Abstract

Purpose

Treatment options for leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) are limited. A recent phase 2 study found that proton craniospinal irradiation (pCSI) was well-tolerated and improved survival. We report our experience with pCSI for solid-tumor LM.

Methods and Materials

This is a retrospective review of patients treated with pCSI for solid-tumor LM from December 2020 to January 2024 at our center. Patient characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Median overall survival and median central nervous system progression-free survival from the first day of pCSI were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Results

We identified 45 patients who completed pCSI. The median age was 54 years (range, 23-79); 73% were female, and 53% lived more than 100 miles from our center. Breast cancer (53%), lung cancer (20%), and melanoma (9%) were the most common primary cancers; 51% of patients had stable systemic disease at LM diagnosis. All had imaging evidence of LM, and 64% of cases were confirmed using cytologic examination of the cerebrospinal fluid. Eighty percent had symptomatic LM, and the median Karnofsky performance scale at LM diagnosis was 80. The median time from primary cancer diagnosis to LM detection was 23.1 months (range, 0-221.3). Fifty-three percent of patients had active brain metastasis at LM diagnosis; 33% of all patients had received prior intracranial radiation. The median time from simulation to pCSI start was 12 days. At the first visit following pCSI, the median Karnofsky performance scale score was 70. During or right after radiation, 76% of patients reported nausea, 51% headache, and 31% fatigue. Following pCSI, 4% received intrathecal chemotherapy, 67% systemic therapy, and 9% hospice care; 18% were observed and 2% lost to follow-up. Median overall survival was 13.7 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 11.2 to not reached), and median progression-free survival was 6.5 months (95% CI, 4.9-12.8).

Conclusions

The outcomes in our cohort are comparable to those recently reported in a phase 2 trial. Further study is indicated to determine the optimal candidates for pCSI and sequential therapies.

Introduction

Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM) is a condition in which cancer spreads to the leptomeninges and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Historically, overall survival for patients diagnosed with LM from solid tumors is only several months.1 Treatment options are limited and may include brain and spine radiation, intrathecal chemotherapy, or systemic treatment with blood-brain barrier penetration potential.2 For decades, typical radiation treatment has been photon-involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT). A phase 2 study for patients with LM from non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and breast cancer compared IFRT with proton craniospinal irradiation (pCSI) and found that the latter option was well tolerated with better survival.3 Subsequently, pCSI has been adopted at several cancer centers, but real-world cohort study data on outcomes are limited. Thus, our objective was to report survival outcomes and adverse effects for patients treated with pCSI for solid-tumor LM.

Methods and Materials

Study design

This is a retrospective review of all adult patients who completed pCSI for LM from solid tumors from December 2020 to January 2024 at our center. We obtained study approval from our institutional review board prior to collecting the data.

Radiation therapy

All patients received pCSI encompassing the whole brain and spinal canal through the inferior extent of the thecal sac, with the majority expected to receive 30 GyRBE in 10 daily fractions; the final dose and fractionation were at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist. All patients had at least 1 in-person clinic visit with neuro-oncology and/or radiation oncology before simulation, 1 during pCSI, and 1 after all sessions were completed. Further details about the pCSI technique at our institution were published previously.4

Measures and statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from electronic health records and summarized using descriptive statistics. Median overall survival (mOS) and median central nervous system progression-free survival (mPFS) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from the first day of pCSI were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. Progression was determined using radiographic findings. White blood cell (WBC) count, hemoglobin level, and platelet count were each modeled using mixed-effect analysis of variance relative to discrete time points: within 2 weeks prior to pCSI, within 4 weeks after pCSI, and 8 weeks after pCSI (prior2, post4, and post8, respectively), with clustering by patient to control for repeated measures. Normal ranges were defined as 4.1 to 10.5 K cells/μL for WBC, 12.2 to 15.3 g/dL for hemoglobin, and 160 to 397 K cells/μL for platelet count. Catseye plots were produced to illustrate the normal distribution of the model-adjusted means.5 All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.3.1).

Results

Patient cohort

We identified 51 patients within the study period who received at least 1 session of radiation. Out of 6 patients who did not complete pCSI, 2 patients were found to have disease progression during treatment and 4 could not tolerate the remaining sessions. A total of 45 patients had completed pCSI and were included in the final analysis. Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics. The median age was 54 years (range, 23-79), and 73% of the patients were female. About half (53%) lived 100 miles or more from our center, with a median distance of 144 miles. Breast cancer (53%), lung cancer (20%; 8 patients with non-small cell and 1 with atypical neuroendocrine), and melanoma (9%) were the most common primary cancers. Half of the patients (53%) had stable systemic disease at the time of LM detection. All had imaging evidence of LM, and 64% had confirmation using cytologic examination of the CSF. Eighty percent had symptomatic LM; among these patients, 31% experienced headache and/or cranial nerve deficits, and 16% had limb weakness or numbness. The median Karnofsky performance scale (KPS) score at LM diagnosis was 80 (range, 50-90).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 45)

| Characteristic | No. of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 33 (73) |

| Male | 12 (27) |

| Primary language | |

| English | 44 (98) |

| Spanish | 1 (2) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 31 (69) |

| Black or African American | 6 (13) |

| Asian | 4 (9) |

| Other | 3 (7) |

| Declined to answer | 1 (2) |

| Distance from residence to treatment center | |

| < 100 miles | 21 (47) |

| ≥ 100 miles | 24 (53) |

| Primary malignancy | |

| Breast cancer | 24 (53) |

| Lung cancer | 9 (20) |

| Melanoma | 4 (9) |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 2 (4) |

| Others | 6 (13) |

| Systemic disease at the time of LM | |

| Stable | 23 (51) |

| Progressive | 22 (49) |

| How LM was diagnosed | |

| Imaging | 45 (100) |

| Cytology | 29 (64) |

| Presence of symptoms | 36 (80) |

| LM symptoms | |

| Headache | 14 (31) |

| Cranial nerves-related | 14 (31) |

| Limb weakness/numbness | 7 (16) |

| Seizure | 4 (9) |

| Prior intracranial radiation | |

| Yes | 15 (33) |

| No | 30 (67) |

| Parenchymal metastasis status at LM detection | |

| Active | 24 (53) |

| Inactive or none | 21 (47) |

| Received 30 GyRBE in 10 daily fractions | |

| Yes | 39 (87) |

| No | 6 (13) |

Abbreviation: LM = leptomeningeal metastasis

Table 2 shows clinical characteristics and outcomes. The median time from primary cancer diagnosis to LM detection was 23.1 months (range, 0-221.3). Fifty-three percent of patients had active brain metastasis at the time of LM detection. Eleven percent of patients had a ventriculoperitoneal or Ommaya with reservoir shunt placement. One-third of patients had received prior intracranial radiation, as shown in Table 1. The median time from LM detection on imaging to pCSI simulation was 16 days (range, 2-624), and the median time from simulation to pCSI start was 12 days (range, 6-41). Three patients received concurrent systemic therapies (2 osimertinib and 1 trastuzumab deruxtecan) while undergoing pCSI.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes

| Characteristic | Median | Lowest | Highest | Median survival (95% CI), mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary malignancy diagnosis to LM detection using imaging, mo | 23.1 | 0 | 221.3 | |

| Primary malignancy diagnosis to parenchymal metastasis detection using imaging, mo | 14.7 | 0 | 162.0 | |

| LM detection using imaging to death or loss to follow-up, mo | 6.9* | 2.17 | 27.5 | 15.3 (11.6- NR) |

| LM detection using imaging to pCSI simulation, d | 16 | 2 | 624 | |

| LM detection to the first fraction, d | 12 | 0 | 41 | |

| KPS score prior to start of pCSI | 80 | 50 | 90 | |

| KPS score at first evaluation after pCSI | 70 | 50 | 90 | |

| OS (first fraction to death or loss to follow-up), mo | 4.7* | 1.1 | 26.33 | 13.7 (11.2-NR) |

| PFS (first fraction to CNS progression, death, or loss to follow-up), mo | 4.3* | 0.57 | 18.37 | 6.5 (4.9-12.8) |

Abbreviations: CNS = central nervous system; KPS = Karnofsky performance scale; LM = leptomeningeal metastasis; NR = not reached; OS = overall survival; pCSI = proton craniospinal irradiation; PFS = progression-free survival.

Does not include censored data.

Outcomes

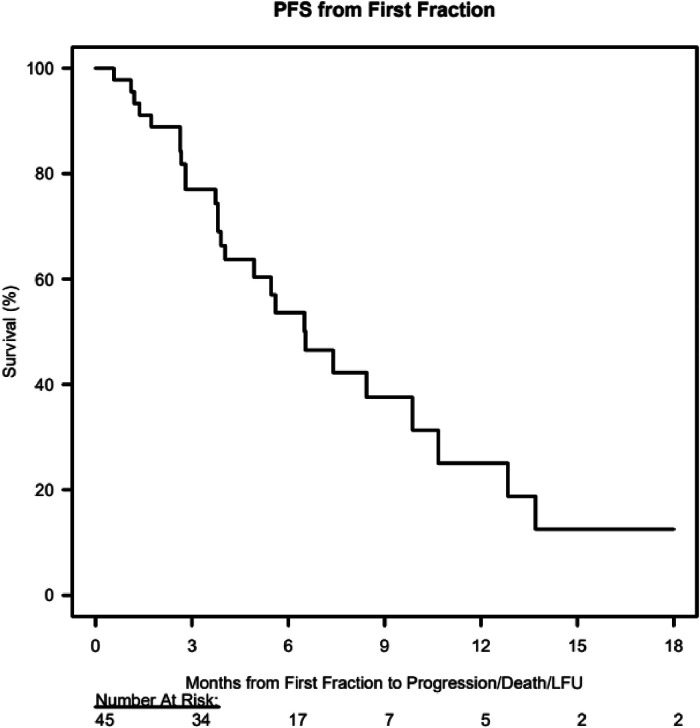

At the first visit following pCSI, the median KPS score was 70 (range, 50-90). For patients who completed pCSI, mOS was 13.7 months (95% CI, 11.2 to not reached), and mPFS was 6.5 months (95% CI, 4.9-12.8), as shown in Table 2 and Figure 1, Figure 2. For analysis of all 51 patients (including those who did not complete pCSI), mOS was 12.8 months (95% CI, 5.2 to not reached) and mPFS was 5.6 months (95% CI, 3.8 to 10.7).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival from the first proton craniospinal irradiation fraction.

Abbreviation: LFU = loss to follow-up.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of progression-free survival from the first proton craniospinal irradiation fraction.

Abbreviations: PFS = progression-free survival; LFU = loss to follow-up.

Stratified using primary malignancy (for patients who completed pCSI), mOS for patients with breast cancer was not reached, for patients with lung cancer was 13.7 months (95% CI, 3.8 to not reached), and for all other patients, 3.9 months (95% CI, 2.7 to not reached). mPFS for patients with breast cancer was 9.9 months (95% CI, 6.5 to not reached), for patients with lung cancer 8.4 months (95% CI, 3.7 to not reached), and for all others 3.9 months (95% CI, 2.7 to not reached). Figures E1 and E2 illustrate these Kaplan-Meier curves. For a combined cohort of 32 patients, including only those with breast cancer and NSCLC, mOS was not reached, and mPFS was 8.43 months (95% CI, 6.5 to not reached).

Following pCSI, 67% were dispositioned to systemic therapy, 18% to surveillance, 9% to hospice care, 4% to intrathecal chemotherapy, and 2% were lost to follow-up.

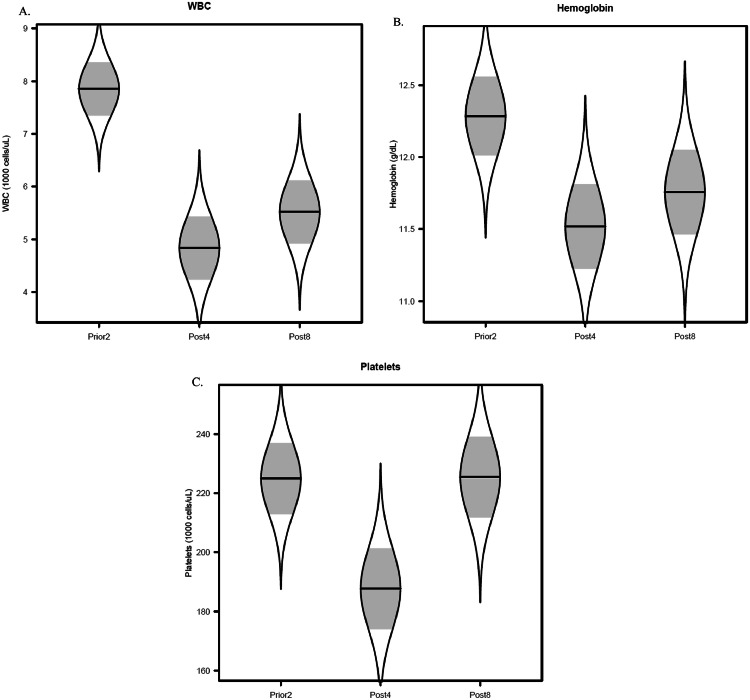

Adverse effects

For nonhematologic events, 76% of patients had nausea, 51% headache, 31% fatigue, and 4% dizziness during or right after radiation. For hematologic events, as shown in Fig. 3, model-adjusted mean WBC was 7.9 K cells/μL at prior2 (95% CI, 6.9-8.8), 4.8 K cells/μL at post4 (95% CI, 3.7-6.0), and 5.5 K cells/μL at post8 (95% CI, 4.3-6.7). Model-adjusted mean hemoglobin level was 12.3 g/dL at prior2 (95% CI, 11.7-12.8), 11.5 g/dL at post4 (95% CI, 10.9-12.1), and 11.8 g/dL at post8 (95% CI, 11.2-12.3). Model-adjusted mean platelet count was 225 K cells/μL at prior2 (95% CI, 201-249), 188 K cells/μL at post4 (95% CI, 161-215), and 225 K cells/μL at post8 (95% CI, 199-252).

Figure 3.

Catseye plots showing the distribution of hematological values before and after proton craniospinal irradiation (pCSI). Measurements were taken at 3 time points: within 2 weeks prior to pCSI (prior2), within 4 weeks after pCSI (post4), and 8 weeks after pCSI (post8). (A) White blood cell (WBC) count; (B) hemoglobin level; (C) platelet count. Plots show the normal distribution of the model-adjusted means from the mixed-effect model, with shaded ± standard error intervals.

Discussion

Although the ideal radiation volume for LM is the entire CSF space, conventional photon CSI has significant adverse effects including fatigue, vomiting, and myelosuppression.6,7 Therefore, photon radiation to the whole brain with or without focal spinal volumes has long been used to palliate LM.8 pCSI substantially reduces radiation dose to the bones and internal organs while still covering the entire neuroaxis.9,10

Yang et al3 in a phase 2 randomized trial comparing pCSI and IFRT for LM for breast cancer and NSCLC, reported OS in the pCSI group of 9.9 months (95% CI, 7.5 to not reached) and PFS of 7.5 months (95% CI, 6.6 to not reached); both survival outcomes were significantly better than those of IFRT. The OS and PFS outcomes in our retrospective cohort are comparable to those of this trial. Yang et al3 further reported that 19% of the patients in the pCSI group had experienced nausea, 17% headache, and 25% fatigue. In comparison, our cohort had a higher percentage of these nonhematologic adverse events. In addition, our findings indicated an overall numerical decrease in WBC count, hemoglobin level, and platelet count 4 weeks after radiation, but these values recovered by 8 weeks after pCSI, and none of the 95% CI minimum hematologic values were critically low.

Our study further highlights that most patients went on to receive systemic therapies, with fewer patients opting for intrathecal chemotherapy, possibly caused by the recent availability of blood-brain barrier-penetrating systemic therapy options for some subsets of patients.11 Some patients preferred comfort-based care or surveillance only through providers’ expert opinions; thus, more studies are needed to better understand the selection of the best candidates for pCSI and subsequent therapies.

Our study comes with several limitations. Not all patients with LM who were evaluated at our center were candidates for pCSI, depending on their functional status, insurance coverage, and travel feasibility; they may also simply be dispositioned to systemic or intrathecal therapies. Hence, we were not able to accurately determine the number of patients who could be eligible for pCSI but did not pursue this treatment or who could not wait to start pCSI. We also did not collect data on steroid usage, so we could not comment on their relationship with the adverse events. Furthermore, while we were able to report on adverse events from pCSI, we could not describe their grading accurately by chart review. Similarly, it was difficult to capture precisely whether those reported adverse events were definitely related to the radiation. Finally, our study population was composed mainly of patients with breast and lung cancers, so its generalizability for LM from other solid tumors is limited.

Conclusion

Our outcomes data are comparable to those recently reported in a phase 2 study. pCSI should be considered as a treatment option for appropriately selected patients with LM from solid tumors. Further study is indicated to determine the optimal candidates for pCSI, the sequencing of pCSI with other therapies, and the choice of subsequent therapies.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Ninetto, Senior Scientific Editor in the Research Medical Library at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for editing this article. Clark R. Andersen performed the statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Research data are not available at this time.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.adro.2024.101697.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Marenco-Hillembrand L, Bamimore MA, Rosado-Philippi J, et al. The evolving landscape of leptomeningeal cancer from solid tumors: a systematic review of clinical trials. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:685. doi: 10.3390/cancers15030685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rinehardt H, Kassem M, Morgan E, et al. Assessment of leptomeningeal carcinomatosis diagnosis, management and outcomes in patients with solid tumors over a decade of experience. Eur J Breast Health. 2021;17:371–377. doi: 10.4274/ejbh.galenos.2021.2021-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang JT, Wijetunga NA, Pentsova E, et al. Randomized phase II trial of proton craniospinal irradiation versus photon involved-field radiotherapy for patients with solid tumor leptomeningeal metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:3858–3867. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.01148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giebeler A, Newhauser WD, Amos RA, Mahajan A, Homann K, Howell RM. Standardized treatment planning methodology for passively scattered proton craniospinal irradiation. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cumming G. The new statistics: why and how. Psychol Sci. 2014;25:7–29. doi: 10.1177/0956797613504966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Shafie RA, Böhm K, Weber D, et al. Outcome and prognostic factors following palliative craniospinal irradiation for leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:789–801. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S182154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devecka M, Duma MN, Wilkens JJ, et al. Craniospinal irradiation (CSI) in patients with leptomeningeal metastases: risk-benefit-profile and development of a prognostic score for decision making in the palliative setting. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:501. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06984-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Shafie RA, Böhm K, Weber D, et al. palliative radiotherapy for leptomeningeal carcinomatosis-analysis of outcome, prognostic factors, and symptom response. Front Oncol. 2018;8:641. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown AP, Barney CL, Grosshans DR, et al. Proton beam craniospinal irradiation reduces acute toxicity for adults with medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breen WG, Geno CS, Waddle MR, et al. Proton versus photon craniospinal irradiation for adult medulloblastoma: A dosimetric, toxicity, and exploratory cost analysis. Neurooncol Adv. 2024;6 doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdae034. vdae034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alvarez-Breckenridge C, Remon J, Piña Y, et al. Emerging systemic treatment perspectives on brain metastases: moving toward a better outlook for patients. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2022;42:1–19. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_352320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.