Abstract

Background

Enabling community-led health initiatives will contribute to reducing the burdens on the healthcare system. Implementing such initiatives successfully in high and upper-middle income Asian countries is poorly understood and documented. We undertook a Rapid Review, systematically synthesising the evidence to develop implementation guidelines to address this gap.

Methods

Eligible studies focused on community movements or affiliated constructs in upper-middle and high-income Asian countries, conducted between 2014 and 2021. Studies were sought from either electronic databases – Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration, PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, SCOPUS, APA Psycinfo, Web of Science, Google Scholar – or recommendation from experts. Extraction was undertaken according to mid-level programme goals, termed Intermediate Results. These were conceptualized by a cross-disciplinary team and iteratively reworked as analysis progressed. Framework analysis was undertaken and structured according to the IRs. 28 studies (9 mixed methods, 9 quantitative, 7 qualitative and 3 case studies) were included and synthesised.

Results

The MovEMENTs checklist and related strategies were elicited through the review. The six Intermediate Results include to: (1) Move the community to be recruited and retained (2) Engage capacity and build capability; (3) Maintain emotional resonance; (4) Embed participatory approaches; (5) Nurture network building and partnerships; (6) Team up to improve commissioning and funding structures. Sixteen strategies and related implementation guidelines underpinning the Intermediate Results are extracted from the evidence-base of included studies.

Conclusion

The MovEMENTs for Health checklist is developed to serve as a guide for implementers and proposed to be adaptable to various contexts. The checklist should be tested, validated, and updated as a field tool.

Trial registration

PROSPERO ID: CRD42023471832.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-024-21046-y.

Keywords: Strategies for building community health movements, Population health, Framework analysis, Upper and higher-middle income Asian countries, Rapid review

Introduction

Singapore, a developed nation with a rapidly ageing population [1], saw its median age rise from 34 in 2020 to 41.8 in 2021 [2]. Alongside increased chronic diseases, this will likely escalate healthcare utilization [3]. Healthcare expenditure is projected to nearly triple from 21 billion SGD in 2018 to 59 billion SGD by 2030 [4].

To curb costs, empirical research suggest governments plan for autonomy-supporting policies, encouraging community actors to manage their own health [5, 6]. The “Healthier SG” policy exemplifies this by connecting communities to preventative care via goal setting with a dedicated General Practitioner (GP) [7]. Such policies would also benefit from communities initiating and leading their own prevention-driven health activities.

Therefore, seeking to drive forward collective action [8], the Ministry of Health’s Office for Healthcare Transformation (MOHT) set up the Movements for Health (M4H) programme [9]. In collaboration with commissioners, community coaching agencies and Community Movement Champions (CMCs) – which include social enterprises and health agencies – this programme aims to empower communities with the skills to foster behaviour change and achieve long-term impacts. The approach aims to initiate community-driven, sustainable health-focused programmes by implementing intentional commissioning structures that offer supportive and adaptable infrastructure.

Movement building builds upon community development traditions, such as Asset-based Community Development (ABCD) [10] by not only using local assets and social capital but also tapping into networks within the M4H programme. This strategy emphasizes sharing resources across CMCs, enhancing capability, and promoting collaboration beyond the neighbourhood level, aiming for nationwide change while preserving each initiative’s place-based focus and emphasis on participatory action.

Prior to developing our review protocol, we conducted scoping searches, which returned nil results for reviews on our specific topic and context. Even though reviews on community participation and empowerment approaches were identified, these were focused on health services development and largely based in non-Asian countries [11, 12]. Thus, the present review was judged necessary. It will be used to guide strategy design for engaging communities for M4H and similar socioeconomic and demographic Asian settings. This work was therefore undertaken in partnership with MOHT, with the goal of co-creating an evidence-based review for practical application.

The study team followed the Social and Behaviour Change (SBC) [13] tradition, taking a holistic, biopsychosocial view of health, and assuming that behaviour change, and social movements are connected and driven by empowerment. Although, established behaviour change theories do not address social movement building [14], Kok et al. (2016) has comprehensively catalogued theoretically aligned methods, or mechanisms of change, in relation to social movements for health [15]. Crucially, these authors emphasise the importance of involving multiple stakeholders, namely, community actors, implementors and volunteers, among others.

In line with this, following Satell’s appraisal of historical movements and network theory [16], the characteristics of a social movement are argued to essentially include: (i) small groups, (ii) loosely connected, and (iii) united by a common purpose. A framework analysis approach [17] was adopted for this review whereby consultation with technical experts and familiarization with the literature iteratively informed the conceptual framing and line of inquiry.

Consequently, the aim of the present rapid review is to catalogue the literature and assess the evidence-base for catalysing and sustaining social movement for health in high and upper-middle income Asian countries.

The review questions are as follows:

What types of programmatic initiatives are used to drive health movement building? These initiatives, termed Intermediate Results (IRs), will be derived from the literature, and agreed among the study team.

How can strategies and, specific related implementation guidelines that underpin the IRs be conceived and translated into a checklist?

The checklist will serve as an evidence-based field implementation guide for community-led programme development related to health movement building.

Methods

Using a theory-driven approach

Ultimately six IRs were identified (see sect. MovEMENTs Checklist). We applied the structure of the IRs to Framework Analysis [17] as developed for literature reviews, working in consultation with technical experts (co-authors) after familiarization with the literature. The IRs were therefore iteratively developed, evidence-informed and drove the conceptual framing and line-of-inquiry for the in-depth analysis of included literature.

The programmatic approach is informed by schools of thought that emphasise coalition building [18, 19], social planning [20, 21] and framing to shift perspectives, e.g., by assigning meaning to community events to gain buy-in [22]. Programme theory and ideation content will be refined and crystallised based on qualitative analysis, to be reported elsewhere. In the present study, we first seek to assess the evidence-base for catalysing and sustaining social movement for health in high and upper-middle income Asian countries.

Study design

A Rapid Review [23] using systematic methods was conducted. Though limited in scope, rapid reviews are considered part of the systematic review family, streamlining the process and offering evidence more efficiently than traditional reviews. This study adopted this method to quickly develop a checklist for M4H programme stakeholders, so that they can effectively plan timely evidence-based activities for urgent, high-priority implementation. We have applied Cochrane RR methods recommendations [24] and have documented these in Supplementary File 1,

The review protocol was assembled and agreed across the study team. Framework Analysis [17] was chosen because this method is considered ideal for literature synthesis containing complex content and needing to account for multiple methods.

Search strategy

Following senior librarian recommendations, we selected databases relevant to public health research, including Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration for healthcare interventions, Medline and Embase for biomedical and medical literature, CINAHL for nursing and allied health, SCOPUS for diverse scientific literature, APA PsycINFO for psychology, and Web of Science and Google Scholar for broad scholarly searches. Searches were conducted separately across these databases. Duplicates were removed using EndNote and checked manually.

The search and article selection were restricted to English language literature published between 2014 and 2021. Timeline restrictions were based on the rationale that in higher income settings community intervention approaches tend to be adaptive and fast changing [25].

The search string (see Table 1) was developed with a senior librarian and outputs reviewed by the study team. The strategy was to cast a broad net of search terms on programme evaluation and social movements for health but limited by specifying upper-middle and high-income Asian countries. This yielded a manageable context-relevant set of initial records for title screening and snowballing. Snowballing involved screening reference lists from included papers and literature suggested by local researchers and practitioners in community empowerment. This process followed the title, abstract, and full-text criteria in Sect. 2.4 to ensure a comprehensive search. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria can be found in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of search strings by type of databases

| Type of databases | Search term categories: terms were expanded and adapted to databases using MeSH / thesaurus terms where appropriate |

|---|---|

| Databases except Google Scholar | (Community movements) AND (health promotion) AND ((high or middle-income country) AND (Asian)) AND (programme development or evaluations) |

| Google Scholar | Community-led movements and program development for health promotion in high- or middle-income Asian countries |

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria by levels of screening

| Level | Inclusion Criteria |

| Title and abstract screening |

1. Mentioned community movements for health or affiliated constructs resulting in community-led initiatives, e.g., using participatory approaches or seeking to otherwise empower communities, in upper middle- and high-income contexts in Asian countries. 2. Evaluation, formative study or case study of above defined implementation. 3. Must be in the English language and published in 2014 to 2022. 4. Peer reviewed literature published in an academic journal. |

| Full-text screening |

1. Focuses on community movement building or affiliated constructs and contains identifiable domains of programmatic initiatives which drive Intermediate results (IRs). 2. Described and evaluated or appraised specific programme implementation strategies that underpin the IR domains. |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| At any level where it can be determined |

1. Community-based programme which did not meaningfully engage the community in programme delivery. 2. Focus on mass media (rather than community level) campaign. 3. Central Asian countries. 4. Recruited programme participants from clinical / health services contexts. |

*Intermediate Results (IRs) refer to interim actions that need to occur to spur the pathway to change and creation of health movements

Selection criteria

Main inclusion criteria involved retrieving peer reviewed qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods literature assessing programmes focused on community engagement and social movements for health, including evaluations, formative studies, or case studies related to these. Social movements were broadly defined as using community-based approaches and required community engagement in the conception and delivery of programmes, for example through participatory methods [26], distinguishing it from merely a community-based programme.

Our study focused on upper-middle and high-income Asian countries judged to have similar health priorities and community structures to prop up initiatives, such as M4H in the Singapore context. This meant the exclusion of Asian countries classified as lower or lower-middle-income by the World Bank [27]. Additionally, studies conducted in central Asia, e.g., Kazakhstan, were excluded due to their different cultural reference points.

There were no other restrictions imposed based on sample characteristics, such as age, or ethnicity, though studies did need to include participants and programmes that were recruited in the community, rather than via health services as patients. Consequently, studies such as clinical interventions were excluded. However, studies that recruited participants in the community but subsequently referred them to health services were retained. In addition, studies focusing on mass media campaigns, rather than neighbourhood community mobilisation, were excluded.

Quality appraisal of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies were conducted using Quality Appraisal across Study Methods (QASM) checklist [28] while case studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal of a Case Study (CAoCS) tool [29]. QASM and CAoCS were used to consider dimensions of reporting clarity, suitability of objectives to methods, validity of analytical methods, reliability of results and robustness of interpretations. Studies were scored as “strong”, “moderate” or “weak” according to specified criteria.

Screening procedure

Screening was undertaken at title, abstract and full-text level. At the title and abstract level, all the literature was independently appraised by three reviewers and 95% agreement was achieved by the last phase of screening. At full text, just under half of the articles were double screened by two independent reviewers, achieving 87% agreement. All disagreements and discrepancies were discussed and resolved with one team member acting as a moderator. Of the included studies at least 10% were quality appraised by two reviewers to ensure consistency.

Figure 1 reports the flow of inclusion following the PRISMA guidelines. After screening was completed n = 28 papers were included in the review.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Data storage and extraction

Searches were initially processed via Endnote and screened and extracted in Microsoft Excel. Evidence showing what was done to enhance the success of health programmes relating to movement building were extracted according to drafted IRs. IRs were refined iteratively to reflect included strategies and the guidelines underpinning them. Evidence could include either qualitative, quantitative, as well descriptive accounts of lessons learnt, or any combination of these. In addition, we also extracted: Programme identifiers; country and settings; health dimensions, defined as spanning biopsychosocial domains of functioning; study design and methods. All data were double extracted to ensure reliability.

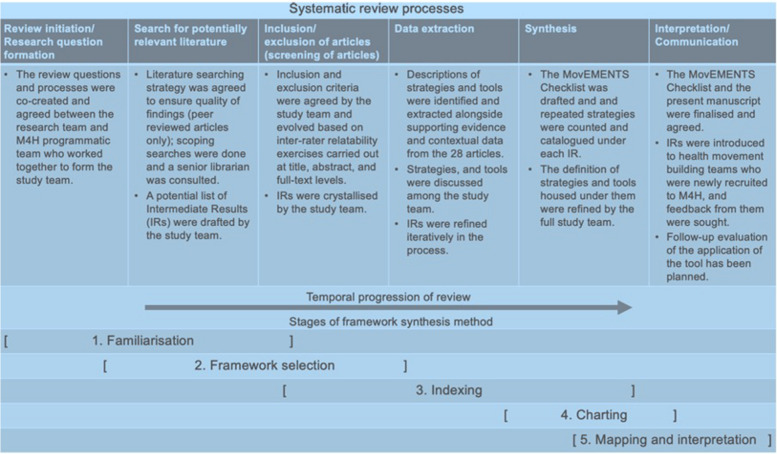

Data analysis, synthesis and reporting

Framework analysis was used to conceptualise this study, see Fig. 2, which shows the steps undertaken to produce the checklist. Thus, the IRs were conceived to frame extractions and agreed in consultation with technical experts and after familiarization with the literature. The framework selection was therefore an iterative process. Once the IRs were agreed, an extraction matrix was created in Excel and the literature indexed according to each IR. Charting was done by building up lists of extracted strategies and guidelines from indexed portions of the literature and matching them to the IRs. Synthesis was done by cataloguing the extent to which these repeated across the 28 included studies and appraising supporting evidence.

Fig. 2.

Framework synthesis, adapted from Brunton et al., 2020 [17]

At the mapping and interpretation stage, extractions were decided, and a final list compiled into the Health MovEMENTs checklist.

Results

Descriptive findings

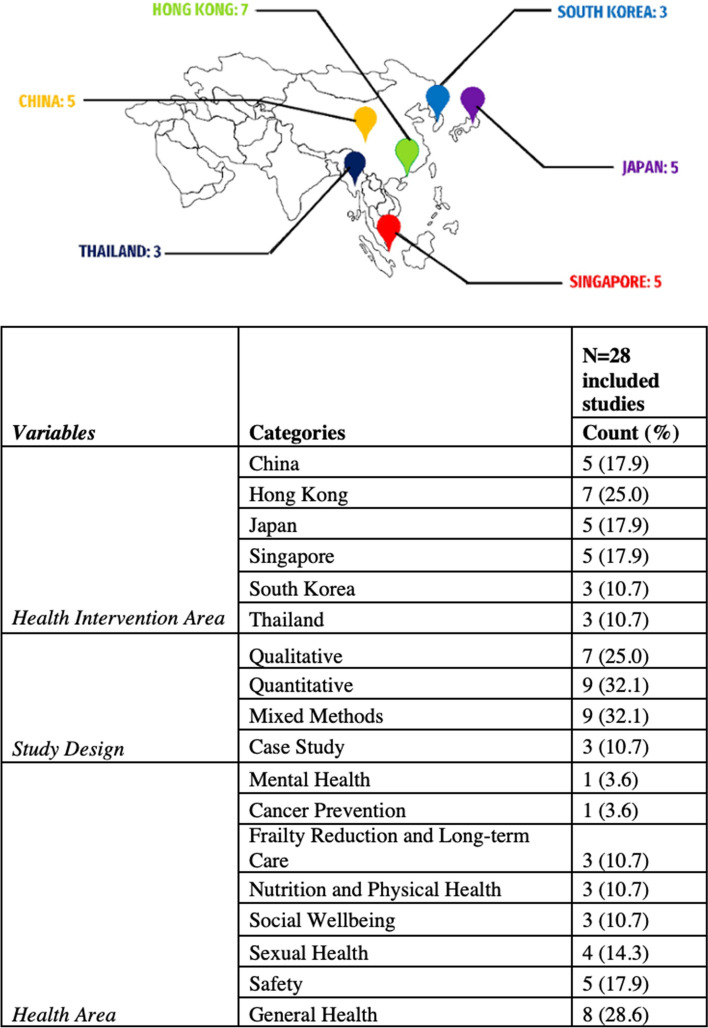

Electronic literature searches were conducted between 28 November 2021 and 27 January 2022. Recommendations from experts was sought to supplement our pool of included studies between 1 August 2022 to 22 August 2022. A total of 405 studies was identified, including literature recommended from Singapore-based experts. 371 studies were retained after duplicates were removed. Thereafter, we conducted title and abstract screening, and 63 articles remained. Finally, after a full-text screening was performed, we found that 28 articles [30–58] met our inclusion criteria. Figure 3 provides a summary of descriptives for the 28 included articles.

Fig. 3.

Distribution of included studies by study design, country of origin, and health intervention area

Eight of the articles were published between 2020 and 2021, while the rest (n = 20) were published between 2014 and 2019. Among the included papers, 25% were qualitative studies, 32% were quantitative studies, 32% were mixed methods, and 11% were case studies from six higher and upper-middle income countries, with most studies from Hong Kong (n = 7). It was found that 25% of the studies scored “strong” on the QASM and CAoCS quality review. The remainder of the studies scored “moderate”. There were no studies rated “weak”. 23 articles were based on adult or older populations; three articles involved youths; one was on children; and another pertained to a cross-section of the general population.

Studies differed in health areas of focus, with the majority focusing on general health, encompassing bio-functional, mental, and social facets of health (n = 8). In addition, five studies focused on safety, four on mental and social well-being, four on sexual health, three on nutrition and physical health, three on frailty, and one on cancer prevention.

MovEMENTs checklist

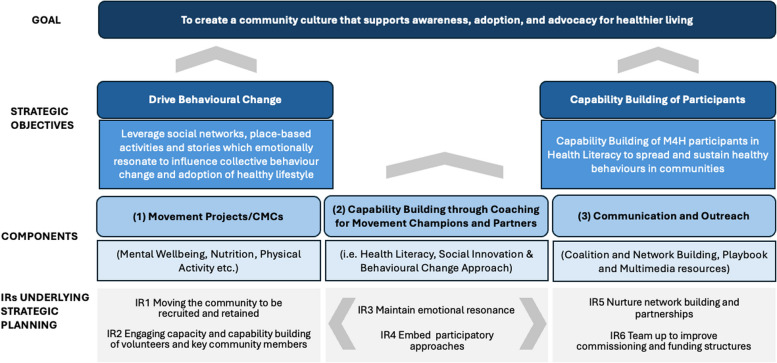

Identified IRs summarised the main trends in the data, these include: consistent community engagement and outreach, often tied to a holistic BioPsychoSocial programmatic focus; building of the programme’s volume of non-professional facilitators whilst training them; using emotionally meaningful messaging and connection to place; embedding participatory approaches; leveraging networks and partnerships, especially at the agency level; and helping to facilitate sustainable funding and commissioning.

These identified trends have been synthesised into the MovEMENTs Checklist, consisting of six IRs, namely: (1) Move the community to be recruited and retained; (2) Engage capacity and build capability; (3) Maintain emotional resonance; (4) Embed participatory approaches; (5) Nurture network building and partnerships; (6) Team up to improve commissioning and funding structures.

IRs have also been grouped by target audience, such as community members for IR1 and IR2 versus agency and commissioning stakeholder for IR5 and IR6, whilst IR3 and IR4 are infused at both levels. Figure 4 illustrates this categorisation of IRs.

Fig. 4.

Grouping of IRs according to target audience

The MovEMENTs Checklist is structured by the six IRs, where related strategies and number of records relating to these were extracted accordingly. Strategies are numbered and italicised for convenience and discussed in turn with illustrations of identified guidelines that allow these to be implemented (see Table 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8). A consolidated checklist for use in practice can be found in Supplementary file 2.

Table 3.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR1, Move the community to be recruited and retained

| IR #1: Move the community to be recruited and retained ➩ Focus is on programme participants |

|---|

| 1.1 Strategy 1: Build on strong rapport and community ties to generate demand |

| 1.1.1 Promotional, community-embedded activities such as mobile counters and door-to-door visits, using the opportunity to become well-acquainted with residents, particularly hard to reach groups [30–32]. |

| 1.1.2 Lay health promoters to share life experiences with residents, building bonds during onboarding phase [31, 32]. |

| 1.1.3 Having programme managers who are well-liked and trusted to advocate for the programme. This can improve participation rates and promote group cohesion [33]. |

| 1.1.4 Onboarding using guided discussion on views on shared problems and build on these discussions to create a sense of unity and shared responsibility [34]. |

| 1.1.5 Creating opportunities for peer recruitment [32], and peer support, e.g., inviting people to join breakout activities together [35]. |

| 1.2 Strategy 2: Raise awareness of health gains to encourage programme adoption |

| 1.2.1 Holding in-person events and/or digital activities to teach the public about health gains offered by the programme [36]. |

| 1.2.2 Building health literacy will motivate community actors to grow programme participation and keep new recruits engaged [37]. |

| 1.3 Strategy 3: Ensure accessibility and visibility of community activities |

| 1.3.1 Hold programme in a favourable location in the community, e.g., close by, in a known location, which is attractive to the participant [32], while provisioning for access of attendees with disabilities [38]. |

| 1.3.2 Ensure suitable programme timing by providing a few timing options, e.g., for children’s programmes avoiding timings when children tend to watch cartoons [39]; or for adult programmes weekdays or timings when they must go to work or look after children [40, 41]. |

| 1.3.3 Plan to recruit volunteers to organize playgroup session for participants’ children allowing their parents to attend the programme [40]. |

| 1.4 Strategy 4: Encourage committing to activities and continued uptake of learned behaviours |

| 1.4.1 Incorporate simple acts of appreciation to attendees, this includes actively ushering participants on arrival, thanking them for coming, and providing personal reminders to return each week [33]. |

| 1.4.2 Consider adopting a low participation fee, e.g., 100 yen/1 USD/2 SGD per visit [38]. This makes the programme still accessible, but also places a value on attendance, especially if the event is pre-paid. |

| 1.4.3 Using digital auto-reminders to prompt undertaking of self-directed activities, e.g., a Move-It icon on desktop computer screen to prompt participation and interrupt prolonged sitting activities [35]. |

| 1.4.4 Maintain regular contact to provide constant reminders of events and support to programme participants, encouraging them to continue with intervention [33]. |

| 1.4.5 Ensuring basic needs are met in the most deprived populations to enable commitment and continuation of engagement [42]; indeed, incentives and monetary support may be required to adjust for this type of scenario. |

Table 4.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR2, Engage capacity and build capability

| IR #2: Engage capacity and build capability ➩ Focus is on volunteerism and community advocates |

|---|

| 2.1 Strategy 5: Activate volunteer engagement and advocacy |

| 2.1.1 Engage volunteers to become advocates through passing on of knowledge and skills [30–35, 40, 41, 43–49] of standardised programme activities and content. |

| 2.1.2 Identify laypeople, e.g., peer educators or implementation coleaders who programme participants can relate to and learn best from. This will often include those with similar socioeconomic backgrounds and cultural values [32, 43, 45]. Pools of recruits will often need to be refreshed as cohorts move on [43]. |

| 2.1.3 Engagement strategies that allow bonding among laypeople will predispose them to work better together and become willing to take on advocacy roles for civic action [47]. This was demonstrated so far especially in older adults, for these advocates engagement in civic action in turn improves quality of life [50]. |

| 2.1.4 Learning about health gains can also spark participants to take initiative to implement and organize future activities [37]. |

| 2.1.5 Seek out trusted experts on health and related fields as well as people willing to share first-hand experiences of illness and health promotion [30, 39, 51] can be used to attract other volunteers and advocates. |

| 2.1.6 Consider specific subpopulations who be committed to serve as volunteers [52, 53], e.g., some studies suggest that retired teachers, and other professional retired people [52] and seniors [44] make good volunteers as they have more spare time, less financial stress, and may have stronger neighbourhood ties than young people. |

| 2.2 Strategy 6: Train recruited volunteers and advocates to engage peers and pass on knowledge |

| 2.2.1 Planning for training trainers events and improving knowledge and skills through a measurable pre-, post- testing and longitudinal testing [30, 31, 34, 40, 41]. |

| 2.2.2 Select volunteers that live in the neighbourhood and have the ability to build strong rapport with the residents where programmes are being run [31, 32, 35, 40, 41, 43, 45, 47]. |

| 2.2.3 Work with training partner organizations who are familiar with the neighbourhood and who can use this to improve training approaches and, in turn, learning outcomes [33]. |

| 2.2.4 Make use of experts in the field of interest to the programme to mentor the project team designing the training materials and implementation strategy [42]. |

| 2.3 Strategy 7: Use multiple and diverse ways to engage participants in learning |

| 2.3.1 Provision of formal, culturally appropriate, training materials, i.e., take away training kits, notes, guidelines, and checklists [30, 31, 39, 40], e.g., including culturally relevant images in training material, reviewing training material for linguistic appropriateness, [40] and using common words and giving examples of slang words [39]. |

| 2.3.2 Use engaging training methods, e.g., experiential learning or field trips; “learning by doing” practical workshops; anticipation of challenging scenarios and brainstorming solutions; and interactive teaching strategies such as games, simulations, role play and debriefing sessions to actively involve trainees [30, 31, 34, 39–41]. |

| 2.3.3 Plan for resources that can be adapted to suit individual needs, e.g., for younger or older age, experienced and less experienced, or those recovering from illness or injury [35]. |

Table 5.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR3, Maintain emotional resonance

| IR #3: Maintain emotional resonance ➩ Focus crosscuts all actors |

|---|

| 3.1 Strategy 8: Focus project content meaningfully |

| 3.1.1 Create ground-up, community-led programmes made by the community for the community [30–57]. e.g. place-based activities, which are led by familiar, community-embedded volunteers. |

| 3.1.2 Agree a shared vision to bring people together and garner buy-in from all involved parties [33]. |

| 3.1.3 Conduct research on how to better design programme content, outreach [30, 38, 39, 41, 42, 54] such that these can inform designing and promoting the programme. |

| 3.2 Strategy 9: Plan community-embedded longstanding promotion |

| 3.2.1 Use interpersonal channels, e.g., enlist high-profile figures [33] known in the community such as public figures and opinion leaders, or trusted grass-roots leaders to help promote initiatives. |

| 3.2.2. Also, plan for embedded promotional activities that enhance programme visibility [31, 35]. |

| 3.2.3 Create online presence imbued with content that represents the community and programme values, e.g., Instagram account, website etc. [35, 43]. |

| 3.2.4 Implement over an extended period (suggested more than 3 years) [46] to increase trust and acceptance of messaging through consistent-ongoing visibility. |

Table 6.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR4, Embed participatory approaches

| IR #4: Embed participatory approaches ➩ Focus crosscuts all actors |

|---|

| 4.1 Strategy 10: Co-create programmes with community actors and other stakeholders |

| 4.1.1. Participatory methods will cut across involving programme participants and community-embedded leadership, government, and commissioning agents as well as university collaborators [53]. Where needed coaching on participatory approaches – at all levels – should therefore be planned for. |

| 4.1.2 Programme participants especially should be empowered through group discussions to contribute their expertise to create activities that respond to their specific needs, assets, and preferred services [31, 35, 51, 55]. |

| 4.1.3 In addition, consider using creative, community-embedded method(s) and activity(ies) that allow all involved actors to better understand the community spaces and target population, e.g., through Photovoice, or community dialogues or “go-along” interviews [36, 37, 39, 42, 53–55]. |

| 4.2 Strategy 11: Create safe environments to enable open sharing |

| 4.2.1 Plan to conduct group discussions allowing attendees to build some rapport beforehand [47, 55] and keeping the groups small to allow for more comfortable sharing [54]. Seek to build consensus [34] but be explicit about being opening to change and refinement of suggested ideas and planning [43]. |

| 4.2.2 Emphasize “ground rules” including listening, not interrupting and the importance of respecting and being non-judgmental of other's shared life experiences and ideas [32]. |

| 4.2.3 Enable all members to have equal opportunity to participate [34] and encourage those not actively participating [55]. Identifying positive influencers can also aid in motivating quieter participants to speak up [47]. |

| 4.3 Strategy 12: Use monitoring data to inform working together on areas for redress |

| 4.3.1 Plan to generate data needed to monitor implementation and evaluate progress [45, 51]. Findings should be shared and used them to inform action plans to course correct implementation and policy reformulation as needed, using established feedback loops, as suggested below. |

Table 7.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR5, Nurture network building and partnerships

| IR #5: Nurture network buildingand partnerships ➩ Focus is on agencies partnering with each other and/or government |

|---|

| 5.1 Strategy 13: Agencies take action to work together |

| 5.1.1 Seek to build trust among collaborating agencies by sharing information, knowledge, and good intention [51], setting aside institutional rivalry [30] and agreeing common goals for collective action [56]. |

| 5.1.2 Provide a platform for community partners to discuss and reach a consensus on shared goals [53, 55]. Such platforms can also be used to build strategy, agree priorities and to connect community level initiatives across agencies and align what is happening on the ground to government policy planning [45]. |

| 5.2 Strategy 14: Establish networks linking community members to care |

| 5.2.1 Using case detection tools and peer recruiters’, community organizations work with health service providers to assess needs and connect programme participants to care and services [32, 43, 47, 48], thus reducing barriers to care delivery. Services that community members may be connected to include for example social services, mental health counselling or HIV services which may be stigmatised or difficult to access otherwise. |

Table 8.

Strategies and related guidelines for IR6, Team up to improve commissioning and funding structures

| IR #6: Team up to improve commissioning and funding structures ➩ Focus is on commissioners and/or lead government agencies and funders |

|---|

| 6.1 Strategy 15: Commissioners invite and enable collaboration between health agencies, researchers and the community |

| 6.1.1 Commissioners appoint implementing agencies and researchers that are well versed with community needs and enable them to work together to lead the design implementation and evaluation of programmes [48, 56]. Commissioner will act as a connector bringing these actors together through formal and informal collaborative events [36]. |

| 6.1.2 Commissioners plan to actively familiarise themselves and collaborating agencies with participatory approaches, by extension they will also demonstrate that they value the community through listening to residents' feedback and suggestion [47] and not treating treat them as subjects of a programme or means to programme success [56]. |

| 6.2 Strategy 16: Facilitate collaborations by addressing adequacy of resources |

| 6.2.1 Commissioners should plan to provide start-up seed funding, especially for stable manpower and reducing turnover, e.g., plan for compensation for volunteers who do not receive salary, so they are recognised for their time and efforts [52]. High staff turnover has been shown to result in difficulty solidifying working relationships across sectors [56]. |

| 6.2.2 Seed funding should also ensure enough start-up funds are made available to equip new initiatives, run activities, and create promotional materials. [31, 43, 57], learning from the reviewing of funded start-ups financial accounting. |

| 6.2.3 Seed funding can be complemented by co-funding from the community agencies to trial and establish a self-sustaining operational model [45]. |

IR1. Move the community to be recruited and retained

One strategy for recruiting participants in community-led initiatives was to (1.1) build on strong rapport and community ties to generate demand (n = 6). This involves using tactics like community-embedded promotional activities such as mobile counters and door-to-door visits, especially to engage hard-to-reach populations [30–32]. Lay health promoters can also share personal experiences to build bonds [31, 32], involve trusted program managers [33], use guided discussions to help reach consensus and unity within the group [34], as well as employ peer-recruitment and support groups [32, 35].

For example, in a Hong Kong intervention [30], active door-to-door networking and mobile counters fostered relationships and collective responsibility, resulting in the recruitment of 1000 participants. Similarly, in China, trusted peers recruited gay men for HIV self-testing in pubs, leading to 90.4% of those testing positive being linked to care [32].

Another strategy is to (1.2) raise awareness of health gains to encourage programme adoption (n = 2). In China, an inovation contest on sexual health spurred engagement, both digitally and in-person [36], which also further encouraged participation in other related events. In Japan, residents involved in a frailty programme evaluation became motivated to expand the programme for their community, leading to an 80% participation rate in health check-ups [37]. Additionally, the mortality rate for non-attendants was higher than attendants of the programme (log– rank test, p = 0.02).

Demand generation also require that programmes (1.3) ensure accessibility and visibility of community activities (n = 5). This includes choosing favourable locations known to the community [32] and considering access for those with disabilities [38]. Relatedly, a Japanese programme targeting high-risk seniors achieved nearly double the participation compared to conventional nationwide programmes by ensuring venue accessibility [38]. Also, accounting for flexible timings can boost outreach, as shown in three studies which identified childcare as a barrier to attendance [39–41]. In a Hong Kong program, organising play sessions for participants’ children was suggested to improve attendance [40].

Likewise, to (1.4) encourage committing to activities and continued uptake of learned behaviours (n = 5), strategies include showing appreciation to attendees [33], setting low sign-up fees [38], and using digital or personal reminders [33, 35]. However, when working with marginalized groups, ensuring basic needs are met is crucial before fostering commitment [42].

IR2. Engaging capacity and building capability

Engaging capacity involves recruiting enough skilled community actors and enhancing their capability to sustain program implementation. Firstly, (2.1) activating volunteer engagement and advocacy (n = 19), which is a cornerstone of movement building, underpinned by passing on knowledge and skills of standardized programme activities [30–35, 40, 41, 43–49]. Identifying relatable laypeople, like peer educators, is essential, as is matching socioeconomic backgrounds and cultural values where possible [32, 43, 45].

For example, a Hong Kong programme trained students as mental health leaders, fostering a conducive environment for mental wellness [43]. Although continued success depends on nurturing students as co-leaders, and refreshing these pools of recruits as cohorts move on [43].

Bonding exercises for laypeople in leadership roles enhance advocacy and collaboration, as shown in a study on senior civic engagement [47]. These exercises centred on autobiographical sharing, with the intervention group displaying a 92% higher level of civic engagement in comparison to the control (95% CI 1.41–2.78) [47]. In turn, improving their quality of life [50].

High engagement in understanding health gains also builds capacity. In Japan, volunteers who collected programme evaluation data became motivated to organize future activities, achieving high response rates on their monitoring system (range 91.1–98.8% completion) [37]. Additionally, engaging trusted health experts and individuals sharing personal experiences can attract volunteers and advocates [30, 39, 51]. Retired professionals and seniors often serve as effective volunteers due to more spare time and strong community ties [52, 53].

For capability building, (2.2) training recruited volunteers and advocates to engage peers and pass on knowledge (n = 11) was key. This involves planning “train the trainer” events and assessing knowledge through pre-post or longitudinal testing [30, 31, 34, 40, 41]. Locally-based trainers or community-based partners with strong community rapport are recommended [31, 32, 35, 40, 41, 43, 45, 47], alongside mentorship from field experts [42].

Successful training requires (2.3) using multiple and diverse tools to engage participants in learning (n = 8), such as formal, culturally appropriate training materials [30, 31, 39, 40]. For example, a Hong Kong breast cancer prevention training employed structured materials and interactive strategies which was rated highly effective by attendees [40]. Engaging methods like experiential learning, simulations, “learning by doing” practical workshops, role play, and debriefing sessions are recommended [30, 31, 34, 39–41]. Training materials should be adaptable to different ages and experience levels to ensure consistency and efficiency [35].

IR3. Maintain emotional resonance

A common feature in all reviewed studies [30–57] to create community-led programmes tailored by and for the community was to (3.1) focus project content meaningfully (n = 28), e.g. tugging at people’s emotional connection to characters, messaging and place used to convey the programme’s vision. Equally important, though less discussed, is the need for a shared vision [33]. A Singapore evaluation suggested that such a vision should align the needs of community actors, agencies, and commissioners. Aw et al. (2019) argue that this approach fosters a participant-centred mindset, countering Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and “working-in-silo” setups and encouraging resource sharing.

Research, often conducted with university-based researchers, is used to develop program content and outreach strategies, embedding participatory elements [30, 38, 39, 41, 42, 54]. These findings embedded with participatory elements are then used to (3.2) plan community-embedded longstanding promotion (n = 5) or campaigns.

Using interpersonal channels [33], high visibility community-embedded, consistently branded materials [31, 35], and online campaigns [35, 43] enhances programme trust and resonance. For instance, a Chinese program used visible campaigning tactics, such as displaying promotional videos in canteens and issuing daily computer reminders. Qualitative feedback revealed that such strategies captured the full attention of employees, resulting in the participation of those who had not initially registered for the programme [35].

Furthermore, to bolster the impact of programme messages, activities should be implemented over extended periods (at least three years). For example, the mixed success of safety campaigns in Korea indicated that time is needed for message acceptance, behaviour change, and improved safety outcomes [46].

IR4. Embed participatory approaches

Participatory approaches are essential to MovEMENT creation, ensuring collaborative programme identity and emotional resonance. These approaches aim to (4.1) co-create programmes with community actors and other stakeholders (n = 10), involving programme participants, community-embedded leadership, government, commissioning agencies and university collaborators [53]. Coaching on these approaches is recommended at all level. Participatory engagement involves empowering programme participants through group discussions to contribute expertise for activities that meet their specific needs [31, 35, 51, 55].

Creative community-embedded methods like Photovoice, community dialogues or “go-along” interviews help all involved actors understand community spaces and target populations [36, 37, 39, 42, 53–55]. Several Singapore studies using Photovoice, go-along interviews, and community focus groups demonstrated how interacting with community spaces shapes participants’ ideas and contributions [42, 54].

To enhance participatory approaches, programmatic teams should (4.2) create a safe environment to enable open sharing (n = 4). Small groups and pre-meeting rapport building are recommended [47, 55]. Meetings should aim for consensus [34], whilst remaining open to idea refinement [43], and establishing ground rules like listening and mutual respect [32]. Facilitators should ensure equal participation [34] and encourage those not actively participating [55]. Positive influencers can help motivate participation for quieter individuals [47].

Programmes should also (4.3) use monitoring data to inform working together on areas for redress (n = 3). In a Korea case study, sharing injury data helped shape community safety interventions [51]. In Thailand, anthropometric indictors were routinely collected to monitor child malnutrition, where villagers “at-risk” were flagged, involved in health dialogues which informed action plans and government support requests [45].

IR5. Nurture network building and partnerships

This IR emphasizes networking building and collaborative partnerships across implementing agencies. It begins with (5.1) Agencies taking action to work together (n = 4). Studies highlight the importance of building trust among collaborating agencies by sharing knowledge, setting aside institutional rivalries [30], and agreeing on common goals [56]. One way to practically connect partners is through a shared platform to build strategy, agree priorities, align initiatives with government policy, and connect community-level programmes [45]. For instance, the “Healthy Akame!” program in Japan formed a Community Advisory Board (CAB) with community organizations, city officials, and university researchers to translate residents’ inputs into health priorities [53].

Health movements can also be used to (5.2) establish networks linking community members to care (n = 4). This involves using case detection tools and peer recruiters from community organizations, who work with health service providers to connect participants with stigmatised services like mental health counselling, social services, and HIV support [32, 43, 47, 48]. This approach is supported by a suicide prevention program in Hong Kong, where trained community volunteers identified signs of distress and referred individuals to care, resulting in a significant decrease in suicides post-test [48].

IR6. Team up to improve commissioning and funding structures

To ignite MovEMENTs, commissioners should focus on cross-sectoral team building, emphasizing (6.1) inviting, and enabling collaboration between health agencies, researchers, and the community (n = 3). This involves appointing implementing agencies and researchers familiar with community needs to collaboratively design, implement, and evaluate programmes [48, 56], and connecting them through formal and informal collaborative events [36].

Exemplified by Heo et al. (2018), reducing health inequity in a deprived South Korean neighbourhood required a committed leader to foster collaboration among agencies [56]. Therefore, commissioners, above all other actors in the implementation ecosystem, need to plan to actively use participatory approaches, valuing community input [47], and avoiding treating residents merely as programme subjects [56].

Commissioners are also responsible for the (6.2) facilitation of collaborations by addressing adequacy of resources (n = 6). These consist of planning to provide start-up seed funding for stable manpower and volunteer compensation [52], as high staff turnover hinders cross-sector relationships [56]. Seed funding should also support new initiatives, running of activities, and promotional materials [31, 43, 57].

For sustainability, seed funding should be complemented by other sources, like community fundraising. For instance, in Thailand, government seed funding for a child malnutrition initiative was complemented by community-raised funds, creating a self-financing model that significantly reduced malnutrition [45].

Discussion

The MovEMENTs checklist was created out of collaborative efforts as an instrument to help guide field implementation and evaluation. As argued by Tricco et al. (2015) [58] partnerships between researchers and policy makers facilitate the conduct of useful, applied reviews. For the findings to be used they also need to be valued and accessible. These criteria drove the present study’s conception.

Movement building uniquely positions itself within the field of community development [10] through its emphasis on network building and resource sharing among partners in the programme. This allows for health movements to grow across neighbourhoods whilst remaining self-sustaining due to its participatory nature and anchoring to people and place. Furthermore, deliberate seed funding provides support for emotionally resonant bottom-up initiatives, while purposefully targeting population health concerns.

Thus, this review has allowed conceptual mapping of the different elements that catalyse movement building. A visual illustration of Movements for Health (M4H) Model, showing the underpinnings of the elements identified as IRs is summarised in Fig. 5. Moving the community is initially focused on garnering committed community participation to activities creating Movement Projects / CMCs.

Fig. 5.

Movements for Health (M4H) model

Driven by the IRs, CMCs will grow from capability building through coaching for movement champions and partners. Success will also hinge on communication and outreach at the agency and broader macro levels. Eventually, sustainable movement building will necessitate a shift away from direct commissioning, towards the establishment of robust networks and partnerships, creating community embedded systems for capability building and to drive behaviour change.

Practically, it is important to note that this MovEMENT building tool is intended as a checklist, not an audit tool. Using many elements can indicate momentum for movement building, but using fewer elements does not necessarily mean a programme is not building a movement. The checklist includes an open-ended component (see Supplementary file 2) where additional guidelines for strategy implementation can be added if they are not already listed. By using and applying the tool, it can be expanded to enable more programmes to qualify as movements, both by fostering innovation and adhering to the guidelines suggested in this review.

In terms of policy, we acknowledge the somewhat paradoxical notion of commissioning bottom-up initiatives. However, we believe that through appropriate use of the MoveMENT checklist and resonance with the health movement building ethos, this seeding mechanism can help shift cultural landscapes.

Strengths and weaknesses

The strength of the review lies in its specificity and relevancy. In accordance with rapid review methodology, our search strategy was tailored to context, ensuring rigor while facilitating a focused analysis of the recent literature. Existing systematic reviews centring on empowering communities identified very few or no studies from Asia [59, 60]. Yet our focused approach identified 28 studies relevant to Asian countries of interest. This is despite having sacrificed some sensitivity from limiting our searching by context early on, as well as having the stringent inclusion criteria requiring community-led or somehow co-created programme content. Our search strategy was no doubt well enhanced by snowballing and seeking recommendations from Asia-based experts in our field.

However, some depth may still be missing in our analyses. For example, given our final yield of included studies we were unable to synthesise to the level of life course stages. Additionally, to streamline the rapid review process, we chose to exclude grey literature and non-English sources. We are cognizant of the potential loss of some non-peer reviewed reports. However, we argue that health movement building is a novel concept, and future research can build upon this rapid review through expansion of our search strategy and inclusion criteria.

We recognize that the MovEMENT Checklist is a complex implementation tool, requiring stakeholder buy-in and understanding of the IRs and related strategies. To ensure its practicality, the study team maintained open feedback loops with CMCs, community coaching agencies, and commissioners throughout the review process. At the community level, some CMCs have employed reminder systems and rapport building to boost engagement (IR1), while others have developed volunteer networks and training to enhance health literacy (IR2). At the agency level, this involves workshops for networking and to align goals (IR5) and adjusting funding structures to better suit the evolving nature of movement building (IR6). Cross-cutting these levels are the use of Facebook groups to share meaningful digital content connects people and places (IR3), and in-person community dialogues encourage participants to lead discussions and co-create their own health activities (IR4).

Conclusion

Overall, research relating to strategies for community health movement building at the neighbourhood level in higher-income Asian settings is lacking. We chose to focus on these, learning from the specific with the aim of informing the more general. Accordingly, a comprehensive health MovEMENT building checklist has been proposed. Nevertheless, the proof of its validity will be in its application. We anticipate that with the evolution and expansion of the checklist, will allow for more programmes to become self-sustaining and reflective of needs on the ground. Testing of the checklist in Singapore will be documented in future M4H studies, while its application and transferability to other setting can also be explored.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The study team is grateful to all extended Movements for Health (M4H) implementers who took the time to review our checklist. We would also like to extent our thanks to Ms Toh Kim Kee, Senior Librarian. Ms Toh provided guidance and helped to refine the search strategy.

Author's contributions

ZJH conceived the study and designed the research framework and review questions. ZJH, WXZ, and AYC developed the protocol and search strategy, including establishing inclusion/exclusion criteria. WXZ and FCJH conducted the systematic literature search, screened articles and extracted data according to the protocol, with ZJH and AYC acting as mediators. WXZ and FCJH conducted the analysis, with inputs from the study team. FCJH and WXZ drafted the manuscript, with inputs from AYC, and revised by ZJH. All authors reviewed and reached a consensus on the MovEMENT categories and classification of related strategies and guidelines, and in addition commented and agreed on the content of the final manuscript prior to submission.

Funding

This work was supported by the MOH Office for Healthcare Transformation (MOHT), Singapore, in collaboration with the National University of Singapore Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health (NUS, SSHSPH), Singapore, on Grant Ref: Monitoring, Evaluation, Research and Learning for Movements for Health (M4H) Programme.

Data availability

The study is reported in accordance with Cochrane rapid review methods recommendations (Supplementary File 1). The screened dataset constitutes the intellectual property of the study team and is not publicly available. It can be shared upon reasonable request to the review team.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study does not involve human subjects and therefore ethical review and consent to participate was not required.

Consent for publication

This was not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Felicia Jia Hui Chan, Alyssa Yenyi Chan, Wen Xi Zhuang and Zoe Jane-Lara Hildon contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Rogerson A, Stacey S. Successful ageing in Singapore. Geriatrics. 2018;3(4):15. 10.3390/geriatrics3040081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Singapore, Population Trends. 2021. 2021. https://www.singstat.gov.sg/-/media/files/publications/population/population2021.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 3.Bloomfield J. Singapore’s ageing population and nursing: Looking to the future. Singapore Institute of Management. 2019. https://www.sim.edu.sg/articles-inspirations/singapore-s-ageing-population-and-nursing-looking-to-the-future. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 4.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Ministry of Health Work Seminar 2021 Opening Address by Mr Ong Ye Kung, Minister of Health, 25 May 2021, (Part 1 of 2). 2021. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/ministry-of-health-work-plan-seminar-2021-opening-address-by-mr-ong-ye-kung-minister-for-health-25-may-2021-(part-1-of-2). Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 5.Moller AC, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and public policy: improving the quality of consumer decisions without using coercion. J Public Policy Mark. 2006;25:104–16. 10.1509/jppm.25.1.104. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health, Singapore. Managing healthcare cost increases. 2020. https://www.moh.gov.sg/news-highlights/details/managing-healthcare-cost-increases. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 7.Ministry of Health, Singapore. White Paper on, Healthier SG. 2022 https://www.healthiersg.gov.sg/resources/white-paper/. Accessed 9 Oct 2022.

- 8.Poteete AR, Janssen MA, Ostrom E. Working together: collective action, the commons, and multiple methods in practice. New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Png M. Catalysing Movements for Health Singapore. 2021. https://moht.com.sg/catalysing-movements-for-health/. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 10.Mathie A, Cunningham G. From clients to citizens: Asset-based community development as a strategy for community-driven development. Dev Pract. 2003;13(5):474–86. 10.1080/0961452032000125857. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen T, Crouch A, Topp SM. Community participation and empowerment approaches to Aedes mossquito management in high-income countries: a scoping review. Health Promot Int. 2021;36:505–23. 10.1093/heapro/daaa049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waterlander WE, Luna Pinzon A, Verhoeff A, den Hertog K, Altenburg T, Dijkstra C, et al. A system dynamics and participatory action research approach to promote healthy living and a health weight among 10-14-year-old adolescents in Amsterdam: the LIKE programme. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4928. 10.3390/ijerph17144928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations Children’s Fund. Social and behaviour change. n.d. https://www.unicef.org/social-and-behaviour-change. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 14.Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon ZJL, Hobbs L, Michie S. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev. 2015;9:323–44. 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kok G, Gottlieb NH, Peters GJ, Mullen PD, Parcel GS, Ruiter RA, et al. A taxonomy of behaviour change methods: an intervention mapping approach. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10:297–12. 10.1080/17437199.2015.1077155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satell G. Cascades: how to create a movement that drives transformational change. New York: McGraw Hill Professional; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunton G, Oliver S, Thomas J. Innovations in framework synthesis as a systematic review method. Res Synth Methods. 2020;11:316–30. 10.1002/jrsm.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butterfoss FD, Kegler MC. The community coalition action theory in emerging practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clavier C, de Leeuw E. Healthy promotion and the policy process. Oxford: OUP Oxford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahn A. Theory and practice of social planning. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman J. Three models of community organisation practice, their mixing and phasing. In: Cox FM, Erlich JL, Rothman J, Tropman JE, editors. Strategies of community organisation: a book of readings. Adelaide: Peacock; 2004. pp. 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Snow DA. Framing processes, ideology, and discursive fields. New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences – a practical guide. New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garritty C, Gartkehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane rapid reviews methods group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodman MS, Sander Thompson VL. The science of stakeholder engagement in research: classification, implementation, and evaluation. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7:486–91. 10.1007/s13142-017-0495-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health: from process to outcomes. New Jersey: Wiley; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.The World Bank Group. Country and lending groups. 2022. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 28.Hildon ZJ, Allwood D, Black N. Impact of format and content of visual display of data on comprehension, choice and preference: a systematic review. IJQHC. 2012;24:55–64. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centre for Evidence-Based Management. Critical appraisal of a case study. 2019. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/Critical-Appraisal-Questions-for-a-Case-Study.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2022.

- 30.Lai AYK, Stewart SM, Wan ANT, Shen C, Ng CKK, Kwok LT, et al. Training to implement a community program has positive effects on health promoters: JC FAMILY project. Transl. Behav. Med. 2018;8:838–50. 10.1093/tbm/iby070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lai AY, Stewart SM, Wan A, Fok H, Lai HYW, Lam TH, et al. Development and evaluation of a training workshop for lay health promoters to implement a community-based intervention program in a public low rent housing estate: the Learning Families Project in Hong Kong. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0183636. 10.1371/journal.pone.0183636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan H, Zhang R, Wei C, Li J, Xu J, Yang H, et al. A peer-led community-based rapid HIV testing intervention among untested men who have sex with men in China: an operational model of expansion of HIV testing and linkage to care. Sex Transm Infect. 2014;90:388–93. 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aw S, Koh GCH, Tan CS, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJM, Harding SC, et al. Exploring the implementation of the community for successful ageing (ComSA) program in Singapore: lessons learnt on program delivery for improving BioPsychoSocial health. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:263. 10.1186/s12877-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeda M, Tada T. Development of a mutual-assistance capability training program to safeguard the health of local residents in evacuation shelters after a disaster. J Med Invest. 2014;61:94–102. 10.2152/jmi.61.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blake H, Lai B, Coman E, Houdmont J, Griffiths A, Move-It. A cluster-randomised digital worksite exercise intervention in China: Outcome and process evaluation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3451. 10.3390/ijerph16183451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Schaffer D, Tso LS, Tang S, Tang W, Huang S, et al. Innovation contests to promote sexual health in China: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:78. 10.1186/s12889-016-4006-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Shinkai S, Yoshida H, Taniguchi Y, Murayama H, Nishi M, Amano H, et al. Public health approach to prevent frality in the community and its effect on healthy ageing in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:87–97. 10.1111/ggi.12726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito J, Haseda M, Amemiya A, Takagi D, Kondo K, Kondo N. Community-based care for healthy ageing: lessons from Japan. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:570–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watthayu N, Wenzel J, Panchareounworakul K. Applying qualitative data derived from a Rapid Assessment and Response (RAR) approach to develop a community-based HIV prevention program for adolescents in Thailand. JANAC. 2015;26:602–12. 10.1016/j.jana.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.So WKW, Kwong ANL, Chen JMT, Chan JCY, Law BMH, Sit JWH, et al. A theory-based and culturally aligned training program on breast and cervical cancer prevention for south Asian community health workers: a feasibility study. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42:E20–30. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wong JYH, Chan MMK, Lok KYW, Ngai VFW, Pang MTH, Chan CKY, et al. Chinese women health ambassadors programme: a process evaluation. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:2976–85. 10.1111/jocn.13638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aw S, Koh G, Oh YJ, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJM, Harding SC, et al. Explaining the continuum of social participation among older adults in Singapore: from ‘closed doors’ to active ageing in multi-ethnic community settings. J Aging Stud. 2017;42:46–55. 10.1016/j.jaging.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong A, Szeto S, Lung DWM, Yip PSF. Diffusing innovation and motivating change: adopting a student-led and whole-school approach to mental health promotion. J Sch Health. 2021;91:1037–45. 10.1111/josh.13094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murayama Y, Murayama H, Hasebe M, Yamaguichi J, Fujiwara Y. The impact of intergenerational programs on social capital in Japan: a randomised population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:156. 10.1186/s12889-019-6480-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winichagoon P. Scaling up a community-based program for maternal and child nutrition in Thailand. FNB. 2014;35:S27–33. 10.1177/15648265140352S104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HJ, Hwang SM, Lee IY, Cho JP, Kwon MO, Jung JH, et al. Implementation and results of a survey on safe communtiy programs in Gangbuk-gu, Korea: focusing on participants at a local public health center. JPMPH. 2014;47:47–56. 10.3961/jpmph.2014.47.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aw S, Koh GCH, Tan CS, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJM, Harding SC, et al. Promoting BioPsychoSocial health of older adults using a community for successful ageing program (ComSA) in Singapore: a mixed-methods evaluation. Soc sci med. 2020;258:113104. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lai CCS, Law YW, Shum AKY, Ip FWL, Yip PSF. A community-based response to a suicide cluster. Crisis. 2020;41:163–71. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sansiritaweesook G, Kanato M. Development of the model for local drowning surveillance system in Northeastern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thail. 2015;98:S1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su A, Koh GCH, Tan CS, Hildon ZJL. Theory and design of the community for successful ageing (ComSA) program in Singapore: connecting BioPsychoSocial health and quality of life experience of older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:254. 10.1186/s12877-019-1277-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bae J, Cho J, Cho SI, Kwak M, Lee T, Bae CA. Application and developmental strategies for community-based injury prevention programs of the international safe communities movement in Korea. JKAN. 2015;45:910–18. 10.4040/jkan.2015.45.6.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao C, Zhou X, Wang F, Jiang M, Hesketh T. Care for left-behind children in rural China: a realist evaluation of a community-based intervention. CYSR. 2017;82:239–45. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.034. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Haya MAN, Ichikawa S, Shibagaki Y, Akame Machijuu Genki Project Community Advisory Board, Wakabayashi H, Takemura Y. The healthy akame! Community - government - university collaboration for health: a community-based participatory mixed-metho approach to address health issue in rural Japan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;82:239–45. 10.1186/s12913-020-05916-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Su A, Koh GCH, Oh YJ, Wong ML, Vrijhoef HJ, Harding SC, et al. Interacting with place and mapping community needs to context: comparing and triangulating multiple geospatial-qualitative methods using the focus-expand-compare approach. Methodol Innov. 2021;14:205979912098777. 10.1177/2059799120987772.

- 55.Chow EHY, Tiwari A. Addressing the needs of abused Chinese women through a community-based participatory approach. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52:242–49. 10.1111/jnu.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heo HH, Jeong W, Che XH, Chung H. A stakeholder analysis of community-led collaboration to reduce health inequity in a deprived neighbourhood in South Korea. Glob Health Promot. 2020;27:35–44. 10.1177/1757975918791517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang K, Fu H, Longfield K, Modi S, Mundy G, Firestone R. Do community-based strategies reduce HIV risk among people who inject drugs in China? A quasi-experimental study in Yunnan and Guangxi provinces. HRJ. 2014;11:15. 10.1186/1477-7517-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tricco AC, Cardoso R, Thomas SM, Motiwala S, Sullivan S, Kealey MR, et al. Barriers and facilitators to uptake of systematic reviews by policy makers and health care managers: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2016;11:4. 10.1186/s13012-016-0370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haldane V, Chuah FL, Srivastava A, Singh SR, Koh GCH, Seng CK, et al. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: a systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0216112. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuah FL, Srivastava A, Singh SR, Haldane V, Koh GCH, Seng CK, et al. Community participation in general health initiatives in high and upper-middle income countries: a systematic review exploring the nature of participation, use of theories, contextual drivers and power relations in community participation. Soc sci med. 2018;213:106–22. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The study is reported in accordance with Cochrane rapid review methods recommendations (Supplementary File 1). The screened dataset constitutes the intellectual property of the study team and is not publicly available. It can be shared upon reasonable request to the review team.