Abstract

Evolutionarily conserved, peer-directed social behaviors are essential to participate in many aspects of human society. These behaviors directly impact psychological, physiological, and behavioral maturation. Adolescence is an evolutionarily conserved period during which reward-related behaviors, including social behaviors, develop via developmental plasticity in the mesolimbic dopaminergic “reward” circuitry of the brain. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is an intermediate reward relay center that develops during adolescence and mediates both social behaviors and dopaminergic signaling. In several developing brain regions, synaptic pruning mediated by microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, is important for normal behavioral development. We previously demonstrated that during adolescence, in rats, microglial synaptic pruning shapes the development of NAc and social play behavior in males and females. In this report, we hypothesize that interrupting microglial pruning in NAc during adolescence will have persistent effects on male and female social behavior in adulthood. We found that inhibiting microglial pruning in the NAc during adolescence had different effects on social behavior in males and females. In males, inhibiting pruning increased familiar exploration and increased nonsocial contact. In females, inhibiting pruning did not change familiar exploration behavior but increased active social interaction. This leads us to infer that naturally occurring NAc pruning serves to reduce social behaviors toward a familiar conspecific in both males and females.

Keywords: adolescent, plasticity, rodent, sex differences, social

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Social interactions are a crucial part of existence across the lifespan (Haslam et al., 2021; Schweinfurth, 2020; Siracusa et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2016). Studying the development of normative social behavior is critical for recognizing the evolutionary goals of sociability (Cavigelli & Caruso, 2015; Li et al., 2021) and the vulnerability conferred by abnormal social behavior (Almquist et al., 2018; Burke et al., 2017; Cameron et al., 2017; Hodges et al., 2017). Indeed, negative social experiences are predictive of negative outcomes both mentally (Al Omran et al., 2022; Von Frijtag et al., 2002; Weintraub et al., 2010) and physically (Kang et al., 1998; Okuda et al., 2022; Schneider et al., 2016). Thus, a better understanding of the neural mechanisms of social development may be therapeutically relevant; as positive social support is shown to improve outcomes in cognitive aging (Crimmins, 2020; Frey et al., 2021; Leblanc & Ramirez, 2020), recovery post-cardiac events (McNeal et al., 2014), and recovery from substance abuse (Boisvert et al., 2008; Venniro et al., 2018), among others. Adolescence is an evolutionarily conserved period during which reward-related behaviors, including social behaviors, develop via developmental plasticity in the mesolimbic dopaminergic “reward” circuitry of the brain (Brenhouse & Schwarz, 2016; Manduca et al., 2016). The nucleus accumbens (NAc) is an intermediate reward relay center that develops during adolescence (Bayassi-Jakowicka et al., 2021; Huppe-Gourgues & O’Donnell, 2012; Kopec et al., 2018; Martz et al., 2022; Orihuel et al., 2021) and mediates both social behaviors and dopaminergic signaling (Halbout et al., 2019; Manduca et al., 2016). In rodents, the NAc is particularly sensitive to social experience: Both positive and negative social experiences during adolescence produce long-term effects in both the neuroanatomy of the NAc and matured social behaviors (Bendersky et al., 2021; Lemos et al., 2021).

The maturation of the NAc is driven in part by synaptic pruning, the process by which extra neurons and synaptic connections are eliminated in order to increase the efficiency of neuronal transmissions, which refines dopaminergic signaling differently in either sex (Andersen et al., 1997; Juraska & Drzewiecki, 2020). In several developing brain regions, complement system proteins (e.g., C3) facilitate synaptic pruning by binding to complement receptor 3 (CR3) on microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain (Grabert et al., 2016; Schafer et al., 2012; Soteros & Sia, 2022). Sex-specificity exists in microglial activity (Lenz et al., 2013; Han et al., 2021) and complement-mediated pruning (Prilutsky et al., 2017; Westacott & Wilkinson, 2022) during adolescence. More specifically, we demonstrated in rats that C3-microglial synaptic pruning mediates NAc and social development during sex-specific adolescent periods: pre-to-early adolescence in females (postnatal day (P)22–30) and early-to-mid adolescence in males (P30–40), and via sex-specific synaptic pruning targets (dopamine D1 receptors in males, but not females) (Kopec et al., 2018). In addition, altering microglia synaptic pruning in early life was shown to produce persistent changes in social behavior in both males and females (Nelson et al., 2021). All together this suggests that altering microglial synaptic pruning in the NAc during adolescence could impact rat adult social behavior and have persistent sex-specific effects. In the following experiments, we seek to identify whether inhibiting NAc pruning during sex-specific adolescent periods would impact social behaviors in adult animals. To test this, we inhibited C3-microglial pruning in the NAc during each sex’s respective pruning period with a single, bilateral microinjection of neutrophil inhibitory factor (NIF), a highly specific competitive CR3 antagonist (Muchowski et al., 1994; Smirnov et al., 2023). Rats were permitted to age into adulthood, and then we assessed their social behavior. We found that in males, inhibiting pruning increased familiar exploration in the social novelty preference (SNP) test and increased nonsocial contact in the familiar social interaction test. In females, inhibiting pruning increased active social interaction in the familiar social interaction test. Overall, our results demonstrate that interfering with natural NAc pruning at sex-specific timepoints increased social behavior response in adult female and male rats. Our data suggests that naturally occurring NAc pruning serves to reduce social behaviors toward a familiar conspecific in both males and females.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Animals

Adult male and female Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased for breeding (Envigo) and group-housed with ad-libitum access to food and water in cages with cellulose bedding changed twice weekly. Colonies were maintained in a 12:12 light:dark cycle (lights on at 07:00) in a temperature and humidity-controlled room. Litters were culled to a maximum of 12 pups per dam between postnatal day 2 (P2) and P5. At P21 pups were weaned into same-sex pairs. All rats were paired with same-sex pair littermates. Exceptions were made when there were litters of uneven sex-breakdown, allowing two same-sex pairs from different litters, born on the same day to be paired. To conduct the behavior tests, the litter effects were methodologically controlled for. Each group of rats tested was composed of 4–5 L. For each litter, no less than two and no more than four pups were allocated to each group (NIF male, NIF female, PBS male, and PBS females). Thus, the rat litter was not confounded with experimental design because more than 1 litter was used per experimental group and each litter was represented in both control and experimental groups for both sexes. Rats were housed in the Animal Resources Facility at Albany Medical College, and all animal work was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Albany Medical College.

2.2 |. Bilateral stereotactic infusion into the NAc

The conditions of stereotactic procedures were identical to Kopec et al. (2018), which demonstrated the successful administration of NIF into the NAc in order to block complement C3-mediated pruning by microglia in the NAc, through the measured increase of D1r in adolescent male rats. A total of 32 male (P30) and 27 female (P22) rats were maintained under isoflurane anesthesia for the entire surgical procedure (2%–3%; KENT SCIENTIFIC). The scalp was cut midsagittal, and Bregma was marked, after which two bilateral holes were drilled at AP +2.25 mm, ML ±2.5 mm, DV −5.75 mm coordinates in P30 males, and AP +2.7 mm, ML ±2.4 mm, DV −5.55 mm in P22 females. A Hamilton syringe (Hamilton 7105) was lowered to depth at a 10◦ angle and left in place for 1 min. We confirmed that our stereotactic coordinates were correct by infusing a bromophenol blue dye in saline solution (Figure S2). NIF (1× reconstitution, 200 μg/mL NIF; R&D Systems) or vehicle (sterile PBS) was injected at a rate of 50 nL/min (60 ng in 300 nL in P30 males, 50 ng in 250 nL in P22 females). The syringe was left in place for 5 min post-infusion and then retracted, and the procedure was repeated on the other hemisphere; for all surgeries, the side of the first injection was randomized. The syringe was thoroughly cleaned with cleaning solution (Hamilton Cleaning Concentrate, Hamilton) and distilled water before being used for the next surgery. Saline was used to wet the scalp, and then the wound was closed with surgical staples and coated topically with Bupivacaine. An injection of Ketophen (5 mg/kg) was administered subcutaneously, and the animal was placed in a clean cage with a food pellet and gelatinized water for recovery. Rats’ breathing was monitored, and consciousness was confirmed prior to being returned to the animal facility. Rats were repaired with their cagemates after 2–3 h of recovery and monitored for the next 72 h. Animals received Ketophen (5 mg/kg) for two additional days following surgery (three total injections, once per day), and staples removed 10 days post-surgery. Rats were left undisturbed until behavioral testing in adulthood (Figure 1).

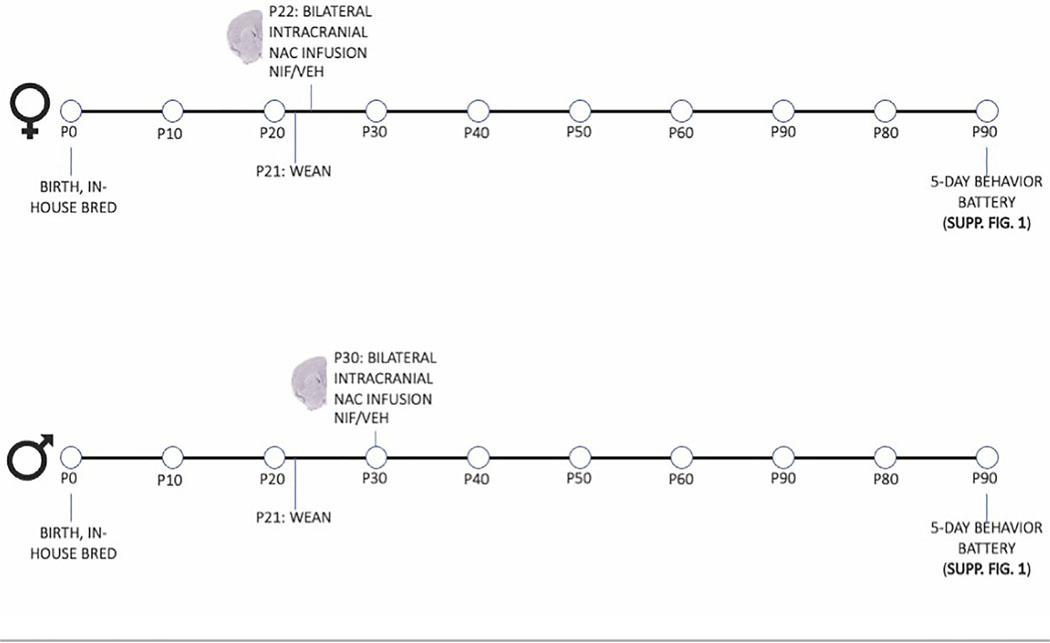

FIGURE 1.

Experimental design. Females and males were bred in-house and were treated with neutrophil inhibitory factor (NIF) or VEH at sex-specific times (females at P22, males at P30). At 3 months of age, animals of both sexes underwent the behavior battery discussed herein.

2.3 |. Behavioral tests

Experimental rats (∼P90) and their sex- and age-matched novel conspecifics were acclimated to experimenter handling and the behavior room for ∼5 min per animal for 3 weekdays preceding behavior tests. During the behavioral tests, females did not undergo estrous cycle monitoring. Animals underwent a 5-day behavior battery (e.g., Day 1: open field (OF), Day 2: novel social interaction, Day 3: familiar free social attention, Day 4: SNP, Day 5: social vs. object choice), one behavior test per day was performed, and task order was randomized for each week. No rats underwent more than one behavioral task per day. The order of behavioral test for each experimental group (NIF vs. PBS) was counterbalanced. All behavior tasks were recorded using ANY-Maze software and the first 5 min were hand-coded by blinded experimenters for analysis in Solomon Coder software (Andras Peter; solomoncoder.com). Social choice tasks (SNP and social versus object choice [SVO]): Experimental rats were first acclimated (10 min) in the empty three-chamber box, a black plexiglass behavior box consisting of three compartments: an experimental compartment flanked by two smaller compartments where stimuli (social and nonsocial) are securely housed. Stimuli are separated from the experimental compartment by a transparent plastic wall with several small holes not large enough for an animal to move across. Choice tasks were scored for time spent in either exploratory zone (i.e., next to either stimulus). The percentage of exploration was calculated using the time spent exploring the stimulus as a function of the total time spent in the corresponding half of the experimental compartment (e.g., the time spent exploring the nonsocial object divided by the total time spent on the nonsocial object chamber of the apparatus; Figure S1A) (de Franca Malheiros et al., 2020; Graf et al., 2023). Novel and familiar social interaction tests: Novel and familiar social interaction tests were performed in clean, empty rat housing cages. Rats were acclimated for ∼10 min to the interaction cages prior to each experiment. Novel social interaction was performed by placing an experimental animal and a novel age- and sex-matched conspecific in the same cage for 10 min. Familiar social interaction was performed by placing two familiar cage mates that had undergone the same adolescent manipulation in the same cage for 10 min. Cage mates were separated for ∼20 min prior to test. Interaction behaviors for each individual experimental animal were quantified by blinded hand-coding coding of time spent in four social behavior phenotypes: (1) Active social behavior is defined as the rat facing, and physically in contact with, the conspecific. (2) Passive social behavior occurs when the rat is facing the conspecific with no physical contact. (3) Nonsocial contact is when the rat is engaged in physical contact with the conspecific but is not facing the animal. (4) Nonsocial attention occurs if the rat is not facing nor in physical contact with the conspecific (Figure S1B). For the social interaction tests, each n represents the interaction between two animals. Open field test (OF): Rats were placed in a 40 cm × 40 cm polypropylene apparatus for 10 min; with an inner section measuring at 400 cm2, inner section entries were scored if the animal had both forepaws and shoulders within the inner section (Figure S1C).

2.4 |. Statistics

For all behavior tasks, Student’s two-tailed t-test (p ≤ .05) was used to compare NIF-treated to vehicle-treated animals of the same sex. Because surgeries were performed at different ages for each sex, corresponding to their respective NAc pruning periods, we could not compare directly between the sexes. Outliers were identified using the ROUT method (Q = 1%) and eliminated from analysis. For cages of three, only one pairing of data was included for the familiar interaction task, as post hoc analysis indicated significantly different responses to the familiar rat when it was used for a second test. Correlations for all behavior metrics against OF were calculated using Pearson’s r. Statistically significant r values were compared between NIF- and PBS-treated animals via Fisher’s r-to-z transformation to identify any significant change resulting from inhibition of pruning in the NAc, and a Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons was applied at a 10% false discovery rate cutoff. Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 9.5.0 and vassarstats.com.

3 |. RESULTS

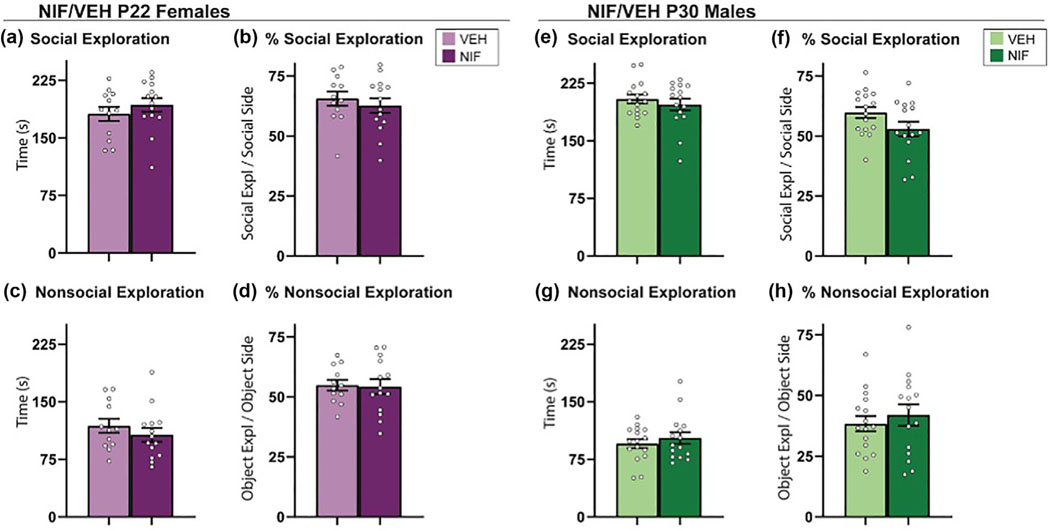

3.1 |. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning does not change social versus object choice behavior in either sex

SVO tests are a widely used assay for quickly and simply assessing sociability (Wöhr & Scattoni, 2013). To investigate whether inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence affects social versus object choice behavior in adult rats, we conducted this SVO choice test in both male and female rats that received either a microglial pruning inhibitor (NIF) or a vehicle control (VEH). It is known that rodents have a natural preference for novel social stimuli over novel object stimuli and under normal conditions will thus spend more time exploring the novel social stimulus. This was indeed the case in both males and females of both experimental groups, as shown in Figure 2. In addition, we show that inhibiting pruning during adolescence did not impact the behavioral parameters we measured during SVO in either sex (Figure 2). Specifically, we found no significant differences between the experimental and control groups in the time spent exploring the novel social stimulus or the novel object stimulus, or in the preference index for social versus object choice behavior (Figure 2). These results suggest that inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence does not affect social versus object choice behavior in adult rats.

FIGURE 2.

Social versus object choice. Inhibiting pruning in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) during adolescence did not impact the behavioral parameters measured in the social versus object choice tests in (a–d) females (VEH n = 12; neutrophil inhibitory factor [NIF] n = 14) or (e–h) males (VEH n = 16; NIF n = 15). Bar graphs represent average ± standard error of the mean. Student’s two-tailed t-test. *p < .05.

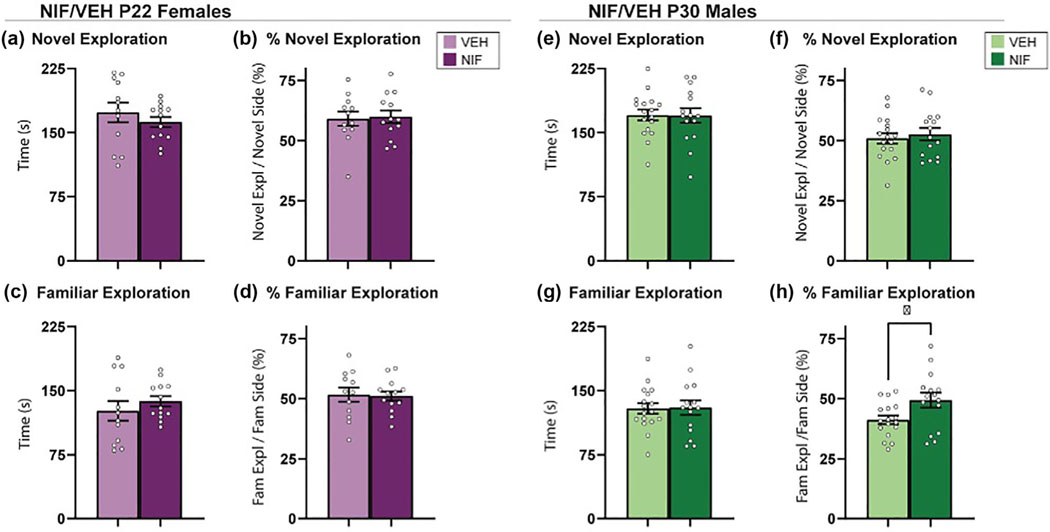

3.2 |. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning alters behavior toward a familiar partner during social novelty preference task in males, but not females

A relatively new variant of social choice tests is SNP (Smith et al., 2015, 2018), which provides the experimental animal with the opportunity to explore familiar and novel social stimuli in opposing sides of the behavior chamber. Novel and familiar social stimuli serve different purposes in a social network and evoke different social behaviors (Beery & Shambaugh, 2021). Rodents have a natural preference for social novelty over social familiarity and under normal conditions will thus spend more time exploring the novel social stimulus. In females, inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence did not change behavior in this test (Figure 3a–d). In males, inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence did not change the total amount of time spent exploring either stimulus (Figure 3e,g) but did increase the time spent exploring the familiar stimulus as a percentage of time in the familiar half of the arena (%exploration) (Figure 3f) (t(30) = 2.353, p = .0253). To this point, the data has not elucidated any changes in female social choice after NAc pruning. In males, the data shows subtle shifts in familiar-directed exploratory behavior in males, but no changes in behavior toward a novel social conspecific.

FIGURE 3.

Social novelty preference. (a–d) In females, the inhibition of nucleus accumbens (NAc) pruning during adolescence did not significantly regulate the behaviors measured in the social novelty preference test. (VEH n = 12; neutrophil inhibitory factor [NIF] n = 13). (e, f) In males, inhibition of NAc pruning during adolescence did not significantly influence exploration time or %exploration of a novel partner or (g) change time spent exploring familiar partner in males. (h) Inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence in males significantly increased %exploration of a familiar partner (VEH n = 17; NIF n = 15). Bar graphs represent average ± standard error of the mean. Student’s two-tailed t-test. *p < .05.

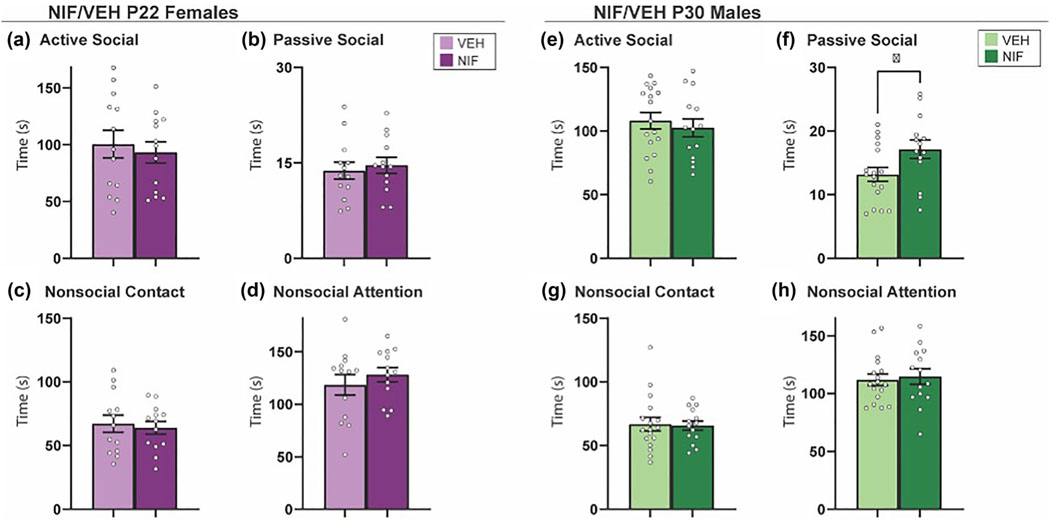

3.3 |. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning increases passive social interaction with a novel animal in males, but not females

Novel social interaction is a more naturalistic assessment of direct social interaction in rats (Kraeuter et al., 2019a; Schiavi et al., 2022). We hypothesized that a long-term consequence of inhibiting NAc pruning would be a persistent increase in active social behavior toward a novel conspecific. In males and females, four phenotypes of social behavior were quantified: active social interaction, passive social interaction, nonsocial contact, and nonsocial attention (see Figure S1 and Section 2 for more detail). There was no significant change in behavior toward a novel partner in females as a result of inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence (Figure 4a–d). Inhibiting NAc pruning in males during adolescence caused the rats to engage in more passive social interaction than control counterparts (t(29) = 2.218, p = .0346) (Figure 4f), but no other changes were detected in active social interaction, nonsocial contact, or nonsocial attention (Figure 4e,g,h). The data thus far have not supported our hypothesis that there will be increased sociability in NIF-treated females, and in males, the effects of NIF treatment have been subtle.

FIGURE 4.

Novel social interaction. (a–d) In females, inhibition of nucleus accumbens (NAc) pruning during adolescence did not significantly regulate the behaviors measured in the social novelty preference test (VEH n = 13; neutrophil inhibitory factor [NIF] n = 13). (e, f) In males, the inhibition of NAc pruning during adolescence did not significantly influence exploration time or %exploration of a novel partner or (g) change time spent exploring familiar partner in males. (h) Inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence in males significantly increased %exploration of a familiar partner (VEH n = 17; NIF n = 14). Bar graphs represent average ± standard error of the mean. Student’s two-tailed t-test. *p < .05.

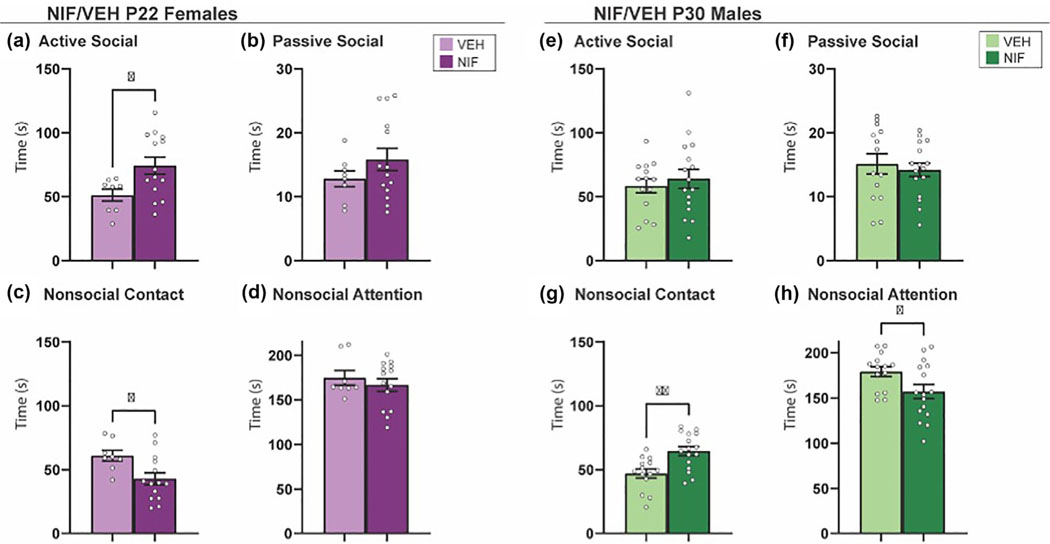

3.4 |. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning increases prosocial behaviors with a familiar cage mate in both males and females, in sex-specific ways

To fully assess the variety of social behaviors that adult rats display, rats were paired with their cage mates for familiar social interaction, a less commonly used assessment of direct social interaction in cohabitating rats (Varlinskaya & Spear, 2008). In our studies, cage mates have undergone the same adolescent manipulation (e.g., both vehicle- or NIF-treated), and animals were scored for the same phenotypes measured in novel social interaction. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning in females increased active social behavior (t(20) = 2.426, p = .0248) and reduced nonsocial contact (t(20) = 2.559, p = .0187) with a familiar cage mate in adulthood (Figure 5a,c). Inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence in males, on the other hand, increased nonsocial contact (t(28), p = .0016) and reduced nonsocial attention (t(28) = 2.247, p = .0327) (Figure 5g,h). This leads us to conclude that natural NAc pruning serves to downregulate familiar social behaviors, in males and females.

FIGURE 5.

Familiar social interaction. (a) Inhibiting nucleus accumbens (NAc) pruning during adolescence significantly increased active social attention and (c) significantly decreased nonsocial contact in females (VEH n = 8; neutrophil inhibitory factor [NIF] n = 14). (b, d) No significant changes were seen in passive social or nonsocial attention in females. (e and f) Inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence did not significantly change active or passive social attention in males. (g) However, inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence in males significantly increased nonsocial contact and (h) significantly decreased nonsocial attention (VEH n = 13; NIF n = 16). Bar graphs represent average ± standard error of the mean. Student’s t-test. *p < .05, **p ≤ .01.

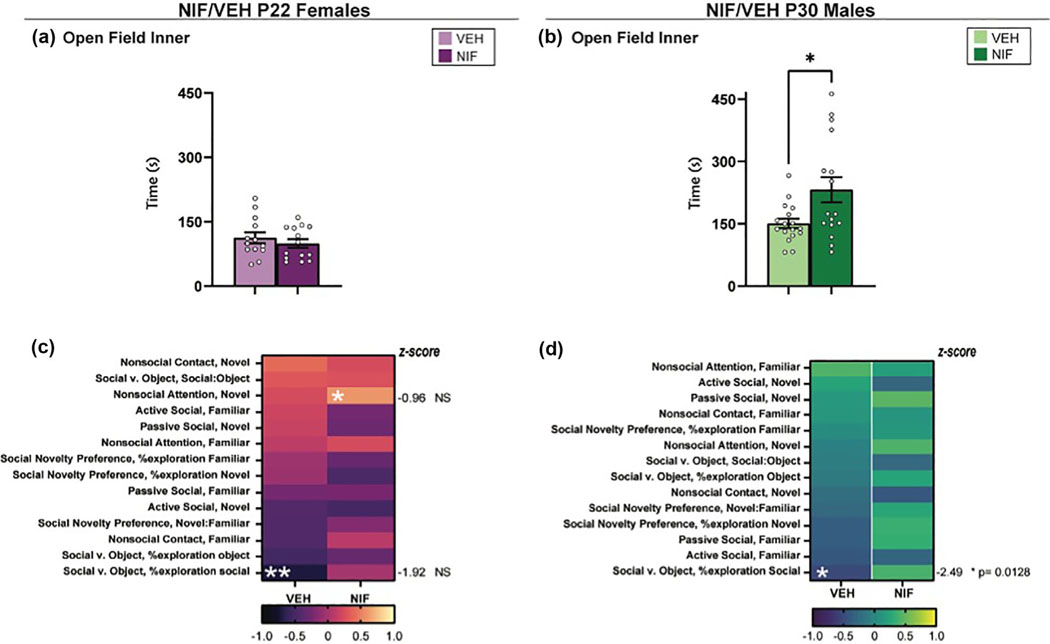

3.5 |. Inhibiting adolescent NAc pruning decreases anxiety-like/increases exploratory behaviors in males, but not females, in the open field

OF is a common task designed to assess anxiety-like and/or exploratory behaviors in rodents (Falco et al., 2014; Kraeuter et al., 2019b). We used this task to assess whether altered social behavior may be driven by changes in generalized anxiety-like and/or exploratory behaviors in rats that have had NAc pruning inhibited during adolescence. NIF-treated males spent significantly increased time in the inner zone of the OF compared to control males (t(31) = 2.552, p = .0159) (Figure 6b), suggesting that they were expressing less anxiety-like behaviors and/or increased exploratory behaviors. There were no significant differences between groups in females (Figure 6a).

FIGURE 6.

Open field. (a) After inhibiting nucleus accumbens (NAc) pruning during adolescence, females show no statistically significant change in time spent in the inner quadrant of the open field apparatus (VEH n = 13; neutrophil inhibitory factor [NIF] n = 14). (b) In males, there is a statistically significant increase in the amount of time spent in the inner quadrant of the open field apparatus (VEH n = 17; NIF n = 16). Bar graphs represent average ± standard error of the mean. Student’s two-tailed t-test. If *, then p < .05. (c and d) Correlations between time spent in the inner zone of the open field apparatus and other social metrics in females and males. (c) In NIF-treated females, there is a significant correlation between nonsocial attentions in the novel interaction test and open field behavior (p = .0353), and in VEH-treated females, open field behavior significantly correlates with %social exploration in the social versus object choice test (p = .0104). Both these differences were found not significant following Fisher’s r-to-z transformation (NS). (d) In VEH-treated males, open field behavior correlates to %social exploration in the social versus object choice test (p = .0385). After Fisher’s r-to-z transformation, the p-value was significant (p = .0143). *p < .05, **p ≤ .01.

To determine whether a change in anxiety-like/exploratory behavior would be contributing to the social differences we observed, we calculated the correlations between time spent in the inner chamber of the OF apparatus with all other social metrics. In NIF-treated females, there is a significant correlation between nonsocial attention in the novel interaction test and OF behavior (p = .0353), and in VEH-treated females, OF behavior significantly correlates with %social exploration in the SVO test (p = .0104). However, these associations were not significantly different following Pearson’s-r-to-z transformation (Figure 6c, Table S1A). In VEH-treated males, OF behavior correlates to %social exploration in the SVO test (p = .0385) and was found significantly dysregulated following Pearson’s-r-to-z transformation (p = .0143) (Figure 6d, Table S1B). Overall, we neither observed a decrease of anxiety-like behavior/increase of exploratory behavior in NIF-treated females, nor an association between anxiety-like/exploratory behavior and social behavior in NIF-treated females. In males, although we do observe a decrease of anxiety-like behavior/increase of exploratory behavior, this is not found to be correlated with the social differences in NIF-treated males.

4 |. DISCUSSION

Our hypothesis was that inhibiting NAc pruning during sex-specific adolescent periods would increase sociability in sex-specific ways. Our data indicates that a temporally specific manipulation of microglial signaling in the developing NAc will have persistent effects on social behavior. We found that sociability was increased toward familiar, and not novel, conspecifics. In males, inhibiting NAc pruning with a CR3 antagonist increased familiar exploration in the SNP test, increased passive social behavior in the novel interaction test, and increased nonsocial contact at the expense of nonsocial attention in the familiar interaction test. In females, inhibiting NAc pruning did not change SNP behavior but increased active social interaction at the expense of nonsocial contact in the familiar interaction test. This leads us to infer that naturally occurring pruning serves to reduce social behaviors primarily directed toward a familiar conspecific in both sexes, but in sex-specific ways.

4.1 |. Adolescent social development shapes adult behavior

Adolescence is a period characterized by increased risk-taking behavior, heightened novelty seeking, and significant social maturation (Blankenstein et al., 2020; Bukowski & Adams, 2005; Spear, 2000; Sturman & Moghaddam, 2012). These behaviors likely facilitate “leaving the nest,” that is, the maturation of the dependent child to independent adult. We anticipated broad effects on sociality in both sexes, indiscriminate of the social partner, as social behavior with a novel partner was significantly changed during adolescence (Kopec et al., 2018). What we found, however, is that most social changes induced by inhibiting NAc pruning during adolescence were present when a familiar conspecific was incorporated into the social test, and very little change in response to a novel social stimulus. This may suggest that adolescent NAc pruning is less important for the natural increase in peer-centered social behaviors that emerge during adolescence, and more important for reducing familiarity-associated social behaviors. If true, this would also suggest different neural mechanisms guiding familiarity- versus novelty-directed social development, which to our knowledge is a new concept. Our data suggest that it may be important to incorporate familiar stimuli into social tests for more comprehensive assessments of sociability. Another possibility considers that the implications of increased rewarding social play during adolescence (Douglas et al., 2004; van den Berg et al., 1999), which we previously published was an acute consequence of inhibiting NAc pruning in both sexes. Social enrichment over adolescence is crucial for “normal” development (Burleson et al., 2016; van den Berg et al., 1999), and adolescent social isolation stress confers risk toward maladaptive behaviors, including anxiety-like (Huang et al., 2017; Lukkes et al., 2009; Weintraub et al., 2010), depression-like (Bukowski & Adams, 2005), and addiction-like behaviors (Deutschmann et al., 2022; Surakka et al., 2021). Interestingly, rats deprived of social play during adolescence have heightened anxiety-like behavior (Parvopassu et al., 2021). Our data complement this finding, as males that had inhibited NAc pruning during adolescence have a lowered anxiety-like phenotype (Figure 6b). Whether increased social play would strengthen the social relationship between the familiar cage mates, and the consequences of such a bond, remain to be tested.

4.2 |. Microglial pruning may be a linchpin in healthy and abnormal social development

Neurodevelopmental plasticity is tightly regulated, temporally bound, and can be sex-specific based on the brain region examined (Hanamsagar et al., 2017; Schwarz et al., 2012; Weinhard, Neniskyte, et al., 2018). Microglia, the innate immune cells of the brain, mediates the synaptic pruning process by phagocytosing synaptic proteins (Cangalaya et al., 2020; Weinhard, di Bartolomei, et al., 2018), among larger neural structures (Kurematsu et al., 2022). The complement system is a critical component of peripheral immunity and has more recently been accepted as a driver of development and plasticity (Mastellos, 2014; Presumey et al., 2017), specifically in activity-dependent pruning (Gyorffy et al., 2018; Lieberman et al., 2019; Schafer et al., 2012; Thion & Garel, 2018). Data are now accumulating that microglial pruning plays a role in social development via the regulation of neural development in several different brain regions (Kato et al., 2012). Sex differences in microglial pruning can be induced by the prenatal androgen surge (Lenz et al., 2013) and serve to differentiate mature social behaviors based on gonadal sex in the medial preoptic area and amygdala (VanRyzin et al., 2019, 2020). During adolescence, the synaptic landscape of the NAc undergoes a period of neuroimmune plasticity (Matthews et al., 2013; Schramm et al., 2002) coinciding with a peak and decline of social play (Manduca et al., 2016). Interfering with C3 receptor function on microglia appears to increase the length of time of the peak of social play (Kopec et al., 2018). Our data suggest that although the short-term consequence of NAc pruning at sex-specific times shows a convergent behavioral phenotype (increased play), the long-term programming of the social brain becomes sex-specifically refined. Moreover, there is evidence that the neurochemical systems being regulated by pruning in the NAc are sex-specific: dopamine signaling (via dopamine D1 receptor pruning) in males and an unknown, non-D1r system in females. The NAc is a heavily innervated region (Bayassi-Jakowicka et al., 2021), and thus, the downstream consequences of differential synaptic modulation between the sexes are likely to have wide-reaching effects (Louilot et al., 1986; Stark et al., 2023). The biological and behavioral importance of pruning different neurochemical systems in each sex to regulate similar, but not entirely overlapping social behaviors in adulthood, is unclear at this time. For example, microglia-mediated presynaptic excitatory pruning in the prefrontal cortex during adolescence, after the adolescent NAc pruning timepoint, also impacts later-life social behaviors (Andrews et al., 2021; Cressman et al., 2010). There may also be a role for microglia-mediated synaptic pruning in the hippocampus during the juvenile period for social development, but the evidence was collected with a global transgenic mouse with microglial deficiencies, and thus, it is difficult to make conclusive statements (Zhan et al., 2014). Finally, although these reports serve as evidence that microglial pruning is important for natural social development, there are also reports suggesting that neurodevelopmental disorders that present with social behavior deficits also have significant dysregulation in microglial pruning, these include, but are not limited to, autism-spectrum disorder (Arcuri et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2017; Ma et al., 2020; Zhan et al., 2014) and schizophrenia (Boksa, 2012; Howes & McCutcheon, 2017; Jones et al., 2020; Presumey et al., 2017). Critically, dysregulated synaptic pruning during adolescence plays a role in the development of psychotic disorders (Germann et al., 2021). Schizophrenia, in particular, with the onset of psychotic episodes and other hallmarks of the disorder strongly linked to microglial overactivation (Rodrigues-Neves et al., 2022; Sellgren et al., 2019) and complement system signaling (Wang et al., 2019; Westacott & Wilkinson, 2022). Taken together, these findings suggest that interfering with complement-mediated microglial pruning might delay symptoms and the onset of schizophrenia. Furthermore, studies in mouse models of autism, which show deficit in both pruning and social behavior, report a sensitive period in the NAc for effective treatment of social deficit (Matthiesen et al., 2023). These data suggest that understanding the healthy and abnormal regulation of temporally bound C3-mediated pruning at the synaptic level may be important to understand complex neurodevelopmental disorders.

4.3 |. Future directions and limitations

A limitation of this study is the inability to include direct comparisons of sex, as the timing of NIF manipulations was sex-specific. Future studies may focus on better understanding sex differences in the consequences of NAc pruning in a more direct way, for both social and nonsocial behaviors. Moreover, our previous work would suggest that the social consequences of inhibiting pruning in the NAc would be D1rdependent for males, but not females. Whether altered D1r signaling in the NAc can account for all the male changes will be important to determine in future studies. Future studies may include an investigation of the molecular landscape of the adult NAc after pruning to determine long-term effects of pruning on local and global signaling in the NAc.

Another possible limitation of our study is that although NIF was infused specifically in the NAc, we could not control if NIF diffused to neighboring areas. Thus, the changes in social behavior we found could result from a combined effect of NIF on NAc and neighboring areas associated with social processes (e.g., amygdala, hypothalamus) (Ferrara & Opendak, 2023; Gomez-Gomez et al., 2019; Hu et al., 2021; Lischinsky et al., 2023). Additionally, the vast connectivity of the NAc may have produced downstream effects on brain regions innervated by the NAc, and further studies will be necessary to address this possibility.

In conclusion, the data presented in this report indicate that interfering with a microglia-mediated developmental process within a single brain region during adolescence is sufficient to alter social developmental trajectories in sex-specific ways.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R01DA052889 and R03AG07011 to AMK and Albany Medical College Start-up funds to AMK.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.This article was prepared while Ashley Kopec was employed at Albany Medical College. The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, or the US government.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Al Omran AJ, Shao AS, Watanabe S, Zhang Z, Zhang J, Xue C, Watanabe J, Davies DL, Shao XM, & Liang J (2022). Social isolation induces neuroinflammation and microglia overactivation, while dihydromyricetin prevents and improves them. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 19(1), 2. 10.1186/s12974-021-02368-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almquist YB, Landstedt E, Jackisch J, Rajaleid K, Westerlund H, & Hammarstrom A (2018). Prevailing over adversity: Factors counter-acting the long-term negative health influences of social and material disadvantages in youth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(9), 1842. 10.3390/ijerph15091842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Rutstein M, Benzo JM, Hostetter JC, & Teicher MH (1997). Sex differences in dopamine receptor overproduction and elimination. Neuroreport, 8(6), 1495–1497. https://journals.lww.com/neuroreport/fulltext/1997/04140/sex_differences_in_dopamine_receptor.34.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JL, Ahmed SP, & Blakemore SJ (2021). Navigating the social environment in adolescence: The role of social brain development. Biological Psychiatry, 89(2), 109–118. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcuri C, Mecca C, Bianchi R, Giambanco I, & Donato R (2017). The pathophysiological role of microglia in dynamic surveillance, phagocytosis and structural remodeling of the developing CNS. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 10, 191. 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayassi-Jakowicka M, Lietzau G, Czuba E, Steliga A, Waśkow M, & Kowiański P (2021). Neuroplasticity and multilevel system of connections determine the integrative role of nucleus accumbens in the brain reward system. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(18), 9806. 10.3390/ijms22189806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, & Shambaugh KL (2021). Comparative assessment of familiarity/novelty preferences in rodents [Original Research]. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, 648830. 10.3389/fnbeh.2021.648830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendersky CJ, Milian AA, Andrus MD, De La Torre U, & Walker DM (2021). Long-term impacts of post-weaning social isolation on nucleus accumbens function. Front Psychiatry, 12, 745406. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.745406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenstein NE, Telzer EH, Do KT, van Duijvenvoorde ACK, & Crone EA (2020). Behavioral and neural pathways supporting the development of prosocial and risk-taking behavior across adolescence. Child Development, 91(3), e665–e681. 10.1111/cdev.13292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert RA, Martin LM, Grosek M, & Clarie AJ (2008). Effectiveness of a peer-support community in addiction recovery: Participation as intervention. Occupational Therapy International, 15(4), 205–220. 10.1002/oti.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boksa P (2012). Abnormal synaptic pruning in schizophrenia: Urban myth or reality? Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 37(2), 75–77. 10.1503/jpn.120007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenhouse HC, & Schwarz JM (2016). Immunoadolescence: Neuroimmune development and adolescent behavior. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 70, 288–299. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM, & Adams R (2005). Peer relationships and psychopathology: Markers, moderators, mediators, mechanisms, and meanings. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34(1), 3–10. 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke AR, McCormick CM, Pellis SM, & Lukkes JL (2017). Impact of adolescent social experiences on behavior and neural circuits implicated in mental illnesses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 76(Pt B), 280–300. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burleson CA, Pedersen RW, Seddighi S, DeBusk LE, Burghardt GM, & Cooper MA (2016). Social play in juvenile hamsters alters dendritic morphology in the medial prefrontal cortex and attenuates effects of social stress in adulthood. Behavioral Neuroscience, 130(4), 437–447. 10.1037/bne0000148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JL, Eagleson KL, Fox NA, Hensch TK, & Levitt P (2017). Social origins of developmental risk for mental and physical illness. Journal of Neuroscience, 37(45), 10783–10791. 10.1523/jneurosci.1822-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cangalaya C, Stoyanov S, Fischer KD, & Dityatev A (2020). Light-induced engagement of microglia to focally remodel synapses in the adult brain. Elife, 9, e58435. 10.7554/eLife.58435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli SA, & Caruso MJ (2015). Sex, social status and physiological stress in primates: The importance of social and glucocorticoid dynamics. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140103. 10.1098/rstb.2014.0103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cressman VL, Balaban J, Steinfeld S, Shemyakin A, Graham P, Parisot N, Moore H (2010). Prefrontal cortical inputs to the basal amygdala undergo pruning during late adolescence in the rat. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 518(14), 2693–2709. 10.1002/cne.22359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins EM (2020). Social hallmarks of aging: Suggestions for geroscience research. Ageing Research Reviews, 63, 101136. 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Franca Malheiros MAS, Castelo-Branco R, de Medeiros PHS, de Lima Marinho PE, da Silva Rodrigues Meurer Y, & Barbosa FF (2020). Conspecific presence improves episodic-like memory in rats. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 14, 572150. 10.3389/fnbeh.2020.572150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutschmann AU, Kirkland JM, & Briand LA (2022). Adolescent social isolation induced alterations in nucleus accumbens glutamate signalling. Addiction Biology, 27(1), e13077. 10.1111/adb.13077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas LA, Varlinskaya EI, & Spear LP (2004). Rewarding properties of social interactions in adolescent and adult male and female rats: Impact of social versus isolate housing of subjects and partners. Developmental Psychobiology, 45(3), 153–162. 10.1002/dev.20025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falco AM, McDonald CG, Bachus SE, & Smith RF (2014). Developmental alterations in locomotor and anxiety-like behavior as a function of D1 and D2 mRNA expression. Behavioural Brain Research, 260, 25–33. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara NC, & Opendak M (2023). Amygdala circuit transitions supporting developmentally-appropriate social behavior. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 201, 107762. 10.1016/j.nlm.2023.107762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey AL, Frank MJ, & McCabe C (2021). Social reinforcement learning as a predictor of real-life experiences in individuals with high and low depressive symptomatology. Psychological Medicine, 51(3), 408–415. 10.1017/s0033291719003222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germann M, Brederoo SG, & Sommer IEC (2021). Abnormal synaptic pruning during adolescence underlying the development of psychotic disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(3), 222–227. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gomez YM, Sanchez-Aparicio P, Mejia-Chavez S, Garcia-Garcia F, Pascual-Mathey LI, Aguilera-Reyes U, Galicia O, & Venebra-Munoz A (2019). c-Fos immunoreactivity in the hypothalamus and reward system of young rats after social novelty exposure. Neuroreport, 30(7), 510–515. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabert K, Michoel T, Karavolos MH, Clohisey S, Baillie JK, Stevens MP, Freeman TC, Summers KM, & McColl BW (2016). Microglial brain region-dependent diversity and selective regional sensitivities to aging. Nature Neuroscience, 19(3), 504–516. 10.1038/nn.4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A, Murray SH, Eltahir A, Patel S, Hansson AC, Spanagel R, & McCormick CM (2023). Acute and long-term sex-dependent effects of social instability stress on anxiety-like and social behaviours in Wistar rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 438, 114180. 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyorffy BA, Kun J, Torok G, Bulyaki E, Borhegyi Z, Gulyassy P, Kis V, Szocsics P, Micsonai A, Matko J, Drahos L, Juhasz G, Kekesi KA, & Kardos J (2018). Local apoptotic-like mechanisms underlie complement-mediated synaptic pruning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(24), 6303–6308. 10.1073/pnas.1722613115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbout B, Marshall AT, Azimi A, Liljeholm M, Mahler SV, Wassum KM, & Ostlund SB (2019). Mesolimbic dopamine projections mediate cue-motivated reward seeking but not reward retrieval in rats. Elife, 8, e43551. 10.7554/eLife.43551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Fan Y, Zhou K, Blomgren K, & Harris RA (2021). Uncovering sex differences of rodent microglia. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 18(1), 74. 10.1186/s12974-021-02124-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanamsagar R, Alter MD, Block CS, Sullivan H, Bolton JL, & Bilbo SD (2017). Generation of a microglial developmental index in mice and in humans reveals a sex difference in maturation and immune reactivity. Glia, 65(9), 1504–1520. 10.1002/glia.23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslam C, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Cruwys T, & Steffens NK (2021). Life change, social identity, and health. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 635–661. 10.1146/annurev-psych-060120-111721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges TE, Baumbach JL, Marcolin ML, Bredewold R, Veenema AH, & McCormick CM (2017). Social instability stress in adolescent male rats reduces social interaction and social recognition performance and increases oxytocin receptor binding. Neuroscience, 359, 172–182. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes OD, & McCutcheon R (2017). Inflammation and the neural diathesis-stress hypothesis of schizophrenia: A reconceptualization. Translational Psychiatry, 7(2), e1024. 10.1038/tp.2016.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu RK, Zuo Y, Ly T, Wang J, Meera P, Wu YE, & Hong W (2021). An amygdala-to-hypothalamus circuit for social reward. Nature Neuroscience, 24(6), 831–842. 10.1038/s41593-021-008282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q, Zhou Y, & Liu LY (2017). Effect of post-weaning isolation on anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors of C57BL/6J mice. Experimental Brain Research, 235(9), 2893–2899. 10.1007/s00221-017-5021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppe-Gourgues F, & O’Donnell P (2012). Periadolescent changes of D(2)—AMPA interactions in the rat nucleus accumbens. Synapse, 66(1), 1–8. 10.1002/syn.20976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MC, Koh JM, & Cheong KH (2020). Synaptic pruning in schizophrenia: Does minocycline modulate psychosocial brain development? BioEssays, 42(9), e2000046. 10.1002/bies.202000046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juraska JM, & Drzewiecki CM (2020). Cortical reorganization during adolescence: What the rat can tell us about the cellular basis. DevelopmentalCognitiveNeuroscience,45,100857. 10.1016/j.dcn.2020.100857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang DH, Coe CL, Karaszewski J, & McCarthy DO (1998). Relationship of social support to stress responses and immune function in healthy and asthmatic adolescents. Research in Nursing & Health, 21(2), 117–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato TA, Watabe M, Tsuboi S, Ishikawa K, Hashiya K, Monji A, Utsumi H, & Kanba S (2012). Minocycline modulates human social decision-making: Possible impact of microglia on personality-oriented social behaviors. PLoS ONE, 7(7), e40461. 10.1371/journal.pone.0040461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Cho MH, Shim WH, Kim JK, Jeon EY, Kim DH, & Yoon SY (2017). Deficient autophagy in microglia impairs synaptic pruning and causes social behavioral defects. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(11), 1576–1584. 10.1038/mp.2016.103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopec AM, Smith CJ, Ayre NR, Sweat SC, & Bilbo SD (2018). Microglial dopamine receptor elimination defines sex-specific nucleus accumbens development and social behavior in adolescent rats. Nature Communications, 9(1), 3769. 10.1038/s41467-018-06118-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter AK, Guest PC, & Sarnyai Z (2019a). Free dyadic social interaction test in mice. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1916, 93–97. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraeuter AK, Guest PC, & Sarnyai Z (2019b). The open field test for measuring locomotor activity and anxiety-like behavior. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1916, 99–103. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8994-2_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurematsu C, Sawada M, Ohmuraya M, Tanaka M, Kuboyama K, Ogino T, Matsumoto M, Oishi H, Inada H, Ishido Y, Sakakibara Y, Nguyen HB, Thai TQ, Kohsaka S, Ohno N, Yamada MK, Asai M, Sokabe M, Nabekura J, ... Sawamoto K (2022). Synaptic pruning of murine adult-born neurons by microglia depends on phosphatidylserine. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 219(4), e20202304 10.1084/jem.20202304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc H, & Ramirez S (2020). Linking social cognition to learning and memory. Journal of Neuroscience, 40(46), 8782–8798. 10.1523/jneurosci.1280-20.2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemos C, Salti A, Amaral IM, Fontebasso V, Singewald N, Dechant G, Hofer A, & El Rawas R (2021). Social interaction reward in rats has anti-stress effects. Addiction Biology, 26(1), e12878. 10.1111/adb.12878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenz KM, Nugent BM, Haliyur R, & McCarthy MM (2013). Microglia are essential to masculinization of brain and behavior. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(7), 2761–2772. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1268-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SW, Williams ZM, & Báez-Mendoza R (2021). Investigating the neurobiology of abnormal social behaviors. Front Neural Circuits, 15, 769314. 10.3389/fncir.2021.769314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman OJ, McGuirt AF, Tang G, & Sulzer D (2019). Roles for neuronal and glial autophagy in synaptic pruning during development. Neurobiology of Disease, 122, 49–63. 10.1016/j.nbd.2018.04.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischinsky JE, Yin L, Shi C, Prakash N, Burke J, Shekaran G, Grba M, Corbin JG, & Lin D (2023). Transcriptionally defined amygdala subpopulations play distinct roles in innate social behaviors. Nature Neuroscience, 26(12), 2131–2146. 10.1038/s41593-023-01475-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louilot A, Le Moal M, & Simon H (1986). Differential reactivity of dopaminergic neurons in the nucleus accumbens in response to different behavioral situations. An in vivo voltammetric study in free moving rats. Brain Research, 397(2), 395–400. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90646-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukkes JL, Mokin MV, Scholl JL, & Forster GL (2009). Adult rats exposed to early-life social isolation exhibit increased anxiety and conditioned fear behavior, and altered hormonal stress responses. Hormones and Behavior, 55(1), 248–256. 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Chen K, Cui Y, Huang G, Nehme A, Zhang L, Li H, Wei J, Liong K, Liu Q, Shi L, Wu J, & Qiu S (2020). Depletion of microglia in developing cortical circuits reveals its critical role in glutamatergic synapse development, functional connectivity, and critical period plasticity. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 98(10), 1968–1986. 10.1002/jnr.24641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manduca A, Servadio M, Damsteegt R, Campolongo P, Vanderschuren LJ, & Trezza V (2016). Dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens modulates social play behavior in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(9), 2215–2223. 10.1038/npp.2016.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martz ME, Hardee JE, Cope LM, McCurry KL, Soules M, Zucker RA, & Heitzeg MM (2022). Nucleus accumbens response to reward among children with a family history of alcohol use problems: Convergent findings from the ABCD study(®) and Michigan longitudinal study. Brain Sciences, 12(7), 913. 10.3390/brainsci12070913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastellos DC (2014). Complement emerges as a masterful regulator of CNS homeostasis, neural synaptic plasticity and cognitive function. Experimental Neurology, 261, 469–474. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews M, Bondi C, Torres G, & Moghaddam B (2013). Reduced presynaptic dopamine activity in adolescent dorsal striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology, 38(7), 1344–1351. 10.1038/npp.2013.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthiesen M, Khlaifia A, Steininger CFD Jr., Dadabhoy M, Mumtaz U, & Arruda-Carvalho M (2023). Maturation of nucleus accumbens synaptic transmission signals a critical period for the rescue of social deficits in a mouse model of autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Brain, 16(1), 46. 10.1186/s13041-023-01028-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeal N, Scotti MA, Wardwell J, Chandler DL, Bates SL, Larocca M, Trahanas DM, & Grippo AJ (2014). Disruption of social bonds induces behavioral and physiological dysregulation in male and female prairie voles. Autonomic Neuroscience, 180, 9–16. 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchowski PJ, Zhang L, Chang ER, Soule HR, Plow EF, & Moyle M (1994). Functional interaction between the integrin antagonist neutrophil inhibitory factor and the I domain of CD11b/CD18. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 269(42), 26419–26423. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7929363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LH, Peketi P, & Lenz KM (2021). Microglia regulate cell genesis in a sex-dependent manner in the neonatal hippocampus. Neuroscience, 453, 237–255. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda T, Osako Y, Hidaka C, Nishihara M, Young LJ, Mitsui S, & Yuri K (2022). Separation from a bonded partner alters neural response to inflammatory pain in monogamous rodents. Behavioural Brain Research, 418, 113650. 10.1016/j.bbr.2021.113650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orihuel J, Capellán R, Roura-Martínez D, Ucha M, Ambrosio E, & Higuera-Matas A (2021). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol during adolescence reprograms the nucleus accumbens transcriptome, affecting reward processing, impulsivity, and specific aspects of cocaine addiction-like behavior in a sex-dependent manner. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology, 24(11), 920–933. 10.1093/ijnp/pyab058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvopassu A, Oggiano M, Festucci F, Curcio G, Alleva E, & Adriani W (2021). Altering the development of the dopaminergic system through social play in rats: Implications for anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, and compulsivity. Neuroscience Letters, 760, 136090. 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presumey J, Bialas AR, & Carroll MC (2017). Complement system in neural synapse elimination in development and disease. Advances in Immunology, 135, 53–79. 10.1016/bs.ai.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prilutsky D, Kho AT, Feiglin A, Hammond T, Stevens B, & Kohane IS (2017). Sexual dimorphism of complement-dependent microglial synaptic pruning and other immune pathways in the developing brain. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). Published online October 17. 10.1101/204412 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues-Neves AC, Ambrosio AF, & Gomes CA (2022). Microglia sequelae: Brain signature of innate immunity in schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry, 12(1), 493. 10.1038/s41398-022-02197-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, Ransohoff RM, Greenberg ME, Barres BA, & Stevens B (2012). Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron, 74(4), 691–705. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavi S, Manduca A, Carbone E, Buzzelli V, & Trezza V (2022). Assessing Dyadic Social Interactions in Rodent Models of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. In Martin S & Laumonnier F (Eds.), Translational Research Methods in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Neuromethods (vol. 185). Humana, New York, NY. 10.1007/978-1-07162569-9_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider P, Bindila L, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Lutz B, Spanagel R, & Schneider M (2016). Adverse social experiences in adolescent rats result in enduring effects on social competence, pain sensitivity and endocannabinoid signaling [Original Research]. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 10, 203. 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm NL, Egli RE, & Winder DG (2002). LTP in the mouse nucleus accumbens is developmentally regulated. Synapse, 45(4), 213–219. 10.1002/syn.10104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz ,JM, Sholar ,PW, Bilbo ,SD (2012). Sex differences in microglial colonization of the developing rat brain. Journal of Neurochemistry, 120(6), 948–963. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07630.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweinfurth MK (2020). The social life of Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus). Elife, 9, e54020. 10.7554/eLife.54020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellgren CM, Gracias J, Watmuff B, Biag JD, Thanos JM, Whittredge PB, Fu T, Worringer K, Brown HE, Wang J, Kaykas A, Karmacharya R, Goold CP, Sheridan SD, & Perlis RH (2019). Increased synapse elimination by microglia in schizophrenia patient-derived models of synaptic pruning. Nature Neuroscience, 22(3), 374–385. 10.1038/s41593-018-0334-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siracusa ER, Higham JP, Snyder-Mackler N, & Brent LJN (2022). Social ageing: Exploring the drivers of late-life changes in social behaviour in mammals. Biology Letters, 18(3), 20210643. 10.1098/rsbl.2021.0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov A, Daily KP, Gray MC, Ragland SA, Werner LM, Johnson MB, Eby JC, Hewlett EL, Taylor RP, & Criss AK (2023). Phagocytosis via complement receptor 3 enables microbes to evade killing by neutrophils. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 10.1093/jleuko/qiad028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Wilkins KB, Mogavero JN, & Veenema AH (2015). Social novelty investigation in the juvenile rat: Modulation by the μ-opioid system. Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 27(10), 752–764. 10.1111/jne.12301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJW, Wilkins KB, Li S, Tulimieri MT, & Veenema AH (2018). Nucleus accumbens mu opioid receptors regulate context-specific social preferences in the juvenile rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 89, 59–68. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soteros BM, & Sia GM (2022). Complement and microglia dependent synapse elimination in brain development. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease, 14(3), e1545. 10.1002/wsbm.1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP (2000). The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 24(4), 417–463. 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark RA, Brinkman B, Gibb RL, Iwaniuk AN, & Pellis SM (2023). Atypical play experiences in the juvenile period has an impact on the development of the medial prefrontal cortex in both male and female rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 439, 114222. 10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturman DA, & Moghaddam B (2012). Striatum processes reward differently in adolescents versus adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(5), 1719–1724. 10.1073/pnas.1114137109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surakka A, Vengeliene V, Skorodumov I, Meinhardt M, Hansson AC, & Spanagel R (2021). Adverse social experiences in adolescent rats result in persistent sex-dependent effects on alcohol-seeking behavior. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 45(7), 1468–1478. 10.1111/acer.14640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thion MS, & Garel S (2018). Microglia under the spotlight: Activity and complement-dependent engulfment of synapses. Trends in Neuroscience (Tins), 41(6), 332–334. 10.1016/j.tins.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg CL, Hol T, Van Ree JM, Spruijt BM, Everts H, & Koolhaas JM (1999). Play is indispensable for an adequate development of coping with social challenges in the rat. Developmental Psychobiology, 34(2), 129–138. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10086231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRyzin JW, Marquardt AE, Argue KJ, Vecchiarelli HA, Ashton SE, Arambula SE, Hill MN, & McCarthy MM (2019). Microglial phagocytosis of newborn cells is induced by endocannabinoids and sculpts sex differences in juvenile rat social play. Neuron, 102(2), 435–449.e6. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanRyzin JW, Marquardt AE, Pickett LA, & McCarthy MM (2020). Microglia and sexual differentiation of the developing brain: A focus on extrinsic factors. Glia, 68(6), 1100–1113. 10.1002/glia.23740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlinskaya EI, & Spear LP (2008). Social interactions in adolescent and adult Sprague-Dawley rats: Impact of social deprivation and test context familiarity. Behavioural Brain Research, 188(2), 398–405. 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.11.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venniro M, Zhang M, Caprioli D, Hoots JK, Golden SA, Heins C, Morales M, Epstein DH, & Shaham Y (2018). Volitional social interaction prevents drug addiction in rat models. Nature Neuroscience, 21(11), 1520–1529. 10.1038/s41593-018-0246-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Frijtag JC, Schot M, van den Bos R, & Spruijt BM (2002). Individual housing during the play period results in changed responses to and consequences of a psychosocial stress situation in rats. Developmental Psychobiology, 41(1), 58–69. 10.1002/dev.10057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Zhang L, & Gage FH (2019). Microglia, complement and schizophrenia. Nature Neuroscience, 22(3), 333–334. 10.1038/s41593-019-0343-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhard L, di Bartolomei G, Bolasco G, Machado P, Schieber NL, Neniskyte U, Exiga M, Vadisiute A, Raggioli A, Schertel A, Schwab Y, & Gross CT (2018). Microglia remodel synapses by presynaptic trogocytosis and spine head filopodia induction. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1228. 10.1038/s41467-018-03566-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhard L, Neniskyte U, Vadisiute A, di Bartolomei G, Aygün N, Riviere L, Zonfrillo F, Dymecki S, & Gross C (2018). Sexual dimorphism of microglia and synapses during mouse postnatal development. Developmental Neurobiology, 78(6), 618–626. 10.1002/dneu.22568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub A, Singaravelu J, & Bhatnagar S (2010). Enduring and sex-specific effects of adolescent social isolation in rats on adult stress reactivity. Brain Research, 1343, 83–92. 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westacott LJ, & Wilkinson LS (2022). Complement dependent synaptic reorganisation during critical periods of brain development and risk for psychiatric disorder. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 16, 840266. 10.3389/fnins.2022.840266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wöhr M, & Scattoni ML (2013). Behavioural methods used in rodent models of autism spectrum disorders: Current standards and new developments. Behavioural Brain Research, 251, 5–17. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, & Harris KM (2016). Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(3), 578–583. 10.1073/pnas.1511085112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Y, Paolicelli RC, Sforazzini F, Weinhard L, Bolasco G, Pagani F, Vyssotski AL, Bifone A, Gozzi A, Ragozzino D, & Gross CT (2014). Deficient neuron-microglia signaling results in impaired functional brain connectivity and social behavior. Nature Neuroscience, 17(3), 400–406. 10.1038/nn.3641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.