Abstract

This work presented an overview of greener technologies for realizing everyday fabrics with enhanced antibacterial activity, flame retardancy, water repellency, and UV protection. Traditional methods for improving these qualities in textiles involved dangerous chemicals, energy and water‐intensive procedures, harmful emissions. New strategies are presented in response to the current emphasis on process and product sustainability. Nanoparticles (NPs) are suggested as a potential alternative for hazardous components in textile finishing. NPs are found to efficiently decrease virus transmission, limit combustion events, protect against UV radiation, and prevent water from entering, through a variety of mechanisms. Some attempts are made to increase NPs efficiency and promote long‐term adherence to textile surfaces. Traditional wet finishing methods are implemented through a combination of advanced green technologies (plasma pre‐treatment, ultrasound irradiations, sol‐gel, and layer‐by‐layer self‐assembly methods). The fibrous surface is activated by adding functional groups that facilitate NPs grafting on the textile substrate by basic interactions (chemical, physical, or electrostatic), also indirectly via crosslinkers, ligands, or coupling agents. Finally, other green options explore the use of NPs synthesized from bio‐based materials or hybrid combinations, as well as inorganic NPs from green synthesis to realize ecofriendly finishing able to provide durable and protective fabrics.

Keywords: nanoparticles, sustainability, textile finishing

This overview presented nanoparticles (NPs) as a potential green alternative to hazard chemicals in wet textile finishing to provide antibacterial, flame, water, and UV protection. Upgrades to traditional processes included more innovative eco‐friendly technology to improve textile/NPs adhesion and product durability. Other strategies focused on green synthesized NPs and/or bio‐based materials as NPs or coatings.

1. Introduction

Textiles are essential for individuals of all ages, professions, and genders in everyday life and/or industrial sectors. Textiles are used for dressing and clothing,[ 1 ] in personal protective garments,[ 2 ] in transportation means (automobiles, shipping, railways, and aerospace),[ 3 ] in house interiors (furnishing upholstery, mattresses, curtains, and drapes),[ 4 ] or in geotextile membranes,[ 5 ] in filtration,[ 6 ] in ropes and upholstery, in conveyor belts.[ 7 ]

Textile fibers are broadly classified into two types: natural and synthetic fibers. Natural fibers are derived from animals, vegetables/plants, or minerals, and include wool, silk, cotton, linen, hemp. Synthetic fibers, also known as man‐made fibers, are generally made up of synthetic petroleum‐based polymers such as polyamide (PA), polyester (PET), and polypropylene (PP).[ 8 ]

Synthetic or natural textiles should withstand trough harsh working conditions in a variety of environments, including technical applications, and everyday indoor and outdoor activities.

Over time, improvements in these fields have become necessary. Extensive research has been performed to develop novel textile products, fibers and composites,[ 9 , 10 ] fiber blends,[ 11 , 12 ] and textile surface modification by physical and chemical approaches,[ 13 , 14 ] to improve appearance and functional properties.[ 15 ]

The recent interest on clean lifestyles, reducing carbon and water footprints, and meeting consumer requirements while addressing sustainability challenges led to a shift toward cleaner production and green chemistry.[ 16 ] Several strategies to improve the utility, sustainability, and performance of the next generation of textiles have been considered,[ 17 ] including the use of nanotechnologies;[ 15 ] the operation of recovery, reuse, and recycling of post‐consumer garments;[ 18 ] the use of bio‐based polymers in textile manufacturing;[ 19 , 20 ] advanced dyeing and printing techniques;[ 21 ] ecofriendly techniques for textile finishing;[ 16 , 22 ] the use of modern biotechnology with enzymes, plant extracts, and natural colorants.[ 23 , 24 ]

Nanotechnology and textiles can be combined in a variety of ways, such as applying a colloidal solution or ultrafine dispersion of nanomaterials to a textile material (nano‐finishing), depositing a thin layer on the textile surface (nanocoating), developing nanofibers through electrospinning techniques, and producing nanocomposites for fibers.[ 25 , 26 ]

Nanomaterials have emerged as a crucial component in the development of textile finishing. The use of nanomaterials in textile treatment resulted in unique mechanisms of action and/or production of specific microstructures that inhibited the entrance of water, oxygen, and corrosives, increased antiflame characteristics, mechanical properties, UV protection, and thermal stability.[ 27 ]

Nanoparticles (NPs) may be proposed as an effective and long‐term alternative to existing textile finishing agents that have been shown to be harmful to human and environmental health, such as quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), triclosan, poly(hexamethylene biguanide (PHMB) used for microbial protection,[ 28 ] organobromine‐based and halogenated species for flame retardancy effects,[ 29 ] and fluorocarbons for water repellency properties.[ 30 ] Pad‐dry‐cure or general impregnation methods like dip coating, spray coating, hydrothermal coating, and immersion are traditional wet finishing treatments for introducing NPs into textiles.[ 25 , 31 ] However, immobilizing NPs into fabrics remains a challenge to be addressed.[ 32 ] Risks related to the release of NPs from commercial textiles during their use and washing were ascribed to several factors including size, purity, surface area, porosity, textile material type, washing environment (water quality, detergent, and washing machine) and possible surface modifications or treatments to improve nanoparticles binding.[ 33 ] The accidental discharge of NPs into the environment reduces the effectiveness of the textile treatment and, more crucially, it raises concerns about human and ecological health.

Many reviews have previously been conducted in the areas of NPs and textile performance. Some reviews included a thorough list of NPs (inorganic and/or organic) used in textile treatments,[ 32 , 34 ] as well as a list of potential outcomes[ 15 ] and applications.[ 32 , 35 ] Other studies have focused solely on specific nanomaterials incorporated into textile finishing[ 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] or functionalities such as antimicrobial[ 40 ] and self‐cleaning effects,[ 41 ] flame retardancy,[ 42 ] or specific purposes such as wound dressings,[ 37 ] hemostatic activity, and drug delivery,[ 43 ] wearable electronic and smart textiles.[ 44 , 45 , 46 ] Other overviews have introduced new ecofriendly approaches such as sol‐gel,[ 47 , 48 ] plasma treatment,[ 16 , 22 , 49 ] layer‐by‐layer self‐assembly,[ 50 ] and sonoprocesses[ 51 ] for developing finishing techniques that use fewer chemicals, need low‐temperature treatment, are safe for human health, and can be tailored to specific applications. The present emphasis on green NPs synthesis using natural compounds[ 52 , 53 , 54 ] to reduce the environmental toxicity and biological dangers associated with NPs production and reducing agents[ 25 , 55 ] became another step toward green textile finishing technologies. Researchers focused also on adding functionalities to textile surfaces through the applications of biopolymers in the form of nanoparticles,[ 56 ] or hybrid combinations of organic and inorganic nanomaterials.

Considering the recent willingness and consciousness to promote product and process sustainability, the goal of this review was to provide a global perspective on efforts to promote the eco‐friendliness of wet textile finishing involving nanoparticles for daily applications. Initiatives aimed to improve the durability of nanomaterials on textile substrates, reduce water, energy, and processing time, develop nano‐based finishing with lower toxicity and biodegradability using bio‐based polymers and green chemistry. Standard wet methods for incorporating NPs onto textile substrates (e.g., pad‐dry‐cure) were described, as well as more advanced technologies such as sol‐gel, layer‐by‐layer self‐assembly, plasma, and sonoprocesses, to facilitate NPs synthesis, improve attachment to the fabric, and reduce agglomeration. Finally, examples of NPs from green synthesis, in which reducing agents were replaced by green components from biomass waste, plant‐based extracts or microbes, or hybrid combinations of inorganic‐organic components, applied to textile surfaces, were also presented.

The following table of contents was developed involving: i) illustration of useful properties of textiles in everyday life, ii) presentation of main inorganic NPs, the properties and uses; iii) a description of the action modes of NPs to increase the primary textile properties such as antibacterial/antiviral activities, UV blocking, flame retardancy, and water repellence; iv) a description of the most common wet textile finishing methods (i.e., pad‐dry‐cure) to prepare functionalized textiles incorporating NPs and advanced technologies that included sol‐gel, layer‐by‐layer, plasma, and sonochemical approaches; v) progress in synthesis and applications of nano‐based textile wet finishing, also involving bio‐based nanoparticles or hybrid combinations of inorganic and organic components v) presentation of green NPs‐based finishing for textiles in which the NPs were synthesized using more environmentally friendly components such as those derived from plants, microorganisms, and/or biomass waste.

The search for contributions to be included was carried out using Scopus and ScienceDirect as the main databases. From 1999 to 2024, more than 1700 contributions were obtained from these sources using the major keywords “green”, “finishing”, “sustainable”, “textiles”, and “nanoparticles”. Taking the last five years of research as a reference period, there were ≈1200 contributions. After excluding the encyclopedia, book chapters (which are nearly always not openly downloadable and accessible) and conference proceedings, only review articles (≈400) and research articles (≈400) were considered. Based on title and abstract content, more than 100 articles were selected. Papers on wearable electric heating textiles, smart and high‐performance textiles were excluded. The collection covered green advances in wet finishing technologies and nanoparticles for everyday fabrics, with a focus on main useful properties such as antibacterial, UV‐blocking, flame‐retardant, hydrophobic, and self‐cleaning.

2. Main Useful Properties of Textiles in Everyday Life

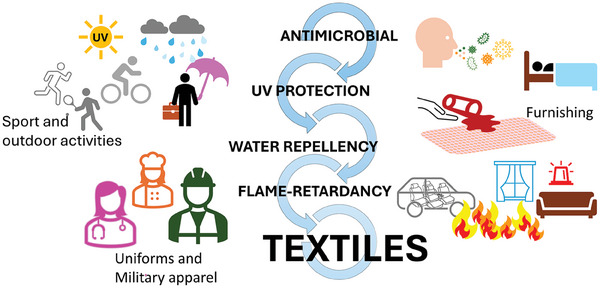

Textiles should generally meet durability and strength criteria, as well as colorfastness and visual appeal. They should have practical attributes like protection against germs and UV radiation, flame resistance. Other properties should include resistance to mechanical stress (tensile, tear, puncture, cutting, and abrasion), and contact with water, oils, or chemicals.[ 57 , 58 , 59 , 60 ] (Figure 1 )

Figure 1.

Useful properties of fabrics in everyday life.

The spread of bacteria and viruses through contaminated materials highlights the importance of practical clothing to safeguard personnel. All apparel and home textiles, such as socks, sportswear, and work clothes, as well as mattresses, floor coverings, and shoe linings, are susceptible to hygiene difficulties during routine everyday use. Outdoor textiles are constantly exposed to bacteria and microbes and textiles commonly used in hospitals and hotels may spread infections.[ 61 ]

When exposed to fire, textiles burn quickly generating a large amount of heat and smoke and causing significant damage to life and properties. In the furniture and clothes industry, tiny causes frequently result in fires that have disastrous consequences. Due to increased safety concerns, fire protection is becoming more vital in uniforms and military apparel, children's sleepwear, sport clothing, seating, carpets, and other furnishings for road vehicles, railways, aircraft, and sea vessels.[ 4 ]

Water‐resistant textiles promote comfort in outdoor activities, cycling, or walking to work. The ability to resist other liquids provides vital safety in harsh circumstances, such as when handling hazardous liquids like acids or oils in chemical processes.[ 30 ]

Textiles play an essential role in UV protection. As the intensity of ultraviolet (UV) radiation grows year after year, effective UV‐blocking technologies to preserve human skin, plastics, lumber, and other materials are urgently needed. UV rays can produce chemical changes in skin cells (DNA), leading to carcinogenesis, immunological suppression, and aging, as well as acute reactions (erythema, sunburn, skin pigmentation).[ 62 ] Polymer‐based textiles are often damaged by UV light. This means that UV rays can disrupt chemical bonds, altering the properties and reducing durability. Certain textile applications, such as outdoor ones, may require durability and weathering resistance due to exposure to UV radiation, water, humidity, and temperature.[ 63 , 64 ]

3. Main Inorganic Nanoparticles and Their Uses

Nanomaterials can be categorized into four types: i) 0D (all dimensions <100 nm) such as quantum dots, onions, hollow spheres; ii) 1D (at least one dimension <100 nm) such as nanowires, nanorods, nanotubes, nanobelts, nanoribbons; iii) 2D (two dimensions >100 nm) such as nano‐plates and nanosheets; and iv) 3D (all dimensions >100 nm).[ 27 , 44 ]

Silver nanoparticles (Ag‐NPs) are lethal for a wide spectrum of microorganisms but less toxic to human cells, with long‐term stability and enhanced dyeability. Ag‐NPs are well known for the self‐cleaning and antibacterial properties.[ 65 ] Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2‐NPs) are the preferred inorganic UV‐blocking agent among conventional semiconductors due to its excellent photocatalytic activity, biological stability, insolubility in water, acid and base environment, resistivity toward corrosion.[ 66 , 67 ] Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO‐NPs) have numerous applications, including semiconductors, gas sensing, UV protection, photodegradation. ZnO‐NPs are widely employed in biological sciences due to their high protein binding capacity and ease of penetration into human cells.[ 68 ] In the textile industry, they are well‐known for their capacity to defend against UV irradiation, bacteria, fungal, microwave, electromagnetic radiation, water, and fire.[ 69 ] Copper nanoparticles (Cu‐NPs) showed unique qualities, including superior electric and thermal conductivity, photocatalytic behavior, superior plasmonic resonance, and nonmagnetic nature, make them highly useful in electronics, metallurgy, and other industrial uses.[ 70 ] Manganese dioxide nanoparticles (MnO2‐NPs) are popular catalysts due to the low toxicity, high efficiency, and reactivity. The adjustable valence states of Mn contribute to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and promote the breakdown of molecules such as formaldehyde (HCHO) at room temperature.[ 71 ] This makes them potential for reducing indoor living hazards including germs and HCHO pollution.[ 72 ] Silica nanoparticles (SiO2‐NPs) are widely utilized in coatings due to their abundance, low cost, transparency, and ease of surface modification. They play an important role in surface corrosion resistance, anti‐freezing, anti‐frosting, anti‐icing, anti‐adhesion, and self‐cleaning coating applications.[ 73 ]

4. Action Modes of Nanoparticles in Textiles

Textile materials containing nanoparticles have demonstrated enhanced water repellence, UV blocking, antimicrobial qualities, wrinkle‐free nature, antistatic nature, soil resistance, flame retardance, electrical conductivity, self‐cleaning properties, and so on.

This section discusses the mechanisms by which NPs can improve the characteristics of textile substrates.

4.1. Antibacterial/Antiviral Activities

Biocides such as QACs, triclosan, PHMB, and chitosan (Cs) are extensively used as antimicrobial agents in commercial textiles, and function in a variety of ways depending on their chemical and structural properties.[ 28 ] The primary modes of action against microbes are: i) cell wall damage; ii) cell membrane functions inhibition resulting in vital solutes leakage; iii) protein synthesis suppression preventing growth and reproduction; iv) nucleic acid synthesis inhibition (RNA and DNA); and v) impairment of other metabolic activities.[ 28 , 74 ] (Figure 2 )

Figure 2.

Action mode against microorganisms. Reproduced from.[ 74 ] Copyright (2023), MDPI.

Recent discoveries on the harmful effects of these chemicals on the environment and human health are prompting a reconsideration of the benefits and dangers associated with QACs,[ 75 ] triclosan,[ 76 ] PHMB[ 77 ] across their manufacturing, usage, and disposal life cycles.

NPs such as silver (Ag),[ 78 ] copper oxide (CuO),[ 79 ] zinc oxide (ZnO),[ 80 ] and titanium dioxide (TiO2),[ 81 ] have been introduced to impart antibacterial or antiviral properties to textiles. The antimicrobial properties of NPs were primarily due to adhesion and penetration into microbial cells, as well as the induction of oxidative stress via ROS generation, which led to cell death. They consisted of destroying viral and cellular components, the DNA or RNA, and the protein envelope of microbes, as well as preventing the microbe from reproducing itself.[ 74 , 82 , 83 ]

4.2. UV Blocking

UV absorbers, radical interceptors (Hals), and NPs are common UV stabilizers used in coating formulations to protect the substrate from the damaging effects of UV light. UV stabilizers provide UV protection through various processes. Organic UV absorbers convert UV light into heat and higher wavelengths, while Hals capture free radicals and prevent polymeric decomposition from continuing. Organic UV absorbers appear to be more effective than inorganic NPs, however their durability is limited due to evaporation and migration away from the surface.[ 63 ]

Semiconductor oxides or metal nanostructures such as TiO2, ZnO,[ 84 ] combination of Ag and TiO2 or ZnO,[ 85 ] magnesium oxide (MgO),[ 86 ] ceria (CeO2) and zirconia (ZrO2),[ 87 ] are extensively utilized as the inorganic UV‐blocking agents during textile production. These inorganic particles can either reflect, absorb, or scatter the light.

The process of UV absorption entails the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band by photon energy.[ 64 ] Light with energy below a material's bandgap is absorbed because it can excite electrons. Light with a wavelength larger than the bandgap wavelength, on the other hand, is not absorbed. Usually, the absorbed light is transformed into heat, which is insignificant at ambient temperature.[ 64 ] The absorption of UV radiation by metal oxides (MO) leads to the generation of hydroxyl and superoxide radicals via the following mechanisms.[ 15 , 88 ] Under UV irradiation (hν), electrons (e−) in metal oxides migrate from the valence band to the conduction band, resulting in a hole (h+) (Equation 1). This hole can react with water to create hydroxyl radicals (OH•) (Equation 2), while electrons can react with oxygen (O2) to produce superoxide radicals () (Equation 3) and hydroxyl radicals (OH•) (Equations (4), (5), (6), (7)). The hydroxyl radical can decompose the organic components or polymers (R) in carbon dioxide and water ( (Equation 8).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

4.3. Flame Retardancy

Textile materials undergo heat deterioration prior to being burned in presence of flame and oxygen. Part of the degraded species are transformed into flammable volatile chemicals that, when mixed with oxygen, ignite the flame. If the generated heat is sufficient, it can easily be transferred to the textile substrate, causing further degradation and promoting a self‐sustaining combustion cycle.[ 89 ] (Figure 3 )

Figure 3.

Combustion of textiles in presence of ignition source and self‐sustaining combustion cycle. Reproduced from[ 90 ] with the permission of Elsevier Ltd. Copyright 2020.

Flame retardant mechanisms are divided in condensing phase and gas phase. In the condensing phase, reactions such as dehydration, condensation, crosslinking, and cyclization might occur between the additives and the carbonaceous layer on the textile surface. These processes help to generate dense carbon layers on the fabric's surface, which slow pyrolysis and prevent the release of further gases, lowering flammable gas generation and degradation rate.[ 91 ]

Thermal degradation of textiles can generate free radicals (H•, OH•), which can fuel additional burning. In gas phase, some flame retardants are able to react with these free radicals, reducing their concentration and interrupting the chain reaction of combustion.[ 91 ]

The application of synthetic chemicals based on nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulphur was commonly taken into consideration to enhance the flame retardant and thermal characteristics in textiles.[ 90 ] Traditional methods included adding halogen and/or phosphorus‐containing co‐monomers to the polymer structure during copolymerization (chemical reaction modification) or combining polymer and flame retardants in an extruder during melt spinning. Yet, coating methods containing flame retardant components, such as impregnation process,[ 92 , 93 ] sol‐gel method,[ 94 ] plasma,[ 95 ] layer‐by‐layer assembly methods[ 96 , 97 , 98 ] have been also experimented.

Phosphorus additive can function in the gas phase by creating phosphorus radicals that trap highly reactive radicals; yet, in the condensed phase, phosphorus promotes char formation.[ 4 ]

Organobromine‐based species have been the most extensively utilized flame retardants, following aluminum trihydrate. However, all the halogenated retardants were assessed for potential toxicological and environmental effects due to the production of dioxin, formaldehyde, and other hazardous compounds during the combustion of polymers containing these flame retardants.[ 29 , 97 ] Environmental concerns prompted the replacement of these chemicals with phosphorus‐ and/or nitrogen‐containing alternatives even if possible issues may have developed for selected organophosphorus‐based retardants.[ 29 ] Recently, bio‐based components like Cs[ 98 ] and phytic acid (PA)[ 96 , 97 ] also in combination,[ 99 ] alginate,[ 92 ] tannic acid (TA) and vinyl trimethoxysilane,[ 94 ] have gained popularity as flame retardants due to their environmental benefits.[ 90 , 100 ] These bio‐based components were also combined with inorganic materials like TiO2, ZnO, SiO2,[ 95 ] and Ag.[ 101 ]

Inorganic particles can promote char formation and produce separate layers that keep heat, oxygen, and active free groups out of the polymer matrix, preventing further oxidation.[ 102 , 103 ]

Adding inorganic nanoparticles to an intumescent system such as PA/SiO2,[ 104 ] polyethyleneimine (PEI) wrapped SiO2 and polyphosphoric acid (PPA)[ 103 ] or PA[ 105 ] for cotton or wool, graphite carbon nitride (GCN) and phosphorylated chitosan (PCs)[ 106 ] for cotton, TiO2 and SiO2 and naturally derived PA and Cs components for polyamide 6,6,[ 107 ] resulted in a hybrid organic–inorganic intumescent coating. The inorganic part can produce a thermal shielding effect, promoting the formation of char layers, and constructing a denser framework of bonds that hinders the transfer of heat, oxygen, and fuel. The organic part can produce expanded carbonaceous char or non‐flammable gases, diluting the concentration of oxygen and combustible gas, or capturing free radicals. The combination of these factors greatly increases the matrix's flame retardant properties.[ 89 , 103 , 108 ]

4.4. Water Repellency

Due to their porous, flexible, breathable, and hydrophilic properties, common textiles—especially natural ones—absorb easily liquids like water and oil. Researchers are focusing on changing textile wettability, which is a desired feature in creating self‐cleaning capabilities, waterproofness, water/oil/stain repellency, and high‐performance applications.[ 109 ]

Changing textile surfaces from hydrophilic to hydrophobic prevents droplets that fall on the surface from spreading and penetrating fibers, allowing liquids to form beads and move away.[ 109 ]

Several methods were explored to achieve super‐hydrophobicity in textile fabrics, including dip coating, sol‐gel processes, spray coating, spin coating, deposition, electrospinning, and chemical vapor deposition.[ 110 ]

Commonly, textile finishing utilizes durable water repellent (DWR) impregnation, which provides water, oil, and stain resistance depending on the used chemicals.[ 30 ] Polymeric per‐ and poly‐fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “side‐chain fluorinated polymers,” have been used in DWR chemistries for decades due to their durability and resistance to water and oil. To address concerns about the negative impact on human health and the environment of long‐chain PFAS (n° carbon atom in chain greater than 7), attempts have been made to replace them with short‐chain (n° carbon atom in the chain from 4 to 7) or non‐fluorinated alternatives.[ 30 ] However, concerns about short‐chained chemicals are emerging due to evidence in persistence and toxicity.[ 111 ] Long and short chains PFAS are stable in the environment and can undergo to microbial degradation, bioaccumulation and biomagnification in the food chain.[ 112 ]

To attain hydrophobicity and a water contact angle (WCA) greater than 90°, the surface needed a specific combination of roughness and low surface energy.[ 109 , 110 ] (Figure 4 )

Figure 4.

a) Good surface wetting with WCA< 90°; b) Poor surface wetting with WCA >90° and hierarchical structures on textile surface with micro/nano roughness and hydrophobic polymer; c) Self‐cleaning effect caused by the sliding of the drop on the textile surface catching dirt particles deposited on the hierarchical structures.

The primary source of inspiration for creating hydrophobic surfaces has been the “lotus effect,” sometimes referred to as the superhydrophobicity (WCA > 150°) of lotus leaves, as well as other natural structures like butterfly wings, geckos, rose petals, and water strider legs.[ 113 ]

Deposition of particles of varied sizes, such as SiO2,[ 114 , 115 ] ZnO,[ 116 ] TiO2 [ 117 ] was utilized to offer rough surface to textiles with an emulated lotus‐leaf‐like hierarchical protrusion structure, and an hydrophobic polymer such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)[ 118 ] to lower the surface energy[ 114 ] and/or to act as binder.[ 115 , 117 ]

However, superhydrophobic textiles were susceptible to external deterioration, such as abrasion and washing conditions. Enhancing the mechanical stability and durability of hierarchical micro‐ and nanoscale surfaces on textiles is still a challenge.

Recently, surfaces were structured at three length scales to achieve a durable superhydrophobic covering of textiles. The immersion of cotton‐based substrate in a solution containing ZnO particles with average sizes of 90, 200, and 500 nm, followed by PDMS hydrophobic treatment, resulted in a long‐lasting hierarchical structure on nonwoven fabrics. Excellent superhydrophobic performance with WCA 163.9° was recorded, which remained ≈150° even after 80 friction tests with abrasive paper. After 24 h of immersion in organic solvents and strong acid/alkali solutions, the superhydrophobic properties were unchanged.[ 119 ]

5. Textile Finishing Methods and Greener Technologies

This section describes the main wet finishing methods for fabrics containing NPs, with a focus on aspects that improved technology efficiency and contributed to sustainable development.

5.1. Wet Finishing Treatments

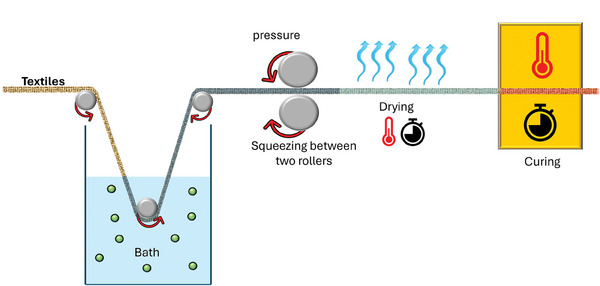

Pad‐dry‐cure is the most common wet finishing technology for natural and synthetic textiles. In this process, fabric is soaked in solution with specific component concentrations (i.e., binders, softeners, stabilizing agents, catalysts, NPs, crosslinkers, etc.), then squeezed to achieve a desired level of wet pick‐up while passing through two horizontally placed rollers under constant pressure. The product is dried and cured at precise temperature and duration (Figure 5 ).

Figure 5.

Schematization of pad‐dry‐cure technique.

Three different polymeric binders (polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyurethane (PU), and butyl acrylic (BA)) were used to apply ZnO‐NPs on cotton fabric trough the pad dry curing process to impart antimicrobial properties.[ 120 ] ZnO‐NPs, hydrophilic and hydrophobic SiO2‐NPs, and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) were combined into a waterborne polyurethane dispersion (WPU) and impregnated into polyester‐ (PET) or polypropylene (PP)‐based textiles to increase the mechanical properties and durability of the final products.[ 58 , 121 ] TiO2 and SiO2‐NPs of varying sizes were employed in conjunction with a hydrophilic nonreactive alkyl polyester resin to increase the concentration of hydroxyl groups on the surface of PET fabric and impart long‐lasting hydrophilicity.[ 122 ] Acrylic binder was used to immobilized MgO‐NPs to impart antibacterial activity to cotton fabric,[ 123 ] or to immobilized tin oxide (SnO2), TiO2 and SnO2‐TiO2 mix NPs to self‐cleaning activity and less stain pickup (coffee stain).[ 124 ]

Pad‐dry‐cure is a wet treatment solution that is more versatile for industrial‐scale applications, but it has several significant limitations in terms of human health and the environment, such as consuming energy and massive amounts of water, releasing polluting emissions into the atmosphere and through effluents[ 125 , 126 ] The wet pickup (weight of wet samples relative to starting ones) is more than 70%, necessitating water evaporation and energy‐intensive drying technique. Furthermore, as finishing products evaporate, they travel across the textile surface, resulting in non‐uniform treatment.[ 16 ]

Adding crosslinking agents to formulations reduced finishing agent migration on coated surfaces and increased treatment durability.[ 63 ] To avoid synthetic cross‐linkers, which can be harmful and impede biodegradation, a green crosslinker based on citrate moieties (citric acid) was employed to adhere Ag‐NPs[ 127 ] or β‐cyclodextrin and ZnO‐NPs[ 128 ] to cellulosic fabric via the pad‐dry‐cure method. The use of natural curcumin dye and silver nano‐finishing on cellulose fabric resulted in excellent dyeing performance, hydrophobic behavior, and broad‐spectrum antibacterial properties.[ 129 ] However, curcumin/TiO2 treated fabric utilizing as a crosslinker 3‐Chloro‐2‐hydroxypropyl trimethyl ammonium chloride displayed the best antibacterial activity compared to citric acid.[ 130 ]

5.2. Advanced Technologies to Textile Treatment

5.2.1. Sonoprocesses

Sonoprocesses are explored as methods to improve conventional dyeing and finishing procedures.[ 131 , 132 ] High‐frequency sound waves (20KHz to 10 MHz) in a liquid medium cause cavitation bubbles, which create high‐velocity micro‐jets of water that effectively remove contaminants and enhance fabric absorbency.[ 51 , 131 ] Sonication‐assisted cavitation removes dirt and other impurities from the fiber's surface, avoids dye molecule aggregation, and significantly speeds up the mass transfer of chemicals and dyes from the treatment solution to the fiber's surface.[ 133 ] It accelerates the rate at which chemicals react with textile fibers while consuming less energy and processing time, and facilitates eco‐friendly synthesis and application of nano‐based finishes to textiles.[ 51 ] Ultrasounds do not destroy enzymes, but rather boost their response rate by distributing them evenly throughout the surface. Ultrasounds can eliminate dye aggregation, enabling for dyeing with extremely low liquor ratios. However, there are no evidences of energy, water, chemical savings and cost‐benefits from applying ultrasounds for industrial‐scale processing to force textile producers to employ sonicated procedures.[ 133 ]

5.2.2. Plasma Treatment

Plasma represents a green way for altering the outer atomic layer without affecting the material's bulk qualities.[ 134 ] Using plasma in textile finishing can save the ecosystem as it eliminates the need for water or drying, requires few chemicals, and produces no downstream pollution.[ 125 , 134 ] Plasma is a high concentration of reactive species, such as electrons, ions, neutrons, radicals, and photons, produced by high energy sources like heating or electromagnetic fields.[ 135 ] Different gases such as air, CO2, NH3, N2 and He can be used to modify the textile surface, and appropriate plasma parameters (such as pressure, energy, time, and gas flow rate) can be established to cause radical generation, etching, chain scission, and polymer deposition. These phenomena enhance the wettability, chemical reactivity, and adhesion. Plasma treatment was used to activate the fibrous surfaces and stimulate the formation of polar groups such as carbonyl, alcohol, ether, ester, and hydroxyl substituents allowing for better attachment to nano‐scaled particles, promoting polymer or species grafting onto the substrate (Figure 6 ). Following plasma pre‐treatment, the NPs were fixed on the surface of the fibers, resulting in a variety of coatings that were tightly attached to diverse textile substrates.[ 16 , 134 , 136 ]

Figure 6.

Schematization of plasma treatment in textile finishing.

Plasma may be a cost‐effective process over time, but the initial setup demands significant expensive alterations to existing systems. This prevented industries from embracing this technology.[ 16 ]

5.2.3. Sol‐Gel Methods

Sol‐gel technology combines chemical and physical processes such as hydrolysis, polymerization, gelation, condensation, drying, and densification.[ 137 , 138 ] Large macromolecules, molecular aggregates, or small particles in a solution (sols) aggregate and, under controlled conditions, connect to create a gel. The gel is a solid phase in a network that captures and immobilizes the liquid phase. Following the sol‐gel transition, the solvent phase is extracted from the interconnected structures.[ 138 , 139 ] The sol‐gel method's versatility stems from the ability to mix beginning chemicals (precursors) in a solution at a lower temperature, allowing for precise control over diverse components at the atomic level. This approach relies on surfactants, solvents, reaction time, and temperature to achieve high‐performing structures.[ 137 , 138 ] Sol‐gel coatings are more environmentally friendly than standard finishing procedures due to reduced chemicals consumption, low temperatures, and fast synthesis periods.

This technology has been proposed as an ecologically friendly method to synthesize nanomaterials with diverse morphologies.[ 47 , 140 ] The deposition of sol‐gel solutions on porous surfaces such as textiles (linen,[ 141 ] cotton,[ 142 , 143 ] jute‐cotton,[ 144 ] PET[ 145 ]) can be accomplished through padding,[ 141 , 144 ] immersion,[ 142 , 143 ] dip coating,[ 146 ] and spray coating.[ 145 , 147 ] Thermal curing is usually done at temperatures below 130 °C in an oven.[ 147 ]

However, harmful organic solvents were often used in sol‐gel methods, particularly in large‐scale industrial processes, generating emissions and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Currently, scientific attention is being placed on water‐based dispersions.[ 140 ]

5.2.4. Layer‐by‐Layer (LbL) Self‐Assembly

Conventional Layer‐by‐Layer (LbL) self‐assembly involves the gradual adsorption of complementary chemicals onto a substrate surface. Positive and negative species are alternatively placed to textiles through the spontaneous deposition of oppositely charged ions (Figure 7 ).

Figure 7.

Schematization of Layer‐by‐Layer (LbL) self‐assembly method in textile finishing.

LbL self‐assembly is regarded a green and low‐cost technology that can be employed in wet‐finishing procedures to reduce chemicals, water, and energy consumption while increasing fabric functionality.[ 148 ] Dyeing and functional finishing can be combined in a single procedure, which can be implemented with minor adjustments to existing padding machines.[ 149 ] Several deposition processes, including dip‐coating, spraying, and perfusion, are suitable to produce multilayers by electrostatic and non‐electrostatic mechanisms.[ 150 ]

6. Progresses in Wet Finishing Methods Involving Nanoparticles

This section highlights green progresses in traditional wet finishing techniques that involve the combination of two or more sustainable technologies for the synthesis and application of NPs to textiles. Nanoparticles can be incorporated into fabrics using two main techniques via: i) ex situ synthesis, where the production and fabric impregnation of NPs occur in two steps; ii) and in situ synthesis, where the production and fabric impregnation of NPs take place simultaneously.[ 32 ] In situ synthesis of NPs was considered more efficient, cost‐effective and environmentally friendly than ex situ methods. It needed less time and water consumption to impregnate fabrics,[ 32 ] reduced the NPs agglomeration,[ 151 ] and increased NPs entry the fabric structure.[ 152 ] Ex situ synthesis, on the other hand, has remained a common technique for incorporating NPs into textiles.

Recent research activities involving NPs in textile finishing, methods for synthesis and applications of NPs (in situ and ex situ), substrates, and main properties have been summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Main components in wet finishing including NPs, synthesis methods and application technologies, and the main properties of final fabrics.

| Main Components | NPs synthesis and precursors | Finishing technologies | Textile substrate | Interactions | Main properties of final textiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ex situ synthesis‐based methods | |||||

| Ag/TiO2‐NPs[ 136 ] | Titanium isopropoxide (TTIP) in sol‐gel. Mixing with oxalic acid and AgNO3 | Plasma pre‐treatment/pad‐dry‐cure | Viscose | Electrostatic forces among Ti4+ existing on TiO2 or Ag/TiO2, and the negative charges on the viscose | Antibacterial properties against E. coli by measuring optical density at 620 nm vs time |

|

Water‐dispersible MnO2‐NPs[ 71 ] |

KMnO4 as precursor; micelles of cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as template; 2‐(Nmorpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) as reducing agent | Impregnation | Cotton | Electrostatic forces: electropositive CTAB templates bridged gaps among negatively charged MnO2 and textiles | Antibacterial activity over than 99% |

| (SiO2‐ZnO)‐NPs and compatibilizers, i.e., PDMS and n‐octyltriethoxysilane (OTES)[ 153 ] | TEOS in sol‐gel. Chemical precipitation using Zn(OAc)2 as precursor | Ultrasounds/ dip‐coating in PDMS, OTES and NPs/curing | Cotton | Physical interactions between NPs and compatibilizers | UPF >384 and WCA>148° remained stable after 40 h exposure to 370 nm, or 3 accelerated laundering cycles |

| (Zn‐TiO2)‐NPs and silane coupling agent (γ‐glycidoxy propyl trimethoxy silane‐GPTS)[ 154 ] | TTIP in sol‐gel. Addition of zinc nitrate nonahydrate in solution | Ultrasonication/Pad‐dry‐cure | Cotton | Chemical interactions: GPTS attached to the NPs, and bonded to cotton | 98% reduction in bacterial activity that was reduced to 96% after 10 washes |

| (Cs‐ZnO)‐NPs and (Cs‐TiO2)‐NPs and (3‐Glycidyloxypropyl trimethoxysilane‐ GPTMS)[ 161 ] |

Ex situ and in situ Chemical precipitation method to produce ZnO‐NPs, then dissolved in Cs solution, also in combination with commercial TiO2 Or sol‐gel method |

Ultrasonication/pad‐dry‐curing | Cotton | Chemical bonding: GPTMS bonded cotton and reacted with Cs | Enhanced stability of the coating against washing by sol‐gel technique. UPF ≈50, reduced to 40 after 10 washing cycles. Antibacterial activity of 100% reduced to ≈90% after washing. |

| In situ synthesis‐based methods | |||||

| Ag‐NPs[ 155 ] | Thermal reduction of silver carbamate complex | Plasma pre‐treatment/ Pad dry cure with silver carbamate solution | Cotton | Negative substituents on fabric due to plasma produce electrostatic attraction with the Ag+ | UPF = 2396 |

| Ag‐NPs, EGDE (ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether as crosslinker) and natural madder dye[ 156 ] | Heating of dyeing solution of madder dye, EGDE, AgNO3 | Immersion in a solution of EDGE, madder dye and AgNO3 | Cotton | EGDE reacted with cotton and dye playing a bridge role between the dye and the cellulose |

UPF = 50+ Antibacterial activity of 97%–98% depending on microorganisms after 40 washing cycles |

| (Ag‐TiO2)‐NPs and TMTP (phosphorus‐based flame‐retardant)[ 143 ] | TTIP in sol‐gel | Immersion in TTIP and TMTP/drying/ hydrothermal treatment in AgNO3 | Cotton | Self‐crosslinking of TPMP; crosslinking of TPMP and TiO2; hydrogen bonding between TPMP/TiO2 and cotton | UPF = 40; bactericidal activity >95% against E. coli and 100% reduction in S. aureus; after glow time of 3.4 s |

| Cu‐NPs and GO/TA and 1‐octadecanethiol (hybrophobic agent)[ 158 ] | Copper acetate monohydrate was ultrasonically dissolved in water to generate Cu2+ solution | Ultrasonication /LbL self‐assembly/hydrophobic treatment | PET | Electrostatic interactions between polyanion electrolyte GO/TA and polycationic electrolyte (Cu2+) |

UPF = 200; WCA>150°, 99% antibacterial efficiency even after 20 washing cycles or 30 rubbing cycles |

|

SiO2‐NPs and citric acid as crosslinker[ 147 ] |

TEOS precursor in sol‐gel method | Spray coating/drying | Cotton | Citric acid can form bond with the cotton. and hydrogen bonds with SiO2 | WCA>150° |

| PDMS‐SiO2 hybrid and ammonium polyphosphate (APP) (micro‐nano structured coating)[ 142 ] | TEOS precursor in sol‐gel method | Plasma pre‐treatment/immersion/drying | Cotton | APP attached on the cotton fibers via the hydrogen bonding interactions; reactions of TEOS and HPDMS to generate PDMS/silica; Si‐O‐C formed between PDMS‐silica and cellulose |

WCA>160° PHRR = 86W/g |

| ZnO‐NPs and 4‐aminobenzoic acid ligand (PARA)[ 159 ] | Zinc chloride in aqueous solution under ultrasonication and addition of NaOH | Immersion with ultrasonication | Cotton | PABA reacted with oxidized fabric and acted as a monodentate ligand for the NPs formation | UPF enhancement compared to basic fabric of 62% and 93%–95% antibacterial efficiency after 20 washing cycles and 100 abrasion cycles |

| Organic NPs | |||||

| Carnauba Wax NPs (CWNs) and Cs[ 160 ] | CWNs synthesized in solvent‐free emulsion and melt‐dispersion techniques | Aminiziation process to impart the cationic character to cotton/immersion in HCl/LbLself‐assembly | Cotton, cotton/nylon6, and nylon6 | Electrostatic interactions between negative charges of CWNs and chitosan as a positive charge component | Highest WCA of 135 °C for cotton/nylon6 and 125° after washing; antibacterial activity of 95%–97% |

| CWNs and ZnO‐NPs[ 162 ] | CWNs synthesized in solvent‐free emulsion and melt‐dispersion techniques | Plasma pre‐treatment/layer‐by‐layer self‐assembly | Cotton, cotton/nylon6, and nylon6 | Electrostatic interactions between negatively charged CWNs and positively charged ZnO‐NPs. Plasma pre‐treatment to generate negative charges on textile | ≈100% antibacterial activity; WCA>130° |

| (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs[ 163 ] | Ionotropic gelation process to produce Cs‐NPs, then added to an aqueous solution of AgNO3 | Cationization/ LbL of Poly(styrenesulfonate)/Poly(allylhydrochloride) (PSS/PAH) / LbL self‐assembly in PSS solution and (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs suspension | PSS/PAH coated Cotton | Electrostatic interactions: fabric cationization; BASE LAYER: PSS polyanion and PAH polycation; BODY LAYERS: PSS polyanion and (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs polycation | ZOI = 2.5–5 mm depending on microorganisms (ZOI = 0 for treated fabric with Cs‐NPs) |

| Chitosan nanofiber (CNF)/nano‑silver phosphate (Ag3PO4)[ 164 ] | Commercial chitosan nanofiber (CNF) aqueous gel, chemical precipitation method to Ag3PO4 ‐NPs | Ultrasonication/ fabric immersion/drying | Cotton | The porous and nano‐fibrous structure of CNFs provided an ideal substrate to which nanoparticles tightly adhered | Enhancement of the water absorption of 118%, largest ZOI of 22 mm for the treated fabrics. |

(*UPF: Ultraviolet Protection Factor; ZOI: Zone Of Inhibition; WCA: Water Contact Angle; PHRR: Peak Heat Release Rate)

6.1. Ex Situ Synthesis

Silver on titanium nanoparticles (Ag/TiO2‐NPs) were created to combine the beneficial effects of both Ag and TiO2‐NPs while reducing their shortcomings. Silver is an expensive metal, and small quantities are inefficient for a wide range of realistic items. TiO2‐NPs are only activated by UV irradiation and have limited photocatalytic activity in the visible or sunlight. Ag/TiO2‐NPs were synthesized in two stages utilizing low‐temperature sol‐gel method (to produce TiO2) followed by UV irradiation (to deposit Ag onto the TiO2 surface). Then, Ag/TiO2 complex was deposited onto plasma‐pretreated viscose fibers using the simple pad‐dry‐cure technique. The binding stability of NPs onto viscose was related to the electrostatic forces among Ti4+ present on TiO2 or Ag/TiO2 and the negative charges (O‐O− and ‐COO−) created by plasma pretreatment. The textile treatment was deemed efficient in imparting antibacterial, self‐cleaning, and photo‐induced catalytic properties.[ 136 ]

Two step synthesis via sol‐gel dip‐coating was used to create two distinct NPs architectures of SiO2 and SiO2‐ZnO, resulting in hydrophobic cotton textiles. SiO2‐NPs were synthesized using the Stöber method (hydrolysis and condensation) with TEOS as a precursor, whereas SiO2‐ZnO were prepared using the double precipitation approach with TEA precipitating agent and zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn(OAc)2) precursor in silica‐ethanol. The substrates (woven, bleached, pre‐washed cotton fabrics) were treated with a solution containing poly(dimethyl‐siloxane) (PDMS), n‐octyltriethoxysilane (OTES), and NPs (ultrasonically dispersion). PDMS and OTES were employed to facilitate nanoparticles grafting to substrates. These two hydrophobizing agents underwent covalent cross‐linking to the fabric surface during curing and formed a rigid network of polymer chains that stabilized NPs onto the woven cotton substrates. The cotton fabric was dip‐coated in the mixture for 20 min, then dried, and cured at 140 °C for 1 h. Water repellent characteristics were attained with WCA greater than 148° without the use of fluorinated components.[ 153 ]

Zn‐doped TiO2‐NPs were produced by sol‐gel method and immobilized on cotton fabric with silane coupling agents utilizing pad‐dry‐cure treatment.[ 154 ] Figure 8 illustrates the mechanism of cotton functionalization. Functionalized fabric displayed efficient photocatalytic activity for self‐cleaning activity under sunlight. 90%–98% drop in dye concentration (for five commercial polluting dyes) after 3 h of reaction time in ambient sunshine was attested. The presence of NPs slightly reduced the air permeability of treated fabrics (which was not significant in terms of fabric comfort) but significantly increased the respective tensile strength.[ 154 ]

Figure 8.

Schematic of functionalized cotton fabric preparation. The silane coupling agent was hydrolyzed. The methoxy groups engage with the OH groups of NPs. On the other hand, the epoxy component reacted with the cellulose group on cotton, producing a link between the NPs and cotton. Reproduced from.[ 154 ] Copyright (2023), MDPI.

6.2. In Situ Synthesis

Thermal reduction method was used to produce Ag‐NPs from silver carbamate complex and realize a facile and inexpensive in situ pad dry cure procedure. This technique improved the reactions by lowering time, boosting rate and selectivity, and avoiding residual inorganic ions.[ 155 ] Following oxygen plasma treatment, polar groups such as ‐O‐C = O, ‐O‐O‐, C = O, C‐O, ‐COOH, or ‐COH were expected to be formed on the cotton surface, increasing hydrophilicity and making the subsequent pad‐dry‐curing procedure more successful. The cotton fabric was immersed in silver carbamate solutions, sonicated, padded, and then thermally treated at 130 °C. The thermal treatment caused a reduction of carbamate complex into Ag‐NPs.[ 155 ] Cotton functionalized with Ag‐NPs outperformed blank cotton in terms of visible light absorption, photocatalytic activity, UV blocking, and antibacterial efficacy.

In situ formation of Ag‐NPs on the surface of cotton with natural madder dye for color fastness, UV protection and antibacterial properties was proposed in.[ 156 ] The cotton was initially soaked in a crosslinked dyeing solution containing madder dye, ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether (EGDE), and AgNO3. The dyed cotton fabric was cured at 130 °C for three minutes. The dyed fabrics had a UV protection factor (UPF) of 50+, excellent dyeing effects with high color fastness, acceptable rubbing and washing fastness, and an excellent inhibitory effect on Gram‐negative bacteria (E. coli) and Gram‐positive bacteria (S. aureus).

Superhydrophobic textile surfaces were created by coating with a TEOS‐based solution using a sol‐gel method.[ 147 ] TEOS/ethanol solution was applied to the cotton/polyester (90%/10%)‐based fabric by spray method. This approach included three main reactions[ 147 , 157 ]: i) the hydrolysis of a precursor silica source, like tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS, ) (Equation 9); ii) the alcohol condensation (such as ethanol, ) (Equation 10); iii) the water condensation (Equation 11)

| (9) |

| (10) |

| (11) |

Acid citric was used as crosslinker agent to adhere the NPs to textile substrate. Carboxylic acid (COOH) groups of citric acid get attached to the fabric through an esterification bond. The same groups could form bonds with the hydroxyl groups present on the SiO2 surface (ester and/or hydrogen bonds). This resulted in a 3D sol‐gel coating network with improved hydrophobicity (WCA> 150°) that was reduced after 20 washing cycles.

A one‐pot technique was proposed to create a micro‐nanostructured coating on cotton fibers in.[ 142 ] Oxygen plasma activated the fabric, increasing the presence of oxygen‐containing groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carboxyl) on its surface. Then, the sample was immersed in a suspension of ammonium polyphosphate (APP), tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), and hydroxyl‐terminated polydimethylsiloxane (HPDMS). APP particles were joined to cotton fibers via hydrogen bonding. Ammonia was added to catalyze the hydrolysis and condensation of HPDMS and TEOS, resulting in the progressive formation of polydimethylsiloxane‐silica hybrid on cotton fibers. This method resulted in superhydrophobic products with a contact angle of 160° endowed with an outstanding flame retardancy (Figure 9 ).

Figure 9.

A one‐step process that combines plasma activation of cotton fabric with a sol‐gel coating of PDMS‐silica to provide superhydrophobicity and exceptional flame retardancy. Reproduced from[ 142 ] with permission of Elsevier Inc. Copyright (2019).

Superhydrophobic polyethylene terephthalate (PET) fabric with enhanced antibacterial activity was created using in situ growth of Cu‐NPs. Copper acetate monohydrate was ultrasonically dissolved in water, resulting in a polycationic electrolyte (Cu2+ solution). TA and graphene oxide (GO) were ultrasonically combined to generate a polyanionic electrolyte (TA/GO solution).[ 158 ] The PET fabric was fully soaked in the GO/TA solution, then rinsed, and dried. Next, the PET fabric was soaked in the Cu2+ solution, washed, and dried. To achieve layers assembly, the PET textiles were immersed alternatively in two separate solutions. The treated textiles were then immersed in a solution of 1‐octadecanethiol (hydrophobic treatment). The coated PET fabric demonstrated superhydrophobic properties with a WCA greater than 150°, excellent self‐cleaning, and water‐proofing properties, and 99% antibacterial efficacy against E. coli and S. aureus. The obtained characteristics were retained after several washing and rubbing cycles.[ 158 ]

Organic linkers that operate as chelating or bridging agents were proposed as a potential method to produce a lasting finishing treatment in.[ 159 ] Innovative in situ synthesis technology using ultrasound irradiations to synthesize and apply NPs to textiles in a one‐step process was experimented in.[ 159 ] Cotton fabric was oxidized with periodate to produce aldehyde groups on its surface. The fabric was subsequently treated with 4‐aminobenzoic acid ligand (PABA). This resulted in a chemical interaction between PABA's amino groups and the oxidized fabric's aldehyde groups. The textiles were immersed in an aqueous solution of zinc chloride (ZnCl2) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH), resulting in ZnO‐NPs synthesis. The presence of carboxyl‐group (due to PABA) on fabric surface allowed the adsorption of Zn+2, providing sites for the nucleation and growth of ZnO‐NPs. All of these stages were accompanied by ultrasonication. Textile products demonstrated significant UV protection and antibacterial efficiency, which remained unchanged after washing (n° 20 cycles) and abrasion (n° 100 cycles).[ 159 ]

A sol‐gel/hydrothermal treatment was used to apply a phosphorus‐based flame‐retardant, 3‐(trihydroxysilyl)propyl methylphosphonate (TPMP, C4H13O6PSi), together with Ag‐doped TiO2 to cotton fiber surfaces (Figure 10 ).[ 143 ] Doping the TiO2 lattice with a little amount of Ag can increase the formation of ROS and decrease charge recombination rate. Cotton was fully immersed in two different sols, made from titanium isopropoxide (TTIP, C₁₂H₂₈O₄Ti) alone or in combination with TPMP. Then, samples were wrung on a two‐roller padder and hydrothermally treated in a water solution containing AgNO3 for in situ synthesis of Ag‐doped TiO2. Self‐crosslinking of TPMP via Si‐O‐Si bonding and crosslinking of TPMP and TiO2‐doped Ag‐NPs via Si‐O‐Ti were hypothesized. The combined actions of the components resulted in UVA and UVB protection with a protection factor (UPF) of 50+, self‐sterilization against germs like Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, improved thermal stability and flame retardancy.

Figure 10.

Proposed schematic of the functionalized surface of cotton. Reproduced from[ 143 ] with permission of Elsevier. Copyrigth (2023).

6.3. Organic Nanoparticles in Textile Finishing

Nature provides a plethora of polysaccharides and lipides that can be used as an eco‐friendly finishing agent to create functional textile materials due to their exceptional biocompatibility, biodegradability, ecological safety, non‐toxicity, potential antibacterial activity, and/or water repellency effects.

Brazilian palm tree leaves produce wax for protection. After drying and heating the leaves, the wax can be collected. Carnauba wax is a natural product, insoluble in water, highly durable, waterproof and wear resistant. Carnauba wax nanoparticles (CWNs) can be produced by solvent‐free emulsion and melt‐dispersion techniques. A LbL self‐assembly approach was used to apply a natural water repellent nano‐coating to diverse fabrics (nylon, cotton, nylon/cotton) as a green alternative to C8 fluorochemicals. The NPs (cubic and 290 nm in size) were synthesized from carnauba wax. These NPs were charged negatively as confirmed by the zeta potential test. Chitosan was employed as positively charged component to form the second layer. The textile treatment resulted in a WCA of up to 130° and a good antibacterial effect against E.coli and S.aureus bacteria, but had a detrimental impact on air permeability and fabric handle.[ 160 ]

Recently, biopolymers have been treated with metal and metal oxide NPs to create new functional materials. Researchers have extensively studied the use of inorganic solids and biopolymers such proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids to create nano‐sized textile finishes.[ 161 ]

Cotton, cotton/nylon6, and nylon6 fabrics were treated with Carnauba wax NPs (CWNs) and zinc oxide (ZnO) NPs to provide water resistance and antibacterial qualities.[ 162 ] Carnauba wax, which had a negative charge, attracted ZnO‐NPs that had a positive charge. This resulted in multilayers on the fabric surface (LbL technique), which greatly increased the WCA up to 130° while also providing a 100% antibacterial effect.[ 162 ]

Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PSS) and silver loaded chitosan nanoparticles ((Cs‐Ag)‐NPs) were employed as anionic and cationic agents in LbL assembly for cotton fabric coating. Chitosan solution was prepared by dissolving pure chitosan powder in acetic acid and diluting with water. Sodium tripolyphosphate in deionized water was added dropwise to the chitosan solution and magnetically swirled to realize Cs‐NPs. An aqueous solution of AgNO3 was added to the Cs‐NPs suspension. Silver ions (Ag+) became attached to the Cs‐NPs and (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs were created. Cationisation was used to generate cationic sites on the fabric surface. Then, the fabric was alternately dipped in PSS solution and Cs‐Ag‐NPs suspension to realize LbL coating. The presence of (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs increased fabric antibacterial activity with small silver loading, compared to chitosan‐based coating, without sacrificing air permeability, tensile strength, and flexural stiffness.[ 163 ] Further research findings on inorganic‐organic hybrid nano‐finishing are listed in Table 1.

7. Green‐Synthesized Nanoparticles for Textile Finishing

Promoting green manufacturing methods, such as green NPs synthesis, can help meet eco‐friendliness criteria by avoiding harmful chemical components. Metallic precursors, stabilizing agents, and reducing agents, ‐such as, sodium citrate, ascorbate, sodium borohydride (NaBH4), N,N‐dimethylformamide (DMF)‐, are the main components in the chemical methods to produce NPs.[ 165 ]

Prioritizing materials' biocompatibility and environmental impact during synthesis can assist ensure their eco‐friendliness.[ 166 ] Plants and microorganisms provide safe and cost‐effective alternatives to chemicals. Secondary metabolites (such as flavonoids, alkaloids, steroids, terpenoids, proteins, sugars, etc.) are abundant in plants and can be used to bioreduce (nucleate and grow), stabilize, and cap in a single step, increasing process efficiency and economy.[ 70 , 167 ] Plant parts such as seeds, leaves, stems, flowers, and heartwood, as well as microbes, and other natural resources, or utilization of microorganisms like fungi, yeasts (eukaryotes), bacteria, and actinomycetes (prokaryotes) have all been extensively explored in order to green synthesize nanoparticles.[ 70 , 168 , 169 ]

A greener strategy involved generating in situ silver nanoparticles (Ag‐NPs) on chitosan‐coated cotton using peanut waste shell extract as an eco‐friendly reducing agent was reported in.[ 170 ] Cotton fabric was soaked in a chitosan and acetic acid solution, padded, and cured at 120 °C for 5 min. After that, the sample was immersed in finishing solutions containing precursor AgNO3 and aqueous peanut shell extract. The treatment on cotton fabric significantly reduced microorganisms including Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, while also giving antioxidant properties.

Table 2 summarizes recent research on green textile finishing approaches incorporating green generated nanoparticles. The final textile properties are mostly described in terms of antibacterial activity, hydrophobicity, and UV protection.

Table 2.

Green component sources to create NPs for textile finishing.

| Nanoparticles | Green component source | NPs shape and size | Substrates | Application methods | Final textile properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag‐NPs[ 170 ] | Peanut waste shell extract as reducing agent | Predominantly spherical; average diameter of 40 nm | Chitosan coated Cotton | Immersion | Antibacterial properties of ≈90% even after 5 washing cycles |

| Ag‐NPs[ 171 ] | Aqueous extract from tea stem waste as reductant and stabilizer | Spherical; average diameter <20 nm | Silk | Impregnation | Antibacterial activity of 92% even after 20 cycles of washing and UPF = 21.28 |

| Ag‐NPs from electronic waste (PCB boards)[ 172 ] | Aqueous leaf extract of Eichhornia Crassipes as reducing agent | Rounded and spherical; size range from 39.44 to 103.8 nm | Chitosan‐coated Cotton | Pad‐dry‐cure | The recycled AgNPs from e‐waste did not exhibit good antimicrobial outcomes due to the larger particle size |

| (Cs‐Ag)‐NPs[ 173 ] | Cell free extracellular biomass of Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55 730 as reducing and capping agent | Quasi‐spherical shaped nanostructure with an average size of 40–90 nm | Cotton | Impregnation | Potential ZOI against B. subtilis after 24 h |

| Ag‐NPs and ZnO‐NPs[ 174 ] | Citrus Sinensis peel (orange peel) waste extracts as a reducing agent | For pH range of 4–10, the particle size was from 220 to 7 nm in aqueous media, and from 24 to 0.95 nm in alcoholic medium. | Cotton | Immersion | Antimicrobial activity, mosquito repellent effect, UFP≈60 reduced up to 50 after washing in alcoholic solution |

| AgCl‐ and Cu‐based NPs[ 175 ] | Punica granatum peel as a reducing and stabilizing agent | / | Chitosan‐coated Viscose | Padding and dry at ambient temperature | Antimicrobial activity of 100% |

| CuO‐NPs[ 176 ] | Carica papaya leaves as reducing agent | Square or rectangle; size <100 nm | Cotton | Dip‐coating | Greater antibacterial activity against E. coli even after 30 cycles of washing. Time to absorb one droplet of water for untreated fabric and treated fabric of 10 and 127 s |

| MnO2‐NPs[ 72 ] | Inulin from dahlia tubers; chitosan oligosaccharide; sodium alginate as reductants | Flower‐shaped multilayered structures for inulin and sodium alginate or irregular shape for chitosan. Nanosized structures with a diameter of ≈50–200 nm | Cotton | Soaking in solution | MnO2‐NPs synthesized with inulin efficiently killed bacteria in the dark, and also showed ultrafast antibacterial capability (over 99%) under irradiation. |

| TiO2‐NPs[ 177 ] | Mulberry leaves as precursor | Spherical (Anatase crystalline phase) with an average crystallite size of 28.34 nm | Cotton | Immersion | UPF of 195.68, ZOI of 7.05 ± 0.63 mm against E. coli and 9.38 ± 0.22 mm against S. aureus bacteria |

| TiO2‐NPs[ 178 ] | Bacterial cellulose from Achromobacter sp. M15 as precursor | Particle sizes ranged between 1 and 8 nm | Linen, viscose, cotton and cotton/polyester | Immersion | The order of antimicrobial activity of the treated fabrics is linen>viscose> cotton/PET> cotton |

| ZnO‐NPs[ 179 ] | Leaves of Azadirachta Indica as reducing agent | Hexagonal wurtzite, crystal size varies between 124 to 535 nm | Denim | Pad‐dry‐cure | Time for the water droplet to be partially absorbed is 90 s |

| ZnO‐NPs[ 68 ] | Plant extract of Azardirachta indica leaf, Piper betel leaf, Tridax procumbens leaf, and Aloe vera gel, used as reducing agent | Spherical and cubic; size range from 7 to 35 nm | Cotton | Pad‐dry‐cure | WCA = 156°, UPF = 63; largest zone of inhibition against E. coli of 28.76 ± 0.78 mm and S. aureus of 31.87 ± 0.73 mm c |

(*ZOI: zone of inhibition, UPF: ultraviolet protection factor, WCA: water contact angle)

8. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite the good impacts of NPs in textile finishing, there are some limitations, challenges, and critical aspects to consider.

Most research focuses on natural‐based textile materials, particularly cotton. In‐depth study should be done on synthetic fabrics that could be less hydrophilic and thus less impregnatable. A few research have been conducted on the breathability and comfort of fabrics treated with nano‐finishing. The inclusion of nano‐based finishings may stiffen the textile structure, restricting deformability and elastic properties, reducing ease of movement and adaptability to the body. The presence of nanoparticles may alter the fabric's absorbency capability, promoting or discouraging future coloring operations.

Even more important considerations may involve the toxicity of NPs to humans.

Although great progress has been made on improving adhesion to textiles, the release of NPs into the environment represents still a challenge. Their attachment to the fabric has been investigated primarily in terms of the decrease of treated fabric qualities after washing and abrasion. Then, few research has been conducted to demonstrate the resistance of textile/NPs bonding when subjected to UV‐Vis radiation. A thorough examination of the quantities of NPs discharged into water or air should be considered. NPs can enter the human body by skin penetration, inhalation, or ingestion. This can cause inflammation and long‐term consequences on the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts, as well as allergies, irritation, or damage to the body's cellular or subcellular constituents.[ 180 ]

Furthermore, given that NPs‐based textiles could remain constantly in contact with skin and human fluids, it is essential to have a thorough understanding of their roles in physiological systems. The size, shape, concentration, and aggregation of NPs have a considerable impact on cytotoxicity of nano‐finished textiles and different cell response.[ 37 ] Some studies have been conducted on chitosan‐coated viscose fabric impregnated with Ag‐ and Cu‐based NPs, which were green produced utilizing Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel extract as a reducing and stabilizing agent. The results showed that fabrics coated with AgCl‐NPs had decreased cytotoxicity toward human keratinocyte cells. Cu‐based NPs demonstrated significantly different release properties than samples impregnated with AgCl‐NPs. Over the course of the experiment, the samples emitted more Cu2+ ions.[ 175 ]

Finally, a thorough understanding of the product life cycle is essential to evaluate the risks associated with nano‐based textiles and nano‐finishing techniques. Nano‐sized finished textiles may pose a future waste issue that requires management. Alternatively, recycling and repurposing them may help to reduce production costs and environmental impacts.

Novel areas of development toward green perspectives could include the manufacturing of NPs and treated textiles from waste materials.

9. Conclusion

In this work, NPs were proposed as an eco‐friendly strategy to potentially replace chemicals frequently employed in textile finishing and impart crucial qualities in everyday life. Several literature studies demonstrated the effectiveness of NPs in entering the cell of the microorganisms, generating oxidative stress damaging cellular components, and inhibiting reproduction (antimicrobial activity). NPs provided a thermal shielding effect, promoted the production of char layers, and constructed a denser framework that inhibited the transmission of heat, oxygen, and fuel (flame retardancy). NPs worked as UV‐stabilizer additives, reflecting, absorbing, and dispersing light (UV protection). NPs and microparticles combined with hydrophobic polymers aided in the formation of hierarchical structures on textiles, resulting in a highly hydrophobic rough surface that prevented liquid droplets from penetrating substrates (water repellency).

Recent approaches toward sustainable development of wet finishing technologies have focused on enhancing adhesion to the textile substrate and durability of textile finishing during washing and abrasion cycles. This limited the release of NPs into the environment while also preserving the functions of treated fabrics.

Several agents (such as binders, cross‐linkers, silane coupling agents, and/or organic ligands) including natural‐based ones, have been introduced in the nano‐finishing formulations to improve NPs adhesion to textiles. Advanced technologies (such as plasma pre‐treatment, LbL, sol‐gel methods, irradiation of dispersions through ultrasounds) were combined to assist the pad‐dry‐cure or fabric impregnation. Plasma pre‐treatment was used to produce reactive species on textile surfaces, facilitating direct bonding with nano‐scaled particles or indirect through the agents. Ultrasounds irradiations were employed to promote homogeneous distribution of components in solutions and dispersions. Sol‐gel and LbL methods were adopted to synthesize NPs by adding precursors directly to impregnating solutions (in situ) or separately in a former phase to textile impregnation (ex situ). Using biopolymers like carnauba wax, chitosan, phytic acid, alginate, tannic acid (in the form of NPs or as coating for textiles and inorganic NPs) was proposed as a green method to enhance the biocompatibility, biodegradability, and nontoxicity of textile treatment and generate novel functional finishes. Finally, other green strategies focused on replacing traditional stabilizing or reducing agents used in NPs synthesis with natural‐based products obtained from green chemistry and plant extract or microbe species. There have been numerous examples of biomass waste, including peanut shell waste, tea steam waste, orange peel waste, of plant‐based extracts from roots, rhizomes, leaves, and gels, and of microorganisms, such as extracellular biomass of Lactobacillus reuteri, used in NPs synthesis which were then applied to cotton, linen, viscose, and silk enhancing antibacterial activities, UV protection, and WCA.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

A.P. wishes to thank the project ‘‘Avviso n. 6/2022 “per il rafforzamento del sistema di ricerca universitario in Sicilia mediante azioni di reclutamento a tempo determinato” in the framework of FSE+ Sicilia regional program 2021–27.

Open access publishing facilitated by Universita degli Studi di Catania, as part of the Wiley ‐ CRUI‐CARE agreement.

Biography

Antonella Patti is an Assistant Professor of Fundamentals of Chemical Engineering at the University of Catania. She earned her PhD degree from University of Naples “Federico II”. Her primary research interests focused on the analysis of functional and structural properties of polymers and composites, measurements of the thermodynamic and transport properties of polymeric and filled materials, fabric surface treatments, optimization of process technologies of innovative materials for sustainable development.

Patti A., Green Advances in Wet Finishing Methods and Nanoparticles for Daily Textiles. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 46, 2400636. 10.1002/marc.202400636

References

- 1. Stanes E., Textiles 2019, 17, 224. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dolez P. I., Marsha S., McQueen R. H., Textiles 2022, 2, 349. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aldalbahi A., El‐Naggar M. E., El‐Newehy M. H., Rahaman M., Hatshan M. R., Khattab T. A., Polymer 2021, 13, 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Özer M. S., Gaan S., Prog. Org. Coatings 2022, 171, 107027. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu H., Yao C., Li C., Miao M., Zhong Y., Lu Y., Liu T., Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang K., Huo Q., Zhou Y. Y., Wang H. H., Li G. P., Wang Y. W., Wang Y. Y., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 17368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woźniak D., Hardygóra M., Energies 2021, 14, 6018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patti A., Acierno D., Macromol 2023, 3, 665. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang X. C., Wang X. X., Wang C. Y., Zheng H. L., Yin M., Chen K. Z., Qiao S. L., Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 7801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russel E., Nagappan B., Karsh P., Madhu S., Devarajan Y., Suresh G., Vezhavendhan R., Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 3520. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Arya P., Sarkar A. K., Sustainability 2024, 16, 3098. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sunny G., Palani Rajan T., Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2024, 36, 304. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang H., Feng J., Lu J., Li R., Lu Y., Liu S., Cavaco‐Paulo A., Fu J., Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 2585. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen G., Zhou C., Xing L., Xing T., Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali T., Najam‐ul‐Haq M., Mohyuddin A., Musharraf S. G., Hussain D., Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 36, e00640. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Naebe M., Haque A. N. M. A., Haji A., Engineering 2022, 12, 145. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hossain M. T., Shahid M. A., Limon M. G. M., Hossain I., Mahmud N., J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100230. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Patti A., Cicala G., Acierno D., Polymers (Basel) 2020, 13, 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Patti A., Acierno D., Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bao H. Y., Hong Y., Yan T., Xie X., Zeng X., J. Text. Inst. 2024, 115, 1173. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pizzicato B., Pacifico S., Cayuela D., Mijas G., Riba‐Moliner M., Molecules 2023, 28, 5954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Radetić M., Marković D., Plasma Process. Polym. 2022, 19, 2100197. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eid B. M., Ibrahim N. A., J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 284, 124701. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Raj A., Chowdhury A., Ali S. W., Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 27, 100689. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu J., Huang Y., Zhu S., Abbes N., Jing X., Zhang L., J. Eng. Fiber. Fabr. 2021, 16. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saleem H., Zaidi S. J., Materials (Basel) 2020, 13, 5134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patti A., Acierno D., J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2023, 29, 589. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morais D. S., Guedes R. M., Lopes M. A., Materials 2016, 9, 498.28773619 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Horrocks A. R., Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2160.32971820 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Holmquist H., Schellenberger S., van der Veen I., Peters G. M., Leonards P. E. G., Cousins I. T., Environ. Int. 2016, 91, 251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bhandari V., Jose S., Badanayak P., Sankaran A., Anandan V., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 86. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meda U. S., Soundarya V. G., Madhu H., Bhat N., Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 296, 116636. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beigzadeh Z., Kolahdouzi M., Kalantary S., Golbabaei F., J. Ind. Text. 2024, 54, 1. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fernandes M., Padrão J., Ribeiro A. I., Fernandes R. D. V., Melro L., Nicolau T., Mehravani B., Alves C., Rodrigues R., Zille A., Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Syduzzaman M., Hassan A., Anik H. R., Akter M., Islam M. R., ChemNanoMat 2023, 9, 202300205. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siddiqua U. H., Zaib‐un‐Nisa, A. R. , Faheem M. S., Batool R., Ullah I., Sabir Q. U. A., Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 987. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Radetic´ M., Darka R. R., Markovic´ M., Radetic´ M. R., Markovic´innovation D., Cellulose 2019, 26, 8971. [Google Scholar]

- 38. de D Ferreira D., Melquiades F. L., Appoloni C. R., Text. Res. J. 2024, 94, 427. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Noman M. T., Petru M., Louda P., Kejzlar P., J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 4718. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Radetic´ T., Ogulata R. T., J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 8463. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dejene B. K., Geletaw T. M., Res. J. Text. Appar. 2023, 54. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Attia N. F., Elashery S. E. A., El‐Sayed F., Mohamed M., Osama R., Elmahdy E., Abd‐Ellah M., El‐Seedi H. R., Hawash H. B., Ameen H., Nano‐Struct. Nano‐Objects 2024, 38, 101180. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tassw D. F., Birlie B., Mamaye T., J. Text. Inst. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barman J., Tirkey A., Batra S., Paul A. A., Panda K., Deka R., Babu P. J., Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 104055. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ghahremani Honarvar M., Latifi M., J. Text. Inst. 2017, 108, 631. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shah M. A., Pirzada B. M., Price G., Shibiru A. L., Qurashi A., J. Adv. Res. 2022, 38, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Periyasamy A. P., Venkataraman M., Kremenakova D., Militky J., Zhou Y., Mater 2020, 13, 1838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sfameni S., Hadhri M., Rando G., Drommi D., Rosace G., Trovato V., Plutino M. R., Inorganics 2023, 11, 19. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Peran J., Ražić S. E., Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 1174. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Magovac E., Vončina B., Jordanov I., Grunlan J. C., Bischof S., Materials (Basel) 2022, 15, 432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rashid A., Albargi H. B., Irfan M., Qadir M. B., Ahmed A., Ferri A., Jalalah M., Text. Res. J. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ying S., Guan Z., Ofoegbu P. C., Clubb P., Rico C., He F., Hong J., Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102336. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Samuel M. S., Ravikumar M., John A., Selvarajan E., Patel H., Chander P. S., Soundarya J., Vuppala S., Balaji R., Chandrasekar N., Catalysts 2022, 12, 459. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Shreyash N., Bajpai S., Khan M. A., Vijay Y., Tiwary S. K., Sonker M., ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 11428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zille A., Almeida L., Amorim T., Carneiro N., Esteves M. F., Silva C. J., Souto A. P., Mater. Res. Express 2014, 1, 032003. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Shahid‐Ul‐Islam, M. S. , Mohammad F., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 5245. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Patti A., Costa F., Perrotti M., Barbarino D., Acierno D., Materials (Basel) 2021, 14, 1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Patti A., Acierno D., Text. Res. J. 2020, 90, 1201. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Omerogullari Basyigit Z., Coskun H., Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 1789. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pan G., Xiao X., Ye Z., Surf. Coatings Technol. 2019, 360, 318. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Shahidi S., Wiener J., in Antimicrobial Agents, InTech, London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Khan A., Nazir A., Rehman A., Naveed M., Ashraf M., Iqbal K., Basit A., Maqsood H. S., Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2020, 32, 869. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Patti A., Acierno D., Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 15. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tsuzuki T., Wang X., Res. J. Text. Appar. 2010, 14, 9. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gulati R., Sharma S., Sharma R. K., Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Armaković S. J., Savanović M. M., Armaković S., Catalysts 2023, 13, 26. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rashid M. M., Simončič B., Tomšič B., Surfaces and Interfaces 2021, 22, 100890. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Subramani K., Incharoensakdi A., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 263, 130391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mohammadipour‐Nodoushan R., Shekarriz S., Shariatinia Z., Heydari A., Montazer M., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]