Abstract

Academic procrastination is one of the major factors that can be a serious obstacle for students to achieve academic progress and success. This research aimed to investigate and predict academic procrastination based on academic self-efficacy and emotional regulation difficulties of students of one of the medical sciences universities in southern Iran in 2024. This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted on 290 students of different fields in the south of Iran between January and April 2024. Data was collected using standard questionnaires of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in emotional regulation. Descriptive statistics, t-test, ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and multiple linear regression were employed to examine the data using SPSS 23 software. A significant level of 0.05 was considered. The average score of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in emotional regulation of the studied students was 66.21 ± 4.06 (out of 108), 59.58 ± 5.84 (out of 120), and 121.42 ± 6.88 (out of 180), respectively, which indicates a moderate level of academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination and a high level of difficulty in emotional regulation. A statistically significant correlation was observed between students’ academic procrastination and academic self-efficacy (r = -0.648, p < 0.001) and the difficulty in emotional regulation (r = 0.701, p < 0.001). Based on the results of multiple linear regression, components of academic self-efficacy, including effort, talent, and context, as well as components of difficulty in emotion regulation, including difficulty in performing purposeful behavior, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotional regulation strategies, non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty in impulse control, and lack of emotional clarity, were identified as predictors of academic procrastination (p < 0.05). Considering the students’ academic procrastination and the effect of academic self-efficacy and difficulty in emotional regulation on it, it is suggested that university administrators provide the field of improvement and promotion of students’ academic self-efficacy and emotional regulation through holding related courses and workshops so that in this way procrastination can be reduced.

Keywords: Academic procrastination, Academic self-efficacy, Emotion regulation, Student, Iran

Subject terms: Psychology, Health care, Health occupations

Introduction

As students continue their education, they mature and develop in the face of academic, personal, and social challenges. Academic procrastination is a notable difficulty that students often encounter in contemporary times1. Academic procrastination is a recurring behavior in students’ educational advancement, characterized by the tendency to postpone or delay the completion of homework and required tasks even when there is a specified deadline1,2. Additionally, academic procrastination is the conscious delay of required tasks3. This behavior is a self-defeating behavior that is becoming more prevalent in modern society. It occurs when people delay doing what they want to do, potentially leading to loss of productivity, poor performance, and increased stress4. Procrastinating within an academic environment yields unfavorable outcomes like stress, guilt, unsatisfactory academic results, and decreased self-esteem, negatively influencing learning and academic success5. Studies reveal that procrastination is a behavior observed in 80–95% of students, and there is a growing trend of this conduct among student cohorts6. The study conducted by Tavakoli (2013) in Iran revealed that 84% of the 600 students demonstrated academic procrastination at different levels7.

The prevalence of academic procrastination among students is worrying because it causes them to postpone their educational activities, leading to poor academic progress, physical and anxiety problems, disorganization, confusion, and lack of responsibility8. According to specialists, inadequate management of academic procrastination can lead to diminished self-confidence, a negative approach to learning, feelings of depression, an increase in unhealthy behaviors, and a decline in the quality of sleep6,7. As a result of the detrimental effects, exploring and predicting academic procrastination is essential to facilitate necessary interventions3.

Students’ academic procrastination can be affected by various personal and academic elements. One of these factors is academic self-efficacy9–11. In this regard, Early theories on procrastination, including expected value theory12, time motivation theory (TMT)13, and the two-dimensional time-oriented model14, highlight the influence of self-efficacy as a motivational element on procrastination behavior. Self-efficacy involves individuals’ perceptions of their ability to finish a given task15. Academic self-efficacy represents a specific type of self-efficacy, reflecting students’ evaluations of their skills and capabilities to perform tasks essential for reaching established educational objectives16. In other words, what learners believe about their abilities in the learning process is defined as academic self-efficacy, which is based on Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy beliefs17. Several studies have demonstrated a negative association between academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination18–20. Research carried out in Iran revealed that academic self-efficacy played a crucial role in reducing academic stress and procrastination while enhancing academic achievement21. In a separate study, Tamadoni et al. (2010) pointed out the impact of academic self-efficacy on predicting academic procrastination10.

According to the results of some studies, one of the other factors that can affect students’ academic procrastination is emotional regulation difficulties22,23. Emotion regulation comprises diverse strategies for overseeing and altering the frequency, intensity, and duration of emotional reactions, as well as communicating a wide range of emotions, particularly in the context of behavior directed toward goals24. According to specialists, a variety of emotional difficulties often correlate with problems in managing emotions effectively25. In this regard, procrastination is considered ineffective and emotional self-regulation26 because people who procrastinate do not consider themselves capable of changing the situation, and instead of focusing on work, they focus on their feelings and emotional reactions, which leads to postponing work27,28. In addition, Menbari et al. (2023) showed in research that difficulty in regulating emotions by students is related to self-harming behaviors, academic procrastination, and cheating29. In this regard, students seem to postpone their tasks and assignments due to a lack of access to adaptive emotional regulation strategies and to failure in self-regulation1. Therefore, in addition to improving their quality of life, having the skill of emotion regulation can play an essential role in improving their academic status and reducing their procrastination30. Studies indicate that effective emotional regulation enhances the quality of relationships between students and teachers, which in turn boosts academic motivation and achievement30,31.

Despite academic self-efficacy and emotional regulation difficulties being identified as factors contributing to procrastination in earlier studies, there is a lack of research specifically examining this phenomenon among students in medical sciences universities. Also, since medical science students play a very important role as future providers of health services, it is very important to measure their academic procrastination and the factors that affect the occurrence of this phenomenon. Therefore, this study was conducted to investigate and predict academic procrastination based on academic self-efficacy and difficulty in emotional regulation among students of one of the universities in southern Iran in 2024.

The findings of this study, while helping to expand knowledge about the investigated variables in the academic field, increase the knowledge of higher education managers and policymakers about the state of academic procrastination and its prediction based on academic self-efficacy and the difficulty in emotional regulation in the student community. Also, according to the main goal of this research, the findings can be the basis for planning to control and manage students’ academic procrastination.

Methods

Design and setting

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted on students from a medical sciences university in southern Iran during the period from January to April 2024.

Participants

The study population consisted of students from the university under investigation, including students from the Faculty of Medicine (Medical Sciences), the Faculty of Nursing (Nursing and Midwifery), the Faculty of Health (Public Health and Environmental Health), and the Faculty of Paramedical Sciences (Laboratory Sciences, Surgical Technologist, and Anesthesia).

Based on the population size (1136 individuals) and the following formula, considering a 95% confidence level, a 5% margin of error, p = q = 0.5, and z = 1.96, the sample size was calculated to be 290 participants.

According to the number of the total population under investigation, which was 1136 people, and by dividing 290 by 1136 and multiplying the obtained number by the number of students in each faculty, the necessary sample size was obtained in each faculty. In the table below, the names of the studied faculties, as well as the total number of students and the sample size in each faculty are mentioned separately (Table 1).

Table 1.

The size of the population and the examined sample by each faculty.

| Name of the faculty | Number of students (population size) | Sample size (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Medicine | 302 | 77 (26.55%) |

| Nursing and midwifery | 326 | 83 (28.62%) |

| Health | 215 | 55 (18.97%) |

| Paramedicine | 293 | 75 (25.86%) |

| Total | 1136 | 290 (100%) |

Also, in each faculty, based on the year of entry into the university and the field of study, a stratified sampling was conducted to determine the required sample size. Following the determination of sample sizes for each category and field of study, students were selected randomly based on their student numbers and a table of random numbers. Figure 1 shows the determination of the sample size separately for each faculty and field of study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Required sample by faculty and field of study.

The inclusion criteria were students studying in the second half of the 2022–2023 academic year, students who have completed at least two semesters of study, willingness to participate in the research, and not taking psychiatric drugs at least one month before the start of the study. The exclusion criteria included unwillingness to participate in the study, guest students, confusion or defects in completing the questionnaires, the student suffering from a physical illness that could be associated with academic procrastination, and the presence of seizures and neurological diseases (based on their medical records at the university’s student vice-chancellor).

Instruments

The data collection tool was a four-part questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire contains the demographic characteristics of age, gender, field of study, education level, marital status, place of residence, and employment status.

The second part was Solomon & Rothblum’s (1984) standard academic procrastination questionnaire. This questionnaire had 27 questions. In this questionnaire, there are 21 questions to measure three subscales, including procrastination in preparing assignments (9 questions), procrastination in studying for the exam (6 questions), and procrastination in writing a paper (6 questions). Also, there are 6 questions to measure the two characteristics of “not feeling uncomfortable about procrastinating” and “unwillingness to change the habit of procrastination”. The questions were assessed based on a 4-point Likert scale, with responses categorized as always, most of the time, rarely, and never, and scored from 4 to 1. For reverse questions, the scoring method was reversed (always (= 1) and never (= 4)). According to the score range of 27–108, the average score of 27-47.25, 47.26–67.50, 67.51–87.75, and 87.76–108 was considered as low, moderate, high, and very high academic procrastination, respectively32. The validity and reliability (with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.73) of this questionnaire have been confirmed in the study of Valizadeh et al. on Iranian students32.

The third part was the Morgan-Jinks (1999) Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. This questionnaire consists of 30 questions that measure academic self-efficacy in 3 dimensions, including effort (10 questions), talent (10 questions), and context (10 questions). To score this questionnaire, a 4-point Likert scale of completely agree (= 4), somewhat agree (= 3), somewhat disagree (= 2), and completely disagree (= 1) was used. For reversed questions, scoring was reversed (completely agree (= 1) and completely disagree (= 4)). Considering the score range of this questionnaire (30–120), students’ academic self-efficacy was classified into four categories: poor (30-52.5), moderate (52.6–75), good (75.1–97.5) and excellent (97.6–120)21. The validity and reliability of this questionnaire (with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient equal to 0.82) have been confirmed in the study of Jamali et al. on the student community in Iran21.

The fourth part is Gratz and Roemer’s standard emotion regulation difficulty questionnaire. This questionnaire has 36 items, including non-acceptance of emotional responses (6 items), difficulty in performing purposeful behavior (5 items), difficulty in impulse control (6 items), lack of emotional awareness (6 items), limited access to emotional regulation strategies (8 items), and lack of emotional clarity (5 items). The answers to the questions of this questionnaire were in the form of a five-point Likert scale (very rarely (score 1), occasionally (score 2), almost half of the time (score 3), most of the time (score 4) and almost always (score 5). In negative items, scoring will be reversed (score 1 for almost always and score 5 for very rarely). According to the range of scores from 36 to 180, the average score between 36 and 72 indicates difficulty in emotional regulation at a low level, the average score between 73 and 109 indicates difficulty in emotional regulation at a moderate level, and the average score between 110 and 145 indicates difficulty in emotional regulation at a high level, and the average score between 146 and 180 indicates difficulty in emotional regulation at a very high level33. Gratz and Roemer confirmed the validity and reliability of the emotional regulation questionnaire (with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80)33.

Procedure and statistical analysis

To collect data, after identifying the target students through the sampling method, and in coordination with the education department of the faculties regarding the schedule of their classes, one of the researchers (ARY) visited the targeted faculties on different days of the week, in both morning and afternoon sessions, to distribute and collect the questionnaires. The average time to complete each questionnaire was 30 min.

To ensure ethical considerations, students’ participation in the study and completing the questionnaires were voluntary. After explaining the study’s objectives to the participants, emphasis was placed on the confidentiality of their responses. Verbal consent was obtained from them, and the questionnaires were then distributed in person among the students under study and collected on the same day of distribution. Then, the collected data was entered into SPSS version 23 software.

Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to investigate the correlation between the variables of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and the difficulty of students’ emotional regulation, as well as the correlation of these three variables with the students’ age. A T-test was used to examine the difference in the average score of the three main research variables according to gender, marital status, place of residence, and employment status. ANOVA test was used to investigate the difference in the average score of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and the difficulty of students’ emotional regulation based on the variables of education level and field of study. Finally, multiple linear regression was used to investigate the simultaneous effect of the academic self-efficacy components and the difficulty of emotional regulation on students’ academic procrastination.

This study used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines34.

In order to minimize potential biases in the present study, several strategies were implemented. These included employing stratified random sampling, ensuring standardized interactions between data collectors and respondents, providing assurances regarding the confidentiality of participants’ information, conducting independent analyses of the results by a statistical consultant, eliminating researchers’ subjective judgments and preconceptions, and utilizing standardized, reliable, and valid questionnaires for data collection.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the university where the students were enrolled, with the approval code IR.JMU.REC.1402.051.

Results

The average age of the students participating in the study was 21.36 ± 6.45 years, and most of them (65.51%) were in the age group of 18–22 years. Most of the respondents were female (63.45%), single (82.42%), medicine students (26.55%), at the bachelor’s level (62.42%), and dormitory residents (64.48%). Also, 12.07% of students were employed (with a legitimate and independent source of income) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of studied students (n = 290).

| Variable | Details | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 18–22 | 190 | 65.51 |

| 23–27 | 81 | 27.93 | |

| 28–32 | 12 | 4.14 | |

| 32< | 7 | 2.42 | |

| Gender | Male | 106 | 36.55 |

| Female | 184 | 63.45 | |

| Marital status | Single | 239 | 82.42 |

| Married | 51 | 17.58 | |

| Education level | Associate degree | 32 | 11.03 |

| Bachelor | 181 | 62.42 | |

| Professional doctorate | 77 | 26.55 | |

| Field of study | Medicine | 77 | 26.55 |

| Nursing | 49 | 16.90 | |

| Midwifery | 31 | 10.69 | |

| Laboratory science | 24 | 8.27 | |

| Surgical technologist | 27 | 9.31 | |

| Anesthesia | 23 | 7.93 | |

| Public health | 19 | 6.55 | |

| Environmental health | 40 | 13.80 | |

| Place of residence | Dormitory | 187 | 64.48 |

| Non-dormitory | 103 | 35.52 | |

| Employment status | Employed | 35 | 12.07 |

| Unemployed | 255 | 87.93 |

According to the findings of Table 3, the mean and standard deviation of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in emotional regulation of the studied students were 66.21 ± 4.06 (out of 108), 59.58 ± 5.84 (out of 120), and 121.42 ± 6.88 (out of 180), respectively. It showed a moderate level of academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination and a high level of difficulty in students’ emotional regulation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation of academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in regulating emotions of the studied students.

| Variable | Dimensions | Score range | Average | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic procrastination | Procrastination in preparing assignments | 9–36 | 17.65 | 4.17 |

| Procrastination in studying for the exam | 6–24 | 16.43 | 3.45 | |

| Procrastination in writing a paper | 6–24 | 19.86 | 3.32 | |

| Not feeling uncomfortable about procrastinating | 3–12 | 6.36 | 2.86 | |

| Unwillingness to change the habit of procrastination | 3–12 | 5.91 | 3.74 | |

| Total | 27–108 | 66.21 | 4.06 | |

| Academic self-efficacy | Effort | 10–40 | 19.57 | 5.22 |

| Talent | 10–40 | 21.87 | 5.37 | |

| Context | 10–40 | 18.14 | 6.29 | |

| Total | 30–120 | 59.58 | 5.84 | |

| Difficulty regulating emotions | Non-acceptance of emotional responses | 6–30 | 18.24 | 4.12 |

| Difficulty in performing purposeful behavior | 5–25 | 21.48 | 3.55 | |

| Deficits in impulse control | 6–30 | 21.65 | 6.12 | |

| Lack of emotional awareness | 6–30 | 19.49 | 5.63 | |

| Limited access to emotional regulation strategies | 8–40 | 25.71 | 6.61 | |

| Lack of emotional clarity | 5–25 | 14.85 | 5.32 | |

| Total | 36–180 | 121.42 | 6.88 |

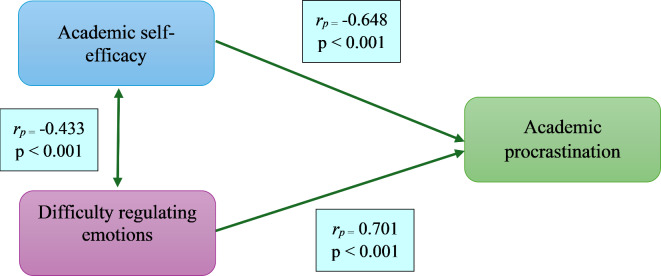

The findings of this study showed that there is a statistically significant correlation between the academic procrastination of students with academic self-efficacy (p < 0.001, r=-0.648) and the difficulty of emotional regulation (p < 0.001, r = 0.701) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in regulating emotions of the studied students.

To determine the simultaneous effect of different dimensions of academic self-efficacy and emotion regulation difficulties on the academic procrastination of students, the results of multiple linear regression analysis showed that the significant variables in the model determined by the Enter method, in order of importance, were as follows: “effort, talent, and context” for the academic self-efficacy and “difficulty in performing purposeful behavior, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotional regulation strategies, non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty in impulse control, and lack of emotional clarity” for emotion regulation difficulties.

The β values for the influential variables, which indicate the priority of their impact on academic procrastination, are presented in Table 4. Furthermore, this analysis showed that the adjusted model determination coefficient (R2 Adjusted) for academic procrastination based on the variables of academic self-efficacy and difficulty in emotional regulation is 0.68 and 0.74, respectively. This means that 68% and 74% of the variation in the students’ academic procrastination scores can be explained by the variables in the model. These equations were obtained based on multiple regression analysis as follows:

Table 4.

Factors affecting students’ academic procrastination using multiple linear regression model.

| Variable | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficient β | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. error | ||||||

| Academic procrastination | Academic self-efficacy | – | Constant | 2.856 | 1.455 | – | 0.01 |

| X 1 | Effort | − 0.676 | 0.192 | − 0.653 | < 0.001 | ||

| X 2 | Talent | − 0.658 | 0.184 | − 0.647 | < 0.001 | ||

| X 3 | Context | − 0.634 | 0.179 | − 0.626 | < 0.001 | ||

| Emotional regulation difficulties | – | Constant | 2.121 | 1.327 | – | 0.02 | |

| X4 | Difficulty in performing purposeful behavior | 0.586 | 0.174 | 0.577 | < 0.001 | ||

| X 5 | Lack of emotional awareness | 0.581 | 0.166 | 0.571 | < 0.001 | ||

| X6 | limited access to emotional regulation strategies | 0.574 | 0.161 | 0.564 | < 0.001 | ||

| X 7 | Non-acceptance of emotional responses | 0.569 | 0.152 | 0.559 | < 0.001 | ||

| X 8 | Deficits in impulse control | 0.563 | 0.148 | 0.555 | 0.001 | ||

| X 9 | lack of emotional clarity | 0.558 | 0.143 | 0.547 | 0.001 | ||

|

|

Y: Academic procrastination of students. X1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9: variables affecting the academic procrastination of the studied students (Table 4).

Based on the findings of the study, the average score of students’ academic procrastination was significantly different based on the variables of gender (p = 0.002), education level (p = 0.004), and employment status (p = 0.01). In this way, the average score of academic procrastination in male students (67.08 ± 4.26 out of 108), associate education level (68.25 ± 4.11 out of 108), and employed (66.99 ± 4.37 out of 108) was higher than others. Also, the average score of students’ academic self-efficacy was significantly different based on the variables of gender (p = 0.03), education level (p = 0.01), field of study (p = 0.02) and employment status (p = 0.04). So the average score of academic self-efficacy in female students (60.81 ± 5.55 out of 120), in the professional doctorate level (61.27 ± 5.37 out of 120), non-employed (60.74 ± 5.61 out of 120), and medical students (61.27 ± 5.37 out of 120) is higher than others. Finally, the average score of the difficulty of students’ emotional regulation was significantly different based on the variables of gender (p = 0.04), marital status (p = 0.03), and education level (p = 0.02). The average score of emotional regulation difficulty of male students (122.43 ± 5.77 out of 180), single students (121.54 ± 6.58 out of 180), and associate education level students (122.62 ± 6.85 out of 180) was higher than that of others (Table 5).

Table 5.

The relationship between academic procrastination, academic self-efficacy, and difficulty in regulating emotions with the demographic variables of the studied students.

| Variable | Details | Academic procrastination | Academic self-efficacy | Difficulty regulating emotions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD (of 108) | P-value | Mean ± SD (out of 120) | P-value | Mean ± SD (from 180) | P-value | ||

| Age (years) | 18–22 | 65.56 ± 3.26 | 0.13 | 61.87 ± 5.93 | 0.11 | 121.14 ± 6.16 | 0.07 |

| 23–27 | 66.47 ± 4.11 | 58.83 ± 5.45 | 121.34 ± 7.39 | ||||

| 28–32 | 66.59 ± 3.62 | 58.69 ± 5.38 | 121.95 ± 6.68 | ||||

| 32 ˂ | 66.21 ± 3.50 | 58.93 ± 5.45 | 121.25 ± 6.52 | ||||

| Place of residence | Dormitory | 66.12 ± 4.12 | 0.08 | 60.21 ± 6.14 | 0.09 | 121.16 ± 6.71 | 0.23 |

| Non-dormitory | 66.30 ± 3.86 | 58.95 ± 5.17 | 121.68 ± 6.95 | ||||

| Gender | Male | 67.08 ± 4.26 | 0.002 | 58.35 ± 6.23 | 0.03 | 122.43 ± 5.77 | 0.04 |

| Female | 65.34 ± 3.52 | 60.81 ± 5.55 | 120.41 ± 7.11 | ||||

| Marital status | Single | 66.23 ± 4.26 | 0.10 | 59.48 ± 6.83 | 0.12 | 121.54 ± 6.58 | 0.03 |

| Married | 66.19 ± 3.74 | 59.68 ± 5.03 | 121.30 ± 7.24 | ||||

| Education level | Associate degree | 68.25 ± 4.11 | 0.004 | 57.15 ± 5.26 | 0.01 | 122.62 ± 6.85 | 0.02 |

| Bachelor | 66.37 ± 3.62 | 60.32 ± 6.29 | 121.35 ± 6.73 | ||||

| Professional doctorate | 64.01 ± 4.15 | 61.27 ± 5.37 | 120.29 ± 7.33 | ||||

| Field of study | Nursing | 65.42 ± 4.37 | 0.08 | 59.31 ± 5.14 | 0.02 | 120.42 ± 7.27 | 0.14 |

| Midwifery | 65.79 ± 4.28 | 59.01 ± 5.82 | 120.69 ± 6.65 | ||||

| Medicine | 64.01 ± 4.15 | 61.27 ± 5.37 | 120.29 ± 7.33 | ||||

| Laboratory science | 66.76 ± 4.31 | 58.28 ± 5.59 | 121.95 ± 7.34 | ||||

| Surgical technologist | 66.23 ± 4.17 | 58.68 ± 6.44 | 121.45 ± 6.32 | ||||

| Anesthesia | 67.40 ± 3.13 | 57.42 ± 5.37 | 122.42 ± 6.24 | ||||

| Public health | 66.39 ± 3.40 | 58.53 ± 5.46 | 121.72 ± 6.69 | ||||

| Environmental health | 67.68 ± 4.22 | 57.73 ± 5.76 | 122.42 ± 6.92 | ||||

| Employment status | Employed | 66.99 ± 4.37 | 0.01 | 58.42 ± 5.92 | 0.04 | 121.83 ± 6.64 | 0.15 |

| Unemployed | 65.43 ± 3.74 | 60.74 ± 5.61 | 121.01 ± 7.12 | ||||

Discussion

The findings of the study indicated that students generally exhibited moderate levels of academic procrastination. This part of the research findings is consistent with the results of Chehrzad et al. (2017)35, Tavakoli et al. (2013)7, Tamadoni et al. (2010)10, Duru and Balkis (2014)36, Lakshminarayan et al. (2013)37, Mortazavi et al. (2015)38, Nasri et al. (2013)8, and Tamannaifar et al. (2012)39. In explaining this finding, it can be stated that students who lack the skills to plan or evaluate their study time effectively may be prone to postpone their required daily tasks40. Also, the prevalence of procrastination among young people and students is an issue that is affected by various reasons, such as lack of academic motivation, psychological problems, and the difficulty of the educational field. It is imperative to employ scientific and principled strategies to deter students from procrastination, given the detrimental consequences associated with its widespread occurrence.

The findings of the study also showed that the academic self-efficacy of the studied students is at a moderate level. This aligns with studies by Mohammadi et al. (2019)15, Mirzaei-Alavijeh et al. (2018)41, Saadat et al. (2015)42 and Kazemi-Vardanjani et al. (2017)43. In contrast, Vahabi et al. (2017)44, Asghari et al. (2014)17, Rahimi (2014)45, Afra et al. (2024)46, Afra et al. 202247 and Ghasemi Guderzi et al. (2023)48, reported it as above moderate. The variation can be clarified by the different research communities, measurement tools for research variables, research timing, and social, economic, and cultural considerations in various research contexts. In explaining the results of this part of the research findings, it can be stated that probably the studied students estimated their ability to successfully achieve their educational goals at a moderate level. On the other hand, they may not have performed well in determining educational goals, creating strong cognitive mechanisms for acquiring knowledge, dealing with academic challenges, and resisting difficult conditions, which can affect students’ negative self-evaluations and academic performance49. Also, the result of this section can indicate that the studied students were students who did not use all their efforts when facing academic challenges and gave in to cheap solutions in a short period.

Another part of the study’s findings reveals a statistically significant correlation between students’ academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination but in an inverse relationship. This means that students who had better academic self-efficacy had less academic procrastination. Additionally, effort, talent, and context in academic self-efficacy were determined as strong negative predictors of students’ academic procrastination. These results are following the research conducted by Fatehi et al. (2012)9, Tamadoni et al. (2010)10, and Sheykhi et al. (2013)11. Furthermore, according to part of the findings of Ghadampour et al. (2015), a significant negative correlation was observed between the scores on the academic self-efficacy scale and the total scores of the procrastination scale and its subcomponents50. Research results of Cheraghi and Yousef (2019) also showed that academic self-efficacy negatively and significantly predicts academic procrastination51. In explaining this finding, self-efficacy beliefs determine the choice of activity, the amount of effort, and the duration of effort. A person with high self-efficacy engages in doing work instead of avoiding work as negligent behavior. He works on challenging activities and continues to work longer when dealing with problems. People with strong beliefs in their abilities show more effort and persistence in doing assignments than people who doubt their abilities. As a result, their performance in doing assignments is better. People who have been successful in previous or similar situations are more inclined to involve themselves in the new situation. Conversely, people who avoid facing challenging tasks and situations estimate their abilities to be less than what the situation requires to avoid facing the task as much as possible and commit to procrastination50. Self-efficacious students tend to confront obstacles and difficulties more than peers with low self-efficacy, particularly in academic settings. They persevere despite failures and employ efficient methods to tackle challenges.

Self-efficacy can also influence the formation of procrastination behaviors by mediating cultural or demographic factors. So, in societies where formal and informal education emphasizes effort from an early age, individuals tend to enhance their self-efficacy, subsequently leading to decreased procrastination. Additionally, certain demographic variables, such as age, may mediate the procrastination behaviors of individuals with high self-efficacy. For instance, older individuals, due to their responsibilities and obligations, often strive to perform their tasks more efficiently, leading to a decline in procrastination with age. Furthermore, when considering the role of gender, the differences in procrastination between males and females, as reported in some studies, can be explained by prior research. For example, it has been shown that students, regardless of gender, race, or learning style, engage in academic procrastination. The examination of the gender variable has yielded contradictory results. Some studies have reported no gender differences in procrastination between men and women. In contrast, others have found higher levels of procrastination in women, yet others have reported higher levels in men10,11,50.

The results of the present study showed a high level of difficulty in emotional regulation. This means that most of the studied students had problems regulating their emotions. In explaining this finding, people with difficulty in emotional regulation usually use a set of ineffective emotional strategies. These people are constantly caught up in judgment and prejudice concerning upcoming events. They are heavily involved in the anxiety-causing content of their thoughts, which prevents them from re-evaluating the situation from a positive or safe perspective. Therefore, these characteristics will cause people to be trapped in high levels of anxiety and worry51. Also, people prone to difficulty in emotional regulation due to emotional disorders experience a lot of negative emotions when faced with problems and turn to rumination, worry, and referential thinking to get rid of these unpleasant feelings. Also, these people experience more negative emotions and think more about negative thoughts52. People who have learned weak emotion regulation strategies may be more prone than others to use risky behaviors to relieve negative emotions53.

According to another part of the results of this study, there was a statistically significant direct correlation between the difficulty of emotional regulation and academic procrastination of students. This means students who had problems regulating their emotions had more academic procrastination. Also, the components of emotional regulation difficulty, including lack of emotional awareness, difficulty in performing purposeful behavior, limited access to emotional regulation strategies, difficulty in impulse control, non-acceptance of emotional responses, and lack of emotional clarity, were identified as positive and significant predictors of students’ academic procrastination. Based on the results of Ghasemi et al.‘s study (2020), there was a negative and significant relationship between emotional regulation and procrastination, so with the increase in emotional regulation, the amount of academic procrastination in students also decreased22. The findings of the study of Zarei and Khoshouei (2023) also showed a significant positive relationship between general academic procrastination and difficulty in emotional regulation among students23. In explaining this part of the findings, it can be said that procrastinating people are afraid of failure and suffer from low self-esteem and self-efficacy, are pessimistic about the future, and do not have hope; in fact, their minds are full of negative thoughts that prevent their productive activity and lead to procrastination. These thoughts are reactive, judgmental, and self-critical, which makes a person not motivated to do his homework, even though he knows that he must take steps to achieve his goals and success. On the other hand, procrastination is seen as a method for controlling negative emotions as it enables individuals to temporarily escape from such feelings and experience a more favorable state, which also confirms an inappropriate strategy (procrastination) to regulate emotions. Also, a person with a problem regulating emotions has difficulty accepting emotional responses, purposeful behavior, impulse control, emotional clarity, emotional awareness, and access to emotional regulation strategies. Therefore, it is possible to resort to negligent behaviors. In conclusion, the regulation of emotions through monitoring, evaluation, and correction can serve as a foundation for avoiding procrastination and its adverse emotional effects, such as depression22,23.

Conclusion

The moderate levels of variables of procrastination and academic self-efficacy and the high level of difficulty in emotional regulation among students in this study indicate that the studied students do not have a great desire to complete their personal and academic affairs. They delay their educational activities and assignments and do not control their emotions appropriately.

On the other hand, considering the predictive role of academic self-efficacy and the difficulty of emotional regulation concerning academic procrastination, planning effective interventions to enhance academic self-efficacy and emotion management, such as organizing workshops and training courses, is recommended. These interventions should aim to improve students’ attitudes towards their academic abilities for achieving academic success, and their ability to complete assignments and solve problems, as well as teach them how to control emotions and emotion-focused processing strategies.

Furthermore, based on the results of this study, it is recommended that educational decision-makers and policymakers take steps to increase students’ access to psychological professionals, update academic curricula to align with labor market demands, involve students in university decision-making and educational policymaking, facilitate part-time employment opportunities during their studies, and delegate specific university responsibilities to students.

In addition, the results of this study can provide an opportunity to use them for one of the goals of sustainable development: quality education. In this regard, considering the impact of the research variables on improving the quality of education in universities, it can be stated that education for sustainable development involves expanding and strengthening the capacities of individuals, groups, communities, organizations, and countries in such a way that their choices and judgments favor sustainable development principles. This requires that all universities, professors, and students be prepared to discuss the best and most direct ways to contribute to sustainable development. Moreover, taking into account one of the policies of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) and also the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), which is to support member states in developing educational systems to create quality and inclusive lifelong learning opportunities for all, the results of this study can contribute to enhancing the quality of university education by identifying the influential variables in improving students’ educational quality.

Finally, considering the significance of the issue, future studies are recommended to explore other contributing factors to academic procrastination behaviors and extend their scope to students in other medical fields, such as pharmacy and dentistry, to identify additional dimensions and develop more comprehensive solutions for mitigating such behaviors.

Limitations

One of the most important limitations of this study is its cross-sectional nature, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Therefore, it is advisable to utilize a blend of quantitative and qualitative methods or longitudinal strategies in future studies. It is also recommended that similar studies be conducted on other students studying in other fields of study in the field of medical sciences.

Another limitation of this study is the self-reporting of data by students, which may affect the accuracy of the study’s results. Since students’ psychological and emotional states can influence how they respond to questions, the researcher attempted to minimize this limitation by allowing sufficient time and asking students to be accurate and honest when completing the questionnaire. Additionally, other methodological and theoretical limitations of the current study include response bias, the sensitivity of the participants to the questions, and the sample being examined. In order to address these limitations, it is suggested that other researchers implement different scales of the variables in other populations. It is also recommended that readiness for responding to questionnaires of this nature be improved through training, repeated questionnaire administration, and the expansion of related research. Furthermore, the cultural differences, values, beliefs, attitudes, and perspectives of the students in this study compared to students from other universities may influence the generalizability of the results.

Acknowledgements

This study is approved by Jiroft University of Medical Sciences with ID of 837. The researchers would like to thank all the students who contributed to completing the questionnaires.

Author contributions

S.B. designed the study and prepared the initial draft. A.R.Y. and H.F.R. contributed to data collection and data analysis. J.B., S.B. and M.V. have supervised the whole study and finalized the article. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

All the data is presented as a part of tables or figures. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is approved by Jiroft University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee with the ID number of IR.JMU.REC.1402.002. All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Meanwhile, informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bastani, P., Nobakht, S., Yusefi, A. R., Manesh, M. R. & Sadeghi, A. Students’ health promoting behaviors: A case study at shiraz university of medical sciences. Shiraz E Med. J.19(5), e63695 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odacı, H., Kaya, F., Kınık, Ö. & Aydın, F. Assessing the satisfaction with school life among Turkish adolescents: Adapting the academic life satisfaction scale. Educ. Dev. Psychol.42(1), 1–11 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed, I., Bernhardt, G. V. & Shivappa, P. Prevalence of academic procrastination and its negative impact on students. Biomed. Biotechnol. Res. J. BBRJ7(3), 363–370 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goroshit, M. Academic procrastination and academic performance: An initial basis for intervention. J. Prev. Interv. Community46(2), 131–142 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian, L. & Fuqiang, Z. Academic stress, academic procrastination and academicperformance: A moderated dual-mediation model. J. Innov. Sustain. RISUS9(2), 38–46 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, K. R. & Seo, E. H. The relationship between procrastination and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Indiv. Differ.82, 26–33 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tavakoli, M. A. A study of the prevalence of academic procrasination among students and its relationship with demographic characteristics, prefrences of study time, and purpose of entering university. Q. Educ. Psychol.9(28), 99–121 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nasri, S., Shahrokhi, M. & Ebrahim Damavandi, M. The prediction of academic procrastination on perfectionism and test anxiety education and learning 1(11), 25–37 (2013).

- 9.Fatehi, Y., Abdkhodaee, M. S. & Porgholami, F. Relationship between procrastination with perfectionism and self-efficacy in public hospitals’ staff of Farashband City. Soc. Psychol. Res.2(6), 39–53 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tamadoni, M., Hatami, M. & Hashemi Razini, H. G. General self-efficacy, academic procrastination and students’ academic progress. Educ. Psychol. Q.6(17), 66–86 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheykhi, M., Fathabadi, J. & Heidari, M. The relations of anxiety, self-efficacy and perfectionism to dissertation procrastination. Evol. Psychol. Iran. Psychol.9(35), 283–295 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wigfield, A. & Eccles, J. S. Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol.25(1), 68–81 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steel, P. & König, C. J. Integrating theories of motivation. cad. Manag. Rev.31(4), 889–913 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strunk, K. K., Cho, Y., Steele, M. R. & Bridges, S. L. Development and validation of a 2 × 2 model of time-related academic behavior: Procrastination and timely engagement. Learn. Individ. Differences25, 35–44 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammadi Mj, Mohebi, S., Dehghani, F. & Ghasemzadeh, M. J. Correlation between academic self-efficacy and learning anxiety in medical students studying at Qom Branch of Islamic Azad University, 2017, (Iran). Qom Univ. Med. Sci. J.12(12), 89–98 (2019).

- 16.Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Adv. Behav. Res. Therapy1(4), 139–161 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asghari, F., Saadat, S., Atefi Karajvandani, S. & Janalizadeh Kokaneh, S. The relationship between academic self-efficacy and Psychological Well-Being, Family Cohesion, and Spiritual Health among students of Kharazmi University. Iran. J. Med. Educ.14(7), 581–593 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Przepiórka, A., Błachnio, A. & Siu, N. Y. F. The relationships between self-efficacy, self-control, chronotype, procrastination and sleep problems in young adults. Chronobiol. Int.36(8), 1025–1035 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ziegler, N. & Opdenakker, M-C. The development of academic procrastination in first-year secondary education students: The link with metacognitive self-regulation, self-efficacy, and effort regulation. Learn. Individ. Differ.64, 71–82 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ge, C., Li, C. & Li, S. Study on the relationship between the junior high school students’ self-efficacy and academic procrastination. J. Zhoukou Norm Univ.35, 146–152 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jamali, M., Noroozi, A. & Tahmasebi, R. Factors affecting academic self-efficacy and its Association with academic achievement among students of Bushehr University Medical Sciences 2012–13. Iran. J. Med. Educ.13(8), 629–641 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghasemi, H., Birami, M. & Vahedi, S. The role of emotion regulation difficulty components in predicting academic procrastination. New. Achiev. Humanit. Stud.3(27), 116–122 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zarei, L. & Khoshouei, M. S. The relationship between academic procrastination and metacognitive beliefs, emotion regulation and uncertainty tolerance in students. J. Res. Plan. High. Educ.22(2), 113–130 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehralian, G., Yusefi, A. R., Dastyar, N. & Bordbar, S. Communication competence, self-efficacy, and spiritual intelligence: Evidence from nurses. BMC Nurs.22(1), 99 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naragon-Gainey, K., McMahon, T. P. & Chacko, T. P. The structure of common emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic examination. Psychol. Bull.143(4), 384 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khakpoor, S., Bytamar, J. M. & Saed, O. Reductions in transdiagnostic factors as the potential mechanisms of change in treatment outcomes in the Unified Protocol: A randomized clinical trial. Res. Psychother. Psychopathol. Process. Outcome22(3) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Alaya, M. B., Ouali, U., Youssef, S. B., Aissa, A. & Nacef, F. Academic procrastination in university students: Associated factors and impact on academic performance. Eur. Psychiatry64(S1), S759–S760 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohammadi Bytamar, J., Saed, O. & Khakpoor, S. Emotion regulation difficulties and academic procrastination. Front. Psychol.11, 524588 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menbari, Z., karimi, Q. & yar ahmadi, Y. Developing a causal model of non-productive academic behaviors based on difficulty in regulating emotions and academic self-discipline in students with the mediating role of academic self-concept. Educ. Strategy Med. Sci.16(5), 498–510 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frumos, F. V. et al. The relationship between university students’ goal orientation and academic achievement. The mediating role of motivational components and the moderating role of achievement emotions. Front. Psychol.14, 1296346 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feraco, T., Resnati, D., Fregonese, D., Spoto, A. & Meneghetti, C. An integrated model of school students’ academic achievement and life satisfaction. Linking soft skills, extracurricular activities, self-regulated learning, motivation, and emotions. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ.38(1), 109–130 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valizadeh, Z., Ahadi, H., Heidari, M., Mazaheri, M. M. & Kajbaf, M. B. Prediction of College Students’ academic procrastination based on cognitive, emotional and motivational factors and gender. Knowl. Res. Appl. Psychol.15(3), 92–100 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gratz, K. L. & Roemer, L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess.26, 41–54 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yusefi, A. R., Lankarani, K. B., Bastani, P., Radinmanesh, M. & Kavosi, Z. Risk factors for gastric cancer: A systematic review. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP19(3), 591 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chehrzad, M. et al. Academic procrastination and related factors in students of Guilan University of Medical Sciences. J. Med. Educ. Dev.11(4), 352–362 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duru, E. & Balkis, M. The roles of academic procrastination tendency on the relationships among self doubt, self esteem and academic achievement. Egitim Ve Bilim39(173) (2014).

- 37.Lakshminarayan, N., Potdar, S. & Reddy, S. G. Relationship between procrastination and academic performance among a group of undergraduate dental students in India. J. Dent. Educ.77(4), 524–528 (2013). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mortazavi, F., Mortazavi, S. S. & Khosrorad, R. Psychometric properties of the procrastination assessment scale-student (PASS) in a student sample of sabzevar university of medical sciences. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J.17(9) (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Tamannaifar, M., Sedighi Arfaee, F. & Moghaddasin, Z. Explanation of the academic procrastination based on adaptive and maladaptive dimensions of perfectionism and locus of control. New. Educ. Approach.7(2), 141–168 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odaci, H., Kinik, Ö. & Kaya, F. Adaptation of the academic time management and procrastination scale. J. Hasan Ali Yücel Fac. Educ./Hasan Ali Yücel Egitim Fakültesi Dergisi HAYEF21(2), 120–126 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirzaei-Alavijeh, M., Hosseini, S. N., Motlagh, M. I. & Jalilian, F. Academic self-efficacy and its relationship with academic variables among Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences students: A cross sectional study. Pajouhan Sci. J.16(2), 28–34 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saadat, S., Asghari, F. & Jazayeri, R. The relationship between academic self-efficacy with perceived stress, coping strategies and perceived social support among students of University of Guilan. Iran. J. Med. Educ.15, 67–78 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazemi-Vardanjani, A., Heidari-Soureshjani, S. & Drees, F. Study of research self-efficacy components among postgraduate students in Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences. Res. Med. Educ.9(2), 65–57 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vahabi, B. et al. The status of academic self-efficacy in the students of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences and Islamic Azad University, Sanandaj Branch, 2015-16. Sci. J. Nurs. Midwifery Paramed. Fac.3(1), 43–52 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rahimi h. The study of relationship between thinking skills with academic self- efficacy in students at universities of Kashan and Medical sciences. Bimon. Educ. Strateg. Med. Sci.11(2), 91–96 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afra, A., Seneysel Bachari, S. & Rahimi, V. Investigation of the relationship between self-efficacy and academic enthusiasm among operating Room Technology Students. Bimon. Educ. Strateg. Med. Sci.17(2), 186–198 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Afra, A., Bachari, S., Ban, M., Darari, F. & Shahrokhi, S. Relationship between self-efficacy and academic motivation in the operating room students. Bimon. Educ. Strateg. Med. Sci.14(6), 405–412 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghasemi Gudarzi, M., Taghvaee Yazdi, M. & Heydari, S. H. Investigating and evaluating the state of academic self-efficacy with the desirability technique (a case study of Mazandaran University of Science and Technology). A new approach to children’s education 5(3), 34–44 (2023).

- 49.Sadoughi, M. The relationship between academic self-efficacy, academic resilience, academic adjustment, and academic performance among medical students. Educ. Strateg. Med. Sci.11(2), 7–14 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghadampour, E. et al. The Relationship Between Aacademic Motivation and Sself-Eefficacy with Aacademic Procrastination in the Students of Medical University of Jondishapour Ahvaz (2015).

- 51.Cheraghi, A. & Yousefi, F. The investigation of mediating role of academic motivation in the relationship between self-efficacy and academic procrastination. Knowl. Res. Appl. Psychol.20(2), 34–47 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kord, B. & Mohammadi, M. Predicting of Students’ anxiety on the basis of emotional regulation difficulties and negative automatic thoughts. Bimon. Educ. Strateg. Med. Sci.12(1), 130–134 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sabzevari, F., Ghasemi Ahmadabadi, L., Salehian Dehkordi, N., Barghamadi, F. S. & Abbasi, M. The role of difficulty in emotion regulation, self-differentiation, and coping styles in predicting referral thinking in adolescents with a history of drug use. Rooyesh e Ravanshenasi J. RRJ11(2), 229–242 (2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data is presented as a part of tables or figures. Additional data can be requested from the corresponding author.