Abstract

The repercussions of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and bisphosphonates pose serious clinical challenges and warrant novel therapies for osteoporosis in menopausal women. To confront this issue, the present research aimed to design and fabricate daidzein (DZ); a phytoestrogen-loaded hydroxyapatite nanoparticles to mimic and compensate for synthetic estrogens and biomineralization. Hypothesizing this bimodal approach, hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HAPNPs) were synthesized using the chemical-precipitation method followed by drug loading (DZHAPNPs) via sorption. The developed nanoparticles were optimized by "Design-Expert" software and underwent comprehensives in-vitro and in-vivo characterizations. The particle sizes of HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs were found to be 118.9 ± 0.15 nm and 129.3 ± 0.65 nm, respectively, consistent with their FESEM and TEM images. A notable entrapment efficiency of 87.23 ± 0.97% and drug release of 91 ± 0.85% from DZHAPNPs was observed over 90 h at pH 7.4. Moreover, the XRD and FTIR results confirmed the amorphization and compatibility of DZHAPNPs. TGA analysis indicated that the thermal stability of blank and drug-loaded nanoparticles was up to 900 °C. In an in vivo pharmacokinetic investigation, three-fold increased bioavailability of DZHAPNPs (AUC0−∞ = 7427.6 µg/mL*h) was obtained in comparison to daidzein solution (AUC0−∞ = 2299.7 µg/mL*h). The comprehensive results of the study indicate that bioceramic nanoparticles are potential carriers for DZ delivery.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-85463-8.

Keywords: Calcium-phosphate, Hydroxyapatite, Daidzein, Pharmacokinetics, Nanoparticles

Subject terms: Drug delivery, Pharmaceutics

Introduction

Post-menopausal-osteoporosis (PMO) is a hormone-dependent skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density and degenerated bone micro-architecture, culminating in bone fragility and fracture1,2. As per clinical data, approximately 8 million women worldwide prevail with post-menopausal osteoporosis, primarily due to a decline in circulating estradiol3. Conventional treatments like hormone replacement therapy (HRT), bisphosphonates, vitamin D, anabolic drugs, and SERMS are generally used for managing hormone withdrawal symptoms and bone loss after menopause4,5. However, their proliferative effect on the uterus, vagina, cervix, and breast augments other serious implications6,7. Also, the benefits derived from these first-line treatments are time-bound, upon discontinuation, both menopausal symptoms and bone deterioration relapse occur8. Inevitably, there is a dire need for novel approaches to compensate for hormonal deficiency and alleviate post-menopausal symptoms like bone loss9.

Various plant metabolites, particularly isoflavones and lignans obtained from sources such as soy, black cohosh, licorice, red raspberry, red clover, kudzu, chaste tree berry, hops, dong-quai, and foti, have garnered considerable interest in the management of PMO recently10,11. These polyphenolic compounds, collectively termed phytoestrogens, exhibit structural similarity to 17-beta-estradiol, the primary form of estrogen in humans12. Among these, soy isoflavones have been extensively studied for their potential to mimic biological estrogen’s structural and functional properties, offering a natural alternative for hormone replacement therapy in PMO13. Soy isoflavones, including genistein and daidzein, are key phytoestrogens with notable estrogenic activity14. These compounds are commonly prescribed as supplements to maintain bone density in post-menopausal women, with genistein and daidzein demonstrating significant potential in mitigating bone loss15,16. Daidzein has emerged as a promising natural therapeutic agent due to its ability to bind to estrogen receptors and exert beneficial effects on bone health17,18. The mechanism of action of daidzein involves differentiation of osteoblasts (induces the expression of osteoprotegerin (OPG), an osteoclastogenesis inhibitor) and inhibition of the expression of “receptor activator nuclear factor-KB ligand (RANKL)” responsible for differentiation of osteoclasts19–21. Interestingly, the potent metabolite of daidzein “equol” is reported to have stronger estrogenic activity than other isoflavones. Despite being a potent phytoestrogen, targeting DZ to poorly perfused bones was challenging. The physicochemical properties of DZ, i.e. poor solubility, low permeability, pH sensitivity, and low bioavailability, restrict its delivery to bones22,23. Consequently, profuse ligands and carrier systems were evaluated for bone targeting in PMO. Among all, bioceramics were found to be best suited due to their compositional and shape similarity and excellent biocompatibility with bone minerals24–26. Bioceramics consist of calcium phosphates, silica, alumina, zirconia, and titanium dioxide and are used for numerous medical applications due to their positive interactions with human tissues27,28. Some of the key benefits of bioceramics as nanocarriers are: (i) drug-delivery in a minimally invasive manner, just as polymeric nanoparticles; (ii) ease of fabrication; (iii) economic and viable; (iv) longer circulation in the body; (v) do not swell or change porosity; and (vi) stable at variations in temperature and pH.29. Therefore, hydroxyapatite was selected as a bioceramic nanocarrier for loading DZ, targeted at bone-specific delivery.

So, we hypothesized a novel bimodal approach for the synergistic treatment of PMO, wherein the DZ is s expected to target ER receptors in osteoblast cells for their hormone-dependent proliferation, and the bioceramic nanocarriers would supposed to facilitate bone mineralization. Accordingly, for the first time, engineered delivery of DZ through HAP nanoparticles, which are not only self-targeted nanocarriers but would also demonstrate exceptional bone mineralization proficiency . Utilizing the Quality by design (QbD) approach, HAP nanoparticles were prepared by the wet chemical precipitation method and loaded with DZ via sorption. The Box-Behnken design (BBD) model was applied to thoroughly investigate the impact of formulation and process parameters in the optimization of nanoparticles. The developed formulation was characterized comprehensively for surface morphology, X-ray crystallography, thermogravimetry, dissolution studies, bioavailability, and stability studies to conclude the results. In the results, the developed HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs illustrated the commensurate features of the desired nanocarrier, including nano-size, drug entrapment, zeta potential, drug release, bioavailability, and stability. Together, these studies support daidzein-HAP nanoparticles as a novel attractive therapy for PMO.

Materials and methods

Materials

Daidzein, Hydroxyapatite, and Methanol were procured from Sigma Aldrich (India). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, purity N 99.0%) and diethyl ether (purity 99.0%) were purchased from SD Fine Chemicals (India). Dialysis sacs (mol. wt. cut-off: 12 000 Da, flat with 25 mm, a diameter of 16 mm, a capacity of 60 mLft) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (India). Ammonium dihydrogen phosphate, Ammonia solution (specific gravity of 0.89), methanol, and isopropyl alcohol were procured from Thomas Baker Chemicals Private Ltd., Mumbai, India. HPLC grade methanol was obtained from Loba Chemicals Private Ltd., Mumbai, India. All reagents were of analytical grade. Milli-Q (MQ) water was used throughout the study.

Methods

In our previous paper, several methods for in vitro synthesis of bioceramic (HAP) nanoparticles have been reported30. For instance, the methods include biomimetic deposition, electro-deposition, wet chemical precipitation, mechanochemical synthesis, surfactant-based emulsification, ultrasonication and sintering, and sol-gel method. In the current study, we opted for the wet chemical precipitation method. Benefits like easy processing, increased yield, feasibility, limited and low-cost reagents requirement, and desirable synthesized nanoparticles properties have been reported. Following the synthesis of HAP nanoparticles, the drug was loaded via sorption.

Fabrication of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (HAPNPs)

The HAP nanoparticles were prepared by the wet chemical precipitation method(31). Accordingly, Calcium Nitrate and Ammonium Dihydrogen Phosphate solutions were used as precursors in a constant molar ratio of Ca/P (1:0.67) (Eq. 1). The solutions of 0.5 M calcium nitrate [Ca (NO3)] and 0.3 M ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (NH4H2PO4) were made by dissolving the respective compounds in distilled water and stirring at 1200 rpm for 30 min. Additionally, a 25% amonia solution was prepared to maintain the alkaline pH of the reaction mixture. The ammonium-phosphate solution was gradually added to calcium nitrate while keeping the reaction mixture under continuous stirring for 4–6 h. The pH of the resulting solution was maintained above 10 until the reaction was complete. A milky solution of nanoparticles was obtained as the end product. Following an hour of autoclaving at 180 °C, the precipitated HAP nano-powder was separated using centrifugation for ten min at 14000 RPM. After washing with millipore water, the HAP nano-precipitate was placed in a hot air oven at 50 °C and dried overnight.

|

1 |

Sorption of diadzein over HAPNPs

A modest method, based on adsorption was adopted to load the drug over highly porous HAP nanoparticles32. 10–20 mg of the drug was dissolved in methanol (30–50 ml) followed by the dispersion of blank HAP nanoparticles in different ratios to the drug., i.e. 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3. Further, sonicated the resultant mixture for 20 mins until HAP nanoparticles were uniformly dispersed. For effective drug loading, the sample was kept on a magnetic stirrer (at 1000–1200 rpm) for up to 24 h. The resulting nano-suspension obtained at the end of loading was further centrifuged at 24,000 rpm for 25 min. The pellet was collected and dried overnight to obtain drug-loaded nanoparticles.

Formulation optimization by QbD approach

Since the entire formulation-development involved two distinct stages of nanoparticle synthesis (HAPNPs) and drug loading (DZHAPNPs), to obtain a precision-controlled formulation, we performed optimization in both stages utilizing the QbD approach. Among response surface designs, we opted for Box-Behnken design through Design Expert® (Version 11.1.0.1–64 Bit software by Stat-Ease 360, Inc, 1300 Godward Street North-East, Suite 6400 Minneapolis, MN 55413, http://www.statease.com/dx10.html#features).

Initial risk assessment and experimental design

This involves identifying and assessing various parameters affecting the crucial quality characteristics of the final formulation. These parameters include critical material attributes (CMAs) and critical process parameters (CPPs) (supplementary Table S1). The effect of these CMAs and CPPs was assessed to identify the intensity of their impact, and the appropriate range of each variable. The interaction between critical attributes and risk assessment was performed using a 3-level risk assessment scale (low, medium, high). The conclusions are outlined in supplementary Table S2. Following that, the independent variables having the greatest influence were selected and optimized using the Box-Behnken design.

For HAPNPs, the selected independent variables were the pH of the ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (H3PO4) solution, the pH of the calcium nitrate solution, and the dilution factor of reactant solutions. The identified constraints were particle size and PDI of nanoparticles. However, for DZHAPNPs the selected independent variables were the ratio of drug to blank HAP nanoparticles, volume of the dispersion medium, and loading time and constraints were hydrodynamic diameters, % drug entrapment, and zeta-potential of drug-loaded nanoparticles. Table 1 shows the levels of independent variables, their severity, and constraints on the chosen responses of DOE. The experimental design gave 17 runs and each predicted formulation was fabricated. The dependent responses were assessed to analyze the effectiveness of the predicted formulation.

Table 1.

Design of experiment variables using BBD.

| HAPNPs | DZHAPNPs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Levels | Independent variables | Levels | ||||

| -1 | 0 | +1 | -1 | 0 | +1 | ||

| Factor 1: pH of ammonium phosphate solution | 8 | 10 | 12 | Factor 1: Ratio of the drug to HAPNPs | 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:3 |

| Factor 2: pH of calcium nitrate solution | 8 | 11 | 14 | Factor 2: Volume of dispersion medium | 30 ml | 40 ml | 50 ml |

| Factor 3: Dilution of the reactant solutions keeping the Ca/P ratio at 1:0.67 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | Factor 3: Loading Time | 12 h | 18 h | 24 h |

| Dependent variables | Constraints | Dependent variables | Constraints | ||||

| Response 1: Particle Size (nm) | Minimum | Response 1: Particle Size (nm) | Minimum | ||||

| Response 2: PDI | Minimum | Response 2: Entrapment Efficiency | Maximum | ||||

| Response 3: Zeta Potential | Maximum | ||||||

The average particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of all the formulation batches were measured by Zeta-Sizer; however, the percent drug entrapment was calculated by indirect method. In the study of the relationship between dependent and independent variables, model-generated polynomial equations were evaluated. 3D surface and contour maps were obtained with BBD that showed the effects of independent variables on dependent variables. Then, ANOVA was applied to the obtained responses and generated equations for each.

Based on QbD and identified critical elements (CQAs, CPPs, and CMAs) impacting the quality target product profile (QTPP), an Ishikawa diagram was constructed, in which the key components (responsible for ultimate attributes of the product) were distinguished and grouped (supplementary Figure S1).

In vitro characterization of blank HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs

FTIR identification of daidzein and HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs

FTIR analysis of daidzein and synthesized HAP nanoparticles was performed in a frequency range of 4000 –400 cm–1 utilizing BRUKER ALPHA II33,34. To evaluate the compatibility, powders of DZ and HAPNPs were mixed in equal proportion and kept at ambient conditions for seven days and then analysed by FTIR. Also, the FTIR analysis of drug loaded nanoparticles (DZHAPNPs) was performed to confirm the drug loading over HAPNPs.

Particle size, size distribution (PDI), and zeta potential

The particle size and PDI of the HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs were determined using a zeta sizer (Anton-Paar Litesizer 500 with an inbuilt software naming “Kalliope™). Briefly, the samples were diluted 100 times using distilled water and vortexed for 5 min before analysis. Then, the samples were analyzed at 25°C temperature and at a scattering angle of 90°35. Zeta potential was determined by employing the Laser Doppler Electrophoresis method. The samples were diluted 200 times with deionized distilled water before each measurement. All the samples were analyzed in triplicate.

FESEM and TEM

To study the detailed morphology i.e. shape, size, and surface characteristics of the diadzein powder, blank HAPNPs, and DZHAPNs, field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) was done. The samples were coated by gold (Zeiss Gemini SEM 500 Thermal field emission type, acceleration voltage 0.02 kV–30 kV, and magnification 50X–2,000,000X) and kept in the sampling unit as thin films for visualization. The photographs were taken at different magnifications36.

In addition, to confirm the results of FESEM, Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) of DZHAPNPs was also performed. For TEM analysis (TECNAI, G2-20), DZHAPNPs were suspended in water and sonicated followed by staining using a 1% phosphotungstic acid aqueous solution. Further, a few microlitres of stained nanosuspension were poured over a microscopic-carbon-coated grid37. After proper drying, the sample was visualized under the microscope.

Percent Drug entrapment and loading

By using an indirect method, the entrapment efficiency (EE) of drug-loaded nanoparticles was ascertained. Drug-loaded nanoparticles (DZHAPNs) in nano-suspension were centrifuged for 30 min at 16,000 rpm38. To estimate the amount of free drug, the supernatant was carefully collected and subjected to analysis using a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (UV-1800, Shimadzu, Japan). The following formula was used to get the percentage of entrapment efficiency:

|

2 |

|

3 |

Where, Di & Df and C represent the initial drug amount, free drug, and the overall amount of nanoparticles added respectively. All tests were done in triplicate (mean ± SD).

X-Ray diffraction study

To determine the crystallinity of DZ, blank HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs, an X-ray Diffraction (XRD) study was carried out by High-Resolution X-Ray Diffractometer (Bruker, D8 Discover) at Bragg’s angle (2θ) ranging from 5° to 90°, CuKα (λ = 0.154 nm) and a scanning rate of 0.020/min39. The average size of crystals was estimated by the Debye-Scherrer formula (Eq. 4).

|

4 |

Wherein, K is the shape factor, β is the line broadening parameter and Ɵ is Bragg’s angle (in radians) and λ is the X-ray wavelength of the Cu Kα radiation.

The percent crystallinity of all samples was calculated using the OriginPro 2023b software (OriginLab, USA (64Bit SR1 10.0.5.157)-Trial Version).

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The thermal behavior and stability of DZ, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs were characterized by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) in terms of percentage weight loss after a slow temperature increase up to 900 °C. Samples were subjected to TGA analysis using a thermogravimetric analyzer (Model TGA HiRes1000)37. Five milligrams of the samples were put into platinum pans and heated gradually at a rate of 10 °C per min while inert nitrogen gas flowed at a rate of 60 mL per min in dry air. The samples were heated from 5 °C to 900 °C.

Drug release and release kinetics

An in-vitro drug release study was performed at pH 7.4 and pH 6.5 in triplicate for optimized batches of DZHAPNPs and drug suspension (DZ) as per the method reported22. For the dissolution study, 10 mg of each, drug (DZ) and DZHAPNPs (comprising 10 mg of the equivalent weight of daidzein) were transferred in a dialysis bag (chocolate/toffee model) and placed in separate beakers having 50 ml of PBS (pH of 7.4 and 6.5). Beakers containing the sample were kept on top of a magnetic stirrer set to 100 RPM and 37 ± 2 °C for 96 h. Throughout the investigation, the sink condition was maintained, and dissolution samples were obtained at predetermined intervals. By UV spectroscopy, the drug content of dissolution samples was determined at λmax of 249 nm. The best fit was identified when the dissolution data was processed to drug-release-kinetic models, including Zero-Order, First-Order, Korsmeyer-Peppas, Hixson-Crowel, and Higuchi models, to investigate the drug-release process.

Stability studies

The stability of HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs was estimated at different accelerated stability study conditions i.e. 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C according to ICH guidelines for six months. The deterioration in the formulation was measured in terms of physical change, particle size, drug-content, and shift in λmax during its storage.

Blood compatibility studies (hemolytic activity)

The hemolytic potential of DZ, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs was investigated by the method described by von Petersdorff-Campen K in 2022 41. Briefly, heparinized blood (0.2 mL) collected from the rat was added to five different vials (out of the five vials, 4 were containing 3 mL of normal saline whereas one vial was added with 3 mL of distilled water). All the formulations, DZ, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs (1000 µg/mL) were added individually in three saline-containing vials. Afterward, all the vials were incubated (37 °C) in an incubator shaker for one hour, and undergone centrifugation at 6000 rpm for 20 min. To determine the quantity of hemoglobin released as a result of hemolysis, the resulting supernatant was further filtered and scanned in a UV spectrophotometer at λmax 545 nm.

The hemolytic activity was calculated by:

Haemolytic Activity = [absorbance of the sample (formulation) − absorbance of negative control] / absorbance of positive control (distilled water).

Pharmacokinetic study

Animals

Before the start of animal experiments, approval was obtained from the Delhi Pharmaceutical Science and Research University’s Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Approval No. IAEC/2023/II-09). All animal experiments adhere to the ARRIVE guidelines and were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition). Eight-week-old female Wistar rats weighing 250 ± 10 g on average were obtained from the departmental animal house. Every animal received regular feeding and unrestricted access to mineral water. The animals were acclimated to a regulated room temperature of 25 ± 2 °C with a 12 h light/dark cycle.

HPLC method

A reported HPLC test technique was utilized with slight modification to measure the amount of daidzein in blood plasma22. The HPLC equipment used for all pharmacokinetic data estimation was a Shimadzu “LC-20A” series chromatographic system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a “SPD-20A” UV–Vis detector and a “LC-20 AT” binary pump. A Dikma Dimonsil C18 column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size) was used for HPLC estimation33. The program “LC Solution” was used to analyze the data. The HPLC equipment was tested and optimized for the reported parameters before conducting pharmacokinetic experiments (Supplementary Table S3)41. The chosen HPLC method’s sensitivity, linearity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision were all validated. In a nutshell, all of the daidzein standard stock solutions and working solutions were made with HPLC-grade methanol and kept at −20 °C.

To check the linearity of the method, standard samples of DZ in the concentration range of 0.5–20 µg/mL were analyzed for their peak area (mAU) and plotted against their respective concentration. Further, the method was checked for its reproducibility in treated plasma samples42. A calibration curve was also constructed in plasma samples by spiking a specific amount of daidzein standard solutions to blank plasma. Chromatograms of blank plasma samples, spiked plasma samples (six repetitions), and standard DZ solutions in the concentration range of 0.5–20 µg/mL were compared to determine the analytical method’s selectivity. In addition, standard curves made in plasma were used to compute the LOD and LOQ. Moreover, three standard DZ solutions (10, 50, and 100 µg/mL) were subjected to six intra-day and six inter-day HPLC analyses to determine accuracy and precision in terms of %RSD.

Plasma sample treatment

Plasma samples were prepared by the simplest method reported by Zhao X et al. 2011(41) with slight modification. The method involves the following steps: (i) obtain 100 µL plasma by centrifugation of blood collected, (ii) spike the blood plasma with 10 µL of the standard solution of daidzein, (iii) add 900 µL acetonitrile to the spiked plasma samples to coagulate the plasma proteins, (iv) centrifuge at 10000 RPM, at −4 °C in a refrigerated centrifuge to remove coagulated plasma proteins, (v) collect the supernatant and dry in presence of nitrogen gas, (vi) re-dissolve the dried matter in 100 µL methanol.

Animal groups and study design

The three groups of healthy female Wistar rats were randomly assigned to receive PK estimations of DZHAPNPs. The animals in the control group were given regular saline after an overnight fast and unrestricted access to water. Test groups I and II, on the other hand, were given intravenous doses of DZ solution and DZHAPNPs in an equivalent dosage of DZ 10 mg/kg respectively. A tail restraint device was used for restraining the rats. The tail warmed using a warm water bath (around 37 °C) for a short time. This helps dilate the tail veins, making blood collection easier and less stressful. Following injection, at 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 30, and 38 h, 300 µL of blood was drawn from the tail vein and placed into heparinized micro-centrifuge tubes. To extract 100 µL of plasma, the obtained blood samples were spun in a chilled centrifuge for 20 min at 6000 rpm. At the end of the experiment, rats were sacrificed by using CO2 inhalation, and the carcasses were sent to the animal house in yellow polyethene bags for disposal.

Calculations and statistics

A linear regression analysis was performed to estimate the linearity of the adopted HPLC-UV method. For bioavailability assessment, “AUC0−last” was determined from the initial time point (time = 0) till the last quantifiable concentration of the drug by employing the trapezoidal rule. The LC Solution software (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used to analyze the HPLC results of the samples, and the PK-Solver program (Version 2.0 in MS-Excel-2019) was used to ascertain additional pharmacokinetic parameters. A significance level of p < 0.05 was deemed to signify noteworthy variations. All data were expressed as the “mean ± standard deviation/standard error” after statistical analysis, and one-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data.

Results and discussions

Preparation of HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs

A wet chemical precipitation process was used to prepare highly porous hydroxyapatite nanoparticles, with sizes ranging from 110 to 120 nm. While synthesizing HAP nanoprecipitates, it was found that the precursors of calcium and phosphate ions interacted with one another in a specific pH range, usually above 9. A lower pH usually results in increased protonation of phosphate groups leading to the formation of phosphoric acid (H3PO4) and thus reducing the chances of nano-precipitation. Therefore, an appropriate balance between free OH− ions and PO43−ions is required during the synthesis of HAPNPs. To attain effective ionization of reactants and speed up the forward reaction, a constant alkaline pH between 10 and 12 should be maintained throughout the reaction. In contrary to this, there is a high probability of reduced pH of the reaction mixture due to the formation of nitric acid as a by-product. To avoid this, an excess quantity of ammonia solution is added. Also, the ammonia solution maintains the requisite pH (11–12) for effective ionization of the reactant species. Thus, pH is crucial for the nano-precipitation of HAPNPs43. Consequently, pH plays a critical role in the nano-precipitation of HAPNPs. In addition, at the beginning of the reaction, quicker collisions between reactant molecules were avoided to prevent their nucleation and produce larger precipitates. The concentration of Ca (OH)2was lowered to 0.5 M from 1 M after it was noticed that a higher concentration of calcium precursor is the reason for aggregation that results in large micron-sized particles of HAP44.

Generally, HAPNPs synthesized by the wet chemical precipitation method are hollow and extremely porous crystals with nanosized channels. Despite their extreme crystallinity, they can load large amounts of drug and exhibit distinct drug release behaviour at physiological pH24.The optimized HAPNPs were loaded with daidzein by sorption as explained in Sect. 2.3.

Optimization of blank and drug-loaded nanoparticles through QbD

The formulation was optimized by the Quality by Design (QbD) approach due to its undue advantages over the hit-and-trial method. DoE (Design of Experiment) is an integral part of the QbD approach, which involves using the BBD to generate structured data Table45. The BBD visually represents the outcomes and how each variable influences the formulation’s critical quality attributes (CQAs)46. The Box-Behnken design (BBD) was selected due to its superior factorial design capabilities.

Optimization of HAPNPs

Once the minimum and maximum values of the independent variables were fed into the BBD experimental design software, 17 trials with five central points were recommended. These 17 formulations were prepared and examined, and the resulting values of the dependent variables were recorded in Table 2. The hydrodynamic diameter (Y1) determined, had the experimental range from 115 to 120 nm and PDI (Y2) ranged from 0.180 to 0.390. When the experimental results of hydrodynamic diameter and PDI were analyzed through optimization software, it suggested polynomial quadratic models, for both dependent responses.

Table 2.

DoE-Generated optimization of HAPNPs.

| Run | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Response 1 | Response 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH of Ammonium Phosphate | pH of Calcium Nitrate | Dilution Factor | Particle Size nm |

PDI % |

|

| 1 | 11 | 10 | 0.5 | 210.26 | 0.3956 |

| 2 | 12 | 11 | 0.7 | 202.93 | 0.3862 |

| 3 | 10 | 12 | 0.6 | 129.07 | 0.3544 |

| 4 | 11 | 12 | 0.7 | 167.12 | 0.3454 |

| 5 | 11 | 11 | 0.6 | 152.04 | 0.3941 |

| 6 | 12 | 12 | 0.6 | 118.06 | 0.2843 |

| 7 | 12 | 10 | 0.6 | 240.7 | 0.3356 |

| 8 | 11 | 12 | 0.5 | 194.18 | 0.3587 |

| 9 | 12 | 11 | 0.5 | 239.08 | 0.3589 |

| 10 | 11 | 11 | 0.6 | 139.04 | 0.3641 |

| 11 | 11 | 10 | 0.7 | 222.86 | 0.3939 |

| 12 | 10 | 10 | 0.6 | 228.26 | 0.3706 |

| 13 | 11 | 11 | 0.6 | 163.04 | 0.3641 |

| 14 | 11 | 11 | 0.6 | 140.04 | 0.3541 |

| 15 | 10 | 11 | 0.5 | 225.44 | 0.3852 |

| 16 | 11 | 11 | 0.6 | 210.04 | 0.3641 |

| 17 | 10 | 11 | 0.7 | 307.12 | 0.4129 |

Effect of independent variables on particle size

The size of the nanoparticles has enormous implications for their targeting capability and efficacy inside the body. Upon ANOVA analysis of the experimental data, in model summary statistics a higher predicted R2 value of 0.9347 for the quadratic model was obtained and it was very close to its Adjusted R2 value of 0.9563. This is an indication of the ample precision of the model adopted. Also, the signal-noise ratio of the model was found to be 45.849 reflecting an adequate signal. Upon statistical treatment, the model terms depicted a quadratic equation with a significance of “p” value less than 0.0500. The following generated equation shows the effect of pH of calcium nitrate (A), pH of ammonium phosphate (B), and dilution factor (C) on hydrodynamic diameter.

|

5 |

According to the above equation, negative coefficients of A and B, indicate an inverse relation between particle size and pH values of calcium nitrate and ammonium phosphate solution whereas a positive coefficient of C correlates that a higher concentration of precursors will result in large particle size. This correlation of variables is depicted in the 3-D plots for hydrodynamic diameter [Fig. 1 (a-c)]. Upon thorough investigation it was observed that upon increasing the pH of both Ca and P precursors from 10 to 11, there was a slight decrement in particle size however beyond pH 11, a notable reduction in particle size was observed. Also, an increase in dilution factor from 0.5 to 0.6 resulted in low hydrodynamic diameter whereas upon increasing dilution from 0.6 to 0.7, no significant change was observed. The combined effect of these variables had a less significant impact as compared to their individual effect.

Fig. 1.

Effect of Independent Variables on Particle Size of HAPNPs.

Effect of independent variables on PDI

Polydispersity is the ratio of standard deviation to the mean hydrodynamic diameter. The less the value of the PDI, the more uniform the hydrodynamic diameter of the nanoparticles. Experimental data underwent ANOVA analysis, and the model summary statistics showed a higher R2 (0.9673) for the quadratic model. The polydispersity values of the formulation ranged from 0.282 to 0.391 which indicated the formation of homogeneous monodisperse stable nanoparticles. The following generated equation shows the effect of the independent variables on PDI.

|

6 |

The independent variables A and B (pH of precursors) had not much impact on PDI, as their coefficient values were found to be insignificant. Also, the negative coefficient values of A and B signify that lower pH values of reactants will elevate the PDI (undesirable) and vice-versa. However, a positive coefficient of C in the equation depicts a linear relation between the concentration of reactants and the PDI of the formulation. Therefore, for a minimal PDI (below 3%), an optimal dilution is suggested. Figure 2 (a-c) depicts the impact of independent variables on the PDI of HAPNPs.

Fig. 2.

Effect of Independent Variables on PDI of HAPNPs.

Optimization of DZHAPNPs

Initially, during the optimization of DZHAPNPs, multiple factors were considered for maximum drug loading and minimal particle size. The density of HAPNPs synthesized was comparatively high (3.24 g/cm3), leading to faster sedimentation while drug loading. Thus, it was crucial to keep the HAPNPs in motion for a longer time at a higher speed to attain maximum sorption of the drug. The results of trial batches construed to the final selection of independent variables wherein, the ratio of drug to blank HAPNPs, the volume of the dispersion medium, and loading time were crucial for CQAs like particle size, entrapment efficiency, and zeta potential of the developed DZ-HAPNPs. For optimization,17 different formulations were predicted by the Design Expert (version 11) altering independent variables. the outcome of their discrete blends reflecting their corresponding effects on the dependent responses are tabulated in Table 3. The range of determined dependent responses was as follows; hydrodynamic diameter (Y1) 129.2 to 148.7 nm, percent drug entrapment (Y2) 63.1–87.2%, and zeta-potential (Y3) -18.01 to −22.7 mV. When the experimental results of particle size, zeta-potential, and % drug entrapment were fed to the optimization design, the BBD suggested polynomial quadratic models, for all three dependent responses.

Table 3.

DoE- generated optimization of DZHAPNPs.

| Run | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Response 1 | Response 2 | Response 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HAP: DZ | Dispersion Volume (mL) | Loading Time(hr) | Particle Size (nm) | Entrapment (%) |

Zeta Potential (mV) | |

| 1 | 3 | 40 | 12 | 142.15 | 66.54 | −18.88 |

| 2 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 140.01 | 72.99 | −20.39 |

| 3 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 139.65 | 78.29 | −20.42 |

| 4 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 138.99 | 76.99 | −21.51 |

| 5 | 2 | 30 | 12 | 136.9 | 63.91 | −18.33 |

| 6 | 1 | 30 | 18 | 140.47 | 67.13 | −17.45 |

| 7 | 3 | 40 | 24 | 143.17 | 63.13 | −19.04 |

| 8 | 2 | 50 | 12 | 139.59 | 65.89 | −20.07 |

| 9 | 3 | 30 | 18 | 140.01 | 68.54 | −19.45 |

| 10 | 2 | 30 | 24 | 139.91 | 76.51 | −20.3 |

| 11 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 138.97 | 68.29 | −21.42 |

| 12 | 2 | 40 | 18 | 139.65 | 79.05 | −20.6 |

| 13 | 1 | 50 | 18 | 136.28 | 65.85 | −19.64 |

| 14 | 2 | 50 | 24 | 129.2 | 87.22 | −22.72 |

| 15 | 1 | 40 | 12 | 148.73 | 63.46 | −19.18 |

| 16 | 1 | 40 | 24 | 139.62 | 78.47 | −20.31 |

| 17 | 3 | 50 | 18 | 134.58 | 66.18 | −18.09 |

Effect of independent variables on particle size

Since HAPNPs were meant to be surface loaded with DZ it was essential to keep the particle size as small as possible. The statistical analysis of experimental data revealed a higher predicted R2 value (0.9461) for the quadratic model. Also, the signal-noise ratio of the adopted model was 39.8 reflecting an adequate signal. Upon ANOVA treatment, the model terms of a quadratic equation were found to be significant with “p” values less than 0.0500. The following generated equation shows the effect of the ratio of HAPNPs to DZ (A), dispersion volume (B), and loading time (C) on hydrodynamic diameter.

|

7 |

According to the above equation, negative coefficients of A and B, indicate an inverse relationship between particle size and HAPNPs-DZ ratio (A), dispersion volume (B), and loading time (C). The least coefficient of B signifies the minimal role of dispersion volume in drug loading however maximum coefficient of AC indicates a significant impact of the ratio of DZ to HAPNPs and loading time on particle size [Fig. 3 (a-c)]. Precisely, it was observed that the maximal ratio of HAPNPs to DZ should not be more than 2 whereas, the loading times should be above 20 h to achieve minimal particle size of DZHAPNPs.

Fig. 3.

Impact of Independent Variables on Particle Size of DZHAPNPs.

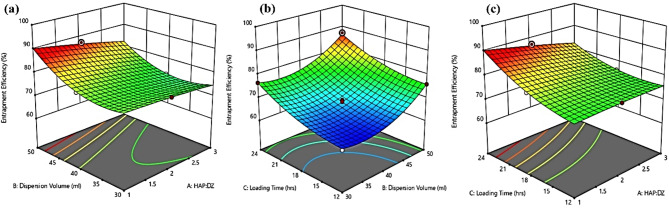

Impact of independent variables on percent drug entrapment

Since in the current formulation, the drug was surface adsorbed, therefor it was quite challenging to entrap the maximum of the drug while attaining the minimum size of nanoparticles. As the synthesized HAPNPs were extremely porous, deeper drug penetration in cracks and crevices resulted in non-bulkier particles with enormous entrapment. Upon ANOVA treatment of experimental data, a higher value of R2 (0.9978) for the quadratic model was obtained. The following generated equation shows the effect of independent variables on percent drug entrapment.

|

8 |

According to the above equation, the highest coefficients of A and C, indicates the potential role of drug-nanoparticle ratio and loading time on drug entrapment. Also, positive coefficients of A, B, and C signify their linear relationship. Despite this, the combined effect of these variables had a less significant effect as compared to their individual effects [Fig. 4 (a-c)]. The reason behind the extensive entrapment upon increasing the quantity of nanoparticles is the availability of a larger surface area however large volume of dispersion medium is expected to facilitate non-competitive surface interaction of HAPNPs with the drug.

Fig. 4.

Impact of Independent Variables on Entrapment Efficiency of DZHAPNPs.

Role of independent variables on zeta potential

Zeta potential establishes the stability of nanoformulation while suspended in a medium. A higher zeta potential near ± 30 mV indicates the stability of the formulation. Since HAPNPs were negatively charged, the zeta potential of DZHAPNPs was found to be near − 20 to −25mV. The statistical analysis of experimental data suggested a quadratic model. The “Predicted R2” value was found to be 0.9632 which was very close to the “Adjusted R2 value, i.e.0.9901. Also, the signal-noise ratio of the selected model was found to be 40.89 reflecting an adequate signal. Upon ANOVA treatment, the model terms of a quadratic equation were found to be significant with “p” values less than 0.0500. The influence of independent variables on zeta-potential is depicted in the following equation:

|

9 |

As per the above equation, the highest positive coefficient of A signifies the potential relation between the drug-nanoparticle ratio and zeta potential. This signifies that the surface charge of HAPNPs provides adequate repulsive force amongst particles to remain in dispersed form. Whereas negative coefficients of B and C indicate that a diluted medium and longer loading time may result in lower zeta-potential values. Moreover, the combined effect of these variables was not enormous as compared to their individual effects [Fig. 5 (a-c)].

Fig. 5.

Effect of Independent Variables on Zeta-Potential of DZHAPNPs.

Validation of the design of experiments

Following the experimental investigation, the numerical desirability function was used to calculate the optimum formulation variables using the relevant numerical and graphical optimization tools found in the optimization portion of design expert software47. The most fitted values and the combination of independent variables were experimentally replicated in triplicate to validate the design38. Finally, the pH of calcium and phosphate precursors in the synthesis of HAPNPs was selected to be 11–12 and the dilution factor chosen was 0.6. However, in DZHAPNPs, the final ratio of HAPNPs to DZ was selected 2, dispersion volume 50 mL, and loading time 20 h. The desirability values were found to be 0.702 and 0.814 for DZHAPNPs and HAPNPs respectively [Fig. 6 (a-b)]. Since the values are very close to 1, it signifies that optimized conditions are very well aligned with the statistical analysis. Also, the overlay plots demonstrated the design space flexibility, and all the dependent variables were found to be within the boundaries of the design space [Fig. 6 (c-d)]. The optimized formulation proceeded for further characterization.

Fig. 6.

Model Validation Graphs (a-b) Desirability for HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs and (c-d) Design Space plots for HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs.

In vitro characterization of blank HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs

FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectrum (Fig. 7A) of diadzein revealed a sharp peak at 3222.47 cm−1 depicting the phenolic O-H stretching vibrations. However, the peaks obtained at 3025.76 cm−1, 2959.23 cm−1, 2896.59 cm−1, 2885.81 cm−1, 2694.07 cm−1 and 2489.65 cm−1 represented characteristic C-H stretching vibrations. Also, characteristic peaks at 1630.52 cm−1 and 1000 cm−1 were identified, which represented C = O stretching vibrations and the presence of a phenyl ring in diadzein. In addition, other intense peaks at 1595.81 cm−1, 1459.85 cm−1, 1387.53 cm−1 and 1306.57 cm−1 represented C = C and C-C stretching.

Fig. 7.

FTIR spectra of (A) DZ, (B) HAPNPs, (C) Powder-Mix of DZ and HAPNPs (1:1), and (D) DZHAPNPs.

The presence of both OH and H2O groups was confirmed by the peaks found at 1639 cm-1 and 3444 cm-1 in the FTIR spectrum of synthesized HAPNPS (Fig. 7B). Additionally, the distinctive peaks seen in the range of 550 cm−1 to 1100 cm−1 of the spectrum (1090 cm−1, 1031 cm−1, 961 cm−1, 602 cm−1, and 562 cm−1) were P-O stretching vibrations that are found in the phosphate group. Furthermore, the spectra of HAPNPs showed the presence of C-O stretching bands in the range of 1445 to 1422 cm−1 as well as O-H stretching peaks at 632 cm−1 and 3575 cm−1. To establish the compatibility between DZ and HAPNPs, FTIR of powder mix of DZ and HAPNPs (Fig. 7C) and drug-loaded nanoparticles (DZHAPNPs) (Fig. 7D) was performed. In the nanoparticle spectra, no shift in characteristic peaks of HAP and daidzein was observed. All major functional groups of DZ (phenolic, carboxylic, and aromatic ring) and HAP (hydroxyl, carbonate, and phosphate) were vigilant. However, in the spectra of DZHAPNPs (Fig. 7d), the presence of the DZ peaks was diminished suggesting the successful entrapment of the drug on HAPNPs.

Particle size, PDI and zeta potential

The particle size of both HAPNPs (Fig. 8a) and DZHAPNPs (Fig. 8b) was found to be 115.9 ± 0.15 nm and 129.3 ± 0.65 nm respectively, within desired size range (below 200 nm), whereas the PDI values of both, blank and drug-loaded nanoparticles were found to be below 30% revealing a uniform distribution of particles upon dispersion. From the size of DZHAPNPs, it was observed that there was no remarkable increment in size upon drug loading. This signifies that the synthesized HAPNPs were hollow with a large specific surface area and despite being adsorbed over the surface only the drug has penetrated the deep crevices of HAPNPs. Similar surface characteristics of HAPNPs were observed and reported by31. These findings are very much corroborated by FESEM and XRD results.

Fig. 8.

(a-b) Particle Size and PDI of HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs and (c-d)Zeta-Potential of HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs.

The zeta potential is a stability-indicating parameter for all nano-formulations in dispersed form. It represents the electrostatic barriers that can prevent the agglomeration and aggregation of the nanoparticles and is a crucial indicator of the physical stability of colloid dispersion systems.

The Zeta potential of HAPNPs, (Fig. 8c) and DZHAPNPs (Fig. 8d) was found to be −22.3 mV and − 20.9 mV respectively, which is in agreement with the desirable limits (close to ± 30) indicating that the prepared NPs colloidal dispersion was stable and devoid of aggregation and settling.

Drug entrapment and loading

A maximum drug entrapment of 87.22 ± 0.97% was obtained in an optimized formulation having HAPNPs and DZ in the ratio of 2:1. The drug loading calculated for the same batch was found to be 35.71 ± 0.25%. The reason for such a high payload of drugs over HAPNPs is their high porosity and surface area. The FESEM images of HAPNPs depict the pores and crevices confirming the speculation.

FESEM and TEM

FESEM images of daidzein, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs illustrated their morphology i.e. shape, size, and surface features. The irregular rod-shaped crystals of diadzen were identified in Fig. 9a whereas in Fig. 9b a porous hexagonal nanocrystals of hydroxyapatite were observed. Furthermore, Fig. 9c depicts the irregular (small spheroidal or pseudohexagonal) drug-loaded DZHAPNPs, in which the cracks and crevices on the surface of DZHAPNs can be easily identified. This further confirms the penetration of the drug deep down from the surface of HAPNPs. These morphological characteristics of DZHAPNPs and the concept of drug penetration in nano-pores can be corroborated with the findings of Munir and his co-workers et al. 201831. The average size of HAPNPs was found to be in the range of 100 ± 30 nm whereas drug-loaded DZHAPNPs exhibited an average size range of 100 ± 50 nm.

Fig. 9.

(a-c): FESEM images of diadzein, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs. (d) TEM images of DZHAPNPs.

From TEM images of DZHAPNPs (Fig. 9d), the shape and size of drug-loaded nanoparticles were reconfirmed complying with the results of FESEM and DLS.

X-Ray diffraction

Crystallinity and polymorphism of the drug and developed formulations were determined by Powder X-ray diffraction. The existence of crystal phases in spectra of DZ and HAPNPs has already been iterated in the literature. The intense peaks at 2Ɵ value in the range of 30° to 50° are characteristic crystalline peaks for hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (Fig. 10b), whereas the peaks below 30° i.e. 6.9°, 8.5°, 10.4°, 12.9°, 15.9°, 17.0°, 24.6°, 25.3°, 26.5°, 28.1°, and 28.8° (Fig. 10a) represent diadzein crystals. The XRD spectra of DZ and HAPNPs confirm their standard data for existence in the crystalline phase.

Fig. 10.

XRD spectra of (a) Diadzein (b) HAPNPs (c) DZHAPNPs.

However, upon thorough investigation, it was observed that the peaks in the XRD spectra of DZHAPNPs (Fig. 10c), were diminished compared to HAPNPs. This reduced intensity of peaks indicates drug entrapment. Further, it was observed that characteristic intense peaks of DZ (below 30°) were missing in the spectra of DZHAPNPs, signifying less or no availability of free drug on its surface. Interestingly, upon calculation, it was found that the crystallinity of DZHAPNPs was reduced (56%) compared to HAPNPs (88%), which is a clear sign of amorphization of DZ.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The TGA graph of DZ (Fig. 11), demonstrates a significant % weight loss upon temperature elevation. The reported melting point of DZ is 350 °C, therefore it started to decompose around 340–350 °C, and a characteristic endothermic peak in the TGA graph was obtained48.

Fig. 11.

TGA analysis of Diadzein, HAPNPs, and DZHAPNPs.

Further, from the TGA analysis of HAPNPs, it was observed that upon heating up to 900 °C, no endothermic peak was obtained and the percent weight loss with temperature elevation was also found to be very minimal (only 1–2%). This could be the result of physically adsorbed water being removed from the nanoparticles’ surface, indicating the HAPNPs’ thermal stability at high temperatures37. In contrast, the TGA graph of DZHAPNPs illustrated a distinct thermal stability of the nano-formulation. As apparent, in the TGA graph of DZ, the drug decomposes near its melting point, and a sharp endothermic peak was obtained at 350 °C. However, in the TGA graph of DZHAPNPs, no decomposition of the drug was observed around 350 °C, and no endothermic peak was obtained. Further, the % weight loss calculated for DZHAPNPs was also found to be minimal (below 3%). From this, it can be deduced that the drugloaded over HAPNPs was entrapped in pores and crevices majorly rather being adsorbed on the surface.

Drug release and release kinetics

The release study was performed for two optimized batches of DZHAPNPs (comprising drug and nanoparticles in ratios of 1:2 and 1:3) and was compared with drug (DZ) suspension. The study was conducted in phosphate buffer solutions (PBS) simulating the pH of blood (7.4) and pH in the vicinity of bones (6.8). The in-vitro release profiles of the drug in phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and pH 6.8 are illustrated in Fig. 12 (a) and (b), respectively. The cumulative percent drug release from DZHAPNPs (1:2) was found at pH 6.8 and 7.4 i.e. 85.5 ± 0.69 and 91.13 ± 0.85% respectively up to 96 h. Upon close monitoring, it was observed that the formulations at either pH exhibited an initial burst release within two hours of dissolution. However, with time progression, a sustained release pattern was attained. This suggests that DZHAPNPs exhibited a biphasic drug release profile, with a rapid release of the drug that was been adsorbed on the surface or was free at first, and a longer release of the drug that was been deeply penetrated.

Fig. 12.

Dissolution Studies in (a) PBS 7.4 and (b) PBS 6.8.

To comprehend the drug release process, the dissolution data underwent analysis using multiple kinetic models, including Zero Order, First Order, Higuchi, Hixson-Crowell, and Korsmeyer-Peppas. Plotting a graph between time and the fraction of cumulative drug release, the rate constant for drug dissolution and Correlation coefficient (R2) was calculated for each model ( Supplementary Figure S2 and Table S5). The best-fit model to explain the release was found to be a zero-order model wherein K0(0.948) and adjusted R2value (0.9900) were found to be maximum amongst all other models. Furthermore, the Korsemeyer-Peppas model was used to calculate the diffusion exponent “n” to validate the drug release mechanism during the sustained-release phase (linear portion of the curve). As per the Korsemeyer-Peppas model, the value of “n” denotes the dissolution site’s transport mechanism. Specifically, for Fickian diffusion, “n” must be smaller than 0.43. If it falls between 0.43 and 0.85, it suggests anomalous transport. However, for zero-order ( Case II transport) the “n” value should be above 0.8. The obtained diffusion constant values for two batches of DZHAPNPs were found to be 1.02 and 1.17 respectively, clearly indicating the zero order release pattern of the formulation.

Stability studies

The DZHAPNP stability investigations were carried out for six months under accelerated storage settings in accordance with ICH recommendations. To do this, the nanoparticle samples were stored at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C. They were then periodically tested (0, 1, 3, and 6 months) for any notable changes in their physical appearance, particle size, drug content, and shift in the drug’s λmax (Fig. 13).

The physical appearance of the samples of DZHAPNPs, kept at different accelerated conditions was monitored at regular intervals and no change was observed till the end of the study. At regular intervals, the particle sizes of all the samples maintained at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C were assessed, and the percentage of change in particle size relative to the initial (Day 01) was computed. After six months of study, it was discovered that the samples’ percentage increases in particle size were 1.2%, 3.2%, and 5.7% at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively. Since the percent increase in particle size of samples was found to be below 10%, hence can be considered negligible49.

Also, the drug content of DZHAPNPs, kept at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C was evaluated at regular intervals and the percent change in drug content concerning initial (Day 01) was calculated. At the end of the study (after six months), the percent decrease in drug content of the samples was found to be 3.4%, 5.5%, and 8.9% at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C, respectively. The loss in drug content at 4 °C and 25 °C was comparatively lesser, however at 40 °C, a noticeable loss (p< 0.05) was observed. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that NPs preparations are best stored for an extended period under refrigeration and room settings (25 ± 2 °C/60 ± 5% RH)50. Further, the shift in λmax of the drug was monitored for all of the DZHAPNPs samples kept at 4 °C, 25 °C, and 40 °C for six months. The λmax observed for the samples at the end of the study was found to be 253.6 ± 0.17 nm, 250.53 ± 0.27 nm, and 249.5 ± 0.13 nm, respectively. Although a shift in λmax of the drug was observed compared to the initial (Day 01), however it was found to be within the reported λmax range of daidzein (245–254 nm) and therefore can be ignored.

Fig. 13.

Stability study of DZHAPNPs at (a) 4 °C, (b) 25 °C, and (c) 40 °C.

Since the results elicited no significant change in any of the parameters (p > 0.05) at normal conditions, therefore we can conclude that our formulation exhibits excellent stability in terms of its physical appearance, particle size, λmax, and drug content. The findings of the stability study of the present research are in very much agreement with the stability of HAP-based nanoformulation developed by Ain et al.38.

Haemolytic activity

Before performing in-vivo studies, in-vitro haemolysis study is always recommended to estimate the drug’s and carrier’s compatibility with blood components. In line with this, the % haemolysis was estimated as per the method described above in “method” section. The percent haemolysis of DZ, DZHAPNPs, and HAPNPs was found to be 0.98 ± 0.14%, 1.01 ± 0.32%, and 0.73 ± 1.5% respectively. Since the % haemolysis by each sample was less than 10%, thus can be considered insignificant40. From this, it can be construed that the drug and formulations are non-haemolytic and biocompatible with blood cells.

In vivo pharmacokinetic study

HPLC method validation

The adopted HPLC method for PK studies of daidzein in rat plasma samples was validated and reproduced as per ICH guidelines. The details for method validation and HPLC chromatograms have been provided in a supplementary file for reference. After validation, linearity of DZ was established in plasma samples in the concentration range of 0.5–20 µg/mL. The concentration of the DZ-spiked plasma sample (µg/mL) was plotted against the peak areas (mAu) of the spiked plasma samples to construct a calibration curve (Supplementary Figure S4). Peak areas and the concentration of spiked plasma samples showed a strong linear association (with regression coefficient R2 = 0.9997), according to the equation derived from regression analysis (y = 23935x + 34718).

Pharmacokinetic study

The HPLC method used to ascertain the various pharmacokinetic parameters following the administration of a single dose of daidzein solution (10 mg/kg) and an equivalent quantity of DZHAPNPs intravenously injected into rats was effectively verified and optimized. The plasma samples were prepared and treated for HPLC analysis after being drawn at different time intervals. Figure 14 shows the mean plasma concentration of the drug vs. time graph for drug solution (DZ) and DZHAPNPs. Further, upon non-compartmental analysis of the graph and utilizing the PK-solver add-in program, various PK parameters were calculated and summarized in Table 4. From the result analysis of PK-data, the values of AUC0–∞ of DZHAPNPs were found to be 7247.666749 µg/mL*h which was significantly higher (almost 3 fold) than that of daidzein solution i.e. 2299.734755 µg/mL*h. Thus, higher AUC0−∞ of DZHAPNPs, confirms the increased bioavailability of drug-loaded nanoparticles, compared to free drug, eliminating faster from the system. However, the Cmax of daidzein solution (381.5991728 µg/mL) was found to be higher as compared to DZHAPNPs (372.0870357 µg/mL), indicating faster availability of the drug in blood upon administration. Furthermore, the t1/2 value of DZHAPNPs was also found to be maximal (12.3505404 h) in comparison to the drug solution (3.447192323 h), which is a clear sign of the long stay of the drug in the body. In addition, a higher tmax (12 h) and mean residence time (MRT) (20.06345042 h) of DZHAPNPs signify that the drug-loaded nanoparticles are long-circulating and reside in the body for a longer duration.

Fig. 14.

Plasma Concentration versus Time Profile of DZ and DZHAPNPs.

Table 4.

In vivo pharmacokinetic parameters of DZ and DZHAPNPs (mean ± SD, n = 6).

| Parameter | DZ-Solution | DZHAPNPs |

|---|---|---|

| Tmax (hr) | 01 ± 0.78 | 12 ± 0.93 |

| C max (µg/mL) | 381.59 ± 1.12 | 372.08 ± 1.2 |

| AUC0−∞ (µg/mL*h) | 2299.73 ± 0.67 | 7247.66 ± 0.58 |

| MRT 0−∞ (hr) | 2.97 ± 0.95 | 20.063 ± 0.83 |

| t1/2 (hr) | 3.44 ± 0.44 | 12.35 ± 0.39 |

Where, AUC0−∞: area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time = zero to time = infinity, Cmax: maximum plasma concentration, tmax: time to reach maximum plasma concentration, t1/2: elimination half-life.

Conclusion

Neoteric trends of innovative formulation development are focussing precisely on cutting down the perilous effects of synthetic hormonal therapy in menopausal women. In recent years, different formulations have evaluated different soy-isoflavones like daidzein, genistein, and equol to overcome hormonal deficiency in menopausal women. Besides prescribing nutraceuticals, various greener strategies have been evolved to synthesize and prepare novel formulations for postmenopausal symptoms including osteoporosis. In line with this, the present research aimed to develop a formulation of natural origin wherein a phytoestrogen (soy isoflavone-Diadzein) was loaded on biocompatible nanoparticles of hydroxyapatite. HAP is a bioceramic constituent of bone and thus a self-targeted carrier. Therefore, DZ being loaded over HAPNPs will combat hormone deficiency in menopausal women by mimicking the role of natural estrogen as well as promote biomineralization. Hypothesizing this bimodal approach to the treatment of PMO, daidzein-loaded HAP nanoparticles were synthesized. The formulation development and characterization results confirmed the successful development of nano-sized HAPNPs and DZHAPNPs. The results of in vitro drug release have brought forth a desirable release pattern of DZHAPNPs for 90 h thereby reducing the dose and dosing frequency of such potent isoflavones. In addition, the results of XRD and TGA confirmed the entrapment of the drug in deep pores of HAPNPs and potentiated their thermal stability as confirmed by stability studies. Also, from the results of the in vivo pharmacokinetic study, a long circulation pattern of DZHAPNPs was reconfirmed and IVIVC correlation was established. Moreover, the bioavailability of DZ was found by a 3-fold increase in DZHAPNPs as compared to free drug. Based on our findings, one could lead to an improvement in bone targeting of natural compounds, and consequently, the potential of other phytoestrogens can be evaluated in PMO.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Prof. Dr. P.A. is thankful to the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2025R945), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author contributions

N.G.: Conceptualization of the Research Work, Investigation, Methodology, Data Curation and Interpretation, Validation, and Writing of the Original Draft. S.T.: Study-Concept Design, Supervision, Review & Editing of the Manuscript, and Proofreading. S.P.V.: Guided in Pharmacokinetic Studies and HPLC Data Curation. S.M.: Formal Analysis, and Proofreading. D.D.: Helped in Animal-Handing and Pharmacokinetic Studies. P.A.: Funding acquisition and Resources. N.A.E.: Software and Formal analysis. M.H.A.: Validation and Visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available with the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

All animal experiments adhere to the ARRIVE guidelines and were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition). Approval from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee of Delhi Pharmaceutical Science and Research University, Delhi (Approval No. IAEC/2023/II-09) was taken before the commencement of animal studies.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Suraj Pal Verma, Email: surajpal_1982@yahoo.co.in.

Sushama Talegaonkar, Email: stalegaonkar@dpsru.edu.in.

References

- 1.Taebi, M., Abdolahian, S., Ozgoli, G., Ebadi, A. & Kariman, N. Strategies to improve menopausal quality of life: a systematic review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 7, 93 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monteleone, P., Mascagni, G., Giannini, A., Genazzani, A. R. & Simoncini, T. Symptoms of menopause - Global prevalence, physiology and implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology vol. 14 199–215 Preprint at (2018). 10.1038/nrendo.2017.180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Pop, A. L. et al. The Current Strategy in Hormonal and Non-Hormonal Therapies in Menopause—A Comprehensive Review. Life vol. 13 Preprint at (2023). 10.3390/life13030649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sourouni, M. & Kiesel, L. Hormone Replacement Therapy after Gynaecological Malignancies: A Review Article. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde vol. 81 549–554 Preprint at (2021). 10.1055/a-1390-4353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cagnacci, A. & Venier, M. The controversial history of hormone replacement therapy. Medicina (Lithuania) vol. 55 Preprint at (2019). 10.3390/medicina55090602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Ragaz, J. & Budlovsky, J. Hormone replacement therapy: A critical review. in Management of Breast Diseases 451–470Springer Berlin Heidelberg, (2010). 10.1007/978-3-540-69743-5_24

- 7.Fait, T. Menopause hormone therapy: Latest developments and clinical practice. Drugs in Context vol. 8 Preprint at (2019). 10.7573/dic.212551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Akter, N., Kulinskaya, E., Steel, N. & Bakbergenuly, I. The effect of hormone replacement therapy on the survival of UK women: a retrospective cohort study 1984 – 2017. BJOG129, 994–1003 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mora-Raimundo, P. & Manzano, M. Vallet-Regí, M. Nanoparticles for the treatment of osteoporosis. AIMS Bioeng.4, 259–274 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busayapongchai, P. & Siri, S. Estrogenic receptor-functionalized Magnetite nanoparticles for Rapid separation of Phytoestrogens in Plant extracts. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol.181, 925–938 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tella, S. H. & Gallagher, J. C. Prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology vol. 142 155–170 Preprint at (2014). 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Chen, L. R. & Chen, K. H. Utilization of isoflavones in soybeans for women with menopausal syndrome: An overview. International Journal of Molecular Sciences vol. 22 1–23 Preprint at (2021). 10.3390/ijms22063212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Singh, S. et al. Unveiling the Pharmacological and Nanotechnological Facets of Daidzein: Present State-of-the-Art and Future Perspectives. Molecules vol. 28 Preprint at (2023). 10.3390/molecules28041765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Chen, L. R., Ko, N. Y. & Chen, K. H. Isoflavone supplements for menopausal women: A systematic review. Nutrients vol. 11 Preprint at (2019). 10.3390/nu11112649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Al-Anazi, A. F., Qureshi, V. F., Javaid, K. & Qureshi, S. Preventive effects of phytoestrogens against postmenopausal osteoporosis as compared to the available therapeutic choices: An overview. Journal of Natural Science, Biology and Medicine vol. 2 154–163 Preprint at (2011). 10.4103/0976-9668.92322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Słupski, W., Jawień, P. & Nowak, B. Botanicals in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Nutrients vol. 13 Preprint at (2021). 10.3390/nu13051609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Kim, M. et al. Understanding the functional role of genistein in the bone differentiation in mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 by RNA-seq analysis. Sci. Rep.8, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Bhalla, Y., Chadha, K., Chadha, R. & Karan, M. Daidzein cocrystals: an opportunity to improve its biopharmaceutical parameters. Heliyon5, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jia, J. et al. Daidzein alleviates osteoporosis by promoting osteogenesis and angiogenesis coupling. PeerJ11, (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Strong, A. L. et al. Design, synthesis, and osteogenic activity of daidzein analogs on human mesenchymal stem cells. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.5, 143–148 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahsan, M. & Mallick, A. K. The effect of soy isoflavones on the menopause rating scale scoring in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a pilot study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res.11, FC13–FC16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang, Q., Liu, W., Wang, J., Liu, H. & Chen, Y. Preparation and Pharmacokinetic Study of Daidzein Long-Circulating Liposomes. Nanoscale Res. Lett.14, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Al-allaq, A. A. & Kashan, J. S. A review: in vivo studies of bioceramics as bone substitute materials. Nano Select. 4, 123–144 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galindo, T. G. P., Chai, Y. & Tagaya, M. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticle coating on polymer for constructing effective biointeractive interfaces. J Nanomater (2019). (2019).

- 25.Vallet-Regí, M. Bioceramics: from bone substitutes to nanoparticles for drug delivery. Pure Appl. Chem.91, 687–706 (2019). 10.1515/pac-2018-0505 Preprint at. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gautam, N., Kulkarni, A., Dutta, D. & Talegaonkar, S. Pharmacokinetics of long circulating inorganic nanoparticulate drug delivery systems. in Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Nanoparticulate Drug Delivery Systems 187–208Springer International Publishing, (2022). 10.1007/978-3-030-83395-4_10

- 27.Neupane, Y. R. et al. Biocompatible Nanovesicular Drug Delivery systems with Targeting potential for Autoimmune diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des.26, 5488–5502 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senra, M. R., de Lima, R. B., Souza, D., de Marques, H. S., Monteiro, S. N. & F. V. & Thermal characterization of hydroxyapatite or carbonated hydroxyapatite hybrid composites with distinguished collagens for bone graft. J. Mater. Res. Technol.9, 7190–7200 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gautam, N. et al. Springer Nature Singapore,. Functionalized Lipidic Nanoparticles: Smartly Engineered Lipidic Theragnostic Nanomedicines. in Multifunctional And Targeted Theranostic Nanomedicines 119–144 (2023). 10.1007/978-981-99-0538-6_6

- 30.Thomas, S. C., Mishra, K. & Talegaonkar, S. P. Send orders for reprints to Reprints@benthamscience.Ae ceramic nanoparticles: fabrication methods and applications in drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Design21 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Munir, M. U. et al. Hollow mesoporous hydroxyapatite nanostructures; smart nanocarriers with high drug loading and controlled releasing features. Int. J. Pharm.544, 112–120 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tripathi, G., Raja, N. & Yun, H. S. Effect of direct loading of phytoestrogens into the calcium phosphate scaffold on osteoporotic bone tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B. 3, 8694–8703 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, H. et al. Development of daidzein nanosuspensions: Preparation, characterization, in vitro evaluation, and pharmacokinetic analysis. Int. J. Pharm.566, 67–76 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madhavasarma, P., Veeraragavan, P., Kumaravel, S. & Sridevi, M. Studies on physiochemical modifications on biologically important hydroxyapatite materials and their characterization for medical applications. Biophys. Chem.267, (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Ugur Kaplan, A. B. et al. Formulation and in vitro evaluation of topical nanoemulsion and nanoemulsion-based gels containing daidzein. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol.52, 189–203 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uğur Kaplan, A. B., Öztürk, N., Çetin, M., Vural, I. & Özer, T. Ö. The Nanosuspension formulations of Daidzein: Preparation and in Vitro characterization. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci.19, 84–92 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai, Z. et al. Large-scale and fast synthesis of nano-hydroxyapatite powder by a microwave-hydrothermal method. RSC Adv.9, 13623–13630 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ain, Q. U. et al. QbD-Based fabrication of Biomimetic Hydroxyapatite embedded gelatin nanoparticles for localized drug delivery against deteriorated arthritic Joint Architecture. Macromol. Biosci.24, 1–18 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu, G. et al. Preparation of Daidzein microparticles through liquid antisolvent precipitation under ultrasonication. Ultrason. Sonochem79, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.von Petersdorff-Campen, K. & Daners, M. S. Hemolysis Testing In Vitro: A Review of Challenges and Potential Improvements. ASAIO Journal vol. 68 3–13 Preprint at (2022). 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Demirtürk, E. et al. Assessment of Pharmacokinetic parameters of Daidzein-containing nanosuspension and nanoemulsion formulations after oral administration to rats. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet.47, 247–257 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao, X., Shen, Q. & Ma, Y. An HPLC method for the pharmacokinetic study of daidzein-loaded nanoparticle formulations after injection to rats. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci.879, 113–116 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rawat, P. et al. Revisiting bone targeting potential of novel hydroxyapatite based surface modified PLGA nanoparticles of risedronate: pharmacokinetic and biochemical assessment. Int. J. Pharm.506, 253–261 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pandey, S. et al. Design and development of bioinspired calcium phosphate nanoparticles of MTX: pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic evaluation. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm.45, 1181–1192 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mittal, S., Ali, J. & Baboota, S. Enhanced anti-psoriatic activity of tacrolimus loaded nanoemulsion gel via omega 3 - fatty acid (EPA and DHA) rich oils-fish oil and linseed oil. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol.63, (2021).

- 46.Ashhar, M. U., Kumar, S., Ali, J. & Baboota, S. CCRD based development of bromocriptine and glutathione nanoemulsion tailored ultrasonically for the combined anti-parkinson effect. Chem. Phys. Lipids235, (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Ghose, D. et al. QbD-based formulation optimization and characterization of polymeric nanoparticles of cinacalcet hydrochloride with improved biopharmaceutical attributes. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci.18, 452–464 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan, H. et al. A superior preparation method for daidzein-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin complexes with improved solubility and dissolution: supercritical fluid process. Acta Pharm.67, 85–97 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weng, J., Tong, H. H. Y. & Chow, S. F. In vitro release study of the polymeric drug nanoparticles: development and validation of a novel method. Pharmaceutics12, 1–18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emad, N. A. et al. Polyphenols-loaded beeswax-based lipid nanoconstructs for diabetic foot ulcer: optimization, characterization, in vitro and ex vivo evaluation. J. Drug Deliv Sci. Technol.88, 104983 (2023). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available with the corresponding author on reasonable request.