatible mesoporous silica (MSNP) surface-coated with platelet membrane (PM) | Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) | Anti-PD-L1 | Combination therapy | Mice | Li B et al. [77] |

| Mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) | General cancer | Anti-PD-1 | Combined modality therapy; immunotherapy | B16F10 tumour cell line, mice | Sun M et al. [92] |

Various strategies to tune MSN for efficient cancer immunotherapy have been attempted. A biodegradable manganese oxide (MnO)–doped MSN with an engineered surface improved drug delivery and immune activation against cancer [83]. Manganese-doped MSN has also been utilised to deliver CTLA Blockers to inhibit primary and metastatic tumours [93].

Interestingly, a study has demonstrated the potency of hollow MSN to act as an immune adjuvant for therapeutic cancer vaccines, which also included ICI blockers [94]. A similar strategy was used to develop a hybrid membrane nano vaccine combined with ICB to enhance cancer immunotherapy [85]. Peptide vaccine conjugated to MSN was found to show cancer cell death induced by immune cells and amplified immunotherapy with PD L1 blocker in metastatic spinal cancer [91].

An exciting and novel study demonstrated that using MSN as a pre-dose before immunotherapy stimulated the cold tumours to respond to therapy. Both granular and rod-shaped MSNs, even once injected, were able to turn cold tumours into hot tumours and served to overcome resistance to anti-PD-1 treatment [92]. An efficient checkpoint blockade therapy with a metal–organic framework (MOF) gated MSN was developed and used as a cancer vaccine, wherein the core MSN was found to act as an intrinsic immunopotentiator [95]. A cancer vaccine for melanoma was designed using MSN to attract high dendritic cells. These MSNs were shown to be internalised by DC and consequently induced antigen-specific CD8 + T cells and IFN-γ secretion. This MSN-based vaccine used CPG-ODN as a TLR agonist and CTLA blocker to inhibit immune checkpoint [96].

An optimal treatment outcome was found when a PD L1 blocker with MSN and siRNA as a targeting agent was explicitly employed for solid tumours [97]. Combining small molecule immunostimulatory molecules such as TLR-7 agonists will improve treatment efficacy. However, they are restricted due to poor pharmacokinetics. Yet, the conjugation of TLR agonist along with PD L1 blocker onto MSN showed extended drug localisation after intra-tumoral injection in mice model [86].

Combination of photodynamic and immunotherapy based on MSN

Photodynamic Immunotherapy (PDT) is a promising anticancer treatment that utilises photosensitizers (PS) activated by specific light wavelengths to induce tumour cell death and stimulate immune responses. Nanotechnology has been integrated into PDT to enhance its efficacy and reduce toxicity to normal tissues. Im et al. developed a hypoxia-responsive nanodevice using mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) loaded with chlorin e6 (Ce6) and CpG oligonucleotide as a vaccine adjuvant. When combined with laser irradiation, this nanodevice showed significant tumour growth inhibition and improved survival rates in mice [98]. Similarly, Ding et al. designed a nano-vaccine using upconverting nanoparticles loaded with merocyanine 540 (MC540) and a tumour antigen. The nano-vaccine demonstrated tumour clearance and prolonged survival in mice when combined with near-infrared laser irradiation [99]. Xu et al. developed a nano vaccine for PDT-immunotherapy combined with image-guided therapy, utilising biodegradable MSNs loaded with CpG, Ce6 and a tumour-specific peptide. This nano-vaccine exhibited effective tumour reduction and improved survival in a mouse model [100]. These studies highlight the potential of MSN-based nanovaccines in achieving synergistic PDT and immunotherapy effects, leading to enhanced therapeutic outcomes in cancer treatment. A promising strategy for cancer treatment involves combining photosensitizers (PS) with checkpoint blockade immunotherapy using MSN. Yang et al. developed a smart nanoreactor system that integrated photodynamic therapy (PDT) and anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy. The system utilised hollow silica nanoparticles loaded with catalase (CAT) and Ce6, along with a mitochondrial targeting molecule, CTPP. This nanoreactor system effectively overcame hypoxia and improved the efficacy of PDT. When combined with PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy, the nanoreactor system demonstrated a significant generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and suppression of tumour growth, both in the irradiated primary tumour and non-irradiated distant tumour. This combination therapy holds promise for inhibiting metastasis [101].

Stimuli-responsive ICI immunotherapy with MSN

Stimuli-responsive immunotherapy with ICI blockers in MSN has been attempted. A study by M Terracciano et al. [102] has fabricated light-triggered multifunctional nanoplatforms for inhibiting tumour growth and metastasis and tuning anticancer immune response with anti-PD L1 antibody [103]. A glutathione-responsive MSN loaded with an inhibitor of TGF β 1 receptor along with a PD1/PD L1 blocker and neutrophil modulator was shown to enhance treatment outcomes for pancreatic cancer [84]. Similarly, a diselenide-bridged MSN-carrying PD1 blocker has been shown to self-destruct upon red light stimulation [81]. An intelligent multifunctional imaging-guided therapeutic platform was designed based on an MSN system that sequentially released short D peptide antagonists of PD L1 stimulated by high matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) and glutathione (GSH) in the tumour. It was incorporated with photosensitiser methylene blue, which enabled MRI imaging and micro-CT for non-invasive diagnosis and monitoring of drug delivery. Thus, MMP-2, a GSH-sensitive delivery system based on MSN, was successfully achieved [81]. A similar strategy was proved by Ye Chen et al. [104]. Another study showed a proof of concept for MR image-guided local ICB immunotherapy using ferumoxytol-capped PD L1 antibody loaded onto an ultra-large pore MSN [105]. A combination of starvation as stimuli and immunotherapy was prepared by encapsulating MSN with a cancer cell membrane. The encapsulated MSN was loaded with glucose oxidase. This type of immunotherapy platform worked on starvation as a stimulus and was found to deliver ICI blockers directly to dendritic cells (APC) [82]. A combination of PD L1 blocker and doxorubicin loaded onto a low-dose x-ray-responsive MSN was carried out. They were coated with cancer cell membranes to effectively target these nanosystems at the cancer site. In addition, these MSN systems were also responsive to reactive oxygen species (ROS). Hence, it is well evident from the literature that MSN is an ideal material for cancer immunotherapy and can be tuned in novel ways to deliver multiple therapeutic agents and can be successful for the theragnostic of cancer too.

Conclusion

The significance of MSNs as delivery vehicles with particular emphasis on cancer therapy, including novel opportunities for biomimetic therapeutics and immunotherapy delivery has been well-demonstrated and proven to be successful as evidenced by research studies around the globe. In most of the studies, MSNs are directed towards PD1/PDL1 inhibitors-based immunotherapy, aided by the targeting ability and controlled release of a drug. It can also be observed that MSN enables the development of combination therapy such as the inclusion of chemotherapy drug, an imaging molecule and immunotherapeutic in a single cargo; in addition, they can be tuned in such a way that the drug will be released to a response to stimuli. So, there are still studies to be done with other ICI blockers and check their potency in MSN-based delivery systems. Extensive in vitro functional characterisation and successful outcomes observed in the in vivo experiments using animal models prove the high translational capacity of novel MSNs. Moreover, the current phase I and II clinical trials on MSN-based cancer therapeutics have shown promising outcomes. This encourages to focus more on MSN-based biomedical research as there are still some challenges and hurdles in the synthesis and tuning of MSN that will open up new avenues and opportunities in cancer treatment and immunotherapeutics for other diseases too.

References

- 1.Chaplin DD. Overview of the immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S3-23. 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.12.980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, et al. Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20(1):621–67. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burger D, Dayer JM. Cytokines, acute‐phase proteins, and hormones: IL‐1 and TNF‐α production in contact‐mediated activation of monocytes by T lymphocytes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;966(1):464–73. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04248.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Tian T, Olson S, Whitacre JM, et al. The origins of cancer robustness and evolvability. Integr Biol (Camb). 2011;3(1):17–30. 10.1039/c0ib00046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boon T, Cerottini JC, Van den Eynde B, et al. Tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:337–65. 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn GP, Bruce AT, Ikeda H, et al. Cancer immunoediting: from immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(11):991–8. 10.1038/ni1102-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen DS, Irving BA, Hodi FS. Molecular pathways: next-generation immunotherapy–inhibiting programmed death-ligand 1 and programmed death-1. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(24):6580–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39(1):1. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu Z, Zhen B, Park Y, et al. Designing therapeutic cancer vaccine trials with delayed treatment effect. Stat Med. 2017;36(4):592–605. 10.1002/sim.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varadé J, Magadán S, González-Fernández Á. Human immunology and immunotherapy: main achievements and challenges. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(4):805–28. 10.1038/s41423-020-00530-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabalgoity JA, Dougan G, Mastroeni P, et al. Live bacteria as the basis for immunotherapies against cancer. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2002;1(4):495–505. 10.1586/14760584.1.4.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davola ME, Mossman KL. Oncolytic viruses: how “lytic” must they be for therapeutic efficacy? Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(6):e1581528. 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1596006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fu C, Ma T, Zhou L, et al. Dendritic cell-based vaccines against cancer: challenges, advances and future opportunities. Immunol Invest. 2022;51(8):2133–58. 10.1080/08820139.2022.2109486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner LM, Dhodapkar MV, Ferrone S. Monoclonal antibodies for cancer immunotherapy. The Lancet. 2009;373(9668):1033–40. 10.1007/s11033-018-4427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang WG, Liu SH, Cao XM, et al. A phase-I clinical trial of active immunotherapy for acute leukemia using inactivated autologous leukemia cells mixed with IL-2, GM-CSF, and IL-6. Leuk Res. 2005;29(1):3–9. 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tanaka F, Hashimoto W, Okamura H, et al. Rapid generation of potent and tumor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by interleukin 18 using dendritic cells and natural killer cells. Can Res. 2000;60(17):4838–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosseinkhani N, Derakhshani A, Kooshkaki O, et al. Immune checkpoints and CAR-T cells: the pioneers in future cancer therapies? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8305. 10.3390/ijms21218305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster RM. The immune checkpoint inhibitors: where are we now? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2014;13(12):883–4. 10.1038/nrd4476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):252–64. 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harding FA, McArthur JG, Gross JA, et al. CD28-mediated signalling co-stimulates murine T cells and prevents induction of anergy in T-cell clones. Nature. 1992;356(6370):607–9. 10.1038/356607a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong C, Juedes AE, Temann UA, et al. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature. 2001;409(6816):97–101. 10.1038/35051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaleeba JA, Offner H, Vandenbark AA, et al. The OX-40 receptor provides a potent co-stimulatory signal capable of inducing encephalitogenicity in myelin-specific CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 1998;10(4):453–61. 10.1093/intimm/10.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bertram EM, Dawicki W, Watts TH. Role of T cell costimulation in anti-viral immunity. Semin Immunol. 2004;16(3):185–96. 10.1016/j.smim.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Villanueva MT. Cancer immunotherapy: searching in the immune checkpoint black box. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(9):599. 10.1038/nrd.2017.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbee MS, Ogunniyi A, Horvat TZ, et al. Current status and future directions of the immune checkpoint inhibitors ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, and nivolumab in oncology. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(8):907–37. 10.1177/1060028015586218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muenst S, Soysal SD, Gao F, et al. The presence of programmed death 1 (PD-1)-positive tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes is associated with poor prognosis in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:667–76. 10.1007/s10549-013-2581-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassounah NB, Malladi VS, Huang Y, et al. Identification and characterization of an alternative cancer-derived PD-L1 splice variant. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2019;68(3):407–20. 10.1007/s00262-018-2284-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thumar JR, Kluger HM. Ipilimumab: a promising immunotherapy for melanoma. Oncology. 2010;24(14):1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helmy KY, Patel SA, Nahas GR, et al. Cancer immunotherapy: accomplishments to date and future promise. Ther Deliv. 2013;4(10):1307–20. 10.4155/tde.13.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):320–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson AC. Tim-3, a negative regulator of anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(2):213–6. 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dougall WC, Kurtulus S, Smyth MJ, et al. TIGIT and CD96: new checkpoint receptor targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2017;276(1):112–20. 10.1111/imr.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenholm JM, Mamaeva V, Sahlgren C, et al. Nanoparticles in targeted cancer therapy: mesoporous silica nanoparticles entering preclinical development stage. Nanomedicine. 2012;7(1):111–20. 10.2217/nnm.11.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature. 2002;417(6891):813–21. 10.1038/nature00785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan Y, Zhang D, Hao N, et al. Organic groups functionalised mesoporous silicates. Int J Nanotechnol. 2007;4(1–2):66–99. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuthati Y, Sung PJ, Weng CF, et al. Functionalization of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeting, biocompatibility, combined cancer therapies and theragnosis. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2013;13(4):2399–430. 10.1166/jnn.2013.7363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An M, Li M, Xi J, et al. Silica nanoparticle as a lymph node targeting platform for vaccine delivery. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9(28):23466–75. 10.1021/acsami.7b06024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Zhao Q, Han N, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in drug delivery and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2015;11(2):313–27. 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh LP, Bhattacharyya SK, Kumar R, et al. Sol-Gel processing of silica nanoparticles and their applications. Adv Coll Interface Sci. 2014;214:17–37. 10.1016/j.cis.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolla PA, Huggias S, Serradell MA, et al. Synthesis and catalytic application of silver nanoparticles supported on Lactobacillus kefiri S-layer proteins. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(11):2322. 10.3390/nano10112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deodhar GV, Adams ML, Trewyn BG. Controlled release and intracellular protein delivery from mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biotechnol J. 2017;12(1):1600408. 10.1002/biot.201600408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang YW. Towards biocompatible nanovalves based on mesoporous silica nanoparticles. MedChemComm. 2011;2(11):1033–49. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Giri S, et al. Synthesis and functionalization of a mesoporous silica nanoparticle based on the sol–gel process and applications in controlled release. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40(9):846–53. 10.1021/ar600032u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gu J, Su S, Zhu M, et al. Targeted doxorubicin delivery to liver cancer cells by PEGylated mesoporous silica nanoparticles with a pH-dependent release profile. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012;161:160–7. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.05.035. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qi X, Yu D, Jia B, et al. Targeting CD133+ laryngeal carcinoma cells with chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA against ABCG2 mediated by thermo/pH-sensitive mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Tumor biology. 2016;37:2209–17. 10.1007/s13277-015-4007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Zhang W, Zhou Y, et al. Dual functional mesoporous silicon nanoparticles enhance the radiosensitivity of VPA in glioblastoma. Transl Oncol. 2017;10(2):229–40. 10.1016/j.tranon.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen X, Sun H, Hu J, et al. Transferrin gated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for redox-responsive and targeted drug delivery. Colloids Surf, B. 2017;152:77–84. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sweeney SK, Luo Y, O’Donnell MA, et al. Peptide-mediated targeting mesoporous silica nanoparticles: a novel tool for fighting bladder cancer. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2017;13(2):232–42. 10.1166/jbn.2017.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hirano Y, Kando Y, Hayashi T, et al. Synthesis and cell attachment activity of bioactive oligopeptides: RGD, RGDS, RGDV, and RGDT. J Biomed Mater Res. 1991;25(12):1523–34. 10.1002/jbm.820251209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babaei M, Abnous K, Taghdisi SM, et al. Synthesis of theranostic epithelial cell adhesion molecule targeted mesoporous silica nanoparticle with gold gatekeeper for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nanomedicine. 2017;12(11):1261–79. 10.1002/jbm.820251209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou S, Wu D, Yin X, et al. Intracellular pH-responsive and rituximab-conjugated mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery to lymphoma B cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:1–4. 10.1186/s13046-017-0492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heinemann S, Coradin T, Desimone MF. Bio-inspired silica–collagen materials: applications and perspectives in the medical field. Biomater Sci. 2013;1(7):688–702. 10.1039/c3bm00014a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.He Q, Zhang Z, Gao F, et al. In vivo biodistribution and urinary excretion of mesoporous silica nanoparticles: effects of particle size and PEGylation. Small. 2011;7(2):271–80. 10.1002/smll.201001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kuang Y, Zhai J, Xiao Q, et al. Polysaccharide/mesoporous silica nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;193:457–73. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.10.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mamaeva V, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in medicine—recent advances. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2013;65(5):689–702. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Li Z, Zhang Y, Feng N. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, classification, drug loading, pharmacokinetics, biocompatibility, and application in drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(3):219–37. 10.1080/17425247.2019.1575806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fu C, Liu T, Li L, et al. The absorption, distribution, excretion and toxicity of mesoporous silica nanoparticles in mice following different exposure routes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(10):2565–75. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.He Q, Zhang Z, Gao F, et al. In vivo biodistribution and urinary excretion of mesoporous silica nanoparticles: effects of particle size and PEGylation. Small. 2011;7(2):271–80. 10.1002/smll.201001459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lu J, Liong M, Li Z, et al. Biocompatibility, biodistribution, and drug-delivery efficiency of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy in animals. Small. 2010;6(16):1794–805. 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yu T, Greish K, McGill LD, et al. Influence of geometry, porosity, and surface characteristics of silica nanoparticles on acute toxicity: their vasculature effect and tolerance threshold. ACS Nano. 2012;6(3):2289–301. 10.1021/nn2043803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nguyen TL, Choi Y, Kim J. Mesoporous silica as a versatile platform for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31(34):1803953. 10.1002/adma.201803953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y, Chen H, Zeng D, et al. Core/shell structured hollow mesoporous nanocapsules: a potential platform for simultaneous cell imaging and anticancer drug delivery. ACS Nano. 2010;4(10):6001–13. 10.1021/nn1015117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu Q, Zhang J, Xia W, et al. Magnetic field enhanced cell uptake efficiency of magnetic silica mesoporous nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2012;4(11):3415–21. 10.1039/c2nr30352c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hao N, Li L, Tang F. Shape matters when engineering mesoporous silica-based nanomedicines. Biomater Sci. 2016;4(4):575–91. 10.1039/c5bm00589b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang W, Kim BY, Rutka JT, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3(3):145–50. 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vivero-Escoto JL, Slowing II, Trewyn BG, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intracellular controlled drug delivery. Small. 2010;6(18):1952–67. 10.1002/smll.200901789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Douroumis D, Onyesom I, Maniruzzaman M, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in nanotechnology. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2013;33(3):229–45. 10.3109/07388551.2012.685860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Song Y, Li Y, Xu Q, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for stimuli-responsive controlled drug delivery: advances, challenges, and outlook. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:87. 10.2147/IJN.S117495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mamaeva V, Sahlgren C, Lindén M. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in medicine-recent advances. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(5):689–702. 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He Q, Shi J. MSN anti-cancer nanomedicines: chemotherapy enhancement, overcoming of drug resistance, and metastasis inhibition. Adv Mater. 2014;26(3):391–411. 10.1002/adma.201303123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wen J, Yang K, Liu F, et al. Diverse gatekeepers for mesoporous silica nanoparticle based drug delivery systems. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(19):6024–45. 10.1039/c7cs00219j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zheng DW, Chen JL, Zhu JY, et al. Highly integrated nano-platform for breaking the barrier between chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2016;16(7):4341–7. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X, Li X, Yoshiyuki K, et al. Erratum to supporting information of comprehensive mechanism analysis of mesoporous-silica-nanoparticle-induced cancer immunotherapy. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8(23): e1901432. 10.1002/adhm.201901432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Heidegger S, Gößl D, Schmidt A, et al. Immune response to functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery. Nanoscale. 2016;8(2):938–48. 10.1039/c5nr06122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hao N, Liu H, Li L, Chen D, Li L, Tang F. In vitro degradation behavior of silica nanoparticles under physiological conditions. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2012;12(8):6346–54. 10.1166/jnn.2012.6199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fukushima H, Turkbey B, Pinto PA, et al. Near-infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT) in urologic cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(12):2996. 10.3390/cancers14122996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li B, Zhang X, Wu Z, et al. Reducing postoperative recurrence of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma by a wound-targeted nanodrug. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(20):e2200477. 10.1002/advs.202200477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Peng H, Shen J, Long X, et al. Local Release of TGF-β Inhibitor modulates tumor-associated neutrophils and enhances pancreatic cancer response to combined irreversible electroporation and immunotherapy. Adv Sci. 2022;9(10):2105240. 10.1002/advs.202105240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Allen SD, Liu X, Jiang J, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibition in syngeneic mouse cancer models by a silicasome nanocarrier delivering a GSK3 inhibitor. Biomaterials. 2021;269:120635. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.He Z, Zhang H, Li H, et al. Preparation, biosafety, and cytotoxicity studies of a newly tumor-microenvironment-responsive biodegradable mesoporous silica nanosystem based on multimodal and synergistic treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020. 10.1155/2020/7152173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Shao D, Zhang F, Chen F, et al. Biomimetic diselenide-bridged mesoporous organosilica nanoparticles as an x-ray-responsive biodegradable carrier for chemo-immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2020;32(50). 10.1002/adma.202004385 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Eleftheriadis T, Pissas G, Zarogiannis S, et al. Crystalline silica activates the T-cell and the B-cell antigen receptor complexes and induces T-cell and B-cell proliferation. Autoimmunity. 2019;52(3):136–43. 10.1080/08916934.2019.1614171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sun Z, Wang Z, Wang T, et al. Biodegradable MnO-based nanoparticles with engineering surface for tumor therapy: simultaneous fenton-like ion delivery and immune activation. ACS Nano. 2022. 10.1021/acsnano.2c00969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Peng H, Shen J, Long X, et al. Local release of TGF-β inhibitor modulates tumor-associated neutrophils and enhances pancreatic cancer response to combined irreversible electroporation and immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2022;9(10):e2105240. 10.1002/advs.202105240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhao P, Xu Y, Ji W, et al. Hybrid membrane nanovaccines combined with immune checkpoint blockade to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Int J Nanomedicine [Internet]. 2022;17:73–89. 10.2147/IJN.S346044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang C, Mendez N, Echeagaray OH, et al. Immunostimulatory TLR7 agonist-nanoparticles together with checkpoint blockade for effective cancer immunotherapy. Adv Ther (Weinh). 2020;3(6):1900200. 10.1002/adtp.201900200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Choi B, Jung H, Yu B, et al. Sequential MR image-guided local immune checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy using ferumoxytol capped ultralarge pore mesoporous silica carriers after standard chemotherapy. Small. 2019;15(52). 10.1002/smll.201904378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Haber T, Cornejo YR, Aramburo S, et al. Specific targeting of ovarian tumor-associated macrophages by large, anionic nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(33):19737–45. 10.1073/pnas.1917424117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shahidi M, Abazari O, Dayati P, et al. Multicomponent siRNA/miRNA-loaded modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles targeted bladder cancer for a highly effective combination therapy. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology. 2022;10. 10.3389/fbioe.2022.949704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 90.Ma H, Ma Z, Chen Q, et al. Bifunctional, copper-doped, mesoporous silica nanosphere-modified, bioceramic scaffolds for bone tumor therapy. Front Chem. 2020;8:610232. 10.3389/fchem.2020.610232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang Z, Chen L, Ma Y, et al. Peptide vaccine-conjugated mesoporous carriers synergize with immunogenic cell death and PD-L1 blockade for amplified immunotherapy of metastatic spinal. J Nanobiotechnol. 2021;19(1). 10.1186/s12951-021-00975-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Sun M, Gu P, Yang Y, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles inflame tumors to overcome anti-PD-1 resistance through TLR4-NFκB axis. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(6). 10.1136/jitc-2021-002508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Yu X, Wang X, Yamazaki A, et al. Tumor microenvironment-regulated nanoplatforms for the inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis in chemo-immunotherapy. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10(19). 10.1039/d2tb00337f. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Wang X, Li X, Ito A, et al. Synergistic anti-tumor efficacy of a hollow mesoporous silica-based cancer vaccine and an immune checkpoint inhibitor at the local site. Acta Biomater. 2022;145:235–45. 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li X, Wang X, Ito A, et al. A nanoscale metal organic frameworks-based vaccine synergises with PD-1 blockade to potentiate anti-tumour immunity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1). 10.1038/s41467-020-17637-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Nguyen TL, Cha BG, Choi Y, et al. Injectable dual-scale mesoporous silica cancer vaccine enabling efficient delivery of antigen/adjuvant-loaded nanoparticles to dendritic cells recruited in local macroporous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2020;239. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119859. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Kim H, Yuk SA, Dieterly AM, et al. Nanosac, a noncationic and soft polyphenol nanocapsule, enables systemic delivery of siRNA to solid tumors. ACS Nano. 2021;15(3):4576–93. 10.1021/acsnano.0c08694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Im S, Lee J, Park D, et al. Hypoxia-triggered transforming immunomodulator for cancer immunotherapy via photodynamically enhanced antigen presentation of dendritic cell. ACS Nano. 2018;13(1):476–88. 10.1021/acsnano.8b07045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ding B, Shao S, Yu C, et al. Large-pore mesoporous-silica-coated upconversion nanoparticles as multifunctional immunoadjuvants with ultrahigh photosensitizer and antigen loading efficiency for improved cancer photodynamic immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2018;30(52):1802479. 10.1002/adma.201802479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Xu C, Nam J, Hong H, et al. Positron emission tomography-guided photodynamic therapy with biodegradable mesoporous silica nanoparticles for personalized cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2019;13(10):12148–61. 10.1021/acsnano.9b06691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang G, Xu L, Xu J, et al. Smart nanoreactors for pH-responsive tumor homing, mitochondria-targeting, and enhanced photodynamic-immunotherapy of cancer. Nano Lett. 2018;18(4):2475–84. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Terracciano M, Fontana F, Falanga AP, et al. Development of surface chemical strategies for synthesizing redox-responsive diatomite nanoparticles as a green platform for on-demand intracellular release of an antisense peptide nucleic acid anticancer agent. Small. 2022;18(41):e2204732. 10.1002/smll.202204732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yang Y, Chen F, Xu N, et al. Red-light-triggered self-destructive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cascade-amplifying chemo-photodynamic therapy favoring antitumor immune responses. Biomaterials. 2022;281. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121368. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Feng Y, Xie X, Zhang H, et al. Multistage-responsive nanovehicle to improve tumor penetration for dual-modality imaging-guided photodynamic-immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2021;275:120990. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen Y, Ma H, Wang W, et al. A size-tunable nanoplatform: enhanced MMP2-activated chemo-photodynamic immunotherapy based on biodegradable mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(3):917–29. 10.1039/d0bm01452d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]