Highlights

-

•

Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) are the gold standard for human experimental studies.

-

•

RCTs demand equipoise and freedom from treatment preference among investigators.

-

•

Neurologic RCTs are costly, time-intensive, and have high participant exclusion rates.

-

•

RCTs use randomization to minimize bias/ confounding and test with probability statistical theory the treatment effects.

-

•

The CONSORT guidelines enhance the quality of RCT reporting.

The gold standard of analytic research in science is the animal experiment. In this framework, the comparison between similar animal in the experiment in the lab aim to have complete control of all the variables that affect the biological processes under study. The exposure is allocated by the researcher without any specific constraint. A classical example may be two rats of the same lot and age that have similar diet but one of the two is deprived of a specific vitamin.

The research with human beings represents a complete different domain. Epidemiology is the research design applied to human beings.

Epidemiological studies are prone to error because they study human populations in natural settings in the real world. and not in laboratory conditions. Similarly to human research in the laboratory, epidemiological inference is based on comparisons. In the hierarchy of research in humans' clinical trial is at the top of the ladder, considered better than observational studies and case series (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The pyramid of epidemiological study-design based on level of evidences.

According to the clinical trial.gov, the NIH site dedicated to clinical trials, the definition of a clinical study is the following: “A clinical study in which participants are assigned to receive one or more interventions (or no intervention) so that researchers can evaluate the effects of the interventions on biomedical or health-related outcomes. The assignments are determined by the study protocol.” [1]

The basic law that rules the experiment among humans (the randomized clinical trial) is similar to the law of animal experiment. According to Bradford Hill, the random allocation of experimental treatment is described: “By the allocation of the patients to the two groups we want to ensure that these two groups are alike except in treatment… this might be done, with reasonably large numbers, by a random division of the patients, no departure from this rule being allowed [2].

The construction of the proper RCT design is therefore based on three main features:

-

1.

Control of Exposure.

-

2.

Random Allocation.

-

3.

The Cause Precedes the Effect.

Feature number 3 is key in establishing causation according to the Bradford-Hill Criteria.

The first paper following this study design was published in the BMJ in 1948 on the use of streptomycin in human tuberculosis [3]. RCT is a very difficult and costly procedure.

We need two conditions before starting to plan an RCT:

-

1.

There is genuine uncertainty of the investigator about the best treatment for the disease of interest (Principle of equipoise);

-

2.

The researcher has to be free of any treatment preferences.

Based on these main foundation, Randomized Clinical trials are research studies

-

•

intended to find better ways to treat or prevent diseases.

-

•

to determine the safety and efficacy of new treatment or medicine used by humans.

-

•

the drugs under trial can be either a new drug has not yet approved by international health authorities or the on-sale drug with improved formula or different use.

The RCT is a long process in which we distinguish four phases from clinical pharmacology to efficacy assessment in small and large numbers, and post-market surveillance:

RCT is a very long (up to 15 years) and expensive process (up to 2–5 billion). Neurologic products take an average10 years to proceed through all of the phases of RCT up to market approval; estimated median (R&D) cost per approved neurologic agent can be close to $1.5 billion [4].

It is important to underline that the human cost of RCT considering the psychological, physical, and financial cost. The number of subjects participating to phase 2 and 3 RCT for neurological therapeutics in the period 2006–2020 was more than 13 thousand (range 7000–55,000) [5]. An additional cost that is not been evaluated is the number of subjects that failed the RCT screen and who did not progress to randomization and those who may have dropped out prior to completion and who were replaced during the RCT.

Similarly to observational cohort studies, the main measures of effect in RCT is the relative risk (RR). The comparison is based on risk in the treatment arm with the risk in the not treatment arm (most cases is the placebo arm). In the RCT the random assignment of the treatment is critical:

-

1.

Reduces selection bias at entry balancing both known and unknown prognostic factors.

-

2.

Permits the use of probability theory to express the likelihood that any difference between intervention groups may be due to chance.

-

3.

Facilitate the blinding of the identity of treatment to investigators, participants, evaluators.

One of the most critical goals is the improvement of the quality of RCT report in medical journals. The guidelines were established by the Consort statement and were established for each section of a RCT report: enrolment, intervention allocation, follow-up, and analysis) [6].

In summary RCT generally offer stronger evidential support than observational studies.

In the five-grade pyramid that scores study design, on the top of the pyramid there is at least one well randomized properly conducted RCT [7] (Fig. 1).

A large, randomized experiment is the only study design that can guarantee that control and intervention subjects are similar in all the known and unknown attributes that influence outcomes.

The RCT is based on a thorough selection process. The subjects that are selected are a minority of a much larger group that is at the entry. This selection process is based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria tend to exclude subjects that could experience side effects due to the drug. Inclusion criteria are based:

-

1.

On definition of risk of the outcome of interest.

-

2.

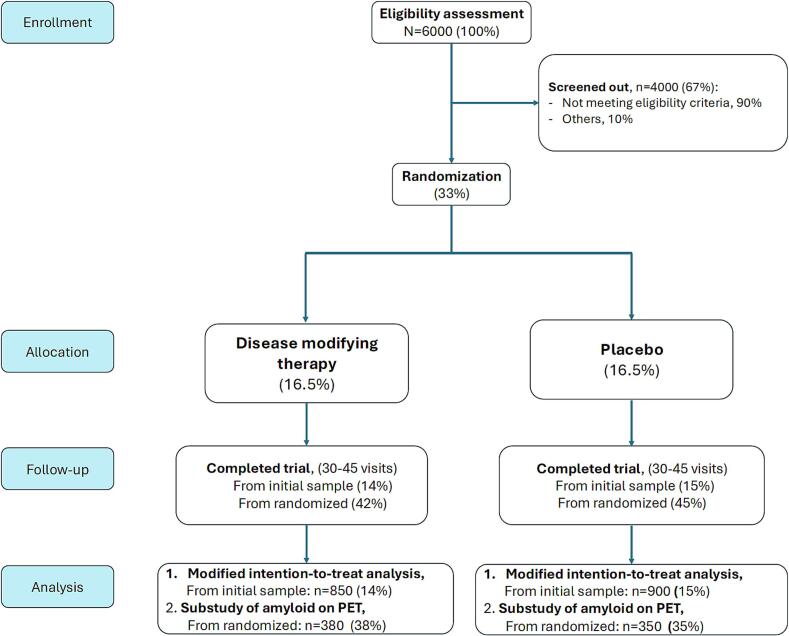

On the biological definition of disease. An example of this diagnostic restriction are the recent trials on disease modifying therapy (DMT) in Alzheimer's disease. The selection process determines that only 15 % of the patient at entry go into intention to treat analyses (Fig. 2). This is confirmed when this model is applied in the real world of a center treating patients with Alzheimer ‘disease [8].

Fig. 2.

A model of the recruitment process of randomized clinical trial of disease modifying therapies in Alzheimer's disease (AD) (from averaging real DMT published studies in AD).

In conclusion, the RCT more than any other methodology can have a decisive and changing impact on patient care and health [9].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Giancarlo Logroscino: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

To Dr. Stefano Giannoni and Marco Musio for the preparation of the manuscript and the figures.

References

- 1.https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 2.Hill A.B. Medical ethics and controlled trials. Br. Med. J. 1963;1(5337):1043–1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5337.1043. PMID: 13954493; PMCID: PMC2122975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.STREPTOMYCIN treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Br. Med. J. 1948;2(4582):769–782. (PMID: 18890300; PMCID: PMC2091872) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reoma L.B., Karp B.I. The human cost: patient contribution to clinical trials in neurology. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(5):1503–1506. doi: 10.1007/s13311-022-01292-x. Epub 2022 Sep 9. PMID: 36083396; PMCID: PMC9606162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacPherson A., Gumnit E., Ouimet C., Hutchinson N., Kieburtz K., Pearson T.S., Kimmelman J. Quantifying patient Investment in Novel Neurological Drug Development. Neurotherapeutics. 2022;19(5):1507–1513. doi: 10.1007/s13311-022-01259-y. (Epub 2022 Jun 28. PMID: 35764764; PMCID: PMC9606150) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D., Hopewell S., Schulz K.F., Montori V., Gøtzsche P.C., Devereaux P.J., Elbourne D., Egger M., Altman D.G. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;(340) doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. PMID: 20332511; PMCID: PMC2844943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Concato J., Shah N., Horwitz R.I. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000;342(25):1887–1892. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422507. PMID: 10861325; PMCID: PMC1557642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logroscino G., Urso D., Gnoni V., Giugno A., Vilella D., Castri A., Barone R., Nigro S., Zecca C., De Blasi R., Introna A. Mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease eligibility for disease modification therapies in a tertiary Centre for cognitive disorders: a simultaneous real-word study on aducanumab and lecanemab. Eur. J. Neurol. 2025;32(1) doi: 10.1111/ene.16534. (Epub 2024 Nov 5. PMID: 39498901) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Begg C., Cho M., Eastwood S., Horton R., Moher D., Olkin I., Pitkin R., Rennie D., Schulz K.F., Simel D., Stroup D.F. Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA. 1996;276(8):637–639. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.8.637. (PMID: 8773637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]