Abstract

Introduction

Increased intramucosal–arterial carbon dioxide tension (PCO2) difference (ΔPCO2) is common in experimental endotoxemia. However, its meaning remains controversial because it has been ascribed to hypoperfusion of intestinal villi or to cytopathic hypoxia. Our hypothesis was that increased blood flow could prevent the increase in ΔPCO2.

Methods

In 19 anesthetized and mechanically ventilated sheep, we measured cardiac output, superior mesenteric blood flow, lactate, gases, hemoglobin and oxygen saturations in arterial, mixed venous and mesenteric venous blood, and ileal intramucosal PCO2 by saline tonometry. Intestinal oxygen transport and consumption were calculated. After basal measurements, sheep were assigned to the following groups, for 120 min: (1) sham (n = 6), (2) normal blood flow (n = 7) and (3) increased blood flow (n = 6). Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide (5 μg/kg) was injected in the last two groups. Saline solution was used to maintain blood flood at basal levels in the sham and normal blood flow groups, or to increase it to about 50% of basal in the increased blood flow group.

Results

In the normal blood flow group, systemic and intestinal oxygen transport and consumption were preserved, but ΔPCO2 increased (basal versus 120 min endotoxemia, 7 ± 4 versus 19 ± 4 mmHg; P < 0.001) and metabolic acidosis with a high anion gap ensued (arterial pH 7.39 versus 7.35; anion gap 15 ± 3 versus 18 ± 2 mmol/l; P < 0.001 for both). Increased blood flow prevented the elevation in ΔPCO2 (5 ± 7 versus 9 ± 6 mmHg; P = not significant). However, anion-gap metabolic acidosis was deeper (7.42 versus 7.25; 16 ± 3 versus 22 ± 3 mmol/l; P < 0.001 for both).

Conclusions

In this model of endotoxemia, intramucosal acidosis was corrected by increased blood flow and so might follow tissue hypoperfusion. In contrast, anion-gap metabolic acidosis was left uncorrected and even worsened with aggressive volume expansion. These results point to different mechanisms generating both alterations.

Keywords: Carbon dioxide, oxygen consumption, blood flow, endotoxemia, metabolic acidosis

Introduction

Rapid resolution of tissue hypoxia is the cornerstone of the treatment of sepsis and septic shock [1]. Patients who spontaneously develop high oxygen transport have better outcomes [2]. In experimental models of sepsis, animals with spontaneous elevation of oxygen transport present improved survival [3]. In addition, mortality from sepsis and septic shock could be reduced by early goal-directed therapy [4].

The intramucosal minus arterial carbon dioxide tension (PCO2) gradient (ΔPCO2) is considered a sensitive marker of regional gut perfusion [5] and is frequently found in human sepsis and in experimental endotoxemia. Because intramucosal acidosis can appear with normal or increased blood flow, it has been ascribed to a defect in cellular metabolism, namely cytopathic hypoxia [6]. It has also been related to decreased perfusion of villi [7]. Vasodilators might correct these microcirculatory deficits [8-10], but volume expansion or inotropic drugs have often failed to reverse intramucosal acidosis [11-14].

Our goal was to evaluate the effects of supranormal elevations of blood flow on oxygen transport and tissue oxygenation in a sheep model of endotoxemia. Our hypothesis was that increased blood flow could prevent the increase in ΔPCO2 and improve systemic metabolic acidosis.

Methods

Surgical preparation

Nineteen sheep were anesthetized with 30 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, then intubated and mechanically ventilated (Dual Phase Control Respirator Pump Ventilator; Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA, USA) with a tidal volume of 15 ml/kg, a fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) of 0.21 and positive end-expiratory pressure adjusted to maintain O2 arterial saturation at more than 90%. The respiratory rate was set to keep the end-tidal PCO2 at 35 mmHg. Neuromuscular blockade was performed with intravenous pancuronium bromide (0.06 mg/kg). Additional pentobarbital boluses (1 mg/kg per hour) were administered as required.

Catheters were advanced through the left femoral vein to administer fluids and drugs, and through the left femoral artery to measure blood pressure and to obtain blood gases. A pulmonary artery catheter was inserted through right external jugular vein (Flow-directed thermodilution fiberoptic pulmonary artery catheter; Abbott Critical Care Systems, Mountain View, CA, USA).

An orogastric tube was inserted to allow drainage of gastric contents. A midline laparotomy and splenectomy were then performed. An electromagnetic flow probe was placed around the superior mesenteric artery to measure intestinal blood flow. A catheter was placed in the mesenteric vein through a small vein proximal to the gut to draw blood gases. A tonometer was inserted through a small ileotomy to measure intramucosal PCO2. Lastly, after careful hemostasis, the abdominal wall incision was closed.

Measurements and derived calculations

Arterial, systemic, pulmonary and central venous pressures were measured with corresponding transducers (Statham P23 AA; Statham, Halo Rey, Puerto Rico). Cardiac output was measured by thermodilution with 5 ml of saline solution (HP OmniCare Model 24 A 10; Hewlett Packard, Andover, MA, USA) at 0°C. An average of three measurements taken randomly during the respiratory cycle were considered and were normalized to body weight to yield Q. Intestinal blood flow was measured by the electromagnetic method (Spectramed Blood Flowmeter model SP 2202 B; Spectramed Inc., Oxnard, CA, USA) with in vitro calibrated transducers 5–7 mm in diameter (Blood Flowmeter Transducer; Spectramed Inc.). Occlusive zero was controlled before and after each experiment. Non-occlusive zero was corrected before each measurement. Superior mesenteric blood flow was normalized to gut weight (Qintestinal).

Arterial, mixed venous and mesenteric venous partial pressure of oxygen (PO2), PCO2 and pH were measured with a blood gas analyzer (ABL 5; Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark), and hemoglobin and oxygen saturation were measured with a co-oximeter calibrated for sheep blood (OSM 3; Radiometer). Arterial, mixed venous and mesenteric venous contents (CaO2, CvO2 and CvmO2, respectively) were calculated as (Hb × 1.34 × O2 saturation) + (PO2 × 0.0031). Systemic and intestinal oxygen transport and oxygen consumption (DO2, VO2, DO2i and VO2i, respectively) were calculated as DO2 = Q × CaO2; VO2 = Q × (CaO2 - CvO2); DO2i = Qintestinal × CaO2, and VO2i = Qintestinal × (CaO2 - CvmO2).

Intramucosal PCO2 was measured with a tonometer [15] (TRIP Sigmoid Catheter; Tonometrics, Inc., Worcester, MA, USA) filled with 2.5 ml of saline solution; 1.0 ml was discarded after an equilibration period of 30 min and PCO2 was measured in the remaining 1.5 ml. Its value was corrected to the corresponding equilibration period and was used to calculate ΔPCO2.

Mixed venous–arterial and mesenteric venous–arterial PCO2 differences were also calculated. Arterial, mixed venous and mesenteric venous CO2 contents (CCO2) and their differences were calculated with Douglas's algorithm [16]. Systemic and intestinal CO2 production (VCO2 and VCO2i, respectively) were calculated as VCO2 = Q × mixed venoarterial CCO2, and VCO2i = Qintestinal × mesenteric venoarterial CCO2. Global blood capacity for transporting CO2 was evaluated as the ratio between venoarterial CCO2 and PCO2 differences (Ra-v). This index has been used to evaluate the amount of CO2 transported by the blood in relation to the venoarterial gradient of PCO2 [17].

Lactate, sodium, potassium, chloride and serum total proteins were measured with an automatic analyzer every 60 min (Automatic Analyzer Hitachi 912; Boehringer Mannheim Corporation, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Anion gap was calculated as ([Na+] + [K+]) - ([Cl-] + [HCO3-]). Anion gap was corrected for changes in plasma protein concentration [18].

Experimental procedure

Basal measurements were taken after a stabilization period longer than 30 min. Then animals were assigned to the following groups: (1) sham group (n = 6), consisting of sheep receiving 100 ml of saline in 10 min, followed by an infusion necessary to keep intestinal blood flow at basal levels; (2) normal blood flow group (n = 7), consisting of sheep receiving 5 μg/kg Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide dissolved in 100 ml of saline in 10 min, and then saline infusion so as to maintain intestinal blood flow at basal levels; and (3) increased blood flow group (n = 6), consisting of sheep receiving 5 μg/kg Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide dissolved in 100 ml of saline in 10 min, followed by saline infusion so as to increase intestinal blood flow by 50% from basal levels.

FIO2 was increased to 0.50 in endotoxemic sheep to avoid deep hypoxemia.

Measurements were performed at 30 min intervals for 120 min from the start of endotoxin administration.

At the end of the experiment, the animals were killed with an additional dose of pentobarbital and a KCl bolus. A catheter was inserted in the superior mesenteric artery and Indian ink was instilled through it. Dyed intestinal segments were dissected, washed and weighed for the calculation of gut indexes.

The local Animal Care Committee approved the study. Care of animals was in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines.

Statistical analysis

Data were assessed for normality and expressed as means ± SD. Differences within groups were analyzed with a repeated-measures analysis of variance and Dunnett's multiple comparisons test to compare each time point with basal. One-time comparisons between groups were tested with a one-way analysis of variance and a Newman–Keuls multiple comparison test.

Results

Hemodynamic and oxygen transport effects

Sham, normal blood flow and increased blood flow groups received 10 ± 6, 24 ± 9 and 91 ± 38 ml/kg per hour, respectively, of normal saline solution (P < 0.05) to achieve resuscitation goals. Variations of intestinal blood flow from basal values, at the end of the experiment, were 8 ± 5%, – 1 ± 22% and 60 ± 22%, respectively (P < 0.05). As expected, the increased blood flow group had higher central venous and pulmonary wedge pressures, intestinal blood flow, cardiac output and systemic oxygen transport than the normal blood flow group. The increased blood flow group had also higher intestinal oxygen consumption (Table 1).

Table 1.

Systemic and intestinal hemodynamic and oxygen transport parameters in sham, normal and increased blood flow groups

| Parameter | Group | Basal | Endotoxemia | |||

| 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min | |||

| Mean arterial pressure (mmHg) | Sham | 81 ± 10 | 85 ± 15 | 88 ± 15 | 91 ± 16 | 92 ± 19 |

| Normal | 93 ± 19 | 89 ± 25 | 83 ± 23 | 91 ± 32 | 94 ± 26 | |

| Increased | 90 ± 17 | 98 ± 17 | 89 ± 18 | 89 ± 21 | 99 ± 17 | |

| Mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mmHg) | Sham | 16 ± 3 | 15 ± 3 | 16 ± 3 | 15 ± 4 | 16 ± 4 |

| Normal | 15 ± 5 | 34 ± 9*† | 26 ± 8*† | 25 ± 7*† | 24 ± 6*† | |

| Increased | 20 ± 4 | 35 ± 10*† | 31 ± 4*† | 34 ± 6*†‡ | 35 ± 6*†‡ | |

| Pulmonary wedge pressure (mmHg) | Sham | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 1 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

| Normal | 5 ± 2 | 11 ± 4*† | 8 ± 2*† | 8 ± 3*† | 8 ± 4 | |

| Increased | 6 ± 1 | 11 ± 4*† | 13 ± 6*† | 12 ± 3*† | 14 ± 5*†‡ | |

| Central venous pressure (mmHg) | Sham | 5 ± 5 | 5 ± 3 | 6 ± 5 | 5 ± 4 | 5 ± 4 |

| Normal | 4 ± 2 | 5 ± 3 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 3 | |

| Increased | 4 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | 9 ± 5* | 10 ± 4*†‡ | 11 ± 4*†‡ | |

| Cardiac output (ml/kg per min) | Sham | 134 ± 30 | 148 ± 36 | 153 ± 37 | 144 ± 33 | 151 ± 41 |

| Normal | 139 ± 43 | 117 ± 27 | 135 ± 38 | 149 ± 42 | 142 ± 34 | |

| Increased | 157 ± 51 | 221 ± 64*†‡ | 257 ± 67*†‡ | 276 ± 84*†‡ | 290 ± 91*†‡ | |

| Superior mesenteric artery blood flow (ml/min per g) | Sham | 498 ± 107 | 568 ± 126* | 551 ± 126* | 548 ± 134* | 539 ± 131* |

| Normal | 553 ± 184 | 514 ± 152 | 566 ± 161 | 573 ± 145 | 529 ± 169 | |

| Increased | 578 ± 206 | 803 ± 226*‡ | 794 ± 209*†‡ | 863 ± 326*‡ | 923 ± 370*†‡ | |

| Increased | 362 ± 116 | 437 ± 75†‡ | 286 ± 53 | 336 ± 102 | 295 ± 75 | |

| Systemic oxygen transport (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 16.2 ± 4.5 | 18.0 ± 5.6* | 19.0 ± 6.2* | 17.8 ± 5.3 | 18.8 ± 6.1* |

| Normal | 16.4 ± 6.6 | 13.3 ± 4.9 | 14.0 ± 4.8 | 16.4 ± 6.4 | 15.8 ± 5.7 | |

| Increased | 17.2 ± 4.0 | 23.0 ± 5.5*‡ | 25.5 ± 6.7*‡ | 26.0 ± 8.4*‡ | 26.9 ± 9.9*‡ | |

| Systemic oxygen consumption (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 6.4 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 7.2 ± 1.3 |

| Normal | 6.4 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.2* | 5.8 ± 1.6* | 6.0 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 1.4 | |

| Increased | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 7.6 ± 2.0‡ | 7.3 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 2.2 | 8.3 ± 3.2 | |

| Intestinal oxygen transport (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 62.3 ± 22.2 | 71.4 ± 24.8* | 70.8 ± 25.1* | 69.9 ± 24.6* | 69.1 ± 24.0* |

| Normal | 64.0 ± 22.6 | 56.1 ± 19.3 | 57.0 ± 15.8 | 60.8 ± 18.4 | 56.5 ± 17.0 | |

| Increased | 64.3 ± 16.7 | 86.4 ± 19.1*‡ | 81.4 ± 22.1* | 82.2 ± 23.5* | 87.1 ± 23.6*‡ | |

| Intestinal oxygen consumption (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 21.7 ± 4.0 | 21.1 ± 3.7 | 22.0 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 4.2 | 21.8 ± 4.7 |

| Normal | 21.2 ± 4.1 | 22.1 ± 6.5 | 22.7 ± 8.9 | 22.6 ± 7.8 | 22.4 ± 9.0 | |

| Increased | 29.3 ± 9.7 | 28.9 ± 9.3 | 32.5 ± 13.0 | 29.8 ± 9.4 | 37.2 ± 12.3†‡ | |

* P < 0.05 versus basal. † P < 0.05 versus sham. ‡ P < 0.05 versus normal. Sham, sham group; normal, normal blood flow group; increased, increased blood flow group.

Metabolic effects

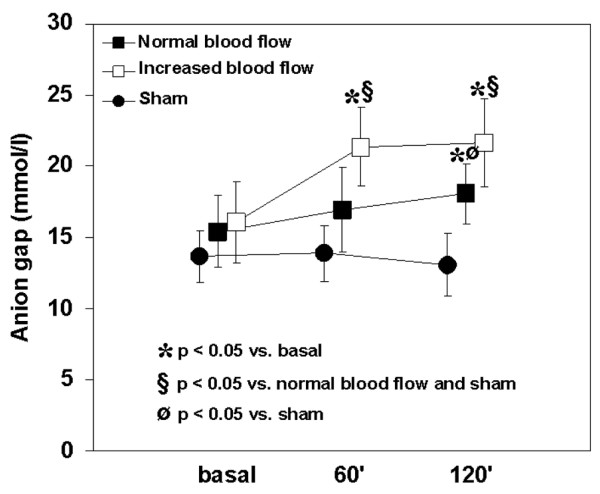

Metabolic acidosis developed in both groups with endotoxemia, but was greater in the increased blood flow group because of hyperchloremia and an increased anion gap (Table 2 and Fig. 1). These variables did not change in the sham group. Lactate levels remained stable in the three groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Arterial hemoglobin, acid-base and metabolic parameters in sham, normal and increased blood flow groups

| Parameter | Group | Basal | Endotoxemia | |||

| 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/l) | Sham | 9.6 ± 2.4 | 9.7 ± 2.7 | 9.9 ± 2.3 | 9.8 ± 2.2 | 9.9 ± 2.2 |

| Normal | 9.1 ± 2.3 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 8.4 ± 2.0* | 8.1 ± 2.2* | 8.3 ± 2.4* | |

| Increased | 8.9 ± 2.2 | 8.2 ± 2.3* | 7.8 ± 2.4* | 7.6 ± 2.5* | 7.7 ± 2.5* | |

| pH | Sham | 7.44 ± 0.03 | 7.45 ± 0.02 | 7.45 ± 0.03 | 7.47 ± 0.02 | 7.47 ± 0.03 |

| Normal | 7.39 ± 0.07 | 7.34 ± 0.08*† | 7.31 ± 0.05*† | 7.34 ± 0.05*† | 7.35 ± 0.06*† | |

| Increased | 7.42 ± 0.04 | 7.35 ± 0.05*† | 7.31 ± 0.05*† | 7.28 ± 0.08*† | 7.25 ± 0.08*†‡ | |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 35 ± 3 | 34 ± 3 | 34 ± 3 | 33 ± 3 | 34 ± 4 |

| Normal | 35 ± 4 | 38 ± 6* | 41 ± 7* | 37 ± 6 | 35 ± 6 | |

| Increased | 34 ± 2 | 36 ± 5 | 34 ± 3 | 34 ± 5 | 37 ± 6 | |

| PO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 85 ± 13 | 88 ± 18 | 86 ± 16 | 88 ± 17 | 84 ± 15 |

| Normal | 87 ± 16 | 119 ± 59 | 105 ± 39 | 123 ± 20*† | 134 ± 43*† | |

| Increased | 90 ± 23 | 150 ± 48*† | 132 ± 21*† | 101 ± 20 | 99 ± 31 | |

| [HCO3-] (mmol/l) | Sham | 24 ± 2 | 24 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 | 24 ± 3 |

| Normal | 21 ± 2 | 21 ± 2 | 20 ± 2† | 20 ± 2*† | 19 ± 2*† | |

| Increased | 22 ± 3 | 20 ± 2*† | 17 ± 3*† | 16 ± 3*†‡ | 16 ± 2*†‡ | |

| Base excess (mmol/l) | Sham | 1 ± 3 | 1 ± 3 | 1 ± 3 | 2 ± 3 | 2 ± 3 |

| Normal | t2 ± 4 | t5 ± 3*† | t5 ± 2*† | t5 ± 3*† | t5 ± 3*† | |

| Increased | t1 ± 4 | t4 ± 3*† | t8 ± 4*† | t10 ± 4*† | t10 ± 3*†‡ | |

| [Cl-]/[Na+] | Sham | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | 0.76 ± 0.03 | ||

| Normal | 0.76 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.02 | 0.77 ± 0.01 | |||

| Increased | 0.76 ± 0.02 | 0.78 ± 0.02* | 0.80 ± 0.02*†‡ | |||

| Lactate (mmol/l) | Sham | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | ||

| Normal | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | |||

| Increased | 2.2 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 1.9 ± 1.1 | |||

* P < 0.05 versus basal. † P < 0.05 versus sham. ‡ P < 0.05 versus normal. Sham, sham group; normal, normal blood flow group; increased, increased blood flow group.

Figure 1.

Behavior of the anion gap in the sham, normal and increased blood flow groups. A higher degree of anion-gap metabolic acidosis developed in the increased blood flow group than in the normal blood flow group. The anion gap was unchanged in the sham group. 60' and 120' refer to 60 and 120 min, respectively.

Effects on ΔPCO2 and its determinants

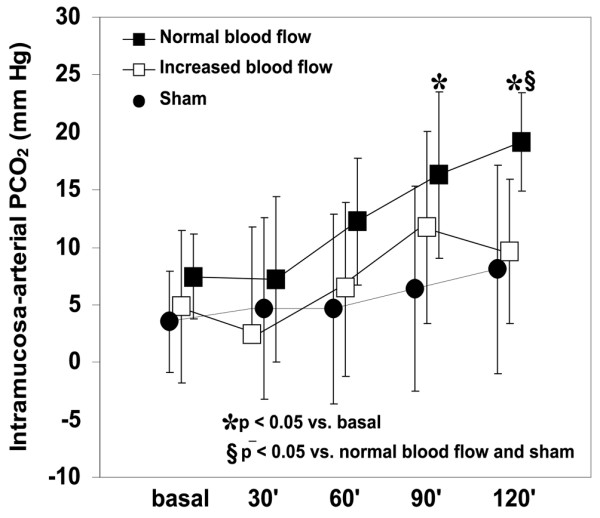

ΔPCO2 increased in the normal blood flow group and remained unchanged in the increased blood flow and sham groups (Fig. 2). Systemic and intestinal venoarterial PCO2 differences were also higher in the normal blood flow group than in the others (Table 3). Systemic and intestinal Ra-v were lower in both endotoxemic groups.

Figure 2.

Behavior of intramucosal – arterial PCO2 difference in the sham, normal and increased blood flow groups. Intramucosal acidosis developed in the normal blood flow group and was prevented in the increased blood flow group. Intramucosal – arterial PCO2 difference was unchanged in the sham group. 30', 60', 90' and 120' refer to 30, 60, 90 and 120 min, respectively.

Table 3.

Systemic and intestinal CO2-derived parameters in sham, normal and increased blood flow groups

| Parameter | Group | Basal | Endotoxemia | |||

| 30 min | 60 min | 90 min | 120 min | |||

| Mixed venous – arterial PCO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

| Normal | 7 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 7 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | 8 ± 3† | |

| Increased | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 3 | 7 ± 5 | 7 ± 4 | 4 ± 1‡ | |

| Mesenteric venous – arterial PCO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 |

| Normal | 7 ± 2 | 8 ± 2 | 8 ± 3 | 10 ± 4 | 10 ± 2*† | |

| Increased | 8 ± 3 | 6 ± 2 | 8 ± 4 | 8 ± 3 | 6 ± 1*‡ | |

| Intramucosal – arterial PCO2 (mmHg) | Sham | 4 ± 4 | 5 ± 8 | 5 ± 8 | 5 ± 8 | 6 ± 9 |

| Normal | 7 ± 4 | 6 ± 5 | 12 ± 5 | 15 ± 6*‡ | 19 ± 4*‡ | |

| Increased | 5 ± 7 | 2 ± 9 | 7 ± 7 | 12 ± 8 | 9 ± 6† | |

| Systemic VCO2 (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 5.2 ± 1.9 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.5 | 4.7 ± 1.2 | 4.6 ± 1.8 |

| Normal | 6.0 ± 2.4 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | 4.9 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 1.3 | 5.0 ± 1.7 | |

| Increased | 6.5 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 6.1 ± 2.8 | 5.8 ± 2.3 | 5.8 ± 4.7 | |

| Intestinal VCO2 (ml/min per kg) | Sham | 36.7 ± 10.9 | 38.1 ± 11.3 | 34.0 ± 8.8 | 43.2 ± 10.6 | 36.7 ± 5.6 |

| Normal | 37.7 ± 10.9 | 35.3 ± 11.6 | 37.2 ± 13.7 | 41.8 ± 20.3 | 36.7 ± 16.2 | |

| Increased | 36.5 ± 21.8 | 35.3 ± 14.6 | 27.4 ± 9.4 | 35.8 ± 12.9 | 34.0 ± 7.4 | |

| Mixed venous blood capacity for transporting CO2 (ml/100 ml per mmHg) | Sham | 0.67 ± 0.12 | 0.59 ± 0.40 | 0.51 ± 0.11 | 0.61 ± 0.21 | 0.61 ± 0.13 |

| Normal | 0.62 ± 0.12 | 0.49 ± 0.12* | 0.55 ± 0.04* | 0.47 ± 0.09* | 0.44 ± 0.09*† | |

| Increased | 0.67 ± 0.24 | 0.38 ± 0.27* | 0.42 ± 0.24* | 0.45 ± 0.19* | 0.48 ± 0.12*† | |

| Mesenteric venous blood capacity for transporting CO2 (ml/100 ml per mmHg) | Sham | 1.14 ± 0.24 | 1.15 ± 0.32 | 1.22 ± 0.29 | 1.37 ± 0.22 | 1.28 ± 0.08 |

| Normal | 1.04 ± 0.22 | 0.99 ± 0.38 | 0.86 ± 0.24† | 0.78 ± 0.33*† | 0.76 ± 0.24*† | |

| Increased | 1.17 ± 0.45 | 0.85 ± 0.29 | 0.66 ± 0.27† | 0.81 ± 0.19† | 0.69 ± 0.18*† | |

* P < 0.05 versus basal. † P < 0.05 versus sham. ‡ P < 0.05 versus normal. Sham, sham group; normal, normal blood flow group; increased, increased blood flow group.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that increased blood flow prevented the development of intramucosal acidosis. However, anion-gap metabolic acidosis was larger in hyperresuscitated animals. These results underscore the different underlying mechanisms of each type of acidosis.

The experimental model of endotoxemia

We used a short-term infusion of endotoxin followed by saline expansion to induce a state of normodynamic shock, with preserved cardiac output and intestinal blood flow [19,20]. A state of normodynamic shock was chosen as a control group to avoid CO2 accumulation caused by macrovascular hypoperfusion. We found that intramucosal acidosis and systemic metabolic acidosis occurred, in spite of stable systemic and gut oxygen transports and consumptions.

The reason for increased intestinal ΔPCO2 in sepsis remains controversial [21]. It might reflect hypoperfusion, but has also been found in normodynamic states [22]. Vallet and colleagues studied endotoxemic dogs with low blood flow, resuscitated with dextran. Gut flow was increased and oxygen transport normalized, but oxygen uptake and mucosal PO2 and pH remained low, results that were ascribed to flow redistribution from mucosal to serosal layers [13]. Conversely, Revelly and colleagues described flow redistribution from serosa to mucosa induced by endotoxin [23]. VanderMeer and colleagues found that intramucosal acidosis developed despite preserved blood flow and tissue PO2 in endotoxemic pigs, attributed to changes in energetic metabolism [24]. Thus, the concept of 'cytopathic hypoxia' was introduced [6].

However, cytopathic hypoxia and increased anaerobic CO2 production might not be the sole explanation for the increase in ΔPCO2. Vallet and colleagues [25] and Dubin and colleagues [26] recently showed that hypoperfusion is a key factor in the development of venous and tissue hypercarbia. In addition, Tugtekin and colleagues showed an association between increased ΔPCO2 and diminished villi microcirculation [7].

This body of information suggests that intramucosal acidosis in sepsis is due mainly to microcirculatory alterations, even though cardiac output and regional flows might remain unchanged. Disturbed energetic metabolism might be present in sepsis, but it does not explain intramucosal acidosis. However, it might be a reasonable explanation for the development of systemic metabolic acidosis in our experiments. Increased anion-gap metabolic acidosis appeared despite preserved oxygen metabolism. As described previously, metabolic acidosis was not explained by elevations of lactate but by increases in unmeasured anions whose source and identification are still unknown [27,28].

Effects of saline solution expansion on intramucosal acidosis

Increased blood flow by volume expansion prevented ΔPCO2 elevation. PCO2 gradients, venoarterial and tissue-arterial PCO2 differences are the result of interactions between CO2 production, blood capacity to transport CO2 and blood flow to tissues. We and others have previously shown that ΔPCO2 fails to reflect tissue hypoxia when blood flow is preserved [25,26,29]. Our results suggest that intramucosal acidosis is related mainly to local hypoperfusion, because the only difference between our groups, in terms of PCO2 difference determinants, was the level of blood flow. We can speculate that volume expansion might improve microcirculation and, subsequently, CO2 clearance. However, intramucosal acidosis might be corrected by the inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and without microcirculatory recruitment [30]. Improvement of cellular metabolism and/or redistribution of blood flow from the mucosa to other layers have been proposed as underlying mechanisms. We cannot exclude the possibility that increases in blood flow might decrease tissue hypoxia and anaerobically generated CO2. Intestinal VO2 increased after elevation of O2 transport in the increased blood flow group, suggesting unmet needs in the normal blood flow group. Flow might have been inadequate in the face of increased metabolic requirements caused by endotoxemia [31].

Despite this apparent dependence on intestinal oxygen supply, CO2 production remained stable. Possible reasons are error propagation in the VO2 and VCO2 calculations, or an increase in VO2 due to non-metabolic processes, such as the production of inflammatory reactants and reactive oxygen species [32].

Other investigators have reported that volume expansion could not correct intramucosal acidosis, in both clinical and experimental settings [11,13,14]. Differences in the level of attained blood flow, timing of expansion or the type of injury might account for these findings opposite to ours.

Potential limitations of our study are related to the errors of saline tonometry, such as inadequate equilibration time, deadspace effect and underestimation of PCO2 by blood gas analyzers [33,34].

Effects of saline solution expansion on metabolic acidosis

Metabolic acidosis was a prominent finding in our study. Expansion with large volumes of saline predictably produced hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis [35]. In addition, metabolic acidosis arose as a result of unmeasured anions. Previous research has shown that during streptococcal infusion in pigs, metabolic acidosis decreased, but did not disappear, when oxygen transport was supported with dextran and red blood cells [36].

The reason for augmented unmeasured anions in the increased blood flow group is unclear. Possible causes are washout of tissue acids by high blood flow, or an impairment of oxygenation caused by tissue edema. Nevertheless, Gow and colleagues have shown that oxygen extraction is already altered in septic animals, so increased diffusion distances would not be relevant [37].

In addition, hyperchloremic acidosis might induce an inflammatory response, cellular dysfunction and apoptosis, and increased mortality in experimental septic shock [38-41]. In this way, a deleterious effect of acidosis on cellular function with the subsequent production of unknown anions might be operative.

Conclusions

Despite preserved blood flow and oxygen transport, intramucosal acidosis developed in endotoxemic sheep. Volume expansion prevented the increase in ΔPCO2, implying that intramucosal acidosis is related mainly to local hypoperfusion. Despite aggressive expansion, anion-gap metabolic acidosis worsened, which suggests an effect on cellular metabolism.

Key messages

• Intramucosal acidosis developed in endotoxemic sheep, despite preserved blood flow and oxygen transport.

• Increased blood flow prevented elevation in ΔPCO2, suggesting that intramucosal acidosis is mainly related to local hypoperfusion. However, anion-gap metabolic acidosis was higher, pointing to a possible effect on cellular mechanism.

Abbreviations

CaO2 = arterial oxygen content; CCO2 = CO2 content; CvmO2 = mesenteric venous oxygen content; CvO2 = mixed venous oxygen content; DO2 = systemic oxygen transport; DO2i = intestinal oxygen transport; ΔPCO2 = intramucosal minus arterial PCO2 gradient; FIO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen; PCO2 = carbon dioxide tension; PO2 = partial pressure of oxygen; Q = cardiac output; Qintestinal = intestinal blood flow; Ra-v = global blood capacity for transporting CO2; VCO2 = systemic CO2 production; VCO2i = intestinal CO2 production; VO2 = systemic oxygen consumption; VO2i = intestinal oxygen consumption.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

AD was responsible for the study concept and design, the analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. GM, MOP, VSKE and HSC performed the acquisition of data and contributed to the draft of the manuscript. BM and GE conducted the blood determinations and contributed to the draft of the manuscript. MB and JPS performed the surgical preparation and contributed to the discussion. EE helped in the draft of the manuscript and made a critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

See related commentary http://ccforum.com/content/9/2/149

Contributor Information

Arnaldo Dubin, Email: arnaldodubin@speedy.com.ar.

Gastón Murias, Email: gmurias@yahoo.com.

Bernardo Maskin, Email: bermask@fibertel.com.ar.

Mario O Pozo, Email: pozomario@hotmail.com.

Juan P Sottile, Email: sottilejajj@hotmail.com.

Marcelo Barán, Email: marcelobaran@sinectis.com.ar.

Vanina S Kanoore Edul, Email: vaninakedul@hotmail.com.

Héctor S Canales, Email: canaleshector@hotmail.com.

Julio C Badie, Email: jcbadie@hotmail.com.

Graciela Etcheverry, Email: gracielaetcheverry@uolsinectis.com.ar.

Elisa Estenssoro, Email: elisaestenssoro@speedy.com.ar.

References

- Natanson C, Hoffman WD, Suffredini AF, Eichacker PQ, Danner RL. Selected treatment strategies for septic shock based on proposed mechanisms of pathogenesis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:771–783. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-9-199405010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker WC, Montgomery ES, Kaplan E, Elwyn DH. Physiologic patterns in surviving and nonsurviving shock patients. Arch Surg. 1973;106:630–636. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1973.01350170004003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittet JF, Pastor CM, Morel DR. Spontaneous high systemic oxygen delivery increases survival rate in awake sheep during sustained endotoxemia. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:496–503. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Hvastad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, Peterson E, Tomlanovich M, for the Early Goal-directed Therapy Collaborative Group Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1368–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin A, Estenssoro E, Murias G, Canales H, Sottile P, Badie J, Barán M, Pálizas F, Laporte M, Rivas Díaz M. Effects of hemorrhage on gastrointestinal oxygenation. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1931–1936. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink M. Mitochondrial dysfunction as mechanism contributing to organ dysfunction in sepsis. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:219–237. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugtekin IF, Radermacher P, Theisen M, Matejovic M, Stehr A, Ploner F, Matura K, Ince C, Georgieff M, Trager K. Increased ileal-mucosal-arterial PCO2 gap is associated with impaired villus microcirculation in endotoxic pigs. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:757–766. doi: 10.1007/s001340100871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer D, Creteur J, Preiser JC, Dubois MC, Vincent JL. Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:98–104. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200109-016OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spronk PE, Ince C, Gardien MJ, Mathura KR, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Zandstra DF. Nitroglicerin in septic shock after intravascular volume resuscitation. Lancet. 2002;360:1395–1396. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spronk PE, Zandstra DF, Ince C. Sepsis is a disease of the microcirculation. Crit Care. 2004;8:462–468. doi: 10.1186/cc2894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest DM, Baigorri F, Chittock DR, Spinelli JJ, Russell JA. Volume expansion using pentastarch does not change gastric-arterial CO2 gradient or gastric intramucosal pH in patients who have sepsis syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2254–2258. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200007000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark P, Mohedin M. The contrasting effects of dopamine and norepinephrine on systemic and splanchnic oxygen utilization in hyperdynamic sepsis. JAMA. 1994;272:1354–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.272.17.1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet B, Lund N, Curtis SE, Kelly D, Cain SM. Gut and muscle tissue PO2 in endotoxemic dogs during shock and resuscitation. J Appl Physiol. 1994;76:793–800. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.76.2.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagoa CE, de Figueiredo LFP, Cruz RJ, Silva E, Rocha e Silva M. Effects of volume resuscitation on splanchnic perfusion in canine model of severe sepsis induced by live Escherichia coli infusion. Crit Care. 2004;8:R221–R228. doi: 10.1186/cc2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DE, Gutierrez G. Tonometry. A review of clinical studies. Crit Care Clin. 1996;12:1007–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(05)70289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AR, Jones LN, Reed JW. Calculation of whole blood CO2 content. J Appl Physiol. 1988;65:473–477. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.65.1.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaliere F, Antonelli M, Arcangeli A, Conti G, Pennisi MA, Proietti R. Effects of acid-base abnormalities on blood capacity of transporting CO2: adverse effect of metabolic acidosis. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:609–615. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1259-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constable PD. Total weak acid concentration and effective dissociation constant of nonvolatile buffers in human plasma. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1364–1371. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.3.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink MP, Heard SO. Laboratory models of sepsis and septic shock. J Surg Res. 1990;49:186–196. doi: 10.1016/0022-4804(90)90260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traber DL, Flynn JT, Herndon DN, Redl H, Schlag G, Traber LD. Comparison of cardiopulmonary responses to single bolus and continuous infusion of endotoxin in an ovine model. Circ Shock. 1989;27:123–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet B. Gut oxygenation in sepsis: still a matter of controversy? Crit Care. 2002;6:282–283. doi: 10.1186/cc1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonsson JB, Engstrom L, Rasmussen I, Wollert S, Haglund UH. Changes in gut intramucosal pH and gut oxygen extraction ratio in a porcine model of peritonitis and hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1872–1881. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199511000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revelly JP, Ayuse T, Brienza N, Fessler HE, Robotham JL. Endotoxic shock alters distribution of blood flow within the intestinal wall. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1345–1351. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199608000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderMeer TJ, Wang H, Fink MP. Endotoxemia causes ileal mucosal acidosis in the absence of mucosal hypoxia in a normodynamic porcine model of septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1217–1226. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199507000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet B, Teboul JL, Cain S, Curtis S. Venoarterial CO2 difference during regional ischemic or hypoxic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:1317–1321. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.4.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubin A, Murias G, Estenssoro E, Canales H, Badie J, Pozo M, Sottile JP, Baran M, Palizas F, Laporte M. Intramucosal-arterial PCO2 gap (ΔPCO2) fails to increase during hypoxic hypoxia. Crit Care. 2002;6:514–520. doi: 10.1186/cc1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecher C, Rackow EC, Astiz ME, Weil MH. Unaccounted for anion in metabolic acidosis during severe sepsis in humans. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:705–711. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199105000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rackow EC, Mecher C, Astiz ME, Goldstein C, McKee D, Weil MH. Unmeasured anion during severe sepsis with metabolic acidosis. Circ Shock. 1990;30:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez G. A mathematical model of tissue-blood carbon dioxide exchange during hypoxia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:525–533. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-702OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittner A, Nalos M, Asfar P, Yang Y, Ince C, Georgieff M, Bruckner UB, Radermacher P, Froba G. Mechanisms of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) inhibition-related improvement of gut mucosal acidosis during hyperdynamic porcine endotoxemia. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:312–316. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1577-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob SM. Splanchnic ischaemia. Crit Care. 2002;6:306–312. doi: 10.1186/cc1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DE, Piantadosi CA. Oxidative metabolism in sepsis and sepsis syndrome. J Crit Care. 1995;10:122–135. doi: 10.1016/0883-9441(95)90003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oud L, Kruse JA. Poor in vivo reproducibility of gastric intramucosal pH determined by saline-filled balloon tonometry. J Crit Care. 1996;11:144–150. doi: 10.1016/S0883-9441(96)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverink PJGM, Kolkman JJ, Groeneveld ABJ, De Vries JW. Catheter deadspace: a source of error during tonometry. Br J Anaesth. 1998;80:337–341. doi: 10.1093/bja/80.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA. Saline-induced hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:259–260. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudinsky BF, Meadow WL. Relationship between oxygen delivery and metabolic acidosis during sepsis in piglets. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:831–839. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow KW, Phang PT, Tebbutt-Speirs SM, English JC, Allard MF, Goddard CM, Walley KR. Effect of crystalloid administration on oxygen extraction in endotoxemic pigs. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1667–1675. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA, Song M, Li J. Lactic and hydrochloric acids induce different patterns of inflammatory response in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;286:R686–R692. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00564.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatte HS, Rhee JH, Zagarins SE, Treanor PR, Birjiniuk V, Crittenden MD, Khuri SF. Acidosis-induced apoptosis in human and porcine heart. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1376–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2003.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor AE, 3rd, Diebel LN, Liberati DM, Dulchavsky SA, Brown WJ, Diglio CA. The synergistic effects of hypoxia/reoxygenation or tissue acidosis and bacteria on intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis. J Trauma. 2003;55:241–247. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000079249.50967.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellum JA. Fluid resuscitation and hyperchloremic acidosis in experimental sepsis: improved short-term survival and acid-base balance with Hextend compared with saline. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:300–305. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200202000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]