Abstract

Introduction:

Parenting programs are widely used to prevent and ameliorate children’s emotional and behavioral problems but low levels of engagement undermine intervention effectiveness and reach within and beyond research settings. Technology can provide flexible and cost-effective alternate service-delivery formats for parenting programs, and studies are needed to assess the extent to which parents are willing to engage with digitally assisted formats.

Methods:

After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools (ADAPT) is an evidence-based parenting program for military families. In the current comparative effectiveness trial, families were randomly assigned to either an in-person group (n = 95), self-directed online (n = 78), or individual telehealth (n = 71) formats of ADAPT. We explored whether children’s initial problem severity, parenting efficacy, parental depression, household income, child age, child gender, parental deployment length, and waiting time were related to parental engagement across different delivery formats. Zero-inflated Poisson regressions were used due to the distribution of the number of attended sessions.

Results:

Compared to the in-person group format, parents in the individual telehealth and self-directed online formats had higher engagement levels. For the in-person format, parents who perceived their children as having more severe problems were more likely to enroll and families with a father deployed for longer time attended fewer sessions. In the self-directed online format, families with less depressed fathers were more likely to enroll. No predictors were found for the telehealth format. For all three formats, once parents took the first step to engage, they were likely to finish all sessions.

Discussion:

Technology-assisted delivery formats have the potential to improve program engagement. Results from this study will help facilitate the development of specific strategies to promote engagement in the future.

Keywords: Parenting program, Telehealth, Online, Engagement, Enrollment, Attendance

1. Introduction

Behavioral parent training programs are clearly defined programs that aim to improve parents’ knowledge and skills for managing their children’s behavior, with the goal of preventing children’s mental, emotional, and behavioral health concerns. So far, preventive parenting programs have an excellent evidence base demonstrating their effectiveness (e.g., Sandler et al., 2015), yet in order for these programs to have any impact on children’s behavioral health at a population level, parents have to be willing to engage with the programs (Sanders et al., 2017).

Many programs report challenges with enrolling parents and sustaining their engagement. In fact, data from 262 parenting programs indicated that more than half of participating parents drop out prior to program completion (Chacko et al., 2016), posing a real threat to the potential benefit and effectiveness of programs implemented in community and practice settings. Despite an increasing body of research investigating program engagement, questions remain about what barriers prevent parents from enrolling and attending parenting programs, and how those barriers might be overcome.

1.1. Engagement in parenting programs

Although parental engagement is variably defined and measured across studies, engagement generally describes the extent to which parents are involved with a parenting program (Chacko et al., 2016). Measures of engagement include enrollment (or initial engagement), attendance at sessions (or ongoing engagement), completion of home practice assignments, in-session behaviors and responsiveness, and use of physical or online practice materials. The current paper focused on two of the most widely studied components of engagement: enrollment and attendance. Enrollment, or initial engagement, is defined as committing to participate and attending at least one session of a program. Ongoing engagement, most commonly measured by attendance, is defined as the total number or proportion of sessions attended by parents across the course of program delivery (Chacko et al., 2016).

From a family systems perspective, factors commonly related to enrollment and attendance in parenting programs include context- (e.g., socioeconomic status [SES]), child- (e.g., the severity of child behaviors), parent- (e.g., parental efficacy), intervention- (e.g., delivery format), and facilitator-specific characteristics (e.g., the therapeutic relationship, fidelity, skills) (e.g., Basha, 2022; Morawska and Sanders, 2006). The Health Belief Model (HBM; Spoth et al., 2000), proposes that parental perceptions about benefits and barriers to participating in interventions are key to understanding engagement in family-focused prevention programs. Specifically, when parents believe their family can benefit more and have fewer barriers to accessing the program, they are more likely to enroll and attend more sessions (e.g., Mytton et al., 2014).

Although predictors of engagement have been found to be inconsistent across studies, evidence generally supports the HBM (Spoth et al., 2000). Factors impacting enrollment might include lack of interest or perceived need, lack of knowledge of availability, logistical barriers such as lack of transportation, childcare, work schedule conflicts, long waiting period, and perceptions that the program will not be helpful (Whittaker & Cowley, 2012). Parents may be more likely to enroll in programs if they report their child has mental health needs, if the parents have stable social supports, higher self-efficacy, and beliefs that the program is both relevant and potentially beneficial (Finan et al., 2018). However, existing literature (e.g., Finan et al., 2018; Haine-Schlagel et al., 2022) has yet to reveal a clear set of factors that impact ongoing attendance after enrollment across studies. Yet, logistical barriers (e.g., transportation or financial constraints, longer waiting time), more severe child mental health challenges, and incentivization (e.g., paying participants) have all been shown to influence attendance.

1.2. Technology and parent engagement

Technology-assisted delivery of parenting programs, such as provider-directed telehealth or self-directed online programs, might increase parents’ engagement given the higher levels of accessibility and flexibility (i.e., fewer barriers) associated with these delivery formats. Provider-directed telehealth uses communication technology tools like videoconferencing to provide clinical care from a distance (Stamm, 1998) extending the reach of evidence-based clinical care at a comparatively low cost. Self-directed online parenting programs offer an increased level of flexibility as families can access the web content when, where, and how they want, and can visit repeatedly, without scheduling with a provider.

In the past two decades, technology-assisted delivery formats have gained increasing importance in supporting family well-being (e.g., Chi & Demiris, 2015). The importance of such delivery formats was further accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic, as many in-person parenting programs either ceased functioning or shifted to a virtual format in 2020 and beyond (e.g., Britwum et al., 2020; Cook et al., 2021). Although technology-assisted parenting programs have shown the potential to enhance accessibility and engagement (e.g., Hall et al., 2015), questions remain regarding predictors of successful engagement with technology-supported programs. Yet few programs have been intentionally designed to compare engagement levels between in-person and virtual delivery formats.

1.3. After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools

After Deployment, Adaptive Parenting Tools (now known as Adaptive Parenting Tools/ADAPT) is the first and, to-date, the only evidence-based preventive parenting program for military families with school-aged children in which a parent was deployed to war with the National Guard or Reserves (Gewirtz et al., 2018). The original ADAPT program consisted of 14 weekly in-person group sessions, with home practices and supportive online components. However, military parents face challenges associated with their geographic diversity. Parents who live in rural communities might have little access to mental health and/or parenting professionals, while parents living in more densely populated areas are often faced with long waitlists to see a provider. To address those challenges, both individual telehealth and self-directed online delivery formats were developed to enhance accessibility and reach for military families. Results from the current comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial demonstrated that families in both the in-person group and telehealth conditions showed significant improvements in observed parenting one-year postbaseline compared to those assigned to the self-directed online condition (Gewirtz et al., 2024).

1.4. The current study

The current study investigated participant engagement across three delivery formats (i.e., in-person groups, individual telehealth, and self-directed online) of the ADAPT program and explored whether parent, child, and family characteristics were related to parent engagement with the program. Using data from a comparative effectiveness trial of ADAPT, two primary aims were assessed. First, patterns of engagement were identified (i.e., enrollment and attendance) and then compared across the different delivery formats (Aim 1). Given technology technology-assisted formats are more flexible with fewer logistical barriers, we hypothesized that families in the individual telehealth and self-directed online formats would have higher levels of engagement compared to the in-person groups. Second, we explored whether parent-(parental depression, parental efficacy, deployment length), child- (child behavioral problem severity), family- (income), and logistical- (waiting time) characteristics were related to parental engagement across different delivery formats (Aim 2). From a family systems perspective, deployment can disrupt family functioning by increasing parental stress. For example, the prolonged absence of a parent may make attending or prioritizing a preventive parenting intervention more difficult for the remaining parent or may result in a shift in parenting duties that may preclude one parent’s attendance. Thus, we hypothesized that families would generally show higher engagement with shorter deployment lengths, higher parental efficacy, lower parental depression, more severe child behavioral problems, and shorter waiting periods. Given the limited information available on how these factors may act differentially across different delivery formats, no specific hypothesis was made for each delivery format.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

In total, 244 military families participated in the ADAPT4U program, a comparative effectiveness trial of a military parenting program for National Guard and Reserve families delivered in three formats: in-person groups, individual telehealth, and self-directed online modules. Eligible families met the following criteria: 1) lived in one of two midwestern states in the United States of America, 2) had at least one parent in the US military and deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan after 9/11/2001, and 3) had at least one 5 to 12-year-old child living at home. For each family, we only collected data from one child to avoid statistical problems of dependency or nesting. Of 361 families who were screened, 244 (67.6 %) met the eligibility criteria, agreed to participate, and completed baseline assessments. On average, fathers were 37.6 years old (SD = 5.8), mothers were 35.9 years old (SD = 5.7), and target children were 7.7 years old (SD = 2.3; 49.2 % girls). Detailed demographic information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic information of families in the ADAPT4U (N = 244), shown as mean (SD), Median, or n (%).

| Fathers (n = 191) | Mothers (n = 219) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age M (SD) | 37.57 (5.81) | 35.92 (5.67) |

| Race n (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 165 (86.4 %) | 193 (88.1 %) |

| African American | 14 (5.7 %) | 10 (4.6 %) |

| Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (0.5 %) |

| Asian | 3 (1.2 %) | 3 (1.4 %) |

| Native American | 2 (0.8 %) | 3 (1.4 %) |

| Multi-racial | 3 (1.2 %) | 7 (3.2 %) |

| Marriage Status n (%) | ||

| Married or cohabiting | 170 (89 %) | 190 (87.1 %) |

| Separated or divorced | 12 (6.3 %) | 18 (8.2 %) |

| Single | 8 (4.2 %) | 10 (4.6) |

| Education n (%) | ||

| High School or less | 15 (7.9 %) | 10 (4.6 %) |

| Some college/Associate degree | 100 (52.4 %) | 87 (39.7 %) |

| Bachelors’ degree | 50 (26.2 %) | 86 (37.9 %) |

| Master’s degree or Higher | 26 (13.6 %) | 39 (17.8 %) |

| Income Mdn | $51,000 to $80,000 | |

| Ever in military n (%) | 182 (95.3 %) | 77 (35.2 %) |

| Ever been deployed n (%) | 180 (94.2 %) | 34 (12.5 %) |

| Deployment Length M (SD)a | 18.86 (12.45) | 3.8 (7.63) |

| Month Returned M (SD)b | 67.3 (50.3) | 88.6 (51.5) |

| Children (n = 244) | ||

| Age M (SD) | 7.67 (2.28) | |

| Girl n (%) | 120 (49.2 %) | |

Note.

Deployment length: coded in months, and participants who were never deployed were coded as 0.

Month returned: month returned from the last deployment was calculated only using participants who had been deployed overseas.

2.2. Procedure

Participants were recruited through flyers distributed to National Guard and Reserve Units, local Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, and community organizations serving military families. Project staff also engaged in outreach and recruitment efforts through presentations at schools, in the community, and at mandatory National Guard and Reserve events. Additional families were recruited via word of mouth. Participants who met the eligibility criteria and gave consent were included in the study. After consent, families completed the baseline online and in-home assessments that were conducted by trained research technicians. After baseline assessments, families were randomly assigned to one of the three delivery formats: in-person groups (n = 95), individualized telehealth (n = 71), or self-directed online modules (n = 78). A detailed description of the program content can be found in Gewirtz et al. (2014). All ADAPT facilitators were trained and provided with ongoing coaching and some had previous experience delivering ADAPT.

A multi-stage process was used to modify the original in-person group-based curriculum to one suitable for individualized telehealth delivery. This process included modifying group-based content to be appropriate for delivery in an individual format, condensing the two-hour sessions to a single hour, and training facilitators on how to actively engage parents during virtual sessions. The self-directed online ADAPT program was developed to be used by families without any professional assistance. ADAPT online included 10 modules that teach the same skills taught in the provider-delivered versions by using skill videos through which parents are shown scripted, acted-out videos of parents using more and less effective ways to deliver parenting practices like directions, encouragement, problem-solving, and emotion coaching. Additional practice videos were created to show parents and children practicing the skills taught in each skill video module, and PDF summaries, quizzes, home practice assignments, and weekly emails were used to reinforce program content and encourage parents to practice offline. The online course was limited to 10 modules given concerns that 14 modules constituted too great a commitment for busy families without facilitator support.

Families assigned to the in-person group format were grouped into cohorts of 5–10 families who then participated in 14 in-person weekly sessions with two or three ADAPT facilitators at community locations (e. g., schools or public libraries) chosen based on geographic proximity to the cohort families. In the current study, some cohorts received 12 or 13 sessions (covering the full curriculum but condensed into fewer sessions) as a result of cancellations due to bad weather or holidays. Families assigned to the individual telehealth format participated in 14 one-hour weekly sessions via video conferencing software (WebEx). Sessions were typically scheduled at the same time each week, at the parents’ and facilitator’s convenience. Families assigned to the in-person group and telehealth also had access to the online modules for additional practice. Parents in both the group and telehealth formats also received phone calls from facilitators between sessions to address questions and troubleshoot home practice assignments. Families in the self-directed online format had access to the 10-session ADAPTonline modules, including video demonstrations of parenting skills, audio mindfulness exercises, handouts with summaries, and home practice assignments. In lieu of mid-week phone calls, parents in the online format received weekly check-in emails to address questions and troubleshoot challenges.

2.3. Measures

This study utilizes data collected at baseline and during the program delivery.

2.3.1. Program engagement

Parents’ engagement was assessed using family initial enrollment and attendance. In the self-directed online format, both enrollment and attendance were tracked at the family level, as the system only recorded module completion for families and not individual parents (as many families share a home computer). For the in-person group and telehealth formats, attendance was recorded individually for parents at each session and families were considered as having attended if at least one parent was present at the session. It is important to note that attendance was only recorded when participants showed up for previously scheduled sessions. While the telehealth format offered a level of flexibility such that families and providers could reschedule sessions, no-notice-no-shows and/or make-ups were not included in our attendance variable. In the current study, engagement refers to the total number of sessions attended by each family (range from 0 to 14), enrollment refers to whether the family attended at least one session/completed one online module (0 = attended 0 session, 1 = attended one or more sessions), and continuing attendance refers to the number of sessions attended by enrolled families (range from 1 to 14).

2.3.2. Parental depression

Mother’s and father’s depressive symptoms were measured separately using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD; Radloff, 1977). Parents reported the frequency of their depressive symptoms over the past week, such as feelings of depression/sadness, sense of hopelessness, and sleep disturbances, on a scale of 0 (rarely or none) to 3 (all of the time). Average scores across items were calculated to represent individual parent’s depression levels, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. High internal consistency was demonstrated for both mothers (α = 0.93) and fathers (α = 0.94).

2.3.3. Parental efficacy

Parents’ sense of parental efficacy was measured with the Parenting Locus of Control-Short Form Revised (PLOC-SFR; Hassall et al., 2005). The 24-item measure includes four subscales: parental efficacy, parental responsibility, child control of parents’ life, and parental control of child’s behavior. However, this study only utilized the 6-item parental efficacy subscale due to an administrative error that resulted in some parents not receiving the other three subscales. The measure uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree) and includes items such as “I am often able to predict my child’s behavior in situations.” An average score across mothers and fathers was created, with higher scores indicating a higher sense of parental efficacy in the family.

2.3.4. Children’s behavioral problems

Parent reports of their children’s behavioral severity were gathered using the Behavioral Symptom Index (BSI) from the Behavior Assessment System for Children-2 (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2006). This index score provides an overall rating of children’s level of behavioral problems, including hyperactivity, aggression, depression, attention problems, atypicality, and withdrawal symptoms. This index is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never to 4 = almost always), with raw scores being transformed into age- and gender-specific normative T-scores. Mother’s and father’s reports of their child’s behavioral problems were averaged together, with higher scores indicating more severe behavioral problems at baseline.

2.3.5. Waiting period

Parents were randomized only after completing the baseline in-home assessment. Thus, we calculated the waiting period (in months) between the in-home assessment date and the scheduled date of the first intervention session. Parents who dropped out prior to scheduling their first session were considered as missing as they inherently had no scheduled date for their first session.

2.3.6. Demographic information

Demographic variables included children’s sex (1 = boys, 2 = girls), age at baseline (in years), the total number of months that parents were deployed for, and household income (coded in increments of US$10,000 ranging from 1 to 16 where 1 = less than $10,000 per year, 2 = $10,000 to 19,999… 16 = $150,000 or more).

2.4. Analytic plan

Preliminary analyses included descriptive statistics (Mean, SD), normality tests, bivariate correlations, and missing data analysis for all raw variables in the model. The percentage of missing data for these variables ranged from 0 to 29.46 %, with 10.46 % of the total values missing. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test confirmed that the data were missing completely at random (χ2 (242) = 276.242, p = 0.064). Multiple imputation (MI) using Fully Conditional Specification (FCS) with the MICE package in RStudio (version 3.13, Van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011) was conducted to handle missing data, generating 100 imputations to obtain statistical power (Graham et al., 2007).

To investigate differences in continuous independent variables among delivery formats (i.e., in-person group, telehealth, and online), we employed one-way ANOVAs, which are robust to skewness, especially with larger sample sizes (Blanca et al., 2017; Curran et al., 1996). Chi-square was used to detect potential differences in categorical independent variables across delivery formats. Parental engagement (i.e., the total number of attended sessions, ranging from 0 – 14) was assessed for zero-inflation using the Performance package in RStudio (Lüdecke et al., 2021). The results supported the zero-inflated distribution, showing that the number of observed zeros was significantly larger than the number of predicted zeros in all three formats (in-person group: predicted zero/observed zero ratio = 0.02; telehealth: ratio = 0; online: ratio = 0.07).

To address Aim 1, chi-square tests were used to compare the enrollment levels (coded as 0 = 0 session, 1 = one or more sessions) and dropout time (coded as 0 = prior to scheduling the first session, 1 = after scheduling for the first session) across three delivery formats. Given the variation in available sessions across formats, the proportion of attended sessions was calculated, and one-way ANOVA was used to detect differences across delivery formats. Since the dependent variable (engagement) was zero-inflated, zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression models were used to address Aim 2. The ZIP model is widely used to analyze count data with excessive zeros, including both a binary process (i.e., logistic regression) modeling the occurrence of the excess zeros and a Poisson process (i.e., Poisson regression) modeling positive (non-zero) counts (Hilbe, 2011; Zeileis, et al., 2008). In this study, ZIP models were used to simultaneously identify predictors of enrollment (i.e., a binary process, which predicts whether families enrolled in at least one session) and continuing attendance (i.e., a Poisson process to examine what predicts more attended sessions for enrolled families). To assess the impact of the waiting period on enrollment across all three formats, we conducted independent t-tests, given that data imputation was not appropriate due to missing data from families who dropped out before scheduling was not completely at random. All analyses were conducted using RStudio Version 2021.09.1 (R Studio Team, 2021).

3. Results

3.1. Patterns of engagement across delivery formats

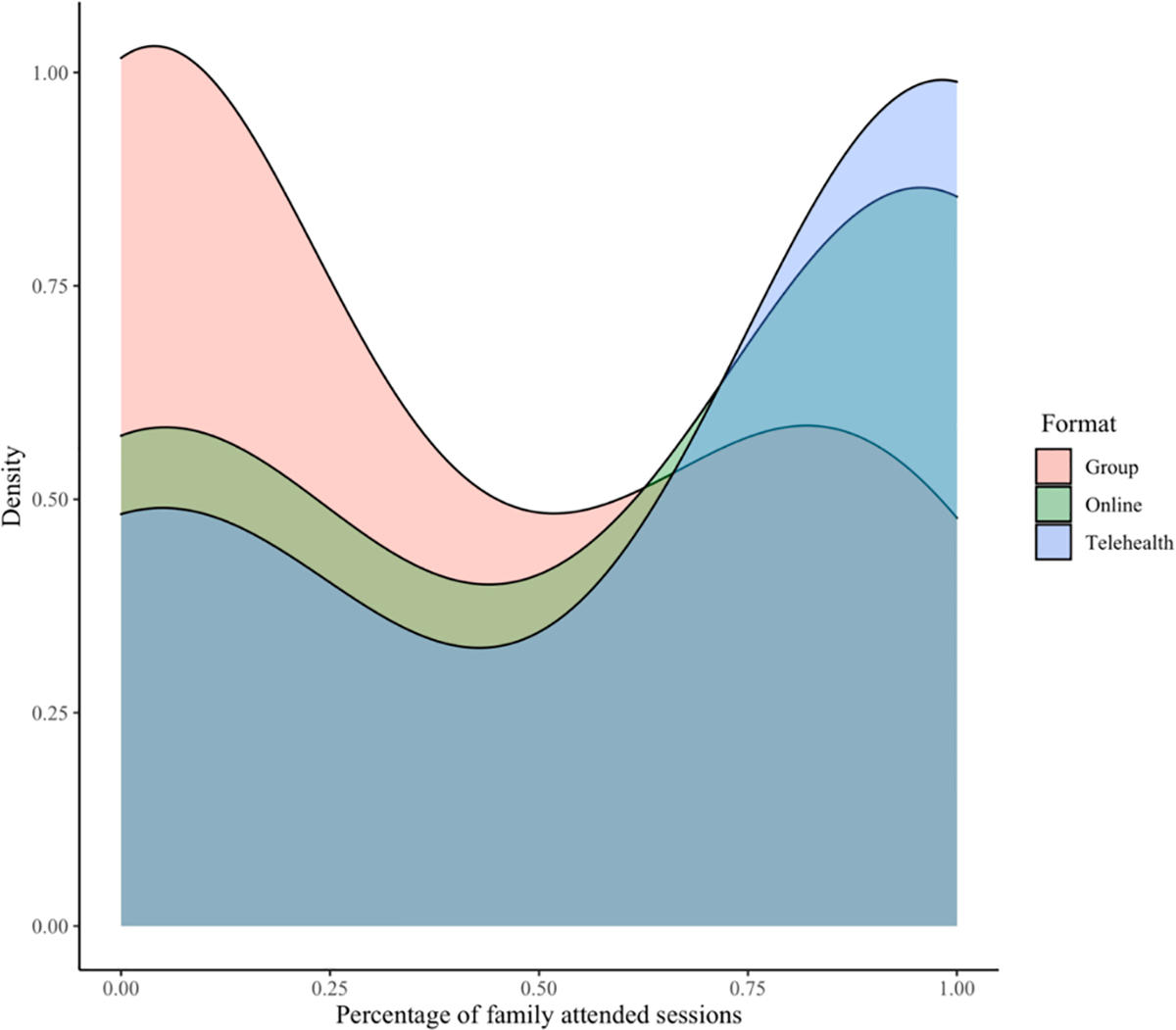

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among the main variables are shown in Table 2. One-way ANOVA did not reveal significant differences across formats on paternal depression, maternal depression, parental efficacy, child behavior problems, child age, household income, paternal or maternal deployment length (ps > 0.05). Chi-square tests did not find significant differences across formats on child gender (ps > 0.05). Fig. 1 shows the distributions of family attendance for the three delivery formats. As indicated by the binomial distribution, parents in all formats either attended no sessions or attended most of the sessions available to them.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics (Means, Standard Deviations or SD, Sample Size or N, and skewness) and bivariate correlations of main variables for the families attending ADAPT4U (N = 244).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Paternal depression | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 2. Maternal depression | 0.20* | 1.00 | |||||||

| 3. Parental efficacy | − 0.28* | − 0.11* | 1.00 | ||||||

| 4. Child behavior problems | 0.32* | 0.20 | − 0.32* | 1.00 | |||||

| 5. Child age | 0.07 | 0.11 | − 0.11 | 0.01 | 1.00 | ||||

| 6. Household Income | − 0.33* | − 0.20* | 0.17* | − 0.16* | − 0.04 | 1.00 | |||

| 7. Paternal deployment length | − 0.07 | − 0.19* | − 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.00 | ||

| 8. Maternal deployment length | − 0.20* | 0.08 | 0.09 | − 0.02 | − 0.13 | 0.02 | − 0.14 | 1.00 | |

| 9. Engagement | − 0.16* | − 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.07 | − 0.08 | 0.05 | − 0.03 | 0.14* | 1.00 |

| N | 188 | 216 | 238 | 228 | 243 | 243 | 189 | 219 | 244 |

| Mean | 14.53 | 12.83 | 4.38 | 52.99 | 7.67 | 3.50 | 18.86 | 3.80 | 6.44 |

| SD | 12.53 | 11.66 | 0.45 | 9.04 | 2.29 | 1.46 | 12.45 | 7.63 | 5.69 |

| Skewness | 1.25 | 1.40 | −1.08 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 1.35 | 0.32 | 0.05 |

Note. Engagement: total number of attended sessions for families.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of attended sessions, by format.

Table 3 displayed the enrollment data across different format, including parents who dropped out prior to scheduling their 1st session, parents who dropped out after scheduling their 1st session, and parents who attended at least one session. Overall, 54 % families assigned to the group format, 75 % families to the telehealth format, and 71 % families to the self-directed online format enrolled in at least one session of the program. Post-hoc chi-square tests showed that families in the telehealth (X2(1) = 7.63, p = 0.005) and self-directed online formats (X2(1) = 5.11, p = 0.02) were more likely to enroll compared to families in the group format, while no enrollment differences were found between telehealth and online (X2(1) = 0.32, p = 0.57). When evaluating at what point families dropped out, post-hoc chi-square tests showed that compared to families in the group format, families in the telehealth format were less likely to drop out prior to scheduling (X2(1) = 22.29, p < 0.001) while families in the online format were less likely to drop out after scheduling (X2(1) = 7.35, p = 0.006). Post-hoc ANOVA test also revealed that families in the group format had significantly longer waiting periods compared to the telehealth format (p < 0.001) and self-directed online format (p < 0.001), while families in the telehealth format also had significantly longer waiting periods compared to the self-directed online format (p = 0.03).

Table 3.

Engagement across different formats.

| In-person Group (n = 95) | Telehealth (n = 71) | Self-directed Online (n = 75) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dropout prior to scheduling | 15 (15.8 %) | 18 (25.4 %) | 1 (1.3 %) |

| Dropout after scheduling | 29 (30.5 %) | 0 (0 %) | 22 (29.3 %) |

| Attended at least one session | 51 (53.7 %) | 53 (74.6 %) | 55 (73.3 %) |

| Attended session for enrolled families (Mean/SD) | 8.9 (4.1) | 12.4 (3.5) | 8.31 (2.8) |

| Waiting period in months (Mean/SD) | 5.71 (5.21) | 2.70 (1.93) | 1.96 (1.70) |

Note. Waiting period: between the in-home assessment date and the scheduled date of the first session.

Of those who attended at least one session, on average, families attended 8.9 sessions (SD = 4.1, 66 %) in the group format, 12.4 sessions (SD = 3.5, 89 %) in the telehealth format, and 8.31 sessions (SD = 2.8, 83 %) in the online format. One-way ANOVA tests after Bonferroni correction showed that compared to families in the group format, families in the telehealth (p < 0.001) and online formats (p = 0.004) attended a greater proportion of available sessions, while no significant difference was found between families in the telehealth and online formats (p = 0.90). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

3.2. Predictors of engagement by format

Separate ZIPs were fit to determine if there were differences in the predictors of engagement across the three delivery formats (see Table 4). Families in the in-person group format were more likely to have attended one or more sessions if the parents perceived higher levels of behavioral problem severity in their children (b = 0.068, SE = 0.030, p = 0.029), but attended fewer numbers of sessions the longer the fathers had been deployed (b = −0.013, SE = 0.005, p = 0.016). Enrollment and attendance in the telehealth format were not significantly associated with any predictor variables measured in this study. For families in the online format, fathers’ depression was negatively related to whether families initially engaged (b = −0.059, SE = 0.029, p = 0.048), such that if fathers had a higher number of depressive symptoms, families were less likely to have enrolled. Additionally, families with higher incomes tended to attend fewer sessions (b = −0.074, SE = 0.038, p = 0.054), but no other significant predictors were found. Thus, results indicated that children’s initial problem severity and the length of time that fathers were deployed were important correlates of engagement for families in the in-person group format, while fathers’ level of depression and household income were associated with engagement for families in the self-directed online format. Interestingly, independent t-tests revealed that families whose wait times were shorter were significantly more likely to enroll in the program than those with longer wait times in the group format (non-enrollment: M = 4.25, SD = 3.77; enrollment: M = 8.28, SD = 6.37; t = 3.10, p = 0.004). No significant difference was found in the online format (non-enrollment: M = 2.09, SD = 1.72; enrollment: M = 1.91, SD = 1.70; t = 0.42, p = 0.68) and all families attended at least one session after scheduling in the telehealth format. Thus, hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

Table 4.

Zero-inflated Poisson models to predict the overall number of sessions attended by families in the group (N = 95), telehealth (N = 71), and online (N = 78) formats, separately.

| Enrollment | Continuing Attendance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b |

SE

(b) |

p | b |

SE

(b) |

p | |

| Group | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.94 | 4.01 | 0.814 | 2.63** | 0.85 | 0.003 |

| Paternal depression | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.154 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.182 |

| Maternal depression | − 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.458 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.463 |

| Parental efficacy | 0.02 | 0.62 | 0.974 | − 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.424 |

| Child behavior problems | − 0.07* | 0.03 | 0.029 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.782 |

| Child gender | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.145 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.163 |

| Child age | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.772 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.876 |

| Household Income | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.170 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.443 |

| Paternal deployment length | − 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.780 | − 0.01* | 0.01 | 0.016 |

| Maternal deployment length | − 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.299 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.970 |

| Telehealth | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.02 | 4.37 | 0.996 | 2.09* | 0.80 | 0.013 |

| Paternal depression | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.914 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.814 |

| Maternal depression | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.488 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.299 |

| Parental efficacy | − 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.215 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.851 |

| Child behavior problems | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.811 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.421 |

| Child gender | 0.27 | 0.73 | 0.714 | − 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.853 |

| Child age | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.372 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.799 |

| Household Income | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.996 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.314 |

| Paternal deployment length | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.580 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.799 |

| Maternal deployment | − 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.311 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.262 |

| length | ||||||

| Online | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.52 | 4.15 | 0.715 | 1.71 | 0.88 | 0.056 |

| Paternal depression | 0.06* | 0.03 | 0.048 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.720 |

| Maternal depression | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.327 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.809 |

| Parental efficacy | − 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.312 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.655 |

| Child behavior problems | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.425 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.861 |

| Child gender | 0.10 | 0.59 | 0.866 | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.660 |

| Child age | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.297 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.677 |

| Household Income | − 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.880 | − 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.054 |

| Paternal deployment length | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.784 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.099 |

| Maternal deployment length | − 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.889 | − 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.473 |

Note.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall engagement level

As more parenting programs shift from traditional in-person to virtual modalities, it is crucial to understand how engagement differs across formats. It is noteworthy that the distributions of attended sessions for all three formats were zero-inflated, i.e., families either did not enroll in the program or attended most of the available sessions. Most families, then, appear to have been hooked once they attended one session and motivated to attend most sessions of the program. This pattern, however, is not unique in the field of parental engagement. LoBraico and colleagues (2021) found that of those attending at least one session, two-thirds of the parents were consistently high attendees. It is possible that once parents enroll, they find the program useful, important, and interesting, thereby raising their commitment to completing the program. Previous research (e.g., Chacko et al., 2017) has differentiated completers, enrollers, and nonattenders in group-delivered behavioral parenting training based on parental factors, such as parental distress and parental efficacy. Future research should continue exploring what distinguishes consistent attenders from nonattenders and should design specific strategies to attract parents to attend preventive parenting interventions, particularly across different delivery formats.

Technology-assisted delivery, including individual telehealth and self-directed online delivery formats, was associated with significantly higher parent enrollment and continuing attendance levels, compared to the in-person group format. The convenience of telehealth and self-directed online delivery formats may reduce barriers to engagement and thus motivate more families to enroll and maintain high levels of retention, while in-person group formats require more commitment (time, travel, etc.) and are more susceptible to being interrupted by life circumstances. While the telehealth and self-directed online formats both provided flexibility that can potentially enhance engagement, results indicated that families in the telehealth format were more likely to drop out prior to scheduling, while families in the online format were more likely to drop out after having access to the material. These results highlight the different nature of those two delivery formats and the need for targeted strategies to improve engagement for those participating in technology-assisted delivery formats. Interestingly, the study also found that logistical barriers, such as long waiting periods can impact parental enrollment in group-based behavioral parenting programs, but not in telehealth or online formats.

Importantly, telehealth and self-directed online delivery allow for large-scale implementation of existing evidence-based practices, which also may more easily reach remote areas (Stormshak et al., 2021) and historically underserved families, including ethnic minorities (Stewart et al., 2020), refugees (Simenec et al., 2022a), and low-income families (Choi et al., 2014). During the COVID-19 pandemic where in-person contact was limited and parenting became more challenging, technology-assisted parenting resources were crucial to support parents under stress (Zhou et al., 2020; Fogarty et al., 2021), particularly for those families disproportionately affected by the pandemic (i.e., minority and low SES groups; Brown et al., 2020). However, there is some concern about equitable access to telehealth services due to technological barriers. As with any new technology, parents’ comfort level with telehealth and online services can make them less desirable substitutes for in-person services (Buchanan et al., 2022). As such, behavioral health leaders and practitioners should consider innovative delivery models to extend the reach of parenting programs while also considering the unique needs and preferences of families to provide comprehensive and accessible support, as suggested by Corralejo and Domenech Rodríguez (2018).

4.2. Barriers and facilitators to engagement in preventive parenting programs

The current study found that children’s problem severity was positively related to parental enrollment level, but only for families in the in-person group format. The results were partially consistent with those of Finan et al. (2018) in which children’s initial problem severity was a consistent predictor of parental engagement across studies. It is noteworthy that most programs included in the Finan et al. (2018) study were delivered in person. Consistent with our results, two previous studies found that baseline children’s problem severity was not related to program completion in telehealth or self-directed online parenting programs (Day et al., 2021; Ingersoll & Berger, 2015). From the perspective of the HBM (Spoth et al., 2000), parents of children with more severe behavior problems might perceive more benefit from the program such that they were willing to put significant effort into participating. On the other hand, when accessing parenting programs is easy and convenient (i.e., fewer barriers), parents appear to be willing to learn new parenting skills regardless of children’s problem severity. This finding is critical for preventive parenting programs in particular, which often suffer low parent enrollment rates because busy parents may not see the need to spend time, energy, and other resources on a parenting program when they do not see problems with their children’s behavior (Finan et al., 2020). More studies are needed to see whether the result is replicable and if so, whether parents’ perceptions of the convenience of telehealth and online programs can explain the result.

Additionally, fathers’ depression level was negatively associated with enrollment, particularly in the self-directed online format. The results were also consistent with previous studies in which parents with more depressive symptoms (Ingersoll & Berger, 2015) or adjustment problems (Day et al., 2021) were less likely to complete online parenting programs. Although the self-directed online delivery format was designed to be convenient and easy to use, it might require more regulatory skills and intrinsic motivation of parents given the lack of professional guidance and accountability (Mohr et al., 2011). In families with fathers suffering from depression, parents might not have had enough motivation or internal resources to complete the online modules, and/or might perceive parenting programs as less relevant. However, research has shown that parenting programs such as ADAPT that teach self-regulation skills to parents improve parental mental health (Gewirtz et al., 2016). Coordinated care, then, could support parents in treatment for depression to also participate in a parenting group.

This study did not find predictors for family enrollment in the individual telehealth format. The individual telehealth format appears flexible enough for families, and direct contact with ADAPT facilitators can also hold parents accountable, potentially increasing the number of sessions they would attend. Additionally, participation in individual programming, as opposed to group programming, creates additional opportunity for the participants to engage during the sessions, like providing examples or having discussions specific to their family, practicing skills directly with a facilitator, and receiving intensive troubleshooting on challenges they might have encountered during home practice, thus increasing the relevance of the program material. However, one-on-one sessions, even via telehealth, are more facilitator-intensive and tend to be less scalable than either group or self-directed online formats, in which several families can be seen at once, or families can receive the content without the presence of a facilitator. Nevertheless, 25 % of the participants did not enroll in the individual telehealth format, indicating that additional support is needed for those families who showed initial interest but did not proceed with scheduling and further engagement. For example, Chacko and colleagues (2012) successfully improved enrollment and attendance for group based behavioral parenting training through the use of comprehensive strategies, including an enhanced intake process and clear communication on treatment expectation. Future research should explore whether similar strategies can enhance engagement in telehealth formats, especially in preventive parenting interventions.

Other than delivery format, no significant predictors were found for family continuing attendance in general. However, several predictors were identified for separate formats. It appears that fathers’ deployment length negatively impacted the family’s ability to participate in more sessions in the in-person group format, which might suggest that fathers who were deployed for longer periods of time were less likely to participate as frequently in the in-person group format. Future research should focus on developing targeted strategies (e.g., communication that addresses the unique challenges faced by post-deployed families such as being united as parents after deployment, flexible scheduling, etc.) to better meet the needs of post-deployed families. Additionally, household income was negatively related to the number of modules families completed in the self-directed online format. It is possible that, in this sample, families with higher incomes had the resources required to seek help or treatment in other capacities (e.g., through private practice clinics).

4.3. Strengths, Limitations, and Future directions

While previous research has indicated that parents are more likely to engage in technology-assisted parenting programs, the current study appears to be the first comparative effectiveness trial for a preventive parenting program with different delivery formats. The rigorous design allows us to directly compare engagement across delivery formats and explore unique predictors of engagement in different formats. Moreover, using a family system perspective, the study included both parents in the analysis, providing a more comprehensive understanding of factors that impact engagement in parenting programs. The results of the study can be used to inform future research that aims to develop strategies based on family characteristics to improve program engagement, which can potentially enhance program reach and effectiveness within and beyond research settings.

Despite its strengths, this study is also limited in various ways. First, families assigned to the in-person group and telehealth formats also had access to the online modules, which may have impacted their motivation to engage in the assigned formats. Second, while evidence from prior research supports the effectiveness of online formats (e.g., McAloon & Armstrong, 2024), the absence of a no-intervention control group limited our ability to demonstrate the efficacy of the self-directed online condition. Nevertheless, the high levels of engagement observed in the self-directed online format provided promising indications of its potential utility. In addition, the sample also was relatively homogenous, with primarily middle-class and White military families with high levels of stress and frequent transitions due to the demands placed on the United States military service members. Although the sample appears representative of National Guard families according to the Department of Defense (2022), this study required families to express interest to participate, and the outreach efforts might not be enough to recruit a sample that fully captures the diversity of the broader military community. As such, the results may not generalize to other populations, though they may be applicable to other families experiencing high levels of stress and transition. Additionally, missing data for some participants’ last contact date limited our ability to fully understand how waiting periods can impact family’s engagement, especially in group-based preventive parenting programs. Future studies should explore the effectiveness of self-directed online parenting interventions and whether the same results are found in other countries and populations.

5. Conclusion

As more preventive parenting programs shift from traditional in-person to virtual modalities, it is crucial to understand how engagement differs across formats. Families engaged more when they were randomized to the self-directed online or individual telehealth formats, compared to the in-person group format. Notably, families not experiencing concerning child behavior were less likely to initiate engagement in the in-person group format, while families with more depressed fathers struggled to initiate engagement in the self-directed online format. Ongoing engagement was also affected by demographic factors such as deployment length and household income. Families with fathers who had been deployed longer were less likely to remain engaged with in-person groups and families with higher incomes were less likely to remain engaged in the self-directed online format. Findings from this study indicate that technology-assisted delivery formats can be important tools to promote parents’ engagement with preventive parenting programs.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The research was funded by the Department of Defense W81XWH-14-1-0143; W81XWH-16-1-0407.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities (IRB number: #1407S52001) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qiyue Cai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Gretchen Buchanan: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Tori Simenec: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Sun-Kyung Lee: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Sydni Basha: Writing – review & editing. Abigail Gewirtz: Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107686.

Availability of Data, Code, and other materials

The data and code used in the current paper are available on request from the corresponding author.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Blanca Mena MJ, Alarcón Postigo R, Arnau Gras J, Bono Cabré R, & Bendayan R (2017). Non-normal data: Is ANOVA still a valid option?. Psicothema, 2017, vol. 29, num. 4, p. 552–557. 10.7334/psicothema2016.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha SAJ (2022). Program facilitator effects on engagement with different intervention modalities: A multilevel moderation analysis. [Master’s Thesis, Arizona State University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Database. https://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.2.N.171387. [Google Scholar]

- Britwum K, Catrone R, Smith GD, & Koch DS (2020). A university-based social services parent-training model: A telehealth adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13(3), 532–542. 10.1007/s40617-020-00450-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, & Koppels T (2020). Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child abuse & neglect, 110, 104699. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan GJR, Ballard J, Fatiha N, Song S, & Solheim C (2022). Resilience in the system: COVID-19 and immigrant- and refugee-serving health and human service providers. Families, Systems, & Health, 40(1), 111–119. 10.1037/fsh0000662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Jensen SA, Lowry LS, Cornwell M, Chimklis A, Chan E, Lee D, & Pulgarin B (2016). Engagement in behavioral parent training: Review of the literature and implications for practice. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(3), 204–215. 10.1007/s10567-016-0205-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Wymbs BT, Rajwan E, Wymbs F, & Feirsen N (2017). Characteristics of parents of children with ADHD who never attend, drop out, and complete behavioral parent training. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 950–960. 10.1007/s10826-016-0618-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chacko A, Wymbs BT, Chimiklis A, Wymbs FA, & Pelham WE (2012). Evaluating a comprehensive strategy to improve engagement to group-based behavioral parent training for high-risk families of children with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1351–1362. 10.1007/s10802-012-9666-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi NC, & Demiris G (2015). A systematic review of telehealth tools and interventions to support family caregivers. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 21(1), 37–44. 10.1177/1357633X14562734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Marti CN, Bruce ML, Hegel MT, Wilson NL, & Kunik ME (2014). Six-month postintervention depression and disability outcomes of in-home telehealth problem-solving therapy for depressed, low-income homebound older adults. Depression and Anxiety, 31(8), 653–661. 10.1002/da.22242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Bragg J, & Reay RE (2021). Pivot to telehealth: Narrative reflections on Circle of Security parenting groups during COVID-19. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 42(1), 106–114. 10.1002/anzf.1443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corralejo SM, & Domenech Rodríguez MM (2018). Technology in parenting programs: A systematic review of existing interventions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(9), 2717–2731. 10.1007/s10826-018-1117-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, West SG, & Finch JF (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological methods, 1(1), 16–29. 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Baker S, Dittman CK, Franke N, Hinton S, Love S, Sanders MR, & Turner KM (2021). Predicting positive outcomes and successful completion in an online parenting program for parents of children with disruptive behavior: An integrated data analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 146, 103951. 10.1016/j.brat.2021.103951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Defense (2022). 2022 Demographics: Profile of the Military Community. Retrieved from https://www.militaryonesource.mil/data-research-and-statistics/military-community-demographics/2022-demographics-profile/.

- Finan SJ, Swierzbiolek B, Priest N, Warren N, & Yap M (2018). Parental engagement in preventive parenting programs for child mental health: A systematic review of predictors and strategies to increase engagement. PeerJ, 6, e4676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finan SJ, Warren N, Priest N, Mak JS, & Yap MB (2020). Parent non-engagement in preventive parenting programs for adolescent mental health: Stakeholder views. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 711–724. 10.1007/s10826-019-01627-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty A, Jones A, Seymour M, Savopoulos P, Evans K, “Brien J, … & Giallo R (2021). The parenting skill development and education service: Telehealth support for families at risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child & Family Social Work. 10.1111/cfs.12890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, & Lee S (2024). What works better? 1-year outcomes of an effectiveness trial comparing online, telehealth, and group-based formats of a military parenting program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Advance online Publication. 10.1037/ccp0000882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, & Zamir O (2016). Effects of a military parenting program on parental distress and suicidal ideation: After deployment adaptive parenting tools. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 46, S23–S31. 10.1111/sltb.12255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, DeGarmo DS, & Zamir O (2018). After deployment, adaptive parenting tools: 1-year outcomes of an evidence-based parenting program for military families following deployment. Prevention Science, 19(4), 589–599. 10.1007/s11121-017-0839-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz AH, Pinna KLM, Hanson SK, & Brockberg D (2014). Promoting parenting to support reintegrating military families: After deployment, adaptive parenting tools. Psychological Services, 11(1), 31–40. 10.1037/a0034134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, & Gilreath TD (2007). How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science, 8(3), 206–213. 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haine-Schlagel R, Dickson K, Lind T, Kim JJ, May G, Walsh NE, Lazarevic V, Yeh M, & Crandal B (2022). Parent participation engagement in child mental health prevention programs: A systematic review. Prevention Science. 10.1007/s11121-021-01303-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CM, & Bierman KL (2015). Technology-assisted interventions for parents of young children: Emerging practices, current research, and future directions. Early childhood research quarterly, 33, 21–32. 10.1016/jecresq.2015.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassall R, Rose J, & McDonald J (2005). Parenting stress in mothers of children with an intellectual disability: The effects of parental cognitions in relation to child characteristics and family support. Journal of intellectual disability research, 49(6), 405–418. 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00673.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM (2011). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll B, & Berger NI (2015). Parent engagement with a telehealth-based parent-mediated intervention program for children with autism spectrum disorders: Predictors of program use and parent outcomes. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(10), e4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBraico EJ, Fosco GM, Feinberg ME, Spoth RL, Redmond C, & Bray BC (2021). Predictors of attendance patterns in a universal family-based preventive intervention program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 1–16. 10.1007/s10935-021-00636-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lüdecke D, Ben-Shachar MS, Patil I, Waggoner P, & Makowski D (2021). performance: An R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. Journal of Open Source Software, 6(60). 10.21105/joss.03139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McAloon J, & Armstrong SM (2024). The effects of online behavioral parenting interventions on child outcomes, parenting ability and parent outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-024-00477-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D, Cuijpers P, & Lehman K (2011). Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. Journal of medical Internet research, 13(1), Article e1602. 10.2196/jmir.1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska A, & Sanders M (2006). A review of parental engagement in parenting interventions and strategies to promote it. Journal of Children’s Services, 1(1), 29–40. 10.1108/17466660200600004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mytton J, Ingram J, Manns S, & Thomas J (2014). Facilitators and barriers to engagement in parenting programs: A qualitative systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 41(2), 127–137. 10.1177/1090198113485755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RStudio (2021). rStudio: Integrated Development for R. rStudio, PBC, Boston, MA: URL http://www.rstudio.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement, 1(3), 385–401. 10.1177/01466216770010030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, & Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children—Second Edition. 10.1037/t15079-000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MR, Burke K, Prinz RJ, & Morawska A (2017). Achieving population-level change through a system-contextual approach to supporting competent parenting. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(1), 36–44. 10.1007/s10567-017-0227-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler I, Ingram A, Wolchik S, Tein JY, & Winslow E (2015). Long-term effects of parenting-focused preventive interventions to promote resilience of children and adolescents. Child Development Perspectives, 9(3), 164–171. 10.1111/cdep.12126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simenec T, Banegas J, Parra-Cardona R, & Gewritz AH (2023). Culturally responsive, targeted social media marketing to facilitate engagement with a digital parenting program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32, 1425–1437. 10.1007/s10826-022-02503-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Redmond C, & Shin C (2000). Modeling factors influencing enrollment in family-focused preventive intervention research. Prevention Science, 1, 213–225. 10.1023/A:1026551229118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamm BH (1998). Clinical applications of telehealth in mental health care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 29(6), 536–542. 10.1037/0735-7028.29.6.536 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart RW, Orengo-Aguayo R, Young J, Wallace MM, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, & de Arellano MA (2020). Feasibility and effectiveness of a telehealth service delivery model for treating childhood posttraumatic stress: A community-based, open pilot trial of trauma-focused cognitive–behavioral therapy. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 274–289. 10.1037/int0000225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stormshak EA, Matulis JM, Nash W, & Cheng Y (2021). The Family Check-Up Online: A telehealth model for delivery of parenting skills to high-risk families with opioid use histories. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 2637. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.695967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buuren S, & Groothuis-Oudshoorn K (2011). mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker KA, & Cowley S (2012). An effective programme is not enough: A review of factors associated with poor attendance and engagement with parenting support programmes. Children and Society, 26(2), 138–149. 10.1111/j.1099-0860.2010.00333.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeileis A, Kleiber C, & Jackman S (2008). Regression models for count data in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 27(8), 1–25. 10.18637/jss.v027.i08 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Edirippulige S, Bai X, & Bambling M (2021). Are online mental health interventions for youth effective? A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 27(10), 638–666. 10.1177/1357633x211047285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data and code used in the current paper are available on request from the corresponding author.

Data will be made available on request.