Abstract

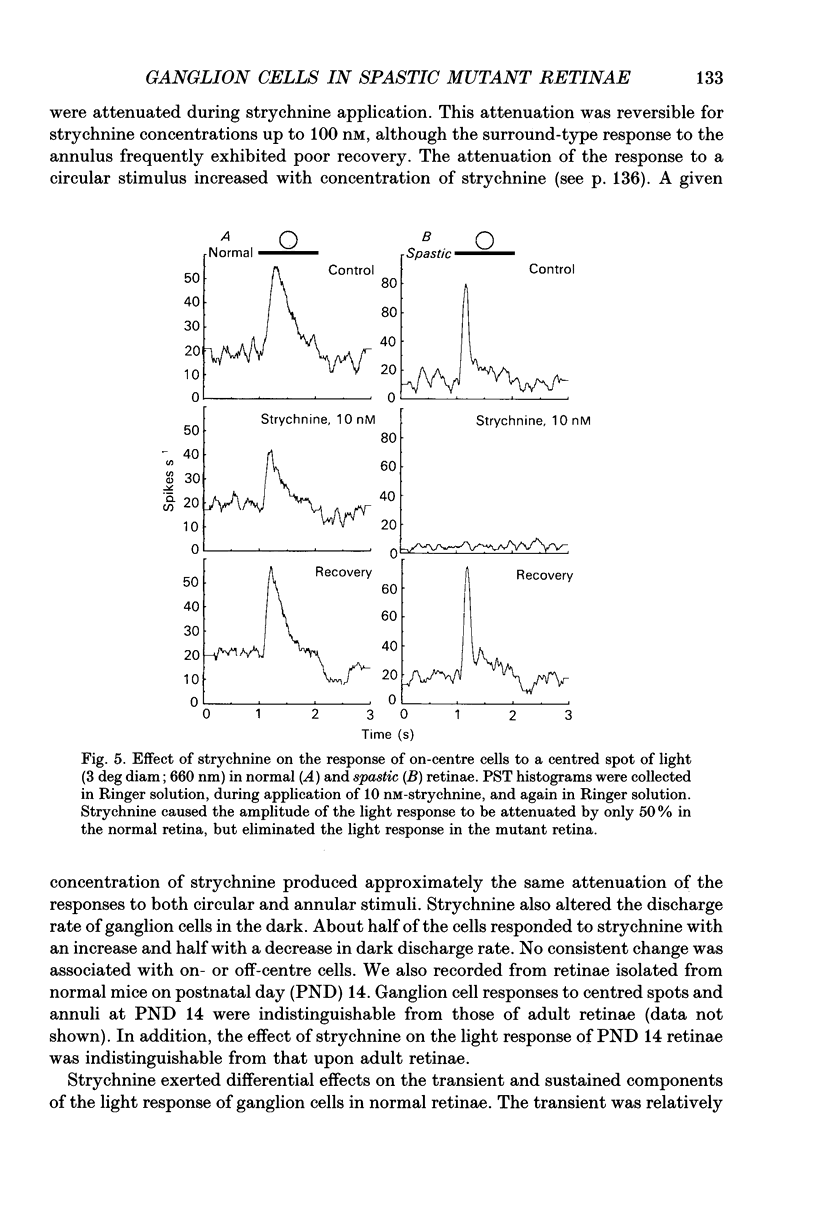

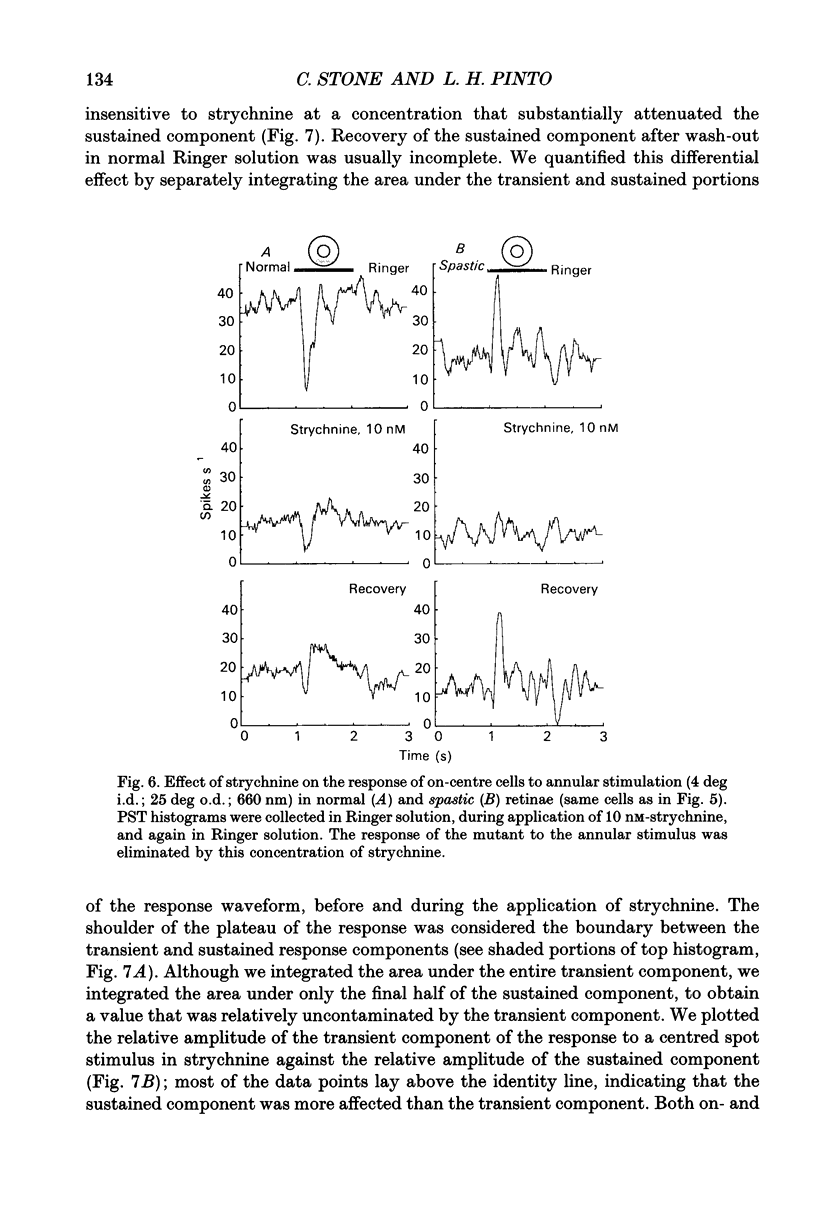

1. We examined the receptive field properties of retinal ganglion cells in the isolated, superfused retinae of spastic mutant mice (B6C3Fe-spa/spa) that did not have the retinal degeneration (rd) phenotype. Glycine receptor density in the spastic mutant is greatly reduced in all areas of the CNS that have been examined. Phenotypically normal litter-mates were used as controls. Radial sections from the retinae of both spastic and normal animals were examined with light and electron microscopy and no differences were observed. The planimetric density of the cell bodies in the inner nuclear layer did not differ between the normal and mutant animals, about 400 cm-2. The absolute dark-adapted sensitivity of spastic ganglion cells was greater (271 +/- 69.0 impulses quanta-1 rod-1) than that of normal ganglion cells (47.7 +/- 10.4 impulses quanta-1 rod-1; P < 0.01). 2. Extracellular recordings of retinal ganglion cell responses to circular and annular stimuli, centred on the receptive field, were used to construct peri-stimulus-time histograms. In normal retinae, an annular stimulus elicited a response that was characteristic of the surround response mechanism of receptive fields with antagonistic centre-surround organization. In the mutant retina, annular stimuli did not elicit a surround-type response; instead, a centre-type response was recorded. 3. Illumination of the receptive field periphery attenuated centre-type responses in ganglion cells from both spastic and normal retinae. Centred circular stimuli of various areas (14, 35, 78, 122, 235, 783 deg2) were presented to the receptive fields. For mutant and normal ganglion cells, the response to the largest stimulus was smaller than that to an intermediate-sized stimulus. 4. The effect of strychnine, a glycine receptor antagonist, on the response to circular stimuli was examined. Very low concentrations of strychnine attenuated the light response in mutant retinae (apparent inhibitory binding constant KI = 8.1 x 10(-13) M). In normal animals, the light response was also attenuated by strychnine, but the apparent KI was much higher (apparent KI = 1 x 10(-7) M). 5. In normal ganglion cells, the sustained component of the light response was much more attenuated by strychnine than was the transient component. Interestingly, ganglion cells from spastic retinae did not exhibit a sustained component, even at stimulus luminances that evoked responses near threshold.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 400 WORDS)

Full text

PDF

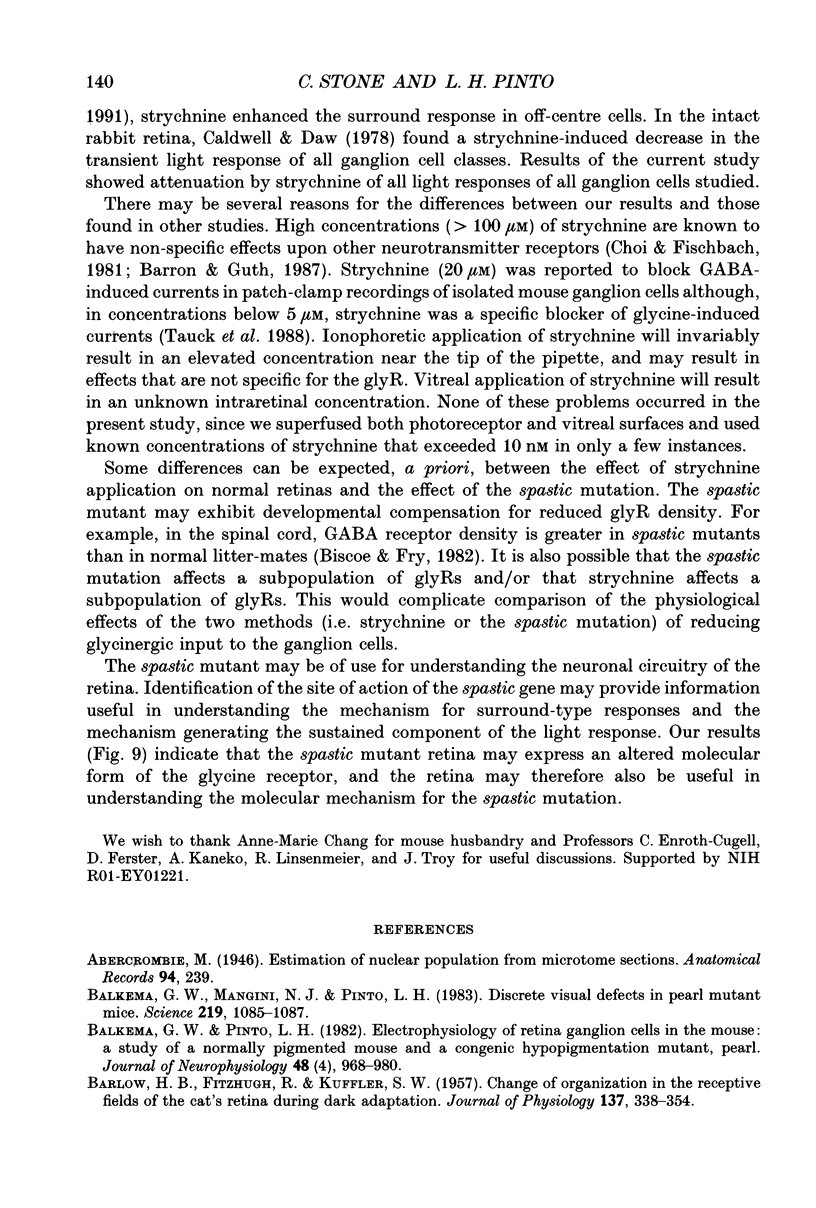

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BARLOW H. B., FITZHUGH R., KUFFLER S. W. Change of organization in the receptive fields of the cat's retina during dark adaptation. J Physiol. 1957 Aug 6;137(3):338–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkema G. W., Jr, Pinto L. H. Electrophysiology of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse: a study of a normally pigmented mouse and a congenic hypopigmentation mutant, pearl. J Neurophysiol. 1982 Oct;48(4):968–980. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.4.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkema G. W., Mangini N. J., Pinto L. H. Discrete visual defects in pearl mutant mice. Science. 1983 Mar 4;219(4588):1085–1087. doi: 10.1126/science.6600521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker C. M., Hermans-Borgmeyer I., Schmitt B., Betz H. The glycine receptor deficiency of the mutant mouse spastic: evidence for normal glycine receptor structure and localization. J Neurosci. 1986 May;6(5):1358–1364. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-05-01358.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J., Duchen M. R. Synaptic physiology of spinal motoneurones of normal and spastic mice: an in vitro study. J Physiol. 1986 Oct;379:275–292. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biscoe T. J., Fry J. P. Some pharmacological studies on the spastic mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1982 Jan;75(1):23–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1982.tb08754.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowes C., van Veen T., Farber D. B. Opsin, G-protein and 48-kDa protein in normal and rd mouse retinas: developmental expression of mRNAs and proteins and light/dark cycling of mRNAs. Exp Eye Res. 1988 Sep;47(3):369–390. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(88)90049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell J. H., Daw N. W. Effects of picrotoxin and strychnine on rabbit retinal ganglion cells: changes in centre surround receptive fields. J Physiol. 1978 Mar;276:299–310. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen E. P., Linsenmeier R. A. Centre components of cone-driven retinal ganglion cells: differential sensitivity to 2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid. J Physiol. 1989 Dec;419:77–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi D. W., Fischbach G. D. GABA conductance of chick spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion neurons in cell culture. J Neurophysiol. 1981 Apr;45(4):605–620. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland B. G., Enroth-cugell C. Quantitative aspects of sensitivity and summation in the cat retina. J Physiol. 1968 Sep;198(1):17–38. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupland R. E. Determining sizes and distribution of sizes of spherical bodies such as chromaffin granules in tissue sections. Nature. 1968 Jan 27;217(5126):384–388. doi: 10.1038/217384a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLean A., Munson P. J., Rodbard D. Simultaneous analysis of families of sigmoidal curves: application to bioassay, radioligand assay, and physiological dose-response curves. Am J Physiol. 1978 Aug;235(2):E97–102. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.2.E97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enroth-Cugell C., Robson J. G., Schweitzer-Tong D. E., Watson A. B. Spatio-temporal interactions in cat retinal ganglion cells showing linear spatial summation. J Physiol. 1983 Aug;341:279–307. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1983.sp014806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher L. J. Development of synaptic arrays in the inner plexiform layer of neonatal mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 1979 Sep 15;187(2):359–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.901870207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollyfield J. G. On presentation of the Friedenwald Award in ophthalmology to Matthew M. LaVail. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Nov;21(5):632–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda H., Sheardown M. J. Transmitters mediating inhibition of ganglion cells in the cat retina: iontophoretic studies in vivo. Neuroscience. 1983 Apr;8(4):837–853. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R. J. Involvement of glycinergic neurons in the diminished surround activity of ganglion cells in the dark-adapted rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 1991 Jan;6(1):43–53. doi: 10.1017/s0952523800000894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäger J., Wässle H. Localization of glycine uptake and receptors in the cat retina. Neurosci Lett. 1987 Mar 31;75(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUFFLER S. W. Discharge patterns and functional organization of mammalian retina. J Neurophysiol. 1953 Jan;16(1):37–68. doi: 10.1152/jn.1953.16.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolb H., Nelson R. Rod pathways in the retina of the cat. Vision Res. 1983;23(4):301–312. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVail M. M., Battelle B. A. Influence of eye pigmentation and light deprivation on inherited retinal dystrophy in the rat. Exp Eye Res. 1975 Aug;21(2):167–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(75)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsenmeier R. A., Frishman L. J., Jakiela H. G., Enroth-Cugell C. Receptive field properties of x and y cells in the cat retina derived from contrast sensitivity measurements. Vision Res. 1982;22(9):1173–1183. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(82)90082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill E. G., Ainsworth A. Glass-coated platinum-plated tungsten microelectrodes. Med Biol Eng. 1972 Sep;10(5):662–672. doi: 10.1007/BF02476084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchiner J. C., Pinto L. H., Vanable J. W., Jr Visually evoked eye movements in the mouse (Mus musculus). Vision Res. 1976;16(10):1169–1171. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(76)90258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller F., Wässle H., Voigt T. Pharmacological modulation of the rod pathway in the cat retina. J Neurophysiol. 1988 Jun;59(6):1657–1672. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.6.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pourcho R. G., Goebel D. J. A combined Golgi and autoradiographic study of (3H)glycine-accumulating amacrine cells in the cat retina. J Comp Neurol. 1985 Mar 22;233(4):473–480. doi: 10.1002/cne.902330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H. Pharmacological and morphological differences between X- and Y-type ganglion cells in the cat's retina. Vision Res. 1983;23(11):1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(83)90105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito H. The effects of strychnine and bicuculline on the responses of X- and Y-cells of the isolated eye-cut preparation of the cat. Brain Res. 1981 May 11;212(1):243–248. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S., Tachibana M., Kaneko A. Effects of glycine and GABA on isolated bipolar cells of the mouse retina. J Physiol. 1990 Feb;421:645–662. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp017967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauck D. L., Frosch M. P., Lipton S. A. Characterization of GABA- and glycine-induced currents of solitary rodent retinal ganglion cells in culture. Neuroscience. 1988 Oct;27(1):193–203. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W. F., Heller A. H. Glycine receptor alteration in the mutant mouse spastic. Nature. 1982 Aug 12;298(5875):655–657. doi: 10.1038/298655a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. A., Gherson J., Fisher L. J., Pinto L. H. Synaptic lamellae of the photoreceptors of pearl and wild-type mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985 Jul;26(7):992–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. A., Pinto L. H., Gherson J. The retinal pigment epithelium of wild type (C57BL/6J +/+) and pearl mutant (C57BL/6J pe/pe) mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985 May;26(5):657–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wässle H., Schäfer-Trenkler I., Voigt T. Analysis of a glycinergic inhibitory pathway in the cat retina. J Neurosci. 1986 Feb;6(2):594–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00594.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]