Abstract

Microbiome gained attention as a cofactor in cancers originating from epithelial tissues. High-risk (hr)HPV infection causes oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma but only in a fraction of hrHPV+ individuals, suggesting that other factors play a role in cancer development. We investigated oral microbiome in cancer-free subjects harboring hrHPV oral infection (n = 33) and matched HPV− controls (n = 30). DNA purified from oral rinse-and-gargles of HIV-infected (HIV+) and HIV-uninfected (HIV−) individuals were used for 16S rRNA gene V3–V4 region amplification and sequencing. Analysis of differential microbial abundance and differential pathway abundance was performed, separately for HIV+ and HIV− individuals. Significant differences in alpha (Chao-1 and Shannon indices) and beta diversity (unweighted UniFrac distance) were observed between hrHPV+ and HPV-negative subjects, but only for the HIV− individuals. Infection by hrHPVs was associated with significant changes in the abundance of Saccharibacteria in HIV+ and Gracilibacteria in HIV− subjects. At the genus level, the greatest change in HIV+ individuals was observed for Bulleidia, which was significantly enriched in hrHPV+ subjects. In HIV− individuals, those hrHPV+ showed a significant enrichment of Parvimonas and depletion of Alloscardovia. Our data suggest a possible interplay between hrHPV infection and oral microbiome, which may vary with the HIV status.

Subject terms: Microbiome, Pathogens

Introduction

In the last 10 years, the role of the human microbiome has gained attention as a predicting biomarker of infections as well as an important cofactor linked to several types of cancer, including squamous cell carcinomas of mucosal and cutaneous body sites1–3. Human Papillomaviruses (HPVs) have a strict tropism for the squamous stratified epithelium. They typically infect the skin (cutaneous infections) and mucosal tissues (ano-genital and oral infections). For the most part, mucosal HPV infections are cleared by the immune system, and no clinically relevant lesions are detectable. In a minority of cases, however, the development of ano-genital and head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (mainly oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, OPC) may occur as a consequence of persistent infections by HPV genotypes with oncogenic potential, i.e., high-risk (hr) HPVs4. Oral HPV infections have become increasingly interesting because of the rising incidence of OPC in several countries, along with the increase in the proportion of HPV-driven OPCs5,6. Prevalence of oral HPV infection is around 5% in the general population7, whereas a three- to five-fold higher prevalence is observed in individuals with risky sexual behavior, such as men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly if living with HIV8. The prevalence of hrHPVs is also higher in these subjects compared to the general population (9–16% vs. 4%)7,8.

Although a persistent infection by hrHPVs is the primary cause of cancer development, only a small fraction of HPV-infected individuals will ultimately develop malignant lesions, suggesting that other factors, both host and virus-related, play a role in the progression from infection to cancer. Several lines of evidence exist about an interplay between vaginal microbiome, HPV infection and cervical squamous cell carcinoma development9–12. Interestingly, a higher diversity of the vaginal microbial community seems to be associated with persistent hrHPV infections in HIV− but not HIV+ women, suggesting that HIV status may have an impact on the microbiome and its interplay with HPV13.

The oral microbiome in relation to HPV infection has been characterized in patients with head and neck cancer14,15. Recently, a large cross-sectional study comparing the oral microbiome of cancer-free individuals with and without oral HPV infection found similar alpha-diversity yet different beta-diversity16. However, the study did not focus on hrHPVs, and the interaction between oral hrHPV infection and microbiome still remains scarcely investigated. Therefore, it is pivotal to gather new data in this regard.

Here, we aimed to investigate the association among oral microbiome, hrHPV infection and HIV, evaluating the composition of oral microbiome in cancer-free HIV+ and HIV− men enrolled in a longitudinal study and harboring prevalent oral infection by hrHPVs.

Results

Study population

The study included 63 individuals, of whom 22 were men living with HIV (34.9%). Twelve of these subjects harboured hrHPVs, while the remaining 10 represented the HPV-negative control group. Of the 41 HIV− individuals, 21 had an oral infection by hrHPVs, and the other 20 subjects represented the respective controls. The characteristics of the four study groups stratified according to the HIV status and oral hrHPV infection are shown in Table 1. HIV+/hrHPV+ subjects did not differ significantly from the HIV+/HPV-negative controls in terms of age, education, income, sexual behaviour, STI history, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and oral hygiene. The two groups showed no significant differences regarding cART (all subjects of both groups were under therapy), cART median duration (4.5 vs. 8.1 years, p = 0.28), nadir CD4 + (300 vs. 310, p = 0.95) and current CD4+ T-cell median counts (678 vs. 759, p = 0.58).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic, behavioral and lifestyle characteristics of the study groups.

| Variable | HIV+ individuals, N = 22 | p-value | HIV− individuals, N = 41 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hrHPV+, n = 12 | HPV−, n = 10 | hrHPV+, n = 21 | HPV−, n = 20 | |||

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | |||||

| Age (years) | 45 (36–56) | 45 (37–51) | 0.84 | 44 (38–49) | 45 (43–47) | 0.82 |

| Age at first sex with a man (years) | 20 (18–23) | 18 (17–19) | 0.07 | 23 (18–27) | 22 (20–25) | 0.82 |

| N. lifetime partners, any sex | 300 (85–510) | 75 (25–180) | 0.15 | 95 (34–163) | 100 (45–375) | 0.53 |

| N. recent partners, any sex | 2 (2–9) | 2 (1–2) | 0.08 | 6 (3–20) | 7 (4–13) | 0.73 |

| N. lifetime partners, oral sex | 200 (58–350) | 50 (15–80) | 0.09 | 40 (20–96) | 33 (13–175) | 0.85 |

| N. recent partners, oral sex | 2 (1–8) | 1 (1–2) | 0.06 | 3 (2–6) | 5 (2–11) | 0.66 |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graduate education | 5 (41.7) | 4 (40.0) | 0.94 | 12 (57.1) | 11 (55.0) | 0.89 |

| Income > 12,000 €/year | 8 (66.7) | 6 (60.0) | 0.75 | 15 (71.4) | 14 (70.0) | 0.92 |

| Smoking status | 0.78 | 0.80 | ||||

| Current | 7 (58.3) | 7 (70.0) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (25.0) | ||

| Former | 1 (8.3) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (10.0) | ||

| Never | 4 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 15 (71.4) | 13 (65.0) | ||

| Alcohol consumption | 0.19 | 0.12 | ||||

| No | 4 (33.3) | 6 (60.0) | 10 (47.6) | 8 (40.0) | ||

| Light | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (14.3) | 8 (40.0) | ||

| Moderate | 5 (41.7) | 4 (40.0) | 8 (38.1) | 3 (15.0) | ||

| Heavy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.0) | ||

| Oral health/hygiene | 0.24 | 0.78 | ||||

| Good/very good | 3 (25.0) | 6 (60.0) | 13 (61.9) | 11 (55.0) | ||

| Fair/poor/very poor | 9 (75.0) | 4 (40.0) | 8 (38.1) | 9 (45.0) | ||

| STI history | 0.75 | 0.51 | ||||

| No | 3 (25.0) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (19.0) | 6 (30.0) | ||

| Ano-genital warts | 3 (25.0) | 4 (40.0) | 11 (52.4) | 7 (35.0) | ||

| Othersa | 6 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (28.6) | 7 (35.0) | ||

STI sexually transmitted infections.

aGenital herpes, syphilis, gonorrhea (any site), diagnosed at least 6 months prior to enrollment.

HIV−/hrHPV+ and the respective controls showed no significant differences for any of the socio-demographic and behavioural variables.

hrHPVs genotypes in oral infections

Among the 12 HIV+/hrHPV+ subjects, the following hrHPVs were detected: HPV16 (3, 25.0%), HPV18 (3, 25.0%), HPV33 (1, 8.3%), HPV39 (2, 16.6%), HPV45 (1, 8.3%), HPV51 (2, 16.6%), HPV59 (2, 16.6%), HPV66 (2, 16.6%), and HPV68 (2, 16.6%). Among the 21 HIV−/hrHPV+ individuals, the following types were found: HPV16 (8, 38.1%), HPV18 (1, 4.8%), HPV33 (2, 9.5%), HPV35 (1, 4.8%), HPV45 (3, 14.3%), HPV56 (4, 19.0%), HPV58 (1, 4.8%), HPV59 (1, 4.8%), HPV66 (3, 14.3%), and HPV68 (2, 9.5%).

Alpha and beta diversity

Alpha diversity indexes are shown in Fig. 1. Among HIV+ subjects, alpha diversity appeared to be lower in hrHPV+ individuals than in the respective controls, but no significant differences emerged between the two groups for any of the metrics used. Among HIV− subjects, Chao1 index was significantly higher in hrHPV+ individuals (p = 0.033). Findings were similar for the Shannon index (p = 0.055), whereas there were no significant differences using the other metrics.

Fig. 1.

Alpha diversity of bacterial taxa in oral samples of high-risk HPV-positive (hrHPV+) and HPV-negative individuals (HPV−), grouped by HIV status. Shannon, Faith, Pielou Evenness and Chao1 metrics for each study group are shown.

Using Jaccard, weighted and unweighed UniFrac beta diversity metrics, no statistically significant differences were observed between HIV+/hrHPV+ and HIV+/HPV− groups (Fig. 2a). There were no significant differences in beta diversity between the HIV− groups using Jaccard and weighted UniFrac distances (Fig. 2b). In contrast, a significant difference was found between hrHPV+ and HPV− participants using unweighted UniFrac (p = 0.003). Unweighted PCoA analysis showed that samples from the HPV− individuals clustered very closely.

Fig. 2.

Beta diversity analysis of microbial communities in oral samples of high-risk HPV-positive (hrHPV+) and HPV-negative individuals (HPV−) using Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Jaccard dissimilarity, unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances. Plots are shown separately for (a) HIV-infected (HIV+) and (b) HIV-uninfected individuals (HIV−). Each circle represents a participant. The 95% confidence ellipse for each group is also shown.

Differential abundance analysis

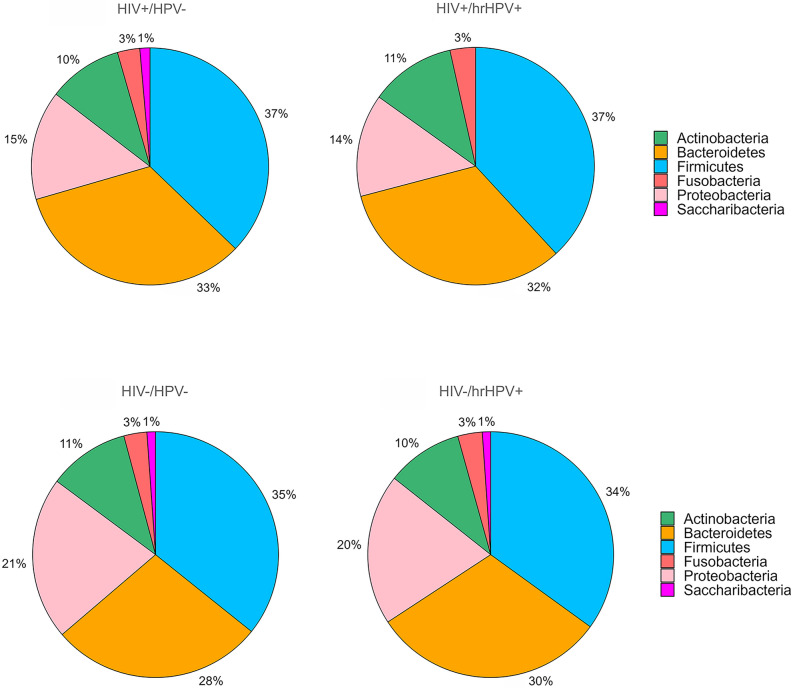

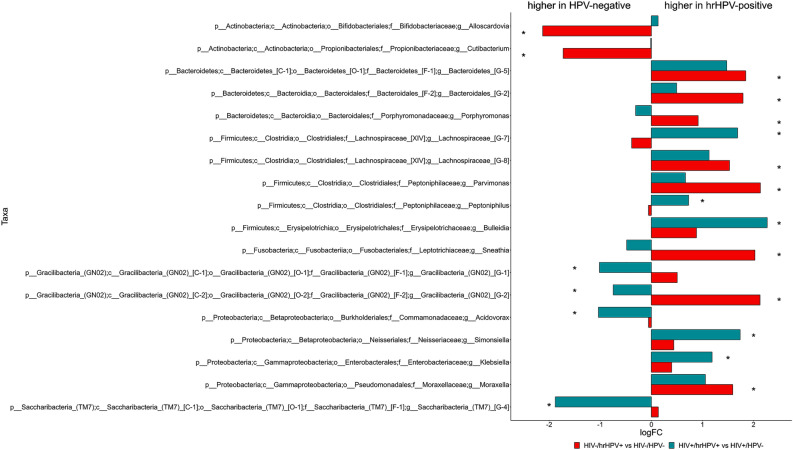

The number of phyla, genera and species identified for each of the four study groups is shown in Table 2. The relative abundance of the bacterial phyla with an abundance > 1% is shown in Fig. 3, whereas phyla with an abundance < 1% are shown in Suppl. Fig. 1. In all four study groups, oral microbiota was dominated by Firmicutes (34–37%), followed in decreasing order of relative abundance by Bacteroidetes (28–33%), Proteobacteria (14–21%), Actinobacteria (10–11%), and Fusobacteria (3%). We next searched for specific oral microbiome features that were differentially abundant by oral hrHPV infection. This analysis lead to the identification of one phylum, nine genera and 38 species for HIV+ subjects. Saccharibacteria (TM7) were significantly less abundant in those harbouring hrHPVs than in the controls (0.79% vs. 1.36%, p = 0.033). Five genera significantly increased in those hrHPV+ (Lachnospiaraceae, Bulleidia, Peptoniphilus, Simonsiella, Klebsiella), whereas four were significantly overabundant in the HPV− individuals (Fig. 4). Among the species that showed a differential abundance (mainly belonging to Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes), 18 were overabundant in hrHPV+ subjects, the remaining 20 being overabundant in the respective controls (Suppl. Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Number of phyla, genera and species identified for each of the four study groups.

| Study group | Phylum n |

Genus n |

Species n |

|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+/hrHPV+ | 9 | 117 | 262 |

| HIV+/HPV− | 10 | 113 | 246 |

| HIV−/hrHPV+ | 10 | 124 | 297 |

| HIV−/HPV− | 9 | 118 | 275 |

HIV+ HIV-infected, HIV− HIV-uninfected, hrHPV+ high-risk HPV-positive, HPV− HPV-negative.

Fig. 3.

Taxonomic composition of the oral microbiome with the relative abundance of the most abundant taxa (abundance > 1%) at the phylum level. HIV+ HIV-infected subjects, HIV− HIV-uninfected subjects, hrHPV+ high-risk HPV-positive, HPV− HPV-negative.

Fig. 4.

Differential abundance of oral bacterial taxa at the genus level. Taxa with a significant differential abundance between high-risk HPV-positive (hrHPV+) and HPV-negative subjects (HPV−) are indicated with an asterisk (p < 0.05). HIV+ HIV-infected individuals (teal bars), HIV− HIV-uninfected individuals (red bars), p phylum, c class, o order, f family, g genus, logFC log2 Fold Change.

One phylum, 10 genera and 25 species were differentially abundant between HIV−/hrHPV+ and HPV− subjects. Gracilibacteria were only found among those with oral hrHPV infection (0.09%). Aside from two genera, namely Alloscardovia and Cutibacterium, which were significantly reduced in hrHPV+ individuals, eight genera were significantly increased in the presence of hrHPV infection compared to the HPV− controls (Fig. 4). Thirteen species were significantly overabundant in hrHPV+ subjects (mainly Bacteroidetes), whereas 12 were overabundant in the respective controls (Suppl. Fig. 2).

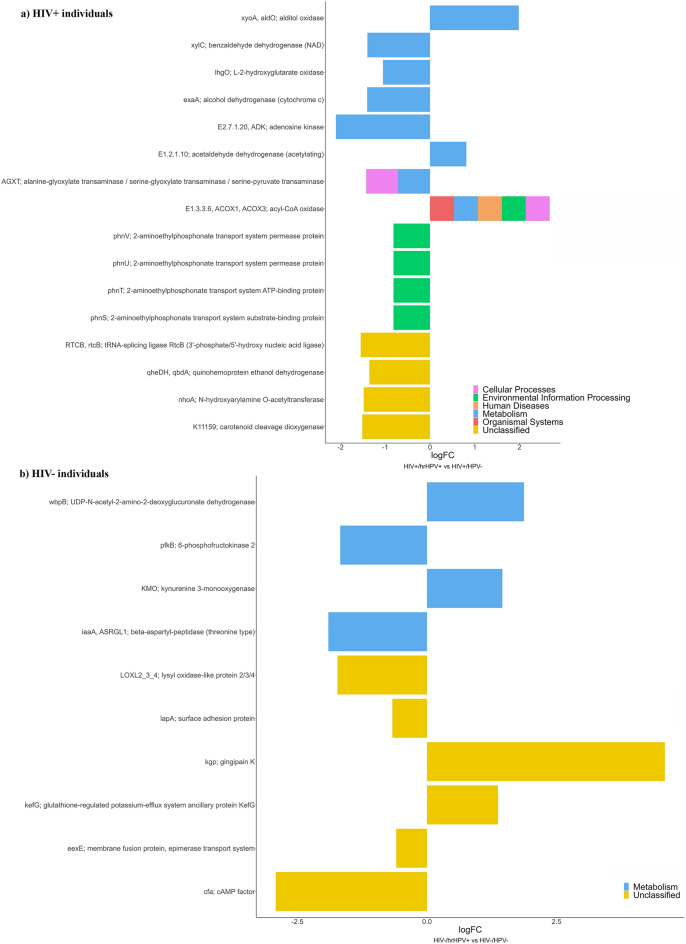

Differential pathway abundance

Finally, PICRUSt2 was used to predict the functional profiles of the oral microbiome based on the 16S rRNA sequencing data across the study groups. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Orthology (KO) pathways that demonstrated statistically significant differences between the study groups are shown in Fig. 5. In HIV+ subjects, 98 KOs showed a significantly different abundance with a p < 0.01 (Suppl. Fig. 3) and 16 KOs with a p < 0.005 (Fig. 5a). The analysis revealed that cellular transport, translation, nucleotide and amino acid metabolism KEGG pathway categories had a significantly increased abundance in HPV− subjects, while carbohydrate metabolism categories mainly showed an increased abundance in hrHPV+ subjects. In HIV− subjects, there were 10 differentially abundant KOs with a p < 0.01, four of which increased in abundance in those with hrHPV oral infection (Fig. 5b). KO with the highest fold change was gingipain K proteinase (kgp), which was enriched more than 10-times in case of hrHPV infection.

Fig. 5.

Differential pathway abundance predicted in terms of KEGG Orthology (KO) abundances. High-risk HPV-positive (hrHPV+) and HPV-negative individuals (HPV−) were compared. KO abundances with a p < 0.005 and a p < 0.01 are shown for (a) HIV-infected (HIV+) and (b) HIV-uninfected individuals (HIV−), respectively. LogFC log2 Fold Change.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed the oral microbiome of HIV+ and HIV− individuals, seeking possible variations in its composition and diversity in relation to hrHPV infection. Among HIV+ participants, no significant changes in microbial diversity (alpha and beta) were observed between subjects with hrHPV infection and those without HPV, suggesting that the presence of hrHPVs is not associated with changes in oral microbiome richness, diversity and composition in the context of HIV infection. In contrast, when analysing HIV− individuals, hrHPV+ samples displayed a significantly higher richness (Chao1 index) than HPV- samples, an observation that is in line with previous findings by Tuominen et al.17. The Shannon diversity index was also higher in hrHPV+ subjects, but with borderline significance. These results differ from those of Zhang et al., although their analysis concerned any HPV infection16. Nonetheless, in line with the findings of Zhang et al., beta diversity was significantly different between hrHPV+ and HPV− subjects. Significance was limited to unweighted UniFrac, whereas weighted UniFrac did not differ significantly, suggesting that the observed difference depends on phylogeny and presence/absence but not on different abundance. We can also infer that the differences between hrHPV+ and HPV− subjects found in the unweighted UniFrac plot are probably due to small differences in the composition of their microbial communities.

HIV and oral HPV status did not affect oral microbiome composition in terms of the most abundant phyla, which substantially overlap with those found in other studies on salivary microbiome18–21. They match the most abundant phyla of the core oral microbiome, which is dominated by members of Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Bacteroidetes22,23. These five phyla in our study were the same and in the same order of abundance as the investigation by Zhang et al.16. Although some variations among the different studies are observed according to the population and methodology, these findings confirm that the oral microbiome is relatively stable23. Infection by hrHPVs was associated with significant changes in the less abundant phyla. Those with hrHPV infection showed a significant decrease in Saccharibacteria and a significant increase in Gracilibacteria among HIV+ and HIV− subjects, respectively. Saccharibacteria (formerly known as TM7) are ultra-small bacteria belonging to the Candidate Phyla Radiation group (CPR) and live as epibionts on the surfaces of their host bacteria24. They are constituents of the oral microbiome of disease-free individuals18 and are enriched in oral samples of HIV-infected individuals compared to HIV-uninfected controls25,26. Their increased abundance has been correlated with dysbiotic microbiomes during periodontitis and other inflammatory mucosal diseases27. However, a recent study that investigated their causal role in gingival inflammation suggested that they may not cause inflammatory processes but can influence the physiology and pathogenicity of their host bacteria28. Our data with respect to TM7 and HPV infection showed an opposite trend compared to a previous study17, underlining that further studies are necessary to understand TM7 role in the oral cavity, particularly in case of viral infections.

We found that another member of the CPR family, Gracilibacteria (aka GN02), was modulated in HIV− subjects. GN02 is commonly found in the oral cavity and has been observed in both patients with dental caries and healthy individuals29,30. Although GN02 is still understudied, a recent investigation observed that increased salivary counts of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) upon spaceflight were positively associated with Gracilibacteria31. These findings suggest that particular conditions, such as spaceflight, could activate microbes that promote viral replication. These data are consistent with our results since we observed an increase in GN02 in those with hrHPV infection.

Numerous genera were differentially abundant according to the oral HPV infection. Among the nine genera that showed a differential abundance in HIV+ individuals, the highest fold change was observed for Bulleidia, which was enriched in hrHPV+ subjects, as reflected by the increase in B. extructa, which is the only species included in this genus and has been associated with necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis precisely in HIV+ individuals32. Recent studies showed a greater abundance of Bulleidia in oral samples of subjects reporting gum bleeding33 and in those affected by oral lichen planus (OLP)34. Patients with inflammatory bowel disease also showed a higher abundance of this genus35, confirming that oral dysbiosis plays a key role in triggering and exacerbating several pathologies. The abundance of four other genera was significantly increased in the presence of hrHPVs: Lachnospiraceae G-7, Peptoniphilus, Simonsiella, and Klebsiella. Peptoniphilus spp. are Gram-positive anaerobic commensals that live in the oral cavity, gastrointestinal, genitourinary and upper respiratory tracts. These bacteria can trigger the release of the neutrophil-derived product calprotectin, which promotes an inflammatory state36. A higher abundance of Peptoniphilus has been found in colorectal and anal cancer37,38, and, notably, in the vaginal microbiome of hrHPV-positive women39. Simonsiella bacteria have been isolated from OLP lesions40,41, and are significantly enriched in OLP patients compared to healthy subjects34. However, they do not seem to have a causative role in the onset of this disease42. Klebsiella is among the oral pathobionts that are expanded in periodontitis. Upon migration to the gut, it can promote chronic inflammation43. Klebsiella spp., which are well known for their potential to acquire virulence and antibiotic resistance, have been isolated from the saliva of patients with gastrointestinal inflammatory and neoplastic diseases. Acidovorax is among the four genera that significantly decreased in relative abundance in HIV+ subjects with hrHPV infection. Conversely, it has been found to be increased in women with genital HPV infection44,45, suggesting that the way HPV and Acidovorax “interact” in terms of abundance varies according to the HPV infection site. Interestingly, some spp. of this genus have been shown to be associated with inflammatory mediators up-regulated in rheumatoid arthritis patients with periodontitis46.

Among HIV− subjects, Parvimonas and Alloscardovia showed the most relevant changes when comparing individuals with and without oral HPV. Those infected with hrHPVs had a higher abundance of Parvimonas. Notably, this genus is significantly enriched in oral cancer patients47. In the case of hrHPV infection, there was also a significant enrichment of Bacteroidetes [G-5], Bacteroidales [G-2], and Moraxella, genera associated with gum bleeding, periodontal disease or oral squamous cell carcinoma33,48–51. Interestingly, the abundance of Bacteroidales [G-2] and Sneathia, another genus that showed an increased relative abundance in HIV− individuals with oral hrHPVs, was found to be increased in head and neck cancer patients developing oral mucositis during radiotherapy52. Sneathia also showed a positive association with cervical HPV infection44,45, in line with our results.

Only two genera, Cutibacterium and Alloscardovia, showed a significantly lower abundance in HIV- individuals with hrHPVs. Indeed, A. omnicolens, the only species of the Alloscardovia genus, showed a notable reduction in HIV− subjects harbouring hrHPVs. Cutibacterium spp. are skin-associated taxa that do not represent typical oral inhabitants, although they may cause endodontic infections53. The significance of the decreases in the relative abundance of these genera remains unclear.

Several species involved in periodontal disease and inflammation were found to be increased in those with hrHPV infection. Porphyromonas gingivalis, a central player in periodontitis54,55, was enriched in hrHPV+ subjects, irrespective of HIV status, although abundance significantly differed only in HIV- participants. P. gingivalis is capable of promoting dysbiosis and inflammation both at the oral and intestinal sites55,56. It shows a close correlation with oral squamous cell carcinoma49 and can indeed promote oral carcinogenesis57–59. HIV+/hrHPV+ subjects were also enriched in the putative periodontal pathogen Fretibaterium fastidiosum, and in Prevotella oralis, a species associated with periodontal inflammation60. HIV status per se has already been shown to be associated with oral dysbiosis and enrichment in species involved in biofilm formation, caries and periodontal disease21,26,61,62. In line with our results, Zhang et al. found a positive association of Prevotellaceae with oral HPV16. Genital HPV infection also increased the relative abundance of Prevotella in vaginal samples44.

We then examined the differential abundance of microbial functional pathways, and we found that the large majority of KOs did not show any significant difference by hrHPV status. This confirms that KEGG pathways are quite stable among different microbial communities. Nonetheless, the abundance of several KOs significantly changed with hrHPV infection, both in HIV+ and HIV− individuals. Interestingly, in the former group of subjects, the only three KOs that showed significant enrichment in those with hrHPV infection were all involved in carbohydrate metabolism. More commonly, KOs were significantly less abundant in the presence of hrHPVs, e.g., the subunits of an ABC transport system for 2-aminoethylphosphonate. Bacteria use phosphonates as a source of carbon, phosphorous and nitrogen. Pathways involved in xenobiotics biodegradation and metabolism (e.g., xylene, toluene, aminobenzoate) were also less abundant in case of hrHPV infection, in line with previous findings16, which suggests a reduced capacity of degrading xenobiotics in HPV-infected subjects. Occupational oral exposure to chemicals containing organic compounds has been shown to increase genetic damage in oral epithelial cells63,64. These data suggest that hrHPVs may promote oral carcinogenesis by reducing the microbial capability of degrading genotoxic compounds.

A diverse impact of hrHPV infection on functional pathways of the oral microbiome was observed in HIV- subjects. All the differentially abundant pathways were within the overall category of “metabolism” (amino acid metabolism, metabolism of cofactors and vitamins, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites). The most relevant change concerned gingipain K proteinase, with a significant increase found in the case of hrHPV infection. Gingipain K is a virulence factor of P. gingivalis that increases P. gingivalis invasion and pathogenicity in periodontal disease65,66. The findings regarding gingipain are in line with the significant enrichment of P. gingivalis in those with hrHPVs. UDP-N-acetyl-2-amino-2-deoxyglucuronate dehydrogenase was also significantly enriched in case of hrHPV infection. Interestingly, this is involved in amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism but also in O-Antigen nucleotide sugar biosynthesis. O-Ag is the outer and immunogenic domain of lipopolysaccharide. The expression of genes involved in LPS synthesis increases in the periodontitis microbiome67.

The depleted pathways in HIV−/hrHPV+ subjects mainly have a role in the energy metabolism and biosynthesis of amino acids and secondary metabolites. The most relevant decrease was found in the differential abundance of cAMP factor, an extracellular protein that functions as a pore-forming bacterial toxin participating in hemolysis. For instance, cAMP is a virulence factor secreted by C. acnes68, which can trigger inflammation in keratinocytes and macrophages. The decreased abundance of functions related to cAMP factor is in line with the fact that C. acnes was under-represented in HIV−/hrHPV+ subjects, but the significance of these findings needs to be clarified.

The strengths of this study are: (i) including both HIV+ and HIV− subjects; (ii) selecting male participants, thus avoiding sex effects and focusing on the population mainly affected by HPV-driven OPC; (iii) using strict criteria to select HPV-negative subjects of the control groups; and (iv) matching hrHPV+ and HPV− subjects as much as possible on variables that may affect the oral microbiome (age, oral health, lifestyle and sexual habits) to minimize the effect of possible confounders and to highlight the true contribution of hrHPV infection. The study limitations include: (i) the cross-sectional design, which did not allow us to understand whether microbial alterations are driven by hrHPV infection or precede it, thus favouring HPV acquisition; (ii) all HIV+ subjects were on cART and with well-controlled viraemia; thus, our results are not generalizable to all people living with HIV; and (iii) our study only included MSM, who have diverse microbial communities compared to other subjects, most likely as a result of their sexual behaviour69,70; (iv) the HIV+ study groups showed a certain degree of difference in terms of lifetime number of oral sex partners, and since oral sexual activity modifies both the risk for hrHPV acquisition and the oral microbiome21, our results should be interpreted with caution due to the underlying heterogeneity of these groups; (v) unmeasured confounders should be considered when interpreting our findings, since there are other behaviours/sociodemographic determinants known to affect the oral microbiome that were not measured in the present study (such as dietary habits)71.

In conclusion, hrHPV infection is associated with an altered oral microbiome in terms of richness and diversity, but only in HIV− subjects. The relative abundance of several microbial groups at the phylum, genus and species level significantly changed with hrHPV infection, regardless of the HIV status. Several taxa associated with oral diseases and/or inflammation were significantly increased in hrHPV+ subjects. In the HIV− individuals, hrHPVs seem to be associated with the expansion of harmful taxa while decreasing beneficial ones (such as Lb. fermentum). In the HIV+ counterparts, our findings suggest that hrHPV infection further exacerbates the oral dysbiosis associated with HIV. This study represents a first step towards the understanding of the complex interactions between oral HPV infection and microbioma. Studies with well-matched groups are necessary to validate and expand upon these preliminary findings and to elucidate whether and how, in the context of hrHPV oral infection, alterations of the microbiome affect the outcome of the infection in terms of persistence and development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Methods

Study population

Study subjects were selected among participants in the OHMAR (Oral/Oropharyngeal HPV in Men At Risk) study, a monocentric longitudinal study carried out on HIV+ and HIV− MSM attending the Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI)/HIV Unit of the San Gallicano Dermatological Institute IRCCS (Rome, Italy) between November 2014 and February 201872,73. Enrolment criteria for the OHMAR study have been previously described72. Briefly, they were as follows: (1) being ≥ 18 year-old MSM, (2) no previous HPV vaccination, (3) no history of head and neck cancer, (4) no clinically visible lesions suspicious for head and neck cancer, as evaluated during a thorough examination conducted at enrolment by expert otolaryngologists.

Based on the HPV test results on oral rinse-and-gargles (see below), the following individuals were retrospectively selected: (1) hrHPV+ subjects, i.e., those who harboured a prevalent oral infection by at least one of the following genotypes: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68; and (2) HPV− subjects (control subjects), selected among participants who were HPV-negative (i.e., negative for all the 37 genotypes detectable by the Linear Array HPV genotyping test as described in the OHMAR study72) at least for three consecutive visits scheduled every 6 months (i.e., for at least one year from enrolment). The hrHPV+ individuals included in the present study represented all the subjects harbouring a prevalent hrHPV oral infection among the 310 participants of the OHMAR study74. Once the characteristics of the hrHPV+ MSM were evaluated, the HPV− control subjects were matched with them on age, smoking status, alcohol consumption, oral hygiene (as ascertained by the otolaryngologists during a full examination of the oral cavity)73, and HIV status. For HIV+ subjects, cases and controls were also matched on cART therapy.

All the procedures on human subjects were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki-Version 2013.

Oral rinse-and-gargles

Oral rinse-and-gargles were collected using 15 ml of Listerine mouthwash ® (McNeil Consumer Healthcare division of Johnson & Johnson, Pomezia, Italy). Participants alternatively rinsed and gargled for a total of 30 s. Samples were centrifuged (10 min at 3000×g, 4 °C) to remove the mouthwash and the pellet was washed twice with PreservCyt solution (Hologic, Pomezia, Italy). Finally, the cell pellet was resuspended in 2 ml of PreservCyt, and 250 μl aliquots were stored at − 80 °C until nucleic acid extraction.

Nucleic acid extraction

Total nucleic acids were purified using the Amplilute Liquid Media Extraction Kit (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Milan, Italy), based on the employment of QIAamp® MinElute® Columns, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The elution step was performed using 120 μl of the AVE elution buffer provided within the kit. A 50 μl aliquot was used for HPV-DNA amplification. The remaining extracts were stored at − 80 °C for microbial analysis.

HPV amplification, detection and genotyping

The Linear Array HPV Genotyping test (Roche Diagnostics, Milan, Italy) was employed, as previously described72. This assay is based on HPV-DNA amplification and detection by hybridization with strip-immobilized probes for 37 HPV genotypes, including those classified as hrHPVs.

Targeted library preparation and sequencing

Microbiome analysis was performed by ZymoBIOMICS Targeted Sequencing Service (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene-targeted sequencing was performed using the Quick-16S™ NGS Library Prep Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). The bacterial 16S primers to amplify the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene have been custom-designed by Zymo Research to provide the best coverage of the 16S gene while maintaining high sensitivity. PCR reactions for library preparation were performed in real-time PCR machines to control cycles and, therefore, limit PCR chimera formation. The final PCR products were quantified with qPCR fluorescence readings and pooled together based on equal molarity. The final pooled library was cleaned with the Select-a-Size DNA Clean & Concentrator™ (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA), then quantified with TapeStation® (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and Qubit® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, WA). The ZymoBIOMICS Microbial Community Standard (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) was used as a positive control for each targeted library preparation. Negative controls (i.e., blank library preparation control) were included to assess the level of bioburden carried by the wet-lab process. The final library was sequenced on Illumina® MiSeq™ with a v3 reagent kit (600 cycles). The sequencing was performed with 10% PhiX spike-in.

Bioinformatics and statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were computed for the variables of interest to provide summarized descriptions of the study groups. Mann–Whitney test was used for comparisons between median values. The chi-square test was used to compare proportions.

Raw FASTQ were trimmed using trim-galore75 to eliminate sequencing adapters and to erase poor-quality reads. QIIME2 pipeline (v. qiime2-2022.11)76 was used to process the trimmed FASTQ files. Paired-end sequences were first imported, and then quality-filtering was performed with the DADA2 denoise method cutting to a quality score of 30. Alpha (Shannon entropy, Chao1, Eveness, Faith) and beta diversity (Jaccard, Weighted-unifrac, Unweighted-unifrac, Bray–Curtis) were estimated. The following groups were compared: (1) HIV+/hrHPV+ vs. HIV+/HPV− individuals; (2) HIV−/hrHPV+ vs. HIV−/HPV− individuals. Differences between groups in terms of alpha-diversity were calculated using Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon tests. The significance for beta-diversity was calculated with a PERMANOVA analysis. Taxonomy was assigned to the amplicon sequence variant (ASV) using the expanded Human Oral Microbiome Database (eHOMD) (v.15.22)77. Phylum, genus and species tables were also built, collapsing the feature table and the taxonomy. Differential abundance analyses were performed using two R (v.4.2.1) packages: MetagenomeSeq (v. 1.38)78 and Limma (v. 3.52.4)79. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The functional potentials of the oral microbiome were inferred using PICRUSt2 analysis, performed with the q2-picrust2 plugin of the QIIME2 version 2021.11, calculating the abundance of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)7,80 Orthology (KO) and Enzyme Commission (EC) number pathways. The differential abundance of these pathways was calculated using MetagenomeSeq and Limma, retaining only those with a p-value < 0.05. All the graphics were computed using ggplot2 (v3.4.1)81 and ggpubr (v.0.6.0)82.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The revision of the English language was provided by Aashni Shah (Polistudium srl).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, DI.E.M, M.G.D; methodology, DI.E.M, G.F.P., M.G.D., F.R., E.G.; validation, M.G.D., DI.E.M; formal analysis, DI.E.M, G.F.P. M.G.D., M.G.; investigation, M.G.D., G.F.P., F.R., E.G.; resources, A.L., M.G., B.P, R.P; data curation, DI.E.M, M.G.D., M.B., F.R., GF.P.; writing—original draft preparation, DI.E.M, G.F.P., M.G.D.; writing—review and editing, DI.E.M, G.F.P., F.R., A.L., E.G., M.B., M.G., B.P., R.P., M.G.D.; visualization, DI.E.M, GF.P., F.R., E.G., M.B., M.G.D.; supervision, M.G.D.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca Corrente).

Data availability

Raw FastQ files related to this project were submitted to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject ID PRJNA1071091). Additionally, raw data are available from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

A written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was cleared by the institutional Ethics Committee, I.F.O. Section-Fondazione Bietti (CE/417/14) and Comitato Etico Territoriale Lazio Area 5 (RS 1821/23).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

David Israel Escobar Marcillo and Grete Francesca Privitera contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-81607-4.

References

- 1.Yamashita, Y. & Takeshita, T. The oral microbiome and human health. J. Oral Sci.59, 201–206 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sepich-Poore, G. D. et al. The microbiome and human cancer. Science371, 4552. 10.1126/science.abc4552 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrd, A. L., Belkaid, Y. & Segre, J. A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.16, 143–155 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Martel, C., Georges, D., Bray, F., Ferlay, J. & Clifford, G. M. Global burden of cancer attributable to infections in 2018: A worldwide incidence analysis. Lancet Glob. Health8, e180–e190 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mena, M. et al. Epidemiology of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer in a classically low-burden region of southern Europe. Sci. Rep.10, 13219 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasman, A., Du, J. & Dalianis, T. A global epidemic increase of an HPV-induced tonsil and tongue base cancer—Potential benefit from a pan-gender use of HPV vaccine. J. Intern. Med.287, 134–152 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreimer, A. R. et al. Oral human papillomavirus in healthy individuals: A systematic review of the literature. Sex. Transm. Dis.37, 386–391 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King, E. M. et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in men who have sex with men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE11, e0157976 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin, W. et al. Changes of the vaginal microbiota in HPV infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A cross-sectional analysis. Sci. Rep.12, 2812–2815 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shannon, B. et al. Association of HPV infection and clearance with cervicovaginal immunology and the vaginal microbiota. Mucosal Immunol.10, 1310–1319 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brusselaers, N., Shrestha, S., van de Wijgert, J. & Verstraelen, H. Vaginal dysbiosis and the risk of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol.221, 9–18 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reimers, L. L. et al. The cervicovaginal microbiota and its associations with human papillomavirus detection in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected women. J. Infect. Dis.214, 1361–1369 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dareng, E. O. et al. Vaginal microbiota diversity and paucity of Lactobacillus species are associated with persistent hrHPV infection in HIV negative but not in HIV positive women. Sci. Rep.10, 19095–19097 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahig, H. et al. Longitudinal characterization of the tumoral microbiome during radiotherapy in HPV-associated oropharynx cancer. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol.26, 98–103 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerrero-Preston, R. et al. 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing identifies microbiota associated with oral cancer, human papilloma virus infection and surgical treatment. Oncotarget7, 51320–51334 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang, Y. et al. Oral human papillomavirus associated with differences in oral microbiota beta diversity and microbiota abundance. J. Infect. Dis.226, 1098–1108 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuominen, H., Rautava, S., Collado, M. C., Syrjanen, S. & Rautava, J. HPV infection and bacterial microbiota in breast milk and infant oral mucosa. PLoS ONE13, e0207016 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segata, N. et al. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol.13, R42 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eren, A. M., Borisy, G. G., Huse, S. M. & Mark Welch, J. L. Oligotyping analysis of the human oral microbiome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.111, 2875 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cameron, S. J. S., Huws, S. A., Hegarty, M. J., Smith, D. P. M. & Mur, L. A. J. The human salivary microbiome exhibits temporal stability in bacterial diversity. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.91, 091 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacunza, E. et al. Oral and anal microbiome from HIV-exposed individuals: Role of host-associated factors in taxa composition and metabolic pathways. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes9, 48–54 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.HOMD (Human Oral Microbiome Database V3.1) (2023)

- 23.Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature486, 207–214 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He, X. et al. Cultivation of a human-associated TM7 phylotype reveals a reduced genome and epibiotic parasitic lifestyle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.112, 244–249 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffen, A. L. et al. Significant effect of HIV/HAART on oral microbiota using multivariate analysis. Sci. Rep.9, 19946–19949 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perez Rosero, E. et al. Differential signature of the microbiome and neutrophils in the oral cavity of HIV-infected individuals. Front. Immunol.12, 780910 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abusleme, L. et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J.7, 1016–1025 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chipashvili, O. et al. Episymbiotic Saccharibacteria suppresses gingival inflammation and bone loss in mice through host bacterial modulation. Cell Host Microbe29, 1649–1662 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camanocha, A. & Dewhirst, F. E. Host-associated bacterial taxa from Chlorobi, Chloroflexi, GN02, Synergistetes, SR1, TM7, and WPS-2 Phyla/candidate divisions. J. Oral Microbiol.6, 1 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang, S., Nie, J., Chen, Y. X., Wang, X. Y. & Chen, F. Structure and composition of candidate phyla radiation in supragingival plaque of caries patients. Chin. J. Dent. Res.25, 107–118 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Urbaniak, C. et al. The influence of spaceflight on the astronaut salivary microbiome and the search for a microbiome biomarker for viral reactivation. Microbiome8, 56 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paster, B. J. et al. Bacterial diversity in necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis in HIV-positive subjects. Ann. Periodontol.7, 8–16 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bertelsen, R. J. et al. Association of oral bacteria with oral hygiene habits and self-reported gingival bleeding. J. Clin. Periodontol.49, 768–781 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen, J. et al. Microbiome landscape of lesions and adjacent normal mucosal areas in oral lichen planus patient. Front. Microbiol.13, 992065 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qi, Y. et al. High-throughput sequencing provides insights into oral microbiota dysbiosis in association with inflammatory bowel disease. Genomics113, 664–676 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neumann, A. Rapid release of sepsis markers heparin-binding protein and calprotectin triggered by anaerobic cocci poses an underestimated threat. Anaerobe75, 102584 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alomair, A. O. et al. Colonic mucosal microbiota in colorectal cancer: A single-center metagenomic study in Saudi Arabia. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract.2018, 5284754 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elnaggar, J. H. et al. HPV-related anal cancer is associated with changes in the anorectal microbiome during cancer development. Front. Immunol.14, 1051431 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wei, Z. et al. Depiction of vaginal microbiota in women with high-risk human papillomavirus infection. Front. Public Health8, 587298 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carandina, G., Bacchelli, M., Virgili, A. & Strumia, R. Simonsiella filaments isolated from erosive lesions of the human oral cavity. J. Clin. Microbiol.19, 931–933 (1984). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pankhurst, C. L., Auger, D. W. & Hardie, J. M. Isolation and prevalence of Simonsiella sp. in lesions of erosive lichen planus and on healthy human oral mucosa. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis.1, 17–21 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villa, T. G., Sanchez-Perez, A. & Sieiro, C. Oral lichen planus: A microbiologist point of view. Int. Microbiol.24, 275–289 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kitamoto, S. & Kamada, N. Periodontal connection with intestinal inflammation: Microbiological and immunological mechanisms. Periodontoligy89, 142–153 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen, Y. et al. Human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia progression are associated with increased vaginal microbiome diversity in a Chinese cohort. BMC Infect. Dis.20, 629–639 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, Y. et al. Association between the vaginal microbiome and high-risk human papillomavirus infection in pregnant Chinese women. BMC Infect. Dis.19, 677–686 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eriksson, K. et al. Salivary microbiota and host-inflammatory responses in periodontitis affected individuals with and without rheumatoid arthritis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol.12, 841139 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gopinath, D. et al. Culture-independent studies on bacterial dysbiosis in oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol.139, 31–40 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paster, B. J. et al. Bacterial diversity in human subgingival plaque. J. Bacteriol.183, 3770–3783 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou, X. et al. The clinical potential of oral microbiota as a screening tool for oral squamous cell carcinomas. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol.11, 728933 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jain, V. et al. Integrative metatranscriptomic analysis reveals disease-specific microbiome–host interactions in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. Commun.3, 807–820 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu, S. et al. Oral microbial dysbiosis in patients with periodontitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol.13, 1121399 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vesty, A. et al. Oral microbial influences on oral mucositis during radiotherapy treatment of head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer28, 2683–2691 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zahran, S., Mannocci, F. & Koller, G. Impact of an enhanced infection control protocol on the microbial community profile in molar root canal treatment: An in vivo NGS molecular study. J. Endod.48, 1352–1360 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang, Y. et al. Comparison of red-complex bacteria between saliva and subgingival plaque of periodontitis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.11, 727732 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hajishengallis, G. & Lamont, R. J. Polymicrobial communities in periodontal disease: Their quasi-organismal nature and dialogue with the host. Periodontology86, 210–230 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maekawa, T. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates complement and TLR signaling to uncouple bacterial clearance from inflammation and promote dysbiosis. Cell. Host Microbe15, 768–778 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Binder Gallimidi, A. et al. Periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum promote tumor progression in an oral-specific chemical carcinogenesis model. Oncotarget6, 22613–22623 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ha, N. H. et al. Prolonged and repetitive exposure to Porphyromonas gingivalis increases aggressiveness of oral cancer cells by promoting acquisition of cancer stem cell properties. Tumour Biol.36, 9947–9960 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wen, L. et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes oral squamous cell carcinoma progression in an immune microenvironment. J. Dent. Res.99, 666–675 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kononen, E., Fteita, D., Gursoy, U. K. & Gursoy, M. Prevotella species as oral residents and infectious agents with potential impact on systemic conditions. J. Oral Microbiol.14, 2079814 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewy, T. et al. Oral microbiome in HIV-infected women: Shifts in the abundance of pathogenic and beneficial bacteria are associated with aging, HIV load, CD4 count, and antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses35, 276–286 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li, J. et al. Altered salivary microbiome in the early stage of HIV infections among young Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM). Pathogens9, 960. 10.3390/pathogens9110960 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Celik, A., Diler, S. B. & Eke, D. Assessment of genetic damage in buccal epithelium cells of painters: Micronucleus, nuclear changes, and repair index. DNA Cell Biol.29, 277–284 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rehani, S. et al. Genotoxicity in oral mucosal epithelial cells of petrol station attendants: A micronucleus study. J. Cytol.38, 225–230 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abe, N. et al. Biochemical and functional properties of lysine-specific cysteine proteinase (Lys-gingipain) as a virulence factor of Porphyromonas gingivalis in periodontal disease. J. Biochem.123, 305–312 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gasmi Benahmed, A., Kumar Mujawdiya, P., Noor, S. & Gasmi, A. Porphyromonas gingivalis in the development of periodontitis: Impact on dysbiosis and inflammation. Arch. Razi Inst.77, 1539–1551 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kirst, M. E. et al. Dysbiosis and alterations in predicted functions of the subgingival microbiome in chronic periodontitis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.81, 783–793 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brzuszkiewicz, E. et al. Comparative genomics and transcriptomics of Propionibacterium acnes. PLoS ONE6, e21581 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Noguera-Julian, M. et al. Gut microbiota linked to sexual preference and HIV infection. EBioMedicine5, 135–146 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Armstrong, A. J. S. et al. An exploration of Prevotella-rich microbiomes in HIV and men who have sex with men. Microbiome6, 198–207 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li, X. et al. The oral microbiota: Community composition, influencing factors, pathogenesis, and interventions. Front. Microbiol.13, 895537 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rollo, F. et al. Prevalence and determinants of oral infection by human papillomavirus in HIV-infected and uninfected men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE12, e0184623 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Giuliani, M. et al. Oral human papillomavirus infection in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected MSM: The OHMAR prospective cohort study. Sex. Transm. Infect.96, 528–536 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rollo, F. et al. Oral testing for high-risk human papillomavirus DNA and E6/E7 messenger RNA in healthy individuals at risk for oral infection. Cancer125, 2587–2593 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore.

- 76.Bolyen, E. et al. Author Correction: Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 1091–1096 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Escapa, I. et al. Construction of habitat-specific training sets to achieve species-level assignment in 16S rRNA gene datasets. Microbiome8, 65 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Paulson, J. N., Stine, O. C., Bravo, H. C. & Pop, M. Differential abundance analysis for microbial marker-gene surveys. Nat. Methods10, 1200–1202 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res.43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG for integration and interpretation of large-scale molecular data sets. Nucleic Acids Res.40, 109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wickham, H. ggplot2 Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (2016).

- 82.Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw FastQ files related to this project were submitted to NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject ID PRJNA1071091). Additionally, raw data are available from the corresponding author.