Abstract

Objectives

The study aimed to assess the usage and impact of a private and secure instance of a generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) application in a large academic health center. The goal was to understand how employees interact with this technology and the influence on their perception of skill and work performance.

Materials and Methods

New York University Langone Health (NYULH) established a secure, private, and managed Azure OpenAI service (GenAI Studio) and granted widespread access to employees. Usage was monitored and users were surveyed about their experiences.

Results

Over 6 months, over 1007 individuals applied for access, with high usage among research and clinical departments. Users felt prepared to use the GenAI studio, found it easy to use, and would recommend it to a colleague. Users employed the GenAI studio for diverse tasks such as writing, editing, summarizing, data analysis, and idea generation. Challenges included difficulties in educating the workforce in constructing effective prompts and token and API limitations.

Discussion

The study demonstrated high interest in and extensive use of GenAI in a healthcare setting, with users employing the technology for diverse tasks. While users identified several challenges, they also recognized the potential of GenAI and indicated a need for more instruction and guidance on effective usage.

Conclusion

The private GenAI studio provided a useful tool for employees to augment their skills and apply GenAI to their daily tasks. The study underscored the importance of workforce education when implementing system-wide GenAI and provided insights into its strengths and weaknesses.

Keywords: clinical informatics, artificial intelligence, medical informatics application

Background and significance

Applications in generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) have become increasingly popular since the release of ChatGPT in 2022. Large language models (LLMs) such as generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) are trained on a large dataset of conversational text that can generate human-like responses to human-written prompts.1,2 The ease of conversing with these models has sparked democratization of use among professionals in various industries. LLMs can be useful in writing code, generating financial reports, or customizing education plans,3 and has been shown to increase worker productivity and performance to provide a competitive advantage.4–6 Applications within the healthcare industry include clinical decision support,7 medical device development,8 and predicting patient outcomes.9 As we learn more about the capabilities of GenAI and GPT, we can start to incorporate it into the tasks of a variety of professions.

Barriers to GenAI use, especially in industries like healthcare, are concerns over the accuracy of the output and the privacy of data entered in public versions of GPT. While the benefits of GenAI are clear, it is still unknown how frequently and for what purpose employees would use this technology in their daily tasks when granted access to a secure instance of ChatGPT, particularly in the healthcare setting.

A health system’s approach to GenAI

Recognizing both the potential advantages and need to ensure safety and security of data and use of GenAI applications, the Medical Center IT (MCIT) department at New York University Langone Health (NYULH) established a secure, private, and managed Azure OpenAI service (GenAI Studio) in the spring of 2023 and began granting widespread access to its employees to experiment and complete projects using GenAI. The intent behind granting access to interested individuals was to leverage the interest and expertise of our community to assess usage, feasibility of various use-cases, and evaluate the perceptions of GenAI among our workforce.10 Our approach was launched with oversight and collaboration from a committee of clinical, informatics, regulatory, and ethical advisors.

Objectives

While the adoption and continued use of GenAI (mostly GPT) is evidence of its value, analysis of how individuals interact with this technology and the ramifications on their perception of skill is essential to continued employee engagement and performance. Lessons from our initiative can inform the approach of other organizations looking to disseminate GenAI technologies. Our study aims to evaluate our users’ experiences with a private and secure instance of a GenAI studio and to describe the challenges and best practices of implementing this technology at scale in a large academic health center.

Methods

After advertising our initiative of implementing a private instance of ChatGPT to the workforce, an introductory webinar was conducted to educate interested employees about GenAI models and their responsible use. This webinar attracted 560 participants, demonstrating the high level of interest in this technology. All employees were then invited to apply for access to our HIPAA compliant, private GenAI studio and experiment with data not allowed within the public instance, such as patient information and intellectual property. Applicants detailed their department, profession, and purpose for accessing the studio. After submission, leaders from the NYULH Department of Health Informatics (DHI) reviewed the applications and granted exploratory access for an anticipated 4 week trial to the studio; grantees also had to attest to a Terms of Use agreement, created in partnership with our legal team from the Technology Opportunities and Ventures unit to ensure responsible use of this tool. Due to bandwidth constraints and concerns about potential costs, the number of users initially was limited. However, as MCIT monitored usage and costs over the first 3 months, we learned that the GenAI studio could support many concurrent users at relatively low cost. Therefore, all requests to the studio for exploratory access were granted once the terms of use were approved. For all users, the DHI Division of Applied Artificial Intelligence Technologies (DAAIT) helps to supervise and guide their exploration of the studio by providing educational materials such as an onboarding presentation and external online links on how to use GenAI, creating a DAAIT website, maintaining a help email address, holding weekly office hours to answer questions, and monitoring usage to ensure adequate bandwidth is available for all users.

Within three weeks of the initial webinar, NYU Langone Health received over 110 access requests. As the number of users of the GenAI Studio has risen, we continue to promote and educate our workforce about AI tools within our healthcare institution through lectures and “prompt-a-thons” in various departments.11 During these events, participants can experiment with our GenAI Studio in teams to solve a problem, similar to a hackathon. Leaders from DHI and DAAIT give lectures in the medical school, business school, and research departments about available AI tools. After our first GenAI “Prompt-a-thon” event, a Webex space was created for participants to share interesting articles or questions they may have regarding the GenAI studio. Applications for exploratory access to the GenAI studio are always available for employees and access is approved automatically once the terms of use are signed. A screenshot of the user interface of our GenAI studio is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Layout of GenAI studio. Users are provided with example prompts and can change the model used (eg, GPT 3.5 vs GPT 4) and settings such as temperature and length of responses. Current tokens used is also displayed to remind users of token limits.

Feedback

Users of our GenAI studio are sent a survey via Qualtrics (later transitioned to ClickUp) to provide details of their primary department, job role (manager vs non-manager), interaction with the GenAI studio, and feedback on their experience about 4 weeks after obtaining access. They answer questions such as “How often do you use your Azure OpenAI account?”, “Please rate your experience using the Azure OpenAI studio.”, and “How often do you use the GenAI studio for writing?” with Likert scales. They are also asked to use free text to describe both successful and unsuccessful use cases of the GenAI studio, along with its strengths and weaknesses. Finally, users are asked about their perceptions of how GenAI is likely to change their own skills of writing and editing, research and reading, data analysis, and idea generation. These major themes were identified by our team after reviewing previous literature of use cases of GenAI.

Statistical analysis

Results from the surveys were extracted to SPSS (Version 29.0.2.0, Armonk, NY) and de-identified prior to analysis by two of our researchers. Responses to Likert scale questions were coded on categorical scales. Pearson correlations and ANOVA analyses were used to evaluate the relationships between frequency of use, prior use of machine learning tools before using the GenAI studio, department role (manager vs non-manager), tasks for which GenAI was used (writing, editing, summarizing, confirmation, data analysis, and idea generation), and perceptions of users of GenAI. Free text answers were summarized and evaluated by two reviewers for broad themes delineating the usages, strengths, and weaknesses of GenAI.

Results

User characteristics and interaction with the GenAI studio

Within six months of implementation, over 1007 individuals applied for and gained access to our NYU Langone GenAI Studio out of 40 000 staff members. The majority of our users are from research and clinical departments, consisting of research advisors and clinicians. We have received 150 responses to our survey, with survey respondents reflecting similar demographics (department and role) to the users of the studio. Respondents were categorized as manager or non-managers based on their indicated job title and if they were responsible for supervising other employees. Most users interacted with the GenAI studio 2-3 times per week. The sources most commonly referenced to learn how to use the application were the introductory webinar followed by the onboarding presentation and external online links provided to applicants. Many survey responders cited the Webex space (created after our first “prompt-a-thon”) as a helpful resource in the “Other” category. See Table 1 for full results of the demographics of our survey population.

Table 1.

User characteristics of survey respondents.

| User characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Department | |

| Clinical | 33 (22.2%) |

| Research | 38 (25.3%) |

| Administrative | 10 (6.67%) |

| Education | 9 (6.00%) |

| IT | 28 (18.7%) |

| Facilities | 2 (1.33%) |

| Finance | 13 (8.67%) |

| Human resources | 1 (0.67%) |

| Other | 16 (10.7%) |

| Resources used | |

| Introductory webinar | 80 |

| Onboarding powerpoint | 61 |

| DAAIT website | 20 |

| Links in introductory email | 45 |

| Help email address | 18 |

| Other (Webex space, eg) | 21 |

| None of the above | 10 |

| Usage of GenAI studio | |

| Many times a day | 19 (13.4%) |

| Daily | 19 (13.4%) |

| 2-3 times a week | 47 (33.3%) |

| Once a week | 11 (7.80%) |

| Every few weeks | 32 (22.7%) |

| Not used yet | 13 (9.22%) |

| Managerial role | |

| Yes | 47 (37.9%) |

| No | 77 (62.1%) |

Overall, users felt well prepared to explore the GenAI studio, with a mean score of 7.02 of 10 in their confidence using the application (1 = low confidence, 10 = high confidence). They also felt the studio was simple to use as it appeared and functioned similarly to ChatGPT (Mean = 4.03, 1= easy, 10 = difficult). Participants rated their experience highly (Mean = 7.4, 1 = poor, 10 = excellent) and would be likely to recommend using the GenAI studio to a colleague (Mean = 7.83, 1 = would not recommend, 10 = extremely likely to recommend).

Technology metrics

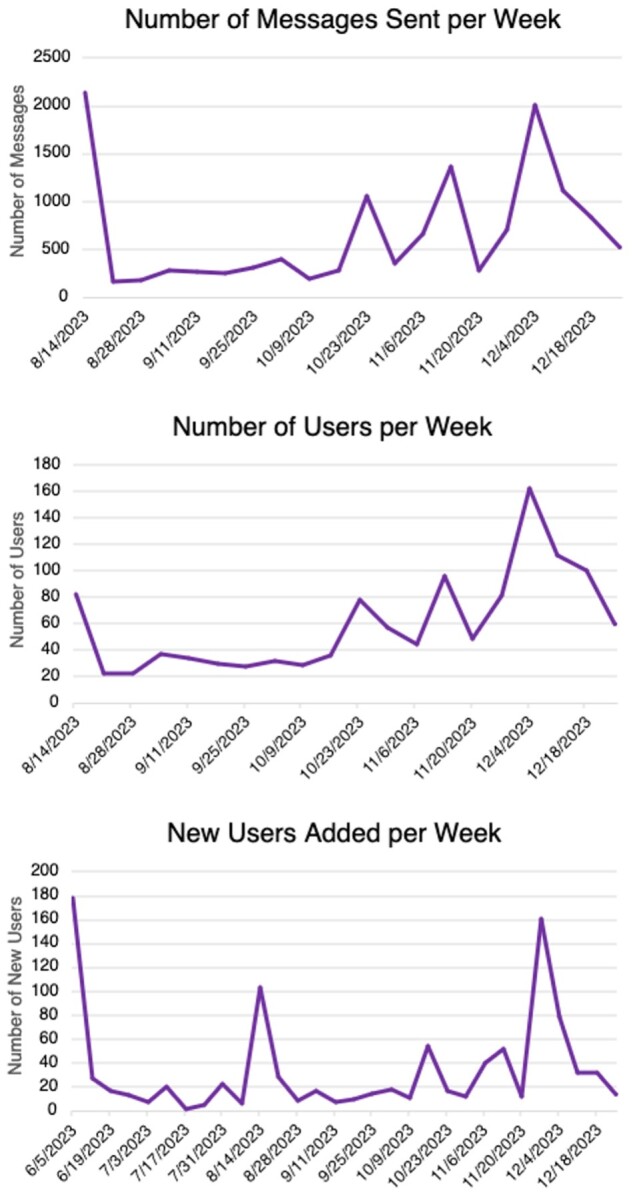

From a technological perspective, 111 960 167 tokens (the atomic unit of large language models) were used in the first 6 months of implementation, costing the institution about $4200. On average, there were 60 users/week submitting about 671 queries/week. There were 34 new users per week on average. The highest number of new users occurred during the week of June 5, shortly after our introductory webinar, with another spike of new users in August around our first enterprise-wide prompt-a-thon and the following in December after subsequent prompt-a-thons (see Figure 2). These patterns highlight how influential educational programs were in catalyzing adoption within the health system despite the substantial public attention that was already given to LLMs in the public press and elsewhere at the time.

Figure 2.

User metrics.

Free text responses

Most respondents provided qualitative input by answering our open-ended survey question (95%). We content-coded responses using thematic analysis, with 3 themes effectively capturing the vast majority (90%) of responses. Table 2 displays the most important themes, with representative quotes to illustrate each theme.

Table 2.

Comments from survey respondents.

| Positive use cases: |

|

| Challenges: |

|

| Feedback: |

| Definitely need more training on how to use it. ChatGPT through the standard portal seems easier to use, perhaps because there are future user interface elements to complicate matters. But definitely need more individualized training. |

Positive impact of the GenAI studio

Users have employed their OpenAI accounts for a diverse range of purposes. The most common uses were: writing, editing, summarizing, data analysis, searching for new information, and idea generation. Examples include creating teaching materials for bedside nurses, drafting email responses and test questions, generating job descriptions, assessing clinical reasoning documentation, and structured query language (SQL) translation. These uses are relevant to diverse domains both within and outside healthcare.

Users highlighted several strengths of the GenAI studio, especially its closed and secure system, providing privacy and compliance with regulations like HIPAA, and ease of access for routine tasks. Some felt that they were able to improve resource and time allocation and accelerate their work pace as they could streamline certain aspects of their jobs while using the GenAI studio. In addition, many participants appreciated the user-friendly interface and its ability to handle redirection well.

Challenges encountered by users

While citing many positive experiences with the GenAI studio, users also provided examples of challenges they faced while interacting with it. Some expressed difficulties with constructing effective prompts to take advantage of GenAI’s capabilities, while others were unsure of token and API limitations. Some struggled to find focused time to explore the GenAI studio within their current work scope. Participants also mentioned occasional hallucinations in generated responses, leaving them uncertain about the validity of provided answers. Despite these challenges, users recognized the potential of GenAI and hoped to address these issues for more successful use in the future. When asked how to improve the experience with the GenAI studio, survey participants expressed the need for more instruction, with better guidance on prompt engineering, practical examples, and a desire to interact with a community of users to share experiences.

Perceptions of OpenAI

When asked what they would use GenAI tools for if available, most stated they would frequently use it for writing documents, editing, summarizing information, and analyzing data. However, they did not perceive that using GenAI for these tasks would reduce the importance of maintaining their own skills in these areas, indicating that their experience suggested that GenAI could not automate these tasks. When asked about factors that would increase or decrease how frequently they use GenAI tools, participants indicated that public release of more capable AI tools, permanent access to the GenAI studio at NYULH, positive reports from colleagues, and studies showing productivity benefits of using AI tools would increase their usage. They did not perceive that media reports on increasing capabilities of AI tools would have any influence on their usage.

Statistical analysis

There were many interesting relationships between job role (manager vs non-manager), frequency of use of the GenAI studio, and perceptions of AI tools. To gain insight into the factors that may lead to higher usage, we compared more frequent users to less frequent users. Frequent users of the GenAI studio reported that their usage would increase based on positive reports from colleagues and studies showing increased productivity from using AI tools. Less frequent users, on the other hand, believed they would be more influenced by positive media reports. We found that participants who interacted with the GenAI studio more frequently were likely to be from clinical or research departments. None of the resources provided (introductory webinar, onboarding presentation, DAAIT website, etc.) were significantly correlated with increased usage, suggesting that user characteristics rather than educational resources predict usage. Frequent users were more likely to feel prepared to use the GenAI studio, and also found it easier to use, had a positive experience with it, and were highly likely to recommend it to a colleague (these sentiments could be antecedents or consequences of usage frequency). High-frequency usage was correlated with using the GenAI studio for editing content and generating new ideas rather than writing or data analysis.

To investigate users’ perceptions of how GenAI is likely to change the nature of their work, users were also asked about their perceptions of how the availability of GenAI tools is likely to change the importance of their own human skills and capabilities. More frequent users anticipated that GenAI would make their mastery of writing and editing, data analysis, and idea generation less important.

Managers and non-managers differed with respect to their beliefs about how GenAI would change their jobs, with managers anticipating more change as a result of the new technology. Managers were more likely to believe that GenAI would reduce the importance of developing skills in writing, editing, summarizing, data analysis, and idea generation relative to non-managers. However, managers and non-managers were similar with respect to the tasks they used GenAI for (ie, editing, idea generation, summarizing, and data analysis), though managers used it for writing significantly more frequently than did non-managers. These groups also did not differ in usage frequency or the factors they thought would lead them to use the GenAI studio more frequently. Managers and non-managers were similar with respect to experience while using GenAI studio, perceived preparedness, ease of use, or willingness to recommend this technology to a colleague. See Table 3 for full correlations and ANOVA results.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations of frequent users and ANOVA testing of managers vs non-managers.a

| Variable | Correlation with frequency of usage | ANOVA testing |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-managers mean | Managers mean | ||

| Frequency of usage | N/A | 3.73 | 3.43 |

| Experience | |||

| Overall experience | 0.45b | 7.38 | 7.40 |

| Preparedness | 0.23b | 7.52 | 7.14 |

| Ease of use | 0.22b | 6.89 | 6.78 |

| Likely to recommend | 0.49b | 7.69 | 7.96 |

| Purpose of use | |||

| Writing | 0.12 | 2.43b | 2.86b |

| Editing | 0.18 | 2.72 | 2.70 |

| Summarizing | 0.089 | 2.90 | 2.72 |

| Confirmation | 0.12 | 2.25 | 2.35 |

| New ideas | 0.32b | 2.28 | 2.49 |

| Data analysis | 0.18 | 2.54 | 2.44 |

| Perceptions of AI | |||

| Decrease skills in writing/editing | 0.20b | 2.35 | 2.77 |

| Decrease skills in research/reading | 0.18 | 2.58b | 3.02b |

| Decrease skills in data analysis | 0.23b | 2.52b | 2.91b |

| Decrease skills in idea generation | 0.23b | 2.48b | 2.93b |

| Influences to increase use of GenAI studio | |||

| More GenAI tools released | 0.19b | 2.86 | 2.77 |

| Permanent access to GenAI studio | 0.28b | 3.23 | 3.30 |

| Positive reports from colleagues | 0.22b | 2.81 | 3.00 |

| Positive reports from media | 0.18 | 2.46 | 2.63 |

| Positive reports from studies | 0.12 | 2.84 | 3.12 |

Scales for questions: Overall experience (1 = poor, 10 = excellent); Preparedness (1 = not prepared, 10 = extremely prepared); Ease of Use (1 = very difficult, 10 = very easy); Likely to Recommend (1 = would not recommend, 10 = extremely likely to recommend); Frequency of Usage (0 = Not Used, 5 = Many times a day); Purpose of Use (0 = Never, 4 = Frequently); Perceptions of AI (0 = No Change, 4 = Significant Change); Influences to Increase Use of GenAI Studio (0 = None, 4 = Significant).

P < .05.

Future directions

Users cited a diverse array of tasks they hope GenAI can undertake in the future. These tasks include streamlining documentation and manuscript processes, developing algorithms, creating educational content, facilitating recruitment and HR processes, automated extraction of billable data, enhancing patient experience and satisfaction, and handling legal and contractual writing. This expansive list reflects the multifaceted expectations users have for GenAI, showcasing its potential impact across diverse fields and functionalities. Users anticipate that GenAI will make individual people and processes more efficient and productive, but they do not view the technology as bringing about large-scale disruptive change in what work is performed in healthcare the way that e-commerce changed the retail industry or mechanization changed production.

Discussion

As GenAI continues to grow both in its capabilities and usage in many industries, NYULH implemented a secure and HIPAA-compliant instance of ChatGPT to allow our workforce to experiment with its capabilities and use it in their daily tasks without incurring a prohibitive cost to the institution. Our study is the first of its kind to show the potential impact of GenAI in a large academic health center, as we explored how employees would use this tool and their perceptions of GenAI use in their professions, along with the challenges our institution faced at implementing this technology at scale.

Employee engagement

We observed high attendance at our introductory webinar and the number of users with access to this studio has steadily increased since its initiation. There are many factors that have contributed to the success of our initiative. The leadership of the DHI, DAAIT, and MCIT have endorsed the use of this technology to employees as they recognize its potential for increasing efficiency and creativity in our workforce, and that these benefits can be achieved at a low cost. We have publicized the capabilities of the GenAI studio to our employees through “prompt-a-thon” events with guidance by the DAAIT in different departments. These prompt-a-thons gave participants temporary access to the GenAI studio to creatively execute prompts to help answer questions. We hosted the first prompt-a-thon event in August 2022, which was well received by our participating staff,11 and have had several events since then. Although the initial adoption rate of the GenAI studio was low in relation to total staff (1007 individuals out of 40 000 staff members), this still represents significant uptake for an innovative IT tool not required as part of a user’s daily work function. We have found that continuous engagement with our workforce through roadshows and lectures on the benefits of AI tools increases utilization, as shown by large increases in the number of users and messages sent per week after events. We also believe that users’ positive experiences will encourage their colleagues to apply for access to the GenAI studio and experiment with its capabilities.

GenAI studio design

Many features of the design and interface of our GenAI studio led to our users’ positive experience with the technology, including that it was simple to use, and would recommend it to a colleague. It is important for any institution who wishes to implement a private GenAI studio to incorporate features such as fine-tuning with feedback (users can iterate prompts and converse with the chatbot to refine its answers), personalization (temperature, response length, etc.) and context retention,12 as many users appreciated the GenAI studio’s ability to remember prompts so they could return and continue their work at another time. They also mentioned how they could customize their prompts so the chatbot will generate a desired style of output every time. A recent study found that satisfaction with a chatbot depends heavily on its ability to understand a customer’s needs and provide accurate information,13 and since our GenAI studio can adapt itself to accomplish these needs depending on its user, we would expect its popularity to continue to grow in our workforce. Additionally, the simple design of our interface (shown in Figure 1) is similar in both appearance and function to ChatGPT, which many individuals are already familiar with and appreciate. Respondents’ open-ended comments also cited the unique security of our interface in that they could input sensitive and proprietary information that is often present in the daily tasks of individuals at a healthcare organization. While this was reassuring to users and likely contributed to their positive experience, we felt it was still important to have users sign a Terms of Use agreement that outlined responsible practices and applications of the GenAI studio prior to obtaining access. Our DAAIT staff monitors the usage and prompt inputs into the studio daily to troubleshoot any issues our participants may be experiencing. We found that having dedicated staff to maintain and update the interface, as well as answer questions from users regarding the functionality of the studio, was extremely beneficial to our efforts.

Perceptions of AI in an academic health center

Several healthcare organizations in addition to NYU have increased their use of AI tools in partnership with large technology companies as they recognize their potential for improved healthcare delivery. We found that AI tools are also relevant to departments outside of clinical care, as our workforce used our private instance of ChatGPT for the tasks of writing, editing, and summarizing in research, IT, and financial departments.14 Since GenAI can ingest various modes of input to create a new, simple, and well-worded response to a query,15,16 it can be applied to many functions in our daily tasks to streamline work and reduce our cognitive burden. Unsurprisingly, then, frequent users and managers believed that the skills of writing/editing, data analysis, and idea generation would be less important in their jobs in the future. One explanation for this phenomenon is outlined by Davenport and Mittal: although GenAI tools can write and summarize material, they still require human input before and after to successfully accomplish a task. Humans must be able to produce and revise detailed and creative prompts to generate a desired output, and they must also be able to evaluate the results to fine-tune them.15 Therefore, instead of focusing on reading, writing, or data analysis specifically, our users now must think of how to create more effective prompts for the GenAI studio to complete these tasks for them. As the capabilities of GenAI increase over time, we expect members of the workforce to continue to augment and adapt their skills in “prompt engineering” to further integrate AI tools in their tasks.

Lessons learned

While there were many successful use cases of our GenAI studio, our users outlined several challenges and suggestions for improvement. The institution faced challenges early in the initiative, especially the need for workforce education on how to use the studio. We experienced similar issues when conducting our first prompt-a-thon event, where participants cited “blank page anxiety” as they did not know how to begin their exploration of our private instance of ChatGPT.11 It is important to provide individuals with practical examples and possibly live demonstrations of this new technology, as those with little to no experience with it can have more concerns about its capabilities and fear of the unknown. NYULH initially employed various modes of instruction, such as webinars, onboarding materials, and a help email address. We also created a Webex space in which members could post questions and interesting articles to create a community of our GenAI studio users. These resources were used widely amongst our survey respondents, and we will continue to revise them to address our users’ needs.

New user onboarding was another process that we continuously improved to promote adoption. Originally, we sent our terms of use agreement after the provider requested access. We updated the request form to incorporate those terms up front. Furthermore, with our original go live, users submitted new GenAI projects requests through one process and then requested access to NYU GPT through another process. We learned that GenAI exploration is a critical dependency for any new project request and, consequently, enabled new users to simultaneously request access and submit a new project, further driving usage.

While our study is novel in its description of our implementation of a private and HIPAA compliant instance of ChatGPT at a large academic health center, there were several limitations. The response rate to our survey was low and may have been subject to selection bias due to the length of the survey. It would also be interesting to gather more information from our users, including their past experience with GenAI tools, their gender, and their age to correlate these factors to their usage and perceptions of GenAI.

Conclusion

Our private instance of ChatGPT provided our employees a helpful tool to augment their skills with GenAI and apply it to their daily tasks. We learned the importance of workforce education when implementing a system wide GenAI studio and its strengths and weaknesses for employees.

Contributor Information

Kiran Malhotra, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Department of Ophthalmology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY 10017, United States.

Batia Wiesenfeld, Department of Management and Organization, NYU Stern School of Business, New York, NY 10012, United States.

Vincent J Major, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016, United States.

Himanshu Grover, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States.

Yindalon Aphinyanaphongs, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016, United States.

Paul Testa, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Department of Emergency Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016, United States.

Jonathan S Austrian, New York University (NYU) Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Medical Center IT, Department of Health Informatics, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY 10016, United States; Department of Medicine, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY 10016, United States.

Author contributions

Kiran Malhotra (corresponding author) performed data acquisition, data extraction, data analysis, manuscript writing, and editing. Batia Wiesenfeld contributed data analysis, manuscript writing, and editing. Vincent J. Major performed conception and design of work, experimental design, and manuscript editing. Himanshu Grover performed data extraction, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Yindalon Aphinyanaphongs contributed to conception and design of work and experimental design. Paul Testa performed conception and design of work and experimental design. Jonathan S. Austrian performed conception and design of work, experimental design, manuscript writing, manuscript editing, and approval of version to be published.

Funding

Batia Wiesenfeld and Yindalon Aphinyanaphongs have received funding from the National Science Foundation Grant #2129076.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Lecler A, Duron L, Soyer P.. Revolutionizing radiology with GPT-based models: current applications, future possibilities and limitations of ChatGPT. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2023;104:269-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GPT-4. https://openai.com/gpt-4

- 3. Deloitte. The Consumer Generative AI Dossier—Deloitte US. Deloitte; 2023.

- 4. Kanbach DK, Heiduk L, Blueher G, et al. The GenAI is out of the bottle: generative artificial intelligence from a business model innovation perspective. Rev Manag Sci. 2024;18:1189-1220. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dell'Acqua F, McFowland E, Mollick ER, et al. Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 24-013. 2023.

- 6. Brynjolfsson E, Li D, Raymond LR.. Generative AI at Work. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2023.

- 7. Siru L, Wright AP, Patterson BL, et al. Using AI-generated suggestions from ChatGPT to optimize clinical decision support. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2023;30:1237-1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li S, Guo Z, Zang X.. Advancing the production of clinical medical devices through ChatGPT. Ann Biomed Eng. 2024;52:441-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pieszko K, Hiczkiewicz J, Budzianowski J, et al. Clinical applications of artificial intelligence in cardiology on the verge of the decade. Cardiol J. 2021;28:460-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Austrian J, Aphinyanaphongs Y.. Empowering our health system with a private and secure GPT service. Medium. 2023;27. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Small WR, Malhotra K, Major VJ, et al. The first generative AI Prompt-A-Thon in healthcare: a novel approach to workforce engagement with a private instance of ChatGPT. PLOS Digit Health. 2024;3:e0000394. 10.1371/journal.pdig.0000394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12. Nazir A, Wang Z.. A comprehensive survey of ChatGPT: advancements, applications, prospects, and challenges. Meta Radiol. 2023;1:100022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Abdelkader OA. ChatGPT's influence on customer experience in digital marketing: investigating the moderating roles. Heliyon. 2023;9:e18770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. George B, Wooden O.. Managing the strategic transformation of higher education through artificial intelligence. Admin Sci. 2023;13:196. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Davenport TH, Mittal N.. How generative AI is changing creative work. Harvard Business Rev. 2023;15. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hosseini M, Gao CA, Liebovitz DM, et al. An exploratory survey about using ChatGPT in education, healthcare, and research. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0292216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.