Abstract

Bone tissue substitutes are increasing in importance. Hydroxyapatite (HA) and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) act as a cell matrix and improve its mechanical properties. One of their raw materials is marine-origin by-products. Objectives: To synthesize, characterize, and evaluate the cellular cytotoxicity of a 3D biomaterial based on HA and β-TCP from mussel shells. Methods: We prepared pellets with 150, 200, and 250 mg and evaluated them through sintering, XRD, FTIR, ICP-OES, Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM), and immunocytochemical tests. The Alamar Blue method was applied to the Balb-T3T cell line within 72 h to evaluate cytotoxicity. Results: Our biomaterials presented a smooth surface with slight irregularity and porosities presenting different diameters and morphologies and showed chemical, morphological, and ultrastructural similarity to bone hydroxyapatite, mainly the 150 and 200 mg pellets. Significance: We produced promising HA/β-TCP bioceramics with characteristics that allowed cell culture, promoting adhesion, spreading, and proliferation.

Keywords: Biomaterial, Scaffold, hydroxyapatite, β-tricalcium phosphate, Mussel shells, Sustainability

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Hydroxyapatite was synthesized in a simple and sustainable way from mussel shell powder.

-

•

The material was sintered in the form of tablets to facilitate the application of the cells.

-

•

HA and β-TCP with 150 and 200 mg promoted proliferation and adhesion of the cells.

-

•

This biomaterial showed characteristics of similarity to bone hydroxyapatite.

1. Introduction

Tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary field that aims to develop biological substitutes that restore, maintain, and improve tissue function. Several materials have been developed in different fields, with emphasis on bone tissue substitutes. They aim to generate a biocompatible reconstruction that can mimic bone structure and function [1,2]. Regarding these prerequisites, one of the materials that have gained notoriety as a bone substitute is hydroxyapatite (HA - Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2). It is a biocompatible, osteoconductive, and bioactive bioceramic that can form direct interactions with living tissues. It has a low solubility at physiological pH and has been used to produce biomaterials in nanoparticles and nanocomposites in the development of bone tissue [[3], [4], [5], [6]].

Beta tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP — Ca3(PO4)2) also has biocompatibility, osteoconduction, and osteoinduction properties. The combination of hydroxyapatite with β-TCP produces a bimodal biomaterial. HA plays a fundamental role in cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation. It has slow absorption, maintaining the creation of space for the exchange of elements necessary to promote tissue repair. Moreover, β-TCP, which is more soluble, plays an important role regarding calcium and phosphorus ions, contributing to osteogenic activity [7,8].

Numerous methods have been developed for the synthesis of HA [[9], [10], [11], [12]], such as obtaining biomaterials from renewable sources using materials of calcareous origin, marine corals, fossilized calcareous shells, sea urchins, oyster shells, calcium sulfate (gypsum), eggshells, and bovine cortical bones. These are seen as raw material sources based on calcium phosphate powder. They are an alternative for developing new biomaterials with a sustainable process [5,[13], [14], [15]].

There is scarce literature on HA/β-TCP biomaterials from natural sources, such as marine shells [5,16]. These should have more notoriety as they offer financial and environmental advantages [5]. Furthermore, these biomaterials have crystallographic similarities with bone apatite, bioactivity, biocompatibility, and osteoconductivity. They also offer interconnected micro- and nanoporous, which increase the surface area of the granule and micropores, promoting osseointegration into the bone tissue. These characteristics are different from conventional microstructured biomaterials [5].

In these terms, this work aimed to synthesize and characterize 3D biomaterials based on Hydroxyapatite (HA), Calcium Beta Triphosphate (β-TCP), and subsequent evaluation of cellular cytotoxicity. A by-product of fishing (mussel shells), which aims to generate effective biomaterial with reduced cost and promote a framework that enables cell culture aiming at bone tissue regeneration.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis

We used mussel shells collected from fishermen's cooperatives in Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil, as the raw material for the hydroxyapatite-based biomaterial. The shells were washed and went through a wet milling process using a 50 % solids dispersion in distilled water, which was added to a mill with alumina spheres and remained in milling for 3 h. Subsequently, the dispersion was heated at 80 °C for 24 h, and after drying, it was ground in a mortar and pestle, then sieved in a 100 μm mesh.

The methodology of [17] was followed for synthesizing the biomaterial. Initially, an analysis was performed by ICP-OES (Thermo Scientific—model iCAP 6500) to determine the calcium content in the raw material. From the value obtained (0.270 g of Ca/g of the sample), the stoichiometric amount for adding 1 mol L−1 HCl (Alphatec, 37 %) was determined according to equation (1).

The HCl solution was added to a beaker that remained under magnetic stirring while the ladle powder was slowly added, trying to avoid foaming due to the release of CO2. After completing the addition of the powder, the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h and filtered through qualitative filter paper. The filtered solution of calcium chloride was kept under stirring. At the same time, NaOH 2 mol L−1 (Êxodo, 97 %) was added until it reached a pH above 12 to obtain solid Ca(OH)2, according to the Ca(OH)2 species diagram [18] and equation (2).

| CaCO3 + 2 HCl –> CaCl2 + H2O + CO2 | (1) |

| CaCl2 + 2 NaOH –> Ca(OH)2 + 2 NaCl | (2) |

The dispersion was stirred for 1 h, centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min, and redispersed in 60 mL of distilled water to wash the material. It was centrifuged again and dried in an oven at 50 °C for 48 h.

After obtaining Ca(OH)2, the Ca content was analyzed again by ICP/OES to determine the amount of phosphoric acid to be added to obtain the hydroxyapatite (Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2) since the Ca/P ratio should be close to 1.667 [19,20]. Our analysis presented 0.566 g of Ca/g of the sample, which is very close to the expected value of 0.541 g of Ca/g, indicating a small amount of humidity and high purity of the sample). The Ca(OH)2 was dispersed in distilled water and stirred for 30 min before adding 1 mol L−1 H3PO4 (Vetec, 85 %) by drip, keeping the pH between 9 and 10 [21]. After completing the acid addition, the dispersion was stirred for 2 h; the material was centrifuged at 4000 rpm (centrifuge Sigma 3-16P, rotor 11133), redispersed in 60 mL of distilled water for washing, centrifuged again, and dried at 60 °C for 48 h in an oven (Vacuo Term-6030A).

The powdered material was pressed into 10 mm diameter pellets, with 150 mg, 200 mg, and 250 mg of material, using a press and applying 3 tons. The pellets were sintered at 1000 °C for 2 h in an oven operating under a vacuum, with a heating rate of 30 °C. After one night, the samples were removed from the muffle, resulting in the scaffold.

2.2. Characterization

The compounds obtained in the different synthesis steps were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Shimadzu XRD-6000 diffractometer with a CuKα = 1.5418 Å radiation and using a current of 30 mA and tension of 40 kV and dwell time of 2°min−1. Infrared vibrational spectroscopy was performed in FTIR mode, and the spectra were obtained using a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrophotometer operating in transmission mode. The analyses were performed with the sample in the form of pellets with approximately 1 % (w/w) of the sample added to KBr (Sigma-Aldrich, >99 % purity), and the mixture was macerated and pressed with 6 tons. The measurements were performed from 400 cm−1 to 4000 cm−1, using a resolution of 4 cm−1 and an accumulation of 32 scans. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) data were performed in a Tescan Vega 3 LMU microscope with AZ Tech software. The samples of sintered hydroxyapatite and pellets were deposited on copper tapes. After collecting the EDS spectra, the samples were sputtered with a thin gold layer to obtain the SEM images. The elements were quantified with a Thermo Scientific ICP-OES spectrometer (model iCAP 6500) with the Thermo Scientific iTeVa software version 1.2.0.30. The samples were dissolved in a solution containing HNO3 (Alphatec, 65 %) in Milli-Q water (1.0 % v/v), and the data were collected in duplicates. The calcium and phosphorus leaching test was performed with 150 mg, 200 mg, and 250 mg hydroxyapatite pellets. For each sample, three pellets were evaluated, one for each day (1–3 days). The pellets were placed in incubation plates with six wells and 5 ml ultrapure water. The plates were kept in an incubator at 37 °C and acclimatized with 5 % CO2. After the period had elapsed (1–3 days), the solutions were analyzed by ICP-OES.

2.3. In vitro model

BALB/3T3 clone 31 cell line (ATCC® CCL-163™) (murine fibroblasts) were plated on the 150, 200, and 250 mg scaffolds to evaluate the cell interaction with these bioceramics, the morphology, viability, cell proliferation, adhesion of this cell line. They were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 1 U/mL of penicillin, 1 μg/mL of streptomycin, and 10 % fetal bovine serum (all from Gibco ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). They were maintained in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2.

For the subculture, the cells were placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS-Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.25 % trypsin/EDTA for 3 min. DMEM and 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) were used to inactivate the trypsin. Then, centrifugation was performed, and the supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in DMEM with 10 % FBS. We counted cells through the De Neubauer chamber and seeded the cells under the biomaterials. The test used two different passages, each performed in triplicates with two passages.

The cells were plated on the respective bioceramics of 1.1 x 104 with 45 μL of the medium. Control cells were plated directly on 24-well cell culture plates (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) or circular coverslips, depending on the assay performed. We used the same cell density with the same volume of 45 μL. They were kept at 37 °C, 5 % CO2, for 30 min to allow cell fixation. Afterward, they were complemented with 1 ml of complete (DMEM) medium. A period of 72 h was standardized to perform the respective tests.

2.4. Evaluation of cell viability and proliferation - Alamar Blue assay

Alamar Blue (INVITROGEN-US). These were incubated for 72 h with 10 % (v/v) of the reagent. The cell culture reagents were from Gibco ThermoFisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA. Plastic materials used for cell culture were obtained from Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany. The data were obtained at wavelengths 570 and 590 nm using a spectrophotometer (INFINITE M200-TECAN) [22]. The results were analyzed in the GraphPadPrism program version 5.01 windows (San Diego, CA, USA), and the One-Way test was performed, ANOVA and Tukey, with a significance of 5 %.

The formula below was used to analyze the material's cytotoxicity percentage. This equation was also taken into consideration by other authors for the analysis of cytotoxicity in the analysis of different biomaterials (CURSARO et al., 2022 and ROHMADI et al., 2021) [23,24].

| (3) |

2.4.1. Morphological and ultrastructural analysis of cells in SEM

We performed triplicates for each scaffold (150, 200, and 250 mg) for morphological and ultrastructural analysis in SEM. The triplicates were carried out on a 13 mm circular coverslip (Kasvi) for the control. The cells were maintained for 72 h in a CO2 incubator. After the exposure time in cell culture, we fixed the cells with Karnovsky's solution (2 % glutaraldehyde, 4 % paraformaldehyde, and 1 mM CaCl2 in 0.1 mol L−1 cacodylate buffer) for 1 h. They were washed with 0.1 mol L−1 sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. Then, they underwent dehydration in increasing concentrations of ethanol 30 %, 50 %, 70 %, 90 %, and two times 100 %, critical point (CPD 010 Critical Point Dryer 030 - Balzers) and subsequently metalized with gold (SCD 030 - Balzers). The images were captured in the Scanning Electron Microscope (TESCAN VEGA 3 LMU) of the Electronic Microscopy Center of the Federal University of Paraná. Electron microscopy reagents were purchased from Electron Microscopy Sciences (EMS), Hatfield, Pennsylvania, USA.

2.4.2. Immunofluorescence of cells in Confocal Laser Microscopy

Triplicates were performed for each scaffold (150, 200, and 250 mg) within 72 h to detect actin microfilaments. For control cells, triplicates were performed on a 13 mm circular coverslip (Kasvi).

Fixation was performed with 2 % paraformaldehyde (Ladd Research Industries, Burlington, VT, USA- Electron Microscopy Sciences, USA) in PBS for 20 min, washed with PBS, and incubated with glycine (0.1 % in PBS) for 4 min (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). After washing with PBS and kept in PBS containing 0.01 % saponin (Sigma Aldrich) for 40 h. Then, we performed the actin microfilaments detection using ActinGreen ™ 488 (Invitrogen, USA) in a PBS solution and 0.01 % saponin for 40 min under agitation. Subsequently, these were washed with PBS, and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Invitrogen, USA) 3 μM in PBS (Molecular Probes, USA) was used for 20 min to detect the cell nucleus. At the end of the incubation, washing with PBS was performed twice. Control cells were mounted on a slide (Kasvi) using Fluormont G™ (Sigma), sealed, and kept in a refrigerator at four °C degrees. For the scaffolds (150, 200, and 250 mg) containing the cells, they were maintained in PBS at four °C degrees in the absence of light until analysis in the inverted Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 Confocal Microscope (Bio-Rad Hercules, Richmond, CA, USA). A 35 × 10 mm Petri dish with a glass bottom (Greiner) was used for these biomaterials analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of hydroxyapatite and calcium β triphosphate

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) indicated the formation of Ca(OH)2 in the first stages of processing the raw material shell powder. The X-ray diffraction patterns of the sample (Fig. 1A–a) showed intense and well-defined peaks and a pattern of signals that are consistent with the crystallographic record of Ca(OH)2 (JCPDS 04–0733). In addition to the diffraction peaks attributed to Ca(OH)2, small diffraction peaks could also be attributed to slight contamination of CaCO3 by contact with atmospheric air (JCPDS 85–1108).

Fig. 1.

(A) X-ray diffraction pattern of (a) Ca(OH)2 and (b) after the reaction of Ca(OH)2 with H3PO4. (B) X-ray diffraction pattern of hydroxyapatite obtained after calcination at 1000 °C. (C) FTIR spectra of (a) Ca(OH)2, (b) sample after the reaction of Ca(OH)2 with H3PO4, and (c) hydroxyapatite obtained after calcination at 1000 °C. (D) SEM image of the hydroxyapatite obtained after calcination at 1000 °C.

Fig. 1A and b is the XRD pattern of the Ca(OH)2 sample after the reactions with H3PO4.

The XRD pattern of the Ca(OH)2 sample after the reaction with H3PO4 and subsequent sintering (Fig. 1B) was consistent with the XRD pattern of hydroxyapatite, according to the sheets JCPDS 09–0432 and JCPDS 74–0565. The presence of a small halo in the region of 15°–35° of 2θ, which is characteristic of amorphous material, indicates that the sintering of the material was not complete. However, there is no longer the incidence of XRD peaks attributed to Ca(OH)2 or CaCO3, indicating that in addition to the formation of hydroxyapatite, there was the conversion of Ca(OH)2 into other compounds, such as β-tricalcium phosphate (Ca3(PO4)2), (JCPDS 09–0169).

The FTIR spectra of the Ca(OH)2 sample obtained in the first step of synthesis (Fig. 1 C-a) showed bands attributed to the stretching of the O-H bond in the region above 3300 cm−1. The intense band at 3640 cm−1 is associated with the hydroxyl groups of the Ca(OH)2 compound, and the band in the region of 3400 cm−1 refers to the O-H bond of the water molecule. The bands in the 1460 cm−1 and 874 cm−1 regions are related to the out-of-plane bending of the carbonate group's C-O bond, indicating that there was a carbonation of the Ca(OH)2 sample.

In the FTIR spectrum of the sample obtained after the reaction of the Ca(OH)2 precursor with phosphoric acid (Fig. 1 C-b), there was a reduction in the band intensity related to the hydroxyls of the compound, but an increase in the O-H bond bands referring to the water molecule (stretch: 3400 cm−1 and 1640 cm−1). The FTIR spectrum of this sample also showed bands attributed to the P-O bond of the phosphate group. The bands at 960 cm−1 and 470 cm−1 were attributed to the ѵ1 and ѵ2 phosphate vibration, respectively.

For the sample obtained after calcination, the FTIR spectrum (Fig. 1C–c) showed a similar spectrum of the sample from the previous step, before calcination. The presence of bands is attributed to the O-H bond (region from 3300 cm−1 to 3600 cm−1) but with less intensity due to the temperature of the heat treatment (1000 °C). The bands referring to the phosphate group are also evident, located at 472 cm−1 (ѵ2), 568 cm−1 and 605 cm−1 (ѵ1), 943 and 971 cm−1 (ѵ4) e 1044, 1091, 1120 cm−1 (ѵ3).

The SEM image (Fig. 1D) shows the sample without its final compaction to form a scaffold. It presents morphology with submicrometric particles with spherical morphology.

The results of the ICP-OES analysis showed that the sample has a Ca/P ratio of 1.591 (Table 1), which is being in the range of values reported for β–Tricalcium phosphate (Ca/P = 1.5) and hydroxyapatite (Ca/P = 1.67) [19,45,46]. This result indicates a possible mixture of the two phases, corroborating the data obtained by X-ray diffractometry (Fig. 2B), in which signals referring to the two compositions were identified.

Table 1.

Calcium and phosphorus contents obtained by ICP-OES for the hydroxyapatite sample synthesized from mussel shell powder.

| Sample | Ca | P | Ca/P |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 0.614 | 0.386 | 1.591 |

Fig. 2.

Morphological and ultrastructural SEM analysis of the surface of bioceramics. (A–D) 150 mg bioceramic, (B–E) 200 mg, (C–F) 250 mg. Images (A), (B), and (C) show the surface morphology of different bioceramics. These have a circular shape (arrowhead) and smooth and regular surface to a lesser extent (arrow). Images (D), (E), and (F) show pores with different diameters and shapes (hollow arrow), and shows areas containing fractures, cracks, and irregular relief (hollow arrowhead). Assays were performed in triplicates.

3.2. Hydroxyapatite morphology in SEM

SEM of the bioceramics surfaces (Fig. 2). Images from (A)–(D) show the 150 mg, (B) to (E) the 200 mg, and (C) to (F) the 250 mg. Images (A), (B), and (C) of smaller magnification show the morphological pattern of these circular bioceramics with a diameter of 10 mm. The image shows a smooth and regular surface. In the other images at 30000 times magnification, the morphology is similar between the bioceramics. These have a large area of a smooth and regular surface. There are sparse areas with irregularities, which was more evident for the 150 mg bioceramic. The 150 mg bioceramic was the one that presented areas containing cracks or fractures, which indicate morphological characteristics of less compaction. Numerous pores with different morphologies and diameters were observed. There are areas with a lower degree of compaction and irregular relief with areas of fractures. Those are areas that integrate the surface of the biomaterial. For the 150 mg bioceramic, these areas are more frequent and evident.

3.3. Calcium and phosphorus leaching and SEM ultrastructural analysis of bioceramics after leaching test

The ICP-OES technique was also applied to evaluate the leaching of Ca and P from the samples in scaffold form (Fig. 3A and B). It is possible to notice that the levels of Ca released (Fig. 3A) were higher than those of phosphorus (Fig. 3B). This result was expected due to the more significant amount of calcium than phosphorus in the sample composition. However, the leaching of the elements did not follow the Ca/P ratio of 1.591 initially obtained in the ICP-OES. More Ca was leached for all samples. The sample prepared with 150 mg of HA (Pellet 150) showed larger leaching than the samples from Pellets 200 and 250. This behavior may be related to the surface of the pellets (Fig. 3C, D, E). The sample that contained 150 mg (Fig. 3C) of hydroxyapatite showed greater porosity and less compaction when compared to the other samples. In contrast, the 250 mg pressed sample was more compacted and had fewer pores (Fig. 3D), making it difficult for the ions to move to the solution. The 200 mg sample showed an intermediate surface characteristic between the largest and smallest pellet (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

ICP-OES technique: analyzing the release from the hydroxyapatite scaffolds over three days. Levels of Calcium released (A) and phosphorus (B) in scaffold samples of 150 mg (black line), 200 mg (red line) and 250 mg (blue line). SEM Analysis of the surface of the bioceramics before and after the leaching test. Images (C) 150 mg, (D) 200 mg, and (E) 250 mg show the control bioceramics without exposure to the liquid medium. Images (F) 150 mg, (G) 200 mg, and (H) 250 mg after 72 h of exposure. Image (C) shows areas of irregular relief (arrowhead) and less compacted (thin arrow). Images (D) and (E) show a smooth and irregular surface (closed arrow). Images (F), (G), and (H) show the decompression of the bioceramics after exposing them to a fluid medium (hollow arrow). Image (D) shows particulate matter (arrowhead).

After the leaching test, the scaffolds were analyzed again by SEM. In general, the samples showed increased surface porosity due to contact with water and the leaching of surface particles. Fig. 3C, D, and E show the control bioceramic surface without exposure to the liquid medium (Milli-Q Water), (C) 150 mg (D), 200 mg, and (E) 250 mg. Images (F) 150, (G) 200, and (H) 250 mg are of the surface of the bioceramics after 72 h of exposure to the liquid medium. It is evident for the 150 mg control bioceramics (C) the presence of a larger area of irregular relief, with characteristics of less compaction, presenting fractures, cracks, wear regions, and pores. Bioceramics (D) and (E) present ultrastructural similarity; they show a more regular surface with more compact morphological characteristics, wear regions, and irregular and less accentuated relief. After exposing these samples to the liquid medium, the increase in porosity of these bioceramics becomes evident. The 150 mg bioceramic (F) has particulate material on the surface. The relief of all bioceramics F, G, and H show irregularity and morphological characteristics of flocculus appearance, showing wear areas and, therefore, less compact architecture.

3.4. Cytotoxicity test

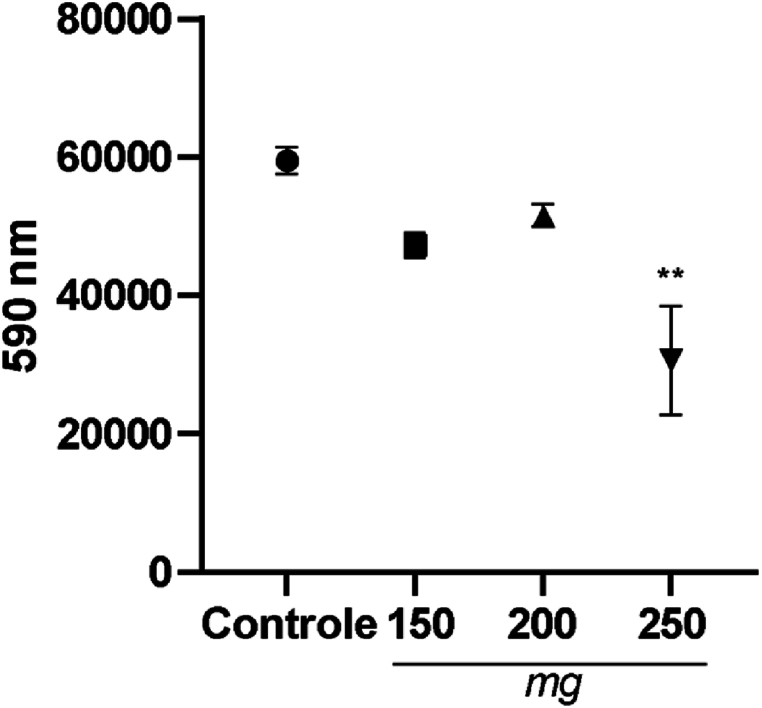

The Alamar Blue method was used to assess cell viability and proliferation. We chose the third day of maintenance for control cells and those exposed to bioceramics in cell culture to evaluate the in vitro results (Fig. 4). These results showed that 150 and 200 mg bioceramics were not cytotoxic compared to the control; only the 250 mg bioceramic had a significant reduction in cell proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Cell proliferation and viability test, Alamar Blue assay. BALB 3T3 cells (1.1x104 cells plated per well) were incubated with 150, 200, and 250 mg bioceramics for 72 h of exposure. Results were expressed as means of triplicate samples. ∗∗p < 0.01.

3.5. Morphological and ultrastructural evaluation of control cells and cells on bioceramics in SEM

The image (Fig. 5A) shows control cells plated on coverslips, image (Fig. 5B) cells plated on bioceramics with 150 (Fig. 5C), with 200, and (Fig. 5D) 250 mg for 72 h in an incubator at 37 °C at 5 % CO2. Image (A) shows cells adhered to the substrate with different morphologies and emitting expansions of the cell body and membrane extensions.

Fig. 5.

SEM ultrastructural evaluation of control cells and cells plated on bioceramics. The cells were maintained in cell culture for 72 h. Image (A) control cells plated on a circular coverslip maintained in the presence of medium only. Image (B) cells plated on 150 mg bioceramics. Image (C) 200 and (D) 250 mg, incubated at 37 °C 5 % CO2. Cells adhered to the substrate (arrowhead), cells with different morphologies (arrow thin), cell body expansions (closed arrow), membrane extensions (open arrow), juxtaposed cells (thin arrow with two heads), cells adsorbed to the substrate and spread out (curved arrow with double heads). Cell confluence (thick double-headed arrow), juxtaposition with contact inhibition forming a monolayer (triangular arrowhead), greater cell body volume, morphologically elongated cells (curved arrow), cells with less cell body expansion, emission of cell extensions and subconfluent (closed arrow with four heads). All images are at 2500x magnification.

A similar morphology can be observed for cells plated on the 150 mg bioceramic (Fig. 5B). They are more juxtaposed; the cell body is more adsorbed to the substrate, and the cells are more spread out. In Fig. 5C 200 mg, these cells showed clear cell confluence and juxtaposition, with contact inhibition forming a monolayer. Cells scattered, well adhered to the substrate. Evident greater cell body volume, morphologically more elongated when compared to control cells. Noteworthy is Fig. 5D, which contains the cells plated on the 250 mg bioceramic. There was a visible change in cell morphology; the cells that emit cell body extensions have less body expansion. There are a smaller number of cells in cell culture; they are subconfluent, with cell morphology losing adhesion to the substrate and emitting long and thin filopodia projections.

3.6. Immunocytochemistry in Confocal Laser Microscopy

We used Actingreen 488™ to detect actin microfilaments and DAPI to detect cell nuclei. Images (Fig.6A) and (Fig. 6E) are control cells plated on coverslips maintained in culture in the presence of medium for 72 h at 37 °C, 5 % CO2. Images (Fig. 6B) and (Fig. 6F) cells were plated on 150 mg bioceramic, images (Fig. 6C) and (Fig. 6G) cells were plated on 200 mg bioceramic, and (Fig. 6D) and (Fig. 6H) 250 mg.

Fig. 6.

Detection of actin microfilaments and cell nucleus in Confocal Laser Microscopy. Actingreen was used to detect microfilaments and DAPI to show the cell nucleus. Control cells (A) and (E), plated on coverslips, were maintained in the presence of the medium. Images (B) and (F) cells plated on 150 mg bioceramics, (C) and (G) 200, and (D) and (H) 250. Control and exposure to bioceramics cells were maintained in cell culture for 72 h. We evidence: the actin microfilaments (arrowhead); cell nucleus (thin arrow); adhered and spread cells with different morphologies, central and spherical nucleus (thick closed arrow); membrane extensions (open arrow); subconfluent cells (hollow arrowhead); overlapping cells (thin double-headed arrow); juxtaposed cells (four-headed arrow); cells with elongated morphology, spread over the substrate (triangular arrowhead); a predominance of the cell nucleus (curved arrow); cells with little spread, little cell volume (arrow with three heads). Images from (A–D) are at 40x magnification and from (E–H) at 60× magnification.

We can observe adhered and spread control cells over the substrate. They have different morphologies and central and spherical nuclei. There was intense staining for actin microfilaments occupying the entire cell volume, emitting membrane extensions in subconfluence.

Images (Fig. 6B) and (Fig. 6F) show several cells that adhered to the substrate, central and spherical nucleus. By the position of the nuclei, they are superimposed. There is an intense marking of the microfilaments occupying the entire cytoplasmic volume.

Images (Fig. 6C) and (Fig. 6D) show cells plated on 200 mg bioceramic. They also show characteristics similar to those described for cells plated on 150 mg bioceramic. The pattern in cell culture draws attention to them. They are juxtaposed, and due to the marking of the microfilaments, they present the morphology of elongated cells.

Images (Fig. 6D) and (Fig. 6H) show cells plated on 250 mg bioceramic with a clear predominance of cell nuclei in cell culture. Many cells are seen in the culture, and there is a minor marking for actin microfilaments, which is characteristic of poorly spread cells. They also have little cell volume and cells with difficulty organizing microfilaments to form stress fibers, structures that promote adhesion to the substrate. The nuclei are smaller, which is characteristic of cells in cellular distress.

4. Discussion

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of the biomaterial showed the Ca(OH)2 formation. This outcome is consistent with previously reported results [25], which synthesized calcium hydroxide from a mixture of NaOH and CaCl2 solutions. In addition to the diffraction peaks attributed to Ca(OH)2, diffraction peaks can also be attributed to a slight contamination of CaCO3 (JCPDS 85–1108). This result happens because when Ca(OH)2 is exposed to air, it reacts with CO2, and the carbonation reaction occurs rapidly, converting the material that is more superficially exposed to air [26,27].

In the work of [28], the compound obtained after the reaction of CaCO3 with H3PO4 was analyzed by XRD, and the authors reported the formation of different compounds, such as octacalcium phosphate and calcium monohydrogen phosphate. However, in our work, the XRD patterns showed the formation of Ca3(PO4)2, consistent with the JCPDS 09–0169 file, and that a small portion of Ca remains in the form of CaCO3 and Ca(OH)2. This result is due to slow kinetics in the reactions of solid particles with H3PO4.

The sample's XRD pattern showed the hydroxyapatite phase. Other authors [29,30] reported obtaining hydroxyapatite by different synthesis methods and under different pH conditions. However, the presence of a slight halo characteristic of amorphous material indicates that the sintering of the material obtained in this work was not complete, similar to other works, which have already reported a mixture between hydroxyapatite and β-tricalcium phosphate after sintering at different temperatures [[31], [32], [33]].

Hydroxyapatite was also obtained from oyster shells, but using another synthetic route that consists of converting calcium carbonate into calcium oxide, subsequent addition of acid, and calcination at 1200 °C [34].

If the temperature or sintering time had been increased, a purer hydroxyapatite sample could have been obtained. However, the presence of calcium phosphates formed together with the majority of the hydroxyapatite phase does not prevent the material from being used as a bone substitute with cellular proliferation [10], which is the objective of this study.

Analysis of the FTIR spectra of the Ca(OH)2 sample showed bands attributed to stretching of the O-H bond in the region above 3300 cm−1. The band at 1650 cm−1 is attributed to the bending of the O-H bond of water molecules [25,35]. The bands in the region of 1460 cm−1 and 874 cm−1 are related to the carbonation of the Ca(OH)2 sample since all the synthesis processes took place under atmospheric air, as well as the preparation of the sample with KBr to perform the FTIR analysis. Similar results have already been reported for obtaining Ca(OH)2 from the reaction between calcium chloride and sodium hydroxide [26] and also in reactions using a melting chamber and ingots of calcium oxides and H2 [27].

The FTIR spectrum showed bands attributed to the P-O bond of the phosphate group. Phosphate has four vibration modes: ѵ1, ѵ2, ѵ3, and ѵ4, which refer to symmetrical stretching, symmetrical deformation, asymmetrical stretching, and asymmetrical deformation, respectively. The bands of greater intensity are the ѵ3 bands, located at 1097 cm−1 and 1043 cm−1 and the ѵ4 bands, located at 605 cm−1 and 575 cm−1 [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]].

For the sample after calcination, the FTIR spectrum obtained was similar to the spectrum of the sample before calcination. Overall, the FTIR spectrum for this sample was similar to those reported for hydroxyapatite [9,29,36,[41], [42], [43]]. However, the FTIR spectra of hydroxyapatite and beta-tricalcium phosphate are very similar since the structures are similar, and, therefore, the compounds will present the same molecular vibrations, making it difficult to differentiate the two compounds solely by the spectrum. Despite this, when comparing the precursor before and after calcination, it is observed that the band at 960 cm−1 disappears and, according to Ref. [44], the disappearance of this band indicates a mixture of phases between hydroxyapatite and beta-tricalcium phosphate, confirming the results observed in XRD.

When observing the 1-D image of the calcined material without being pressed, the SEM image showed that the sample presents a morphology of submicrometric spherical particles, as observed in other studies that evaluated powdered hydroxyapatite [42] or other Ca/P bioceramics [31,43]. In addition, the particles are agglomerated with minor variations in size, indicating good connectivity and formation of networks of small grains, which may be characteristic of bioactive compounds [10]. The literature has also been reported that hydroxyapatite samples obtained at pH values close to 10 results in spherical and aggregated particles [30]. This porous morphology in these particles favors wettability, capillarity, and solubility. Also, it favors the conditions for cell proliferation that may occur from the particle's surface to the biomateril's interior, aiming to contribute to the process of early bone formation through osteoinduction and osseointegration of the biomaterial with adjacent tissues [[44], [45], [46]].

Fig. 2 shows the surface of the materials after compacting three different masses (150, 200, and 250 mg) using the same force (3 tons), resulting in materials with a flat surface and low porosity. This compaction was performed because the objective of the current research is to obtain a scaffold for tissue engineering. Using a vacuum muffle generated a material with a smooth surface and low porosity. The controlled environment allowed better cohesion between the chemical elements, resulting in a more compact, regular, and homogeneous microstructure, with changes in relief and almost no porosity. This surface, provided by vacuum sintering, contributes to increasing the mechanical resistance of the material obtained. This resistance favors the application in bone grafting; although porosity is essential to promote bioactivity and allow cell and nutrient infiltration, a material with fewer pores presents greater structural stability [47].

We highlight the impact of porosity on the biocompatibility of the biomaterial. Larger pores favor extracellular matrix infiltration but may compromise structural strength over time, especially in critical bone defects that require constant oxygen and nutrient supplementation. Biomaterials with porosity greater than 65 % offer greater interaction with the matrix but are more susceptible to degradation and pore blockage. On the other hand, materials with lower porosity, such as the one we developed, balance strength and bioactivity, which provide more reliable support for bone regeneration [48].

As the literature describes, bone tissue engineering requires a scaffold that will act as a temporary template for the cells. Guiding, therefore, bone repair, stimulating natural mechanisms of bone regeneration, mimicking the extracellular matrix, and, at the same time, providing mechanical support to the defect [[49], [50], [51]]. Thus, we developed a three-dimensional biomaterial aimed at bone tissue engineering. Our results demonstrate that bioceramics have promising morphological and structural characteristics to meet the specificity of in vitro studies and for future studies to evaluate the biotechnological potential of these parts for bone repair.

In Fig. 3-A and 3-B, we can observe through the graph that shows the leaching of Ca and P from the sample in scaffold form through the ICP-OES technique. That the levels of Ca released were higher than those of phosphorus. This was expected due to the more significant amount of calcium than phosphorus in the sample composition. After the leaching test, the scaffolds were analyzed again by SEM (Fig. 3-C). In general, the samples showed increased surface porosity due to contact with water and leaching of surface particles. To better understand the results of these SEM images, it is interesting to review some concepts. HA plays an essential role in cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation dynamics. Due to its slow degradation, it maintains spaces for the exchange of substances within the repair. β-TCP is a biocompatible, resorbable material and can act in osteoconduction. Upon simple dissolution, it rapidly releases calcium and phosphorus ions, contributing to initial osteogenic activities. Therefore, one of the hypotheses would be that this release is due to the amount of β-TCP in the biomaterial [52,53].

Thus, our scaffold has bioactive capacity and biodegradation once it contains HA and β-TCP. HA presents slow degradation, whereas β-TCP presents faster degradation, as shown in the leaching test through the ICP-OES assay [23,44]. In the SEM measurements, we could observe that when these ions were released into the environment, they modified the surface of these bioceramics. Initially, the biomaterial presents a smooth surface with microporosity (Fig. 2); after exposure and leaching (Fig. 3C–H), the surface becomes more irregular with greater porosity, having a less compact appearance, leaving small craters, and if we observe these craters (Fig. 3 F, G, H), we see that on the internal surface of the material, the particles present a morphology similar to the particles of the material without compaction.

The Alamar Blue method assessed cell viability and proliferation (Fig. 4). These results showed that 150 and 200 mg bioceramics were not cytotoxic; only the 250 mg bioceramic had a significant reduction in cell proliferation. A similar result was described by Ref. [54]. According to Ref. [55], they plated BALB/3T3 clone A31 and MC3T3 cells on hydroxyapatite biomaterial as lyophilized foam. These authors report that on the first day of exposure there was a significant decrease in the viability of BALB/3T3 clone A31 cells, around 70 %–80 %, compared to the control using the MTT method. The opposite result was described for the pre-osteoblastic MC3T3 cell line; cell viability was significantly increased. When using the formula to assess cell toxicity (author), our results did not significantly reduce cell proliferation compared to the control group for the 150 and 200 mg bioceramics. We obtained a decrease of 35 % only for the 250 mg bioceramic. These results are promising compared to those described in the literature, using the same cell line, with lower percentages of loss of cell viability. Because it is a 250 mg bioceramic, it was a biomaterial that morphologically presented a flatter, regular surface with a more compact morphological appearance.

With this result, it is worth highlighting that smoother surfaces with smaller porosities proved efficient for cell viability, proliferation, and adhesion dynamics, possibly due to their larger contact area, promoting efficient cell adhesion [56]. The importance of porosity and pore size of biomaterials is evident since they play a critical role in bone formation in vitro and in vivo. The literature reports that porosity is essential for cell communication [57,58]. However, smaller porosities stimulate osteogenesis, suppressing cell proliferation and forcing cell aggregation. It has been shown that biomaterials with small porosities induce hypoxic conditions, favoring osteochondral formation, preceding osteogenesis, and, on the other hand, larger pores favor neovascularization, leading to osteogenesis without prior cartilage formation [57].

In addition to the results presented in the calcium and phosphorus leaching technique, ICP-OES analyses were also performed. In this technique, the 250 mg biomaterial, when compared to the 150 mg and 200 mg, was the one that leached the lowest percentage of Ca (1.45) and P (0.36) into the cell culture medium. In fact, these factors effectively suggest the modulation of the loss of cell viability. Serum calcium and phosphorus concentrations are crucial for normal bone formation and mineralization [59]. Calcium cations are a versatile second messenger that regulates various cellular processes, including proliferation, gene transcription, aerobic metabolism, exocytosis, and synaptic plasticity [60].

To verify cell biocompatibility, regarding cell adhesion and proliferation, we used ISO 10993–5:2009 - a biological evaluation of medical devices, in vitro cytotoxicity test. The cell line used in this ISO was BALB/3T3 clone A31, thus justifying the choice of this line in our in vitro experimental model [61].

Biocompatibility is measured by evaluating the results of the viability, adhesion, and cell proliferation tests on the scaffolds. The 150 and 200 mg scaffolds showed many adhered cells and spread cells over the bioceramics. The 200 mg scaffold showed cells in a monolayer covering all the biomaterial. These biomaterials (150 and 200 mg) were more promising. The 250 mg was the least successful pellet for this cell line at this time of study among the three biomaterials studied. Future tests with pre-osteoblast MG3T3-and mesenchymal cell lines are interested in evaluating the possible action of these bioceramics aimed at biotechnological potential. According to Refs. [55,[59], [60], [61]], a biomaterial is promising if the cell lineage maintains its morphology and cell proliferation and gets attached to the biomaterial, covering its surface after cell plating on a biomaterial.

Our biomaterials presented a smoother surface with slight irregularity and little porosity, with different diameters and morphologies. Depending on the bioceramic, the surface showed a greater or lesser degree of wear and irregularities. These characteristics promoted good performance against the viability, adhesion, and cell proliferation dynamics, especially for two of the three bioceramics analyzed in Fig. 5 (150 mg 5-B and 200 mg 5-C).

Cell adhesion to the biomaterial surface is essential; it directs the active effects of cell proliferation and viability [62]. Due to its greater contact area, the smooth surface promotes better adhesion. On the other hand, the rougher surface restricts adhesion and cell proliferation [63].

We must also mention the role of porosity and pore size of biomaterials, which play a critical role in bone formation in vitro and in vivo. The literature reports that porosity is essential for cellular communication [64,65]. Smaller porosities stimulate osteogenesis by suppressing cell proliferation and forcing their aggregation. It is reported that biomaterials with small porosity induce hypoxic conditions, favoring osteochondral formation preceding osteogenesis. On the other hand, larger pores support neovascularization, leading to osteogenesis without prior cartilage formation [64].

The literature also reports that bone neoformation biomaterials are required in a minimum size of 100–300 μm, having a better response in studies for new bone formation and capillary formation. Also, smaller pores of 10–75 μm allow the penetration of fibrous tissue, which helps in the mechanical fixation of the biomaterial. Pores of 5–15 μm favor the growth of fibroblasts, and pores of 40–100 μm favor osteoid matrix formation [66]. It is necessary to find an ideal surface to evaluate the biotechnological potential of these bioceramics because the more significant the porosity, the lower the resistance of this biomaterial.

The biomaterials initially presented a smooth and regular surface with porosity and the described characteristics. As they were exposed to the culture medium, they were modified by releasing calcium and phosphorus ions by β TCP. The HA matrix remained to be colonized, and its degradability showed to be slower. Therefore, these biomaterials have great potential for in vitro studies. They are interested in studies with other cell lines to verify their biotechnological potential in other in vitro and in vivo models.

5. Conclusions

The results presented here describe the synthesis and characterization of biomaterials from mussel shell discards. We produced 150, 200, and 250 mg bioceramics with HA and β-TCP extracted from the mussel shells, each with a diameter of 10 mm. Prior to exposure to the liquid medium, they presented a regular smooth relief morphology with little porosity. After the leaching test, they presented important ultrastructural characteristics for biomaterials.

The in vitro results using the BALB/T3T clone A31 cell line showed promising results for cell viability, adhesion, proliferation, and morphology on the 150 and 200 mg scaffolds. Due to their similarity to bone hydroxyapatite, they showed important chemical, morphological, and ultrastructural characteristics.

The successful sintering of natural source bioceramics has a great potential to reduce costs. In addition, they come from renewable sources, generating recyclable source material and helping the environment. Its use in implant dentistry should be investigated in future studies using mesenchymal cells of dental origin. In vivo studies will be necessary to assess their biotechnological potential, test their capacity for bone neoformation and clinical use.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Sabrina Cunha da Fonseca: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Rosangela Borges Freitas: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Anne Raquel Sotiles: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Zelinda Schemczssen-Graeff: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Inaiê Maiala De Almeida Miranda: Writing – original draft. Stellee Marcela Petris Biscaia: Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Fernando Wypych: Writing. Edvaldo da Silva Trindade: Writing – review & editing. Moira Pedroso Leão: Writing – review & editing. João César Zielak: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Célia Regina Cavichiolo Franco: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) – Brazil– Finance Code 001, Conselho Nacional de Pesquisas - CNPq (FW: 303846/2014-3,400117/2016-9) and FINEP. S.C.F thanks CAPES for doctoral scholarship, A.R.S. thanks CNPq for the Postdoctoral scholarship (163817/2020-0), Z.S.G and S.M.P.B thanks Fundação Araucária and CAPES for Postdoctoral scholarships.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We also thank the Centro de Microscopia Eletrônica (CME-UFPR) for the SEM/EDS measurements, and Centro de Tecnologias Avançadas em Fluorescência (CTAF-UFPR), and to prof. Marco Tadeu Grassi and student Mayara Padovan dos Santos for the ICP-OES analysis and prof. Powder and Plasma Technology Laboratory (LTPP) Silvio Francisco Brunatto and student Felipe Gonçalves Jedyn for the assistance in obtaining and sintering the pellets. The Graphical Abstract in this article was created utilizing BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

Sabrina Cunha da Fonseca, Email: sabrina.cfonseca@hotmail.com.

Rosangela Borges Freitas, Email: ro.biologia@gmail.com.

Anne Raquel Sotiles, Email: anne.sotiles@gmail.com.

Zelinda Schemczssen-Graeff, Email: zelinda1985@hotmail.com.

Inaiê Maiala De Almeida Miranda, Email: inaie.miranda@aluno.fpp.edu.br.

Stellee Marcela Petris Biscaia, Email: stellee.biscaia@gmail.com.

Fernando Wypych, Email: wypych@ufpr.br.

Edvaldo da Silva Trindade, Email: estrindade@ufpr.br.

Moira Pedroso Leão, Email: moirapedroso@gmail.com.

João César Zielak, Email: jzielak@up.edu.br.

Célia Regina Cavichiolo Franco, Email: crcfranc@ufpr.br.

References

- 1.Gisbert-Garzarán M., Gómez-Cerezo M.N., Vallet-Regí M. Targeting agents in biomaterial-mediated bone regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24 doi: 10.3390/ijms24032007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halim N.A.A., Hussein M.Z., Kandar M.K. Nanomaterials-upconverted hydroxyapatite for bone tissue engineering and a platform for drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:6477–6496. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S298936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Twinprai N., Sutthi R., Ngaonee P., Chaikool P., Sookto T., Twinprai P., et al. Effects of hydroxyapatite content on cytotoxicity, bioactivity and strength of metakaolin/hydroxyapatite composites. Arab. J. Chem. 2024;17 doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105878. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mondal S., Dorozhkin S.V., Pal U. Recent progress on fabrication and drug delivery applications of nanostructured hydroxyapatite. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2018;10 doi: 10.1002/wnan.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scialla S., Carella F., Dapporto M., Sprio S., Piancastelli A., Palazzo B., et al. Mussel shell-derived macroporous 3D scaffold: characterization and optimization study of a bioceramic from the circular economy. Mar. Drugs. 2020;18 doi: 10.3390/md18060309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lara-Ochoa S., Ortega-Lara W., Guerrero-Beltrán C.E. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in drug delivery: physicochemistry and applications. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohner M., Santoni B.L.G., Döbelin N. β-tricalcium phosphate for bone substitution: synthesis and properties. Acta Biomater. 2020;113:23–41. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Panseri S., Montesi M., Dozio S.M., Savini E., Tampieri A., Sandri M. Biomimetic scaffold with aligned microporosity designed for dentin regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2016;4 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2016.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fathi M.H., Zahrani E.M. Fabrication and characterization of fluoridated hydroxyapatite nanopowders via mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 2009;475:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2008.07.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ezerskyte-Miseviciene A., Kareiva A. Everything old is new again: a reinspection of solid-state method for the fabrication of high quality calcium hydroxyapatite bioceramics. Mendeleev Commun. 2019;29:273–275. doi: 10.1016/j.mencom.2019.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Méndez-Lozano N., Apátiga-Castro M., Soto K.M., Manzano-Ramírez A., Zamora-Antuñano M., Gonzalez-Gutierrez C. Effect of temperature on crystallite size of hydroxyapatite powders obtained by wet precipitation process. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2022;26 doi: 10.1016/j.jscs.2022.101513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J., Wen Z., Zhong S., Wang Z., Wu J., Zhang Q. Synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanorods from abalone shells via hydrothermal solid-state conversion. Mater. Des. 2015;87:445–449. doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2015.08.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanur A.E., Gunari N., Sullan R.M.A., Kavanagh C.J., Walker G.C. Insights into the composition, morphology, and formation of the calcareous shell of the serpulid Hydroides dianthus. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;169:145–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohd Pu’ad, Koshy P., Abdullah H.Z., Idris M.I., Lee T.C. Syntheses of hydroxyapatite from natural sources. Heliyon. 2019;5 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e01588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agbeboh N.I., Oladele I.O., Daramola O.O., Adediran A.A., Olasukanmi O.O., Tanimola M.O. Environmentally sustainable processes for the synthesis of hydroxyapatite. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Bassyouni G.T., Eldera S.S., Kenawy S.H., Hamzawy E.M.A. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles derived from mussel shells for in vitro cytotoxicity test and cell viability. Heliyon. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes D.S., Santos A.M.C., Neves G.A., Menezes R.R. A brief review on hydroxyapatite production and use in biomedicine. Ceramic. 2019;65:282–302. doi: 10.1590/0366-69132019653742706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bohner B., Schuszter G., Berkesi O., Horváth D., Tóth Á. Self-organization of calcium oxalate by flow-driven precipitation. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:4289–4291. doi: 10.1039/c4cc00205a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferraz M.P., Monteiro F.J., Manuel C.M. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles: A review of preparation methodologies. J. Appl. Biomater. Biomech. 2004;2(2):74–80. doi: 10.1177/228080000400200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiume E., Magnaterra G., Rahdar A., Verné E., Baino F. Hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications: a short overview. Ceramics. 2021;4:542–563. doi: 10.3390/ceramics4040039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartatiek Yudyanto, Wuriantika M.I., Utomo J., Nurhuda M., Masruroh, et al. vol. 44. Elsevier Ltd; 2020. Nanostructure, porosity and tensile strength of PVA/Hydroxyapatite composite nanofiber for bone tissue engineering; pp. 3203–3206. (Mater Today Proc). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez T.N., Munevar C.J., Gonzalez M.J., Infante C., Lara J.P.S. In vitro response of dental pulp stem cells in 3D scaffolds: a regenerative bone material. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rohmadi R., Harwijayanti W., Ubaidillah U., Triyono J., Diharjo K., Utomo P. In vitro degradation and cytotoxicity of eggshell-based hydroxyapatite: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Polymers. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/polym13193223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cursaru L.M., Iota M., Piticescu R.M., Tarnita D., Savu S.V., Savu I.D., et al. Hydroxyapatite from natural sources for medical applications. Materials. 2022;15 doi: 10.3390/ma15155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khachani M., El Hamidi A., Halim M., Arsalane S. Non-isothermal kinetic and thermodynamic studies of the dehydroxylation process of synthetic calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)2. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2014;5:615–624. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirghiasi Z., Bakhtiari F., Darezereshki E., Esmaeilzadeh E. Preparation and characterization of CaO nanoparticles from Ca(OH)2 by direct thermal decomposition method. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014;20:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2013.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu T., Zhu Y., Zhang X., Zhang T., Zhang T., Li X. Synthesis and characterization of calcium hydroxide nanoparticles by hydrogen plasma-metal reaction method. Mater. Lett. 2010;64:2575–2577. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2010.08.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y., Yin G., Zhu S., Zhou D., Wang Y., Li Y., et al. Preparation of β-Ca3(PO4)2 bioceramic powder from calcium carbonate and phosphoric acid. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2005;5:531–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cap.2005.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rigo C.S., Gehrke S.A., Carbonari M. Synthesis and characterization of hydroxyapatite. Rev Dental Press Periodontia Implantol. 2007;1:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva C.C., Rocha H.H.B., Freire F.N.A., Santos M.R.P., Saboia K.D.A., Góes J.C., et al. Hydroxyapatite screen-printed thick films: optical and electrical properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005;92:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang P., Li C., Gong H., Jiang X., Wang H., Li K. Effects of synthesis conditions on the morphology of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles produced by wet chemical process. Powder Technol. 2010;203:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2010.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaygili O., Tatar C., Yakuphanoglu F. Structural and dielectrical properties of Mg3-Ca3(PO4)2 bioceramics obtained from hydroxyapatite by sol-gel method. Ceram. Int. 2012;38:5713–5722. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piccirillo C., Silva M.F., Pullar R.C., Braga Da Cruz I., Jorge R., Pintado M.M.E., et al. Extraction and characterisation of apatite- and tricalcium phosphate-based materials from cod fish bones. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2013;33:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rujitanapanich S., Kumpapan P., Wanjanoi P. vol. 56. Elsevier Ltd; 2014. pp. 112–117. (Synthesis of Hydroxyapatite from Oyster Shell via Precipitation. Energy Procedia). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blesa M.J., Miranda J.L., Izquierdo M.T., Moliner R. Study of the curing temperature effect on binders for smokeless briquettes by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Vib. Spectrosc. 2003;31:81–87. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2031(02)00097-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murugan R., Ramakrishna S. Aqueous mediated synthesis of bioresorbable nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite. J. Cryst. Growth. 2005;274:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.09.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frost R.L., Xi Y., Scholz R., López A., Belotti F.M. Vibrational spectroscopic characterization of the phosphate mineral hureaulite-(Mn, Fe)5(PO4)2(HPO4)2·4(H2O) Vib. Spectrosc. 2013;66:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vibspec.2013.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campos P.V., Albuquerque A.R.L., Angélica R.S., Paz S.P.A. FTIR spectral signatures of amazon inorganic phosphates: igneous, weathering, and biogenetic origin. Spectrochim. Acta Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021;251 doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2021.119476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoch P., Stoch A., Ciecinska M., Krakowiak I., Sitarz M. Structure of phosphate and iron-phosphate glasses by DFT calculations and FTIR/Raman spectroscopy. J. Non-Cryst. Solids. 2016;450:48–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2016.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartatiek Yudyanto, Wuriantika M.I., Utomo J., Nurhuda M., Masruroh, Santjojo D.J.D.H. Nanostructure, porosity and tensile strength of PVA/hydroxyapatite composite nanofiber for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 2020;44:3203–3206. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.11.438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kheradmandfard M., Fathi M.H. Fabrication and characterization of nanocrystalline Mg-substituted fluorapatite by high energy ball milling. Ceram. Int. 2013;39:1651–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sadetskaya A.V., Bobrysheva N.P., Osmolowsky M.G., Osmolovskaya O.M., Voznesenskiy M.A. Correlative experimental and theoretical characterization of transition metal doped hydroxyapatite nanoparticles fabricated by hydrothermal method. Mater Charact. 2021;173 doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2021.110911. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussin M.S.F., Abdullah H.Z., Idris M.I., Wahap M.A.A. Extraction of natural hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications—a review. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ganesan V., Devaraj M., Govindan S.K., Kattimani V.S., Easwaradas Kreedapathy G. Eggshell derived mesoporous biphasic calcium phosphate for biomedical applications using rapid thermal processing. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2019;16:1932–1943. doi: 10.1111/ijac.13270. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li X., Wang Y., Chen F., Chen X., Xiao Y., Zhang X. Design of macropore structure and micro-nano topography to promote the early neovascularization and osteoinductivity of biphasic calcium phosphate bioceramics. Mater. Des. 2022;216 doi: 10.1016/j.matdes.2022.110581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva D.F. da Desenvolvimento de Biocerâmicas de Origem Fossilizada Para Reconstrução e Neoformação Óssea. 1st edition. Editora Appris; Curitiba/P: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bose S., Tarafder S. Calcium phosphate ceramic systems in growth factor and drug delivery for bone tissue engineering: a review. Acta Biomater. 2012;8(4):1401–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Koushik T.M., Miller C.M., Antunes E. Bone tissue engineering scaffolds: function of multi-material hierarchically structured scaffolds. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2023;12(9) doi: 10.1002/adhm.202202766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.García A., Cabañas M.V., Peña J., Sánchez-Salcedo S. Design of 3d scaffolds for hard tissue engineering: from apatites to silicon mesoporous materials. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13111981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liang H., Wang Y., Chen S., Liu Y., Liu Z., Bai J. Nano-hydroxyapatite bone scaffolds with different porous structures processed by digital light processing 3D printing. Int J Bioprint. 2022;8:198–210. doi: 10.18063/IJB.V8I1.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rezania N., Asadi-Eydivand M., Abolfathi N., Bonakdar S., Mehrjoo M., Solati-Hashjin M. Three-dimensional printing of polycaprolactone/hydroxyapatite bone tissue engineering scaffolds mechanical properties and biological behavior. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2022;33 doi: 10.1007/s10856-022-06653-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Swain S., Koduru J.R., Rautray T.R. Mangiferin-enriched Mn–hydroxyapatite coupled with β-TCP scaffolds simultaneously exhibit osteogenicity and anti-bacterial efficacy. Materials. 2023;16 doi: 10.3390/ma16062206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zamora I., Alfonso Morales G., Castro J.I., Ruiz Rojas L.M., Valencia-Llano C.H., Mina Hernandez JH., et al. Chitosan (CS)/Hydroxyapatite (HA)/Tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP)-Based composites as a potential material for pulp tissue regeneration. Polymers. 2023;15 doi: 10.3390/polym15153213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumar G.S., Girija E.K. Flower-like hydroxyapatite nanostructure obtained from eggshell: a candidate for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int. 2013;39:8293–8299. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.03.099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winnett J., Jumbu N., Cox S., Gibbons G., Grover L.M., Warnett J., et al. In-vitro viability of bone scaffolds fabricated using the adaptive foam reticulation technique. Biomater. Adv. 2022;136 doi: 10.1016/j.bioadv.2022.212766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mokabber T., Zhou Q., Vakis A.I., van Rijn P., Pei Y.T. Mechanical and biological properties of electrodeposited calcium phosphate coatings. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;100:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.020. Epub 2019 Mar 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karageorgiou V., Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26(27):5474–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moreau A., Gosselin-Badaroudine P., Chahine M. Molecular biology and biophysical properties of ion channel gating pores. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2014;47(4):364–388. doi: 10.1017/S0033583514000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eklou-Kalonjí Denis E.I., Lieberherr Pointillart M.A., Eklou-Kalonji E., Denis I., Pointillart A., Lieberherr M. vol. 292. Springer-Verlag; 1998. (Effects of Extracellular Calcium on the Proliferation and Differentiation of Porcine Osteoblasts in Vitro). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parys J.B., Guse A.H. Full focus on calcium. Sci. Signal. 2019;12 doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaz0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Camargo E. da R., Hamdar K.Z., dos Santos M.L.F., Burgel G., de Oliveira C.C., Kava V., et al. Plasma-assisted silver deposition on titanium surface: biocompatibility and bactericidal effect. Mater. Res. 2021;24 doi: 10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2020-0569. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zygmuntowicz J., Zima A., Czechowska J., Szlazak K., Ślosarczyk A., Konopka K. Quantitative stereological analysis of the highly porous hydroxyapatite scaffolds using X-ray CM and SEM. Bio Med. Mater. Eng. 2017;28:235–246. doi: 10.3233/BME-171670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mokabber T., Zhou Q., Vakis A.I., van Rijn P., Pei Y.T. Mechanical and biological properties of electrodeposited calcium phosphate coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. C. 2019;100:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karageorgiou V., Kaplan D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5474–5491. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moreau A., Gosselin-Badaroudine P., Chahine M. Molecular biology and biophysical properties of ion channel gating pores. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2014;47:364–388. doi: 10.1017/S0033583514000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fook A.C.B.M., Aparecida A.H., Fook M.V.L. Desenvolvimento de Biocerâmicas Porosas de Hidroxiapatita Para Utilização Como Scaffolds Para Regeneração Óssea. Rev. Mater. 2010;15:392–399. [Google Scholar]